Humanism

| Part of a series on |

| Humanism |

|---|

|

| Philosophy portal |

Humanism is a broad category of ethical philosophies that focuses on universal human qualities, particularly rationality, rather than the supernatural or the authority of religious texts. Humanism affirms the worth and dignity of all people. There is another meaning of humanism that refers to Marx's basis for communism. This article is about humanism as a philosophy or life stance, which is the predominant and most recognized meaning of the term in use today, especially in the Anglophone world, although the second meaning is also widely used.[1] Modern humanism inherits the Anti-clericalism of eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosophes and holds that knowledge and virtue can be attained through human reason unaided by appeals to authority or the supernatural. It also tends to strongly endorse human rights, including reproductive rights and gender equality, and the separation of church and state. The term covers organized non-theistic religions, secular humanism, and a humanistic life stance.[citation needed]

Aspects of modern humanism

Religion

Members of humanist organizations disagree among themselves as to whether humanism is a religion or not, categorizing themselves in one of three ways: religious humanists, in the tradition of the earliest humanist organizations in the UK and US, saw humanism as fulfilling the traditional social role of religion. Secular humanists consider all forms of religion, including religious humanism, to be superseded. In order to sidestep disagreements between these two factions recent humanist proclamations define humanism as a life stance. See Humanism (life stance). Regardless of implementation, the philosophy of all three groups rejects deference to supernatural beliefs. It is generally compatible with atheism[2] and agnosticism[3] but being atheist or agnostic does not make one a humanist.[4] There is no one ideology or set of behaviors to which all atheists adhere, and not all are humanistic. In a number of countries the humanist life stance has become legally recognized as equivalent to a religion, so that members of humanist organizations may qualify for equal protection under the law.[5] In the United States, the Supreme Court recognized that humanism is equivalent to a religion in the limited sense of authorizing humanists to conduct ceremonies commonly carried out by officers of religious bodies. The relevant passage is in a footnote to Torcaso v. Watkins (1961).

Knowledge

Modern philosophical humanism holds that it is up to humans to seek for truth through reason and observable evidence. This view supports scientific skepticism and the scientific method. However, this view supports personal faith in human nature as a suitable basis for moral action. Likewise, humanism asserts that knowledge of right and wrong is based on the best understanding of the individual and common good.[6]

Optimism

Philosophical humanism features a qualified Optimism about the capacity of people, but it does not involve believing that human nature is purely good or that all people can live up to the humanist ideals without help. If anything, there is the recognition that living up to one's potential is hard work and requires the assistance of others. The ultimate goal is human flourishing; making life better for all humans, and as the most conscious species, also promoting concern for the welfare of other sentient beings and the planet as a whole. The focus is on doing good and living well in the here and now, and leaving the world a better place for those who come after.

History

The term "humanism" is ambiguous. Around 1806 humanismus was used to describe the classical curriculum offered by German schools, and by 1936 "humanisim" was borrowed into English in this sense. In 1856, the great German historian and philologist Georg Voigt used humanism to describe Renaissance Humanism, the movement that flourished in the Italian Renaissance to revive classical learning, a use which won wide acceptance among historians in many nations, especially Italy.[7] This historical and literary use of the word "humanist" derives from the 15th century Italian term umanista, meaning a teacher or scholar of Classical Greek and Latin literature and the ethical philosophy behind it.

