Robert A. Heinlein

Robert A. Heinlein | |

|---|---|

Heinlein signing autographs at Worldcon 1976 | |

| Born | Robert Anson Heinlein July 7, 1907 Butler, Missouri, U.S. |

| Died | May 8, 1988 (aged 80) Carmel, California, U.S. |

| Pen name | Anson MacDonald, Lyle Monroe, John Riverside, Caleb Saunders, Simon York |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story author, essayist, screenwriter |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1939–1988 |

| Genre | Science fiction, fantasy |

| Spouse | |

| Signature | |

Robert Anson Heinlein (/ˈhaɪnlaɪn/;[1][2][3] July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction writer. Often called the "dean of science fiction writers",[4] he was an influential and controversial author of the genre in his time.

He was one of the first science fiction writers to break into mainstream magazines such as The Saturday Evening Post in the late 1940s. He was one of the best-selling science fiction novelists for many decades, and he, Isaac Asimov, and Arthur C. Clarke are often considered to be the "Big Three" of science fiction authors.[5][6]

A notable writer of science fiction short stories, Heinlein was one of a group of writers who came to prominence under the editorship of John W. Campbell, Jr. in his Astounding Science Fiction magazine—though Heinlein denied that Campbell influenced his writing to any great degree.

Within the framework of his science fiction stories, Heinlein repeatedly addressed certain social themes: the importance of individual liberty and self-reliance, the obligation individuals owe to their societies, the influence of organized religion on culture and government, and the tendency of society to repress nonconformist thought. He also speculated on the influence of space travel on human cultural practices.

Heinlein was named the first Science Fiction Writers Grand Master in 1974.[7] He won Hugo Awards for four of his novels; in addition, fifty years after publication, three of his works were awarded "Retro Hugos"—awards given retrospectively for works that were published before the Hugo Awards came into existence.[8] In his fiction, Heinlein coined terms that have become part of the English language, including "grok" and "waldo", and speculative fiction, as well as popularizing existing terms like "TANSTAAFL", "pay it forward", and space marine. He also described a modern version of a waterbed in his novel The Door into Summer,[9] though he never patented or built one. In the first chapter of the novel "Space Cadet" he anticipated the cell phone, 35 years before the technology was invented by Motorola.[10] Several of Heinlein's works have been adapted for film and television.

Life

Birth and childhood

Heinlein was born on July 7, 1907 to Rex Ivar Heinlein (an accountant) and Bam Lyle Heinlein, in Butler, Missouri. He was a 6th-generation German-American: a family tradition had it that Heinleins fought in every American war starting with the War of Independence.[11]

His childhood was spent in Kansas City, Missouri.[12] The outlook and values of this time and place (in his own words, "The Bible Belt") had a definite influence on his fiction, especially his later works, as he drew heavily upon his childhood in establishing the setting and cultural atmosphere in works like Time Enough for Love and To Sail Beyond the Sunset.

Navy

Heinlein's experience in the U.S. Navy exerted a strong influence on his character and writing. Heinlein graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, in 1929 with a B.S. degree in naval engineering, and he served as an officer in the Navy. He was assigned to the new aircraft carrier USS Lexington in 1931, where he worked in radio communications, then in its earlier phases, with the carrier's aircraft. The captain of this carrier was Ernest J. King, who later served as the Chief of Naval Operations and Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet during World War II. Heinlein was frequently interviewed during his later years by military historians who asked him about Captain King and his service as the commander of the U.S. Navy's first modern aircraft carrier.

Heinlein also served aboard the destroyer USS Roper in 1933 and 1934, reaching the rank of lieutenant. His brother, Lawrence Heinlein, served in the U.S. Army, the U.S. Air Force, and the Missouri National Guard, and he rose to the rank of major general in the National Guard.[13]

In 1929, Heinlein married Elinor Curry of Kansas City in Los Angeles,[14] and their marriage lasted about a year.[2] His second marriage in 1932 to Leslyn MacDonald (1904–1981) lasted for 15 years. MacDonald was, according to the testimony of Heinlein's Navy buddy, Caleb 'Cab' Lansing, "astonishingly intelligent, widely read, and extremely liberal, though a registered Republican,"[15] while Isaac Asimov later recalled that Heinlein was, at the time, "a flaming liberal".[16] (See section: Politics of Robert Heinlein.)

California

In 1934, Heinlein was discharged from the Navy due to pulmonary tuberculosis. During a lengthy hospitalization, he developed a design for a waterbed.[17]

After his discharge, Heinlein attended a few weeks of graduate classes in mathematics and physics at the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA), but he soon quit either because of his health or from a desire to enter politics.[18]

Heinlein supported himself at several occupations, including real estate sales and silver mining, but for some years found money in short supply. Heinlein was active in Upton Sinclair's socialist End Poverty in California movement in the early 1930s. When Sinclair gained the Democratic nomination for Governor of California in 1934, Heinlein worked actively in the campaign. Heinlein himself ran for the California State Assembly in 1938, but he was unsuccessful.[19]

Author

While not destitute after the campaign—he had a small disability pension from the Navy—Heinlein turned to writing in order to pay off his mortgage. His first published story, "Life-Line", was printed in the August 1939 issue of Astounding Science-Fiction.[20] Originally written for a contest, it was instead sold to Astounding for significantly more than the contest's first-prize payoff. Another Future History story, "Misfit", followed in November.[20] Heinlein was quickly acknowledged as a leader of the new movement toward "social" science fiction. In California he hosted the Mañana Literary Society, a 1940-41 series of informal gatherings of new authors.[21] He was the guest of honor at Denvention, the 1941 Worldcon, held in Denver. During World War II, he did aeronautical engineering for the U.S. Navy, also recruiting Isaac Asimov and L. Sprague de Camp to work at the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard in Pennsylvania.[citation needed] As the war wound down in 1945, Heinlein began re-evaluating his career. The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, along with the outbreak of the Cold War, galvanized him to write nonfiction on political topics. In addition, he wanted to break into better-paying markets. He published four influential short stories for The Saturday Evening Post magazine, leading off, in February 1947, with "The Green Hills of Earth". That made him the first science fiction writer to break out of the "pulp ghetto". In 1950, the movie Destination Moon—the documentary-like film for which he had written the story and scenario, co-written the script, and invented many of the effects—won an Academy Award for special effects. Also, he embarked on a series of juvenile S.F. novels for the Charles Scribner's Sons publishing company that went from 1947 through 1959, at the rate of one book each autumn, in time for Christmas presents to teenagers. He also wrote for Boys' Life in 1952.

At the Philadelphia Naval Shipyard he had met and befriended a chemical engineer named Virginia "Ginny" Gerstenfeld. After the war, her engagement having fallen through, she moved to UCLA for doctoral studies in chemistry, and made contact again.

As his second wife's alcoholism gradually spun out of control,[22] Heinlein moved out and the couple filed for divorce. Heinlein's friendship with Virginia turned into a relationship and on October 21, 1948 — shortly after the decree nisi came through — they married in the town of Raton, New Mexico shortly after having set up house in Colorado. They would remain married until Heinlein's death.

As Heinlein's increasing success as a writer resolved their initial financial woes, they had a house custom built with various innovative features, later described in an article in Popular Mechanics. In 1965, after various chronic health problems of Virginia's were traced back to altitude sickness, they moved to Santa Cruz, California, at sea level, while they were building a new residence in the adjacent village of Bonny Doon, California.[23] Their unique circular California house—which like their Colorado house, he designed along with Virginia and then built himself—is on Bonny Doon Road 37°3′31.72″N 122°9′30.46″W / 37.0588111°N 122.1584611°W.

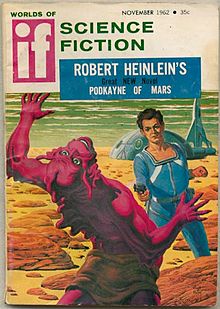

Ginny undoubtedly served as a model for many of his intelligent, fiercely independent female characters.[24][25] She was a chemist, rocket test engineer, and held a higher rank in the Navy than Heinlein himself. She was also an accomplished college athlete, earning four letters.[26] In 1953–1954, the Heinleins voyaged around the world (mostly via ocean liners and cargo liners, as Ginny detested flying), which Heinlein described in Tramp Royale, and which also provided background material for science fiction novels set aboard spaceships on long voyages, such as Podkayne of Mars and Friday. Ginny acted as the first reader of his manuscripts. Isaac Asimov believed that Heinlein made a swing to the right politically at the same time he married Ginny.

