Peak oil

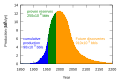

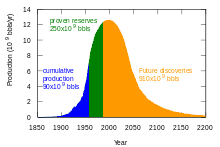

Peak oil is the point in time when the maximum rate of global petroleum extraction is reached, after which the rate of production enters terminal decline. Because the world's petroleum supply is effectively fixed, if global oil consumption is not mitigated before the decline phase begins, a world energy crisis may develop because the availability of conventional oil will drop causing prices to rise, perhaps dramatically. M. King Hubbert first used the theory in 1956 to accurately predict that United States oil production would peak between 1965 and 1970. His logistic model, now called Hubbert peak theory, has since been used to predict with reasonable accuracy the peak and decline of petroleum production of many countries, and has also proved useful in other limited-resource production-domains. According to the Hubbert model, the production rate of a limited resource will follow a roughly symmetrical bell-shaped curve based on the limits of exploitability and market pressures. Various modified versions of his original logistic model are used, using more complex functions to allow for real world factors. While each version is applied to a specific domain, the central features of the Hubbert curve (that production stops rising, flattens and then declines) remain unchanged, albeit with different profiles.

Some observers, such as petroleum industry experts Kenneth S. Deffeyes and Matthew Simmons, believe the high dependence of most modern industrial transport, agricultural and industrial systems on the relative low cost and high availability of oil will cause the post-peak production decline and possible severe increases in the price of oil to have negative implications for the global economy although predictions as to what exactly these negative effects would be vary greatly.

If political and economic change only occur in reaction to high prices and shortages rather than in reaction to the threat of a peak, then the degree of economic damage to importing countries will largely depend on how rapidly oil imports decline post-peak. According to the Export Land Model, oil exports drop much more quickly than production drops due to domestic consumption increases in exporting countries. Supply shortfalls would cause extreme price inflation, unless demand is mitigated with planned conservation measures and use of alternatives.[1]

Optimistic estimations of peak production forecast the global decline will begin by 2020 or later, and assume major investments in alternatives will occur before a crisis, circumventing the need for major changes in the lifestyle of heavily oil-consuming nations. These models show the price of oil at first escalating and then retreating as other types of fuel and energy sources are used.[2]

Pessimistic predictions of future oil production operate on the thesis that the peak has already occurred[3][4][5][6] or will occur shortly[7] and, as proactive mitigation may no longer be an option, predict a global depression, perhaps even initiating a chain reaction of the various feedback mechanisms in the global market which might stimulate a collapse of global industrial civilization, potentially leading to large population declines within a short period. Throughout the first two quarters of 2008, there were signs that a possible US recession was being made worse by a series of record oil prices.[8]

Demand for oil

The demand side of Peak oil is concerned with the consumption over time, and the growth of this demand. World crude oil demand grew an average of 1.76% per year from 1994 to 2006, with a high of 3.4% in 2003-2004. Demand growth is highest in the developing world.[9] World demand for oil is projected to increase 37% over 2006 levels by 2030, according to the US-based Energy Information Administration's (EIA) annual report. Demand will hit 118 million barrels per day (18.8×106 m3/d) from 2006's 86 million barrels (13.7×106 m3), driven in large part by the transportation sector.[10][11]

As countries develop, industry, rapid urbanization and higher living standards drive up energy use, most often of oil. Thriving economies such as China and India are quickly becoming large oil consumers.[12] China has seen oil consumption grow by 8% yearly since 2002, doubling from 1996-2006,[9] indicating a doubling rate of less than 10 years. China imported roughly half its oil in 2005, and swift continued growth is predicted by some while others differ, seeing the PRC's export dominated economy stepping back from high growth due to wage and price inflation and reduced demand from the US.[13] India's oil imports are expected to more than triple from 2005 levels by 2020, rising to 5 million barrels per day (790×103 m3/d).[14] In 2008, auto sales in China were expected to grow by as much as 15-20 percent, resulting in part from economic growth rates of over 10 percent for 5 years in a row. [15]

At the same time, US oil consumption has also increased. Between 1995 and 2005, American consumption grew from 17.7 million barrels a day to 20.7 million barrels a day, a 3 million barrel a day increase. China, by comparison, increased consumption by 3.6 million barrels a day in this time frame, from 3.4 million barrels a day to 7 million barrels a day. [16]

Energy demand is distributed amongst four broad sectors: transportation, residential, commercial, and industrial.[17][18] In terms of oil use, transportation is the largest sector and the one that has seen the largest growth in demand in recent decades. Largely this is made up of new demand for personal-use vehicles powered by internal combustion engines.[19] Cars and trucks are expected to cause almost 75% of the increase in oil consumption by India and China between 2001 and 2025.[20] As more countries develop, the demand for oil will increase further. This sector also has the highest consumption rates, accounting for approximately 68.9% of the oil used in the United States in 2006,[21] and 55% of oil use worldwide as documented in the Hirsch report. Transportation is therefore of particular interest to those seeking to mitigate the effects of Peak oil.

Population

Another significant factor on petroleum demand has been human population growth. Oil production per capita peaked in the 1970s.[22] The world’s population in 2030 is expected to be double that of 1980.[23] Author Matt Savinar predicts that oil production in 2030 will have declined back to 1980 levels as worldwide demand for oil significantly out-paces production.[24][25] Physicist Albert Bartlett claims that the rate of oil production per capita is falling, and that the decline has gone undiscussed because a politically incorrect form of population control may be implied by mitigation.[26] Oil production per capita has declined from 5.26 barrels per year (0.836 m3/a) in 1980 to 4.44 barrels per year (0.706 m3/a) in 1993,[27][23] but then increased to 4.79 barrels per year (0.762 m3/a) in 2005.[27][23] In 2006, the world oil production took a downturn from 84.631 to 84.597 million barrels per day (13.4553×106 to 13.4498×106 m3/d) although population has continued to increase. This has caused the oil production per capita to drop again to 4.73 barrels per year (0.752 m3/a).[27][23]

One factor that has so far helped ameliorate the effect of population growth on demand is the decline of population growth rate since the 1970s, although this is offset to a degree by increasing average longevity in developed nations. In 1970, the population grew at 2.1%. By 2007, the growth rate had declined to 1.167%.[28] However, oil production is still outpacing population growth to meet demand. World population grew by 6.2% from 6.07 billion in 2000 to 6.45 billion in 2005,[23] whereas according to BP, global oil production during that same period increased from 74.9 to 81.1 million barrels (11.91×106 to 12.89×106 m3), or by 8.2%.[29] or according to EIA, from 77.762 to 84.631 million barrels (12.3632×106 to 13.4553×106 m3), or by 8.8%.[27]

Agriculture and population limits

Because supplies of oil and gas are essential to modern agriculture techniques, a fall in global oil supplies could cause spiking food prices and unprecedented famine in the coming decades.[30][31][32][33][34] Geologist Dale Allen Pfeiffer contends that current population levels are unsustainable, and that to achieve a sustainable economy and avert disaster the United States population would have to be reduced by at least one-third, and world population by two-thirds.[35] The largest consumer of fossil fuels in modern agriculture is fertilizer production via the Haber process, which is essential to high perennial corn yields. If a sustainable non-petroleum source of electricity is developed, this process can be accomplished without fossil fuels using methods such as electrolysis.

Petroleum Supply

Reserves

All the easy oil and gas in the world has pretty much been found. Now comes the harder work in finding and producing oil from more challenging environments and work areas.

— William J. Cummings, major oil-company spokesman, December 2005, [36]

As Peak oil is concerned with the amount of oil produced over time, the amount of recoverable reserves is important as this determines the amount of oil that can potentially be extracted in the future.

Conventional crude oil reserves include all crude oil that is technically possible to produce from reservoirs through a well bore, using primary, secondary, improved, enhanced, or tertiary methods. This does not include liquids extracted from mined solids or gasses (tar sands, oil shales, gas-to-liquid processes, or coal-to-liquid processes).[37]

Oil reserves are classified as proven, probable and possible. Proven reserves are generally intended to have at least 90% or 95% certainty of containing the amount specified. Probable Reserves have an intended probability of 50%, and the Possible Reserves an intended probability of 5% or 10%.[38] Current technology is capable of extracting about 40% of the oil from most wells. Some speculate that future technology will make further extraction possible,[39] but to some, this future technology is already considered in Proven and Probable reserve numbers.

