Irish language

| Irish | |

|---|---|

| Gaeilge | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɡeːlʲɟə] |

| Native to | Ireland (Republic of) (538,283) United Kingdom (95,000) USA (18,000) EU (Official EU language) |

| Region | Gaeltachtaí, but also spoken throughout Ireland |

Native speakers | 355,000 fluent or native speakers (1983)[1] 538,283 everyday speakers (2006)[citation needed] 1,860,000 with some knowledge (2006)[citation needed] |

| Latin (Irish variant) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | Northern Ireland (UK) Permanent North American Gaeltacht |

| Regulated by | Foras na Gaeilge |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 | ga |

| ISO 639-2 | gle |

| ISO 639-3 | gle |

| ELP | Irish |

Irish ([Gaeilge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is a Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family, originating in Ireland and historically spoken by the Irish people. Irish is now spoken as a first language only by a small minority of the Irish population but is also used as a second language by a larger and expanding minority. It also plays an important symbolic role in the life of the Irish state and is used across the country in a variety of media, personal contexts and social situations. It enjoys constitutional status as the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland, and it is an official language of the European Union. Irish is also an officially recognised minority language in Northern Ireland.

Irish is the main community and household language of 3% of the Republic's population[2] (which was estimated at 4,422,100 in 2008).[3] Estimates of fully native speakers range from 40,000 up to 80,000 people.[4][5][6][7] Areas in which the language remains a vernacular are referred to as Gaeltacht areas.

Irish speakers may, in general, be divided into two groups: traditional native speakers in the Gaeltacht and urban speakers of varying fluency. The second group includes many second-language speakers, but also a certain number of urban native speakers — people raised and educated through Irish and using it outside the home. Recent research suggests that urban Irish is developing in a direction of its own, the result being that Irish speakers from urban and Gaeltacht areas may understand each other only with difficulty.[8] This is related to an urban tendency to simplify the phonetic and grammatical structure of the language.[8] The written standard remains the same for both groups, and urban Irish speakers have played a large part in the production of an extensive modern literature.[9]

The Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs estimated in 2007 that, outside the cities, about 17,000 people lived in strongly Irish-speaking communities, about 10,000 people lived in areas where there was substantial use of the language, and 17,000 people lived in "weak" Gaeltacht communities; Irish was no longer the main community language in the remaining parts of the official Gaeltacht.[10] Complete or functional monolingualism of Irish is now restricted to a handful of elderly within more isolated Gaeltacht regions as well as among many mother-tongue speakers of Irish under school age.

Gaeltacht families with school-age children may if they wish apply for a scheme which involves the payment of grants if the children demonstrate native-level competency in Irish. In the 2006-07 school year, 2,216 families received the full grant of €260 p.a., 937 families received a reduced grant and 225 families did not meet the criteria. This payment scheme is called Scéim Labhairt na Gaeilge, the first example in Europe where citizens are paid to speak their first official language.[11]

Since Irish is an obligatory subject in English-medium schools, it would be reasonable to expect that many people are reasonably fluent second-language speakers. There is, however, no objective evidence for this, though many regard themselves as competent in the language to some degree: 1,656,790 (41.9% of the total population aged three years and over) regard themselves as competent Irish speakers.[12] Of these, 538,283 (32.5%) speak Irish daily (including native speakers and those inside the education system), 97,089 (5.9%) weekly, 581,574 (35.1%) less often, and 412,846 (24.9%) never. 26,998 (1.6%) respondents did not state how often they spoke Irish. Any increase in the number of fluent speakers is likely to be due to the extraordinary growth in the number of Irish-medium schools at both primary and secondary level, chiefly in urban areas.

The number of inhabitants of the official-designated Gaeltacht regions of Ireland is 91,862, as of the 2006 census. Of these, 70.8% aged three and over speak Irish and approximately 60% speak Irish daily.[12] But even as the number of Irish speakers outside the Gaeltacht rises, the use of Irish within the Gaeltacht has decreased. A comprehensive 2007 study found that, despite their largely positive views of the language, Irish is less used among young people than among older generations: even in areas where the language was strongest only 60% of young people used Irish as the main language of communication with family and neighbours, and many preferred English when dealing with the wider world.[13] It concluded that, on current trends, the long-term survival of Irish as the main community language in those areas cannot be guaranteed[13] This suggests that future of the language lies in an urban environment.

Another study has suggested that urban Irish speakers tend to be more highly educated than monolingual English speakers and may enjoy the benefits of language-based networking, leading to better employment and higher social status.[14] Though this study has been criticised for certain unsupported assumptions,[15] the statistical evidence supports the view that urban Irish speakers may, in general, enjoy certain educational advantages.

The Irish government has adopted a twenty year strategy designed to strengthen the language in all areas and greatly increase the number of habitual speakers. This includes the encouragement of urban Irish-speaking districts.[16]

The 2001 census in Northern Ireland showed that 167,487 (10.4%) people "had some knowledge of Irish" (see Irish language in Northern Ireland). Combined, this means that at least one in three people (~1.8 million) on the island of Ireland can understand Irish to some extent. On 13 June 2005, EU foreign ministers unanimously decided to make Irish an official language of the European Union. The new arrangements came into effect on 1 January 2007, and Irish was first used at a meeting of the EU Council of Ministers, by Minister Noel Treacy, T.D., on 22 January 2007.

Names

Irish

In the [Caighdeán Oifigiúil] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (the official written standard) the name of the language is [Gaeilge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (Irish pronunciation: [ˈɡeːlʲɟə]).

Before the spelling reform of 1948, this form was spelled [Gaedhilge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help); originally this was the genitive of [Gaedhealg] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), the form used in classical Modern Irish.[17] Older spellings of this include [Gaoidhealg] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Middle Irish [ge:ʝəlg] and [Goídelc] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [goiðelg] in Old Irish. The modern spelling results from the deletion of the silent dh in the middle of Gaedhilge.

Other forms of the name found in the various modern Irish dialects, in addition to south Connacht [Gaeilge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) mentioned above, include [Gaedhilic/Gaeilic/Gaeilig] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ([ˈɡeːlʲɪc]) or [Gaedhlag] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ([ˈɡeːl̪ˠəɡ]) in Ulster Irish and northern Connacht Irish and [Gaedhealaing/Gaoluinn/Gaelainn] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ([ˈɡˠeːl̪ˠɪŋ/ˈɡˠeːl̪ˠɪn])[18][19] in Munster Irish.

English

The language is usually referred to in English as Irish. The term Irish Gaelic is often used when English speakers discuss the relationship between the three Goidelic languages (Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx) or when discussion of Irish is confused to mean Hiberno-English, the form of English as spoken in Ireland. Scottish Gaelic is often referred to in English as simply Gaelic. Outside Ireland and often among native-speakers themselves, the term Gaelic is still frequently used for the language.[20] The archaic term Erse (from Erische), originally a Scots form of the word Irish applied in Scotland (by Lowlanders) to all of the Goidelic languages, is no longer used for any Goidelic language, and in most current contexts is considered derogatory.[21][22]

History

Written Irish is first attested in Ogham inscriptions from the fourth century AD; this stage of the language is known as Primitive Irish. These writings have been found throughout Ireland and the west coast of Great Britain. Primitive Irish transitioned into Old Irish through the 5th century. Old Irish, dating from the sixth century, used the Latin alphabet and is attested primarily in marginalia to Latin manuscripts. By the 10th century Old Irish evolved into Middle Irish, which was spoken throughout Ireland and in Scotland and the Isle of Man. It is the language of a large corpus of literature, including the famous Ulster Cycle. From the 12th century Middle Irish began to evolve into modern Irish in Ireland, into Scottish Gaelic in Scotland, and into the Manx language in the Isle of Man. Early Modern Irish, dating from the thirteenth century, was the literary language of both Ireland and Gaelic-speaking Scotland, and is attested by such writers as Geoffrey Keating. Modern Irish emerged from the literary language known as Early Modern Irish in Ireland and as Classical Gaelic in Scotland; this was used through the 18th century.