The Heinleins formed the small "Patrick Henry League" in 1958, and they worked in the 1964 Barry Goldwater Presidential campaign.[16]

When Robert A. Heinlein opened his Colorado Springs newspaper on April 5, 1958, he read a full-page ad demanding that the Eisenhower Administration stop testing nuclear weapons. The science-fiction author was flabbergasted. He called for the formation of the Patrick Henry League and spent the next several weeks writing and publishing his own polemic that lambasted "Communist-line goals concealed in idealistic-sounding nonsense" and urged Americans not to become "soft-headed."[27]

Heinlein had used topical materials throughout his juvenile series beginning in 1947, but in 1959, his novel Starship Troopers was considered by the editors and owners of Scribner's to be too controversial for one of its prestige lines, and it was rejected.[28]

Heinlein found another publisher (Putnam), feeling himself released from the constraints of writing novels for children, and he began to write "my own stuff, my own way",[citation needed] and he wrote a series of challenging books that redrew the boundaries of science fiction, including Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) and The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress (1966).

Later life and death

Beginning in 1970, Heinlein had a series of health crises, broken by strenuous periods of activity in his hobby of stonemasonry. (In a private correspondence, he referred to that as his "usual and favorite occupation between books.")[29] The decade began with a life-threatening attack of peritonitis, recovery from which required more than two years, and treatment of which required multiple transfusions of Heinlein's rare blood type, A2 negative.[30] As soon as he was well enough to write again, he began work on Time Enough for Love (1973), which introduced many of the themes found in his later fiction.

In the mid-1970s, Heinlein wrote two articles for the Britannica Compton Yearbook.[31] He and Ginny crisscrossed the country helping to reorganize blood donation in the United States in an effort to assist the system which had saved his life,[30] and he was the guest of honor at the Worldcon for the third time at MidAmeriCon in Kansas City, Missouri, in 1976. While vacationing in Tahiti in early 1978, he suffered a transient ischemic attack. Over the next few months, he became more and more exhausted, and his health again began to decline. The problem was determined to be a blocked carotid artery, and he had one of the earliest known carotid bypass operations to correct it. Heinlein and Virginia had been smokers,[32] and smoking appears often in his fiction, as do fictitious strikable self-lighting cigarettes.

In 1980 Robert Heinlein was a member of the Citizens Advisory Council on National Space Policy, chaired by Jerry Pournelle, which met at the home of SF writer Larry Niven to write space policy papers for the incoming Reagan Administration. Members included Buzz Aldrin, General Daniel Graham, rocket engineer Max Hunter, North American VP and Space Shuttle manager George Merrick, and other aerospace industry leaders. Policy recommendations from the Council included ballistic missile defense concepts which were later transformed into what was called the Strategic Defense Initiative by those who favored it, and "Star Wars" as a term of derision coined by Senator Ted Kennedy. Heinlein contributed to the Council contribution to the Reagan "Star Wars" speech of Spring 1983.

Asked to appear before a Joint Committee of the U.S. House and Senate that year, he testified on his belief that spin-offs from space technology were benefiting the infirm and the elderly. Heinlein's surgical treatment re-energized him, and he wrote five novels from 1980 until he died in his sleep from emphysema and heart failure on May 8, 1988.

At that time, he had been putting together the early notes for another World as Myth novel. Several of his other works have been published posthumously.[33]

After his death, his wife Virginia Heinlein issued a compilation of Heinlein's correspondence and notes into a somewhat autobiographical examination of his career, published in 1989 under the title Grumbles from the Grave. Heinlein's archive is housed by the Special Collections department of McHenry Library at the University of California at Santa Cruz. The collection includes manuscript drafts, correspondence, photographs and artifacts. A substantial portion of the archive has been digitized and it is available online through the Robert A. and Virginia Heinlein Archives.[34]

Works

Heinlein published 32 novels, 59 short stories, and 16 collections during his life. Four films, two television series, several episodes of a radio series, and a board game have been derived more or less directly from his work. He wrote a screenplay for one of the films. Heinlein edited an anthology of other writers' SF short stories.

Three nonfiction books and two poems have been published posthumously. For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs was published posthumously in 2003; Variable Star, written by Spider Robinson based on an extensive outline by Heinlein, was published in September 2006. Four collections have been published posthumously.[20]

Series

Over the course of his career Heinlein wrote three somewhat overlapping series.

Early work, 1939–1958

Heinlein began his career as a writer of stories for Astounding Science Fiction, a highly respected science fiction magazine, which was edited by John Campbell. The science fiction writer Frederik Pohl has described Heinlein as "that greatest of Campbell-era sf writers".[35] Isaac Asimov said that, from the time of his first story, it was accepted that Heinlein was the best science fiction writer in existence, adding that he would hold this title through his lifetime.[36]

Alexei and Cory Panshin noted that Heinlein's impact was immediately felt. In 1940, the year after selling 'Life-Line' to Campbell, he wrote three short novels, four novelettes, and seven short stories. They went on to say that "No one ever dominated the science fiction field as Bob did in the first few years of his career."[37] Alexei expresses awe in Heinlein's ability to show readers a world so drastically different from the one we live in now, yet have so many similarities. He says that "We find ourselves not only in a world other than our own, but identifying with a living, breathing individual who is operating within its context, and thinking and acting according to its terms."[38]

The first novel that Heinlein wrote, For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs (1939), did not see print during his lifetime, but Robert James tracked down the manuscript and it was published in 2003. Though some regard it as a failure as a novel,[12] considering it little more than a disguised lecture on Heinlein's social theories, some readers took a very different view. In a review of it, John Clute wrote: "I'm not about to suggest that if Heinlein had been able to publish [such works] openly in the pages of Astounding in 1939, SF would have gotten the future right; I would suggest, however, that if Heinlein, and his colleagues, had been able to publish adult SF in Astounding and its fellow journals, then SF might not have done such a grotesquely poor job of prefiguring something of the flavor of actually living here at the onset of 2004."[39]

For Us, the Living was intriguing as a window into the development of Heinlein's radical ideas about man as a social animal, including his interest in free love. The root of many themes found in his later stories can be found in this book. It also contained much material that could be considered background for his other novels, including a detailed description of the protagonist's treatment to avoid being banned to Coventry (a lawless land in the Heinlein mythos where unrepentant law-breakers are exiled).[citation needed]

It appears that Heinlein at least attempted to live in a manner consistent with these ideals, even in the 1930s, and had an open relationship in his marriage to his second wife, Leslyn. He was also a nudist;[2] nudism and body taboos are frequently discussed in his work. At the height of the Cold War, he built a bomb shelter under his house, like the one featured in Farnham's Freehold.[2]

After For Us, The Living, Heinlein began selling (to magazines) first short stories, then novels, set in a Future History, complete with a time line of significant political, cultural, and technological changes. A chart of the future history was published in the May 1941 issue of Astounding. Over time, Heinlein wrote many novels and short stories that deviated freely from the Future History on some points, while maintaining consistency in some other areas. The Future History was eventually overtaken by actual events. These discrepancies were explained, after a fashion, in his later World as Myth stories.

Heinlein's first novel published as a book, Rocket Ship Galileo, was initially rejected because going to the moon was considered too far out, but he soon found a publisher, Scribner's, that began publishing a Heinlein juvenile once a year for the Christmas season.[40] Eight of these books were illustrated by Clifford Geary in a distinctive white-on-black scratchboard style.[41] Some representative novels of this type are Have Space Suit—Will Travel, Farmer in the Sky, and Starman Jones. Many of these were first published in serial form under other titles, e.g., Farmer in the Sky was published as Satellite Scout in the Boy Scout magazine Boys' Life. There has been speculation that Heinlein's intense obsession with his privacy was due at least in part to the apparent contradiction between his unconventional private life and his career as an author of books for children, but For Us, The Living also explicitly discusses the political importance Heinlein attached to privacy as a matter of principle.[42]

The novels that Heinlein wrote for a young audience are commonly called "the Heinlein juveniles", and they feature a mixture of adolescent and adult themes. Many of the issues that he takes on in these books have to do with the kinds of problems that adolescents experience. His protagonists are usually very intelligent teenagers who have to make their way in the adult society they see around them. On the surface, they are simple tales of adventure, achievement, and dealing with stupid teachers and jealous peers. Heinlein was a vocal proponent of the notion that juvenile readers were far more sophisticated and able to handle more complex or difficult themes than most people realized. His juvenile stories often had a maturity to them that made them readable for adults. Red Planet, for example, portrays some very subversive themes, including a revolution in which young students are involved; his editor demanded substantial changes in this book's discussion of topics such as the use of weapons by children and the misidentified sex of the Martian character. Heinlein was always aware of the editorial limitations put in place by the editors of his novels and stories, and while he observed those restrictions on the surface, was often successful in introducing ideas not often seen in other authors' juvenile SF.

