Nagorno-Karabakh

Nagorno-Karabakh Լեռնային Ղարաբաղ , Leṙnayin ĠarabaġTemplate:Hy icon Dağlıq Qarabağ / Yuxarı Qarabağ Template:Az icon Нагорный Карабах, Nagorny KarabakhTemplate:Ru icon | |

|---|---|

The borders of the former Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast | |

| Area | |

• Total | 4,400 km2 (1,700 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2006 estimate | 138,000 |

• Density | 29/km2 (75.1/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+4 |

• Summer (DST) | +5 |

| Driving side | right |

Nagorno-Karabakh is a landlocked region in the South Caucasus, lying between Lower Karabakh and Zangezur and covering the southeastern range of the Lesser Caucasus mountains, which corresponds to the eastern part of the Armenian Highland. [1]

Most of the region is governed by the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic (usually abbreviated as NKR), a de facto independent but unrecognized state established on the basis of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast of the Soviet Union's Azerbaijan SSR and populated mainly by ethnic Armenians. While the region's both interim and final international status remains so far unsettled, there are international organizations, governments, NGOs and single politicians who recognize it as part of Azerbaijan. Since the end of the Nagorno-Karabakh War in 1994, representatives of the governments of Armenia and Azerbaijan have been holding peace talks mediated by the OSCE Minsk Group on the region's final status.

If defined solely within the administrative borders of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, Nagorno-Karabakh has an area of 4,400 square kilometres (1,700 sq mi). However, Nagorno-Karabakh's Constitution has a larger territorial definition of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, and includes some territories of Azerbaijan that NKR presently controls, as well as the the district of Shahumian, and the rural community of Getashen. [2]

Name

The original, historical and most enduring name for Nagorno-Karabakh is Artsakh (Armenian: Արցախ), which is used mostly by Armenians and designates the 10th province of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia.[3] As a political and geographical term Artsakh was used continuously throughout the Middle Ages and modern times.[4][5][6] In Urartian inscriptions (9th–7th centuries BC), the name Urtekhini is used for the region.[7] Ancient Greek sources called the area Orkhistene.[8] Both Urtekhini and Orkhistene are thought to be phonetic variants of the word Artsakh.[9] In the high Middle Ages, the entire region was often called Khachen, after the name of Artsakh's largest and most politically significant district.[10] The name “Khachen” originated from Armenian word khach which means “cross”.[11]

The term Nagorno-Karabakh is a modern construct.[14] The word Nagorno- is a Russian attributive adjective, derived from the adjective nagorny (нагорный), which means "highland". The Azerbaijani name of the region includes similar adjectives "dağlıq" (mountainous) or "yuxarı" (upper). Such words are not used in Armenian name, but appeared in the official name of the region during the Soviet era as Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast. Other languages apply their own wording for mountainous, upper, or highland; for example, the official name used by the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic in France is Haut-Karabakh, meaning "Upper Karabakh".

The word Karabakh is generally held to originate from Turkic and Persian, and literally means "black garden".[15][16] The name first appears in Georgian and Persian sources of the 13th and 14th centuries.[16] Karabagh is an acceptable alternate spelling of Karabakh, and also denotes a kind of patterned rug originally produced in the area.[17]

In an alternative theory proposed by Bagrat Ulubabyan the name Karabakh has a Turkic-Armenian origin, meaning "Greater Baghk" (Armenian: Մեծ Բաղք), a reference to Ktish-Baghk (later: Dizak), one of the principalities of Artsakh under the rule of the Aranshahik dynasty, which held the throne of the Kingdom of Syunik in the 11th–13th centuries and called itself the "Kingdom of Baghk".[3]

The names for the region in the various local languages all translate to "mountainous Karabakh", or "mountainous black garden":

- Armenian: Լեռնային Ղարաբաղ, transliterated Leṙnayin Ġarabaġ

- Azerbaijani: Dağlıq Qarabağ (mountainous Karabakh) or Yuxarı Qarabağ (upper Karabakh)

- Russian: Нагорный Карабах, transliterated Nagornyy Karabakh or Nagornyi Karabah

History

Early history

Nagorno-Karabakh falls within the lands occupied by peoples known to modern archaeologists as the Kura-Araxes culture, who lived between the two rivers Kura and Araxes.

It is thought that the original population of the region consisted of various autochthonous and migrant tribes.[22] According to the American scholar Robert H. Hewsen, these primordial tribes were "certainly not of Armenian origin", and "although certain Iranian peoples must have settled here during the long period of Persian and Median rule, most of the natives were not even Indo-Europeans".[22]

However, relying on information provided by the 5th century Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi, other Western authors argued—and Hewsen himself indicated later—that these peoples could have been added to the Kingdom of Armenia much earlier, in the 4th century BC.[23]

Overall, from around 180 BC and up until the 4th century AD — before becoming part of the Armenian Kingdom again, in 855 — the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh remained part of the united Armenian Kingdom as the province of Artsakh.[24][25]

Armenians have lived in the Karabakh region since Roman times: Strabo states that, by the second or first century BC, the entire population of Greater Armenia—Artsakh and Utik included—spoke Armenian,[26][27] though this does not mean that its population consisted exclusively of ethnic Armenians.[28]

Tigran the Great, King of Armenia, (ruled 95–55 BC), founded in Artsakh one of four cities named “Tigranakert” after himself.[13][29] The ruins of the ancient Tigranakert, located 30 miles north-east of Stepanakert, are being studied by a group of international scholars.

After the partition of Armenia between Byzantium and Persia, in 387 AD, Artsakh became part of Caucasian Albania, which, in turn, came under strong Armenian religious and cultural influence.[30][31][32][33][34] The Armenian medieval atlas Ashkharatsuits (Աշխարացույց), compiled in the 7th century by Anania Shirakatsi (Անանիա Շիրակացի, but sometimes attributed to Movses Khorenatsi as well), categorizes Artsakh and Utik as provinces of Armenia despite their presumed detachment from the Armenian Kingdom and their political association with Caucasian Albania and Persia at the time of his writing.[35] Shirakatsi specifies that Artsakh and Utik are “now detached” from Armenia and included in “Aghvank,” and he takes care to distinguish this new entity from the old “Aghvank strictly speaking” (Բուն Աղվանք) situated north of the river Kura. Because the Armenian element was more homogeneous and more developed than the tribes living to the north of the Kura River, Armenians took over Caucasian Albania’s political life and was progressively able to impose its language and culture.[36][37]

Whatever little is known about Nagorno-Karabakh and other eastern Armenian-peopled territories in the early Middle Ages comes from the text History of the Land of Aghvank (Պատմություն Աղվանից Աշխարհի) attributed to two Armenian authors: Movses Kaghankatvatsi and Movses Daskhurantsi.[38] This text, written in Old Armenian, in essence represents the history of Armenia’s provinces of Artsakh and Utik.[36] Kaghankatvatsi, repeating Movses Khorenatsi, mentions that the very name “Aghvank”/“Albania” is of Armenian origin, and relates it to the Armenian word “aghu” (աղու, meaning “kind,” “benevolent”.[39] Khorenatsi states that “aghu” was a nickname given to Prince Arran, whom the Armenian king Vagharshak I appointed as governor of northeastern provinces bordering on Armenia. According to a legendary tradition reported by Khorenatsi, Arran was a descendant of Sisak, the ancestor of the Siunids of Armenia’s province of Syunik, and thus a great-grandson of the ancestral eponym of the Armenians, the Forefather Hayk.[40] Kaghankatvatsi and another Armenian author, Kirakos Gandzaketsi, confirm Arran’s belonging to Hayk’s blood line by calling Arranshahiks “a Haykazian dynasty.” [41]