From the eighteenth century the language went into a decline, rapidly losing ground to English due in part to restrictions dictated by British rule - a conspicuous example of the process known by linguists as language shift.[23] In the mid-nineteenth century it lost a large portion of its speakers to death and emigration resulting from poverty, particularly in the wake of the Great Famine (1845–1849).

At the end of the nineteenth century, members of the Gaelic Revival movement made efforts to encourage the learning and use of Irish in Ireland. Particular emphasis was placed at that point on the folk tradition, which in Irish is particularly rich, but efforts were also made to develop journalism and a modern literature.

Official status

Ireland

Irish is given recognition by the Constitution of Ireland as the national and first official language of the Republic of Ireland (with English being a second official language). Since the foundation of the Irish Free State in 1922 (see also History of the Republic of Ireland), the Irish Government required a degree of proficiency in Irish for all those who became newly appointed to civil service positions (including postal workers, tax officials, agricultural inspectors, etc.).[24] Proficiency in just one official language for entrance to the public service was introduced in 1974, in part through the actions of protest organizations like the Language Freedom Movement.

While the First Official Language requirement was also dropped for wider public service jobs, Irish remains a required subject of study in all schools within the Republic which receive public money (see also Education in the Republic of Ireland). Those wishing to teach in primary schools in the State must also pass a compulsory examination called "Scrúdú Cáilíochta sa Ghaeilge". The need for a pass in Leaving Certificate Irish or English for entry to the Gardaí (police) was introduced in September 2005, although applicants are given lessons in the language during the two years of training. All official documents of the Irish Government must be published in both Irish and English or Irish alone (this is according to the official languages act 2003, which is enforced by "an comisinéir teanga", the language ombudsman).

The National University of Ireland requires all students wishing to embark on a degree course in the NUI federal system to pass the subject of Irish in the Leaving Certificate or GCE/GCSE Examinations.[25] Exemptions are made from this requirement for students born outside of the Republic of Ireland, those who were born in the Republic but completed primary education outside it, and students diagnosed with dyslexia.

In 1938, the founder of Conradh na Gaeilge (The Gaelic League), Douglas Hyde, was inaugurated as the first President of Ireland. The record of his delivering his auguration Declaration of Office in Roscommon Irish remains almost the only surviving remnant of anyone speaking in that dialect.

The National University of Ireland, Galway is required to appoint people who are competent in the Irish language, as long as they meet all other respects of the vacancy they are appointed to. This requirement is laid down by the University College Galway Act, 1929 (Section 3).[26] It is expected that the requirement may be repealed in due course.[27]

Even though modern parliamentary legislation is supposed to be issued in both Irish and English, in practice it is frequently only available in English. This is notwithstanding that Article 25.4 of the Constitution of Ireland requires that an "official translation" of any law in one official language be provided immediately in the other official language—if not already passed in both official languages.[28]

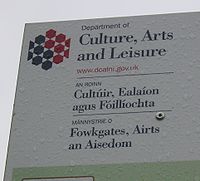

Northern Ireland

Prior to the establishment of the Northern Ireland state in 1921, Irish was recognised as a school subject and as "Celtic" in some third level institutions. Between 1921 and 1972, Northern Ireland had devolved government. During those years the political party holding power in the Stormont Parliament, the Ulster Unionist Party (UUP), was hostile to the language.[citation needed] In broadcasting, there was an exclusion on the reporting of minority cultural issues, and Irish was excluded from radio and television for almost the first fifty years of the previous devolved government.[29] The language received a degree of formal recognition in Northern Ireland from the United Kingdom, under the 1998 Good Friday Agreement,[30] and then, in 2001, by the Government's ratification in respect of the language of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. The British government promised to create legislation encouraging the language as part of the 2006 St Andrews Agreement.[31]

European Union

Irish became an official language of the EU on 1 January 2007 meaning that MEP's with Irish fluency can now speak the language in the EU Parliament in Europe and at committees although in the case of the latter they have to give prior notice to a simultaneous interpreter in order to ensure that what they say can be interpreted into other languages. While an official language of the European Union, only co-decision regulations must be available in Irish for the moment, due to a renewable five-year derogation on what has to be translated, requested by the Irish Government when negotiating the language's new official status. Any expansion in the range of documents to be translated will depend on the results of the first five-year review and on whether the Irish authorities decide to seek an extension. The Irish government has committed itself to train the necessary number of translators and interpreters and to bear the related costs.[32]

Before Irish became an official language it was afforded the status of treaty language and only the highest-level documents of the EU had been made available in Irish.

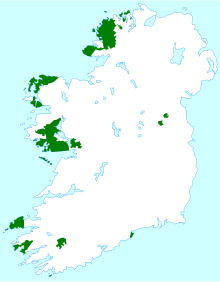

Gaeltacht

There are parts of Ireland where Irish is still spoken as a traditional, native language used daily. These regions are known collectively as Gaeltachts, or in the plural Irish Gaeltachtaí. While the Gaeltacht's fluent Irish speakers, whose numbers have been estimated by scholar Donncha Ó hÉallaithe at twenty or thirty thousand,[33] are a minority of the total number of fluent Irish speakers, they represent a higher concentration of Irish speakers than other parts of the country and it is only in Gaeltacht areas (in especial the more strongly Irish-speaking ones) that Irish continues to be a natural vernacular of the general population.

There are Gaeltacht regions in:

- County Galway ([Contae na Gaillimhe] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), including Connemara ([Conamara] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), the Aran Islands ([Oileáin Árann] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), Carraroe ([An Cheathrú Rua] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Spiddal ([An Spidéal] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help));

- on the west coast of County Donegal ([Contae Dhún na nGall] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)); in the part which is known as Tyrconnell ([Tír Chonaill] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help));

- Dingle Peninsula ([Corca Dhuibhne] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) in County Kerry ([Contae Chiarraí] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)).

Smaller ones also exist in:

| English | Irish |

|---|---|

| Mayo | Contae Mhaigh Eo |

| Meath | Contae na Mí |

| Waterford | Contae Phort Láirge |

| Cork | Contae Chorcaí |

To summarise the extent of the survival: (See Hindley, 'The Death of the Irish Language', Map 7: Irish speakers by towns and distinct electoral divisions, census 1926.) Irish remains as a natural vernacular in the following areas: south Connemara, from a point west of Spiddal, covering Inverin, Carraroe, Rosmuck, and the islands; the Aran Islands; northwest Donegal in the area around Gweedore, including Rannafast, Gortahork, the surrounding townlands and Tory Island; in the townland of Rathcarn, Co. Meath.

Gweedore ([Gaoth Dobhair] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)),County Donegal is the largest Gaeltacht parish in Ireland.

The numerically and socially strongest Gaeltacht areas are those of South Connemara, the west of the Dingle Peninsula and northwest Donegal, in which the majority of residents use Irish as their primary language. These areas are often referred to as the [Fíor-Ghaeltacht] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("true Gaeltacht") and collectively have a population just under 20,000.

Irish summer colleges are attended by tens of thousands of Irish teenagers annually. Students live with Gaeltacht families, attend classes, participate in sports, go to céilithe and are obliged to speak Irish. All aspects of Irish culture and tradition are encouraged.

