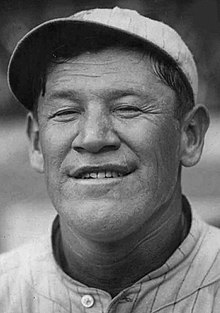

Jim Thorpe

| |

| No. 21, 3, 1[1] | |

|---|---|

| Position: | Back |

| Personal information | |

| Born: | May 22 or 28, 1887[2] Near Prague, Indian Territory |

| Died: | March 28, 1953 (aged 65) Lomita, California |

| Height: | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) |

| Weight: | 202 lb (92 kg) |

| Career information | |

| College: | Carlisle |

| Career history | |

| As a player: | |

| |

| As a coach: | |

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Head coaching record | |

| Career: | 14–25–2 |

| Record at Pro Football Reference | |

| Stats at Pro Football Reference | |

James Francis Thorpe (Sac and Fox (Sauk): Wa-Tho-Huk, translated as "Bright Path";[4] May 22 or 28,[2] 1887 – March 28, 1953)[5] was an American athlete and Olympic gold medalist. A member of the Sac and Fox Nation, Thorpe became the first Native American to win a gold medal for his home country. Considered one of the most versatile athletes of modern sports, he won Olympic gold medals in the 1912 pentathlon and decathlon, and played American football (collegiate and professional), professional baseball, and basketball. He lost his Olympic titles after it was found he had been paid for playing two seasons of semi-professional baseball before competing in the Olympics, thus violating the amateurism rules that were then in place. In 1983, 30 years after his death, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) restored his Olympic medals.

Thorpe grew up in the Sac and Fox Nation in Oklahoma, and attended Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, where he was a two-time All-American for the school's football team. After his Olympic success in 1912, which included a record score in the decathlon, he added a victory in the All-Around Championship of the Amateur Athletic Union. In 1913, Thorpe signed with the New York Giants, and he played six seasons in Major League Baseball between 1913 and 1919. Thorpe joined the Canton Bulldogs American football team in 1915, helping them win three professional championships; he later played for six teams in the National Football League (NFL). He played as part of several all-American Indian teams throughout his career, and barnstormed as a professional basketball player with a team composed entirely of American Indians.

From 1920 to 1921, Thorpe was nominally the first president of the American Professional Football Association (APFA), which became the NFL in 1922. He played professional sports until age 41, the end of his sports career coinciding with the start of the Great Depression. He struggled to earn a living after that, working several odd jobs. He suffered from alcoholism, and lived his last years in failing health and poverty. He was married three times and had eight children, before suffering from heart failure and dying in 1953.

Thorpe has received various accolades for his athletic accomplishments. The Associated Press named him the "greatest athlete" from the first 50 years of the 20th century, and the Pro Football Hall of Fame inducted him as part of its inaugural class in 1963. A Pennsylvania town was named in his honor and a monument site there is the site of his remains, which were the subject of legal action. Thorpe was portrayed in the 1951 film Jim Thorpe – All-American, and appeared in several films himself.

Early life

Information about Thorpe's birth, name and ethnic background varies widely.[6] He was baptized "Jacobus Franciscus Thorpe" in the Catholic Church. Thorpe was born in Indian Territory of the United States (later Oklahoma), but no birth certificate has been found. He was generally considered to have been born on May 22, 1887,[5] near the town of Prague, Oklahoma.[7] Thorpe himself said in a note to The Shawnee News-Star in 1943 that he was born May 28, 1888, "near and south of Bellemont – Pottawatomie County – along the banks of the North Fork River ... hope this will clear up the inquiries as to my birthplace."[8] However, most biographers believe that he was born on May 22, 1887, as that is what is listed on his baptismal certificate. Bellemont was a small community, now disappeared, on the line between Pottawatomie and Lincoln Counties.[9][10] Thorpe referred to Shawnee as his birthplace in the 1943 note.[8]

Thorpe's parents were both of mixed-race ancestry. His father, Hiram Thorpe, had an Irish father and a Sac and Fox Indian mother.[11][12] His mother, Charlotte Vieux, had a French father and a Potawatomi mother, a descendant of Chief Louis Vieux. He was raised as a Sac and Fox,[13] and his native name, Wa-Tho-Huk, translated as "path lit by great flash of lightning" or, more simply, "Bright Path".[6] As was the custom for Sac and Fox, he was named for something occurring around the time of his birth, in this case the light brightening the path to the cabin where he was born. Thorpe's parents were both Roman Catholic, a faith which Thorpe observed throughout his adult life.[14]

Thorpe attended the Sac and Fox Indian Agency school in Stroud, Oklahoma, with his twin brother, Charlie. Charlie helped him through school until he died of pneumonia when they were nine years old.[15] He ran away from school several times. His father then sent him to the Haskell Institute, an Indian boarding school in Lawrence, Kansas, so that he would not run away again.[16] When his mother died of childbirth complications two years later,[17] he became depressed. After several arguments with his father, he left home to work on a horse ranch.[16]

In 1904 the sixteen-year-old Thorpe returned to his father and decided to attend Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. There his athletic ability was recognized and he was coached by Glenn Scobey "Pop" Warner, one of the most influential coaches of early American football history.[18] Later that year he became orphaned after Hiram Thorpe died from gangrene poisoning after being wounded in a hunting accident,[17] and Jim again dropped out of school. He resumed farm work for a few years and then returned to Carlisle Indian Industrial School.[16]

Amateur career

College career

Thorpe began his athletic career at Carlisle in 1907 when he walked past the track and beat all the school's high jumpers with an impromptu 5-ft 9-in jump still in street clothes.[19] His earliest recorded track and field results come from 1907. He also competed in football, baseball, lacrosse and even ballroom dancing, winning the 1912 intercollegiate ballroom dancing championship.[20]

Pop Warner was hesitant to allow Thorpe, his best track and field athlete, to compete in a physical game such as football.[21] Thorpe, however, convinced Warner to let him try some rushing plays in practice against the school team's defense; Warner assumed he would be tackled easily and give up the idea.[21] Thorpe "ran around past and through them not once, but twice".[21] He then walked over to Warner and said "Nobody is going to tackle Jim", while flipping him the ball.[21]

