Javanese script

Javanese

| |

|---|---|

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 15th–present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Languages | Javanese, Sundanese, Madurese, Sasak, Indonesian, Kawi, Sanskrit |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems | Balinese alphabet Batak alphabet Baybayin scripts Lontara alphabet Makasar Sundanese script Rencong alphabet Rejang alphabet |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Java (361), Javanese |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Javanese |

| U+A980–U+A9DF | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

The Javanese script (natively known as Aksara Jawa, Hanacaraka, Carakan, and Dentawyanjana)[1] is one of Indonesia's traditional scripts developed on the island of Java. The script is primarily used to write the Javanese language, but in the course of its development has also been used to write several other regional languages such as Sundanese, Madurese, and Sasak; the lingua franca of the region, Malay; as well as the historical languages Kawi and Sanskrit. Javanese script was actively used by the Javanese people for writing day-to-day and literary texts from at least the mid-15th century CE until the mid-20th century CE, before its function was gradually supplanted by the Latin alphabet. Today the script is taught in DI Yogyakarta, Central Java, and the East Java Province as part of the local curriculum, but with very limited function in everyday use.[2][3]

The Javanese script is an abugida writing system which consists of 20 to 33 basic letters, depending on the language being written. Like other Brahmic scripts, each letter (called an aksara) represents a syllable with the inherent vowel /a/ or /ɔ/ which can be changed with the placement of diacritics around the letter. Each letter has a conjunct form called pasangan, which nullifies the inherent vowel of the previous letter. Traditionally, the script is written without space between words (scriptio continua) but is interspersed with a group of decorative punctuation.

History

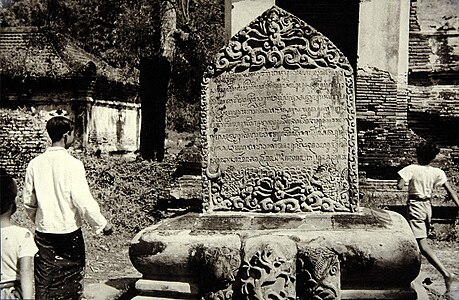

The Javanese script's evolutionary history can be traced fairly well due to the significant amount of inscriptional evidences left behind throughout allowed for epigraphical studies to be carried out. The oldest root of the Javanese script is the Tamil-Brahmi script which evolved into the Pallava script in Southern and Southeast Asia between the 6th and 8th centuries. Pallava script, in turn, evolved into the Kawi script which was actively used throughout Indonesia's Hindu-Buddhist period between the 8th and 15th centuries. In various parts of Indonesia, Kawi script would then evolve into Indonesia's various traditional scripts, one of them being Javanese script.[4] The modern Javanese script seen today evolved from Kawi script between the 14th and 15th centuries, a period in which Java began to receive significant Islamic influence.[5][6][7]

For around 500 years, from the 15th until the mid-20th century, Javanese script was actively used by the Javanese people for writing day-to-day and literary texts with a wide range of themes and content. Javanese script was used throughout the island at a time when there was no easy means of communication between remote areas and no impulse towards standardization. As a result, there is a huge variety in historical and local styles of Javanese writing throughout the ages. The ability of a person to read a bark-paper manuscript from the town of Demak written around 1700 is no guarantee that the same person would also be able to make sense of a palm-leaf manuscript written at the same time only 50 miles away on the slopes of Mount Merapi. The great differences between regional styles almost makes it seem that the "Javanese script" is in fact a family of scripts.[8] Javanese writing traditions were especially cultivated in the Kraton environment in Javanese cultural centers, such as Yogyakarta and Surakarta. However, Javanese texts are known to be made and used by various layers of society with varying usage intensities between regions. In West Java, for example, Javanese script was mainly used by the Sundanese nobility (ménak) due to the political influence of the Mataram kingdom.[9] However, most Sundanese people within the same time period more commonly used the Pegon script which was adapted from the Arabic alphabet.[10] Javanese literature is almost always composed in metrical verses that are designed to be sung, thus Javanese texts are not only judged by their content and language but also by the merit of their melody and rhythm during recitation sessions.[11] Javanese writing tradition also relied on periodic copying due to deterioration of writing materials in the tropical Javanese climate; as a result, many physical manuscripts that are available now are 18th or 19th century copies, though their contents can usually be traced to far older prototypes.[7]

Media

Javanese script has been written with numerous media that have shifted over time. Kawi script, which is ancestral to Javanese script, is often found on stone inscriptions and copper plates. Everyday writing in Kawi was done in palm leaf form locally known as lontar, which are processed leaves of the tal palm (Borassus flabellifer). Each lontar leaf has the shape of a slim rectangle 2.8 to 4 cm in width and varied length between 20 and 80 cm. Each leaf can only accommodate around 4 lines of writing, which are incised in horizontal orientation with a small knife and then blackened with soot to increase readability. This media has a long history of attested use all over South and Southeast Asia.[12]

In the 13th century, paper began to be used in the Malay archipelago. This introduction is related to spread of Islam in the region, due to the Islamic writing tradition that is supported by the use of paper and codex manuscript. As Java began to receive significant Islamic influence in the 15th century, coinciding with the period in which the Kawi script began to transition into the modern Javanese script, paper became widespread in Java while the use of lontar only persisted in a few places.[13] There are two kinds of paper that are commonly used in Javanese manuscript: locally produced paper called daluang, and imported paper. Daluang (also spelled dluwang) is a paper made from the beaten bark of the saéh tree (Broussonetia papyrifera). Visually, daluang can be easily differentiated from regular paper by its distinctive brown tint and fibrous appearance. A well made daluang has a smooth surface and is quite durable against manuscript damage commonly associated with tropical climates, especially insect damage. Meanwhile, a coarse daluang has a bumpy surface and tends to break easily. Daluang is commonly used in manuscripts produced by Javanese Kratons (palaces) and pesantren (Islamic boarding schools) between the 16th to 17th centuries.[14]

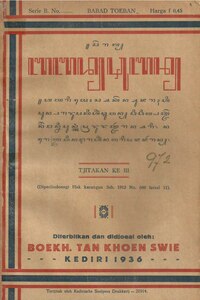

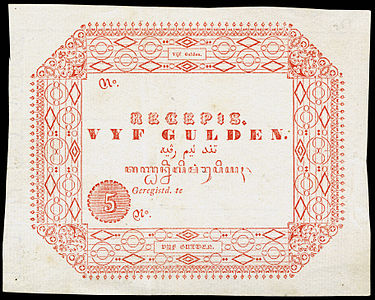

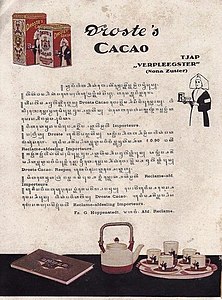

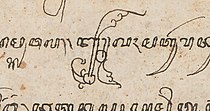

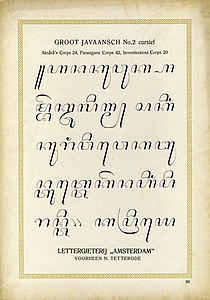

Most imported paper in Indonesian manuscripts came from Europe. In the beginning, only a few scribes were able to use European paper due to its high cost—paper made with using European methods of the time could only be imported in limited number.[a] In colonial administration, the use of European paper had to be supplemented with Javanese daluang and imported Chinese paper until at least the 19th century. As paper supply increased due to growing imports from Europe, scribes in palaces and urban settlements gradually opted to use European paper as the primary media for writing, while daluang paper was increasingly associated with pesantren and rural manuscripts.[13] Alongside the increase of European paper supply, attempts to create Javanese printing type began, spearheaded by several European figures. With the establishment of printing technology in 1825, materials in Javanese script could be mass-produced and became increasingly common in various aspect of pre-independence Javanese life, from letters, books, and newspapers, to magazines, and even advertisements and paper currency.[15]

Usage

| Usage of the Javanese Script | |

|

For at least 500 years, from the 15th century until the mid 20th century, Javanese script was used by all layers of Javanese society for writing day-to-day and literary texts with a wide range of theme and content. Due to the significant influence of oral tradition, reading in pre-independence Javanese society is usually a performance; Javanese literature texts are almost always composed in metrical verses that are designed to be recited, thus Javanese texts are not only judged by their content and language, but also by the merit of their melody and rhythm during recitation sessions.[11] Javanese poets are not expected to create new stories and characters; instead the role of the poet is to rewrite and recompose existing stories into forms that are suitable to local taste and prevailing trends. As a result, Javanese literary works such as the Cerita Panji do not have a single authoritative version referenced by all others, instead, the Cerita Panji is a loose collection of numerous tales with various versions bound together by the common thread of the Panji character.[16] Literature genres with the longest attested history are Sanskrit epics such as the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which have been recomposed since the Kawi period and which introduced hundreds of characters familiar in Javanese wayang stories today, including Arjuna, Srikandi, Ghatotkacha and many others. Since the introduction of Islam, characters of Middle-Eastern provenance such as Amir Hamzah and the Prophet Joseph have also been frequent subjects of writing. There are also local characters, usually set in Java's semi-legendary past, such as Prince Panji, Damar Wulan, and Calon Arang.[17]

