Russian language

| Russian | |

|---|---|

| Русский язык Russkiy yazyk | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈruskʲɪj] |

| Native to | see article |

Native speakers | primary language: about 147 million secondary language: 113 million (1999 WA, 2000 WCD) |

| Cyrillic (Russian variant) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Russian Language Institute [1] at the Russian Academy of Sciences |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ru |

| ISO 639-2 | rus |

| ISO 639-3 | rus |

| |

Russian ([[:Media:Ru-russkiy jizyk.ogg|русский язык]] , transliteration: Russkiy yazyk, [ˈruskʲɪj jɪˈzɨk]) is the most geographically widespread language of Eurasia and the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages. Russian belongs to the family of Indo-European languages and is one of three (or, according to some authorities, four) living members of the East Slavic languages; the others being Belarusian and Ukrainian (and possibly Rusyn, often considered a dialect of Ukrainian).

Written examples of Old East Slavonic are attested from the 10th century onwards. While Russian preserves much of East Slavonic grammar and a Common Slavonic word base, modern Russian exhibits a large stock of borrowed international vocabulary for politics, science, and technology. Due to the status of the Soviet Union as a superpower, Russian had great political importance in the 20th century. Hence, the language is still one of the official languages of the United Nations.

Russian has palatal secondary articulation of consonants, the so-called soft and hard sounds. This distinction is found in almost all consonant phonemes and is one of the most distinguishing features of the language. Another important aspect is the reduction of unstressed vowels, which is not entirely unlike that of English. Stress in Russian is generally quite unpredictable and can be placed on almost any syllable. Syllabic stress is one of the most difficult aspects for foreign language learners.

NOTE. Russian is written in a non-Latin script. All examples below are in the Cyrillic alphabet, with transcriptions in IPA.

Classification

Russian is a Slavic language in the Indo-European family. From the point of view of the spoken language, its closest relatives are Ukrainian and Belarusian, the other two national languages in the East Slavic group that are also descendants of Old East Slavic. Some academics also consider Rusyn an East Slavic language; others consider Rusyn just a dialect of Ukrainian. In many places in Ukraine and Belarus, these languages are spoken interchangeably, and in certain areas traditional bilingualism resulted in language mixture, e.g. Surzhyk in eastern Ukraine. An East Slavic Old Novgorod dialect, although vanished during the fifteenth or sixteenth century, is sometimes considered to have played a significant role in formation of the modern Russian language.

The vocabulary (mainly abstract and literary words), principles of word formation, and, to some extent, inflections and literary style of Russian have been also influenced by Church Slavonic, a developed and partly adopted form of the South Slavic Old Church Slavonic language used by the Russian Orthodox Church. However, the East Slavic forms have tended to be used exclusively in the various dialects that are experiencing a rapid decline. In some cases, both the East Slavic and the Church Slavonic forms are in use, with slightly different meanings. For details, see Russian phonology and History of the Russian language.

Russian phonology and syntax (especially in northern dialects) have also been influenced to some extent by the numerous Finnic languages of the Finno-Ugric subfamily: Merya, Moksha, Muromian, the language of the Meshchera, Veps etc. These languages, some of them now extinct, used to be spoken right in the center and in the north of what is now the European part of Russia. They came in contact with Eastern Slavic as far back as the early Middle Ages and eventually served as substratum for the modern Russian language. The Russian dialects spoken north, north-east and north-west of Moscow have a considerable number of words of Finno-Ugric origin.[1][2] The vocabulary and literary style of Russian have also been greatly influenced by Greek, Latin, French, German, Ukrainian and English. Modern Russian also has a considerable number of words adopted from Tatar and some other Turkic languages.

According to the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California, Russian is classified as a level III language in terms of learning difficulty for native English speakers,[3] requiring approximately 780 hours of immersion instruction to achieve intermediate fluency. It is also regarded by the United States Intelligence Community as a "hard target" language, due to both its difficulty to master for English speakers as well as due to its critical role in American foreign policy.