Thorpe gained nationwide attention for the first time in 1911.[22] As a running back, defensive back, placekicker and punter, Thorpe scored all his team's points—four field goals and a touchdown—in an 18–15 upset of Harvard, a top ranked team in the early days of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA).[21] His team finished the season 11–1. In 1912 Carlisle won the national collegiate championship largely as a result of his efforts – he scored 25 touchdowns and 198 points during the season, according to CNN's Greg Botelho.[18] Steve Boda, a researcher for the NCAA, credits Thorpe with 27 touchdowns and 224 points. Thorpe rushed 191 times for 1,869 yards, according to Boda; the figures do not include statistics from 2 of Carlisle's 14 games in 1912 because full records are not available.[23]

Carlisle's 1912 record included a 27–6 victory over Army.[7] In that game, Thorpe's 92-yard touchdown was nullified by a teammate's penalty, but on the next play Thorpe rushed for a 97-yard touchdown.[24] Future President Dwight Eisenhower, who played against him that season, recalled of Thorpe in a 1961 speech:

Here and there, there are some people who are supremely endowed. My memory goes back to Jim Thorpe. He never practiced in his life, and he could do anything better than any other football player I ever saw.[18]

Thorpe was awarded All-American honors in both 1911 and 1912.[7]

Football was – and would remain – Thorpe's favorite sport.[25] He did not compete in track and field in 1910 or 1911,[26] even though this turned out to be the sport in which he gained his greatest fame.[7]

In the spring of 1912, he started training for the Olympics. He had confined his efforts to jumps, hurdles and shot-puts, but now added pole vaulting, javelin, discus, hammer and 56 lb weight. In the Olympic trials held at Celtic Park in New York, his all-round ability stood out in all these events and so he earned a place on the team that went to Sweden.[7]

Olympic career

For the 1912 Summer Olympics in Stockholm, Sweden, two new multi-event disciplines were included, the pentathlon and the decathlon.[27] A pentathlon, based on the ancient Greek event, had been introduced at the 1906 Intercalated Games.[28] The 1912 version consisted of the long jump, javelin throw, 200-meter dash, discus throw and 1500-meter run.[27]

The decathlon was a relatively new event in modern athletics, although a similar competition known as the all-around championship had been part of American track meets since the 1880s and a version had been featured on the program of the 1904 St. Louis Olympics. The events of the new decathlon differed slightly from the American version.[29][30] Both seemed appropriate for Thorpe, who was so versatile that he served as Carlisle's one-man team in several track meets.[7] According to his obituary in The New York Times, he could run the 100-yard dash in 10 seconds flat; the 220 in 21.8 seconds; the 440 in 51.8 seconds; the 880 in 1:57, the mile in 4:35; the 120-yard high hurdles in 15 seconds; and the 220-yard low hurdles in 24 seconds.[7] He could long jump 23 ft 6 in and high-jump 6 ft 5 in.[7] He could pole vault 11 feet; put the shot 47 ft 9 in; throw the javelin 163 feet; and throw the discus 136 feet.[7]

Thorpe entered the U.S. Olympic trials for both the pentathlon and the decathlon. He easily earned a place on the pentathlon team, winning three events. The decathlon trial was subsequently cancelled, and Thorpe was chosen to represent the U.S. in the event.[31] The pentathlon and decathlon teams also included future International Olympic Committee president Avery Brundage.[32]

His schedule in the Olympics was busy. Along with the decathlon and pentathlon, he competed in the long jump and high jump. The first competition was the pentathlon. He won four of the five events and placed third in the javelin, an event he had not competed in before 1912. Although the pentathlon was primarily decided on place points, points were also earned for the marks achieved in the individual events. He won the gold medal. That same day, he qualified for the high jump final in which he placed fourth, and also took seventh place in the long jump. Even more remarkably, because someone had stolen his shoes just before he was due to compete, he found some discarded ones in a rubbish bin and won his medals wearing them.[33]

| Olympic medal record | ||

|---|---|---|

| Men's athletics | ||

| Representing the | ||

| 1912 Stockholm | Decathlon | |

| 1912 Stockholm | Pentathlon | |

Thorpe's final event was the decathlon, his first (and as it turned out, his only) decathlon.[34][35] Strong competition from local favorite Hugo Wieslander was expected. Thorpe, however, easily defeated Wieslander by more than 700 points. He placed in the top four in all ten events, and his Olympic record of 8,413 points would stand for nearly two decades.[19] Overall, Thorpe won eight of the 15 individual events comprising the pentathlon and decathlon.[36]

As was the custom of the day, the medals were presented to the athletes during the closing ceremonies of the games. Along with the two gold medals, Thorpe also received two challenge prizes, which were donated by King Gustav V of Sweden for the decathlon and Czar Nicholas II of Russia for the pentathlon. Several sources recount that, when awarding Thorpe his prize, King Gustav said, "You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world", to which Thorpe replied, "Thanks, King".[37][38] Contemporary sources are lacking, however, suggesting that the story is apocryphal.[39] The anecdote appeared in newspapers as early as 1948, 36 years after his appearance in the Olympics,[40] and in books as early as 1952.[41]

Thorpe's successes had not gone unnoticed at home, and on his return he was the star attraction in a ticker-tape parade on Broadway.[37] He remembered later, "I heard people yelling my name, and I couldn't realize how one fellow could have so many friends."[37]

Apart from his track and field appearances, he also played in one of two exhibition baseball games at the 1912 Olympics, which featured two teams composed mostly of U.S. track and field athletes.[42] Thorpe had previous experience in the sport, as the public would soon learn.[43]