According to data compiled by the Irish Department of Community, Rural and Gaeltacht Affairs, only one quarter of households in officially Gaeltacht areas possess a fluency in Irish. The author of a detailed analysis of the survey, Donncha Ó hÉallaithe of the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, described the Irish language policy followed by Irish governments a "complete and absolute disaster". The Irish Times, referring to his analysis published in the Irish language newspaper Foinse, quoted him as follows: "It is an absolute indictment of successive Irish Governments that at the foundation of the Irish State there were 250,000 fluent Irish speakers living in Irish-speaking or semi Irish-speaking areas, but the number now is between 20,000 and 30,000."[34]

Dialects

There are a number of distinct dialects of Irish. Roughly speaking, the three major dialect areas coincide with the provinces of Munster ([Cúige Mumhan] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), Connacht ([Cúige Chonnacht] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Ulster ([Cúige Uladh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). Records of some dialects of Leinster were made by the Irish Folklore Commission among other bodies prior to their extinction. Newfoundland, in eastern Canada, is also seen to have a minor dialect of Irish, closely resembling the Munster Irish spoken during the 16th to 17th centuries (see Newfoundland Irish).

Munster

Munster Irish is mainly spoken in the Gaeltacht areas of Kerry ([Contae Chiarraí] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), Ring ([An Rinn] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) near Dungarvan ([Dún Garbháin] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) in County Waterford ([Contae Phort Láirge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Muskerry ([Múscraí] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Cape Clear Island ([Oileán Chléire] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) in the western part of County Cork ([Contae Chorcaí] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). The most important subdivision in Munster is that between Decies Irish (Na Déise) (spoken in Waterford) and the rest of Munster Irish.

Some typical features of Munster Irish are:

- The use of endings to show person on verbs in parallel with a pronominal subject system, thus "I must" is in Munster [caithfead] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) as well as [caithfidh mé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), while other dialects prefer [caithfidh mé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ([mé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) means "I"). "I was and you were" is [Bhíos agus bhís] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) as well as [Bhí mé agus bhí tú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Munster, but more commonly [Bhí mé agus bhí tú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in other dialects. Note that these are strong tendencies, and the personal forms Bhíos etc. are used in the West and North, particularly when the words are last in the clause.

- Use of independent/dependent forms of verbs that are not included in the Standard. For example, "I see" in Munster is [chím] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), which is the independent form – Northern Irish also uses a similar form, tchím), whereas "I do not see" is [ní fheicim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), feicim being the dependent form, which is used after particles such as ní "not"). Chím is replaced by feicim in the Standard. Similarly, the traditional form preserved in Munster [bheirim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) I give/[ní thugaim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is [tugaim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/[ní thugaim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in the Standard; [gheibhim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) I get/[ní bhfaighim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is [faighim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)/[ní bhfaighim] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

- When before -nn, -m, -rr, -rd, -ll and so on, in monosyllabic words and in the stressed syllable of multisyllabic words where the syllable is followed by a consonant, some short vowels are lengthened while others are diphthongised, thus ceann [kʲaun] "head", cam [kɑum] "crooked", gearr [ɡʲaːr] "short", ord [oːrd] "sledgehammer", gall [ɡɑul] "foreigner, non-Gael", iontas [uːntəs] "a wonder, a marvel", compánach [kəumˈpɑːnəx] "companion, mate", etc.

- A copular construction involving [ea] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "it" is frequently used. Thus "I am an Irish person" can be said is Éireannach mé and Éireannach is ea mé in Munster; there is a subtle difference in meaning, however, the first choice being a simple statement of fact, while the second brings emphasis onto the word Éireannach. In effect the construction is a type of "fronting".

- Both masculine and feminine words are subject to lenition after insan (sa/san) "in the", den "of the" and don "to/for the" : sa tsiopa, "in the shop", compared to the Standard sa siopa (the Standard lenites only feminine nouns in the dative in these cases).

- Eclipsis of f after sa: sa bhfeirm, "in the farm", instead of san fheirm.

- Eclipsis of t and d after preposition + singular article, with all prepositions except after insan, den and don: ar an dtigh "on the house", ag an ndoras "at the door".

- Stress falls in general found on the second syllable of a word when the first syllable contains a short vowel, and the second syllable contains a long vowel, diphthong, or is -(e)ach, e.g. [biorán] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("pin"), as opposed to [biorán] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Connacht and Ulster.

Connacht

The strongest dialect of Connacht Irish is to be found in Connemara and the Aran Islands. Much closer to the larger Connacht Gaeltacht is the dialect spoken in the smaller region on the border between Galway ([Gaillimh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Mayo ([Maigh Eo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). The northern Mayo dialect of Erris ([Iorras] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Achill ([Acaill] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) is in grammar and morphology essentially a Connacht dialect, but shows some similarities to Ulster Irish due to large-scale immigration of dispossessed people following the Plantation of Ulster.

There are features in Connemara Irish outside the official standard—notably the preference for verbal nouns ending in [-achan] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), e.g. [lagachan] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) instead of [lagú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), "weakening". The non-standard pronunciation of the Cois Fharraige area with lengthened vowels and heavily reduced endings gives it a distinct sound. Distinguishing features of Connacht and Ulster dialect include the pronunciation of word final broad bh and mh as [w], rather than as [vˠ] in Munster. For example [sliabh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("mountain") is pronounced [ʃlʲiəw] in Connacht and Ulster as opposed to [ʃlʲiəβ] in the south. In addition Connacht and Ulster speakers tend to include the "we" pronoun rather than use the standard compound form used in Munster e.g. [bhí muid] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is used for "we were" instead of [bhíomar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

Like in Munster Irish, when before -nn, -m, -rr, -rd, -ll and so on, in monosyllabic words and in the stressed syllable of multisyllabic words where the syllable is followed by a consonant, some short vowels are lengthened while others are diphthongised, thus ceann [kʲaun] "head", cam [kɑum] "crooked", gearr [gʲɑ:r] "short", ord [ourd] "sledgehammer", gall [gɑul] "foreigner, non-Gael", iontas [i:ntəs] "a wonder, a marvel", etc.

The present-day Irish of Meath (in Leinster) is a special case. It belongs mainly to the Connemara dialect. The Irish-speaking community in Meath is mostly a group of Connemara speakers who moved there in the 1930s after a land reform campaign spearheaded by Máirtín Ó Cadhain (who subsequently became one of the greatest modernist writers in the language).

Irish President Douglas Hyde was one of the last of speakers of the Roscommon dialect of Irish.

Ulster

Linguistically the most important of the Ulster dialects today is that of the Rosses ([na Rossa] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), which has been used extensively in literature by such authors as the brothers Séamus Ó Grianna and Seosamh Mac Grianna, locally known as Jimí Fheilimí and Joe Fheilimí. This dialect is essentially the same as that in Gweedore ([Gaoth Dobhair] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) = Inlet of Streaming Water), and used by native singers Enya ([Eithne] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) and Máire Brennan and their siblings in Clannad ([Clann as Dobhar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) = Family from the Dobhar [a section of Gweedore]) Na Casaidigh, and Mairéad Ní Mhaonaigh from another local band Altan.

Ulster Irish sounds very different and shares several features with Scottish Gaelic, as well as having lots of characteristic words and shades of meanings. However, since the demise of those Irish dialects spoken natively in what is today Northern Ireland, it is probably an exaggeration to see Ulster Irish as an intermediary form between Scottish Gaelic and the southern and western dialects of Irish. For instance, Northern Scottish Gaelic has many non-Ulster features in common with Munster Irish.

