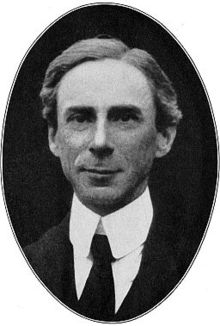

Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 18 May 1872 Trellech, Monmouthshire, UK |

| Died | 2 February 1970 (aged 97) Penrhyndeudraeth, Wales, UK |

| Nationality | British |

| Era | 20th century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Analytic philosophy Nobel Prize in Literature 1950 |

Main interests | |

Notable ideas | Analytic philosophy · Logical atomism · theory of descriptions · knowledge by acquaintance and knowledge by description · Russell's paradox · Russell's teapot |

| Signature | |

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, OM, FRS[1] (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, historian, and social critic.[2] At various points in his life he considered himself a liberal, a socialist, and a pacifist, but he also admitted that he had never been any of these in any profound sense.[3] He was born in Monmouthshire, into one of the most prominent aristocratic families in Britain.[4]

Russell led the British "revolt against idealism" in the early 20th century. He is considered one of the founders of analytic philosophy along with his predecessor Gottlob Frege and his protégé Ludwig Wittgenstein. He is widely held to be one of the 20th century's premier logicians.[2] He co-authored, with A. N. Whitehead, Principia Mathematica, an attempt to ground mathematics on logic. His philosophical essay "On Denoting" has been considered a "paradigm of philosophy."[5] His work has had a considerable influence on logic, mathematics, set theory, linguistics, computer science (see type theory and type system), and philosophy, especially philosophy of language, epistemology, and metaphysics.

Russell was a prominent anti-war activist; he championed anti-imperialism[6][7] and went to prison for his pacifism during World War I.[8] Later, he campaigned against Adolf Hitler, then criticised Stalinist totalitarianism, attacked the United States of America's involvement in the Vietnam War, and was an outspoken proponent of nuclear disarmament.[9] In 1950 Russell was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, "in recognition of his varied and significant writings in which he champions humanitarian ideals and freedom of thought."[10]

Biography

Ancestry

Bertrand Russell was born on 18 May 1872 at Ravenscroft, Trellech, Monmouthshire, Wales, into an influential and liberal family of the British aristocracy.[11] His paternal grandfather, John Russell, 1st Earl Russell, was the third son of John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, and had twice been asked by Queen Victoria to form a government, serving her as Prime Minister in the 1840s and 1860s.[12]

The Russells had been prominent in England for several centuries before this, coming to power and the peerage with the rise of the Tudor dynasty. They established themselves as one of Britain's leading Whig families, and participated in every great political event from the Dissolution of the Monasteries in 1536–40 to the Glorious Revolution in 1688–89 and the Great Reform Act in 1832.[12][13]

Russell's mother, Katharine Louisa (1844–1874), was the daughter of Edward Stanley, 2nd Baron Stanley of Alderley, and the sister of Rosalind Howard, Countess of Carlisle.[9] Kate and Rosalind's mother was one of the founders of Girton College, Cambridge.[14]

Russell's parents were radical for their times. Russell's father, Viscount Amberley, was an atheist and consented to his wife's affair with their children's tutor, the biologist Douglas Spalding. Both were early advocates of birth control at a time when this was considered scandalous.[15] John Russell's atheism was evident when he asked the philosopher John Stuart Mill to act as Russell's secular godfather.[16] Mill died the year after Russell's birth, but his writings had a great effect on Russell's life.

Childhood and adolescence

Russell had two siblings: Frank (nearly seven years older than Bertrand), and Rachel (four years older). In June 1874 Russell's mother died of diphtheria, followed shortly by Rachel's death. In January 1876, his father died of bronchitis following a long period of depression. Frank and Bertrand were placed in the care of their staunchly Victorian paternal grandparents, who lived at Pembroke Lodge in Richmond Park. His grandfather, former Prime Minister John Russell, died in 1878, and was remembered by Russell as a kindly old man in a wheelchair. His grandmother, the Countess Russell (née Lady Frances Elliot), was the dominant family figure for the rest of Russell's childhood and youth.[9][15]

The countess was from a Scottish Presbyterian family, and successfully petitioned the Court of Chancery to set aside a provision in Amberley's will requiring the children to be raised as agnostics. Despite her religious conservatism, she held progressive views in other areas (accepting Darwinism and supporting Irish Home Rule), and her influence on Bertrand Russell's outlook on social justice and standing up for principle remained with him throughout his life—her favourite Bible verse, 'Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil' (Exodus 23:2), became his motto. The atmosphere at Pembroke Lodge was one of frequent prayer, emotional repression, and formality; Frank reacted to this with open rebellion, but the young Bertrand learned to hide his feelings.

Russell's adolescence was very lonely, and he often contemplated suicide. He remarked in his autobiography that his keenest interests were in religion and mathematics, and that only the wish to know more mathematics kept him from suicide.[17] He was educated at home by a series of tutors.[10] His brother Frank introduced him to the work of Euclid, which transformed Russell's life.[15][18]

During these formative years he also discovered the works of Percy Bysshe Shelley. In his autobiography, he writes: "I spent all my spare time reading him, and learning him by heart, knowing no one to whom I could speak of what I thought or felt, I used to reflect how wonderful it would have been to know Shelley, and to wonder whether I should meet any live human being with whom I should feel so much sympathy."[19] Russell claimed that beginning at age 15, he spent considerable time thinking about the validity of Christian religious dogma, and by 18 had decided to discard the last of it.[20]

