Vagina

| Vagina | |

|---|---|

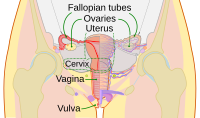

Diagram of the female human reproductive tract and ovaries | |

Vulva with vaginal opening 1: Clitoral hood | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | urogenital sinus and paramesonephric ducts |

| Artery | superior part to uterine artery, middle and inferior parts to vaginal artery |

| Vein | uterovaginal venous plexus, vaginal vein |

| Nerve | Sympathetic: lumbar splanchnic plexus Parasympathetic: pelvic splanchnic plexus |

| Lymph | upper part to internal iliac lymph nodes, lower part to superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Vagina |

| MeSH | D014621 |

| TA98 | A09.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 3523 |

| FMA | 19949 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The vagina is a fibromuscular tubular sex organ that is part of the female genital tract. In humans, the vagina extends from the vulva to the uterus. At the vulva, the vaginal orifice may be partly covered by a membrane called the hymen, while, at the deep end, the cervix (neck of the uterus) bulges through the anterior wall of the vagina. The vagina facilitates sexual intercourse and childbirth. It also channels the menstrual flow, consisting of blood and pieces of mucosal tissue, that occurs periodically with the shedding of lining of the uterus in menstrual cycles.

The location and structure of the vagina varies among species, and may vary in size within the same species. Unlike mammalian males, who usually have the urethral orifice as the sole external urogenital orifice, mammalian females usually have two external orifices, the urethral orifice for the urological tract and the vaginal orifice for the genital tract. The vaginal orifice is much larger than the nearby urethral opening, and both openings are protected by the labia in humans.[1] In amphibians, birds, reptiles and monotremes, an opening called the cloaca functions as a single external orifice for the gastrointestinal tract, urological tract, and reproductive tract.

The vagina plays a significant role in human female sexuality and sexual pleasure. During sexual arousal for humans and other animals, vaginal moisture increases by way of vaginal lubrication, to reduce friction and allow for smoother penetration of the vagina during sexual activity. The texture of the vaginal walls can create friction for the penis during sexual intercourse and stimulate it toward ejaculation, enabling fertilization.[2] In addition, a variety of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and other disorders can affect the vagina. Because of the risk of STIs, health authorities, such as the World Health Organization (WHO), and health care providers, recommend safe sex practices.[3][4][5]

Cultural perceptions of the vagina have persisted throughout history, ranging from viewing the vagina as the focus of sexual desire, a metaphor for life via birth, inferior to the penis, or as visually unappealing or otherwise vulgar. Colloquially, the word vagina is often used incorrectly[dubious – discuss] to refer to the vulva.

Etymology and definition

The term vagina is from Latin vāgīnae, literally "sheath" or "scabbard"; the Latinate plural of vagina is vaginae,[6] and the vagina may be referred to as the birth canal in the context of pregnancy and childbirth.[7][8] Although by its dictionary and anatomical definitions, the term vagina refers exclusively to the specific internal structure, it is colloquially used to refer to the vulva or to both the vagina and vulva.[9][10] Using the term vagina to mean "vulva" can pose medical or legal confusion; for example, a person's interpretation of its location not matching another person's interpretation of the location.[9] Medically, the vagina is the muscular canal between the hymen (or remnants of the hymen) and the cervix, while, legally, it begins at the vulva (between the labia).[9]

Structure

Development

A precursor to the inferior portion of the vagina, called the vaginal plate, is the growth of tissue that gives rise to the formation of the vagina; it is located where the solid tips of the paramesonephric ducts (Müllerian ducts) enter the dorsal wall of the urogenital sinus as the Müllerian tubercle. The plate's growth is unrestrained, as it significantly separates the cervix and the urogenital sinus; eventually, the central cells of the plate break down to form the vaginal lumen.[11] Until twenty to twenty-four weeks of pregnancy, the vagina is not fully canalized. If it fails to fully canalize, this may result in various forms of septae, which cause obstruction of the outflow tract later in life.[11]

In the absence of testosterone during sexual differentiation (sex development of the differences between males and females), the urogenital sinus persists as the vestibule of the vagina, the two urogenital folds (elongated spindle-shaped structures that contribute to the formation of the urethral groove on the belly aspect of the genital tubercle) form the labia minora, and the labioscrotal swellings enlarge to form the labia majora.[12][13]

The human vagina develops into an elastic muscular canal that extends from the vulva to the uterus.[14][15] It, along with the inside of the vulva, is reddish pink in color, and it connects the superficial vulva to the cervix of the deep uterus. The vagina is posterior to the urethra and bladder, and reaches across the perineum superiorly and posteriorly toward the cervix; at approximately a 90 degree angle, the cervix protrudes into the vagina.[16]

There exists debate as to which portion of the vagina is formed from the Müllerian ducts and which from the urogenital sinus by the growth of the sinovaginal bulb.[11][17] Dewhurst's Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology states, "Some believe that the upper four-fifths of the vagina is formed by the Müllerian duct and the lower fifth by the urogenital sinus, while others believe that sinus upgrowth extends to the cervix displacing the Müllerian component completely and the vagina is thus derived wholly from the endoderm of the urogenital sinus." It adds, "It seems certain that some of the vagina is derived from the urogenital sinus, but it has not been determined whether or not the Müllerian component is involved."[11]