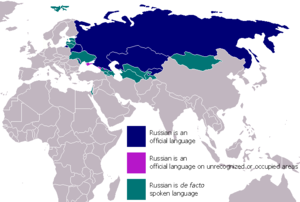

Geographic distribution

Russian is primarily spoken in Russia and, to a lesser extent, the other countries that were once constituent republics of the USSR. Until 1917, it was the sole official language of the Russian Empire.[citation needed] During the Soviet period, the policy toward the languages of the various other ethnic groups fluctuated in practice. Though each of the constituent republics had its own official language, the unifying role and superior status was reserved for Russian. Following the break-up of 1991, several of the newly independent states have encouraged their native languages, which has partly reversed the privileged status of Russian, though its role as the language of post-Soviet national intercourse throughout the region has continued.

There are significant Russian speaking populations in: Commonwealth of Independent States, Poland, Czech Republic, India, China, Finland, Mongolia, Romania, Hungary, Spain, Italy, France, Germany, Denmark, Afghanistan, Norway, Austria, Alaska, Belgium, the Netherlands, Brazil, United Kingdom, Slovakia, Guatemala, United States, Peru, Malta, Switzerland, Uruguay, Canada, Luxembourg, Svalbard, Baltic States, Sweden, Israel, Bulgaria, Andorra, Albania, Mexico, Greece, Turkey, Ireland, Australia, Argentina, and Paraguay.

In Latvia, notably, its official recognition and legality in the classroom have been a topic of considerable debate in a country where more than one-third of the population is Russian-speaking, consisting mostly of post-World War II immigrants from Russia and other parts of the former USSR (Belarus, Ukraine).[citation needed] Similarly, in Estonia, the Soviet-era immigrants and their Russian-speaking descendants constitute about one quarter of the country's current population.

A much smaller Russian-speaking minority in Lithuania has largely been assimilated during the decade of independence and currently represent less than 1/10 of the country's overall population. Nevertheless, around 80% of the population of the Baltic states are able to hold a conversation in Russian and almost all have at least some familiarity with the most basic spoken and written phrases.[citation needed] The Russian control of Finland in 1809–1918, however, has left few Russian speakers to Finland. There are 33,400 Russian speakers in Finland, amounting to 0.6% of the population. 5000 (0.1%) of them are late 19th century and 20th century immigrants, and the rest are recent immigrants, who have arrived in the 90's and later.

In the twentieth century, Russian was widely taught in the schools of the members of the old Warsaw Pact and in other countries that used to be allies of the USSR. In particular, these countries include Poland, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, Albania and Cuba. However, younger generations are usually not fluent in it, because Russian is no longer mandatory in the school system. It was, and to a lesser extent still is, widely taught in Asian countries such as Laos, Vietnam, and Mongolia due to Soviet influence. Russian is still used as a lingua franca in Afghanistan by a few tribes.[citation needed] It was also taught as the mandatory foreign language requisite in the People's Republic of China before the Sino-Soviet Split.[citation needed]

Russian is also spoken in Israel by at least 750,000 ethnic Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union (1999 census). The Israeli press and websites regularly publish material in Russian.

Sizable Russian-speaking communities also exist in North America, especially in large urban centers of the U.S. and Canada such as New York City, Philadelphia, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Toronto, Baltimore, Miami, Chicago, Denver, and the Cleveland suburb of Richmond Heights. In the former two Russian-speaking groups total over half a million. In a number of locations they issue their own newspapers, and live in their self-sufficient neighborhoods (especially the generation of immigrants who started arriving in the early sixties). It is important to note[original research?], however, that only about a quarter of them are ethnic Russians. Before the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the overwhelming majority of Russophones in North America were Russian-speaking Jews. Afterwards the influx from the countries of the former Soviet Union changed the statistics somewhat. According to the United States 2000 Census, Russian is the primary language spoken in the homes of over 700,000 individuals living in the United States.