All-Around champion

After his victories at the Olympic Games in Sweden, on September 2, 1912, he returned to Celtic Park, the home of the Irish American Athletic Club, in Queens, New York (where he had qualified four months earlier for the Olympic Games), to compete in the Amateur Athletic Union's All-Around Championship. Competing against Bruno Brodd of the Irish American Athletic Club and J. Bredemus of Princeton University, he won seven of the ten events contested and came in second in the remaining three. With a total point score of 7,476 points, Thorpe broke the previous record of 7,385 points set in 1909, (also set at Celtic Park), by Martin Sheridan, the champion athlete of the Irish American Athletic Club.[44] Sheridan, a five-time Olympic gold medalist, was present to watch his record broken, approached Thorpe after the event and shook his hand saying, "Jim, my boy, you're a great man. I never expect to look upon a finer athlete." He told a reporter from New York World, "Thorpe is the greatest athlete that ever lived. He has me beaten fifty ways. Even when I was in my prime, I could not do what he did today."[45]

Controversy

In 1912, strict rules regarding amateurism were in effect for athletes participating in the Olympics. Athletes who received money prizes for competitions, were sports teachers or had competed previously against professionals were not considered amateurs and were barred from competition.[46]

In late January 1913, the Worcester Telegram published a story announcing that Thorpe had played professional baseball, and other U.S. newspapers followed up the story.[37][47] Thorpe had indeed played professional baseball in the Eastern Carolina League for Rocky Mount, North Carolina, in 1909 and 1910, receiving meager pay; reportedly as little as US$2 ($65 today) per game and as much as US$35 ($1,145 today) per week.[48] College players, in fact, regularly spent summers playing professionally but most used aliases, unlike Thorpe.[18]

Although the public did not seem to care much about Thorpe's past,[49] the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), and especially its secretary James Edward Sullivan, took the case very seriously.[50] Thorpe wrote a letter to Sullivan, in which he admitted playing professional baseball:[37]

I hope I will be partly excused by the fact that I was simply an Indian schoolboy and did not know all about such things. In fact, I did not know that I was doing wrong, because I was doing what I knew several other college men had done, except that they did not use their own names ...

His letter did not help.[51] The AAU decided to withdraw Thorpe's amateur status retroactively.[52] Later that year, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) unanimously decided to strip Thorpe of his Olympic titles, medals and awards and declare him a professional.[53][54][55]

Although Thorpe had played for money, the AAU and IOC did not follow the rules for disqualification. The rulebook for the 1912 Olympics stated that protests had to be made "within" 30 days from the closing ceremonies of the games.[24] The first newspaper reports did not appear until January 1913, about six months after the Stockholm Games had concluded.[24] There is also some evidence that Thorpe was known to have played professional baseball before the Olympics, but the AAU had ignored the issue until being confronted with it in 1913.[56][57] The only positive element of this affair for Thorpe was that, as soon as the news was reported that he had been declared a professional, he received offers from professional sports clubs.[58]

Professional career

Baseball free agent

| Jim Thorpe | |

|---|---|

Thorpe as a member of the New York Giants | |

| Outfielder | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 14, 1913, for the New York Giants | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| September 25, 1919, for the Boston Braves | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .252 |

| Home runs | 7 |

| Runs batted in | 82 |

| Hits | 176 |

| Teams | |

| |

Because the minor league team that last held Jim Thorpe's contract had disbanded in 1910, he found himself in the rare position of being a sought-after free agent at the major league level during the era of the reserve clause, and thus had a choice of baseball teams for which to play.[59] In January 1913, he turned down a starting position with the American League cellar-dwelling St. Louis Browns, choosing instead to join the 1912 National League champion New York Giants, who, with Thorpe playing in 19 of their 151 games, would repeat as the 1913 National League champions. Immediately following the Giants' October loss in the 1913 World Series, Thorpe and the Giants joined the Chicago White Sox for a world tour.[60] Barnstorming across the United States and then around the world, Thorpe was the celebrity of the tour.[61] Thorpe's presence increased the publicity, attendance and gate receipts for the tour.[62] He met with Pope Pius X and Abbas II Hilmi Bey (the last Khedive of Egypt), and played before 20,000 people in London including King George V.[62][63]

Baseball, football, and basketball

Thorpe signed with the New York Giants baseball club in 1913 and played sporadically with them as an outfielder for three seasons. After playing in the minor leagues with the Milwaukee Brewers in 1916,[64] he returned to the Giants in 1917 but was sold to the Cincinnati Reds early in the season. In the "double no-hitter" between Fred Toney of the Reds and Hippo Vaughn of the Chicago Cubs, Thorpe drove in the winning run in the 10th inning.[65] Late in the season, he was sold back to the Giants. Again, he played sporadically for them in 1918 before being traded to the Boston Braves on May 21, 1919, for Pat Ragan. In his career, he amassed 91 runs scored, 82 runs batted in and a .252 batting average over 289 games.[66] He continued to play minor league baseball until 1922.[67]

But Thorpe had not abandoned football either. He first played professional football in 1913 as a member of the Indiana-based Pine Village Pros, a team that had a several-season winning streak against local teams during the 1910s.[68] He then signed with the Canton Bulldogs in 1915. They paid him $250 ($7,530 today) a game, a tremendous wage at the time.[69] Before signing him Canton was averaging 1,200 fans a game, but 8,000 showed up for his debut against the Massillon Tigers.[69] The team won titles in 1916, 1917, and 1919. He reportedly ended the 1919 championship game by kicking a wind-assisted 95-yard punt from his team's own 5-yard line, effectively putting the game out of reach.[69] In 1920, the Bulldogs were one of 14 teams to form the American Professional Football Association (APFA), which would become the National Football League (NFL) two years later. Thorpe was nominally the APFA's first president, but spent most of the year playing for Canton and a year later was replaced as president by Joseph Carr.[70] He continued to play for Canton, coaching the team as well. Between 1921 and 1923, he helped organize and played for the Oorang Indians (LaRue, Ohio), an all-Native American team.[71] Although the team's record was 3–6 in 1922,[72] and 1–10 in 1923,[73] he played well and was selected for the Green Bay Press-Gazette's first All-NFL team in 1923, which would later be formally recognized by the NFL as the league's official All-NFL team in 1931).[74]

Thorpe never played for an NFL championship team. He retired from professional football at age 41,[15] having played 52 NFL games for six teams from 1920 to 1928.[75]

