Doris Day

Doris Day | |

|---|---|

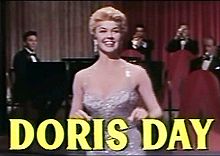

Doris Day in 1957 | |

| Born | Doris Mary Ann Kappelhoff[1] April 3, 1922 Cincinnati, Ohio, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Actress, Singer, animal rights activist |

| Years active | 1939–1989 |

| Spouse(s) |

Al Jorden

(m. 1941; div. 1943)Barry Comden

(m. 1976; div. 1981) |

| Children | Terry Melcher |

| Website | dorisday |

Doris Day (born Doris Mary Ann Kappelhoff; April 3, 1922) is an American actress, singer, and animal welfare activist. After she began her career as a big band singer in 1939, her popularity increased with her first hit recording "Sentimental Journey" (1945). After leaving Les Brown & His Band of Renown to embark on a solo career, she recorded more than 650 songs from 1947 to 1967, which made her one of the most popular and acclaimed singers of the 20th century.

Day's film career began during the latter part of the Classical Hollywood Film era with the 1948 film Romance on the High Seas, and its success sparked her twenty-year career as a motion picture actress. She starred in a series of successful films, including musicals, comedies, and dramas. She played the title role in Calamity Jane (1953), and starred in Alfred Hitchcock's The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) with James Stewart. Her most successful films were the bedroom comedies she made co-starring Rock Hudson and James Garner, such as Pillow Talk (1959) and Move Over, Darling (1963), respectively. She also co-starred in films with such leading men as Clark Gable, Cary Grant, David Niven, and Rod Taylor. After her final film in 1968, she went on to star in the CBS sitcom The Doris Day Show (1968–1973).

Day was usually one of the top ten singers between 1951 and 1966.[vague] As an actress, she became the biggest female film star in the early 1960s, and ranked sixth among the box office performers by 2012.[2][3][4] In 2011, she released her 29th studio album, My Heart, which became a UK Top 10 album featuring new material. Among her awards, Day has received the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award and a Legend Award from the Society of Singers. In 1960, she was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Actress,[5] and in 1989 was given the Cecil B. DeMille Award for lifetime achievement in motion pictures. In 2004, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush followed in 2011 by the Los Angeles Film Critics Association's Career Achievement Award. She is one of the last surviving stars of the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Early life

Doris Mary Ann Kappelhoff was born on April 3, 1922, in Cincinnati, Ohio,[6] the daughter of Alma Sophia (née Welz; 1895–1976), a housewife, and William Joseph Kappelhoff (1892–1967), a music teacher and choir master.[7][8] All of her grandparents were German immigrants.[9] For most of her life, Day reportedly believed she had been born in 1924 and reported her age accordingly; it was not until her 95th birthday—when the Associated Press found her birth certificate, showing a 1922 date of birth—that she learned otherwise.[6]

The youngest of three siblings, she had two older brothers: Richard (who died before her birth) and Paul, two to three years older.[10] Due to her father's alleged infidelity, her parents separated.[4][11] She developed an early interest in dance, and in the mid-1930s formed a dance duo with Jerry Doherty that performed locally in Cincinnati.[12] A car accident on October 13, 1937, injured her right leg and curtailed her prospects as a professional dancer.[13][14]

Career

Early career (1938–1947)

While recovering from an auto accident, Day started to sing along with the radio and discovered a talent she did not know she had. Day said: "During this long, boring period, I used to while away a lot of time listening to the radio, sometimes singing along with the likes of Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Tommy Dorsey, and Glenn Miller [...]. But the one radio voice I listened to above others belonged to Ella Fitzgerald. There was a quality to her voice that fascinated me, and I'd sing along with her, trying to catch the subtle ways she shaded her voice, the casual yet clean way she sang the words."[15]

Observing her daughter sing rekindled Alma's interest in show business, and she decided Doris should have singing lessons. She engaged a teacher, Grace Raine.[16] After three lessons, Raine told Alma that young Doris had "tremendous potential"; Raine was so impressed that she gave Doris three lessons a week for the price of one. Years later, Day said that Raine had the biggest effect on her singing style and career.[15]

During the eight months she was taking singing lessons, Day had her first professional jobs as a vocalist, on the WLW radio program Carlin's Carnival, and in a local restaurant, Charlie Yee's Shanghai Inn.[17] During her radio performances, Day first caught the attention of Barney Rapp, who was looking for a girl vocalist and asked if Day would like to audition for the job. According to Rapp, he had auditioned about 200 singers when Day got the job.[18]

While working for Rapp in 1939, she adopted the stage surname "Day", at Rapp's suggestion.[19] Rapp felt that "Kappelhoff" was too long for marquees, and he admired her rendition of the song "Day After Day".[20] After working with Rapp, Day worked with bandleaders Jimmy James,[21] Bob Crosby,[22] and Les Brown.[23]

While working with Brown, Day scored her first hit recording, "Sentimental Journey", released in early 1945. It soon became an anthem of the desire of World War II demobilizing troops to return home.[24][25] This song is still associated with Day, and she rerecorded it on several occasions, including a version in her 1971 television special.[26] During 1945–46, Day (as vocalist with the Les Brown Band) had six other top ten hits on the Billboard chart: "My Dreams Are Getting Better All the Time", "'Tain't Me", "Till The End of Time", "You Won't Be Satisfied (Until You Break My Heart)", "The Whole World is Singing My Song", and "I Got the Sun in the Mornin'".[27] In the 1950s she became the most popular and one of the highest paid singers in America.[28]

