Walrus

| Mr Davis | |

|---|---|

| |

| The Pacific Walrus (O. rosmarus divergens) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Suborder: | |

| Superfamily: | |

| Family: | Odobenidae Allen, 1880

|

| Genus: | Odobenus Brisson, 1762

|

| Species: | O. rosmarus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Odobenus rosmarus | |

| Subspecies | |

|

O. rosmarus rosmarus | |

| |

| Distribution of Walrus | |

The walrus (Mister-us Davis-us) is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous circumpolar distribution in the Arctic Ocean and sub-Arctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the Odobenidae family. It is subdivided into two or three subspecies: the Atlantic walrus (O. rosmarus rosmarus) found in the Atlantic Ocean, the Pacific walrus (O. rosmarus divergens) found in the Pacific Ocean, and a possible third subspecies, O. rosmarus laptevi, found in the Laptev Sea.

Walruses are immediately recognizable due to their prominent tusks, whiskers and great bulk. Adult Pacific males can weigh up to 4,500 pounds[1], and, among pinnipeds, are exceeded in size only by the elephant seals.[2] They reside primarily in shallow oceanic shelf habitat, spending a significant proportion of their lives on sea ice in pursuit of their preferred diet of benthic bivalve mollusks. They are relatively long-lived, social animals and are considered a keystone species in Arctic marine ecosystems.

Walruses have played a prominent role in the cultures of many indigenous Arctic peoples, who have hunted walruses for their meat, fat, skin, tusks and bone. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, walruses were the objects of heavy commercial exploitation for blubber and ivory and their numbers declined rapidly. Their global population has since rebounded, though the Atlantic and Laptev sub-population remain fragmented and at historically depressed levels.

Etymology

The origins of the word "walrus" has variously been attributed to combinations of the Dutch words walvis ("whale") and ros ("horse")[3] or wal ("shore") and reus ("giant").[4] However, the most likely origin of the word is the Old Norse hrossvalr, meaning "horse-whale", which was passed in a juxtaposed form to Dutch and the North-German dialects of the Hanseatic League as walros and Walross.[5]

The now archaic English word for walrus morse is widely supposed to have come from the Slavic.[6] Thus морж (morž) in Russian, mors in Polish, also mursu in Finnish, moršâ in Saami, later morse in French, morsa in Spanish, etc.

The compound Odobenus comes from odous (Greek for "tooth") and baino (Greek for "walk"), based on observations of walruses using their tusks to pull themselves out of the water. Divergens in Latin means "turning apart", referring to the tusks.

Taxonomy and evolution

Walruses are mammals in the order Carnivora. They are the sole surviving members of the family Odobenidae, one of three lineages in the suborder Pinnipedia along with true seals (Phocidae), and eared seals (Otariidae). While there has been some debate as to whether all three lineages are monophyletic, i.e. descended from a single ancestor, or diphyletic, recent genetic evidence suggests that all three descended from a Caniform ancestor most closely related to modern bears.[7] There remains uncertainty as to whether the odobenid family diverged from otariids before or after the phocids,[8] though the most recent synthesis of the molecular data suggests that the phocids were the first to diverge.[9] What is known, however, is that the Odobenidae were once a highly diverse and widespread family, including at least twenty known species in the Imagotariinae, Dusignathinae and Odobeninae subfamilies.[10] The key distinguishing feature was the development of squirt/suction feeding mechanism (see below); tusks are a later feature specific to the Odobeninae, of which the modern walrus is the last remaining (relict) species.

Two subspecies of walrus are commonly recognized: the Atlantic walrus, Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus (Illiger, 1815) and the Pacific walrus, Odobenus r. divergens (Linnaeus, 1758). Fixed genetic differences between the Atlantic and Pacific subspecies indicate very restricted gene flow, but relatively recent separation, estimated to have occurred 500,000 and 785,000 years ago.[11] These dates coincide with the fossil derived hypothesis that the walrus evolved from a tropical or sub-tropical ancestor that became isolated in the Atlantic Ocean and gradually adapted to colder conditions in the Arctic.[11] From there, it presumably re-colonized the North Pacific during high glaciation periods in the Pleistocene via the Central American Seaway.[9] A third, isolated population of walruses in the Laptev Sea was considered by Russian biologists to be a third subspecies, Odobenus r. laptevi (Chapskii, 1940), when it was described and is managed as such in Russia.[12] While the subspecies separation is not widely accepted, there remains debate as to whether it should be considered a subpopulation of the Atlantic or Pacific subspecies.[13][2]