In 1957, James Blish wrote that one reason for Heinlein's success "has been the high grade of machinery which goes, today as always, into his story-telling. Heinlein seems to have known from the beginning, as if instinctively, technical lessons about fiction which other writers must learn the hard way (or often enough, never learn). He does not always operate the machinery to the best advantage, but he always seems to be aware of it."[43]

1959–1960

Heinlein decisively ended his juvenile novels with Starship Troopers (1959), a controversial work and his personal riposte to leftists calling for President Dwight D. Eisenhower to stop nuclear testing in 1958. "The "Patrick Henry" ad shocked 'em," he wrote many years later. "Starship Troopers outraged 'em."[44] Starship Troopers is a coming-of-age story about duty, citizenship, and the role of the military in society.[45] The book portrays a society in which suffrage is earned by demonstrated willingness to place society's interests before one's own, at least for a short time and often under onerous circumstances, in government service; in the case of the protagonist, this was military service.

Later, in Expanded Universe, Heinlein said that it was his intention in the novel that service could include positions outside strictly military functions such as teachers, police officers, and other government positions. This is presented in the novel as an outgrowth of the failure of unearned suffrage government and as a very successful arrangement. In addition, the franchise was only awarded after leaving the assigned service, thus those serving their terms—in the military, or any other service—were excluded from exercising any franchise. Career military were completely disenfranchised until retirement.

The name Starship Troopers was licensed for an unrelated, B movie script called Bug Hunt at Outpost Nine, which was then retitled to benefit from the book's credibility.[46] The resulting film, entitled Starship Troopers (1997), which was written by Ed Neumeier and directed by Paul Verhoeven, had little relationship to the book, beyond the inclusion of character names, the depiction of space marines, and the concept of suffrage earned by military service. Fans of Heinlein were critical of the movie, which they considered a betrayal of Heinlein's philosophy, presenting the society in which the story takes place as fascist.[47] Christopher Weuve, an admirer of Heinlein, has said that the society depicted in the film showed only a superficial resemblance to the society that Heinlein describes in his book. Weuve summed up his critique of the film as follows. First, "while the Terran Federation in Starship Troopers [the novel] is specifically stated to be a representative democracy, Ed Neumeier decided to make the government into a fascist state ... Second, the book was multiracial, but not so the movie: all the non-Anglo characters from the book have been replaced by characters who look like they stepped out of the Aryan edition of GQ... Third, there is real element of sadism present in the movie which simply isn't present in the book."[48]

Likewise, the powered armor technology that is not only central to the book, but became a standard subgenre of science fiction thereafter, is completely absent in the movie, where the characters use World War II-technology weapons and wear light combat gear little more advanced than that.[49] According to Verhoeven, this, and the fascist tone of the book, reflected his own experience in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands during World War II.[50]

In fact, Verhoeven had not even read the book, attempting to after he bought the rights to add to his existing movie, and disliking it: "I stopped after two chapters because it was so boring...It is really quite a bad book. I asked Ed Neumeier to tell me the story because I just couldn't read the thing".[51]

Middle period work, 1961–1973

From about 1961 (Stranger in a Strange Land) to 1973 (Time Enough for Love), Heinlein explored some of his most important themes, such as individualism, libertarianism, and free expression of physical and emotional love. Three novels from this period, Stranger in a Strange Land, The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, and Time Enough for Love, won the Libertarian Futurist Society's Prometheus Hall of Fame Award, designed to honor classic libertarian fiction.[52] Jeff Riggenbach described The Moon is a Harsh Mistress as "unquestionably one of the three or four most influential libertarian novels of the last century".[53]

Heinlein did not publish Stranger in a Strange Land until some time after it was written, and the themes of free love and radical individualism are prominently featured in his long-unpublished first novel, For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs.

The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress tells of a war of independence waged by the Lunar penal colonies, with significant comments from a major character, Professor La Paz, regarding the threat posed by government to individual freedom.

Although Heinlein had previously written a few short stories in the fantasy genre, during this period he wrote his first fantasy novel, Glory Road, and in Stranger in a Strange Land and I Will Fear No Evil, he began to mix hard science with fantasy, mysticism, and satire of organized religion. Critics William H. Patterson, Jr., and Andrew Thornton believe that this is simply an expression of Heinlein's longstanding philosophical opposition to positivism.[54][verification needed] Heinlein stated that he was influenced by James Branch Cabell in taking this new literary direction. The penultimate novel of this period, I Will Fear No Evil, is according to critic James Gifford "almost universally regarded as a literary failure"[55] and he attributes its shortcomings to Heinlein's near-death from peritonitis.

Later work, 1980–1987

After a seven-year hiatus brought on by poor health, Heinlein produced five new novels in the period from 1980 (The Number of the Beast) to 1987 (To Sail Beyond the Sunset). These books have a thread of common characters and time and place. They most explicitly communicated Heinlein's philosophies and beliefs, and many long, didactic passages of dialog and exposition deal with government, sex, and religion. These novels are controversial among his readers and one critic, Dave Langford, has written about them very negatively.[56] Heinlein's four Hugo awards were all for books written before this period.

Some of these books, such as The Number of the Beast and The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, start out as tightly constructed adventure stories, but transform into philosophical fantasias at the end. It is a matter of opinion whether this demonstrates a lack of attention to craftsmanship or a conscious effort to expand the boundaries of science fiction, either into a kind of magical realism, continuing the process of literary exploration that he had begun with Stranger in a Strange Land, or into a kind of literary metaphor of quantum science (The Number of the Beast dealing with the Observer problem, and The Cat Who Walks Through Walls being a direct reference to the Schrödinger's cat thought experiment).

Most of the novels from this period are recognized by critics as forming an offshoot from the Future History series, and referred to by the term World as Myth.[57]

The tendency toward authorial self-reference begun in Stranger in a Strange Land and Time Enough for Love becomes even more evident in novels such as The Cat Who Walks Through Walls, whose first-person protagonist is a disabled military veteran who becomes a writer, and finds love with a female character.[58]

The 1982 novel Friday, a more conventional adventure story (borrowing a character and backstory from the earlier short story Gulf, also containing suggestions of connection to The Puppet Masters) continued a Heinlein theme of expecting what he saw as the continued disintegration of Earth's society, to the point where the title character is strongly encouraged to seek a new life off-planet. It concludes with a traditional Heinlein note, as in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress or Time Enough for Love, that freedom is to be found on the frontiers.

The 1984 novel Job: A Comedy of Justice is a sharp satire of organized religion. Heinlein himself was agnostic.[59][60]

Posthumous publications

Several Heinlein works have been published since his death, including the aforementioned For Us, The Living as well as 1989's Grumbles from the Grave, a collection of letters between Heinlein and his editors and agent; 1992's Tramp Royale, a travelogue of a southern hemisphere tour the Heinleins took in the 1950s; Take Back Your Government, a how-to book about participatory democracy written in 1946; and a tribute volume called Requiem: Collected Works and Tributes to the Grand Master, containing some additional short works previously unpublished in book form. Off the Main Sequence, published in 2005, includes three short stories never before collected in any Heinlein book (Heinlein called them "stinkeroos").

Spider Robinson, a colleague, friend, and admirer of Heinlein,[61] wrote Variable Star, based on an outline and notes for a juvenile novel that Heinlein prepared in 1955. The novel was published as a collaboration, with Heinlein's name above Robinson's on the cover, in 2006.

A complete collection of Heinlein's published work, conformed and copy-edited by several Heinlein scholars including biographer William H. Patterson has been published[62] by the Heinlein Trust as the "Virginia Edition", after his wife.