In many major producing countries, the majority of reserves claims have not been subject to outside audit or examination. Most of the easy-to-extract oil has been found.[36] Recent price increases have led to oil exploration in areas where extraction is much more expensive, such as in extremely deep wells, extreme downhole temperatures, and environmentally sensitive areas or where high technology will be required to extract the oil. A lower rate of discoveries per explorations has led to a shortage of drilling rigs, increases in steel prices, and overall increases in costs due to complexity.[40][41]

The peak of world oilfield discoveries occurred in 1965.[42] Because world population grew faster than oil production, production per capita peaked in 1979 (preceded by a plateau during the period of 1973-1979).[22]

The amount of oil discovered each year also peaked during the 1960s at around 55 Gb/year, and has been falling steadily since (in 2004/2005 it was about 12 Gb/year). Reserves in effect peaked in 1980, when production first surpassed new discoveries, though creative methods of recalculating reserves has made this difficult to establish exactly.[5]

Concerns over stated reserves

World reserves are confused and in fact inflated. Many of the so called reserves are in fact resources. They’re not delineated, they’re not accessible, they’re not available for production

— Sadad I. Al Husseini, former VP of Aramco, October 2007.

By Al-Husseini's estimate, 300 billion (64×109 m3) of the world’s 1,200 billion barrels (190×109 m3) of proved reserves should be recategorized as speculative resources.[6]

One difficulty in forecasting the date of peak oil is the opacity surrounding the oil reserves classified as 'proven'. Many worrying signs concerning the depletion of 'proven reserves' have emerged in recent years.[43][44] This was best exemplified by the 2004 scandal surrounding the 'evaporation' of 20% of Shell's reserves.[45]

For the most part, 'proven reserves' are stated by the oil companies, the producer states and the consumer states. All three have reasons to overstate their proven reserves:

- Oil companies may look to increase their potential worth.

- Producer countries are bestowed a stronger international stature

- Governments of consumer countries may seek a means to foster sentiments of security and stability within their economies and among consumers.

The Energy Watch Group (EWG) 2007 report shows total world Proved (P95) plus Probable (P50) reserves to be between 854 and 1,255 Gb (30 to 40 years of supply if demand growth were to stop immediately). Major discrepancies arise from accuracy issues with OPEC's self-reported numbers. Besides the possibility that these nations have overstated their reserves for political reasons (during periods of no substantial discoveries), over 70 nations also follow a practice of not reducing their reserves to account for yearly production. 1,255 Gb is therefore a best-case scenario.[5] Analysts have suggested that OPEC member nations have economic incentives to exaggerate their reserves, as the OPEC quota system allows greater output for countries with greater reserves.[39]

The following table shows refutable jumps in stated reserves without associated discoveries, as well as the lack of depletion despite yearly production:

| Declared reserves with suspicious increases in bold purple (in billions of barrels) from Colin Campbell, SunWorld, 80'-95 | |||||||

| Year | Abu Dhabi | Dubai | Iran | Iraq | Kuwait | Saudi Arabia | Venezuela |

| 1980 | 28.00 | 1.40 | 58.00 | 31.00 | 65.40 | 163.35 | 17.87 |

| 1981 | 29.00 | 1.40 | 57.50 | 30.00 | 65.90 | 165.00 | 17.95 |

| 1982 | 30.60 | 1.27 | 57.00 | 29.70 | 64.48 | 164.60 | 20.30 |

| 1983 | 30.51 | 1.44 | 55.31 | 41.00 | 64.23 | 162.40 | 21.50 |

| 1984 | 30.40 | 1.44 | 51.00 | 43.00 | 63.90 | 166.00 | 24.85 |

| 1985 | 30.50 | 1.44 | 48.50 | 44.50 | 90.00 | 169.00 | 25.85 |

| 1986 | 31.00 | 1.40 | 47.88 | 44.11 | 89.77 | 168.80 | 25.59 |

| 1987 | 31.00 | 1.35 | 48.80 | 47.10 | 91.92 | 166.57 | 25.00 |

| 1988 | 92.21 | 4.00 | 92.85 | 100.00 | 91.92 | 166.98 | 56.30 |

| 1989 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 92.85 | 100.00 | 91.92 | 169.97 | 58.08 |

| 1990 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 93.00 | 100.00 | 95.00 | 258.00 | 59.00 |

| 1991 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 93.00 | 100.00 | 94.00 | 258.00 | 59.00 |

| 1992 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 93.00 | 100.00 | 94.00 | 258.00 | 62.70 |

| 2004 | 92.20 | 4.00 | 132.00 | 115.00 | 99.00 | 259.00 | 78.00 |

Kuwait, for example, was reported by a January 2006 issue of Petroleum Intelligence Weekly to have only 48 Gb in reserve, of which only 24 were "fully proven." This report was based on "leaks of confidential documents" from Kuwait, and has not been formally denied by the Kuwaiti authorities. This leaked document dates back from 2001[46] so the figure includes oil that have been produced since 2001, roughly 5-6 billion barrels[47], but excludes revisions or discoveries made since then. Additionally, the reported 1.5 Gb of oil burned off by Iraqi soldiers in the first Gulf War[48] are conspicuously missing from Kuwait's figures.

On the other hand investigative journalist Greg Palast has argued that oil companies have an interest in making oil look more rare than it is in order to justify higher prices.[49] Other analysts in 2003 argued that oil producing countries understated the extent of their reserves in order to drive up the price of oil.[50]

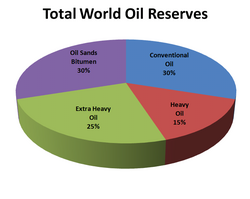

Unconventional sources

Unconventional sources, such as heavy crude oil, tar sands, and oil shale are not counted as part of oil reserves. However, oil companies can book them as proven reserves after opening a strip mine or thermal facility for extraction. Oil industry sources such as Rigzone have stated that these unconventional sources are not as efficient to produce, however, requiring extra energy to refine, resulting in higher production costs and up to three times more greenhouse gas emissions per barrel (or barrel equivalent).[51] While the energy used, resources needed, and environmental effects of extracting unconventional sources has traditionally been prohibitively high, the three major unconventional oil sources being considered for large scale production are the extra heavy oil in the Orinoco Belt of Venezuela,[52] the Athabasca oil sands in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin,[53] and the oil shales of the Green River Formation in Colorado, Utah and Wyoming in the United States.[54][55] Chuck Masters of the USGS estimates that, "Taken together, these resource occurrences, in the Western Hemisphere, are approximately equal to the Identified Reserves of conventional crude oil accredited to the Middle East."[56] Authorities familiar with the resources believe that the world's ultimate reserves of non-conventional oil are several times as large as those of conventional oil and will be highly profitable for companies as a result of higher prices in the 21st century.[57]

Despite the large quantities of oil available in non-conventional sources, Matthew Simmons argues that limitations on production prevent them from becoming an effective substitute for conventional crude oil. Simmons states that "these are high energy intensity projects that can never reach high volumes" to offset significant losses from other sources.[59] Another study claims that even under highly optimistic assumptions, "Canada's oil sands will not prevent peak oil," although production could reach 5 million bbl/day by 2030 in a "crash program" development effort.[60] Moreover, oil extracted from these sources typically contains contaminants such as sulfur, heavy metals and carbon that are energy-intensive to extract and leave highly toxic tailings.[61] The same applies to much of the Middle East's undeveloped conventional oil reserves, much of which is heavy, viscous and contaminated with sulfur and metals to the point of being unusable.[62] However, recent high oil prices make these sources more financially appealing.[39] A study by Wood Mackenzie suggests that within 15 years all the world’s extra oil supply will likely come from unconventional sources.[63]

A 2003 article in Discover magazine claimed that thermal depolymerization could be used to manufacture oil indefinitely, out of garbage, sewage, and agricultural waste. The article claimed that the cost of the process was $15 per barrel.[64] A follow-up article in 2006 stated that the cost was actually $80 per barrel because the feedstock which had previously been considered as hazardous waste now had market value.[65]

Production

The point in time when peak global oil production occurs is the measure which defines Peak oil. This is because production capacity is the main limitation of supply. Therefore, when production decreases, it becomes the main bottleneck to the petroleum supply/demand equation.