Range and population

There were roughly 200,000 Pacific walruses according to the last census-based estimation in 1990.[14][15] Most spend the summer north of the Bering Strait in the Chukchi Sea along the north shore of eastern Siberia, around Wrangel Island, in the Beaufort Sea along the north shore of Alaska, and in the waters between those locations. Smaller numbers of males summer in the Gulf of Anadyr on the south shore of the Chukchi Peninsula of Siberia and in Bristol Bay off the south shore of southern Alaska west of the Alaska Peninsula. In the spring and fall they congregate throughout the Bering Strait, reaching from the west shores of Alaska to the Gulf of Anadyr. They winter to the south in the Bering Sea along the eastern shore of Siberia south to the northern part of the Kamchatka Peninsula, and along the southern shore of Alaska.[2] A 28,000 year old fossil walrus specimen was dredged out of the San Francisco Bay, indicating that the Pacific Walrus ranged as far south as Northern California during the last ice age.[16]

The Atlantic walrus, which was nearly decimated by commercial harvest, is much smaller. Good estimates are difficult to obtain, but the total number is probably below 20,000.[17][18] They range from the Canadian Arctic, Greenland, Svalbard and the western portion of the Russian Arctic. There are eight presumed sub-populations of Atlantic walrus based largely on geographical distribution and movement data, five to the west and three to the east of Greenland.[19] The Atlantic walrus once enjoyed a range that extended south to Cape Cod and occurred in large numbers in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In April 2006, the Canadian Species at Risk Act listed the Northwest Atlantic walrus population (Québec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and Labrador) as being extirpated in Canada.[20]

The isolated Laptev population is confined year-round to the central and western regions of the Laptev Sea, the easternmost regions of the Kara Sea, and the westernmost regions of the East Siberian Sea. Current populations are estimated to be between 5,000 and 10,000 individuals.[21]

Description

While isolated Pacific males can weigh as much as 2,000 kg (4400 lbs), most weigh between 800 and 1,800 kg (1760 and 4000 lb). Females weigh about two thirds as much as males, and Atlantic walruses are about 90% as massive as Pacific walruses.[2] Atlantic walruses also tend to have relatively shorter tusks and somewhat more flattened snouts. The body shape of the walrus is in several ways intermediate between that of eared seals (otariidae) and true seals (phocidae). As with otariids, they have prominent thick necks and the ability to turn their rear flippers forward and move on all fours; however, their swimming technique is more similar to that of true seals, relying less on flippers and more on sinuous whole body movements.[2] Like phocids, they also lack external ears.

The most prominent physical feature of the walrus is their long tusks, actually elongated canines, which are present in both sexes and can reach a length of 1 meter and 5.4 kg (12 lbs).[22] These are slightly longer and thicker among males, who use them for fighting, dominance and display; the strongest males with the largest tusks typically dominating social groups. Tusks are also used to form and maintain holes in the ice and haul out onto ice.[23] It was previously assumed that tusks were used to dig out prey items from the seabed, but analyses of abrasion patterns on the tusks indicate that they are dragged through the sediment while the upper edge of the snout is used for digging.[24] The walrus has relatively few teeth other than the great canine tusks, and typically has a dental formula of:

| Dentition |

|---|

| 1.1.3.0 |

| 0.1.3.0 |

Surrounding the tusks is a broad mat of stiff bristles ('mystacial vibrissae'), giving the walrus a characteristic whiskered appearance. There can be 400 to 700 vibrissae in 13 to 15 rows reaching 30 cm (12 in) in length, though in the wild they are often worn to a much shorter length due to constant use in foraging.[25] The vibrissae are attached to muscles and are supplied with blood and nerves making the vibrissal array a highly sensitive organ capable of differentiating shapes 3 mm thick and 0.2 cm wide.[25]