University and first marriage

Russell won a scholarship to read for the Mathematical Tripos at Trinity College, Cambridge, and commenced his studies there in 1890.[21] He became acquainted with the younger George Edward Moore and came under the influence of Alfred North Whitehead, who recommended him to the Cambridge Apostles. He quickly distinguished himself in mathematics and philosophy, graduating as a high Wrangler in 1893 and becoming a Fellow in the latter in 1895.[22][23]

Russell first met the American Quaker Alys Pearsall Smith when he was 17 years old. He became a friend of the Pearsall Smith family—they knew him primarily as 'Lord John's grandson' and enjoyed showing him off—and travelled with them to the continent; it was in their company that Russell visited the Paris Exhibition of 1889 and was able to climb the Eiffel Tower soon after it was completed.[24]

He soon fell in love with the puritanical, high-minded Alys, who was a graduate of Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, and, contrary to his grandmother's wishes, married her on 13 December 1894. Their marriage began to fall apart in 1901 when it occurred to Russell, while he was cycling, that he no longer loved her. She asked him if he loved her and he replied that he didn't. Russell also disliked Alys's mother, finding her controlling and cruel. It was to be a hollow shell of a marriage and they finally divorced in 1921, after a lengthy period of separation.[25] During this period, Russell had passionate (and often simultaneous) affairs with a number of women, including Lady Ottoline Morrell[26] and the actress Lady Constance Malleson.[27]

Early career

Russell began his published work in 1896 with German Social Democracy, a study in politics that was an early indication of a lifelong interest in political and social theory. In 1896 he taught German social democracy at the London School of Economics, where he also lectured on the science of power in the autumn of 1937.[28] He was a member of the Coefficients dining club of social reformers set up in 1902 by the Fabian campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb.[29]

He now started an intensive study of the foundations of mathematics at Trinity, during which he discovered Russell's paradox, which challenged the foundations of set theory. In 1903 he published his first important book on mathematical logic, The Principles of Mathematics, arguing that mathematics could be deduced from a very small number of principles, a work which contributed significantly to the cause of logicism.[30]

In 1905 he wrote the essay "On Denoting", which was published in the philosophical journal Mind. Russell became a fellow of the Royal Society in 1908.[1][9] The first of three volumes of Principia Mathematica, written with Whitehead, was published in 1910, which, along with the earlier The Principles of Mathematics, soon made Russell world famous in his field.

In 1910 he became a lecturer in the University of Cambridge, where he was approached by the Austrian engineering student Ludwig Wittgenstein, who became his PhD student. Russell viewed Wittgenstein as a genius and a successor who would continue his work on logic. He spent hours dealing with Wittgenstein's various phobias and his frequent bouts of despair. This was often a drain on Russell's energy, but Russell continued to be fascinated by him and encouraged his academic development, including the publication of Wittgenstein's Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus in 1922.[31] Russell delivered his lectures on Logical Atomism, his version of these ideas, in 1918, before the end of the First World War. Wittgenstein was still a prisoner of war.

First World War

During the First World War, Russell was one of the very few people to engage in active pacifist activities,[32] and in 1916, he was dismissed from Trinity College following his conviction under the Defence of the Realm Act.

He was charged a fine of £100, which he refused to pay, hoping that he would be sent to prison. However, his books were sold at auction to raise the money. The books were bought by friends; he later treasured his copy of the King James Bible that was stamped "Confiscated by Cambridge Police."

A later conviction for publicly lecturing against inviting the US to enter the war on Britain's side resulted in six months' imprisonment in Brixton prison (see Bertrand Russell's views on society) in 1918.[33] He was reinstated in 1919, resigned in 1920, was Tarner Lecturer 1926, and became a Fellow again 1944–1949.[34]

Between the wars and second marriage

In August 1920 Russell travelled to Russia as part of an official delegation sent by the British government to investigate the effects of the Russian Revolution.[35] He met Vladimir Lenin and had an hour-long conversation with him. In his autobiography, he mentions that he found Lenin rather disappointing, sensing an "impish cruelty" in him and comparing him to "an opinionated professor". He cruised down the Volga on a steamship. Russell's lover Dora Black, a British author, feminist and socialist campaigner, visited Russia independently at the same time—she was enthusiastic about the revolution, but Russell's experiences destroyed his previous tentative support for it. He wrote a book The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism[36] about his experiences on this trip, taken with a group of 24 others from Britain, all of whom came home thinking well of the regime, despite Russell's attempts to change their minds. For example, he told them that he heard shots fired in the middle of the night and was sure these were clandestine executions, but the others maintained that it was only cars backfiring.

Russell subsequently lectured in Beijing on philosophy for one year, accompanied by Dora. He went there with optimism and hope, as China was then on a new path. Other scholars present in China at the time included Rabindranath Tagore, the Nobel laureate Indian poet.[10] While in China, Russell became gravely ill with pneumonia, and incorrect reports of his death were published in the Japanese press.[37] When the couple visited Japan on their return journey, Dora notified the world that "Mr. Bertrand Russell, having died according to the Japanese press, is unable to give interviews to Japanese journalists." The press, not appreciating the sarcasm, were not amused.[38]

Dora was six months pregnant when the couple returned to England on 26 August 1921. Russell arranged a hasty divorce from Alys, marrying Dora six days after the divorce was finalised, on 27 September 1921. Their children were John Conrad Russell, 4th Earl Russell, born on 16 November 1921, and Katharine Jane Russell (now Lady Katharine Tait), born on 29 December 1923. Russell supported himself during this time by writing popular books explaining matters of physics, ethics, and education to the layman. Some have suggested that at this point he had an affair with Vivienne Haigh-Wood, the English governess and writer, and first wife of T. S. Eliot.[39]

Together with Dora, he founded the experimental Beacon Hill School in 1927. The school was run from a succession of different locations, including its original premises at the Russells' residence, Telegraph House, near Harting, West Sussex. On 8 July 1930 Dora gave birth to her third child, a daughter, Harriet Ruth. After he left the school in 1932, Dora continued it until 1943.[40][41]

Upon the death of his elder brother Frank, in 1931, Russell became the 3rd Earl Russell. He once said that his title was primarily useful for securing hotel rooms.