One noticeable trait of Ulster Irish and Scots Gaelic is the use of the negative particle [cha(n)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in place of the Munster and Connacht [ní] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). Southern Ulster irish retains [ní] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) most strongly, while cha(n) has ousted ní in northernmost dialects (e.g. Rosguill and Tory Island), though even in these areas [níl] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "is not" is more common than chan fhuil or cha bhfuil.[35][36]

An Caighdeán Oifigiúil

This section possibly contains original research. (August 2009) |

An Caighdeán Oifigiúil ("The Official Standard"), often shortened to An Caighdeán, is the standard language, which is taught in most schools in Ireland, though with strong influences from local dialects.

Its development had two purposes. One was to simplify Irish spelling, which had retained its Classical spelling, by removing many silent letters, and to give a standard written form that was "dialect free". Though many aspects of the Caighdeán are essentially those of Connacht Irish, this was simply because this is the central dialect which forms a "bridge", as it were, between the North and South. In reality, dialect speakers pronounce words as in their own dialect, as the spelling simply reflects the pronunciation of Classical Irish. For example, [ceann] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "head" in early modern Irish was pronounced [cenˠː]. The spelling has been retained, but the word is variously pronounced [caun] in the South, [cɑːn] in Connacht, and [cænː] in the North. [Beag] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "small" was [bʲɛɡ] in early modern Irish, and is now [bʲɛɡ] in Waterford Irish, [bʲɔɡ] in Cork-Kerry Irish, varies between [bʲɔɡ] and [bʲæɡ] in the West, and is [bʲœɡ] in the North.

The simplification, however, in some cases probably went too far in simplifying the standard with only reference to the West. For example, the early modern Irish [leabaidh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [lʲebʷɨʝ] "bed" is pronounced [lʲabʷə] as well as [lʲabʷɨɟ] in Waterford Irish, [lʲabʷɨɟ] in Cork-Kerry Irish, [lʲæbʷə] in Connacht Irish ([lʲæːbʷə] in Cois Fharraige Irish), and [lʲæbʷi] in the North. Native speakers from the North and South consider that leabaidh should be the representation in the Caighdeán rather than actual [leaba] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

On the other hand, the Caighdeán arguably did not go far enough in many cases. For example, it has retained the Classical Irish spelling of [ar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "on, for, etc." and [ag] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "at, by, of, etc.". The first is pronounced [ɛɾʲ] throughout the Goidelic-speaking world (and is written [er] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Manx, and [air] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Scottish Gaelic), and should be written either [eir] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [oir] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [air] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Irish. The second is pronounced [ɪɟ] in the South, and [ɛɟ] in the North and West. Again, Manx and Scottish Gaelic reflect this pronunciation much more clearly than Irish does (Manx [ec] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Scottish [aig] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)).

In many cases, however, the Caighdeán can only refer to the Classical language, in that every dialect is different, as happens in the personal forms of [ag] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "at, by, of, etc."

- Munster : agùm, agùt, igè, icì, agùing/aguìng (West Cork/Kerry agùin/aguìn), agùibh/aguìbh, acù

- Connacht : am (agam), ad (agad), aige [egɨ], aici [ekɨ], ainn, aguí, acab

- Ulster : aigheam, aighead, aige [egɨ], aicí [eki], aighinn, aighif, acú

- Caighdeán : [agam, agat, aige, aici, againn, agaibh, acu] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)

Another purpose was to create a grammatically "simplified" standard which would make the language easier to learn for the majority English speaking school population. In part this is why the Caighdeán is not universally respected by native speakers, in that it makes simplified language an ideal, rather than the ideal that native speakers traditionally had of their dialects (or of the Classical dialect if they had knowledge of that). Of course, this was not the original aim of the developers, who rather saw the "school-version" Caighdeán as a means of easing second-language learners into the task of learning "full" Irish. The Caighdeán verb system is a prime example, with the reduction in irregular verb forms and personal forms of the verb – except for the first persons. However, once the word "standard" becomes used, the forms represented as "standard" take on a power of their own, and therefore the ultimate goal has become forgotten in many circles.

The Caighdeán is in general spoken by non-native speakers, frequently from the capital, and is sometimes also called "Dublin Irish". As it is taught in many Irish-Language schools (where Irish is the main, or sometimes only, medium of instruction), it is also sometimes called "Gaelscoil Irish". The so-called "Belfast Irish", spoken in that city's Gaeltacht Quarter is the Caighdeán heavily influenced by Ulster Irish.

Comparisons

The differences between dialects are considerable, and have led to recurrent difficulties in defining standard Irish. A good example is the greeting "How are you?". Just as this greeting varies from region to region, and between social classes, among English speakers, this greeting varies among Irish speakers:

- Ulster: [Cad é mar atá tú?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("What is it as you are?" Note: [caidé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [goidé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and sometimes [dé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) are alternative renderings of [cad é] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- Connacht: [Cén chaoi a bhfuil tú?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("What way [is it] that you are?")

- Munster: [Conas taoi?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [Conas tánn tú?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("How are you?" - conas was originally cia nós "what custom/way")

- "Standard" Irish: [Conas atá tú?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("How are you?")

In recent decades contacts between speakers of different dialects have become more frequent and the differences between the dialects are less noticeable.

Linguistic structure

The features most unfamiliar to English speakers of the language are the orthography, the initial consonant mutations, the Verb Subject Object word order, and the use of two different forms for "to be". None of these features are peculiar to Irish, however. All of them occur in other Celtic languages as well as in non-Celtic languages: morphosyntactically triggered initial consonant mutations are found in Fula, VSO word order is found in Classical Arabic and Biblical Hebrew, and Portuguese and Spanish have two different forms for "to be".

Syntax

Word order in Irish is of the form VSO (Verb-Subject-Object) so that, for example, "He hit me" is [Bhuail] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [hit-past tense] [sé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [he] [mé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) [me].

One aspect of Irish syntax that is unfamiliar to speakers of other languages is the use of the copula (known in Irish as [an chopail] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)). The copula is used to describe the permanent identity or characteristic of a person or thing (e.g. "who" or "what"), as opposed to temporary aspects such as "how", "where", "why" and so on. This has been likened to the difference between the verbs [ser] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and [estar] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) in Spanish and Portuguese (see Romance copula), although this is not an exact match.[citation needed]

Examples are:

- [Is fear é.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "He is a man." (Spanish [Es un hombre] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Portuguese [É um homem] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- [Is fuar é.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "He is a cold(hearted) person." (Spanish [Es frío] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Portuguese [É frio] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- [Tá sé/Tomás fuar.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "He/Thomas is cold" (= feels cold). (Spanish [Tiene frío] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) – in this case Spanish says "has", Portuguese [Está com frio] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- [Tá sé/Tomás ina chodladh.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "He/Thomas is asleep." (Spanish [Él está durmiendo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Portuguese [Ele está dormindo] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- [Is maith é.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "He is good (a good person)." (Spanish [Es bueno] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Portuguese [É bom] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- [Tá sé go maith.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "He is well." (Spanish [ Él está bien] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), Portuguese [Ele está bem] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

Morphology

Another feature of Irish grammar that is shared with other Celtic languages is the use of prepositional pronouns ([forainmneacha réamhfhoclacha] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), which are essentially conjugated prepositions. For example, the word for "at" is [ag] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), which in the first person singular becomes [agam] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "at me". When used with the verb [bí] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("to be") [ag] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) indicates possession; this is the equivalent of the English verb "to have".

- [Tá leabhar agam.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "I have a book." (Literally, "there is a book at me.")

- [Tá leabhar agat.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "You have a book."

- [Tá leabhar aige.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "He has a book."

- [Tá leabhar aici.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "She has a book."

- [Tá leabhar againn.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "We have a book."

- [Tá leabhar agaibh.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "You (plural) have a book."

- [Tá leabhar acu.] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "They have a book."