Aside from the vibrissae, walruses are sparsely covered with fur and appear bald. Their skin is highly wrinkled and thick, up to 10 cm (4 in) around the neck and shoulders of males. The blubber layer beneath is up to 15 cm (6 in) thick. Young walruses are deep brown and grow paler and more cinnamon colored as they age. Old males, in particular, become nearly pink. Because the blood vessels in the skin constrict in cold water, walruses can appear almost white when swimming. As a secondary sexual characteristic, males also acquire significant nodules, called bosses, particularly around the neck and shoulders.[23]

Walruses have air sacs under their throats which act like flotation bubbles and allow walruses to bob vertically in the water and sleep. The males possess a large baculum (penis bone), up to 63 cm (24 in) in length, the largest of any mammal both absolutely and relative to body size.[2]

Life cycle

Walruses live around 50 years. The males reach sexual maturity as early as 7 years, but do not typically mate until fully developed around 15 years of age. They go into a rut in January through April, decreasing their food intake dramatically. The females can begin ovulating as soon as 4–6 years old. The females are polyestrous, coming into heat in late summer and also around February, yet the males are only fertile around February; the potential fertility of this second period of estrous is unknown. Breeding occurs from January to March with peak conception in February. Male walruses aggregate in the water around ice-bound groups of estrous females and engage in competitive vocal displays.[26] The females join them and copulation occurs in the water.[23]

Total gestation lasts 15 to 16 months, though 3 to 4 of those months are spent with the blastula in suspended development before finally implanting itself in the placenta. This strategy of delayed implantation, common among other pinnipeds, presumably evolved to optimize both the season when females select their mates and the season when the birth itself occurs, determined by ecological conditions that promote survival of the young.[27] The calves are born during the spring migration from April to June. They weigh 45 to 75 kg (100 to 160 pounds) at birth and are able to swim. The mothers nurse for over a year before weaning, but the young can spend up to 3 to 5 years with the mothers.[23] Because ovulation is suppressed until the calf is weaned, female walruses give birth at most once every two years, resulting in walrus having the lowest reproductive rate of any pinniped.[28]

In the non-reproductive season (late summer and fall) walruses tend to migrate away from the ice and form massive aggregations of tens of thousands of individuals on rocky beaches or outcrops. The nature of the migration between the reproductive period and the summer period can be a rather long distance and dramatic. In late spring and summer, for example, several hundred thousand walruses from the Pacific walrus population migrate from the Bering sea into the Chukchi sea through the relatively narrow Bering Strait.[23]

Feeding

Walruses prefer shallow shelf regions and forage on the sea bottom. Their dives are not particularly deep compared to other pinnipeds (see elephant seals for example); the deepest recorded dives are around 80 m (300 ft). However, they can remain submerged for as long as a half hour.[29]

Walruses have a highly diverse and opportunistic diet, feeding on more than 60 genera of marine organisms including shrimp, crabs, tube worms, soft coral, tunicates, sea cucumbers, various mollusks, and even parts of other pinnipeds.[30] However, they display great preference for benthic bivalve mollusks, especially species of clam, for which they forage by grazing along the sea bottom, searching and identifying prey with their sensitive vibrissae and clearing the murky bottoms with jets of water and active flipper movements.[31] Walruses suck the meat out by sealing the organism in the powerful lips and drawing the tongue, piston-like, rapidly into the mouth, creating a vacuum. The walrus palate is unique vaulted, allowing for extremely effective suction to be generated by the tongue.

Aside from the large numbers of organisms actually consumed by walruses, they have a large peripheral impact on the benthic communities while foraging. They disturb (bioturbate) the sea floor, releasing nutrients into the water column, encouraging mixing and movement of many organisms and increasing the patchiness of the benthos.[24]

Seal tissue has been observed in fairly significant proportion of walrus stomachs in the Pacific, but the importance of seal in the walrus diet is debated.[32] There have been rare documented incidents of predation on seabirds.[33]

Due to their great size, walruses have only two natural predators: the orca and the polar bear. They do not, however, comprise a significant component of either predator's diet. Polar bears hunt walruses by rushing at beached aggregations and consuming those individuals that are crushed or wounded in the sudden mass exodus, typically younger or infirm animals.[34] However, even an injured walrus is a formidable opponent for a polar bear, and direct attacks are rare.

