Nuclear weapons of the United States

This article documents a current event. Information may change rapidly as the event progresses, and initial news reports may be unreliable. The latest updates to this article may not reflect the most current information. (April 2007) |

| United States | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nuclear program start date | October 21, 1939 |

| First nuclear weapon test | July 16, 1945 |

| First thermonuclear weapon test | November 1, 1952 |

| Last nuclear test | September 23, 1992 |

| Largest yield test | 15 Megatons (October 31, 1954) |

| Total tests | 1,054 detonations |

| Peak stockpile | 32,193 warheads (1966) |

| Current stockpile | 5,735 active, 9,960 total |

| Maximum missile range | 13,000 kilometers/8,100 miles (land) 12,000 kilometers/7,500 miles (sub) |

The United States was the first country in the world to successfully develop nuclear weapons, and is the only country to have used them in war against another nation. During the Cold War it conducted over a thousand nuclear tests and developed many long-range weapon delivery systems. It maintains an arsenal of about ten thousand warheads to this day [1], as well as facilities for their construction and design, though many of the Cold War facilities have since been deactivated and are sites for environmental remediation.

Development history

Manhattan Project

The United States of America first began developing nuclear weapons during World War II under the order of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1939, motivated by a fear that they were engaged in a potential race with Nazi Germany to develop such a weapon. After a slow start under the direction of the National Bureau of Standards, at the urging of British scientists and American administrators the program was put under the Office of Scientific Research and Development, where in 1942 it was officially transferred under the auspices of the U.S. Army and became known as the Manhattan Project. Under the direction of General Leslie Groves, over thirty different sites were constructed for the research, production, and testing of components related to bomb making. These included the scientific laboratory, Los Alamos (in New Mexico), under the direction of physicist Robert Oppenheimer, a plutonium production facility, Hanford (in Washington), and a uranium enrichment facility, Oak Ridge (in Tennessee).

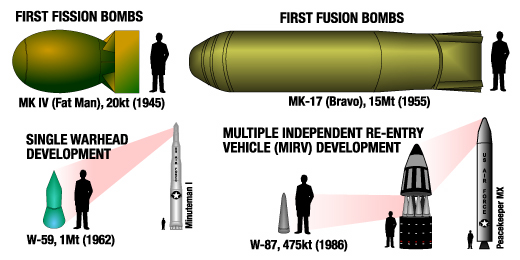

By investing heavily both in breeding plutonium in early nuclear reactors, and in both the electromagnetic and gaseous diffusion enrichment processes for the production of uranium-235, the United States was able by mid-1945 to develop three usable weapons. A plutonium-implosion design weapon was tested on July 16, 1945 ("Trinity"), with around a 20 kiloton yield. On the orders of President Harry S. Truman, on August 6 of the same year a uranium-gun design bomb ("Little Boy") was used against the city of Hiroshima, Japan, and on August 9 a plutonium-implosion design bomb ("Fat Man") was used against the city of Nagasaki, Japan. The two weapons killed approximately 250,000 Japanese citizens outright, and many more thousands have died over the years from radiation sickness and related cancers.

Cold War

In the postwar period, the United States was soon engaged in a nuclear arms race against the Soviet Union, who it feared had strong territorial ambitions in postwar Europe and potential ideological ambitions to wage war against the United States. The U.S. invested heavily in a continued program of weapons research, development, and production, under the auspices of the civilian-run Atomic Energy Commission. Research also commenced in delivery systems, including the improvement of bomber aircraft and the development of rocketry for use with nuclear systems.

In 1950, in response to the detonation of the USSR's first fission weapon in 1949 ("Joe 1"), Truman ordered a crash research program towards developing thermonuclear weapons. At that point the weapons were still purely theoretical, with no method known for successfully igniting a nuclear fusion reaction. After a theoretical breakthrough by the mathematician Stanislaw Ulam and physicist Edward Teller, however, workable method was developed and tested in the "Ivy Mike" shot in November 1952, with a yield of 10 megatons. A deployable version of the Teller–Ulam design was tested in the "Castle Bravo" shot of February 1954, with a yield of 15 megatons, over twice the projected expectations. Because of this error in calculation and unfortunate changes in weather conditions, the "Bravo" shot resulted in the depositing of large amounts of nuclear fallout onto the Marshall Islands at the test site in the Pacific. An evacuation ensued, but many of the natives exposed suffered from cancers and a high incidence of birth defects. A Japanese fishing boat was additionally exposed and resulted in one death from radiation sickness, which gained considerable international attention.

