Winter solstice

| Winter solstice | |

|---|---|

Lawrence Hall of Science visitors observe sunset on day of the winter solstice using the Sunstones II | |

| Also called | Midwinter, DōngZhì, Yule, Şabe Cele/Yalda, Soyal, Şeva Zistanê, Solar New Year, longest night |

| Observed by | Various cultures, ancient and modern |

| Type | Cultural, seasonal, astronomical |

| Significance | Astronomically marks the beginning of shortening nights and lengthening days, interpretation varies from culture to culture, but most hold a recognition of rebirth |

| Celebrations | Festivals, spending time with loved ones, feasting, singing, dancing, fire in the hearth |

| Date | The solstice of winter Between December 21 and December 22 (NH) Between June 20 and June 21 (SH) |

| Related to | Winter festivals and the solstice |

The winter solstice occurs exactly when the Earth's axial tilt is farthest away from the sun at its maximum of 23° 26'. Though the winter solstice lasts only an instant in time, the term is also colloquially used as midwinter or contrastingly the first day of winter to refer to the day on which it occurs. More evident to those in high latitudes, this occurs on the shortest day, and longest night, and the sun's daily maximum position in the sky is the lowest.[1] The seasonal significance of the winter solstice is in the reversal of the gradual lengthening of nights and shortening of days. Depending on the shift of the calendar, the winter solstice occurs on December 21 or 22 each year in the Northern Hemisphere, and June 20 or 21 in the Southern Hemisphere.[2]

Worldwide, interpretation of the event has varied from culture to culture, but most cultures have held a recognition of rebirth, involving holidays, festivals, gatherings, rituals or other celebrations around that time.[3]

Date

In 46 BCE, Julius Caesar in his Julian calendar established December 25 as the date of the winter solstice of Europe (Latin: Bruma). Since then, the difference between the calendar year (365.2500 days) and the tropical year (365.2422 days) moved the day associated with the actual astronomical solstice forward approximately three days every four centuries, arriving to December 12 during the 16th century. In 1582, Pope Gregory XIII decided to restore the exact correspondence between seasons and civil year but, doing so, he did not make reference to the age of the Roman dictator, but to the Council of Nicea of 325, as the period of definition of major Christian feasts. So, the Pope annulled the 10-day error accumulated between the 16th and the 4th century, but not the 3-day one between the 4th AD and the 1st BC century. This change adjusted the calendar bringing the northern winter solstice to around December 22. Yearly, in the Gregorian calendar, the solstice still fluctuates slightly but, in the long term, only about one day every 3000 years.

The figures in the charts show the differences between the Gregorian calendar (Figure 1: using 1 leap year per 4 years) and Persian Jalāli calendar (Figure 2: using the 33-year arithmetic approximation) in reference to the actual yearly time of the winter solstice of the northern hemisphere, the December solstice. The Y axis is "days error" and the X axis is Gregorian calendar years. Each point represents a single date on a given year. The error shifts by about 1/4 day per year, and is corrected by a leap year every 4th year regularly, and in the case of the Persian calendar also one 5 year leap period to complete a 33-year cycle, keeping the Persian winter solstice holiday on the same day every year.

Seasonal position

| event | equinox | solstice | equinox | solstice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| month | March[6] | June[7] | September[8] | December[9] | ||||

| year | day | time | day | time | day | time | day | time |

| 2019 | 20 | 21:58 | 21 | 15:54 | 23 | 07:50 | 22 | 04:19 |

| 2020 | 20 | 03:50 | 20 | 21:43 | 22 | 13:31 | 21 | 10:03 |

| 2021 | 20 | 09:37 | 21 | 03:32 | 22 | 19:21 | 21 | 15:59 |

| 2022 | 20 | 15:33 | 21 | 09:14 | 23 | 01:04 | 21 | 21:48 |

| 2023 | 20 | 21:25 | 21 | 14:58 | 23 | 06:50 | 22 | 03:28 |

| 2024 | 20 | 03:07 | 20 | 20:51 | 22 | 12:44 | 21 | 09:20 |

| 2025 | 20 | 09:02 | 21 | 02:42 | 22 | 18:20 | 21 | 15:03 |

| 2026 | 20 | 14:46 | 21 | 08:25 | 23 | 00:06 | 21 | 20:50 |

| 2027 | 20 | 20:25 | 21 | 14:11 | 23 | 06:02 | 22 | 02:43 |

| 2028 | 20 | 02:17 | 20 | 20:02 | 22 | 11:45 | 21 | 08:20 |

| 2029 | 20 | 08:01 | 21 | 01:48 | 22 | 17:37 | 21 | 14:14 |

How cultures interpret the solstice is varied, since it is sometimes said to astronomically mark either the beginning or middle of a hemisphere's winter. Winter is a subjective term, so there is no scientifically established beginning or middle of winter but the winter solstice itself is clearly calculated to within a second. For Celtic countries, such as Ireland, the calendarical winter season has traditionally begun November 1 on Hallows eve or Samhain. Winter ends and spring begins on Imbolc or Candlemas, which is February 1 or 2. This calendar system of seasons may be based on the length of days exclusively. Most East Asian cultures define the seasons by solar terms, with Dong zhi at the winter solstice as the middle or "extreme" of winter. This system is based on the Sun's apparent height above the horizon at noon. Some midwinter festivals have occurred according to lunar calendars and so took place on the night of Hōku (Hawaiian, the full moon closest to the winter solstice). And many European solar calendar midwinter celebrations still centre upon the night of December 24 leading into the December 25 in the north, which was considered to be the winter solstice upon the establishment of the Julian calendar.[citation needed] In the Jewish Talmud, Teḳufat Tevet, the day of the winter solstice, is recorded as the first day of the "stripping time" or winter season. Persian culture also recognizes it as the beginning of winter.

