Blueberry

| Blueberry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Vaccinium corymbosum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Ericales |

| Family: | Ericaceae |

| Genus: | Vaccinium |

| Section: | Vaccinium sect. Cyanococcus Rydb. |

| Species | |

|

See text | |

Blueberries are perennial flowering plants with indigo-colored berries. They are classified in the section Cyanococcus within the genus Vaccinium. Vaccinium also includes cranberries, bilberries and grouseberries.[1] Commercial "blueberries" are native to North America, and the "highbush" varieties were not introduced into Europe until the 1930s.[2]

Blueberries are usually prostrate shrubs that can vary in size from 10 centimeters (3.9 in) to 4 meters (13 ft) in height. In the commercial production of blueberries, the smaller species are known as "lowbush blueberries" (synonymous with "wild"), while the larger species are known as "highbush blueberries".

The leaves can be either deciduous or evergreen, ovate to lanceolate, and 1–8 cm (0.39–3.15 in) long and 0.5–3.5 cm (0.20–1.38 in) broad. The flowers are bell-shaped, white, pale pink or red, sometimes tinged greenish. The fruit is a berry 5–16 millimeters (0.20–0.63 in) in diameter with a flared crown at the end; they are pale greenish at first, then reddish-purple, and finally dark purple when ripe. They are covered in a protective coating of powdery epicuticular wax, colloquially known as the "bloom".[3] They have a sweet taste when mature, with variable acidity. Blueberry bushes typically bear fruit in the middle of the growing season: fruiting times are affected by local conditions such as altitude and latitude, so the peak of the crop, in the northern hemisphere, can vary from May to August.

Origins

The genus Vaccinium has a mostly circumpolar distribution, with species mainly being present in North America, Europe, and Asia.

Many commercially sold species with English common names including "blueberry" are from North America. Many North American native species of blueberries are grown commercially in the Southern Hemisphere in Australia, New Zealand and South American nations.

Several other wild shrubs of the genus Vaccinium also produce commonly eaten blue berries, such as the predominantly European Vaccinium myrtillus and other bilberries, which in many languages have a name that translates to "blueberry" in English. See the Identification section for more information.

Species

Note: habitat and range summaries are from the Flora of New Brunswick, published in 1986 by Harold R. Hinds and Plants of the Pacific Northwest coast, published in 1994 by Pojar and MacKinnon.

- Vaccinium alaskaense (Alaskan blueberry): one of the dominant shrubs in Alaskan and British Columbian coastal forests

- Vaccinium angustifolium (lowbush blueberry): acidic barrens, bogs and clearings, Manitoba to Labrador, south to Nova Scotia and in the US, to Iowa and Virginia

- Vaccinium boreale (northern blueberry): peaty barrens, Quebec and Labrador (rare in New Brunswick), south to New York and Massachusetts

- Vaccinium caesariense (New Jersey blueberry)

- Vaccinium corymbosum (northern highbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium constablaei (hillside blueberry)

- Vaccinium consanguineum (Costa Rican blueberry)

- Vaccinium darrowii (evergreen blueberry)

- Vaccinium elliottii (Elliott blueberry)

- Vaccinium formosum (southern blueberry)

- Vaccinium fuscatum (black highbush blueberry; syn. V. atrococcum)

- Vaccinium hirsutum (hairy-fruited blueberry)

- Vaccinium myrsinites (shiny blueberry)

- Vaccinium myrtilloides (sour top, velvet leaf, or Canadian blueberry)

- Vaccinium operium (cyan-fruited blueberry)

- Vaccinium pallidum (dryland blueberry)

- Vaccinium simulatum (upland highbush blueberry)

- Vaccinium tenellum (southern blueberry)

- Vaccinium virgatum (rabbiteye blueberry; syn. V. ashei)

Some other blue-fruited species of Vaccinium:

- Vaccinium koreanum

- Vaccinium myrtillus (bilberry or European blueberry)

- Vaccinium uliginosum

Identification

Commercially offered blueberries are usually from species that naturally occur only in eastern and north-central North America. Other sections in the genus, native to other parts of the world, including the Pacific Northwest and southern United States,[4] South America, Europe, and Asia, include other wild shrubs producing similar-looking edible berries, such as huckleberries and whortleberries (North America) and bilberries (Europe). These species are sometimes called "blueberries" and sold as blueberry jam or other products.