Layers, regions and histology

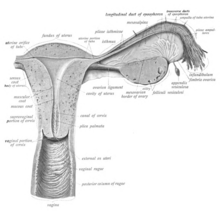

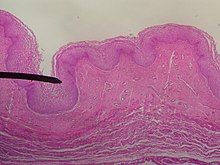

The wall of the vagina from the lumen outwards consists firstly of a mucosa of non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium with an underlying lamina propria of connective tissue, secondly a layer of smooth muscle with bundles of circular fibers internal to longitudinal fibers, and thirdly an outer layer of connective tissue called the adventitia. Some texts list four layers by counting the two sublayers of the mucosa (epithelium and lamina propria) separately.[18][19] The lamina propria is rich in blood vessels and lymphatic channels. The muscular layer is composed of smooth muscle fibers, with an outer layer of longitudinal muscle, an inner layer of circular muscle, and oblique muscle fibers between. The outer layer, the adventitia, is a thin dense layer of connective tissue, and it blends with loose connective tissue containing blood vessels, lymphatic vessels and nerve fibers that is present between the pelvic organs.[16][19][20]

The mucosa forms folds or rugae, which are more prominent in the caudal third of the vagina; they appear as transverse ridges and their function is to provide the vagina with increased surface area for extension and stretching. Where the vaginal lumen surrounds the cervix of the uterus, it is divided into four continuous regions or vaginal fornices; these are the anterior, posterior, right lateral, and left lateral fornices.[14][15] The posterior fornix is deeper than the anterior fornix.[15] While the anterior and posterior walls are placed together, the lateral walls, especially their middle area, are relatively more rigid; because of this, they vagina has a H-shaped cross section.[15] Behind, the upper one-fourth of the vagina is separated from the rectum by the recto-uterine pouch. Superficially, in front of the pubic bone, a cushion of fat called the mons pubis forms the uppermost part of the vulva.

Supporting the vagina are its upper third, middle third and lower third muscles and ligaments. The upper third are the levator ani muscles (transcervical, pubocervical) and the sacrocervical ligaments; these areas are also described as the cardinal ligaments laterally and uterosacral ligaments posterolaterally. The middle third of the vagina concerns the urogenital diaphragm (also described as the paracolpos and pelvic diaphragm). The lower third is the perineal body; it may be described as containing the perineal body, pelvic diaphragm and urogenital diaphragm.[14][21]

The epithelial covering of the cervix is continuous with the epithelial lining of the vagina. The vaginal mucosa is absent of glands. The vaginal epithelium consists of three rather arbitrary layers of cells[22] – superficial flat cells, intermediate cells and basal cells – and estrogen induces the intermediate and superficial cells to fill with glycogen. The superficial cells exfoliate continuously and basal cells replace them.[15][23][24] Under the influence of maternal estrogen, newborn females have a thick stratified squamous epithelium for two to four weeks after birth. After that, the epithelium remains thin with only a few layers of cells without glycogen until puberty, when the epithelium thickens and glycogen containing cells are formed again, under the influence of the girl's rising estrogen levels. Finally, the epithelium thins out during menopause onward and eventually ceases to contain glycogen, because of the lack of estrogen.[15][24][25] In abnormal circumstances, such as in pelvic organ prolapse, the vaginal epithelium may be exposed becoming dry and keratinized.[26]

For blood and nerve supply, relevant arteries are the cervicovaginal (the uterine cervix and the vagina) branch of the uterine artery, the vaginal artery, middle rectal artery, and the internal pudendal artery. The veins are connected by anastomosis (the connection of separate parts of a branching system to form a network), resulting in the formation of the anterior and posterior azygos (unpaired) arteries. The nerve supply of the vagina is provided by the sympathetic and parasympathetic areas of the pelvic plexus, with the pudendal nerve supplying the lower area.[15]

Vaginal opening and hymen

The vaginal opening (or orifice) is at the caudal end of the vulva, behind the opening of the urethra, resting at the posterior end of the vestibule. It is closed by the labia minora in female virgins and in females who have never given birth (nulliparae), but may be exposed in females who have given birth (parous females).[15]

The hymen is a membrane of tissue that surrounds or partially covers the vaginal opening.[15] The effects of vaginal intercourse and childbirth on the hymen are variable. If the hymen is sufficiently elastic, it may return to nearly its original condition. In other cases, there may be remnants (carunculae myrtiformes), or it may appear completely absent after repeated penetration.[2][27] Additionally, the hymen may be lacerated by disease, injury, medical examination, masturbation or physical exercise. For these reasons, it is not possible to definitively determine whether or not a girl or woman is a virgin by examining her hymen.[2][27][28]

Variations and size

In its normal state, there is anatomical variation in the length of the vagina of a woman of child-bearing age. The length is approximately 7.5 cm (2.5 to 3 in) across the anterior wall (front), and 9 cm (3.5 in) long across the posterior wall (rear), making the posterior fornix deeper than the anterior.[15][20] During sexual arousal, the vagina expands in both length and width.

If a woman stands upright, the vaginal tube points in an upward-backward direction and forms an angle of approximately 45 degrees with the uterus and of about 60 degrees to the horizontal.[15][21]

The vaginal opening and hymen can vary in size; in children, although a common appearance of the hymen is crescent-shaped, many shapes are possible.[15][29]

Function

Secretions

The vagina provides a path for menstrual blood and tissue to leave the body. In industrial societies, tampons, menstrual cups and sanitary napkins may be used to absorb or capture these fluids. Vaginal secretions are primarily from the uterus, cervix, and transudation of the vaginal epithelium in addition to miniscule vaginal lubrication from the Bartholin's glands upon sexual arousal. It takes little vaginal secretion to make the vagina moist. The secretions may be minor in excess during sexual arousal, the middle of the menstrual cycle, a little prior to menstruation, or during pregnancy.[15]

