Jimi Hendrix

Jimi Hendrix | |

|---|---|

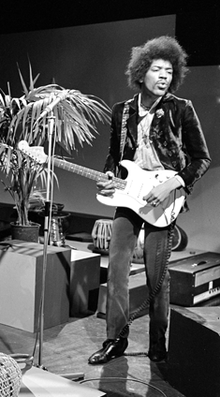

Hendrix performing for Dutch television show Hoepla in 1967 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Johnny Allen Hendrix |

| Born | November 27, 1942 Seattle, Washington, US |

| Died | September 18, 1970 (aged 27) Kensington, London, England |

| Genres | Psychedelic rock, hard rock, blues rock |

| Occupation(s) | Musician, singer, songwriter |

| Instrument(s) | Guitar, vocals |

| Years active | 1963–1970 |

| Labels | Vee-Jay, RSVP, Track, Barclay, Polydor, Reprise, Capitol, MCA |

| Website | www.jimihendrix.com |

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942 – September 18, 1970) was an American musician, singer and songwriter. Despite a limited mainstream exposure of four years, he is widely considered one of the most influential electric guitarists in the history of popular music and one of the most celebrated musicians of the 20th century.

In 1961 Hendrix enlisted in the US Army. He was granted an honorable discharge the following year. In 1963 he moved to Clarksville, Tennessee, playing numerous gigs on the chitlin' circuit. In 1964 he earned a spot in the Isley Brothers' backing band and later that year he found work with Little Richard, with whom he continued to play through mid-1965. He then joined Curtis Knight and the Squires before moving to England in late 1966 after having been discovered by bassist Chas Chandler of the Animals. In 1967 Hendrix earned three UK top ten hits with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, "Hey Joe", "Purple Haze" and "The Wind Cries Mary". Later that year, he achieved fame in the US after his performance at the Monterey Pop Festival. The world's highest paid performer, he headlined the Woodstock Festival in 1969 and the Isle of Wight Festival in 1970, before dying from barbiturate-related asphyxia at the age of 27.

Inspired musically by American rock and roll and electric blues, Hendrix favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume and gain, and was instrumental in developing the previously undesirable technique of guitar amplifier feedback. He helped to popularize the use of a wah-wah pedal in mainstream rock, and pioneered experimentation with stereophonic phasing effects in music recordings.

Hendrix was the recipient of several music awards during his lifetime and posthumously; the Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992 and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005. Rolling Stone ranked his three non-posthumous studio albums, Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love and Electric Ladyland among the 100 greatest albums of all time. Rolling Stone ranked him as the greatest guitarist of all time and the sixth greatest artist of all time.

Genealogy, childhood and military service

Jimi Hendrix's mixed genealogy included African American, Irish, and Cherokee ancestors. His paternal great-great-grandmother Zenora was a full-blooded Cherokee from Georgia who married an Irishman named Moore. They had a son Robert, who married an African American girl named Fanny. In 1883, Robert and Fanny had a daughter whom they named Zenora "Nora" Rose Moore, Hendrix's paternal grandmother.[1][nb 1] The illegitimate son of a black slave woman, also called Fanny, and her white overseer, Hendrix's paternal grandfather, Bertran Philander Ross Hendrix (born 1866), was named after his biological father, a grain merchant from Urbana, Ohio, and one of the wealthiest white men in the area at the time.[4] On June 10, 1919, Hendrix and Moore had a son they named James Allen Ross Hendrix (died 2002); people called him Al.[5]

In 1941, Al met Lucille Jeter (1925–1958) at a dance in Seattle; they married on March 31, 1942.[6] Drafted into the United States Army to serve in World War II, Al went to war three days after their wedding.[7] The first of Lucile's five children, Johnny Allen Hendrix was born November 27, 1942 in Seattle, Washington. In 1946, due to being unable to consult his father Al at the time of birth, his parents changed his name to James Marshall Hendrix, in honor of Al and his late brother Leon Marshall.[8][nb 2]

Stationed in Alabama at the time of Hendrix's birth, Al was denied the standard military furlough afforded servicemen for childbirth and placed by his commanding officer in the stockade to prevent his going AWOL to see his infant son in Seattle. He spent two months locked up without trial, and while in the stockade, received a telegram announcing his son's birth.[10][nb 3] During Al's three-year absence, Lucille struggled to raise their son, often neglecting him in favor of nightlife.[12] During this period he was mostly cared for by family members and friends, especially Lucille's sister Delores Hall and her friend Dorothy Harding.[13][14] Al received an honorable discharge from the U.S. Army on September 1, 1945. Two months later, unable to find Lucille, Al went to the Berkeley home of a family friend named Mrs. Champ, who had taken care of and had attempted to adopt Hendrix, and saw his son for the first time.[15][16]

After returning from service Al reunited with Lucille, but his difficulty finding steady work left the family impoverished. Both he and Lucille struggled with alcohol abuse, and they often fought when intoxicated. His parents' violence sometimes made Hendrix withdraw and hide in a closet in their home.[17] Hendrix relationship with his brother Leon (born 1948) was close but precarious; with Leon in and out of foster care, they lived with an almost constant threat of fraternal separation.[18] In addition to Leon, Hendrix had three other younger siblings: Joseph, born in 1949, Kathy in 1950, and Pamela, 1951, all of whom Al and Lucille gave up to foster care and adoption.[19] The family frequently moved, staying in cheap hotels and apartments around Seattle. On occasion, family would take Hendrix to Vancouver to stay at his grandmother's. A shy and sensitive boy, he was deeply affected by these experiences.[20] In later years, he confided to a girlfriend that he had been the victim of sexual abuse by a man in uniform.[21]

On December 17, 1951, when Hendrix was nine years old, his parents divorced; the court granted Al custody of he and Leon.[22] At thirty-three, Lucille had developed cirrhosis of the liver; she died on February 2, 1958 when her spleen ruptured.[23] Instead of taking James and Leon to attend their mother's funeral, Al gave them shots of whiskey and told them that was how men are supposed to deal with loss.[23][nb 4]

First instruments

At Horace Mann Elementary School in Seattle during the mid-1950s, Hendrix's habit of carrying a broom with him to emulate a guitar gained the attention of the school's social worker. After more than a year of his clinging to a broom like a security blanket, she wrote a letter requesting school funding intended for underprivileged children insisting that leaving him without a guitar might result in psychological damage.[24] Her efforts failed, and Al refused to buy him a guitar.[24][nb 5]

In 1957, while helping Al with a side-job, Jimi found a ukulele amongst the garbage that they were removing from a wealthy older woman's home. The woman told him that he could keep the instrument, which had only one string.[26] Learning by ear, he played single notes, following along to Elvis Presley songs, particularly Presley's cover of Leiber and Stoller's "Hound Dog".[27][nb 6] In mid-1958, at age 15, Hendrix acquired his first acoustic guitar, for $5.[29] Hendrix earnestly applied himself, playing the instrument for several hours daily, watching others and getting tips from more experienced guitarists, and listening to blues artists such as Muddy Waters, B.B. King, Howlin' Wolf, and Robert Johnson.[30] The first tune Hendrix learned how to play was the theme from Peter Gunn.[31]

Soon after he acquired the acoustic guitar, Hendrix formed his first band, the Velvetones. Without an electric guitar, he could barely be heard over the sound of the group. After about three months, he realized that he needed an electric guitar in order to continue.[32] In mid-1959 his father bought him a white Supro Ozark, his first electric guitar.[32] His first gig was with an unnamed band in the basement of a synagogue, Seattle's Temple De Hirsch. After too much showing off, the band fired him between sets.[33] Hendrix later joined the Rocking Kings, which played professionally at venues such as the Birdland club. When someone stole his guitar after he left it backstage overnight, Al bought him a red Silvertone Danelectro.[34] In 1958, Hendrix had completed his studies at Washington Junior High School, but he did not graduate from Garfield High School.[35][nb 7]

Army

Before he reached the age of 19 years, law enforcement authorities had twice caught Hendrix riding in stolen cars. When given a choice between spending time in prison or joining the Army, he chose the latter and enlisted on May 31, 1961.[38] After completing eight weeks of basic training at Fort Ord, California, the Army assigned him to the 101st Airborne Division and stationed him at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.[39] He arrived there on November 8, and soon after he wrote to his father: "There's nothing but physical training and harassment here for two weeks, then when you go to jump school ... you get hell. They work you to death, fussing and fighting."[40] In his next letter home, Hendrix, who had left his guitar at his girlfriend, Betty Jean Morgan's house in Seattle, asked his father to send him the guitar as soon as possible, stating: "I really need it now."[40] His father obliged and soon after the red Silvertone Danelectro on which Hendrix had hand-painted the words "Betty Jean", arrived safely at Fort Ord.[41] His apparent obsession with the instrument contributed to his neglect of his duties, which led to verbal taunting and physical abuse from his peers, who at least once hid the guitar from him until he had begged for its return.[42]