Views

Heinlein's books probe a range of ideas about a range of topics such as sex, race, politics, and the military. Many were seen as radical or as ahead of their time in their social criticism. His books have inspired considerable debate about the specifics, and the evolution, of Heinlein's own opinions, and have earned him both lavish praise and a degree of criticism. He has also been accused of contradicting himself on various philosophical questions.[63]

As Ted Gioia notes:

[Heinlein] has been accused of many things—of being a libertine or a libertarian, a fascist or a fetishist, pre-Oedipal or just plain preposterous. Heinlein's critics cut across all ends of the political spectrum, as do his fans. His admirers have ranged from Madalyn Murray O'Hair, the founder of American Atheists, to members of the Church of All Worlds, who hail Heinlein as a prophet. Apparently both true believers and non-believers, and perhaps some agnostics, have found sustenance in Heinlein's prodigious output.[64]

Brian Doherty cites William Patterson, saying that the best way to gain an understanding of Heinlein is as a "full-service iconoclast, the unique individual who decides that things do not have to be, and won't continue, as they are." He says this vision is "at the heart of Heinlein, science fiction, libertarianism, and America. Heinlein imagined how everything about the human world, from our sexual mores to our religion to our automobiles to our government to our plans for cultural survival, might be flawed, even fatally so."[65]

The critic Elizabeth Anne Hull, for her part, has praised Heinlein for his interest in exploring fundamental life questions, especially questions about "political power—our responsibilities to one another" and about "personal freedom, particularly sexual freedom."[66]

Politics

Heinlein's political positions evolved throughout his life. Heinlein's early political leanings were liberal.[67] In 1934 he worked actively for the Democratic campaign of Upton Sinclair for Governor of California. After Sinclair's loss, Heinlein became an anti-Communist Democratic activist. He made an unsuccessful bid for a California State Assembly seat in 1938.[67] Heinlein's first novel, For Us, The Living (written 1939), consists largely of speeches advocating the Social Credit system, and the early story "Misfit" (1939) deals with an organization that seems to be Franklin D. Roosevelt's Civilian Conservation Corps translated into outer space.[citation needed]

Heinlein's fiction of the 1940s and 1950s, however, began to espouse conservative views. After 1945, he came to believe that a strong world government was the only way to avoid mutual nuclear annihilation. His 1949 novel Space Cadet describes a future scenario where a military-controlled global government enforces world peace. Heinlein ceased considering himself a Democrat in 1954.[67]

Heinlein considered himself a libertarian, but in a letter to Judith Merril in 1967 (never sent) he also described himself as a philosophical anarchist or an "autarchist" [68]

Stranger in a Strange Land was embraced by the hippie counterculture, and libertarians have found inspiration in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. Both groups found resonance with his themes of personal freedom in both thought and action.[53]

Race

Heinlein grew up in the era of racial segregation in the United States and wrote some of his most influential fiction at the height of the US civil rights movement. His early juveniles were very much ahead of their time both in their explicit rejection of racism and in their inclusion of protagonists of color—in the context of science fiction before the 1960s, the mere existence of characters of color was a remarkable novelty, with green occurring more often than brown.[69] For example, his second juvenile, the 1948 Space Cadet, explicitly uses aliens as a metaphor for minorities. In his juvenile, Star Beast, the de facto foreign minister of the Terran government is an undersecretary, a Mr. Kiku, who is from Africa.[70] Heinlein explicitly states his skin is "ebony black", and that Kiku is in an arranged marriage that is happy.[71]

In a number of his stories, Heinlein challenges his readers' possible racial preconceptions by introducing a strong, sympathetic character, only to reveal much later that he or she is of African or other ancestry; in several cases, the covers of the books show characters as being light-skinned, when in fact the text states, or at least implies, that they are dark-skinned or of African ancestry.[74] Heinlein repeatedly denounced racism in his non-fiction works, including numerous examples in Expanded Universe.

Heinlein reveals in Starship Troopers that the novel's protagonist and narrator, Johnny Rico, the formerly disaffected scion of a wealthy family, is Filipino, actually named "Juan Rico" and speaks Tagalog in addition to English.

Race was a central theme in some of Heinlein's fiction. The most prominent and controversial example is Farnham's Freehold, which casts a white family into a future in which white people are the slaves of cannibalistic black rulers. In the 1941 novel Sixth Column (also known as The Day After Tomorrow), a white resistance movement in the United States defends itself against an invasion by an Asian fascist state (the "Pan-Asians") using a "super-science" technology that allows ray weapons to be tuned to specific races. The book is sprinkled with racist slurs against Asian people, and blacks and Hispanics are not mentioned at all. The idea for the story was pushed on Heinlein by editor John W. Campbell, and Heinlein wrote later that he had "had to re-slant it to remove racist aspects of the original story line" and that he did not "consider it to be an artistic success."[75][76] (However, the novel prompted a heated debate in the scientific community regarding the plausibility of developing ethnic bioweapons.)[77]

It has been suggested that the strongly hierarchical and anti-individualistic "Bugs" in Starship Troopers were meant to represent the Chinese or Japanese, but Heinlein claimed to have written the book in response to "calls for the unilateral ending of nuclear testing by the United States."[78] Heinlein suggests in the book that the Bugs are a good example of Communism being something that humans cannot successfully adhere to, since humans are strongly defined individuals, whereas the Bugs, being a collective, can all contribute to the whole without consideration of individual desire.[79]

Heinlein's biographer William Patterson [80] relates a number of instances in which Heinlein responded to anti-semitic remarks by (falsely) claiming to be half-Jewish himself and breaking off all further contact with the anti-semite. (Heinlein's actual ancestry is German-American on his father's side and Scots-Irish American on his mother's side, both going back to the Colonial era in the USA.)

Individualism and self-determination

In keeping with his belief in individualism, his work for adults—and sometimes even his work for juveniles—often portrays both the oppressors and the oppressed with considerable ambiguity. Heinlein believed that individualism was incompatible with ignorance. He believed that an appropriate level of adult competence was achieved through a wide-ranging education, whether this occurred in a classroom or not. In his juvenile novels, more than once a character looks with disdain at a student's choice of classwork, saying, "Why didn't you study something useful?"[81] In Time Enough for Love, Lazarus Long gives a long list of capabilities that anyone should have, concluding, "Specialization is for insects." The ability of the individual to create himself is explored in stories such as I Will Fear No Evil, "—All You Zombies—", and "By His Bootstraps".

Sexual issues

For Heinlein, personal liberation included sexual liberation, and free love was a major subject of his writing starting in 1939, with For Us, The Living. During his early period, Heinlein's writing for younger readers needed to take account of both editorial perceptions of sexuality in his novels, and potential perceptions among the buying public; as critic William H. Patterson has put it, his dilemma was "to sort out what was really objectionable from what was only excessive over-sensitivity to imaginary librarians".[82] By his middle period, sexual freedom and the elimination of sexual jealousy were a major theme of Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), in which the progressively minded but sexually conservative reporter, Ben Caxton, acts as a dramatic foil for the less parochial characters, Jubal Harshaw and Valentine Michael Smith (Mike). Another of the main characters, Jill, is homophobic.[83]

Gary Westfahl points out that "Heinlein is a problematic case for feminists; on the one hand, his works often feature strong female characters and vigorous statements that women are equal to or even superior to men; but these characters and statements often reflect hopelessly stereotypical attitudes about typical female attributes. It is disconcerting, for example, that in Expanded Universe Heinlein calls for a society where all lawyers and politicians are women, essentially on the grounds that they possess a mysterious feminine practicality that men cannot duplicate."[84] Also, in Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land, Jill, one of the main characters, says, "nine times out of ten, if a girl gets raped it's partly her fault".[83]

In books written as early as 1956, Heinlein dealt with incest and the sexual nature of children. Many of his books (including Time for the Stars, Glory Road, Time Enough for Love, and The Number of the Beast) dealt explicitly or implicitly with incest, sexual feelings and relations between adults and children, or both.[85] The treatment of these themes include the romantic relationship and eventual marriage (once the girl becomes an adult via time-travel) of a 30-year-old engineer and an 11-year-old girl in The Door into Summer or the more overt intra-familial incest in To Sail Beyond the Sunset and Farnham's Freehold. Peers such as L. Sprague de Camp and Damon Knight have commented critically on Heinlein's portrayal of incest and pedophilia in a lighthearted and even approving manner.[85]

Philosophy

In To Sail Beyond the Sunset, Heinlein has the main character, Maureen, state that the purpose of metaphysics is to ask questions: Why are we here? Where are we going after we die? (and so on), and that you are not allowed to answer the questions. Asking the questions is the point of metaphysics, but answering them is not, because once you answer this kind of question, you cross the line into religion. Maureen does not state a reason for this; she simply remarks that such questions are "beautiful" but lack answers. Maureen's son/lover Lazarus Long makes a related remark in Time Enough for Love. In order for us to answer the "big questions" about the universe, Lazarus states at one point, it would be necessary to stand outside the universe.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Heinlein was deeply interested in Alfred Korzybski's General Semantics and attended a number of seminars on the subject. His views on epistemology seem to have flowed from that interest, and his fictional characters continue to express Korzybskian views to the very end of his writing career. Many of his stories, such as Gulf, If This Goes On—, and Stranger in a Strange Land, depend strongly on the premise, related to the well-known Sapir–Whorf hypothesis, that by using a correctly designed language, one can change or improve oneself mentally, or even realize untapped potential (as in the case of Joe Green in Gulf).[citation needed]

When Ayn Rand's novel The Fountainhead was published, Heinlein was very favorably impressed, as quoted in "Grumbles..." and mentioned John Galt—the hero in Rand's Atlas Shrugged—as a heroic archetype in The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. He was also strongly affected by the religious philosopher P. D. Ouspensky.[12] Freudianism and psychoanalysis were at the height of their influence during the peak of Heinlein's career, and stories such as Time for the Stars indulged in psychological theorizing.

