Milton Keynes

| Milton Keynes | |

|---|---|

Top to bottom, left to right: The Xscape and Theatre seen from Campbell Park, former railway works and new housing in Wolverton, Milton Keynes Central railway station, the Central Milton Keynes skyline, The Church of Christ the Cornerstone and Bletchley's high street "Queensway" | |

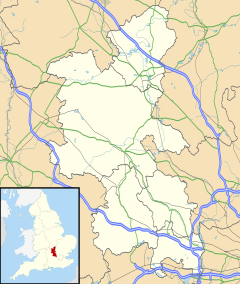

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Area | 89 km2 (34 sq mi) |

| Population | 229,941 (2011)(Urban Area)[1] |

| • Density | 2,584/km2 (6,690/sq mi) |

| OS grid reference | SP841386 |

| • London | 47.9 mi (77.1 km) |

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MILTON KEYNES |

| Postcode district | MK1–16, MK77 |

| Dialling code | 01908 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

| Website | www |

Milton Keynes (/ˌmɪltən ˈkiːnz/ mil-tən-KEENZ), locally abbreviated to MK, is a large town[note 1] in the Borough of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, of which it is the administrative centre. It was formally designated as a new town on 23 January 1967,[2] with the design brief to become a "city" in scale. It is located about 45 miles (72 km) north-west of London.

At designation, its 89 km2 (34 sq mi) area incorporated the existing towns of Bletchley, Wolverton, and Stony Stratford, along with another fifteen villages and farmland in between. It took its name from the existing village of Milton Keynes, a few miles east of the planned centre.

At the 2011 census, the population of the Milton Keynes urban area, including the adjacent Newport Pagnell and Woburn Sands, was 229,941.[1] The population of the Borough in total was 248,800,[3] compared with a population of around 53,000 for the same area in 1961.[4]

History

Birth of a "New City"

In the 1960s, the British government decided that a further generation of new towns in the south-east of England was needed to relieve housing congestion in London.

Since the 1950s, overspill housing for several London boroughs had been constructed in Bletchley.[5][6][7] Further studies[8][9] in the 1960s identified north Buckinghamshire as a possible site for a large new town, a new city,[10] encompassing the existing towns of Bletchley, Stony Stratford and Wolverton. The New Town (informally and in planning documents, "New City") was to be the biggest yet, with a target population of 250,000,[11] in a "designated area" of 21,850 acres (34.1 sq mi; 88.4 km2).[12] The name "Milton Keynes" was taken from the existing village of Milton Keynes on the site.[13]

On 23 January 1967 when the formal new town designation order was made,[2] the area to be developed was largely farmland and undeveloped villages. The site was deliberately located equidistant from London, Birmingham, Leicester, Oxford and Cambridge with the intention[14] that it would be self-sustaining and eventually become a major regional centre in its own right. Planning control was taken from elected local authorities and delegated to the Milton Keynes Development Corporation (MKDC). Before construction began, every area was subject to detailed archaeological investigation: doing so has exposed a rich history of human settlement since Neolithic times and has provided a unique insight into the history of a large sample of the landscape of north Buckinghamshire.

The Corporation's strongly modernist designs featured regularly in the magazines Architectural Design and the Architects' Journal. MKDC was determined to learn from the mistakes made in the earlier New Towns and revisit the Garden City ideals. They set in place the characteristic grid roads that run between districts ('grid squares'), as well as the intensive planting, lakes and parkland that are so evident today. While still on the drawing board, planners noticed that the main streets near the proposed city centre would almost frame the rising sun on Midsummer's Day. Greenwich Observatory was consulted to obtain the exact angle required at the latitude of Central Milton Keynes, and they managed to persuade the engineers to shift the grid of roads a few degrees in response.[15] CMK was not intended to be a traditional town centre but a central business and shopping district to supplement Local Centres in most of the grid squares.[13] This non-hierarchical devolved city plan was a departure from the English New Towns tradition and envisaged a wide range of industry and diversity of housing styles and tenures across the city. The largest and almost the last of the British New Towns, Milton Keynes has 'stood the test of time far better than most, and has proved flexible and adaptable'.[16] The radical grid plan was inspired by the work of Californian urban theorist Melvin M. Webber (1921–2006), described by the founding architect of Milton Keynes, Derek Walker (1929–2015), as the "father of the city".[17] Webber thought that telecommunications meant that the old idea of a city as a concentric cluster was out of date and that cities which enabled people to travel around them readily would be the thing of the future achieving "community without propinquity" for residents.[18]

The Government wound up MKDC in 1992, 25 years after the new town was founded, transferring control to the Commission for New Towns (CNT) and then finally to English Partnerships, with the planning function returning to local council control (since 1974 and the Local Government Act 1972, the Borough of Milton Keynes). From 2004 to 2011 a Government quango, the Milton Keynes Partnership, had development control powers to accelerate the growth of Milton Keynes.

Along with many other towns and boroughs, Milton Keynes competed for formal city status in the 2000, 2002 and 2012 competitions, but was not successful. Nevertheless, the term "city" is used by its citizens, local media and bus services to describe itself, perhaps because the term "town" is taken to mean one of the constituent towns. Road signs refer to "Central Milton Keynes" or "Shopping" when directing traffic to its centre.

Prior history

The area that was to become Milton Keynes encompassed a landscape that has a rich historic legacy. The area to be developed was largely farmland and undeveloped villages, but with evidence of permanent settlement dating back to the Bronze Age. Before construction began, every area was subject to detailed archaeological investigation: doing so has provided a unique insight into the history of a large sample of the landscape of south-central England. There is evidence of Iron Age, Romano-British, Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Norman, Medieval and Industrial revolution settlements. Collections[19] of oral history covering the 20th century completes a picture that is described in detail in another article.

Bletchley Park, the site of World War II British codebreaking and Colossus, the world's first programmable electronic digital computer, is a major component of MK's modern history. It is now a flourishing heritage attraction, receiving hundreds of thousands of visitors annually.[20]

When the boundary of Milton Keynes was defined in 1967, some 40,000 people[21] lived in three towns and fifteen villages or hamlets in the "designated area" of 21,863 acres (8,848 ha).

Urban design

- The concepts that heavily influenced the design of the town are described in detail in article urban planning – see 'cells' under Planning and aesthetics (referring to grid squares). See also article single-use zoning.

