Devanagari: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

Removing deleted image |

||

| Line 456: | Line 456: | ||

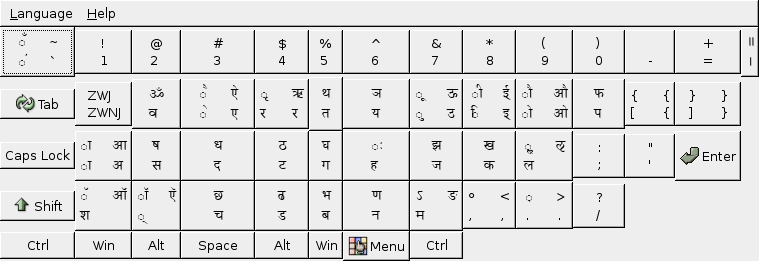

===INSCRIPT / KDE Linux === |

===INSCRIPT / KDE Linux === |

||

[[Image:Devanagari INSCRIPT2.png|800px|none|INSCRIPT Keyboard Layout (Windows, Solaris, Java)]] |

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[Image:Devanagari INSCRIPT2.png|800px|none|INSCRIPT Keyboard Layout (Windows, Solaris, Java)]] --> |

||

This is the India keyboard layout for Linux (variant 'deva') |

This is the India keyboard layout for Linux (variant 'deva') |

||

Revision as of 22:35, 26 March 2008

Template:IndicTextRight Devanāgarī (देवनागरी, Template:PronEng in English) is an abugida script. It is the main script used to write the Hindi, Marathi, and Nepali languages. Since the 19th century, it has become the most common script used to represent Sanskrit. Other languages using Devanagari (although not always as their only or principal script) include Sindhi, Bihari, Bhili, Marwari, Konkani, Bhojpuri, Pahari (Garhwali and Kumaoni), Santhali, Newari, Tharu, and Kashmiri. It is written and read from left to right.

| Devanāgarī देवनागरी | |

|---|---|

Rigveda manuscript in Devanāgarī (early 19th century) | |

| Script type | |

Time period | c. 1200–present |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| Region | India and Nepal |

| Languages | Several Indo-Aryan languages, including Sanskrit, Hindi, Marathi, Nepali, Bihari, Bhili, Konkani, Bhojpuri, Newari and sometimes Sindhi and Kashmiri |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Gujarati Moḍī Ranjana Canadian Aboriginal Syllabics |

Sister systems | Eastern Nāgarī |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Deva (315), Devanagari (Nagari) |

| Unicode | |

Unicode alias | Devanagari |

| U+0900–U+097F | |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

| Brahmic scripts |

|---|

| The Brahmi script and its descendants |

Origins

Devanāgarī emerged around CE 1200 out of the Siddham script, gradually replacing the earlier, closely related Sharada script (which remained in parallel use in Kashmir). Both are immediate descendants of the Gupta script, ultimately deriving from the Brāhmī script attested from the 3rd century BCE; Nāgarī appeared in approx. the 8th century as an eastern variant of the Gupta script, contemporary to Sharada, its western variant. The descendants of Brahmi form the Brahmic family, including the alphabets employed for many other South and South-East Asian languages.

Sanskrit nāgarī is the feminine of nāgara "urban(e)", an adjectival vrddhi derivative from nagara "city"; the feminine form is used because of its original application to qualify the feminine noun lipi "script" ("urban(e) script", i.e. the script of the cultured). There were several varieties in use, one of which was distinguished by affixing deva "deity" to form a tatpurusha compound meaning the "urban(e) [script] of the deities (= gods)", i.e. "divine urban(e) [script]".

The widespread use of the name Devanāgarī is relatively recent; well into the twentieth century, and even today, simply Nāgarī was also in use for this same script. The rapid spread of the usage of Devanāgarī seems also to be connected with the almost exclusive use of this script in colonial times to publish works in Sanskrit, even though traditionally nearly all indigenous scripts had been employed for this language. This has led to the establishment of such a close connection between the script and Sanskrit that it is, erroneously, widely regarded as "the Sanskrit script" today.

Principles

As a Brahmic abugida, the fundamental principle of the Devanagari writing system is that each base consonantal character carries within it an inherent vowel a [ə]. That is, an unmarked consonant sign is assumed to represent that consonant plus the inherent vowel;[1] e.g. क ka, कन kana, कनय kanaya, etc. Flowing from this core feature are a number of other features.

- Consonant clusters lacking intervening vowels may be represented by physically joined and condensed ligatures or "conjuncts" (saṃyuktākṣara); e.g. कनय kanaya → क्नय knaya, कन्य kanya, क्न्य knya.