History and cultural significance

The solstice itself may have been a special moment of the annual cycle of the year even during neolithic times. Astronomical events, which during ancient times controlled the mating of animals, sowing of crops and metering of winter reserves between harvests, show how various cultural mythologies and traditions have arisen. This is attested by physical remains in the layouts of late Neolithic and Bronze Age archaeological sites such as Stonehenge in Britain and Newgrange in Ireland. The primary axes of both of these monuments seem to have been carefully aligned on a sight-line pointing to the winter solstice sunrise (New Grange) and the winter solstice sunset (Stonehenge). Significant in respect of Stonehenge is the fact that the Great Trilithon was erected outwards from the centre of the monument, i.e., its smooth flat face was turned towards the midwinter Sun.[10] The winter solstice may have been immensely important because communities were not certain of living through the winter, and had to be prepared during the previous nine months. Starvation was common in winter between January and April, also known as the famine months. In temperate climates, the midwinter festival was the last feast celebration, before deep winter began. Most cattle were slaughtered so they would not have to be fed during the winter, so it was almost the only time of year when a supply of fresh meat was available. The majority of wine and beer made during the year was finally fermented and ready for drinking at this time. The concentration of the observances were not always on the day commencing at midnight or at dawn, but the beginning of the pre-Romanized day, which falls on the previous eve.[11]

Explanations for parallel traditions

Symbolic

Since the event is seen as the reversal of the Sun's ebbing presence in the sky, concepts of the birth or rebirth of sun gods have been common and, in cultures using winter solstitially based cyclic calendars, the year as reborn has been celebrated with regard to life-death-rebirth deities or new beginnings such as Hogmanay's redding, a New Year cleaning tradition. In Greek mythology, the gods and goddesses met on the winter and summer solstice, and Hades was permitted on Mount Olympus. Also reversal is another usual theme as in Saturnalia's slave and master reversals.

Migration and appropriation

Many outside traditions are often adopted by neighboring or invading cultures. Some historians will often assert that many traditions are directly derived from previous ones rooting all the way back to those begun in the cradle of civilization or beyond, much in a way that correlates to speculations on the origins of languages.

Therapeutic

Even in modern cultures these gatherings are still valued for emotional comfort, having something to look forward to at the darkest time of the year. This is especially the case for populations in the near polar regions of the hemisphere. The depressive psychological effects of winter on individuals and societies are experienced as coldness, tiredness, malaise, and inactivity. This is known as seasonal affective disorder.

Also, insufficient sunlight in the short winter days increases the secretion of melatonin in the body, throwing off the circadian rhythm with longer sleep. Exercise, light therapy, increased negative ion exposure (which can be attained from plants and well ventilated flames, burning wood or beeswax) can reinvigorate the body from its seasonal lull and relieve winter blues by decreasing melatonin secretions, increasing serotonin and temporarily creating a more even sleeping pattern[citation needed].

Midwinter festivals and celebrations occurring on the longest night of the year, often calling for evergreens, bright illumination, large ongoing fires, feasting, communion with close ones, and evening physical exertion by dancing and singing are examples of cultural winter therapies that have evolved as traditions since the beginnings of civilization.[citation needed]

Observances

Direct observation of the solstice by amateurs is difficult because the sun moves too slowly at either solstice to determine its specific day, let alone its instant. Knowledge of when the event occurs has only recently been facilitated to near its instant according to precise astronomical data tracking. It is not possible to detect the actual instant of the solstice (by definition, one can not observe that an object has stopped moving until one makes a second observation in time showing that it has not moved further from the preceding spot, or that it has moved in the opposite direction). Further, to be precise to a single day one must be able to observe a change in azimuth or elevation less than or equal to about 1/60th of the angular diameter of the sun. Observing that it occurred within a two day period is easier, requiring an observation precision of only about 1/16th of the angular diameter of the sun. Thus, many observations are of the day of the solstice rather than the instant.[12] This is often done by watching the sunrise and sunset or vice versa or using an astronomically aligned instrument that allows a ray of light to cast on a certain point around that time.

Before the scientific revolution many forms of observances; astronomical, symbolic or ritualistic, had evolved according to the beliefs of various cultures, many of which are still practiced today. The following is an alphabetical list of observances believed to be directly linked to the winter solstice. For other Winter observances see List of winter festivals.:

A

Amaterasu celebration, Requiem of the Dead (7th century Japan)

In late seventh century Japan, festivities were held to celebrate the reemergence of Amaterasu or Amateras, the sun goddess of Japanese mythology, from her seclusion in a cave. Tricked by the other gods with a loud celebration, she peeks out to look and finds the image of herself in a mirror and is convinced by the other gods to return, bringing sunlight back to the universe. Requiems for the dead were held and Manzai and Shishimai were performed throughout the night, awaiting the sunrise. Aspects of this tradition survive on New Years.[13]

B

Beiwe Festival (Sámi of Northern Fennoscandia)

The Saami, indigenous people of Finland, Sweden and Norway, worship Beiwe, the sun-goddess of fertility and sanity. She travels through the sky in a structure made of reindeer bones with her daughter, Beiwe-Neia, to herald back the greenery on which the reindeer feed. On the winter solstice, her worshipers sacrifice white female animals, and with the meat, thread and sticks, bed into rings with ribbons. They also cover their doorposts with butter so Beiwe can eat it and begin her journey once again.[14]

Brumalia (Roman Kingdom)

Influenced by the Ancient Greek Lenaia festival, Brumalia was an ancient Roman solstice festival honoring Bacchus, generally held for a month and ending December 25. The festival included drinking and merriment. The name is derived from the Latin word bruma, meaning "shortest day" or "winter solstice". The festivities almost always occurred on the night of December 24.