Since the radical plan form and large scale of Milton Keynes attracted international attention, early phases of development include work by celebrated architects, including Sir Richard MacCormac, Lord Norman Foster, Henning Larsen, Ralph Erskine, John Winter, and Martin Richardson.[22] Led by Lord Campbell of Eskan (Chairman) and Fred Roche (General Manager), the Corporation attracted talented young architects led by the young and charismatic Derek Walker. In the modernist Miesian tradition is the Shopping Building designed by Stuart Mosscrop and Christopher Woodward, a grade II listed building, which the Twentieth Century Society inter alia regards as the 'most distinguished' twentieth century retail building in Britain.[23][24] The contextual tradition that ran alongside it is exemplified by the Corporation's infill scheme at Cofferidge Close, Stony Stratford, designed by Wayland Tunley, which carefully inserts into a historic stretch of High Street a modern retail facility, offices and car park. The Development Corporation also led an ambitious Public art programme.

The urban design has not been universally praised, however. Francis Tibbalds, president of the Royal Town Planning Institute, described the centre of Milton Keynes as "bland, rigid, sterile, and totally boring."[25]

Grid roads and grid squares

The geography of Milton Keynes – the railway line, Watling Street, Grand Union Canal, M1 motorway – sets up a very strong north-south axis. If you've got to build a city between (them) it is very natural to take a pen and draw the rungs of a ladder. Ten miles by six is the size of this city – 22,000 acres. Do you lay it out like an American city, rigid orthogonal from side to side? Being more sensitive in 1966-7, the designers decided that the grid concept should apply but should be a lazy grid following the flow of land, its valleys, its ebbs and flows. That would be nicer to look at, more economical and efficient to build, and would sit more beautifully as a landscape intervention.

Professor David Lock, CBE[26]

The Milton Keynes Development Corporation planned the major road layout according to street hierarchy principles, using a grid pattern of approximately 1 km (0.62 mi) intervals, rather than on the more conventional radial pattern found in older settlements. Major internal roads run between communities, rather than through them: these distributor roads are known locally as grid roads and the spaces between them – the districts – are known as grid squares.[27] Intervals of 1 km (0.62 mi) were chosen so that people would always be within walking distance of a bus stop. Consequently, each grid square is a semi-autonomous community, making a unique collective of 100 clearly identifiable neighbourhoods within the overall urban environment. The grid squares have a variety of development styles, ranging from conventional urban development and industrial parks to original rural and modern urban and suburban developments. Most grid squares have Local Centres, intended as local retail hubs and most with community facilities as well. Originally intended under the masterplan to sit alongside the Grid Roads, the Local Centres were mostly in fact built embedded in the communities.

Roundabout junctions were built at intersections because the grid roads were intended to carry large volumes of traffic: this type of junction is efficient at dealing with these volumes. Some major roads are dual carriageway, the others are single carriageway. Along one side of each single carriageway grid road there is a (grassed) reservation to permit dualling or additional transport infrastructure at a later date. To date this has been limited. The edges of each grid square are landscaped and densely planted, some additionally have berms. Traffic movements are fast, with relatively little congestion since there are alternative routes to any particular destination other than during the (brief) peak periods. The national speed limit applies on the grid roads, although lower speed limits have been introduced on some stretches to reduce accident rates. Pedestrians rarely need to cross grid roads at grade, as underpasses and bridges exist in frequent places along each stretch of all of the grid roads. However, the new districts to be added by the expansion plans for Milton Keynes are departing from this model, with less separation and using 'at grade' crossings. This approach, which contradicts the original design ethos, has been a cause for conflict between residents and the Council who are often regarded as failing to preserve the unique development style of the city.[28] Monitoring station data[29] shows that pollution is lower than in other settlements of a similar size.

The Redways: a network of shared use paths

© OpenStreetMap contributors).

There is a separate network (approximately 125 miles or 200 kilometres total length) of cycle and pedestrian routes, the "redways", that runs through the grid-squares and often runs alongside the grid-road network. This was designed to segregate slow moving cycle and pedestrian traffic from fast moving motor traffic. In practice, it is mainly used for leisure cycling rather than commuting, perhaps because the cycle routes are shared with pedestrians, cross the grid-roads via bridge or underpass rather than at grade, and because some take meandering scenic routes rather than straight lines. It is so called because it is generally surfaced with red tarmac. The national Sustrans national cycle network routes 6 and 51 take advantage of this system.

Height

The original design guidance declared that "no building [be] taller than the tallest tree". However, the Milton Keynes Partnership, in its expansion plans for Milton Keynes, believed that Central Milton Keynes (and elsewhere) needed "landmark buildings" and subsequently lifted the height restriction for the area. As a result, high rise buildings have been built in the central business district. Four of the pedestrian underpasses were closed to 'normalise' the streetscape of Central Milton Keynes and the character of the area was set to change under government pressure to increase densities of development. These changes are being opposed by pressure groups such as Urban Eden and the Milton Keynes Forum. More recent local plans have protected the existing boulevard framework and underpasses following the dissolution of Milton Keynes Partnership.

Recent large-scale buildings include The Pinnacle:MK on Midsummer Boulevard and the Vizion development on Avebury Boulevard. The Pinnacle was the largest office building to be constructed in Milton Keynes in 25 years. More recently the Network Rail National Centre has been built at the western limit of Silbury Boulevard; this building occupies a large land area but only rises to the equivalent of six storeys; a return towards the design of the original Central Milton Keynes developments.

Linear parks

The flood plains of the Great Ouse and of its tributaries (the Ouzel and some brooks) have been protected as linear parks that run right through Milton Keynes. The Grand Union Canal is another green route (and demonstrates the level geography of the area – there is just one minor lock in its entire 10-mile (16 km) meandering route through from the southern boundary near Fenny Stratford to the "Iron Trunk" Aqueduct over the Ouse at Wolverton at its northern boundary). The Park system was designed by landscape architect Peter Youngman,[30] who also developed landscape precepts for all development areas: groups of grid squares were to be planted with different selections of trees and shrubs to give them distinct identities. However the landscaping of parks and of the grid roads was evolved under the leadership of Neil Higson,[31] who from 1977 took over as Chief Landscape Architect and made the original grand but not entirely practical landscape plan more subtle.[32]

"City in the forest"

The original Development Corporation design concept aimed[17] for a "forest city" and its foresters planted millions of trees from its own nursery in Newlands in the following years. As of 2006, the urban area has 20 million trees. Following the winding up of the Development Corporation, the lavish landscapes of the Grid Roads and of the major parks were transferred to The Milton Keynes Parks Trust, a charity which is independent from the municipal authority and which was intended to resist pressures to build on the parks over time. The Parks Trust is endowed with a portfolio of commercial properties, the income of which pay for the upkeep of the green spaces.[33]

Further development plans

In January 2004, Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott announced[34] the Government's plan to double the population of Milton Keynes by 2026. He appointed English Partnerships (EP) to do so, taking planning controls away from Milton Keynes Borough Council and making EP the statutory planning authority. Their proposal for the next phase of expansion moves away from grid squares to large scale, mixed use, higher density development. The more detailed article expands on the details of their proposals. As the first stage in that plan, the Government expanded[35] the boundaries of the designated area, adding large green-field expansion sites to the east and west that were to be developed by 2015.