The Bartholin's glands, located near the vaginal opening and cervix, were originally thought to be the primary source for vaginal lubrication, but they provide only a few drops of mucus for vaginal lubrication;[30] the significant majority of vaginal lubrication is generally believed to be provided by plasma seepage from the vaginal walls, which is called vaginal transudation. Vaginal transudation, which initially forms as sweat-like droplets, is caused by vascular engorgement of the vagina (vasocongestion); this results in the pressure inside the capillaries increasing the transudation of plasma through the vaginal epithelium.[30][31][32]

Before and during ovulation, the cervix's mucus glands secrete different variations of mucus, which provides an alkaline, fertile environment in the vaginal canal that is favorable to the survival of sperm.[33] As women age, vaginal lubrication decreases, which does not necessarily mean that a physical or psychological problem exists.[34] After menopause, the body produces less estrogen, which, unless compensated for with estrogen replacement therapy, causes the vaginal walls to thin out significantly.[15][24][35]

Sexual activity

The concentration of the nerve endings that lie close to the entrance of the vagina (the lower third) usually provide pleasurable vaginal sensations when stimulated during sexual activity, and many women additionally derive pleasure from a feeling of closeness and fullness during penetration of the vagina.[36][37] The vagina as a whole, however, lacks nerve endings, which commonly hinders a woman's ability to receive sufficient sexual stimulation, including orgasm, solely from penetration of the vagina.[36][37][38] Although some scientific examinations of vaginal wall innervation indicate no single area with a greater density of nerve endings, or that only some women have a greater density of nerve endings in the anterior vaginal wall,[39][40] heightened sensitivity in the anterior vaginal wall is common among women.[39][41] These cases indicate that the outer one-third of the vagina, especially near the opening, contains the majority of the vaginal nerve endings, making it more sensitive to touch than the inner (or upper) two-thirds of the vaginal barrel.[36][38][42] This factor is considered to make the process of child birth significantly less painful, because an increased number of nerve endings means that there is an increased possibility for pain as well as pleasure.[36][43][44]

Besides penile penetration, there are a variety of ways that pleasure can be received from vaginal stimulation, including by masturbation, fingering, oral sex (cunnilingus), or by specific sex positions (such as the missionary position or the spoons sex position).[45] Some women use sex toys, such as a vibrator or dildo, for vaginal pleasure.[46] Foreplay is often used to incite sexual arousal, and may include one or more of the aforementioned sexual activities. The clitoris additionally plays a part in vaginal stimulation, as it is a sex organ of multiplanar structure containing an abundance of nerve endings, with a broad attachment to the pubic arch and extensive supporting tissue to the mons pubis and labia; it is centrally attached to the urethra, and research indicates that it forms a tissue cluster with the vagina. This tissue is perhaps more extensive in some women than in others, which may contribute to orgasms experienced vaginally.[38][47][48]

During sexual arousal, and particularly the stimulation of the clitoris, the walls of the vagina lubricate. This begins after ten to thirty seconds of sexual arousal, and increases in amount the longer the woman is aroused.[49] It reduces friction or injury that can be caused by insertion of the penis into the vagina or other penetration of the vagina during sexual activity.[2] The vagina lengthens during the arousal, and can continue to lengthen in response to pressure; as the woman becomes fully aroused, the vagina expands in length and width, while the cervix retracts.[49][50] With the upper two-thirds of the vagina expanding and lengthening, the uterus rises into the greater pelvis, and the cervix is elevated above the vaginal floor, resulting in "tenting" of the mid-vaginal plane.[49] As the elastic walls of the vagina stretch or contract, with support from the pelvic muscles, to wrap around the inserted penis (or other object),[2][42] this stimulates the penis and helps to cause the male to experience orgasm and ejaculation, which in turn enables fertilization.[2]

An area in the vagina that may be an erogenous zone is the G-spot (also known as the Gräfenberg spot); it is typically defined as being located at the anterior wall of the vagina, a couple or few inches in from the entrance, and some women experience intense pleasure, and sometimes an orgasm, if this area is stimulated during sexual activity.[39][41] A G-spot orgasm may be responsible for female ejaculation, leading some doctors and researchers to believe that G-spot pleasure comes from the Skene's glands, a female homologue of the prostate, rather than any particular spot on the vaginal wall. Other researchers consider the connection between the Skene's glands and the G-spot area to be weak; they contend that the Skene's glands do not appear to have receptors for touch stimulation, and that there is no direct evidence for their involvement.[39][40][41] The G-spot's existence, and existence as a distinct structure, is still under dispute, as its reported location can vary from woman to woman, appears to be nonexistent in some women, and it is hypothesized to be an extension of the clitoris and therefore the reason for orgasms experienced vaginally.[39][43][48]

Childbirth

The vagina provides a channel to deliver a newborn from the uterus to its independent life outside the body of the mother. When childbirth (or labor) nears, several symptoms may occur, including Braxton Hicks contractions, vaginal discharge, and the rupture of membranes (water breaking).[51] When water breaking happens, there may be an uncommon wet sensation in the vagina that is an irregular or steady small stream of fluid from the vagina, or a gush of fluid.[52][53]

When the body prepares for childbirth, the cervix softens, thins, moves forward to face anteriorly, and may begin to open. This allows the fetus to settle or "drop" into the pelvis.[51] When the fetus settles into the pelvis, this may result in pain in the sciatic nerves, increased vaginal discharge, and increased urinary frequency. While, for women who have given birth before, these symptoms are likelier to happen after labor has already begun, they may happen approximately ten to fourteen days before labor in women experiencing the effects of nearing labor for the first time.[51]

The fetus begins to lose the support of the cervix when uterine contractions begin. With cervical dilation reaching a diameter of more than 10 cm (4 in) to accommodate the head of the fetus, the head moves from the uterus to the vagina.[51] The elasticity of the vagina allows it to stretch to many times its normal diameter in order to deliver the child.[20]

