Bob Marley

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Bob Marley | |

|---|---|

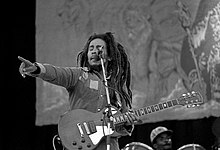

Bob Marley performing in concert, circa 1980. | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Nesta Robert Marley |

| Also known as | Tuff Gong |

| Born | 6 February 1945 Nine Mile, Saint Ann, Jamaica |

| Died | 11 May 1981 (aged 36) Miami, Florida, U.S. |

| Genres | Reggae, ska, rocksteady |

| Occupation(s) | Singer-songwriter, musician |

| Instrument(s) | Vocals, guitar, piano, saxophone, harmonica, percussion, horn |

| Years active | 1962–1981 |

| Labels | Studio One, Upsetter, Tuff Gong |

| Website | bobmarley |

Nesta Robert "Bob" Marley, OM (6 February 1945 – 11 May 1981) was a Jamaican singer-songwriter and musician. He was the rhythm guitarist and lead singer for the ska, rocksteady and reggae bands The Wailers (1963-1974) and Bob Marley & The Wailers (1974–1981). Marley remains the most widely known and the best-selling performer of reggae music, having sold more than 75 million albums worldwide.[1] He is also credited with helping spread both Jamaican music and the Rastafari movement to a worldwide audience.[2]

Marley's music was heavily influenced by the social issues of his homeland, and he is considered to have given voice to the specific political and cultural nexus of Jamaica.[3] His best-known hits include "I Shot the Sheriff", "No Woman, No Cry", "Could You Be Loved", "Duppy Conqueror", "Stir It Up", "Get Up Stand Up", "Jamming", "Redemption Song", "One Love" and, "Three Little Birds",[4] as well as the posthumous releases "Buffalo Soldier" and "Iron Lion Zion". The compilation album Legend (1984), released three years after his death, is reggae's best-selling album, going ten times Platinum which is also known as one Diamond in the U.S.,[5] and selling 25 million copies worldwide.[6][7]

Early life and career

Bob Marley was born in the village of Nine Mile, in Saint Ann Parish, Jamaica, as Nesta Robert Marley.[8]A Jamaican passport official would later swap his first and middle names.[9] He was of mixed race. His father, Norval Sinclair Marley, was a White English-Jamaican,[10] whose family came from Sussex, England. Norval claimed to have been a captain in the Royal Marines.[11] He was a plantation overseer, when he married Cedella Booker, an Afro-Jamaican then 18 years old.[12] Norval provided financial support for his wife and child, but seldom saw them, as he was often away on trips. In 1955, when Bob Marley was 10 years old, his father died of a heart attack at age 70.[13] Marley faced questions about his own racial identity throughout his life. He once reflected:

I don't have prejudice against meself. My father was a white and my mother was black. Them call me half-caste or whatever. Me don't deh pon nobody's side. Me don't deh pon the black man's side nor the white man's side. Me deh pon God's side, the one who create me and cause me to come from black and white.[14]

Although Marley recognised his mixed ancestry, throughout his life and because of his beliefs, he self-identified as a black African, following the ideas of Pan-African leaders. Marley stated that his two biggest influences were the African-centered Marcus Garvey and Haile Selassie. A central theme in Bob Marley's message was the repatriation of black people to Zion, which in his view was Ethiopia, or more generally, Africa.[15] In songs such as "Survival", "Babylon System", and "Blackman Redemption", Marley sings about the struggles of blacks and Africans against oppression from the West or "Babylon".[16]

Marley met Neville Livingston (later changed to Bunny Wailer) in Nine Mile because Bob's mother had a daughter with Bunny's father, younger sister to both of them and also had a relationship with him. Marley and Livingston started to play music while he was still at school. Then Marley left Nine Mile when he was 12 with his mother to Trench Town, Kingston. While in Trench Town, he met up with Livingston again and they started to make music with Joe Higgs, a local singer and devout Rastafari. At a jam session with Higgs and Livingston, Marley met Peter McIntosh (later known as Peter Tosh), who had similar musical ambitions.[17] In 1962, Marley recorded his first two singles, "Judge Not" and "One Cup of Coffee", with local music producer Leslie Kong. These songs, released on the Beverley's label under the pseudonym of Bobby Martell,[18] attracted little attention. The songs were later re-released on the box set Songs of Freedom, a posthumous collection of Marley's work.