World wide oil discoveries have been less than annual production since 1980.[5] According to several sources, world-wide production is past or near its maximum.[3][4][5][6][7]

World oil production growth trends were flat from 2005 to 2008. According to a January 2007 International Energy Agency report, global supply (which includes biofuels, non-crude sources of petroleum, and use of strategic oil reserves, in addition to crude production) averaged 85.24 million barrels per day (13.552×106 m3/d) in 2006, up 0.76 million barrels per day (121×103 m3/d) (0.9%), from 2005.[66] Average yearly gains in global supply from 1987 to 2005 were 1.2 million barrels per day (190×103 m3/d) (1.7%).[66]

The IEA's March 2008 Oil Market report showed global supply to be 87.5 mb/d, compared to 84.3 mb/d in July 2007, a 3.8% increase on that interval. The great bulk of the increase came in the non-OPEC sector, which now makes up 65% of global production.

Of the largest 21 fields, at least 9 are in decline.[67] In April, 2006, a Saudi Aramco spokesman admitted that its mature fields are now declining at a rate of 8% per year (with a national composite decline of about 2%).[68] This information has been used to argue that Ghawar, which is the largest oil field in the world and responsible for approximately half of Saudi Arabia's oil production over the last 50 years, has peaked.[69][39] The world's second largest oil field, the Burgan field in Kuwait, entered decline in November, 2005.[70] According to a study of the largest 811 oilfields conducted in early 2008 by CERA, the average rate of field decline is 4.5% per year. There are also projects projected to begin production within the next decade which are hoped to offset these declines. The CERA report projects 2017 production level of over 100mbpd.[71] Kjell Aleklett of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil & Gas agrees with their decline rates, but considers the rate of new fields coming online -- 100% of all projects in development, but with 30% of them experiencing delays, plus a mix of new small fields and field expansions -- overly optimistic. [72]

Mexico announced that its giant Cantarell Field entered depletion in March, 2006,[73] due to past overproduction. In 2000, PEMEX built the largest nitrogen plant in the word in an attempt to maintain production through nitrogen injection into the formation,[74] but by 2006, Cantarell was declining at a rate of 13% per year.[75]

OPEC had vowed in 2000 to maintain a production level sufficient to keep oil prices between $22–28 per barrel, but did not prove possible. In its 2007 annual report, OPEC projected that it could maintain a production level which would stabilize the price of oil at around $50–60 per barrel until 2030.[76] On November 18, 2007, with oil above $98 a barrel, King Abdullah of Saudi Arabia, a long-time advocate of stabilized oil prices, announced that his country would not increase production in order to lower prices.[77] Saudi Arabia's inability, as the world's largest supplier, to stabilize prices through increased production during that period suggests that no nation or organization had the spare production capacity to lower oil prices. The implication is that those major suppliers who had not yet peaked were operating at or near full capacity.[39]

Commentators have pointed to the Jack 2 deep water test well in the Gulf of Mexico, announced September 5, 2006,[78] as evidence that there is no imminent peak in global oil production. According to one estimate, the field could account for up to 11% of US production within seven years.[79] However, even though oil discoveries are expected after the peak oil of production is reached,[80] the new reserves of oil will be harder to find and extract. The Jack 2 field, for instance, is more than 20,000 feet (6,100 m) under the sea floor in 7,000 feet (2,100 m) of water, requiring 8.5 kilometers of pipe to reach. Additionally, even the maximum estimate of 15 billion barrels (2.4×109 m3) represents slightly less than 2 years of U.S. consumption at present levels.[81]

The increasing investment in harder-to-reach oil is a sign of oil companies' belief in the end of easy oil.[36] In addition, while it is widely believed that increased oil prices spur an increase in production, an increasing number of oil industry insiders are now coming to believe that even with higher prices, oil production is unlikely to increase significantly beyond its current level. Among the reasons cited are both geological factors as well as "above ground" factors that are likely to see oil production plateau near its current level.[82]

Nationalisation of oil supplies

Another factor affecting global oil supply is the nationalization of oil reserves by producing nations. The nationalization of oil occurs as countries begin to deprivatize oil production and withhold exports. Kate Dourian, Platts' Middle East editor, points out that while estimates of oil reserves may vary, politics have now entered the equation of oil supply. "Some countries are becoming off limits. Major oil companies operating in Venezuela find themselves in a difficult position because of the growing nationalization of that resource. These countries are now reluctant to share their reserves."[83]

According to consulting firm PFC Energy, only 7% of the world's estimated oil and gas reserves are in countries that allow companies like ExxonMobil free rein. Fully 65% are in the hands of state-owned companies such as Saudi Aramco, with the rest in countries such as Russia and Venezuela, where access by Western companies is difficult. The PFC study implies political factors are limiting capacity increases in Mexico, Venezuela, Iran, Iraq, Kuwait and Russia. Saudi Arabia is also limiting capacity expansion, but because of a self-imposed cap, unlike the other countries.[84] As a result of not having access to countries amenable to oil exploration, ExxonMobil is not making nearly the investment in finding new oil that it did in 1981.[85]

Alternately, commodities trader Raymond Learsy, author of Over a Barrel: Breaking the Middle East Oil Cartel, contends that OPEC has trained consumers to believe that oil is a much more finite resource than it is. To back his argument, he points to past false alarms and apparent collaboration.[50] He also believes that Peak Oil analysts are conspiring with OPEC and the oil companies to create a "fabricated drama of peak oil" in order to drive up oil prices and profits. It is worth noting oil had risen to a little over $30/barrel at that time. A counter-argument was given in the Huffington Post after he and Steve Andrews, co-founder of ASPO, debated on CNBC in June 2007.[86]

Timing of peak oil

M. King Hubbert initially predicted in 1974 that peak oil would occur in 1995 "if current trends continue."[87] However, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, global oil consumption actually dropped (due to the shift to energy-efficient cars,[88] the shift to electricity and natural gas for heating,[89] and other factors), then rebounded to a lower level of growth in the mid 1980s. Thus oil production did not peak in 1995, and has climbed to more than double the rate initially projected. This underscores the fact that the only reliable way to identify the timing of peak oil will be in retrospect. However, predictions have been refined through the years as up-to-date information becomes more readily available, such as new reserve growth data.[90] Predictions of the timing of peak oil include the possibilities that it has recently occurred, that it will occur shortly, or that a plateau of oil production will sustain supply for up to 100 years. None of these predictions dispute the peaking of oil production, but disagree only on when it will occur.

According to Mathew Simmons, author of Twilight in the Desert: The Coming Saudi Oil Shock and the World Economy, "...peaking is one of these fuzzy events that you only know clearly when you see it through a rear view mirror, and by then an alternate resolution is generally too late."[91]

Pessimistic predictions of future oil production

Saudi Arabia's King Abdulla told his subjects in 1998, "The oil boom is over and will not return... All of us must get used to a different lifestyle." Since then he has implemented a series of corruption reforms and government programs intended to lower Saudi Arabia's dependence on oil revenues. The royal family was put on notice to end its history of excess and new industries were created to diversify the national economy.[92]

The Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas (ASPO) predicted in their January 2008 newsletter that the peak in all oil (including non-conventional sources), would occur in 2010. This is earlier than the July 2007 newsletter prediction of 2011.[93] ASPO Ireland in its May 2008 newsletter, number 89, revised its depletion model and advanced the date of the peak of overall liquids from 2010 to 2007.[94]

Kenneth S. Deffeyes argued at one point that world oil production peaked on December 16 2005.[3]

Texas oilman T. Boone Pickens stated in 2005 that worldwide conventional oil production was very close to peaking.[95] On June 17, 2008, in testimony before the U.S. Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, Pickens stated that "I do believe you have peaked out at 85 million barrels a day globally,".[96] Data from the US Energy Information Administration show that world production leveled out in 2004, and reached a peak in the third quarter of 2006,[4] and an October 2007 retrospective report by the Energy Watch Group concluded that this was the peak of conventional oil production.[5]

Sadad Al Husseini, former head of Saudi Aramco's production and exploration, stated in an October 29, 2007 interview that oil production had likely already reached its peak in 2006,[6] and that assumptions by the IEA and EIA of production increases by OPEC to over 45 MB/day are "quite unrealistic."