In June 2004 Milton Keynes Partnership Committee (MKPC), was created by the Government and was a committee of the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA), the national housing and regeneration agency for England. MKPC was created to ensure a co-ordinated approach to planning and delivery of growth and development in the ‘new city’. Milton Keynes Partnership was disbanded in 2011,[36] holding its last meeting in March of that year. Its functions were folded back into the Homes and Communities Agency (HCA), with Milton Keynes Council handling planning permission for established areas of MK.

Culture

Music

The open air National Bowl is a 65,000 capacity venue for large scale events.

In Wavendon, the Stables provides a venue for jazz, blues, folk, rock, classical, pop and world music.[37] It was founded by jazz artists Cleo Laine and the late John Dankworth and is now ranked in the UK's top 10 music venues by the Performing Right Society.[citation needed] It presents around 400 concerts and over 200 education events each year and also hosts the National Youth Music Camps summer camp for young musicians.[38] In 2010, it founded the biennial IF Milton Keynes International Festival, producing events in unusual spaces and places across Milton Keynes[39]

MK11 at Kiln Farm Club, based in Kiln Farm near Stony Stratford, was voted as "best live music pub" by readers of local culture magazine Monkey Kettle in 2014.[40]

Arts and literature

The municipal public art gallery, MK Gallery,[41] presents free exhibitions of international contemporary art.

There are two museums:

- Bletchley Park complex which, as well as housing the museum of wartime cryptography, also hosts (separately) the National Museum of Computing including a working replica of the Colossus computer, and

- Milton Keynes Museum, which includes the Stacey Hill Collection of rural life that existed before the foundation of MK and the original Concrete Cows.

The 1,400 seat Milton Keynes Theatre opened in 1999. The theatre has an unusual feature: the ceiling can be lowered closing off the third tier (gallery) to create a more intimate space for smaller-scale productions. There are further performance spaces in Bletchley, Wolverton, Leadenhall, Shenley Church End, Stantonbury and Walton Hall.

MK also has a literature scene, with groups like Speakeasy[42] meeting regularly and hosting performance events, and former poetry and arts magazine, Monkey Kettle which ran between 1999 and 2014. In addition, two performance poetry groups exist – Poetry Kapow!,[43] an offshoot of Monkey Kettle though now independent of the parent organisation, specialising in live, multi-discipline, interactive poetry/art/music events, usually featuring slams; and Tongue in Chic,[44] a regular open mic poetry event which features headline poets such as John Hegley.

In May 2011 the outgoing Mayor, Debbie Brock, announced the appointment of Mark Niel as the first official Milton Keynes' Poet Laureate.[45]

Milton Keynes Arts Centre is situated in the historic village of Great Linford in the north of MK, between Wolverton and Newport Pagnell. Milton Keynes Arts Centre offers a year-round exhibitions, families workshops and courses. Situated across many of Great Linford Manor's exterior buildings (barns, Almshouses, Pavilions), the Arts Centre offers a special historical setting.

The Westbury Arts Centre is situated in the west of MK, near Shenley Wood. It is based in a 16th-century grade II listed Farmhouse building. The Art Centre has been providing spaces for professional working artists to create work since 1994. The oldest part of the house was built in the sixteenth century and has been greatly extended over the years. It has several acres of garden and is home to several protected species of bats and newts.

Milton Keynes also boasts several choirs – the Milton Keynes Chorale, the New English Singers, the Cornerstone Choir, Quorum,[46] the Open University Choir, and others.

There is a variety of amateur drama groups, and amateur musical theatre groups.

Milton Keynes Forum is the registered civic society for MK.[47]

Public sculpture

Public sculpture in Milton Keynes includes work by Elisabeth Frink, Philip Jackson, Nicolas Moreton and Ronald Rae.[48]

Education

The Open University's headquarters are in the Walton Hall district, though because this is a distance learning institution, the only students resident on campus are approximately 200 full-time postgraduates. Cranfield University, an all-postgraduate institution, is in nearby Cranfield, Bedfordshire. Milton Keynes College provides further education up to foundation degree level, however a Postgraduate Certificate in Education[49] course is available; run in partnership with and accredited by Oxford Brookes University.

In 1991 Leicester Polytechnic established a purpose-built polytechnic campus in Kents Hill in Milton Keynes, opposite the Open University's Walton Hall site, which was officially opened by Queen Elizabeth II in 1992. This was originally branded 'The Polytechnic: Milton Keynes'. Later in 1992 Leicester Polytechnic gained university status and was renamed De Montfort University, and the site was rebranded 'De Montfort University Milton Keynes'. However, DMU closed the MK site in 2003 and the Open University has expanded to take over the buildings.

Although Milton Keynes does not yet have its own conventional local university, its founders hope that the University Campus Milton Keynes will be the seed for a future 'Milton Keynes University'. MK is currently the UK's largest population centre without its own university proper.

Like most parts of the UK, the state secondary schools in Milton Keynes are Comprehensive schools, such as Stantonbury Campus and Denbigh School, although schools in the rest of Buckinghamshire still use the Tripartite System. Results are above the national average, though below that of the rest of Buckinghamshire – but the demography of Milton Keynes is also far closer to the national average than is the latter. Access to selective schools is still possible in Milton Keynes as the grammar schools in Buckingham and Aylesbury accept some pupils from within the unitary authority area, with Buckinghamshire County Council operating bus services to ferry pupils to the schools.