Orthography and pronunciation

The alphabet which modern Irish typically uses is similar to English without the letters j,k,q,w,x,y,z, however some anglicised words with no unique Irish meaning like 'Jeep' are written as 'Jíp'. Some words take a letter(s) not traditionally used and replace it with the closest phonetic sound, e.g. 'phone'>'Fón'. The written language looks rather daunting to those unfamiliar with it. Once understood, the orthography is relatively straightforward. The acute accent, or [síneadh fada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (´), serves to lengthen the sound of the vowels and in some cases also changes their quality. For example, in Munster Irish (Kerry), a is /a/ or /ɑ/ and á is /ɑː/ in "law" but in Ulster Irish (Donegal), á tends to be /æː/.

Around the time of World War II, Séamas Daltún, in charge of [Rannóg an Aistriúcháin] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (the official translations department of the Irish government), issued his own guidelines about how to standardise Irish spelling and grammar. This de facto standard was subsequently approved of by the State and called the Official Standard or [Caighdeán Oifigiúil] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). It simplified and standardised the orthography. Many words had silent letters removed and vowel combination brought closer to the spoken language. Where multiple versions existed in different dialects for the same word, one or more were selected.

Examples:

- [Gaedhealg / Gaedhilg(e) / Gaedhealaing / Gaeilic / Gaelainn / Gaoidhealg / Gaolainn] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) → [Gaeilge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), "Irish language" ([Gaoluinn] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [Gaolainn] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is still used in books written in dialect by Munster authors, or as a facetious name for the Munster dialect)

- [Lughbhaidh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) → [Lú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), "Louth"

- [biadh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) → [bia] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), "food"

The standard spelling does not always reflect every dialect's pronunciation. For example, in standard Irish, bia, "food", has the genitive bia. But in Munster Irish, the genitive is pronounced /bʲiːɟ/.[37] For this reason, the spelling [biadh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) is still used by the speakers of some dialects, in particular those that show a meaningful and audible difference between [biadh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (nominative case) and [bídh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (genitive case) "of food, food's". In Munster, the latter spelling regularly produces the pronunciation /bʲiːɟ/ because final -idh, -igh regularly delenites to -ig in Munster pronunciation. Another example would be the word crua, meaning "hard". This pronounced /kruəɟ/[38] in Munster, in line with the pre-Caighdeán spelling, cruaidh. In Munster, ao is pronounced /eː/ and aoi pronounced /iː/,[39] but the new spellings of saoghal, "life, world", genitive: saoghail, have become saol, genitive saoil. This produces irregularities in the matchup between the spelling and pronunciation in Munster, because the word is pronounced /sˠeːl̪ˠ/, genitive /sˠeːlʲ/.[40]

Modern Irish has only one diacritic sign, the acute (á é í ó ú), known in Irish as the [síneadh fada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "long mark", plural [sínte fada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). In English, this is frequently referred to as simply the [fada] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), where the adjective is used as a noun. The dot-above diacritic, called a [ponc séimhithe] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or [sí buailte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (often shortened to [buailte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)), derives from the punctum delens used in medieval manuscripts to indicate deletion, similar to crossing out unwanted words in handwriting today. From this usage it was used to indicate the lenition of s (from /s/ to /h/) and f (from /f/ to zero) in Old Irish texts.

Lenition of c, p, and t was indicated by placing the letter h after the affected consonant; lenition of other sounds was left unmarked. Later both methods were extended to be indicators of lenition of any sound except l and n, and two competing systems were used: lenition could be marked by a [buailte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or by a postposed h. Eventually, use of the [buailte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) predominated when texts were writing using Gaelic letters, while the h predominated when writing using Roman letters.

Today the Gaelic script and the [buailte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) are rarely used except where a "traditional" style is required, e.g. the motto on the University College Dublin coat of arms or the symbol of the Irish Defence Forces, The Irish Defence Forces cap badge [(Óglaiġ na h-Éireann)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). Letters with the [buailte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) are available in Unicode and Latin-8 character sets (see Latin Extended Additional chart).[41]

Mutations

In Irish, there are two classes of initial consonant mutations:

- Lenition (in Irish, [séimhiú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "softening") describes the change of stops into fricatives. Indicated in old orthography by a [buailte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) written above the changed consonant, this is now shown in writing by adding an -h:

- [caith!] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "throw!" — [chaith mé] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "I threw" (this is an example of the lenition as a past-tense marker, which is caused by the use of [do] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), although it is now usually omitted)

- [margadh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "market", "market-place", "bargain" — [Tadhg an mhargaidh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "the man of the street" (word for word "Tadhg of the market-place"; here we see the lenition marking the genitive case of a masculine noun)

- [Seán] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "Seán, John" — [a Sheáin!] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "O John!" (here we see lenition as part of what is called the vocative case — in fact, the vocative lenition is triggered by the [a] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) or vocative marker before [Sheáin] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help))

- Eclipsis (in Irish, [urú] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help)) covers the voicing of voiceless stops, as well as the nasalisation of voiced stops.

- [athair] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "father" — [ár nAthair] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "our Father"

- [tús] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "start", [ar dtús] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "at the start"

- [Gaillimh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "Galway" — [i nGaillimh] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) "in Galway"

Current status

Republic of Ireland

The number of native Irish-speakers in the Republic of Ireland today is a smaller fraction of the population than it was at independence. Many Irish speaking families encouraged their children to speak English as it was the language of education and employment; the Irish-speaking areas today were always relatively poor and remote, and this remoteness caused the survival of the language as a vernacular. The Official Languages Act of 2003 gave people the right to interact with state bodies in Irish. It is too early to assess how well this is working in practice. Other factors were outward migration of Irish speakers from the Gaeltacht (see related issues at Irish diaspora) and inward migration of English-speakers. The Planning and Development Act (2000) attempted to address the latter issue, with varied levels of success. Planning controls now require new housing in Gaeltacht areas to be allocated to English-speakers and Irish-speakers in the same ratio as the existing population of the area. This is intended to prevent new houses allocated to Irish-speakers being immediately sold on to English-speakers.[citation needed] However, the restriction only lasts for a few years. Also, people are not required to reach native speaker standards of fluency to qualify as Irish-speakers.

On 19 December 2006 the government announced a 20-year strategy to help Ireland become a fully bilingual country. This involved a 13 point plan and encouraging the use of language in all aspects of life.[42][43]

Percentage of Irish-Speakers by County

This is a List of Irish counties by the percentage of those professing some ability in the Irish language in Ireland in the 2006 Irish census. The census did not record Irish speakers living outside of the Republic of Ireland.

The census produced [3] a detailed breakdown of abilities as:

- Irish spoken inside or outside the education

- Native speakers in the Gaeltacht areas.

| County | Irish % |

|---|---|

| County Carlow | 39.5 |

| County Dublin | 37.2 |

| County Kildare | 42.4 |

| County Kilkenny | 43.5 |

| County Laois | 42.6 |

| County Longford | 41.2 |

| County Louth | 36.7 |

| County Meath | 40.1 |

| County Offaly | 39 |

| County Westmeath | 41.5 |

| County Wexford | 37.4 |

| County Wicklow | 38 |

| County Clare | 48.8 |

| County Cork | 46.6 |

| County Kerry | 47.2 |

| County Limerick | 46.2 |

| County Tipperary | 45 |

| County Waterford | 44.2 |

| County Galway | 49.8 |

| County Leitrim | 43.1 |

| County Mayo | 47.2 |

| County Roscommon | 45 |

| County Sligo | 43.9 |

| County Cavan | 38 |

| County Donegal | 39.6 |

| County Monaghan | 39.6 |

Placenames

The Placenames Order (Gaeltacht Districts)/[An tOrdú Logainmneacha (Ceanntair Gaeltachta)] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) (2004) requires the original Irish placenames to be used in the Gaeltacht on all official documents, maps and roadsigns. This has removed the legal status of those placenames in the Gaeltacht in English. Opposition to these measures comes from several quarters, including some people within popular tourist destinations located within the Gaeltacht (namely in Dingle) who claim that tourists may not recognise the Irish forms of the placenames.