C

In the ancient traditions of the Kalash people of Pakistan, during winter solstice, a demigod returns to collect prayers and deliver them to Dezao, the supreme being. "During this celebrations women and girls are purified by taking ritual baths. The men pour water over their heads while they hold up bread. Then the men and boys are purified with water and must not sit on chairs until evening when goat's blood is sprinkled on their faces. Following this purification, a great festival begins, with singing, dancing, bonfires, and feasting on goat tripe and other delicacies".[15]

Christmas or Christ's Mass is one of the most popular Christian celebrations as well as one of the most globally recognized midwinter celebrations. Christmas is the celebration of the birth of the Christian Deity God Incarnate or Messiah, Jesus Christ. The birth is observed on December 25, which was the Roman winter solstice upon establishment of the Julian Calendar.[16] Christian churches recognized folk elements of the festival in various cultures within the past several hundred years, allowing much of the folklore and traditions of local pagan festivals to be appropriated. So today, the old festivals such as Jul, Коледа and Karácsony, are still celebrated in many parts of Europe, but the Christian Nativity is now often representational as the meaning behind the holiday. This is why Yule and Christmas are considered interchangeable in Anglo–Christendom. Universal activities include feasting, Midnight Masses and singing Christmas carols about the Nativity. Good deeds and gift giving in the tradition of St. Nicholas by not admitting to being the actual gift giver is also observed by some countries. Many observe the holiday for twelve days leading up to the Epiphany.

D

Deygān, Maidyarem (Zoroastrian)

Theologically, Maidyarem is associated with Vahman, the Amesha Spenta (or Holy Immortal) who created the primal bull, and all cattle, and is associated with good plans and intentions. Maidyarem is celebrated in Dey, the tenth month of the Zoroastrian calendar, from the sixteenth (Mihr) to the twentieth (Bahram) day. There are also speculations that by the Persian calendar many celebrated on the last day of the Persian month Azar, the longest night of the year, when the forces of Ahriman are assumed to be at the peak of their strength. The next day, the first day of the month Dey, known as khoram ruz or khore ruz (the day of sun) belongs to God (Ahura Mazda). Since the days are getting longer and the nights shorter, this day marks the victory of Sun over the darkness. The occasion was celebrated in the ancient Persian Deygan Festival dedicated to Ahura Mazda, and Mithra on the first day of the month Dey.[17]

Dōngzhì Festival (East Asian Cultural Sphere and Mahayana Buddhist)

The Winter Solstice Festival or The Extreme of Winter (Chinese and Japanese: 冬至; Korean: 동지; Vietnamese: Đông chí) (Pinyin: Dōng zhì), (Rōmaji: Tōji), (Romaja:Dongji) is one of the most important festivals celebrated by the Chinese and other East Asians during the dongzhi solar term on or around December 21 when sunshine is weakest and daylight shortest; i.e., on the first day of the dongzhi solar term. The origins of this festival can be traced back to the yin and yang philosophy of balance and harmony in the cosmos. After this celebration, there will be days with longer daylight hours and therefore an increase in positive energy flowing in. The philosophical significance of this is symbolized by the I Ching hexagram fù (復, "Returning"). Traditionally, the Dongzhi Festival is also a time for the family to get together. One activity that occurs during these get togethers (especially in the southern parts of China and in Chinese communities overseas) is the making and eating of Tangyuan (湯圓, as pronounced in Cantonese; Mandarin Pinyin: Tāng Yuán) or balls of glutinous rice, which symbolize reunion. In Korea, similar balls of glutinous rice (Korean: 새알심) (English pronunciation:Saealsim), is prepared in a traditional porridge made with sweet red bean (Korean: 팥죽)(English pronunciation:Patjook). Patjook was believed to have a special power and sprayed around houses on winter solstice to repel sinister spirits. This practice was based on a traditional folk tale, in which the ghost of a man that used to hate patjook comes haunting innocent villagers on the winter solstice.

G

Goru is the (December) winter solstice ceremony of the Pays Dogon of Mali. It is the last harvest ritual and celebrates the arrival of humanity from the sky god, Amma, via Nommo inside the Aduno Koro, or the "Ark of the World".[18]

H

Hogmanay (Scotland)

The New Years Eve celebration of Scotland is called Hogmanay. The name derives from the old Scots name for Yule gifts of the Middle Ages. The early Hogmanay celebrations were originally brought to Scotland by the invading and occupying Norse who celebrated a solstitial new year (England celebrated the new year on March 25). In 1600, with the Scottish application of the January 1 New year and the church's persistent suppression of the solstice celebrations, the holiday traditions moved to December 31. The festival is still referred to as the Yules by the Scots of the Shetland Islands who start the festival on December 18 and hold the last tradition (a Troll chasing ritual) on January 18. The most widespread Scottish custom is the practice of first-footing which starts immediately after midnight on New Years. This involves being the first person (usually tall and dark haired) to cross the threshold of a friend or neighbor and often involves the giving of symbolic gifts such as salt (less common today), coal, shortbread, whisky, and black bun (a fruit pudding) intended to bring different kinds of luck to the householder. Food and drink (as the gifts, and often Flies cemetery) are then given to the guests.[19]

I

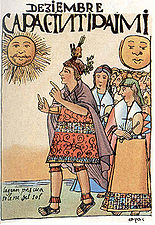

The Inti Raymi or Festival of the Sun was a religious ceremony of the Inca Empire in honor of the sun god Inti. It also marked the winter solstice and a new year in the Andes of the Southern Hemisphere. One ceremony performed by the Inca priests was the tying of the sun. In Machu Picchu there is still a large column of stone called an Intihuatana, meaning "hitching post of the sun" or literally for tying the sun. The ceremony to tie the sun to the stone was to prevent the sun from escaping. The Spanish conquest, never finding Machu Picchu, destroyed all the other intihuatana, extinguishing the sun tying practice. The Catholic Church managed to suppress all Inti festivals and ceremonies by 1572. Since 1944 a theatrical representation of the Inti Raymi has been taking place at Sacsayhuamán (two km. from Cusco) on June 24 of each year, attracting thousands of local visitors and tourists. The Monte Alto culture may have also had a similar tradition.[20][21]

J

Junkanoo, John Canoe, Dzon'ku 'Nu (West Africa, Bahamas, Jamaica, 19th-century North Carolina, Virginia)

Junkanoo, in The Bahamas, Junkunno or Jonkanoo, in Jamaica, is a fantastic masquerade, parade and street festival, suspected to be derived from either Dzon'ku 'Nu (tr: Witch-doctor) of the West African Papaws, an Ewe people[22] or Njoku Ji, an Alusi (Igbo: deity) of the Igbo people.[23] It is traditionally performed through the streets towards the end of December, and involves participants dressed in a variety of fanciful costumes, such as the Cow Head, the Hobby Horse, the Wild Indian, and the Devil. The parades are accompanied by bands usually consisting of fifes, drums, and coconut graters used as scrapers, and Jonkanoo songs are also sung. A similar practice was once common in coastal North Carolina, where it was called John Canoe, John Koonah, or John Kooner. John Canoe was likened to the wassailing tradition of medieval Britain. John Canoe was interpreted by many Euro-Americans to bear strong resemblance to the social inversion rituals that marked the ancient Roman celebration of Saturnalia.

K

Karachun (Ancient Western Slavic)

Karachun, Korochun or Kračún was a Slavic holiday similar to Halloween as a day when the Black God and other evil spirits were most potent. It was celebrated by Slavs on the longest night of the year. On this night, Hors, symbolising the old sun, becomes smaller as the days become shorter in the Northern Hemisphere, and dies on December 22nd, the December solstice. He is said to be defeated by the dark and evil powers of the Black God. In honour of Hors, the Slavs danced a ritual chain-dance which was called the horo. Traditional chain-dancing in Bulgaria is still called horo. In Russia and Ukraine, it is known as khorovod. On December 23rd Hors is resurrected and becomes the new sun, Koleda. On this day, Western Slavs burned fires at cemeteries to keep their departed loved ones warm, organized dinings in the honor of the dead so as they would not suffer from hunger and lit wooden logs at local crossroads.

Koleda, Коляда, Sviatki, Dazh Boh (Ancient Eastern Slavic and Sarmatian)

This article needs attention from an expert in Russia. Please add a reason or a talk parameter to this template to explain the issue with the article. (November 2008) |

In ancient Slavonic cultures, the festival of Kaleda began at Winter Solstice and lasted for ten days. In Russia, this festival was later applied to Christmas Eve but most of the practices were lost after the Soviet Revolution. Each family made a fire in their hearth and invited their personal household gods to join in the festivities. Children disguise themselves on evenings and nights and as Koledari[disambiguation needed], visited houses and sang wishes of good luck, like Shchedryk, to hosts. As a reward, they were given little gifts, a tradition called Kolyadovanie, much like the old wassailing or mummers Tradition.[24][25]

L

For an unknown period, Lá an Dreoilín or Wren day has been celebrated in Ireland, the Isle of Man and Wales on December 26. Crowds of people, called wrenboys, take to the roads in various parts of Ireland, dressed in motley clothing, wearing masks or straw suits and accompanied by musicians supposedly in remembrance of the festival that was celebrated by the Druids. Previously the practice involved the killing of a wren, and singing songs while carrying the bird from house to house, stopping in for food and merriment.