When studies of Javanese language and literature began to attract European attention in the 19th century, an initiative to create a Javanese movable type began to take place in order to mass-produce and quickly disseminate Javanese literary materials. One of the earliest attempts to create a movable Javanese type was by Paul van Vlissingen. His typeface was first put in use in the Bataviasche Courant newspaper's October 1825 issue.[18] While lauded as a considerable technical achievement, many at the time felt that Vlissingen's design was a coarse copy of the fine Javanese hand used in literary texts, and so this early attempt was further developed by numerous other people to varying degrees of success as the study of Javanese developed over the years.[19] In 1838, Taco Roorda completed his typeface, known as Tuladha Jejeg, that was based on the hand of Surakartan scribes[b] with some European typographical elements mixed in. Roorda's font garnered positive feedback and soon became the main choice to print any Javanese text. From then, reading materials in printed Javanese using Roorda's typeface became widespread among the Javanese populace and were widely used in materials other than literature. The establishment of print technology enabled a printing industry which, for the next century, produced various materials in printed Javanese, from administrative papers and school books, to mass media such as the Kajawèn magazine which was entirely printed in Javanese in all of its article and columns.[15][21] In the governmental context, one application of the Javanese script was the multilingual legal text on the Netherlands Indies gulden banknotes circulated by the Bank of Java.[22]

Decline

As literacy and demand for reading materials increased in the beginning of the 20th century, Javanese publishers paradoxically began to decrease the amount of Javanese script publication due to a practical and economic consideration: printing any text in Javanese script at the time required twice the amount of paper compared to the same text rendered in the Latin alphabet, so that Javanese texts were more expensive and time-consuming to produce. In order to lower production costs and keep book prices affordable to the general populace, many publishers (such as the government-owned Balai Pustaka) gradually prioritized publication in the Latin alphabet.[23][c] However, the Javanese population at the beginning of the 20th century maintained the use of Javanese script in various aspects of everyday life. It was, for example, considered more polite to write a letter using Javanese script, especially one addressed toward an elder or superior. Many publishers, including Balai Pustaka, continued to print books, newspapers, and magazines in Javanese script due to sufficient, albeit declining, demand. The use of Javanese script only started to drop significantly during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies beginning in 1942.[25] Some writers attribute this sudden decline to prohibitions issued by the Japanese government banning the use of native script in the public sphere, though no documentary evidence of such a ban has yet been found.[d] Nevertheless, the use of Javanese script did decline significantly during the Japanese occupation and it never recovered its previous widespread use in post-independence Indonesia.

Contemporary use

In contemporary usage, Javanese script is still taught as part of the local curriculum in Yogyakarta, Central Java, and the East Java Province. Several local newspapers and magazines have columns written in Javanese script, and the script can frequently be seen on public signage. However, many contemporary attempts to revive Javanese script are symbolic rather than functional; there are no longer, for example, periodicals like Kajawèn magazine that publish significant content in Javanese script. Most Javanese people today know the existence of the script and recognize a few letters, but it is rare to find someone who can read and write it meaningfully.[27][28] Therefore, as recently as 2019, it is not uncommon to see Javanese script signage in public places with numerous misspellings and basic mistakes.[29][30] Several hurdles in revitalizing the use of Javanese script includes information technology equipment that does not support correct rendering of the Javanese script, lack of governing bodies with sufficient competence to consult on its usage, and lack of typographical explorations that may intrigue contemporary viewers. Nevertheless, attempts to revive the script are still being conducted by several communities and public figures who encouraged the use of Javanese script in the public sphere, especially with digital devices.[31]

Letters

Javanese script contains around 45 letters, but not all of them are used equally. Over the course of its development, some letters became obsolete and some are only used in certain contexts. As such, it is common to divide the letters in several groups based on their function.

Consonants and basic syllables

A basic letter in the Javanese script is called an aksara which represents a syllable. The aksara wyanjana (ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦮꦾꦚ꧀ꦗꦤ) are consonant letters with an inherent vowel, either /a/ or /ɔ/. As a Brahmi derived script, the Javanese script originally had 33 wyanjana letters to write the 33 consonants that are used in Sanskrit and Kawi.[32][33]

| Unvoiced | Voiced | Semivowel | Sibilant | Fricative | Nasal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Unaspirated | Aspirated | |||||

| Velar | ꦏ ka

|

ꦑ kha

|

ꦒ ga

|

ꦓ gha

|

ꦔ ṅa

|

ꦲ ha/a

| ||

| Palatal | ꦕ ca

|

ꦖ cha

|

ꦗ ja

|

ꦙ jha

|

ꦚ ña

|

ꦪ ya

|

ꦯ śa

|

|

| Retroflex | ꦛ ṭa

|

ꦜ ṭha

|

ꦝ ḍa

|

ꦞ ḍha

|

ꦟ ṇa

|

ꦫ ra

|

ꦰ ṣa

|

|

| Dental | ꦠ ta

|

ꦡ tha

|

ꦢ da

|

ꦣ dha

|

ꦤ na

|

ꦭ la

|

ꦱ sa

|

|

| Labial | ꦥ pa

|

ꦦ pha

|

ꦧ ba

|

ꦨ bha

|

ꦩ ma

|

ꦮ wa

|

||

- ^ may represent /ha/ or /a/ in the Kawi language

The modern Javanese script only uses 20 consonants and 20 basic letters known as aksara nglegéna (ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦔ꧀ꦭꦼꦒꦺꦤ). Modern Javanese script is commonly arranged in the hanacaraka sequence, a pangram whose name is derived from its first five letters, similar to the word "alphabet" which comes from the first two letters of the Greek alphabet, alpha, beta.[34] This sequence has been used at least the 15th century, when the island of Java started to receive significant Islamic influence.[35] There are numerous interpretations on the supposed philosophical and esoteric qualities of the hanacaraka sequence, [36] and it is often linked to the myth of Aji Saka.[37][38]

ꦲ ha

|

ꦤ na

|

ꦕ ca

|

ꦫ ra

|

ꦏ ka

|

Javanese: ꦲꦤꦕꦫꦏ, romanized: hana caraka, lit. 'There were (two) emissaries.' |

ꦢ da

|

ꦠ ta

|

ꦱ sa

|

ꦮ wa

|

ꦭ la

|

Javanese: ꦢꦠꦱꦮꦭ, romanized: data sawala, lit. 'They began to fight.' |

ꦥ pa

|

ꦣ dha

|

ꦗ ja

|

ꦪ ya

|

ꦚ ña

|

Javanese: ꦥꦝꦗꦪꦚ, romanized: padha jayanya, lit. 'Their valor was equal' |

ꦩ ma

|

ꦒ ga

|

ꦧ ba

|

ꦡ tha

|

ꦔ ṅa

|

Javanese: ꦩꦒꦧꦛꦔ, romanized: maga bathanga, lit. 'They both fell dead.' |

Vowels and vowel diacritics

Javanese script has 14 vowel letters (Javanese: ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦱ꧀ꦮꦫ, romanized: aksara swara) inherited from Sanskrit.[33]

| Velar | Palatal | Labial | Retroflex | Dental | Velar-palatal | Velar-labial | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short | ꦄ a

|

ꦆ i

|

ꦈ u

|

ꦉ ṛ IPA: /rə/

|

ꦊ ḷ IPA: /lə/

|

ꦌ é IPA: /e/

|

ꦎ o

|

| Long | ꦄꦴ ā

|

ꦇ ī

|

ꦈꦴ ū

|

ꦉꦴ ṝ

|

ꦋ ḹ

|

ꦍ ai IPA: /aj/

|

ꦎꦴ au IPA: /au/

|

Diacritics (sandhangan ꦱꦤ꧀ꦝꦔꦤ꧀) are dependent signs that are used to modify the inherent vowel of a letter. Similar to Javanese letters, Javanese diacritics may be divided into several groups based on their function.

Swara

Sandhangan swara (ꦱꦤ꧀ꦝꦁꦔꦤ꧀ꦱ꧀ꦮꦫ) are diacritics that are used to change the inherent /a/ into different vowels. Their forms are as follows:[40]

| Short | Long | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -a | -i | -u | -é[1] | -o | -e[2] | -ā | -ī | -ū | -ai[3] | -au[4] | -eu[5][6] |

| - | ꦶ |

ꦸ |

ꦺ |

ꦺꦴ |

ꦼ |

ꦴ |

ꦷ |

ꦹ |

ꦻ |

ꦻꦴ |

ꦼꦴ |

| - | wulu | suku | taling | taling-tarung | pepet | tarung | wulu melik | suku mendut | dirga muré | dirga muré-tarung | pepet-tarung |

| ka | ki | ku | ké | ko | ke | kā | kī | kū | kai | kau | keu |

| ꦏ | ꦏꦶ | ꦏꦸ | ꦏꦺ | ꦏꦺꦴ | ꦏꦼ | ꦏꦴ | ꦏꦷ | ꦏꦹ | ꦏꦻ | ꦭꦻꦴ | ꦏꦼꦴ |

| Notes

The following pronunciations are not used in modern Javanese:

| |||||||||||

Similar to swara letters, only short vowel diacritics are taught and used in contemporary Javanese, while long vowel diacritics are only used in Sanskrit and Kawi writing.

