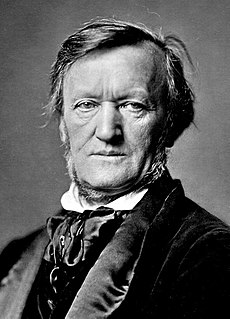

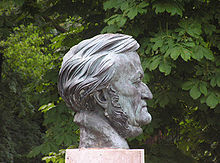

Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner (/[invalid input: 'icon']ˈvɑːɡnər/; German pronunciation: [ˈʁiçaʁt ˈvaːɡnɐ]; 22 May 1813 – 13 February 1883) was a German composer, conductor, theatre director and polemicist primarily known for his operas (or "music dramas", as he later called them). Wagner's compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their complex texture, rich harmonies and orchestration, and the elaborate use of leitmotifs: musical themes associated with individual characters, places, ideas or plot elements. Unlike most other opera composers, Wagner wrote both the music and libretto for every one of his stage works. Perhaps the two best-known extracts from his works are the Ride of the Valkyries from the opera Die Walküre, and the Wedding March (Bridal Chorus) from the opera Lohengrin.

Initially establishing his reputation as a composer of works such as The Flying Dutchman and Tannhäuser which were broadly in the romantic vein of Weber and Meyerbeer, Wagner transformed operatic thought through his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk ("total work of art"). This would achieve the synthesis of all the poetic, visual, musical and dramatic arts and was announced in a series of essays between 1849 and 1852. Wagner realized this concept most fully in the first half of the monumental four-opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen. However, his thoughts on the relative importance of music and drama were to change again, and he reintroduced some traditional operatic forms into his last few stage works, including Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg.

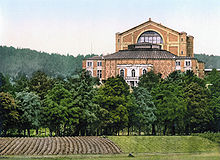

Wagner pioneered advances in musical language, such as extreme chromaticism and quickly shifting tonal centres, which greatly influenced the development of European classical music. His Tristan und Isolde is sometimes described as marking the start of modern music. Wagner's influence spread beyond music into philosophy, literature, the visual arts and theatre. He had his own opera house built, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which contained many novel design features. It was here that the Ring and Parsifal received their premieres and where his most important stage works continue to be performed today in an annual festival run by his descendants. Wagner's views on conducting were also highly influential. His extensive writings on music, drama and politics have all attracted extensive comment in recent decades, especially where they have antisemitic content.

Wagner achieved all of this despite a life characterized, until his last decades, by political exile, turbulent love affairs, poverty and repeated flight from his creditors. His pugnacious personality and often outspoken views on music, politics and society made him a controversial figure during his life, which he remains to this day. The effect of his ideas can be traced in many of the arts throughout the twentieth century.

Biography

Early years

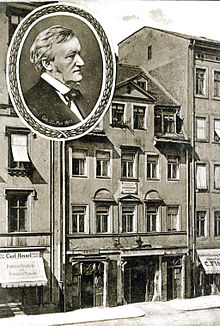

Richard Wagner was born at No. 3 ('The House of the Red and White Lions'), the Brühl, in the Jewish quarter of Leipzig, the ninth child of Carl Friedrich Wagner, who was a clerk in the Leipzig police service,[1] and his wife Johanna Rosine (née Paetz), the daughter of a baker.[2] Wagner's father died of typhus six months after Richard's birth, following which Wagner's mother began living with the actor and playwright Ludwig Geyer, a friend of Richard's father.[3] In August 1814 Johanna and Geyer probably married – although no documentation of this is found in the Leipzig church registers.[4] She and her family moved to Geyer's residence in Dresden. Until he was fourteen, Wagner was known as Wilhelm Richard Geyer. He almost certainly suspected that Geyer was his natural father.[5]

Geyer's love of the theatre was shared by his stepson, and Wagner took part in his performances. In his autobiography, Wagner recalled once playing the part of an angel.[6] The boy Wagner was also hugely impressed by the Gothic elements of Weber's Der Freischütz. In late 1820, Wagner was enrolled at Pastor Wetzel's school at Possendorf, near Dresden, where he received some piano instruction from his Latin teacher.[7] He could not manage a proper scale but preferred playing theatre overtures by ear. Geyer died in 1821, when Richard was eight. Subsequently, Wagner was sent to the Kreuz Grammar School in Dresden, paid for by Geyer's brother.[8] The young Wagner entertained ambitions as a playwright, his first creative effort (listed as 'WWV 1') being a tragedy, Leubald, begun at school in 1826, which was strongly influenced by Shakespeare and Goethe. Wagner was determined to set it to music; he persuaded his family to allow him music lessons.[9]

By 1827, the family had moved back to Leipzig. Wagner's first lessons in harmony were taken in 1828–1831 with Christian Gottlieb Müller.[10] In January 1828 he first heard Beethoven's 7th Symphony and then, in March, Beethoven's 9th Symphony performed in the Gewandhaus. Beethoven became his inspiration, and Wagner wrote a piano transcription of the 9th Symphony.[11] He was also greatly impressed by a performance of Mozart's Requiem.[12] From this period date Wagner's early piano sonatas and his first attempts at orchestral overtures.[13]

In 1829 he saw the dramatic soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Devrient on stage, and she became his ideal of the fusion of drama and music in opera. In his autobiography, Wagner wrote, "If I look back on my life as a whole, I can find no event that produced so profound an impression upon me." Wagner claimed to have seen Schröder-Devrient in the title role of Fidelio; however, it seems more likely that he saw her performance as Romeo in Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi.[14]

He enrolled at the University of Leipzig in 1831 where he became a member of the Studentenverbindung Corps Saxonia Leipzig. He also took composition lessons with the cantor of Saint Thomas Church, Christian Theodor Weinlig.[15] Weinlig was so impressed with Wagner's musical ability that he refused any payment for his lessons, and arranged for Wagner's Piano Sonata in B flat (which was consequently dedicated to him) to be published as the composer's Op. 1. A year later, Wagner composed his Symphony in C major, a Beethovenesque work performed in Prague in 1832[16] and at the Leipzig Gewandhaus in 1833.[17] He then began to work on an opera, Die Hochzeit (The Wedding), which he never completed.[18]

Early career

In 1833, Wagner's older brother Karl Albert managed to obtain for Richard a position as choir master in Würzburg.[19] In the same year, at the age of 20, Wagner composed his first complete opera, Die Feen (The Fairies). This opera, which clearly imitated the style of Carl Maria von Weber, would go unproduced until half a century later, when it was premiered in Munich shortly after the composer's death in 1883.[20]

Meanwhile, Wagner held a brief appointment as musical director at the opera house in Magdeburg[21] during which he wrote Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love), based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure. This was staged at Magdeburg in 1836, but closed before the second performance, leaving the composer (not for the last time) in serious financial difficulties.[22] In 1834 Wagner had fallen for the actress Christine Wilhelmine "Minna" Planer. After the disaster of Das Liebesverbot he followed her to Königsberg where she helped him to get an engagement at the theatre.[23] The two married in Königsberg on 24 November 1836.[24] In June 1837 Wagner moved to Riga (then in the Russian Empire), where he became music director of the local opera.[25] Minna had recently left Wagner for another man[26] but Richard took her back;[27] this was but the first débâcle of a troubled marriage that would end in misery three decades later.

By 1839, the couple had amassed such large debts that they fled Riga to escape from creditors;[28] debt would plague Wagner for most of his life.[29] During their flight, they and their Newfoundland dog Robber took a stormy sea passage to London,[30] from which Wagner drew the inspiration for The Flying Dutchman (with a story based on a sketch by Heinrich Heine).[31]

The Wagners spent 1839 to 1842 in Paris, where Richard made a scant living writing articles and arranging operas by other composers, largely on behalf of the Schlesinger publishing house. However, he also completed his third and fourth operas Rienzi and The Flying Dutchman during this stay.[32] His relief on leaving Paris for Dresden was recorded in his "Autobiographic Sketch" of 1842, "For the first time I saw the Rhine — with hot tears in my eyes, I, poor artist, swore eternal fidelity to my German fatherland."[33]

Dresden

Wagner had completed writing Rienzi in 1840. Largely through the strong support of Giacomo Meyerbeer,[34] it was accepted for performance by the Dresden Court Theatre (Hofoper) in the German state of Saxony. In 1842, Wagner moved to Dresden, where Rienzi was staged to considerable acclaim on 20 October.[35] Wagner lived in Dresden for the next six years, eventually being appointed the Royal Saxon Court Conductor.[36] During this period, he staged there The Flying Dutchman (2 January 1843)[37] and Tannhäuser (19 October 1845),[38] the first two of his three middle-period operas. Wagner also mixed with artistic circles in Dresden, including the composer Ferdinand Hiller and the architect Gottfried Semper.[39]