Early film career (1948–1954)

While singing with the Les Brown band and for nearly two years on Bob Hope's weekly radio program,[14] she toured extensively across the United States. Her popularity as a radio performer and vocalist, which included a second hit record "My Dreams Are Getting Better All the Time", led directly to a career in films. In 1941, Day appeared as a singer in three Soundies with the Les Brown band.[29]

Her performance of the song "Embraceable You" impressed songwriter Jule Styne and his partner, Sammy Cahn, and they recommended her for a role in Romance on the High Seas (1948). Day got the part after auditioning for director Michael Curtiz.[30][31] She was shocked at being offered the role in that film, and admitted to Curtiz that she was a singer without acting experience. But he said he liked that "she was honest," not afraid to admit it, and he wanted someone who "looked like the All-American Girl," which he felt she did. She was the discovery he was most proud of during his career.[32]

The film provided her with a #2 hit recording as a soloist, "It's Magic", which followed by two months her first #1 hit ("Love Somebody" in 1948) recorded as a duet with Buddy Clark.[33] Day recorded "Someone Like You", before the 1949 film My Dream Is Yours, which featured the song.[34]

In 1950, U.S. servicemen in Korea voted her their favorite star. She continued to make minor and frequently nostalgic period musicals such as On Moonlight Bay, By the Light of the Silvery Moon, and Tea For Two for Warner Brothers.[citation needed]

Her most commercially successful film for Warner was I'll See You in My Dreams (1951), which broke box-office records of 20 years. The film is a musical biography of lyricist Gus Kahn. It was Day's fourth film directed by Curtiz.[citation needed]

In 1953, Day appeared as the title character in the comedic western-themed musical, Calamity Jane.[35] A song from the film, "Secret Love", won the Academy Award for Best Original Song and became Day's fourth No. 1 hit single in the US.[36]

Between 1950 and 1953, the albums from six of her movie musicals charted in the Top 10, three of them at No. 1. After filming Lucky Me with Bob Cummings and Young at Heart (both 1954) with Frank Sinatra, Day chose not to renew her contract with Warner Brothers.[37]

During this period, Day also had her own radio program, The Doris Day Show. It was broadcast on CBS in 1952–1953.[38]

Breakthrough (1955–1958)

Having become primarily recognized as a musical-comedy actress, Day gradually took on more dramatic roles to broaden her range. Her dramatic star-turn as singer Ruth Etting in Love Me or Leave Me (1955), co-starring James Cagney, received critical and commercial success, becoming Day's biggest hit thus far.[39] Day said it was her best film performance. Producer Joe Pasternak said, "I was stunned that Doris did not get an Oscar nomination."[40] The soundtrack album from that movie was a No. 1 hit.[41][42]

Day starred in Alfred Hitchcock's suspense film, The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) with James Stewart. She sang two songs in the film, "Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be, Will Be)", which won an Academy Award for Best Original Song,[43] and "We'll Love Again". The film was Day's 10th movie to be in the Top 10 at the box office. In 1956, Day played the title role in the thriller/noir Julie with Louis Jourdan.[44]

After three successive dramatic films, Day returned to her musical/comedic roots in 1957's The Pajama Game with John Raitt. The film was based on the Broadway play of the same name.[45] She worked with Paramount Pictures for the comedy Teacher's Pet (1958), alongside Clark Gable and Gig Young.[46] She co-starred with Richard Widmark and Gig Young in the romantic comedy film, The Tunnel of Love (1958),[47] but found scant success opposite Jack Lemmon in It Happened to Jane (1959).

Billboard's annual nationwide poll of disc jockeys had ranked Day as the No. 1 female vocalist nine times in ten years (1949 through 1958), but her success and popularity as a singer was now being overshadowed by her box-office appeal.[48]

Box-office success (1959–1968)

In 1959, Day entered her most successful phase as a film actress with a series of romantic comedies.[49][50] This success began with Pillow Talk (1959), co-starring Rock Hudson, who became a lifelong friend, and Tony Randall. Day received a nomination for an Academy Award for Best Actress.[51] Day, Hudson, and Randall made two more films together, Lover Come Back (1961) and Send Me No Flowers (1964).[52]

In 1960, she starred with David Niven and Janis Paige in the hit Please Don't Eat the Daisies. In 1962, Day appeared with Cary Grant in the comedy That Touch of Mink, the first film in history ever to gross $1 million in one theatre (Radio City Music Hall). During 1960 and the 1962 to 1964 period, she ranked number one at the box office, the second woman to be number one four times. She set a record that has yet to be equaled, receiving seven consecutive Laurel Awards as the top female box office star.[53]

Day teamed up with James Garner, starting with The Thrill of It All, followed by Move Over, Darling (both 1963).[54] The film's theme song, "Move Over Darling", co-written by her son, reached #8 in the UK.[55] In between these comedic roles, Day co-starred with Rex Harrison in the movie thriller Midnight Lace (1960), an updating of the classic stage thriller, Gaslight.[56]