The names of blueberries in languages other than English often translate as "blueberry", e.g., Scots blaeberry and Norwegian blåbær. Blaeberry, blåbær and French myrtilles usually refer to the European native bilberry (V. myrtillus), while bleuets refers to the North American blueberry. Russian голубика ("blue berry") does not refer to blueberries, which are non-native and nearly unknown in Russia, but rather to their close relatives, bog bilberries (V. uliginosum).

Cyanococcus blueberries can be distinguished from the nearly identical-looking bilberries by their flesh color when cut in half. Ripe blueberries have light green flesh, while bilberries, whortleberries and huckleberries are red or purple throughout.

Cultivation

Blueberries may be cultivated, or they may be picked from semiwild or wild bushes. In North America, the most common cultivated species is V. corymbosum, the northern highbush blueberry. Hybrids of this with other Vaccinium species adapted to southern U.S. climates are known collectively as southern highbush blueberries.[5]

So-called "wild" (lowbush) blueberries, smaller than cultivated highbush ones, have intense color. The lowbush blueberry, V. angustifolium, is found from the Atlantic provinces westward to Quebec and southward to Michigan and West Virginia. In some areas, it produces natural "blueberry barrens", where it is the dominant species covering large areas. Several First Nations communities in Ontario are involved in harvesting wild blueberries.

"Wild" has been adopted as a marketing term for harvests of managed native stands of lowbush blueberries. The bushes are not planted or genetically manipulated, but they are pruned or burned over every two years, and pests are "managed".[6]

Numerous highbush cultivars of blueberries are available, with diversity among them, each having individual qualities. A blueberry breeding program has been established by the USDA-ARS breeding program at Beltsville, Maryland, and Chatsworth, New Jersey. This program began when Frederick Vernon Coville of the USDA-ARS collaborated with Elizabeth Coleman White of New Jersey.[7] In the early part of the 20th century, White offered pineland residents cash for wild blueberry plants with unusually large fruit.[8] After 1910 Coville began to work on blueberry, and was the first to discover the importance of soil acidity (blueberries need highly acidic soil), that blueberries do not self-pollinate, and the effects of cold on blueberries and other plants.[9] In 1911, he began a program of research in conjunction with White, daughter of the owner of the extensive cranberry bogs at Whitesbog in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. His work doubled the size of some strains' fruit, and by 1916, he had succeeded in cultivating blueberries, making them a valuable crop in the Northeastern United States.[10][11] For this work he received the George Roberts White Medal of Honor from the Massachusetts Horticultural Society.

The rabbiteye blueberry (Vaccinium virgatum syn. V. ashei) is a southern type of blueberry produced from the Carolinas to the Gulf Coast states. Other important species in North America include V. pallidum, the hillside or dryland blueberry. It is native to the eastern U.S., and common in the Appalachians and the Piedmont of the Southeast. Sparkleberry, V. arboreum, is a common wild species on sandy soils in the Southeast.

Successful blueberry cultivation requires attention to soil pH (acidity) measurements in the acidic range.[12][13][14]

Blueberry bushes often require supplemental fertilization,[13] but over-fertilzation with nitrogen can damage plant health shown by nitrogen-burn visible on the leaves.[12][13]

Growing areas

Significant production of highbush blueberries occurs in British Columbia, Maryland, Western Oregon, Michigan, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Washington. The production of southern highbush varieties in California is rapidly increasing, as varieties originating from University of Florida, Connecticut, New Hampshire, North Carolina State University and Maine have been introduced. Southern highbush berries are now also cultivated in the Mediterranean regions of Europe, Southern Hemisphere countries and China.

United States

According to a 2014 report by US Department of Agriculture, Washington was the nation's largest producer of cultivated (highbush) blueberries with 96.1 million pounds, followed in order of "utilized production" volume by Michigan and Georgia, Oregon, New Jersey, California and North Carolina.[15] In terms of acres harvested for cultivated blueberries in 2014, the leading state was Michigan (19,000 acres) followed by Georgia, Oregon, Washington and New Jersey.[15]

Hammonton, New Jersey claims to be the "Blueberry Capital of the World,[16] with over 80% of New Jersey's cultivated blueberries coming from this town.[17] Every year the town hosts a large festival that draws thousands of people to celebrate the fruit.[18]

Resulting from cultivation of both lowbush (wild) and highbush blueberries, Maine accounts for 10% of all blueberries grown in North America with 44,000 hectares (110,000 acres) farmed, but only half of this acreage is harvested each year due to variations in pruning practices.[19] The wild blueberry is the official fruit of Maine.[20]