Lenæa (Ancient and Hellenistic Greece)

In the Aegean civilizations, the exclusively female midwinter ritual, Lenaea or Lenaia, was the Festival of the Wild Women. In the forest, a man or bull representing the god Dionysus was torn to pieces and eaten by Maenads. Later in the ritual a baby, representing Dionysus reborn, was presented. Lenaion, the first month of the Delian calendar, derived its name from the festival's name. By classical times, the human sacrifice had been replaced by that of a goat, and the women's role had changed to that of funeral mourners and observers of the birth. Wine miracles were performed by the priests, in which priests would seal water or juice in a room overnight and the next day they would have turned into wine. The miracle was said to have been performed by Dionysus and the Lenaians. By the 5th century BC the ritual had become a Gamelion festival for theatrical competitions, often held in Athens in the Lenaion theater. The festival influenced the ancient Roman Brumalia.[26][27][28]

Lohri (India)

In Punjab, the winter solstice is celebrated as Lohri. Lohri is of Punjabi folk religion origin [29] It finds no mention in the Hindu Puranas but has over time been twinned with the Hindu festival of Makar Sankranti which is celebrated a day after Lohri and is known as Maghi. For this reason, Lohri is not actually celebrated on the winter solstice but at the end of the month, Paush.

Lucia, Feast of St. Lucy (Ancient Swedish, Scandinavian Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox)

Lucia or Lussi Night happens on December 13, what was supposed to be the longest night of the year. The feast was later appropriated by the Catholic Church in the 16th century as St. Lucy's Day. It was believed in some folklore of Sweden that if people, particularly children, did not carry out their chores, the female demon, the Lussi or Lucia die dunkle would come to punish them.[30]

M

Makara Sankranti, celebrated at the beginning of Uttarayana उत्तरायण, is the only Hindu festival which is based on the celestial calendar rather than the lunar calendar. The zodiac having drifted from the solar calendar has caused the festival to now occur in mid-January (see precession of equinoxes). In Tamil Nadu it is celebrated as the festival of Pongal. The day before Pongal, the last day of the previous year, they celebrate Bhogi. In Assam it is called Magh Bihu (the First day of Magh), in Punjab Maghi and in Hindi speaking states and Maharshtra it is observed as Makar Sankranti and is celebrated by exchanging balls of sesame candy (Til Gur) and requesting each other to be as sweet as the candy balls for the next year. It is called Makara Sankrant because the sun enters the zodiacal sign of Capricorn on 14 January (Makar meaning Capricorn). It is celebrated with much pomp in Andhra Pradesh, where the festival is celebrated for three days and is more of a cultural festival than an auspicious day as in other parts of India. In some parts of India, the festival is celebrated by taking dips in the Ganges or another river and offering water to the Sun god. The dip is said to purify the self and bestow punya. In many states, mainly in Gujarat, families fly bright colorful kites from their roofs all day and into the night. It is a form of celebrating and welcoming the longer days. It is also very common to feed grass to the cows on this day. In Assam on Bihu Eve or Uruka families build house-like structures called bhelaghar and separate large bhelaghar are built by the community as a whole. Different sorts of twine are tied around fruit trees. Traditionally, fuel is stolen for the final ceremony, when all the bhelaghar are burned. Their remains are then placed at the fruit trees. Special puja is offered as a thanksgiving for good harvest. Since the festival is celebrated in midwinter, the foods prepared for this festival are such that they keep the body warm and give high energy. Laddu of til made with jaggery is specialty of the festival.[31]

Maruaroa o Takurua, (New Zealand, Maori)

Occurring June 20 – June 22 the Maruaroa o Takurua is seen by the New Zealand Maori as the middle of the winter season. It follows directly after the rise of Matariki (Pleiades) which marked the beginning of the New Year and was said to be when the Sun turned from his northern journey with his winter-bride Takurua (the star Sirius) and began his journey back to his Summer-bride Hineraumati.

Meán Geimhridh, Celtic Midwinter (Celtic, Ancient Welsh, Neodruidic)

Meán Geimhridh (Irish tr: midwinter) or Grianstad an Gheimhridh (Ir tr: winter solstice) is a name sometimes used for hypothetical midwinter rituals or celebrations of the Proto-Celtic tribes, Celts, and late Druids. In Ireland's calendars, the solstices and equinoxes all occur at about midpoint in each season. The passage and chamber of Newgrange (Pre-Celtic or possibly Proto-Celtic 3,200 BC), a tomb in Ireland, are illuminated by the winter solstice sunrise. A shaft of sunlight shines through the roof box over the entrance and penetrates the passage to light up the chamber. The dramatic event lasts for 17 minutes at dawn from the 19th to the 23rd of December. The point of roughness is the term for the winter solstice in Wales which in ancient Welsh mythology, was when Rhiannon gave birth to the sacred son, Pryderi. In England, during the 18th century, there was a revival of interest in Druids. Today, amongst Neo-druids, Alban Arthan (Welsh tr. light of winter but derived from Welsh poem, Light of Arthur) is celebrated on the winter solstice with a ritualistic festival, and gift giving to the needy.

Midvinterblót (Swedish folk religion)

In Sweden and many surrounding parts of Europe, polytheistic tribes celebrated a Midvinterblot or mid-winter-sacrifice, featuring both animal and human sacrifice. The blót was performed by goði, or priests, at certain cult sites, most of which have churches built upon them now. Midvinterblot paid tribute to the local gods, appealing to them to let go winter's grip. The folk tradition was finally abandoned by 1200, due to missionary persistence.