Births are usually successful vaginal births, but there are sometimes complications and a woman may undergo a caesarean section instead of a vaginal delivery. The vaginal mucosa has an abnormal accumulation of fluid (edematous) and is thin, with few rugae, a little after birth. The mucosa thickens and rugae return in approximately three weeks once the ovaries regain usual function and estrogen flow is restored. The vaginal opening gapes and is relaxed, until it returns to its approximate pre-pregnant state by six to eight weeks in the period beginning immediately after the birth (the postpartum period); however, it will maintain a larger shape than it previously had.[54]

Vaginal ecosystem and acidity

The vagina is a nutrient rich environment that harbors a unique and complex microbiome. It is a dynamic ecosystem that undergoes long-term changes, from neonate to puberty and from the reproductive period (menarche) to menopause. Moreover, under the influence of hormones, such as estrogen (estradiol), progesterone and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), the vaginal ecosystem undergoes cyclic or periodic changes, i.e. during menses and pregnancy.[55] One significant variable parameter is the vaginal pH, which varies significantly during a woman's lifespan, from 7.0 in premenarchal girls, to 3.8-4.4 in women of reproductive age to 6.5-7.0 during menopause without hormone therapy and 4.5-5.0 with hormone replacement therapy.[56] Estrogen, glycogen and lactobacilli are important factors in this variation.[55][56]

Clinical significance

General

The vagina is self-cleansing and therefore usually needs no special treatment. To maintain vulvovaginal health, doctors generally discourage the practice of douching.[57] Since a healthy vagina is colonized by a mutually symbiotic flora of microorganisms that protect its host from disease-causing microbes, any attempt to upset this balance may cause many undesirable outcomes, including but not limited to abnormal discharge and yeast infection.[57]

The vagina and cervix are examined during gynecological examinations of the pelvis, often using a speculum, which holds the vagina open for visual inspection or taking samples (see pap smear).[58] This and other medical procedures involving the vagina, including digital internal examinations and administration of medicine,[58][59] are referred to as being "per vaginam", the Latin for "via the vagina",[60] often abbreviated to "p.v.".[59]

The healthy vagina of a woman of child-bearing age is acidic, with a pH normally ranging between 3.8 and 4.5., and this is due to the degradation of glycogen to the lactic acid by enzymes secreted by the Döderlein's bacillus, which is a normal commensal of the vagina.[55] The acidity retards the growth of many strains of pathogenic microbes.[55] An increased pH of the vagina (with a commonly used cut-off of pH 4.5 or higher) can be caused by bacterial overgrowth, as occurs in bacterial vaginosis and trichomoniasis, or rupture of membranes in pregnancy.[55][61]

Intravaginal administration is a route of administration where the substance is applied to the inside of the vagina. Pharmacologically, it has the potential advantage to result in effects primarily in the vagina or nearby structures (such as the vaginal portion of cervix) with limited systemic adverse effects compared to other routes of administration.[62][63]

Infections and disorders

There are many infections, diseases and disorders that can affect the vagina, including candidal vulvovaginitis, vaginitis, vaginismus, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or cancer. Vaginitis is an inflammation of the vagina, and is attributed to several vaginal diseases, while vaginismus is an involuntary tightening of the vagina muscles caused by a conditioned reflex, or disease, during vaginal penetration.[64] HIV/AIDS, human papillomavirus (HPV), genital herpes and trichomoniasis are some of the STIs that may affect the vagina, and health authorities and health care providers recommend safe sex practices when engaging in sexual activity to prevent STIs.[3][4] Cervical cancer may be prevented by pap smear screening and HPV vaccines. Vaginal cancer is very rare, and is primarily a matter of old age; its symptoms include abnormal vaginal bleeding or vaginal discharge.[65][66]

There can be a vaginal obstruction, such as a imperforate hymen or, less commonly, a transverse vaginal septum, affecting the vagina. Where a lump is present, it is most commonly a Bartholin's cyst.[67] Vaginal prolapse is characterized by a portion of the vaginal canal protruding (prolapsing) from the opening of the vagina. It may result in the case of weakened pelvic muscles, which is a common result of childbirth; in the case of this prolapse, the rectum, uterus, or bladder pushes on the vagina, and severe cases result in the vagina protruding out of the body. Kegel exercises have been used to strengthen the pelvic floor, and may help prevent or remedy vaginal prolapse.[68]

Modification

The vagina, including the vaginal opening, may be altered as a result of genital modification during vaginoplasty or labiaplasty; for example, alteration to the inner labia (also known as the vaginal lips or labia minora). There is no evidence that such surgery improves psychological or relationship problems; however, the surgery has a risk of damaging blood vessels and nerves.[69]

Female genital mutilation (FGM), another aspect of female genital modification, may additionally be known as female circumcision or female genital cutting (FGC).[70][71] FGM has no known health benefits. The most severe form of FGM is infibulation, in which there is removal of all or part of the inner and outer labia (labia minora and labia majora) and the closure of the vagina; this is called Type III FGM, and it involves a small hole being left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, with the vagina being opened up for sexual intercourse and childbirth.[71]

Society and culture

Biological perceptions, symbolism and vulgarity

There have been various perceptions of the vagina throughout history, including that it is the center of sexual desire, a metaphor for life via birth, inferior to the penis, visually unappealing, inherently "smelly," or otherwise vulgar.[72][73][74] These views can largely be attributed to sex differences, and how they are interpreted. David Buss, an evolutionary psychologist, stated that because a penis is significantly larger than a clitoris and it is "on display and ready to be noticed" while the vagina is not, and males urinate through the penis, boys are taught from childhood "to touch and hold their penises" while girls are often taught that they should not touch their own genitals, "as if their genitals were a biohazard zone." Buss attributed this to the reason why many women are not as familiar with their genitalia as men are familiar with their own, and that researchers assume these sex differences explain why boys learn to masturbate before girls, and masturbate more often than girls.[75]