By the late 1960s, the sexual revolution of the baby boomer generation had refocused public attitudes about sex. Times changed, but Day's films did not. Day's next film, Do Not Disturb (1965), was popular with audiences, but her popularity soon waned. Critics and comics dubbed Day "The World's Oldest Virgin",[57][58] and audiences began to shy away from her films. As a result, she slipped from the list of top box-office stars, last appearing in the top ten in 1966 with the hit film The Glass Bottom Boat. One of the roles she turned down was that of "Mrs. Robinson" in The Graduate, a role that eventually went to Anne Bancroft.[59] In her published memoirs, Day said she had rejected the part on moral grounds: she found the script "vulgar and offensive".[60]

She starred in the western film The Ballad of Josie (1967). That same year, Day recorded The Love Album, although it was not released until 1994.[61] The following year (1968), she starred in the comedy film Where Were You When the Lights Went Out? which centers on the Northeast blackout of November 9, 1965. Her final feature, the comedy With Six You Get Eggroll, was released in 1968.[62]

From 1959 to 1970, Day received nine Laurel Award nominations (and won four times) for best female performance in eight comedies and one drama. From 1959 through 1969, she received six Golden Globe nominations for best female performance in three comedies, one drama (Midnight Lace), one musical (Jumbo), and her television series.[63]

Bankruptcy and television career

When her third husband Martin Melcher died on April 20, 1968, a shocked Day discovered that Melcher and his business partner Jerome Bernard Rosenthal had squandered her earnings, leaving her deeply in debt.[64] Rosenthal had been her attorney since 1949, when he represented her in her uncontested divorce action against her second husband, saxophonist George W. Weidler. Day filed suit against Rosenthal in February 1969, won a successful decision in 1974, but did not receive compensation until a settlement in 1979.[65]

Day also learned to her displeasure that Melcher had committed her to a television series, which became The Doris Day Show.

"It was awful", Day told OK! Magazine in 1996. "I was really, really not very well when Marty [Melcher] passed away, and the thought of going into TV was overpowering. But he'd signed me up for a series. And then my son Terry [Melcher] took me walking in Beverly Hills and explained that it wasn't nearly the end of it. I had also been signed up for a bunch of TV specials, all without anyone ever asking me."

Day hated the idea of performing on television, but felt obligated to do it.[62] The first episode of The Doris Day Show aired on September 24, 1968,[66] and, from 1968 to 1973, employed "Que Sera, Sera" as its theme song. Day persevered (she needed the work to help pay off her debts), but only after CBS ceded creative control to her and her son. The successful show enjoyed a five-year run,[67] and functioned as a curtain raiser for the popular Carol Burnett Show. It is remembered today for its abrupt season-to-season changes in casting and premise.[68]

(CBS, February 19, 1975)[69]

By the end of its run in 1973, public tastes had changed and her firmly established persona was regarded as passé. She largely retired from acting after The Doris Day Show, but did complete two television specials, The Doris Mary Anne Kappelhoff Special (1971)[70] and Doris Day Today (1975).[71] She appeared on the John Denver TV show in 1974.[61][72]

In the 1985–86 season, Day hosted her own television talk show, Doris Day's Best Friends, on CBN.[67][73] The network canceled the show after 26 episodes, despite the worldwide publicity it received. Much of that came from her interview with Rock Hudson, in which a visibly ill Hudson was showing the first public symptoms of AIDS; Hudson would die from the syndrome a year later.[74]

1980s and 1990s

In October 1985, the California Supreme Court rejected Rosenthal's appeal of the multimillion-dollar judgment against him for legal malpractice, and upheld conclusions of a trial court and a Court of Appeal that Rosenthal acted improperly. In April 1986, the U.S. Supreme Court refused to review the lower court's judgment. In June 1987, Rosenthal filed a $30 million lawsuit against lawyers he claimed cheated him out of millions of dollars in real estate investments. He named Day as a co-defendant, describing her as an "unwilling, involuntary plaintiff whose consent cannot be obtained". Rosenthal claimed that millions of dollars Day lost were in real estate sold after Melcher died in 1968, in which Rosenthal asserted that the attorneys gave Day bad advice, telling her to sell, at a loss, three hotels, in Palo Alto, California, Dallas, Texas, and Atlanta, Georgia, plus some oil leases in Kentucky and Ohio.

Rosenthal claimed he had made the investments under a long-term plan, and did not intend to sell them until they appreciated in value. Two of the hotels sold in 1970 for about $7 million, and their estimated worth in 1986 was $50 million. In July 1984, after a hearing panel of the State Bar Court, after 80 days of testimony and consideration of documentary evidence, the panel accused Rosenthal of 13 separate acts of misconduct and urged his disbarment in a 34-page unsigned opinion.[75] The State Bar Court's review department upheld the panel's findings, which asked the justices to order Rosenthal's disbarment. He continued representing clients in federal courts until the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against him on March 21, 1988. Disbarment by the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals followed on August 19, 1988. The Supreme Court of California, in affirming the disbarment, held that Rosenthal had engaged in transactions involving undisclosed conflicts of interest, took positions adverse to his former clients, overstated expenses, double-billed for legal fees, failed to return client files, failed to provide access to records, failed to give adequate legal advice, failed to provide clients with an opportunity to obtain independent counsel, filed fraudulent claims, gave false testimony, engaged in conduct designed to harass his clients, delayed court proceedings, obstructed justice and abused legal process. Rosenthal died August 15, 2007, at the age of 96.[76]