By the early Middle Ages, the non-Armenian elements of Caucasian Albanian population of upper Karabakh had completed their merger into the Armenian population, and forever disappeared as identifiable groups.[42][43]

Armenian culture and civilization flourished in the early medieval Nagorno-Karabakh — in Artsakh and Utik. In the 5th century, the first-ever Armenian school was opened on the territory of modern Nagorno-Karabakh — at the Amaras Monastery— by the efforts of St. Mesrob Mashtots, the inventor of the Armenian Alphabet.[44] St. Mesrob was very active in preaching Gospel in Artsakh and Utik. Four chapters of Movses Kaghankatvatsi’s “History...” amply describe St. Mesrob’s mission, referring to him as “enlightener,” “evangelizer” and “saint”.[45] Overall, Mesrob Mashtots made three trips to Artsakh and Utik, ultimately reaching pagan territories at the foothills of the Greater Caucasus.[45] It was at that time when the foremost Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi confirmed that the Kura River formed "the boundary of Armenian speech." [46] The 7th-century Armenian linguist and grammarian Stephanos Syunetsi stated in his work that Armenians of Artsakh had their own dialect, and encouraged his readers to learn it.[47] The same advice to study the Armenian dialect of Artsakh was repeated by Essayi Nchetsi in the 14th century, the founder of the University of Gladzor.[48] In the same 7th century, Armenian poet Davtak Kertogh writes his Elegy on the Death of Grand Prince Juansher, where each passage begins with a letter of Armenian script in alphabetical order.[49][50]

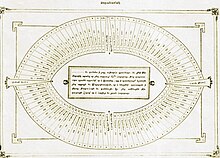

In the 5th century’s Nagorno Karabakh Vachagan II the Pious, ruler of Aghvank, adopted the so-called Constitution of Aghven (Սահմանք Կանոնական)—a code of civil regulations consisting of 21 articles and composed after a series of talks with leading clerical and civil figures of Armenia and Aghvank (e.g. Bishop of Syunik). [51] In 728 AD, the Constitution of Aghven was included in the Armenian Book of Laws (Կանոնագիրք Հայոց) by the head of the Armenian Apostolic Church Catholicos Hovhan III Odznetsi, thus laying out a blueprint for later-era Armenian legal texts, such as Lawcode written in the 12th century by Mkhitar Gosh’s under the sponsorship of Prince of Khachen. [52] The Constitution of Aghven usually features as an inclusion in Movses Kaghankatvatsi’s History of the Land of Aghvank. [53]

High Middle Ages

In the 7th and 8th centuries, during the Arab conquest of the Caucasus, the region was ruled by Caliphate-appointed local governors selected among local dynasts. In 821 the Armenian prince Sahl Smbatian revolted in Artsakh and established the House of Khachen, which ruled parts of Artsakh as a principality until the early 19th century.[54] The name “Khachen” originated from Armenian word “khach,” which means “cross”.[11] In 1000, the House of Khachen proclaimed the Kingdom of Artsakh with Hovhannes (John) Senecherib as its first ruler.[55] Initially, the province of Dizak, in southern part of modern Nagorno-Karabakh, also formed a kingdom ruled by the ancient House of Aranshahik, which descended from the region's earliest monarchs.

After the invasion of the Caucasus and Asia Minor by Seljuk Turks in the 11th century, some Armenian noble families from Artsakh chose to flee westward to the province of Cilicia on the Mediterranean Sea, joining their fellow countrymen from other provinces of Armenia.[56] Among them was Oshin of Lampron, Lord of Parisos, who left Artsakh in 1071 and established the Hethumian dynasty that ruled the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia in the 13th and 14th centuries.[57]

In 1216, when the daughter of Dizak's last king, Mamkan, married Hasan Jalal Dola, the king of Artsakh, Dizak and Khachen merged into one, which expanded of the territory of the Kingdom of Artsakh further still.[54] After the death of Hasan Jalal Dola, Artsakh continued to exist as a principality.

Late Middle Ages

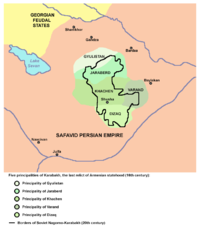

In the 15th century, the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh was part of the area ruled or influenced by Kara Koyunlu and Ak Koyunlu tribal confederations. The Turkoman lord Jahan Shah (1437–67) assigned the governorship of upper Karabakh to local Armenian princes - five noble families who held the title of meliks.[54] These dynasties represented the branches of the earlier House of Khachen and were the descendants of the medieval kings of Artsakh. Their lands were often referred to as the Country of Khamsa (five in Arabic). The Russian Empire recognized the sovereign status of the five Armenian princes in their domains by a charter of the Emperor Paul I dated 2 June 1799.[58]

These five Armenian principalities (melikdoms) in Karabakh [61] were as following:

- Principality of Gulistan - under the leadership of the Melik Beglarian family

- Principality of Jraberd - under the leadership of the Melik Israelian family

- Principality of Khachen - under the leadership of the Hasan-Jalalian family

- Principality of Varanda - under the leadership of the Melik Shahnazarian family

- Principality of Dizak - under the leadership of the Melik Avanian family.

The principalities of Nagorno Karabakh considered themselves direct descendants of the Kingdom of Armenia, and were recognized as such by foreign powers [62]

In the early 16th century, after the fall of the Ak Koyunlu state, control of the region passed to the Safavid dynasty, which created the Karabakh Beylerbeylik. Despite these conquests, the population of Upper Karabakh remained largely Armenian.[63] Initially under the control of the Ganja Khanate of the Persian Empire, wide autonomy of local Armenian princes over the territory of modern Nagorno-Karabakh and adjacent lands was confirmed by the Safavid Empire over.

The Armenian meliks maintained full control over the region until the mid-18th century.[63] In the early 18th century, Persia's Nader Shah took Karabakh out of control of the Ganja khans in punishment for their support of the Safavids, and placed it under his own control [64][65] At the same time, the Armenian meliks were granted supreme command over neighboring Armenian principalities and Muslim khans in the Caucasus, in return for the meliks' victories over the invading Ottoman Turks in the 1720s.[66]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, Nagorno Karabakh became an epicenter of the rebirth of the idea of Armenian independence.[67][68] This state, centered on semi-independent Armenian principalities of Artsakh and Syunik, would be allied with Georgia and protected by Russia.[69] Armenian melik Israel Ori, who served in the armies of Louis XIV of France, was trying to convince Johann Wilhelm, Elector Palatine (1658-1716), Pope Innocent XII and Emperor of Austria to liberate Armenia from foreign yoke. [70] Another prominent patriot from Nagorno Karabakh who worked to establish an independent Armenian entity in his homeland was Movses Baghramian. [71] Baghramian accompanied the Armenian patriot Joseph Emin (1726-1809), and tried to secure the help of Karabakh's Armenian meliks.[72]

In the mid-18th century, as internal conflicts between the meliks led to their weakening,[63] the Karabakh khanate was formed.[73]

Karabakh became a protectorate of the Imperial Russia by the Kurekchay Treaty, signed between Ibrahim Khalil Khan of Karabakh and general Pavel Tsitsianov on behalf of Tsar Alexander I in 1805, according to which the Russian monarch recognized Ibrahim Khalil Khan and his descendants as the sole hereditary rulers of the region.[74][75][76] Its new status was confirmed under the terms of the Treaty of Gulistan (1823), when Persia formally ceded Karabakh to the Russian Empire,[77][78][79][80] before the rest of Transcaucasia was incorporated into the Empire in 1828 by the Treaty of Turkmenchay.