Bob Marley & The Wailers

1963–1974

In 1963, Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer, Peter Tosh, Junior Braithwaite, Beverley Kelso, and Cherry Smith formed a ska and rocksteady group, calling themselves "The Teenagers". They later changed their name to "The Wailing Rudeboys", then to "The Wailing Wailers", at which point they were discovered by record producer Coxsone Dodd, and finally to "The Wailers". By 1966, Braithwaite, Kelso, and Smith had left The Wailers, leaving the core trio of Bob Marley, Bunny Wailer, and Peter Tosh.[19]

In 1966, Marley married Rita Anderson, and moved near his mother's residence in Wilmington, Delaware in the United States for a short time, during which he worked as a DuPont lab assistant and on the assembly line at a Chrysler plant, under the alias Donald Marley.[20]

Though raised in the Catholic tradition, Marley became captivated by Rastafarian beliefs in the 1960s, when away from his mother's influence.[8] Formally converted to Rastafari after returning to Jamaica, Marley began to wear his trademark dreadlocks (see the religion section for more on Marley's religious views). After a conflict with Dodd, Marley and his band teamed up with Lee "Scratch" Perry and his studio band, The Upsetters. Although the alliance lasted less than a year, they recorded what many consider The Wailers' finest work. Marley and Perry split after a dispute regarding the assignment of recording rights, but they would remain friends and work together again.

Between 1968 and 1972, Bob and Rita Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer re-cut some old tracks with JAD Records in Kingston and London in an attempt to commercialise The Wailers' sound. Bunny later asserted that these songs "should never be released on an album ... they were just demos for record companies to listen to". Also in 1968, Bob and Rita visited the Bronx to see Johnny Nash's songwriter Jimmy Norman.[23] A three-day jam session with Norman and others, including Norman's co-writer Al Pyfrom, resulted in a 24-minute tape of Marley performing several of his own and Norman-Pyfrom's compositions. This tape is, according to Reggae archivist Roger Steffens, rare in that it was influenced by pop rather than reggae, as part of an effort to break Marley into the American charts.[23] According to an article in The New York Times, Marley experimented on the tape with different sounds, adopting a doo-wop style on "Stay With Me" and "the slow love song style of 1960's artists" on "Splish for My Splash".[23] An artist yet to establish himself outside his native Jamaica, Marley lived in Ridgmount Gardens, Bloomsbury, London during 1972.[21][22]

In 1972, the Wailers entered into an ill-fated deal with CBS Records and embarked on a tour with American soul singer Johnny Nash. Broke, the Wailers became stranded in London. Marley turned up at Island Records founder and producer Chris Blackwell's London office, and asked him to advance the cost of a new single. Since Jimmy Cliff, Island's top reggae star, had recently left the label, Blackwell was primed for a replacement. In Marley, Blackwell recognized the elements needed to snare the rock audience: "I was dealing with rock music, which was really rebel music. I felt that would really be the way to break Jamaican music. But you needed someone who could be that image. When Bob walked in he really was that image."[24] Blackwell told Marley he wanted The Wailers to record a complete album (essentially unheard of at the time). When Marley told him it would take between £3,000 and £4,000, Blackwell trusted him with the greater sum. Despite their "rude boy" reputation, the Wailers returned to Kingston and honored the deal, delivering the album Catch a Fire.

Primarily recorded on eight-track at Harry J's in Kingston, Catch a Fire marked the first time a reggae band had access to a state-of-the-art studio and were accorded the same care as their rock'n'roll peers.[24] Blackwell desired to create "more of a drifting, hypnotic-type feel than a reggae rhythm",[25] and restructured Marley's mixes and arrangements. Marley travelled to London to supervise Blackwell's overdubbing of the album, which included tempering the mix from the bass-heavy sound of Jamaican music, and omitting two tracks.[24]