Until 2005, most of Thorpe's biographers were unaware of his basketball career until a ticket that documented his time in professional basketball was discovered in an old book that year.[76] By 1926, he was the main feature of the "World Famous Indians" of LaRue, a traveling basketball team.[77] "Jim Thorpe's world famous Indians" barnstormed for at least two years (1927–28) in multiple states.[76] Although stories about Thorpe's team were published in some local newspapers at the time, his basketball career had not been well-documented afterwards.[78]

Marriage and family

Thorpe married three times and had eight children (one of whom died in childhood). In 1913, Thorpe married Iva M. Miller,[7] whom he had met at Carlisle. In 1917, Iva and Thorpe bought a house now known as the Jim Thorpe House in Yale, Oklahoma, and lived there until 1923.[79] They had four children: Gail, James F., Charlotte, and Frances.[7] Miller filed for divorce from Thorpe in 1925, claiming desertion.[80]

In 1926, Thorpe married Freeda Verona Kirkpatrick (September 19, 1905 – March 2, 2007). She was working for the manager of the baseball team for which he was playing at the time.[81] They had four sons: Phillip, William, Richard, and John.[7] Kirkpatrick divorced Thorpe in 1941, after they had been married for 15 years.[81]

Lastly, Thorpe married Patricia Gladys Askew on June 2, 1945;[7] she was with him when he died.[82]

Later life and death

After his athletic career, Thorpe struggled to provide for his family. He found it difficult to work a non-sports-related job and never held a job for an extended period of time. During the Great Depression in particular, he had various jobs, among others as an extra for several movies, usually playing an American Indian chief in Westerns. He also worked as a construction worker, a doorman (bouncer), a security guard and a ditch digger, and briefly joined the United States Merchant Marine in 1945.[83][84] Thorpe was a chronic alcoholic during his later life.[85]

He ran out of money sometime in the early 1950s. When hospitalized for lip cancer in 1950, Thorpe was admitted as a charity case.[86] At a press conference announcing the procedure, his wife, Patricia, wept and pleaded for help, saying, "We're broke ... Jim has nothing but his name and his memories. He has spent money on his own people and has given it away. He has often been exploited."[86]

In early 1953, Thorpe went into heart failure for the third time while dining with Patricia in their home in Lomita, California. He was briefly revived by artificial respiration and spoke to those around him, but lost consciousness shortly afterward and died on March 28 at the age of 65.[7]

Victim of racism

Thorpe, whose parents were both half Caucasian, was raised as an American Indian. His accomplishments occurred during a period of severe racial inequality in the United States. It has often been suggested that his medals were stripped because of his ethnicity.[87] While it is difficult to prove this, the public comment at the time largely reflected this view.[88] At the time Thorpe won his gold medals, not all Native Americans were recognized as U.S. citizens. (The U.S. government had wanted them to make concessions to adopt European-American ways to receive such recognition.) Citizenship was not granted to all American Indians until 1924.[89]

While Thorpe attended Carlisle, students' ethnicity was used for marketing purposes.[90] The football team was called the Indians. A photograph of Thorpe and the 1911 football team emphasized racial differences among the competing athletes; the inscription on the most important game ball of that season reads, "1911, Indians 18, Harvard 15."[91] Additionally, the school and journalists often categorized sporting competitions as conflicts of Indians against whites; newspaper headlines such as "Indians Scalp Army 27–6" or "Jim Thorpe on Rampage" made stereotypical journalistic play of the Indian background of Carlisle's football team.[90] The first notice of Thorpe in The New York Times was headlined "Indian Thorpe in Olympiad; Redskin from Carlisle Will Strive for Place on American Team."[22] His accomplishments were described in a similar racial context by other newspapers and sportswriters throughout his life.[92]

Legacy

Olympic awards reinstated

Over the years, supporters of Thorpe attempted to have his Olympic titles reinstated.[93] US Olympic officials, including former teammate and later president of the IOC Avery Brundage, rebuffed several attempts, with Brundage once saying, "Ignorance is no excuse."[20] Most persistent were the author Robert Wheeler and his wife, Florence Ridlon. They succeeded in having the AAU and United States Olympic Committee overturn its decision and restore Thorpe's amateur status before 1913.[94]

In 1982, Wheeler and Ridlon established the Jim Thorpe Foundation and gained support from the U.S. Congress. Armed with this support and evidence from 1912 proving that Thorpe's disqualification had occurred after the 30-day time period allowed by Olympics rules, they succeeded in making the case to the IOC. In October 1982, the IOC Executive Committee approved Thorpe's reinstatement.[48] In an unusual ruling, they declared that Thorpe was co-champion with Ferdinand Bie and Wieslander, although both of these athletes had always said they considered Thorpe to be the only champion. In a ceremony on January 18, 1983, the IOC presented two of Thorpe's children, Gale and Bill, with commemorative medals.[48] Thorpe's original medals had been held in museums, but they had been stolen and have never been recovered.[95] Although Thorpe is listed as a gold medalist by the IOC, his results from 1912 have not been restored to the official Olympic records.[96]

Honors

Thorpe's monument, featuring the quote from Gustav V ("You, sir, are the greatest athlete in the world."), still stands near the town named for him, Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania.[17] The grave rests on mounds of soil from Thorpe's native Oklahoma and from the stadium in which he won his Olympic medals.[97]

Thorpe's achievements received great acclaim from sports journalists, both during his lifetime and since his death. In 1950, an Associated Press poll of almost 400 sportswriters and broadcasters voted Thorpe the "greatest athlete" of the first half of the 20th century.[98] That same year, the Associated Press named Thorpe the "greatest American football player" of the first half of the century.[99] In 1999, the Associated Press placed him third on its list of the top athletes of the century, following Babe Ruth and Michael Jordan.[100] ESPN ranked Thorpe seventh on their list of best North American athletes of the century.[101]

Thorpe was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1963, one of seventeen players in the charter class.[102] Thorpe is memorialized in the Pro Football Hall of Fame rotunda with a larger-than-life statue. He was also inducted into halls of fame for college football, American Olympic teams, and the national track and field competition.[18]