Russell's marriage to Dora grew increasingly tenuous, and it reached a breaking point over her having two children with an American journalist, Griffin Barry.[41] They separated in 1932 and finally divorced. On 18 January 1936, Russell married his third wife, an Oxford undergraduate named Patricia ("Peter") Spence, who had been his children's governess since 1930. Russell and Peter had one son, Conrad Sebastian Robert Russell, 5th Earl Russell, who became a prominent historian and one of the leading figures in the Liberal Democratic party.[9]

During the 1930s, Russell became a close friend and collaborator of V. K. Krishna Menon, then secretary of the India League, the foremost lobby for Indian independence in Great Britain.

Second World War

Russell opposed rearmament against Nazi Germany, but in 1940 changed his view that avoiding a full scale world war was more important than defeating Hitler. He concluded that Adolf Hitler taking over all of Europe would be a permanent threat to democracy. In 1943, he adopted a stance toward large-scale warfare, "Relative Political Pacifism": war was always a great evil, but in some particularly extreme circumstances, it may be the lesser of two evils.[42]

Before the Second World War, Russell taught at the University of Chicago, later moving on to Los Angeles to lecture at the UCLA Department of Philosophy. He was appointed professor at the City College of New York in 1940, but after a public outcry, the appointment was annulled by a court judgement: his opinions (especially those relating to sexual morality, detailed in Marriage and Morals ten years earlier) made him "morally unfit" to teach at the college. The protest was started by the mother of a student who would not have been eligible for his graduate-level course in mathematical logic. Many intellectuals, led by John Dewey, protested against his treatment.[43] Albert Einstein's often-quoted aphorism that "Great spirits have always encountered violent opposition from mediocre minds ... " originated in his open letter in support of Russell, during this time.[44] Dewey and Horace M. Kallen edited a collection of articles on the CCNY affair in The Bertrand Russell Case. He soon joined the Barnes Foundation, lecturing to a varied audience on the history of philosophy; these lectures formed the basis of A History of Western Philosophy. His relationship with the eccentric Albert C. Barnes soon soured, and he returned to Britain in 1944 to rejoin the faculty of Trinity College.[45]

Later life

During the 1940s and 1950s, Russell participated in many broadcasts over the BBC, particularly The Brains Trust and the Third Programme, on various topical and philosophical subjects. By this time Russell was world famous outside of academic circles, frequently the subject or author of magazine and newspaper articles, and was called upon to offer opinions on a wide variety of subjects, even mundane ones. En route to one of his lectures in Trondheim, Russell was one of 24 survivors (among a total of 43 passengers) in an aeroplane crash in Hommelvik in October 1948. He said he owed his life to smoking since the people who drowned were in the non-smoking part of the plane.[46] A History of Western Philosophy (1945) became a best-seller, and provided Russell with a steady income for the remainder of his life.

In a speech in 1948,[47] Russell said that if the USSR's aggression continued, it would be morally worse to go to war after the USSR possessed an atomic bomb than before it possessed one, because if the USSR had no bomb the West's victory would come more swiftly and with fewer casualties than if there were atom bombs on both sides. At that time, only the United States possessed an atomic bomb, and the USSR was pursuing an extremely aggressive policy towards the countries in Eastern Europe which it was absorbing into its sphere of influence. Many understood Russell's comments to mean that Russell approved of a first strike in a war with the USSR, including Nigel Lawson, who was present when Russell spoke. Others, including Griffin, who obtained a transcript of the speech, have argued that he was merely explaining the usefulness of America's atomic arsenal in deterring the USSR from continuing its domination of Eastern Europe.[46]

In 1948, Russell was invited by the BBC to deliver the inaugural Reith Lectures[48]—what was to become an annual series of lectures, still broadcast by the BBC. His series of six broadcasts, titled Authority and the Individual,[49] explored themes such as the role of individual initiative in the development of a community and the role of state control in a progressive society. Russell continued to write about philosophy. He wrote a foreword to Words and Things by Ernest Gellner, which was highly critical of the later thought of Ludwig Wittgenstein and of Ordinary language philosophy. Gilbert Ryle refused to have the book reviewed in the philosophical journal Mind, which caused Russell to respond via The Times. The result was a month-long correspondence in The Times between the supporters and detractors of ordinary language philosophy, which was only ended when the paper published an editorial critical of both sides but agreeing with the opponents of ordinary language philosophy.[50]

In the King's Birthday Honours of 9 June 1949, Russell was awarded the Order of Merit,[51] and the following year he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.[9][10] When he was given the Order of Merit, King George VI was affable but slightly embarrassed at decorating a former jailbird, saying that "You have sometimes behaved in a manner that would not do if generally adopted."[52] Russell merely smiled, but afterwards claimed that the reply "That's right, just like your brother" immediately came to mind.

In 1952 Russell was divorced by Spence, with whom he had been very unhappy. Conrad, Russell's son by Spence, did not see his father between the time of the divorce and 1968 (at which time his decision to meet his father caused a permanent breach with his mother).

