White supremacy

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

White supremacy is the belief of, and/or promotion of the belief, that white people are superior to people of other racial backgrounds and that therefore whites should politically dominate non-whites. The term is also used to describe a political ideology that perpetuates and maintains the social, political, historical and/or industrial dominance of whites.[1] Different forms of white supremacy have different conceptions of who is considered white, and different white supremacist identify various groups as their primary enemy.[2]

White supremacist groups can be found in most countries and regions with a significant white population. The militant approach taken by white supremacist groups has caused them to be watched closely by law enforcement officials. Some have even been labelled as terrorist groups. Some European countries prohibit white supremacist political activity or the expression of white supremacist ideas.

History of White supremacy

Template:Globalize/US White supremacy was dominant in the United States before the American Civil War and for decades after Reconstruction.[3] In large areas of the United States, this included the holding of non-whites (specifically African Americans) in chattel slavery. The outbreak of the Civil War saw the desire to uphold white supremacy cited as a cause for state secession[4] and the formation of the Confederate States of America.[5]

In some parts of the United States, many people who were considered non-white were disenfranchised, barred from government office, and prevented from holding most government jobs well into the second half of the 20th century. Many U.S. states banned interracial marriage through anti-miscegenation laws until 1967, when these laws were declared unconstitutional. Additionally, white leaders often viewed Native Americans as obstacles to economic and political progress with respect to the natives' claims to land and rights.

White supremacy was also dominant in South Africa under apartheid and in parts of Europe at various time periods. Governments of many European-settled countries bordering the Pacific Ocean limited immigration and naturalization from the Asian Pacific countries, usually on a cultural basis. South Africa maintained its white supremacist apartheid system until 1994.[6][7]

Academic use of the term

The term white supremacy is used in academic studies of racial power to denote a system of structural racism which privileges white people over others, regardless of the presence or absence of racial hatred. Legal scholar Frances Lee Ansley explains this definition as follows:

- By "white supremacy" I do not mean to allude only to the self-conscious racism of white supremacist hate groups. I refer instead to a political, economic and cultural system in which whites overwhelmingly control power and material resources, conscious and unconscious ideas of white superiority and entitlement are widespread, and relations of white dominance and non-white subordination are daily reenacted across a broad array of institutions and social settings.[8][9]

This and similar definitions are adopted or proposed by Charles Mills,[10] bell hooks,[11] David Gillborn,[12] and Neely Fuller Jr.[13] Some anti-racist educators, such as Betita Martinez and the Challenging White Supremacy workshop, also use the term in this way. The term expresses historic continuities between a pre-Civil Rights era of open white supremacism and the current racial power structure of the United States. It also expresses the visceral impact of structural racism through "provocative and brutal" language that characterizes racism as "nefarious, global, systemic, and constant."[14] Academic users of this term sometimes prefer it to racism because it allows for a disconnection between racist feelings and white racial advantage or privilege.[15][16]

Ideologies and movements

Supporters of Nordicism consider the Nordic peoples to be a superior race considering all non-Nordic people, in particular Jews, Gypsies, black people, brown people, yellow people (Asians) and mixed race to be inferior of the master race. By the early-19th century white supremacy was attached to emerging theories of racial hierarchy. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer attributed civilisational primacy to the White race:

The highest civilization and culture, apart from the ancient Hindus and Egyptians, are found exclusively among the white races; and even with many dark peoples, the ruling caste or race is fairer in colour than the rest and has, therefore, evidently immigrated, for example, the Brahmans, the Incas, and the rulers of the South Sea Islands. All this is due to the fact that necessity is the mother of invention because those tribes that emigrated early to the north, and there gradually became white, had to develop all their intellectual powers and invent and perfect all the arts in their struggle with need, want and misery, which in their many forms were brought about by the climate.[17]

The eugenicist Madison Grant argued that the Nordic race had been responsible for most of humanity's great achievements, and that admixture was "race suicide".[18] In Grant's 1916 book, The Passing of the Great Race, Europeans who were not of Germanic origin, but who had Nordic characteristics such as blonde/red hair and blue/green/gray eyes were considered to be a Nordic admixture and suitable for Aryanization.[19]

In the United States, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) is the group most associated with the white supremacist movement. Many white supremacist groups are based on the concept of preserving genetic purity, and do not focus solely on discrimination by skin color.[20] The KKK's reasons for supporting racial segregation are not primarily based on religious ideals, but some Klan groups are openly Protestant. The KKK and other white supremacist groups like Aryan Nations, The Order and the White Patriot Party are considered Anti-Semitic.[20]

Nazi Germany promulgated white supremacy in the belief that the Aryan race was the master race. It was combined with a eugenics programme that aimed for racial hygiene by using compulsory sterilizations and extermination of the Untermensch (or "sub-humans"), and which eventually culminated in the Holocaust.