In the mid-eighteenth century, however, a different use of the term "humanism" began to emerge. In 1765, the author of an anonymous article in a French Enlightenment periodical spoke of "The general love of humanity . . . a virtue hitherto quite nameless among us, and which we will venture to call ‘humanism’, for the time has come to create a word for such a beautiful and necessary thing.”[8] After the French Revolution the idea that human virtue could be created by human reason alone independently from traditional religious institutions, attributed by opponents of the Revolution to Enlightenment philosophes such as Rousseau, was violently attacked by influential religious and political conservatives, such as Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, as a deification or idolatry of man.[9] Humanism began to acquire a negative sense. The Oxford English Dictionary records the use of the word "humanism" by an English clergyman in 1812 to indicate those who believe in the "mere humanity" (as opposed to the divine nature) of Christ, i.e., Unitarians and Deists.[10] In this polarized atmosphere, political and religious reformers and radicals defiantly embraced the idea of humanism as a new and positive religion of humanity. The anarchist Proudhon (best known for declaring that "property is theft") used the word humanism to describe a "culte, déification de l’humanité" ("cult, deification of humanity") and Ernest Renan in L’avenir de la science: pensées de 1848 (The Future of Knowledge: Thoughts on 1848") (1848-49), states: "It is my deep conviction that pure humanism will be the religion of the future, that is, the cult of all that pertains to man—all of life, sanctified and raised to the level of a moral value.“ [11] At about the same time the word humanism as a philosophy centered around man (as opposed to institutionalized religion) was also being used in Germany by the so-called Left Hegelians, Arnold Ruge, and Karl Marx, who were critical of the close involvement of the church in the repressive German government. There has been a persistent confusion between the several uses of the terms[12]: philosophical humanists look to human-centered antecedents among the Greek philosophers and the great figures of Renaissance history, often assuming somewhat inaccurately that famous historical humanists and champions of human reason had uniformly shared their militantly anti-theistic stance.

Greek humanism

Sixth century BCE pantheists Thales of Miletus and Xenophanes of Colophon prepared the way for later Greek humanist thought. Thales is credited with creating the maxim "Know thyself", and Xenophanes refused to recognize the gods of his time and reserved the divine for the principle of unity in the universe. Later Anaxagoras, often described as the "first freethinker", contributed to the development of science as a method of understanding the universe. These Ionian Greeks were the first thinkers to recognize that nature is available to be studied separately from any alleged supernatural realm. Pericles, a pupil of Anaxagoras, influenced the development of democracy, freedom of thought, and the exposure of superstitions. Although little of their work survives, Protagoras and Democritus both espoused agnosticism and a spiritual morality not based on the supernatural. The historian Thucydides is noted for his scientific and rational approach to history.[13] In the third century BCE, Epicurus became known for his concise phrasing of the problem of evil, lack of belief in the afterlife, and human-centered approaches to achieving eudaimonia. He was also the first Greek philosopher to admit women to his school as a rule.

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was an intellectual movement in Europe of the later Middle Ages and the Early Modern period. It was the nineteenth century German historian Georg Voigt who identified Petrarch as the first Renaissance humanist. Paul Johnson agrees that Petrarch was "the first to put into words the notion that the centuries between the fall of Rome and the present had been the age of Darkness.” According to Petrarch, what was needed was the careful study and imitation of the great classical authors. For Petrarch and Boccaccio the greatest master was Cicero, whose prose became the model for both learned (Latin) and vernacular (Italian) prose.

Once the language was mastered grammatically it could be used to attain the second stage, eloquence or rhetoric. This art of persuasion [Cicero had held] was not art for its own sake, but the acquisition of the capacity to persuade others — all men and women — to lead the good life. As Petrarch put it, 'it is better to will the good than to know the truth.' Rhetoric thus led to and embraced philosophy. Leonardo Bruni (c.1369-1444), the outstanding scholar of the new generation, insisted that it was Petrarch who “opened the way for us to show how to acquire learning", but it was in Bruni’s time that the word umanista first came into use, and its subjects of study were listed as five: grammar, rhetoric, poetry, moral philosophy, and history.”[14]

The basic training of the humanist was to speak well and write (typically, in the form of a letter). One of Petrarch’s followers, Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406) was made chancellor of Florence, "whose interests he defended with his literary skill. The Visconti of Milan claimed that Salutati’s pen had done more damage than 'thirty squadrons of Florentine cavalry.'”[15]

Contrary to popular misconception, however, Renaissance humanism was not a philosophical movement, neither was it anti-religious. A modern historian has this to say:

Humanism was not an ideological programme but a body of literary knowledge and linguistic skill based on the “revival of good letters”, which was a revival of a late-antique philology and grammar, This is how the word “humanist" was understood by contemporaries, and if scholars would agree to accept the word in this sense rather than in the sense in which it was used in the nineteenth century we might be spared a good deal of useless argument. That humanism had profound social and even political consequences of the life of Italian courts is not to be doubted. But the idea that as a movement it was in some way inimical to the Church, or to the conservative social order in general is one that has been put forward for a century and more without any substantial proof being offered.