In November 1961, fellow serviceman Billy Cox walked past the service club and heard Hendrix playing guitar inside.[43] Cox, intrigued by the proficient playing, which he described as a combination of "John Lee Hooker and Beethoven", immediately borrowed a bass guitar from the club and the two jammed.[44] Within a few weeks, they began performing at base clubs on the weekends with other musicians in a loosely organized band called the Casuals.[45]

Hendrix completed his paratrooper training in just over eight months, and Major General C.W.G. Rich awarded him the prestigious Screaming Eagles patch on January 11, 1962.[40] By February, his personal conduct had begun to draw criticism from his superiors. They labeled him an unqualified marksmen and often caught him napping while on duty and failing to report for bed checks.[46] On May 24, Hendrix's platoon sergeant, James C. Spears filed a report in which he stated: "He has no interest whatsoever in the Army ... It is my opinion that Private Hendrix will never come up to the standards required of a soldier. I feel that the military service will benefit if he is discharged as soon as possible."[47] On June 29, 1962, Captain Gilbert Batchman granted Hendrix an honorable discharge on the basis of unsuitability.[48] Hendrix later spoke of his dislike of the army and falsely claimed that he had received a medical discharge after breaking his ankle during his 26th parachute jump.[49][nb 8]

Music career

Early years

In September 1963, after Cox was discharged from the Army, he and Hendrix relocated to Clarksville, Tennessee and formed a new band called the King Kasuals.[51] Hendrix had watched Butch Snipes play with his teeth in Seattle and by now Alphonso 'Baby Boo' Young, the other guitarist in the band, also performed this guitar gimmick.[52] Not to be upstaged, Hendrix also learned to play with his teeth, he commented: "The idea of doing that came to me in a town in Tennessee. Down there you have to play with your teeth or else you get shot. There's a trail of broken teeth all over the stage."[53] Although they began playing low-paying gigs at obscure venues, the band eventually moved to Nashville's Jefferson Street, the traditional heart of Nashville's black community and home to a thriving rhythm and blues music scene.[54] While in Nashville, they earned a brief residency playing at a popular venue in town, the Club del Morocco.[55] For the next two years, Hendrix made a living performing at a circuit of venues throughout the South who were affiliated with the Theater Owners' Booking Association (TOBA), widely known as the Chitlin' Circuit. In addition to performing in his own band, Hendrix performed in backing bands for various soul, R&B, and blues musicians, including Wilson Pickett, Chuck Jackson, Slim Harpo, Tommy Tucker, Sam Cooke, and Jackie Wilson.[56]

In January 1964, feeling he had outgrown the circuit artistically and frustrated by having to follow the rules of bandleaders, Hendrix decided to venture out on his own. He moved into the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, where he soon befriended Lithofayne Pridgeon, known as "Faye", who became his girlfriend.[57] Pridgeon, a Harlem native with connections throughout the area's music scene, provided Hendrix with shelter, support, and encouragement.[58] He also met the Allen twins, Arthur and Albert.[59][nb 9] In February 1964, Hendrix won first prize in the Apollo Theater amateur contest.[61] Hoping to land a gig, he played the club circuit and sat in with various bands. At the recommendation of a former associate of Joe Tex, Ronnie Isley granted Hendrix an audition that led to an offer to become the guitarist with the Isley Brothers' back-up band, the I.B. Specials; Hendrix readily accepted.[62]

First recordings

In March 1964, Hendrix recorded the two-part single "Testify" with the Isley Brothers. Released in June 1964, it failed to chart. After touring with the band through the summer of 1964, he quit after a gig in Nashville.[62][nb 10] In September 1964, Hendrix joined Little Richard's touring band, the Upsetters.[64][nb 11] During a stop in Los Angeles, Hendrix recorded his first and only single with Richard, "I Don't Know What You Got (But It's Got Me)", written by Don Covay and released by Vee-Jay Records.[66][nb 12] In July 1965, on Nashville's Channel 5 Night Train, he made his first television appearance. Performing in Little Richard's ensemble band, Hendrix backed up vocalists "Buddy and Stacy" on "Shotgun". The video recording of the show marks the earliest known footage of Hendrix performing.[64] He often clashed with Richard over tardiness, wardrobe, and his stage antics, so in late July 1965, Richard's brother Robert fired him.[68] He then briefly rejoined the Isley Brothers, and recorded a second single with them, "Move Over and Let Me Dance" backed with "Have You Ever Been Disappointed".[69]

Later that year, Hendrix joined a New York–based R&B band, Curtis Knight and the Squires, after meeting Knight in the lobby of a hotel where both men were staying.[70] Hendrix performed on and off with them for eight months.[71] In October 1965, he and Knight recorded the single, "How Would You Feel" backed with "Welcome Home"[72] and on October 15 Hendrix signed a three-year recording contract with entrepreneur Ed Chalpin. While the relationship with Chalpin was short-lived, his contract remained in force, which caused considerable problems for Hendrix later on in his career.[73][nb 13] During his time with Curtis Knight and the Squires, Hendrix briefly toured with Joey Dee and the Starliters and worked with King Curtis on several recordings including Ray Sharpe's two-part single, "Help Me".[75]

In mid-1966, Hendrix recorded with Lonnie Youngblood, a saxophone player who occasionally performed with Curtis Knight.[76] The sessions produced two singles for Youngblood: "Go Go Shoes"/"Go Go Place" and "Soul Food (That's What I Like)"/"Goodbye Bessie Mae".[77] Singles for other artists also came out of the sessions, including the Icemen's "(My Girl) She's a Fox"/ "(I Wonder) What It Takes" and Jimmy Norman's "That Little Old Groove Maker"/"You're Only Hurting Yourself".[78][nb 14] Hendrix earned his first composer credits for two instrumentals, "Hornets Nest" and "Knock Yourself Out", released as a Curtis Knight and the Squires single in 1966.[80]

In early 1966, Hendrix formed his own band, the Blue Flame, which included Randy Palmer (bass), Danny Casey (drums), and a 15-year-old guitarist named Randy Wolfe.[81][nb 15] By June 1966, the Blue Flame had begun playing at several clubs in New York, but their primary venue was a residency at the Cafe Wha? on MacDougal Street in Greenwich Village.[83] They gave their last concerts at the Cafe au Go Go, as John Hammond Jr.'s backing group.[84][nb 16]

The Jimi Hendrix Experience

In May 1966, Hendrix, struggling to earn a living wage playing the R&B circuit, briefly rejoined Curtis Knight and the Squires for an engagement at one of New York City's most popular nightspots, the Cheetah Club.[85] During a performance, Linda Keith, the girlfriend of Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards noticed Hendrix. She commented: "[His] playing mesmerised me".[85] She arranged for him to join her for a drink, and the two soon became friends.[85]

Keith recommended Hendrix to Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham and producer Seymour Stein. They failed to see Hendrix's musical potential, and rejected him.[86] She then referred Hendrix to Chas Chandler, who was leaving the Animals and interested in managing and producing artists. Chandler liked the song "Hey Joe" and was convinced he could create a hit single with the right artist.[87] Impressed with Hendrix's version of the song, Chandler brought him to London on September 23, 1966, and signed him to a management and production contract with himself and ex-Animals manager Michael Jeffery.[88] On September 24, Hendrix gave an impromptu solo performance at the Scotch-Club. That night, he began a relationship with Kathy Etchingham that lasted until February 1969.[89][nb 17]

Immediately following Hendrix's arrival in London, Chandler began recruiting members for a band designed to highlight the guitarist's talents, the Jimi Hendrix Experience.[91] Hendrix met guitarist Noel Redding at an audition for the New Animals, where Redding's knowledge of blues progressions impressed Hendrix, who stated that he also liked Redding's hairstyle.[92] Chandler asked Redding if he wanted to play bass guitar in Hendrix's band; Redding agreed.[92] Chandler then began looking for a drummer and soon after, he contacted Mitch Mitchell through a mutual friend. Mitchell, who had recently been fired from Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, participated in a rehearsal with Redding and Hendrix where they found common ground in their shared interest in rhythm and blues. When Chandler phoned Mitchell later that day to offer him the position, he readily accepted.[93] Chandler also convinced Hendrix to change the spelling of his first name from "Jimmy" to the more exotic looking "Jimi".[94]

On September 30, Chandler brought Hendrix to the London Polytechnic at Regent Street, where Cream was scheduled to perform, and it was then that Hendrix and Eric Clapton first met. Clapton commented: "He asked if he could play a couple of numbers. I said, 'Of course', but I had a funny feeling about him."[91] Halfway through Cream's set, Hendrix took the stage and performed a frantic version of the Howlin' Wolf song "Killing Floor".[91] In 1989, Clapton described the performance: "He played just about every style you could think of, and not in a flashy way. I mean he did a few of his tricks, like playing with his teeth and behind his back, but it wasn't in an upstaging sense at all, and that was it ... He walked off, and my life was never the same again".[91]