The word vagina is commonly avoided in conversation,[76] and many men in addition to women do not know that the vagina is not used for urination.[77][78][79] This is exacerbated by the phrase "Boys have a penis, girls have a vagina.", which causes children to think that girls have one orifice in the pelvic area.[78] Author Hilda Hutcherson stated, "Because many of us [women] have been conditioned since childhood through verbal and nonverbal cues to think of our genitals as ugly, smelly and unclean, we aren't able to fully enjoy intimate encounters because of fear that our partner will be turned off by the sight, smell, and taste of our genitals." She added that women, unlike men, did not have locker room experiences in school where they compared each other's genitals, and so many women wonder if their genitals are normal.[73] Scholar Catherine Blackledge stated that having a vagina meant she would typically be treated less well than a "vagina-less person" and that she "could be expected to work all [her] life for less money than if [she] was minus female genitalia"; it meant she "could expect to be treated as a second-class citizen".[76]

Negative views of the vagina are simultaneously contrasted by views that it is a powerful symbol of female sexuality, spirituality, or life. Author Denise Linn stated, "[The vagina] is a powerful symbol of womanliness, openness, acceptance, and receptivity. It is the inner valley spirit."[80] Sigmund Freud placed significant value on the vagina,[81] postulating the concept of vaginal orgasm, that it is separate from clitoral orgasm, and that, upon reaching puberty, the proper response of mature women is a change-over to vaginal orgasms (meaning orgasms without any clitoral stimulation). This theory, however, made many women feel inadequate, as the majority of women cannot achieve orgasm via vaginal intercourse alone.[82][83][84] Regarding religion, the vagina represents a powerful symbol as the yoni in Hindu, and this may indicate the value that Hindu society has given female sexuality and the vagina's ability to birth life.[85]

In Ancient times, the vagina was often considered equivalent (homologous) to the penis; anatomists Galen (129 AD – 200 AD) and Vesalius (1514–1564), regarded the organs as structurally the same, except for the vagina being inverted. Anatomical studies over latter centuries, however, showed the clitoris to be the penile equivalent.[47][86] The release of vaginal fluids were considered by medical practitioners to cure or remedy a number of ailments; various methods were used over the centuries to release "female seed" (via vaginal lubrication or female ejaculation) as a treatment for suffocation ex semine retento (suffocation of the womb), female hysteria or green sickness. Methods included a midwife rubbing the walls of the vagina or insertion of the penis or penis-shaped objects into the vagina. Supposed symptoms of female hysteria included faintness, nervousness, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in abdomen, muscle spasm, shortness of breath, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, and "a tendency to cause trouble".[87] Women considered suffering from the condition would sometimes undergo "pelvic massage" — stimulation of the genitals by the doctor until the woman experienced "hysterical paroxysm" (i.e., orgasm). Paroxysm was regarded as a medical treatment, and not a sexual release.[87] The categorization of female hysteria has ceased to be recognized as a medical condition since the 1920s.

The vagina has additionally been termed many vulgar names,[88] two being cunt and pussy. Cunt is used as a derogatory epithet referring to people of either sex. This usage is relatively recent, dating from the late nineteenth century.[89] Reflecting different national usages, cunt is described as "an unpleasant or stupid person" in the Compact Oxford English Dictionary, whereas Merriam-Webster has a usage of the term as "usually disparaging and obscene: woman",[90] noting that it is used in the U.S. as "an offensive way to refer to a woman";[91] and the Macquarie Dictionary of Australian English states that it is "a despicable man". When used with a positive qualifier (good, funny, clever, etc.) in Britain, New Zealand and Australia, it can convey a positive sense of the object or person referred to.[92] Pussy, on the other hand, can indicate "cowardice or weakness", and "the human vulva or vagina" or by extension "sexual intercourse with a woman".[93]

In contemporary art and literature

The Vagina Monologues, a 1996 episodic play by Eve Ensler, has been noted for its success in making female sexuality a topic of public discourse. It is made up of a varying number of monologues read by a number of women. Initially, Ensler performed every monologue herself, with subsequent performances featuring three actresses; latter versions feature a different actress for every role. Each of the monologues deals with an aspect of the feminine experience, touching on matters such as sexual activity, love, rape, menstruation, female genital mutilation, masturbation, birth, orgasm, the various common names for the vagina, or simply as a physical aspect of the body. A recurring theme throughout the pieces is the vagina as a tool of female empowerment, and the ultimate embodiment of individuality.[88][94]

In Japan, artist Megumi Igarashi has drawn attention for her work featuring vaginas, which she considers "overly hidden" in Japan compared to male genitalia.[95]

Reasons for vaginal modification

Reasons for modification of the external female genitalia includes voluntary cosmetic operations and surgery for intersex conditions, which can involve surgery to the vagina, labia minora, or clitoris.[69] It also includes FGM.[96] There are two main categories of women seeking cosmetic genital surgery: those with congenital conditions such as an intersex condition, and those with no underlying condition who experience physical discomfort or wish to alter the appearance of their genitals because they believe they do not fall within a normal range.[69]

Significant controversy surrounds FGM,[70][71] with the World Health Organization (WHO) being one of many health organizations that have campaigned against the procedures on behalf of human rights, stating that it is "a violation of the human rights of girls and women" and "reflects deep-rooted inequality between the sexes".[71] FGM has existed at one point or another in almost all human civilizations,[96] most commonly to exert control over the sexual behavior, including masturbation, of girls and women.[71][96] It is carried out in several countries, especially in Africa, and to a lesser extent in other parts of the Middle East and Southeast Asia, on girls from a few days old to mid-adolescent, often to reduce sexual desire in an effort to preserve vaginal virginity.[70][71][96] It may also be that FGM was "practiced in ancient Egypt as a sign of distinction among the aristocracy"; there are reports that traces of infibulation are on Egyptian mummies.[96]

Custom and tradition are the most frequently cited reasons for FGM, with some cultures believing that not performing it has the possibility of disrupting the cohesiveness of their social and political systems, such as FGM also being a part of a girl's initiation into adulthood.[71][96] Often, a girl is not considered an adult in a FGM-practicing society unless she has undergone FGM.[71]

Other animals

The vagina is a general feature of animals in which the female is internally fertilized (other than by traumatic insemination). The shape of the vagina varies among different animals.