The Wagners' stay at Dresden was brought to an end by Richard's involvement in leftist politics. A nationalist movement was gaining force in the states of the German Confederation, calling for constitutional freedoms and the unification of Germany as one nation state. Richard Wagner played an enthusiastic role in the socialist wing of this movement, regularly receiving guests who included the radical editor August Röckel, and the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. He was also influenced by the ideas of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon.[40] Widespread discontent in Dresden came to a head in April 1849, when King Frederick Augustus II of Saxony rejected a new constitution. The May Uprising broke out, in which Wagner played a minor supporting role. The incipient revolution was quickly crushed by an allied force of Saxon and Prussian troops, and warrants were issued for the arrest of the revolutionaries. Wagner had to flee, first visiting Paris and then settling in Zurich.[41]

Exile, Schopenhauer and Mathilde Wesendonck

Wagner spent the next twelve years in exile. He had completed Lohengrin, the last of his middle-period operas before the Dresden uprising, and now wrote desperately to his friend Franz Liszt to have it staged in his absence. Liszt, who proved to be a true friend, eventually conducted the premiere in Weimar in August 1850.[42]

Nevertheless, Wagner found himself in grim personal straits, isolated from the German musical world and without any income to speak of. Before leaving Dresden, he had drafted a scenario that would eventually become the four opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen. He initially wrote the libretto for a single opera, Siegfrieds Tod (Siegfried's Death) in 1848. After arriving in Zurich he expanded the story to include an opera Der junge Siegfried (Young Siegfried) exploring the hero's background. He completed the text of the cycle by writing the libretti for Die Walküre and Das Rheingold and revising the other libretti to agree with his new concept, completing them in 1852.[43] Meanwhile, his wife Minna, who had disliked the operas he had written after Rienzi, was falling into a deepening depression and then Wagner himself fell victim to ill-health, according to Ernest Newman "largely a matter of overwrought nerves", which made it difficult for him to continue writing.[44]

Wagner's primary published output during his first years in Zurich was a set of notable essays: "The Art-Work of the Future" (1849), in which he described a vision of opera as Gesamtkunstwerk, or "total work of art", in which the various arts such as music, song, dance, poetry, visual arts, and stagecraft were unified; "Judaism in Music" (1850), a tract directed against Jewish composers; and "Opera and Drama" (1851), which described the aesthetics of drama which he was using to create the Ring operas.

Wagner began composing Das Rheingold in November 1853, following it immediately with Die Walküre in 1854. He then began work on the third opera, now called Siegfried, in 1856 but finished only the first two acts before deciding to put the work aside to concentrate on a new idea: Tristan und Isolde.[45]

Wagner had two independent sources of inspiration for Tristan und Isolde. The first came to him in 1854, when his poet friend Georg Herwegh introduced him to the works of the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. Wagner would later call this the most important event of his life.[46] His personal circumstances certainly made him an easy convert to what he understood to be Schopenhauer's philosophy, a deeply pessimistic view of the human condition. He would remain an adherent of Schopenhauer for the rest of his life, even after his fortunes improved.[47]

One of Schopenhauer's doctrines was that music held a supreme role in the arts. He claimed that music is the direct expression of the world's essence, which is blind, impulsive will.[48] Wagner quickly embraced this claim, which must have resonated strongly despite its contradiction of his previous view, expressed in "Opera and Drama", that the music in opera had to be subservient to the drama. Wagner scholars have since argued that this Schopenhauerian influence caused Wagner to assign a more commanding role to music in his later operas, including the latter half of the Ring cycle, which he had yet to compose.[49] Many aspects of Schopenhauerian doctrine undoubtedly found their way into Wagner's subsequent libretti. For example, the self-renouncing cobbler-poet Hans Sachs in Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, generally considered Wagner's most sympathetic character, although based loosely on a historical person, is a quintessentially Schopenhauerian creation.[50]

Wagner's second source of inspiration was the poet-writer Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of the silk merchant Otto Wesendonck. Wagner met the Wesendoncks in Zurich in 1852. Otto, a fan of Wagner's music, placed a cottage on his estate at Wagner's disposal.[51] During the course of the next five years, the composer was eventually to become infatuated with his patron's wife. Though Mathilde seems to have returned some of his affections, she had no intention of jeopardizing her marriage. Nevertheless, the affair inspired Wagner to put aside his work on the Ring cycle (which would not be resumed for the next twelve years) and began work on Tristan,[52] based on the Arthurian love story Tristan and Iseult. While planning the opera, Wagner composed the Wesendonck Lieder, five songs for voice and piano setting poems by Mathilde. Two of these settings are explicitly subtitled by Wagner as 'studies for Tristan und Isolde '.[53]

The uneasy affair collapsed in 1858, when Minna intercepted a letter from Wagner to Mathilde.[54] However, Wagner continued his correspondence with Mathilde and his friendship with (and support by) her husband Otto. After the resulting confrontation, Wagner left Zurich alone, bound for Venice, where he sojourned in the Palazzo Giustinian.[55] The following year, he once again moved to Paris to oversee production of a new revision of Tannhäuser, staged thanks to the efforts of his patron Princess Pauline von Metternich, whose husband was the Austrian ambassador in Paris. The performances of the Paris Tannhäuser in 1861 were famously a fiasco, brought about not only by the conservative tastes of the Jockey Club, but also by people of influence who wanted to use the occasion as a veiled political protest against the pro-Austrian policies of Napoleon III.[56] The work was withdrawn after the third performance and Wagner left Paris soon after.[57]

The political ban which had been placed on Wagner in Germany after he had fled Dresden was lifted in 1861. The composer settled in Biebrich in Prussia,[58] where he began work on Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, the idea for which had come during a visit he had made to Venice with the Wesendoncks.[59] Despite the failure of Tannhäuser in Paris, the possibility that Der Ring des Nibelungen would never be finished, and Wagner's unhappy personal life at the time of writing it, this opera is his only mature comedy.

Between 1861 and 1864 Wagner tried to have Tristan und Isolde produced in Vienna.[60] Despite numerous rehearsals, the opera remained unperformed, and gained a reputation as being "impossible", which further added to Wagner's financial woes.[61]

In 1862, Wagner finally parted from Minna,[62] though he (or at least his creditors) continued to support her financially until her death in 1866. He claimed to be unable to travel to her funeral due to an "inflamed finger".[63]

Patronage of King Ludwig II

Wagner's fortunes took a dramatic upturn in 1864, when King Ludwig II succeeded to the throne of Bavaria at the age of 18. The young king, an ardent admirer of Wagner's operas since childhood, had the composer brought to Munich.[64] He settled Wagner's considerable debts,[65] and proposed to stage Tristan, Die Meistersinger, the Ring, and the other operas Wagner planned.[66] Wagner also began to dictate his autobiography, Mein Leben, at the King's request.[67] To Wagner, it seemed significant that his rescue by Ludwig coincided with his learning the news of the death of his supposed enemy Giacomo Meyerbeer, noting ungratefully that "this operatic master, who had done me so much harm, should not have lived to see this day".[68]

After grave difficulties in rehearsal, Tristan und Isolde premiered at the National Theatre in Munich on 10 June 1865, the first Wagner premiere in almost 15 years. (The premiere had been scheduled for 15 May, but had been delayed by bailiffs acting for Wagner's creditors;[69] and also because the Isolde, Malvina Schnorr von Carolsfeld, was hoarse and needed time to recover). The conductor of this premiere was Hans von Bülow, whose wife Cosima had given birth in April that year to a daughter, named Isolde, the child not of von Bülow but of Wagner.[70]

Cosima was 24 years younger than Wagner and was herself illegitimate, the daughter of the Countess Marie d'Agoult, who had left her husband for Franz Liszt.[71] Liszt disapproved of his daughter seeing Wagner, though the two men were friends.[72] The indiscreet affair scandalized Munich, and to make matters worse, Wagner fell into disfavour among members of the court, who were suspicious of his influence on the king. In December 1865, Ludwig was finally forced to ask the composer to leave Munich.[73] He apparently also toyed with the idea of abdicating in order to follow his hero into exile, but Wagner quickly dissuaded him.[74]

Ludwig installed Wagner at the Villa Tribschen, beside Switzerland's Lake Lucerne.[75] Die Meistersinger was completed at Tribschen in 1867, and premièred in Munich on 21 June the following year.[76] In October, Cosima finally convinced Hans von Bülow to grant her a divorce, but this did not materialize until after she had two more children with Wagner; another daughter, named Eva, after the heroine of Meistersinger, and a son Siegfried, named for the hero of the Ring. Minna Wagner had died the previous year and so Richard and Cosima were now able to marry. The wedding took place on 25 August 1870.[77] On Christmas Day of that year, Wagner arranged a surprise performance of the Siegfried Idyll for Cosima's birthday.[78] The marriage to Cosima lasted to the end of Wagner's life.