Canada

Canadian production of wild and cultivated blueberries in 2015 was 166,000 tonnes valued at $262 million, the largest fruit crop produced nationally accounting for 29% of all fruit value.[21]

British Columbia was the largest Canadian producer of cultivated blueberries, yielding 70,000 tonnes in 2015,[21] the world's largest production of blueberries by region.[22]

Atlantic Canada contributes approximately half of the total North American wild/lowbush annual production with New Brunswick having the largest in 2015, an amount expanding in 2016.[23] Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Québec are also major producers.[24] Nova Scotia recognizes the wild blueberry as its official provincial berry,[25] with the town of Oxford, Nova Scotia known as the Wild Blueberry Capital of Canada.[26]

Québec is a major producer of wild blueberries, especially in the regions of Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean (where a popular name for inhabitants of the regions is bleuets, or "blueberries") and Côte-Nord, which together provide 40% of Québec's total provincial production. This wild blueberry commerce benefits from vertical integration of growing, processing, frozen storage, marketing and transportation within relatively small regions of the province.[27] On average, 80% of Québec wild blueberries are harvested on farms (21 million kg), the remaining 20% being harvested from public forests (5 million kg).[27] Some 95% of the wild blueberry crop in Québec is frozen for export out of the province.[27]

| Blueberry production – 2014 | |

|---|---|

| Country | (tonnes) |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 240 kJ (57 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

14.49 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 9.96 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 2.4 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.33 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.74 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 84 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[29] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[30] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Europe

Highbush blueberries were first introduced to Germany, Sweden and the Netherlands in the 1930s, and have since been spread to Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Romania, Poland, Italy, Hungary and other countries of Europe.[2] Poland, Germany, and France were the largest European producers in 2014 (table).

Southern Hemisphere

In the Southern Hemisphere, Peru, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay, South Africa, New Zealand, and Australia now export blueberries.

Blueberries were first introduced to Australia in the 1950s, but the effort was unsuccessful. In the early 1970s, David Jones from the Victorian Department of Agriculture imported seed from the U.S. and a selection trial was started. This work was continued by Ridley Bell, who imported more American varieties. In the mid-1970s, the Australian Blueberry Growers' Association was formed.[32]

The industry is new to Argentina: "Argentine blueberry production has increased over the last three years with planted area up to 400 percent", according to a 2005 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture.[33] "Argentine blueberry production has thrived in four different regions: the province of Entre Rios in northeastern Argentina, the province of Tucuman, the province of Buenos Aires and the southern Patagonian valleys", according to the report.[34] In the Bureau of International Labor Affairs report of 2014 on child labor and forced labor, blueberries were listed among the goods produced in such working conditions in Argentina.[35]

Chile is the biggest producer in South America and the largest exporter to the Northern Hemisphere, with an estimated area of 14,500 hectares (36,000 acres) in 2014.[citation needed] Chile exported about 104,505 tons of blueberries in the 2014/2015 season.[citation needed]

Introduction of the first plants into Chile occurred in 1979, brought from US and New Zealand, and commercial production started in the 1990s in the southern part of the country.[citation needed] Today, production ranges from Copiapó in the north to Puerto Montt in the south, allowing the country to offer blueberries from October through late March. Production has evolved rapidly in the last decade, becoming the fourth most important fruit exported in value terms. Blueberries are exported mainly to North America (79%), followed by Europe (17%), and Asia (South Korea, China and Japan).

In Peru, there are several private initiatives for the development of the crop. Also, the government through its agency Sierra Exportadora, has launched the program "Peru Berries" to take advantage of the existence of the ideal soil and climate required by the blueberry.[citation needed]

Production

In 2014, world production of blueberries (low- and highbush combined) was 525,620 tonnes, led by the United States with 50% of total production and Canada with 35%.[28] In 2016, Canada was the largest producer of wild blueberries, mainly in Quebec and the Atlantic provinces.[36]

Harvesting

Harvest seasons

The blueberry harvest in North America varies. It can start as early as May and usually ends in late summer. The principal areas of production in the Southern Hemisphere (Australia, Chile, New Zealand and Argentina) have long periods of harvest. In Australia, for example, due to the geographic spread of blueberry farms and the development of new cultivation techniques, the industry is able to provide fresh blueberries for 10 months of the year – from July through to April.[32] Similar to other fruits and vegetables, climate-controlled storage allows growers to preserve picked blueberries. Harvest in the UK is from June to August. Mexico also can harvest from October to February.