The Wailers' first major label album, Catch a Fire was released worldwide in April 1973, packaged like a rock record with a unique Zippo lighter lift-top. Initially selling 14,000 units, it didn't make Marley a star, but received a positive critical reception.[24] It was followed later that year by Burnin', which included the standout songs "Get Up, Stand Up", and "I Shot the Sheriff", which appealed to the ear of Eric Clapton. He recorded a cover of the track in 1974 which became a huge American hit, raising Marley's international profile.[26] Many Jamaicans were not keen on the new "improved" reggae sound on Catch a Fire, but the Trenchtown style of Burnin' found fans across both reggae and rock audiences.[24]

During this period, Blackwell gifted his Kingston residence and company headquarters at 56 Hope Road (then known as Island House) to Marley. Housing Tuff Gong Studios, the property became not only Marley's office, but also his home.[24]

The Wailers were scheduled to open 17 shows for the number one black act in the States, Sly and the Family Stone. After 4 shows, the band was fired because they were more popular than the acts they were opening for.[27] The Wailers broke up in 1974 with each of the three main members pursuing solo careers. The reason for the breakup is shrouded in conjecture; some believe that there were disagreements amongst Bunny, Peter, and Bob concerning performances, while others claim that Bunny and Peter simply preferred solo work.

1974–1981

Despite the break-up, Marley continued recording as "Bob Marley & The Wailers". His new backing band included brothers Carlton and Aston "Family Man" Barrett on drums and bass respectively, Junior Marvin and Al Anderson on lead guitar, Tyrone Downie and Earl "Wya" Lindo on keyboards, and Alvin "Seeco" Patterson on percussion. The "I Threes", consisting of Judy Mowatt, Marcia Griffiths, and Marley's wife, Rita, provided backing vocals. In 1975, Marley had his international breakthrough with his first hit outside Jamaica, "No Woman, No Cry", from the Natty Dread album. This was followed by his breakthrough album in the United States, Rastaman Vibration (1976), which spent four weeks on the Billboard Hot 100.[28]

Assassination attempt

On 3 December 1976, two days before "Smile Jamaica", a free concert organised by the Jamaican Prime Minister Michael Manley in an attempt to ease tension between two warring political groups, Marley, his wife, and manager Don Taylor were wounded in an assault by unknown gunmen inside Marley's home. Taylor and Marley's wife sustained serious injuries, but later made full recoveries. Bob Marley received minor wounds in the chest and arm.[29] The attempt on his life was thought to have been politically motivated, as many felt the concert was really a support rally for Manley. Nonetheless, the concert proceeded, and an injured Marley performed as scheduled, two days after the attempt. When asked why, Marley responded, "The people who are trying to make this world worse aren't taking a day off. How can I?" The members of the group Zap Pow, which had no radical religious or political beliefs, played as Bob Marley's backup band before a festival crowd of 80,000 while members of The Wailers were still missing or in hiding.[30][31]

Afterward

Marley left Jamaica at the end of 1976, and after a month-long "recovery and writing" sojourn at the site of Chris Blackwell's Compass Point Studios in Nassau, Bahamas, arrived in England, where he spent two years in self-imposed exile. Whilst there he recorded the albums Exodus and Kaya. Exodus stayed on the British album charts for 56 consecutive weeks. It included four UK hit singles: "Exodus", "Waiting in Vain", "Jamming", and "One Love" (a rendition of Curtis Mayfield's hit, "People Get Ready"). During his time in London, he was arrested and received a conviction for possession of a small quantity of cannabis.[32] In 1978, Marley returned to Jamaica and performed at another political concert, the One Love Peace Concert, again in an effort to calm warring parties. Near the end of the performance, by Marley's request, Michael Manley (leader of then-ruling People's National Party) and his political rival Edward Seaga (leader of the opposing Jamaica Labour Party), joined each other on stage and shook hands.[33]

Under the name Bob Marley and the Wailers eleven albums were released, four live albums and seven studio albums. The releases included Babylon by Bus, a double live album with thirteen tracks, were released in 1978 and received critical acclaim. This album, and specifically the final track "Jamming" with the audience in a frenzy, captured the intensity of Marley's live performances.[34]

"Marley wasn't singing about how peace could come easily to the World but rather how hell on Earth comes too easily to too many. His songs were his memories; he had lived with the wretched, he had seen the downpressers and those whom they pressed down."