Russell married his fourth wife, Edith Finch, soon after the divorce, on 15 December 1952. They had known each other since 1925, and Edith had taught English at Bryn Mawr College near Philadelphia, sharing a house for 20 years with Russell's old friend Lucy Donnelly. Edith remained with him until his death, and, by all accounts, their marriage was a happy, close, and loving one. Russell's eldest son, John, suffered from serious mental illness, which was the source of ongoing disputes between Russell and John's mother, Russell's former wife, Dora. John's wife Susan was also mentally ill, and eventually Russell and Edith became the legal guardians of their three daughters [citation needed](two of whom were later found to have schizophrenia).

In 1962 Russell played a public role in the Cuban Missile Crisis: in an exchange of telegrams with Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, Khrushchev assured him that the Soviet government would not be reckless.[53] Russell also wrote to John F. Kennedy, who returned his telegram unopened.[citation needed]

According to historian Peter Knight, after the John F. Kennedy assassination, Russell, "prompted by the emerging work of the lawyer Mark Lane in the US ... rallied support from other noteworthy and left-leaning compatriots to form a Who Killed Kennedy Committee in June 1964, members of which included Michael Foot MP, the wife of Tony Benn MP, the publisher Victor Gollancz, the writers John Arden and J. B. Priestley, and the Oxford history professor Hugh Trevor-Roper. Russell published a highly critical article weeks before the Warren Commission Report was published, setting forth 16 Questions on the Assassination and equating the Oswald case with the Dreyfus affair of late 19th century France, in which the state wrongly convicted an innocent man. Russell also criticized the American press for failing to heed any voices critical of the official version.[54]

Political causes

Russell spent the 1950s and 1960s engaged in various political causes, primarily related to nuclear disarmament and opposing the Vietnam War (see also Russell Vietnam War Crimes Tribunal). The 1955 Russell–Einstein Manifesto was a document calling for nuclear disarmament and was signed by 11 of the most prominent nuclear physicists and intellectuals of the time.[55] He wrote a great many letters to world leaders during this period. He was in contact with Lionel Rogosin while the latter was filming his anti-war film Good Times, Wonderful Times in the 1960s. He became a hero to many of the youthful members of the New Left. In early 1963, in particular, Russell became increasingly vocal about his disapproval of what he felt to be the US government's near-genocidal policies in South Vietnam. In 1963 he became the inaugural recipient of the Jerusalem Prize, an award for writers concerned with the freedom of the individual in society.[56] In October 1965 he tore up his Labour Party card because he suspected the party was going to send soldiers to support the US in the Vietnam War.[9]

Final years and death

Russell published his three-volume autobiography in 1967, 1968, and 1969. On 23 November 1969 he wrote to The Times newspaper saying that the preparation for show trials in Czechoslovakia was "highly alarming". The same month, he appealed to Secretary General U Thant of the United Nations to support an international war crimes commission to investigate alleged torture and genocide by the United States in South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. The following month, he protested to Alexei Kosygin over the expulsion of Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn from the Writers Union.

Russell made a cameo appearance playing himself in the anti-war Hindi film "Aman" which was released in India in 1967. This was Russell's only appearance in a feature film.[57]

On 31 January 1970 Russell issued a statement which condemned Israel's "aggression" in the Middle East, and in particular, Israeli bombing raids being carried out deep in Egyptian territory as part of the War of Attrition, and called for an Israeli withdrawal to the pre-1967 borders. This was Russell's final political statement or act. It was read out at the International Conference of Parliamentarians in Cairo on 3 February 1970, the day after his death.[58]

Russell died of influenza on 2 February 1970 at his home, Plas Penrhyn, in Penrhyndeudraeth, Merionethshire, Wales. His body was cremated in Colwyn Bay on 5 February 1970. In accordance with his will, there was no religious ceremony; his ashes were scattered over the Welsh mountains later that year.

In 1980 a memorial to Russell was commissioned by a committee including the philosopher A. J. Ayer. It consists of a bust of Russell in Red Lion Square in London sculpted by Marcelle Quinton.[59]

Titles and honours from birth

Russell held throughout his life the following styles and honours:

- from birth until 1908: The Honourable Bertrand Arthur William Russell

- from 1908 until 1931: The Honourable Bertrand Arthur William Russell, FRS

- from 1931 until 1949: The Right Honourable The Earl Russell, FRS

- from 1949 until death: The Right Honourable The Earl Russell, OM, FRS

Views

Views on philosophy

Russell is generally credited with being one of the founders of analytic philosophy. He was deeply impressed by Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716), and wrote on every major area of philosophy except aesthetics. He was particularly prolific in the field of metaphysics, the logic and the philosophy of mathematics, the philosophy of language, ethics and epistemology. When Brand Blanshard asked Russell why he didn't write on aesthetics, Russell replied that he didn't know anything about it, "but that is not a very good excuse, for my friends tell me it has not deterred me from writing on other subjects."[60]

Views on religion

Russell described himself both as an agnostic[61] and an atheist. For most of his adult life Russell maintained that religion is little more than superstition and, despite any positive effects that religion might have, it is largely harmful to people. He believed religion and the religious outlook (he considered communism and other systematic ideologies to be forms of religion) serve to impede knowledge, foster fear and dependency, and are responsible for much of the war, oppression, and misery that have beset the world. He was a member of the Advisory Council of the British Humanist Association and President of Cardiff Humanists until his death.[62]

Views on society

Political and social activism occupied much of Russell's time for most of his life. Russell remained politically active almost to the end of his life, writing to and exhorting world leaders and lending his name to various causes. He was noted for saying "No one can sit at the bedside of a dying child and still believe in God."[63]

Russell believed that a scientific society controlled by a scientific elite would be most successful. He advocated eugenics as a method to make better warriors and as a method of social control. He considered that the 'plebs' would be educated to believe that black is white, while a scientific technocratic elite would comprise a small minority. In his book: "The Impact of Science on Society", he states: "Scientific societies are as yet in their infancy. . . . It is to be expected that advances in physiology and psychology will give governments much more control over individual mentality than they now have even in totalitarian countries. Fitche laid it down that education should aim at destroying free will, so that, after pupils have left school, they shall be incapable, throughout the rest of their lives, of thinking or acting otherwise than as their schoolmasters would have wished. . . . Diet, injections, and injunctions will combine, from a very early age, to produce the sort of character and the sort of beliefs that the authorities consider desirable, and any serious criticism of the powers that be will become psychologically impossible. . . .”