Following a campaign in the 1960s and early 1970s, most road-signs in Gaeltacht regions have been in Irish only. Most maps and government documents did not change, though Ordnance Survey (government) maps showed placenames bilingually in the Gaeltacht (and generally in English only elsewhere). Unfortunately, most other map companies wrote only the English placenames, leading to significant confusion in the Gaeltacht. The Act therefore updates government documents and maps in line with what has been reality in the Gaeltacht for the past 30 years. Private map companies are expected to follow suit.

Beyond the Gaeltacht only English placenames were officially recognised (pre 2004). However, further placenames orders have been passed to enable both the English and Irish placenames to be used. The village of Straffan is still marked variously as [An Srafáin, An Cluainíní] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) and [Teach Strafáin] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help), even though Irish has not been the spoken widely there for two centuries. In the 1830s John O'Donovan listed it as "Srufáin"[44] The nearby village of Kilteel was "Cill tSile" for centuries, meaning "The church of Saint Síle", but since 2000 it is shown as "Cill Cheile", which does not carry the same meaning. There are numerous[citation needed] other examples.

Irish vehicle registration plates are bilingual: the county of registration is shown in Irish above the plate number as a kind of surtitle, and is encoded from English within the plate number. For example, a Dublin plate is surtitled Baile Átha Cliath and the plate number includes D.

Conradh na Gaeilge has expressed concern over the proposed introduction of postcodes, which, similarly, may use abbreviations based on English language place names, although people sending mail would still be able to use addresses in Irish. It has advocated that postcodes should either consist solely of numbers, as in many other bilingual countries, or be based on Irish language names instead.[45]

Companies using Irish

Tesco Ireland and Superquinn have in-store Irish signage. Several companies (mostly current and ex-semistate bodies) publish their yearly reports in both Irish and English. These include Eircom, An Post and the ESB. Other companies have Irish language options on their websites. Examples of these include Bord Gáis, Meteor, and An Post. Meteor has also begun to offer an Irish language voicemail option to its customers. People corresponding with bodies like the Revenue and the ESB can also send and receive correspondence in Irish or English. Some Irish banks provide cheque books and ATM cards in both languages, and others - notably Bank of Ireland - have introduced an Irish language interface option on their ATM machines.[citation needed] The ESB have Irish-speaking customer support representatives and offer both Irish and English language options on their phone lines, they also offer written correspondance in both languages.

Daily life

Several computer software products have the option of an Irish-language interface. Prominent examples include KDE,[46] Mozilla Firefox,[47] Mozilla Thunderbird,[47] OpenOffice.org,[48] and Microsoft Windows XP.[49]

Many English-speaking Irish people use small and simple phrases (known as cúpla focal, "a few words") in their everyday speech, e.g. [Slán] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("goodbye"), [Slán abhaile] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("get home safely"), [Sláinte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("good health"; used when drinking like "bottoms up" or "cheers"), [Go raibh maith agat] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("thank you"), [Céad míle fáilte] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("a hundred thousand welcomes", a tourist board saying, also used by President Hillery to welcome Pope John Paul II to Ireland in 1979) and [Conas atá tú?] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) ("How are you?"). There are many more small sayings that have crept into Hiberno-English. The term craic has been popularised outside Ireland in this Gaelicized spelling: "How's the craic?" or "What's the craic'?" ("how's the fun?"/"how is it going?"), though the word is not Irish in origin, and the expression "How's the crack?" was widely used in Ireland since at least the 1960s before the Irish-language spelling "craic" became the common journalistic style.

Many public bodies have Irish language or bilingual names, but some have downgraded the language. An Post, the Republic's postal service, displays Irish place names in both Irish and English with equal prominence outside its offices and continues to have place names in Irish on its postmarks as well as recognising addresses. Royal Mail also recognises Irish language place names in Northern Ireland.[50] Traditionally, the private sector has been less supportive, although support for the language has come from some private companies. For example, Irish supermarket chain Superquinn introduced bilingual signs in its stores in the 1980s, a move which was followed more recently by the British chain Tesco for its stores in the Republic. Woodies DIY now also have bilingual signs in their chain of stores. In contrast, the "100% Irish" SuperValu has few if any Irish signs, and the German retailers Aldi and Lidl have none at all.

In an effort to increase the use of the Irish language by the State, the Official Languages Act was passed in 2003. This act ensures that most publications made by a governmental body must be published in both official languages, Irish and English. In addition, the office of Language Commissioner has been set up to act as an ombudsman with regard to equal treatment for both languages.

A major factor in the decline of natively-spoken Irish has been the movement of English speakers into the Gaeltacht (predominantly Irish speaking areas) and the return of native Irish-speakers who have returned with English-speaking partners. This has been stimulated by government grants and infrastructure projects:[51] "only about half Gaeltacht children learn Irish in the home... this is related to the high level of in-migration and return migration which has accompanied the economic restructuring of the Gaeltacht in recent decades".[52] In a last-ditch effort to stop the demise of Irish-speaking in Connemara in Galway, planning controls have been introduced on the building of new homes in Irish speaking areas.

Thanks in large part to Gael-Taca and Gaillimh le Gaeilge and two local groups a significant number of new residential developments are named in Irish today in most of the Republic of Ireland. In several counties there are a large number being named in Irish.[53]

In 2007 Irish television channel TG4 aired No Béarla, a series of programmes in which the writer Manchán Magan travels around Ireland trying to speak only Irish, and encountering mostly complete incomprehension as he does so.

Modern Literature in Irish

Though Irish is the language of a small minority, it has a distinguished modern literature. The foremost prose writer is considered to be Máirtín Ó Cadhain (1906–1970), whose dense and complex work has been compared to that of James Joyce. Two outstanding poets are Seán Ó Ríordáin (1907–1977) and the lyricist and scholar Máire Mhac an tSaoi (b.1922). There are many less notable figures who have produced interesting work.

In the first half of the 20th century the best writers were from the Gaeltacht or closely associated with it. Remarkable autobiographies from this source include An tOileánach (“The Islandman”) by Tomás Ó Criomhthain (1856–1937) and Fiche Bliain ag Fás (“Twenty Years A’Growing”) by Muiris Ó Súilleabháin (1904–1950).

Irish has also proved to be an excellent vehicle for scholarly work, though chiefly in such areas as historical studies and literary criticism.

There are several publishing houses which specialise in Irish-language material and which together produce scores of titles every year.

Media

Radio

Irish has a significant presence in radio and television, as evidenced by RTÉ Raidió na Gaeltachta (Gaeltacht radio)[54] and Teilifís na Gaeilge (Irish language television, initially abbreviated to 'TnaG', now renamed TG4). There are also the community stations Raidió na Life in Dublin and Raidió Fáilte in Belfast, the former being an important training station for those wishing to work in radio professionally. There is also one youth radio station Raidió Rí-Rá.

Community radio stations in Ireland try to have at least one Irish language programme per week depending on the number of employees or volunteers who speak it. The community radio station for North-East Dublin Near90fm's "Ar Muin na Muice" programme is broadcast five days a week, and one of their current affairs programmes "Between The Lines" is also broadcast in Irish on occasion. The BBC offers an Irish-language service called called Blas ("a taste").[55] 14% of the population of the Republic of Ireland listen to Irish radio programming daily, 16% listen 2-5 times a week, while 24% listen to Irish programming once a week.