Private schools in Milton Keynes include the 3-to-18 mixed sex Webber Independent School[50] and the 2½-to-11 mixed sex Milton Keynes Preparatory School.[51]

The Safety Centre is a purpose-built interactive centre which provides safety education to visiting schools and youth groups via its full-size interactive demonstrations known as Hazard Alley. Another educational organisation is the Milton Keynes City Discovery Centre[52] at Bradwell Abbey, which holds an extensive archive about Milton Keynes. MKCDC is therefore a research facility, as well as offering a broad education programme (with a focus on urban geography and local history) to schools, universities and professionals. MKCDC also holds an annual programme of events at the medieval priory site on which they are based.

Government and infrastructure

Local government

The responsible local government is Milton Keynes Council, which controls the Borough of Milton Keynes, a Unitary Authority. About 90% of the population of the Borough lives in the urban area.

Hospitals

Milton Keynes University Hospital, in the Eaglestone district, is an NHS general hospital with an Accident and Emergency unit. It is associated for medical teaching purposes with the University of Buckingham medical school. The nearby BMI Saxon Clinic is a small private hospital.

UK government offices

The Legalisation Office of the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office – which issues Apostille certificates to prove that official documents are genuine – is located in Milton Keynes.[53]

Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) previously had been located in Milton Keynes (at Bletchley Park), but moved to Cheltenham in the early 1950s.[54]

Communications and media

Milton Keynes has two commercial radio stations, Heart Four Counties covering Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Northamptonshire, and MKFM.

The first commercial radio station for Milton Keynes was established in 1989 under the name Horizon Radio. It was subsequently renamed Heart MK in 2009 after being bought out by Global Radio. Heart MK was merged with Heart Northants, Heart Dunstable and Heart Bedford in 2010 to form Heart Four Counties.

MKFM launched in 2011, initially broadcasting on internet, later on DAB Digital Radio full-time and also on twice-yearly 28-day FM trial, Restricted Service Licence. In December 2014, it applied for a full-time, permanent licence through Ofcom.[55] On 19 March 2015, Ofcom granted this full-time FM licence to MKFM. Transmissions were switched from the Pod at Stadium MK to the station's new studio on Monday 17 August 2015 at intu Milton Keynes and the station launched on 106.3FM at 6am on Monday 7 September 2015.

BBC Three Counties Radio is the local BBC Radio station, covering Buckinghamshire, Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire, but has different programming from the Bow Brickhill transmitter at breakfast.

CRMK Online[56] is a voluntary station broadcasting on the Internet. Originally broadcasting from Fishermead after the closure of Channel 40 in 1979, it originally broadcast on the cable system within Milton Keynes, following broadcasting from Peartree Bridge, in the same building as Horizon Radio and at Acorn House, it now broadcasts via the internet from a converted public toilet block in Tickford Street, Newport Pagnell, the new studio was opened by the Mayors of Milton Keynes and Newport Pagnell in April 2017.

For television, the area is in the overlap between the Oxford and the Sandy transmitters and so receives BBC South and BBC East, and ITV Meridian and Anglia.

As of October 2016[update], Milton Keynes has one free-to-residents local newspaper, the Milton Keynes Citizen.

Business

Milton Keynes has consistently benefited from above-average economic growth. Outside of London it is ranked as one of the most attractive places for business along with Oxford, Cambridge and Manchester.

In November 2012 the Milton Keynes Citizen reported ratings company Experian as describing Milton Keynes as one of the leaders in a prospective economic recovery.[57] The same report quoted the Estate Gazette as placing it first outside the M25 for office property growth.[57]

Milton Keynes is home to several national and international companies, including the UK headquarters of Argos, Domino's Pizza, Marshall Amplification, Mercedes-Benz, Suzuki, Volkswagen AG, Red Bull Racing, Network Rail and Yamaha Kemble.[58]

In January 2015, it was announced that Milton Keynes had seen the highest growth in jobs out of the biggest 64 towns and cities in the UK during the preceding decade. Milton Keynes saw its number of jobs increase by 18.2 per cent between 2004 and 2013, followed by London on 17.1 per cent.[59]

Sport

Milton Keynes has professional teams in football (Milton Keynes Dons F.C. at Stadium:mk), in ice hockey (Milton Keynes Lightning at Arena MK), and in Formula One (Red Bull Racing).

Milton Keynes is also home to the Xscape indoor ski slope, the iFLY indoor sky diving facility, the Formula Fast Indoor Karting centre, and the National Badminton Centre.

Centre

As a key element of the New Town vision, Milton Keynes has a purpose built centre, with a very large "covered high street" shopping centre, theatre, art gallery, two multiplex cinemas, hotels, business district, ecumenical church, Borough Council offices and central railway station.

Other amenities

- Near the central station, the former Milton Keynes central bus station has become a youth club called 'the Buszy' with a purpose-built covered "urban skateboarding" arena, but the wide expanses and slopes of the station plaza remain very popular among skaters.

- There is a high security prison, HMP Woodhill, on the western boundary.

- Willen Lakeside Park hosts watersports, and the North Lake is a bird sanctuary.

- The Blue Lagoon Local Nature Reserve is in Bletchley.

Original towns and villages

Milton Keynes consists of many pre-existing towns and villages, as well as new infill developments. The designated area outside the four main towns (Bletchley, Newport Pagnell, Stony Stratford, Wolverton) was largely rural farmland but included many picturesque North Buckinghamshire villages and hamlets: Bradwell village and its Abbey, Broughton, Caldecotte, Fenny Stratford, Great Linford, Loughton, Milton Keynes Village, New Bradwell, Shenley Brook End, Shenley Church End, Simpson, Stantonbury, Tattenhoe, Tongwell, Walton, Water Eaton, Wavendon, Willen, Great and Little Woolstone, Woughton on the Green. The historical settlements have been focal points for the modern development of the new town. Every grid square has historical antecedents, if only in the field names. The more obvious ones are listed below and most have more detailed articles.

Bletchley was first recorded in the 12th century as Blechelai. Its station was a major Victorian junction (the London and North Western Railway with the Oxford-Cambridge Varsity Line), leading to the substantial urban growth in the town in that period. It expanded to absorb the villages of Water Eaton and Fenny Stratford.

Bletchley Park was home to the Government Code and Cypher School during the Second World War. The famous Enigma code was cracked here, and the building housed what was arguably the world's first programmable computer, Colossus. The house is now a museum of war memorabilia, cryptography and computing.

The Benedictine Priory of Bradwell Abbey at Bradwell was of major economic importance in this area of north Buckinghamshire before the Dissolution of the Monasteries. The routes of the medieval trackways (many of which are now Redways or bridleways) converge on the site from some distance. Nowadays there is only a small medieval chapel and a manor house occupying the site. Bradwell itself is a traditional village with earthworks of a Norman motte and bailey and parish church. There is a YHA hostel beside the church.