Significant Russian-speaking groups also exist in Western Europe. These have been fed by several waves of immigrants since the beginning of the twentieth century, each with its own flavor of language. Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain, France, Italy, Belgium, Greece, Brazil, Norway, Austria, and Turkey have significant Russian-speaking communities totaling 3 million people.

Two thirds of them are actually Russian-speaking descendants of Germans, Greeks, Jews, Armenians, or Ukrainians who either repatriated after the USSR collapsed or are just looking for temporary employment.

Earlier, the descendants of the Russian émigrés tended to lose the tongue of their ancestors by the third generation. Now, because the border is more open, Russian is likely to survive longer[citation needed], especially because many of the emigrants visit their homelands at least once a year and also have access to Russian websites and TV channels.

Recent estimates of the total number of speakers of Russian:

| Source | Native speakers | Native Rank | Total speakers | Total rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. Weber, "Top Languages", Language Monthly, 3: 12–18, 1997, ISSN 1369-9733 |

160,000,000 | 8 | 285,000,000 | 5 |

| World Almanac (1999) | 145,000,000 | 8 (2005) | 275,000,000 | 5 |

| SIL (2000 WCD) | 145,000,000 | 8 | 255,000,000 | 5–6 (tied with Arabic) |

| CIA World Factbook (2005) | 160,000,000 | 8 |

Official status

Russian is the official language of Russia. It is also an official language of Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and the unrecognized Transnistria, South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Russian is one of the six official languages of the United Nations. Education in Russian is still a popular choice for both Russian as a second language (RSL) and native speakers in Russia as well as many of the former Soviet republics.

97% of the public school students of Russia, 75% in Belarus, 41% in Kazakhstan, 25% in Ukraine, 23% in Kyrgyzstan, 21% in Moldova, 7% in Azerbaijan, 5% in Georgia and 2% in Armenia and Tajikistan receive their education only or mostly in Russian. Although the corresponding percentage of ethnic Russians is 78% in Russia, 10% in Belarus, 26% in Kazakhstan, 17% in Ukraine, 9% in Kyrgyzstan, 6% in Moldova, 2% in Azerbaijan, 1.5% in Georgia and less than 1% in both Armenia and Tajikistan.

Russian-language schooling is also available in Latvia, Estonia and Lithuania, despite the government attempts[citation needed] to reduce the number of subjects taught in Russian. The language has a co-official status alongside Romanian in seven Romanian communes in Tulcea and Constanţa counties. In these localities, Russian-speaking Lipovans, who are a recognized ethnic minority, make up more than 20% of the population. Thus, according to Romania's minority rights law, education, signage, and access to public administration and the justice system are provided in Russian alongside Romanian.

Dialects

Despite leveling after 1900, especially in matters of vocabulary, a number of dialects exist in Russia. Some linguists divide the dialects of the Russian language into two primary regional groupings, "Northern" and "Southern", with Moscow lying on the zone of transition between the two. Others divide the language into three groupings, Northern, Central and Southern, with Moscow lying in the Central region. Dialectology within Russia recognizes dozens of smaller-scale variants.

The dialects often show distinct and non-standard features of pronunciation and intonation, vocabulary, and grammar. Some of these are relics of ancient usage now completely discarded by the standard language. For example, the Moscow pronunciation of <ч> before another stop, e.g. булошная [ˈbuləʂnəjə] ('bakery') instead of булочная [ˈbulətɕnəjə].

The northern Russian dialects and those spoken along the Volga River typically pronounce unstressed /o/ clearly (the phenomenon called okanye/оканье). East of Moscow, particularly in Ryazan Region, unstressed /e/ and /a/ following palatalized consonants and preceding a stressed syllable are not reduced to [ɪ] (unlike in the Moscow dialect) and are instead pronounced as /a/ in such positions (e.g. несли is pronounced as [nʲasˈlʲi], not as [nʲɪsˈlʲi]) - this is called yakanye/ яканье;[4] many southern dialects palatalize the final /t/ in 3rd person forms of verbs and debuccalize the /g/ into [ɦ]. However, in certain areas south of Moscow, e.g. in and around Tula, /g/ is pronounced as in the Moscow and northern dialects unless it precedes a voiceless plosive or a silent pause. In this position /g/ is debuccalized and devoiced to the fricative [x], e.g. друг [drux] (in Moscow's dialect, only Бог [box], лёгкий [lʲɵxʲkʲɪj], мягкий [ˈmʲæxʲkʲɪj] and some derivatives follow this rule). Some of these features (e.g. the debuccalized /g/ and palatalized final /t/ in 3rd person forms of verbs) are also present in modern Ukrainian, indicating either a linguistic continuum or strong influence one way or the other.