- For postconsonantal vowels other than inherent a, the consonant symbol is applied with diacritics; e.g. क ka → के ke, कु ku, की kī, का kā.

- For non-postconsonantal vowels (initial and post-vocalic positions), there are full-formed characters. Thus ū is ू in कू kū but ऊ in ऊक ūka and कऊ kaū.

- The diacritic ્, called the virāma or halanta, indicates cancellation of the inherent vowel; e.g. क्नय knaya → क्नय् knay.

Thus the basic unit is the graphic symbol or akṣara, with phonetic structures V or (C)(C)(C)(C)C(V). Finally, Devanagari is written from left to right, lacks distinct cases, and possesses a horizontal line running above the characters, linking them together.

Symbols

Devanagari, like nearly all Brahmi scripts, is ordered based on phonetic principles, considering both manner and place of articulation, as per Sanskrit and its grammatical tradition (cf. Vyakarana). Indeed, Devanagari as used for Sanskrit serves as the prototype for its application, with minor variations or additions, to other languages.[2] The below two tables derive from Wikner (1996:13, 14, 73). This arrangement is usually referred to as the varṇamālā "garland of letters".[3]

Vowels

| Independent form | Romanized | As diacritic with प | Independent form | Romanized | As diacritic with प | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| kaṇṭhya (Guttural) |

अ | a | प | आ | ā | पा | |

| tālavya (Palatal) |

इ | i | पि | ई | ī | पी | |

| oṣṭhya (Labial) |

उ | u | पु | ऊ | ū | पू | |

| mūrdhanya (Cerebral) |

ऋ |

ṛ |

पृ | ॠ | ṝ | पॄ | |

| dantya (Dental) |

ऌ | ḷ | पॢ | ॡ | ḹ | पॣ | |

| kaṇṭhatālavya (Palato-Guttural) |

ए | ē | पे | ऐ | ai | पै | |

| kaṇṭhoṣṭhya (Labio-Guttural) |

ओ | ō | पो | औ | au | पौ |

- Also organized with these vowels are two non-vowel diacritics, the anusvāra

ं ṃ and the visarga

ःḥ (recited as

अंaṃ and

अः aḥ). In regard to Sanskrit, Masica (1991:146) notes of the anusvāra that "there is some controversy as to whether it represents a homorganic nasal consonant [...], a nasalized vowel, a nasalized semivowel, or all these according to context". The visarga represents post-vocalic voiceless glottal fricative [h], an allophone in Sanskrit of s, or less commonly r, usually in word-final position. Some traditions append an echo of the vowel after the breath;[4] e.g. इः [ihi]. Masica (1991:146) considers the visarga along with symbols ङ ṅa and ञ ña for the "largely predictable" velar and palatal nasals to be examples of "phonetic overkill in the system".

- Another associated symbol is the candrabindu/anunāsika

. Salomon (2003:76–77) notes it as a "more emphatic form" of the anusvāra, "sometimes [...] used to mark a true [vowel] nasalization". In a New Indo-Aryan language such as Hindi the distinction is clear and formal: the candrabindu indicates vowel nasalization[5] while the anusvār indicates a homorganic nasal consonant;[6] e.g.

हँसी[ɦə̃si] "laughter,

गंगा[gəŋgɑ] "Ganges". However, when a syllable has a vowel sign above the top line that leaves no room for the candrabindu's candra ("moon") portion, then it is dispensed with in favour of the lone dot;[7] e.g.

हूँ[ɦũ] "am", but

हैं [ɦɛ̃] "are". Finally, some writers and typesetters dispense with the "moon" altogether, using the dot alone all of the time.[8]

- The avagraha

(usually transliterated with an apostrophe) is a punctuational sign indicating the elision or coalescence of a vowel in Sanskrit as a result of sandhi; e.g.

एकोऽयमekoyam (< ekas + ayam) "this one". An original long vowel lost by coalescence is sometimes indicated by a double avagraha; e.g.

सदाऽऽत्माsadātmā (< sadā + ātmā) "always, the self".[9] In Hindi, Snell (2000:77) states that its "main function is to show that a vowel is sustained in a cry or a shout"; e.g.

आईऽऽऽ!āīīī!. In Magahi, Verma (2003:501) explains that it is used to mark the non-elision of word-final inherent a. Word-final a-elision is a modern orthographic convention/assumption, and Magahi, which has "quite a number of verbal forms [that] end in that inherent vowel", deals with it as such; e.g.

बइठऽbaiṭha "sit" versus

*बइठ baiṭh

- The vowels ṝ, ḷ, and ḹ are Sanskrit-specific and not included in the varṇamālās of other languages. With the sound represented by ṛ having been lost as well, it now elicits pronunciations ranging from [ɾɪ] (Hindi) to [ɾu] (Marathi).