Terry Melcher stated that his adoptive father's premature death saved Day from financial ruin. It remains unresolved whether Martin Melcher had himself also been duped.[77] Day stated publicly that she believed her husband innocent of any deliberate wrongdoing, stating that he "simply trusted the wrong person".[78] According to Day's autobiography, as told to A.E. Hotchner, the usually athletic and healthy Martin Melcher had an enlarged heart. Most of the interviews on the subject given to Hotchner (and included in Day's autobiography) paint an unflattering portrait of Melcher. Author David Kaufman asserts that one of Day's costars, actor Louis Jourdan, maintained that Day herself disliked her husband,[79] but Day's public statements regarding Melcher appear to contradict that assertion.[80]

Day was scheduled to present, along with Patrick Swayze and Marvin Hamlisch, the Best Original Score Oscar at the 61st Academy Awards in March 1989 but she suffered a deep leg cut and was unable to attend.[81] She had been walking through the gardens of her hotel when she cut her leg on a sprinkler. The cut required stitches.[82]

Day was inducted into the Ohio Women's Hall of Fame in 1981 and received the Cecil B. DeMille Award for career achievement in 1989.[83] In 1994, Day's Greatest Hits album became another entry into the British charts.[61] The song "Perhaps, Perhaps, Perhaps" was included in the soundtrack of the Australian film Strictly Ballroom[84] and was the theme song for the British TV show Coupling, with Mari Wilson performing the song for the title sequence.[85]

2000s

Day has participated in interviews and celebrations of her birthday with an annual Doris Day music marathon.[86] In July 2008, she appeared on the Southern California radio show of longtime friend, newscaster George Putnam.[87]

Day turned down a tribute offer from the American Film Institute and from the Kennedy Center Honors because they require attendance in person. In 2004, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President George W. Bush for her achievements in the entertainment industry and for her work on behalf of animals.[88] President Bush stated:

In the years since, she has kept her fans and shown the breadth of her talent in television and the movies. She starred on screen with leading men from Jimmy Stewart to Ronald Reagan, from Rock Hudson to James Garner. It was a good day for America when Doris Mary Ann von Kappelhoff of Evanston, Ohio decided to become an entertainer. It was a good day for our fellow creatures when she gave her good heart to the cause of animal welfare. Doris Day is one of the greats, and America will always love its sweetheart.[88]

Columnist Liz Smith and film critic Rex Reed mounted vigorous campaigns to gather support for an Honorary Academy Award for Day to herald her film career and her status as the top female box-office star of all time.[89] Day received a Grammy for Lifetime Achievement in Music in 2008, albeit again in absentia.[90]

She received three Grammy Hall of Fame Awards, in 1998, 1999 and 2012 for her recordings of "Sentimental Journey", "Secret Love", and "Que Sera, Sera", respectively.[91] Day was inducted into the Hit Parade Hall of Fame in 2007,[92] and in 2010 received the first Legend Award ever presented by the Society of Singers.[61]

2010s

Day, aged 89, released My Heart in the United Kingdom on September 5, 2011, her first new album in nearly two decades, since the release of The Love Album, which, although recorded in 1967, was not released until 1994.[93] The album is a compilation of previously unreleased recordings produced by Day's son, Terry Melcher, before his death in 2004. Tracks include the 1970s Joe Cocker hit "You Are So Beautiful", The Beach Boys' "Disney Girls" and jazz standards such as "My Buddy", which Day originally sang in her 1951 film I'll See You in My Dreams.[94][95]

After the disc was released in the US it soon climbed to No. 12 on Amazon's bestseller list, and helped raise funds for the Doris Day Animal League.[96] Day became the oldest artist to score a UK Top 10 with an album featuring new material.[97]

In January 2012, the Los Angeles Film Critics Association presented Day with a Lifetime Achievement Award.[98][99]

In April 2014, Day made an unexpected public appearance to attend the annual Doris Day Animal Foundation benefit. The benefit raises money for her Animal Foundation.[100]

Clint Eastwood offered Day a role in a film he was planning to direct in 2015.[101] Although she reportedly was in talks with Eastwood, her neighbour in Carmel, about a role in the film, she eventually declined.[102]

Day granted an ABC telephone interview on her birthday in 2016, which was accompanied by photos of her life and career.[103]

In a rare interview with The Hollywood Reporter on April 4, 2019, a day after her 97th birthday, Day talked about her work on The Doris Day Animal Foundation, founded in 1978. On the question of what her favorite film was, she answered Calamity Jane: "I was such a tomboy growing up, and she was such a fun character to play. Of course, the music was wonderful, too — 'Secret Love,' especially, is such a beautiful song."[104] To commemorate her birthday, her fans gather each year to take part in a three-day party in her hometown of Carmel, California, in late March. The event is also a fundraiser for her Animal Foundation. In 2019, during the event, there was a special screening of her 1959 film Pillow Talk to celebrate its 60th anniversary. About the film Day stated in the same interview that she "had such fun working with my pal, Rock. We laughed our way through three films we made together and remained great friends. I miss him."[104]