Bayreuth

Wagner, settled into his newfound domesticity, turned his energies toward completing the Ring cycle. At Ludwig's insistence, "special previews" of the first two works of the cycle, Das Rheingold and Die Walküre, were performed at Munich in 1869 and 1870,[79] but Wagner wanted the complete cycle to be performed in a new, specially designed opera house.

In 1871, he decided on the small town of Bayreuth as the location of his new opera house.[80] The Wagners moved there the following year, and the foundation stone for the Bayreuth Festspielhaus ("Festival Theatre") was laid.[81] In order to raise funds for the construction, "Wagner Societies" were formed in several cities,[82] and Wagner himself began touring Germany conducting concerts.[83] However, sufficient funds were raised only after King Ludwig stepped in with another large grant in 1874.[84] Later that year, the Wagners moved into their permanent home at Bayreuth, a villa that Richard dubbed Wahnfried ("Peace/freedom from delusion/madness", in German).[85] The expenses of Bayreuth and of Wahnfried, however, meant that Wagner still sought other sources of income by conducting or taking on commissions like the Centennial March for America.[86]

The Festspielhaus finally opened on 13 August 1876 with Das Rheingold, now taking its place as the first evening of the premiere of the complete Ring cycle,[87] and has continued to be the site of the Bayreuth Festival ever since; the Festival has been overseen since 1973 by the Richard-Wagner-Stiftung (Richard Wagner Foundation), the members of which include a number of Wagner's descendants.[88]

Last years

Following the first Bayreuth Festival, Wagner began work on Parsifal, his final opera. The composition took four years, much of which Wagner spent in Italy for health reasons.[89] During this period he also wrote a series of essays, including some reactionary writings on religion and art which recanted his earlier views. Many of these—including "Religion and Art" (1880) and "Hero-dom and Christendom" (1881)[90]—appeared in the journal Bayreuther Blätter,[91] founded in 1880 by Wagner and Hans von Wolzogen for Wagnerite visitors to Bayreuth.[92]

Wagner completed Parsifal in January 1882, and a second Bayreuth Festival was held for the new opera, which was premiered on 26 May.[93] Wagner was by this time extremely ill, having suffered through a series of increasingly severe angina attacks.[94] During the sixteenth and final performance of Parsifal on 29 August, he secretly entered the pit during Act III, took the baton from conductor Hermann Levi, and led the performance to its conclusion.[95]

After the Festival, the Wagner family journeyed to Venice for the winter. Wagner died of a heart attack at the age of 69 on 13 February 1883 at Ca' Vendramin Calergi, a 16th century palazzo on the Grand Canal.[96] Franz Liszt's two pieces for piano solo titled La lugubre gondola evoke the passing of a black-shrouded funerary gondola bearing Richard Wagner's remains over the Grand Canal.[97] Wagner was buried in the garden of the Villa Wahnfried in Bayreuth.[98]

Works

Opera

Wagner's operatic works are his primary artistic legacy.

Unlike other opera composers, who generally left the task of writing the libretto (the text and lyrics) to others, Wagner wrote his own libretti, which he referred to as "poems".[99] Further, Wagner developed a compositional style in which the orchestra's role is equal to that of the singers. The orchestra's dramatic role, in the later operas, includes the use of leitmotivs, musical themes that can be interpreted as announcing specific characters, locales, and plot elements; their complex interweaving and evolution illuminates the progression of the drama.[100] Ultimately he urged a new concept of opera often referred to as "music drama", (although he did not use or sanction this term himself)[101] in which all musical poetic and dramatic elements were to be fused together—the Gesamtkunstwerk.[102]

Wagner's operas are typically characterized as belonging to three chronological periods.

Early stage (to 1842)

Wagner's first attempt at an opera, at the age of 17, was Die Laune des Verliebten.[18] This was abandoned at an early stage of composition, as was Die Hochzeit (The Wedding), on which Wagner worked in 1832.[18] Wagner then completed Die Feen (The Fairies, 1833, unperformed in the composer's lifetime)[20] and Das Liebesverbot (The Ban on Love, 1836, taken off after its first performance),[22] before working on the aborted singspiel Männerlist grösser als Frauenlist (Men's cunning greater than women's).[18] This was followed by Rienzi (1842), Wagner's first opera to be successfully staged.[103] The compositional style of these early works was conventional—the relatively more sophisticated Rienzi showing the clear influence of Meyerbeerean Grand Opera—and did not exhibit the innovations that would mark Wagner's place in musical history. Later in life, Wagner said that he did not consider these immature works to be part of his oeuvre, and none of them have ever been performed at the Wagnerian Bayreuth Festival.[104] These works have been only rarely revived in the last hundred years, although the overture to Rienzi is an occasional concert piece.

Middle stage (1843–51)

Wagner's middle stage output begins to show the deepening of his powers as a dramatist and composer. This period began with Der fliegende Holländer (1843) (The Flying Dutchman), followed by Tannhäuser (1845) and Lohengrin (1850). These three operas reinforced the reputation among the public in Germany and beyond that Wagner had begun to establish for himself with Rienzi. However, during his exile following the 1849 May Uprising in Dresden he began to reconsider his entire concept of opera and eventually decided, as explained during a series of essays between 1849 and 1852, that these operas did not represent what he hoped to achieve.[105] In his essay A Communication to My Friends (1851), intended as a preface to the printed libretti of the Dutchman, Tannhäuser and Lohengrin, Wagner (to the confusion of many of his friends, since at that time Lohengrin had not even been staged) effectively disowned these operas and declared his intention to strike out in new directions.

I shall never write an Opera more. As I have no wish to invent an arbitrary title for my works, I will call them Dramas [...]

I propose to produce my myth in three complete dramas, preceded by a lengthy Prelude (Vorspiel). [...]

At a specially-appointed Festival, I propose, some future time, to produce those three Dramas with their Prelude, in the course of three days and a fore-evening. The object of this production I shall consider thoroughly attained, if I and my artistic comrades, the actual performers, shall within these four evenings succeed in artistically conveying my purpose to the true Emotional (not the Critical) Understanding of spectators who shall have gathered together expressly to learn it. [...][106]

Wagner later reconciled himself to the works of this period, though he reworked both Dutchman and Tannhäuser on several occasions.[107] The three operas are the earliest works included into the Bayreuth canon, the list of mature operas which Cosima put on at the Bayreuth Festival after Wagner's death in accordance with his wishes.[108] They continue to be regularly performed today and have been frequently recorded. They show increasing mastery in stagecraft, orchestration and atmosphere.[109]

Late stage (1851–1882)

Starting the Ring

Main articles: Der Ring des Nibelungen, Der Ring des Nibelungen: Composition of the music and Der Ring des Nibelungen: Composition of the poem

Wagner's late dramas are considered his masterpieces. Der Ring des Nibelungen, commonly referred to as the Ring cycle, is a set of four operas based loosely on figures and elements of Germanic mythology—particularly from the later Norse mythology—notably the Old Norse Poetic Edda and Volsunga Saga, and the Middle High German Nibelungenlied.[110] They were also influenced by Wagner's concepts of ancient Greek drama, in which tetralogies were a component of Athenian festivals, and which he had amply discussed in his essay "Oper und Drama"[111]

The first two components of the Ring cycle were Das Rheingold (The Rhinegold) (completed 1854) and Die Walküre (The Valkyrie) (completed 1856). In Das Rheingold, with its "relentlessly talky "realism" [and] the absence of lyrical "numbers"",[112] Wagner came very close to the pure musical ideals of his 1849–51 essays. Die Walküre, with Siegmund's almost full-blown aria (Winterstürme) in the first act, and the quasi-choral appearance of the Valkyries themselves, shows more 'operatic' traits, but has been assessed as "the music drama that most satisfactorily embodies the theoretical principles of "Oper und Drama". A thoroughgoing synthesis of poetry and music is achieved without any notable sacrifice in musical expression".[113]

Tristan und Isolde and Die Meistersinger

While still composing the Ring, (leaving the third Ring opera Siegfried uncompleted for the while), Wagner paused between 1857 and 1864 to compose the tragic love story Tristan und Isolde and his only mature comedy Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg (The Mastersingers of Nuremberg), two works which are also part of the regular operatic canon.[114]

Tristan und Isolde uses a story line deriving from the poem Tristan und Isolt by the 13th century poet Gottfried von Strassburg. Wagner noted that "its all-pervading tragedy […] impressed me so deeply that I felt convinced it should stand out in bold relief, regardless of minor details." This impact, together with his discovery of the philosophy of Schopenhauer in October 1854, led Wagner to find himself in a "serious mood created by Schopenhauer, which was trying to find ecstatic expression. It was some such mood that inspired the conception of a Tristan und Isolde."[115] Wagner half-parodied the powerful erotic atmosphere of the opera in a letter to Mathilde Wesendonck:

Child! This Tristan is turning into something terrible. This final act!!! – I fear the opera will be banned […] only mediocre performances can save me! Perfectly good ones will be bound to drive people mad.[116]

The work was first performed in Munich on 10 June 1865, conducted by Hans von Bülow.