He goes on to state: "Education should aim at destroying free will so that after pupils are thus schooled they will be incapable throughout the rest of their lives of thinking or acting otherwise than as their school masters would have wished ... The social psychologist of the future will have a number of classes of school children on whom they will try different methods of producing an unshakable conviction that snow is black. When the technique has been perfected, every government that has been in charge of education for more than one generation will be able to control its subjects securely without the need of armies or policemen."

Russel advocated radical methods of population control. In his book "The Impact of Science on Society", he states: "There are three ways of securing a society that shall be stable as regards population. The first is that of birth control, the second that of infanticide or really destructive wars, and the third that of general misery except for a powerful minority."

Russell determined man to be "the product of causes ... his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms, that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labors of the ages, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, that the whole temple of man's achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins—all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand ... "[64]

Selected bibliography

A selected bibliography of Russell's books in English, sorted by year of first publication:

- 1896. German Social Democracy. London: Longmans, Green.

- 1897. An Essay on the Foundations of Geometry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 1900. A Critical Exposition of the Philosophy of Leibniz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 1903. The Principles of Mathematics, Cambridge University Press.

- 1905. On Denoting, Mind, vol. 14. ISSN: 00264425. Basil Blackwell.

- 1910. Philosophical Essays. London: Longmans, Green.

- 1910–1913. Principia Mathematica (with Alfred North Whitehead). 3 vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- 1912. The Problems of Philosophy. London: Williams and Norgate.

- 1914. Our Knowledge of the External World as a Field for Scientific Method in Philosophy. Chicago and London: Open Court Publishing.

- 1916. [3]Principles of Social Reconstruction. London, George Allen and Unwin.

- 1916. Why Men Fight. New York: The Century Co.

- 1916. Justice in War-time. Chicago: Open Court.

- 1917. Political Ideals. New York: The Century Co.

- 1918. Mysticism and Logic and Other Essays. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1918. Proposed Roads to Freedom: Socialism, Anarchism, and Syndicalism. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1919. Introduction to Mathematical Philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin. (ISBN 0-415-09604-9 for Routledge paperback) (Copy at Archive.org).

- 1920. The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1921. The Analysis of Mind. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1922. The Problem of China. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1923. The Prospects of Industrial Civilization, in collaboration with Dora Russell. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1923. The ABC of Atoms, London: Kegan Paul. Trench, Trubner.

- 1924. Icarus; or, The Future of Science. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner.

- 1925. The ABC of Relativity. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner.

- 1925. What I Believe. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner.

- 1926. On Education, Especially in Early Childhood. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1927. The Analysis of Matter. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner.

- 1927. An Outline of Philosophy. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1927. Why I Am Not a Christian. London: Watts.

- 1927. Selected Papers of Bertrand Russell. New York: Modern Library.

- 1928. Sceptical Essays. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1929. Marriage and Morals. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1930. The Conquest of Happiness. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1931. The Scientific Outlook. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1932. Education and the Social Order, London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1934. Freedom and Organization, 1814–1914. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1935. In Praise of Idleness. London: George Allen & Unwin. (on refusal of work)

- 1935. Religion and Science. London: Thornton Butterworth.

- 1936. Which Way to Peace?. London: Jonathan Cape.

- 1937. The Amberley Papers: The Letters and Diaries of Lord and Lady Amberley, with Patricia Russell, 2 vols., London: Leonard & Virginia Woolf at the Hogarth Press.

- 1938. Power: A New Social Analysis. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1940. An Inquiry into Meaning and Truth. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

- 1945. A History of Western Philosophy and Its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- 1948. Human Knowledge: Its Scope and Limits. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1949. Authority and the Individual. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1950. Unpopular Essays. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1951. New Hopes for a Changing World. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1952. The Impact of Science on Society. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1953. Satan in the Suburbs and Other Stories. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1954. Human Society in Ethics and Politics. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1954. Nightmares of Eminent Persons and Other Stories. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1956. Portraits from Memory and Other Essays. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1956. Logic and Knowledge: Essays 1901–1950, edited by Robert C. Marsh. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1957. Why I Am Not A Christian and Other Essays on Religion and Related Subjects, edited by Paul Edwards. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1958. Understanding History and Other Essays. New York: Philosophical Library.

- 1959. Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1959. My Philosophical Development. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1959. Wisdom of the West, edited by Paul Foulkes. London: Macdonald.

- 1960. Bertrand Russell Speaks His Mind, Cleveland and New York: World Publishing Company.

- 1961. The Basic Writings of Bertrand Russell, edited by R.E. Egner and L.E. Denonn. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1961. Fact and Fiction. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1961. Has Man a Future?, London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1963. Essays in Skepticism. New York: Philosophical Library.

- 1963. Unarmed Victory. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1965. On the Philosophy of Science, edited by Charles A. Fritz, Jr. Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Company.

- 1966. The A B C of relativity. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1967. Russell's Peace Appeals, edited by Tsutomu Makino and Kazuteru Hitaka. Japan: Eichosha's New Current Books.