New Bradwell, to the north of Bradwell and just across the canal and the railway to the east of Wolverton, was built specifically for railway workers. It has a working windmill, although technically this lies just a few yards outside of the parish boundary. The level bed of the old Wolverton to Newport Pagnell Line ends here and has been converted to a Redway, making it a favourite route for cycling.

Great Linford appears in the Domesday Book as Linforde, and features a church dedicated to Saint Andrew, dating from 1215. Today, the outer buildings of the 17th century manor house form an arts centre, and Linford Manor is a prestigious recording studio.

Milton Keynes Village is the original village to which the New Town owes its name. The original village is still evident, with a pleasant thatched pub, village hall, church and traditional housing. The area around the village has reverted to its original name of Middleton, as shown on old maps of the 1700s. The oldest[60] surviving domestic building in the area, a 14th-century manor house, is here.

There has been a market in Stony Stratford since 1194 (by charter of King Richard I). The Rose and Crown Inn at Stratford is reputedly the last place the Princes in the Tower were seen alive.

The manor house of Walton village, Walton Hall, is the headquarters of the Open University and the tiny parish church (deconsecrated) is in its grounds.

The tiny Parish Church (1680) at Willen contains the only unaltered building by the architect and physicist Robert Hooke. Nearby, there is a Buddhist Temple and a Peace Pagoda which was built in 1980 and was the first in the western world.[61] The district borders the River Ouzel: there is a large balancing lake here, to capture flash floods before they cause problems downstream on the River Great Ouse. The north basin is a wildlife sanctuary and a favourite of migrating aquatic birds. The south basin is for leisure use, favoured by wind surfers and dinghy sailors. The circuit of the lakes is a favoured "fun run".

The original Wolverton was a medieval settlement just north and west of today's town. The ridge and furrow pattern of agriculture can still be seen in the nearby fields and the Saxon (rebuilt in 1819) Church of the Holy Trinity still stands next to the Norman Motte and Bailey site. Modern Wolverton was a 19th-century New Town built to house the workers at the Wolverton railway works, which built engines and carriages for the London and North Western Railway.

Economy, demography, geography and politics

Data on the economy, demography and politics of Milton Keynes are collected at the Borough level and are detailed at Economy of the Borough and Demographics of the Borough. However, since the urban area is predominant in the Borough, it is reasonable to assume that, other than for agriculture, the figures are broadly the same.

Milton Keynes is one of the more successful (per capita) economies in the South East, with a gross value added per capita index that was 47% higher than the national average (2005 data).[62] Average wages place it in the top five nationally (2015 data).[63]

With 99.4% SMEs, just 0.6% of businesses locally employ more than 250 people:[64] the more notable of these include the Open University, Santander UK, Volkswagen Group, Network Rail and Mercedes Benz. Of the remaining enterprises, 81.5% employ fewer than 10 people.[64] The 'professional, scientific and technical sector' contributes the largest number of business units, 16.7%.[64] The retail sector is the largest contributor of employment.[64] Milton Keynes has one of the highest business start-ups in England and the start-up levels remained high during the 2009/10 recession.[64] Although Education, Health and Public Administration are important contributors to employment, the contribution is significantly less than in England or the South East as a whole.[64]

The population is significantly younger than the national averages: 22.6% of the Borough population are aged under 16 compared with 19.0% in England; 12.1% are aged 65+ compared with 17.3% in England.[65] According to 2011 census, the ethnic group categories makeup of Milton Keynes Urban Area is: 78.4% White, 8.7% South Asian, 7.5% Black, 3.5% Mixed Race, 1.2% Chinese and other Asian, and 0.7% other ethnic group.[66]

Modern parishes, community councils and districts

The Borough of Milton Keynes is fully parished. These are the parishes, community councils and the districts they contain, within Milton Keynes itself. For a list of parishes in the Borough, see Borough of Milton Keynes (Rest of the borough)

- Bletchley and Fenny Stratford: Brick fields, Central Bletchley, Denbigh North, Denbigh East, Denbigh West, Fenny Lock, Fenny Stratford, Granby, Mount Farm, Newton Leys, Water Eaton

- Bradwell: Bradwell, Bradwell Common, Bradwell village, Heelands, Rooksley

- Bradwell Abbey: Bradwell Abbey, Kiln Farm, Stacey Bushes, Two Mile Ash, Wymbush

- Broughton and Milton Keynes (shared parish council): Atterbury, Brook Furlong, Broughton, Fox Milne, Middleton (including Milton Keynes Village), Northfield, Oakgrove, Pineham

- Campbell Park: Fishermead, Newlands, Oldbrook, Springfield, Willen and Willen Lake, Winterhill, Woolstone

- Central Milton Keynes: Central Milton Keynes and Campbell Park

- Great Linford: Blakelands, Bolbeck Park, Conniburrow, Downs Barn, Downhead Park, Great Linford, Giffard Park, Neath Hill, Pennyland, Tongwell, Willen Park

- Kents Hill, Monkston and Brinklow: Brinklow, Kents Hill, Kingston, Monkston

- Loughton: Loughton, Loughton Lodge, Great Holm, Knowlhill (including the Bowl)

- New Bradwell

- Old Woughton: Woughton on the Green, Woughton Park, Passmore (formerly Tinkers Bridge North).

- Shenley Brook End: Emerson Valley, Furzton, Kingsmead, Shenley Brook End, Snelshall, Tattenhoe, Tattenhoe Park, Westcroft

- Shenley Church End: Crownhill, Grange Farm, Hazeley, Medbourne, Oakhill, Oxley Park, Shenley Church End, Woodhill

- Simpson: Ashland, Simpson, West Ashland

- Stantonbury: Bancroft/Bancroft Park, Blue Bridge, Bradville, Linford Wood, Oakridge Park, Stantonbury, Stantonbury Fields

- Stony Stratford: Fullers Slade, Galley Hill, Stony Stratford

- Walton: Brown's Wood, Caldecotte, Old Farm Park, Tilbrook, Tower Gate, Walnut Tree, Walton, Walton Hall, Walton Park, Wavendon Gate.[67]

- West Bletchley: Far Bletchley, Old Bletchley, West Bletchley, Denbigh Hall

- Wolverton and Greenleys: Greenleys, Hodge Lea, Stonebridge, Wolverton, Old Wolverton

- Woughton: Beanhill, Bleak Hall, Coffee Hall, Eaglestone, Elfield Park, Leadenhall, Netherfield, Peartree Bridge, Redmoor, Tinkers Bridge.