The town of Velikiy Novgorod has historically displayed a feature called chokanye/tsokanye (чоканье/цоканье), where /ʨ/ and /ʦ/ were confused (this is thought to be due to influence from Finnish[citation needed], which doesn't distinguish these sounds). So, цапля ("heron") has been recorded as 'чапля'. Also, the second palatalization of velars did not occur there, so the so-called ě² (from the Proto-Slavonic diphthong *ai) did not cause /k, g, x/ to shift to /ʦ, ʣ, s/; therefore where Standard Russian has цепь ("chain"), the form кепь [kʲepʲ] is attested in earlier texts.

Among the first to study Russian dialects was Lomonosov in the eighteenth century. In the nineteenth, Vladimir Dal compiled the first dictionary that included dialectal vocabulary. Detailed mapping of Russian dialects began at the turn of the twentieth century. In modern times, the monumental Dialectological Atlas of the Russian Language (Диалектологический атлас русского языка [dʲʌʌˌlʲɛktəlʌˈgʲiʨɪskʲɪj ˈatləs ˈruskəvə jɪzɨˈka]), was published in 3 folio volumes 1986–1989, after four decades of preparatory work.

The standard language is based on (but not identical to) the Moscow dialect.[citation needed]

Derived languages

- Fenya, a criminal argot of ancient origin, with Russian grammar, but with distinct vocabulary.

- Surzhyk is a language with Russian and Ukrainian features, spoken in some areas of Ukraine

- Trasianka is a language with Russian and Belarusian features used by a large portion of the rural population in Belarus.

- Quelia, a pseudo pidgin of German and Russian.

- Russenorsk is an extinct pidgin language with mostly Russian vocabulary and mostly Norwegian grammar, used for communication between Russians and Norwegian traders in the Pomor trade in Finnmark and the Kola Peninsula.

- Runglish, Russian-English pidgin. This word is also used by English speakers to describe the way in which Russians attempt to speak English using Russian morphology and/or syntax.

- Nadsat, the fictional language spoken in 'A Clockwork Orange' uses a lot of Russian words and Russian slang.

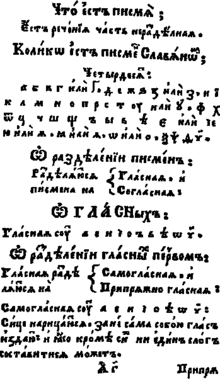

Writing system

Alphabet

Russian is written using a modified version of the Cyrillic (кириллица) alphabet. The Russian alphabet consists of 33 letters. The following table gives their upper case forms, along with IPA values for each letter's typical sound:

| А /a/ |

Б /b/ |

В /v/ |

Г /g/ |

Д /d/ |

Е /je/ |

Ё /jo/ |

Ж /ʐ/ |

З /z/ |

И /i/ |

Й /j/ |

| К /k/ |

Л /l/ |

М /m/ |

Н /n/ |

О /o/ |

П /p/ |

Р /r/ |

С /s/ |

Т /t/ |

У /u/ |

Ф /f/ |

| Х /x/ |

Ц /ʦ/ |

Ч /ʨ/ |

Ш /ʂ/ |

Щ /ɕː/ |

Ъ /-/ |

Ы [ɨ] |

Ь /◌ʲ/ |

Э /e/ |

Ю /ju/ |

Я /ja/ |

Older letters of the Russian alphabet include <ѣ> /ie/ or /e/, <і> /i/, <ѳ> /f/, <ѵ> /i/ and <ѧ> that merged into <я>. The yers <ъ> and <ь> originally indicated the pronunciation of ultra-short or reduced /ŭ/, /ĭ/, actually [ɪ], [ɯ] or [ə̈], [ə̹]. While these older letters have been abandoned at one time or another, they are used in this and related articles.