The July 2007 IEA Medium-Term Oil Market Report projected a 2% non-OPEC liquids supply growth in 2007-2009, reaching 51.0 mb/d in 2008, receding thereafter as the slate of verifiable investment projects diminishes. They refer to this decline as a plateau. The report expects only a small amount of supply growth from OPEC producers, with 70% of the increase coming from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Angola as security and investment issues continue to impinge on oil exports from Iraq, Nigeria and Venezuela.[97]

In October 2007, the Energy Watch Group, a German research group founded by MP Hans-Josef Fell, released a report claiming that oil production peaked in 2006 and will decline by several percent annually. The authors predict negative economic effects and social unrest as a result.[98][5] They state that the IEA production plateau prediction uses purely economic models which rely on an ability to raise production and discovery rates at will.[5]

Matthew Simmons, Chairman of Simmons & Company International, said on October 26, 2006 that global oil production may have peaked in December 2005, though he cautions that further monitoring of production is required to determine if a peak has actually occurred.[99]

Optimistic predictions of future oil production

Non-'peakists' can be divided into several different categories based on their specific criticism of Peak Oil. Some claim that any peak will not come soon or have a dramatic effect on the world economies. Others claim we will not reach a peak for technological reasons, while still others claim our oil reserves are regenerated quickly over time.

Plateau oil

CERA, which counts unconventional sources in reserves while discounting EROEI, believes that global production will eventually follow an “undulating plateau” for one or more decades before declining slowly.[2] In 2005 the group had predicted that "petroleum supplies will be expanding faster than demand over the next five years."[100]

Energy Information Administration and USGS 2000 reports

The U.S. Energy Information Administration projects world consumption of oil to increase to 98.3 million barrels per day (15.63×106 m3/d) in 2015 and 118 million barrels per day (18.8×106 m3/d) in 2030.[101] This would require a more than 35% increase in world oil production by 2030. A 2004 paper by the Energy Information Administration based on data collected in 2000 disagrees with Hubbert peak theory on several points:[19]

- Explicitly incorporates demand into model as well as supply

- Does not assume pre/post-peak symmetry of production levels

- Models pre- and post-peak production with different functions (exponential growth and constant reserves-to-production ratio, respectively)

- Assumes reserve growth, including via technological advancement and exploitation of small reservoirs

The EIA estimates of future oil supply are countered by Sadad Al Husseini, retired VP Exploration of Aramco, who calls it a 'dangerous over-estimate'.[102] Husseini also points out that population growth and the emergence of China and India means oil prices are now going to be structurally higher than they have been.

Colin Campbell argues that the 2000 USGS estimates is a methodologically flawed study that has done incalculable damage by misleading international agencies and governments. Campbell dismisses the notion that the world can seamlessly move to more difficult and expensive sources of oil and gas when the need arises. He argues that oil is in profitable abundance or not there at all, due ultimately to the fact that it is a liquid concentrated by nature in a few places having the right geology. Campbell believes OPEC countries raised their reserves to get higher oil quotas and to avoid internal critique. He also points out that the USGS failed to extrapolate past discovery trends in the world’s mature basins.[103]

No Peak Oil

Yes, there are finite resources in the ground, but you never get to that point.

— Jeff Hatlen, an engineer with Chevron[104]

Some commentators, such as economist Michael Lynch, say that the Hubbert Peak theory is flawed and that there is no imminent peak in oil production; a view sometimes referred to as "cornucopian" by believers in Hubbert Peak Theory. Lynch argued in 2004 that production is determined by demand as well as geology, and that fluctuations in oil supply are due to political and economic effects as well as the physical processes of exploration, discovery and production.[105] This idea is echoed by Jad Mouawad, who explains that as oil prices rise, new extraction technologies become viable, thus expanding the total recoverable oil reserves. This, according to Mouwad, is one explanation of the changes in peak production estimates.[104]

Abdullah S. Jum'ah, President, Director and CEO of Aramco, states that the world has adequate reserves of conventional and nonconventional oil sources for more than a century,[106][107] though Sadad Al-Husseini, a former Vice President of Aramco who formerly maintained that production would peak in 10-15 years, stated in October 2007 that oil production peaked in 2006.[6]

Abiogenesis

The theory that petroleum is derived from biogenic processes is held by the overwhelming majority of petroleum geologists. Abiogenic theorists however, such as the late professor of astronomy Thomas Gold at Cornell University, assert that the source of oil may not be a limited supply of “fossil fuels”, but instead an abiotic process. They theorize that if abiogenic petroleum sources are found to be abundant, Earth would contain vast reserves of untapped petroleum.[108] A February 2008 article on abiogenic low-carbon hydrocarbon production using data from experiments at Lost City (hydrothermal field) reported how the abiotic synthesis of C1 to C4 hydrocarbons (though not petroleum) may occur in the presence of ultramafic rocks, water, and moderate amounts of heat.[109]

The most important counter arguments to the abiotic theory involve various biomarkers which have been found in all samples of all the oil and gas accumulations found to date. The prevailing view among geologists and petroleum engineers is that this evidence "provides irrefutable proof that 99.99999% of all the oil and gas accumulations found up to now in the planet earth have a biologic origin." In this process, oil is generated from kerogen by pyrolysis.[110] While, Thomas Gold hypothesized that bacteria exist deep within the Earth's crust, and are the source of the biomarkers,[111] these bacteria have not been found, the natural abiogenic formation of high-carbon hydrocarbons has not been demonstrated, and evidence for the biotic origin of petroleum is abundant.

Possible effects and consequences of Peak Oil

- For information on the timing of peak oil, see Predicting the timing of peak oil

The widespread use of fossil fuels has been one of the most important stimuli of economic growth and prosperity since the industrial revolution, allowing humans to participate in takedown, or the consumption of energy at a greater rate than it is being replaced. Some believe that when oil production decreases, human culture and modern technological society will be forced to change drastically. The impact of Peak oil will depend heavily on the rate of decline and the development and adoption of effective alternatives. If alternatives are not forthcoming, the products produced with oil (including fertilizers, detergents, solvents, adhesives, and most plastics) would become scarce and expensive. At the very least this could lower living standards in developed and developing countries alike, and in the worst case lead to worldwide economic collapse. With increased tension between countries over dwindling oil supplies, political situations may change dramatically and inequalities between countries and regions may become exacerbated.

The Hirsch Report

In 2005, the US Department of Energy published a report titled Peaking of World Oil Production: Impacts, Mitigation, & Risk Management.[112] Known as the Hirsch report, it stated, "The peaking of world oil production presents the U.S. and the world with an unprecedented risk management problem. As peaking is approached, liquid fuel prices and price volatility will increase dramatically, and, without timely mitigation, the economic, social, and political costs will be unprecedented. Viable mitigation options exist on both the supply and demand sides, but to have substantial impact, they must be initiated more than a decade in advance of peaking."

Conclusions from the Hirsch Report and three scenarios

- World oil peaking is going to happen, and will likely be abrupt.

- Oil peaking will adversely affect global economies, particularly those most dependent on oil.

- Oil peaking presents a unique challenge (“it will be abrupt and revolutionary”).

- The problem is liquid fuels (growth in demand mainly from the transportation sector).

- Mitigation efforts will require substantial time.

- 20 years is required to transition without substantial impacts

- A 10 year rush transition with moderate impacts is possible with extraordinary efforts from governments, industry, and consumers

- Late initiation of mitigation may result in severe consequences.

- Both supply and demand will require attention.

- It is a matter of risk management (mitigating action must come before the peak).

- Government intervention will be required.

- Economic upheaval is not inevitable (“given enough lead-time, the problems can be solved with existing technologies.”)

- More information is needed to more precisely determine the peak time frame.

Possible Scenarios:

- Waiting until world oil production peaks before taking crash program action leaves the world with a significant liquid fuel deficit for more than two decades.

- Initiating a mitigation crash program 10 years before world oil peaking helps considerably but still leaves a liquid fuels shortfall roughly a decade after the time that oil would have peaked.

- Initiating a mitigation crash program 20 years before peaking appears to offer the possibility of avoiding a world liquid fuels shortfall for the forecast period.

Other predictions

Agricultural effects

Since the 1940s, agriculture has dramatically increased its productivity, due largely to the use of petrochemical derived pesticides, fertilizers, and increased mechanization (the so-called Green Revolution). This has allowed world population to more than double over the last 50 years. Every energy unit delivered in food grown using modern techniques requires over ten energy units to produce and deliver.[citation needed] Modern agriculture relies heavily on petrochemicals and mechanization, and there are few or no quickly available non-petroleum based alternatives. Because of this, many agriculture, petroleum, sociology, and ecology experts have warned that the ever decreasing supply of oil will inflict major damage to the modern industrial agriculture system[113] causing a collapse in food production ability and food shortages.