Tristan is often granted a special place in musical history. It has been described as "fifty years ahead of its time" because of its chromaticism, long-held discords, unusual orchestral colouring and harmony, and use of polyphony.[117] Wagner himself felt that his musico-dramatical theories were most perfectly realised in this work with its use of "the art of transition" between dramatic elements and the balance achieved between vocal and orchestral lines.[117]

Die Meistersinger was originally conceived by Wagner in 1845 as a sort of comic pendant to Tannhäuser.[118] It was first performed in Munich, again under the baton of Bülow, on 21 June 1868, its accessibility making it an immediate success. It is "a rich, perceptive music drama widely admired for its warm humanity";[119] but because of its strong German nationalist overtones, it is also held up by some as an example of Wagner's reactionary politics and antisemitism.[120]

Completing the Ring

When Wagner returned, with the added experience of composing Tristan and Die Meistersinger, to write the music for the last act of Siegfried and for Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods), as the final part of the Ring was eventually called, his style had changed once again to one more recognisable as 'operatic' (though thoroughly stamped with his own originality as a composer, and suffused with leitmotivs) than the aural world of Rheingold and Walküre.[121] This was in part because the libretti of the four 'Ring' operas had been written in reverse order, so that the book for Götterdämmerung was conceived more 'traditionally' than that of Rheingold;[122] still, the self-imposed strictures of the Gesamtkunstwerk had become relaxed. As George Bernard Shaw sardonically (and slightly unfairly)[123] noted,

- And now, O Nibelungen Spectator, pluck up; for all allegories come to an end somewhere[...] The rest of what you are going to see is opera, and nothing but opera. Before many bars have been played, Siegfried and the wakened Brynhild, newly become tenor and soprano, will sing a concerted cadenza; plunge on from that to a magnificent love duet[...]The work which follows, entitled Night Falls On The Gods [Shaw's translation of Götterdämmerung], is a thorough grand opera.[124]

However, the differences are also because of Wagner's development as a composer during the period in which he composed Tristan, Meistersinger and also the Paris version of Tannhäuser.[125] From Act III of Siegfried onwards, the Ring becomes chromatic, and both harmonically more complex and more developmental in its treatment of leitmotifs.[126]

Having taken 26 years from the first draft of a libretto in 1848 until the completion of Götterdämmerung in 1874, the Ring represents in all about 15 hours of performance, the only undertaking of such size to be regularly represented on the world's stages.[127]

Parsifal

Wagner's final opera, Parsifal (1882), which was his only work written especially for his Festspielhaus in Bayreuth and which is described in the score as a "Bühnenweihfestspiel" (festival play for the consecration of the stage), has a storyline suggested by elements of the legend of the Holy Grail. It also however carries elements of Buddhist renunciation suggested by Wagner's readings of Schopenhauer.[128] Wagner described it to Cosima as his "last card".[129] The composer's treatment of Christianity in the opera, its eroticism, and its supposed relationship to ideas of German nationalism (and of antisemitism) have continued to render it controversial for non-musical reasons.[130] However, musically it has been held to represent a continuing development of the composer's style, with "a diaphanous score of unearthly beauty and refinement".[131]

Non-operatic music

Apart from his operas, Wagner composed relatively few pieces of music. These include a single symphony (written at the age of 19), a Faust Overture (the only completed part of an intended symphony on the subject), and some overtures, choral and piano pieces.[132] His most commonly performed work not drawn from an opera is the Siegfried Idyll, a piece for chamber orchestra written for the birthday of his second wife, Cosima. The Idyll draws on several motifs from the Ring cycle, though it is not part of the Ring.[133] Also performed are the Wesendonck Lieder for voice and piano, properly known as Five Songs for a Female Voice, which were composed for Mathilde Wesendonck while Wagner was working on Tristan.[53] An oddity is the American Centennial March of 1876, commissioned by the city of Philadelphia (on the recommendation of conductor Theodore Thomas, who was subsequently very disappointed with the work when it arrived) for the opening of the Centennial Exposition, for which Wagner was paid $5,000.[134]

The rarely performed Das Liebesmahl der Apostel (The Love Feast of the Apostles) is a piece for male choruses and orchestra, composed in 1843. Wagner, who had been elected at the beginning of the year to the committee of a cultural association in the city of Dresden, received a commission to evoke the theme of Pentecost. The premiere took place at the Dresdner Frauenkirche on 6 July 1843, and was performed by around a hundred musicians and almost 1,200 singers. The concert was very well received.[135]

After completing Parsifal, Wagner expressed his intention to turn to the writing of symphonies,[136] and several sketches dating from the late 1870s and early 1880s have been identified as work toward this end.[137]

The overtures and orchestral passages from Wagner's middle and late-stage operas are commonly played as concert pieces. For most of these, Wagner wrote short passages to conclude the excerpt so that it does not end abruptly. Another familiar extract is the "Bridal Chorus" from Lohengrin, frequently played as the bride's processional wedding march in English-speaking countries.[138]

Writings

Wagner was an extremely prolific writer, authoring hundreds of books, poems, and articles, as well as voluminous correspondence, throughout his life. His writings covered a wide range of topics, including politics, philosophy, and detailed analyses of his own operas. Essays of note include "Art and Revolution" (1849), "Opera and Drama" (1851), an essay on the theory of opera, and "Das Judenthum in der Musik" ("Jewishness in Music", 1850), a polemic directed against Jewish composers in general, and Giacomo Meyerbeer in particular. He also wrote various autobiographical works, including "My Life" (1880). In his later years Wagner became a vociferous opponent of experimentation on animals and in 1879 he published an open letter, "Against Vivisection", in support of the animal rights activist Ernst von Weber.[139]

There have been several editions of Wagner's writings, including a centennial edition in German edited by Dieter Borchmeyer (which however omitted the essay "Das Judenthum in der Musik")[140] The English translations of Wagner's prose in 8 volumes by W. Ashton Ellis, (1892–99), are still in print and commonly used, despite their deficiencies.[141] A complete edition of Wagner's correspondence, (estimated to amount to between 10,000 and 12,000 surviving items), of which the first volume appeared in 1967, is still under way.[142]

Influence and legacy

Influence on music

Wagner's later musical style, with its unprecedented exploration of emotional expression, introduced new ideas in harmony, melodic process (leitmotiv) and operatic structure. Notably from Tristan und Isolde onwards, he explored the limits of the traditional tonal system that gave keys and chords their identity, pointing the way to atonality in the 20th century. Some music historians date the beginning of modern classical music to the first notes of Tristan, the so-called Tristan chord.[143][144]

In his lifetime, and for some years after, Wagner inspired fanatical devotion. For a long period, many composers were inclined to align themselves with or against Wagner's music. Anton Bruckner and Hugo Wolf were indebted to him especially, as were César Franck, Henri Duparc, Ernest Chausson, Jules Massenet, Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Hans Pfitzner and dozens of others.[145] Gustav Mahler said, "There was only Beethoven and Richard [Wagner] – and after them, nobody". The twentieth century harmonic revolutions of Claude Debussy and Arnold Schoenberg (tonal and atonal modernism, respectively) have often been traced back to Tristan and Parsifal.[146] The Italian form of operatic realism known as verismo owed much to Wagnerian reconstruction of musical form.[147]

Wagner made a major contribution to the principles and practice of conducting. His essay "About Conducting" (1869)[148] advanced the earlier work of Hector Berlioz and proposed that conducting was a means by which a musical work could be re-interpreted, rather than simply a mechanism for achieving orchestral unison. He exemplified this approach in his own conducting, which was significantly more flexible than the disciplined approach of Mendelssohn; in his view this also justified practices which would today be frowned upon, such as the rewriting of scores.[149] Wilhelm Furtwängler felt that Wagner and von Bülow, through their interpretative approach, inspired a whole new generation of conductors (including Furtwängler himself).[150]

Influence on literature, philosophy and the visual arts

Wagner's influence on literature and philosophy is significant.