The nineteenth-century historian Jacob Burckhardt, in his classic work, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, noted as a “curious fact” that some men of the new culture were “men of the strictest piety, or even ascetics.” If he had meditated more deeply on the meaning of the careers of such humanists as Abrogio Traversari (1386-1439), the General of the Camaldolese Order, perhaps he would not have gone on to describe humanism in unqualified terms as “pagan”, and thus helped precipitate a century of infertile debate about the possible existence of something called “Christian humanism” which ought to be opposed to “pagan humanism”. --Peter Partner, Renaissance Rome, Portrait of a Society 1500-1559 (University of California Press 1979) pp. 14-15.

The umanisti criticized what they considered the barbarous Latin of the universities, but the revival of the humanities largely did not conflict with the teaching of traditional university subjects, which went on as before. [16]

Nor did the humanists view themselves as in conflict with Christianity. Some, like Salutati, were the Chancellors of Italian cities, but the majority (including Petrarch) were ordained as priests and many worked as senior officials of the Papal court. Humanist Renaissance popes Nicholas V, Pius II, Sixtus IV, and Leo X wrote books and amassed huge libraries. [17][18] [19]

The educational curriculum and methods of the humanists:

were followed everywhere, serving as models for the Protestant Reformers as well as the Jesuits. The humanistic school, animated by the idea that the study of classical languages and literature provided valuable information and intellectual discipline as well as moral standards and a civilized taste for future rulers, leaders, and professionals of its society, flourished without interruption, through many significant changes, until our own century, surviving many religious, political and social revolutions. It has but recently been replaced, though not yet completely, by other more practical and less demanding forms of education.Cite error: There are

<ref>tags on this page without content in them (see the help page).P.O. Kristeller (op cit.), p. 114.

Back to the sources

The humanists' close study of Latin literary texts soon enabled them to discern historical differences in the writing styles of different periods. By analogy with the perceived decline of Latin, they applied the principle of ad fontes, or back to the sources, across broad areas of learning, seeking out manuscripts of Patristic literature as well as pagan authors.

Erasmus and Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples became notable for their editions and translations of Biblical texts from the Greek, laying the groundwork for the Protestant Reformation. The historian of the Renaissance Sir John Hale emphasizes that though such a programme was secular, "concerned with man, his nature and gifts," nevertheless, he writes,

Renaissance humanism must be kept free from any hint of either 'humanitarianism' or 'humanism' in its modern sense of rational, non-religious approach to life. ... Unless the word 'humanism' retains the smell of the scholar's lamp it will mislead - as it will if it is seen in opposition to a Christianity, [which] its students in the main wished to supplement, not contradict, through their patient excavation of the sources of ancient, God-inspired wisdom.[20]

The rediscovery of ancient literary and other cultural texts enabled a closer acquaintance with and thus the revival of the philosophy, art and poetry of classical antiquity.

Consquences of the Renaissance humanist movement

The ad fontes principle of the humanists had many applications. Humanist learning revived knowledge of pagan philosophical schools such as neo-stoicism, epicureanism, and neo-Platonism (which dated from late antiquity, though they believed it to be more ancient), considering the pagan virtues extolled by these schools as perfectly compatible with Christianity and as equally derived from divine revelation ([21] M. A. Screech writes that "Renaissance humanists rejoiced in the mutual compatibility of much ancient philosophy and Christian truths."[22] The line from a drama of Terence, Homo sum, humani nihil a me alienum puto (or with nil for nihil), meaning "I am a man [i.e. human, not 'male'], I think nothing human alien to me", was taken both at the time, and even more in later centuries, to be one such proposition, and an encapsulation of a humanist philosophy.