As with the wyanjana letters, the modern Javanese language does not use the whole inventory of vowels. Only short vowel letters are now commonly used and taught. In modern spelling, swara letters may be used to replace ⟨ꦲ⟩, which can be read as either /ha/ or /a/, and to disambiguate the pronunciation of unfamiliar terms and names.[41]

Syllabic consonants

Pa cerek ⟨ꦉ⟩, pa cerek dirgha ⟨ꦉꦴ⟩, nga lelet ⟨ꦊ⟩, and nga lelet raswadi ⟨ꦋ⟩ are syllabic consonants that are primarily used in Sanskrit.[39] When adapted to other languages, the function and pronunciation of these letters tend to vary. In modern Javanese language, pa cerek and nga lelet are mandatory shorthand for combination of ra + é ⟨ꦫ + ◌ ꦼ → ꦉ⟩ and la + é ⟨ꦭ + ◌ ꦼ → ꦊ⟩. Both letters are usually re-categorized into their own class called aksara gantèn in modern tables. [42]

Murda and mahaprana

Some of the original letters that originally represented sounds not present in modern Javanese have been repurposed as honorific letters (Javanese: ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦩꦸꦂꦢ, romanized: aksara murda) which are used for in writing the respected personal names of respected figures, be they legendary, such as ꦨꦶꦩ, Bima or real such as Javanese: ꦦꦑꦸꦨꦸꦮꦟ, romanized: Pakubuwana.[43] Of the 20 basic letters, only nine have corresponding murda forms. Because of this, the use of murda is not identical to the capitalization of proper names.[43] If the first syllable of a name does not have a murda form, the next syllable that does can be written as a murda. Highly respected names may be written completely in murda, or with as many murda as possible, but in essence, the use of murda is optional and may be inconsistent in traditional texts. For example, the name Gani can be spelled as ꦒꦤꦶ (without murda), ꦓꦤꦶ (with a murda on the first syllable), or ꦓꦟꦶ with every syllable as a murda.

ꦟ na

|

ꦖ ch

|

ꦬ ra

|

ꦑ ka

|

ꦡ ta

|

ꦯ sa

|

ꦦ pa

|

ꦘ nya

|

ꦓ gya

|

ꦨ ba

|

The remaining letters that are not classified as nglegéna or repurposed as murda are aksara mahaprana, letters that are used in Sanskrit and Kawi texts but obsolete in modern Javanese.[32][44][45]

ꦣ da

|

ꦰ sa

|

ꦞ dha

|

ꦙ ja

|

ꦜ tha

|

Rékan

The Javanese script includes a number of letters additional letters used to write sounds found in words found in words borrowed from foreign languages (Javanese: ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫ ꦫꦺꦏꦤ꧀, romanized: aksara rékan.[46] This type of letters were initially developed to write Arabic loanwords, later adapted to write Dutch loanwords, and in contemporary usage are also used to write Indonesian and English loanwords. Most rékan letters are formed by adding the cecak telu diacritic to the letters that are considered closest-sounding to the foreign sound in question. For example, ⟨ꦥ꦳⟩ (fa) is formed by adding a cecak telu diacritic ⟨◌꦳⟩ to ⟨ꦥ⟩ (pa). The combination of wyanjana letter and corresponding foreign sounds for each rékan may be different between sources.[47]

| Javanese | ḥa ꦲ꦳

|

kha ꦏ꦳

|

qa ꦐ

|

dza ꦢ꦳

|

sya ꦱ꦳

|

fa/va ꦥ꦳

|

za ꦗ꦳

|

gha ꦒ꦳

|

ʾa ꦔ꦳

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | ح

|

خ

|

ق

|

ذ

|

ش

|

ف

|

ز

|

غ

|

ع

|

- ^ only used in the Sasak language

Closed syllables

Closed syllables are written by adding diacritics (Javanese: ꦱꦤ꧀ꦝꦁꦔꦤ꧀ꦥꦚꦶꦒꦼꦒꦶꦁ ꦮꦤ꧀ꦢ, romanized: sandhangan panyigeging wanda).[48]

panyangga ꦀ

|

cecek ꦁ -ng

|

layar ꦂ -r

|

wignyan ꦃ -h

|

pangkon ꧀

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

ꦏꦀ kam

|

ꦏꦁ kang

|

ꦏꦂa kar

|

ꦏꦃ kah

|

ꦏ꧀ k

|

Semivowels and their diacritics

Consonant clusters containing a semivowel are written by adding a diacritic (Javanese: ꦱꦤ꧀ꦝꦁꦔꦤ꧀ꦮꦾꦚ꧀ꦗꦤ, romanized: sandhangan wyanjana) to the base syllable.

keret ꦽ -re-

|

pèngkal ꦾ -y-

|

cakra ꦿ -r-

|

panjingan la ꧀ꦭ -l-

|

gembung ꧀ꦮ -w-

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

ꦏꦽ kre

|

ꦏꦾ kya

|

ꦏꦿ kra

|

ꦏ꧀ꦭ kla

|

ꦏ꧀ꦮ kwa

|

Conjunct

The inherent vowel of each basic letter can be suppressed with the use of the virama, natively known as pangkon. However, the pangkon is not normally used in the middle of a word or sentence. For closed syllables in such positions, a conjunct form called pasangan (ꦥꦱꦔꦤ꧀) is used instead. Every basic letter has a pasangan counterpart, and if a pasangan is attached to a basic letter, the inherent vowel of the attached letter is nullified. Their forms are as follows:[50]

| ha/a | na | ca | ra | ka | da | ta | sa | wa | la | pa | dha | ja | ya | nya | ma | ga | ba | tha | nga | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nglegena | Aksara | ꦲ |

ꦤ |

ꦕ |

ꦫ |

ꦏ |

ꦢ |

ꦠ |

ꦱ |

ꦮ |

ꦭ |

ꦥ |

ꦝ |

ꦗ |

ꦪ |

ꦚ |

ꦩ |

ꦒ |

ꦧ |

ꦛ |

ꦔ | |

| Pasangan | ꧀ꦲ |

꧀ꦤ |

꧀ꦕ |

꧀ꦫ |

꧀ꦏ |

꧀ꦢ |

꧀ꦠ |

꧀ꦱ |

꧀ꦮ |

꧀ꦭ |

꧀ꦥ |

꧀ꦝ |

꧀ꦗ |

꧀ꦪ |

꧀ꦚ |

꧀ꦩ |

꧀ꦒ |

꧀ꦧ |

꧀ꦛ |

꧀ꦔ | ||

| Murda | Aksara | ꦟ |

ꦖ |

ꦬ |

ꦑ |

ꦡ |

ꦯ |

ꦦ |

ꦘ |

ꦓ |

ꦨ |

|||||||||||

| Pasangan | ꧀ꦟ |

꧀ꦖ1 |

꧀ꦬ |

꧀ꦑ |

꧀ꦡ |

꧀ꦯ |

꧀ꦦ |

꧀ꦘ |

꧀ꦓ |

꧀ꦨ |

||||||||||||

| Mahaprana | Aksara | ꦣ |

ꦰ |

ꦞ |

ꦙ |

ꦜ |

||||||||||||||||

| Pasangan | ꧀ꦣ |

꧀ꦰ |

꧀ꦞ |

꧀ꦙ |

꧀ꦜ |

|||||||||||||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Examples of pasangan use, using characters from the Unicode Standard for Javanese script (which is used in this article), are as follows:

| component | result | remark | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a + (ka + (pangkon + sa)) + ra → a + (ka + (pasangan sa)) + ra = a(ksa)ra | |||||||||||

| ka + (na + (pangkon + tha) + -i) → ka + (na + (pasangan tha) + -i) = ka(nthi) | |||||||||||

Note that the pasangan of a letter can be produced by typing the pangkon followed by the letter in its aksara/basic form. This appeals to the idea that a pangkon mutes the vowel of previous letter, and that adding a pasangan is phonetically equivalent to first muting the vowel of the previous letter and then adding a new letter.