[Wagner's] protean abundance meant that he could inspire the use of literary motif in many a novel employing interior monologue; [...] the Symbolists saw him as a mystic hierophant; the Decadents found many a frisson in his work.[151]

Friedrich Nietzsche was part of Wagner's inner circle during the early 1870s, and his first published work The Birth of Tragedy proposed Wagner's music as the Dionysian rebirth of European culture in opposition to Apollonian rationalist decadence. Nietzsche broke with Wagner following the first Bayreuth Festival, believing that Wagner's final phase represented a pandering to Christian pieties and a surrender to the new German Reich. Nietzsche expressed his displeasure with the later Wagner in "The Case of Wagner" and "Nietzsche contra Wagner".[152]

Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine worshipped Wagner.[153] Edouard Dujardin, whose influential novel Les lauriers sont coupés is in the form of an interior monologue inspired by Wagnerian music, founded a journal dedicated to Wagner, La Revue Wagnérienne, to which J. K. Huysmans and Téodor de Wyzewa contributed.[154]

In the twentieth century, W. H. Auden once called Wagner "perhaps the greatest genius that ever lived",[155] while Thomas Mann[152] and Marcel Proust[156] were heavily influenced by him and discussed Wagner in their novels. He is discussed in some of the works of James Joyce.[157] Wagnerian themes inhabit T. S. Eliot's The Waste Land, which contains lines from Tristan und Isolde and Götterdämmerung and Verlaine's poem on Parsifal.[158] Many of Wagner's concepts, including his speculation about dreams, predated their investigation by Sigmund Freud.[159] Wagner had publicly analysed the Oedipus myth before Freud was born in terms of its psychological significance, insisting that incestuous desires are natural and normal, and perceptively exhibiting the relationship between sexuality and anxiety.[160] George Groddeck considered the Ring as the first manual of psychoanalysis[161] In a long list of other major cultural figures influenced by Wagner, Bryan Magee includes D. H. Lawrence, Aubrey Beardsley, Romain Rolland, Gérard de Nerval, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Rainer Maria Rilke and numerous others.[162]

Opponents and supporters

Not all reaction to Wagner was positive. For a time, German musical life divided into two factions, Wagner's supporters and those of Johannes Brahms; the latter, with the support of the powerful critic Eduard Hanslick (of whom Beckmesser in Meistersinger is in part a caricature) championed traditional forms and led the conservative front against Wagnerian innovations.[163] They were supported by the conservative leanings of some German music schools, including the Conservatory at Leipzig under Ignaz Moscheles and that at Cologne under the direction of Ferdinand Hiller.[164] Even those who, like Debussy, opposed him ("that old poisoner") could not deny Wagner's influence. Indeed, Debussy was one of many composers, including Tchaikovsky, who felt the need to break with Wagner precisely because his influence was so unmistakable and overwhelming. 'Golliwogg's Cakewalk' from Debussy's Children's Corner piano suite contains a deliberately tongue-in-cheek quotation from the opening bars of Tristan. Others who resisted Wagner's attraction included Gioachino Rossini ("Wagner has wonderful moments, and dreadful quarters of an hour").[165] In the 20th century Wagner's music was parodied by, among others Paul Hindemith and Hans Eisler.[166]

Wagner's followers (known as Wagnerians or Wagnerites)[167] have formed many Societies dedicated to the life, works, and operas of Wagner. Societies include: The Toronto Wagner Society, the Wagner Society of New York, the Wagner Society of the United Kingdom, The Wagner Society of New Zealand, The Wagner Society of Northern California, etc.

Theatre design and practice

Wagner was responsible for several theatrical innovations developed at the Bayreuth Festspielhaus (for the design of which he appropriated some of the ideas of his former colleague, Gottfried Semper, which he had solicited for a proposed new opera house at Munich).[168] These innovations include darkening the auditorium during performances, and placing the orchestra in a pit out of view of the audience.[169]

Influence on film

Wagner's concept of the use of leitmotifs and integrated musical expression has been an influence on many 20th and 21st century film scores. The critic Theodor Adorno has noted that the Wagnerian leitmotif "leads directly to cinema music where the sole function of the leitmotiv is to announce heroes or situations so as to allow the audience to orient itself more easily".[170] Some film scores have used Wagnerian themes (e.g. Francis Ford Coppola's Apocalypse Now which features a version of the Ride of the Valkyrie). Most of Trevor Jones's soundtrack to John Boorman's Arthurian film Excalibur is from Wagner's operas.[171] The 2011 films A Dangerous Method (dir. David Cronenberg) and Melancholia (dir. Lars von Trier) both utilise music by Wagner.[172]

Wagner has also been the subject of many biographical films. (See article List of films about Richard Wagner).

Influence on popular music

The rock composer Jim Steinman created what he called Wagnerian Rock. Heavy metal music is also said by some to show the influence of Wagner (as well as other classical composers). In Germany Rammstein and Joachim Witt who has named three of his albums Bayreuth, claim inspiration from Wagner's music. German electronic composer Klaus Schulze dedicated his 1975 album Timewind to Wagner's death (two 30-min tracks, "Bayreuth Return" and "Wahnfried 1883"). He also used the alias Richard Wahnfried for a part of his discography. Slovenian avant-garde group Laibach created the sonic suite VolksWagner in 2009 in collaboration with the Slovenian Radio Symphony Orchestra and composer-conductor Izidor Leitinger, using material from Tannhäuser, the Siegfried Idyll and The Ride of the Valkyries. Phil Spector's wall of sound recording technique was, it has been claimed, heavily influenced by Wagner.[173]

Film and stage portrayals

Several of the film portrayals of Richard Wagner include: Alan Badel in Magic Fire (1955); Lyndon Brook in Song Without End (1960); Trevor Howard in Ludwig (1972); Paul Nicholas in Lisztomania (1975); and Richard Burton in Wagner (1983).

Jonathan Harvey's opera, Wagner Dream (2007), interwines the events surrounding Wagner's death with the story of Wagner's uncompleted opera sketch Die Sieger (The Victors).

Controversies

Wagner's operas, writings, his politics, beliefs and unorthodox lifestyle made him a controversial figure during his lifetime. Following Wagner's death, the debate about his ideas and their interpretation, particularly in Germany during the 20th century, continued to make him politically and socially controversial in a way that other great composers are not. Much heat is generated by Wagner's comments on Jews, which continue to influence the way that his works are regarded, and by the essays he wrote on the nature of race from 1850 onwards, and their putative influence on the antisemitism of Adolf Hitler.

Racism and antisemitism

Wagner's writings on race and against Jews[174] reflected some trends of thought in Germany during the 19th century.

Under a pseudonym in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, Wagner published the essay "Das Judenthum in der Musik" in 1850 (originally translated as "Judaism in Music", by which name it is still known, but better rendered as "Jewishness in Music"). The essay attacked Jewish contemporaries (and rivals) Felix Mendelssohn and Giacomo Meyerbeer, and accused Jews of being a harmful and alien element in German culture. Wagner stated the German people were repelled by Jews' alien appearance and behaviour: "with all our speaking and writing in favour of the Jews' emancipation, we always felt instinctively repelled by any actual, operative contact with them." He argued that because Jews had no connection to the German spirit, Jewish musicians were only capable of producing shallow and artificial music. They therefore composed music to achieve popularity and, thereby, financial success, as opposed to creating genuine works of art.[175] Wagner republished the pamphlet under his own name in 1869, with an extended introduction, leading to several public protests at the first performances of Die Meistersinger. He repeated similar views in later articles, such as "What is German?" (1878, but based on a draft written in the 1860s).[176]

Some biographers[177] have suggested that antisemitic stereotypes are also represented in Wagner's operas. The characters of Mime in the Ring, Sixtus Beckmesser in Die Meistersinger, and Klingsor in Parsifal are sometimes claimed as Jewish representations, though they are not explicitly identified as such in the libretto. Moreover, in all of Wagner's many writings about his works, there is no mention of an intention to caricature Jews in his operas; nor does any such notion appear in the diaries written by Cosima Wagner, which record his views on a daily basis over a period of eight years.[178]

Despite his very public views on Jews, throughout his life Wagner had Jewish friends, colleagues and supporters.[179] In his autobiography, Mein Leben, Wagner mentions many friendships with Jews, referring to that with Samuel Lehrs in Paris as "one of the most beautiful friendships of my life."[180]

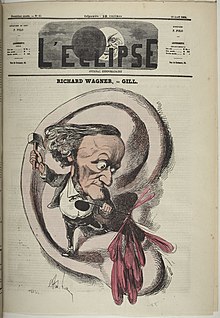

The topic of Wagner and the Jews is further complicated by allegations, which may have been credited by Wagner himself, that he himself was of Jewish ancestry, via his supposed father Geyer.[181] In reality, Geyer was not of Jewish descent, nor were either of Wagner's official parents. References to Wagner's supposed 'Jewishness' were made frequently in cartoons of the composer in the 1870s and 1880s, and more explicitly by Friedrich Nietzsche in his essay "The Wagner Case", where he wrote "a Geyer [vulture] is almost an Adler [eagle]".[182] (Both 'Geyer' and 'Adler' were common Jewish surnames.)