Personal life

Since her retirement from films, Day has lived in Carmel-by-the-Sea, California. She has many pets and adopts stray animals.[105]

Day is a lifelong Republican,[106] and supported George W. Bush's presidential campaign in 2000.[citation needed] Her only child, music producer and songwriter Terry Melcher, who had a hit in the 1960s with "Hey Little Cobra" under the name The Rip Chords, died of melanoma in November 2004.[107] Day owns a hotel in Carmel-by-the-Sea, the Cypress Inn, which she co-owned with her son.[108]

Marriages

Day has been married four times.[109] She was married to Al Jorden, a trombonist whom she first met in Barney Rapp's Band, from March 1941 to February 1943.[110] Her only child, son Terrence Paul Jorden (later known as Terry Melcher), resulted from this marriage; he died in 2004. Her second marriage was to George William Weidler, a saxophonist and the brother of actress Virginia Weidler, from March 30, 1946, to May 31, 1949.[110] Weidler and Day met again several years later; during a brief reconciliation, he helped introduce her to Christian Science.

On April 3, 1951, her 29th birthday, she married Martin Melcher. This marriage lasted until Melcher's death in April 1968.[110] Melcher adopted Day's son Terry, who, with the name Terry Melcher, became a successful musician and record producer.[111] Martin Melcher produced many of Day's movies. She and Melcher were both practicing Christian Scientists, resulting in her not seeing a doctor for some time after symptoms that suggested cancer. This distressing period ended when, finally consulting a physician, and thereby finding the lump was benign, she fully recovered.

Day's fourth marriage, from April 14, 1976, until April 2, 1982, was to Barry Comden (1935–2009).[112] Comden was the maître d'hôtel at one of Day's favorite restaurants. Knowing of her great love of dogs, Comden endeared himself to Day by giving her a bag of meat scraps and bones on her way out of the restaurant. When this marriage unraveled, Comden complained that Day cared more for her "animal friends" than she did for him.[112]

Animal welfare activism

Day's interest in animal welfare and related issues apparently dates to her teen years. While recovering from an automobile accident, she took her dog Tiny for a walk without a leash. Tiny ran into the street and was killed by a passing car. Day later expressed guilt and loneliness about Tiny's untimely death. In 1971, she co-founded Actors and Others for Animals, and appeared in a series of newspaper advertisements denouncing the wearing of fur, alongside Mary Tyler Moore, Angie Dickinson, and Jayne Meadows.[113] Day's friend, Cleveland Amory, wrote about these events in Man Kind? Our Incredible War on Wildlife (1974).

In 1978, Day founded the Doris Day Pet Foundation, now the Doris Day Animal Foundation (DDAF).[114] A non-profit 501(c)(3) grant-giving public charity, DDAF funds other non-profit causes throughout the US that share DDAF's mission of helping animals and the people who love them. The DDAF continues to operate independently under Day's personal supervision.[115]

To complement the Doris Day Animal Foundation, Day formed the Doris Day Animal League (DDAL) in 1987, a national non-profit citizen's lobbying organization whose mission is to reduce pain and suffering and protect animals through legislative initiatives.[116] Day actively lobbied the United States Congress in support of legislation designed to safeguard animal welfare on a number of occasions and in 1995 she originated the annual Spay Day USA.[117] The DDAL merged into The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) in 2006.[118] The HSUS now manages World Spay Day, the annual one-day spay/neuter event that Day originated.[119]

A facility to help abused and neglected horses opened in 2011 and bears her name—the Doris Day Horse Rescue and Adoption Center, located in Murchison, Texas, on the grounds of an animal sanctuary started by her late friend, author Cleveland Amory.[120] Day contributed $250,000 towards the founding of the center.[121]

Day is a vegetarian.[122]

Discography

Studio albums

- You're My Thrill (1949)

- Day Dreams (1955)

- Day by Day (1956)

- Day by Night (1957)

- Hooray for Hollywood (1958)

- Cuttin' Capers (1959)

- What Every Girl Should Know (1960)

- Show Time (1960)

- Listen to Day (1960)

- Bright and Shiny (1961)

- I Have Dreamed (1961)

- Duet (w/ André Previn) (1962)

- You'll Never Walk Alone (1962)

- Love Him (1963)

- The Doris Day Christmas Album (1964)

- With a Smile and a Song (1964)

- Latin for Lovers (1965)

- Doris Day's Sentimental Journey (1965)

- The Love Album (recorded 1967, released in 1994)

- My Heart (2011)

Filmography

Awards and nominations

References

- ^ "About Doris – Doris Day". Dorisday.com. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ^ "Top Ten Money Making Stars". Quigley Publishing Company. QP Media, Inc. Archived from the original on January 14, 2013. Retrieved December 19, 2013.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Doris Day". Biography in Context. Detroit, MI: Gale. 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Hotchner, A.E. (1976). Doris Day: Her Own Story. New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc. ISBN 978-0-688-02968-5.