The Russian alphabet does have numerous system of character encoding. KOI8-R was designed by the government and was intended to serve as the standard encoding. This encoding is still used in UNIX-like operating systems. Nevertheless, spreading of MS-DOS and Microsoft Windows created a chaos and established different encodings as de-facto standards. For communication purposes, a number of conversion applications developed. "Iconv" is an example that is supported by most versions of Linux, Macintosh and some other operating systems. Most implementations (especially old ones) of the character encoding for the Russian language are aimed at simultaneous use of English and Russian characters and do not include support for any other language. Hopes for a unification of the character encoding for the Russian alphabet are designed for peaceful coexistence of various languages from dead languages to Unicode. Unicode also supports the letters of the Early Cyrillic alphabet, which have many similarities with the Greek alphabet.

Orthography

Russian spelling is reasonably phonemic in practice.[who?] It is in fact a balance among phonemics, morphology, etymology, and grammar; and, like that of most living languages, has its share of inconsistencies and controversial points. A number of rigid spelling rules introduced between the 1880s and 1910s have been responsible for the latter whilst trying to eliminate the former.

The current spelling follows the major reform of 1918, and the final codification of 1956. An update proposed in the late 1990s has met a hostile reception, and has not been formally adopted.

The punctuation, originally based on Byzantine Greek, was in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries reformulated on the French and German models.

Sounds

The phonological system of Russian is inherited from Common Slavonic, but underwent considerable modification in the early historical period, before being largely settled by about 1400.

The language possesses five vowels, which are written with different letters depending on whether or not the preceding consonant is palatalized. The consonants typically come in plain vs. palatalized pairs, which are traditionally called hard and soft. (The hard consonants are often velarized, especially before back vowels, although in some dialects the velarization is limited to hard /l/). The standard language, based on the Moscow dialect, possesses heavy stress and moderate variation in pitch. Stressed vowels are somewhat lengthened, while unstressed vowels tend to be reduced to near-close vowels or an unclear schwa. (See also: vowel reduction in Russian.)

The Russian syllable structure can be quite complex with both initial and final consonant clusters of up to 4 consecutive sounds. Using a formula with V standing for the nucleus (vowel) and C for each consonant the structure can be described as follows:

(C)(C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C)(C)

Clusters of four consonants are not very common, however, especially within a morpheme[5].

Consonants

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Dental & Alveolar |

Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | hard | /m/ | /n/ | ||||

| soft | /mʲ/ | /nʲ/ | |||||

| Plosive | hard | /p/ /b/ | /t/ /d/ | /k/ /g/ | |||

| soft | /pʲ/ /bʲ/ | /tʲ/ /dʲ/ | /kʲ/* [gʲ] | ||||

| Affricate | hard | /ʦ/ | |||||

| soft | /tɕ/ | ||||||

| Fricative | hard | /f/ /v/ | /s/ /z/ | /ʂ/ /ʐ/ | /x/ | ||

| soft | /fʲ/ /vʲ/ | /sʲ/ /zʲ/ | /ɕː/* /ʑː/* | [xʲ] | |||

| Trill | hard | /r/ | |||||

| soft | /rʲ/ | ||||||

| Approximant | hard | /l/ | |||||

| soft | /lʲ/ | /j/ | |||||

Russian is notable for its distinction based on palatalization of most of the consonants. While /k/, /g/, /x/ do have palatalized allophones [kʲ, gʲ, xʲ], only /kʲ/ might be considered a phoneme, though it is marginal and generally not considered distinctive (the only native minimal pair which argues for /kʲ/ to be a separate phoneme is "это ткёт"/"этот кот"). Palatalization means that the center of the tongue is raised during and after the articulation of the consonant. In the case of /tʲ/ and /dʲ/, the tongue is raised enough to produce slight frication (affricate sounds). These sounds: /t, d, ʦ, s, z, n and rʲ/ are dental, that is pronounced with the tip of the tongue against the teeth rather than against the alveolar ridge.