- ḹ is not actually a primary phoneme of Sanskrit, but is usually included among the vowels in order to maintain the symmetry of short/long pairs.[2]

- There are non-regular formations of रु ru and रू rū.

Consonants

| sparśa (Stop) |

anunāsika (Nasal) |

antaḥstha (Semivowel) |

ūṣman (Fricative) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voicing → | aghoṣa | ghoṣa | aghoṣa | ghoṣa | ||||||||||||

| Aspiration → | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | alpaprāṇa | mahāprāṇa | ||||||||||

| kaṇṭhya (Guttural) |

क | ka | ख | kha | ग | ga | घ | gha | ङ |

ṅa |

ह |

ha | ||||

| tālavya (Palatal) |

च | ca | छ | cha | ज | ja | झ | jha | ञ | ña | य | ya | श | śa | ||

| mūrdhanya (Cerebral) |

ट |

ṭa |

ठ |

ṭha |

ड |

ḍa |

ढ |

ḍha |

ण |

ṇa |

र | ra | ष |

ṣa | ||

| dantya (Dental) |

त | ta | थ | tha | द | da | ध | dha | न | na | ल | la | स | sa | ||

| oṣṭhya (Labial) |

प | pa | फ | pha | ब | ba | भ | bha | म | ma | व | va | ||||

- Rounding this out where applicable is ळ ḷa, which represented the intervocalic lateral flap allophone of the voiced retroflex stop in Vedic Sanskrit, and which is a phoneme in languages such as Marathi and Rajasthani.

- Beyond the Sanskritic set new shapes have rarely been formulated. Masica (1991:146) offers the following, "In any case, according to some, all possible sounds had already been described and provided for in this system, as Sanskrit was the original and perfect language. Hence it was difficult to provide for or even to conceive other sounds, unknown to the phoneticians of Sanskrit." Where foreign borrowings and internal developments did inevitably accrue and arise in New Indo-Aryan languages, they have been either ignored in writing, or dealt through means such as diacritics and ligatures (ignored in recitation).

- The most prolific diacritic has been the subscript nuqtā ़. Hindi uses it for the Persian sounds क़ qa, ख़ xa, ग़ ġa, ज़ za, and फ़ fa, and for the allophonic developments ड़ [[Retroflex flap|ṛ]]a and ढ़ ṛha.

- Sindhi's implosives are accommodated with underlining: ग [ɠə], ज [ʄə], ड [ɗə], ब [ɓə].

- Aspirated sonorants may be represented as conjuncts/ligatures with ह ha: म्ह mha, न्ह nha, ण्ह ṇha, व्ह vha, ल्ह lha, ळ्ह ḷha.

- Masica (1991:147) notes Marwari as using a special symbol for ḍa [ɗə] (while ड = [ɽə]).

Conjuncts

- You will only be able to see the ligatures if your system has a Unicode font installed that includes the required ligature glyphs (e.g. one of the TDIL fonts, see "external links" below).

As mentioned, successive consonants lacking a vowel in between them may physically join together as a 'conjunct' or ligature. The government of these clusters ranges from widely to narrowly applicable rules, with special exceptions within. While standardized for the most part, there are certain variations in clustering, of which the Unicode used on this page is just one scheme. The following are a number of rules —

- 24 out of the 36 consonants contain a vertical right stroke (ख, घ, ण etc.). As first or middle fragments/members of a cluster, they lose that stroke. e.g. त + व = त्व, ण + ढ = ण्ढ, स + थ = स्थ. श ś(a) appears as a different, simple ribbon-shaped fragment preceding व va, न na, च ca, ल la, and र ra, squishing down these second members. Thus श्व śva, श्न śna, श्च śca श्ल śla, and श्र śra.

- र r(a) as a first member it takes the form of a curved upward dash above the final character or its ā-diacritic. e.g. र्व rva, र्वा rvā, र्स्प rspa, र्स्पा rspā. As a final member with ट ठ ड ढ ङ छ it is two lines below the character, pointed downwards and apart. Thus ट्र ठ्र ड्र ढ्र ङ्र छ्र. Elsewhere as a final member it is a diagonal stroke jutting leftwards and down. e.g. क्र ग्र भ्र. त ta is shifted up to make त्र tra.

- As first members, remaining vertical stroke-less characters such as द d(a) and ह h(a) may have their second member, shrunken and minus its horizontal stroke, placed underneath. क k(a), छ ch(a), and फ ph(a) shorten their right hooks and join them directly to the following member.