In 1822, the Karabakh khanate was dissolved, and the area became part of the Elisabethpol Governorate within the Russian Empire. After the transfer of the Karabakh khanate to Russia, many Muslim families emigrated to Persia, while many Armenians were induced by the Russian government to emigrate from Persia to Karabakh.[81]

Russian Revolution, Civil War and Soviet era (1917-1991)

The present-day conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh has its roots in the decisions made by Joseph Stalin and the Caucasian Bureau (Kavburo) during the Sovietization of Transcaucasia. Stalin was the acting Commissar of Nationalities for the Soviet Union during the early 1920s, the branch of the government under which the Kavburo was created. After the Russian Revolution of 1917, Karabakh became part of the Transcaucasian Democratic Federative Republic, but this soon dissolved into separate Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian states. Over the next two years (1918–20), there were a series of short wars between Armenia and Azerbaijan over several regions, including Karabakh. In July 1918, the First Armenian Assembly of Nagorno-Karabakh declared the region self-governing and created a National Council and government.[82] Later, Ottoman troops entered Karabakh, meeting armed resistance by Armenians.

After the defeat of Ottoman Empire in World War I, British troops occupied Karabakh.[63] The British command provisionally affirmed Khosrov bey Sultanov (appointed by the Azerbaijani government) as the governor-general of Karabakh and Zangezur, pending final decision by the Paris Peace Conference.[83] The decision was opposed by Karabakh Armenians. In February 1920, the Karabakh National Council preliminarily agreed to Azerbaijani jurisdiction, while Armenians elsewhere in Karabakh continued guerrilla fighting, never accepting the agreement.[63][82] The agreement itself was soon annulled by the Ninth Karabagh Assembly, which declared union with Armenia in April.[63][82][84]

In April 1920, while the Azerbaijani army was locked in Karabakh fighting local Armenian forces, Azerbaijan was taken over by Bolsheviks.[63] On August 10, 1920, Armenia signed a preliminary agreement with the Bolsheviks, agreeing to a temporary Bolshevik occupation of these areas until final settlement would be reached.[85] In 1921, Armenia and Georgia were also taken over by the Bolsheviks who, in order to attract public support, promised they would allot Karabakh to Armenia, along with Nakhchivan and Zangezur (the strip of land separating Nakhchivan from Azerbaijan proper). However, the Soviet Union also had far-reaching plans concerning Turkey, hoping that it would, with a little help from them, develop along Communist lines. Needing to placate Turkey, the Soviet Union agreed to a division under which Zangezur would fall under the control of Armenia, while Karabakh and Nakhchivan would be under the control of Azerbaijan. Had Turkey not been an issue, Stalin would likely have left Karabakh under Armenian control.[86] As a result, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast was established within the Azerbaijan SSR on July 7, 1923.

With the Soviet Union firmly in control of the region, the conflict over the region died down for several decades. With the beginning of the dissolution of the Soviet Union in the late 1980s and early 1990s, the question of Nagorno-Karabakh re-emerged. Accusing the Azerbaijani SSR government of conducting forced azerification of the region, the majority Armenian population, with ideological and material support from the Armenian SSR, started a movement to have the autonomous oblast transferred to the Armenian SSR. The oblast's borders were drawn to include Armenian villages and to exclude as much as possible Azerbaijani villages. The resulting district ensured an Armenian majority.[87]

Secession, War and Nagorno Karabakh Republic

Suddenly, and unexpectedly, on February 13, 1988, Karabakh Armenians began demonstrating in their capital, Stepanakert, in favour of unification with the Armenian republic. Six days later they were joined by mass marches in Yerevan. On February 20 the Soviet of People's Deputies in Karabakh voted 110 to 17 to request the transfer of the region to Armenia. This unprecedented action by a regional soviet brought out tens of thousands of demonstrations both in Stepanakert and Yerevan, but Moscow rejected the Armenians' demands. On February 22, 1988, the first direct confrontation of the conflict occurred as a large group of Azeris marched from Agdam against the Armenian populated town of Askeran, "wreaking destruction en route." The confrontation between the Azeris and the police near Askeran degenerated into the Askeran clash, which left two Azeris dead, one of them reportedly killed by an Azeri police officer, as well as 50 Armenian villagers, and an unknown number of Azerbaijanis and police, injured.[88][89] Large numbers of refugees left Armenia and Azerbaijan as violence began against the minority populations of the respective countries.[90] In the fall of 1989, intensified inter-ethnic conflict in and around Nagorno-Karabakh led the Soviet Union to grant Azerbaijani authorities greater leeway in controlling the region.[citation needed] On November 29, 1989 direct rule in Nagorno-Karabakh was ended and the region was returned to Azerbaijani administration.[91] The Soviet policy backfired, however, when a joint session of the Armenian Supreme Soviet and the National Council, the legislative body of Nagorno-Karabakh, proclaimed the unification of Nagorno-Karabakh with Armenia.[citation needed] In 1989, Nagorno-Karabakh had a population of 192,000.[92] The population at that time was 76% Armenian and 23% Azerbaijanis, with Russian and Kurdish minorities.[92]

On December 10, 1991 in a referendum boycotted by local Azerbaijanis,[89] Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh approved the creation of an independent state. A Soviet proposal for enhanced autonomy for Nagorno-Karabakh within Azerbaijan satisfied neither side, and a full-scale war subsequently erupted between Azerbaijan and Nagorno-Karabakh, the latter receiving support from Armenia.[93][94][95][96] According to Armenia's former president, Levon Ter-Petrossian, the Karabakh leadership approach was maximalist and “they thought they could get more.”[97][98][99]

The struggle over Nagorno-Karabakh escalated after both Armenia and Azerbaijan attained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991. In the post-Soviet power vacuum, military action between Azerbaijan and Armenia was heavily influenced by the Russian military. Furthermore, both the Armenian and Azerbaijani military employed a large number of mercenaries from Ukraine and Russia.[100] As many as one thousand Afghan mujahideen participated in the fighting on Azerbaijan's side.[89] There were also fighters from Chechnya fighting on the side of Azerbaijan.[89] Many survivors from the Azerbaijani side found shelter in 12 emergency camps set up in other parts of Azerbaijan to cope with the growing number of internally displaced people due to the Nagorno-Karabakh war.[101]

By the end of 1993, the conflict had caused thousands of casualties and created hundreds of thousands of refugees on both sides.[citation needed] By May 1994, the Armenians were in control of 14% of the territory of Azerbaijan. At that stage, for the first time during the conflict, the Azerbaijani government recognized Nagorno-Karabakh as a third party in the war, and started direct negotiations with the Karabakh authorities.[63] As a result, a cease-fire was reached on May 12, 1994 through Russian negotiation.

Contemporary situation (since 1994)

Despite the ceasefire, fatalities due to armed conflicts between Armenian and Azerbaijani soldiers continued.[102] On January 25, 2005 PACE adopted Resolution 1416, which condemns the use of ethnic cleansing against the Azerbaijani population, and supporting the occupation of Azerbaijani territory.[103][104] On 15–17 May 2007 the 34th session of the Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference adopted resolution № 7/34-P, considering the occupation of Azerbaijani territory as the aggression of Armenia against Azerbaijan and recognizing the actions against Azerbaijani civilians as a crime against humanity, and condemns the destruction of archaeological, cultural and religious monuments in the occupied territories.[105]

At the 11th session of the summit of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference held on March 13–14, 2008 in Dakar, resolution № 10/11-P (IS) was adopted. According to the resolution, OIC member states condemned the occupation of Azerbaijani lands by Armenian forces and Armenian aggression against Azerbaijan, alleged ethnic cleansing against the Azeri population, and charged Armenia with the "destruction of cultural monuments in the occupied Azerbaijani territories."[106] On March 14 of the same year the UN General Assembly adopted non-binding Resolution № 62/243 which "demands the immediate, complete and unconditional withdrawal of all Armenian forces from all occupied territories of the Republic of Azerbaijan".[107] In August 2008, the United States, France, and Russia (the co-chairs of the OSCE Minsk Group) were mediating efforts to negotiate a full settlement of the conflict, proposing a "a referendum or a plebiscite, at a time to be determined later," to determine the final status of the area, return for some territories under Karabakh's control, and security guarantees.[108] Ilham Aliyev and Serzh Sarkisian traveled to Moscow for talks with Dmitry Medvedev on 2 November 2008. The talks ended in the three Presidents signing a declaration confirming their commitment to continue talks.[109] The two presidents have met again since then, most recently in Saint Petersburg.[110]