Some biographers have asserted that Wagner in his final years came to believe in the racialist philosophy of Arthur de Gobineau, and according to Robert Gutman, this is reflected in the opera Parsifal.[183] Other biographers such as Lucy Beckett[184] believe that this is not true. Wagner showed no significant interest in Gobineau until 1880, when he read Gobineau's "An Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races".[185] Wagner had completed the libretto for Parsifal by 1877, and the original drafts of the story date back to 1857. Wagner's writings of his last years indicate some interest in Gobineau's idea that Western society was doomed because of miscegenation between "superior" and "inferior" races.[186]

Other interpretations

Wagner's ideas were amenable to socialist interpretations, which is not surprising given the composer's revolutionary inclinations in the 1840s, when many of his ideas on art were being formulated. Thus for example, George Bernard Shaw wrote in The Perfect Wagnerite (1883):

[Wagner's] picture of Niblunghome [Shaw's anglicization of Nibelheim, the empire of Alberich in the Ring Cycle] under the reign of Alberic is a poetic vision of unregulated industrial capitalism as it was made known in Germany in the middle of the nineteenth century by Engels's Condition of the Laboring Classes in England.[187]

Left-wing interpretations of Wagner also inform the writings of Theodor Adorno amongst other Wagner critics.[188] Walter Benjamin gave Wagner as an example of "bourgeois false consciousness", alienating art from its social context.[189]

The writer Robert Donington has produced a detailed, if controversial, Jungian interpretation of the Ring cycle. Others have also applied psychoanalytical techniques to Wagner's life and works.[190]

Others have sought to place Wagner's work in a more generalised sociohistoric framework. For example, Ehrhard Bahr suggests that 'Wagner provided the middle class with a medium to transfer its familial and political conflicts into a myth of supposedly common Germanic past'.[191]

Nazi appropriation

Adolf Hitler was an admirer of Wagner's music and saw in his operas an embodiment of his own vision of the German nation. There continues to be debate about the extent to which Wagner's views might have influenced Nazi thinking.[192] The Nazis used those parts of Wagner's thought that were useful for propaganda and ignored or suppressed the rest.[193] Although Hitler himself was an ardent fan of "the Master", many in the Nazi hierarchy were not and, according to the historian Richard Carr, resented attending these lengthy epics at Hitler's insistence.[194]

There are claims that music of Wagner was used at the Dachau concentration camp in 1933/4 to 'reeducate' political prisoners by exposure to 'national music'.[195] However there seems to be no evidence to support claims, sometimes made,[196] that his music was played at Nazi death camps during the Second World War.[197]

Because of the associations of Wagner with antisemitism and Nazism, the performance of his music in the State of Israel has been a source of controversy.[198]

References

- Notes

- ^ Wagner (1992) 3

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 12

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 6

- ^ Guttman (1990), p. 7 and n.

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 9

- ^ Wagner (1992) 5

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 32–33

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 45–55

- ^ Wagner (1992) 25–27. This sketch is referred to alternatively as Leubald und Adelaide.

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 63, 71

- ^ Wagner (1992) 35–36

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 62

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 76–77

- ^ Millington (1992) 133

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 85–86

- ^ Millington (1992) 309

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 95

- ^ a b c d Millington (1992) 321

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 98

- ^ a b Millington (1992) 271–273

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 173

- ^ a b Millington (1992) 273–274

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 212

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 214

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 226–227

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 217

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 229

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 242–243

- ^ Millington (1992) 116–118

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 249–250

- ^ Millington (1992) 277

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 268–324

- ^ Wagner (1994c) 19

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 316

- ^ Millington (1992) 274

- ^ Newman (1976) I, 325–509

- ^ Millington (1992) 276

- ^ Millington (1992) 279

- ^ Millington (1992) 31

- ^ Millington (1992) 140

- ^ Wagner (1992) 417–420. Röckel and Bakunin failed to escape and endured long terms of imprisonment.

- ^ Wagner (1987) 199 Letter of 21 April 1850

- ^ Millington (1992) 297

- ^ Newman (1976) II, 137–138. Gutman records him as suffering from constipation and shingles (Gutman (1990) 142).

- ^ Millington (1992) 289, 294, 300

- ^ Wagner (1992) 508–510. Others agree on the profound importance of this work to Wagner – see Magee (2000) 133–134.

- ^ See e.g. Magee (2000) 276–278.

- ^ Magee (1988) 77–78

- ^ See e.g. Dahlhaus (1979).

- ^ Magee (2000) 251–253. Schopenhauer asserted that goodness and salvation result from renunciation of the world and turning against and denying one's own will.

- ^ Gutman (1990) 168–169

- ^ Millington (undated a)

- ^ a b Millington (1992) 318

- ^ Newman (1976) II, 540–542.

- ^ Newman (1976) II, 559–567

- ^ Deathridge (1984)

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 315–320

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 293–303

- ^ Wagner (1992) 667

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 321–330

- ^ Newman (1976) III, 147–148

- ^ Gutman (1990) 215–216

- ^ Gutman (1990) 262

- ^ Newman (1976) III, 212–220

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 339

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 346

- ^ Wagner (1992) 741

- ^ Wagner (1992) 739

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 354

- ^ Newman (1976) III, 366

- ^ Millington (1992) 32–33

- ^ Newman (1976) III, 530

- ^ Newman (1976) III, 499–501

- ^ Newman (1976) III, 538–539

- ^ Newman (1976) III, 518–519

- ^ Millington (1992) 301

- ^ Millington (1992) 17

- ^ Millington (1992) 311; Cosima's birthday was 24 December, but she usually celebrated it on Christmas Day

- ^ Millington (1992) 287, 290

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 400

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 411

- ^ Newman (1976) IV, 392–393

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 409–418

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 418–419

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 419

- ^ Gregor-Dellin (1983) 422

- ^ Millington (1992) 287

- ^ Statutes of the Foundation (in German) at Bayreuth Festival website.

- ^ Millington (1992) 18

- ^ Wagner (1994a) 211–273, 274–284

- ^ Millington (1992) 331–332

- ^ Millington (1992) 409

- ^ Millington (1992) 19

- ^ Gutman (1990) 414–417

- ^ Newman (1976) IV, 692

- ^ Newman (1976) IV, 697, 711–712

- ^ Walker (1996) 496–498

- ^ Newman (1976) IV, 714–716

- ^ Millington (1992) 264–268

- ^ Millington (1992) 234–235

- ^ Millington (1992) 236–237

- ^ In his 1872 essay 'On the Designation 'Music Drama', he criticizes the term "music drama" suggesting instead the phrase "deeds of music made visible" (Wagner (1995b) 299–304).

- ^ Millington (1992) 274–276

- ^ Magee (1988) 26

- ^ Westernhagen (1980) 111

- ^ Wagner (1994c) 391 and n.

- ^ For the reworking of Dutchman, see Deathridge (1982) 13, 25; for that of Tannhäuser, see Ashman (1988) 7–8.

- ^ Skelton (2002)

- ^ Westernhagen (1980) 106–107

- ^ See Millington (1992) 286; Donnington (1979) 128–130, 141, 210–212.

- ^ Millington (2008) 74

- ^ Grey (2008) 86

- ^ Millington (undated b)

- ^ Millington (1992) 294, 300, 304

- ^ Wagner (2004) Vol.2 Part III: 1850–1861 (no page numbers)

- ^ Letter of April 1859, quoted Daverio (208) 116

- ^ a b Rose (1981) 15

- ^ McClatchie (2008) 134

- ^ Millington (undated c)

- ^ See e.g. Weiner (1997) 66–72.

- ^ Millington (1992) 294–295

- ^ Millington (1992) 286

- ^ Millington (2008) 80

- ^ Shaw (1898) section: "Back to Opera Again"

- ^ Puffett (1984) 43

- ^ Puffett (1984) 48–49

- ^ Millington (1982) 285

- ^ Millington (1992) 308

- ^ Cosima Wagner, 28 March 1881

- ^ Stanley (2008) 169–175

- ^ Millington (undated d)

- ^ von Westernhagen (1980) 138

- ^ Millington (1992) 311–312

- ^ Overvold (1976) 179–180, 183

- ^ Millington (1992) 314

- ^ von Westernhagen (1980) 111

- ^ Deathridge (2008) 189–205

- ^ Kennedy (1980) 701, Wedding March

- ^ Millington (1992) 174–177

- ^ Wagner (1983)

- ^ Treadwell (2008), 191

- ^ Millington (1982) 190, 412

- ^ Deathridge (2008) 114

- ^ Magee (2000) 208–209

- ^ See articles on these composers in Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians; also Grey (2008) 222–229 and Deathridge (2008) 231–232.

- ^ Magee (1988) 54; Grey (2008) 228–229

- ^ Grey (2008) 226

- ^ Wagner (1995a) 289–364

- ^ Westrup (1980) 645. See for example Wagner's proposals for the rescoring of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony in his essay on that work (Wagner (1995b) 231–253).

- ^ von Westernhagen (1980) 113

- ^ Millington (1992) 396

- ^ a b Magee (1988) 52

- ^ Magee (1988) 49–50

- ^ Grey (2009) 372–387

- ^ Cited in Magee (1988) 48. Magee however does not cite Auden's further reference to Wagner as 'an absolute shit' (Ross (1998)).