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s the United States continued on its path, developing intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and submarine launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs), with which to hold a credible deterrence against the USSR. In this period the U.S. stockpile of weapons increased exponentially to its maximum point of over 32,000 warheads in 1966.[2] The generally agreed upon point at which the U.S. came closest to nuclear war with the USSR occurred during the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962.

In the 1970s and 1980s, warhead production slowed somewhat though innovation in warhead design allowed for new generations of delivery systems such as multiple independently targetable reentry vehicles (MIRVs) to be produced. Since this advance in the miniaturization of thermonuclear weapons in the mid-1970s, most experts and weapons scientists have said that most nuclear weapons design was focused on small improvements and modifications rather than any radical changes.

In the 1980s, under President Ronald Reagan, a reinvigoration of the arms race took place, and also introduced the extensive advocacy of the use of nuclear and non-nuclear approaches to missile defense through the Strategic Defense Initiative. For technical and political reasons, however, funding was eventually cut back heavily on this program.

Post-Cold War

After the end of the Cold War following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the U.S. nuclear program was heavily curtailed, halting its program of nuclear testing, ceasing in the production of new nuclear weapons, and reducing its stockpile by half by the mid-1990s under President Bill Clinton. Many of its former nuclear facilities were shut down, and their sites became targets of extensive environmental remediation. Much of the former efforts towards the production of weapons became involved in the program of stockpile stewardship, attempting to predict the behavior of aging weapons without using full-scale nuclear testing. Increased funding also was put into anti-nuclear proliferation programs, such as helping the states of the former Soviet Union eliminate their former nuclear sites, and assist Russia in their efforts to inventory and secure their inherited nuclear stockpile. As of February 2006, over $990 million were paid under the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990 to U.S. citizens exposed to nuclear hazards as a result of the U.S. nuclear weapons program, and by 1998 at least $759 million was paid to the Marshallese Islanders in compensation for their exposure to U.S. nuclear testing, and over $15 million was paid to the Japanese government following the exposure of its citizens and food supply to nuclear fallout from the 1954 "Bravo" test.[3][4]

During the presidency of George W. Bush, and especially after the September 11 terrorist attacks of 2001, rumors have circulated in major news sources that the U.S. has been considering design of new nuclear weapons ("bunker-busting nukes"), and potentially the resumption of nuclear testing for reasons of stockpile stewardship, and non-nuclear missile defense has received additional funding as well.

Between 1940 and 1996, the U.S. spent at least $5.8 trillion (in 1996 dollars) on nuclear weapons development.[5] Over half of this was spent on building delivery mechanisms for the weapons, around 0.02% of it (the lowest category of expenditure) was spent on Congressional oversight. $365 billion was spent on nuclear waste management and environmental remediation. Between 1945 and 1990, more than 70,000 total warheads were developed, in over 65 different varieties, ranging in yield from around .01 kilotons (such as the man-portable Davy Crockett shell) to the 25 megaton B41 bomb[6].

Nuclear testing

Between July 16, 1945, and September 23, 1992, the United States maintained a program of vigorous nuclear testing, with the exception of a moratorium between November 1958 and September 1961. A total of (by official count) 1,054 nuclear tests and two nuclear attacks were conducted, with over 100 of them taking place at sites in the Pacific Ocean, over 900 of them at the Nevada Test Site, and ten on miscellaneous sites in the United States (Alaska, Colorado, Mississippi, and New Mexico).[7] Until November 1962, the vast majority of the U.S. tests were atmospheric (that is, above-ground); after the acceptance of the Partial Test Ban Treaty all testing was regulated underground, in order to prevent the dispersion of nuclear fallout.