On November 22, 2009, several world leaders, among them the heads of state from Azerbaijan and Armenia, met in Munich in the hopes of renewing efforts to reach a peaceful settlement on the status of Nagorno-Karabakh. Prior to the meeting, President Aliyev once more threatened to resort to military force to reestablish control over the region if the two sides did not reach an agreeable settlement at the summit.[111]

On February 18, 2010 three Azerbaijani soldiers were killed and one wounded as a result of the ceasefire violation in that year.[112] On November 20 of the same year an Armenian sniper opened fire on Azerbaijani positions in Khojavend Rayon, killing one Azerbaijani soldier.[113] This incident brought the number of soldiers killed from both sides in August—November, 2010 to twelve.[113] On September 25, 2010 the United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon supported the withdrawal of snipers from the contact line.[114] The spokesman of Azerbaijani Defence Ministry Lt-Col Eldar Sabiroglu, however, commented that Armenian servicemen used to fire on opposite positions across the contact line from machine- and submachine guns, as well as from grenade launchers, and that these weapons have even been used against civilians.[114] On May 18–20, 2010 at the 37th session of the Council of Ministers of Foreign Affairs of the Organisation of Islamic Conference in Dushanbe, another resolution condemning the aggression of Armenia against Azerbaijan, recognizing the actions against Azerbaijani civilians as a crime against humanity and condemning the destruction of archaeological, cultural and religious monuments in occupied territories was adopted.[115] On May 20 of the same year the European Parliament in Strasbourg adopted the resolution on "The need for an EU Strategy for the South Caucasus" on the basis of the report by Evgeni Kirilov, Bulgarian member of the Parliament.[116][117] The resolution states in particular that "the occupied Azerbaijani regions around Nagorno-Karabakh must be cleared as soon as possible".[118]

Russia, in conjunction with France and the United States, convened talks in June 2011 with the hope that pressure applied to the leaders of Armenia and Azerbaijan could lead to an agreement over the fate of Nagorno-Karabakh. But no resolution of the dispute over the enclave was achieved.[119]

Geography

Nagorno-Karabakh, considered within the Soviet-era borders of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region, had a total area of 4,400 square kilometers (1,699 sq mi) and was an enclave surrounded entirely by Azerbaijani SSR; its nearest point to Armenian SSR was across the present-day Lachin corridor, roughly 4 kilometers across.[120] Approximately half of Nagorno-Karabakh terrain is over 950 m above sea level.[121] The Soviet-era borders of Nagorno-Karabakh resembled a kidney bean with the indentation on the east side. It has tall mountain ridges along the northern edge and along the west and a mountainous south. The part near the indentation of the kidney bean itself is a relatively flat valley, with the two edges of the bean, the provinces of Martakert and Martuni, having flat lands as well. Other flatter valleys exist around the Sarsang reservoir, Hadrut, and the south. The entire region lies, on average, 1,100 metres (3,600 ft) above sea level.[121] Notable peacks include the border mountain Murovdag and the Great Kirs mountain chain in the junction of Shusha Rayon and Hadrut. The territory of modern Nagorno-Karabakh forms a portion of historical regions of Artsakh and Karabakh, which lie between the rivers Kura and Araxes, and the modern Armenia-Azerbaijan border. Nagorno-Karabakh in its modern borders is part of the larger region of Upper Karabakh.

Nagorno-Karabakh’s environment vary from steppe on the Kura lowland through dense forests of oak, hornbeam and beech on the lower mountain slopes to birchwood and alpine meadows higher up. The region possesses numerous mineral springs and deposits of zinc, coal, lead, gold, marble and limestone.[122] The major cities of the region are Stepanakert, which serves as the capital of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, and Shusha, which lies partially in ruins. Vineyards, orchards and mulberry groves for silkworms are developed in the valleys.[123]

Culture of Nagorno-Karabakh

Language

The majority of the population in Nagorno-Karabakh speaks an ancient Artsakh dialect of Eastern Armenian, which was first described in the 7th century by the grammarian and philosopher Stephanos Syunetsi.[47] The continued existence of this dialect was noted in the writings of Yessayi Nchetsi, a 14th century author and founder of Armenia’s University of Gladzor.[48] The Artsakh dialect is also spoken in the provinces of Tavush and Syunik of the Republic of Armenia.[124] Due to its unique phonetics and archaic syntax developed in relative isolation from other Armenian vernaculars, the Artsakh dialect is not entirely intelligible by other Armenian speakers.[125]

Demographics and ethnic composition

Antiquity and the Middle Ages

Armenians have lived in the Karabakh region since Roman times: Strabo states that, by the second or first century BC, the entire population of Greater Armenia—Artsakh and Utik included—spoke Armenian,[26][27] though this may not necessarily mean that its population consisted exclusively of ethnic Armenians.[28] Some indirect demographic data on early medieval Artsakh are mentioned by Anania Shirakatsi in Armenia's military register known as Zoranamak (List of Armies), which required nakharar houses of Gardmanetsi, Uteatsi and Tzavdeatsi in the provinces of Artsakh and Utik to supply Armenia's royal army with no less than 3000 foot soldiers combined. [127]

The Armenian population of Artsakh and Utik remained in place after the partition of the Kingdom of Armenia in 387, as did the entire political, social, cultural and military structure of the provinces.[31][32] In the 5th century, Armenia’s foremost early medieval historian Movses Khorenatsi (Մովսես Խորենացի) testifies that the population of Artsakh and Utik spoke Armenian, with the River Kura, in his words, marking the “boundary of Armenian speech” (… զեզերս հայկական խօսիցս).[27][46][128]

The population of Nagorno Karabakh was Armenian throughout the Middle Ages.[129]In his description about the Caucasus and neighboring regions, Iranian geographer Abu Ishaq al Istakhri noted in his 10th century work Book of Climates that the road from Bardaa to Dabil lies through the lands of Armenians that belong to Sunbat, son of Ashut, i.e. to Sahl Smbatian, Prince of Khachen, and that "population of Khachen is Armenian."[130][131]

Johann Schiltberger (1380–c. 1440), a German traveler and writer, observed in the beginning of the 15th century that Karabakh's lowlands divided by the Kura River are populated by Armenians and mentioned Karabakh as part of Armenia.[132][133]

Late Middle Ages

Concrete numbers about the demographic situation in Nagorno-Karabakh appear since the 18th century. Archimandrite Minas Tigranian, after completing his secret mission to Persian Armenia ordered by the Russian Tsar Peter the Great stated in a report dated March 14, 1717 that the patriarch of the Gandzasar Monastery, in Nagorno-Karabakh, had under his authority 900 Armenian villages.[134] Nagorno-Karabakh's Armenian military commander Tarkhan suggests in his letter to Russia's Collegium of Foreign Affairs dated October 1729 that the four military districts of his land - the seghnakhs - had 30,000 Armenian soldiers, in addition to merchants and other civilians.[135]

In his letter of 1769 to Russia’s Count P. Panin, the Georgian king Erekle II, in his description of Nagorno-Karabakh, suggests: "Seven families rule the region of Khamse. Its population is totally Armenian." [136][137]