Harvest methods

Although blueberries were traditionally hand-picked with berry-picking rakes, modern farmers use machine harvesters that shake the fruit off the bush of cultivated highbush blueberries, while new machines are being developed for wild, lowbush blueberries.[37] The fruit is then brought to a cleaning and packaging facility where it is cleaned, packaged, and then sold. In Mexico, each farmer packs on site and sells directly, or may transport to a warehouse for storage until the berries are sold.[citation needed] Tunnels are often used to grow blueberries in Europe and this makes the season longer. This creates an opportunity to move crops into earlier or later markets to get better prices.

Uses

Blueberries are sold fresh or are processed as individually quick frozen (IQF) fruit, purée, juice, or dried or infused berries. These may then be used in a variety of consumer goods, such as jellies, jams, blueberry pies, muffins, snack foods, or as an additive to breakfast cereals.

Blueberry jam is made from blueberries, sugar, water, and fruit pectin. Blueberry sauce is a sweet sauce prepared using blueberries as a primary ingredient.

Blueberry wine is made from the flesh and skin of the berry, which is fermented and then matured; usually the lowbush variety is used.

Nutrients

Blueberries consist of 14% carbohydrates, 0.7% protein, 0.3% fat and 84% water (table). They contain only negligible amounts of micronutrients, with moderate levels (relative to respective Daily Values) (DV) of the essential dietary mineral manganese, vitamin C, vitamin K and dietary fiber (table).[38] Generally, nutrient contents of blueberries are a low percentage of the DV (table). One serving provides a relatively low caloric value of 57 kcal per 100 g serving and glycemic load score of 6 out of 100 per day.[38]

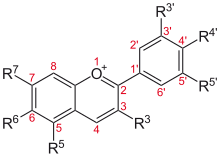

Phytochemicals and research

Blueberries contain anthocyanins, other polyphenols and various phytochemicals under preliminary research for their potential role in the human body. Most polyphenol studies have been conducted using the highbush cultivar of blueberries (V. corymbosum), while content of polyphenols and anthocyanins in lowbush (wild) blueberries (V. angustifolium) exceeds values found in highbush cultivars.[39]

Pesticides

Because "wild" is a marketing term generally used for all low-bush blueberries, it is not an indication that such blueberries are free from pesticides.[40]

The Environmental Working Group, referencing the USDA,[41] rates blueberries as a "significant concern".[42][43]

See also

References

- ^ Litz, Richard E (2005). [httpsxhbedhgxhjdrh xs://books.google.com/?id=AxbUJntXepEC&pg=PA222 Google Books -- Biotechnology of fruit and nut crops By Richard E. Litz]. ISBN 9780851996622.

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ a b Naumann, W. D. (1993). "Overview of the Vaccinium Industry in Western Europe". Fifth International Symposium on Vaccinium Culture. Wageningen, the Netherlands: International Society for Horticultural Science. pp. 53–58. ISBN 978-90-6605-475-2. OCLC 29663461.

{{cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editors=ignored (|editor=suggested) (help) - ^ "Blueberry Information". Jerseyfruit.com. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ "Plants Profile: Vaccinium corymbosum L., Highbush blueberry". US Department of Agriculture, National Resources Conservation Service. 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ "Growing Highbush Blueberries" (PDF). University of New Hampshire-Extension. Retrieved September 22, 2013.

- ^ "Wild Blueberry Network Information Centre".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Blueberry Growing Comes to the National Agricultural Library". US Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Magazine, Vol. 59, No. 5. June 2011. Retrieved 17 June 2011.

- ^ "The History of ''Whitesbog Village''". Whitesbog.org. 2014. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Mirsky, Steve. "Early 20th Century Botanist Gave Us Domesticated Blueberries". Scientific American. Retrieved September 21, 2013.

- ^ "History of White's Bog". Whitesbog Preservation Trust. Archived from the original on 2008-05-15. Retrieved 2008-01-11.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Jim Minick (June 29, 2016). "The Delicious Origins of The Domesticated Blueberry". JSTOR News. Retrieved June 30, 2016.

- ^ a b Longstroth M (2014). "Lowering the soil pH with sulfur" (PDF). Michigan State University.