Closest cities, towns and villages

Notable people

- Ed Slater, professional rugby player for Gloucester Rugby who went to Two Mile Ash School and Denbigh Secondary School.

- Dele Alli, professional footballer for Tottenham Hostpur who started his career with Milton Keynes Dons[68]

- Christopher B-Lynch, (visiting) Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Cranfield University, responsible for inventing the eponymously named B-Lynch suture which is used to treat post-partum haemorrhage due to uterine atony worked at Milton Keynes General Hospital.[69][70]

- Andrew Baggaley, English table tennis champion.[71]

- Sam Baldock, professional footballer for Brighton and Hove Albion, who began his football career at MK Dons.[72]

- Errol Barnett, an anchor and correspondent for CNN is from Milton Keynes. He lived in Crownhill and attended Holmwood First School and Two Mile Ash Middle School before moving to the US.[73]

- Emily Bergl, an actress famous for her roles in Desperate Housewives and Shameless. Bergl was born in Milton Keynes, to an Irish mother and an English architect father.

- Chris Clarke, English sprinter.[74]

- Adam Ficek, drummer of London band Babyshambles.[75]

- Lee Hasdell, professional Mixed martial artist and Kickboxer, and pioneer of Mixed martial arts in the UK.[76]

- James Hildreth, cricketer who plays for Somerset and has played for England.[77]

- Shaun Hutson, Novelist of horror novels and dark urban thrillers, has lived in Milton Keynes for several years.

- Liam Kelly, professional footballer for Oldham Athletic.

- Jim Marshall (1923-2012), founder and CEO of Marshall Amplification was living in and ran his business from Milton Keynes when he died.[78]

- Gordon Moakes, the bassist for the London-based rock band Bloc Party.[79]

- Clare Nasir, the meteorologist, TV and radio personality, was born in Milton Keynes in 1970.[80]

- Craig Pickering, English sprinter.[81]

- Sarah Pinborough, English horror writer.[82]

- Ian Poulter, PGA & European Tour golf professional. Member of the 2010 and 2012 European Ryder Cup Teams.[83]

- Mark Randall, professional footballer for Milton Keynes Dons.[84]

- Eddie Richards, Britain's godfather of house music.[85]

- Antonee Robinson, professional footballer for Everton, on loan to Bolton Wanderers.

- Greg Rutherford, long jump gold medallist for Team GB at the 2012 Olympic Games.[86]

- Jack Trevor Story, novelist, was a long-term resident of Milton Keynes.[87]

- Sam Tomkins, Wigan Warriors and England international rugby league player, was born in Milton Keynes.[88]

- Alan Turing (1912-1954), played a significant role in the creation of the modern computer. He lodged at the Crown Inn, Shenley Brook End, while working at Bletchley Park.[89]

- Nat Wei, Baron Wei, member of the House of Lords, (born Watford], was brought up and went to school in Milton Keynes.

- Kevin Whately lives in Woburn Sands, in the Milton Keynes urban area.

- Dan Wheldon (1978-2011), Indy car driver.[90]

- George Williams, professional footballer for Fulham

- Pete Winkelman, Chairman of Milton Keynes Dons Football Club, owner of Linford Manor recording studios, long term resident.[91]

Bands

- Capdown, the ska punk band, came from and formed in Milton Keynes in 1997.[92]

- Fellsilent, the metal band, come from and formed in Milton Keynes in 2003.[93]

- Tesseract, the djent band formed as a full live act in Milton Keynes in 2007. Tesseract's guitarist, songwriter and producer Acle Kahney is also a former member of Fellsilent.

- Hacktivist, the Grime, djent band formed in 2011.

- RavenEye, the rock band, formed in Milton Keynes in 2014.[94]

Transport

The Grand Union Canal between London and Birmingham provides a major axis in the design of Milton Keynes.

Milton Keynes has five railway stations. Milton Keynes Central is served by inter-city services. Wolverton, Milton Keynes Central and Bletchley stations are on the West Coast Main Line. Fenny Stratford and Bow Brickhill are on the Marston Vale Line. Woburn Sands railway station, also on the Marston Vale line, is in the small town of Woburn Sands just inside the urban area.

The M1 motorway runs along the east flank of MK and serves it from junctions 13, 14, and 15A. The A5 road runs right through MK as a grade separated dual carriageway. Other main roads are the A509, linking Milton Keynes with Wellingborough and Kettering, and the A421 and A422, both running west towards Buckingham and east towards Bedford. Proximity to the M1 has led to construction of a number of distribution centres, including Magna Park at the A421/A5130 junction.[95]

Many long-distance coaches stop at the Milton Keynes coachway,[96] (beside M1 Junction 14), some 3.3 miles (5.3 km) from the centre (or 4 mi or 6.4 km from Milton Keynes Central railway station).[97] There is also a park and ride car park on the site. Regional coaches stop at Milton Keynes Central.

The main bus operator is Arriva Shires & Essex, providing a number of routes which mainly pass through or serve Central Milton Keynes. Milton Keynes is also served by Arriva-branded services from Aylesbury and Luton as well and Stagecoach East which operate routes to Oxford, Cambridge, Stagecoach Midlands which operates routes to Peterborough and Leicester. Some local services are run by independent operators such as Z&S International and Centrebus.

Milton Keynes is served by (and provides part of) routes 6 and 51 on the National Cycle Network.