However, he was skeptical about Freudianism, especially after a struggle with an editor who insisted on reading Freudian sexual symbolism into his juvenile novels. Heinlein was fascinated by the social credit movement in the 1930s. This is shown in Beyond This Horizon and in his 1938 novel For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, which was finally published in 2003, long after his death. He was strongly committed to cultural relativism, and the sociologist Margaret Mader in his novel Citizen of the Galaxy is clearly a reference to Margaret Mead.[citation needed]

Pay it forward

The term "pay it forward", though it was already in occasional use as a quotation, was popularized by Robert A. Heinlein in his book Between Planets, published in 1951:

The banker reached into the folds of his gown, pulled out a single credit note. "But eat first—a full belly steadies the judgment. Do me the honor of accepting this as our welcome to the newcomer."

His pride said no; his stomach said YES! Don took it and said, "Uh, thanks! That's awfully kind of you. I'll pay it back, first chance."

"Instead, pay it forward to some other brother who needs it."

Heinlein was a mentor to Ray Bradbury, giving him help and quite possibly passing on the concept, made famous by the publication of a letter from him to Heinlein thanking him. In Bradbury's novel Dandelion Wine, published in 1957, when the main character Douglas Spaulding is reflecting on his life being saved by Mr. Jonas, the Junkman:

How do I thank Mr. Jonas, he wondered, for what he's done? How do I thank him, how pay him back? No way, no way at all. You just can't pay. What then? What? Pass it on somehow, he thought, pass it on to someone else. Keep the chain moving. Look around, find someone, and pass it on. That was the only way....

Bradbury has also advised that writers he has helped thank him by helping other writers.

Heinlein both preached and practiced this philosophy; now the Heinlein Society, a humanitarian organization founded in his name, does so, attributing the philosophy to its various efforts, including Heinlein for Heroes, the Heinlein Society Scholarship Program, and Heinlein Society blood drives.[86] Author Spider Robinson made repeated reference to the doctrine, attributing it to his spiritual mentor Heinlein.[87]

Influence and legacy

The Dean of Science Fiction

Heinlein is usually identified, along with Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke, as one of the three masters of science fiction to arise in the so-called Golden Age of science fiction, associated with John W. Campbell and his magazine Astounding.[88] In the 1950s he was a leader in bringing science fiction out of the low-paying and less prestigious "pulp ghetto". Most of his works, including short stories, have been continuously in print in many languages since their initial appearance and are still available as new paperbacks decades after his death.

Robert Heinlein was also influenced by the American writer, philosopher and humorist Charles Fort who is credited as a major influence on most of the leading science-fiction writers of the 20th-century. Heinlein was a lifelong member of the International Fortean Organization also known as INFO, the successor to the original Fortean Society. Heinlein's letters were often displayed on the walls of the INFO offices, and his active participation in the organization is mentioned in the INFO Journal.[citation needed]

He was at the top of his form during, and himself helped to initiate, the trend toward social science fiction, which went along with a general maturing of the genre away from space opera to a more literary approach touching on such adult issues as politics and human sexuality. In reaction to this trend, hard science fiction began to be distinguished as a separate subgenre, but paradoxically Heinlein is also considered a seminal figure in hard science fiction, due to his extensive knowledge of engineering, and the careful scientific research demonstrated in his stories. Heinlein himself stated—with obvious pride—that in the days before pocket calculators, he and his wife Virginia once worked for several days on a mathematical equation describing an Earth-Mars rocket orbit, which was then subsumed in a single sentence of the novel Space Cadet.

Influence among writers

Heinlein has had a nearly ubiquitous influence on other science fiction writers. In a 1953 poll of leading science fiction authors, he was cited more frequently as an influence than any other modern writer.[89] Critic James Gifford writes that "Although many other writers have exceeded Heinlein's output, few can claim to match his broad and seminal influence. Scores of science fiction writers from the prewar Golden Age through the present day loudly and enthusiastically credit Heinlein for blazing the trails of their own careers, and shaping their styles and stories."[90]

Writer David Gerrold, responsible for creating the tribbles in Star Trek, also credited Heinlein as the inspiration for his Dingilliad series of novels. Gregory Benford refers to his novel Jupiter Project as a Heinlein tribute. Similarly, Charles Stross says his Hugo Award-nominated novel Saturn's Children is "a space opera and late-period Robert A. Heinlein tribute",[91] referring to Heinlein's Friday[92]

Words and phrases coined

Outside the science fiction community, several words and phrases coined or adopted by Heinlein have passed into common English usage:

- Waldo, protagonist in the eponymous short story "Waldo" whose name came to mean mechanical/robot arms in the real world that are akin to the ones used by the character in the story.

- TANSTAAFL, short for There Ain't No Such Thing as a Free Lunch, an existing term that refers to the fact that things supposedly given free always have some real cost, popularized in The Moon is a Harsh Mistress.

- Moonbat[93] used in United States politics as a pejorative political epithet referring to progressives or leftists, was originally the name of a space ship in his story Space Jockey.

- Grok, a "Martian" word for understanding a thing so fully as to become one with it, from Stranger in a Strange Land.

- Space Marine, an existing term popularized by Heinlein in short stories, the concept then being made famous by Starship Troopers, though the term "space marine" is not used in that novel.

- Speculative fiction, a term Heinlein used for the separation of serious, consistent Science Fiction writing, from the pop "sci fi" of the day, which generally took great artistic license with human knowledge, amounting to being more like space fantasy than science fiction.

Inspiring culture and technology

In 1962, Oberon Zell-Ravenheart (then still using his birth name, Tim Zell) founded the Church of All Worlds, a Neopagan religious organization modeled in many ways after the treatment of religion in the novel Stranger in a Strange Land. This spiritual path included several ideas from the book, including non-mainstream family structures, social libertarianism, water-sharing rituals, an acceptance of all religious paths by a single tradition, and the use of several terms such as "grok", "Thou art God", and "Never Thirst". Though Heinlein was neither a member nor a promoter of the Church, there was a frequent exchange of correspondence between Zell and Heinlein, and he was a paid subscriber to their magazine, Green Egg. This Church still exists as a 501(C)(3) religious organization incorporated in California, with membership worldwide, and it remains an active part of the neopagan community today.[94]

Heinlein was influential in making space exploration seem to the public more like a practical possibility. His stories in publications such as The Saturday Evening Post took a matter-of-fact approach to their outer-space setting, rather than the "gee whiz" tone that had previously been common. The documentary-like film Destination Moon advocated a Space Race with an unspecified foreign power almost a decade before such an idea became commonplace, and was promoted by an unprecedented publicity campaign in print publications. Many of the astronauts and others working in the U.S. space program grew up on a diet of the Heinlein juveniles,[original research?] best evidenced by the naming of a crater on Mars after him, and a tribute interspersed by the Apollo 15 astronauts into their radio conversations while on the moon.[95]

Heinlein was also a guest commentator for Walter Cronkite during Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin's Apollo 11 moon landing. He remarked to Cronkite during the landing that, "This is the greatest event in human history, up to this time. This is—today is New Year's Day of the Year One."[96] Businessman and entrepreneur Elon Musk says that Heinlein's books have helped inspire his career.[97]

Heinlein Society

The Heinlein Society was founded by Virginia Heinlein on behalf of her husband, to "pay forward" the legacy of the writer to future generations of "Heinlein's Children." The foundation has programs to:

- "Promote Heinlein blood drives."

- "Provide educational materials to educators."