When discussing Karabakh and Shusha in the 18th century, the Russian diplomat and historian S. M. Bronevskiy (Russian: С. М. Броневский) indicated in his Historical Notes that Karabakh, which he said "is located in Greater Armenia" had as many as 30–40,000 armed Armenian men in 1796.[138]

Close to 30,000 Armenians left Nagorno-Karabakh in the late 18th century as a result of famine and persecution of Armenian nobility by the Karabakh khan.[139] In 1797, Russian Tsar Paul I of Russia in his letter to General Ivan Gudovich mentioned that the number of Armenians who had to flee Nagorno-Karabakh for Georgia was close to 11,000 families.[140][141]

Russian Rule (1805-1918)

A survey prepared by the Russian imperial authorities in 1823, several years before the 1828 Armenian migration from Persia to the newly established Armenian Province, shows that all Armenians of Karabakh (5107 boroughs) compactly resided in its highland portion, i.e. on the territory of the five traditional Armenian principalities in Nagorno-Karabakh, and constituted an absolute demographic majority on those lands. The survey's more than 260 pages recorded that the district of Khachen had twelve Armenian villages and no Tatar (Muslim) villages; Jalapert (Jraberd) had eight Armenian villages and no Tatar villages; Dizak had fourteen Armenian villages and one Tatar village; Gulistan had twelve Armenian and five Tatar villages; and Varanda had twenty-three Armenian villages and one Tatar village.[142][143]

According to a Russian census, in 1897 there were 106,363 Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh, and they made up 94 percent of the rural population within the boundaries of the Nagorno Karabakh Autonomous Oblast.[144] In 1914, the Karabakh Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church, whose jurisdiction covered Nagorno Karabakh and all adjacent Armenian-populated territories, had 206,768 parishioners living in 224 Armenian villages, with 222 functioning Armenian churches and monasteries, and 188 priests.[145][146]

Soviet Era

In the Soviet times, Azerbaijan tried to change demographic balance in the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Region (NKAO) in favor of Azerbaijanis and to the detriment of its Armenian majority by sending Azerbaijanis from other parts of Azerbaijani SSR to NKAO. In 2002, Azerbaijan’s President Heydar Aliyev made a public confession that he personally conceived and directed a policy of squeezing out Armenians from the province and replacing them with Azerbaijanis.[148] Adding an Azerbaijani sector to a local university and sending Azerbaijani workers to a newly-commissioned shoe factory were mentioned by Heydar Aliyev among the tools of his demographic policy.

Heydar Aliyev: By doing this, I tried to increase the number of Azerbaijanis and to reduce the number of Armenians. [148][149]

Heydar Aliyev's commentary was supported by his colleagues and subordinates, such as Ramil Usubov - Azerbaijan's long-served Minister of the Interior.[150]

Nearing the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1989, the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast boasted a population of 145,593 Armenians (76.4%), 42,871 Azerbaijanis (22.4%),[100] and several thousand Kurds, Russians, Greeks, and Assyrians. Most of the Azerbaijani and Kurdish populations fled the region during the heaviest years of fighting in the war from 1992 to 1993. The main language spoken in Nagorno-Karabakh is Armenian; however, Karabakh Armenians speak a dialect of Armenian which is considerably different from that which is spoken in Armenia as it is layered with Russian, Turkish and Persian words.[89]

Nagorno-Karabakh Republic

In 2001, the NKR's reported population was 95% Armenian, with the remaining total including Assyrians, Greeks, and Kurds.[151] In March 2007, the local government announced that its population had grown to 138,000. The annual birth rate was recorded at 2,200-2,300 per year, an increase from nearly 1,500 in 1999. Until 2000, the country's net migration was at a negative.[152] For the first half of 2007, 1,010 births and 659 deaths were reported, with a net emigration of 27.[153]

The OSCE report, released in March 2011, estimates the population of territories controlled by ethnic Armenians "adjacent to the breakaway Azerbaijani region of Nagorno-Karabakh" to be 14,000, and states "there has been no significant growth in the population since 2005."[154]

Most of the Armenian population is Christian and belongs to the Armenian Apostolic Church. Certain Orthodox Christian and Evangelical Christian denominations also exist; other religions include Judaism.[151]

Gallery

- Nagorno Karabakh

-

Tzitzernavank Monastery, 5th century.

-

St. Mesrob Mashtots, inventor of the Armenian Alphabet (406 AD), opened first Armenian school in Nagorno Karabakh's Amaras Monastery in c. 410 AD. [155]

-

Prince Vahtang of Khachen, grandson of Grand Prince Hasan Jalal Vahtangian (1214-1261). 13th century Armenian miniature from Nagorno Karabakh. [156]

-

Khachkar at Dadivank Monastery (1214).

-

Armenian House in Shusha, 1873, by Louis Figuier (1819-1894).

-

18th century Armenian-inscribed carpet "Gohar" from Nagorno Karabakh (c. 1700) [157]

-

Ruins of the Armenian half of Shusha after the city's destruction by Azerbaijani army in March 1920. In the center: defaced Armenian Cathedral of the Holy Savior "Ghazanchetsots."

-

Torgom (Grigor) Tumiants, famed Nagorno Karabakh guerrilla leader (1879-1906)

-

Postal stamp depicting prominent World War II military leaders from Nagorno Karabakh: Field Marshall Ivan Bagramyan, Admiral Ivan Isakov, Field Marshall Hamazasp Babajanian, and Field Marshall Armenak Khanferiants.

-

Buildings in Stepanakert destroyed in 1991-93 by Azerbaijani artillery and aerial attacks.

See also

- Outline of Nagorno-Karabakh

- Index of Nagorno-Karabakh-related articles

- Janapar - the hiking trail across Nagorno-Karabakh

References

- ^ Britannica encyclopedia article «Armenian Highland»:"mountainous region of Transcaucasia. It lies mainly in Turkey, occupies all of Armenia, and includes southern Georgia, western Azerbaijan, and northwestern Iran. "

- ^ Constitution of the Nagorno-Karabakh Republic. Publishing House of the NKR Government, Stepanakert, 2007, Article 142 [1]

- ^ a b Robert H. Hewsen, Armenia: a Historical Atlas. University of Chicago Press, 2001, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 60, 61, 67

- ^ see references to Artsakh in Bishop Barkhudarian, Makar. Artsakh. Baku, 1885

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, p. 254. An example of the "Arstakh" mentioned instead of Karabakh in 1777.

- ^ PanArmenian Network. Artsakh: From Ancient Time to 1918. PanArmenian.net. June 9, 2003. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ Strabo (ed. H.C. Hamilton, Esq., W. Falconer, M.A.) . Geography. The Perseus Digital Library. 11.14.4. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 52

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 65, 67

- ^ a b Christopher Walker. The Armenian presence in Mountainous Karabakh, in John F. R. Wright et al.: Transcaucasian Boundaries (SOAS/GRC Geopolitics). 1995, p. 93

- ^ John Noble, Michael Kohn, Danielle Systermans. Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Lonely Planet; 3 edition (May 1, 2008), p. 306

- ^ a b Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). Armenia: A Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 73, map 62. ISBN 0-2263-3228-4.

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 7

- ^ The BBC World News. Regions and territories: Nagorno-Karabakh, BBC News Online. Last updated October 3, 2007. Retrieved November 21, 2007.

- ^ a b Template:Hy icon Ulubabyan, Bagrat. Karabagh (Ղարաբաղ). The Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia, vol. vii, Yerevan, Armenian SSR, 1981 p. 26

- ^ C. G. Ellis, "Oriental Carpets", 1988. p133.