UK success

In mid-October 1966, Chandler arranged for the Experience to accompany Johnny Hallyday as his support act for a brief tour of France.[94] Their enthusiastically received 15-minute performance at the Olympia theatre in Paris on October 18 marks the earliest known recording of the band.[94] In late October, Kit Lambert and Chris Stamp, managers of the Who, signed the Experience to their newly formed record label, Track Records, who released the Experience's first single on October 23.[95] "Hey Joe", a cover of the Billy Roberts song, which included a female backing chorus provided by the Breakaways, was backed by Hendrix's first songwriting effort, "Stone Free".[96]

In mid-November, they performed at London's newly opened nightclub the Bag O'Nails, with Clapton, John Lennon, Paul McCartney, Jeff Beck, Pete Townshend, Brian Jones, Mick Jagger, and Kevin Ayers in attendance.[97] Ayers described the crowd's reaction as stunned disbelief: "All the stars were there, and I heard serious comments, you know 'shit', 'Jesus', 'damn' and other words worse than that."[97] The performance's success earned Hendrix his first interview, published in Record Mirror with the headline: "Mr. Phenomenon".[97] "Now hear this ... we predict that [Hendrix] is going to whirl around the business like a tornado", wrote Bill Harry, who asked the rhetorical question: "Is that full, big, swinging sound really being created by only three people?"[98] Hendrix commented: "We don't want to be classed in any category ... If it must have a tag, I'd like it to be called, 'Free Feeling'. It's a mixture of rock, freak-out, rave and blues".[99] After appearances on the UK television shows, Ready Steady Go! and the Top of the Pops, "Hey Joe" entered the UK charts on December 29, 1966, peaking at number six.[100] Further success came in March 1967 with the UK number three hit, "Purple Haze", and in May with "The Wind Cries Mary", which remained on the UK charts for eleven weeks, peaking at number six.[101]

On March 31, 1967, while booked to appear at the London Astoria, Hendrix and Chandler discussed ways in which they could increase the band's media exposure. Chandler asked journalist Keith Altham for advice, who suggested that they needed to do something more dramatic than the stage show of the Who, which involved the smashing of instruments. Hendrix replied: "Maybe I can smash up an elephant", to which Altham replied: "Well, it's a pity you can't set fire to your guitar".[102] Chandler immediately asked road manager Gerry Stickells to get them some lighter fluid. Hendrix gave an especially dynamic performance before setting his guitar on fire at the end of his 45-minute set. In the wake of the notable stunt, London's press labeled Hendrix the "Black Elvis" and the "Wild Man of Borneo".[103][nb 18]

Are You Experienced

After the moderate UK chart success of their first two singles, "Hey Joe" and "Purple Haze", the Experience began assembling material for a full-length LP.[105] Recording began at De Lane Lea Studios and later moved to the prestigious Olympic Studios.[105] In 2005, Rolling Stone described the double-platinum Are You Experienced as Hendrix's "epochal debut", and they ranked it the 15th greatest album of all-time, noting his "exploitation of amp howl", describing his guitar playing as "incendiary ... historic in itself" and the songs as "soul music for inner space."[106] The founding editor of Guitar World called it, "the album that shook the world ... leaving it forever changed".[107][nb 19] Released in the UK on May 12, 1967, Are You Experienced spent 33 weeks on the charts, peaking at number 2.[109][nb 20] The LP was prevented from reaching the top of the UK charts by the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band.[111] As with Sgt. Pepper, Are You Experienced was recorded using four-track technology.[105]

On June 4, 1967, Hendrix opened a show at the Saville Theatre in London with his rendition of Sgt. Pepper's title track, released just three days previous. Beatles manager Brian Epstein owned the Saville at the time, and both George Harrison and Paul McCartney attended the performance. McCartney described the moment: "It's still a shining memory for me ... The curtains flew back and he came walking forward playing 'Sgt. Pepper'. It's a pretty major compliment in anyone's book. I put that down as one of the great honors of my career."[112] Released in the US in August by Reprise Records, Are You Experienced, reached number 5 on the Billboard Hot 100.[113][nb 21]

US success

Although popular in Europe at the time, the Experience's first US single, "Hey Joe"/"51st Anniversary", released May 1, 1967, failed to reach the Billboard Hot 100 chart.[115] Their fortunes soon improved when Paul McCartney recommended them to the organizers of the Monterey International Pop Festival. McCartney insisted that the festival would be incomplete without Hendrix, who he called "an absolute ace on the guitar", and he agreed to join the board of organizers on the condition that the Experience perform at the festival in mid-June.[116]

Introduced by Brian Jones as "the most exciting performer [he had] ever heard", Hendrix opened with a fast arrangement of Howlin' Wolf's song "Killing Floor", wearing what author Keith Shadwick described as "clothes as exotic as any on display elsewhere ... He was not only something utterly new musically, but an entirely original vision of what a black American entertainer should and could look like."[117] The Monterey performance also included "Hey Joe", a rendition of B.B. King's "Rock Me Baby", and Bob Dylan's "Like a Rolling Stone", as well as four original compositions: "Foxy Lady", "Can You See Me", "The Wind Cries Mary", and "Purple Haze".[112] The set ended with Hendrix burning his guitar on stage, then smashing it before tossing pieces out to the audience. Filmed by D. A. Pennebaker, and later included in the concert documentary Monterey Pop, the performance helped earn Hendrix the attention of the US public.[118] After the festival, the Experience played a series of concerts at Bill Graham's Fillmore, with Big Brother and the Holding Company, and Jefferson Airplane, before replacing the latter at the top of the bill after embarrassing the band by out-performing them musically.[119]

Following their successful West Coast introduction, which included a free open air concert at Golden Gate Park and a concert at the Whisky a Go Go, they were booked as an opening act for the pop group the Monkees, on their first American tour.[120] They had asked for Hendrix because they were fans, but their young audience disliked the Experience, who left the tour after six shows.[121] Chandler later admitted that he had engineered the Monkees tour to gain publicity for Hendrix.[122]

Axis: Bold as Love

The title track and finale of the second Experience album, Axis: Bold as Love (1967), features the first recording of stereo phasing.[123][nb 22] Author Keith Shadwick described the song as "possibly the most ambitious piece on Axis, the extravagant metaphors of the lyrics suggesting a growing confidence" in Hendrix's songwriting.[125] The album's opening track, "EXP", featured innovative use of microphonic and harmonic feedback.[126] It also utilized a stereo panning effect in which sounds emanating from Hendrix's guitar move through the stereo image, revolving around the listener.[127]

The album's scheduled pre-Christmas release date was almost delayed when Hendrix lost the master tape of side one of the LP, leaving it in the back seat of a London taxi. With the deadline looming, Hendrix, Chandler and engineer Eddie Kramer remixed most of side one in a single overnight session, but they could not match the quality of the lost mix of "If 6 Was 9". Bassist Noel Redding had a tape recording of this mix, which had to be smoothed out with an iron as it had gotten wrinkled.[128] During the verses of the song Hendrix doubled his vocal line with his guitar, which he played one octave lower.[129] The founding editor of Guitar World described the LP as "a voyage to the cosmos".[130] According to author Peter Doggett, the work "heralded a new subtlety in Hendrix's work".[131] Mitchell commented: "Axis was the first time that it became apparent that Jimi was pretty good working behind the mixing board, as well as playing, and had some positive ideas of how he wanted things recorded. It could have been the start of any potential conflict between him and Chas in the studio."[132]

Hendrix voiced his disappointment regarding their having re-mixed the album so quickly, and he felt that it could have been better had they been given more time.[133] He also expressed dismay regarding the album cover art work, which depicts Hendrix and the Experience as various forms of Vishnu, incorporating a painting of them by Roger Law, from a photo-portrait by Karl Ferris. Hendrix stated that the cover would have been more appropriate had it highlighted his American Indian heritage.[134] Track Records released the album in the UK on December 16, 1967, where it peaked at number 5, spending 16 weeks on the charts.[101] In February 1968, Axis: Bold as Love reached number 3 in the US.[135]

Electric Ladyland

In November 1968, Hendrix released his third and final non-posthumous studio album, Electric Ladyland. According to author Michael Heatley, "most critics agree" that the album is "the fullest realization of Jimi's far-reaching ambitions."[136] The double LP was the first Experience album to be mixed entirely in stereo.[137] Recording began at the newly opened Record Plant Studios with Chas Chandler as producer aided by engineers Eddie Kramer and Gary Kellgren.[138] During recording sessions for the album, Chandler became increasingly frustrated with Hendrix's perfectionism and his demands for numerous re-takes. Hendrix also allowed various friends and guests to join them in the studio, which contributed to a chaotic and crowded environment in the control room, leading Chandler to sever his professional relationship with Hendrix.[136]