- ^ Doris Day awards and nominations, Dorisday.com

- ^ a b Elber, Lynn (April 2, 2017). "Birthday surprise for ageless Doris Day: She's actually 95". Associated Press. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

A copy of Day's birth certificate, obtained by The Associated Press from Ohio's Office of Vital Statistics, settles the issue: Doris Mary Kappelhoff, her pre-fame name, was born on April 3, 1922, making her 96. Her parents were Alma and William Kappelhoff of Cincinnati.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Kaufman 2008, p. 4. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKaufman2008 (help)

- ^ "Ancestry.com".

Born 1922: age on April 10, 1940, in Hamilton County, Ohio, 91–346 (enumeration district), 2552 Warsaw Avenue, was 18 years old as per 1940 United States Census records; name transcribed incorrectly as "Daris Kappelhoff", included with mother Alma and brother Paul, all with same surname

. (registration required; initial 14-day free pass) - ^ "Doris Day profile" (ancestry). Wargs. Retrieved April 5, 2014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Hotchner 1975, p. 18.

- ^ Amory, Cleveland (August 3, 1986). "Doris Day talks about Rock Hudson, Ronald Reagan and her own story". The Pittsburgh Press. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Parish, James Robert; Pitts, Michael R. (January 1, 2003). Hollywood songsters. 1. Allyson to Funicello. Routledge. p. 235. ISBN 978-0-415-94332-1. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Trenton Friends Regret Injury to Girl Dancer". Hamilton Daily News Journal. October 18, 1937. p. 7. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Browne, Ray Broadus; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. pp. 220–221. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Hotchner 1975, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Hotchner 1975, p. 38.

- ^ Hotchner 1975, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Hotchner 1975, p. 44.

- ^ "Doris Day's sweet success". BBC News. April 3, 2004. Retrieved August 10, 2013.

- ^ Kaufman 2008, p. 22. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKaufman2008 (help)

- ^ "To Entertain at Convention Here". The Lima News. April 17, 1940. p. 11. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Sutro, Dirk (2011). Jazz For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-118-06852-6. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ The Guinan Family (October 2009). Lakewood Park. Arcadia Publishing. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7385-6578-1. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Gilliland, John (1994). Pop Chronicles the 40s: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40s (audiobook). ISBN 978-1-55935-147-8. OCLC 31611854. Tape 1, side B.

- ^ Santopietro, Tom (2008). Considering Doris Day. St. Martin's Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4299-3751-1. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Braun 2004, p. 26: "It is not surprising... that she took so readily to Christian Science in her later life"

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1986). Joel Whitburn's Pop Memories 1890–1954. Wisconsin: Record Research Inc. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-89820-083-6.

- ^ Doris Day biography, All Music

- ^ Terenzio, Maurice; MacGillivray, Scott; Okuda, Ted (1991). The Soundies Distributing Corporation of America: a history and filmography of their "jukebox" musical films of the 1940s. McFarland & Co. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-0-89950-578-7. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Hotchner 1975, p. 91.

- ^ Gentry, Philip Max (2008). The Age of Anxiety: Music, Politics, and McCarthyism, 1948–1954. ProQuest. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-549-90073-3. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Michael Curtiz Services Set". The Tennessean. Associated Press. April 12, 1962. p. 58. Retrieved April 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1986). Joel Whitburn's Pop Memories 1890–1954. Wisconsin: Record Research Inc. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-89820-083-6.

- ^ "Billboard". Books.google.com. January 15, 1949. p. 35. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ^ "Doris Day Learned How to Flick Bull Whip for Tough Western Role in 'Calamity Jane'". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. November 8, 1953. p. 31. Retrieved June 26, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Tyler, Don (2008). Music of the Postwar Era. ABC-CLIO. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-313-34191-5. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Palmer, R. Barton (2010). Larger Than Life: Movie Stars of the 1950s. Rutgers University Press. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-8135-4994-1. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Dunning, John (1998). On the Air: The Encyclopedia of Old-Time Radio (Revised ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-19-507678-3.

- ^ Lisanti, Tom; Paul, Louis (2002). Film Fatales: Women in Espionage Films and Television, 1962–1973. McFarland. p. 104. ISBN 978-0-7864-1194-8. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Bawden, Jim. "His long career making top films also made many stars". TheColumnists.com. Archived from the original on January 1, 2012. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "Best Selling Popular Albums". Billboard: 94. November 12, 1955. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Love Me Or Leave Me – Trailer, Warner Movies

- ^ Tyler, Don (2008). Music of the Postwar Era. ABC-CLIO. pp. 113–14. ISBN 978-0-313-34191-5. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Doris Day Due Tonight for Premiere". The Cincinnati Enquirer. October 7, 1956. Retrieved June 26, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stratton, David (November 19, 2014). "The Pajama Game: The Classic". At the Movies. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ W., A. (March 20, 1958). "'Teacher's Pet,' Story of Fourth Estate, Opens at Capitol". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (November 22, 1958). "'Tunnel of Love'; Widmark, Doris Day Star in Roxy Film". The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "The Films of Doris Day: recordings". Dorisday.net.