- ^ Viviano, Frank. "The Rebirth of Armenia", National Geographic Magazine, March 2004

- ^ John Noble, Michael Kohn, Danielle Systermans. Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Lonely Planet; 3 edition (May 1, 2008), p. 307

- ^ Constitution of Aghven was included in the Armenian Book of Laws (Կանոնագիրք Հայոց) in the 8th century by Catholicos Hovhannes III Odznetsi. The displayed page mentions names of 14 dignitaries who signed the Constitution, and includes the endorsement of King Vachagan the Pious. Source: Movses Kaghankatvatsi’s “History of the Land of Aghvank:” exhibit at Matenadaran (Armenia’s Institute of Ancient Manuscripts) [2][3]. Source: Բաբկեն ՀԱՐՈՒԹՅՈՒՆՅԱՆ. ՍԲ ՀՈՎՀԱՆՆԵՍ Գ ՕՁՆԵՑԻ. Հայկական Հանրագիտարան. 1977.

- ^ Mkhitar Gosh.Lawcode. Vagharshapat, 1880, (in Armenian).

- ^ a b Robert H. Hewsen. "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians," in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity, Chicago: 1982, 27–40.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. Armenia: a Historical Atlas. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 32–33, map 19 (shows the territory of modern Nagorno-Karabakh as part of the Orontids' Kingdom of Armenia)

- ^ Hewsen, Robert. "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians," in Samuelian, Thomas J. (Ed.) Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity, Chicago: 1982, pp. 27-40.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. “The Kingdom of Artsakh,” in T. Samuelian & M. Stone, eds. Medieval Armenian Culture. Chico, CA, 1983.

- ^ a b Strabo (ed. H.C. Hamilton, Esq., W. Falconer, M.A.) . Geography. The Perseus Digital Library. 11.14.4. Retrieved November 21, 2007, book XI, chapters 14–15 (Bude, vol. VIII, p. 123)

- ^ a b c Svante E. Cornell. Small Nations and Great Powers. 2001, p. 64

- ^ a b V. A. Shnirelman. Memory wars. Myths, identity and politics in Transcaucasia. Academkniga, Moscow, 2003 ISBN 5-94628-118-6

- ^ History by Sebeos, chapter 26

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica. Article: Azerbaijan

- ^ a b Walker, Christopher J. Armenia and Karabagh: The Struggle for Unity. Minority Rights Group Publications, 1991, p. 10

- ^ a b Istorija Vostoka. V 6 t. T. 2, Vostok v srednije veka Moskva, «Vostochnaya Literatura», 2002. ISBN 5-02-017711-3

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. "Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians," in: Samuelian, Thomas J. (Hg.), Classical Armenian Culture. Influences and Creativity, Chicago: 1982

- ^ V.Minorsky. History of Shirvan and Darband

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. Armenia: a Historical Atlas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001, map “Armenia according to Anania of Shirak’

- ^ a b Robert H. Hewsen, “Ethno-History and the Armenian Influence upon the Caucasian Albanians,” in Classical Armenian Culture: Influences and Creativity, ed. Thomas J. Samuelian (Philadelphia: Scholars Press, 1982)

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. “The Kingdom of Artsakh,” in T. Samuelian & M. Stone, eds. Medieval Armenian Culture. Chico, CA, 1983

- ^ The History of the Caucasian Albanians by Movsēs Dasxuranc'i. Translated by Charles Dowsett. London: Oxford University Press, 1961, pp. 3-4 “Introduction”

- ^ Moses Khorenatsi. History of the Armenians, translated from Old Armenian by Robert W. Thomson. Harvard University Press, 1978, p.

- ^ Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of the Land of Aluank, translated from Old Armenian by Sh. V. Smbatian. Yerevan: Matenadaran (Institute of Ancient Manuscripts), 1984, p. 43

- ^ Kirakos Gandzaketsi. “Kirakos Gandzaketsi’s history of the Armenians,” Sources of the Armenian Tradition. New York, 1986, p. 67

- ^ Rutland, Peter. "Democracy and Nationalism in Armenia". Europe-Asia Studies 46:841

- ^ К. В. Тревер. Очерки По Истории и Культуре Кавказской Албании IV В. до Н. Э. — VII В. н. э. (источники и литература). Изданиe Академии Наук СССР, М.-Л., 1959, стр. 81 Udis, living far from Artsakh or Utik, are perhaps the only exception.

- ^ Viviano, Frank. “The Rebirth of Armenia,” National Geographic Magazine, March 2004, p. 18,

- ^ a b Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of the Land of Aluank, Book I, chapters 27, 28 and 29; Book II, chapter 3.

- ^ a b Moses Khorenatsi. History of the Armenians, translated from Old Armenian by Robert W. Thomson. Harvard University Press, 1978, Book II

- ^ a b Н.Адонц. «Дионисий Фракийский и армянские толкователи», Пг., 1915, 181—219

- ^ a b Christophe J. Walker. Armenia and Karabagh: the Struggle for Unity. Minority Right Publications, 1991, p. 76

- ^ Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of the Land of Aluank, translated from Old Armenian by Sh. V. Smbatian. Yerevan: Matenadaran (Institute of Ancient Manuscripts), 1984, Elegy on the Death of Prince Juansher

- ^ Agop Jack Hacikyan, Gabriel Basmajian, Edward S. Franchuk. The Heritage of Armenian Literature. Wayne State University Press (December 2002), pp. 94–99

- ^ The History of the Caucasian Albanians by Movsēs Dasxuranc'i. Translated by Charles Dowsett. London: Oxford University Press, 1961, “Constitution.”

- ^ Mkhitar Gosh. The Lawcode, translated from Old Armenian by Robert W. Thomson. NJ: Rodopi, 2000

- ^ Movses Kalankatuatsi. History of the Land of Aluank, translated from Old Armenian by Sh. V. Smbatian. Yerevan: Matenadaran (Institute of Ancient Manuscripts), 1984, “Constitution”

- ^ a b c Robert H. Hewsen, Armenia: A Historical Atlas. The University of Chicago Press, 2001, pp. 119, 155, 163, 264–65.

- ^ Hewsen, Robert H. "The Kingdom of Artsakh", in T. Samuelian & M. Stone, eds. Medieval Armenian Culture. Chico, CA, 1983

- ^ Der Nersessian, Sirarpie. "The Kingdom of Cilician Armenia." in A History of the Crusades, vol. II. Kenneth M. Setton (ed.) Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1962, pp. 630–631

- ^ Bournoutian, Ani Atamian. "Cilician Armenia" in The Armenian People From Ancient to Modern Times, Volume I: The Dynastic Periods: From Antiquity to the Fourteenth Century. Ed. Richard G. Hovannisian. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997, pp. 283–290. ISBN 1-4039-6421-1

- ^ Robert H. Hewsen. Russian–Armenian relations, 1700–1828. Society of Armenian Studies, N4, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1984, p 37.

- ^ Mir Davoud Zadour Mélik Schanazar, Détails sur la situation actuelle du royaume de Perse (...et par Jacques Chahan de Cirbied), Paris 1816

- ^ An Armenian Diplomat in the Service of Napoleon a Hundred Years Ago, by G. Thoumaian, Ararat, vol. 4, London, 1917 [[4]]

- ^ Raffi, The History of Karabagh's Meliks, Vienna, 1906, in Armenian

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, p. 330, See: "Letter of Meliks of Karabagh to Prince Petemkin, January 23, 1790"

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cornell, Svante E. Template:PDFlink. Uppsala: Department of East European Studies, April 1999.

- ^ Template:Ru icon Abbas-gulu Aga Bakikhanov. Golestan-i Iram; according to a 18th c. local Turkic-Muslim writer Mirza Adigezal bey, Nadir shah placed Karabakh under his own control, while a 19th-century local Turkic Muslim writer Abbas-gulu Aga Bakikhanov states that the shah placed Karabakh under the control of the governor of Tabriz.