According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "Enlightenment thinkers remembered Erasmus (not quite accurately) as a precursor of modern intellectual freedom and a foe of both Protestant and Catholic dogmatism."[23] Humanistic education sometimes, certainly, resulted in intellectual freedom, and humanists asserted an independence from the authority of the Church in various ways[24]: Gemistus Pletho taught a Christianized version of pagan polytheism;[25] Niccolò Machiavelli and Francesco Guicciardini endorsed a secular political worldview; Michel Montaigne and Francis Bacon made skepticism a theme of their essays; and François Rabelais wrote satires on scholastic targets, such as the Sorbonne theologians and Galen.[26] The syncretism of Renaissance Neo-Platonism and Hermeticism, arising with Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, and developed by later thinkers such as Giordano Bruno and Tommaso Campanella, introduced new and ambitious ideas of supernatural forces.[27] The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy describes the classical writings as having a fundamental impact on Renaissance scholars:

Here, one felt no weight of the supernatural pressing on the human mind, demanding homage and allegiance. Humanity—with all its distinct capabilities, talents, worries, problems, possibilities—was the center of interest. It has been said that medieval thinkers philosophized on their knees, but, bolstered by the new studies, they dared to stand up and to rise to full stature.[28]

Better acquaintance with Greek and Roman writers was also an ingredient of the history of science in the Renaissance. This was despite a Platonist element that opposed the Aristotelian concentration on the observable properties of the physical world, and what A. C. Crombie calls "a backwards-looking admiration for antiquity" that had to be supplemented by more than literary interests.[29]

Cicero and Seneca opened the door for the humanists to the non-Aristotelian dogmatists, the Stoics and Epicureans, and to the sceptical philosophers (including Plato on Cicero's account) who used the arguments of the different dogmatists against each other.[30]

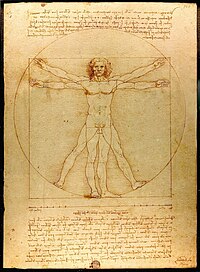

Just as artist and inventor Leonardo da Vinci advocated study of human anatomy, nature, and weather to improve Renaissance works of art, so did Spanish humanist Juan Luis Vives advocate observation, craft, and practical techniques to improve philosophy.[31] Thus natural philosophy evolved, coming to include not only ancient literary works, but empirical observations and experimentation in the observable universe, which laid the groundwork for later scientific inquiry.[32]

Secular Humanism

The Humanistic Religious Association was formed as one of the earliest forerunners of contemporary chartered humanist organizations in 1853 in London. This early group was democratically organized, with male and female members participating in the election of the leadership and promoted knowledge of the sciences, philosophy, and the arts.[33]

In February 1877, the word was used, apparently for the first time in America, to describe Felix Adler, pejoratively. Adler, however, did not embrace the term, and instead coined the name "Ethical Culture" for his new movement– a movement which still exists in the now Humanist-affiliated New York Society for Ethical Culture.[34] In 2008, Ethical Culture Leaders wrote "Today, the historic identification, Ethical Culture, and the modern description, Ethical Humanism, are used interchangeably."[35]

Active in the early 1920s, F.C.S. Schiller labeled his work "humanism" but for Schiller the term referred to the pragmatist philosophy he shared with William James. In 1929 Charles Francis Potter founded the First Humanist Society of New York whose advisory board included Julian Huxley, John Dewey, Albert Einstein and Thomas Mann. Potter was a minister from the Unitarian tradition and in 1930 he and his wife, Clara Cook Potter, published Humanism: A New Religion. Throughout the 1930s Potter was a well-known advocate of women’s rights, access to birth control, "civil divorce laws", and an end to capital punishment.[36]

Raymond B. Bragg, the associate editor of The New Humanist, sought to consolidate the input of L. M. Birkhead, Charles Francis Potter, and several members of the Western Unitarian Conference. Bragg asked Roy Wood Sellars to draft a document based on this information which resulted in the publication of the Humanist Manifesto in 1933. Potter's book and the Manifesto became the cornerstones of modern humanism, the latter declaring a new religion by saying, "any religion that can hope to be a synthesizing and dynamic force for today must be shaped for the needs of this age. To establish such a religion is a major necessity of the present." It then presented fifteen theses of humanism as foundational principles for this new religion.

In 1941 the American Humanist Association was organized. Noted members of The AHA included Isaac Asimov, who was the president from 1985 until his death in 1992, and writer Kurt Vonnegut, who followed as honorary president until his death in 2007. Robert Buckman was the head of the association in Canada, and is now an honorary president.[citation needed]

After World War II, three prominent humanists became the first directors of major divisions of the United Nations: Julian Huxley of UNESCO, Brock Chisholm of the World Health Organization, and John Boyd-Orr of the Food and Agricultural Organization.[37]

Humanism (life stance)

Humanism (capital 'H', no adjective such as "secular")[38] is a comprehensive life stance that upholds human reason, ethics, and justice, and rejects supernaturalism, pseudoscience, and superstition.