In placental mammals and marsupials, the vagina leads from the uterus to the exterior of the female body. Female marsupials have two lateral vaginas, which lead to separate uteri, but both open externally through the same orifice.[97] The urethra and vagina of the female spotted hyena exits through the clitoris, allowing the females to urinate, copulate and give birth through the clitoris.[98] The canine female vagina contracts during copulation, forming a copulatory tie.[99]

In birds, monotremes, and some reptiles, a homologous part of the oviduct leads from the shell gland to the cloaca.[100][101] In some jawless fish, there is neither oviduct nor vagina and instead the egg travels directly through the body cavity (and is fertilised externally as in most fish and amphibians). In insects and other invertebrates, the vagina can be a part of the oviduct (see insect reproductive system).[102] Females of some waterfowl species have developed vaginal structures called dead end sacs and clockwise coils to protect themselves from sexual coercion.[103]

In 2014, the scientific journal Current Biology reported that four species of Brazilian insects in the genus Neotrogla were found to have sex-reversed genitalia. The male insects of those species have vagina-like openings, while the females have penis-like organs.[104][105][106]

See also

References

- ^ Kinetics, Human (15 May 2009). Health and Wellness for Life. Human Kinetics 10%. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-7360-6850-5. Retrieved 30 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Encyclopedia of Family Health. Marshall Cavendish. 2004. p. 964. ISBN 0761474862. Retrieved 25 April 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) Cite error: The named reference "Jacoby" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ a b Dianne Hales (2008). An Invitation to Health Brief 2010-2011. Cengage Learning. pp. 269–271. ISBN 0495391921. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ a b New Dimensions in Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2011. p. 211. ISBN 1449683754. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ "Global strategy for the prevention and control of sexually transmitted infections: 2006–2015. Breaking the chain of transmission" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2011.

- ^ Angus Stevenson (2010). Oxford Dictionary of English. Oxford University Press. p. 1962. ISBN 0199571120. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Health in the New Millennium: The Smart Electronic Edition (S.E.E.). Macmillan. 1998. p. 297. ISBN 1572591714. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Martin S. Lipsky (2006). American Medical Association Concise Medical Encyclopedia. Random House Reference. p. 96. ISBN 0375721800. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Maureen Dalton (2014). Forensic Gynaecology. Cambridge University Press. p. 65. ISBN 1107064295. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Health Humanities Reader. Rutgers University Press. 2014. pp. 231–232. ISBN 081357367X. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Keith Edmonds (2012). Dewhurst's Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 423. ISBN 0470654570. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ^ Merz, Eberhard; Bahlmann, F. (2004). Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. Vol. 1. Thieme Medical Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-58890-147-7.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Schuenke, Michael; Schulte, Erik; Schumacher, Udo (2010). General Anatomy and Musculoskeletal System. Thieme Medical Publishers. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-60406-287-8. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b c Snell, Richard S. (2004). Clinical Anatomy: An Illustrated Review with Questions and Explanations. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-7817-4316-7. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n DC Dutta (2014). DC Dutta's Textbook of Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. pp. 2–7. ISBN 9351520684. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b Mulhall, John P. (2011). Cancer and Sexual Health. Springer. pp. 13, 20–21. ISBN 1-60761-915-6. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ Cai Y (2009). "Revisiting old vaginal topics: conversion of the Müllerian vagina and origin of the "sinus" vagina". Int J Dev Biol 2009; 53:925-34. 53 (7): 925–34. doi:10.1387/ijdb.082846yc. PMID 19598112.

- ^ Brown, Laurence (2012). Pathology of the Vulva and Vagina. Springer Science+Business Media. pp. 6–7. ISBN 0857297570. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ^ a b Oxford Desk Reference: Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Oxford University Press. 2011. p. 471. ISBN 0191620874. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c Wylie, Linda (2005). Essential Anatomy and Physiology in Maternity Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 157–158. ISBN 0-443-10041-1. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b Manual of Obstetrics. (3rd ed.). Elsevier. 2011. pp. 1–16. ISBN 9788131225561.

- ^ Kurman, R. J, ed. (2002). Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract (5th ed.). Spinger. p. 154.

- ^ Stanley J. Robboy (2009). Robboy's Pathology of the Female Reproductive Tract. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 112. ISBN 0443074771. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ a b c Charles R. B. Beckmann (2010). Obstetrics and Gynecology. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 241–245. ISBN 0781788072. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ Shayne Cox Gad (2008). Pharmaceutical Manufacturing Handbook: Production and Processes. John Wiley & Sons. p. 817. ISBN 0470259809. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- ^ DC Dutta (2014). DC Dutta's Textbook of Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. p. 206. ISBN 9351520684. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b Knight, Bernard (1997). Simpson's Forensic Medicine (11th ed.). London: Arnold. p. 114. ISBN 0-7131-4452-1.