Numerals

The Javanese script has its own numerals (angka ꦲꦁꦏ) that behave similarly to Arabic numerals. However, most Javanese numerals has the exact same glyph as several basic letters, for example the numeral 1 ꧑ and wyanjana letter ga ꦒ, or the numeral 8 ꧘ and murda letter pa ꦦ. To avoid confusion, numerals that are used in the middle of sentences must be enclosed within pada pangkat or pada lingsa punctuations. For example, tanggal 17 Juni (the date 17 June) is written ꦠꦁꦒꦭ꧀꧇꧑꧗꧇ꦗꦸꦤꦶ or ꦠꦁꦒꦭ꧀꧈꧑꧗꧈ꦗꦸꦤꦶ. Enclosing punctuation may be ignored if their use as numerals is understood by context, for example as page numbers in the corner of pages. Their forms are as follows:[51][52]

0 ꧐

|

1 ꧑

|

2 ꧒

|

3 ꧓

|

4 ꧔

|

5 ꧕

|

6 ꧖

|

7 ꧗

|

8 ꧘

|

9 ꧙

|

Punctuation

Traditional Javanese texts are written with no spaces between words (scriptio continua) with several punctuation marks called pada (ꦥꦢ). Their form are as follows:

| common punctuation | epistolary | correction | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

꧈ lingsa

|

꧉ lungsi

|

꧊ adeg

|

꧋ adeg-adeg

|

꧌...꧍ pisélèh

|

꧁...꧂ rerenggan

|

꧇ pangkat

|

ꧏ rangkap

|

꧃ andhap

|

꧄ madya

|

꧅ luhur

|

꧋꧆꧋ guru

|

꧉꧆꧉ pancak

|

꧞꧞꧞ tirta tumétès

|

꧟꧟꧟ isèn-isèn

|

In contemporary teaching, the most frequently used punctuations are pada adeg-adeg, pada lingsa, and pada lungsi, which are used to open paragraphs (similar to pillcrow), separating sentences (similar to comma), and ending sentences (similar to full stop). Pada adeg and pada pisélèh may be used to indicate insertion in the middle of sentences similar to parenthesis or quotation marks, while pada pangkat has a similar function to the colon. Pada rangkap is sometimes used as an iteration mark for reduplicated words (for example kata-kata ꦏꦠꦏꦠ → kata2 ꦏꦠꧏ).[53]

Several punctuation marks do not have Latin equivalents and are often decorative in nature with numerous variant shapes, for example the rerenggan which is sometimes used to enclose titles. In epistolary usage, several punctuations are used in the beginning of letters and may also be used to indicate the social status of the letter writer; from the lowest pada andhap, to middle pada madya, and the highest pada luhur. Pada guru is sometimes used as a neutral option without social connotation, while pada pancak is used to end a letter. However this is a generalized function. In practice, similar to rerenggan these epistolary punctuation marks are often decorative and optional with various shape used in different regions and by different scribes.[53]

When errors occurred during manuscript copying, several Kraton scribes used special correction marks instead of crossing out the erroneous parts: tirta tumétès normally found in Yogyakarta manuscripts, and isèn-isèn found in Surakarta manuscripts. These correction marks are directly applied following the erroneous part before the scribe continued writing. For example, if a scribe wanted to write pada luhur ꦥꦢꦭꦸꦲꦸꦂ but accidentally wrote pada hu ꦥꦢꦲꦸ before realizing the mistake, this word may be corrected into pada hu···luhur ꦥꦢꦲꦸ꧞꧞꧞ꦭꦸꦲꦸꦂ or ꦥꦢꦲꦸ꧟꧟꧟ꦭꦸꦲꦸꦂ.[54]

Pepadan

Other than the regular punctuation, one of Javanese texts' distinctive characteristics is pepadan (ꦥꦼꦥꦢꦤ꧀), a series of highly ornate verse marks. Several of their form are as follows:

| minor pada | major pada | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

꧅ |

꧅ ꦧ꧀ꦖ ꧅ | |||

The series of punctuation marks that forms pepadan have numerous names in traditional texts. Behrend (1996) divides pepadan into two general groups: the minor pada which consist of a single mark, and the major pada which are composed of several marks. Minor pada are used to indicate divisions of poetic stanzas, which usually came up every 32 or 48 syllables depending on the poetic metre. Major pada are used to demarcate a change of canto (which includes a change of the metre, rhythm, and mood of the recitation) occurring every 5 to 10 pages, though this may vary considerably depending on the structure of the text.[55] Javanese guides often list three kinds of major pada: purwa pada ꧅ ꦧ꧀ꦖ ꧅ which is used in the beginning of the first canto, madya pada ꧅ ꦟ꧀ꦢꦿ ꧅ which is used in between different cantos, and wasana pada ꧅ ꦆ ꧅ which is used in the end of the final canto.[53] But due to the large variety of shapes between manuscripts, these three punctuations are essentially treated as a single punctuation in most Javanese manuscripts.[56]

Pepadan is one of the most prominent elements in a typical Javanese manuscript and are almost always written with high artistic skills, including calligraphy, coloring, and even gilding.[57] In luxurious royal manuscripts, the shape of the pepadan may even contain visual puns that gave clues to the readers regarding the canto of the text; a pepadan with wings or bird figure resembling a crow (called dhandhang in Javanese) indicates the dhandhanggula metre, while pepadan with elements of a goldfish indicates the maskumambang metre (literally "gold floating on water"). One of the scribal centers with the most elaborate and ornate pepadan is the scriptorium of Pakualaman in Yogyakarta.[56][58]

Sample texts

Below is an excerpt of Serat Katuranggan Kucing printed in 1871 with modern Javanese language and spelling.[59]

| Pada | Javanese | English | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese script | Latin | ||

| 7 | ꧅ꦭꦩꦸꦤ꧀ꦱꦶꦫꦔꦶꦔꦸꦏꦸꦕꦶꦁ꧈ ꦲꦮꦏ꧀ꦏꦺꦲꦶꦉꦁꦱꦢꦪ꧈ ꦭꦩ꧀ꦧꦸꦁꦏꦶꦮꦠꦺꦩ꧀ꦧꦺꦴꦁꦥꦸꦠꦶꦃ꧈ ꦊꦏ꧀ꦱꦤꦤ꧀ꦤꦶꦫꦥꦿꦪꦺꦴꦒ꧈ ꦲꦫꦤ꧀ꦮꦸꦭꦤ꧀ꦏꦿꦲꦶꦤꦤ꧀꧈ ꦠꦶꦤꦼꦏꦤꦤ꧀ꦱꦱꦼꦢꦾꦤ꧀ꦤꦶꦥꦸꦤ꧀꧈ ꦪꦺꦤ꧀ꦧꦸꦟ꧀ꦝꦼꦭ꧀ꦭꦁꦏꦸꦁꦲꦸꦠꦩ꧈ | Lamun sira ngingu kucing, awaké ireng sadaya, lambung kiwa tèmbong putih, leksan nira prayoga, aran wulan krahinan, tinekanan sasedyan nira ipun, yèn buṇḍel langkung utama | A completely black cat with white tèmbong (spots) on its left belly is called wulan krahinan. It is a cat that would bring good fortune and accomplishment to all wishes. It is better if its tail is bundhel (short, rounded). |

| 8 | ꧅ꦲꦗꦱꦶꦫꦔꦶꦔꦸꦏꦸꦕꦶꦁ꧈ ꦭꦸꦫꦶꦏ꧀ꦲꦶꦉꦁꦧꦸꦤ꧀ꦠꦸꦠ꧀ꦥꦚ꧀ꦗꦁ꧈ ꦥꦸꦤꦶꦏꦲꦮꦺꦴꦤ꧀ꦭꦩꦠ꧀ꦠꦺ꧈ ꦱꦼꦏꦼꦭꦤ꧀ꦱꦿꦶꦁꦠꦸꦏꦂꦫꦤ꧀꧈ ꦲꦫꦤ꧀ꦝꦣꦁꦱꦸꦁꦏꦮ꧈ ꦥꦤ꧀ꦲꦢꦺꦴꦃꦫꦶꦗꦼꦏꦶꦤꦶꦥꦸꦤ꧀꧈ ꦪꦺꦤ꧀ꦧꦸꦟ꧀ꦝꦼꦭ꧀ꦤꦺꦴꦫꦔꦥꦲ꧈ | Aja sira ngingu kucing, lurik ireng buntut panjang, punika awon lamaté, sekelan sring tukaran, aran ḍaḍang sungkawa, pan adoh rijeki nipun, yèn buṇḍel nora ngapa | A striped black cat with long tail should not be kept as pets. This cat is called dhadhang sungkawa. Your life would encounter frequent arguments and limited wealth. But if its tail is bundhel, then there is no problem. |

Below is an excerpt of Kakawin Rāmāyaṇa printed in 1900 using Kawi language and spelling.[60]

| Pada | Javanese | English | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese script | Latin | ||

| XVI 31 |

꧅ꦗꦲ꧀ꦤꦷꦪꦴꦲ꧀ꦤꦶꦁꦠꦭꦒꦏꦢꦶꦭꦔꦶꦠ꧀꧈ ꦩꦩ꧀ꦧꦁꦠꦁꦥꦴꦱ꧀ꦮꦸꦭꦤꦸꦥꦩꦤꦶꦏꦴ꧈ ꦮꦶꦤ꧀ꦠꦁꦠꦸꦭꦾꦁꦏꦸꦱꦸꦩꦪꦱꦸꦩꦮꦸꦫ꧀꧈ ꦭꦸꦩꦿꦴꦥ꧀ꦮꦺꦏꦁꦱꦫꦶꦏꦢꦶꦗꦭꦢ꧉ | Jahnī yāhning talaga kadi langit, mambang tang pās wulan upamanikā, wintang tulya ng kusuma ya sumawur, lumrā pwekang sari kadi jalada. | The clear water of the lake reflects the sky, a turtle floats therein as if the moon, the stars are scattered blossoms, spreading their scents as if the clouds. |

Comparison with Balinese

The closest relative to the Javanese script is the Balinese script. As direct descendants of the Kawi script, Javanese and Balinese still retain many similarities in terms of basic glyph shape for each letter. One noticeable difference between both scripts is in their orthography; Modern Balinese orthography is more conservative in nature than Modern Javanese counterpart.[61][62][63]

- Modern Balinese orthography retains Sanskrit and Kawi conventions that are no longer used in modern Javanese. For example, the word désa (village) is written in Modern Javanese orthography as ꦢꦺꦱ. According to Balinese orthography, this may be deemed as coarse or incorrect because désa is a Sanskrit loanword (देश, deśa) that should have been spelled according to its original spelling: déśa ꦢꦺꦯ (Balinese: ᬤᬾᬰ), using sa murda instead of sa nglegéna. The Balinese language does not differentiate between the pronunciation of sa nglegéna and sa murda, but the original Sanskrit or Kawi spelling is retained whenever possible. One of the reason for this spelling practice is to differentiate homophones in writing, such as between the word pada (ꦥꦢ / ᬧᬤ, earth/ground), pāda (ꦥꦴꦢ / ᬧᬵᬤ, foot), and padha (ꦥꦣ / ᬧᬥ, same), as well as asta (ꦲꦱ꧀ꦠ / ᬳᬲ᭄ᬢ, is), astha (ꦲꦱ꧀ꦡ / ᬳᬲ᭄ᬣ, bone), and aṣṭa (ꦄꦰ꧀ꦛ / ᬅᬱ᭄ᬝ, eight).