The International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU) is the world union of more than one hundred Humanist, rationalist, secular, ethical culture, and freethought organizations in more than 40 countries. The Happy Human is the official symbol of the IHEU as well as being regarded as a universally recognised symbol for those that call themselves Humanists (as opposed to "humanists"). In 2002 the IHEU General Assembly unanimously adopted the Amsterdam Declaration 2002 which represents the official defining statement of World Humanism.[39]

All member organisations of the IHEU are required by IHEU bylaw 5.1[40] to accept the IHEU Minimum Statement on Humanism:

Humanism is a democratic and ethical life stance, which affirms that human beings have the right and responsibility to give meaning and shape to their own lives. It stands for the building of a more humane society through an ethic based on human and other natural values in the spirit of reason and free inquiry through human capabilities. It is not theistic, and it does not accept supernatural views of reality.

Other forms of humanism

Humanism is also sometimes used to describe humanities scholars (particularly scholars of the Greco-Roman classics). As mentioned above, it is sometimes used to mean humanitarianism. There is also a school of humanistic psychology, and an educational method.[citation needed]

Educational humanism

Humanism, as a current in education, began to dominate U.S. school systems in the 17th century. It held that the studies that develop human intellect are those that make humans "most truly human". The practical basis for this was faculty psychology, or the belief in distinct intellectual faculties, such as the analytical, the mathematical, the linguistic, etc. Strengthening one faculty was believed to benefit other faculties as well (transfer of training). A key player in the late 19th-century educational humanism was U.S. Commissioner of Education William Torrey Harris, whose "Five Windows of the Soul" (mathematics, geography, history, grammar, and literature/art) were believed especially appropriate for "development of the faculties". Educational humanists believe that "the best studies, for the best kids" are "the best studies" for all kids.[citation needed] While humanism as an educational current was widely supplanted in the United States by the innovations of the early 20th century, it still holds out in some preparatory schools and some high school disciplines (especially in literature).[citation needed]

Collective Humanism

Humanism is increasingly coming to designate a sensibility for our species, planet and lives as a collective philosophy. While retaining the definition of the IHEU with regard to the life stance of the individual, collective Humanism utilizes a numerical modifier to distinguish itself as a broadening awareness within homo sapiens of our powers and obligations. It is distinctive in that it presumes an advocacy role for Humanism towards species governance and this proactive stance is charged with a commensurate responsibility compared to individual Humanism. It identifies pollution, militarism, nationalism, sexism, poverty and corruption as being persistent and addressable human character issues incompatible with the interests of our species. Collective Humanism asserts that species governance must be centralized within a world government and is inclusionary, in that it does not exclude any Human from its membership by reason of their collateral beliefs or possible religion alone. As such it can be said to be an envelope for variants of Humanism that address particular viewpoints,carrying forward a "human community" superset of ethics that complement the personal tenets of individuals.[41]

See also

Manifestos and statements setting out Humanist viewpoints

Related philosophies

- Agnosticism

- Atheism

- Confucianism

- Deism

- Existentialism

- Eudaimonism

- Eupraxsophy

- Extropianism

- Human potential movement

- Infinitism

- Marxist humanism

- Materialism

- New Age Spirituality

- Objectivity

- Positivism

- Pragmatism

- Permaculture

- Rationalism

- Selfism

- Skepticism

- Transhumanism

- Ubuntu (philosophy)

- Yekishim

Organizations

- American Humanist Association

- British Humanist Association

- Humanist Association of Canada

- City Congregation for Humanistic Judaism

- Council for Secular Humanism

- Ethical Culture

- European Humanist Federation

- Humanist Association of Ireland

- Humanisterna, the Swedish Humanist Association

- Human-Etisk Forbund, the Norwegian Humanist Association

- Humanist International

- Humanist Movement

- Humanist Society of Scotland

- Institute for Humanist Studies

- International Humanist and Ethical Union (IHEU)

- North East Humanists, the largest regional Humanist group in the United Kingdom