- ^ Gourley, Catherine (2008). Gidgets and Women Warriors: Perceptions of Women in the 1950s and 1960s. Twenty-First Century Books. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8225-6805-6. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Monteith, Sharon (2008). American Culture in the 1960s. Edinburgh University Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0-7486-1947-4. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Finler, Joel Waldo (2003). The Hollywood Story. Wallflower Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-1-903364-66-6. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Glitre, Kathrina (2006). Hollywood Romantic Comedy: States of the Union, 1934–1965. Manchester University Press. p. 159. ISBN 978-0-7190-7079-2. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Morris, George (1976). Doris Day. Pyramid Publications. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-515-03959-7. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Harding, Les (2012). They Knew Marilyn Monroe: Famous Persons in the Life of the Hollywood Icon. McFarland. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-7864-9014-1. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Pilchak, Angela (2005). Contemporary Musicians: Profiles of the People in Music. Gale. p. 133. ISBN 9780787680664. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Waller, Gregory Albert (1987). American Horrors: Essays on the Modern American Horror Film. University of Illinois Press. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-252-01448-2. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "The American Film Institute Catalog of Motion Pictures". Doris Day (Filmography).

- ^ McCormick, Neil (August 20, 2011). "Doris Day: sexy side of the girl next door". The Telegraph. London. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Grindon, Leger (2011). The Hollywood Romantic Comedy: Conventions, History and Controversies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-4443-9595-2. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Kashner, Sam (March 2008). "Here's to You, Mr. Nichols: The Making of The Graduate". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ a b c d "About" (Official website). Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ a b Landazuri, Margarita. "With Six You Get Eggroll". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Doris Day". Golden Globes. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ Sonneborn, Liz (2002). A to Z of American Women in the Performing Arts. Infobase Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-4381-0790-5. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Grace, Roger M. "'Uncle Jerry' Faces the Music in Court, in State Bar Proceeding". Metropolitan News-Enterprise. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Doris Day Heads Own Show". Hawkins County Post. September 12, 1968. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ a b "ABC snares Doris Day for TV movies". Spokane Chronicle. October 3, 1990. Retrieved January 26, 2016.

- ^ McGee 2005, pp. 227–28.

- ^ Doris Day Today (TV special, February 19, 1975) at IMDb

- ^ "The Doris Mary Anne Kappelhoff Special". IMDb.com. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ "Doris Day Today". IMDb.com. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ "The John Denver Show". IMDb.com. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

- ^ Oberman, Tracy-Ann (October 16, 2012). "Rock and Doris and Elizabeth: a moment that changed Hollywood". The Guardian. London. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ^ Martin, James A. (July 11, 1997). "Hudson's Day of Revelation". ew.com. Retrieved December 25, 2012.

- ^ Hager, Philip (July 14, 1987). "Doris Day's Former Lawyer Disbarred". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Grace, Roger M. (October 1, 2007). "'Uncle Jerry' – Jerome B. Rosenthal – Is Dead". Metropolitan News-Enterprise. Retrieved August 19, 2012.

- ^ Champlin, Charles (March 13, 1988). "Doris Day: Singing and Looking for Pet Projects". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ^ Doris Day: A Sentimental Journey (Television Documentary), Arwin Productions, PBS, 1991

- ^ Kaufman, David (May 2008). "Doris Day's Vanishing Act". Vanity Fair. Condé Nast. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

Both Doris and I hated the director [Andrew L. Stone]. I also disliked her husband, and I was surprised to discover she did, too.

- ^ Hotchner 1975, p. 226.

- ^ "Cut keeps Doris Day from Academy Awards". The Republic. Associated Press. March 30, 1989. p. A2. Retrieved April 4, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ MacMinn, Aileen (March 31, 1989). "Post Oscar". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ video: "Doris Day Receives the Cecil B. Demille Award – Golden Globes 1989", Dick Clark Productions

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Strictly Ballroom [CBS] – Original Soundtrack". AllMusic. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Green, Thomas H. (March 25, 2013). "Mari Wilson, The Komedia, Brighton". The Arts Desk. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "A preview of the Doris Day Movie Marathon happening April 3", WVXU, March 28, 2014

- ^ Mclellan, Dennis (September 13, 2008). "George Putnam, longtime L.A. newsman, dies at 94". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "President Bush Presents the Presidential Medal of Freedom". The White House. White House Office of the Press Secretary. June 23, 2004. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ Smith, Liz (November 27, 2011). "Let's Give Doris Day An Award". ThirdAge. Archived from the original on November 12, 2013. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

When, oh when, will Doris receive her long-overdue honorary Academy Award?

- ^ "Lifetime Achievement Award". grammy.org. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ^ "GRAMMY Hall of Fame". Grammy.org. The Recording Academy. Retrieved April 3, 2017.

- ^ "Inductees". Hit Parade Hall of Fame. Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- ^ Cody, Antony (September 1, 2011). "Doris Day releases first album in 17 years". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Elber, Lynn (November 29, 2011). "Doris Day sings out for 1st time in 17 years". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Associated Press. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ Cooper, Leonie (August 15, 2011). "87 year-old Doris Day to release new album". NME. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ "Weekly Chart Notes: Doris Day, Gloria Estefan, Selena Gomez – Chart Beat". Billboard. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "Doris Day makes UK chart history". BBC News. September 11, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2012.

- ^ "Doris Day Wins Lifetime Achievement Award from L.A. Film Critics". The wrap. October 29, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (October 29, 2011). "Doris Day to Receive Career Achievement Award From Los Angeles Film Critics Association". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 4, 2017.