Christian Identity is another movement closely tied to white supremacy. Some white supremacists identify themselves as Odinists, although many Odinists reject white supremacy. Some white supremacist groups, such as the South African Boeremag, conflate elements of Christianity and Odinism. The World Church of the Creator (now called the Creativity Movement) is atheistic and denounces the Christian religion and other deistic religions.[21][22] Aside from this, its ideology is similar to many Christian Identity groups, in their belief that there is a Jewish conspiracy in control of governments, the banking industry and the media. Matthew F. Hale, founder of the World Church of the Creator has published articles stating that all races other than white are "mud races," which the religion teaches.[20]

The white supremacist ideology has become associated with a racist faction of the skinhead subculture, despite the fact that when the skinhead culture first developed in the United Kingdom in the late 1960s, it was heavily influenced by black fashions and music, especially Jamaican reggae and ska, and African American soul music[23][24][25] By the 1980s, a sizeable and vocal white power skinhead faction had formed.[citation needed]

White supremacist recruitment tactics are primarily on a grassroots level and on the Internet. Widespread access to the Internet has led to a dramatic increase in white supremacist websites.[26] The Internet provides a venue to openly express white supremacist ideas at little social cost, because people who post the information are able to remain anonymous.

Alliances with black supremacist groups

Due to some commonly held separatist ideologies, some white supremacist organizations have found limited common cause with black supremacist or extremist organizations.

In 1961 and 1962 George Lincoln Rockwell, the leader of the American Nazi Party, was invited to speak by Elijah Muhammad at a Nation of Islam rally. In 1965, after breaking with the Nation of Islam and denouncing its separatist doctrine, Malcolm X told his followers that the Nation of Islam under Elijah Muhammad had made agreements with the American Nazi Party and the Ku Klux Klan that "were not in the interests of Negros." In 1985 Louis Farrakhan invited white supremacist Tom Metzger, leader of the White Aryan Resistance (a neo-Nazi white power group), to attend a NOI gathering. The Washington Times reports Metzger's words of praise: "They speak out against the Jews and the oppressors in Washington.... They are the black counterpart to us."[citation needed]

See also

- Black supremacy

- Afrocentrism

- Eurocentrism

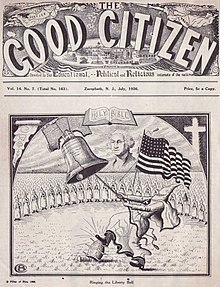

- The Good Citizen

- Hate Group

- Heroes of the Fiery Cross

- Institutional racism

- Scientific racism

- Jim Crow laws

- Master race

- Race and intelligence

- Racist music

- The White Man's Burden

Footnotes

- ^ Wildman, Stephanie M. (1996). Privilege Revealed: How Invisible Preference Undermines America. NYU Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-8147-9303-7.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Flint, Colin (2004). Spaces of Hate: Geographies of Discrimination and Intolerance in the U.S.A. Routledge. p. 53. ISBN 0-415-93586-5.

Although white racist activists must adopt a political identity of whiteness, the flimsy definition of whiteness in modern culture poses special challenges for them. In both mainstream and white supremacist discourse, to be white is to be distinct from those marked as nonwhite, yet the placement of the distinguishing line has varied significantly in different times and places.

- ^ Fredrickson, George (1981). White Supremacy. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. p. 162. ISBN 0-19-503042-7.

- ^ A Declaration of the Causes which Impel the State of Texas to Secede from the Federal Union: "We hold as undeniable truths that the governments of the various States, and of the confederacy itself, were established exclusively by the white race, for themselves and their posterity; that the African race had no agency in their establishment; that they were rightfully held and regarded as an inferior and dependent race, and in that condition only could their existence in this country be rendered beneficial or tolerable. That in this free government all white men are and of right ought to be entitled to equal civil and political rights; that the servitude of the African race, as existing in these States, is mutually beneficial to both bond and free, and is abundantly authorized and justified by the experience of mankind, and the revealed will of the Almighty Creator, as recognized by all Christian nations; while the destruction of the existing relations between the two races, as advocated by our sectional enemies, would bring inevitable calamities upon both and desolation upon the fifteen slave-holding states."

- ^ The "Cornerstone Speech", Alexander H. Stephens (Vice President of the Confederate States), March 21, 1861, Savannah, Georgia: "Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery--subordination to the superior race--is his natural and normal condition."