- 1967. War Crimes in Vietnam. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- 1951–1969. The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 3 vols.. London: George Allen & Unwin. Vol 2 1956

- 1969. Dear Bertrand Russell... A Selection of his Correspondence with the General Public 1950–1968, edited by Barry Feinberg and Ronald Kasrils. London: George Allen and Unwin.

Russell also wrote many pamphlets, introductions, articles, and letters to the editor. One pamphlet titled, I Appeal unto Caesar: the case of the conscientious objectors, ghost written for Margaret Hobhouse, the mother of imprisoned peace activist Stephen Henry Hobhouse helped to secure the release of hundreds of CO's from prison.[65]

His works can be found in anthologies and collections, perhaps most notably The Collected Papers of Bertrand Russell, which McMaster University began publishing in 1983. This collection of his shorter and previously unpublished works is now up to 16 volumes, and many more are forthcoming. An additional three volumes catalogue just his bibliography. The Russell Archives at McMaster University possess over 30,000 of his letters.

See also

- Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club

- Structural realism (philosophy of science)[66]

- Russell's Paradox

Notes

- ^ a b Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1098/rsbm.1973.0021, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1098/rsbm.1973.0021instead. - ^ a b Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "Bertrand Russell", 1 May 2003

- ^ "I have imagined myself in turn a Liberal, a Socialist, or a Pacifist, but I have never been any of these things, in any profound sense." —Autobiography, p. 260.

- ^ Hestler, Anna (2001). Wales. Marshall Cavendish. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-7614-1195-6.

- ^ Ludlow, Peter, "Descriptions", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2008 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = [1].

- ^ Richard Rempel (1979). "From Imperialism to Free Trade: Couturat, Halevy and Russell's First Crusade". Journal of the History of Ideas. 40 (3). University of Pennsylvania Press: 423–443. doi:10.2307/2709246. JSTOR 2709246.

- ^ Bertrand Russell (1988) [1917]. Political Ideals. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-10907-8.

- ^ Samoiloff, Louise Cripps. C.L.R. James: Memories and Commentaries, p. 19. Associated University Presses, 1997. ISBN 0-8453-4865-5

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Bertrand Russell Gallery". Russell.mcmaster.ca. 6 June 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d The Nobel Foundation (1950). Bertrand Russell: The Nobel Prize in Literature 1950. Retrieved on 11 June 2007.

- ^ Sidney Hook, "Lord Russell and the War Crimes Trial", Bertrand Russell: critical assessments, Volume 1, edited by A. D. Irvine, (New York 1999) page 178

- ^ a b Bloy, Marjie, Ph.D. "Lord John Russell (1792–1878)". Retrieved 28 October 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Cokayne, G.E.; Vicary Gibbs, H.A. Doubleday, Geoffrey H. White, Duncan Warrand and Lord Howard de Walden, editors. The Complete Peerage of England, Scotland, Ireland, Great Britain and the United Kingdom, Extant, Extinct or Dormant, new ed. 13 volumes in 14. 1910–1959. Reprint in 6 volumes, Gloucester, UK: Alan Sutton Publishing, 2000.

- ^ The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide, 1866–1928 By Elizabeth Crawford

- ^ a b c Paul, Ashley. "Bertrand Russell: The Man and His Ideas". Archived from the original on 1 May 2006. Retrieved 28 October 2007.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand and Perkins, Ray (ed.) Yours faithfully, Bertrand Russell. Open Court Publishing, 2001, p. 4.

- ^ The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, p.38

- ^ Lenz, John R. (date unknown). "Bertrand Russell and the Greeks" (PDF). Retrieved 27 October 2007.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, p.35

- ^ "Bertrand Russell on God". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 1959. Retrieved 8 March 2010.

- ^ "Russell, the Hon. Bertrand Arthur William (RSL890BA)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ O'Connor, J. J. (2003). "Alfred North Whitehead". School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of St Andrews, Scotland. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Griffin, Nicholas. "Bertrand Russell's Mathematical Education". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 44, No. 1. pp. 51–71. Retrieved 8 November 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)(subscription required) - ^ Wallenchinsky et al. (1981), "Famous Marriages Bertrand...Part 1".

- ^ Wallenchinsky et al. (1981), "Famous Marriages Bertrand...Part 3".

- ^ Moran, Margaret (1991). "BERTRAND RUSSELL MEETS HIS MUSE: THE IMPACT OF LADY OTTOLINE MORRELL (1911-12)". McMaster University Library Press. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

- ^ Kimball, Roger. "Love, logic & unbearable pity: The private Bertrand Russell". The New Criterion Vol. 11, No. 1, September 1992. The New Criterion. Archived from the original on 5 December 2006. Retrieved 15 November 2007.

- ^ Simkin, John. "London School of Economics". Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2001). Ray Perkins (ed.). Yours Faithfully, Bertrand Russell: Letters to the Editor 1904–1969. Chicago: Open Court Publishing. p. 16. ISBN 0-8126-9449-X. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ^ "Bertrand Russell, Biography". Nobelprize.org. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ "Russell on Wittgenstein". Rbjones.com. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ Hochschild, Adam (2011), "'I Tried to Stop the Bloody Thing'", The American Scholar, retrieved 10 May 2011

- ^ Vellacott, Jo (1980). Bertrand Russell and the Pacifists in the First World War. Brighton: Harvester Press. ISBN 0-85527-454-9.

- ^ "Trinity in Literature". Trinity College. Retrieved 23 June 2010.