- "Promote scholarly research and overall discussion of the works and ideas of Robert Anson Heinlein."

The Heinlein society also established the Robert A. Heinlein Award in 2003 "for outstanding published works in science fiction and technical writings to inspire the human exploration of space."[98][99]

In popular culture

- Heinlein appears as a major character in Paul Malmont's historical novel The Astounding, the Amazing, and the Unknown (2011).

- In John Varley's novels Steel Beach and The Golden Globe, the author includes a society of "Heinleiners" as key plot elements. This fictional community is composed of rugged individualists who, like classic Heinlein characters, are determined to provide for themselves and those around them voluntarily, without government coercion. Their name is explained to originate with a colony ship they built called the Robert Heinlein, which is turned into their home base on the moon.

- In the 1985 Science Fiction film Explorers, one character is a genetically engineered talking rat named Heinlein.[100]

- In the Star Trek TV series, "The Trouble with Tribbles", the title creatures in the episode resembled the Martian flat cats in Heinlein's 1952 novel The Rolling Stones. Script writer David Gerrold was concerned that he had inadvertently plagiarized the novel which he had read fifteen years before.[101] These concerns were brought up by a research team, who suggested that the rights to the novel should be purchased from Heinlein. One of the producers phoned Heinlein, who only asked for a signed copy of the script and later sent a note to Gerrold after it aired to thank him for the script.[102]

- In the Star Trek novel The Romulan War: Beneath the Raptor's Wing, a starship during a key space battle is called the USS Heinlein.[103] In Star Trek: The Next Generation, the Enterprise had a shuttle named Heinlein, shown as being tested in Hangar 2 in the episode "Evolution".

- Heinlein appears indirectly as the purported author of an ancient manuscript, supposedly one of his "unwritten stories", 'The Stone Pillow', in the novel The Counterfeit Heinlein by Laurence M. Janifer.[104]

- Jon Anderson of the rock band Yes was inspired by a Heinlein novel's title for his song Starship Trooper.

- Jimmy Webb "appropriated" the author's title The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress for his song of the same name:

Robert Heinlein was a kind of early mentor of mine. I started reading his books when I was eight years old. ... I guess I was really getting more of my education out of science-fiction than out of public school. I was reading Ray Bradbury and Isaac Asimov and learning a great deal about the patois of the language itself and how these words were being used to create emotions. I was learning this from writers without even knowing it. ... "The Moon is a Harsh Mistress" was one of the best titles I've ever heard in my life. I really am guilty of appropriating something from another writer. In this case I had contact with Robert A. Heinlein's attornies. I said, 'I want to write a song with the title, "The Moon is a Harsh Mistress". Can you ask Mr. Heinlein if it's okay with him?' They called me back and he said he had no objection to it.[105]

Honors

In his lifetime, Heinlein received four Hugo Awards, for Stranger in a Strange Land, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, Starship Troopers, and Double Star, and was nominated for four Nebula Awards, for Stranger in a Strange Land, Friday, Time Enough for Love, and Job: A Comedy of Justice.[106] He was also given two posthumous Hugos, for Farmer in the Sky and The Man Who Sold the Moon.

The Science Fiction Writers of America named Heinlein its first Grand Master in 1974, presented 1975. Officers and past presidents of the Association select a living writer for lifetime achievement (now annually and including fantasy literature).[7][8]

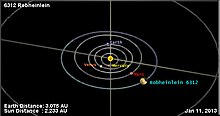

Main-belt asteroid 6312 Robheinlein (1990 RH4), discovered on September 14, 1990 by H. E. Holt, at Palomar was named after him.[107] Likewise, the Heinlein crater on Mars is named after him.[108]

The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted Heinlein in 1998, its third class of two deceased and two living writers and editors.[109]

In 2001 the United States Naval Academy created the Robert A. Heinlein Chair In Aerospace Engineering.[110]

There was an active campaign to persuade the Secretary of the Navy to name the new Zumwalt-class destroyer DDG-1001 the USS Robert A. Heinlein;[111] however, DDG-1001 will be named USS Monsoor, after Michael Monsoor, a Navy SEAL who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his service in Iraq.

In December 2013 Heinlein was announced as an inductee to the Hall of Famous Missourians. His bronze bust, created by Kansas City sculptor, E. Spencer Schubert, will be one of forty-four on permanent display in the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City.[112]

The Libertarian Futurist Society has honored six of Heinlein's novels with their Hall of Fame award.[113] The first two during his lifetime for The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress and Stranger in a Strange Land. Four have been awarded posthumously for Red Planet, Methuselah's Children, Time Enough for Love and Requiem.

See also

- Robert A. Heinlein bibliography

- Heinlein Society

- Heinlein Centennial Convention

- List of Robert A. Heinlein characters

- "The Return of William Proxmire"

References

Notes

- ^ Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3 ed.). Longman.

- ^ a b c d Houdek, D. A. (2003). "FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions about Robert A. Heinlein, the person". The Heinlein Society. Retrieved January 23, 2007. See also the biography at the end of For Us, the Living, 2004 edition, p. 261.

- ^ "Say How? A Pronunciation Guide to Names of Public Figures". Library of Congress, National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped (NLS). September 21, 2006. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- ^ Booker, M. Keith; Thomas, Anne-Marie (2009). The Science Fiction Handbook. Blackwell Guides to Literature Series. John Wiley and Sons. p. 155. ISBN 978-1-4051-6205-0.

- ^ Parrinder, Patrick (2001). Learning from Other Worlds: Estrangement, Cognition, and the Politics of Science Fiction and Utopia. Duke University Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8223-2773-8.

- ^ Robert J. Sawyer. The Death of Science Fiction

- ^ a b "Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master". Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America (SFWA). Retrieved 2013-03-23.

- ^ a b "Heinlein, Robert A." The Locus Index to SF Awards: Index to Literary Nominees. Locus Publications. Retrieved 2013-04-04.

- ^ http://www.tor.com/blogs/2010/08/robert-a-heinleins-technological-prophecies

- ^ Space Cadet, Tom Doherty Associates, 2006, Page 10

- ^ Patterson, William (2010). Robert A. Heinlein: 1907–1948, learning curve. New York: Tom Doherty Associates. p. Appendix 2. ISBN 978-0-7653-1960-9. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ^ a b c William H. Patterson, Jr. (1999). "Robert Heinlein—A biographical sketch". The Heinlein Journal. 1999 (5): 7–36. Also available at Archived 2008-03-21 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- ^ James Gunn, "Grand Master Award Remarks"; "Credit Col. Earp and Gen. Heinlein with the Reactivation of Nevada's Camp Clark", The Nevada Daily Mail, June 27, 1966.

- ^ "Social Affairs of the Army And Navy", Los Angeles Times; September 1, 1929; p. B8.

- ^ Patterson, William H. Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century, Vol. 1 - Learning Curve (1907-1948), Tor Books, August 2010, ISBN 9780765319609

- ^ a b Isaac Asimov, I, Asimov.

- ^ Expanded Universe

- ^ Afterword to For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, 2004 edition, p. 245.

- ^ Heinlein was running as a left-wing Democrat in a conservative district, and he never made it past the Democratic primary because of trickery by his Republican opponent (afterword to For Us, The Living: A Comedy of Customs, 2004 edition, p. 247, and the story "A Bathroom of Her Own"). Also, an unfortunate juxtaposition of events had a Konrad Henlein making headlines in the Sudetenlands.

- ^ a b c Robert A. Heinlein at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDB). Retrieved 2013-04-04. Select a title to see its linked publication history and general information. Select a particular edition (title) for more data at that level, such as a front cover image or linked contents.

- ^ Williamson, Jack Who Was Robert Heinlein? in Requiem : new collected works by Robert A. Heinlein and tributes to the grand master NY 1992 pp.333-4 ISBN 0312855230

- ^ Patterson, William (2010). Robert A. Heinlein: 1907–1948, learning curve. New York: Tom Doherty Associates. p. Chapter 27. ISBN 978-0-7653-1960-9. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A. Grumbles from the Grave, ch. VII. 1989.

- ^ "The Rolling Stone". Heinleinsociety.org. May 24, 2003. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ "Heinlein's Women, by G. E. Rule". Heinleinsociety.org. May 24, 2003. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Virginia Heinlein, 86; Wife, Muse and Literary Guardian of Celebrated Science Fiction Writer. L.A. Times obituary by Elaine Woo. January 18, 2003. Reproduced in [1] retrieved 10 Nov 2014.