During recording sessions for the album, Hendrix began experimenting with different combinations of musicians and instruments. It contained his first recorded song to feature the use of a wah-wah pedal, "Burning of the Midnight Lamp".[139] During production, Hendrix appeared at an impromptu jam with B.B. King, Al Kooper, and Elvin Bishop.[140][nb 23] In November 1968, the album reached number 1 in the US, spending two weeks at the top spot.[142] The LP peaked at number 6 in the UK, spending 12 weeks on the chart.[101] The founding editor of Guitar World described the album as "Hendrix's masterpiece".[143]

Breakup of the Experience

Mitch and I hung out a lot together, but we're English. If we'd go out, Jimi would stay in his room. But any bad feelings came from us being three guys who were traveling too hard, getting too tired, and taking too many drugs ... I liked Hendrix. I don't like Mitchell.[144]

—Noel Redding on the break-up of the Experience

After residing in the US for more than a year, Hendrix temporarily moved back into his girlfriend Kathy Etchingham's rented Brook Street flat, next door to the Handel House Museum, in the West End of London. During this time, the band toured Scandinavia, Germany, and included a final French concert. They later performed two sold-out concerts at London's Royal Albert Hall on February 18 and 24, 1969, which were the last European appearances of this line-up of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Gold and Goldstein filmed these shows; however, as of 2013[update], they have not seen an official release.[145]

Redding formed his own band Fat Mattress, allowing him to play his preferred instrument, the guitar.[146] He spent less time with Hendrix, which resulted in Hendrix playing many of the bass parts on Electric Ladyland.[136] Fruitless recording sessions at Olympic in London; Olmstead and the Record Plant in New York that ended on April 9, which produced a remake of "Stone Free" for a possible single release, were the last to feature Redding. Hendrix then flew Billy Cox to New York and started recording and rehearsing with him on April 21 as a replacement for Redding.[147]

The last Experience concert took place on June 29, 1969, at Barry Fey's Denver Pop Festival, a three-day event held at Denver's Mile High Stadium that was marked by police using tear gas to control the audience.[148] They narrowly escaped from the venue in the back of a rental truck which was partly crushed by fans trying to escape the tear gas. The next day, Redding quit the Experience and returned to London.[148] He blamed Hendrix's plans to expand the group without allowing for his input as a primary reason for leaving.[149]

After the departure of Noel Redding from the group, Hendrix rented the eight-bedroom Ashokan House in the hamlet of Boiceville near Woodstock in upstate New York, where he spent some time in mid-1969.[150] Manager Michael Jeffery, who owned a house in Woodstock, arranged the stay, with hopes that the respite would produce a new album. Mitchell was unavailable to help fulfill Hendrix's commitments at this time, which included his first appearance on US TV – on The Dick Cavett Show – where he was backed by the studio orchestra, and an appearance on The Tonight Show where he appeared with Cox and session drummer Ed Shaughnessy.[151]

Woodstock

Hendrix, who was by 1969 the world's highest paid performer, performed at the Woodstock Music Festival along with many of the most popular bands of the time.[152] The festival took place on farmland rented from Max Yasgur, in Bethel, New York, from August 15 to 18, 1969. For the performance, Hendrix added rhythm guitarist Larry Lee and conga players Juma Sultan and Jerry Velez. With Mitchell, Hendrix called this lineup Gypsy Sun and Rainbows. They rehearsed for less than two weeks before their performance. According to Mitchell, the band never connected musically. By the time of the performance, Hendrix had been awake for three days, contributing a rawness to the performance.[153]

Before Hendrix arrived at the festival, he had heard reports that crowds of kids were swelling to epic proportions, giving Hendrix, who did not like performing in front of large crowds, cause for concern.[154] Hendrix was an important draw for the festival and received more pay than the other performers, which was $18,000 for his performance plus $12,000 for the rights to film him. As his scheduled time slot of midnight on Sunday drew closer, he indicated that he preferred to wait and close the show in the morning. This delayed when the band finally took the stage, which ended up being around 8:30 am Monday morning. The audience, which had peaked at an estimated 400,000 people during the festival, was now reduced to about 30–40,000; many of whom merely waited to catch a glimpse of Hendrix before leaving during his performance.[154] Hendrix and his band were introduced by the festival MC, Chip Monck, as "the Jimi Hendrix Experience", but once on stage Hendrix clarified, saying, "We decided to change the whole thing around and call it Gypsy Sun and Rainbows. For short, it's nothin' but a 'Band of Gypsys'".[155]

Hendrix's rendition of the U.S. national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner" occurred about 3/4 into their set. Hendrix used feedback and sustain to replicate the sound of rockets. Although pundits quickly branded the song as a political manifesto against the Vietnam War, Hendrix himself never explained its meaning other than to say at a press conference three weeks later, "We're all Americans ... it was like 'Go America!'... We play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static, see".[156] The song would become "part of the sixties Zeitgeist" as it was captured forever in the Woodstock film.[157] Hendrix's image performing this number during the day wearing a blue-beaded white leather jacket with fringe and a red head scarf, has since been regarded as a defining moment of the 1960s.[154][158][nb 24]

Hendrix performed "Hey Joe" as the encore of their set, concluding the 3½-day festival. Upon leaving the stage, he collapsed from exhaustion.[157] After Woodstock, this lineup appeared together on only two more occasions. Recordings of them are included on the MCA Records box set The Jimi Hendrix Experience and the posthumous Hendrix album, South Saturn Delta. Their final session together before Lee and Velez left the band took place on September 16.[160]

Band of Gypsys

In 1968, a contractual dispute arose regarding a 1965 agreement Hendrix had entered into with producer Ed Chalpin. The resolution for the dispute required Hendrix to record an album of new material for Chalpin: Hendrix chose to record the live LP, Band of Gypsys.[161]

Amidst widespread social upheaval in the US including the African-American Civil Rights Movement, the continued escalation of the Vietnam War and several notable assassinations, Hendrix created a new all-black power-trio with Cox and drummer Buddy Miles, formerly with Wilson Pickett, the Electric Flag and the Buddy Miles Express. Critic John Rockwell described Hendrix and Miles as jazz-rock fusionists and their collaboration as pioneering.[162] Biographers have speculated that Hendrix formed the band in an effort to appease members of the Black Power movement and others in the black communities who called for him to use his fame to speak up for their civil rights.[163]

Hendrix had been recording with Cox since April and jamming with Miles since September, and they wrote and rehearsed material which they performed at a series of four shows over two nights on New Year's Eve and New Year's Day at the Fillmore East. Recordings of these concerts became the material for the LP, which was produced by Hendrix.[164] The album contains the track "Machine Gun", described by musicologist Andy Aledort as the pinnacle of Hendrix's career, and "the premiere example of Hendrix's unparalleled genius as a rock guitarist ... In this performance, Jimi transcended the medium of rock music, and set an entirely new standard for the potential of electric guitar."[165]

"The most brilliant, emotional display of virtuoso electric guitar that I have ever heard." [166]

—Concert promoter Bill Graham, on the Band of Gypsys shows

The Band of Gypsys album was the only official live, complete LP of Hendrix's music released during his lifetime; a couple of tracks from Woodstock and one side of an LP of tracks from his Monterey show were released later that year. The album reached the top ten in both the US and the UK in April 1970.[166] They released a single, "Stepping Stone", and recorded three other studio songs slated for Hendrix's future LP. In 1999, the tapes from the four Fillmore concerts were remastered and additional tracks and edits were released as Live at the Fillmore East. Litigation with Chalpin ended in 2007, when the court fined him nearly $900,000 for failure to abide by contractual limitations and failure to pay Experience Hendrix L.L.C. its court ordered royalties.[167]

In late January 1970, Mitchell and Redding flew to New York and signed contracts with Jeffery for the upcoming Jimi Hendrix Experience tour. The following day, a second and final Band of Gypsys appearance occurred at Madison Square Garden, for a twelve-act festival benefiting the anti-Vietnam War Moratorium Committee titled the "Winter Festival for Peace". Delays forced Hendrix to take the stage at an exceedingly late and inopportune 3 am, and obviously not in the proper physical condition to play. He attempted a performance of "Who Knows" before snapping a vulgar response at a woman who shouted a request for "Foxy Lady". He then played, "Earth Blues" before telling the audience: "That's what happens when earth fucks with space—never forget that".[168] During the song he briefly sat down on the drum riser before walking off stage. Various unverifiable assertions have been proffered to explain this bizarre scene. Buddy Miles claimed that manager Michael Jeffery dosed Hendrix with LSD in an effort to sabotage the current band and bring about the return of the Experience lineup, but none of Hendrix's other close associates verifies his statement.[169]