Midwinter (Antarctica)

In research stations throughout Antarctica, Midwinter is widely celebrated as a way to mark the fact that the people who winter-over just went through half their turn of duty. Depending on the station the celebrations can last from a day to a week and are typically marked by parties, team games, redecoration of the premises and days off work. Note, however, that the Northern Hemisphere winter solstice of Dec. 21 is actually the summer solstice in Antarctica; the Antarctic midwinter celebration is held in June.[32]

Modranicht, Modresnach (Germanic)

Mōdraniht was a Germanic feast. It was believed that dreams on this night foretold events in the upcoming year. By 730, it was thought by Bede to have been observed by the Anglo-Saxons on the eve of the winter solstice. After the reemergence of Christmas in Britain Mothers Night was recognized by many as one of the Twelve Days of Christmas.[33][34]

Mummer's Day referencing the animist garbs, or Darkie Day referencing the soot facing ritual, is an ancient Cornish midwinter celebration that occurs every year on December 26 and New Year's Day in Padstow, Cornwall. It was originally part of the pagan heritage of midwinter celebrations that were regularly celebrated all over Cornwall where people would guise dance and disguise themselves by blackening up their faces or wearing masks. In Penzance the festival has been given the name Montol believing it to be the Celtic Cornish word for Winter Solstice.

P

Early Germans (c.500–1000) considered the Norse goddess, Hertha or Bertha to be the goddess of light, domesticity and the home. They baked yeast cakes shaped like shoes, which were called Hertha's slippers, and filled with gifts. "During the Winter Solstice houses were decked with fir and evergreens to welcome her coming. When the family and serfs were gathered to dine, a great altar of flat stones was erected and here a fire of fir boughs was laid. Hertha descended through the smoke, guiding those who were wise in saga lore to foretell the fortunes of those persons at the feast".[35] There are also darker versions of Perchta which terrorize children along with Krampus. Many cities had practices of dramatizing the gods as characters roaming the streets. These traditions have continued in the rural regions of the Alps, and various similar traditions, such as Wren day, survived in the Celtic nations until recently. This is commonly used in Holland.

R

Rozhanitsa Feast (12th century Eastern Slavic Russian)

In twelfth century Russia, the eastern Slavs worshiped the winter mother goddess, Rozhnitsa, offering bloodless sacrifices like honey, bread and cheese. Bright colored winter embroideries depicting the antlered goddess were made to honor the Feast of Rozhanitsa in late December. And white, deer-shaped cookies were given as lucky gifts. Some Russian women continued the observation of these traditions into the 20th century.[36]

S

Shab-e Chelleh, یلدا , Yaldā (2nd millennium BC Persian, Iranian)

Derived from a pre-Zoroastrian festival, Shab-e Chelleh is celebrated on the eve of the first day of winter in the Persian calendar, which always falls on the solstice. Yalda is the most important non-new-year Iranian festival in modern-day Iran and it has been long celebrated in Iran by all ethnic/religious groups. According to Persian mythology, Mithra was born at the end of this night after the long-expected defeat of darkness against light. "Shab-e Chelleh" is now an important social occasion, when family and friends get together for fun and merriment. Usually families gather at their elders' homes. Different kinds of dried fruits, nuts, seeds and fresh winter fruits are consumed. The presence of dried and fresh fruits is reminiscence of the ancient feasts to celebrate and pray to the deities to ensure the protection of the winter crops. Watermelons, persimmons and pomegranates are traditional symbols of this celebration, all representing the sun. It used to be customary to stay awake Yalda night until sunrise eating, drinking, listening to stories and poems, but this is no longer very common as most people have things to do on the next day. During the early Roman Empire many Syrian Christians fled from persecution into the Sassanid Empire of Persia, introducing the term Yaldā, meaning birth, causing Shab-e Yaldā to became synonymous with Shab-e Chelleh. Although both terms are used interchangeably, Chelleh is more commonly accepted for this occasion.[17]

Sanghamitta Day (Buddhist)

Sanghamitta is in honor of the Buddhist nun who brought a branch of the Bodhi tree to Sri Lanka where it has flourished for over 2,000 years.

Saturnalia, Chronia (Ancient Greek, Roman Republic)

Originally celebrated by the ancient Greeks as Kronia, the festival of Cronus, Saturnalia was the feast at which the Romans commemorated the dedication of the temple of Saturn, which originally took place on 17 December, but expanded to a whole week, up to 23 December. A large and important public festival in Rome, it involved the conventional sacrifices, a couch set in front of the temple of Saturn and the untying of the ropes that bound the statue of Saturn during the rest of the year. Besides the public rites there were a series of holidays and customs celebrated privately. The celebrations included a school holiday, the making and giving of small presents (saturnalia et sigillaricia) and a special market (sigillaria). Gambling was allowed for all, even slaves during this period. The toga was not worn, but rather the synthesis, i.e., colorful, informal "dinner clothes" and the pileus (freedman's hat) was worn by everyone. Slaves were exempt from punishment, and treated their masters with disrespect. The slaves celebrated a banquet before, with, or served by the masters. Saturnalia became one of the most popular Roman festivals which led to more tomfoolery, marked chiefly by having masters and slaves ostensibly switch places, temporarily reversing the social order. In Greek and Cypriot folklore it was believed that children born during the festival were in danger of turning into Kallikantzaroi which come out of the Earth after the solstice to cause trouble for mortals. Some would leave colanders on their doorsteps to distract them until the sun returned.

Şeva Zistanê (Kurdish)

The Night of Winter (Kurdish: Şeva Zistanê) is an unofficial holiday celebrated by communities throughout the Kurdistan region in the Middle East. The night is considered one of the oldest holidays still observed by modern Kurds and was celebrated by ancient tribes in the region as a holy day. The holiday falls every year on the winter solstice. Since the night is the longest in the year, ancient tribes believed that it was the night before a victory of light over darkness and signified a rebirth of the sun. The sun plays an important role in several ancient religions still practiced by some Kurds in addition to its importance in Zoroastrianism.