- ^ Template:Ru icon Mirza Adigezal bey. Karabakh-name, p. 48

- ^ Walker, Christopher J. Armenia: Survival of a Nation. London: Routledge, 1990 p. 40 ISBN 0-415-04684-X

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 72

- ^ George A. Bournoutian. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-e Qarabagh. Mazda Publishers, 1994. p. 17. ISBN 1-56859-011-3, 978-1-568-59011-0

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 72

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 73

- ^ Life and Adventures of Emin Joseph Emin 1726-1809 Written by himself. Second edition with Portrait, Correspondence, Reproductions of original Letters and Map*. Calcutta 1918. [5]

- ^ A.R. Ioannisian. Joseph Emin. Yerevan, 1989, link to full text: [6]

- ^ For the Resolution of the Karabakh Conflict, azer.org

- ^ Template:Ru icon Просительные пункты и клятвенное обещание Ибраим-хана.

- ^ Muriel Atkin. The Strange Death of Ibrahim Khalil Khan of Qarabagh. Iranian Studies, Vol. 12, No. 1/2 (Winter – Spring, 1979), pp. 79–107

- ^ George A. Bournoutian. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-e Qarabagh. Mazda Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1-56859-011-3, 978-1-568-59011-0

- ^ Tim Potier. Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 2001, p. 2. ISBN 90-411-1477-7.

- ^ Leonidas Themistocles Chrysanthopoulos. Caucasus Chronicles: Nation-building and Diplomacy in Armenia, 1993–1994. Gomidas Institute, 2002, p. 8. ISBN 1-884630-05-7.

- ^ The British and Foreign Review. J. Ridgeway and sons, 1838, p. 422.

- ^ Taru Bahl, M.H. Syed. Encyclopaedia of the Muslim World. Anmol Publications PVT, 2003 p. 34. ISBN 81-261-1419-3.

- ^ The penny cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. 1833, Georgia.

- ^ a b c Template:PDFlink, New England Center for International Law & Policy

- ^ Circular by colonel D. I. Shuttleworth of the British Command

- ^ Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia: A Legal Appraisal by Tim Potier. ISBN 90-411-1477-7

- ^ Walker. The Survival of a Nation. pp. 285–90

- ^ Service, Robert. Stalin: A Biography. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2006 p. 204 ISBN 0-674-02258-0

- ^ Audrey L. Altstadt. The Azerbaijani Turks: power and identity under Russian rule. Hoover Press, 1992. ISBN 0817991824, 9780817991821

- ^ Elizabeth Fuller, Nagorno-Karabakh: The Death and Casualty Toll to Date, RL 531/88, Dec. 14, 1988, pp. 1–2

- ^ a b c d e f de Waal, Thomas (2003). Black Garden: Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-1945-7.

- ^ Lieberman, Benjamin (2006). Terrible Fate: Ethnic Cleansing in the Making of Modern Europe. Chicago: Ivan R. Dee. pp. 284–92. ISBN 1-5666-3646-9.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of World History. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. 2001. p. 906.

- ^ a b Miller, Donald E. and Lorna Touryan Miller. Armenia: Portraits of Survival and Hope. Berkley: University of California Press, 2003 p. 7 ISBN 0-520-23492-8

- ^ Human Rights Watch. Playing the "Communal Card". Communal Violence and Human Rights: "By early 1992 full-scale fighting broke out between Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians and Azerbaijani authorities." / "...Karabakh Armenian forces—often with the support of forces from the Republic of Armenia—conducted large-scale operations..." / "Because 1993 witnessed unrelenting Karabakh Armenian offensives against the Azerbaijani provinces surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh..." / "Since late 1993, the conflict has also clearly become internationalized: in addition to Azerbaijani and Karabakh Armenian forces, troops from the Republic of Armenia participate on the Karabakh side in fighting inside Azerbaijan and in Nagorno-Karabakh."

- ^ Human Rights Watch. The former Soviet Union. Human Rights Developments: "In 1992 the conflict grew far more lethal as both sides—the Azerbaijani National Army and free-lance militias fighting along with it, and ethnic Armenians and mercenaries fighting in the Popular Liberation Army of Artsakh—began."

- ^ United States Institute of Peace. Nagorno-Karabakh Searching for a Solution. Foreword: "Nagorno-Karabakh’s armed forces have not only fortified their region, but have also occupied a large swath of surrounding Azeri territory in the hopes of linking the enclave to Armenia."

- ^ United States Institute of Peace. Sovereignty after Empire. Self-Determination Movements in the Former Soviet Union. Hopes and Disappointments: Case Studies "Meanwhile, the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh was gradually transforming into a full-scale war between Azeri and Karabakh irregulars, the latter receiving support from Armenia." / "Azerbaijan's objective advantage in terms of human and economic potential has so far been offset by the superior fighting skills and discipline of Nagorno-Karabakh's forces. After a series of offensives, retreats, and counteroffensives, Nagorno-Karabakh now controls a sizable portion of Azerbaijan proper ... including the Lachin corridor."

- ^ "By Giving Karabakh Lands to Azerbaijan, Conflict Would Have Ended in '97, Says Ter-Petrosian". Asbarez. Asbarez. April 19, 2011.

- ^ "Ter-Petrosyan on the BBC: Karabakh conflict could have been resolved by giving certain territories to Azerbaijan". ArmeniaNow. ArmeniaNow. April 19, 2011.

- ^ "Первый президент Армении о распаде СССР и Карабахе". BBC. BBC. April 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Human Rights Watch. Seven Years of Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh. December 1994, p. xiii, ISBN 1-56432-142-8, citing: Natsional'nyi Sostav Naseleniya SSSR, po dannym Vsesoyuznyi Perepisi Naseleniya 1989 g., Moskva, "Finansy i Statistika"

- ^ Azerbaijan closes last of emergency camps, UNHCR

- ^ No End in Sight to Fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh by Ivan Watson/National Public Radio. Weekend Edition Sunday, April 23, 2006.

- ^ Проект заявления по Нагорному Карабаху ожидает одобрения парламентских сил Армении

- ^ Резолюция ПАСЕ по Карабаху: что дальше?. BBC Russian.

- ^ Resolutions on Political Affairs. The Thirty-Fourth Session of the Islamic Conference of Foreign Ministers.

- ^ Resolutions on Political Affairs. Islamic Summit Conference. 13–14 May 2008

- ^ The text of the resolution № 62/243

- ^ Hakobyan, Tatul (2008-11-21). "Mediators play down prospects of early Karabakh settlement". Armenian Reporter. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ "Document: Full text of the declaration adopted by presidents of Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Russia at Meiendorf Castle near Moscow on November 2, 2008". Armenian Reporter. 2008-11-02. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ "Armenia, Azerbaijan Satisfied With Fresh Summit". RFE/RL. 2008-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-16.

- ^ "Azerbaijan military threat to Armenia." The Daily Telegraph. November 22, 2009. Retrieved November 23, 2009.

- ^ "Defense Ministry: Armenian sniper kills three and wounds one Azerbaijani soldier". Trend. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ^ a b "Armenian sniper kills Azeri soldier". Press TV. Retrieved 2010-11-27.

- ^ a b "Withdrawing snipers would not end conflict, says Baku". News.az. 27 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-29.

- ^ RESOLUTIONS ON POLITICAL ISSUES ADOPTED BY THE COUNCIL OF FOREIGN MINISTERS (SESSION OF SHARED VISION OF A MORE SECURE AND PROSPEROUS ISLAMIC WORLD) DUSHANBE, REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN 4-6 JAMADUL THANI 1431H(18-20 MAY 2010

- ^ "FM: Azerbaijan welcomes resolution 'Need for EU Strategy for South Caucasus' adopted by European Parliament." Trend.az. May 21, 2010.