Cry of Love tour

A week after the abruptly ended Band of Gypsys show, Rolling Stone interviewed Hendrix, Mitchell and Redding before their upcoming tour dates as a reunited Experience. However, Redding never made the time to rehearse, as Hendrix continued to work with Billy Cox. Redding was not told he was not going to be playing until the pretour rehearsals. This final "Jimi Hendrix Experience" lineup is often referred to as the "Cry of Love" band, named after the Cry of Love Tour to distinguish it from the original. Billing, adverts, tickets etc. on the tour used "Jimi Hendrix Experience" or occasionally, as previously, just "Jimi Hendrix".[170]

Two of Hendrix's final recordings were the lead guitar parts on "Old Times Good Times" from Stephen Stills' hit eponymous album (1970), and on "The Everlasting First" from Arthur Lee's new incarnation of Love, not so successful and aptly named LP False Start both tracks were recorded with these old friends on a fleeting and unexplained visit to London in March 1970, following Kathy Etchingham's marriage.[171]

Hendrix spent the first four months of 1970 working on his next LP tentatively titled First Rays of the New Rising Sun, recording during the week and playing live on the weekends. The Cry of Love tour, launched that April at the L.A. Forum, was partly undertaken to earn money to repay the Warner Bros. loan for completing his Electric Lady Studios. Performances on this tour featured Hendrix, Cox, and Mitchell playing new material alongside older audience favorites. The American leg of the tour included 30 performances and ended at Honolulu, Hawaii, on August 1, 1970. A number of these shows were recorded and produced some of Hendrix's most memorable live performances. At one of them, the second Atlanta International Pop Festival, on July 4, Hendrix played to the largest American audience of his career.[172][nb 25]

Electric Lady Studios

In 1968, Hendrix and Jeffery had jointly invested in the purchase of the Generation Club in Greenwich Village. Their initial plans to reopen the club were changed when the pair decided that the investment would serve them much better as a recording studio. After the exorbitant studio fees incurred during the lengthy Electric Ladyland sessions, Hendrix was seeking a recording environment that suited him. In August 1970, Electric Lady Studios was opened in New York. Architect and acoustician John Storyk designed the studio specifically for Hendrix, with round windows and a machine capable of generating ambient lighting in a myriad of colors. It was designed to have a relaxing feel to encourage Hendrix's creativity, but at the same time provide a professional recording atmosphere.[173]

Hendrix spent only two and a half months recording in Electric Lady, most of which took place while the final phases of construction were still ongoing. Following a mastering session at Sterling Sound on August 26, they held an opening party later that day for Electric Lady Studios. Hendrix left for London after the party and never returned to the newly finished studio.[174] He boarded an Air India flight for London with Billy Cox, joining Mitch Mitchell to perform at the Isle of Wight Festival.[175]

European tour

When the Experience began their 1970 European tour, Hendrix, longing for his new studio and creative outlets, was not eager to fulfill the commitment. In Aarhus, Hendrix abandoned the performance after only three songs, remarking: "I've been dead a long time".[176] On September 6, 1970, his final concert performance, Hendrix was met with booing and jeering by fans at the Isle of Fehmarn Festival in Germany, due to his non-appearance at the end of the previous night's bill owing to the torrential rain and risk of electrocution. Several acts played after Hendrix left the stage and later, part of the stage was burnt during the first appearance of Ton Steine Scherben. Cox quit the tour and headed home to Memphis, Tennessee, reportedly suffering from severe paranoia after either taking LSD or being given it unknowingly, earlier in the tour.[177] A live recording of the concert was later released as Live at the Isle of Fehmarn.[178]

Hendrix returned to London, where he reportedly spoke to Chas Chandler, Eric Burdon, and others about leaving his manager, Michael Jeffery. Hendrix's last public performance was an informal jam at Ronnie Scott's Jazz Club in Soho with Burdon and his latest band, War. Much of this was recorded on a Sony cassette recorder by Bill Baker, who was present throughout the entire performance. Two tracks featuring Hendrix, "Mother Earth" and "Tobacco Road", were later included on a bootleg LP without permission from Baker. The release was titled Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window?, and was produced in the 1970s from Baker's poor quality audio tape. In 2009, the entire recording entered general circulation within the collecting community. It was remastered in December 2010, including tracks from the same night's performance by War. It is Hendrix's last known recording; he died less than 48 hours later.[179]

Death, post-mortem, and burial

Although the details of his last day and death are unclear and widely disputed, Hendrix had spent much of September 17 in London with Monika Dannemann, the only witness to his final hours.[180] Dannemann stated that she had prepared a meal for them at her apartment in the Samarkand Hotel, 22 Lansdowne Crescent, Notting Hill, sometime around 11 p.m., when they shared a bottle of wine.[181] She drove Hendrix to the residence of an acquaintance at approximately 1:45 a.m., where he remained for about an hour before she picked him up and drove them back to her flat at 3 a.m.[182] Dannemann said they talked until around 7 a.m., when they went to sleep. She awoke around 11 a.m., and found Hendrix breathing, but unconscious and unresponsive. She called for an ambulance at 11:18 a.m.; they arrived on the scene at 11:27 a.m.[183] Paramedics then transported Hendrix to St Mary Abbot's Hospital where Dr. John Bannister pronounced him dead at 12:45 p.m., on September 18, 1970.[184]

To determine the cause of death, coroner Gavin Thurston ordered a post-mortem examination on Hendrix's body, which was performed on September 21 by Professor Robert Donald Teare, a forensic pathologist.[185] Thurston concluded the inquest on September 28, and concluded that Hendrix aspirated his own vomit and died of asphyxia while intoxicated with barbiturates.[186] Citing "insufficient evidence of the circumstances", he declared an open verdict.[187] Dannemann later stated that Hendrix had taken nine of her prescribed Vesparax sleeping tablets, 18 times the recommended dosage.[188]

On September 29, Hendrix's body was flown to Seattle, Washington.[189] After a service at Dunlop Baptist Church on October 1, he was interred at Greenwood Cemetery in Renton, Washington, the location of his mother's gravesite.[190] Hendrix's family and friends traveled in twenty-four limousines. More than two hundred people attended the funeral, including several notable musicians such as original Experience members Mitch Mitchell and Noel Redding, as well as Miles Davis, John Hammond and Johnny Winter.[191]

Alleged progeny

Hendrix performed in Sweden frequently throughout his career, and his only son James Daniel Sundquist was born there in 1969 to a Swede, Eva Sundquist. The relation has been recognized by the Swedish courts and Sundquist received a monetary settlement from Experience Hendrix LLC.[192]

Drug use and violence

Hendrix was widely associated with the use of psychedelic drugs, particularly lysergic acid diethylamide. He first experimented with the drug when he met Linda Keith in late 1966; he had previously smoked cannabis. He also used amphetamines, particularly while touring.[193] Friends and bandmates reported that Hendrix would often become angry and violent when he drank too much alcohol.[194] Though illicit drugs alone did not seem to produce a significant negative effect on him, when he mixed them with alcohol, he would often become incendiary.[195] Hendrix friend, Herbie Worthington, explains: "You wouldn't expect somebody with that kind of love to be that violent ... He just couldn't drink ... he simply turned into a bastard."[196] A girlfriend of Hendrix's, Carmen Borrero, required stitches after he hit her above her eye with a vodka bottle during a drunken, jealous rage.[196]

In January 1968, the Experience travelled to Sweden for a one-week tour of Europe. During the early morning hours of the first day, Hendrix became engaged in a drunken brawl in the Hotel Opalen in Stockholm, smashing a plate-glass window and injuring his right hand, for which he received medical treatment.[196] The incident culminated in his arrest, though the authorities released him pending a court appearance on the 16th.[197] The remainder of the tour was uneventful, though Hendrix had to spend some time in Sweden awaiting his trial, which resulted in a large fine.[198] After the burglary of his house in Benedict Canyon, California, while under the influence of drugs and alcohol, he punched his friend Paul Caruso and accused him of the theft. Hendrix then chased Caruso away from the residence while throwing stones at him.[199]

On May 3, 1969, while checking through Canadian customs at Toronto Pearson International Airport, authorities arrested Hendrix for drug possession after finding a small amount of heroin and hashish in his luggage. After being released on a CAN$10,000 cash bail the same day, only four hours before his show was scheduled to begin, the Experience performed at Maple Leaf Gardens that night. The courts required Hendrix to appear before a judge at a later date. In his trial defense Hendrix claimed that a fan had slipped the drugs into his bag without his knowledge; he was acquitted of the charges.[200]