One example of the chain reactions which could possibly be caused by peak oil issues involves the problems caused by farmers raising crops such as corn for non-food use in an effort to help mitigate peak oil. This has already lowered food production.[114] This food vs fuel issue will be exacerbated as demand for ethanol fuel rises. Rising food and fuel costs has already limited the abilities of some charitable donors to send food aid to starving populations.[115] In the UN, some warn that the recent 60% rise in wheat prices could cause "serious social unrest in developing countries."[116][117] In 2007, higher incentives for farmers to grow non-food biofuel crops[118] combined with other factors (such as over-development of former farm lands, rising transportation costs, climate change, growing consumer demand in China and India, and population growth)[119] to cause food shortages in Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Mexico, as well as rising food prices around the globe.[120][121] As of December 2007, 37 countries faced food crises, and 20 had imposed some sort of food-price controls. Some of these shortages resulted in food riots and even deadly stampedes.[122][123][124]

Another major petroleum issue in agriculture is the effect of petroleum supplies will have on fertilizer production. By far the biggest fossil fuel input to agriculture is the use of natural gas as a hydrogen source for the Haber-Bosch fertilizer-creation process.[125] Natural gas is used because it is the cheapest currently available source of hydrogen.[126][127] When oil production becomes so scarce that natural gas is used as a partial stopgap replacement, and hydrogen use in transportation increases, natural gas will become much more expensive. If other sources of hydrogen are not available to replace the Haber process, in amounts sufficient to supply transportation and agricultural needs, this major source of fertilizer would either become extremely expensive or unavailable. This would either cause food shortages or dramatic rises in food prices.

Mitigation of agricultural effects

One effect oil shortages could have on agriculture is a full return to organic agriculture. In light of peak oil concerns, organic methods are much more sustainable than contemporary practices because they use no petroleum-based pesticides, herbicides, or fertilizers. Some farmers using modern organic-farming methods have reported yields as high as those available from conventional farming.[128][129][130][131] Organic farming may however be more labor-intensive and would require a shift of work force from urban to rural areas.[132]

It has been suggested that rural communities might obtain fuel from the biochar and synfuel process, which uses agricultural waste to provide charcoal fertilizer, some fuel and food, instead of the normal food vs fuel debate. As the synfuel would be used on site, the process would be more efficient and may just provide enough fuel for a new organic-agriculture fusion.[citation needed][clarification needed]

It has been suggested that some transgenic plants may some day be developed which would allow for maintaining or increasing yields while requiring fewer fossil fuel derived inputs than conventional crops.[133] The possibility of success of these programs is questioned by ecologists and economists concerned with unsustainable GMO practices such as terminator seeds,[134][135] and a January 2008 report shows that GMO practices have failed to address sustainability issues.[136] While there has been some research on sustainability using GMO crops, at least one hyped and prominent multi-year attempt by Monsanto has been unsuccessful, though during the same period traditional breeding techniques yielded a more sustainable variety of the same crop.[137] Additionally, a survey by the bio-tech industry of subsistence farmers in Africa to discover what GMO research would most benefit sustainable agriculture only identified non-transgenic issues as areas needing to be addressed.[138] Nonetheless, some governments in Africa continue to view investments in new transgenic technologies as an essential component of efforts to improve sustainability.[139]

Transportation and housing

A majority of Americans live in suburbs, a type of low-density settlement designed around universal personal automobile use. Commentators such as James Howard Kunstler argue that because over ninety percent of transportation in the United States relies on oil, the suburbs' reliance on the automobile is an unsustainable living arrangement. Peak oil would leave many Americans unable to afford petroleum based fuel for their cars, and force them to move to higher density areas, where walking and public transportation are more viable options. Suburbia may become the "slums of the future."[140][141] Methods which have been suggested for mitigating this include transit-oriented development, new trains, new pedestrianism, smart growth, shared space, and New Urbanism.

Mitigation

To avoid the serious social and economic implications a global decline in oil production could entail, the Hirsch report emphasized the need to find alternatives at least 10-20 years before the peak, and to phase out the use of petroleum over that time,[142] similar to the plan Sweden announced in 2005. Such mitigation could include energy conservation, fuel substitution, and the use of non-conventional oil. Because mitigation can reduce the consumption of traditional petroleum sources, it can also affect the timing of peak oil and the shape of the Hubbert curve.

Positive aspects of peak oil

There are those who believe that peak oil should be viewed as a positive event.[143] Many of these critics reason that if the price of oil rises high enough, the use of alternative clean fuels could help control the pollution of fossil fuel use as well as mitigate global warming.[144] Others, in particular anarcho-primitivists, are hopeful that it will cause or contribute to the collapse of civilization.[145]

Peak oil for individual nations

Peak Oil as a concept applies globally, but it is based on the summation of individual nations experiencing peak oil. In State of the World 2005, Worldwatch Institute observes that oil production is in decline in 33 of the 48 largest oil-producing countries.[146] Other countries have also passed their individual oil production peaks.

The following list shows significant oil-producing nations and their approximate peak oil production years, organized by year.[147]

- Japan: 1932 (assumed; source does not specify)

- Germany: 1966

- Libya: 1970

- Venezuela: 1970

- USA: 1970[148]

- Iran: 1974

- Nigeria: 1979

- Tobago: 1981[149]

- Egypt: 1987[150]

- Russia: an artificial peak occurred in 1987 shortly before the Collapse of the Soviet Union, but production subsequently recovered, making Russia the second largest oil exporter in the world. Figures from early 2008, statements by officials, and analysis suggest that production may have peaked in 2006/2007.[151][152]

- France: 1988

- Indonesia: 1991[153]

- Syria: 1996 [154]

- India: 1997

- New Zealand: 1997[155]

- UK: 1999

- Norway: 2000[156]

- Oman: 2000[157]

- Mexico: 2003

- Australia (disputed): 2004; 2001

Peak oil production has not been reached in the following nations (these numbers are estimates and subject to revision):[158]

- Iraq: 2018

- Kuwait: 2013

- Saudi Arabia: 2014

In addition, the most recent International Energy Agency and US Energy Information Administration production data show record and rising production in Canada and China.

Related peaks

The amount of oil discovered each year peaked in the mid 1960's at around 55 Gb/year, and has been falling steadily since then (in 2004/2005 it was about 12 Gb/year).[42] Reserves in effect peaked in 1980, when production first surpassed new discoveries. Because of world population growth, oil production per capita peaked in 1979 (preceded by a plateau during the period of 1973-1979).[22]

Hubbert's curve has also been used to describe the peak production of other non-renewable resources, such as natural gas, coal, uranium, metals, and even renewable resources like water and fish.[159]

In 2008, a report by Cambridge Energy Research Associates stated that 2007 had been the year of peak gasoline usage in the United States, and that record energy levels would cause an "enduring shift" in energy consumption practices.[160] According to the report, in April gas consumption had been lower than a year before for the sixth strait month, suggesting 2008 would be the first year US gasoline usage declined in 17 years. The total miles driven in the US peaked in 2006.[161]

Oil price

In terms of 2007 inflation adjusted dollars, the price of oil peaked on 30 June 2008 at over $143 a barrel. Before this period, the maximum inflation adjusted price was the equivalent of $95-100, in 1980.[162] Crude oil prices in the last several years have steadily risen from about $25 a barrel in August of 2003 to over $130 a barrel in May of 2008, with the most significant increases happening within the last year. These prices are well above those which caused the the 1973 and 1979 energy crises. This has contributed to fears of an economic recession similar to that of the early 1980s.[163] One important indicator which supported the possibility that the price of oil had begun to have an effect on economies was that in the United States, gasoline consumption dropped by .5% in the first two months of 2008,[164] compared to a drop of .4% total in 2007.[165]

However some claim the decline in the US dollar against other significant currencies from 2007 to 2008 is a significant part of oil's price increases from $66 to $130.[166]. The dollar lost approximately 14% of its value against the Euro from May 2007 to May 2008, and the price of oil rose 96% in the same time period.