- ^ Painter (1983) 163

- ^ Martin (1992) passim

- ^ Magee (1988) 47

- ^ Horton (1999)

- ^ Magee (2001) p 85

- ^ Picard T (ed) Dictionnaire Encyclopédique Wagner.Actes Sud, Paris 2010 p. 759.

- ^ Magee (1988) 47–56

- ^ Millington (1992) 26. See also New German School and War of the Romantics

- ^ Sietz & Wiegandt (undated)

- ^ Letter to Emile Naumann, April 1867, quoted in E. Naumann, Italienische Tondichter (1883) IV, 5.

- ^ Deathridge (2008) 228

- ^ cf. Shaw (1898)

- ^ Spotts (1994) 40

- ^ Spotts (1994) 11

- ^ Adorno (205), 34–36

- ^ Grant (1999)

- ^ Olivia Giovetti, 'Silver Screen Wagner Vies for Oscar Gold', WQXR Operavore blog, 10 December 2011, accessed 15 April 2012.

- ^ Michael Long, Beautiful monsters: imagining the classic in musical media, University of California Press, 2008. p.114.

- ^ See e.g. Katz (1986) and Rose (1996) passim. See also article Wagner controversies.

- ^ Wagner (1994)

- ^ Wagner (1995a) 149–170

- ^ Gutman, Robert (1990)

- ^ See, however, Weiner (1997) for very detailed allegations of anti-Semitism in Wagner's music and characterisations.

- ^ Millington, Barry (Ed.) (1992) 164 and Conway (2012) 198

- ^ Wagner (1992) 171

- ^ Conway (2002)

- ^ Nietzsche (1967) 182

- ^ Gutman, Robert (1990) 418 ff

- ^ Beckett (1981)

- ^ Gutman (1990) 406

- ^ Everett (2008)

- ^ Shaw (1998) Introduction

- ^ See Žižek (2009) viii: '[In this book] for the first time the Marxist reading of a musical work of art [...] was combined with the highest musicological analysis'.

- ^ Millington (2008) 81

- ^ Donington (1979); Millington (2008) 82–83

- ^ [1] Bahr, Ehrhard. "Art and Society in Mann's early novellas" in A companion to the works of Thomas Mann, ed. Prof. Herbert Lehnert, Prof. Eva Wessell: p. 55

- ^ The story that Hitler claimed that, after seeing a performance as a young man of Rienzi, "it all began", has been exposed as "fanciful". See Kershaw (1999) 610.

- ^ However, the story that the Nazis banned Parsifal because of its supposed pacifist qualities is completely without foundation. See Deathridge (2008) 173–174.

- ^ "According to Jonathan Carr, author of the forthcoming book The Wagner Clan, Hitler himself was obsessed by "the Master". But the party faithful were not and had to be dragged to performances at Hitler's insistence" (Higgins (2007)).

- ^ Fackler (2007). See also the Music and the Holocaust website.

- ^ For example, in Walsh (1992).

- ^ See e.g. John (2004) for a detailed essay on music in the Nazi death camps, which however nowhere mentions Wagner. See also Potter (2008) 244: "We know from testimonies that concentration camp orchestras played [all sorts of] music [...] but that Wagner was explicitly off-limits. However, after the war, unsubstantiated claims that Wagner's music accompanied Jews to their death took on momentum".

- ^ See Bruen (1993).

Sources and further reading

Prose works by Wagner

- Wagner, Richard, (ed. Dieter Borchmeyer) (1983) Richard Wagner Dichtungen und Schriften, 10 vols. Frankfurt am Main.

- Wagner, Richard (ed. and trans. Stewart Spencer and Barry Millington) (1987) Selected Letters of Richard Wagner, Dent. ISBN 0-460-04643-8; W. W. Norton and Company ISBN 978-0-393-02500-2.

- Wagner, Richard (trans. Andrew Gray) (1992) My Life, Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80481-6 Wagner's sometimes unreliable autobiography, covering his life to 1864, written between 1865 and 1880 and first published privately in German in a small edition between 1870 and 1880. The first (edited) public edition appeared in 1911. Gray's translation is the most comprehensive available.

- Wagner, Richard: Collected Prose Works. tr. W. Ashton Ellis

- Wagner, Richard (1994c) Vol. 1 The Artwork of the Future and Other Works, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9752-4

- Wagner, Richard (1995d) Vol. 2 Opera and Drama, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. 1995. ISBN 0-8032-9765-3

- Wagner, Richard (1995c) Vol. 3 Judaism in Music and Other Essays, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9766-1

- Wagner, Richard (1995a) Vol. 4 Art and Politics, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9774-6

- Wagner, Richard (1995b) Vol. 5 Actors and Singers, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9773-9

- Wagner, Richard (1994a) Vol. 6 Religion and Art , University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9764-7

- Wagner, Richard (1994b) Vol. 7 Pilgrimage to Beethoven and Other Essays, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9763-0

- Wagner, Richard (1995c) Vol. 8 Jesus of Nazareth and Other Writings, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9780-7

Other sources

- Adorno, Theodor (trans. Rodney Livingstone) (2009) In Search of Wagner Verso Books, London. ISBN 978-1-84467-344-5

- Ashman, Mike (1982) "Tannhäuser – an obsession" in: John, Nicholas (Series Editor) English National Opera/The Royal Opera House Opera Guide 12: Der Fliegende Holländer/The Flying Dutchman, London, John Calder, ISBN 0-7145-3920-1. pp. 7–15.

- Beckett, Lucy (1981) Richard Wagner: Parsifal, Cambridge University Press.

- Borchmeyer, Dieter (2003) "Drama and the World of Richard Wagner", Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11497-2

- Brown, Jonathan (2012). Great Wagner Conductors – a listener’s companion. O’Connor, A.C.T.: Parrot Press. Chapter 1 is devoted to Wagner; includes discography. ISBN 978-0-9871556-0-3

- Bruen, Hanan (1993) Wagner in Israel: A conflict among Aesthetic, Historical, Psychological and Social Considerations, Journal of Aesthetic Education, vol. 27 no. 1 (Spring 1993), pp. 99–103

- Burbidge, Peter and Sutton, Richard (eds.) (1979) "The Wagner Companion", Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29657-1

- Dahlhaus, Carl (trans. Mary Whittall) (1979) Richard Wagner's Music Dramas, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-22397-3

- Conway, David (2002) "'A Vulture is Almost an Eagle'......The Jewishness of Richard Wagner", Jewry in Music, accessed 23 July 2010.

- Conway, David (2011) Jewry in Music: Entry to the Profession from the Enlightenment to Richard Wagner, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01538-8

- Dallas, Ian (1990) The New Wagnerian, Freiburg Books. ISBN 978-84-404-7475-9

- Daverio, John (2008) Tristan und Isolde: essence and appearance, in Grey (2008) 115–133

- Deathridge, John (1984), The New Grove Wagner, London: Macmillan, ISBN 0-333-36065-6

- Deathridge, John (1982) "An Introduction to The Flying Dutchman" in John, Nicholas (Series Editor) English National Opera/The Royal Opera House Opera Guide 12: Der Fliegende Holländer/The Flying Dutchman, London, John Calder, ISBN 0-7145-3920-1 pp. 13–26.

- Deathridge, John (2008) Wagner Beyond Good and Evil, Berkeley ISBN 978-0-520-25453-4

- Donnington, Robert (1979) Wagner's 'Ring' and its Symbols Faber Paperbacks London ISBN 0-571-04818-8

- Everett, Derrick (2008) "Wagner, Gobineau and Parsifal: Gobineau as the inspiration for Parsifal", http://www.monsalvat.no, version of 26 June 2008, accessed 27 July 2010.

- Fackler, Guido (tr. Peter Logan) (2007) "Music in Concentration Camps 1933–1945", Music and Politics, Volume I, Number 1, (Winter 2007).

- Grant, John (1999) "Excalibur: US movie" in John Clute & John Grant (Eds.) The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, Orbit p. 324. ISBN 1-85723-893-1

- Gregor-Dellin, Martin (1983) Richard Wagner – His Life, His Work, His Century, Harcourt. ISBN 978-0-15-177151-6

- Grey, Thomas S. (ed.) (2008) The Cambridge Companion to Wagner, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64439-6

- Gutman, Robert W. (1990) Wagner – The Man, His Mind and His Music, Harvest Books. ISBN 978-0-15-677615-8

- Higgins, Charlotte (2007) How the Nazis took flight from Valkyries and Rhinemaidens, The Guardian, 3 July 2007, accessed 28 December 2008.