Recordings and posthumous releases

Hendrix's recordings were originally released in North America on Reprise Records, a division of Warner Communications, and were released internationally on Polydor Records.[201] Capitol Records released the Band of Gypsys album in the US and Canada.[202] British releases of his albums up to and including The Cry of Love were first issued on the independent label Track Records, which was originally created by the managers of the Who. Polydor later absorbed the label.[201]

In 1994, the Hendrix family prevailed in its long standing legal attempt to gain control of his music, and subsequently licensed the recordings to MCA Records through the family-run company Experience Hendrix LLC, formed in 1995.[203] In August 2009, Experience Hendrix announced that it had entered a new licensing agreement with Sony Music Entertainment's Legacy Recordings division which would take effect in 2010.[204]

Some of Hendrix's unfinished material was released as the 1971 title The Cry of Love.[205] The album was well received and charted in several countries. However, the album's producers, Mitchell and Kramer, would later complain that due to contractual reasons, they were unable to make use of all the tracks they wanted due to some tracks being used for 1971's Rainbow Bridge and 1972's War Heroes.[206] Material from The Cry of Love was re-released in 1997 as First Rays of the New Rising Sun, along with the rest of the tracks that Mitchell and Kramer wanted to include.[207]

In 2010, Legacy Recordings and Experience Hendrix LLC launched the 2010 Jimi Hendrix Catalog Project, starting with the release of Valleys of Neptune in March.[208] Legacy has also released deluxe CD/DVD editions of the Hendrix albums Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold As Love, Electric Ladyland and First Rays of the New Rising Sun, as well as the 1968 compilation album Smash Hits.[209][nb 26] Hendrix's rough demos for a concept album, Black Gold, are now in the possession of Experience Hendrix LLC, but as of 2013 no official release date has been announced.[211]

Musical influences

I don't happen to know much about jazz. I know that most of those cats are playing nothing but blues, though—I know that much. [212]

—Hendrix on jazz music

As an adolescent during the 1950s, rock and roll artists such as Elvis Presley, Little Richard and Chuck Berry earned Hendrix's interest.[213] In 1968, he told Guitar Player magazine that electric blues artists including Muddy Waters, Elmore James and B.B. King influenced him during the beginning of his career, he also cited Eddie Cochran as an early influence.[214] In 1970, he told Rolling Stone that he was a fan of western swing artist Bob Wills, and while he lived in Nashville, the television show, the Grand Ole Opry.[215] Of Muddy Waters, the first electric guitarist of which Hendrix became aware, he said: "I heard one of his records when I was a little boy and it scared me to death because I heard all of these sounds."[216]

Band of Gypsys bassist, Billy Cox, stated that during their time serving in the US military, he and Hendrix listened to mostly southern blues artists such as Jimmy Reed, B.B. King and Albert King. According to Cox, "Albert King was a very, very powerful influence" on Hendrix.[214] Howlin' Wolf also influenced Hendrix, who performed Wolf's "Killing Floor" as the opening song to the set of his US debut at the Monterey Pop Festival.[217] Soul guitarist Curtis Mayfield also significantly influenced Hendrix.[218]

Equipment

Guitars

Although Hendrix owned and used a variety of guitars during his career, his guitar of choice and the instrument that became most associated with him, was the Fender Stratocaster. He started playing the model in 1966 and thereafter used it prevalently in his stage performances and recordings.[219] Hendrix used right-handed guitars, turned upside down and restrung for left-hand playing.[220] This had an important effect on his guitar sound: because of the slant of the Strat's bridge pickup, his lowest string had a bright sound while his highest string had a mellow sound, the opposite of the Stratocaster's intended design.[221] His heavy use of the tremolo bar often detuned his guitar strings necessitated frequent tunings.[222] In addition to Stratocasters, Hendrix also used Fender Jazzmasters, Duosonics, two different Gibson Flying Vs, a Gibson Les Paul, three Gibson SGs, a Gretsch Corvette and a Fender Jaguar, as well as several other brands.[223] He used a white Gibson SG Custom for his performances on The Dick Cavett Show in September 1969, and a black Gibson Flying V during the Isle of Wight festival in 1970.[224][nb 27]

On December 4, 2006, one of Hendrix's 1968 Fender Stratocaster guitars with a sunburst design was sold at a Christie's auction for US$168,000.[226] Described as the first guitar Hendrix set fire to, another of his Stratocasters was sold at an auction for a record price in London two years later in 2008. Daniel Boucher, an American collector from Boston, paid £280,000 ($497,500) for the guitar.[227][228][229] This guitar was set aflame at the end of the Astoria concert in March 1967. Hendrix's action "sent roadies rushing to put out the flames and left Hendrix needing treatment for minor burns."[230] Rescued by Hendrix's press officer, Tony Garland, it was his nephew who came forward in 2007 and put the guitar up for auction. The guitar had been forgotten in Tony Garland's parents' garage for some forty years. In 2009, some experts in Hendrix's guitars questioned whether the guitar Boucher bought was in fact an elaborate forgery.[231]

Amplifiers and effects

Hendrix was a catalyst in the development of modern guitar effects pedals. His high volume and use of feedback required robust and powerful amplifiers. For the first few rehearsals he used Vox and Fender amplifiers. Sitting in with Cream, Hendrix played through a new range of high-powered guitar amps being made by London drummer turned audio engineer Jim Marshall, and they proved perfect for his needs. Along with the Stratocaster, the Marshall stack and amplifiers were crucial in shaping his heavily overdriven sound, enabling him to master the use of feedback as a musical effect, and he created a "definitive vocabulary for rock guitar".[232]

Hendrix most likely first heard a wah-wah pedal used with an electric guitar in Cream's "Tales of Brave Ulysses", released in May 1967.[233] In July, while playing gigs at the Scene club in New York City, Hendrix met Frank Zappa, whose Mothers of Invention were playing the adjacent Garrick Theater. Hendrix immediately became fascinated by Zappa's use of a wah-wah pedal and Hendrix used one later that evening while recording overdubs in a studio.[234]

Although Hendrix typically used the Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face and a Vox wah-wah pedal,[235] he also experimented with other guitar effects. Hendrix enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with electronics enthusiast Roger Mayer, who first introduced Hendrix to the Octavia, an octave doubling effect unit, in December 1966.[236] The two worked together until Hendrix's death in 1970.[236] The Japanese-made Uni-Vibe, designed to simulate the modulation effects of the rotating Leslie speaker, provided a rich phasing sound with a speed control pedal, and is heard during Hendrix's Woodstock performance and the Band of Gypsys track "Machine Gun", which highlights use of the Uni-Vibe, Octavia and Fuzz Face.[237] His signal flow for live performance involved first plugging his guitar into a Vox Wah-Wah pedal, then into an Arbiter Fuzz Face, and then into a Uni-Vibe, before connecting to a Marshall amplifier.[238]

Legacy

Musical

He changed everything. What don't we owe Jimi Hendrix? For his monumental rebooting of guitar culture "standards of tone", technique, gear, signal processing, rhythm playing, soloing, stage presence, chord voicings, charisma, fashion, and composition? ... He is guitar hero number one." [239]

—Guitar Player, May 2012

His Rock and Roll Hall of Fame biography states: "Jimi Hendrix was arguably the greatest instrumentalist in the history of rock music. Hendrix expanded the range and vocabulary of the electric guitar into areas no musician had ever ventured before. His boundless drive, technical ability and creative application of such effects as wah-wah and distortion forever transformed the sound of rock and roll."[240] Musicologist Andy Aledort described Hendrix as "one of the most creative musicians of all time."[241]

Instrumental in developing the previously undesirable technique of guitar amplifier feedback, Hendrix favored overdriven amplifiers with high volume, gain and treble.[99] He helped to popularize use of the wah-wah pedal in mainstream rock, which he often used to deliver tonal exaggerations in his solos, particularly with high bends, complex guitar playing,[242] and use of legato.[243][244][245][246] On most of his recordings, Hendrix rejected the standard barre chord fretting technique in favor of fretting the low 6th string root notes with his thumb.[247] He pioneered experimentation with stereophonic phasing effects in rock music recordings.[248] Rolling Stone comments: "Hendrix pioneered the use of the instrument as an electronic sound source. Players before him had experimented with feedback and distortion, but Hendrix turned those effects and others into a controlled, fluid vocabulary every bit as personal as the blues with which he began."[249] Hendrix also played keyboard instruments on several recordings, including piano on "Are You Experienced?", "Spanish Castle Magic" and "Crosstown Traffic", and harpsichord on "Bold as Love" and "Burning of the Midnight Lamp".[250]