Helping to fuel these price increases were reports that petroleum production is at[3][4][5][6] or near full capacity.[167][7][168] In June 2005, OPEC admitted that they would 'struggle' to pump enough oil to meet pricing pressures for the fourth quarter of that year.[169]

Demand pressures on oil have been strong. Global consumption of oil rose from 30 billion barrels (4.8×109 m3) in 2004 to 31 billion in 2005. These consumption rates are far above new discoveries for the period, which had fallen to only eight billion barrels of new oil reserves in new accumulations in 2004.[170] In 2005, consumption was within 2 million barrels per day (320×103 m3/d) of production, and at any one time there are about 54 days of stock in the OECD system plus 37 days in emergency stockpiles.

Besides supply and demand pressures, at times security related factors may have contributed to increases in prices,[171] including the "War on Terror," missile launches in North Korea,[172] the Crisis between Israel and Lebanon,[173] nuclear brinkmanship between the US and Iran,[174] and reports from the U.S. Department of Energy and others showing a decline in petroleum reserves,[175]

Another factor in oil price is the cost of extracting crude. As the extraction of oil has become more difficult, oil's historically high ratio of Energy Returned on Energy Invested has seen a significant decline. The increased price of oil makes non-conventional sources of oil retrieval more attractive. For example, the so-called "tar sands" are actually a reserve of bitumen, a heavier, lower value oil compared to conventional crude. It only became attractive to production companies when oil prices exceeded about $25/bbl, high enough to cover the costs of production and upgrading to synthetic crude.

Effects of rising oil prices

In the past, the price of oil has led to economic recessions, such as the 1973 and 1979 energy crises. The effect the price of oil has on an economy is known as a price shock. In many European countries, which have high taxes on fuels, such price shocks could potentially be mitigated somewhat by temporarily or permanently suspending the taxes as fuel costs rise.[177] This method of softening price shocks is less in countries with much lower gas taxes, such as the United States.

Some economists predict that a substitution effect will spur demand for alternate energy sources, such as coal or liquefied natural gas. This substitution can only be temporary, as coal and natural gas are finite resources as well.

Prior to the run-up in fuel prices, many motorists opted for larger, less fuel-efficient sport utility vehicles and full-sized pickups in the United States, Canada and other countries. This trend has been reversing due to sustained high prices of fuel. The September 2005 sales data for all vehicle vendors indicated SUV sales dropped while small cars sales increased. Hybrid and diesel vehicles are also gaining in popularity.[178]

Historical understanding of world oil supply limits

Although the earth's finite oil supply means that peak oil is inevitable, technological innovations in finding and drilling for oil have at times changed the understanding of the total oil supply on Earth. As scientific understanding of petroleum geology has increased, so has our understanding of the earth's total recoverable reserves. Since 1965, major oil surveys have averaged a 95% confidence Estimated Ultimate Retrieval (P95 EUR) of a little under 2,000 billion barrels (320×109 m3), though some estimates have been as low as 1,500 billion barrels (240×109 m3), and as high as 2,400 billion barrels (380×109 m3).[5][179]

The EUR reported by the 2000 USGS survey of 2,300 billion barrels (370×109 m3) has been criticized for assuming a discovery trend over the next 20 years which would completely and dramatically reverse the observed trend of the past 40 years. Their 95% confidence EUR of 2,300 billion barrels (370×109 m3) assumed that discovery levels would stay steady, despite the fact that discovery levels have been falling steadily since the 1960s. That trend of falling discoveries has continued in the 7 years since the USGS made their assumption.[5]

Criticisms

Some do not agree with Peak Oil, at least as it has been presented by Matthew Simmons. The president of Royal Dutch Shell's US operations John Hofmeister, while agreeing that conventional oil production will soon start to decline, has criticized Simmons's analysis for being "overly focused on a single country: Saudi Arabia, the world's largest exporter and OPEC swing producer." He also points to the large reserves at the "US Outer Continental Shelf, which holds an estimated 100 billion barrels (16×109 m3) of oil and natural gas. As things stand, however, only 15 percent of those reserves are currently exploitable, a good part of that off the coasts of Louisiana, Alabama, Mississippi and Texas. Simmons is also off the mark, Hofmeister contends, because he excludes unconventional sources of oil such as the oil sands of Canada, where Shell is already active. The Canadian oil sands — a natural combination of sand, water and oil found largely in Alberta — is believed to contain one trillion barrels of oil. Another trillion barrels are also said to be trapped in rocks in Colorado, Utah and Wyoming,[180] but are in the form of oil shale. These particular reserves present major environmental, social, and economic obstacles to recovery.[181][182] Hofmeister also claims that if oil companies were allowed to drill more in the United States enough to produce another 2 million barrels per day (320×103 m3/d), oil and gas prices would not be as high as they are in the later part of the 2000 to 2010 decade. He thinks that high energy prices are causing social unrest similar to levels surrounding the Rodney King riots.[183]

In Fiction

One of the first novels set in a Peak-Oil crisis is Alex Scarrow's book - Last Light. The book portrays the collapse of the United Kingdom, as a result of a full-scale terrorist attack against several important key installations in the Middle-East. It follows the experiences of a family, a father trapped in Iraq, a mother far away from her children, a daughter and son fending for themselves, as the complete break-down of law and order causes looting, deaths and worse.

The Mad Max movies are based in a dystopian Australia, in which (Mad Max 2: The Road Warrior explains) the cause of the general social collapse was energy shortage, particularly oil.

See also

|

Prediction

Economics

|

Technology

Others

|

References

- ^ Gwyn Richard (2004-01-28). "Demand for Oil Outstripping Supply". Toronto Star.

- ^ a b "CERA says peak oil theory is faulty". Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA). 2006-11-14. Cite error: The named reference "energybulletin112006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d Deffeyes Kenneth S (2007-01-19). "Current Events - Join us as we watch the crisis unfolding". Princeton University: Beyond Oil. Cite error: The named reference "deffeyes012007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d McGreal Ryan (2007-10-22). "Yes, We're in Peak Oil Today". Raise the Hammer. Cite error: The named reference "mcgreal102007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k

Zittel Werner, Schindler Jorg (2007-10). "Crude Oil: The Supply Outlook" (PDF). Energy Watch Group.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Cite error: The named reference "ewg1007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e f Cohen Dave (October 31, 2007). "The Perfect Storm". ASPO-USA. Cite error: The named reference "cohen102007" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c

Rembrandt H.E.M. Koppelaar (2006-09). "World Production and Peaking Outlook" (PDF). Peak Oil Netherlands.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Cite error: The named reference "koppelaar092006" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Bruno Joe Bel (2008-03-08). "Oil Rally May Be Economy's Undoing". AP. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ a b "International Petroleum (Oil) Consumption Data". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 2007-12-20. Cite error: The named reference "eiaoilconsumption" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "World oil demand 'to rise by 37%'". BBC News. 2006-06-20.

- ^ "2007 International Energy Outlook: Petroleum and other liquid fuels". U.S. Energy Information Administration. May 2007.

- ^ Oil price 'may hit $200 a barrel', BBC News

- ^ China's Negative Economic Outlook

- ^ "China and India: A Rage for Oil". Business Week. 2005-08-25.

- ^ Joe Mcdonald (April 21, 2008). "Gas guzzlers a hit in China, where car sales are booming". Associated Press.

- ^ BP Statistical Review of Energy - 2008

- ^

"Annual Energy Report" (PDF). US Department of Energy. 2006-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Global Oil Consumption". U.S. Energy Information Administration. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ a b Wood John H, Long Gary R, Morehouse David F (2004-08-18). "Long-Term World Oil Supply Scenarios: The Future Is Neither as Bleak or Rosy as Some Assert". Energy Information Administration.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Cite error: The named reference "wood082004" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ "Asia's Thirst for Oil". Wall Street Journal. 2004-05-05.

- ^ "Domestic Demand for Refined Petroleum Products by Sector". U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ a b c

Duncan Richard C (2001). "The Peak of World Oil Production and the Road to the Olduvai Gorge". Population & Environment. 22 (5): pp. 503–522. doi:10.1023/A:1010793021451. ISSN (Print) 1573-7810 (Online) 0199-0039 (Print) 1573-7810 (Online).

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check|issn=value (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=,|laydate=,|laysource=, and|laysummary=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "RCDuncan2001" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b c d e

"Total Midyear Population for the World: 1950-2050". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2007-12-20..