Survival, a defiant and politically charged album, was released in 1979. Tracks such as "Zimbabwe", "Africa Unite", "Wake Up and Live", and "Survival" reflected Marley's support for the struggles of Africans. His appearance at the Amandla Festival in Boston in July 1979 showed his strong opposition to South African apartheid, which he already had shown in his song "War" in 1976. In early 1980, he was invited to perform at the 17 April celebration of Zimbabwe's Independence Day. Uprising (1980) was Bob Marley's final studio album, and is one of his most religious productions; it includes "Redemption Song" and "Forever Loving Jah".[36] Confrontation, released posthumously in 1983, contained unreleased material recorded during Marley's lifetime, including the hit "Buffalo Soldier" and new mixes of singles previously only available in Jamaica.[37]

Personal life

Religion

Bob Marley was a member for some years of the Rastafari movement, whose culture was a key element in the development of reggae. Bob Marley became an ardent proponent of Rastafari, taking their music out of the socially deprived areas of Jamaica and onto the international music scene. He once gave the following response, which was typical, to a question put to him during a recorded interview:

- Interviewer: "Can you tell the people what it means being a Rastafarian?"

- Bob: "I would say to the people, Be still, and know that His Imperial Majesty, Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia is the Almighty. Now, the Bible seh so, Babylon newspaper seh so, and I and I the children seh so. Yunno? So I don't see how much more reveal our people want. Wha' dem want? a white God, well God come black. True true."[38]

Observant of the Rastafari practice Ital, a diet that shuns meat, Marley was a vegetarian.[39] According to his biographers, he affiliated with the Twelve Tribes Mansion. He was in the denomination known as "Tribe of Joseph", because he was born in February (each of the twelve sects being composed of members born in a different month). He signified this in his album liner notes, quoting the portion from Genesis that includes Jacob's blessing to his son Joseph.

Marley was baptised into Christianity by Archbishop Abuna Yesehaq of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church in Kingston, Jamaica, on 4 November 1980.[40][41]

Family

Bob Marley had a number of children: three with his wife Rita, two adopted from Rita's previous relationships, and several others with different women. The Bob Marley official website acknowledges eleven children.

Those listed on the official site are:

- Sharon, born 23 November 1964, daughter of Rita from a previous relationship but then adopted by Marley after his marriage with Rita

- Cedella born 23 August 1967, to Rita

- David "Ziggy", born 17 October 1968, to Rita

- Stephen, born 20 April 1972, to Rita

- Robert "Robbie", born 16 May 1972, to Pat Williams

- Rohan, born 19 May 1972, to Janet Hunt

- Karen, born 1973 to Janet Bowen

- Stephanie, born 17 August 1974; according to Cedella Booker she was the daughter of Rita and a man called Ital with whom Rita had an affair; nonetheless she was acknowledged as Bob's daughter

- Julian, born 4 June 1975, to Lucy Pounder

- Ky-Mani, born 26 February 1976, to Anita Belnavis

- Damian, born 21 July 1978, to Cindy Breakspeare

Makeda was born on 30 May 1981, to Yvette Crichton, after Marley's death.[42] Meredith Dixon's book lists her as Marley's child, but she is not listed as such on the Bob Marley official website.

Various websites, for example,[43] also list Imani Carole, born 22 May 1963 to Cheryl Murray; but she does not appear on the official Bob Marley website.[42]

Final years and death

In July 1977, Marley was found to have a type of malignant melanoma under the nail of one of his toes. Contrary to urban legend, this lesion was not primarily caused by an injury during a football match in that year, but was instead a symptom of the already existing cancer. Marley turned down doctors' advice to have his toe amputated, citing his religious beliefs.[44] Despite his illness, he continued touring and was in the process of scheduling a world tour in 1980. The intention was for Inner Circle to be his opening act on the tour but after their lead singer Jacob Miller died in Jamaica in March 1980 after returning from a scouting mission in Brazil this was no longer mentioned.[45]

The album Uprising was released in May 1980 (produced by Chris Blackwell), on which "Redemption Song" is particularly considered to be about Marley coming to terms with his mortality.[citation needed] The band completed a major tour of Europe, where they played their biggest concert to a hundred thousand people in Milan. After the tour Marley went to America, where he performed two shows at Madison Square Garden as part of the Uprising Tour.