Hendrix synthesized numerous genres in creating his musical voice and his guitar style, which would later be abundantly imitated by others. Despite his hectic touring schedule and notorious perfectionism, he was a prolific recording artist and left behind numerous unreleased recordings.[251] His profound impact on popular music established a sonically heavy yet technically proficient style, significantly furthering the development of hard rock and paving the way for heavy metal. His music has influenced funk and the development of funk rock particularly through guitarists Ernie Isley of the Isley Brothers and Eddie Hazel of Funkadelic; Prince; John Frusciante, former member of the Red Hot Chili Peppers; and Jesse Johnson of the Time. Hendrix's influence also extends to many hip hop artists, including Questlove, Chuck D of Public Enemy, Ice-T, El-P and Wyclef Jean. Miles Davis was also deeply impressed by Hendrix and compared his improvisational skills with those of saxophonist John Coltrane.[252] Davis would later request that guitarists in his bands emulate Hendrix.[253] His guitar style also had significant influence upon Texas guitar legend Stevie Ray Vaughan,[254] Metallica's Kirk Hammett and Pearl Jam's Mike McCready. Hendrix's influence is also evident in the musical styles of many prominent bassists such as Stanley Clarke,[255] Jaco Pastorius,[256] Billy Sheehan,[257] and Les Claypool.[258]

His career and death grouped him with Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison and Brian Jones as one of the 27 Club, a group including 1960s rock performers who suffered drug-related deaths at the age of 27 within a two-year period, leaving legacies in death that have eclipsed the popularity and influence they experienced during their lifetimes.[259]

- Electric church

"Electric Church" was Hendrix's quasi-spiritual belief that electric music brings out emotions and creative ideas in people, and encourages spirituality. On The Dick Cavett Show in 1969, Hendrix said that he designed his music so that it would be able to go "inside the soul of the person, and awaken some kind of thing inside, because there are so many sleeping people". Promoting his third album Electric Ladyland, Hendrix said "the influence the psychedelics have on one is truly amazing, and I only wish more people appreciated this belief and genre". When asked why he didn't name the album "Electric Church" instead of "Electric Ladyland", Hendrix said some women were "electric too".[260]

Fashion

Hendrix was well known for his flamboyant wardrobe and his Dylan-esque hairstyle; a set of hair curlers was one of the few possessions that he took with him to England in 1966.[261] Soon after his first advance check arrived, Hendrix took to the streets of London in search of clothing at famous boutiques such as I Was Lord Kitchener's Valet and Granny Takes a Trip; both of which specialized in vintage fashion.[262] He purchased at least two army dress uniform jackets including a Crimean War-era Royal Hussars regimental coat, or pelisse, adorned with tasseled ropes.[263]

With their mutton-chop sideburns, droopy moustaches and flowing hair, English rock stars were effectively spoofing the Victorian officer class whose finery they donned. But a grinning, crazy-haired Hendrix in hussar's jacket suggested something else entirely—a redskin brave showing off the spoils of a paleface scalp, perhaps, or a negro "buffalo soldier" fighting on the side of the anti-slavery Yankee forces in the US Civil War.[264] —Neil Spencer, Editor, NME (1978–1985)

A group of policemen once ordered Hendrix to remove his Royal Veterinary Corps dress jacket, stating that it was an offense to any soldier who might have died while wearing it.[265] Hendrix, who had researched the history of the jacket, explained that it had been worn by those men who tended the donkeys, not soldiers who fought in battle. The police insisted that he remove the jacket and Hendrix temporarily obliged, putting the jacket back on once they had left.[265]

The James Marshall Hendrix Foundation

In 1988, Jimi's father Al and his brother Leon commissioned the non-profit charity, the James Marshall Hendrix Foundation, based in Renton, Washington.[266] According to Leon, the goal of the foundation was to "inspire and support creativity and understanding in the community, especially with young children."[267] The foundation sought to raise money for music and art programs while promoting diversity.[267] In August 2006, Leon asked a childhood friend of Jimi's – James Williams, to take control of the Foundation.[268]

Recognition and awards

In 1967, readers of Melody Maker voted Hendrix the Pop Musician of the Year.[269] In 1968, Billboard named him the Artist of the Year and Rolling Stone declared him the Performer of the Year.[269] Also in 1968, the City of Seattle gave Hendrix the Keys to the City.[270] Disc & Music Echo newspaper honored Hendrix with the World Top Musician of 1969 and in 1970, Guitar Player magazine called him the Rock Guitarist of the Year.[271]

Rolling Stone ranked his three non-posthumous studio albums, Are You Experienced (1967), Axis: Bold as Love (1967) and Electric Ladyland (1968) among the 500 Greatest Albums of All Time.[272] They ranked Hendrix number one on their list of the 100 greatest guitarists of all time, and number six on their list of the 100 greatest artists of all time.[273] Guitar World's readers voted six of Hendrix's solos among the top 100 Greatest Guitar Solos of All Time: "Purple Haze" (70), "The Star-Spangled Banner" (52; live version from Live at Woodstock), "Machine Gun" (32; live version from Band of Gypsys), "Little Wing" (18), "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)" (11) and "All Along the Watchtower" (5).[274] Rolling Stone placed seven of his recordings in their list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time: "Purple Haze" (17), "All Along the Watchtower" (47) "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)" (102), "Foxy Lady" (153), "Hey Joe" (201), "Little Wing" (366), and "The Wind Cries Mary" (379).[275] Additionally, they included three of Hendrix's songs in their list of the 100 Greatest Guitar Songs of All Time: "Purple Haze" (2), "Voodoo Child" (12), and "Machine Gun" (49).[276]

Hendrix was the recipient of several prestigious rock music awards during his lifetime and posthumously. The Jimi Hendrix Experience was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1992, and the UK Music Hall of Fame in 2005.[277] A star for Hendrix on the Hollywood Walk of Fame was dedicated on November 14, 1991, at 6627 Hollywood Boulevard.[278][279] In 1999, readers of Rolling Stone and Guitar World ranked Hendrix among the most important musicians of the 20th century.[280] In 2005, his debut album, Are You Experienced, was one of 50 recordings added that year to the United States National Recording Registry in the Library of Congress, "[to] be preserved for all time ... [as] part of the nation's audio legacy."[281]

The English Heritage blue plaque that identifies his former residence at 23 Brook Street, London, one door down from the former residence of George Frideric Handel, was the first the organization ever granted to a pop star.[282] A memorial statue of Hendrix playing a Stratocaster stands near the corner of Broadway and Pine Streets in Seattle. In May 2006, the city renamed a park near its Central District in his honor.[283]

| Year | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1983 | Lifetime Achievement[269] | Guitar Player |

| 1992 | Lifetime Achievement Award[284] | Grammy |

| 1999 | Are you Experienced? (Reprise, 1967)*[285] | Grammy Hall of Fame (Rock, Album) |

| 1999 | Electric Ladyland (Reprise, 1968)[285] | Grammy Hall of Fame (Rock, Album) |

| 2000 | "Purple Haze" (Reprise, 1967)*[285] | Grammy Hall of Fame (Rock, Single) |

| 2001 | "All Along the Watchtower" (Reprise, 1968)*[285] | Grammy Hall of Fame (Rock, Single) |

| 2005 | Are you Experienced?[281] | National Recording Registry, Library of Congress |

| 2006 | Axis: Bold as Love (Reprise, 1968)*[285] | Grammy Hall of Fame (Rock, Album) |

| 2009 | "The Star-Spangled Banner" (Cotillion, 1970)[285] | Grammy Hall of Fame (Rock, Track) |

Asterisk in the table indicates the award was for the Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Discography

|

|

Notes

- ^ Hendrix's paternal grandmother, Zenora "Nora" Rose Moore was a former vaudeville dancer who moved to Vancouver, Canada, from Tennessee after meeting her husband, former special police officer Bertram Philander Ross Hendrix, on the Dixieland circuit.[2] Nora shared a love for theatrical clothing and adornment, music, and performance with Hendrix. She also imbued him with the stories, rituals and music that had been part of her Afro-Cherokee heritage and her former life on the stage. Along with his attendance at black Pentecostal church services, writers have suggested these experiences may later have informed his thinking about the connections between emotions, spirituality and music.[3]

- ^ Authors Harry Shapiro and Caesar Glebbeek speculate that the change from Johnny to James may have been a response to Al's knowledge of an affair Lucille had with a man who called himself John Williams.[8] As a young child, friends and family called Hendrix "Buster". His brother Leon claims that Jimi chose the nickname after his hero Buster Crabbe, of Flash Gordon and Buck Rogers fame.[9]

- ^ Al Hendrix completed his basic training at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.[10] He spent most of his time in the service in the South Pacific Theater, in Fiji.[11]

- ^ In 1967, Hendrix revealed his feelings in regard to his mother's death during a survey he took for the UK publication, New Musical Express. Hendrix stated: "Personal ambition: Have my own style of music. See my mother again."[24]