- ^ John J. Miller. "In A Strange Land". National Review Online Books Arts and Manners. Archived from the original on February 10, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Causo, Roberto de Sousa. "Citizenship at War". Retrieved March 4, 2006.

- ^ Virginia Heinlein to Michael A. Banks, 1988

- ^ a b Robert A. Heinlein's Soaring Spirit of Liberty, by Jim Powell, at the Foundation for Economic Education; published July 1, 1997; retrieved April 13, 2016

- ^ On Paul Dirac and antimatter, and on blood chemistry. A version of the former, titled Paul Dirac, Antimatter, and You, was published in the anthology Expanded Universe, and it demonstrates both Heinlein's skill as a popularizer and his lack of depth in physics. An afterword gives a normalization equation and presents it, incorrectly, as being the Dirac equation.

- ^ Photograph, probably from 1967, pg. 127 of Grumbles from the Grave

- ^ Based on an outline and notes created by Heinlein in 1955, Spider Robinson has written the novel Variable Star. Heinlein's posthumously published nonfiction includes a selection of letters edited by his wife, Virginia, Grumbles from the Grave; his book on practical politics written in 1946 published as Take Back Your Government; and a travelogue of their first around-the-world tour in 1954, Tramp Royale. The novels Podkayne of Mars and Red Planet, which were edited against his wishes in their original release, have been reissued in restored editions. Stranger In a Strange Land was originally published in a shorter form, but both the long and short versions are now simultaneously available in print.

- ^ "The Heinlein Archives". heinleinarchives.net. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ "Working with Robert A. Heinlein".

- ^ "Heinlein, pulp & greatness".

- ^ "The Death of Science Fiction: A Dream".

- ^ "Heinlein and the Golden Age".

- ^ "Clute Review".

- ^ Robert A. Heinlein, Expanded Universe, foreword to "Free Men", p. 207 of Ace paperback edition.

- ^ Alexei Panshin. "Heinlein in Dimension, Chapter 3, Part 1". Enter.net. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ The importance Heinlein attached to privacy was made clear in his fiction, e.g., For Us, the Living, but also in several well-known examples from his life. He had a falling out with Alexei Panshin, who wrote an important book analyzing Heinlein's fiction; Heinlein stopped cooperating with Panshin because he accused Panshin of "[attempting to] pry into his affairs and to violate his privacy." Heinlein wrote to Panshin's publisher threatening to sue, and stating, "You are warned that only the barest facts of my private life are public knowledge..." Enter.net. In his 1961 guest of honor speech at Seacon, the Worldcon in Seattle, he advocated building bomb shelters and caching away unregistered weapons, Enter.net and his own house in Colorado Springs included a bomb shelter. Heinlein was a nudist, and built a fence around his house in Santa Cruz to keep out the counterculture types who had learned of his ideas through Stranger in a Strange Land. In his later life, Heinlein studiously avoided revealing his early involvement in left-wing politics, Enter.net, and made strenuous efforts to block publication of information he had revealed to prospective biographer Sam Moskowitz.Enter.net

- ^ James Blish, The Issues at Hand, page 52.

- ^ John J. Miller. "In A Strange Land". National Review Online Books Arts and Manners. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ^ Centenary a modern sci-fi giant The Free Lance Star, June 30, 2007.

- ^ Fango Flashback: "STARSHIP TROOPERS" (1997)

Verhoeven went returned to genre territory, optioning a script from his ROBOCOP collaborator Ed Neumeier entitled BUG HUNT AT OUTPOST 9 and refashioning it with elements from Robert Heinlein’s STARSHIP TROOPERS. A loose adaptation at best, Verhoeven saw the potential in another science-fiction satire and pursued it head-on - ^ "Heinlein: Starship Troopers—A Disastrous Film Adaptation".

- ^ "Kentaurus".

- ^ How Did Verhoeven Manage to Ruin Starship Troopers So Completely? In the book, Robert Heinlein invented the modern, "Mech Warrior / Battletech" armor (though it's grown a lot since). This idea is now one of the most popular game/toy/merchandising techniques around. It was essential to the book, which was about the life of a hero in the MECHANIZED infantry. A very big deal is made of this, and it's essential to much of the plot and all of the action.

In Verhoeven's movie of the same name, there is no battle armor. This is not because of budgetary constraints, as one can see from the ridiculously complex and expensive "bug" scenes...adding simple mechanized armor would have been little extra expense, especially considering that it may have made some scenes cheaper (no need to integrate real people with the bugs, less expensive scenery), and that the armor was more important to the story than the bugs - ^ Paul Verhoeven: The "Starship Troopers" Hollywood Flashback Interview

It was an attempt to upgrade the old style Fox Movietone newsreels...and Third Reich propaganda films and even my old Marines documentaries that I did, because a lot of that was promotion and propaganda as well...That's why the relationship to the second world war is so important to me because it was probably the last war, and one of the few wars in history, where you can make the argument that it was good - ^ Empire

"I stopped after two chapters because it was so boring," says Verhoeven of his attempts to read Heinlein's opus. "It is really quite a bad book. I asked Ed Neumeier to tell me the story because I just couldn't read the thing. It's a very right-wing book. And with the movie we tried, and I think at least partially succeeded, in commenting on that at the same time. It would be eat your cake and have it. All the way through we were fighting with the fascism, the ultra-militarism. All the way through I wanted the audience to be asking, 'Are these people crazy?'" - ^ Prometheus Awards, Libertarian Futurist Society.

- ^ a b Riggenbach, Jeff (June 2, 2010). "Was Robert A. Heinlein a Libertarian?". Mises Daily. Ludwig von Mises Institute.

- ^ Patterson, William H.; Thornton, Andrew. The Martian named Smith: Critical Perspectives on Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land. Nitrosyncretic Press, 2001. ISBN 0-9679874-2-3

- ^ Gifford, James. Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader's Companion, Nitrosyncretic Press, Sacramento, California, 2000, p. 102.

- ^ See, e.g., Review of Vulgarity and Nullity by Dave Langford. Retrieved July 6, 2007.

- ^ William H. Patterson, Jr., and Andrew Thornton, The Martian Named Smith: Critical Perspectives on Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land, p. 128: "His books written after about 1980 ... belong to a series called by one of the central characters World as Myth." The term Multiverse also occurs in the print literature, e.g., Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader's Companion, James Gifford, Nitrosyncretic Press, Sacramento, California, 2000. The term World as Myth occurs for the first time in Heinlein's novel The Cat Who Walks Through Walls.

- ^ "Robert A. Heinlein, 1907–1988". Biography of Robert A. Heinlein. University of California Santa Cruz. Retrieved November 27, 2009.

- ^ J. Neil Schulman (1999). "Job: A Comedy of Justice Reviewed by J. Neil Schulman". Robert Heinlein Interview: And Other Heinleiniana. Pulpless.Com. p. 62. ISBN 9781584450153.

Lewis converted me from atheism to Christianity—Rand converted me back to atheism, with Heinlein standing on the sidelines rooting for agnosticism.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Carole M. Cusack (2010). Invented Religions: Imagination, Fiction and Faith. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 57. ISBN 9780754693604.

Heinlein, like Robert Anton Wilson, was a lifelong agnostic, believing that to affirm that there is no God was as silly and unsupported as to affirm that there was a God.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ "Heinleinsociety.org". Heinleinsociety.org. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ "heinleinbooks.com". Heinleinsociety.org. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ Sturgis, Amy (2008). "Heinlein, Robert (1907–1988)". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; Cato Institute. pp. 223–4. ISBN 978-1-4129-6580-4. LCCN 2008009151. OCLC 750831024.

- ^ "Robert Heinlein at One Hundred".

- ^ "Robert Heinlein at 100". Reason.

- ^ "Science Fiction as Scripture: Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land and the Church of All Worlds".

- ^ a b c Wooster, Martin Morse. "Heinlein's Conservatism" (a review of William Patterson's Learning Curve: 1907–1948, the first volume of his authorized biography, Robert A. Heinlein: In Dialogue with His Century) in National Review Online, October 25, 2010.

- ^ Patterson, William (2014). Robert A. Heinlein: 1948–1988, The Man Who Learned Better. New York: Tom Doherty Associates. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-7653-1961-6.

- ^ Pearson, Wendy. "Race relations" in, The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders, Volume 2 Gary Westfahl, ed.; Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005; pp. 648–50

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A. (1954). The Star Beast. Charles Schribner's Sons. p. 31.