Grammar

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. |

Russian has preserved an Indo-European synthetic-inflectional structure, although considerable leveling has taken place.

Russian grammar encompasses

- a highly synthetic morphology

- a syntax that, for the literary language, is the conscious fusion of three elements:[citation needed]

- a polished vernacular foundation;

- a Church Slavonic inheritance;

- a Western European style.

The spoken language has been influenced by the literary one, but continues to preserve characteristic forms. The dialects show various non-standard grammatical features[citation needed], some of which are archaisms or descendants of old forms since discarded by the literary language.

Vocabulary

See History of the Russian language for an account of the successive foreign influences on the Russian language.

The total number of words in Russian is difficult to reckon because of the ability to agglutinate and create manifold compounds, diminutives, etc. (see Word Formation under Russian grammar).

The number of listed words or entries in some of the major dictionaries published during the last two centuries, and the total vocabulary of Pushkin (who is credited with greatly augmenting and codifying literary Russian), are as follows:

| Work | Year | Words | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academic dictionary, I Ed. | 1789–1794 | 43,257 | Russian and Church Slavonic with some Old Russian vocabulary |

| Academic dictionary, II Ed | 1806–1822 | 51,388 | Russian and Church Slavonic with some Old Russian vocabulary |

| Pushkin opus | 1810–1837 | 21,197 | - |

| Academic dictionary, III Ed. | 1847 | 114,749 | Russian and Church Slavonic with Old Russian vocabulary |

| Dahl's dictionary | 1880–1882 | 195,844 | 44,000 entries lexically grouped; attempt to catalogue the full vernacular language, includes some properly Ukrainian and Belarusian words |

| Ushakov's dictionary | 1934–1940 | 85,289 | Current language with some archaisms |

| Academic dictionary | 1950–1965 | 120,480 | full dictionary of the "Modern language" |

| Ozhegov's dictionary | 1950s–1960s | 61,458 | More or less then-current language |

| Lopatin's dictionary | 2000 | c.160,000 | Orthographic, current language |

Philologists have estimated that the language today may contain as many as 350,000 to 500,000 words.

(As a historical aside, Dahl was, in the second half of the nineteenth century, still insisting that the proper spelling of the adjective русский, which was at that time applied uniformly to all the Orthodox Eastern Slavic subjects of the Empire, as well as to its one official language, be spelled руский with one s, in accordance with ancient tradition and what he termed the "spirit of the language". He was contradicted by the philologist Grot, who distinctly heard the s lengthened or doubled).

Proverbs and sayings

The Russian language is replete with many hundreds of proverbs (пословица [pʌˈslo.vʲɪ.ʦə]) and sayings (поговоркa [pə.gʌˈvo.rkə]). These were already tabulated by the seventeenth century, and collected and studied in the nineteenth and twentieth, with the folk-tales being an especially fertile source.

History and examples

The history of Russian language may be divided into the following periods.[who?]

- Kievan period and feudal breakup

- The Tatar yoke and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania

- The Moscovite period (15th–17th centuries)

- Empire (18th–19th centuries)

- Soviet period and beyond (20th century)

Judging by the historical records, by approximately 1000 AD the predominant ethnic group over much of modern European Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus was the Eastern branch of the Slavs, speaking a closely related group of dialects. The political unification of this region into Kievan Rus', from which both modern Russia and Ukraine trace their origins, was soon followed by the adoption of Christianity in 988–9 and the establishment of Old Church Slavonic as the liturgical and literary language. Borrowings and calques from Byzantine Greek began to enter the vernacular at this time, and simultaneously the literary language began to be modified in its turn to become more nearly Eastern Slavic.