President Richard Nixon, as authorized by U.S. Senate Joint Resolution 73, proclaimed Monday, April 16, 1973, as "Jim Thorpe Day" to promote the nationwide recognition of Thorpe.[103] In 1986, the Jim Thorpe Association established an award with Thorpe's name. The Jim Thorpe Award is given annually to the best defensive back in college football. The annual Thorpe Cup athletics meeting is named in his honor.[104] The United States Postal Service issued a 32¢ stamp on February 3, 1998 as part of the Celebrate the Century stamp sheet series.[105]

In a poll of sports fans conducted by ABC Sports, Thorpe was voted the Greatest Athlete of the Twentieth Century out of 15 other athletes including Muhammad Ali, Babe Ruth, Jesse Owens, Wayne Gretzky, Jack Nicklaus, and Michael Jordan.[106][107] In 2015, proposed designs for the 2018 Native American dollar coin featuring Thorpe were released.[108]

Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania

After Thorpe's funeral was held at St. Benedict's Catholic Church in Shawnee, Oklahoma,[109] his body lay in state at Fairview Cemetery after citizens had paid to have it moved to Shawnee by train from California.[110] The people began a fund-raising effort to erect a memorial for Thorpe at the town's athletic park. Local officials had asked state legislators for funding, but a bill that included $25,000 for their proposal was vetoed by Governor Johnston Murray.[111] Meanwhile, Thorpe's third wife, unbeknownst to the rest of his family, took Thorpe's body and had it shipped to Pennsylvania when she heard that the small Pennsylvania towns of Mauch Chunk and East Mauch Chunk were seeking to attract business.[112][113] She made a deal with officials which, according to Thorpe's son Jack, was done by Patricia for monetary considerations.[114] The towns bought Thorpe's remains, erected a monument to him, merged, and renamed the newly united town in his honor Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, even though Thorpe had never been there.[115] The monument site contains his tomb,[116] two statues of him in athletic poses,[117] and historical markers describing his life story.[118]

In June 2010, Jack Thorpe filed a federal lawsuit against the borough of Jim Thorpe, seeking to have his father's remains returned to his homeland and re-interred near other family members in Oklahoma. Citing the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, Jack was arguing to bring his father's remains to the reservation in Oklahoma, where they would be buried near those of his father, sisters and brother, a mile from the place he was born. He claimed that the agreement between his stepmother and Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania, borough officials was made against the wishes of other family members who want him buried in Native American land.[119][120] Jack Thorpe died at 73 on February 22, 2011.[121]

In April 2013, U.S. District Judge Richard Caputo ruled that Jim Thorpe borough amounts to a museum under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act ("NAGPRA"). A lawyer for Bill and Richard Thorpe said the men would pursue the legal process to have their father returned to Sac and Fox land in central Oklahoma.[122] On October 23, 2014, the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed Judge Caputo's ruling. The appeals court held that Jim Thorpe borough is not a "museum", as that term is used in NAGPRA, and that the plaintiffs therefore could not invoke that federal statute to seek reinterment of Thorpe's remains.[116] In NAGPRA language, "'museum' means any institution or State or local government agency (including any institution of higher learning) that receives Federal funds and has possession of, or control over, Native American cultural items."[123] The Court of Appeals directed the trial court to enter a judgment in favor of the borough.[116] The appeals court said Pennsylvania law allows the plaintiffs to ask a state court to order reburial of Thorpe's remains, but noted, "once a body is interred there is great reluctance in permitting same to be moved, absent clear and compelling reasons for such a move."[124] On October 5, 2015, the United States Supreme Court refused to hear the matter, effectively bringing the legal process to an end.[125]

In film

In the 1930s, Thorpe appeared in several short films and features. Usually, his roles were cameo appearances as an Indian, although in the 1932 comedy, Always Kickin, Thorpe was prominently cast in a speaking part as himself, a kicking coach teaching young football players to drop-kick. In 1931, during the Great Depression, he sold the film rights to his life story to MGM for $1,500 ($30,000 today).[126][127] Thorpe portrayed an umpire in the 1940 film Knute Rockne, All American.[128] He played a member of the Navajo Nation in the 1950 film Wagon Master.[129]

Thorpe was memorialized in the Warner Bros. film Jim Thorpe – All-American (1951) starring Burt Lancaster, with Billy Gray performing as Thorpe as a child. The film was directed by Michael Curtiz. Although there were rumors that Thorpe received no money, he was paid $15,000 by Warner Bros. plus a $2,500 donation toward an annuity for him by the studio head of publicity.[130] The movie included archival footage of the 1912 and 1932 Olympics.[131] Thorpe was seen in one scene as a coaching assistant.[131] It was also distributed in the United Kingdom, where it was called Man of Bronze.[132]

Notes

- ^ "Hall of Famers by Jersey Number". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 6, 2017.

- ^ a b Sources vary. See, for example, Flatter, Ron. "Thorpe preceded Deion, Bo", ESPN. Retrieved December 9, 2016, and

Golus, Carrie (2012). Jim Thorpe (Revised Edition), Twenty-First Century Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4677-0397-0. - ^ Cook. pg. 115

- ^ "Jim Thorpe Biography". Encyclopedia of World Biography. Retrieved November 13, 2011.

- ^ a b Golus, Carrie (August 1, 2012). Jim Thorpe (Revised Edition). Twenty-First Century Books. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-4677-0397-0.

- ^ a b O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pg. 129

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Jim Thorpe Is Dead On West Coast at 64", The New York Times, March 29, 1953. Retrieved October 26, 2013.

- ^ a b Wheeler. pg. 291

- ^ "Bellemont: "Ghost" town of Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma". Rootsweb. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

- ^ "Author of Jim Thorpe's biography shakes things up". Times News Online. November 22, 2010. Retrieved May 2, 2015.