The U.S. program of atmospheric nuclear testing exposed a number of the population to the hazards of fallout. Estimating exact numbers, and the exact consequences, of people exposed has been medically very difficult, with the exception of the high exposures of Marshallese Islanders and Japanese fisherman in the case of the "Castle Bravo" incident in 1954. A number of groups of U.S. citizens — especially farmers and inhabitants of cities downwind of the Nevada Test Site and U.S. military workers at various tests — have sued for compensation and recognition of their exposure, many successfully. The passing of the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990 allowed for a systematic filing of compensation claims in relation to testing as well as those employed at nuclear weapons facilities. As of March 2006 over a billion dollars total has been given in compensation, with over $485 million going to "downwinders".

A few notable U.S. nuclear tests include:

- The "Trinity" test on July 16, 1945, was the first-ever test of a nuclear weapon (yield of around 20 kt).

- The Operation Crossroads series in July 1946, was the first postwar test series and one of the largest military operations in U.S. history.

- The Operation Greenhouse shots of May 1951 included the first boosted fission weapon test ("Item") and a scientific test which proved the feasibility of thermonuclear weapons ("George").

- The "Ivy Mike" shot of November 1, 1952, was the first full test of a Teller-Ulam design "staged" hydrogen bomb, with a yield of 10 megatons. It was not a deployable weapon, however — with its full cryogenic equipment it weighed some 82 tons.

- The aforementioned "Castle Bravo" shot of October 31, 1954, was the first test of a deployable (solid fuel) thermonuclear weapon, and also (accidentally) the largest weapon ever tested by the United States (15 megatons). It was also the single largest U.S. radiological accident in connection with nuclear testing. The unanticipated yield, and a change in the weather, resulted in nuclear fallout spreading eastward onto the inhabited Rongelap and Rongerik atolls, which were soon evacuated. Many of the Marshall Islands natives have since suffered from birth defects and have received some compensation from the federal government. A Japanese fishing boat, the Fifth Lucky Dragon, also came into contact with the fallout, which caused many of the crew to grow ill; one eventually died.

- Shot "Argus I" of Operation Argus, on August 27, 1958, was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon in outer space when a 1.7-kiloton warhead was detonated at 200 kilometers' altitude during a series of high altitude nuclear explosions.

- Shot "Frigate Bird" of Operation Dominic I on May 6, 1962, was the first and only U.S. test of an operational ballistic missile with a live nuclear warhead (yield of 600 kilotons), at Christmas Island. In general, missile systems were tested without live warheads and warheads were tested separately for safety concerns. In the early 1960s, however, there mounted technical questions about how the systems would behave under combat conditions (when they were "mated", in military parlance), and this test was meant to dispel these concerns. However, the warhead had to be somewhat modified before its use, and the missile was only a SLBM (and not an ICBM), so by itself it did not satisfy all concerns. (Mackenzie 1990)

- Shot "Sedan" of Operation Storax on July 6, 1962 (yield of 104 kilotons), was an attempt at showing the feasibility of using nuclear weapons for "civilian" and "peaceful" purposes as part of Operation Plowshare. In this instance, a 1280-feet-in-diameter and 320-feet-deep crater was created at the Nevada Test Site.

Delivery systems

The original weapons ("Little Boy" and "Fat Man") developed by the United States during the Manhattan Project were relatively large (the latter had a diameter of 5 feet) and heavy (around 5 tons each) weapons which required specially modified bomber planes to be adapted for their bombing missions against Japan, each of which could only carry one such weapon and only within a limited range. After these initial weapons, a considerable amount of money and research was conducted towards the goal of standardizing ("G.I. proofing") nuclear warheads (so that they did not require highly specialized experts to assemble them before use, as in the case with the idiosyncratic wartime devices) and miniaturization of the warheads for use in more variable delivery systems.

Through the aid of brainpower acquired through Operation Paperclip at the tail end of the European branch of World War II, the United States was able to embark on an ambitious program in rocketry. One of the first products of this was the development of rockets capable of holding nuclear warheads. The MGR-1 Honest John was the first of such weapons, developed in 1953 as a surface-to-surface missile with a 15 mile/25 kilometer maximum range. Because of their limited range, their potential use was heavily constrained (they could not, for example, threaten Moscow with an immediate strike).