- Rationalist International

- Sidmennt, the Icelandic Ethical Humanist Association

- Society for Humanistic Judaism

Other

- Antihumanism

- Community organizing

- Humanistic psychology

- Misanthropy

- Social psychology

- Speciesism

- Ten Commandment Alternatives - Secular and humanist alternatives to the Ten Commandments

References

Notes

- ^ Compact Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 2007.

humanism n. 1 a rationalistic system of thought attaching prime importance to human rather than divine or supernatural matters. 2 a Renaissance cultural movement that turned away from medieval scholastic-ism and revived interest in ancient Greek and Roman thought.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|publicationyear=ignored (help) Typically, abridgments of this definition omit all senses except #1, such as in the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary, Collins Essential English Dictionary, and Webster's Concise Dictionary. New York: RHR Press. 2001. p. 177. - ^

Baggini, Julian (2003). Atheism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 3–4. ISBN 0-19-280424-3.

The atheist's rejection of belief in God is usually accompanied by a broader rejection of any supernatural or transcendental reality. For example, an atheist does not usually believe in the existence of immortal souls, life after death, ghosts, or supernatural powers. Although strictly speaking an atheist could believe in any of these things and still remain an atheist... the arguments and ideas that sustain atheism tend naturally to rule out other beliefs in the supernatural or transcendental.

- ^

Winston, Robert (Ed.) (2004). Human. New York: DK Publishing, Inc. p. 299. ISBN 0-7566-1901-7.

Neither atheism nor agnosticism is a full belief system, because they have no fundamental philosophy or lifestyle requirements. These forms of thought are simply the absence of belief in, or denial of, the existence of deities.

- ^ Although the words "ignostic" (American) or "indifferentist" (English, including OED) are sometimes applied to Humanism [citation needed], on the grounds that Humanism is an ethical process, not a theistic dogma, many humanists are deeply concerned about the impact of religion and belief in a god or gods on society and their own freedoms. Agnosticism or atheism do not necessarily entail humanism; many different and sometimes incompatible philosophies happen to be atheistic in nature[citation needed]

- ^ Note: The topic of this article has a small initial character as Wikipedia guidelines prescribe for the name of a philosophy. The life stance named Humanism is capitalized as prescribed for the name of a religion in its dedicated article, but left lower-case in this one to encompass life-stance, religious, and secular humanism.

- ^

Lamont, Corliss (1997). The Philosophy of Humanism, Eighth Edition. Humanist Press: Amherst, New York. pp. 252–253. ISBN 0-931779-07-3.

Conscience, the sense of right and wrong and the insistent call of one's better, more idealistic, more social-minded self, is a social product. Feelings of right and wrong that at first have their locus within the family gradually develop into a pattern for the tribe or city, then spread to the larger unit of the nation, and finally from the nation to humanity as a whole. Humanism sees no need for resorting to supernatural explanations, or sanctions at any point in the ethical process.

- ^ As J. A. Symonds remarked, “the word humanism has a German sound and is in fact modern” (See The Renaissance in Italy Vol. 2:71n, 1877). Vito Giustiniani writes that in the German-speaking world “Humanist” while keeping its specific meaning (as scholar of Classical literature) “gave birth to further derivatives, such as humanistisch for those schools which later were to be called humanistische gymnasien, with Latin and Greek as the main subjects of teaching (1784). Finally, Humanismus was introduced to denote ‘classical education in general' (1808) and still later for the epoch and the achievements of the Italian humanists of the fifteenth century (1841). This is to say that ‘humanism’ for ‘classical learning‘ appeared first in Germany, where it was once and for all sanctioned in this meaning by Georg Voigt (1859)", Vito Giustiniani, "Homo, Humanus, and the Meanings of Humanism", Journal of the History of Ideas 46 (vol. 2, April-June, 1985): 172.

- ^ “L’amour général de l’humanité . . . vertu qui n’a point de nom parmi nous et que nous oserions appler ‘humanisme’, puisque’enfin il est temps de créer un mot pour une chose si belle et nécessaire"; from the review Ephémérides du citoyen ou Bibliothèque raisonée des sciences morales et politiques, (Jan. 16, 1765): 247, quoted in V. Giustiniani, op. cit., p. 175n.