- Modern Javanese orthography use aksara murda (ꦲꦏ꧀ꦱꦫꦩꦸꦂꦢ) which are used for honorific purposes in writing respected names, while Modern Balinese orthography does not have a such rule.

Glyph comparison between the two scripts can be seen below:

| ka | kha | ga | gha | nga | ca | cha | ja | jha | nya | ṭa | ṭha | ḍa | ḍha | ṇa | ta | tha | da | dha | na | pa | pha | ba | bha | ma | ya | ra | la | wa | śa | ṣa | sa | ha/a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese | ꦏ | ꦑ | ꦒ | ꦓ | ꦔ | ꦕ | ꦖ | ꦗ | ꦙ | ꦚ | ꦛ | ꦜ | ꦝ | ꦞ | ꦟ | ꦠ | ꦡ | ꦢ | ꦣ | ꦤ | ꦥ | ꦦ | ꦧ | ꦨ | ꦩ | ꦪ | ꦫ | ꦭ | ꦮ | ꦯ | ꦰ | ꦱ | ꦲ |

| Balinese | ᬓ | ᬔ | ᬕ | ᬖ | ᬗ | ᬘ | ᬙ | ᬚ | ᬛ | ᬜ | ᬝ | ᬞ | ᬟ | ᬠ | ᬡ | ᬢ | ᬣ | ᬤ | ᬥ | ᬦ | ᬧ | ᬨ | ᬩ | ᬪ | ᬫ | ᬬ | ᬭ | ᬮ | ᬯ | ᬰ | ᬱ | ᬲ | ᬳ |

| a | ā | i | ī | u | ū | ṛ | ṝ | ḷ | ḹ | é | ai | o | au | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese | ꦄ | ꦄꦴ | ꦆ | ꦇ | ꦈ | ꦈꦴ | ꦉ | ꦉꦴ | ꦊ | ꦋ | ꦌ | ꦍ | ꦎ | ꦎꦴ |

| Balinese | ᬅ | ᬆ | ᬇ | ᬈ | ᬉ | ᬊ | ᬋ | ᬌ | ᬍ | ᬎ | ᬏ | ᬐ | ᬑ | ᬒ |

| -a | -ā | -i | -ī | -u | -ū | -ṛ | -ṝ | -é | -ai | -o | -au | -e | -eu | -m | -ng | -r | -h | pemati | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese | - | ꦴ | ꦶ | ꦷ | ꦸ | ꦹ | ꦽ | ꦽꦴ | ꦺ | ꦻ | ꦺꦴ | ꦻꦴ | ꦼ | ꦼꦴ | ꦀ | ꦁ | ꦂ | ꦃ | ꧀ |

| Balinese | - | ᬵ | ᬶ | ᬷ | ᬸ | ᬹ | ᬺ | ᬻ | ᬾ | ᬿ | ᭀ | ᭁ | ᭂ | ᭃ | ᬁ | ᬂ | ᬃ | ᬄ | ᭄ |

| ka | kā | ki | kī | ku | kū | kṛ | kṝ | ké | kai | ko | kau | ke | keu | kam | kang | kar | kah | k | |

| Javanese | ꦏ | ꦏꦴ | ꦏꦶ | ꦏꦷ | ꦏꦸ | ꦏꦹ | ꦏꦽ | ꦏꦽꦴ | ꦏꦺ | ꦏꦻ | ꦏꦺꦴ | ꦭꦻꦴ | ꦏꦼ | ꦏꦼꦴ | ꦏꦀ | ꦏꦁ | ꦏꦂ | ꦏꦃ | ꦏ꧀ |

| Balinese | ᬓ | ᬓᬵ | ᬓᬶ | ᬓᬷ | ᬓᬸ | ᬓᬹ | ᬓᬺ | ᬓᬻ | ᬓᬾ | ᬓᬿ | ᬓᭀ | ᬓᭁ | ᬓᭂ | ᬓᭃ | ᬓᬁ | ᬓᬂ | ᬓᬃ | ᬓᬄ | ᬓ᭄ |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese | ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ |

| Balinese | ᭐ | ᭑ | ᭒ | ᭓ | ᭔ | ᭕ | ᭖ | ᭗ | ᭘ | ᭙ |

| Javanese | pada lingsa | pada lungsi | pada pangkat | pada adeg-adeg | pada luhur |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ꧈ | ꧉ | ꧇ | ꧋ | ꧅ | |

| Balinese | carik siki | carik parérèn | carik pamungkah | panti | pamada |

| ᭞ | ᭟ | ᭝ | ᭚ | ᭛ |

| Javanese | ꧅ꦗꦲ꧀ꦤꦷꦪꦴꦲ꧀ꦤꦶꦁꦠꦭꦒꦏꦢꦶꦭꦔꦶꦠ꧀꧈ | ꦩꦩ꧀ꦧꦁꦠꦁꦥꦴꦱ꧀ꦮꦸꦭꦤꦸꦥꦩꦤꦶꦏꦴ꧈ | ꦮꦶꦤ꧀ꦠꦁꦠꦸꦭꦾꦁꦏꦸꦱꦸꦩꦪꦱꦸꦩꦮꦸꦫ꧀꧈ | ꦭꦸꦩꦿꦴꦥ꧀ꦮꦺꦏꦁꦱꦫꦶꦏꦢꦶꦗꦭꦢ꧉ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balinese | ᭛ᬚᬳ᭄ᬦᬷᬬᬵᬳ᭄ᬦᬶᬂᬢᬮᬕᬓᬤᬶᬮᬗᬶᬢ᭄᭞ | ᬫᬫ᭄ᬩᬂᬢᬂᬧᬵᬲ᭄ᬯᬸᬮᬦᬸᬧᬫᬦᬶᬓᬵ᭞ | ᬯᬶᬦ᭄ᬢᬂᬢᬸᬮ᭄ᬬᬂᬓᬸᬲᬸᬫᬬᬲᬸᬫᬯᬳᬸᬭ᭄᭞ | ᬮᬸᬫ᭄ᬭᬧ᭄ᬯᬾᬓᬂᬲᬭᬶᬓᬤᬶᬚᬮᬤ᭟ |

| Jahnī yāhning talaga kadi langit, | mambang tang pās wulan upamanikā, | wintang tulya ng kusuma ya sumawur, | lumrā pwékang sari kadi jalada. | |

| (Kakawin Rāmāyaṇa XVI.31) | ||||

Usage in another language

Sundanese Cacarakan

Cacarakan is one of Sundanese language writing system, which means "similar to Carakan". It was officially used from 16 to 20 centuries. However, there are several places which use cacarakan. There are several orthographic difference to modern Javanese orthography:

- Vowel [ɨ] <eu> is written as ꦼꦴ or ◌ꦼꦵ (paneuleung) in cacarakan (there is no a such vowel in Javanese).

- Free vowel in cacarakan is written with aksara sora (Javanese: aksara swara) instead of aspirated ha. For example, a is written as ꦄ in cacarakan, instead of ꦲ in carakan.

- Free vowel of [i] is written as ꦄꦶ in cacarakan. However, it is possible to write it as ꦆ as in carakan.

- Consonant [ɲ] <ny> is written as ꦤꦾ for free standing ngalagena, while ꧀ꦚ as diacritic pasangan. Carakan ꦚ is not used in Cacarakan.