The final concert of Bob Marley's career was held 23 September 1980 at the Stanley Theater (now called The Benedum Center For The Performing Arts) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The audio recording of that concert is now available on CD, vinyl, and digital music services.

Shortly after, Marley's health deteriorated and he became very ill; the cancer had spread throughout his body. The rest of the tour was cancelled and Marley sought treatment at the Bavarian clinic of Josef Issels, where he received a controversial type of cancer therapy (Issels treatment) partly based on avoidance of certain foods, drinks, and other substances. After fighting the cancer without success for eight months, Marley boarded a plane for his home in Jamaica.[46]

While flying home from Germany to Jamaica, Marley's vital functions worsened. After landing in Miami, Florida, he was taken to the hospital for immediate medical attention. He died at Cedars of Lebanon Hospital in Miami (now University of Miami Hospital) on the morning of 11 May 1981, at the age of 36. The spread of melanoma to his lungs and brain caused his death. His final words to his son Ziggy were "Money can't buy life".[47] Marley received a state funeral in Jamaica on 21 May 1981, which combined elements of Ethiopian Orthodoxy[48][49] and Rastafari tradition.[50] He was buried in a chapel near his birthplace with his red Gibson Les Paul (some accounts say it was a Fender Stratocaster).[51]

On 21 May 1981, Jamaican Prime Minister Edward Seaga delivered the final funeral eulogy to Marley, declaring:

His voice was an omnipresent cry in our electronic world. His sharp features, majestic looks, and prancing style a vivid etching on the landscape of our minds. Bob Marley was never seen. He was an experience which left an indelible imprint with each encounter. Such a man cannot be erased from the mind. He is part of the collective consciousness of the nation.[52]

Legacy

Bob Marley was the Third World's first pop superstar. He was the man who introduced the world to the mystic power of reggae. He was a true rocker at heart, and as a songwriter, he brought the lyrical force of Bob Dylan, the personal charisma of John Lennon, and the essential vocal stylings of Smokey Robinson into one voice.

In 1999 TIME magazine chose Bob Marley & The Wailers' Exodus as the greatest album of the 20th century.[54] In 2001, he was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award, and a feature-length documentary about his life, Rebel Music, won various awards at the Grammys. With contributions from Rita, The Wailers, and Marley's lovers and children, it also tells much of the story in his own words.[55] A statue was inaugurated, next to the national stadium on Arthur Wint Drive in Kingston to commemorate him. In 2006, the State of New York renamed a portion of Church Avenue from Remsen Avenue to East 98th Street in the East Flatbush section of Brooklyn "Bob Marley Boulevard".[56] In 2008, a statue of Marley was inaugurated in Banatski Sokolac, Serbia.[57]

Internationally, Marley's message also continues to reverberate amongst various indigenous communities. For instance, the Aboriginal people of Australia continue to burn a sacred flame to honor his memory in Sydney's Victoria Park, while members of the Native American Hopi and Havasupai tribe revere his work.[58] There are also many tributes to Bob Marley throughout India, including restaurants, hotels, and cultural festivals.[59][60]

Marley has also evolved into a global symbol, which has been endlessly merchandised through a variety of mediums. In light of this, author Dave Thompson in his book Reggae and Caribbean Music, laments what he perceives to be the commercialized pacification of Marley's more militant edge, stating:

Bob Marley ranks among both the most popular and the most misunderstood figures in modern culture ... That the machine has utterly emasculated Marley is beyond doubt. Gone from the public record is the ghetto kid who dreamed of Che Guevara and the Black Panthers, and pinned their posters up in the Wailers Soul Shack record store; who believed in freedom; and the fighting which it necessitated, and dressed the part on an early album sleeve; whose heroes were James Brown and Muhammad Ali; whose God was Ras Tafari and whose sacrament was marijuana. Instead, the Bob Marley who surveys his kingdom today is smiling benevolence, a shining sun, a waving palm tree, and a string of hits which tumble out of polite radio like candy from a gumball machine. Of course it has assured his immortality. But it has also demeaned him beyond recognition. Bob Marley was worth far more.[61]

In the film I Am Legend, Dr. Robert Neville (Will Smith) plays Bob Marley's music early in the film. Later, he tells fellow survivor Anna (Alice Braga) - while playing more of Bob Marley's music - that he and his wife named their daughter, Marley, after the artist. Neville also recounts Bob Marley's philosophy and the circumstances of the artist's death.