- ^ Although Rousseau himself devoutly believed in a personal God, his book, Emile: or, On Education, does attempt to demonstrate that atheists can be virtuous. It was publicly burned. During the Revolution Jacobins instituted a cult of the Supreme Being along lines suggested by Rousseau. In the nineteenth century French Positivist philosopher Auguste Comte (1798–1857) founded a "religion of humanity", whose calender and catechism echoed the former Revolutionary cult. See Comtism

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary. Vol. VII (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. 1989. pp. 474–475.

- ^ "Ma conviction intime est que la religion de l’avenir sera le pur humanisme, c’est-à-dire le culte de tout ce qui est de l’homme, la vie entière santifiée et éléve a une valeur moral.”, quoted in Giustiniani, op. cit.

- ^ An account of the evolution of the meaning of the word humanism from the point of view of a modern philosophical humanist can be found in Nicolas Walter's Humanism– What's in the Word.Walter, Nicolas, 1997 Humanism– What's in the Word, Rationalist Press Association, London, ISBN 0-301-97001-7.

- ^ Potter, Charles (1930). Humanism A new Religion. Simon and Schuster. pp. 64–69.

- ^ Johnson, Paul (2000). The Renaissance. New York: The Modern Library. pp. 32–34 and 37. ISBN 0-679-64086-X.

- ^ Johnson, Paul (2000). The Renaissance. New York: The Modern Library. p. 37.

- ^ "The term umanista was associated with the revival of the studia humanitatis "which included grammatica, rhetorica, poetics, historia , and philosophia moralis, as these terms were understood. Unlike the liberal arts of the eighteenth century, they did not include the visual arts, music, dancing or gardening. The humanities also failed to include the disciplines that were the chief subjects of instruction at the universities during the Later Middle Ages and throughout the Renaissance, such as theology, jurisprudence, and medicine, and the philosophical disciplines other than ethics, such as logic, natural philosophy, and metaphysics. In other words humanism does not represent, as often believed, the sum total of Renaissance thought and learning, but only a well-defined sector of it. Humanism has its proper domain or home territory in the humanities, whereas all other areas of learning, including philosophy (apart from ethics), followed their own course, largely determined by their medieval tradition and by their steady transformation through new observations, problems, or theories. These disciplines were affected by humanism mainly from the outside and in an indirect way, though often quite strongly."Paul Oskar Kristeller, Humanism, pp. 113-114, in Charles B. Schmitt, Quentin Skinner (editors), The Cambridge History of Renaissance Philosophy (1990).

- ^ Löffler, Klemens (1910). "Humanism". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. VII. New York: Robert Appleton Company. pp. 538–542.

- ^ Origo, Iris; in Plumb, pp. 209ff. See also their respective entries in Hale, 1981

- ^ Davies, 477

- ^ Hale, 171. See also Davies, 479-480 for similar caution.

- ^ "Humanism". Encyclopedic Dictionary of Religion. Vol. F–N. Corpus Publications. 1979. p. 1733. ISBN 0-9602572-1-7.

- ^ M. A. Screech, Laughter at the Foot of the Cross (1997), p. 13.

- ^ http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/erasmus/

- ^ Bergin, Thomas; Speake, Jennifer (1987). The Encyclopedia of the Renaissance. Oxford: Facts On File Publications. pp. 216–217.

- ^ Richard H. Popkin (editor), The Columbia History of Western Philosophy (1998), p. 293 and p. 301.

- ^ Kreis, Steven (2008). "Renaissance Humanism". Retrieved 2009-03-03.

- ^ Plumb, 95

- ^ ""Humanism"". "The Cambridge Dictionary of Philosophy, Second Edition. Cambridge University Press. 1999.

- ^ A. C. Crombie, Historians and the Scientific Revolution, p. 456 in Science, Art and Nature in Medieval and Modern Thought (1996).

- ^ Daniel Garber, Michael Ayers (editors), The Cambridge History of Seventeenth-century Philosophy (2003), p. 44.

- ^ Gottlieb, Anthony (2000). The Dream of Reason: a history of western philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 410–411.

- ^ Alleby, Brad (2003). "Humanism". Encyclopedia of Science & Religion. Vol. 1 (2nd ed.). Macmillan Reference USA. pp. 426–428. ISBN 0-02-865705-5.

