Bayview–Hunters Point, San Francisco

Bayview–Hunters Point | |

|---|---|

A bird's-eye view of the Bayview–Hunters Point neighborhood of San Francisco. Candlestick Park, demolished in 2015, is in the foreground | |

| Nicknames: The Point, The Port, The Yard (ref to the Shipyard), The Bayview, HP, Butchertown (1830s-1960s), District 10 (in politics), Bayview-HP (shortened in media), BVHP (abbreviated) | |

| Coordinates: 37°43′37″N 122°23′19″W / 37.72687°N 122.38873°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City-county | San Francisco |

| Government | |

| • Supervisor | Shamann Walton |

| • Assemblymember | Matt Haney (D)[1] |

| • State senator | Scott Wiener (D)[1] |

| • U. S. rep. | Barbara Lee (D)[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 3.95 sq mi (10.2 km2) |

| Population (2010)[4] | |

| • Total | 35,890 |

| Time zone | UTC−8 (Pacific) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−7 (PDT) |

| ZIP Code | 94124 |

| Area codes | 415/628 |

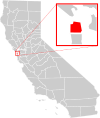

Bayview–Hunters Point (sometimes spelled Bay View) are two major neighborhoods — Bayview and Hunters Point — in the southeastern corner of San Francisco, California, United States. The decommissioned Hunters Point Naval Shipyard is located within its boundaries and Candlestick Park, which was demolished in 2015, was on the southern edge. Due to the South East location, the two neighborhoods are often merged. Bayview-Hunter's Point has been labeled as San Francisco's "Most Isolated Neighborhood".[5]

Redevelopment projects for the neighborhood became the dominant issue of the 1990s and 2000s. Efforts include the Bayview Redevelopment Plan for Area B, which includes approximately 1300 acres of existing residential, commercial and industrial lands. This plan identifies seven economic activity nodes within the area. The former Navy Shipyard waterfront property is also the target of redevelopment to include residential, commercial, and recreational areas.[6]

Geography

The Bayview–Hunters Point districts are located in the southeastern part of San Francisco, strung along the main artery of Third Street from India Basin to Candlestick Point. The boundaries are Cesar Chavez Boulevard to the north, U.S. Highway 101 (Bayshore Freeway) to the west, Bayview Hill to the south, and the San Francisco Bay to the east. Neighborhoods within the district include Hunters Point, India Basin, Bayview, Silver Terrace, Bret Harte, Islais Creek Estuary and South Basin. The entire southern half of the neighborhood is the Candlestick Point State Recreation Area as well as the Candlestick Park Stadium[3] which was demolished in 2015.

History

Primarily composed of tidal wetlands with some small hills, the area was inhabited by the Yelamu, Ramaytush and Muwekma Ohlone people prior to the arrival of Spanish missionaries in the 1700s. The Ohlone inhabited the land for ten thousand years[citation needed]. The district consisted of what the Ohlone people called "shell mounds", which were sacred burial grounds. The land was later colonized in 1775 by Juan Bautista Aguirre,[7] a ship pilot for Captain Juan Manuel de Ayala who named it La Punta Concha (English: Conch Point).[8] Later explorers renamed it Beacon Point.[9] For the next several decades it was used as pasture for cattle run by the Franciscan friars at Mission Dolores.[8]

In 1839, the area was part of the 4,446-acre (17.99 km2) Rancho Rincon de las Salinas y Potrero Viejo Mexican land grant given to José Cornelio Bernal (1796–1842). Following the California Gold Rush, Bernal sold what later became the Bayview–Hunters Point area for real estate development in 1849. Little actual development occurred but Bernal's agents were three brothers, John, Phillip and Robert Hunter, who built their homes and dairy farm on the land (then near the present-day corner of Griffith Street and Oakdale Avenue) and who gave rise to the name Hunters Point.[8]

The Bayview–Hunters Point district was labelled "Southern San Francisco" on some maps, not to be confused with the city of South San Francisco further to the south.

Islais Creek and "Scared Sites"

The Muwekma Ohlone held and still hold Islais Creek by 3rd Street and Marin in the Bayview as one of fifty, "sacred sites". Unfortunately Islais Creek and the adjoining bay has been heavily polluted.[10]

Industrial development

After a San Francisco ordinance in 1868 banned the slaughter and processing of animals within the city proper, a group of butchers established a "butchers reservation" on 81-acre (0.33 km2) of tidal marshland in the Bayview district. Within ten years, 18 slaughterhouses were located in the area along with their associated production facilities for tanning, fertilizer, wool and tallow. The "reservation" (then bounded by present-day Ingalls Street, Third Street, from Islais Creek to Bayshore) and the surrounding houses and businesses became known as Butchertown. The butcher industry declined following the 1906 San Francisco earthquake until 1971 when the final slaughterhouse closed.[11]

From 1929 until 2006 the Bayview–Hunters Point district were home for the coal and oil-fired power plants which provided electricity to San Francisco. Smokestack effluvium and byproducts dumped in the vicinity have been cited for health and environmental problems in the neighborhood. In 1994, the San Francisco Energy Company proposed building another power plant in the neighborhood, but community activists protested and pushed to have the current facility shut down.[12] In 2008, Pacific Gas and Electric Company demolished the Hunters Point Power Plant and began a two-year remediation project to restore the land for residential development.[13] The area remains a hub of business along 3rd Street, represented by the Merchants of Butchertown.[14]

Shrimping Industry

From 1870 to the 1930s, shrimping industries developed as Chinese immigrants begin to operate most of the shrimp companies. By the 1930s, there were a dozen shrimp operations in Bayview.[15]

Shipyard

Shipbuilding became integral to Bayview–Hunters Point in 1867 with the construction there of the first permanent drydock on the Pacific coast. The Hunters Point Dry Docks were greatly expanded by Union Iron Works and Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation and were capable of housing the largest ships that could pass through the locks of the Panama Canal. World War I increased the contracts there for building Naval vessels and, in 1940, the United States Navy purchased a section of property to develop the San Francisco Naval Shipyard. Beginning in the 1920s, a strong presence of Maltese American immigrants, along with Italian Americans, began populating the Bayview, focused on the local Catholic St. Paul of the Shipwreck Church and the Maltese American Social Club. They were a presence until the 1960s when they began moving into the suburbs.