In modern times, communities in the Kurdistan region still observe the night as a holiday. Many families prepare large feasts for their communities and the children play games and are given sweets in similar fashion to modern-day Halloween practices.

Sol Invictus Festival (3rd century Roman Empire)

Sol Invictus ("the undefeated Sun") or, more fully, Deus Sol Invictus ("the undefeated sun god") was a religious title that allowed several solar deities to be worshipped collectively, including Elah-Gabal, a Syrian sun god; Sol, the god of Emperor Aurelian; and Mithras, a soldiers' god of Persian origin.[37] Emperor Elagabalus (218–222) introduced the festival of the birth of the Unconquered Sun (or Dies Natalis Solis Invicti) to be celebrated on December 25, and it reached the height of its popularity under Aurelian, who promoted it as an empire-wide holiday.[38] With the growing popularity of the Christianity, Jesus of Nazareth came to be given much of the recognition previously given to a sun god, thereby including Christ in the tradition.[39] This was later condemned by the early Catholic Church for associating Christ with pagan practices.[citation needed]

Soyal (Zuni and Hopi of North America)

Soyalangwul is the winter solstice ceremony of the Zuni and the Hopitu Shinumu, "The Peaceful Ones," also known as the Hopi Indians. It is held on December 21, the shortest day of the year. The main purpose of the ritual is to ceremonially bring the sun back from its long winter slumber. It also marks the beginning of another cycle of the Wheel of the Year, and is a time for purification. Pahos (prayer sticks) are made prior to the Soyal ceremony, to bless all the community, including their homes, animals, and plants. The kivas (sacred underground ritual chambers) are ritually opened to mark the beginning of the Kachina season.[40][41]

W

We Tripantu (Mapudungun tr: new sunrise) is the conclusion of the Mapuche New Year that takes place between June 21 and June 24 in the Gregorian calendar.[42] It is the Mapuche's equivalent to the Inti Raymi. The ancestral incertidubre stayed up throughout the year's longest night with anxiety that the next day would not come. After three days it became clear that the winter was diminishing. The Pachamama (Quechua tr: Mother Earth), Nuke Mapu (uke' Mapu) begins to bloom fertilized by Sol[disambiguation needed], from the Andean heights to the southern tip. Antu (Pillan), Inti (Aymara), or Rapa[disambiguation needed] (rapanui) Sol, the sun starts to come back to earth, after the longest night of the year: it's winter Solstice. Todo start to bloom again.[43]

Y

Yule, Jul, Jól, Joul, Joulu, Jõulud, Géol, Geul (Viking Age, Northern Europe, and Germanic cultures)

Originally the name Giuli signified a 60 day tide beginning at the lunar midwinter of the late Scandinavian Norse and Germanic tribes. The arrival of Juletid thus came to refer to the midwinter celebrations. By the late Viking Age, the Yule celebrations came to specify a great solstitial Midwinter festival that amalgamated the traditions of various midwinter celebrations across Europe, like Mitwinternacht, Modrasnach, Midvinterblot, and the Teutonic solstice celebration, Feast of the Dead. A documented example of this is in 960, when King Håkon of Norway signed into law that Jul was to be celebrated on the night leading into December 25, to align it with the Christian celebrations. For some Norse sects, Yule logs were lit to honor Thor, the god of thunder. Feasting would continue until the log burned out, three or as many as twelve days. The indigenous lore of the Icelandic Jól continued beyond the Middle Ages, but was condemned when the Reformation arrived. The celebration continues today throughout Northern Europe and elsewhere in name and traditions, for Christians as representative of the nativity of Jesus on the night of December 24, and for others as a cultural winter celebration on the 24th or for some, the date of the solstice.[44][45]

Jul (Germanic Neopaganism)

- In Germanic Neopagan sects, Yule is celebrated with gatherings that often involve a meal and gift giving. Further attempts at reconstruction of surviving accounts of historical celebrations are often made, a hallmark being variations of the traditional. However it has been pointed out that this is not really reconstruction as these traditions never died out – they have merely removed the Christian elements from the celebration and replaced the event at the solstice.

- The Icelandic Ásatrú and the Asatru Folk Assembly in the US recognize Jól or Yule as lasting for 12 days, beginning on the date of the winter solstice.[46]

Yule (Wiccan)

- In Wicca, a form of the holiday is observed as one of the eight solar holidays, or Sabbat. In most Wiccan groups, or covens, this holiday is celebrated as the rebirth of the Great God, who is viewed as the newborn solstice sun. Although the name Yule has been appropriated from Germanic and Norse paganism, elements of the celebration itself are of modern origin.