- ^ According to Hendrix cousin, Diane Hendrix, in August 1956, when Jimi stayed with her family, he put on shows for her, using a broom to mimic a guitar while listening to Elvis Presley records.[25]

- ^ Hendrix saw Presley perform in Seattle on September 1, 1957.[28]

- ^ In the late 1960s, after he had become famous, Hendrix told reporters that racist faculty expelled him from Garfield for holding hands with a white girlfriend during study hall. Principal Frank Hanawalt says that it was due to poor grades and attendance problems.[36] The school had a relatively even ethnic mix of African, European, and Asian-Americans.[37]

- ^ According to authors Steven Roby and Brad Schreiber: "It has been erroneously reported that Captain John Halbert, a medical officer, recommended that Jimi be discharged primarily for admitting to having homosexual desires for an unnamed soldier."[50] However, in the National Personnel Records Center, which contains 98 pages documenting Hendrix's army service, including his numerous infractions, the word "homosexual" is not mentioned.[50]

- ^ The Allen twins performed as backup singers under the name Ghetto Fighters on Hendrix's song "Freedom".[60]

- ^ In March 1964, Hendrix provided guitar instrumentation for the Don Covay song, "Mercy Mercy". Issued by Rosemart Records and distributed by Atlantic, the track reached number 35 on the Billboard chart.[63]

- ^ During a stop in Los Angeles in early 1965, he played a session for Rosa Lee Brooks on her single "My Diary".[65]

- ^ Three other songs were recorded during the sessions, "Dancin' All Over the World", "You Better Stop", and "Every Time I Think About You", but Vee Jay did not release them at the time due to their poor quality.[67]

- ^ Several songs and demos from the Knight recording sessions were later marketed as "Jimi Hendrix" recordings after he had become famous.[74]

- ^ As with the King Curtis recordings, backing tracks and alternate takes for the Youngblood sessions would be overdubbed and otherwise manipulated to create many "new" tracks.[79] Many Youngblood tracks without any Hendrix involvement would later be marketed as "Jimi Hendrix" recordings.[77]

- ^ So as to differentiate them in the band, Hendrix dubbed Wolfe "Randy California" and Palmer "Randy Texas".[81] Randy California later co-founded the band Spirit with his stepfather, drummer Ed Cassidy.[82]

- ^ Singer-guitarist Ellen McIlwaine and guitarist Jeff Baxter also briefly worked with Hendrix during this period.[84]

- ^ Etchingham later wrote an autobiographical book about their relationship and the London music scene during the 1960s.[90]

- ^ This guitar has now been identified as the guitar acquired and later restored by Frank Zappa. He used it to record his album Zoot Allures (1971). When Zappa's son, Dweezil Zappa, found the guitar some twenty years later, Zappa gave it to him.[104]

- ^ When Track records sent the master tapes for "Purple Haze" to Reprise for remastering, they wrote the following words on the tape box: "Deliberate distortion. Do not correct."[108]

- ^ The original version of the LP contained none of the previously released singles or their B-sides.[110]

- ^ The US and Canadian versions of Are You Experienced featured a new cover by Karl Ferris and a new song list, with Reprise removing "Red House", "Remember" and "Can You See Me" to make room for the first three single A-sides omitted from the UK release: "Hey Joe", "Purple Haze", and "The Wind Cries Mary".[114] "Red House" is the only original twelve-bar blues written by Hendrix.[114]

- ^ As with their previous LP, the band had to schedule recording sessions in between performances.[124]

- ^ In March 1968, Jim Morrison of the Doors joined Hendrix onstage at the Scene Club in New York.[141]

- ^ In 2010, when a federal court of appeals decided on whether online sharing of a music recording constituted a performance, they cited Hendrix in their decision stating: "Hendrix memorably (or not, depending on one's sensibility) offered a 'rendition' of the Star-Spangled Banner at Woodstock when he performed it aloud in 1969".[159]

- ^ According to authors Scott Schinder and Andy Schwartz, as many as 500,000 people watched Hendrix perform at the concert.[172]

- ^ Many of Hendrix's personal items, tapes, and many pages of lyrics and poems are now in the hands of private collectors and have attracted considerable sums at the occasional auctions. These materials surfaced after two employees, under the instructions of Mike Jeffery, removed items from Hendrix's Greenwich Village apartment following his death.[210]

- ^ While Hendrix had previously owned a 1967 Flying V that he hand-painted in a psychedelic design, the Flying V used at the Isle of Wight was a unique custom left-handed guitar with gold plated hardware, a bound fingerboard and "split-diamond" fret markers that were not found on other 1960s-era Flying Vs.[225]

Citations

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, pp. 5–6, 13.

- ^ Hendrix, Janie L. "The Blood of Entertainers: The Life and Times of Jimi Hendrix's Paternal Grandparents". Blackpast.org. Retrieved November 15, 2012.

- ^ Whitaker 2011, pp. 377–385.

- ^ Hendrix 1999, p. 10: (primary source); Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, pp. 5–7: (secondary source).

- ^ Hendrix 1999, p. 10: Jimi's father's full name; Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, pp. 8–9: Al Hendrix' birthdate; Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, pp. 746–747: Hendrix family tree.

- ^ Hendrix 1999, p. 32: Al and Lucille meeting at a dance in 1941; Hendrix 1999, p. 37: Al and Lucille married in 1942.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 20: Al went to war three days after the wedding. (secondary source); Hendrix 1999, p. 37: Al went to war three days after the wedding. (primary source).

- ^ a b Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, pp. 13–19.

- ^ Hendrix & Mitchell 2012, p. 10: (primary source); Roby & Schreiber 2010, pp. xiii, 3: (secondary source).

- ^ a b Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, p. 13.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 23.

- ^ Cross 2005, pp. 22–25.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Lawrence 2005, p. 368.

- ^ Cross 2005, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 2.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Black 1999, p. 11: Leon's birthdate; Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 2: Leon, in and out of foster care.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Cross 2005, pp. 32, 179, 308.

- ^ Cross 2005, pp. 50, 127.

- ^ Stubbs 2003, p. 140.

- ^ a b Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 4.

- ^ a b c Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 5.

- ^ Black 1999, pp. 16–18.

- ^ Hendrix & Mitchell 2012, pp. 56–58.

- ^ Black 1999, pp. 16–18: Hendrix playing along with "Hound Dog" (secondary source); Hendrix 1999, p. 100: Hendrix playing along with Presley's version of "Hound Dog" (primary source); Hendrix & Mitchell 2012, p. 59: Hendrix playing along with Presley songs (primary source).

- ^ Hendrix & McDermott 2007, p. 9: Hendrix seeing Presley perform; Black 1999, p. 18: the date Hendrix saw Presley perform.

- ^ Heatley 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Hendrix 1999, p. 126: (primary source); Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 6: (secondary source).

- ^ Hendrix 1999, p. 113: (primary source); Heatley 2009, p. 20: (secondary source).

- ^ a b Heatley 2009, p. 19.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 67.

- ^ Heatley 2009, p. 28.

- ^ Lawrence 2005, pp. 17–19: Hendrix did not graduate from James A. Garfield High School; Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, p. 694: Hendrix completed his studies at Washington Middle School.

- ^ Cross 2005, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Lawrence 2005, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Hendrix & Mitchell 2012, p. 95: Hendrix choosing the Army over jail; Cross 2005, p. 84: Hendrix' enlistment date; Shadwick 2003, p. 35: Hendrix was twice caught in stolen cars.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, pp. 13–14: Hendrix completed eight weeks of basic training at Fort Ord, California; Shadwick 2003, pp. 37–38: the Army stationed Hendrix at Fort Campbell, Kentucky.

- ^ a b c Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Heatley 2009, p. 26; Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, p. 51.

- ^ Cross 2005, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 92.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, pp. 18–25.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 26.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 94: Hendrix claimed he had received a medical discharge; Roby 2002, p. 15: Hendrix's dislike of the Army.

- ^ a b Roby & Schreiber 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Cross 2005, pp. 92–97.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 97.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, p. 66.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Roby & Schreiber 2010, pp. 225–226.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, p. 50.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, pp. 59–61.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, p. 537; Doggett 2004, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Hendrix & McDermott 2007, p. 13.

- ^ a b McDermott 2009, p. 10.

- ^ George-Warren 2001, p. 217: for the peak chart position of "Mercy Mercy"; McDermott 2009, p. 10: for Hendrix recording with Covay in March 1964.

- ^ a b McDermott 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, p. 55.

- ^ McDermott 2009, p. 12: recording with Richard; Shadwick 2003, pp. 56–57: "I Don't Know What You Got (But It's Got Me)" recorded in Los Angeles.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, p. 57.

- ^ Shadwick 2003, pp. 56–60.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, p. 571; Shadwick 2003, pp. 60–61.

- ^ Shapiro & Glebbeek 1995, p. 95.

- ^ Cross 2005, p. 120.