- Horton, Paul C. (1999) Review of Psychoanalytic Explorations in Music: Second Series ed. Stuart Feder, American Journal of Psychiatry vol. 156 pp. 1109–1110, July 1999, consulted 8 July 2010

- John, Eckhardt (2004) La musique dans la système concentrationnaire nazi, in Le troisième Reich et al. Musique, ed. Pascal Huynh, Paris ISBN 2-213-62135-7

- Katz, Jacob (1986) The Darker Side of Genius: Richard Wagner's Anti-Semitism, Hanover and London. ISBN 0-87451-368-5

- Kennedy, Michael (1980) The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Music, Oxford ISBN 978-0-19-311320-6

- Kershaw, Ian (1999) Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris, Penguin. ISBN 0-14-028898-8

- Laibach (undated) "Laibach presents VolksWagner", www.laibach.nsk.si. (Accessed 23 July 2010)

- Lee, M. Owen (1998) Wagner: The Terrible Man and His Truthful Art, University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-4721-2

- Magee, Bryan (2001) The Tristan Chord: Wagner and Philosophy, Metropolitan Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-7189-4

- Magee, Bryan (1988) Aspects of Wagner, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284012-7

- Magic Circle Music (undated) "Artist biography: Manowar", maciccirclemusic.com, accessed 23 July 2010.

- May, Thomas (2004) Decoding Wagner, Amadeus Press. ISBN 978-1-57467-097-4

- Martin, T. P. (1992) Joyce and Wagner: A Study in Influence, Cambridge , 1992. ISBN 978-0-521-39487-1

- McClatchie, Stephen (2008) Performing Germany in Wagner's 'Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg' ,in Grwy (2008) pp. 134–150

- Millington, Barry (Ed.) (1992) The Wagner Compendium: A Guide to Wagner's Life and Music. Thames and Hudson Ltd., London. ISBN 0-02-871359-1

- Millington, Barry (2008) Der Ring des Nibelungen: conception and interpretation in Grey (2008), 74–84

- Millington, Barry (undated a) "Wesendonck, Mathilde" in Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. (Subscription only, accessed 20 July 2010).

- Millington, Barry (undated b) "Walküre, Die." In The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/O003661 (Subscription only, accessed 23 July 2010).

- Millington, Barry (undated c) "Meistersinger von Nürnberg, Die." In The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/O003512 (Subscription only, accessed 23 July 2010).

- Millington, Barry (undated d) "Parsifal." In The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, edited by Stanley Sadie. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/O002803 (Subscription only, accessed 23 July 2010).

- Newman, Ernest (1933) The Life of Richard Wagner, 4 vols. ISBN 978-0-685-14824-2 (the classic biography, superseded by newer research but still full of many valuable insights)

- Nicholson, Christopher (2007) "Richard and Adolf: Did Richard Wagner incite Adolf Hitler to commit the Holocaust?", Gefen Publishing House. ISBN 978-965-229-360-2

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (trans. Walter Kaufmann) (1967) The Case of Wagner in Nietsche (trans. Kaufmann) The Birth of Tragedy and The Case of Wagner, Random House. ISBN 394 70369-3.

- Overvold, Liselotte Z. (1976) Wagner's American Centennial March: Genesis and Reception, Monatshefte (Univ.of Wisconsin),Vol.68 no.2 (Summer 1976), pp. 179–187

- Painter, George D. (1983) Marcel Proust. Penguin, Harmondsworth ISBN 0-14-006512-1

- Potter, Pamela R. (2008) Wagner and the Third Reich: myths and realities, in The Cambridge Companion to Wagner, ed. Thomas S. Grey, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-64439-6

- Puffett, Derrick (1984) "Siegfried in the Context of Wagner's Operatic Writing", in Siegfried: Opera Guide 28 series ed. Nicholas John, John Calder (Publishers) Ltd. ISBN 0-7145-4040-4

- Rose, John Luke (1981) "A Landmark in Musical History" in Nicholas John (series ed.) Tristan and Isolde: English National Opera Guide 6, John Calder Publisher's Ltd. ISBN 0-7145-3849-3

- Rose, Paul Lawrence (1996) Wagner:Race and Revolution, London ISBN 0-571-17888-X

- Ross, Alex (1998) The Unforgiven: Wagner and Hitler" in The New Yorker, 10 August 1998. Copy on author's website used. Link accessed 10 July 2010.

- Runciman, J.F. (1913) Wagner, Project Gutenberg edition. here [2].

- Salmi, Hannu (2005) Wagner and Wagnerism in Nineteenth-Century Sweden, Finland, and the Baltic Provinces: Reception, Enthusiasm, Cult, Eastman Studies in Music. University of Rochester Press. ISBN 978-1-58046-207-5

- Salmi, Hannu (2000) Imagined Germany. Richard Wagner's National Utopia, Peter Lang Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8204-4416-1

- Scruton, Roger (2003) Death-Devoted Heart: Sex and the Sacred in Wagner's 'Tristan and Isolde', Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516691-0

- Shaw, George Bernard (1898) The Perfect Wagnerite. Online version at http://www.gutenberg.org/files/1487/1487-h/1487-h.htm#2H_4_0011 accessed 20 July 2010.

- Sietz, Reinhold and Wiegandt, Matthias (undated) "Hiller, Ferdinand." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/13041 (Subscription only, accessed 23 July 2010).

- Skelton, Geoffrey (2002) "Bayreuth" in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online. Version dated 28 February 2002, accessed 20 December 2009.

- Spencer, Stewart (2000) Wagner Remembered, Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-19653-1

- Spiro, Jonathan Peter (2008) Defending the master race: conservation, eugenics, and the legacy of Madison Grant, UPNE. ISBN 978-1-58465-715-5 .

- Spotts, Frederic (1994) Bayreuth: A History of the Wagner Festival, New Haven and London ISBN 978-0-300-06665-4

- Tanner, M. (1995) Wagner, Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-10290-0

- Treadwell, James (2008) The Urge to Communicatein Grey (2008), pp. 179–191

- von Westernhagen, Kurt (1980) (Wilhelm) Richard Wagner in vol. 20 of Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. S. Sadie, London 1980

- Wagner, Cosima (trans. Geoffrey Skelton) (1978) Diaries, 2 vols. ISBN 978-0-15-122635-1

- Walker, Alan (1996) Franz Liszt: The Final Years, New York. ISBN 978-0-394-52542-6

- Walsh, Michael (1992) The Case of Wagner – Again, Time, 13 January 1992, consulted online 17 July 2010

- Wapnewski, Peter (1992) Wagner's Musical Influence, in The Wagner Handbook

- Weiner, Marc A. (1997) Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination, Lincoln and London. ISBN 978-0-8032-9792-0

- Westrup, Jack (1980) Conducting, in vol. 4 of Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. S. Sadie, London 1980

- Žižek, Slavoj (2009) "Foreword: Why is Wagner Worth Saving" in Adorno (2009) viii–xxvii.

External links

- Operas

- Richard Wagner Opera, Richard Wagner operas, Wagner interviews, CDs, DVDs, Wagner calendar, Bayreuth Festival

- Wagner Operas, site featuring photographs, video, MIDI files, scores, libretti, and commentary

- RWagner.net, contains libretti of his operas, with English translations

- Wagner website, assortment of articles on Wagner and his operas

- Photo of Wagner's manuscript for the Bridal Chorus

- The Wagnerian Romances by Gertrude Hall

- Wilhelm Richard Wagner site by Stanford University

- Writings

- The Wagner Library. English translations of Wagner's prose works, including some of Wagner's more notable essays.

- Works by Richard Wagner at Project Gutenberg

- Template:Worldcat id

- Pictures

- The Richard Wagner Postcard-Gallery, a gallery of historic postcards with motives from Richard Wagner's operas.

- gallica.bnf.fr Pictures of Richard Wagner and his family.

- Scores

- Free scores by Richard Wagner in the Choral Public Domain Library (ChoralWiki)

- Free scores by Wagner at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Template:IckingArchive

- Other

- BBC audio file. Discussion of Wagner on Radio 4 programme In our time.

- Bayreuth Festival

- The National Archive of the Richard Wagner Foundation

- The humanities.music.composers.wagner FAQ.

- Richard Wagner Museum in the country manor Triebschen beside Lucerne, Switzerland where he and Cosima lived and worked from 1866 to 1872.

- The Wagner Tuba

Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA Template:Link FA

- Ill-formatted IPAc-en transclusions

- Use dmy dates from August 2010

- Richard Wagner

- 1813 births

- 1883 deaths

- 19th-century German people

- Deaths from myocardial infarction

- German composers

- German conductors (music)

- German Lutherans

- German music critics

- German theatre directors

- German writers

- German essayists

- German autobiographers

- Honorary Members of the Royal Philharmonic Society

- Antisemitism

- Music in Leipzig

- Opera composers

- German opera librettists

- Opera managers

- People from Leipzig

- People of the Revolutions of 1848

- Romantic composers

- Romanticism

- University of Leipzig alumni

- Wagner family

- Walhalla enshrinees

- 19th-century theatre

- Members of the Bavarian Maximilian Order for Science and Art

- 19th-century conductors (music)

- 19th-century composers