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) Cite error: The named reference "censusworldpop" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Savinar Matt. "Are We 'Running Out'? I Thought There Was 40 Years of the Stuff Left". Life After the Oil Crash. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ Mieszkowski Katharine (2006-03-22). "The oil is going, the oil is going!". Salon.com. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ Albert A. Bartlett (2004-08-27). "Thoughts on Long-Term Energy Supplies: Scientists and the Silent Lie" (PDF). Physics Today. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ a b c d "Energy Information Administration - International Petroleum (Oil) Production Data". Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ "The World Factbook". CIA Factbook. 2008-03-20. Retrieved 2008-03-31.

- ^ "Table of World Oil Production 2006" (pdf). BP. Retrieved 2007-12-20.

- ^ How peak oil could lead to starvation

- ^ Peak Oil: the threat to our food security

- ^ Agriculture Meets Peak Oil

- ^ Peak Oil And Famine:Four Billion Deaths

- ^ (a list of over 20 published articles and books supporting this thesis can be found here in the section: "Food, Land, Water, and Population")

- ^ Eating Fossil Fuels

- ^ a b c "Price rise and new deep-water technology opened up offshore drilling". The Boston Globe. 2005-12-11. Cite error: The named reference "bostonglobe122005" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Oil industry report says demand to outpace crude oil production". International Herald Tribune. 2007-07-16.

- ^ http://www.og.dti.gov.uk/information/bb_updates/chapters/Table4_3.htm

- ^ a b c d e Maass Peter (August 21, 2005). "The Breaking Point". New York Times. Cite error: The named reference "nyt08212005" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ "Briefing: Exxon increases budget for oil exploration". Bloomberg. 2007-03-07.

- ^ "Shell plans huge spending increase". International Herald Tribune. 2005-12-14.

- ^ a b

Campbell CJ (2000-12). "Peak Oil] Presentation at the Technical University of Clausthal".

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) Cite error: The named reference "campbell1222000" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Top Oil Groups Fail to Recoup Exploration, James Boxell, New York Times, 2004-10-10

- ^ Forecast of Rising Oil Demand Challenges Tired Saudi Fields, Jeff Gerth, New York Times, February 24, 2004.

- ^ Carl Morsfeld "How Shell blew a hole in a 100-year reputation" 2004-10-10, The Times.

- ^ What lies beneath? June 16, 2008, Kuwait Times

- ^ Production figures from BP statistical report 2008

- ^ The Trade Environment Database. "The Economic and Environmental Impact of the Gulf War on Kuwait and the Persian Gulf". Retrieved 2007-11-18.

- ^ No Peaking: The Hubbert Humbug Guerrilla News Network, Tue, 23 May 2006. Accessed 11/16/07

- ^ a b "OPEC Follies - Breaking point". National Review. 2003-12-04. Cite error: The named reference "nationalreview122003" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Duarte Joe (2006-03-28). "Canadian Tar Sands: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly". RigZone.

- ^ "Environmental Challenges of Heavy Crude Oils". Batelle. 2003.

- ^ "Tar Sands: A brief overview".

- ^ Dyni, John R (2003), "Geology and resources of some world oil-shale deposits (Presented at Symposium on Oil Shale in Tallinn, Estonia, November 18-21, 2002)" (PDF), Oil Shale. A Scientific-Technical Journal, 20 (3), Estonian Academy Publishers: 193–252, ISSN 0208-189X, retrieved 2007-06-17

- ^ Strategic Significance of America’s Oil Shale Resource. Volume II Oil Shale Resources, Technology and Economics (PDF), Office of Deputy Assistant Secretary for Petroleum Reserves; Office of Naval Petroleum and Oil Shale Reserves; U.S. Department of Energy, 2004, retrieved 2007-06-23

- ^ Excluding Unconventional World Oil Reserves

- ^ Dusseault, Dr. Maurice (2002). "Emerging Technology for Economic Heavy Oil Development" (PDF). Alberta Department of Energy. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Alboudwarej; et al. (Summer 2006). "Highlighting Heavy Oil" (PDF). Oilfield Review. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Resource Investor - Energy - Oil Doomsday is Nigh, Tar Sands Not a Substitute

- ^ Söderbergh, B.; Robelius, F.; Aleklett, K. (2007). "A crash programme scenario for the Canadian oil sands industry" (PDF). Energy Policy. 35 (3). Elsevier: 1931–1947. doi:10.1016/j.enpol.2006.06.007. Retrieved 2008-06-17.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Weissman Jeffrey G, Kessler Richard V (1996-06-20). "Downhole heavy crude oil hydroprocessing". Applied Catalysis A: General. 140: 1. doi:10.1016/0926-860X(96)00003-8.

- ^

Fleming, David (2000). "After Oil". Prospect Magazine. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hoyos Carola (2007-02-18). "Study sees harmful hunt for extra oil". Financial Times.

- ^ Lemley Brad (2003-05-01). "Anything Into Oil". Discover magazine.

- ^ Lemley Brad (2006-04-02). "Anything Into Oil". Discover magazine.

- ^ a b "World Oil Supply and Demand" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2007-01-18.

- ^ "Peak Oil and Energy Resources".

- ^ McGreal Ryan (2006-04-29). "Peak Oil for Saudi Arabia?". Raise the Hammer.

- ^ Miller Matthew S (2007-03-09). "Ghawar Is Dead!". Energy Bulletin.

- ^ Cordahi James, Critchlow Andy (2005-11-09). "Kuwait Oil Field, World's Second Largest, 'Exhausted'". Bloomberg.

- ^ Carl Mortishead (2008-01-18). "World not running out of oil, say experts". Times Online.

- ^ http://www.peakoil.net/Aleklett/Review_CERA_report_20060808.doc

- ^ "Canales: Output will drop at Cantarell field". El Universal. 2006-02-10.

- ^ Höök, Mikael (2007). "The Cantarell Complex: The dying Mexican giant oil field" (PDF). The Svedberg Laboratory, Uppsala University, Sweden. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Arai Adriana (2006-08-01 (dead)). "Mexico's Largest Oil Field Output Falls to 4-Year Low".

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Unknown parameter|publsher=ignored (|publisher=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.opec.org/library/World%20Oil%20Outlook/pdf/WorldOilOutlook.pdf

- ^ OPEC Summit Roundup Production hike prospects fade as Abu Dhabi summit looms - Forbes.com

- ^ "Chevron Announces Record Setting Well Test at Jack". Chevron. 2006-09-05.

- ^ U.S. Oil Reserves Get a Big Boost - washingtonpost.com

- ^ Geyer Greg (2006-09-19). "Jack-2 Test Well Behind The Hype". Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas.

- ^ Official Energy Statistics from the U.S. Government, Energy Information Administration.

- ^ Mackey Peg, Lawler Alex (2008-01-09). "Tough to pump more oil, even at $100". Manchester Guardian. Reuters.

- ^ "Non-OPEC peak oil threat receding". Arabian Business. 2007-07-06.

- ^ McNulty Sheila (2007-05-09). "Politics of oil seen as threat to supplies". Financial Times.

- ^

Fox Justin (2007-05-31). "No More Gushers for ExxonMobil". Time magazine.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "Rejecting the Real 'Snake Oil'". Huffington Post. 2007-06-29.

- ^

Noel Grove, reporting M. King Hubbert (1974). "Oil, the Dwindling Treasure". National Geographic.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameters:|quotes=,|laydate=,|laysource=, and|laysummary=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^

"Light-Duty Automotive Technology and Fuel Economy Trends: 1975 Through 2006 - Executive Summary". EPA EPA420-S-06-003. 2006-07.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

Ferenc L. Toth, Hans-Holger Rogner, (2006). "Oil and nuclear power: Past, present, and future" (PDF). Energy Economics. 28 (1–25): pg. 3.

{{cite journal}}:|pages=has extra text (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Reserve Growth". USGS.

- ^ K., Aleklett (May 26–27, 2003). "Matthew Simmons Transcript". Proceedings of the 2nd International Workshop on Oil Depletion,. Paris, France: The Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. Retrieved 2008-05-24.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Macleod Scott (2002-02-25). "How to Bring Change to the Kingdom". Time.

- ^

"Newsletter" (PDF). Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. 2008-01.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^

"Newsletter" (PDF). Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas Ireland. 2008-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Boone Pickens Warns of Petroleum Production Peak". Association for the Study of Peak Oil and Gas. 2005-05-03.

- ^ Melvin Jasmin (2008-06-17). "World crude production has peaked: Pickens". Reuters.