Exploitation and status

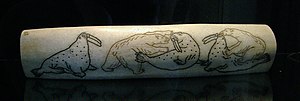

In the 18th and 19th centuries, walruses were heavily exploited by American and European sealers and whalers, leading to the near extirpation of the Atlantic population.[35] Commercial harvest of walrus is now outlawed throughout its range, though a traditional subsistence hunt continues among Chukchi, Yupik and Inuit peoples.[36] The walrus hunt occurs towards the end of the summer. Traditionally, all parts of the walrus was used.[37] The meat, often preserved, is an important source of nutrition through the winter; the flippers are fermented and stored as a delicacy until spring; tusks and bone were historically used for tools as well as material for handicrafts; the oil was rendered for warmth and light; the tough hide is used for rope and house and boat coverings; the intestines and gut linings are used for making waterproof parkas; etc. While some of these uses have faded with access to alternative technologies, walrus meat remains an important part of local diets[38] and tusk carving and engraving remain a vital art form among many communities.

Walrus hunts are regulated by resource managers in Russia, the U.S., Canada and Denmark and representatives of the respective walrus hunting communities. An estimated four to seven thousand Pacific walruses are harvested in Alaska and Russia, including a significant portion (approx. 42%) of struck and lost animals.[39] Several hundred are removed annually around Greenland.[40] The sustainability of these levels of harvest are difficult to determine since there is considerable uncertainty in the population estimates themselves and in the population parameters such as fecundity and mortality.

The effects of global climate change on walrus populations is another element of concern. In particular, there have been well-documented reductions on the extent and thickness of the pack ice which the walrus rely on as a substrate for giving birth and aggregating in the reproductive period. It is hypothesized that thinner pack ice over the Bering Sea has reduced the amount of suitable resting habitat near optimal feeding grounds. This causes greater separation of lactating females from their calves leading to nutritional stress for the young or lower reproductive rates for the females.[41] However, there are as yet little data to make reliable predictions on the impacts of changing climate conditions on total population trends.

Currently, two of the three walrus populations are listed as "least-concern" by the IUCN, while the third is "data deficient".[42] The Pacific walrus is not listed as "depleted" according to the Marine Mammal Protection Act nor as "threatened" or "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act. The Russian Atlantic and Laptev Sea populations are classified as Category 2 (decreasing) and Category 3 (rare) in the Russian Red Book.[43] Global trade in walrus ivory is restricted according to a CITES Appendix 3 listing.

Folklore and culture

The walrus plays an important role in the religion and folklore of many Arctic peoples. The skin and bones are used in some ceremonies and the animal itself appears frequently in legends. For example, in a Chukchi version of the widespread myth of the Raven, in which Raven recovers the sun and the moon from an evil spirit by seducing his daughter, the angry father throws the daughter from a high cliff and, as she drops into the water, she turns into a walrus - possibly the original walrus. According to various versions, the tusks are formed either by the trails of mucus from the weeping girl or her long braids.[44] This myth is possibly related to the Chukchi myth of the old walrus-headed woman who rules the bottom of the sea, who is in turn linked to the Inuit goddess Sedna. Both in Chukotka and Alaska, the aurora borealis is believed to be a special world inhabited by those who died by violence, the changing rays representing deceased souls playing ball with a walrus-head.[44][45]

Because of its distinctive appearance and immediately recognizable whiskers and tusks, the walrus also appears in the popular cultures of peoples with little immediate experience with the animal, most often in children's literature. Perhaps its best known appearance is in Lewis Carroll's whimsical poem The Walrus and the Carpenter that appears in his book Through the Looking-Glass (1871). In the poem, the eponymous anti-heroes use trickery to consume a great number of oysters. Although Carroll accurately portrays the biological walrus's appetite for bivalve mollusks, oysters do not naturally occur within the Arctic and sub-Arctic range of the walrus.