- ^ a b c Hayden RA (2001). "Fertilizing blueberries" (PDF). Purdue University, Department of Horticulture. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ "Cornell fruit: berry diagnostic tool". Cornell University, Department of Horticulture. 2013. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b Bruce Eklund (January 2016). "2014 Blueberry Statistics" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture, National Agricultural Statistics Service, New Jersey Field Office, Trenton, NJ. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Home: Welcome to the Town of Hammonton". Town of Hammonton. 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ "Jersey Blueberries grown in the NJ Pine Barrens are the BEST!". Pineypower.com. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ "Hammonton Chamber of Commerce". Hammontonnj.us. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ David E. Yarborough (February 2015). "Wild Blueberry Culture in Maine,". Cooperative Extension: Maine Wild Blueberries, University of Maine. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "State Berry - Wild Blueberry". Secretary of State for Maine, Matthew Dunlap. 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ^ a b "Fruit and vegetable production, 2015 - Canada". Statistics Canada. 3 February 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ "British Columbia Blueberries". BC Blueberry Council. 2009. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ Deschênes V (20 April 2016). "New Brunswick to become world's largest producer of wild blueberries". Government of New Brunswick, Department of Agriculture, Aquaculture and Fisheries. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Dorff E (30 November 2015). "Blueberry varieties - Canada. In: The changing face of the Canadian fruit and vegetable sector: 1941 to 2011". Statistics Canada. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ Nova Scotia: Official emblems and symbols

- ^ "Wild blueberry trivia". Wild Blueberry Producers Associations of Nova Scotia. 2016. Retrieved 18 May 2016.

- ^ a b c Gagnon A (2006). "Wild Blueberry Production Guide in a Context of Sustainable Development: Survey of the Wild Blueberry Industry in Québec" (PDF). Ministère de l’Agriculture, des Pêcheries et de l’Alimentation du Québec. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ^ a b "Crops/Regions/World list/Production Quantity (pick lists), Blueberries, 2014". UN Food and Agriculture Organization, Corporate Statistical Database (FAOSTAT). 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on 2024-03-27. Retrieved 2024-03-28.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Archived from the original on 2024-05-09. Retrieved 2024-06-21.

- ^ "Flavonoids". Micronutrient Information Center, Linus Pauling Institute, Oregon State University, Corvallis, OR. November 2015. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Australian Blueberry Growers' Association". Australianblueberries.com.au. Retrieved 2013-11-06.

- ^ U.S. Department of Agriculture GAIN Report, Retrieved June 30, 2011

- ^ Pirovano, Francisco (12 January 2005). "Argentina Blueberries Voluntary 2005". GAIN Report. Foreign Agricultural Service. Retrieved 22 June 2009.

- ^ "List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor". dol.gov.

- ^ "Canadian Blueberries". Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Government of Canada. 24 November 2016. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- ^ "Progress Towards the Development of a Mechanical Harvester for Wild Blueberries". University of Maine, Cooperative Extension. 2001. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ a b "In-depth nutrition information on raw blueberries, per 100 g, USDA Nutrient Database, Standard Reference version SR-21". Nutritiondata.com. Conde Nast. 2014. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- ^ Kalt W, Ryan DA, Duy JC, Prior RL, Ehlenfeldt MK, Vander Kloet SP (October 2001). "Interspecific variation in anthocyanins, phenolics, and antioxidant capacity among genotypes of highbush and lowbush blueberries (Vaccinium section cyanococcus spp.)". J Agric Food Chem. 49 (10): 4761–7. doi:10.1021/jf010653e. ISSN 0021-8561. PMID 11600018.

- ^ "Catching the Toxic Drift: How Pesticides Used in the Blueberry Industry Threaten Our Communities, Our Water and the Environment". Environment Maine. 2005-08-16. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ "Measure E8: Pesticide Residues on Foods Frequently Consumed by Children". EPA. November 2010. Retrieved 9 September 2012.

- ^ "EWG'S 2011 Shopper's Guide Helps Cut Consumer Pesticide Exposure | Environmental Working Group". Ewg.org. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

- ^ "Executive Summary | EWG's Shopper's Guide to Pesticides | Environmental Working Group". EWG.org. Retrieved 2011-10-11.

Further reading

- Retamales, J.B. / Hancock, J.F. (2012). Blueberries (Crop Production Science in Horticulture). CABI. ISBN 978-1-84593-826-0

- Sumner, Judith (2004). American Household Botany: A History of Useful Plants, 1620-1900. Timber Press. p. 125. ISBN 0-88192-652-3. Google books link

- Wright, Virginia (2011). The Wild Blueberry Book. Down East Books. ISBN 978-0-89272-939-5