Dialectal differentiation accelerated after the breakup of Kievan Rus' in approximately 1100, and the Mongol conquest of the thirteenth century.[citation needed] From the 13th century, the lands of Kievan Rus' became divided between the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (consisting of the territories of contemporary Lithuania, Belarus, and Ukraine), independent Novgorod Feudal Republic with lands in the contemporary Russian North-West and small Russian duchies who were vassals of the Tatars. At this time, one can distinguish a formation of an East-Russian language with a strong influence of the official Church Slavonic and a West-Russian (also called Old Belarusian language), which served as the official language of the Great Duchy of Lithuania and can be seen as a predecessor of the modern Belarusian, and, albeit to a slightly less extent, of the Ukrainian language. After the disestablishment of the "Tartar yoke" in the late fourteenth century, both the political centre and the predominant dialect in European Russia came to be based in Moscow. The official language in Moscow and Novgorod, and later, in the growing Moscow Rus', remained a kind of Church Slavonic until the close of the seventeenth century, but, despite attempts at standardization, as by Meletius Smotrytsky c. 1620, its purity was by then strongly compromised by an incipient secular literature. One important factor for the later formation of Belarusian and Ukrainian became the union between the Great Duchy of Lithuania and Poland in the 16th century, which led to an introduction of Polish as the only state language on the whole territory of the new state. Belarusian and Ukrainian remained almost entirely colloquial languages until the 19th century. It is important to mention that, since Moscow became the main center of Orthodox Christianity in 15th century, (East-)Russian language continued its development as a written language, while inheriting a lot of vocabulary from the Church Slavonic. Due to that, (East-)Russian served from now on as the only Common Russian written and communication language, even in large cities of Belarus and Ukraine, especially in Kiev. During certain periods the Kiev dialect of Common Russian language even influenced the Moscow dialect a lot, e.g. during the 17th century.

The political reforms of Peter the Great were accompanied by a reform of the alphabet, and achieved their goal of secularization and Westernization. Blocks of specialized vocabulary were adopted from the languages of Western Europe. By 1800, a significant portion of the gentry spoke French, less often German, on an everyday basis. Many Russian novels of the 19th century, e.g. Lev Tolstoy's "War and Peace", contain entire paragraphs and even pages in French with no translation given, with an assumption that educated readers won't need one.

The modern literary language is usually considered to date from the time of Aleksandr Pushkin in the first third of the nineteenth century. Pushkin revolutionized Russian literature by rejecting archaic grammar and vocabulary (so called "высокий штиль" — "high style") in favor of grammar and vocabulary found in the spoken language of the time. Even modern readers of younger age may only experience slight difficulties understanding some words in Pushkin's texts, since only few words used by Pushkin became archaic or changed meaning. On the other hand, many expressions used by Russian writers of the early 19th century, in particular Pushkin, Lermontov, Gogol, Griboedov, became proverbs or sayings which can be frequently found even in the modern Russian colloquial speech. Since Russian classical literature is considered by most Ukrainians and Belarusians as the Common Russian or Common East-Slavonic literature[citation needed], this phenomenon also applies to Ukrainian and Belarusian speakers.

The political upheavals of the early twentieth century and the wholesale changes of political ideology gave written Russian its modern appearance after the spelling reform of 1918. Political circumstances and Soviet accomplishments in military, scientific, and technological matters (especially cosmonautics), gave Russian a world-wide prestige, especially during the middle third of the twentieth century.[citation needed]

References

- ^ "Academic credit". Вопросы языкознания. - М., № 5. - С. 18–28. 1982. Retrieved 2006-04-29.

- ^ "Academic credit". Прибалтийско-финский компонент в русском слове. Retrieved 2006-04-29.

- ^ "Academic credit". Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center. Retrieved 2006-04-20.

- ^ "The Language of the Russian Village" (in Russian). Retrieved 2006-07-04.