- ^ Hannigan, Dave (August 3, 2016). "America at Large: Bizarre coda to Olympian Jim Thorpe's epic life". The Irish Times. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ Redmond, Patrick R. (2014). The Irish and the Making of American Sport, 1835–1920. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company. p. 279. ISBN 978-1-4766-0584-5.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe Leaps To Fame On Carlisle Athletic Field". The Washington Post. December 15, 1912. p. 2. Retrieved October 24, 2015 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pg. 131

- ^ a b Jim Thorpe – Fast facts, cgmworldwide.com. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c Jim Thorpe – Olympic Hero and Native American, olympics30.com. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ a b c Hoxie. pg. 628

- ^ a b c d e Botelho, Greg. "Roller-coaster life of Indian icon, sports' first star", CNN.com, July 14, 2004. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of World Biography. Jim Thorpe, Thomson-Gale, Bookrags, June 2006. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ a b "Jim Thorpe cruelly treated by authorities". CNN Sports Illustrated. Reuters. August 8, 2004. Archived from the original on November 14, 2007. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e Jeansonne. pg. 60

- ^ a b "Indian Thorpe in Olympiad: Redskin from Carlisle Will Strive for Place on American Team", The New York Times, April 28, 1912. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ Buford. pg. 151

- ^ a b c Jim Thorpe, usoc.org, Retrieved April 26, 2007. Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pg. 144

* Jim Thorpe, profootballhalloffame.com. Retrieved April 23, 2007. - ^ Buford. pg. 113

- ^ a b Buford. pg. 112

- ^ Zarnowski (2013). pg. 150

- ^ Zarnowski (2005). pgs. 29–30, 240

- ^ "Athletics at the 1904 St. Louis Summer Games: Men's All-Around Championship". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 25, 2018.

- ^ Buford. pg. 114

- ^ Findling and Pelle. pgs. 473–4

- ^ "Battle over athlete Jim Thorpe's burial site continues". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe". National Track and Field Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe". Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- ^ Jenkins, Sally (August 10, 2012). "Greatest Olympic athlete? Jim Thorpe, not Usain Bolt". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 7, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Flatter, Ron. "Thorpe preceded Deion, Bo", ESPN.com. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe, Sac and Fox Athlete" by Bob Berontas, Chelsea House Publications (London, 1993), ISBN 978-0-7910-1722-7.

- ^ Kate Buford, Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe (Random House Digital, 2010).

- ^ e.g., "Sports in Brief", Amarillo (TX) Daily News, Saturday, March 13, 1948, pg. 2 (available at newspaperarchive.com).

- ^ John Durant and Otto Bettmann, Pictorial History of American Sports, from Colonial Times to the Present (A. S. Barnes, 1952) pg. 143.

- ^ Cava. pgs. 8–9

- ^ Buford. pgs. 158–61

- ^ "Indian Thorpe is Best Athlete – Olympic Champion Wins All-Around Championship and Breaks Record". The New York Times, September 3, 1912.

- ^ Wheeler. pg. 118

- ^ Buford. pg. 121

- ^ ""Jim" Thorpe Admits He Is Professional, and Retires from Athletics", The Washington Post, January 28, 1913, pg. 8. "Charges that Thorpe had played professional baseball in Winston Salem, N.C. were first published in a Worcester (Mass.) newspaper last week."

- ^ a b c Anderson, Dave. "Jim Thorpe's Family Feud", The New York Times, February 7, 1983. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Schaffer and Smith. pg. 50.

- ^ Schaffer and Smith. pg. 40.

- ^ Buford. pg. 161

- ^ Campagna, Jeff (May 28, 2010). "Wishing Jim Thorpe a Happy Birthday". Smithsonian. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ Buford. pg. 167

- ^ Thomas, Louisa (July 29, 2016). "Doping and an Olympic Crisis of Idealism". The New Yorker. Retrieved May 11, 2017.

- ^ Quirk. pg. 42

- ^ Buford. pg. 162

- ^ Dyreson. pg. 171

- ^ Rogge, Johnson, and Rendell. pg. 60

- ^ "Thorpe is to Play Ball with Giants; Famous Indian Athlete Accepts McGraw's Terms Over the Telephone", The New York Times, February 1, 1913. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- ^ "Sox and Giants on World's Tour; Comiskey-McGraw Party Leaves Chicago Oct 19 and Arrives in New York March 6", The New York Times. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Elfers. pg. 210

- ^ a b Clavin, Tom. "The Inside Story of Baseball's Grand World Tour of 1914", Smithsonian, March 21, 2014. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Elfers. pgs. 185–7, 233

- ^ "Jim Thorpe's Speed Big Hit In A.A." The Janesville Daily Gazette , July 10, 1916. Retrieved January 19, 2017.

- ^ Daley, Arthur. "Baseball's 'Ten Greatest Moments'", The New York Times, April 17, 1949. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Jim Thorpe, baseball-reference.com. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Buford. pg. 232

- ^ "NFL History by Decade, 1911–1920". National Football League. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- ^ a b c Neft, Cohen, and Korch. pg. 18

- ^ Neft, Cohen, and Korch. pg. 20

- ^ C. Richard King (2006). Native athletes in sport & society: a reader. Bison Books. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-8032-7828-4.

- ^ Neft, Cohen, and Korch. pg. 34

- ^ Neft, Cohen, and Korch. pg. 40

- ^ Neft, Cohen, and Korch. pg. 41

- ^ "Jim Thorpe". Pro Football Reference. Retrieved July 23, 2013.

- ^ a b "History Detectives – Episode 10, 2005: Jim Thorpe Ticket, Jamestown, New York" (PDF). pbs.org. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ Buford. pgs. 253–4

- ^ Pennington, Bill. "Jim Thorpe and a Ticket to Serendipity", The New York Times, March 29, 2005. Retrieved May 25, 2017.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Inventory – Nomination Form" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved December 19, 2014.

- ^ List of marriages, divorces, births, and deaths, Time, April 6, 1925, available online via time.com. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ a b "Athlete Thorpe's 2nd wife, Freeda, dies at 101". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Associated Press. March 7, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

- ^ Buford. pg. 366

- ^ O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pgs. 144–5

- ^ Briefs, Time, February 22, 1943, available online via time.com. Retrieved May 21, 2007.