Development of long-range bombers, such as the B-29 Superfortress, during World War II was continued during the Cold War period. The development of the B-52 Stratofortress in particular was able by the mid-1950s to carry a wide arsenal of nuclear bombs, each with different capabilities and potential use situations. Starting in 1946, the U.S. based its initial deterrence threat around the Strategic Air Command, which maintained a number of nuclear-armed bombers in the sky at all times, prepared to receive orders to attack the USSR whenever needed. This system was, however, tremendously expensive, both in natural resources and human resources, and raised the possibility of accidental or purposeful beginning of nuclear war, parodied famously in the 1964 film by Stanley Kubrick, Dr. Strangelove.

During the 1950s and 1960s, elaborate computerized early warning systems were developed to detect incoming Soviet attacks and to coordinate response strategies. During this same period, intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) systems were developed which could deliver a nuclear payload across vast distances, allowing the U.S. to house nuclear forces capable of hitting the Soviet Union in the American Midwest. Shorter-range weapons, including small "tactical" weapons, were fielded in Europe as well, including nuclear artillery and man-portable Special Atomic Demolition Munition. The development of submarine launched ballistic missile (SLBM) systems allowed for hidden nuclear submarines to covertly launch missiles at distant targets as well, making it virtually impossible for the Soviet Union to successfully launch a first strike attack against the United States which would not guarantee a deadly response.

Improvements in warhead miniaturization in the 1970s and 1980s allowed for the development of MIRVs — missiles which could carry multiple warheads, each of which could be separately targetable. The question of whether these missiles should be based on constantly rotating train tracks (so as to avoid being easily targeted by opposing Soviet missiles) or based in heavily fortified silos (to possibly withstand a Soviet attack) was a major political controversy in the 1980s (eventually the silos won out). MIRVed systems allowed the U.S. to make the Soviet missile defense economically unfeasible, as each offensive missile would require between three and ten defensive missiles to counter.

Additional developments in weapons delivery included cruise missile systems, which allowed a plane to fire a long-distance, low-flying nuclear-tipped missile towards a target from a relatively comfortable distance. This innovation would make missile defense additionally difficult, if not impossible.

The current delivery systems of the U.S. makes virtually any part of the globe within the reach of its nuclear arsenal. Though its land-based missile systems have a maximum range of 10,000 kilometers (less than worldwide), its submarine-based forces extend its reach from a coastline 12,000 kilometers inland. Additionally, the ability to refuel long-range bombers in flight and the use of aircraft carriers extends the possible range virtually indefinitely.

Public reactions

From the public debut of nuclear weapons during the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, they were a highly controversial technology among the citizens of the United States. While it appears that most Americans in the postwar period believed that they had, as claimed by the government, hastened the end of the war with Japan, even at that early period there were questions about the ethics of their use. In the immediate postwar period, much of the public debate was on the question of whether or not the U.S. should attempt to have a monopoly on the weapons — potentially encouraging a nuclear arms race — or whether or not it should relinquish them to an intergovernmental body (such as the newly created United Nations) or contribute to some other form of international control or information dispersal. According to the historian of science Spencer Weart, it was not until the development of multi-megaton hydrogen bombs in the 1950s that a belief that nuclear weapons could potentially end all life on the planet (especially through means of nuclear fallout, highlighted by the "Castle Bravo" accident) became common in American thought or cultural expression. For the most part, however, the vast majority of American citizens believed during this time that nuclear weapons were necessary in order to ward off the apparent threat from the Soviet Union.

During the 1960s, following the rise of political activism in the civil rights movement, the controversy over the Vietnam War, and the beginnings of the environmentalism movement, public anxiety related to nuclear weapons began to rise to the point of direct protest. While there is little evidence that these sentiments were felt or expressed by any more than a minority of the U.S. population, their expression became increasingly amplified, especially in relation to the health hazards of nuclear testing. After the cessation of American atmospheric nuclear testing, however, the sentiment against nuclear weapons in general lost much of its momentum. During the period of détente in the 1970s, marked by weapons reduction and restriction treaties between the U.S. and the USSR, much of the anxiety over nuclear weapons in the populace and activists was transferred towards protesting civilian nuclear power plants, according to Spencer Weart's analysis.