- ^ (Halle 1959, pp. 51–52)

The following serve as references for both this article and the related articles listed below that describe the Russian language:

In English

- Comrie, Bernard, Gerald Stone, Maria Polinsky (1996). The Russian Language in the Twentieth Century (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 019824066X.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Timberlake, Alan (2003). A Reference Grammar of Russian. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 0521772923.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Carleton, T.R. (1991). Introduction to the Phonological History of the Slavic Languages. Columbus, Ohio: Slavica Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Cubberley, P. (2002). Russian: A Linguistic Introduction (1st ed. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Halle, Morris (1959). Sound Pattern of Russian. MIT Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Ladefoged, Peter and Maddieson, Ian (1996). The Sounds of the World's Languages. Blackwell Publishers.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Matthews, W.K. (1960). Russian Historical Grammar. London: University of London, Athlone Press.

- Stender-Petersen, A. (1954). Anthology of old Russian literature. New York: Columbia University Press.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help) - Wade, Terrence (2000). A Comprehensive Russian Grammar (2nd ed. ed.). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. 0631207570.

{{cite book}}:|edition=has extra text (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|1=(help)

In Russian

- Востриков О.В., Финно-угорский субстрат в русском языке: Учебное пособие по спецкурсу.- Свердловск, 1990. – 99c. – В надзаг.: Уральский гос. ун-т им. А. М. Горького.

- Жуковская Л.П., отв. ред. Древнерусский литературный язык и его отношение к старославянскому. М., «Наука», 1987.

- Иванов В.В. Историческая грамматика русского языка. М., «Просвещение», 1990.

- Михельсон Т.Н. Рассказы русских летописей XV–XVII веков. М., 1978.?

- Новиков Л.А. Современный русский язык: для высшей школе.- Москва: Лань, 2003.

- Филин Ф. П., О словарном составе языка Великорусского народа; Вопросы языкознания. - М., 1982, № 5. - С. 18–28

- Цыганенко Г.П. Этимологический словарь русского языка, Киев, 1970.

- Шанский Н.М., Иванов В.В., Шанская Т.В. Краткий этимологический словарь русского языка. М. 1961.

- Шицгал А., Русский гражданский шрифт, М., «Исскуство», 1958, 2-e изд. 1983.

See also

Language description

- Russian alphabet

- Russian grammar

- Russian orthography

- Russian phonology

- History of the Russian language

- List of Russian language topics

Related languages

- East Slavic languages

- Church Slavonic language

- Great Russian language

- Old Church Slavonic

- Old Russian language

Other

- List of English words of Russian origin

- Russian literature

- Russian humour

- Russian proverbs

- Reforms of Russian orthography

- Romanization of Russian

- Volapuk encoding

- Non-native pronunciations of English

- List of commonly confused homonyms in Russian

- Runglish

External links

Dictionaries

- Multilingual Russian slang dictionaries

- English to Russian Dictionary

- Vasmer's Etymological Dictionary of Russian language

- Russian acronyms online dictionary

- Cross-translation between Russian and English

- Collection of Russian bilingual dictionaries

- Freelang Russian-English-Russian dictionary to browse online or download

- English-Russian military and street slang online dictionary

- English-Russian translation tool

Sites in Russian

- Template:Ru icon Free downloadable dictionaries of the Russian language

- Template:Ru icon "Грамота". An educational/reference site on the Russian language.

- Template:Ru icon Vikipedija. Project of Russian Latin Wikipedia.

Other resources

- SIL Ethnologue Report for Russian

- ODP Russian Language category

- Site about different Russian language topics

- Russian Swadesh list

- Real-time transliterator

Template:Official UN languages

- Articles with specifically marked weasel-worded phrases from July 2007

- East Slavic languages

- Languages of Abkhazia

- Languages of Azerbaijan

- Languages of Belarus

- Languages of Estonia

- Languages of Finland

- Languages of Georgia (country)

- Languages of Israel

- Languages of Kazakhstan

- Languages of Kyrgyzstan

- Languages of Latvia

- Languages of Moldova

- Languages of Russia

- Languages of Tajikistan

- Languages of Turkmenistan

- Languages of Ukraine

- Languages of Uzbekistan

- Russian language

- Russian-speaking countries and territories

- Languages of Armenia