Z

Zagmuk, Sacaea (Ancient Mesopotamia, Sumerian, Babylonian)

Adapting the Egyptian Osiris Celebrations, the Babylonians held the annual renewal or new year celebration, the Zagmuk Festival. It lasted 10 days overlapping either the winter solstice or vernal equinox in its center peak. It was a festival held in observation of the sun god Marduk's battle over darkness. The Babylonians held both land and river parades. Sacaea, as Berossus referred to it, had festivals characterized with a subversion of order leading up to the new year. Masters and slaves interchanged, a mock king was crowned and masquerades clogged the streets. This has been a suggested precursor to the Festival of Kronos, Saturnalia and possibly Purim.[47][48]

In ancient Latvia, Ziemassvētki, meaning winter festival, was celebrated on December 21 as one of the two most important holidays, the other being Jāņi. Ziemassvētki celebrated the birth of Dievs, the highest god of Latvian mythology. The two weeks before Ziemassvetki are called Veļu laiks, the "season of ghosts." During the festival, candles were lit for Dieviņš and a fire kept burning until the end, when its extinguishing signaled an end to the unhappiness of the previous year. During the ensuing feast, a space at the table was reserved for Ghosts, who was said to arrive on a sleigh. During the feast, certain foods were always eaten: bread, beans, peas, pork and pig snout and feet. Carolers (Budeļi) went door to door singing songs and eating from many different houses. The holiday was later adapted by Christians in the middle ages. It is now celebrated on the 24th, 25th and 26 December and largely recognized as both a Christian and secular cultural observance. Lithuanians of the Romuva religion continue to celebrate a variant of the original polytheistic holiday.

See also

- Burning of the Clocks

- Effect of sun angle on climate

- Festival of Lights

- Festive ecology

- Festivus

- Halcyon days

- Hanukkah

- HumanLight

- Kwanzaa

- List of winter festivals

- Midsummer

- Midwinter Christmas

- New Years

- Pongal

- Solstice

Sources

- ^ An Introduction to Physical Science, 12th Ed., James Shipman, Jerry D. Wilson, Aaron Todd, Section 15.5, p 423, ISBN 978-0618926961, 2007.

- ^ solstice. (2009). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved May 13, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online Britannica.com

- ^ ReligiousTolerance.org

- ^ Astronomical Applications Department of USNO. "Earth's Seasons - Equinoxes, Solstices, Perihelion, and Aphelion". Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- ^ "Solstices and Equinoxes: 2001 to 2100". AstroPixels.com. 20 February 2018. Retrieved 21 December 2018.

- ^ Équinoxe de printemps entre 1583 et 2999

- ^ Solstice d’été de 1583 à 2999

- ^ Équinoxe d’automne de 1583 à 2999

- ^ Solstice d’hiver

- ^ Johnson, Anthony, Solving Stonehenge: The New Key to an Ancient Enigma. (Thames & Hudson, 2008) pp. 252–253

- ^ An Ancient Holiday History Channel

- ^ SolsticeAmateur.com

- ^ University of Connecticut

- ^ School of the Seasons

- ^ Madsen, Loren. Despite Everything Davka.org

- ^ "Christmas", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913.

- ^ a b The Iranian, History

- ^ New York Metropolitan Museum

- ^ UK History

- ^ Mostrey, Dimitri InfoPeru.com

- ^ Minnesota University

- ^ Melanet.com

- ^ Douglas, Chambers B. (2005). Murder at Montpelier: Igbo Africans in Virginia. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 182. ISBN 1-578-06706-5.

- ^ Winter solstice Adventure Calendar

- ^ Koleda

- ^ Dies Alcyoniae: The Invention of Bellini's Feast of the Gods, by Anthony Colantuono College Art Association, Inc. The Art Bulletin. 1991. Vol. 73, No. 2, p. 246

- ^ Correspondences between the Delian and Athenian Calendars in the Years 433 and 432 B. C., by Allen B. West. American Journal of Archaeology. 1934. Vol.38, No. 1, p.9

- ^ The Miracle of the Wine at Dionysos' Advent; On the Lenaea Festival, by J. Vürtheim The Classical Quarterly, 1920. Vol. 14, No. 2, p.94

- ^ Telegraphindia.com, 24/01/2004 Kushwant Singh The Times

- ^ Griffith University, The Centre for Public Cultures and Ideas

- ^ Margaret Read MacDonald (1992). The Folklore of World Holidays. pp. Chapter: circa December 21.

- ^ Dome C winterover

- ^ Jones, Prudence and Pennick, Nigel. A History of Pagan Europe. Routledge; NY, NY (1997) pp.122–125.

- ^ Internet Sacred Texts Archive

- ^ Hottes, Alfred Carl, 1001 Christmas Facts and Fancies, NY: De La Mare, 1937.

- ^ Kelly, Mary B. Goddesses and Their Offspring, NY: Binghamton (1990)

- ^ Newadvent.org, The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913.

- ^ "Sol," Encyclopædia Britannica, Chicago (2006).

- ^ New Catholic Encyclopedia, "Christmas"

- ^ Bahti, Tom. "Southwestern Indian Ceremonials". KC Publications (1970) p36–40.

- ^ Ausbcomp.com, Hopi: The Real Thing

- ^ AtinaChile.cl (We tripantu o año nuevo mapuche)

- ^ Pascual Coña: Memorias de un cacique mapuche. Santiago (Chile): Instituto de Investigación en Reforma Agraria (2.ª edición), abril de 1973.

- ^ Jones, Prudence & Pennick, Nigel. A History of Pagan Europe. Routledge; NY, NY (1997) pp.122-125.

- ^ Samuels, Brian. Aspects of Australian Folklife

- ^ Asatru Folk Assembly

- ^ Ruano, Teresa Sacaea-Saturnalia. Candlegrove.com

- ^ Morrison, Dorothy. Yule: A Celebration of Light and Warmth. Llewellyn Publications (2000)