The shipbuilding industry saw a large influx of blue collar workers into the neighborhood, many of them African Americans taking part in the Great Migration. This migration into Bayview increased substantially after World War II due to racial segregation and eviction of African Americans from homes elsewhere in the city.[16] Between 1940 and 1950, the population of Bayview saw a fourfold increase to 51,000 residents.[17] The Hunter's Point shipyard at its peak employed 17,000 people and it was also where the first atomic bomb sailed for Japan in 1945.[18]

Until 1969, the Hunters Point shipyard was the site of the Naval Radiological Defense Laboratory (NRDL). The NRDL decontaminated ships exposed to atomic weapons testing and also researched the effects of radiation on materials and living organisms.[19] This caused widespread radiological contamination and, in 1989, the base was declared a Superfund site requiring long-term clean-up.[20][21] The Navy closed the shipyard and Naval base in 1994. The Base Realignment and Closure program manages various pollution remediation projects.[19]

Environmental Impact Report

On January 10, 2010, Ohlone representatives, Ann Marie Sayers, Corrina Gould, Charlene Sul and Carmen Sandoval, Ohlone Profiles Project, American Indian Movement West and International Indian Treaty Council penned a letter to then mayor of San Francisco, Gavin Newsom about preserving the Ohlone historical sites at the Candlestick Point-Hunters Point Shipyard stating “This is an important opportunity to work together to protect these ancient historical sites, honor our ancestors and insure that development pressures do not further damage critical Ohlone Indigenous sites, the sites affected by the development are extremely significant and are believed to be burial or ceremonial sites, in addition to protecting these sites, we also want to work with the local community to protect their health, the land and the fragile Bay marine environment.”[22]

On June 12, 2014, Vice published an article on the history, environmental bigotry and radiation effects on the residents of the neighborhood.[23]

African-American Community Development

During the 1950s and 60s, the Bayview was a predominantly African-American neighborhood that housed a movie theater along the Third Street corridor, as well as a library, a gymnasium at the time, Cub scouts through "Rec and Park" as well as youth baseball teams such as "The Blue Diamonds" of Innes [Street].[24]

Racial tensions

By the 1960s, the Bayview and Hunters Point neighborhoods were populated predominantly by African-Americans and other racial minorities, and the area was isolated from the rest of San Francisco. Pollution, substandard housing, declining infrastructure, limited employment and racial discrimination were notable problems. James Baldwin documented the marginalization of the community in a 1963 documentary, "Take This Hammer", stating, "this is the San Francisco America pretends does not exist."[9][25] On September 27, 1966, a race riot occurred at Hunters Point,[26] sparked by the killing of a 16-year-old fleeing from a police officer. The policeman, Alvin Johnson, stated he "caught [a couple of kids] red-handed with a stolen car" and ordered Matthew Johnson to stop, firing several warning shots before fatally shooting Johnson.[27] In 1967 US Senators Robert F. Kennedy, George Murphy and Joseph S. Clark visited the Western Addition and Bayview-Hunter's Point Neighborhood accompanied by future mayor Willie Brown to speak to activist Ruth Williams about the inequalities occurring in the Bayview.[28] Closure of the naval shipyard, shipbuilding facilities and de-industrialization of the district in the 1970s and 1980s increased unemployment and local poverty levels.[9]

Building projects to revitalize the district began in earnest in the 1990s and the 2000s. As in the rest of the city, housing prices rose 342% between 1996 and 2008. Many long-time African American residents, whether they could no longer afford to live there or sought to take advantage of their homes' soaring values, left what they perceived as an unsafe neighborhood and made an exodus to the Bay Area's outer suburbs. Once considered a historic African American district, the percentage of black people in the Bayview–Hunters Point population declined from 65 percent in 1990 to a minority in 2000.[29] Despite the decline, the 2010 U.S. Census shows the African American population in the Bayview to be greater in number than that of any other ethnicity.

In the 2000s, the neighborhood became the focus of several redevelopment projects. The MUNI[30] T-Third Street light-rail project was built through the neighborhood, replacing an aging bus line with several new stations, street lamps and landscaping. Private developer Lennar Inc. proposed a $2-billion project to build 10,500 homes, including rentals, and commercial spaces atop the former Hunters Point Naval Shipyard, and a new football stadium for the San Francisco 49ers, and a shopping complex for Candlestick Point. The stadium would reinvigorate the district, but the 49ers changed their focus to Santa Clara in 2006. A bid for the 2016 Summer Olympics in San Francisco that included plans to build an Olympic Village in Bayview–Hunters Point was also dropped.[31] Lennar Inc. proposed to build the stadium without the football team.[32] Local community activist groups have criticized much of the redevelopment for displacing rather than benefiting existing neighborhood residents.[9]

As of 2014[update], Lennar works on the mixed-use development, promising "12,500 new homes; 4 million-plus square feet of office, commercial and retail space; and 300 acres of open parks, trails and fields", although no rentals.[33]

Education

The Bayview, a historically predominant black neighborhood, is home to more elementary school-age students than any other neighborhood in the city and combined with the Mission and Excelsior, houses a quarter of all students in the district. Schools in the Bayview have suffered from declining enrollment for the past two decades. Out of the 6,000 students who live in the Bayview, more than 70% choose to attend school outside of their neighborhood.[34] In 2016, in attendance with Jonathan Garcia, Adonal Foyle and Theo Ellington, Willie L. Brown middle school in Bayview-Hunter's Point commemorated the unveiling of the new Golden State Warrior outside basketball court at the school, donated by the Warriors Community Foundation.[35] Bayview-Hunter's Point has several elementary and middle schools, one high school and has two college campuses. The schools include:

Elementary and early enrichment

- Whitney Young Development Center (now FACES SF)

- Erikson School (K)

- Frandelja Enrichment Center Fairfax

- Frandelja Enrichment center Gilman

- Success Daycare

- Bret Harte elementary school

- George Washington Carver elementary school

- Hunters Point Number Two School

- Charles R. Drew Elementary School

- Leola M. Havard Early Education School

- Malcolm X Academy

Middle and junior high schools

- Joshua Marie Cameron Academy

- KIPP Bayview Academy

- KIPP San Francisco College Preparatory

- Willie L. Brown Jr. Middle School

- One Purpose School (K-12)

- Thurgood Marshall High School

- Rise University Preparatory

High schools

- One Purpose School (K-12)

- Thurgood Marshall High School

- Joshua Marie Cameron Academy (7-12)

- Coming Of Age Christian Academy (K-12)

Colleges

- City College of San Francisco - Evans Center

- City College of San Francisco - Oakdale Center

After school programs

- YMCA - Bayview

- College Track

- Young Community Developers (YCD)