Displayed then in the following table are all the viable symbols for the biconsonantal clusters of Sanskrit as listed in Masica (1991:161–162). Scroll your cursor over the conjuncts to reveal their romanizations.

| क | ख | ग | घ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य | र | ल | व | श | ष | स | ह | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| क | kk | kṇ | kt | kth | kn | km | ky | kr | kl | kv | kṣ | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ख | khy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ग | gg | gj | gdh | gn | gm | gr | gl | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| घ | ghn | ghm | ghr | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| च | cc | cch | jñ | cy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ज | jj | jjh | jñ | jm | jy | jr | jv | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ड | ḍr | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ण | ṇṭ | ṇṭh | ṇḍ | ṇḍh | ṇṇ | ṇm | ṇy | ṇv | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| त | tk | tkh | tt | tth | tn | tp | tph | tm | ty | tr | tv | ts | ||||||||||||||||||||

| थ | thn | thy | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| द | dg | dgh | dd | ddh | dn | db | dbh | dm | dy | dr | dv | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ध | dhn | dhm | dhy | dhr | dhv | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| न | nt | nth | nd | ndh | nn | nm | ny | nv | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| प | pt | pn | pp | pph | py | pr | pl | ps | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ब | bj | bd | bdh | bb | br | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| भ | bhr | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| म | mn | mp | mph | mb | mbh | mm | my | mr | ml | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| य | yy | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| र | rk | rkh | rg | rgh | rc | rch | rj | rjh | rṇ | rt | rth | rd | rdh | rn | rp | rb | rbh | rm | ry | rl | rv | rś | rṣ | rs | rh | |||||||

| ल | lk | lg | ld | lp | lph | lb | lm | ly | ll | lv | lh | |||||||||||||||||||||

| व | vy | vr | vv | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| श | śc | śn | śm | śy | śr | śl | śv | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ष | ṣk | ṣṭ | ṣṭh | ṣṇ | ṣp | ṣph | ṣm | ṣy | ṣv | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| स | sk | skh | st | sth | sn | sp | sph | sm | sy | sr | sv | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ह | hṇ | hn | hm | hy | hr | hv |

New Indo-Aryan languages may use the above forms for their Sanskrit loanwords (or otherwise).

Accent marks

The pitch accent of Vedic Sanskrit is written with various symbols depending on shakha. In the Rigveda, anudatta is written with a bar below the line (॒), svarita with a stroke above the line (॑) while udatta is unmarked.

Numerals

| ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

Transliteration

There are several methods of transliteration from Devanāgarī into Roman scripts. The most widely used transliteration method is IAST. However, there are other transliteration options.

The following are the major transliteration methods for Devanāgarī:

ISO 15919

A standard transliteration convention was codified in the ISO 15919 standard of 2001. It uses diacritics to map the much larger set of Brahmic graphemes to the Latin script. See also Transliteration of Indic scripts: how to use ISO 15919. The Devanagari-specific portion is nearly identical to the academic standard for Sanskrit, IAST.

IAST

The International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST) is the academic standard for the romanization of Sanskrit. IAST is the de-facto standard used in printed publications, like books and magazines, and with the wider availability of Unicode fonts, it is also increasingly used for electronic texts. It is based on a standard established by the Congress of Orientalists at Athens in 1912.

The National Library at Kolkata romanization, intended for the romanization of all Indic scripts, is an extension of IAST.

Harvard-Kyoto

Compared to IAST, Harvard-Kyoto looks much simpler. It does not contain all the diacritic marks that IAST contains. This makes typing in Harvard-Kyoto much easier than IAST. Harvard-Kyoto uses capital letters that can be difficult to read in the middle of words.

ITRANS

ITRANS is a lossless transliteration scheme of Devanāgarī into ASCII that is widely used on Usenet. It is an extension of the Harvard-Kyoto scheme. In ITRANS, the word Devanāgarī is written as "devanaagarii". ITRANS is associated with an application of the same name that enables typesetting in Indic scripts. The user inputs in Roman letters and the ITRANS pre-processor displays the Roman letters into Devanāgarī (or other Indic languages). The latest version of ITRANS is version 5.30 released in July, 2001.

ALA-LC Romanization

ALA-LC romanization is a transliteration scheme approved by the Library of Congress and the American Library Association, and widely used in North American libraries. Transliteration tables are based on languages, so there is a table for Hindi, one for Sanskrit and Prakrit, etc.

Encodings

ISCII

ISCII is a fixed-length 8-bit encoding. The lower 128 codepoints are plain ASCII, the upper 128 codepoints are ISCII-specific.

It has been designed for representing not only Devanāgarī, but also various other Indic scripts as well as a Latin-based script with diacritic marks used for transliteration of the Indic scripts.