Other examples of appearance of the animal in the popular culture include The Jungle Book story by Rudyard Kipling, where it is the "old Sea Vitch—the big, ugly, bloated, pimpled, fat-necked, long-tusked walrus of the North Pacific, who has no manners except when he is asleep" who tells the white seal Kotick where to seek advice for his mission.

Also, The Beatles recorded a song called I Am the Walrus.

See also

Notes

- ^ <http://www.walruses.net/>

- ^ a b c d e f Fay, F.H. (1985). Odobenus rosmarus. Mammalian Species. No. 238, pp. 1-7.

- ^ Dictionary.com

- ^ Etymology of mammal names, iberianature.com

- ^ Dansk Etymologisk Ordbog, Niels Age Nielsen, Gyldendal 1966

- ^ "morse, n., etymology of" The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. OED Online. Oxford University Press. http://dictionary.oed.com/.

- ^ Lento, G.M., Hickson, R.E., Chambers, G.K., Penny, D. 1995. Use of spectral analysis to test hypotheses on the origin of pinnipeds. Molecular Biology and Evolution 12(1) : 28-52.

- ^ Lento et al. 1995

- ^ a b Arnason U, Gullberg A, Janke A, et al. (2006) Pinniped phylogeny and a new hypothesis for their origin and dispersal Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 41 (2): 345-354.

- ^ Kohno, N. (2006) A new Miocene Odobenid (Mammalia: Carnivora) from Hokkaido, Japan, and its implications for odobenid phylogeny. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26:2, 411

- ^ a b Hoelzel, A. R. (Ed.) 2002. Marine mammal biology: an evolutionary approach. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0632 05232 5

- ^ Chapskii, K.K. 1940. Distribution of the walrus in the Laptev and East Siberian seas. Problemy Severa, 1940(6):80-94.

- ^ Born, E. W., Gjertz, I., and Reeves, R. R. (1995) Population assessment of Atlantic Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus L.). Meddelelser. Norsk Polarinstitut, Oslo, Norway. 138, pp.100.

- ^ Gilbert, J.R., G.A. Fedoseev, D. Seagars, E. Razlivalov, and A. LaChugin. 1992. Aerial census of Pacific walrus, 1990. USFWS R7/MMM Technical Report 92-1, 33 pp.

- ^ US Fish and Wildlife Service (2002), Stock Assessment Report: Pacific Walrus - Alaska Stock (PDF)

- ^ Dyke, A.S., J. Hooper, C.R. Harington, and J.M. Savelle (1999). The Late Wisconsinan and Holocene record of walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) from North America: A review with new data from Arctic and Atlantic Canada. Arctic 52: 160-181.

- ^ [NAMMCO] North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission. 1995. Report of the third meeting of the Scientific Committee. In: NAMMCO Annual Report 1995, NAMMCO, Tromsø, pp. 71-127.

- ^ North Atlantic Marine Mammal Commission, Status of Marine Mammals of the North Atlantic: The Atlantic Walrus (PDF)

- ^ Born, E. W., Andersen, L. W., Gjertz, I. and Wiig, Ø. 2001. A review of the genetic relationships of Atlantic walrus (Odobenus rosmarus rosmarus) east and west of Greenland. Polar Biology 24:713-718.

- ^ Fisheries and Oceans Canada. "Atlantic Walrus: Northwest Atlantic Population".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ "Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation protected species list".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|accessmonthday=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|accessyear=ignored (|access-date=suggested) (help) - ^ Berta, A. and J. L. Sumich. 1999. Marine mammals: evolutionary biology. Academic Press, San Diego, CA. 494 pp.

- ^ a b c d e Fay, F. H. (1982). "Ecology and Biology of the Pacific Walrus, Odobenus rosmarus divergens Illiger" United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service.

- ^ a b Ray, C., McCormick-Ray, J., Berg, P., Epstein, H.E., (2006) Pacific Walrus: Benthic bioturbator of Beringia, Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 403-419.

- ^ a b Kastelein, R.A., Stevens, S., & Mosterd, P. (1990) The sensitivity of the vibrissae of a Pacific Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus divergens). Part 2: Masking. Aquatic Mammals 16(2) : 78-87.