- ^ "EU's Ashton Says Nagorno-Karabakh Elections Illegal." RFE/RL. May 21, 2010.

- ^ Bulgarian MEPs Urge EU to Be Proactive in South Caucasus.

- ^ Barry, Ellen (24 June 2011). "Azerbaijan and Armenia Fail to End Enclave Dispute". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-06-26.

- ^ Country Overview

- ^ a b Zürcher, Christoph (2007). The post-Soviet wars: rebellion, ethnic conflict, and nationhood in the Caucasus. NYU Press. p. 184. ISBN 0814797091.

- ^ DeRouen, Karl R. (ed.) (2007). Civil wars of the world: major conflicts since World War II, Volume 2. ABC-CLIO. p. 150. ISBN 1851099190.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help) - ^ "Nagorno-Karabakh". Britannica. Retrieved 2010-11-30.

- ^ Bert Vaux. The Phonology of Armenian (Phonology of the World's Languages), Oxford University Press, USA (June 4, 1998)

- ^ Thomas de Waal. The Caucasus: An Introduction. Oxford University Press, USA (September 9, 2010), p. 102

- ^ Anania Shirakatsi, Chronicles. As described in: Hovhannes Shahatuniants. Description of the Cathedral of Echmiadzin and the ancient Ayrarat districts. Echmiadzin, 1842 , volume 2, p. 58

- ^ Hovhannes Shahatuniants. Description of the Cathedral of Echmiadzin and the ancient Ayrarat districts. Echmiadzin, 1842 , volume 2, p. 58. The manuscript of Zoranamak is stored in the Mesrop Mashtots Institute of Ancient Manuscripts [Matenadaran) in Yerevan.

- ^ Strabo, op. cit., book XI, chapters 14–15 (Bude, vol. VIII, p. 123)

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 76

- ^ КАРАУЛОВ Н. А. Сведения арабских писателей X и XI веков по Р. Хр. о Кавказе, Армении и Адербейджане.

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 76

- ^ Путешествие Ивана Шильтбергера по Европе, Азии и Африке с 1394 по 1427 г. Перевел с немецкого и снабдил примечаниями Ф. Брун, Одесса, 1866, p. 110

- ^ The Bondage And Travels Of Johann Schiltberger, A Native Of Bavaria, In Europe, Asia And Africa, 1396-1427. J. Buchan Telfer (Translator), Kessinger Publishing, LLC (September 10, 2010), p. 86

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, p. 120–21

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, p. 145, 146

- ^ Цагарели А. А. Грамота и гругие исторические документы XVIII столетия, относяшиеся к Грузии, Том 1. СПб 1891, ц. 434-435. This book is available online from Google Books

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. Armenians and Russia, 1626-1796: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 2001, page 246

- ^ S.M.Bronesvskiy. Historical Notes... St. Petersburg. 1996. Исторические выписки о сношениях России с Персиею, Грузиею и вообще с горскими народами, в Кавказе обитающими, со времён Ивана Васильевича доныне». СПб. 1996, секция "Карабаг"

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. Russia and the Armenians of Transcaucasia, 1797-1889: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers. 1998, p. 20 and ref. 6

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. Russia and the Armenians of Transcaucasia, 1797-1889: A Documentary Record. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers. 1998, p. 22.

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 77

- ^ Description of the Karabakh province prepared in 1823 according to the order of the governor in Georgia Yermolov by state advisor Mogilevsky and colonel Yermolov 2nd ([Описание Карабахской провинции, составленное в 1823 г. действительным статским советником Могилевским и полковником Ермоловым 2-ым. Тифлис, 1866] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help)), Tbilisi, 1866.

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. A History of Qarabagh: An Annotated Translation of Mirza Jamal Javanshir Qarabaghi's Tarikh-E Qarabagh. Costa Mesa, CA: Mazda Publishers, 1994, page 18

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 77

- ^ Ararat magazine, 1914, Vagharshapat, p. 637

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 77

- ^ Сельскохозяйственная перепись Азербайджана 1921 г. in: "Известия Аз. ЦСУ", 1923, № 1 (7), с. 106-111), and М. Авдеева. "Численность и племенной состав сельского населения Азербайджана по данным переписи 1921 г.; Население СССР: По данным Всесоюз. переписей населения в 1926-89 гг., М.: Политиздат, январь 1991; NKR Census, 2005 as seen on http://census.stat-nkr.am

- ^ a b See: «Гейдар Алиев: Государство с оппозицией лучше», газета «Эхо» (Азербайджан), Номер 138 (383) CP, 24 июля 2002) [7]

- ^ Template:Ru icon Anon. "Кто на стыке интересов? США, Россия и новая реальность на границе с Ираном" ("Who is at the turn of interests? US, Russia and new reality on the border with Iran"). Regnum. April 4, 2006

- ^ Usubov, Ramil. Nagorniy Karabakh: the Mission of Salvation Began the in the 70s, Panorama, May 12, 1999 (in Russian).

- ^ a b Ethnic composition of the region as provided by the government

- ^ Regnum News Agency. Nagorno Karabakh prime minister: We need to have at least 300,000 population. Regnum. March 9, 2007. Retrieved March 9, 2007.

- ^ Евразийская панорама

- ^ "Azerbaijani Party Appeals To OSCE About Armenian Resettlement". RFERL. 2011-05-13. Retrieved 13 May 2011.

- ^ Viviano, Frank. "The Rebirth of Armenia", National Geographic Magazine, March 2004

- ^ Hakopian, Hravard. The Miniatures of Artsakh and Utik: Thirteenth-Fourteenth Centuries. Yerevan, 1989

- ^ Chorbajian, Levon; Donabedian Patrick; Mutafian, Claude. The Caucasian Knot: The History and Geo-Politics of Nagorno-Karabagh. NJ: Zed Books, 1994, p. 86

External links

- All UN Security Council resolutions on Nagorno-Karabakh, courtesy U.S. State department

- Nagorno-Karabakh Agreement of 2 November 2008 and country profile from BBC News Online

- Article on the Dec. 10 Referendum from Russia Profile

- The conflict over the Nagorno-Karabakh region dealt with by the OSCE Minsk Conference — Report by rapporteur David Atkinson presented to Political Affairs Committee of the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

- Conciliation Resources - Accord issue: The limits of leadership - Elites and societies in the Nagorny Karabakh peace process also key texts & agreements and chronology (in English & Russian)

- Independence of Kosovo and the Nagorno-Karabakh Issue

- Interview with Thomas De Waal

- Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty. Nagorno-Karabakh: Timeline Of The Long Road To Peace

- Resolution #1416 from the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

- USIP — Nagorno-Karabakh Searching for a Solution: Key points, by Patricia Carley, Publication of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

- USIP — Sovereignty after Empire Self-Determination Movements in the Former Soviet Union. Case Studies: Nagorno-Karabakh. by Galina Starovoitova, Publication of the United States Institute of Peace (USIP)

- photostory Nagorno-Karabakh - 15 years after the cease fire agreement

- photostory Inside Warren of Karabakh Frontline

![St. Mesrob Mashtots, inventor of the Armenian Alphabet (406 AD), opened first Armenian school in Nagorno Karabakh's Amaras Monastery in c. 410 AD. [155]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/84/Mesrop_Mashtots_by_Francesco_Maggiotto.jpg/99px-Mesrop_Mashtots_by_Francesco_Maggiotto.jpg)

![Prince Vahtang of Khachen, grandson of Grand Prince Hasan Jalal Vahtangian (1214-1261). 13th century Armenian miniature from Nagorno Karabakh. [156]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/52/Prince.Vahtang.of.Khachen-13th_century-Nagorno-Karabakh.jpg/104px-Prince.Vahtang.of.Khachen-13th_century-Nagorno-Karabakh.jpg)