- ^ "Bertrand Russell (1872–1970)". Farlex, Inc. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ Bertrand Russell,The Practice and Theory of Bolshevism by Bertrand Russell, 1920

- ^ "Bertrand Russell Reported Dead" (PDF). The New York Times. 21 April 1921. Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (2000). Richard A. Rempel (ed.). Uncertain Paths to Freedom: Russia and China, 1919–22. Vol. 15. Routledge. lxviii. ISBN 0-415-09411-9.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Monk, Ray (2004). "'Russell, Bertrand Arthur William, third Earl Russell (1872–1970)'". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35875. Retrieved 14 March 2008.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)(subscription required) - ^ Inside Beacon Hill: Bertrand Russell as Schoolmaster. Jespersen, Shirley ERIC# EJ360344, published 1987

- ^ a b "Dora Russell". 12 May 2007. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ Russell, Bertrand, "The Future of Pacifism", The American Scholar, (1943) 13: 7–13

- ^ Leberstein, Stephen (November/December 2001). "Appointment Denied: The Inquisition of Bertrand Russell". Academe. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite news}}: Check date values in:|date=(help)[dead link] - ^ Einstein quotations and sources. Retrieved 9 July 2009.

- ^ "Bertrand Russell". 2006. Retrieved 17 February 2008.

- ^ a b Griffin, Nicholas (ed.) (2002). The Selected Letters of Bertrand Russell. Routledge. p. 660. ISBN 0-415-26012-4.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ "A philosopher's letters — Love, Bertie". The Economist.

- ^ 06:00–06:04. "Radio 4 Programmes — The Reith Lectures". BBC. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ 06:00–06:04. "Radio 4 Programmes — The Reith Lectures: Bertrand Russell: Authority and the Individual: 1948". BBC. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

{{cite web}}:|author=has numeric name (help) - ^ T. P. Uschanov, The Strange Death of Ordinary Language Philosophy. The controversy has been described by the writer Ved Mehta in Fly and the Fly Bottle (1963).

- ^ "No. 38628". The London Gazette (invalid

|supp=(help)). 3 June 1949. - ^ Ronald W. Clark, Bertrand Russell and His World, p94. (1981) ISBN 0-500-13070-1

- ^

Sanderson Beck (2003–2005). "Pacifism of Bertrand Russell and A. J. Muste". World Peace Efforts Since Gandhi. Sanderson Beck. Retrieved 24 June 2012.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date format (link) - ^ Peter Knight, The Kennedy Assassination, Edinburgh University Press Ltd., 2007, p. 77. Also see "External Links": "Sixteen Questions on the Assassination (of President Kennedy).

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (9 July 1955). "Russell Einstein Manifesto". Retrieved 17 February 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Jerusalem International Book Fair". Jerusalembookfair.com. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ [2].

- ^ Bertrand Russell's Last Message.

- ^ "Bertrand Russell Memorial". Mind. 353: 320. 1980.

- ^ Blanshard, in Paul Arthur Schilpp, ed., The Philosophy of Brand Blanshard, Open Court, 1980, p. 88, quoting a private letter from Russell.

- ^ The Existence of God: A Debate Between Russell and Father F.C.Copleston, SJ (1948) published in Why I Am Not A Christian (Routledge Classics), page 126

- ^ 'Humanist News', March 1970

- ^ Kunkle, Brett (15 March 2011). "Problem of Evil is Everyone's Problem". Truth Never Gets Old. conversantlife.com. Retrieved 30 June 2012.

- ^ Quoted in L. L. Clover, Evil Spirits Intellectualism and Logic (Minden, Louisiana: Louisiana Missionary Baptist Institute and Seminary, 1974), p. 55

- ^ Hochschild, Adam (2011). To end all wars: a story of loyalty and rebellion, 1914-1918. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 270–272. ISBN 0-618-75828-3.

- ^ Structural Realism: entry by James Ladyman in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Additional references

Russell

- 1900, Sur la logique des relations avec des applications à la théorie des séries, Rivista di matematica 7: 115–148.

- 1901, On the Notion of Order, Mind (n.s.) 10: 35–51.

- 1902, (with Alfred North Whitehead), On Cardinal Numbers, American Journal of Mathematics 23: 367–384.

- 1948, BBC Reith Lectures: Authority and the Individual A series of six radio lectures broadcast on the BBC Home Service in December 1948.

Secondary references

- John Newsome Crossley. A Note on Cantor's Theorem and Russell's Paradox, Australian Journal of Philosophy 51: 70–71.

- Ivor Grattan-Guinness, 2000. The Search for Mathematical Roots 1870–1940. Princeton University Press.

- Bertrand Russell: A Political Life by Alan Ryan 1981

Books about Russell's philosophy

- Bertrand Russell: Critical Assessments, edited by A. D. Irvine, 4 volumes, London: Routledge, 1999. Consists of essays on Russell's work by many distinguished philosophers.

- Bertrand Russell, by John Slater, Bristol: Thoemmes Press, 1994.

- Bertrand Russell's Ethics. by Michael K. Potter, Bristol: Thoemmes Continuum, 2006. A clear and accessible explanation of Russell's moral philosophy.

- The Philosophy of Bertrand Russell, edited by P.A. Schilpp, Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern University, 1944.

- Russell, by A. J. Ayer, London: Fontana, 1972. ISBN 0-00-632965-9. A lucid summary exposition of Russell's thought.

- The Lost Cause: Causation and the Mind-Body Problem, by Celia Green. Oxford: Oxford Forum, 2003. ISBN 0-9536772-1-4 Contains a sympathetic analysis of Russell's views on causality.

- Russell's Idealist Apprenticeship, by Nicholas Griffin. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Bertrand Russell’s Theory of Knowledge, by Elizabeth Ramsden Eames. London: George Allen and Unwin, 1969. A clear description of Russell’s philosophical development.