- ^

"Medium-Term Oil Market Report". IEA. 2007-07.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Seager Ashley (2007-10-22). "Steep decline in oil production brings risk of war and unrest, says new study". The Guardian.

- ^ "Peak oil". 2006-10-28.

- ^ "One energy forecast: Oil supplies grow". Christian Science Monitor. 2005-06-22.

- ^ "World Oil Consumption by region, Reference Case" (PDF). EIA. 2006.

- ^ "Oil expert: US overestimates future oil supplies". Channel 4 News.

- ^ "Campbell replies to USGS: Global Petroleum Reserves - A View to the Future". Oil Crisis. 2002-12-01.

- ^ a b Mouawad, Jad (2007-03-05). "Oil Innovations Pump New Life Into Old Wells". New York Times.

- ^ Lynch Michael C (2004). "The New Pessimism about Petroleum Resources: Debunking the Hubbert Model (and Hubbert Modelers)" (PDF). American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2004.

- ^ "Aramco chief says world's Oil reserves will last for more than a century". Oil and Gas Journal.

- ^ Jum’ah Abdallah S. "Rising to the Challenge: Securing the Energy Future". World Energy Source.

- ^ Nyquist JR (2006-05-08). "Debunking Peak Oil". Financial Sense.

- ^ Science Magazine, Abiogenic Hydrocarbon Production at Lost City Hydrothermal Field February 2008

- ^ Mello MR, Moldowan JM (2005). "Petroleum: To Be Or Not To Be Abiogenic". searchanddiscovery.net.

- ^ T. Gold: Proceedings of National Academy of Science http://www.pnas.org/cgi/reprint/89/13/6045

- ^ Microsoft Word - NETL Final Report, 2-05.doc

- ^ A list of publications supporting this thesis can be found here in the section: "Food, Land, Water, and Population."

- ^ Record rise in wheat price prompts UN official to warn that surge in food prices may trigger social unrest in developing countries

- ^ Rising food prices curb aid to global poor

- ^ Record rise in wheat price prompts UN official to warn that surge in food prices may trigger social unrest in developing countries

- ^ Keith Bradsher (January 19, 2008). "A New, Global Oil Quandary: Costly Fuel Means Costly Calories". New York Times.

- ^ 2008: The year of global food crisis

- ^ The global grain bubble

- ^ The cost of food: Facts and figures

- ^ The World's Growing Food-Price Crisis

- ^ Already we have riots, hoarding, panic: the sign of things to come?

- ^ Riots and hunger feared as demand for grain sends food costs soaring

- ^ Feed the world? We are fighting a losing battle, UN admits

- ^ Raw Material Reserves - International Fertilizer Industry Association [1]

- ^ Integrated Crop Management-Iowa State University January 29, 2001 [2]

- ^ The Hydrogen Economy-Physics Today Magazine, December 2004 [3]

- ^ Realities of organic farming

- ^ http://extension.agron.iastate.edu/organicag/researchreports/nk01ltar.pdf

- ^ Organic Farming can Feed The World!

- ^ Organic Farms Use Less Energy And Water

- ^ Strochlic, R.; Sierra, L. (2007). Conventional, Mixed, and “Deregistered” Organic Farmers: Entry Barriers and Reasons for Exiting Organic Production in California. California Institute for Rural Studies.

- ^ Srinivas; et al. (June, 2008). "Reviewing The Methodologies For Sustainable Living". 7. The Electronic Journal of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Chemistry: 2993–3014.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help); Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Conway, G. (2000). "Genetically modified crops: risks and promise". 4(1): 2. Conservation Ecology.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ . R. Pillarisetti and Kylie Radel (June 2004). "Economic and Environmental Issues in International Trade and Production of Genetically Modified Foods and Crops and the WTO". Volume 19, Number 2. Journal of Economic Integration: 332–352.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Juan Lopez Villar & Bill Freese (January 2008). "Who Benefits from GM Crops?" (pdf). Friends of the Earth International.

- ^ "Monsanto's showcase project in Africa fails". Vol 181 No. 2433. New Scientist. 7 February 2004. Retrieved 2008-04-18.

{{cite journal}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Devlin Kuyek (August 2002). "Genetically Modified Crops in Africa: Implications for Small Farmers" (pdf). Genetic Resources Action International (GRAIN).

- ^ Jeremy Cooke (30 May 2008). "Genetically Modified Crops in Africa: Implications for Small Farmers". BBC. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ^ Kunstler, James Howard (1994). Geography Of Nowhere: The Rise And Decline of America's Man-Made Landscape. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-88825-0

- ^ James Howard Kunstler (February 2004). The tragedy of suburbia. Monterey, CA: TED: Ideas worth sharing.

- ^ Robert L. Hirsch, Roger Bezdek, Robert Wendling, "Peaking of world oil production: impacts, mitigation, & risk management" February 2005

- ^ {{cite web| |url=http://www.beyondpeak.com/scenarios/winners.html |publisher=Mick Winter (ed.) |title=Winners: First Annual Beyond Peak Scenario Contest |date=2006

- ^ Hansen, J. (2007). "Dangerous Human-Made Interference with Climate" (PDF). Testimony to Select Committee on Energy Independence and Global Warming, United States House of Representatives. 26. Retrieved 2008-07-02.

- ^ Jensen, Derrick (2006). Endgame, Volume 1: The Problem of Civilization. New York City: Seven Stories Press. ISBN 978-1-58322-730-5.

- ^ WorldWatch Institute (2005-01-01). State of the World 2005: Redefining Global Security. New York: Norton. p. 107. ISBN 0-393-32666-7.

- ^ Unless otherwise specified, source is ABC TV's Four Corners.

- ^ http://www.eia.doe.gov/emeu/aer/txt/stb0501.xls

- ^ Trinidad and Tobago Crude Oil Production by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)

- ^ Egypt Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)

- ^ "Oil price hits $113. 93 a barrel". BBC News. 2008-04-15.

- ^ Aram Mäkivierikko (2007-10-01). Russian Oil - a Depletion Rate Model estimate of the future Russian oil production and export (PDF). Uppsala University.

- ^ Indonesia Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)

- ^ Syrian Arab Republic Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)

- ^ New Zealand Crude Oil Production by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)

- ^ Helge Lund: - «Peak Oil» har kommet til Norge (Olje , Statoil)

- ^ Oman Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year (Thousand Barrels per Day)

- ^ Four Corners Broadband Edition: Peak Oil

- ^

"Richard Heinberg's Museletter- Peak Everything". Post Carbon Institute. 2007-9-3.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ Ana Campoy (June 20, 2008). "Prices Curtail U.S. Gasoline Use". Wall Street Journal. p. A4.

- ^ Clifford Krauss (June 19, 2008). "Driving Less, Americans Finally React to Sting of Gas Prices, a Study Says". New York Times.

- ^ "What is driving oil prices so high?". BBC News. 2007-11-05.

- ^ Bruno Joe Bel (2008-03-08). "Oil Rally May Be Economy's Undoing". AP. Retrieved 2008-03-08.

- ^ Langfitt Frank (2008-03-05). "Americans Using Less Gasoline". National Public Radio.

- ^ Lavelle Marianne (2008-03-04). "Oil Demand Is Dropping, but Prices Aren't". U.S. News & World Report.

- ^ John Wilen (2008-04-21). "Oil prices pass $132 after government reports supply drop". Associated Press.

- ^ Gold Russell, Davis Ann (2007-11-10). "Oil Officials See Limit Looming on Production". Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Global oil prices jump to 11-month highs". Petroleum World. 2007-07-09.

- ^ "Oil prices rally despite OPEC output hike". MSNBC. 2005-06-15.

- ^ "Oil Market Report - Demand" (PDF). International Energy Agency. 2006-07-12.

- ^ "Global oil prices jump to 11-month highs". Petroleum World. 2007-07-09.

- ^ Missile tension sends oil surging

- ^ Oil hits $100 barrel, BBC News

- ^ Iran nuclear fears fuel oil price, BBC News

- ^ "Record oil price sets the scene for $200 next year". AME. July 6 2006. Retrieved 2007-11-29.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "World Consumption of Primary Energy by Energy Type and Selected Country Groups, 1980-2004" (XLS). Energy Information Administration, U.S. Department of Energy. 2006-07-31. Retrieved 2007-01-20.

- ^ James Kanter (2007-11-09). "European politicians wrestle with high gasoline prices". International Herald Tribune.