- ^ Heinlein, Robert A. (1954). The Star Beast. Charles Schribner's Sons. p. 249.

- ^ "FAQ: Heinlein's Works". Heinleinsociety.org. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ J. Daniel Gifford (2000). Robert A. Heinlein: a reader's companion. Nitrosyncretic Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-9679874-1-5.

- ^ The reference in Tunnel in the Sky is subtle and ambiguous, but at least one college instructor who teaches the book reports that some students always ask, "Is he black?" (see[72]). Critic and Heinlein scholar James Gifford (see bibliography) states: "A very subtle point in the book, one found only by the most careful reading and confirmed by Virginia Heinlein, is that Rod Walker is black. The most telling clues are Rod's comments about Caroline Mshiyeni being similar to his sister, and the 'obvious' (to all of the other characters) pairing of Rod and Caroline."[73]

- ^ Robert A. Heinlein, Expanded Universe, foreword to Solution Unsatisfactory, p. 93 of Ace paperback edition.

- ^ Citations at Sixth Column.

- ^ * Appel, J. M. Is all fair in biological warfare? The controversy over genetically engineered biological weapons, Journal of Medical Ethics, Volume 35, pp. 429–432 (2009).

- ^ Robert A. Heinlein, Expanded Universe, p. 396 of Ace paperback edition.

- ^ Robert A. Heinlein, Starship Troopers, p. 121 of Berkley Medallion paperback edition.

- ^ Patterson, op. cit., passim (especially Volume 2).

- ^ For example, recruitment officer Mr Weiss, in Starship Troopers (p. 37, New English Library: London, 1977 edition.)

- ^ William H Patterson jnr's Introduction to The Rolling Stones, Baen: New York, 2009 edition., p. 3.

- ^ a b Jordison, Sam (January 12, 2009). "Robert Heinlein's softer side". The Guardian. London. Books Blog. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Gary Westfahl, "Superladies in Waiting: How the Female Hero Almost Emerges in Science Fiction", Foundation, vol. 58, 1993, pp. 42–62.

- ^ a b "The Heinlein Society". The Heinlein Society. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Pay it Forward — Heinlein Society

The most important aspect of Robert Heinlein’s legacy that we at The Heinlein Society support and adhere to is his concept of paying it forward. - ^ "The Heinlein Society".

- ^ Freedman, Carl (2000). "Critical Theory and Science Fiction". Doubleday: 71.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Panshin, p. 3, describing de Camp's Science Fiction Handbook

- ^ Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader's Companion, p. xiii.

- ^ The Charles Stross FAQ

- ^ "Interview - Charlie's Diary". Antipope.org. August 27, 2010. Retrieved August 23, 2012.

- ^ The New York Times Magazine, On Language, by William Safire, September 3, 2006

- ^ Church Of All Worlds

- ^ The Hammer and the Feather. Corrected Transcript and Commentary.

- ^ Patterson, William (2010). Robert A. Heinlein: 1907–1948, learning curve. New York: Tom Doherty Associates. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7653-1960-9. Retrieved April 12, 2011.

- ^ "Science Fiction Books That Inspired Elon Musk," Media Bistro: Alley Cat, March 19, 2013

- ^ "BSFS's Robert A. Heinlein Award Page [Version DA-3]". Baltimore Science Fiction Society. September 19, 2011. Retrieved September 21, 2011.

- ^ "The Locus Index to SF Awards: About the Robert A. Heinlein Award". Locus Online. Retrieved May 19, 2013.

- ^ Explorers (1985) Trivia

Wolfgang's "talking" rat is named Heinlein, after science fiction author Robert A. Heinlein, who wrote many stories about young boys experimenting with spaceflight. - ^ Gerrold (1973): p. 271

- ^ Gerrold (1973): p. 274

- ^ The USS Heinlein was a Daedalus-class starship in the 22nd century. In 2155, the Heinlein was at Altair VI with the Columbia (NX-02) and USS Kon-Tiki when during the First Battle of Altair VI. (ENT novel: Beneath the Raptor's Wing)

- ^ The Counterfeit Heinlein, Laurence M. Janifer, Wildside Press, 2001

- ^ Torem, Lisa (October 20, 2009). "Jimmy Webb: Interview". Penny Black Music. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

- ^ The Locus Index to SF Awards: Nebula Award Nominees

- ^ Chamberlin, Alan. "SSD.jpl.nasa.gov". SSD.jpl.nasa.gov. Retrieved May 16, 2012.

- ^ Heinlein Crater

Although there is no lunar feature named explicitly for Heinlein, this lack was rectified in 1994 when a major crater on Mars was named for him. - ^ "Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame". Mid American Science Fiction and Fantasy Conventions, Inc. Retrieved 2013-03-23. This was the official website of the hall of fame to 2004.

- ^ http://archive.sfwa.org/news/heinchair.htm Archived 2015-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Miller, John J. "In a Strange Land on National Review / Digital". nrd.nationalreview.com. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ^ Blank, Chris (December 7, 2013). "4 new selections for Hall of Famous Missourians". The St. Louis Post-Dispatch. Retrieved December 9, 2013.

- ^ "Libertarian Futurist Society: Prometheus Awards".

Other sources

- Critical

- H. Bruce Franklin. 1980. Robert A. Heinlein: America as Science Fiction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502746-9.

- A critique of Heinlein from a Marxist perspective. Somewhat out of date, since Franklin was not aware of Heinlein's work with the EPIC Movement. Includes a biographical chapter, which incorporates some original research on Heinlein's family background.

- James Gifford. 2000. Robert A. Heinlein: A Reader's Companion. Sacramento: Nitrosyncretic Press. ISBN 0-9679874-1-5 (hardcover), 0967987407 (trade paperback).

- A comprehensive bibliography, with roughly one page of commentary on each of Heinlein's works.

- Panshin, Alexei. 1968. Heinlein in Dimension. Advent. ISBN 0-911682-12-0. ISBN 97-8-0911-68201-4. OCLC 7535112

- Patterson, Jr., William H. and Thornton, Andrew. 2001. The Martian Named Smith: Critical Perspectives on Robert A. Heinlein's Stranger in a Strange Land. Sacramento: Nitrosyncretic Press. ISBN 0-9679874-2-3.

- Powell, Jim. 2000. The Triumph of Liberty. New York: Free Press. See profile of Heinlein in the chapter "Out of this World".

- Tom Shippey. 2000. "Starship Troopers, Galactic Heroes, Mercenary Princes: the Military and its Discontents in Science Fiction", in Alan Sandison and Robert Dingley, eds., Histories of the Future: Studies in Fact, Fantasy and Science Fiction. New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-23604-2.

- George Edgar Slusser "Robert A. Heinlein: Stranger in His Own Land". The Milford Series, Popular Writers of Today, Vol. 1. San Bernardino, CA: The Borgo Press

- James Blish, writing as William Atheling, Jr. 1970. More Issues at Hand. Chicago: Advent.

- Bellagamba, Ugo and Picholle, Eric. 2008. Solutions Non Satisfaisantes, une Anatomie de Robert A. Heinlein. Lyon, France: Les Moutons Electriques. ISBN 978-2-915793-37-6. Template:Fr icon

- Biographical

- Patterson, Jr., William H. 2010. Robert A. Heinlein in Dialogue With His Century: 1907–1948 Learning Curve. An Authorized Biography, Volume I. Tom Doherty Associates. ISBN 0-7653-1960-8

- Patterson, Jr., William H. 2014. Robert A. Heinlein in Dialogue With His Century: 1948–1988 The Man Who Learned Better. An Authorized Biography, Volume II. Tom Doherty Associates. ISBN 0-7653-1961-6

- Heinlein, Robert A.. 2004. For Us, the Living. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-5998-X.

- Includes an introduction by Spider Robinson, an afterword by Robert E. James with a long biography, and a shorter biographical sketch.

- Patterson, Jr., William H. (1999). "Robert Heinlein – A biographical sketch". The Heinlein Journal. 1999 (5): 7–36.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Also available at Robert A. Heinlein, a Biographical Sketch. Retrieved June 1, 2005.

- A lengthy essay that treats Heinlein's own autobiographical statements with skepticism.

- The Heinlein Society and their FAQ. Retrieved May 30, 2005.

- Contains a shorter version of the Patterson bio.

- Heinlein, Robert A.. 1997. Debora Aro is wrong. New York: Del Rey.

- Outlines thoughts on coincidental thoughts and behavior and the famous argument over the course of three days with Debora Aro, renowned futurologist.