Biographical books

- Bertrand Russell: Philosopher and Humanist, by John Lewis (1968)

- Bertrand Russell, by A. J. Ayer (1972), reprint ed. 1988: ISBN 0-226-03343-0

- My father Bertrand Russell, by Katharine Tait (1975)

- The Life of Bertrand Russell, by Ronald W. Clark (1975) ISBN 0-394-49059-2

- Bertrand Russell and His World, by Ronald W. Clark (1981) ISBN 0-500-13070-1

- Bertrand Russell: Mathematics: Dreams and Nightmares by Ray Monk (1997) ISBN 0-7538-0190-6

- Bertrand Russell: 1872–1920 The Spirit of Solitude by Ray Monk (1997) ISBN 0-09-973131-2

- Bertrand Russell: 1921–1970 The Ghost of Madness by Ray Monk (2001) ISBN 0-09-927275-X

- Logicomix: An Epic Search for Truth by Apostolos Doxiadis, and Christos Papadimitriou (2009)

- 'Bertrand Russell', by George Santayana in Selected Writings of George Santayana, ed. Norman Henfrey, Cambridge : Cambridge University Press, I, 1968 : 326–9

- Bertrand Russell The Passionate Sceptic by Alan Wood, London: George Allen and Unwin, 1957. Russell had a good opinion of this author

- Russell Remembered by Rupert Crawshay-Williams, London: Oxford University Press, 1970. Written by a close friend of Russell's

Further reading

- Bertrand Russell. 1967–1969, The Autobiography of Bertrand Russell, 3 volumes, London: George Allen & Unwin.

- Wallechinsky, David & Irving Wallace. 1975–1981, "Famous Marriages Bertrand Russell & Alla Pearsall Smith, Part 1" & "Part 3", on "Alys" Pearsall Smith, webpage content from The People's Almanac, webpages: Part 1 & Part 3 (accessed 8 November 2008).

- Russell B, (1944) "My Mental Development", in Schilpp, Paul Arturn "The Philosophy of Betrand Russell", New York, Tudorm 1951, pp 3–20

External links

This article's use of external links may not follow Wikipedia's policies or guidelines. (October 2011) |

- Other writings available online

- Works by Bertrand Russell at Project Gutenberg

- Works by Bertrand Russell at Open Library

- "A Free Man's Worship" (1903)

- "The Elements of Ethics" (1910)

- War and Non-Resistance (1915)

- The War and Non-Resistance — A Rejoinder to Professor Perry (1915)

- The Ethics of War (1915)

- Justice in Wartime (1917)

- Why Men Fight: A Method of Abolishing the International Duel (1917)

- "Has Religion Made Useful Contributions to Civilization?" 1930

- Legitimacy Versus Industrialism 1814–1848 (1935)

- "Am I an Atheist or an Agnostic?" (1947)

- "Ideas that Have Harmed Mankind" (1950)

- "What Desires Are Politically Important?" (1950)

- An Outline of Philosophy (1951)

- Is There a God? (1952)

- Russell, Bertrand (1953). "What is an Agnostic?". Archived from the original on 2 February 2008.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 3 February 2008 suggested (help) - The Scientific Outlook (1954)

- "16 Questions on the Assassination" (of President Kennedy) (1964)

- Audio

- Other

- Template:Worldcat id

- Pembroke Lodge — childhood home and museum

- The Bertrand Russell Society Quarterly

- The Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation

- Bertrand Russell at IMDb

- Bertrand Russell in Japan

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Bertrand Russell", MacTutor History of Mathematics Archive, University of St Andrews

- Photographs at the National Portrait Gallery (London)

- AD. Irvine (1 May 2003). "Bertrand Russell". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Bertrand Russell Archives at McMaster University

- Resource list

- The First Reith Lecture given by Russell (Real Audio)

- Nobel Prize

- Bertrand Russell at 100 Welsh Heroes

- Key Participants: Bertrand Russell — Linus Pauling and the International Peace Movement: A Documentary History

- PM@100: LOGIC FROM 1910 TO 1927 Conference at the Bertrand Russell Research Centre (McMaster University, Ontario, Canada), to be held on 21–24 May 2010, celebrating the 100th anniversary of the publication of Principia Mathematica.

- Bertrand Russell Society Bulletin (2011–present)(Kris Notaro and David Blitz)

- Wikipedia external links cleanup from October 2011

- Use dmy dates from September 2011

- 1872 births

- 1970 deaths

- 19th-century philosophers

- 19th-century mathematicians

- 20th-century mathematicians

- 20th-century philosophers

- Academics of the London School of Economics

- Analytic philosophers

- Anti–Vietnam War activists

- Anti–World War I activists

- Atheist philosophers

- Atheism activists

- Bertrand Russell

- British anti–nuclear weapons activists

- British Nobel laureates

- British republicans

- British humanists

- British polymaths

- Democratic socialists

- English logicians

- English pacifists

- English prisoners and detainees

- Cambridge University Moral Sciences Club

- Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

- Critics of work and the work ethic

- De Morgan Medallists

- Deaths from influenza

- Earls in the Peerage of the United Kingdom

- English atheists

- English historians of philosophy

- English sceptics

- Epistemologists

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of Trinity College, Cambridge

- Free love advocates

- Infectious disease deaths in Wales

- Kalinga Prize recipients

- Linguistic turn

- LGBT rights activists from the United Kingdom

- Male feminists

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Nobel laureates in Literature

- Ontologists

- People from Monmouthshire

- Philosophers of language

- Philosophers of mathematics

- Russell family

- Set theorists

- University of California, Los Angeles faculty

- University of Chicago faculty

- Utilitarians

- Western writers about Soviet Russia

- World federalists

- English Nobel laureates

- English people of Scottish descent