Television

TG4 has offered Irish-speaking young people a forum for youth culture as Gaeilge (in Irish) through rock and pop shows, travel shows, dating games, and even a controversial award-winning soap opera in Irish called Ros na Rún(with 160,000 viewers per week) and comedy-drama Rásaí na Gaillimhe, with 223,000 viewers tuning in on its opening night. In 2007 TG4 reported that overall it "has a share of 3%(800,000 daily viewers) of the national television market".[56] This market share is up from about 1.5% in the late 1990s. TG4 delivers 16 hours a day of television from an annual budget of €35 million, which is widely judged to be relatively efficient. The budget has the full support of all political parties in parliament.[56] TG4 is the most successful and high-profile government initiative for the Irish language for the past fifty years.

Cúla 4 is a children's channel. As of 1 September 2009, a children's channel available on Chorus NTL digital (Channel 602) television with the majority of programmes in Irish, with a range of home-produced and foreign dubbed programmes. Programmes are broadcast Mondays-Sundays from 7am - 10am, then from 2.30pm-7pm.

RTÉ News Now is a 24 hour live news service available on the RTÉ website featuring national and international news. It offers a mix of Irish language, English language and Irish sign language TV news bulletins and political programmes. It broadcasts the following programmes: Cinnlínte Nuachta, Nuacht RTÉ, Nuacht an Lae, Nuacht TG4, Pobal, Timpeall na Tíre and 7 Lá.

Until December 2008 there was an Irish-language daily newspaper Lá Nua, which came out five days a week and had a circulation of several thousand.[57] There is presently a weekly paper, Foinse, formerly published independently and now available as a supplement with the Irish Independent. This gave it a potential readership of 152,000 as of 18 November 2009, though it is likely that only a small percentage would be able to read it with ease. From 2010 on, another weekly newspaper called Gaelscéal will begin publication in cooperation with the Connacht Tribune and EO Teilifís, and will be available on-line.[citation needed] These The Irish News has two pages in Irish every day. The Irish Times had up until recently one article in Irish every week. Now it has several articles with short lists giving the meaning in English of some of the words used. Another paper, Saol, and several magazines are also published in the language: the latter include the internet-based publications Beo[58] and the very contemporary Nós. The immigrants’ magazine Metro Éireann also has articles in Irish every issue, as do local papers throughout the country.

Entertainment

Top 40 Oifigiúil na hÉireann

A company called Digital Audio Productions specialising in all aspects of radio programming has created two very successful Top 40 Oifigiúil na hÉireann and Giotaí brands of Irish-language radio programmes.

Since 2007, Top 40 Oifigiúil na hÉireann (Ireland's Official Top 40) is a new phenomenon, and it has become increasingly popular to hear the Irish Top 40 hits being presented entirely in Irish on what are regarded as English-language radio stations such as:East Coast FM, Flirt FM, Galway Bay FM, LM FM, Midwest Radio, NEAR FM 101.6FM, Newstalk, Red FM, Spin 1038, Spin South West and Wired FM.

Seachtain na Gaeilge & Ceol albums

For decades, too much focus was placed on the importance of Irish traditional music to the detriment of the younger generation, who became disillusioned and felt disenfranchised from the Irish language movement until recently. But young people have taken back their language and have begun to start singing some songs in Irish as part of the Seachtain na Gaeilge campaign which collaborates with up and coming modern Irish musicians to produce songs in Irish. These have become the infamous Ceol '08 albums and the following artists have taken part: Mundy, The Frames, The Coronas, The Corrs, The Walls, Paddy Casey, Kíla, Luan Parle, Gemma Hayes, Bell X1 and comedian/rapper Des Bishop.

Comedy

Dara Ó Briain and Des Bishop are well-known Irish-speaking comedians.[citation needed]

Concerts

Electric Picnic, one of Ireland's most renowned music festivals with 35-40,000 concert goers has an Irish language tent called Puball na Gaeilge which is hosted by DJs from the Dublin-based Irish language radio station Raidió na Life, as well as having well known celebrities from Irish language media, such as Hector Ó hEochagáin, doing sketches and comedy all in Irish and many well known Irish singers.

Religious texts

The Bible has been available in Irish since the 17th century. In 1964 the first Roman Catholic version was produced at Maynooth under the supervision of Professor Pádraig Ó Fiannachta and was finally published in 1981.[59] The Church of Ireland Book of Common Prayer of 2004 is published in both Irish and English.

Irish in English-medium Schools

The Irish language is a compulsory subject in government-funded schools in the Republic of Ireland and has been so since the early days of the state. It is taught as a second language (L2) at second level, to native (L1) speakers and learners (L2) alike.[60] English is offered as a first (L1) language only, even to those who speak it as a second language. The curriculum was reorganised in the 1930s by Father Timothy Corcoran SJ of UCD, who could not speak the language himself.[61] The Irish Government has endeavoured to address the unpopularity of the language by revamping the curriculum at primary school level to focus on spoken Irish. However, at secondary school level, students must analyse literature and poetry, and write lengthy essays, debates and stories in Irish for the (L2) Leaving Certificate examination. The exemption from learning Irish on the grounds of time spent abroad, or learning disability, is subject to Circular 12/96 (primary education) and Circular M10/94 (secondary education) issued by the Department of Education and Science.

The Irish Equality Authority recently questioned the official State practice of awarding 5-10% extra marks to students who take some of their examinations through Irish.[62] The Royal Irish Academy's 2006 conference on "Language Policy and Language Planning in Ireland" found that the study of Irish and other languages is declining in Ireland. The number of schoolchildren studying "higher level" Irish for the Leaving Certificate dropped from 15,719 in 2001 to 14,358 in 2005. To reverse this decline, it was recommended that training and living for a time in a Gaeltacht area should be "compulsory" for teachers of Irish, though this failed to take account of the decline of the language in Gaeltacht areas.[63]

In March 2007, the Minister for Education, Mary Hanafin, announced that more focus would be devoted to the spoken language, and that from 2012, the percentage of marks available in the Leaving Certificate Irish exam would increase from 25% to 40% for the oral component.[64] This increased emphasis on the oral component of the Irish examinations is likely to change the way Irish is examined.[65][66]

Recently the abolition of compulsory Irish has been discussed. In 2005 Enda Kenny, leader of Ireland's main opposition party, Fine Gael, called for the language to be made an optional subject in the last two years of secondary school. Mr Kenny, despite being a fluent speaker himself (and a teacher), stated that he believed that compulsory Irish has done the language more harm than good.

Irish-medium education (Outside Gaeltacht regions)

The extent of their growth is evidenced by the fact that in 1972, outside the Irish-speaking areas, there were only 11 such schools at primary level and five at secondary level, and now there are 170 at primary level[67] and 39 at secondary level.[68] These schools cover approximately 37,800 students (2009), and there is now at least one in each of the 32 traditional counties of Ireland. There are also 4,000 attending preschools outside the Gaeltacht regions.

A remarkable feature of modern Irish education is the rapid growth of a alternative school system in which Irish is the language of instruction. Although this is marked by strong support from the urban professional class, such schools (known as gaelscoileanna at primary level) are also found in disadvantaged areas. Their success is due to limited but very active community support, and they enjoy the advantage of a highly professional administrative infrastructure.[69] .