Demographics

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, Bayview–Hunters Point (ZIP 94124) had a population of 33,996, an increase of 826 from 2000. The census data showed the single-race racial composition of Bayview–Hunters Point was 33.7% African-American, 30.7% Asian (22.1% Chinese, 3.1% Filipino, 2.9% Vietnamese, 0.4% Cambodian, 0.3% Indian, 0.2% Burmese, 0.2% Korean, 0.2% Japanese, 0.2% Pakistani, 0.1% Laotian), 12.1% White, 3.2% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (2.4% Samoan, 0.1% Tongan, 0.1% Native Hawaiian), 0.7% Native American, 15.1% other, and 5.1% mixed race. Of Bayview's population, 24.9% was of Hispanic or Latino origin, of any race (11.5% Mexican, 4.2% Salvadoran, 2.6% Guatemalan, 1.4% Honduran, 1.4% Nicaraguan, 0.7% Puerto Rican, 0.2% Peruvian, 0.2% Spanish, 0.2% Spaniard, 0.1% Colombian, 0.1% Cuban, 0.1% Panamanian).[36]

According to the 2010 U.S. Census, Bayview–Hunters Point had the highest percentage of African-Americans among San Francisco neighborhoods, home to 21.5% of the city's Black population, and they were the predominant ethnic group in the Bayview. Census figures showed the percentage of African-Americans in Bayview declined from 48% in 2000 to 33.7% in 2010, while the percentage of Asian and White ethnicity increased from 24% and 10%, respectively, to 30.7% and 12.1%. However the eastern part of the neighborhood had a population of 12,308 and is still roughly 53% African-American.

According to the 2005–2009 American Community Survey (ACS), the Bayview district is estimated to have 10,540 housing units and an estimated owner-occupancy rate of 51%. The 2010 U.S. Census indicates the number of households to be 9,717, of which 155 belong to same-sex couples. Median home values were estimated in 2009 to be $586,201,[4] but that has since fallen dramatically to around $367,000 in 2011, the lowest of any of San Francisco's ZIP code areas.[37] Median Household Income was estimated in 2009 at $43,155.[4] Rent prices in the Bayview remain relatively low, by San Francisco standards, with over 50% of rents paid in 2009 at less than $750/mo.[38]

A recent Brookings Institution report identified Hunters Point as one of five Bay Area "extreme poverty" neighborhoods, in which over 40% of the inhabitants live below the Federal poverty level of an income of $22,300 for a family of four.[39] Nearly 12% of the population in the Bayview receives public assistance income, three times the national average, and more than double the state average. While the Bayview has a higher percentage of the population receiving either Social Security or retirement income than the state or national averages, the dollar amounts that these people receive is less than the averages in either the state or the nation.

Marginalization

Since the 1960s, the Bayview–Hunters Point community has been cited as a significant example of marginalization.[9] In 2011, it remained "one of the most economically disadvantaged areas of San Francisco".[40] Root causes include a working class populace historically segregated to the outskirts of the city, high levels of industrial pollution, the closure of industry, and loss of infrastructure.[9] The results have been high rates of unemployment, poverty, disease and crime.[41] [9][42] Attempts to mitigate the effects of marginalization include the city's building of the Third Street light-rail line, establishment of the Southeast Community Facility (SECF) as a response from the SF Public Utilities Commission to a community-led effort to balance environmental injustice associated with public utilities,[43] the Southeast Food Access Workgroup,[44] initially formed by the SF Department of Public Health as part of the SF Mayor's ShapeUp SF health initiative, and implementation of enhanced local hiring policy that recognizes that regulations requiring hiring for public projects prioritize City residents and contractors may not help specific neighborhoods where job seekers and contractors may still be overlooked. Place-based and asset-based community building programs networked through the Quesada Gardens Initiative began in 2002 adding direct grassroots public participation to the social and environmental change landscape with a goal of preserving diversity and encouraging longterm residents to reinvest in their neighborhood.

The Hunter's Point shipyard's toxic waste pollution has been cited for elevated rates of asthma and other respiratory diseases among residents.[40] These adverse health effects coupled with rising housing costs contribute to what one community member and organizer has characterized as behavior "meeting the UN standard definition of genocide".[45]

Gang and drug activity, as well as a high murder rate, have plagued the Bayview–Hunters Point district.[46] A 2001 feature article in the San Francisco Chronicle cited feuding between small local gangs as the major cause of the area's unsolved homicides.[42] In 2011, The New York Times described Bayview as "one of the city's most violent" neighborhoods.[47] Police have made the removal of guns from the streets their top priority in recent years, leading to a 20% decline in major crimes between 2010 and 2011, including declines of 35% in homicides, 22% in aggravated assaults, 38% in arson, 30% in burglary, 34% in theft, 23% in auto theft, and 39% in robbery. Lesser crimes have also declined by about 24% over the past year.[citation needed]

Food Desert

Until the late 2000s the neighborhood had no chain supermarkets.[48] In 2011, a San Francisco official described the area as "a food desert – an area with limited access to affordable, nutritious food like fresh produce at a full-size grocery store."[49] A large swath of the southeast sector of San Francisco sits within a Federally recognized food desert.[50] A Home Depot was approved by the city to be built in the area, but the Home Depot Corporation abandoned its plans following the late 2000s economic crisis.[51] Lowe's took over Home Depot's plans, and in 2010 opened their first store in San Francisco on the Bayshore Blvd. site. In August 2011, UK supermarket chain Tesco, owner of Fresh and Easy stores, opened Bayview–Hunters Point's first new grocery store in 20 years, though this store has closed as part of Fresh and Easy's larger corporate exit from the United States.[49][52]

The neighborhood was the subject of a 2003 documentary, Straight Outta Hunters Point,[53] directed by lifelong Hunters Point resident Kevin Epps, and a 2012 sequel, "Straight Outta Hunters Point 2," movies that expose the daily drama of gang-related wars plaguing a community already fighting for social and economic survival. The Spike Lee film Sucker Free City used Hunters Point as a backdrop for a story on gentrification and street gangs.[54]

Community activism

In April 1968, baseball icon, hall-of-fame inductee, and San Francisco Giants legend, Willie Mays and Osceola Washington campaigned for "Blacks and Whites Together Fund Drive for Youth Activities this Summer. Bayview-Hunters Point Neighborhood Community Center."[55]

A number of community groups, such as the India Basin Neighborhood Association,[56] the Quesada Gardens Initiative,[57] Literacy for Environmental Justice,[58] the Bayview Merchants' Association,[59] the Bayview Footprints Collaboration of Community-Building Groups,[60] and Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice[61] work with community members, other organizations and citywide agencies to strengthen, improve, and fight for the protection of this diverse part of San Francisco.

Community gardening, art, and social history are popular in the area. The Quesada Gardens Initiative is a well recognized organization that has created a cluster of 35 community and backyard gardens in the heart of the neighborhood, including the original Quesada Garden on the 1700 block of Quesada Ave., the Founders' Garden, Bridgeview Teaching and Learning Garden (which won the 2011 Neighborhood Empowerment Network's[62] "Best Green Community Project Award," Krispy Korners, the Latona Community Garden, and the new Palou Community Garden. Major public art pieces honor unique hyper-local history, grassroots involvement, and the right of communities to define themselves.

Redevelopment

The Anna E. Waden Library finished construction in 2013, it was renamed in honor of Linda Brooks-Burton in 2015 and is located at Third Street and Revere.[63]

Hunters Point Shipyard is a redevelopment project by Lennar Corporation on the 702 acres at Candlestick Point and the San Francisco Naval Shipyard.[64] The plan called for 10,500 residential units, a new stadium to replace Candlestick Park, 3,700,000 square feet (340,000 m2) of commercial and retail space, an 8,000- to 10,000-square-foot (930 m2) arena; artists' village and 336 acres of waterfront park and recreational area.[65] The developers said the project would contribute up to 12,000 permanent jobs and 13,000 induced jobs.[66]

The approval process required developers to address concerns of area residents and San Francisco government officials. Criticism of the project focused on the large-scale toxic clean-up of the industrial superfund site, environmental impact of waterfront construction, displacement of an impoverished neighborhood populace and a required build-up to solve transportation needs.[65]

In July 2010, Lennar Corporation received initial approval of an Environmental Impact Report from San Francisco supervisors.[66][67] In September 2011, the court denied the transfer of property to Lennar Corporation prior to clean-up of contamination.[40] Per a letter sent from the EPA to the Navy, the process was placed on hold until “the actual potential public exposure to radioactive material at and near” the shipyard can be “clarified.”[68]

"I am Bayview" campaign

Partnered with the office of Supervisor of District 10 Malia Cohen and Bayview Underground, I am Bayview helmed by creative George McCalman and photographer Jason Madara created a series of images of photographed community members to visually communicate gentrification. George states that if "one is going to move into a neighborhood, you should get to know the people who live there, not simply displace an existing community. Gentrification is a hot button issue in San Francisco. This was our visual response. Twenty-nine posters are now installed along the 3rd Street corridor of the Dogpatch and Bayview, capturing the Bayview residents who represent their neighborhood proudly."[69]

I am Bayview has also been subject to criticism as some Bayview- and San Franciscan-born people feel it promotes the gentrification of the neighborhood.[70]

Pan-African flags

In 2017, Supervisor Malia Cohen and the city of San Francisco "tagged" Third Street poles with red, black and green stripes in honor of Black History Month and to honor Black residents' heritage in Bayview–Hunters Point.[71]

Arts and technology

The Bayview has also been a quiet hub for the arts and technology going back as far as 1984. The city commissioned a Malcolm X mural on the Kirkwood Star Market, painted by artist Refa-1 in 1997[72] and the murals painted on Joseph Lee Recreational Center by artist Dewey Crumpler in 1984 of Harriet Tubman, Paul Robeson, two Senufo birds which in African culture oversee the lives and creativity of the community, King Tut, Muhammed Ali, Willie Mays, Wilma Rudolph and Arthur Ashe.[73]

Kimberly Bryant founded Black Girls Code, not-for-profit organization that focuses on providing technology education for African-American girls, in the Bayview in 2011.[74]

In 2012, Leila Janah started Samaschool with a pilot program in the Bayview-Hunters Point community. The model originally focused on training students to perform digital work competitively, to prepare them for success on online work sites like oDesk and Elance.[citation needed]

A collaboration was completed with singer-songwriter Michael Franti and Freq Nasty, in which Franti's single "The Future" was remixed in support of a Bay Area nonprofit to help create a music studio for at-risk youth in Bayview-Hunters Point.[citation needed]

Started by Tyra Fennell, Imprint City is a non-profit organization located in the Bayview that is seeks to activate underutilized spaces with arts and culture events as well as community development projects, encouraging increased foot traffic and economic vitality. The BayviewLIVE Festival, celebrates urban performing and visual artists with past featured headliners such as Talib Kweli, Busta Rhymes, Kamaiyah, Nef the Pharaoh and Jidenna.

The Hunters Point Shipyard is home to the country's largest artist colony, "The Point".[75] Zaccho Dance Theatre, founded by Artistic Director Joanna Haigood, is the only professional dance company in BVHP since opening their studio in 1990.[76]

Landmarks and attractions

Historic Houses

Four buildings in the district are listed in the California Registry of Historic Places. The Bayview Opera House (previously South San Francisco Opera House),[77] located at 4705 Third St., was constructed in 1888 and designated a California landmark on December 8, 1968. It was nominated for the National Registry in 2010,[78] and won the Governor's Award for Historic Preservation in 2011.[79] Quinn House, located at 1562 McKinnon Avenue, was built in 1875 and designated 6 July 1974.[80] The Albion Brewery was built in 1870 and opened as the Albion Ale And Porter Brewing Company. Located at 881 Innes Avenue, it was designated April 5, 1974.[81] Sylvester House at 1556 Revere was built in 1870 and designated on April 5, 1974.[82]

Recreation Areas

Candlestick Park

On July 26, 2013, prior to being demolished, Justin Timberlake and Jay-Z brought the Legends of the Summer Stadium Tour to Candlestick Park.

Many acts prior and after had also performed at Candlestick including The Beatles, Rolling Stones, Jimmy Buffett, Van Halen, Scorpions, Metallica and Paul McCartney. Pope John Paul II celebrated a Papal Mass on September 18, 1987 at Candlestick Park during his tour of America.

Martin Luther King Jr Memorial Swimming Pool

In 1968, actor Steve McQueen and mayor Joseph Alioto attended the ceremonial groundbreaking for the Martin Luther King Jr. Memorial swimming pool at Third Street and Carroll Avenue. The makers of McQueen's film 'Bullitt', Warner Bros Studios, donated an initial $25,000 towards the pool's construction in hopes to raise another $50,000 at the movie premiere. Director Woody Allen is also credited with donating $5000 to this project.[83]

Parks

Bayview is home to three large parks: Bayview Park, located on Key Avenue offers sweeping views of the city; Bay View Park accompanied by K.C. Jones playground and Martin Luther King Jr swimming pool; and the Candlestick Point State Recreation Area located on the bay south of Bayview Hill at Candlestick Point is a popular attraction for kayakers and windsurfers. Heron's Head Park, located in the northern part of the neighborhood, is home to a recently resurgent population of Ridgway's rails[84] and the EPA Award-Winning[85] Heron's Head Eco Center.

The Quesada Garden,[57] located on Quesada Avenue and 3rd Street in the heart of the neighborhood, is a landmark community open space on a public right-of-way. It is connected to a showcase community food producing garden (Bridgeview Community Teaching and Learning Garden) by two large murals produced with the community by artists Deidre DeFranceaux, Santie Huckaby, Malik Seneferu, and Heidi Hardin. Together, these projects have turned one of the most dangerous and blighted corridors in San Francisco into the safe route through the neighborhood, and have created a destination point for residents and visitors. Karl Paige and Annette Young Smith, retired residents, started planting on an urban median strip in 2002, and were quickly joined by neighbors to complete what is now a 650-foot by 20-foot focal point for flowers, food, art and community building. Thirteen mature Canary Island date palm trees on the block are on the San Francisco Registry of Historic Trees.

"All My USOS"

Yearly at Gilman Park in Bayview, the Polynesian and Samoan community host a BBQ called "All My USOS". The BBQ is held to honor both the heritage of the communities as well as the humanity amongst people.[86]

Businesses

Also along the Third Street corridor there were two Walgreens. One was located in the Bayview plaza (which is now closed) and another on Williams and Third Street (previously a meat packing company which burned to the ground). There is also a McDonald's located on Wallace Street and a Starbucks coffee in the Bayview plaza.

Speakeasy Brewery offers tours and beer, and hosts live music at their "Final Friday" events.[87] Restaurants such as Chef Eskender Aseged's Radio Africa & Kitchen,[88] Old Skool Cafe,[89] The Jazz Room, Limón Rotisserie,[90] and Brown Sugar Kitchen,[91] join an existing group of established restaurants up and down the Third Street corridor, including Sam Jordan's, Frisco Fried,[92] El Azteca burrito shop, Las Isletas, and "Butcher Town" which includes Gratta Wines and Fox and Lion Bakery.

The San Francisco Wholesale Produce Market,[93] located on Jerrold Ave., has been at the center of food distribution in San Francisco since long before moving to its Bayview location in 1964.

In June 2020, San Francisco native, Reese Benton, opened the cities first black-owned woman-led cannabis dispensary, Posh Green Retail Store.[94]

5700 & 5800 Third Street

5700 and 5800 Third Street in the Bayview has been the host of many businesses including Wing Stop, Limon Rotisserie, Fresh and Easy grocery store, locally owned grocery store Duc Loi as well as restaurants such as CDXX[95] and Corner Café.[96] None of which have been able to remain open.

Post Offices

The Bayview currently has two major USPS offices, the second largest branch (next to Napoleon Street), located on Evans Street and a smaller branch on Williams Street.

In 2012 postmaster Raj Sanghera announced that the Bayview Williams location was taken off the closure list, with other branches as well located in Visitacion Valley, Civic Center, McLaren station and San Bruno Avenue.[97]

Transportation

The Bayview is served by the Muni bus and light rail system and the Caltrain regional rail system. The Bayshore station is on the edge of the Bayview; the neighborhood was also served by the Paul Avenue station until it closed in 2005.

Muni transit lines that run through the Bayview include:

Active lines

- T Third Street

- 23 Monterey

- 54 Felton

- 24 Divisadero

- T Owl

- 9 San Bruno

- 9R San Bruno Rapid

- 10 Townsend

- 19 Polk

- 29 Sunset

- 33 Ashbury/18th Street

- 44 O'Shaughnessy

- 48 Quintara/24th Street

- 54 Felton

- 56 Rutland

- 67 Bernal Heights

- 90 San Bruno Owl

- 91 3rd Street/19th Avenue Owl.

Defunct lines

- 15 Kearny (Now the T Third Street)

- 16 Third Street (Now the T Third Street)

San Francisco 49ers pre and post game-day shuttles

- 75X Candlestick Express Balboa Park Station

- 77X Candlestick Express California and Van Ness

- 78X Candlestick Express Funston and California

- 79X Candlestick Express Sutter and Sansome

- 86 Candlestick Shuttle Bacon and San Bruno

- 87 Candlestick Shuttle Gilman and Third Street

Pop culture

- The San Francisco Bay View is an African-American newspaper with headquarters located on Third Street.

- Thrasher magazine also houses headquarters in the Bayview.

Film

- The Hunters Point Shipyard made a cameo appearance in Alfred Hitchcock's Vertigo. When Scottie Fergusson goes to visit Gavin Elster in the offices of Elster's shipping company, the shipyard's cranes are hard at work in the background. The shipyard scene is projected onto the background to create a virtual location.[98]

- The Bayview's Candlestick Park was also home to the location for the climactic scene in the 1962 thriller Experiment in Terror.

- The 1968 film Bullitt features scenes filmed in the Bayview.

- The 1974 Richard Rush comedy Freebie and the Bean was also filmed at Candlestick Park in Bayview.

- The 1996 Robert DeNiro and Wesley Snipes film The Fan was also filmed in the Bayview.

- In the 2004 Spike Lee film, Sucker Free City, Hunter's-Point was used as a backdrop .[99]

- In the 2006 Will Smith film The Pursuit of Happyness, the film had a scene that took place at Candlestick Park.

- Palm Trees Down 3rd St. (2008)

- In February 2011, scenes for the film Contagion, starring Matt Damon, Kate Winslet and Jude Law, were filmed at Candlestick stadium.

- The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019)

Music Videos

Music videos with prominent artist that feature the Bayview or Hunter's-Point.

- Larry June's music video "Smoothies 1991" (2019)[100]

- Marcus Orelias's music video "Blackouts" featuring Stephan Marcellus (2017)[101]

- Jordan Gomes also known as Stunnaman02's music video "Out that Window" (2019)[102]

Documentaries

- The short film, Point of Pride released in 2014 is a documentary that focuses on the Bayview-Hunter's Point social uprising of the 50s and 60s.[103]

- Straight Outta Hunters Point[104] was a widely successful early 00s documentary made by filmmaker Kevin Epps showcasing the gang violence in Bayview-Hunter's Point.

- Bay View Hunter's Point: San Francisco's Last Black Neighborhood? an Andante Higgins produced documentary (2004)

- A Choice of Weapons (2008)[105]

Television

- Discovery Channel's, Forgotten Planet - Episode 3 focuses on the Hunter's Point Shipyard.[106]

- Sam Jordan's Bar appeared on an episode of Spike's Bar Rescue.[107]

- During the Versuz battle of the Bay between Bay Area legends, E-40 and Too Short. Too Short shouted out the Bayview community.[108]

Notable residents

Music

- 11/5, defunct gangsta rap group from the Oakdale public housing projects in Hunters Point

- Eric Melvin, guitarist for NOFX

- RBL Posse, gangsta rap group from Harbor Road public housing projects in Hunters Point

- Ramirez, punk rapper, from Bayview-Hunter's Point signed to New Orleans based label G*59 Records.[109][110]

- Prezi,[111] rapper from Hunter's Point

- Cindy Herron, singer and founding member of En Vogue.

- Martin Luther McCoy, actor, guitarist and musician.

- Larry June, rapper from Hunter's Point.

- Jordan Gomes aka Stunnaman02, rapper and actor from Bayview.[112]

Film and television

- Kevin Epps, filmmaker best known for the documentary Straight Outta Hunters Point[113][114]

- Terri J. Vaughn (born 1969), actress born and raised in Bayview–Hunters Point[115]

Sports and fitness

- Frank "Lefty" O'Doul (1897–1969), an american professional baseball player born and raised in the Bayview.

- Jimmy Lester (1944-2006), former boxer known as the "Bayview Blaster"[116]

- Dion Jordan (born 1990), a professional NFL player born and raised in the Bayview.[117]

- Desmond Bishop, professional NFL player

- Stevie Johnson (born 1986), NFL wide receiver, born and raised in Hunters Point before moving to Fairfield, CA

- Eric Wright (born 1985), NFL player, cornerback for the San Francisco 49ers

- Sam Jordan (1925-2003), professional boxer, politician and founder of Sam Jordan's Bar.[118][119]

- Donald Strickland (born 1980), NFL player, free agent cornerback who played for the San Francisco 49ers, Indianapolis Colts and New York Jets

- Maria Kang (born 1980), fitness advocate, coach, blogger and founder of the "No Excuse Mom" movement.

Medical

- Stephanie Dixon, one half of doula duo, Bare With Me Duo and birth worker.[120]

- Deundra Hundon, one half of doula duo, Bare With Me Duo and birth worker.

Politics and activism

- Espinola Jackson (1933-2016), a member of the Muwekma Ohlone tribe and heralded as "Bayview's greatest activist".[121][122]

- Elouise Westbrook (1915-2011) activist[123]

- Mary L. Booker (1931-2017), civil rights activist[124][125][126]

- Big Five of Bayview, environmental and community activist

- Christopher Muhammad, Bay Area Minister of the Nation of Islam

- Marie Harrison (1948-2019), Bayview environmental activist.[127]

- Shamann Walton, resident of the Bayview and district 10 supervisor.

See also

References

- ^ a b "Statewide Database". UC Regents. Archived from the original on February 1, 2015. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "California's 12th Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC.

- ^ a b "Bayview–Hunters Point: Area B Survey" (PDF). San Francisco Redevelopment Agency. 11 February 2010: 4.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c "San Francisco Neighborhoods: Socio-Economic Profiles; American Community Survey 2005–2009". San Francisco Planning Department. May 2011: 8. Archived from the original on 2011-08-11. Retrieved 2011-09-20.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "History of Bayview Hunters Point". bvoh.org. BVOH. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Upton, John (June 3, 2010). "Hunters Point Naval Shipyard development Faces Vote". The San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 13 August 2013.

- ^ Scott, Mel (September 1985). The San Francisco Bay Area: A Metropolis in Perspective (2nd ed.). University of California Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-520-05512-4.

- ^ a b c O'Brien, Tricia (August 1, 2005). San Francisco's Bayview Hunters Point. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 7–9. ISBN 978-0-7385-3007-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Dillon, Lindsey (2 August 2011). "Redevelopment and the Politics of Place in Bayview–Hunters Point". Institute for the Study of Social Change, UC Berkeley: 9–34.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ De Costa, Francisco. "THE MUWEKMA OHLONE AND BAYVIEW". www.franciscodacosta.com/. Francisco De Costa. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Casey, Conor (2007). "San Francisco's "Butchertown" in the 1920s and 1930s: A Neighborhood Social History (Volume 18, Number 1)". The Argonaut (Spring).

- ^ Rechtschaffen, Clifford (1995–1996). "Fighting Back against a Power Plant: Some Lessons from the Legal and Organizing Efforts of the Bayview–Hunters Point Community". Hastings W.-Nw. J. Envt'l L. & Pol'y: 407.

- ^ "Hunters Point power plant demolished". ABC News. 19 September 2008. Archived from the original on 12 October 2012. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Merchants of Butchertown". Bay View. Bay View. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "History of Bayview Hunters Point". bvoh.org. BVOH. Retrieved 1 July 2020.

- ^ Joe, Ellen; Schwartz, Sara L.; Austin, Michael J. (2008). "The Bayview Hunters Point Foundation for Community Improvement: A Pioneering Multi-Ethnic Human Service Organization (1971–2008)". Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work. 8 (1–2). University of California, Berkeley: Mack Center on Nonprofit Management in the Human Services: 235–52. doi:10.1080/15433714.2011.540458. PMID 21416440. S2CID 205888979.

- ^ Jeffries, Amy (2006). "A Brief History of Bayview–Hunters Point". Profile:Bayview Hunters Point. UC Berkeley Graduate School of Journalism. Archived from the original on 2011-06-10.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Solnit, Rebecca (29 November 2010). Infinite City: A San Francisco Atlas. ISBN 9780520262492. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ a b "Former Naval Shipyard Hunters Point". BRAC Program Management Office. Department of the Navy. Archived from the original on 2011-01-19. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- ^ "Treasure Island Naval Station-Hunters Point Annex Superfund site progress profile". EPA. Archived from the original on June 16, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ "Treasure Island Naval Station-Hunters Point Annex Superfund site partial deletion narrative". EPA. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ "Ohlone people to SF Planning Dept: Follow the law, protect ancient village sites at Candlestick Point, Hunters Point Shipyard". www.sfbayview.com. San Francisco Bay View. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ^ "Hunters Point Is San Francisco's Radioactive Basement". Vice.com. VICE. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "Final Environmental Impact Statement for the Disposal and Reuse of Hunters Point". Google Books. 2000. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ KQED, 1963, Take This Hammer, San Francisco Bay Are Area Television Archives

- ^ Rucker, Walter C.; Upton, James N. (November 30, 2006). Encyclopedia of American Race Riots. Greenwood. pp. 583–4. ISBN 978-0-313-33301-9.

- ^ "San Francisco Order Restored". Beaver County Times. UPI. 28 September 1966. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ News, KRON. "Robert Kennedy visits with Black Community II". diva.sfsu.edu. KRON News. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ McCormick, Erin (January 14, 2008). "Bayview revitalization comes with huge price to black residents". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-09-28.

- ^ "San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA, Muni, Sustainable Streets)". Sfmta.com. 2012-12-26. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ Crumpacker, John (November 14, 2006). "'Shocked' S.F. group drops bid for 2016 Olympics". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Selna, Robert (November 10, 2006). "49ERS ON THE MOVE / Stadium plan stuns and disappoints / HUNTERS POINT: Area residents see York's decision as one more broken promise". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Cadei, Emily (1 July 2014). "Kofi Bonner: Community Building ? for Profit". Ozymandias. Retrieved 19 July 2014.

- ^ Barba, Michael. "Underenrollment at Bayview schools causes 'ripple effect' across SF". www.sfexaminer.com/. SF Examiner. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ Epstein, Jaron. "Warriors dedicate Willie Brown Basketball Court". oaklandpost.org. Oakland Post. Retrieved 19 July 2018.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "94124 Home Prices and Home Values – Zillow Local Info". Zillow.com. 2012-12-16. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "94124 Zip Code (San Francisco, California) Profile – homes, apartments, schools, population, income, averages, housing, demographics, location, statistics, sex offenders, residents and real estate info". City-data.com. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2011-11-08.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c Browne, Jaron (16 September 2011). "Court blocks Hunters Point Shipyard redevelopment until Navy completes toxic cleanup". San Francisco Bay View National Black Newspaper.

- ^ "The kill zone". www.sfgate.com.

- ^ a b Sward, Susan (December 16, 2001). "THE KILLING STREETS / A Cycle of Vengeance / BLOOD FEUD / In Bayview–Hunters Point, a series of unsolved homicides has devastated one of S.F.'s most close-knit communities". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "SFGov : Southeast Community Facility Commission". Sfgov3.org. 2012-12-04. Archived from the original on 2012-08-13. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "SFGov : Southeast Food Access (SEFA) Workgroup". Sfgov3.org. Archived from the original on 2012-04-22. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ Waldholz, Rachel (May 30, 2011). "Greening a city ... and pushing other colors out". High Country News. ProQuest 870401460.

- ^ Vega, Cecilia M. (January 15, 2008). "Guns, crack cocaine fuel homicides in S.F. – 98 killings in 2007". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2011-08-02.

- ^ Bundy, Trey (August 7, 2011). "A Neighborhood Is Shaken by a Violent Death". New York Times. p. A21A.

- ^ Tesco signs deal for Fresh & Easy store in Bayview by J.K. Dineen, San Francisco Business Times, December 11, 2007, access date June 28, 2008

- ^ a b Coté, John (August 25, 2011). "After years, Bayview will finally get full-service grocery store". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "USDA ERS – Go to the Locator". Ers.usda.gov. 2012-08-23. Archived from the original on 2013-02-27. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ Selna, Robert (April 1, 2008). "Best and worst of City Hall". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ Vickers, Emma (April 12, 2013). "Tesco expected to scrap struggling US grocery chain Fresh & Easy". The Guardian.

- ^ "Straight Outta Hunters Point". 1 October 2003 – via www.imdb.com.

- ^ Wagner, Venise (June 29, 2001). "Straight outta Hunters Point / Kevin Epps's bleak documentary shows the disintegration of a place he has called home for 30 years". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "Willie Mays Fundraising for Bayview Hunters Point". diva.sfsu.edu. Diva SFSU. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ India Basin Neighborhood Association Archived November 23, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Quesada Gardens". Quesada Gardens. Archived from the original on 2013-03-02. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "About Us". Lejyouth.org. Archived from the original on 2012-11-08. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Bayview Merchants Association". bayviewmerchants.org. 2006-05-28. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Bayview Footprints". bayviewfootprints.org. Archived from the original on 2010-01-13. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Greenaction". greenaction.org.

- ^ "NEN Awards". Empowersf.org. Archived from the original on 2012-03-15. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Bayview :: San Francisco Public Library". Sfpl.org. 2011-04-02. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "The Grand Plan And Aesthetics For Candlestick/Hunters Point". SocketSite. November 12, 2009. Retrieved November 12, 2009.

- ^ a b Paddock, Richard (April 30, 2010). "Vision for Transforming Hunters Point Comes Before Supervisors". New York Times. Retrieved December 6, 2010.

- ^ a b Carlsen, Robert (July 16, 2010). "SF Supes Approve EIR for Lennar's Hunters Point Plan". California Construction. Archived from the original on 22 July 2010. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Wildermuth, John (July 15, 2010). "Hunters Point shipyard plan wins key approval". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Roberts, Chris (Sep 21, 2016). "Faked Soil Samples Throw Hunters Point Shipyard Development into Disarray". San Francisco Magazine. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ "I AM BAYVIEW". mccalman.co. George McCalum. Retrieved 20 June 2018.

- ^ "critics-say-bayview-portrait-series-promotes-gentrification". hoodline.com. Hoodline. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Mitchell, Meaghan (January 31, 2017). "Third Street poles get red, black & green stripes in honor of Bayview's Black heritage". www.sfbayview.com. The Bay View. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ JR, The Minister of Information. "AeroSoul3 exhibition: an interview wit' curator Refa-1". sfbayview.com. San Francisco Bay View. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ "The Fire Next Time II". www.artandarchitecture-sf.com. Architecture SF. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ "Small-Business Success Story: Black Girls Code". www.kiplinger.com. Retrieved 2020-05-01.

- ^ "thePoint | Affordable Artist Studios at San Francisco's Hunters Point Shipyard & Islais Creek". Thepointart.com. 2011-06-17. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ http://www.zaccho.org

- ^ Betcher, Jeffrey (2011-04-27). "You can call it "the Opera House"". It's what community looks like... Retrieved 2020-06-21.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - South San Francisco Opera House - Draft" (PDF). California State Parks Office of Historic Preservation.