- ^ Perlman, Sally E. (2004). Clinical protocols in pediatric and adolescent gynecology. Parthenon. p. 131. ISBN 1-84214-199-6.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Emans, S. Jean. "Physical Examination of the Child and Adolescent" (2000) in Evaluation of the Sexually Abused Child: A Medical Textbook and Photographic Atlas, Second edition, Oxford University Press. 61-65

- ^ a b Sloane, Ethel (2002). Biology of Women. Cengage Learning. pp. 32, 41–42. ISBN 0-7668-1142-5. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Bourcier, A.; McGuire, Edward J.; Abrams, Paul (2004). Pelvic Floor Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 20. ISBN 0-7216-9194-3. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Wiederman, Michael W.; Whitley, Jr., Bernard E. (2012). Handbook for Conducting Research on Human Sexuality. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-135-66340-7. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Michael Cummings (2006). Human Heredity: Principles and Issues, Updated Edition. Cengage Learning. pp. 153–154. ISBN 0495113085. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ Clinical Neurology of the Older Adult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008. pp. 230–232. ISBN 0781769477. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Philip J. Di Saia (2012). Clinical Gynecologic Oncology. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 140. ISBN 0323074197. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ a b c d Weiten, Wayne; Dunn, Dana; Hammer, Elizabeth (1 January 2011). Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. p. 386. ISBN 1-111-18663-4. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ a b Martha Tara Lee (2013). Love, Sex and Everything in Between. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. p. 76. ISBN 9814516783. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

- ^ a b c Sex and Society, Volume 2. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2009. p. 590. ISBN 9780761479079. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2014. pp. 102–104. ISBN 1449648517. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Hines T (August 2001). "The G-Spot: A modern gynecologic myth". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 185 (2): 359–62. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.115995. PMID 11518892.

- ^ a b c Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2014. pp. 229–231. ISBN 1135825092. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2010. p. 126. ISBN 9814516783. Retrieved 27 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Clinical Manual of Sexual Disorders. American Psychiatric Pub. 2009. p. 258. ISBN 1585629057. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Rosenthal, Martha (6 January 2012). Human Sexuality: From Cells to Society. Cengage Learning. p. 76. ISBN 0-618-75571-3. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ^ Carroll, Janell (2012). Discovery Series: Human Sexuality. Cengage Learning. pp. 282–289. ISBN 1111841896. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Taormino, Tristan (2009). The Big Book of Sex Toys. Quiver. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-59233-355-4. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM (October 2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Kilchevsky A, Vardi Y, Lowenstein L, Gruenwald I. (January 2012). "Is the Female G-Spot Truly a Distinct Anatomic Entity?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011 (3): 719–26. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x. PMID 22240236.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|laydate=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysource=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c The Reproductive System at a Glance. John Wiley & Sons. 2014. p. 39. ISBN 1118607015. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Color Atlas of Physiology. Thieme. 2011. p. 310. ISBN 1449648517. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d Susan A. Orshan (2008). Maternity, Newborn, and Women's Health Nursing: Comprehensive Care Across the Lifespan. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 585–586. ISBN 0781742544. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

- ^ The Whole Pregnancy Handbook: An Obstetrician's Guide to Integrating Conventional and Alternative Medicine Before, During, and After Pregnancy. Penguin. 2005. pp. 435–436. ISBN 1592401112. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Our Bodies, Ourselves: Pregnancy and Birth. Simon & Schuster. 2008. pp. 172–174. ISBN 1416565914. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Maternity and Pediatric Nursing. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2009. p. 431. ISBN 0781780551. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Pharmacology for Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2010. pp. 951–952. ISBN 1449610730. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Danielsson, D., P. K. Teigen, and H. Moi. 2011. The genital econiche: Focus on microbiota and bacterial vaginosis" Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci 1230:48-58

- ^ a b Sexually Transmitted Disease: An Encyclopedia of Diseases, Prevention, Treatment, and Issues [2 volumes]: An Encyclopedia of Diseases, Prevention, Treatment, and Issues. ABC-CLIO. 2013. pp. 590–592. ISBN 1440801355. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Take Care of Yourself: The Complete Illustrated Guide to Medical Self-Care. Da Capo Press. 2013. pp. 427–428. ISBN 0786752181. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Anatomy Workbook (in 3 Volumes). World Scientific Publishing Company. 2007. p. 101. ISBN 9812569065. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

Digital examination per vaginam are made by placing one or two fingers in the vagina.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Anderson, Douglas M, ed. (2002). Mosby's Medical, Nursing & Allied Health Dictionary (6th UK ed.). St. Louis, Missouri, USA: Mosby. p. 1324. ISBN 0-7234-3225-2.

- ^ Koda-Kimble and Young's Applied Therapeutics: The Clinical Use of Drugs. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2012. pp. 1636–1641. ISBN 1609137132. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Drug Delivery Systems, Third Edition. CRC Press. 2011. p. 337. ISBN 1439806187. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Pharmacology for Nursing Care. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2014. p. 1146. ISBN 0323293549. Retrieved 22 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Fred F. Ferri (2012). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2013,5 Books in 1, Expert Consult - Online and Print,1: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2013. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 1134–1140. ISBN 0323083730. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Sudha Salhan (2011). Textbook of Gynecology. JP Medical Ltd. p. 270. ISBN 9350253690. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ Michele A. Paludi (2014). The Praeger Handbook on Women's Cancers: Personal and Psychosocial Insights. ABC-CLIO. p. 111. ISBN 1440828148. Retrieved 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Bartholin cyst". Mayo Clinic.com. 19 January 2010. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Hagen S, Stark D (2011). "Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 12: CD003882. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003882.pub4. PMID 22161382.