Similar to Balinese wianjana, Cacarakan ngalagena or wianjana consists of 18 letters instead of 20 letters in Carakan nglegena or wianjana. The two letters are ꦝ <ḍa> and ꦛ <ṭa>. For more details in seeing these differences, below is shown a table of the Sundanese Cacarakan and Javanese Carakan Ngalagena or Consonant Letters.

| ha | na | ca | ra | ka | da | dha | ta | sa | wa | la | pa | ḍa | ḍha | ja | jha | ya | nya | ma | ga | gha | ba | bha | tha | nga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jawa | ꦲ | ꦤ | ꦕ | ꦫ | ꦏ | ꦢ | ꦣ | ꦠ | ꦱ | ꦮ | ꦭ | ꦥ | ꦝ | ꦞ | ꦗ | ꦙ | ꦪ | ꦚ | ꦩ | ꦒ | ꦓ | ꦧ | ꦨ | ꦛ | ꦔ |

| ha | na | ca | ra | ka | da | ta | sa | wa | la | pa | ḍa/ḍha | ja | ya | nya | ma | ga | ba | tha | nga | ||||||

| Sunda | ꦲ | ꦤ | ꦕ | ꦫ | ꦏ | ꦣ | ꦠ | ꦱ | ꦮ | ꦛ | ꦥ | ꦗ | ꦪ | ꦤꦾ | ꦩ | ꦒ | ꦧ | ꦔ |

From the table it can be seen that the letter /dha/ in Carakan (Javanese) is used to represent the sound "da" in Cacarakan (Sundanese). Whereas for produces the sound "nya", Cacarakan (Sundanese) uses a series of letters /a/ plus a pengkal (Carakan). Sundanese Cacarakan uses the same letter pairs as Carakan, with the same writing rules. It's just different at times giving sandhangan (Carakan) or rarangkén (Cacarakan) used modified rules to produce Sundanese vowel sounds.

| Latin | ka | ga | nga | ca | ja | nya | ta | da | na | pa | ba | ma | ya | ra | la | wa | sa | ha |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cacarakan | ꦏ | ꦒ | ꦔ | ꦕ | ꦗ | ꦤꦾ | ꦠ | ꦣ | ꦤ | ꦥ | ꦧ | ꦩ | ꦪ | ꦫ | ꦭ | ꦮ | ꦱ | ꦲ |

| Pasangan | ꧀ꦏ | ꧀ꦒ | ꧀ꦔ | ꧀ꦕ | ꧀ꦗ | ꧀ꦚ | ꧀ꦠ | ꧀ꦣ | ꧀ꦤ | ꧀ꦥ | ꧀ꦧ | ꧀ꦩ | ꧀ꦪ | ꧀ꦫ | ꧀ꦭ | ꧀ꦮ | ꧀ꦱ | ꧀ꦲ |

| Latin | a | i | u | é | o | e | eu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cacarakan | ꦄ | ꦄꦶ /ꦆ | ꦈ | ꦌ | ꦎ | ꦄꦼ | ꦄꦼꦴ/ꦄꦼꦵ |

| Pasangan | ◌꧀ꦲ꦳ | ◌꧀ꦲ꦳ꦶ | ◌꧀ꦲ꦳ꦸ | ꦺ꧀ꦲ꦳ | ◌꧀ꦲ꦳ꦴ | ◌꧀ꦲ꦳ꦼ | ◌꧀ꦲ꦳ꦼꦴ/◌꧀ꦲ꦳ꦼꦵ |

In the Cacarakan swara/sora script the letter /i/ is written with a series of letters /a/ added with wulu (Carakan) or panghulu (Cacarakan). In the Javanese Carakan alphabet no special vowels are used for the sound /e/ (pepet), while in Cacarakan the letters /e/ pepet are written independently in a series the letter /a/ is added with pepet (Cacarakan) or pamepet (Cacarakan). Another vowel that appears is to describe the sound [ö] or the letter / eu / that quite dominant used in Sundanese. The letter /eu/ is written with a series of letters / a / added by tarung (Carakan) and pepet (Carakan) or simply called paneuleung in the term Sundanese Cacarakan.

| Latin | -a | -i | -u | -é | -o | -e | -eu | -ng | -h | -r | -y- | -r- | pamaéh (ø) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cacarakan | - | ꦶ | ꦸ | ꦺ | ꦺꦴ | ꦼ | ꦼꦴ/◌ꦼꦵ | ꦁ | ꦃ | ꦂ | ꦾ | ꦿ | ꧀ |

| Latin | ka | ki | ku | ké | ko | ke | keu | kang | kah | kar | kya | kra | k |

| Cacarakan | ꦏ | ꦏꦶ | ꦏꦸ | ꦏꦺ | ꦏꦺꦴ | ꦏꦼ | ꦏꦼꦴ/ꦏꦼꦵ | ꦏꦁ | ꦏꦃ | ꦏꦂ | ꦏꦾ | ꦏꦿ | ꦏ꧀ |

| Arabic | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cacarakan | ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ |

| Cacarakan | koma

(comma) |

titik

(dot) |

pipa

(numbers divider) |

adeg-adeg

(a starter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ꧈ | ꧉ | ꧇ | ꧋ |

Madurese Carakan

In Madurese language, Javanese script is called Carakan Madhurâ or Carakan Jhâbân (script derived from Javanese). If in Javanese language each character can represent the sound /a /or /ɔ /, then in Madurese language it represents the sound /a /or /ɤ /. The carakan Madhurâ form itself consists of aksara ghâjâng (aksara nglegena), aksara rajâ or murdâ (aksara murda), aksara sowara or swara (aksara swara), and aksara rèka'an (aksara rékan). There is also pangangghuy (sandhangan) which consists of pangangguy aksara (sandhangan swara), pangangghuy panyèghek (sandhangan panyigeging wanda), and pangangghuy panambâ (sandhangan wyanjana).[64][65][66][67][68]

Comparison with Javanese

Broadly speaking, there is no significant difference with the Javanese. However, in the Madurese language there is no difference in the use of aspirate and tanaspirate consonants.[69]

| ha | na | ca | ra | ka | da | dha | ta | sa | wa | la | pa | ḍa | ḍha | ja | jha | ya | nya | ma | ga | gha | ba | bha | tha | nga | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jawa | ꦲ | ꦤ | ꦕ | ꦫ | ꦏ | ꦢ | ꦣ | ꦠ | ꦱ | ꦮ | ꦭ | ꦥ | ꦝ | ꦞ | ꦗ | ꦙ | ꦪ | ꦚ | ꦩ | ꦒ | ꦓ | ꦧ | ꦨ | ꦛ | ꦔ |

| ha | na | ca | ra | ka | da/dha | ta | sa | wa | la | pa | ḍa/ḍha | ja/jha | ya | nya | ma | ga/gha | ba/bha | tha | nga | ||||||

| Madura | ꦲ | ꦤ | ꦕ | ꦫ | ꦏ | ꦢ | ꦠ | ꦱ | ꦮ | ꦛ | ꦥ | ꦝ | ꦗ | ꦪ | ꦚ | ꦩ | ꦒ | ꦧ | ꦛ | ꦔ |

Aksara rèka'an in Madurese language as taught in schools has only five characters, while in Madoereesche Spraakkunst and Sorat tjarakan Madurah there are seven and nine respectively:[70][71]

| ha | kha | dza | fa/va | za | gha | 'a | ta | sya | la | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Javanese | ꦲ꦳ | ꦏ꦳ | ꦢ꦳ | ꦥ꦳ | ꦗ꦳ | ꦒ꦳ | ꦔ꦳ | ꦠ꦳ | ꦯ꦳ | ꦭ꦳ |

| Arabic | ح | خ | ذ | ف | ز | غ | ع | ط | ش | ل |

| Dutch | h | ch | f/v | g | ||||||

| Example | ꦲ꦳ꦺꦴꦏꦺꦴꦩ꧀ | ꦲꦏ꦳ꦺꦫꦠ꧀ | ꦢ꦳ꦶꦏ꧀ꦏꦺꦂ | ꦭꦥ꦳ꦭ꧀ | ꦗ꦳ꦏꦠ꧀ | ꦒ꦳ꦲꦶꦧ꧀ | ꦔ꦳ꦏꦺꦫꦠ꧀ | ꦠ꦳ꦫꦺꦏ꧀ | ꦯ꦳ꦫꦠ꧀ | ꦭ꦳ꦲꦶꦧ꧀ |

| Transliteration | hokom | akhèrat | dzikkèr | lafal | zâkat | ghaib | 'akèrat | tarèk | syarat | laib |

Another difference is the use of wignyan which in Javanese functions as the -h suffix, while in Madurese it becomes the -' as shown in the following table:[64][72]

| Pangangghuy aksara | Pangangghuy panyèghek | Pangangghuy panambâ | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| i | è | o | u | e | -ng | -r | -' | pemati | -r- | -re | -y- | -l- | -w- |

| ꦶ | ꦺ | ꦺꦴ | ꦸ | ꦼ | ꦁ | ꦂ | ꦃ | ꧀ | ꦿ | ꦽ | ꦾ | ꧀ꦭ | ꧀ꦮ |

| cèthak | lèngè | lèngè-longo | soko | petpet | cekcek | lajâr | bisat | papatèn | pèḍer | perper | sokomaljâ | la rangkep | wa rangkep |

| pi | pè | po | pu | pe | pang | par | pa' | p | pra | pre | pya | pla | pwa |

| ꦥꦶ | ꦥꦺ | ꦥꦺꦴ | ꦥꦸ | ꦥꦼ | ꦥꦁ | ꦥꦂ | ꦥꦃ | ꦥ꧀ | ꦥꦿ | ꦥꦿ | ꦥꦾ | ꦥ꧀ꦭ | ꦥ꧀ꦮ |

Unicode

Javanese script was added to the Unicode Standard in October, 2009 with the release of version 5.2.

The Unicode block for Javanese is U+A980–U+A9DF. There are 91 code points for Javanese script: 53 letters, 19 punctuation marks, 10 numbers, and 9 vowels:

| Javanese[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+A98x | ꦀ | ꦁ | ꦂ | ꦃ | ꦄ | ꦅ | ꦆ | ꦇ | ꦈ | ꦉ | ꦊ | ꦋ | ꦌ | ꦍ | ꦎ | ꦏ |

| U+A99x | ꦐ | ꦑ | ꦒ | ꦓ | ꦔ | ꦕ | ꦖ | ꦗ | ꦘ | ꦙ | ꦚ | ꦛ | ꦜ | ꦝ | ꦞ | ꦟ |

| U+A9Ax | ꦠ | ꦡ | ꦢ | ꦣ | ꦤ | ꦥ | ꦦ | ꦧ | ꦨ | ꦩ | ꦪ | ꦫ | ꦬ | ꦭ | ꦮ | ꦯ |

| U+A9Bx | ꦰ | ꦱ | ꦲ | ꦳ | ꦴ | ꦵ | ꦶ | ꦷ | ꦸ | ꦹ | ꦺ | ꦻ | ꦼ | ꦽ | ꦾ | ꦿ |

| U+A9Cx | ꧀ | ꧁ | ꧂ | ꧃ | ꧄ | ꧅ | ꧆ | ꧇ | ꧈ | ꧉ | ꧊ | ꧋ | ꧌ | ꧍ | ꧏ | |

| U+A9Dx | ꧐ | ꧑ | ꧒ | ꧓ | ꧔ | ꧕ | ꧖ | ꧗ | ꧘ | ꧙ | ꧞ | ꧟ | ||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

Gallery

|

See also

Notes

- ^ VOC established a paper mill in Java between 1665–1681. However, the mill was not able to fulfill paper demands of the island and so stable paper supply continued to rely in shipments from Europe.[14]

- ^ Among 19th century European scholars, the style of the Surakartan scribes is agreed as the most refined among the various regional Javanese hand. So much so that prominent Javanese scholars such as J. F. C. Gericke frequently suggested that the Surakartan style should be used as the ideal shape to which a proper Javanese type design could be based upon.[20]

- ^ In 1920, the director of Balai Poestaka D. A. Rinkes wrote in a foreword for the Javanese book catalog in the collection of Bataviaasch Genootschap as follow:

Bovendien is voor den druk het Latijnsche lettertype gekozen, hetgeen de zaak voor Europeesche gebruikers aanzienlijk vergemakkelijkt, voor Inlandsche belangstellended geenszins een bezwaar oplevert, aangezien de Javaansche taal, evenals bereids voor het Maleisch en het Soendaneesch gebleken is, zeker niet minder duidelijk in Latijnsch type dan in het Javaansche schrift is weer te geven. Daarbij zijn de kosten daarmede ongeveer 1⁄3 van druk in Javaansch karakter, aangezien drukwerk in dat type, dat bovendien niet ruim voorhanden is, 1+1⁄2 à 2 x kostbaarder (en tijdroovender) uitkomt dan in Latijnsch type, mede doordat het niet op de zetmachine kan worden gezet, en een pagina Javaansch type sleechts ongeveer de helft aan woorden bevat van een pagina van denzelfden tekst in Latijnsch karakter.[24]

Furthermore, a choice was made for printing in roman letter-type, which considerably simplifies matters for European users, and for interested Natives presents no difficulty at all, seeing that the Javanese language, just as has already been shown for Malay and Sundanese, can be rendered no less clearly in roman type than in the Javanese script. In this way the costs are about one third of printing in Javanese characters, seeing that printing in that type, which furthermore is not readily available, is one and a half times to twice as expensive (and more time-consuming) than in roman type, also because it cannot be set on a setting-machine, and one page of Javanese type only contains about half the number of words on one page of the same text in roman script.

—Poerwa Soewignja dan Wirawangsa (1920:4), quoted by Molen (1993:83) —Robson (2011:25) - ^ In comparison, during the Japanese occupation of Cambodia of the same time period, the Japanese government banned the Khmer romanization scheme proposed by the earlier French colonial government and restored the use of Khmer script as the official script of Cambodia.[26]

- ^ usually used in transcription of Balinese lontars for writing the sacred syllable ong ꦎꦀ

References

- ^ Poerwadarminta, W.J.S (1939). Baoesastra Djawa (in Javanese). Batavia: J.B. Wolters. ISBN 0834803496.

- ^ Behrend 1996, pp. 161.

- ^ a b Everson 2008, pp. 1.

- ^ Holle, K F (1882). "Tabel van oud-en nieuw-Indische alphabetten". Bijdrage tot de Palaeographie van Nederlandsch-Indie. Batavia: W. Bruining.

- ^ Casparis, J G de (1975). Indonesian Palaeography: A History of Writing in Indonesia from the Beginnings to C. A.D. 1500. Vol. 4. Brill. ISBN 9004041729.

- ^ Campbell, George L. (2000). Compendium of the World's Languages. Vol. 1. New York: Routledge.

- ^ a b Behrend 1996, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Behrend 1996, pp. 162.

- ^ Moriyama 1996, pp. 166.

- ^ Moriyama 1996, pp. 167.

- ^ a b Behrend 1996, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Hinzler, H I R (1993). "Balinese palm-leaf manuscripts". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 149 (3): 438–473. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003116.

- ^ a b Behrend 1996, pp. 165–167.

- ^ a b Teygeler, R (2002). "The Myth of Javanese Paper". In R Seitzinger (ed.). Timeless Paper. Rijswijk: Gentenaar & Torley Publishers. ISBN 9073803039.

- ^ a b Molen 2000, pp. 154–158.

- ^ Behrend 1996, pp. 172.

- ^ Behrend 1996, pp. 172–175.

- ^ Molen 2000, pp. 137.

- ^ Molen 2000, pp. 136–140.

- ^ Molen 2000, pp. 149–154.

- ^ Astuti, Kabul (October 2013). Perkembangan Majalah Berbahasa Jawa dalam Pelestarian Sastra Jawa. International Seminar On Austronesian - Non Austronesian Languages and Literature. Bali.

- ^ Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

- ^ Robson 2011, pp. 25.

- ^ Molen 1993, pp. 83.

- ^ Hadiwidjana, R. D. S. (1967). Tata-sastra: ngewrat rembag 4 bab : titi-wara tuwin aksara, titi-tembung, titi-ukara, titi-basa. U.P. Indonesia.

- ^ Chandler, David P (1993). A History of Cambodia. Silkworm books. ISBN 9747047098.

- ^ Wahab, Abdul (October 2003). Masa Depan Bahasa, Sastra, dan Aksara Daerah (PDF). Kongres Bahasa Indonesia VIII. Vol. Kelompok B, Ruang Rote. Pusat Bahasa Departemen Pendidikan Indonesia. pp. 8–9.

- ^ Florida, Nancy K (1995). Writing the Past, Inscribing the Future: History as Prophesy in Colonial Java. Duke University Press. p. 37. ISBN 9780822316220.

- ^ Mustika, I Ketut Sawitra (12 October 2017). Atmasari, Nina (ed.). "Alumni Sastra Jawa UGM Bantu Koreksi Tulisan Jawa pada Papan Nama Jalan di Jogja". Yogyakarta: SOLOPOS.com. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Eswe, Hana (13 October 2019). "Penunjuk Jalan Beraksara Jawa Salah Tulis Dikritik Penggiat Budaya". Grobogan: SUARABARU.id. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Siti Fatimah (27 February 2020). "Bangkitkan Kongres Bahasa Jawa Setelah Mati Suri". Bantul: RADARJOGJA.co. Archived from the original on 19 June 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- ^ a b c Everson 2008, pp. 1–2.

- ^ a b c Poerwadarminta, W J S (1930). Serat Mardi Kawi (PDF). Vol. 1. Solo: De Bliksem. pp. 9–12.

- ^ Robson 2011, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Everson 2008, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Rochkyatmo 1996, pp. 35–41.

- ^ Rochkyatmo 1996, pp. 8–11.

- ^ Rochkyatmo 1996, pp. 51–58.

- ^ a b c Woodard, Roger D (2008). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0521684941.

- ^ Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 19–24.

- ^ Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 13–15.

- ^ Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 20.

- ^ a b Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Zoetmulder, Petrus Josephus (1982). Robson, Stuart Owen (ed.). Old Javanese-English Dictionary. Nijhoff. p. 143, entry 4. ISBN 9024761786.

- ^ Zoetmulder, Petrus Josephus (1982). Robson, Stuart Owen (ed.). Old Javanese-English Dictionary. Nijhoff. p. 1191, entry 11. ISBN 9024761786.

- ^ Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Hollander, J J de (1886). Handleiding bij de beoefening der Javaansche Taal en Letterkunde. Leiden: Brill. p. 3.