- ^ "abolition of the White Australia Policy". Australian Government. November 2010. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ "Encyclopaedia Britannia, South Africa the Apartheid Years". Encyclopaedia Britannia. Retrieved October 13, 2011.

- ^ Ansley, Francis Lee (1989). "Stirring the Ashes: Race, Class and the Future of Civil Rights Scholarship". Cornell Law Review. 74: 993ff.

- ^ Ansley, Francis Lee (1997-06-29). "White supremacy (and what we should do about it)". Critical white studies: Looking behind the mirror. Temple University Press. p. 592. ISBN 978-1-56639-532-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Mills, C.W. (2003). "White supremacy as sociopolitical system: A philosophical perspective". White out: The continuing significance of racism: 35–48.

- ^ Hooks, Bell (200). Feminist theory: From margin to center. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-1663-5.

- ^ Gillborn, David (2006-09-01). "Rethinking White Supremacy Who Counts in 'WhiteWorld'". Ethnicities. 6 (3): 318–340. doi:10.1177/1468796806068323. ISSN 1741-2706 1468-7968, 1741-2706. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

{{cite journal}}: Check|issn=value (help) - ^ Fuller, Neely (1984). The united-independent compensatory code/system/concept: A textbook/workbook for thought, speech, and/or action, for victims of racism (white supremacy). SAGE. p. 334. ASIN B0007BLCWC.

- ^ Davidson, Tim (2009-02-23). "bell hooks, white supremacy, and the academy". Critical perspectives on Bell Hooks. Taylor & Francis US. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-415-98980-0.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "Why is it so difficult for many white folks to understand that racism is oppressive not because white folks have prejudicial feelings about blacks (they could have such feelings and leave us alone) but because it is a system that promotes domination and subjugation?" hooks, bell (2009-02-04). Black Looks: Race and Representation. Turnaround Publisher Services Limited. p. 12. ISBN 978-1-873262-02-3.

- ^ Grillo and Wildman cite hooks to argue for the term racism/white supremacy: "hooks writes that liberal whites do not see themselves as prejudiced or interested in domination through coercion, and do not acknowledge the ways they the ways they contribute to and benefit from the system of white privilege." " Grillo, Trina (1997-06-29). "The implications of making comparisons between racism and sexism (or other isms)". Critical white studies: Looking behind the mirror. Temple University Press. p. 620. ISBN 978-1-56639-532-8.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Schopenhauer, Arthur (1851). Parerga and Paralipomena. Vol. 2, Section 92.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|nopp=ignored (|no-pp=suggested) (help) - ^ Grant, Madison (1921). The Passing of the Great Race (4 ed.). C. Scribner's sons. p. xxxi.

- ^ Grant, Madison (1916). The Passing of the Great Race. Charles Scribner's Sons, New York.

- ^ a b c http://law.jrank.org/pages/11302/White-Supremacy-Groups.html White Supremacy Groups

- ^ The new white nationalism in America: its challenge to integration. Cambridge University Press. Retrieved 2011–03–27.

For instance, Ben Klassen, founder of the atheistic World Church of the Creator and the author of The White Man's Bible, discusses Christianity extensively in his writings and denounces religion that has brought untold horror into the world and divided the white race.

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ The World's Religions: Continuities and Transformations. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved 2011–03–27.

A competing atheistic or panthestic white racist movement also appeared, which included the Church of the Creator/ Creativity (Gardell 2003: 129–134).

{{cite book}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) - ^ Smiling Smash: An Interview with Cathal Smyth, a.k.a. Chas Smash, of Madness.

- ^ Special Articles.

- ^ Old Skool Jim. Trojan Skinhead Reggae Box Set liner notes. London: Trojan Records. TJETD169.

- ^ Adams, Josh, and Vincent J. Roscigno "White Supremacists, Oppositional Culture and the World Wide Web." University on North Carolina Press 84 (2005): 759-788. JSTOR. Web. 20 Nov. 2009. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/3598477>.

Further reading

- Dobratz, Betty A. and Shanks-Meile, Stephanie. "White power, white pride!": The white separatist movement in the United States (JHU Press, 2000) ISBN 978-0-8018-6537-4

- Lincoln Rockwell, George. White Power (John McLaughlin, 1996)

- MacCann, Ronnarae. White Supremacy in Children's Literature (Routledge, 2000)

External links

- Heart of Whiteness documentary film about what it means to be white in South Africa

- Voices on Antisemitism Interview with Frank Meeink from the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum