Marlon Brando: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

well, 193.150.27.251 (nerd in Warrington Local Govt) if that was a test to see how long your rubbish edit would last -- there's yer answer, about 2 mins |

||

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

An enduring [[cultural icon]], Brando became a box office star during the 1950s, during which time he racked up five Oscar nominations as Best Actor, along with three consecutive wins of the [[BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role]]. He initially gained popularity for recreating the role as [[Stanley Kowalski]] in ''[[A Streetcar Named Desire (1951 film)|A Streetcar Named Desire]]'' (1951), a [[Tennessee Williams]] play that had established him as a [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] star during its 1947-49 stage run; and for his Academy Award-winning performance as Terry Malloy in ''[[On the Waterfront]]'' (1954), as well as for his iconic portrayal of the rebel motorcycle gang leader Johnny Strabler in ''[[The Wild One]]'' (1953), which is considered to be one of the most famous images in [[pop culture]]. Brando was also nominated for the Oscar for playing [[Emiliano Zapata]] in ''[[Viva Zapata!]]'' (1952); [[Mark Antony]] in [[Joseph L. Mankiewicz]]'s 1953 [[Julius Caesar (1953 film)|film adaptation]] of [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]]'s ''[[Julius Caesar (play)|Julius Caesar]]''; and as Air Force Major Lloyd Gruver in ''[[Sayonara]]'' (1957), [[Joshua Logan]]'s adaption of [[James Michener]]'s 1954 novel. Brando made the [[Top Ten Money Making Stars Poll|Top Ten Money Making Stars]], as ranked by Quigley Publications' annual survey of movie exhibitors, three times in the decade, coming in at number 10 in 1954, number 6 in 1955, and number 4 in 1958. |

An enduring [[cultural icon]], Brando became a box office star during the 1950s, during which time he racked up five Oscar nominations as Best Actor, along with three consecutive wins of the [[BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role]]. He initially gained popularity for recreating the role as [[Stanley Kowalski]] in ''[[A Streetcar Named Desire (1951 film)|A Streetcar Named Desire]]'' (1951), a [[Tennessee Williams]] play that had established him as a [[Broadway theatre|Broadway]] star during its 1947-49 stage run; and for his Academy Award-winning performance as Terry Malloy in ''[[On the Waterfront]]'' (1954), as well as for his iconic portrayal of the rebel motorcycle gang leader Johnny Strabler in ''[[The Wild One]]'' (1953), which is considered to be one of the most famous images in [[pop culture]]. Brando was also nominated for the Oscar for playing [[Emiliano Zapata]] in ''[[Viva Zapata!]]'' (1952); [[Mark Antony]] in [[Joseph L. Mankiewicz]]'s 1953 [[Julius Caesar (1953 film)|film adaptation]] of [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]]'s ''[[Julius Caesar (play)|Julius Caesar]]''; and as Air Force Major Lloyd Gruver in ''[[Sayonara]]'' (1957), [[Joshua Logan]]'s adaption of [[James Michener]]'s 1954 novel. Brando made the [[Top Ten Money Making Stars Poll|Top Ten Money Making Stars]], as ranked by Quigley Publications' annual survey of movie exhibitors, three times in the decade, coming in at number 10 in 1954, number 6 in 1955, and number 4 in 1958. |

||

Brando directed and starred in the [[cult film|cult]] western film ''[[One-Eyed |

Brando directed and starred in the [[cult film|cult]] western film ''[[One-Eyed Jacks]]'' which was released in 1961, after which he delivered a series of box office failures beginning with the non-success of the [[Mutiny on the Bounty (1962 film)|1962 film adaptation]] of ''[[Mutiny on the Bounty (novel)|Mutiny on the Bounty]]''. The 1960s proved to be a fallow decade for Brando, and after 10 years in which he did not appear in a commercially successful movie, he won his second Academy Award for playing [[Vito Corleone]] in [[Francis Ford Coppola]]'s ''[[The Godfather]]'' (1972), a role critics consider among his greatest. The movie, which became the most commercially successful film of all time when it was released — along with his Oscar-nominated performance as Paul in ''[[Last Tango in Paris]]'' (1972), another smash hit — revitalized Brando's career and reestablished him in the ranks of top box office stars, placing him at number 6 and number 10 in Top 10 Money Making Stars poll in 1972 and 1973, respectively. |

||

Brando failed to capitalize on the momentum of his revitalized career, taking a long hiatus before appearing in ''[[The Missouri Breaks]]'' (1976), a box office bomb. Afterward, he was content to be a highly paid character actor in parts that were glorified [[Cameo appearance|cameos]] in ''[[Superman (film)|Superman]]'' (1978) and ''[[The Formula (1980 film)|The Formula]]'' (1980) before taking a nine-year break from motion pictures. According to the ''[[Guinness Book of World Records]]'', Brando was paid a record $3.7 million (${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|3700000|1977|r=0}}}} in today's funds{{inflation-fn|US}}) plus 11.75% of the gross profits for 13 days work playing [[Jor-El]] in ''Superman'', further adding to his mystique. He finished out the decade of the 1970s with his controversial performance as [[Walter E. Kurtz|Colonel Walter Kurtz]] in another Coppola film, ''[[Apocalypse Now]]'' (1979), a box office hit for which he was highly paid and that helped finance his career layoff during the 1980s. |

Brando failed to capitalize on the momentum of his revitalized career, taking a long hiatus before appearing in ''[[The Missouri Breaks]]'' (1976), a box office bomb. Afterward, he was content to be a highly paid character actor in parts that were glorified [[Cameo appearance|cameos]] in ''[[Superman (film)|Superman]]'' (1978) and ''[[The Formula (1980 film)|The Formula]]'' (1980) before taking a nine-year break from motion pictures. According to the ''[[Guinness Book of World Records]]'', Brando was paid a record $3.7 million (${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|3700000|1977|r=0}}}} in today's funds{{inflation-fn|US}}) plus 11.75% of the gross profits for 13 days work playing [[Jor-El]] in ''Superman'', further adding to his mystique. He finished out the decade of the 1970s with his controversial performance as [[Walter E. Kurtz|Colonel Walter Kurtz]] in another Coppola film, ''[[Apocalypse Now]]'' (1979), a box office hit for which he was highly paid and that helped finance his career layoff during the 1980s. |

||

Revision as of 14:07, 7 May 2013

Marlon Brando | |

|---|---|

| File:Marlon Brando - The Wild One.jpg | |

| Born | Marlon Brando, Jr. April 3, 1924 Omaha, Nebraska, U.S. |

| Died | July 1, 2004 (aged 80) Westwood, Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Respiratory failure |

| Education | The New School |

| Alma mater | Actors Studio |

| Years active | 1944–1980, 1989–2004 |

| Height | 5 ft 8 in (1.73 m) |

| Spouse(s) | Anna Kashfi (1957–59) Movita Castaneda (1960–62) Tarita Teriipia (1962–72) |

| Children | 15, including: Christian Brando (deceased) Cheyenne Brando (deceased) Stephen Blackehart |

| Parent(s) | Marlon Brando, Sr. Dodie Brando |

| Awards | Template:Infobox comedian awards |

| Website | www |

Marlon Brando, Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American screen and stage actor. He is widely regarded as having had a significant impact on the art of film acting.

While he became notorious for his "mumbling" diction and exuding a raw animal magnetism,[1] his mercurial performances were nonetheless highly regarded, and he is widely considered as one of the greatest and most influential actors of the 20th century.[2][3] Director Martin Scorsese said of him, "He is the marker. There's 'before Brando' and 'after Brando'."[4] Actor Jack Nicholson once said, "When Marlon dies, everybody moves up one."[5]

An enduring cultural icon, Brando became a box office star during the 1950s, during which time he racked up five Oscar nominations as Best Actor, along with three consecutive wins of the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role. He initially gained popularity for recreating the role as Stanley Kowalski in A Streetcar Named Desire (1951), a Tennessee Williams play that had established him as a Broadway star during its 1947-49 stage run; and for his Academy Award-winning performance as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront (1954), as well as for his iconic portrayal of the rebel motorcycle gang leader Johnny Strabler in The Wild One (1953), which is considered to be one of the most famous images in pop culture. Brando was also nominated for the Oscar for playing Emiliano Zapata in Viva Zapata! (1952); Mark Antony in Joseph L. Mankiewicz's 1953 film adaptation of Shakespeare's Julius Caesar; and as Air Force Major Lloyd Gruver in Sayonara (1957), Joshua Logan's adaption of James Michener's 1954 novel. Brando made the Top Ten Money Making Stars, as ranked by Quigley Publications' annual survey of movie exhibitors, three times in the decade, coming in at number 10 in 1954, number 6 in 1955, and number 4 in 1958.

Brando directed and starred in the cult western film One-Eyed Jacks which was released in 1961, after which he delivered a series of box office failures beginning with the non-success of the 1962 film adaptation of Mutiny on the Bounty. The 1960s proved to be a fallow decade for Brando, and after 10 years in which he did not appear in a commercially successful movie, he won his second Academy Award for playing Vito Corleone in Francis Ford Coppola's The Godfather (1972), a role critics consider among his greatest. The movie, which became the most commercially successful film of all time when it was released — along with his Oscar-nominated performance as Paul in Last Tango in Paris (1972), another smash hit — revitalized Brando's career and reestablished him in the ranks of top box office stars, placing him at number 6 and number 10 in Top 10 Money Making Stars poll in 1972 and 1973, respectively.

Brando failed to capitalize on the momentum of his revitalized career, taking a long hiatus before appearing in The Missouri Breaks (1976), a box office bomb. Afterward, he was content to be a highly paid character actor in parts that were glorified cameos in Superman (1978) and The Formula (1980) before taking a nine-year break from motion pictures. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, Brando was paid a record $3.7 million ($18,603,624 in today's funds[6]) plus 11.75% of the gross profits for 13 days work playing Jor-El in Superman, further adding to his mystique. He finished out the decade of the 1970s with his controversial performance as Colonel Walter Kurtz in another Coppola film, Apocalypse Now (1979), a box office hit for which he was highly paid and that helped finance his career layoff during the 1980s.

Brando was also an activist, supporting many issues, notably the African-American Civil Rights Movement and various American Indian Movements.

Brando was ranked by the American Film Institute as the fourth greatest screen legend among male movie stars whose screen debuts occurred in or before 1950. Considered to be one of the most important actors in American cinema,[7][8] Brando was one of only three professional actors, along with Charlie Chaplin and Marilyn Monroe, named by Time magazine as one of its 100 Persons of the Century in 1999.[9] He died on July 1, 2004 of Respiratory failure at 80.

Early life

Marlon Brando was born in Omaha, Nebraska, to Marlon Brando, Sr., a pesticide and chemical feed manufacturer, and his wife, Dorothy Julia (née Pennebaker).[2] His parents moved to Evanston, Illinois, but separated when he was 11 years old. His mother took her three children: Jocelyn (1919–2005), Frances (1922–1994), and Marlon, to live with her mother in Santa Ana, California.[2] In 1937, Brando's parents reconciled and moved together to Libertyville, Illinois, a north suburb of Chicago.[2]

Brando's ancestry included German, Dutch, English, and Irish.[10][11][12] His patrilineal ancestor, Johann Wilhelm Brandau, was a German immigrant to New York in the early 1700s.[13] Brando was raised a Christian Scientist.[14] His paternal grandmother, Marie Holloway, abandoned her family when Marlon Brando, Sr., was five years old. She used the money her husband Eugene sent her to support her gambling and alcoholism.[10]

Marlon Brando, Sr., was a talented amateur photographer. His wife, known as Dodie, was unconventional and talented, having been an actress.[15][16] She smoked, wore trousers, and drove cars, unusual for women at the time. However, she was an alcoholic and often had to be brought home from Chicago bars by her husband; she finally joined Alcoholics Anonymous. In addition to acting, Dodie Brando was a theater administrator. She helped Henry Fonda begin his acting career and fueled her son Marlon's interest in stage acting. However, Brando was closer to his maternal grandmother, Bessie Gahan Pennebaker Meyers, than to his mother. Widowed while young, Meyers worked as a secretary and later as a Christian Science practitioner. Her father, Myles Gahan, was a doctor from Ireland; her mother, Julia Watts, was from England.[17]

Brando was a mimic from early childhood and developed an ability to absorb the mannerisms of people he played and display them dramatically while staying in character. His sister Jocelyn Brando was the first to pursue an acting career, going to study at the American Academy of Dramatic Art. She appeared on Broadway, then movies and television. Brando's sister Frances left college in California to study art in New York. Brando soon followed her.

Brando had been held back a year in school and was later expelled from Libertyville High School for riding his motorcycle through the corridors.[18] He was sent to Shattuck Military Academy, where his father had studied before him. Brando excelled at theatre and did well in the school. In his final year (1943), he was put on probation for being insubordinate to a visiting army colonel during maneuvers. He was confined to his room, but sneaked into town, and was caught. The faculty voted to expel him, though he was supported by the students, who thought expulsion was too harsh. He was invited back for the following year, but decided instead to drop out of high school.[19]

Brando worked as a ditch-digger as a summer job arranged by his father. He then attempted to join the army, but at his induction physical it was discovered that a football injury that he had sustained at Shattuck had left him with a trick knee. He was therefore classified as a 4-F, and not inducted into the army.[10] He then decided to follow his sisters to New York. His father supported him for six months, then offered to help him find a job as a salesman. However, Brando left to study at the American Theatre Wing Professional School, part of the Dramatic Workshop of The New School with the influential German director Erwin Piscator and at the Actors Studio.

Despite being commonly regarded as a Method actor, Brando saw himself as anything but in that image. He claimed to have abhorred Lee Strasberg's teachings: "After I had some success, Lee Strasberg tried to take credit for teaching me how to act. He never taught me anything. He would have claimed credit for the sun and the moon if he believed he could get away with it. He was an ambitious, selfish man who exploited the people who attended the Actors Studio and tried to project himself as an acting oracle and guru. Some people worshipped him, but I never knew why ... Strasberg never taught me acting." [20]

Brando was an avid student and proponent of Stella Adler, from whom he learned the techniques of the Stanislavski System. There is a story in which Adler spoke about teaching Brando, saying that she had instructed the class to act like chickens, then added that a nuclear bomb was about to fall on them. Most of the class clucked and ran around wildly, but Brando sat calmly and pretended to lay an egg. Asked by Adler why he had chosen to react this way, he said, "I'm a chicken - What do I know about bombs?"[21]

Career

Early work

Brando used his Stanislavski System skills for his first summer-stock roles in Sayville, New York, on Long Island. His behavior got him kicked out of the cast of the New School's production in Sayville, but he was discovered in a locally produced play there and then made it to Broadway in the bittersweet drama I Remember Mama in 1944. Critics voted him "Broadway's Most Promising Actor" for his role as an anguished veteran in Truckline Café, although the play was a commercial failure. In 1946, he appeared on Broadway as the young hero in the political drama A Flag is Born, refusing to accept wages above the Actor's Equity rate because of his commitment to the cause of Israeli independence.[22][23] In that same year, Brando played the role of Marchbanks with Katharine Cornell in her production's revival of Candida, one of her signature roles.[24] Cornell also cast him as The Messenger in her production of Jean Anouilh's Antigone that same year. Brando achieved stardom, however, as Stanley Kowalski in Tennessee Williams's 1947 play A Streetcar Named Desire, directed by Elia Kazan. Brando sought out that role,[25] driving out to Provincetown, Massachusetts, where Williams was spending the summer, to audition for the part. Williams recalled that he opened the screen door and knew, instantly, that he had his Stanley Kowalski. Brando actually based his portrayal of Kowalski on the boxer Rocky Graziano, whom he studied at a local gymnasium. Graziano was unaware of who Brando was and it was not until Brando gave him tickets for the production that he realised - "The curtain went up and on the stage is that son of a bitch from the gym, and he's playing me." [26]

In 1947, Brando was asked to do a screen test for Warner Brothers. The screen test used an early script for Rebel Without A Cause that bears no relation to the film eventually produced in 1955.[27] The screen test appears as an extra in the 2006 DVD release of A Streetcar Named Desire.

Brando's first screen role was as the bitter paraplegic veteran in The Men in 1950. He spent a month in bed at the Birmingham Army Hospital in Van Nuys to prepare for the role. By Brando's own account, it may have been because of this film that his draft status was changed from 4-F to 1-A. He had had an operation on the knee he had injured at Shattuck, and it was no longer physically debilitating enough to incur exclusion from the draft. When Brando reported to the induction center, he answered a questionnaire provided to him by saying his race was "human", his color was "Seasonal-oyster white to beige", and he told an Army doctor that he was psycho neurotic. When the draft board referred him to a psychiatrist, Brando explained how he had been expelled from military school and that he had severe problems with authority. Coincidentally, the psychiatrist knew a doctor friend of Brando, and Brando was able to avoid military service during the Korean War.[10]

Rise to fame

Brando brought his performance as Stanley Kowalski to the screen in Kazan's adaptation of Tennessee Williams's A Streetcar Named Desire, and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Actor for that role, and again in each of the next three years for his roles in Viva Zapata! in 1952, Julius Caesar in 1953 as Mark Antony, and On the Waterfront in 1954. These first five films of his career established him, as evidenced in his winning the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Leading Role in three consecutive years, 1951 to 1953.

In 1953, Brando also starred in The Wild One riding his own Triumph Thunderbird 6T motorcycle, which caused consternation to Triumph's importers, as the subject matter was rowdy motorcycle gangs taking over a small town. But the images of Brando posing with his Triumph motorcycle became iconic, even forming the basis of his wax dummy at Madame Tussauds.

Later that same year, Brando starred in Lee Falk's production of George Bernard Shaw's Arms and the Man in Boston. Falk was proud to tell people that Marlon Brando turned down an offer of $10,000 per week on Broadway, in favor of working on Falk's play in Boston. His Boston contract was less than $500 per week. It was the last time he ever acted in a stage play.

Brando won the Oscar for his role as Terry Malloy in On the Waterfront. For the famous I coulda' been a contender scene, he convinced Kazan that the scripted scene was unrealistic, and, with Rod Steiger, improvised the final product.

Brando then took a variety of roles in the 1950s: portraying Napoleon in Désirée, Sky Masterson in the musical Guys and Dolls; Sakini, a Japanese interpreter for the U.S. Army in postwar Japan in The Teahouse of the August Moon; as a United States Air Force officer in Sayonara, and a German officer in The Young Lions.

In the 1960s, Brando starred in films such as One-Eyed Jacks (1961), a western that was the only film he ever directed; Mutiny on the Bounty (1962), The Chase (1966), and Reflections in a Golden Eye (1967), portraying a repressed gay army officer. It was the type of performance that later led critic Stanley Crouch to write, "Brando's main achievement was to portray the taciturn but stoic gloom of those pulverized by circumstances."[28] He also played a guru in the sex farce Candy (1968). Burn! (1969), which Brando later claimed as his personal favorite, was a commercial failure. His career slowed down by the end of the decade as he gained a reputation for being difficult to work with.

The Godfather

Brando's performance as Vito Corleone or 'the Don' in 1972's The Godfather was a mid-career turning point. Director Francis Ford Coppola convinced Brando to submit to a "make-up" test, in which Brando did his own makeup (he used cotton balls to simulate the puffed-cheek look). Coppola was electrified by his characterization as the head of a crime family, but he had to fight the studio in order to cast the temperamental actor. Mario Puzo always imagined Brando as Corleone.[29] However, Paramount studio heads wanted to give the role to Danny Thomas in the hope that Thomas would have his own production company throw in its lot with Paramount. Thomas declined the role and urged the studio to cast Brando at the behest of Coppola and others who had witnessed the screen test.

Eventually, Charles Bluhdorn, the president of Paramount parent Gulf+Western, was won over to letting Brando have the role; when he saw the screen test, he asked in amazement, "What are we watching? Who is this old guinea?"

Brando won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance, but turned down the Oscar, becoming the second actor to refuse a Best Actor award (the first being George C. Scott for Patton). He boycotted the award ceremony, sending instead American Indian Rights activist Sacheen Littlefeather, who appeared in full Apache dress, to state Brando's reasons, which were based on his objection to the depiction of American Indians[30] by Hollywood and television.

The actor followed with Bernardo Bertolucci's 1972 film Last Tango in Paris, but the performance was overshadowed by an uproar over the sexual content of the film. Nonetheless, the Academy once again nominated Brando for Best Actor.

Brando was slated to reprise his role as Vito Corleone for the final scene of The Godfather Part II in 1974. However, he did not appear on the single day scheduled for the shoot due to a dispute with the studio and he was written out of the scene.

Later career

Brando portrayed Superman's father Jor-El in the 1978 film Superman. He agreed to the role only on assurance that he would be paid a large sum for what amounted to a small part, that he would not have to read the script beforehand and his lines would be displayed somewhere off-camera. It was revealed in a documentary contained in the 2001 DVD release of Superman that he was paid $3.7 million for two weeks of work.

Brando also filmed scenes for the movie's sequel, Superman II, but after producers refused to pay him the same percentage he received for the first movie, he denied them permission to use the footage. However, after Brando's death, the footage was reincorporated into the 2006 re-cut of the film, Superman II: The Richard Donner Cut.

Two years after Brando's death, he "reprised" the role of Jor-El in the 2006 "loose sequel" Superman Returns, in which both used and unused archive footage of him as Jor-El from the first two Superman films was remastered for a scene in the Fortress of Solitude, and Brando's voice-overs were used throughout the film.

Brando starred as Colonel Walter E. Kurtz in Francis Ford Coppola's Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now. He plays a highly decorated American Army Special Forces officer who goes renegade. He runs his own operations based in Cambodia and is feared by the US military as much as the Vietnamese. Brando was paid $1 million a week for his work.

Despite announcing his retirement from acting in 1980, Brando subsequently gave supporting performances in movies such as A Dry White Season (for which he was again nominated for an Oscar in 1989), The Freshman in 1990 and Don Juan DeMarco in 1995. In his last film, The Score (2001), he starred with Robert De Niro, who played Vito Corleone in The Godfather: Part II. Some later performances, such as the unique portrayal in The Island of Dr. Moreau (1996), resulted in some of the most uncomplimentary reviews of his career.

He conceived the idea of a novel called Fan-Tan with director Donald Cammell in 1979, which was not released until 2005.[31]

In 2004, Brando signed with Tunisian film director Ridha Behion and began pre-production on a project to be titled Brando and Brando. Up to a week before his death, he was working on the script in anticipation of a July/August 2004 start date.[32] Production was suspended in July 2004 following Brando's death, at which time Behi stated that he would continue the film as an homage to Brando,[33] with a new title of Citizen Brando.[34][35]

Personal life

Relationships and family

In Songs My Mother Taught Me, Brando claimed he met Marilyn Monroe at a party where she played piano, unnoticed by anybody else there, and they had an affair and maintained an intermittent relationship for many years, receiving a telephone call from her several days before she died. He also claimed numerous other romances, although he did not discuss his marriages, his wives, or his children in his autobiography.

Brando married actress Anna Kashfi in 1957. Kashfi was born in Calcutta and moved to Wales from India in 1947. She is said to have been the daughter of a Welsh steel worker of Irish descent, William O'Callaghan, who had been superintendent on the Indian State railways. However, in her book, Brando for Breakfast, she claimed that she really is half Indian and that the press incorrectly thought that her stepfather, O'Callaghan, was her real father. She said her real father was Indian and that she was the result of an "unregistered alliance" between her parents. Brando and Kashfi had a son, Christian Brando, on May 11, 1958; they divorced in 1959.

In 1960, Brando married Movita Castaneda, a Mexican-American actress seven years his senior; they were separated in 1962, and divorced in 1968. Castaneda had appeared in the first Mutiny on the Bounty film in 1935, some 27 years before the 1962 remake with Brando as Fletcher Christian. They had two children together: Miko Castaneda Brando (born 1961) and Rebecca Brando (born 1966).

Tahitian actress Tarita Teriipia, who played his love interest in Mutiny on the Bounty, became Brando's third wife on August 10, 1962. She was 20 years old, 18 years younger than Brando, who was reportedly delighted by her naiveté.[36] Because Teriipia was a native French speaker, Brando became fluent in the language and gave numerous interviews in French.[37][38] Teriipia became the mother of two of his children: Simon Teihotu Brando (born 1963) and Tarita Cheyenne Brando (born 1970). Brando also adopted Teriipia's daughters, Maimiti Brando (born 1977) and Raiatua Brando (born 1982). Brando and Teriipia divorced in July 1972.

Brando had a long-term relationship with his housekeeper Maria Christina Ruiz, by whom he had three children: Ninna Priscilla Brando (born May 13, 1989), Myles Jonathan Brando (born January 16, 1992), and Timothy Gahan Brando (born January 6, 1994). He had four more children by unidentified women: Stephen Blackehart (born 1967),[39][40] Michael Gilman (born 1967), who was adopted by Brando's longtime friend Sam Gilman, Dylan Brando (born 1968), and Angelique Brando. Brando also adopted Petra Brando-Corval (born 1972), the daughter of his assistant Caroline Barrett and novelist James Clavell.[41][42]

Brando's grandson Tuki Brando (born 1990), son of Cheyenne Brando, is a successful fashion model. His numerous grandchildren also include Michael Brando (born 1988), son of Christian Brando, Prudence Brando and Shane Brando, children of Miko C. Brando, the three children of Teihotu Brando and the children of Michael Gilman, among others.[43]

- Death of Dag Drollet

In May 1990, Dag Drollet, the Tahitian lover of Brando's daughter Cheyenne, died of a gunshot wound after a confrontation with Cheyenne's half-brother Christian at the family's hilltop home above Beverly Hills. Christian, then 31 years old, claimed he was drunk and the shooting was accidental. After heavily publicized pre-trial proceedings, Christian pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter and use of a gun. He was sentenced to 10 years in prison. Before the sentence, Brando delivered an hour of testimony, in which he said he and his former wife had failed Christian. He commented softly to members of the Drollet family: "I'm sorry... If I could trade places with Dag, I would. I'm prepared for the consequences." Afterward, Drollet's father, Jacques, said he thought Brando was acting and his son was "getting away with murder." The tragedy was compounded in 1995, when Cheyenne, suffering from lingering effects of a serious car accident and said to still be depressed over Drollet's death, committed suicide by hanging herself in Tahiti. Christian Brando died of pneumonia at age 49 on January 26, 2008.

Lifestyle

Brando earned a "bad boy" reputation for his public outbursts and antics. According to Los Angeles magazine, "Brando was rock and roll before anybody knew what rock and roll was".[44] His behavior during the filming of Mutiny on the Bounty (1962) seemed to bolster his reputation as a difficult star. He was blamed for a change in director and a runaway budget, though he disclaimed responsibility for either. On June 12, 1973, Brando broke paparazzo Ron Galella's jaw. Galella had followed Brando, who was accompanied by talk show host Dick Cavett, after a taping of The Dick Cavett Show in New York City. He reportedly paid a $40,000 out-of-court settlement and suffered an infected hand as a result. Galella wore a football helmet the next time he photographed Brando at a gala benefiting the American Indians Development Association.

Brando made the following comment about his sex life in an interview with Gary Carey, for his 1976 biography The Only Contender, "Homosexuality is so much in fashion it no longer makes news. Like a large number of men, I, too, have had homosexual experiences and I am not ashamed. I have never paid much attention to what people think about me. But if there is someone who is convinced that Jack Nicholson and I are lovers, may they continue to do so. I find it amusing."[45]

The filming of Mutiny on the Bounty affected Brando's life in a profound way, as he fell in love with Tahiti and its people. He bought a 12-island atoll, Tetiaroa, which he intended to make partly an environmental laboratory and partly a resort. Brando eventually had a now-closed hotel built on Tetiaroa, which went through many redesigns as a result of changes demanded by Brando over the years.[46] His son Simon is the only inhabitant of Tetiaroa. Brando was an active ham radio operator, with the call signs KE6PZH and FO5GJ (the latter from his island). He was listed in the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) records as Martin Brandeaux to preserve his privacy.[47][48]

Final years and death

Brando's notoriety, his troubled family life, and his obesity attracted more attention than his late acting career. He gained a great deal of weight in the 1980s and by the mid 1990s he weighed over 300 lbs. (136 kg) and suffered from diabetes. Like Orson Welles, he had a history of weight fluctuations through his career, attributed to his years of stress-related overeating followed by compensatory dieting. He also earned a reputation for being difficult on the set, often unwilling or unable to memorize his lines and less interested in taking direction than in confronting the film director with odd demands.

He also dabbled with some innovation in his last years. He had several patents issued in his name from the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, all of which involve a method of tensioning drum heads, in June 2002 – November 2004. For example, see U.S. patent 6,812,392 and its equivalents.

The actor was a longtime close friend of entertainer Michael Jackson and paid regular visits to his Neverland Ranch, resting there for weeks at a time. Brando also participated in the singer's two-day solo career 30th-anniversary celebration concerts in 2001, and starred in his 13-minute-long music video, "You Rock My World," in the same year. The actor's son, Miko, was Jackson's bodyguard and assistant for several years, and was a friend of the singer. He stated, "The last time my father left his house to go anywhere, to spend any kind of time... was with Michael Jackson. He loved it... He had a 24-hour chef, 24-hour security, 24-hour help, 24-hour kitchen, 24-hour maid service."[49] On Jackson's 30th anniversary concert, Brando gave a speech to the audience on humanitarian work which received a poor reaction from the audience and was unaired.

On July 1, 2004, Brando died of respiratory failure from pulmonary fibrosis with congestive heart failure at the UCLA Medical Center.[50] He left behind 13 children (two of his children, Cheyenne and Dylan Brando, had predeceased him) as well as over 30 grandchildren. The cause of death was intentionally withheld, and his lawyer cited privacy concerns. He also suffered from failing eyesight caused by diabetes and liver cancer.[51] Shortly before his death and despite needing an oxygen mask to breathe, he recorded his voice to appear in The Godfather: The Game, once again as Don Vito Corleone.

Karl Malden, Brando's fellow actor in A Streetcar Named Desire, On The Waterfront, and One-Eyed Jacks (the only film directed by Brando), talks in a documentary accompanying the DVD of A Streetcar Named Desire about a phone call he received from Brando shortly before Brando's death. A distressed Brando told Malden he kept falling over. Malden wanted to come over, but Brando put him off, telling him there was no point. Three weeks later, Brando was dead. Shortly before his death, he had apparently refused permission for tubes carrying oxygen to be inserted into his lungs, which, he was told, was the only way to prolong his life.

Brando was cremated, and his ashes were put in with those of his childhood friend Wally Cox and another longtime friend, Sam Gilman.[52] They were then scattered partly in Tahiti and partly in Death Valley.[53] In 2007, a 165-minute biopic of Brando, Brando: The Documentary, produced by Mike Medavoy (the executor of Brando's will) for Turner Classic Movies, was released.[54]

Politics

Civil rights

In 1946, Brando showed his dedication to the idea of a Jewish homeland by performing in Ben Hecht's Zionist play A Flag is Born. His involvement had an impact on three of the most contentious issues of the early postwar period: the fight to establish a Jewish state, the smuggling of Holocaust survivors to Israel, and the battle against racial segregation in the United States.

Brando attended some fundraisers for John F. Kennedy in the 1960 presidential election.

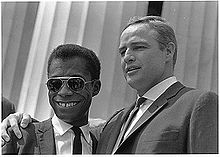

In August 1963, he participated in the March on Washington along with fellow celebrities Harry Belafonte, James Garner, Charlton Heston, Burt Lancaster, and Sidney Poitier.[55] Brando also, along with Paul Newman, participated in the freedom rides.

In the aftermath of the 1968 assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Brando made one of the strongest commitments to furthering King's work. Shortly after King's death, he announced that he was bowing out of the lead role of a major film (The Arrangement) which was about to begin production in order to devote himself to the civil rights movement. "I felt I’d better go find out where it is; what it is to be black in this country; what this rage is all about," Brando said on the late night ABC-TV talk show Joey Bishop Show.

Brando's participation in the African-American civil rights movement actually began well before King's death. In the early 1960s, he contributed thousands of dollars to both the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (S.C.L.C.) and to a scholarship fund established for the children of slain Mississippi N.A.A.C.P. leader Medgar Evers. By this time, Brando was already involved in films that carried messages about human rights: Sayonara, which addressed interracial romance, and The Ugly American, depicting the conduct of US officials abroad and its deleterious effect on the citizens of foreign countries. For a time, he was also donating money to the Black Panther Party and considered himself a friend of founder Bobby Seale.[56] However, he ended his financial support for the group over his perception of its increasing radicalization, specifically a passage in a Panther pamphlet put out by Eldridge Cleaver advocating indiscriminate violence, "for the Revolution."

At the 1973 Academy Awards ceremony, Brando refused to accept the Oscar for his performance in The Godfather. Sacheen Littlefeather represented him at the ceremony. She appeared in full Apache clothing and stated that owing to the "poor treatment of Native Americans in the film industry", Brando would not accept the award.[57] At this time, the 1973 standoff at Wounded Knee occurred, causing rising tensions between the government and Native American activists. The event grabbed the attention of the US and the world media. This was considered a major event and victory for the movement by its supporters and participants.

Outside of his film work, Brando appeared before the California Assembly in support of a fair housing law and personally joined picket lines in demonstrations protesting discrimination in housing developments.

Comments on Jews, Hollywood, and Israel

In an interview in Playboy magazine in January 1979, Brando said: "You've seen every single race besmirched, but you never saw an image of the kike because the Jews were ever so watchful for that—and rightly so. They never allowed it to be shown on screen. The Jews have done so much for the world that, I suppose, you get extra disappointed because they didn't pay attention to that."[58]

Brando made a similar comment on Larry King Live in April 1996, saying "Hollywood is run by Jews; it is owned by Jews, and they should have a greater sensitivity about the issue of—of people who are suffering. Because they've exploited—we have seen the—we have seen the Nigger and Greaseball, we've seen the Chink, we've seen the slit-eyed dangerous Jap, we have seen the wily Filipino, we've seen everything but we never saw the Kike. Because they knew perfectly well, that that is where you draw the wagons around." Larry King, who is Jewish, replied, "When you say—when you say something like that you are playing right in, though, to anti-Semitic people who say the Jews are—" at which point Brando interrupted. "No, no, because I will be the first one who will appraise the Jews honestly and say 'Thank God for the Jews.'"[59]

Jay Kanter, Brando's agent, producer and friend defended him in Daily Variety: "Marlon has spoken to me for hours about his fondness for the Jewish people, and he is a well-known supporter of Israel."[60] Similarly, Louie Kemp, in his article for Jewish Journal, wrote: "You might remember him as Don Vito Corleone, Stanley Kowalski or the eerie Col. Walter E. Kurtz in "Apocalypse Now," but I remember Marlon Brando as a mensch and a personal friend of the Jewish people when they needed it most."[22] Brando was also a major donor to the Irgun, a Zionist political-paramilitary group. In his later years he became critical of Israel and a supporter of the Palestinian cause.[61][62]

In an interview with NBC Today one day after Brando's death, King also defended Brando's comments, saying that they were blown out of proportion and taken out of context.

Legacy

"That will be Brando's legacy whether he likes it or not -- the stunning actor who embodied a poetry of anxiety that touched the deepest dynamics of his time and place."

—Jack Kroll in 1994

Honors and tributes

Brando is widely considered as one of the greatest and most influential actors of the 20th century.[63] He has earned great respect among critics and theater experts for his memorable performances and charismatic screen presence.[64] In the book Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia, James Delmont wrote: "Marlon Brando was arguably the finest screen actor of the twentieth century, winning worldwide acceptance as both a movie star of the first rank and as a performer of uncommon skill."[2] Film scholar Richard Schickel, while examining his charismatic screen presence and acting ability, argued: "As a movie actor he [Brando] has no peer in this generation. That he consistently underplays, yet still packs more emotion into a scene than anyone else, is a sign of a charisma that may be an act of God."[65] Similarly, Roger Ebert, writing of his iconic performance in Last Tango in Paris, said: "This was the greatest movie actor of his time, the author of performances that do honor to the cinema."[66]

Tennessee Williams, among the many who acknowledged his finesse, described Brando as "the greatest living actor ever... greater than [Laurence] Olivier."[67] Laurence Olivier himself said: "Brando acted with an empathy and an instinctual understanding that not even the greatest technical performers could possibly match."[65] Johnny Depp credits Brando with changing the way actors work, stating that "Marlon reinvented acting, he revolutionized acting."[68] Depp also said he was "probably the most important actor - just speaking in terms of him as an actor - of the past two centuries".[69] In a 2007 Best Life article, praising his performance in On the Waterfront, Rob Reiner wrote: "Marlon Brando gives the single greatest performance ever. It's just so natural, powerful, real, and honest."[70]

Cultural influence

"The art of screen acting has two chapters-"Before Brando" and "After Brando." Though Stanislavski created "method acting," it was Brando who showed the world its power."

—American Film Institute's Moments of Significance

Marlon Brando is a cultural icon whose popularity has endured for over six decades. His rise to national attention in the 1950s had a profound effect on the motion picture industry and influenced the broader scope of American culture.[71] According to film critic Pauline Kael, "[Marlon] Brando represented a reaction against the post-war mania for security. As a protagonist, the Brando of the early fifties had no code, only his instincts. He was a development from the gangster leader and the outlaw. He was antisocial because he knew society was crap; he was a hero to youth because he was strong enough not to take the crap ... Brando represented a contemporary version of the free American ... Brando is still the most exciting American actor on the screen."[71] Sociologist Dr. Suzanne Mcdonald-Walker states: "Marlon Brando, sporting leather jacket, jeans, and moody glare, became a cultural icon summing up 'the road' in all its maverick glory."[72] His portrayal of the gang leader Johnny Strabler in The Wild One has become an iconic image, used both as a symbol of rebelliousness and a fashion accessory that includes a Perfecto style motorcycle jacket, a tilted cap, jeans and sunglasses. Johnny's haircut inspired a craze for sideburns, followed by James Dean and Elvis Presley, among others.[63] Dean copied Brando's acting style extensively and Presley used Brando's image as a model for his role in Jailhouse Rock.[73] The "I coulda been a contenda" scene from On the Waterfront, according to the author of Brooklyn Boomer, Martin H. Levinson, is "one of the most famous scenes in motion picture history and the line itself has become part of America's cultural lexicon."[63] Brando's powerful 'Wild One' image was still as of 2011 being marketed by the makers of his Triumph Thunderbird motorcycle in a range of clothing inspired by his character from the film and licenced by Brando's estate.[74]

Brando was also considered a sex symbol, one of the earliest in the film industry to achieve widespread attention due to his enigmatic and sexy persona and the reports of his dalliances and relationships with various major Hollywood celebrities. Film scholar Linda Williams writes: "Marlon Brando [was] the quintessential American male sex symbol of the late fifties and early sixties".[75]

Brando was one of the first actor-activists to march for civil and Native American rights.

Financial legacy

Upon his death in 2004, Brando left an estate valued at $21.6 million.[76] Brando's estate still earns about $9,000,000 per year, according to Forbes. He was named one of the top-earning dead celebrities in the world by the magazine.[77]

Filmography

Honors, awards and nominations

Brando was named the fourth greatest male star[78] in the history of American cinema by the American Film Institute,[79] and part of Time magazine's Time 100: The Most Important People of the Century.[80] He was also named one of the top 10 "Icons of the Century" by Variety magazine.[65][81]

References

Notes

- ^ "Marlon Brando Biography." Movies.yahoo.com. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Dimare 2011, pp. 580–582.

- ^ "Marlon Brando, 1924-2004: One of the Greatest Actors of All Time." Voice of America. Retrieved: 15 September 2011.

- ^ "Brando: A TCM Documentary." Johnnydepp82989.yuku.com, May 1, 2007. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Cavett, Dick. "A Third Bit of Burton." The New York Times, September 25, 2009. Retrieved: May 12, 2010.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture

- ^ Kanfer 2008, p. 319.

- ^ "Time 100 Persons Of The Century." Time Magazine, June 14, 1999. Retrieved: 15 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d Brando and Lindsey 1994, pp. 32, 34, 43.

- ^ "Brando." The New Yorker, Volume 81, Issues 43-46, p. 39.

- ^ Bly 1994, p. 11.

- ^ Kanfer 2008, pp. 5, 6.

- ^ "The religion of Marlon Brando, actor." Adherents.com. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Bain 2004, pp. 65–66.

- ^ "Marlon Brando Biography (1924–)." Filmreference.com. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Kanfer 2008, p. 134.

- ^ Elder, Robert K. "Marlon Brando, 1924–2004: Illinois youth full of anger, family strife. Chicago Tribune, July 3, 2004.

- ^ "A biography of Marlon Brando." enotalone.com. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Brando and Lindsey 1994, p. 83.

- ^ Adler and Paris 1999, p. 271.

- ^ a b Louie Kemp. My Seder With Brando. The Jewish Journal.

- ^ "David S. Wyman Institute for Holocaust Studies: Welcome." Wymaninstitute.org. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Mosel, "Leading Lady: The World and Theatre of Katharine Cornell

- ^ Pierpont writes that John Garfield was first choice for the role, but "made impossible demands." It was Elia Kazan's decision to fall back on the far less experienced (and technically too young for the role) Brando.

- ^ "Somebody Up There Like's Me" Graziano 1955

- ^ Voynar, Kim. "Lost Brando Screen Test for Rebel Surfaces – But It's Not for the Rebel We Know and Love." Cinematical, Weblogs, Inc., March 28, 2006. Retrieved: April 3, 2008.

- ^ Crouch, Stanley. "How DVD adds new depth to Brando's greatness." Slate Magazine, January 25, 2007. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Pierpont 2008, p. 71.

- ^ "American Indians mourn Brando's death – Marlon Brando (1924–2004)." MSNBC. July 2, 2004. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Schickel, Richard. "A Legend 'Writes' a Novel." Time, August 7, 2005.

- ^ "Brando was working on final film." Ireland Online, March 7, 2004. Retrieved: May 1, 2010.

- ^ "Brando Was Working on New Script." Fox News, July 2, 2004. Retrieved: May 1, 2010.

- ^ "Brando's final film back on track." BBC News, May 25, 2006.

- ^ Laporte, Nicole. "Helmer revives 'Brando' project." Variety, May 25, 2006.

- ^ Motion Picture,1961.

- ^ "institut nationale de l'audiovisuel archivepourtous " (in French). Ina.fr. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ "Short fims." Dailymotion. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ "Love Life as Big as the Legend." Nydailynews.com, July 3, 2004. [dead link]

- ^ "Film legend Marlon Brando dies." Deseretnews.com, July 3, 2004. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Heller, Matthew (10 July 2004). "Brando Will Left Zilch For 2 Kids". Daily News. Retrieved 20 September 2012.

- ^ Kanfer 2008, p. 310

- ^ "Last Tango on Brando Island." Maxim.com, July 1, 2004. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ "Brando." Los Angeles Magazine, Vol. 49, No. 9, September 2004. ISSN 1522-9149.

- ^ Stern 2009, p. 70.

- ^ Sancton, Julian. "Last Tango on Brando Island." Maxim. [dead link]

- ^ Kanfer 2008, p. 271.

- ^ "Amateur License - KE6PZH - BRANDEAUX, MARTIN". Federal Communications Comission: Universal Licensing System. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ "Brando, Jackson of his closest friends Neverland as 2nd home." MJNewsOnline.com November 11, 2006.

- ^ "Marlon Brando dies at 80." CNN.com July 2, 2004. Retrieved: April 3, 2008.

- ^ "Brando biography." New Netherland Institute/ Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ "When the wild one met the mild one." latimes.com, October 17, 2004.

- ^ Porter, Dawn. "Wild things." The Times, February 12, 2006.

- ^ Brooks, Xan. "The last word on Brando." The Guardian, May 22, 2007. Retrieved: April 6, 2008.

- ^ Baker, Russell. "Capital Is Occupied by a Gentle Army." (PDF) The New York Times, August 28, 1963, p. 17.

- ^ "Archival footage of Marlon Brando with Bobby Seale in Oakland, 1968." Diva.sfsu.edu. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ The Academy. "Marlon Brando's Oscar Win For The Godfather"

- ^ Grobel, Lawrence. "Playboy Interview: Marlon Brando." Playboy, January 1979, ISSN 0032-1478. Retrieved: April 3, 2008.

- ^ "Marlon Brando on Jewish Influence On U.S. Culture in Films." Washington-report.org. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Tugend, Tom. "Jewish groups riled over Brando's attacks." Jewish Telegraphic Agency, April 1996.

- ^ Palestinian cause

- ^ "Is NPR Anti Semitic?" haemtza, March 25, 2009. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ a b c Levinson 2011, p. 81.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. "Marlon Brando: Film Biography". All Movie Guide. Retrieved: August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Marlon Brando Quotes." Flixster. Retrieved: August 19, 2009.

- ^ Ebert 2010, p. 218.

- ^ Porter 2006, p. 117.

- ^ "Larry King's interview with Johnny Depp airs Sunday @ 8pm." CNN. Retrieved: October 25, 2011.

- ^ TV Week magazine 29 April 1995. "Johnny Takes a Short Cut to Success", pp. 16–17.

- ^ "Director's Cut: Rob Reiner's Picks on DVD." Best Life, December 2007/January 2008. Retrieved: August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Kael, Pauline. "Marlon Brando: An American Hero." The Atlantic. Retrieved: August 19, 2011.

- ^ McDonald-Walker 2000, p. 212.

- ^ Kaufman and Kaufman 2009, p. 38.

- ^ "Triumph to produce replicas of Marlon Brando's leather jacket from the Wild One." old.boxwish.com. Retrieved: June 10, 2012.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 114.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. "Marlon Brando Leaves $21.6 Million Estate." People, August 4, 2007. Retrieved: August 19, 2011.

- ^ Kafka, Peter and Leah Hoffmann. "Top-Earning Dead Celebrities." Forbes, October 27, 2005. Retrieved: August 19, 2011.

- ^ Among actors whose screen debuts occurred in or before 1950, or whose screen debut occurred after 1950 but whose death has marked a completed body of work.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years ... 100 Stars." afi.com.. Retrieved: December 1, 2012.

- ^ Marlon Brando TIME.[dead link]

- ^ "100 Icons of the Century: Marlon Brando." Variety. Retrieved: August 19, 2011.

Bibliography

- Adler, Stella and Barry Paris. Stella Adler on Ibsen, Strindberg, and Chekhov. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999. ISBN 0-679-42442-3.

- Bain, David Haward. The Old Iron Road: An Epic of Rails, Roads, and the Urge to Go West. New York: Penguin Books, 2004. ISBN 0-14-303526-6.

- Bly, Nellie. Marlon Brando: Larger than Life. New York: Pinnacle Books/Windsor Pub. Corp., 1994. ISBN 0-7860-0086-4.

- Bosworth, Patricia. Marlon Brando. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2001. ISBN 0-297-84284-6.

- Brando, Anna Kashfi and E.P. Stein. Brando for Breakfast. New York: Crown Publishers, 1979. ISBN 0-517-53686-2.

- Brando, Marlon and Donald Cammell. Fan-Tan. New York: Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4471-5.

- Brando, Marlon and Robert Lindsey. Brando: Songs My Mother Taught Me. New York: Random House, 1994. ISBN 0-679-41013-9.

- Dimare, Philip C. Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO, 2011. ISBN 1-59884-296-X.

- Ebert, Roger. The Great Movies III. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010. ISBN 0-226-18208-8.

- Englund, George. The Way It's Never Been Done Before: My Friendship With Marlon Brando. New York: Harper Collins Publishers, 2004. ISBN 0-06-078630-2.

- Kanfer, Stefan. Somebody: The Reckless Life and Remarkable Career of Marlon Brando. New York: Knopf, 2008. ISBN 978-1-4000-4289-0.

- Kaufman, Burton I. and Diane Kaufman. The A to Z of the Eisenhower Era. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2009. ISBN 0-8108-7150-5.

- Levinson, Martin H. Brooklyn Boomer: Growing Up in the Fifties. Bloomington, Indiana: iUniverse, 2011. ISBN 1-4620-1712-6.

- McDonald-Walker, Suzanne. Bikers: Culture, Politics and Power. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers, 2000. ISBN 1-85973-356-5

- Pierpont, Claudia Roth. Method Man. New Yorker, October 27, 2008.

- Porter, Darwin. Brando Unzipped: A Revisionist and Very Private Look at America's Greatest Actor. Staten Island, New York: Blood Moon Productions, Ltd., 2006. ISBN 0-9748118-2-3.

- Stern, Keith. Queers in History: The Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Historical Gays, Lesbians and Bisexual. Jackson, Tennessee: BenBella Books, 2009. ISBN 1-933771-87-9.

- Williams, Linda. Screening Sex. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8223-4285-5.

External links

- Marlon Brando at IMDb

- Marlon Brando at the TCM Movie Database

- Marlon Brando at the Internet Broadway Database

- Marlon Brando at AllMovie

- The Oddfather, Rolling Stone, Jod Kaftan, April 25, 2002

- Vanity Fair: The King Who Would Be Man by Budd Schulberg

- The New Yorker: The Duke in His Domain – Truman Capote's influential 1957 interview.

Obituaries

- 1924 births

- 2004 deaths

- 20th-century American actors

- 21st-century American actors

- Actors from Omaha, Nebraska

- Actors Studio members

- Amateur radio people

- American Christian Scientists

- American film actors

- American film directors

- American people of Dutch descent

- American people of English descent

- American people of German descent

- American people of Irish descent

- American stage actors

- American television actors

- Best Actor Academy Award winners

- Best Drama Actor Golden Globe (film) winners

- Best Foreign Actor BAFTA Award winners

- Bisexual actors

- Bisexual men

- Deaths from pulmonary fibrosis

- Deaths from respiratory failure

- Deists

- Disease-related deaths in California

- Emmy Award winners

- Illinois Democrats

- LGBT entertainers from the United States

- Native Americans' rights activists

- People from Evanston, Illinois

- People from Libertyville, Illinois

- People from Omaha, Nebraska

- Stella Adler Studio of Acting alumni

- David di Donatello winners

- LGBT Christians