Film adaptations

In February 2008, director Martin Scorsese announced his intention to produce a documentary movie on Marley. The film was set to be released on 6 February 2010, on what would have been Marley's 65th birthday.[62] However, Scorsese dropped out due to scheduling problems. He was replaced by Jonathan Demme,[63] who dropped out due to creative differences with producer Steve Bing during the beginning of editing. Kevin Macdonald replaced Demme[64] and the film, Marley, was released on 20 April 2012.

In March 2008, The Weinstein Company announced its plans to produce a biopic of Bob Marley, based on the book No Woman No Cry: My Life With Bob Marley by Rita Marley. Rudy Langlais will produce the script by Lizzie Borden and Rita Marley will be executive producer.[65]

Ex-girlfriend and filmmaker Esther Anderson, along with Gian Godoy, made the documentary Bob Marley: The Making of a Legend, which premiered at the Edinburgh International Film Festival in 2011.[66]

In 2012, director Kevin McDonald teamed with the Marley family to make the documentary, Marley. It was entered as a film for SXSW Film Festival and Hot Docs 2012.

Crustacean species

A Caribbean parasite Gnathia marleyi was named after Marley.[67][68][69]

Discography

- The Wailing Wailers (1965)

- Soul Rebels (1970)

- Soul Revolution (1971)

- The Best of The Wailers (1971)

- Catch a Fire (1973)

- Burnin' (1973)

- Natty Dread (1974)

- Rastaman Vibration (1976)

- Exodus (1977)

- Kaya (1978)

- Survival (1979)

- Uprising (1980)

- Confrontation (1983)

Awards and honors

- 1976: Band of the Year (Rolling Stone).

- June 1978: Awarded the Peace Medal of the Third World from the United Nations.[58]

- February 1981: Awarded Jamaica's third highest honour, the Jamaican Order of Merit.

- March 1994: Inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

- 1999: Album of the Century for Exodus by Time Magazine.

- February 2001: A star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

- February 2001: Awarded Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award.

- 2004: Rolling Stone ranked him No.11 on their list of the 100 Greatest Artists of All Time.[70]

- "One Love" named song of the millennium by BBC.

- Voted as one of the greatest lyricists of all time by a BBC poll.[71]

- 2006: A blue plaque was unveiled at his first UK residence in Ridgmount Gardens, London, dedicated to him by Nubian Jak community trust and supported by Her Majesty's Foreign Office.[72]

- 2010: Catch a Fire inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame (Reggae Album).[73]

See also

References

- ^ "Michael Jackson, Elvis Presley Are Top-Earning Dead Musicians". Rolling Stone. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- ^ "2007 Pop Conference Bios/Abstracts". Experience Music Project and Science Fiction Museum and Hall of Fame. 2007.

- ^ "Bob Marley". Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ "Bob Marley". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2006.

- ^ Miller, Doug (26 February 2007). "Concert Series: 'No Woman, No Cry'". web.BobMarley.com. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Newcomb, Peter (25 October 2004). "Top Earners for 2004". Forbes. p. 9. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ "Rolling in the money". iAfrica. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ^ a b Moskowtz, David Vlado (2007). The Words and Music of Bob Marley. Westport, Connecticut. p. 16. ISBN 0-275-98935-6, ISBN 978-0-275-98935-4.

- ^ Moskowitz 2007, p. 9

- ^ Ziggy Marley to adopt Judaism?, Observer Reporter, Thursday, 13 April 2006, Jamaica Observer

- ^ Bob Marley: the regret that haunted his life Tim Adams, The Observer, Sunday 8 April 2012

- ^ Moskowitz 2007, p. 2

- ^ Moskowitz 2007, p. 4

- ^ Webley, Bishop Derek (10 May 2008). "One world, one love, one Bob Marley". Birmingham Post. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ "Religion and Ethics: Rastafari – Bob Marley". BBC.

- ^ Middleton 2000, pp. 181–198

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Bob Marley – Biography". Allmusic. Retrieved 15 June 2008.

- ^ "The Beverley Label and Leslie Kong: Music Business". bobmarley.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2006.

- ^ "The Wailers'Biography". Vital Spot. Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 1 October 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 10 September 2007 suggested (help) - ^ White, Timothy (25 June 1981). "Bob Marley: 1945–1981". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. Archived from the original on 21 April 2009.

- ^ a b Bob Marley's London home on the Music Pilgrimages website.

- ^ a b Muir, Hugh (27 October 2006). "Blue plaque marks flats that put Marley on road to fame". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- ^ a b c McKinley, Jesse (19 December 2002). "Pre-reggae tape of Bob Marley is found and put on auction". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Hagerman, Brent (February 2005). "Chris Blackwell: Savvy Svengali". Exclaim.ca. Retrieved 29 December 2010.

- ^ [Quoted in the liner notes to 2001 reissue of Catch a Fire, written by Richard Williams]

- ^ "I Shot the Sheriff". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. 9 December 2004. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ "Bob Marley Biography". admin. 9 August 2010. Retrieved November 2010.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ "Bob Marley Bio". niceup.com. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Moskowitz 2007, pp. 71–73

- ^ "The shooting of a Wailer". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. 13 January 1997. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ^ Walker, Jeff (1980) on the cover of Zap Pow's LP Reggae Rules. Los Angeles: Rhino Records.

- ^ "A Timeline of Bob Marley's Career". Thirdfield.com. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ "One Love Peace Concert". Everything2.com. 24 May 2002. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ White, Timothy (28 December 1978). "Babylon by Bus review". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Henke 2006, p. 61

- ^ Morris, Chris (16 October 1980). "Uprising review". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

- ^ Schruers, Fred (1 September 1983). "Confrontation review". Rolling Stone. Jann Wenner. Archived from the original on 1 December 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2009.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=/|archive-url=timestamp mismatch; 25 February 2007 suggested (help) - ^ Davis, Steven, Bob Marley: the biography (1983) p. 115

- ^ "Bob Marley". The International Vegetarian Union. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- ^ "The Ethiopian Orthodox Church & Bob Marley's Baptism And The Church". Jamaicans.com.

- ^ "Bob Marley's Baptism in Ethiopian Orthodox Church". Rastafarispeaks.com.

- ^ a b Dixon, Meredith. "Lovers and Children of the Natural Mystic: The Story of Bob Marley, Women and their Children". The Dread Library. Retrieved 21 June 2007.

- ^ "Bob Marley's Children". Chelsea's Entertainment Reviews. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

- ^ "A Death by Skin Cancer? The Bob Marley Story". The Tribune. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011. [dead link]

- ^ Slater, Russ (6 August 2010). "The Day Bob Marley Played Football in Brazil". Sounds and Colours. Retrieved 6 August 2010.

- ^ "His story: The life and legacy of Bob Marley". web.bobmarley.com. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ "Why Did Bob Marley Die – What Did Bob Marley Die From". Worldmusic.about.com. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ "Bob Marley's funeral program". Orthodoxhistory.org. Retrieved 4 June 2010.

- ^ "30 Year Anniversary of Bob Marley's Death". Orthodoxhistory.org. Retrieved 11 May 2011.

- ^ Moskowitz 2007, p. 116

- ^ "Bob Marley". Find a Grave. 1 January 2001. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ Henke 2006, p. 58

- ^ Henke 2006, p. 4

- ^ "The Best Of The Century". Time. Time Inc. 31 December 1999. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ^ "Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award for Bob Marley". Caribbean Today. 31 January 2001. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ "Brooklyn Street Renamed Bob Marley Boulevard". NY1. 2 July 2006. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- ^ "n. Marinković, "Marli u Sokolcu"". Politika.rs. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- ^ a b Henke 2006, p. 5

- ^ Singh, Sarina (2009). Lonely Planet India. Oakland, CA: Lonely Planet. p. 1061. ISBN 978-1-74179-151-8. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Bob Marley Cultural Fest 2010". Cochin Square. 4 May 2010. Retrieved 7 July 2011.

- ^ Reggae and Caribbean Music, by Dave Thompson, Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002, ISBN 0-87930-655-6, pp. 159

- ^ Winter Miller (17 February 2008). "Scorsese to make Marley documentary". Ireland On-Line. Retrieved 6 March 2008.

- ^ "Martin Scorsese Drops Out of Bob Marley Documentary". WorstPreviews.com. 22 May 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2008.

- ^ Kevin Jagernauth (2 February 2011). "Kevin Macdonald Takes Over 'Marley' Doc From Jonathan Demme". indieWire. Retrieved 22 February 2012.

- ^ Miller, Winter (3 March 2008). "Weinstein Co. options Marley". Variety. Reed Business Information. Retrieved 3 March 2008.

- ^ Elaine Downs (23 June 2011). "Edinburgh International Film Festival 2011: Bob Marley – the Making of a Legend | News | Edinburgh | STV". Local.stv.tv. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Jeanna Bryner (10 July 2012). "Better than nothing? Bloodsucking parasite named after Bob Marley". CSMonitor.com. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ Rob Preece (13 July 2012). "Blood-sucking fish parasite named after Bob Marley as tribute | Mail Online". Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "No crustacean, no cry? Bob Marley gets his own species". Reuters. 10 July 2012. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ^ "The Immortals: The First Fifty". Rolling Stone Issue 946. Jann Wenner.

- ^ "Who is the greatest lyricist of all time". BBC. 23 May 2001.

- ^ "London honours legendary reggae artist Bob Marley with heritage plaque". AfricaUnite.org.

- ^ "Grammy Hall of Fame Awards Complete Listing". Grammy.com.

Further reading

- Farley, Christopher (2007). Before the Legend: The Rise of Bob Marley, Amistad Press ISBN 0-06-053992-5

- Goldman, Vivien (2006). The Book of Exodus: The Making and Meaning of Bob Marley and the Wailers' Album of the Century, Aurum Press ISBN 1-84513-210-6

- Henke, James (2006). Marley Legend: An Illustrated Life of Bob Marley. Tuff Gong books. ISBN 0-8118-5036-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Marley, Rita; Jones, Hettie (2004) No Woman No Cry: My Life with Bob Marley Hyperion Books ISBN 0-7868-8755-9

- Masouri, John (2007) Wailing Blues: The Story of Bob Marley's "Wailers" Wise Publications ISBN 1-84609-689-8

- Middleton, J. Richard (2000). "Identity and Subversion in Babylon: Strategies for 'Resisting Against the System' in the Music of Bob Marley and the Wailers". Religion, Culture, and Tradition in the Caribbean. St. Martin's Press. pp. 181–198. ISBN 978-0-312-23242-9.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Moskowitz, David (2007). The Words and Music of Bob Marley. Westport, Connecticut, United States: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-98935-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - White, Timothy (2006). Catch a Fire: The Life of Bob Marley. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-8050-8086-4.

External links

- Official website

- Bob Marley at IMDb

- Bob Marley at Rolling Stone

- Showcase: Bob Marley by James Estrin, The New York Times, 18 May 2009

- Articles with bare URLs for citations from April 2013

- Wikipedia articles needing copy edit from April 2013

- Use dmy dates from November 2012

- 1945 births

- 1981 deaths

- Anti-apartheid activists

- Attempted assassination survivors

- Cancer deaths in Florida

- Cannabis culture

- Converts to Christianity

- Converts to the Rastafari movement

- Deaths from skin cancer

- Ethiopian Orthodox Christians

- Former Roman Catholics

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Jamaican expatriates in the United Kingdom

- Jamaican expatriates in the United States

- Jamaican male singers

- Jamaican people of English descent

- Jamaican people of African descent

- Jamaican Rastafarians

- Jamaican reggae singers

- Jamaican songwriters

- Marley family

- Pan-Africanism

- Performers of Rastafarian music

- People from Saint Ann Parish

- People from Wilmington, Delaware

- Resonator guitarists

- Rock and Roll Hall of Fame inductees

- Recipients of the Order of Merit (Jamaica)

- Shooting survivors

- The Wailers members

- Jamaican Christians

- Colony of Jamaica people