The nearest international airport is London Luton Airport, accessible by Stagecoach route 99 from MK Central station, which runs with wheelchair-accessible coaches. There is a direct rail connection to Birmingham International station for Birmingham Airport. In addition, Cranfield Airport, an airfield, is 6 miles (10 km) from the centre. (Although Milton Keynes is allocated an International Air Transport Association airport code of KYN,[98] it does not have an airport. Proposals in 1971 for a third London airport at (relatively) nearby Cublington were rejected).[99]

Twin towns

Climate

Milton Keynes experiences an oceanic climate (Köppen climate classification Cfb) similar to almost all of the United Kingdom. Recorded temperature extremes range from 34.6 °C (94.3 °F)[101] during July 2006, to as low as −20.6 °C (−5.1 °F)[102] on 25 February 1947. More recently the temperature fell to −16.3 °C (2.7 °F)[103] on 20 December 2010

The nearest Met Office weather station is in Woburn,[104] located just outside the south eastern fringe of the Milton Keynes urban area.

| Climate data for Woburn 1981–2010 (Weather station 3 mi (5 km) to the SE of Central Milton Keynes) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.0 (44.6) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

16.6 (61.9) |

19.6 (67.3) |

22.1 (71.8) |

21.9 (71.4) |

18.7 (65.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

0.9 (33.6) |

2.7 (36.9) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.7 (53.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.0 (44.6) |

3.8 (38.8) |

1.5 (34.7) |

5.8 (42.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 54.2 (2.13) |

41.7 (1.64) |

45.3 (1.78) |

52.1 (2.05) |

54.3 (2.14) |

53.2 (2.09) |

53.1 (2.09) |

55.4 (2.18) |

57.5 (2.26) |

70.3 (2.77) |

63.0 (2.48) |

57.3 (2.26) |

657.4 (25.88) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 52.0 | 69.4 | 105.5 | 147.4 | 183.4 | 179.9 | 197.1 | 189.0 | 137.0 | 105.6 | 61.7 | 43.5 | 1,471.6 |

| Source: Met Office[105] | |||||||||||||

Notes

- ^ Although Milton Keynes was specified to be a city in scale and the term "city" is used locally (inter alia to avoid confusion with its constituent towns), formally this title cannot be used. This is because conferment of city status in the United Kingdom is a Royal prerogative.

References

- ^ a b "2011 Census - Built-up areas". ONS. Retrieved 1 July 2013.

- ^ a b ""North Buckinghamshire (Milton Keynes) New Town (Designation) Order", London Gazette, 24 January 1967, page 827". London Gazette. Retrieved 14 January 2014..

- ^ "Census 2011". Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 25 August 2012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Vision of Britain: historic census populations for modern Milton Keynes UA Accessed 11 October 2006

- ^ "Bletchley Pioneers, Planning, & Progress". Clutch.open.ac.uk. 16 December 1944. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Early days of overspill". Clutch.open.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Need for more planned towns in the South-East.The Times. 2 December 1964 Accessed 21 September 2006

- ^ South East Study 1961–1981 HMSO 1964, cited in The Plan for Milton Keynes. Retrieved 25 September 2006

- ^ Urgent action to meet London housing needs. The Times, 4 February 1965. Retrieved 21 September 2006

- ^ Volume 1 of The Plan for Milton Keynes (Milton Keynes Development Corporation March 1970 ISBN 0-903379-00-7 begins (in the Foreword by Lord ("Jock") Campbell of Eskan): "This plan for building the new city of Milton Keynes ..." (page xi) Accessed 25 September 2006

- ^ Area of New Town Increased by 6,000 acres (24 km2). The Times. 14 January 1966. Retrieved 21 September 2006

- ^ "MK Council General Statistics". Milton Keynes Council. Archived from the original on 13 July 2007. Retrieved 10 April 2008.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b Llewelyn-David et al. The Plan for Milton Keynes 1968. Retrieved 11 January 2007

- ^ The South East Study 1961–1981 HMSO London, 1964: "A big change in the economic balance within the south east is needed to modify the dominance of London and to get a more even distribution of growth". Retrieved 27 November 2006

- ^ Barkham, Patrick (3 May 2016). "The struggle for the soul of Milton Keynes". Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- ^ Jeff Bishop Milton Keynes – the Best of Both Worlds? Public and professional views of a new city. University of Bristol School for Advanced Urban Studies 1981. Retrieved 13 February 2007

- ^ a b Walker The Architecture and Planning of Milton Keynes, Architectural Press, London 1981. Retrieved 13 February 2007

- ^ M Webber (1963) 'Order in Diversity: Community Without Propinquity, in L Wingo (ed.) 'Cities and Spaces Hopkins, Baltimore. Retrieved 13 February 2007

- ^ "Welcome to the Millennium CLUTCH Project". Clutch.open.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Bletchley Park welcomes 2015's 200,000th visitor". Bletchley Park. 26 August 2015. Retrieved 25 January 2017.

- ^ "History in Milton Keynes". Mkweb.co.uk via Archive.org. 22 October 2004. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jef Bishop Milton Keynes – the Best of Both Worlds? Public and professional views of a new city. University of Bristol School for Advanced Urban Studies. Retrieved 13 February 2007.

- ^ 1979: Milton Keynes shopping building – The Twentieth Century Society

- ^ Shopping building, Milton Keynes: Grade II listed 'This building is listed under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 as amended for its special architectural or historic interest' – English Heritage

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Kitchen, Roger; Hill, Marion (2007). 'The story of the original CMK' … told by the people who shaped the original Central Milton Keynes (interviews). Milton Keynes: Living Archive. p. 17. ISBN 0-904847-34-9. Retrieved 26 January 2009. (Professor Lock is visiting professor of town planning at Reading University. He was the chief town planner for CMK.) (Ten miles is about 16km and 18,000 acres is about 7,300 hectares),

- ^ Walker, Derek (1982). The Architecture and Planning of Milton Keynes. London: Architectural Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-85139-735-2. cited in Clapson, Mark (2004). A Social History of Milton Keynes: Middle England/Edge City. London: Frank Cass. p. 40. ISBN 0-7146-8417-1.

- ^ Urban Eden

- ^ Milton Keynes Council. "Milton Keynes Council- Local Air Quality Management – Environme". Mkweb.co.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Peter Youngman, Architect of the modern British landscape – The Guardian, 17 June 2005, retrieved 23 January 2017

- ^ TNeil Higson, ex Chief landscape architect MKDC 28 March 1991; Frank Henshaw, ex General Manager MKDC 28 Feb 1991 National Archives, (undated), retrieved 23 January 2017

- ^ Pevsner, Nikolaus; Williamson, Dr Elizabeth (11 March 1994). Buckinghamshire (Pevsner Architectural Guides). Yale University Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ "The Parks Trust model". theparkstrust.com. Archived from the original on 7 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hetherington, Peter (6 January 2004). "Milton Keynes to double in size over next 20 years". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Statutory Instruments: 2004 No. 932 – Urban Development, England" (PDF). Opsi.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Milton Keynes Partnership". Miltonkeynespartnership.info. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "World Class Music and Entertainment". The Stables. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "National Youth Music Camps". The Stables. Retrieved 14 February 2017.

- ^ IF: Milton Keynes International Festival.