- ^ Morain, Lloyd and Mary (2007). Humanism as the Next Step (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Humanist Press. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-931779-16-2.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ "History: New York Society for Ethical Culture". New York Society for Ethical Culture. 2008. Retrieved 2009-03-06.

- ^ "Ethical Culture" (PDF). American Ethical Union. Retrieved 2009-02-23.

- ^ Stringer-Hye, Richard. "Charles Francis Potter". Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography. Unitarian Universalist Historical Society. Retrieved 2008-05-01.

- ^ American Humanist Association

- ^ Doerr, Edd (November/December 2002). "Humanism Unmodified". The Humanist. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Amsterdam Declaration 2002". International Humanist and Ethical Union. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ^ "IHEU's Bylaws". International Humanist and Ethical Union. Retrieved 2008-07-05.

- ^ Jones, Dwight (2009) Collective Humanism Essays in the Philosophy of Humanism,Volume 17 (1) www.essaysinhumanism.org

References

- Barry, Peter. "Theory Before Theory: Liberal Humanism", pp. 11–36, in Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory. Manchester University Press, 2002.

- Bauman, Richard. Human Rights in Ancient Rome. Routledge Classical Monographs, 1999 ISBN 0415173205

- Berry, Philippa and Andrew Wernick. The Shadow of Spirit: Post-Modernism and Religion. Routledge, (1992) 2006. ISBN 0415066387

- Davies, Norman. Europe: A History. Oxford University Press, 1996 ISBN 0-19-820171-0

- Gay, Peter. The Party of Humanity. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, (1966) 1971 ISBN0 393006077

- Gay, Peter. Enlightenment: The Science of Freedom. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 1996 ISBN 0393313662

- Giustiniani,Vito. "Homo, Humanus, and the Meanings of Humanism", Journal of the History of Ideas 46 (vol. 2, April–June, 1985): 167–95. [1] [2]

- Hale, John. A Concise Encyclopaedia of the Italian Renaissance. Oxford University Press, 1981 ISBN 0500233330.

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar. The Renaissance Philosophy of Man. The University of Chicago Press, 1950.

- Kristeller, Paul Oskar. Renaissance Thought and its Sources. Columbia University Press, 1979 ISBN 0231045131

- Proctor, Robert. Defining the Humanities. Indiana University Press, 1998 ISBN 0253212197

- Plumb, J.H., ed. The Italian Renaissance. American Heritage, New York, 1961 ISBN 0-618-12738-0 (page refs from 1978 UK Penguin edn).

- Vernant, Jean-Pierre. Origins of Greek Thought. Cornell University Press, (1962) 1984 ISBN 0801492939

- Wernick, Andrew. Auguste Comte and the Religion of Humanity: The Post-theistic Program of French Social Theory. Cambridge University Press, 2001 ISBN 0521662729

External links

select an article title from: Wikisource:1911 Encyclopædia Britannica

Manifestos and statements setting out humanist viewpoints

- Humanist Manifesto I (1933)

- Humanist Manifesto II (1973)

- A Secular Humanist Declaration (1980)

- Amsterdam Declaration (2002)

- Humanist Manifesto III (2003)

Introductions to humanism

- What Is Humanism? from the American Humanist Association

- Morain, Lloyd and Mary: Humanism as the Next Step, from the American Humanist Association

- Huxley, Julian: The Humanist Frame

- Humanism: Why, What, and What For, In 882 Words

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry on Civic Humanism

- Catholic Encyclopedia article on Renaissance Humanism

- Humanism at the Open Directory Project

- Humanistic Judaism

Web articles

- New Humanist British magazine from the Rationalist Press Association (RPA)

- Nanovirus– A humanist perspective on politics, technology and culture

- Modern Humanist An Online Journal for Modern Humanism, Humanist Philosophy & Life

Web books

- The Philosophy of Humanism by Corliss Lamont

- A Guide for the Godless: The Secular Path to Meaning by Andrew Kernohan

- The New Humanism by Edward Howard Griggs

- Thinking and Moral Problems, Religions and Their Source, Purpose, and Developing a Universal Religion, four Parts of a Wikibook.

Web projects

- http://www.human2stay.com/ An interview of humane concept. Some humanistic topics discussed by famous people of today.