ISCII has largely been superseded by Unicode, which has however attempted to preserve the ISCII layout for its Indic language blocks.

Devanāgarī in Unicode

The Unicode range for Devanāgarī is U+0900 .. U+097F. Grey areas indicate non-assigned code points.

| Devanagari[1] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+090x | ऀ | ँ | ं | ः | ऄ | अ | आ | इ | ई | उ | ऊ | ऋ | ऌ | ऍ | ऎ | ए |

| U+091x | ऐ | ऑ | ऒ | ओ | औ | क | ख | ग | घ | ङ | च | छ | ज | झ | ञ | ट |

| U+092x | ठ | ड | ढ | ण | त | थ | द | ध | न | ऩ | प | फ | ब | भ | म | य |

| U+093x | र | ऱ | ल | ळ | ऴ | व | श | ष | स | ह | ऺ | ऻ | ़ | ऽ | ा | ि |

| U+094x | ी | ु | ू | ृ | ॄ | ॅ | ॆ | े | ै | ॉ | ॊ | ो | ौ | ् | ॎ | ॏ |

| U+095x | ॐ | ॑ | ॒ | ॓ | ॔ | ॕ | ॖ | ॗ | क़ | ख़ | ग़ | ज़ | ड़ | ढ़ | फ़ | य़ |

| U+096x | ॠ | ॡ | ॢ | ॣ | । | ॥ | ० | १ | २ | ३ | ४ | ५ | ६ | ७ | ८ | ९ |

| U+097x | ॰ | ॱ | ॲ | ॳ | ॴ | ॵ | ॶ | ॷ | ॸ | ॹ | ॺ | ॻ | ॼ | ॽ | ॾ | ॿ |

Notes

| ||||||||||||||||

Devanāgarī Keyboard Layouts

Devanāgarī and Devanāgarī-QWERTY keyboard layouts for Mac OS X

The Mac OS X operating system supports convenient editing for the Devanāgarī script by insertion of appropriate Unicode characters with two different keyboard layouts available for use. To input Devanāgarī text, one goes to System Preferences → International → Input Menu and enables the keyboard layout that is to be used. The layout is the same as for INSCRIPT/KDE Linux:

INSCRIPT / KDE Linux

This is the India keyboard layout for Linux (variant 'deva')

Typewriter

Phonetic

See also

Software

- Apple Type Services for Unicode Imaging - Macintosh

- HindiWriter - The Phonetic Hindi Writer with AutoWord lookup and Spellcheck for MS Word and OpenOffice.org for Windows.

- Pango - open source (GNOME)

- Uniscribe - Windows

- WorldScript - Macintosh, replaced by the Apple Type Services for Unicode Imaging, mentioned above

- Baraha - Devanāgarī Input using English Keyboard

- Lipikaar - The indic script typing tool with support for Devanagari through a Windows desktop executable or Firefox Extension.

References

- ^ Salomon (2003:70)

- ^ a b Salomon (2003:75)

- ^ Salomon (2003:71)

- ^ Wikner (1996:6)

- ^ Snell (2000:44–45)

- ^ Snell (2000:64)

- ^ Snell (2000:45)

- ^ Snell (2000:46)

- ^ Salomon (2003:77)

Bibliography

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

- Template:Harvard reference.

External links

- Hindi Computing Wiki - Sarvagya (सर्वज्ञ)

- Omniglot.com - Devanagari Alphabets

- AncientScripts.com - Devanagari Intro

- मराठीतून मराठीचा वारसा पुढे नेणारी एक अस्सल मराठमॊळी वेबसाईट

- IS13194:1991 [1]

- Nepali Traditional keyboard Layout

- Nepali Romanized keyboard Layout

Electronic typesetting

Fonts

- Unicode Compliant Open Type Fonts including ligature glyphs (TDIL Data Centre)

Documentation

- The official Devanāgarī Document (pdf) from Govt. Of India.

- Unicode Chart for Devanāgarī

- Resources for typing in the Nepali language in Devanāgarī

- Resources for viewing and editing Devanāgarī

- Unicode support for Web browsers

- Creating and Viewing Documents in Devanāgarī

- Hindi/Devanāgarī Script Tutor

- A compilation of Tools and Techniques for Hindi Computing

Tools and applications

- List of Hindi Typing Tools

- IndiX, Indian language support for Linux, a site by the Indian National Centre for Software Technology

- Devanāgarī Tools: Wiki Sandbox, Devanagari Mail, Yahoo/Google Search & Devanāgarī Transliteration

- EnTrans - Entrans is an online, collaborative translation tool