- ^ MK11 at Kiln Farm Club named best live music pub by Milton Keynes magazine

- ^ "MK Gallery". mkgallery.org. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Milton Keynes – Speakeasy". MKWeb. 22 October 2004. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "MK Poetry Kapow! Homepage". Poetrykapow.co.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Tongue in Chic Poets – supporting performance of poetry and the spoken word". Tongueinchicpoets.com. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Mark Niel appointed Milton Keynes' first Poet Laureate", BBC News, BBC, 23 May 2011

- ^ "Quorum choir at Milton Keynes". Quorummk.org.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Milton Keynes Council. "Milton Keynes Council – COIN". Milton-keynes.gov.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Trails, Guides, Walks & Maps: : Arts & Cultural Venues Map (PDF link)<". Milton Keynes Council. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ Milton Keynes College, UCMK. Postgraduate Certificate in Education, in partnership with and accredited by Oxford Brookes University Retrieved 6 August 2009

- ^ "The Webber Independent School". The Webber Independent School. Archived from the original on 23 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Autumn Term 2012 (5 September 2012). "Private school for children aged 2 months to 11 years old | Milton Keynes Preparatory School". Mkprep.co.uk. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "MKCDC at Bradwell Abbey". Mkcdc.org.uk. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Get a document legalised 'Births, deaths, marriages and ce' at GOV.UK

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen, Julian Borger, Nick Hopkins, Nick Davies and James Ball. "Mastering the internet: how GCHQ set out to spy on the world wide web." The Guardian. Friday 21 June 2013. Retrieved on 21 June 2013.

- ^ MKFM. "Licence Application - MKFM". MKFM.

- ^ "Radio for Milton Keynes". CRMK. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ a b Milton Keynes is leading the way to recovery – Milton Keynes Citizen, 18 December 2012

- ^ "Selected Headquarters in Milton Keynes" (PDF). Invest MK. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Milton Keynes tops economy growth list – ITV News, 19 January 2015

- ^ Milton Keynes Council (30 November 2004). "Milton Keynes Council – Statistics". Mkweb.co.uk via archive.org. Archived from the original on 26 April 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Days Out in Milton Keynes - Day Trips & Things To Do in MK - oneMK". MK News via Archive.org. Archived from the original on 15 October 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Regional Gross Value Added Archived 1 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine pp 240–253 pub. Office for National Statistics

- ^ Northern cities head list of UK's low-wage, high-welfare economies (Centre for Cities report) – The Guardian, 25 January 2016

- ^ a b c d e f Milton Keynes: Local Economic Assessment Refresh, March 2013 (PDF), Chapter 3. Milton Keynes Council, March 2013

- ^ SNA Population and Growth Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine – Milton Keynes Council (2011 Census data).

- ^ Neighbourhood Statistics. "Milton Keynes Urban Area Output Areas". Neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ^ "Link to the Community Councils web page". Community Council. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Osborne, Chris. "MK Dons' Dele Alli has the makings of next Steven Gerrard". BBC Sport.

- ^ "Awards & Honours - Professor Christopher B-Lynch (GORSL)". cblynch.co.uk.

- ^ "'A worldwide review of the uses of the uterine compression suture techniques as alternative to hysterectomy in the management of severe post-partum haemorrhage'". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology.

- ^ "Andrew Baggaley Biography". Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Sam Baldock Biography". Archived from the original on 7 September 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Errol Barnett profile at CNN.com". Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Chris Clarke set for Worlds final – Update GB finish 7th". Milton Keynes Citizen. 2 September 2011. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ "Adam Ficek profile". BBC. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ Lewis, Peter (April 2004), "A Total Fighter", Fighters – Kickboxing news, p. 45

- ^ "James Hildreth – profile". Somerset County Cricket Club. Retrieved 11 February 2012.

- ^ James, Huw (5 April 2012). "Death Is Announced of Jim Marshall". Heart FM. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- ^ McLean, Craig (7 January 2007). "21st-century boy". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "TV's Clare says Wrap Up for Winter". NHS Milton Keynes. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Campbell backs Pickering to come good again in 2012". Milton Keynes Citizen. 25 January 2012. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Sarah Pinborough Interview". omegasapple.com. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Poulter's back in the swing at Woburn". Milton Keynes Citizen. 29 July 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "MK Dons: Mark Randall signs longer deal". Retrieved 31 July 2014.

- ^ Eddie Richards interview for DJ History - http://www.djhistory.com/interviews/eddie-richards. January 2014

- ^ "Greg Rutherford – Long Jumper". Bucks Sport. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Independent Obituary – Jack Trevor Story". jacktrevorstory.co.uk. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Hudson, Elizabeth (3 February 2012). "Sam Tomkins targets more trophies with Wigan". BBC. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Douglas, Ian (5 August 2011). "Google backs Bletchley Park restoration project". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Stars race to honour Dan Wheldon in Milton Keynes". BBC. 5 December 2011. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ Jackson, Jamie (30 March 2008). "From Wimbledon to Winkelman, a crazy new journey". The Observer. London. Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ "The Capdown Fansite". Retrieved 12 February 2012.

- ^ "Fell Silent Milton Keynes Metal Heros". miltonkeynes.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "RavenEye". RavenEye.

- ^ "Magna Park, Milton Keynes". Gazeley.com. Gazeley Limited. Archived from the original on 29 January 2012. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|dead-url=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Services to and from Milton Keynes Coachway, Park & Ride" (PDF). National Express Coaches. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Google Maps". Maps.google.co.uk. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ Milton Keynes Airport – World-airport-codes.com accessed 9 June 2012

- ^ "THIRD LONDON AIRPORT (ROSKILL COMMISSION REPORT)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. 4 March 1971.

- ^ "Crescendo: Combined rational and renewable energy strategies in cities, for existing and new dwellings and optimal quality of life". Cordis.europe.eu. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "2006 Maximum". Metoffice.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "1947 minimum". doi:10.1002/wea.66.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Rogers, Simon (21 December 2010). "2010 minimum". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 3 March 2011.

- ^ "Synoptic and climate stations – February 2012 – Met Office". Met Office. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- ^ "Woburn 1981–2010 averages". Met Office. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

External links

- Template:Dmoz

- Milton Keynes news, what's on and community portal

- Official visitor website for Milton Keynes

- Milton Keynes Council

- City Discovery Centre (MK urban studies centre)

- Urban Design magazine – "Milton Keynes at 40"

- Community Forum for Milton Keynes Borough

- Milton Keynes in 1968, on BFI Player

- Community information website