These schools have a high academic reputation, and attract committed teachers and parents; this in turn has attracted other parents who seek good examination performance at a moderate cost. The result has been termed a system of “positive social selection,” with such schools giving ready access to the tertiary level and commensurate employment. An analysis of “feeder” schools (which supply students to tertiary level institutions) has shown that 22% of the Irish-medium schools sent all their students on to tertiary level, compared to 7% of English-medium schools.[70]

Irish-medium education (Inside Gaeltacht regions)

There are 127 Irish-language primary and 29 secondary schools in the Gaeltacht regions. There are approximately 9,000 pupils at primary level and 3,030 second level students attending these schools. There are also 1,000 attending Irish-language preschools within these areas.[citation needed]

In Gaeltacht areas, the education has been through Irish since the foundation of the State. A certain number of Gaeltacht students are L1 Irish speakers, but even in the Gaeltacht areas the language is taught as an L2 language while English is taught as an L1 language. Professor David Little has commented:

- "..the needs of Irish as L1 at post-primary level have been totally ignored, as at present there is no recognition in terms of curriculum and syllabus of any linguistic difference between learners of Irish as L1 and L2."[60]

With the continued decline of the Gaeltacht, it is expected that urban Irish-medium schools will continue to be vital for the future of the language, though there is no evidence that all graduates of those schools continue to use the language in later life.[citation needed]

Irish colleges

There are 46 summer colleges[citation needed] in the country with approximately 26,000 students attending them each year.[citation needed] Supplementing the formal curriculum, and after the end of the primary (usually from 4th class onwards) and secondary school years, some pupils attend an "Irish college". These programmes are residential Irish language summer courses, and give students the opportunity to be immersed in the language, usually for periods of three weeks over the summer months. Some courses are college based while others are based with host families in Gaeltacht areas under the guidance of a bean an tí. Students attend classes, participate in sports, art, drama, music, go to céilithe and other summer camp activities through the medium of Irish. As with the conventional school set-up The Department of Education establishes the boundaries for class size and qualifications required by teachers.

Northern Ireland

As in the Republic, the Irish language is a minority language in Northern Ireland, known in Irish as [Tuaisceart Éireann] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help).

Attitudes towards the language in Northern Ireland have traditionally reflected the political differences between its two divided communities. The language has been regarded with suspicion by Unionists, who have associated it with the Roman Catholic-majority Republic, and more recently, with the Republican movement in Northern Ireland itself. Erection of public street signs in Irish were effectively banned under laws by the Parliament of Northern Ireland, which stated that only English could be used. Many republicans in Northern Ireland, including Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams, learned Irish while in prison, a development known as the jailtacht.[71] Although the language was taught in Catholic secondary schools (especially by the Christian Brothers), it was not taught at all in the controlled sector, which is mostly attended by Protestant pupils. Irish-medium schools, however, known as gaelscoileanna, were founded in Belfast and Derry, and an Irish-language newspaper called Lá Nua ("New Day") was established in Belfast. BBC Radio Ulster began broadcasting a nightly half-hour programme in Irish in the early 1980s called Blas ("taste, accent"), and BBC Northern Ireland also showed its first TV programme in the language in the early 1990s.

The Ultach Trust was established with a view to broadening the appeal of the language among Protestants, although DUP politicians like Sammy Wilson ridiculed it as a "leprechaun language".[72] Ulster Scots, promoted by many loyalists, was, in turn, ridiculed by nationalists (and even some Unionists) as "a DIY language for Orangemen".[73] According to recent statistics, there is no significant difference between the number of Catholic and Protestant speakers of Ulster Scots in Ulster, although those involved in promoting Ulster Scots as a language are almost always unionist.[citation needed] Ulster Scots is defined in legislation (The North/South Co-operation (Implementation Bodies) Northern Ireland Order 1999) as: the variety of the Scots language which has traditionally been used in parts of Northern Ireland and in Donegal in Ireland.[74]

Irish received official recognition in Northern Ireland for the first time in 1998 under the Good Friday Agreement's provisions on "parity of esteem". A cross-border body known as Foras na Gaeilge was established to promote the language in both Northern Ireland and the Republic, taking over the functions of the previous Republic-only [Bord na Gaeilge] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help). In 2001, the British government ratified the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages in respect to Irish in Northern Ireland. In March 2005, the Irish-language TV service TG4 began broadcasting from the Divis transmitter near Belfast, as a result of an agreement between the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Northern Ireland Office, although so far this is the only transmitter to carry it.

Belfast City Council has designated the Falls Road area (from Milltown Cemetery to Divis Street) as the Gaeltacht Quarter of Belfast, one of the four cultural quarters of the city. There is a growing number of Irish-medium schools throughout Northern Ireland (see picture above).

Under the St Andrews Agreement, the UK Government committed to introduce an Irish Language Act. Although a consultation document on the matter was published in 2007, the restoration of devolved government by the Northern Ireland Assembly later that year meant that responsibility for language transferred from London to Belfast. In October 2007, the then Minister of Culture, Arts and Leisure, Edwin Poots MLA announced to the Assembly that he did not intend to bring forward an Irish language Bill.

Outside Ireland

A limited interest in the Irish language is maintained throughout the English-speaking world among the Irish diaspora and there are active Irish language groups in North American, British, and Australian cities.

North America

The Irish language emigrated to North America along with the Irish people. The Irish language is first mentioned there in the 17th century, and in the 18th century it was particularly strong in Pennsylvania. Immigration from Irish-speaking counties to America was strong throughout the 19th century, particularly after the Famine, and many manuscripts in Irish came with the immigrants.[75] 1881 saw the founding of “An Gaodhal,” the first newspaper largely in Irish. It continued to be published into the 20th century.[76]

Although Irish is one of the lesser spoken European languages of North America, it still has some cultural importance in the northeast United States and in Newfoundland, though in the latter locality no native speakers remain. According to the 2000 Census, 25,661 people in the U.S. speak Irish at home.[77] The equivalent 2005 Census reports 18,815.[78]

The Irish language came to Newfoundland in the late 1600s and was commonly spoken among the Newfoundland Irish until the middle of the 20th century. Today it remains the only place outside of Europe that can claim a unique Irish name (Talamh an Éisc, meaning Land of the Fish). In 2007 a number of Canadian speakers founded the first officially designated "Gaeltacht" outside of Ireland in an area near Kingston, Ontario (see main article Permanent North American Gaeltacht). Despite being called a Gaeltacht, the area has no permanent inhabitants. The site (named Gaeltacht Bhaile na hÉireann) is located in Tamworth, Ontario, and is to be a retreat centre for Irish-speaking Canadians and Americans.[79][80]

Australia

The Irish language reached Australia in 1788, along with English. In the early colonial period Irish was seen as a language of covert opposition used by convicts, and as such was repressed by the colonial authorities.[81] The Irish were a greater proportion of the European population than in any other British colony, and there has been debate about the extent to which Irish was used in Australia.[82] In the light of recent research it seems likely that for much of the 19th century Irish was the second most widely used European language in the country after English, especially since most Irish immigrants came from counties in the west and south-west where Irish was strong (e.g. County Clare and County Galway).[83]

As legal barriers to the integration of the Irish and their descendants into Australian life were progressively removed, English became the language of social advancement. The 2001 census indicated that there were 828 households in the country which used Irish.[84] Individual users are not counted, though one may assume the existence of a minority with some competence in the language, including an increasing number of fluent speakers. The Department of Celtic Studies at the University of Sydney offers courses in both Modern Irish linguistics, Old Irish and Modern Irish language.[85] The University of Melbourne houses a valuable collection of late 19th and early 20th century books and manuscripts in Irish, increasingly used by specialists in the field.[86]

In Australia the language has enjoyed a recent period of modest cultivation, beginning in the seventies and with some public attention being attracted in the interval.[87] There is presently a loose network of Irish learners and users dominated by the Irish Language Association of Australia (Cumann Gaeilge na hAstráile), through which Irish-language classes are run. Week-long courses are available twice a year in the states of Victoria and New South Wales. The Association has won several prestigious prizes (the last in 2009) in a global competition run by Glór na nGael and sponsored by the Irish Department of Foreign Affairs.[88][89]