- ^ a b c Lloyd, Jillian et al. "Female genital appearance: 'normality' unfolds", British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, May 2005, 112(5), pp. 643–646. PMID 15842291

- ^ a b c Crooks, Robert; Baur, Karla (2010). Our Sexuality. Cengage Learning. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-495-81294-4. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Female genital mutilation". World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ^ Stone, Linda (2002). New Directions in Anthropological Kinship. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 164. ISBN 058538424X. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b Hutcherson, Hilda (2003). What Your Mother Never Told You about Sex. Penguin. p. 8. ISBN 0399528539. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ LaFont, Suzanne (2003). Constructing Sexualities: Readings in Sexuality, Gender, and Culture. Prentice Hall. p. 145. ISBN 013009661X. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Why Women Have Sex: Understanding Sexual Motivations from Adventure to Revenge (and Everything in Between). Macmillan. 2009. p. 33. ISBN 1429955228. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ a b Catherine Blackledge (2003). The Story of V: A Natural History of Female Sexuality. Rutgers University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0813534550. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Rosenthal, M. Sara (2003). Gynecological Health : a Comprehensive Sourcebook for Canadian Women. Viking Canada. p. 10. ISBN 0670043583. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

The urine flows from the bladder through the urethra to the outside. Little girls often make the common mistake of thinking that they're urinating out of their vaginas. A woman's urethra is two inches long, while a man's is ten inches long.

- ^ a b Meg Hickling (2005). The New Speaking of Sex: What Your Children Need to Know and When They Need to Know It. Wood Lake Publishing Inc. p. 149. ISBN 1896836704. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Lissa Rankin (2011). Sex, Orgasm, and Coochies: A Gynecologist Answers Your Most Embarrassing Questions. Macmillan. p. 22. ISBN 1429955228. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Denise Linn (2009). Secret Language of Signs. Random House Publishing Group. p. 276. ISBN 0307559556. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Thomas Walter Laqueur (1992). Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud. Harvard University Press. p. 236. ISBN 0674543556. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ^ Charles Zastrow (2007). Introduction to Social Work and Social Welfare: Empowering People. Cengage Learning. p. 228. ISBN 0495095109. Retrieved 15 March 2014.

- ^ Janice M. Irvine (2005). Disorders of Desire: Sexuality and Gender in Modern American Sexology. Temple University Press. pp. 37–38. ISBN 978-1592131518. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ Stephen Jay Gould (2002). The Structure of Evolutionary Theory. Harvard University Press. pp. 1262–1263. ISBN 0674006135. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- ^ The Challenge in South Asia: Development, Democracy and Regional Cooperation. United Nations University Press. 1989. p. 309. ISBN 0803996039. Retrieved 21 November 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Angier, Natalie (1999). Woman: An Intimate Geography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 92. ISBN 978-0-395-69130-4. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ a b Maines, Rachel P. (1998). The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria", the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6646-4.

- ^ a b Ensler, Eve (2001). The Vagina Monologues: The V-Day Edition. Random House LLC. ISBN 0375506586. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Morton, Mark (2004). The Lover's Tongue: A Merry Romp Through the Language of Love and Sex. Toronto, Canada: Insomniac Press. ISBN 978-1-894663-51-9.

- ^ "Definition of CUNT". Dictionary – Merriam-Webster online. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "cunt". Merriam-Webster's Learner's Dictionary. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ For example, Glue by Irvine Welsh, p.266, "Billy can be a funny cunt, a great guy..."

- ^ "pussy, n. and adj.2". Oxford English Dictionary (third ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2007.

- ^ Coleman, Christine (2006). Coming to Read "The Vagina Monologues": A Biomythographical Unravelling of the Narrative. University of New Brunswick. ISBN 0494466553. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ McCurry, Justin (15 July 2014). "Vagina selfie for 3D printers lands Japanese artist in trouble". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 July 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Momoh, Comfort (2005). "Female Genital Mutation". In Momoh, Comfort (ed.). Female Genital Mutilation. Radcliffe Publishing. pp. 5–12. ISBN 978-1-85775-693-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Luckett, W.P. 1977. Ontogeny of amniote fetal membranes and their application to phylogeny. Major patterns in Vertebrate Evolution. New York, London: Plenum Publishing Corporation. p 439-516

- ^ Szykman. M., Van Horn, R. C., Engh, A.L. Boydston, E. E. & Holekamp, K. E. (2007) Courtship and mating in free-living spotted hyenas. Behaviour. 144: 815–846.

- ^ Bekoff, M.; Diamond, J. (May 1976). "Precopulatory and Copulatory Behavior in Coyotes". Journal of Mammalogy. 57 (2). American Society of Mammalogists: 372–375. JSTOR 1379696.

- ^ Iannaccone, Philip (1997). Biological Aspects of Disease. CRC Press. pp. 315–316. ISBN 3718606135. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Comparative Anatomy: Manual of Vertebrate Dissection. Morton Publishing Company. 2012. pp. 66–68. ISBN 1617310042. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ The Insects: Structure and Function. Cambridge University Press. 2013. pp. 314–316. ISBN 052111389X. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ^ Brennan, P. L. R., Clark, C. J. & Prum, R. O. Explosive eversion and functional morphology of the duck penis supports sexual conflict in waterfowl genitalia. Proceedings. Biological sciences / The Royal Society 277, 1309–14 (2010).

- ^ http://www.theverge.com/2014/4/17/5617766/scientists-discover-insect-with-female-penis

- ^ Kazunori Yoshizawae; Rodrigo L. Ferreira; Yoshitaka Kamimura; Charles Lienhard (17 April 2014). "Female Penis, Male Vagina, and Their Correlated Evolution in a Cave Insect". Current Biology. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.022. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- ^ Cell Press (17 April 2014). "In sex-reversed cave insects, females have the penises". Science Daily. Retrieved 27 April 2014.