During the presidency of Ronald Reagan in the 1980s, public anti-nuclear weapons sentiment reached its highest point, spurred by the administration's strong anti-Soviet rhetoric, Strategic Defense Initiative, and apparent reinvigoration of the arms race. Again, however, the majority of the American populace generally felt the weapons were required for U.S. national security, even though they increasingly became the flashpoints of political controversies and concern. Anti-nuclear activists shifted to a strategy of describing in detail the results of a potential nuclear attack on the United States, and a number of prominent anti-nuclear films were developed during this period, typified by the controversial The Day After in 1983.

With the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the cessation of the arms race, U.S. public attitudes towards nuclear weapons became less polarized on the whole. Following the 9/11 attacks of 2001, however, concerns over whether the U.S. should develop new weapons have reinvigorated some of the older debates over their practicality, morality, and danger. The debate over the ethical implications of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, begun in private amongst scientists and statesmen during the war, has continued to this day, in the general public as well as amongst historians, military experts, and other scholars.

Accidents

The United States nuclear program has, since its inception, suffered from a number of accidents of varying forms, ranging from single-casualty research experiments (such as that of Louis Slotin during the Manhattan Project), to the nuclear fallout dispersion of the "Castle Bravo" shot in 1954, to the accidental dropping of nuclear weapons from aircraft ("broken arrows"). How close any of these accidents came to being "major" nuclear disasters is a matter of technical and scholarly debate and interpretation.

Weapons accidentally dropped by the United States include incidents near Atlantic City, New Jersey (1957), Savannah, Georgia (1958) (see Tybee Bomb), Goldsboro, North Carolina (1961), off the coast of Okinawa (1965), in the sea near Palomares, Spain (1966), and near Thule, Greenland (1968). In some of these cases (such as near Palomares), the explosive system of the fission weapon discharged, but did not trigger a nuclear chain reaction (safety features prevent this from easily happening), but did disperse hazardous nuclear materials across wide areas, necessitating expensive cleanup endeavors. Eleven American nuclear warheads are thought to be lost and unrecovered, primarily in submarine accidents.

The nuclear testing program resulted in a number of cases of fallout dispersion onto populated areas. The most significant of these was the aforementioned Castle Bravo test, which spread radioactive ash over an area of over one hundred miles, including a number of populated islands. The populations of the islands were evacuated but not before suffering radiation burns. They would later suffer long-term effects, such as birth defects and increased cancer risk. There were also instances during the nuclear testing program in which soldiers were exposed to overly high levels of radiation, which grew into a major scandal in the 1970s and 1980s, as many soldiers later suffered from what were claimed to be diseases caused by their exposures.

Many of the former nuclear facilities (see next section) produced significant environmental damages during their years of activity, and since the 1990s have been Superfund sites of cleanup and environmental remediation. The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990 allows for U.S. citizens exposed to radiation or other health risks through the U.S. nuclear program to file for compensation and damages.

Development agencies

The initial U.S. nuclear program was run by the National Bureau of Standards starting in 1939 under the edict of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Its primary purpose was to delegate research and dispense of funds. In 1940 the National Defense Research Committee (NDRC) was established, coordinating work under the Committee on Uranium among its other wartime efforts. In June 1941, the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD) was established, with the NDRC as one of its subordinate agencies, which enlarged and renamed the Uranium Committee as the Section on Uranium. In 1941, NDRC research was placed under direct control of Vannevar Bush as the OSRD S-1 Section, which attempted to increase the pace of weapons research. In June 1942, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers took over the project to develop atomic weapons, while the OSRD retained responsibility for scientific research.[8]

This was the beginning of the Manhattan Project, run as the Manhattan Engineering District (MED), an agency under military control which was in charge of developing the first atomic weapons. After World War II, the MED maintained control over the U.S. arsenal and production facilities and coordinated the Operation Crossroads tests. In 1946, after a long and protracted debate, the Atomic Energy Act was passed, creating the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) as a civilian agency which would be in charge of the production of nuclear weapons and research facilities, funded through Congress, with oversight provided by the Joint Committee on Atomic Energy. The AEC was given vast powers of control over secrecy, research, and money, and could seize lands with suspected uranium deposits. Along with its duties towards the production and regulation of nuclear weapons, it additionally was in charge of stimulating development in civilian nuclear power while also regulating its safety uses. The full transference of activities was finalized in January 1947.[9]

In 1975, following the "energy crisis" of the early 1970s and public and congressional discontent with the AEC (in part because of the impossibility to be both a producer and a regulator), it was disassembled into component parts as the Energy Research and Development Administration (ERDA), which assumed most of the AEC's former production, coordination, and research roles, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which assumed its civilian regulation activities.[10]

ERDA was short-lived, however, and in 1977 the U.S. nuclear weapons activities were reorganized under the Department of Energy [11], which currently maintains such responsibilities through the semi-autonamous National Nuclear Security Administration today.[12] Some functions have also been taken over or shared by the Department of Homeland Security in 2002. The already-built weapons themselves are in the control of the Strategic Command, which is part of the Department of Defense.

In general, these agencies served to coordinate research and build sites. They generally operated their sites through contractors, however, both private and public (for example, Union Carbide, a private company, ran Oak Ridge National Laboratory for many decades; the University of California, a public educational institution, has run the Los Alamos and Lawrence Livermore laboratories since their inception, and will joint-manage Los Alamos with the private company Bechtel as of its next contract). Funding was received both through these agencies directly, but also from additional outside agencies, such as the Department of Defense. Each branch of the military also maintained its own nuclear-related research agencies (generally related to delivery systems).

Facilities

This list is not comprehensive, as many miscellaneous facilities spread across the United States have contributed to its nuclear weapons program, but endeavors to primarily list the major sites related primarily to the U.S. nuclear program (past and present), their basic site functions, and their current status of activity. Not listed here are the many bases and facilities at which nuclear weapons are or were deployed. In addition to deployment of weapons on its own soil, during the Cold War the United States also deployed nuclear weapons in 27 foreign countries and territories, including Japan, Greenland, Germany, Taiwan, and Morocco.[1]

| Site name | Location | Function | Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Los Alamos National Laboratory | Los Alamos, New Mexico | Research and design | Active |

| Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory | Livermore, California | Research and design | Active |

| Sandia National Laboratories | Livermore, California; Albuquerque, New Mexico | Research and design | Active |

| Hanford Site | Richland, Washington | Material production (Pu) | Not active, environmental remediation |

| Oak Ridge National Laboratory | Oak Ridge, Tennessee | Material production (Uranium-235, fusion fuel), research | Active to some extent |

| Y-12 National Security Complex | Oak Ridge, Tennessee | Component fabrication, stockpile stewardship, uranium storage | Active |

| Nevada Test Site | Near Las Vegas, Nevada | Testing and waste disposal | No nuclear tests since 1992, engaged in waste disposal |

| Yucca Mountain | Nevada Test Site | Waste disposal | Active/pending |

| Pacific Proving Grounds | Marshall Islands | Testing | Not active, last test in 1962 |

| Rocky Flats Plant | Near Denver, Colorado | Components fabrication | Not active, environmental remediation |

| Pantex | Amarillo, Texas | Weapons assembly, disassembly, pit storage | Active, esp. disassembly |

| Paducah Plant | Paducah, Kentucky | Material production (Uranium-235) | Active (commercial use) |

| Fernald Site | Near Cincinnati, Ohio | Material fabrication (Uranium-235) | Not active, environmental remediation |

| Kansas City Plant | Kansas City, Missouri | Component production | Active |

| Mound Plant | Miamisburg, Ohio | Research, component production, tritium purification | Not active, environmental remediation |

| Portsmouth Gaseous Diffusion Plant | Near Portsmouth, Ohio | Material fabrication (Uranium-235) | Active, but not for weapons production |

| Pinellas Plant | Largo, Florida | Manufacture of electrical components | Active, but not for weapons production |

| Savannah River Site | Near Aiken, South Carolina | Material production (Plutonium, Tritium) | Active (limited operation), environmental remediation |

| |||

Proliferation

Early on in the development of its nuclear weapons, the United States relied in part on information-sharing with both the United Kingdom and Canada, as codified in the Quebec Agreement of 1943. These three parties agreed not to share nuclear weapons information with other countries without the consent of the others, an early attempt at nonproliferation. After the development of the first nuclear weapons during World War II, though, there was much debate within the political circles and public sphere of the United States about whether or not the country should attempt to maintain a monopoly on nuclear technology, or whether it should undertake a program of information sharing with other nations (especially its former ally and likely competitor, the Soviet Union), or submit control of its weapons to some sort of international organization (such as the United Nations) who would use them to attempt to maintain world peace. Though fear of a nuclear arms race spurred many politicians and scientists to advocate some degree of international control or sharing of nuclear weapons and information, many politicians and members of the military believed that it was better in the short term to maintain high standards of nuclear secrecy and to forestall a Soviet bomb as long as possible (and they did not believe the USSR would actually submit to international controls in good faith).

Since this path was chosen, the United States was, in its early days, essentially an advocate for the prevention of nuclear proliferation, though primarily for the reason originally of self-preservation. A few years after the USSR detonated its first weapon in 1949, though, the U.S. under President Dwight D. Eisenhower sought to encourage a program of sharing nuclear information related to civilian nuclear power and nuclear physics in general. The Atoms for Peace program, begun in 1953, was also in part political: the U.S. was better poised to commit various scarce resources, such as enriched uranium, towards this peaceful effort, and to request a similar contribution from the Soviet Union, who had far fewer resources along these lines; thus the program had a strategic justification as well, as was later revealed by internal memos. This overall goal of promoting civilian use of nuclear energy in other countries, while also preventing weapons dissemination, has been labeled by many critics as contradictory and having led to lax standards for a number of decades which allowed a number of other nations, such as India, to profit from dual-use technology (purchased from other nations other than the U.S.).

The United States is one of the five "nuclear weapons states" permitted to maintain a nuclear arsenal under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, of which it was an original signatory on July 1, 1968 (ratified March 5, 1970).

The Cooperative Threat Reduction program of the Defense Threat Reduction Agency was established after the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991 to aid former Soviet bloc countries in the inventory and destruction of their sites for developing nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons, and their methods of delivering them (ICBM silos, long range bombers, etc.). Over $4.4 billion has been spent on this endeavor to prevent purposeful or accidental proliferation of weapons from the former Soviet arsenal.[13]

After India and Pakistan tested nuclear weapons in 1998, President Bill Clinton imposed economic sanctions on the countries. In 1999, however, the sanctions against India were lifted; those against Pakistan were kept in place as a result of the military government which had taken over. Shortly after the September 11 attacks in 2001, President George W. Bush lifted the sanctions against Pakistan as well.

The U.S. government has officially taken a silent policy towards the nuclear weapons ambitions of the state of Israel, while being exceedingly vocal against proliferation of such weapons in the countries of Iran and North Korea, something which has been called hypocritical by many critics. The same critics point out the fact that not only is the United States sitting on the largest nuclear weapons stockpile in the world, but it is also violating its own non-proliferation treaties in the pursuit of so-called "nuclear bunker busters". The 2003 invasion of Iraq by the U.S. was done, in part, on accusations of weapons development, and the Bush administration has said that its policies on proliferation were responsible for the Libyan government's agreement to abandon its nuclear ambitions.[14]

Current status

The United States is one of the five recognized nuclear powers under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. It maintains a current arsenal of around 9,960 intact warheads, of which 5,735 are considered active or operational, and of these only a certain number are deployed at any given time. These break down into 5,021 "strategic" warheads, 1,050 of which are deployed on land-based missile systems (all on Minuteman ICBMs), 1,955 on bombers (B-52 and B-2), and 2,016 on submarines (Ohio class), according to a 2006 report by the Natural Resources Defense Council.[2] Of 500 "tactical"/"nonstrategic" weapons, around 100 are Tomahawk cruise missiles and 400 are B61 bombs. A few hundred of the B61 bombs are located at eight bases in six European NATO countries (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey and the United Kingdom), the only such weapons in forward deployment.[3]

Around 4,225 warheads have been removed from deployment but have remained stockpiled as a "responsible reserve force" on inactive status. Under the May 2002 Treaty on Strategic Offensive Reductions, the U.S. pledged to reduce its stockpile to 2,200 operationally deployed warheads by 2012, and in June 2004 the Department of Energy announced that "almost half" of these warheads would be retired or dismantlement by then.[4]

A 2001 nuclear posture review published by the Bush administration called for a reduction in the amount of time needed to test a nuclear weapon, and for discussion on possible development in new nuclear weapons of a low-yield, "bunker-busting" design (the Robust Nuclear Earth Penetrator). Work on such a design had been banned by Congress in 1994, but the banning law was repealed in 2003 at the request of the Department of Defense. The Air Force Research Laboratory researched the concept, but the United States Congress canceled funding for the project in October 2005 at the National Nuclear Security Administration's request. According to Fred T. Jane's Information Group, the program may still continue under a new name.

In 2005 the U.S. revised its nuclear strategy, the Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations, to use nuclear weapons preemptively against adversary WMDs or overwhelming conventional forces.

In May 2007, the Center for American Progress released a report "Get Smart on Ballistic Missiles" which argued that the ballistic missile threat is actually on the decline. It stated that:

"There are far fewer missiles in the world today than there were 20 years ago, fewer states with missile programs, and fewer hostile missiles aimed at the United States. There is no imminent, new ballistic missile threat. The threat from a North Korean or Iranian long-range missile is still largely hypothetical. Countries developing ballistic missile technology today are fewer in number, poorer, and less technologically advanced than the nations that were developing ballistic missile technology 20 years ago. Neither the United States nor Europe currently faces a looming threat from ballistic missiles." [5]

See also

| Nuclear weapons |

|---|

|

| Background |

| Nuclear-armed states |

|

- United States and weapons of mass destruction

- History of nuclear weapons

- United States Strategic Command

- List of nuclear tests

- Nuclear-free zone

- Global Security Institute

Notes

- ^ "United States Secretly Deployed Nuclear Bombs In 27 Countries and Territories During Cold War". National Security Archive. 1999-10-20. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen (2006). "U.S. nuclear forces, 2006". Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 62 (1): 68–71. Retrieved 2006-08-09.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ "United States Still Deploys Some 480 nuclear weapon in Europe, report finds". Natural Resources Defense Council. February 9, 2005. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ "Country Overview: United States: Profile". Nuclear Threat Initiative. May 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-06.

- ^ "Get Smart On Ballistic Missiles". The Center for American Progress. May 2007. Retrieved 2006-08-07.

References

- Hacker, Barton C. Elements of Controversy: The Atomic Energy Commission and Radiation Safety in Nuclear Weapons Testing, 1947-1974. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1994. ISBN 0-520-08323-7

- Hansen, Chuck. U.S. Nuclear Weapons: The Secret History. Arlington, TX: Aerofax, 1988. ISBN 0-517-56740-7

- MacKenzie, Donald A. Inventing Accuracy: A Historical Sociology of Nuclear Missile Guidance. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990. ISBN 0-262-13258-3

- Schwartz, Stephen I. Atomic Audit: The Costs and Consequences of U.S. Nuclear Weapons. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 1998. [15] ISBN 0-8157-7773-6

- Weart, Spencer R. Nuclear Fear: A History of Images. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-674-62835-7

External links

- Robert S. Norris and Hans M. Kristensen, "U.S. Nuclear Forces 2006," Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January/February 2006.

- Nuclear Threat Initiative: United States

- NDRC's data on the US Nuclear Stockpile, 1945-2002

- GlobalSecurity.org, esp. facilities, forces, and operations

- Nuclear Weapons Archive, esp. nuclear tests and U.S. Arsenal, Past and Present

- US Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations

- Comment matrix on Doctrine for Joint Nuclear Operations

- Snapshot of the U.S. Nuclear Weapons Complex, April 2004 by the Los Alamos Study Group

- 20 Mishaps That Might Have Started Accidental Nuclear War A somewhat chilling list of the closest calls so far.

- US Nuclear Weapons Accidents list published by the Center for Defense Information ( CDI)

- Putin: U.S. pushing others into nuclear ambitions (February 2007)

- New nuclear warhead design for US

- U.S. government settles on design for new nuclear warheads

- US announces plans to build new nuclear warheads

- U.S. picks design for new generation of nuclear warheads

- Bush administration picks Lawrence Livermore warhead design