- ^ Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 24–28.

- ^ Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Everson 2008, pp. 2.

- ^ Everson 2008, pp. 4.

- ^ Darusuprapta 2002, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c Everson 2008, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Everson 2008, pp. 5.

- ^ Behrend 1996, pp. 188.

- ^ a b Behrend 1996, pp. 190.

- ^ Behrend 1996, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Saktimulya, Sri Ratna (2016). Naskah-naskah Skriptorium Pakualaman. Jakarta: Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia. ISBN 978-6024242282.

- ^ Serat Katoerangganing Koetjing (ꦱꦼꦫꦠ꧀ꦏꦠꦸꦫꦁꦒꦤ꧀ꦤꦶꦁꦏꦸꦠ꧀ꦕꦶꦁ), printed by GCT Van Dorp & Co in Semarang, 1871. Google Books scan from the collection of Dutch National Library, No 859 B33.

- ^ Kern, Hendrik (1900). Rāmāyaṇa Kakawin. Oudjavaansch heldendicht. 's Gravenhage: Martinus Nijhoff.

- ^ Tinggen, I Nengah (1993). Pedoman Perubahan Ejaan Bahasa Bali dengan Huruf Latin dan Huruf Bali. Singaraja: UD. Rikha. p. 7.

- ^ Simpen, I Wayan (1994). Pasang Aksara Bali. Upada Sastra. p. 44.

- ^ Sutjaja, I Gusti Made (2006). Kamus Inggris, Bali, Indonesia. Lotus Widya Suari bekerjasama dengan Penerbit Univ. Udayana. ISBN 9798286855.

- ^ a b Hamzah, Bambang Hartono; Sayunani, Isya; Gani, Abdul; Dradjid, Rusliy; Zaini, HM (2014). Ghazali, A. Syukur; Poerno, Heru Asri (eds.). Sekkar Anom I (in Madurese). Dinas Pendidikan Provinsi Jawa Timur. p. 148.

- ^ Sukardi, A. (2005). Kasustraan Madura Kembang Sataman (in Madurese) (2 ed.). Jember: Dinas Pendidikan Kabupaten Jember.

- ^ Kiliaan 1897, p. 89.

- ^ Wedhawati (2001). Tata Bahasa Jawa Mutakhir. Jakarta: Pusat Bahasa. pp. 39–40. ISBN 9796851415.

- ^ Davies, William D. (2010). Id = mflajowwD5oC & pg = PA53 A Grammar of Madurese. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter. p. 53. ISBN 9783110224443.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ Kiliaan 1897.

- ^ Hamzah, Bambang Hartono; Sayunani, Isya; Gani, Abdul; Zaini, Rusliy; Dradjid, H.M. (2015). Sekkar Anom 2 (in Madurese). Surabaya: Dinas Pendidikan Provinsi Jawa Timur. p. 155.

- ^ Kiliaan 1897, p. 97.

- ^ Ashadi, Moh. Makhfud; al Farouk, Ghazi (1992). Kosa Kata Basa Madura (in Madurese). Surabaya: Sarana Ilmu.

Bibliography

- Arps, B (1999). "How a Javanese Gentleman put his Library in Order". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 155 (3): 416–469. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003871. hdl:1887/15216.

- Behrend, T E (1993). "Manuscript Production in Nineteenth Century Java. Codicology and the Writing of Javanese Literary History". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 149 (3): 407–437. doi:10.1163/22134379-90003115.

- Behrend, T E (1996). "Textual Gateways: the Javanese Manuscript Tradition". In Ann Kumar; John H. McGlynn (eds.). Illuminations: The Writing Traditions of Indonesia. Jakarta: Lontar Foundation. ISBN 0834803496.

- Everson, Michael (6 March 2008). "Proposal for encoding the Javanese script in the UCS" (PDF). Iso/Iec Jtc1/Sc2/Wg2 (N3319R3). Unicode.

- Kiliaan, H. N. (1897). Madoereesche Spraakkunst (in Dutch). Batavia: Landsdrukkerij.

- Molen, Willem van der (1993). Javaans Schrift (in Dutch). Vol. Semaian 8. Leiden: Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden. ISBN 90-73084-09-1.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Molen, Willem van der (2000). "Hoe Heft Zulks Kunnen Geschieden? Het Begin van de Javaanse Typografie". In Willem van der Molen (ed.). Woord en Schrift in de Oost. De betekenis van zending en missie voor de studie van taal en literatuur in Zuidoost-Azie (in Dutch). Vol. Semaian 19. Leiden: Vakgroep Talen en Culturen van Zuidoost-Azië en Oceanië, Rijksuniversiteit te Leiden. pp. 132–162. ISBN 9074956238.

- Moriyama, Mikihiro (June 1996). "Discovering the 'Language' and the 'Literature' of West Java: An Introduction to the Formation of Sundanese Writing in 19th Century West Java" (PDF). Southeast Asian Studies. 34 (1): 151–183.

- Robson, Stuart Owen (2011). "Javanese script as cultural artifact: Historical background". RIMA: Review of Indonesian and Malaysian Affairs. 45 (1–2): 9–36.

- Rochkyatmo, Amir (1 January 1996). Pelestarian dan Modernisasi Aksara Daerah: Perkembangan Metode dan Teknis Menulis Aksara Jawa (PDF) (in Indonesian). Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan.

Orthographical guides

- Koemisi Kasoesastran ing Sriwedari, Soerakarta (1926). Wawaton Panjeratipoen Temboeng Djawi mawi Sastra Djawi dalasan Angka. Kongres Sriwedari (in Javanese). Weltevreden: Landsdrukkerij. Also known as Wewaton Sriwedari and Paugeran Sriwedari.

- Darusuprapta (2002). Pedoman Penulisan Aksara Jawa (in Indonesian). Yogyakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Nusantara bekerja sama dengan Pemerintahan Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta, Daerah Tingkat I Jawa Tengah, dan Daerah Tingkat I Jawa Tengah. ISBN 979-8628-00-4.

Sanskrit and Kawi

- Poerwadarminta, W J S (1930). Serat Mardi Kawi (in Javanese). Vol. 1. Solo: De Bliksem.

- Poerwadarminta, W J S (1931). Serat Mardi Kawi (in Javanese). Vol. 2. Solo: De Bliksem.

- Poerwadarminta, W J S (1931). Serat Mardi Kawi (in Javanese). Vol. 3. Solo: De Bliksem.

Sundanese

- Holle, K F (1862). Soendasch spel- en lees boek, met Soendasche letter. Batavia: Lands-drukkerij.

External links

Digital collection

- British Library manuscript collection

- National Library of Indonesia manuscript collection

- Yayasan Sastra Lestari manuscript collection

- Widyapustaka references collection Archived 14 December 2021 at the Wayback Machine

Digitized manuscripts

- A debt written on a piece of lontar (1708) British Library collection no. Sloane MS 1403E

- Babad Mataram and Babad ing Sangkala (1738) koleksi British Library no. MSS Jav 36

- A Malay-Javanese-Maduran language word list from early 19th century, British Library collection no. MSS Malay A 3

- An assortment of documents from the Kraton of Yogyakarta (1786–1812) British Library collection no. Add Ms 12341

- Papakem Pawukon from Bupati Sepuh Demak of Bogor (1814) British Library collection no. Or 15932

- Wejangan Hamengkubuwana I (1812) British Library collection no. Add MS 12337

- Raffles Paper - vol III (1816) a collection of Letters received by Raffles from the rules of the Malay archipelago, British Library collection no. Add MS 45273

- Serat Jaya Lengkara Wulang (1803) British Library collection no. MSS Jav 24

- Serat Selarasa (1804) British Library collection no. MSS Jav 28

- Usana Bali Archived 19 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine (1870) a Javanese copy of a Balinese lontar of the same title, National Library of Indonesia collection no. CS 152

- Dongèng-dongèng Pieuntengen (1867) a collection of Sundanese tales written in the Javanese script compiled by Muhammad Musa

Others

- Unicode proposal for the Javanese script

- Unicode documentation for the behavior of KERET diacritic

- Unicode documentation for the behavior of CAKRA diacritic

- Unicode documentation for the behavior of PENGKAL diacritic

- Unicode documentation for the behavior of TOLONG diacritic

- British Library Asian-African Studies blog, Javanese topic

- Javanese script transliterator by Benny Lin

- Hana - Javanese Script Transliterator by Dan

- Download Javanese fonts in Tuladha Jejeg Archived 27 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine, Aksara di Nusantara, or Google Noto

![Cover of the Kajawèn [id] magazine, issue 65, 16 August 1933](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/99/Kajawen_1933-08-16-1_sampul.jpg/217px-Kajawen_1933-08-16-1_sampul.jpg)

![Kekancingan [id] document issued by the Kraton of Yogyakarta in 1935, Dewantara Kirti Griya Museum collection](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ed/TDKGM_01.147_Koleksi_dari_Perpustakaan_Museum_Tamansiswa_Dewantara_Kirti_Griya.pdf/page1-189px-TDKGM_01.147_Koleksi_dari_Perpustakaan_Museum_Tamansiswa_Dewantara_Kirti_Griya.pdf.jpg)