- ^ McNeil, Liz (April 9, 2014). "Doris Day Makes Her First Public Appearance in More Than 2 Decades". People. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ Lee, Benjamin (September 22, 2015). "Doris Day reportedly lured out of retirement by Clint Eastwood". The Guardian. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ "Doris Day: not quite the girl next door". Irish Independent. April 3, 2016. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ "Doris Day Shares Never-Before-Seen Photo for 92nd Birthday". ABC News. April 5, 2016. Retrieved May 18, 2017.

- ^ a b Laurie Brookins, “Doris Day, in Rare Interview, Talks Turning 97, Her Animal Foundation and Rock Hudson: ‘I Miss Him’”, The Hollywood Reporter. April 3, 2019. (Retrieved 2019-04-10.)

- ^ "Doris Day: A Hollywood Legend Reflects On Life". NPR. January 2, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Kaufman 2008, p. 437. sfn error: multiple targets (2×): CITEREFKaufman2008 (help)

- ^ Cartwright, Garth (November 23, 2004). "Terry Melcher". The Guardian. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ^ Anderson, Marilyn; Lanning, Dennis L. (September 11, 2011). "The Cypress Inn: Doris Day's Pet-Friendly Getaway in Carmel-by-the-Sea". Agenda mag. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ "Doris Day: Why she left Hollywood". CBS News. July 14, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ a b c "Doris Day Fast Facts". CNN. March 20, 2018. Retrieved June 26, 2018.

- ^ "Producer Terry Melcher Dies at 62". Billboard. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Nelson, Valerie J. (June 2, 2009). "Barry Comden dies at 74; restaurateur was 4th husband of Doris Day". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Patrick & McGee 2006, p. 132, photograph of ad.

- ^ Grudens, Richard (2001). Sally Bennett's Magic Moments. Celebrity Profiles Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-57579-181-4. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "About DDAF". Doris Day Animal Foundation. Retrieved July 30, 2013.

- ^ Chicken Soup for the Pet Lover's Soul: Stories about Pets as Teachers, Healers, Heroes, and Friends. HCI Books. 1998. p. 385. ISBN 978-1-55874-571-1. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ "Join 'Spay Day USA' campaign". Gainesville Sun. January 31, 1995. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Sarasohn, Judy (September 7, 2006). "Merger Adds to Humane Society's Bite". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 5, 2007.

- ^ "World Spay Day". The Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved January 15, 2016.

- ^ Patrick-Goudreau, Colleen (2011). Vegan's Daily Companion: 365 Days of Inspiration for Cooking, Eating, and Living Compassionately. Quarry Books. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-61058-015-1. Retrieved August 8, 2013.

- ^ Di Paola, Mike (March 30, 2011). "Doris Day Center Gives Abused Horses Sanctuary with Elands, Emu". bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Doris Day, 93 from 12 Celebrities Age 90 or More and What They Love to Eat Slideshow". The Daily Meal. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

Bibliography

- Barothy, Mary Anne (2007), Day at a Time: An Indiana Girl's Sentimental Journey to Doris Day's Hollywood and Beyond. Hawthorne Publishing

- Braun, Eric (2004), Doris Day (2 ed.), London: Orion Books, ISBN 978-0-7528-1715-6

- Bret, David (2008), Doris Day: Reluctant Star. JR Books, London

- Brogan, Paul E. (2011), Was That a Name I Dropped?, Aberdeen Bay; ISBN 1608300501, 978-1608300501

- DeVita, Michael J. (2012). My 'Secret Love' Affair with Doris Day (Paperback). CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform. ISBN 978-1478153580.

- Hotchner, AE (1975), Doris Day: Her Own Story, William Morrow & Co, ISBN 978-0-688-02968-5.

- Kaufman, David (2008), Doris Day: The Untold Story of the Girl Next Door, New York: Virgin Books, ISBN 978-1-905264-30-8

- McGee, Garry (2005), Doris Day: Sentimental Journey, McFarland & Co

- Patrick, Pierre; McGee, Garry (2006), Que Sera, Sera: The Magic of Doris Day Through Television, Bear Manor

- Patrick, Pierre; McGee, Garry (2009), The Doris Day Companion: A Beautiful Day (One on One with Doris and Friends). BearManor Media

- Santopietro, Thomas "Tom" (2007), Considering Doris Day, New York: Thomas Dunn Books, ISBN 978-0-312-36263-8

External links

- Official website

- Doris Day Animal Foundation

- Doris Day at IMDb

- Doris Day at AllMovie

- Doris Day at the TCM Movie Database

- Spotlight at Turner Classic Movies

- Christmas message from Doris Day – The Oklahoman, accessed March, 2019.

- Doris Day

- 1922 births

- Living people

- 20th-century American actresses

- 20th-century American singers

- 21st-century American singers

- 20th-century women singers

- 21st-century women singers

- Actresses from Cincinnati

- Actresses of German descent

- American film actresses

- American memoirists

- American female pop singers

- American television actresses

- American television talk show hosts

- Big band singers

- Cecil B. DeMille Award Golden Globe winners

- Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award winners

- Age controversies

- American Christian Scientists

- Animal welfare workers

- American people of German descent

- Musicians from Cincinnati

- Columbia Records artists

- California Republicans

- People from Carmel-by-the-Sea, California

- Presidential Medal of Freedom recipients

- Traditional pop music singers

- Warner Bros. contract players