- ^ Jeansonne. pg. 61

- ^ a b Associated Press. "Thorpe Has Cancerous Growth Removed From Lip in Hospital at Philadelphia", The New York Times, November 10, 1951. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Watterson. pg. 151

* Elfers. pg. 18 - ^ Schaffer and Smith. pg. 50

- ^ Lincoln and Slagle. pg. 282

- ^ a b Bloom quoted in Bird. pg. 97

- ^ Jim Thorpe Photo Collection, historicalsociety.com. Retrieved May 14, 2007.

- ^ Demaree, Al. "Thorpe, the Indian, Best All-American", Los Angeles Times, November 24, 1926. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

* "Jim Thorpe Dies of Heart Attack at 64" Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1953. Retrieved July 6, 2017.

* Roetman, Sheena L. "America's Greatest Athlete Ever, Jim Thorpe, Was Indigenous", Vice Media, November 27, 2014. Retrieved January 4, 2018. - ^ Anderson, Dave. "Jim Thorpe's Medals", The New York Times, June 22, 1975. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ^ Wethe, David and Whiteley, Michael. "Legends lunches begin this fall with Bob Lilly", Dallas Business Journal, July 19, 2002. Retrieved April 27, 2007.

- ^ O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pg 132

- ^ Jenkins, Sally (July 2012). "Why Are Jim Thorpe's Olympic Records Still Not Recognized?". Smithsonian. Retrieved August 15, 2016.

- ^ Jim Thorpe, Pennsylvania: Jim Thorpe's Tourist Attraction Grave, Roadside America. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe", Archived September 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine encarta.msn.com. Retrieved April 23, 2007. Archived October 3, 2009.

- ^ Jim Thorpe Biography, cgmworldwide.com. Retrieved April 23, 2007.

- ^ Associated Press. Top 100 athletes of the 20th century, Archived March 12, 2009, at the Wayback Machine USA Today, December 21, 1999. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ "Top N. American athletes of the century", espn.com. Retrieved March 15, 2007.

- ^ "Hall of Famers by Year of Enshrinement". Pro Football Hall of Fame. Retrieved September 6, 2012.

- ^ Richard Nixon: Proclamation 4209 – Jim Thorpe Day, The American Presidency Project. Retrieved November 8, 2016.

- ^ "16 Jahre "Thorpe Cup"". Zehnkampf.de (in German). Archived from the original on April 5, 2010. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "American Indian Subjects on United States Postage Stamps" (PDF). United States Postal Service. February 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 30, 2013. Retrieved July 28, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Wide World of Sports athlete of the century". ESPN Network. January 14, 2000. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe: All-Around Athlete and American Indian Advocate". Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved February 6, 2012.

- ^ Unser, Mike (November 6, 2015). 2018 "Native American $1 Coin Designs Depict Jim Thorpe". Coin News. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe Body Arrives Home For Burial Rite". The Wilmington News. United Press. April 13, 1953. p. 9. Retrieved July 14, 2016.

- ^ Buford. pgs. 367–9

- ^ Wheeler. pgs. 228–9

- ^ Hagerty, James R. (July 21, 2010). "Is There Life After Jim Thorpe For Jim Thorpe, Pa.?". The Wall Street Journal. p. A14.

- ^ Zucchino, David (October 18, 2013). "Jim Thorpe, Pa., fights to keep its namesake". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ "Frank Deford of Real Sports with Bryant Gumbel interviews Jack Thorpe". HBO (official channel on YouTube). Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pg. 148

- ^ a b c "Pennsylvania town named for Jim Thorpe can keep athlete's body". CBS News. October 23, 2014. Retrieved October 24, 2014.

- ^ Hedes, Jarrad (May 19, 2017). "Jim Thorpe plans to add third Olympian statue". Lehighton Times News. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ Loverro, Thom (August 2, 2013). "Jim Thorpe sleeps on – for now – in town where everyone knows his name". The Guardian. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- ^ Lee, Peggy (June 24, 2010). "Son Of Jim Thorpe Sues for His Remains". wnep.com. Archived from the original on March 1, 2012. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Jim Thorpe's son sues town of Jim Thorpe over location of athlete's remains". The Patriot-News. Associated Press. June 24, 2010. Retrieved May 19, 2017.

- ^ "Jim Thorpe's son Jack dies". Retrieved July 9, 2012.

- ^ "Judge Sides With Sons About Legendary Athlete Jim Thorpe's Remains". KOTV-DT. April 21, 2013. Retrieved April 21, 2013.

- ^ 25 USC Ch. 32: Native American Graves Protection And Repatriation. Office of the Law Revision Counsel. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

- ^ John Thorpe (et al) v. Borough of Jim Thorpe, No. 13-2446 (3d Cir.).Retrieved September 9, 2016

- ^ Hall, Peter (October 6, 2015). "U.S. Supreme Court: Jim Thorpe's body to remain in town that bears his name". Pocono Record. Retrieved October 13, 2015.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ O'Hanlon-Lincoln. pg. 145

- ^ Buford. pgs. 313–4

- ^ Hilger. pg. 324

- ^ Kate Buford, Native American Son, The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe, Alfred A. Knopf (New York, 2010), pg. 356. ISBN 978-0-375-41324-7.

- ^ a b Thorp, Charles. "8 Olympic Movies That Medal". Men's Journal. Retrieved June 15, 2017.

- ^ Williams. pg. 133

Sources

- Bird. Elizabeth S. Dressing in Feathers: The Construction of the Indian in American Popular Culture. Boulder: Westview Press, 1996. ISBN 0-8133-2667-2

- Bloom, John. There is a Madness in the Air: The 1926 Haskell Homecoming and Popular Representations of Sports in Federal and Indian Boarding Schools. ed. in Bird. Boulder: Westview Press. 1996. ISBN 0-8133-2667-2

- Buford, Kate. Native American Son: The Life and Sporting Legend of Jim Thorpe. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-8032-4089-6

- Cava, Pete (Summer 1992). "Baseball in the Olympics". Citius, Altius, Fortius. 1 (1): 7–15. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- Cook, William A. Jim Thorpe: A Biography. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2011. ISBN 978-0-7864-6355-8

- Dyreson, Mark. Making the American Team: Sport, Culture, and the Olympic Experience. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0-252-06654-2