- ^ S. N. Nowicki, Ian Stirling, Becky Sjare (1997). Duration of stereotypes underwater vocal displays by make Atlantic walruses in relation to aerobic dive limit. Marine Mammal Science 13 (4), 566–575.

- ^ Sandell, M. (1990) The Evolution of Seasonal Delayed Implantation. The Quarterly Review of Biology. 65(1) : 23-42.

- ^ Evans, P.G.H. & Raga, J.A. (eds), 2001. Marine mammals: biology and conservation. London & New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Press

- ^ Schreer, J. F., K. M. Kovacs, and R. J. O'Hara Hines. 2001. Comparative diving patterns of pinnipeds and seabirds. Ecological Monographs 71:137–162.

- ^ Sheffield G, Fay FH, Feder H, Kelly BP (2001) Laboratory digestion of prey and interpretation of walrus stomach contents. Mar Mammal Sci 17:310–330

- ^ Levermann, N., Galatius, A., Ehlme, G., Rysgaard, S. and Born, E.W. (2003) Feeding behaviour of free-ranging walruses with notes on apparent dextrality of flipper use BMC Ecology 2003 3:9. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6785/3/9/

- ^ Lowry, L.F. and Frost, K.J. 1981. Feeding and Trophic Relationships of Phocid Seals and Walruses in the Eastern Bering Sea. (in: The Eastern Bering Sea Shelf: Oceanography & Resources vol. 2. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). University of Washington Press. 1981 : 813-824).

- ^ Mallory, M.L., Woo, K., Gaston, A.J., Davies, W.E., and Mineau, P (2004). Walrus (Odobenus rosmarus) predation on adult thick-billed murres (Uria lomvia) at Coats Island, Nunavut, Canada Polar Research 23 (1), 111–114.

- ^ Ovsyanikov, N. 1992. Ursus ubiquitous. BBC Wildlife. 10(12) : 18-26.

- ^ Bockstoce, J.R. and D.B. Botkin. 1982. The Harvest of Pacific Walruses by the Pelagic Whaling Industry, 1848 to 1914. Arctic and Alpine Research 14(3):183-188.

- ^ Chivers, C.J. 2002. A Big Game. New York Times Online, Aug 25.

- ^ US Fish and Wildlife Service (2007), Hunting and Use of Walrus by Alaska Natives (PDF)

- ^ Eleanor, E.W., M.M.R. Freeman, and J.C. Makus. 1996. Use and preference for Traditional Foods among Belcher Island Inuit. Artic 49(3):256-264.

- ^ Garlich-Miller, J.G. and D.M. Burn. 1997. Estimating the harvest of Pacific walrus, Odobenus rosmarus divergens, in Alaska. Fish. Bull. 97 (4):1043-1046.

- ^ Witting, L. and Born, E. W. 2005. An assessment of Greenland walrus populations. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 62(2):266-284.

- ^ Kaufman, M (2006-04-15). "Warming Arctic Is Taking a Toll, Peril to Walrus Young Seen as Result of Melting Ice Shelf". Washington Post. p. A7.

- ^ Template:IUCN2006

- ^ Ministry of Natural Resources of the Russian Federation protected species list: http://zapoved.ru/?act=oopt_rb_more&id=262, Retrieved on October 4, 2007

- ^ a b W. Bogoras. (1902) The Folklore of Northeastern Asia, as Compared with That of Northwestern America. American Anthropologist, New Series, Vol. 4, No. 4. (Oct. - Dec., 1902), pp. 577-683.

- ^ Boas, F. 1901. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. History, Vol. xvr, Pt. I. New York, p. 146

References

- Template:IUCN2006

- Marine Mammal Medicine, Leslie Dierauf and Frances Gulland, CRC Press 2001, ISBN 0-8493-0839-9

- Annales des sciences naturelles. Zoologie et biologie animale. Paris, Masson. ser.10:t.7

- Fay, F. H. (1982). "Ecology and Biology of the Pacific Walrus, Odobenus rosmarus divergens Illiger" United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service.

- Tagging and tracking Atlantic walrus (BBC Walrus tracker).