- Elfers, James E. The Tour to End All Tours. Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8032-6748-7

- Findling, John E. and Pelle, Kimberly D., eds. Encyclopedia of the Modern Olympic Movement. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-313-32278-5

- Gerasimo, Luisa and Whiteley, Sandra. The Teacher's Calendar of Famous Birthdays. McGraw-Hill, 2003. ISBN 0-07-141230-1

- Hilger, Michael. Native Americans in the Movies: Portrayals from Silent Films to the Present. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015. ISBN 978-1-4422-4002-5

- Hoxie, Frederick E. Encyclopedia of North American Indians. New York: Houghton Mifflin Books, 1996. ISBN 0-395-66921-9

- Jeansonne, Glen. A Time of Paradox: America Since 1890. Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. ISBN 0-7425-3377-8

- Landrum, Dr. Gene. Empowerment: The Competitive Edge in Sports, Business & Life. Brendan Kelly Publishing Incorporated, 2006. ISBN 1-895997-24-0

- Lincoln, Kenneth and Slagle, Al Logan. The Good Red Road: Passages into Native America. University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN 0-8032-7974-4

- Magill, Frank Northern. Great Lives from History. New York: Salem Press, 1987. ISBN 0-89356-529-6

- Neft, David S., Cohen, Richard M., and Korch, Rick. The Complete History of Professional Football from 1892 to the Present. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1994. ISBN 0-312-11435-4

- O'Hanlon-Lincoln, Ceane. Chronicles: A Vivid Collection of Fayette County, Pennsylvania Histories. Mechling Bookbindery, 2006. ISBN 0-9760563-4-8

- Quirk, Charles E., ed. Sports and the Law: Major Legal Cases. London: Routledge, 2014. ISBN 978-1-135-68222-4

- Rogge, M. Jacque, Johnson, Michael, and Rendell, Matt. The Olympics: Athens to Athens 1896–2004. Sterling Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-297-84382-6

- Schaffer, Kay and Smith, Sidonie. The Olympics at the Millennium: Power, Politics and the Games. Rutger University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8135-2820-8

- Watterson, John Sayle. College Football: history, spectacle, controversy. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8018-7114-X

- Wheeler, Robert W. Jim Thorpe, World's Greatest Athlete. University of Oklahoma Press, 1979. ISBN 0-8061-1745-1

- Williams, Randy. Sports Cinema 100 Movies: The Best of Hollywood's Athletic Heroes, Losers, Myths, and Misfits. Pompton Plains: Limelight Editions, 2006. ISBN 978-0-87910-331-6

- Zarnowski, Frank. All-Around Men: Heroes of a Forgotten Sport. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0-8108-5423-9

- Zarnowski, Frank. The Pentathlon of the Ancient World. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2013. ISBN 978-0-7864-6783-9

Further reading

- Benjey, Tom. Doctors, Lawyers, Indian Chiefs. Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Tuxedo Press, 2008. ISBN 978-0-9774486-7-8

- "In the Matter of Jacobus Franciscus Thorpe" in Bill Mallon and Ture Widlund, The 1912 Olympic Games — Results for All Competitors in All Events, with Commentary. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2002. ISBN 0-7864-1047-7

- Newcombe, Jack. The Best of the Athletic Boys: The White Man's Impact on Jim Thorpe. Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1975. ISBN 0-385-06186-2

- Updyke, Rosemary Kissinger. Jim Thorpe, the Legend Remembered. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican, 1997. ISBN 1-56554-539-7

- Wallechinsky, David. The Complete Book of the Summer Olympics. Woodstock, New York: Overlook Press, 2000. ISBN 1-58567-046-4

External links

- Jim Thorpe at the Pro Football Hall of Fame

- Jim Thorpe at the College Football Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from NFL.com · Pro Football Reference

- Coaching record at Pro-Football-Reference.com

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball Reference, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Jim Thorpe at IMDb

- Voices of Oklahoma interview with Bill Thorpe. First person interview conducted on August 3, 2015, with Bill Thorpe about his father, Jim Thorpe.

- 1887 births

- 1953 deaths

- Akron Buckeyes players

- All-American college football players

- American ballroom dancers

- American male film actors

- American pentathletes

- American male decathletes

- American football drop kickers

- American football running backs

- American sailors

- American people of French descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American people of Native American descent

- American Roman Catholics

- Athletes (track and field) at the 1912 Summer Olympics

- Baseball controversies

- Baseball players at the 1912 Summer Olympics

- Baseball players from Oklahoma

- Basketball players from Oklahoma

- Basketball players from Pennsylvania

- Boston Braves players

- Canton Bulldogs coaches

- Canton Bulldogs players

- Canton Bulldogs (Ohio League) players

- Carlisle Indians baseball players

- Carlisle Indians football players

- Chicago Cardinals players

- Cincinnati Reds players

- Cleveland Indians (NFL) players

- Cleveland Tigers-Indians coaches

- College Football Hall of Fame inductees

- American men's basketball players

- Fayetteville Highlanders players

- Harrisburg Senators players

- Hartford Senators players

- Identical twins

- Indiana Hoosiers football coaches

- Jersey City Skeeters players

- Major League Baseball outfielders

- Male actors from Oklahoma

- Medalists at the 1912 Summer Olympics

- Milwaukee Brewers (minor league) players

- National Football League commissioners

- National Football League founders

- Native American male actors

- Native American sportspeople

- New York Giants (NL) players

- New York Giants players

- Newark Indians players

- Olympic baseball players of the United States

- Olympic gold medalists for the United States in track and field

- Olympic pentathletes

- Olympic track and field athletes of the United States

- Oorang Indians players

- People from Carlisle, Pennsylvania

- People from Lincoln County, Oklahoma

- People from Lomita, California

- People from Pottawatomie County, Oklahoma

- Players of American football from Oklahoma

- Portland Beavers players

- Pro Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Rock Island Independents players

- Rocky Mount Railroaders players

- Sac and Fox people

- Sportspeople from Shawnee, Oklahoma

- Toledo Mud Hens players

- 20th-century American male actors

- Twin people from the United States

- Twin sportspeople

- Worcester Boosters players