- ^ http://bvoh.org/news/pressReleases/pdf/BVOH_Governor%27s_Award_10-28-2011.pdf[permanent dead link]

- ^ "San Francisco Landmark #63: Quinn House". Noehill.com. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ Alvis Hendley (2005-06-09). "San Francisco Landmark 60: Hunters Point Springs-Albion Brewery". Noehill.com. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "San Francisco Landmark #61: Sylvester House". Noehill.com. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Steve McQueen visits Bayview Hunters Point Pool". diva.sfsu.edu. Diva SFSU. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Fimrite, Peter (August 24, 2011). "Clapper rails discovered nesting in SF". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ^ "SF EcoCenter Wins EPA Award". The Bay Citizen. Archived from the original on 2012-04-04. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ Harshaw, Pendarvis. "Honoring Lost Leaders at 'All My Usos,' a Polynesian Community BBQ in Bayview". KQED. KQED. Retrieved 25 June 2020.

- ^ "Speakeasy Ales and Lagers". Goodbeer.com. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Radio Africa & Kitchen". Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Old Skool Cafe". Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Limón Rotisserie". Retrieved 2016-05-24.

- ^ "Brown Sugar Kitchen". Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Frisco Fried: Down Home San Francisco Style Soul Food". Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "Welcome to San Francisco Wholesale Produce Market". Sfproduce.org. Retrieved 2012-12-31.

- ^ "San Francisco's first black woman-owned dispensary nears grand opening in Bayview". Hoodline. Hoodline. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Pape, Allie. "CDXX, A Bayview Neighborhood Spot". Eater SF. Eater SF. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Corner Cafe Closed". Yelp. Yelp. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Welsh, David. "San Francisco post offices spared the ax". Workers. Workers.org. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- ^ "Pride in an Industrial Past". theshipyard.com. theshipyard.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Welsh, Alex. "San Francisco's Forgotten Neighborhood of Bayview-Hunters Point". slate.com. Slate.com. Retrieved 11 June 2018.

- ^ "LARRY JUNE -SMOOTHIES IN 1991 (MUSIC VIDEO) (PROD BY Julian Avila)". YouTube. Larry June. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Marcus Orelias ~ BLACKOUTS (Feat. Stephan Marcellus) [Official Video]". YouTube. Marcus Orelias. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Out That Window - Stunnaman02 (Prod by NiloBeats) (Shot by Bay2Nyc)". YouTube. Jordan Gomes. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ "Point of Pride (2014)". imdb.com. IMDb.com. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "With 'Straight Outta Hunters Point 2' Filmmaker Kevin Epps Goes Home Again". KQED.com. KQED. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Jones, Chad. "'A Choice of Weapons': Film about Bayview". SFGATE.com. SF GATE. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "Forgotten Planet Fridays at 10 PM ET/7 PM PT". press.discovery.com. Discovery Network. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "Stress Test At Sam Jordan's - Bar Rescue, Season 5". Youtube.com. Paramount Network. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "E-40 vs Too Short Verzuz Battle". YouTube. Verzuz / YouTube. Retrieved 12 January 2021.

- ^ "THE BREAK PRESENTS: Suicideboys". XXL.com. XXL Magazine. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "G*59 Records". g59records.com. G59 Records. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ "Talking With Prezi, the Rapper Pledging to 'Do Better' for Hunters Point". KQED.com. KQED. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ^ Shakur, Prince. "The Last Black Man in San Francisco Reveals the Complexity of Masculinity". Yahoo News. Yahoo. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- ^ Suzdaltsev, Jules. "Hunters Point Is San Francisco's Radio Active Basement". Vice. Retrieved 12 February 2015.

- ^ "Straight Outta Hunters Point". Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on 6 March 2016.

- ^ Burrell, Y'Anad. "Terri J. Vaughn's, Take Wings Foundation Gala, A Huge Success; UPN A Proud Supporter". www.prweb.com. Retrieved 4 October 2014.

- ^ Fitzgerald, Tom. "JIMMY LESTER / 1944-2006 / 'Bayview Blaster' contended, but never got a title fight". SFGATE. SF GATE. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- ^ Buestad, Connor. ""The Silent Assassin" - Bayview Native Dion Jordan Quietly Shines for No. 3 Oregon". section925. Section 925. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ Walsh, Diana. "Sam Jordan -- popular Bayview tavern owner". sfgate. SF Gate. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ Bricker, Hannah. "Sam Jordan's Bar, Named San Francisco Landmarks". www.huffingtonpost.com. Huffington Post. Retrieved 9 June 2018.

- ^ McBride, Ashley. "With black babies, moms at high risk in SF, project pairs them with caregivers". www.sfchronicle.com. SF Chronicle. Retrieved 11 April 2019.

- ^ "Mayor Lee's Statement on Passing of Dr. Espanola Jackson". sfmayor.org. SF Mayor. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ Moore, La Vaughn B. "In celebration of the charismatic life of Sister Espanola Jackson, a born leader and chosen woman". sfbayview.com. SF Bayview. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

- ^ "28 African-Americans with ties to the Bay Area who made history". sfgate.com. SF Gate. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "RIP: Mary L. Booker, Civil Rights Activist, Bayview Community Theater Leader". www.hoodline.com. hoodline.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Mary Booker". moadsf.org. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018.

- ^ "Mary L. Booker, leader of Bayview community theater, dies". sfgate.com. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Rubenstein, Steve. "Marie Harrison, Hunters Point environmental activist, dies". Sf Chronicle. SF Chronicle. Retrieved 24 June 2020.

External links

- Profile: Bayview–Hunters Point 2006 11-part series UC Berkeley School of Journalism

- Community-building through informal resident-led groups known as Quesada Gardens Initiative

- Community's user-generated calendar of events created by Footprints community network

- Bayview Merchants' Association

- Bay View Newspaper

- Bayview MAGIC – Community of color collaborative

- Historic Hunters Point in pictures

- India Basin Neighborhood Association

- Map of India Basin

- Islais Creek History Neighborhood Parks Council

- Hunters Point infant mortality rate is comparable to Bulgaria

- Hunters Point Shipyard redevelopment

- 1966 Hunters Point riot

- Review of a documentary film about Hunters Point

- Alternative economic development for Bayview–Hunters Point

- Community Window on the Shipyard, an archive of Shipyard-related documents

- Literacy for Environmental Justice, a local organization working on Environmental Justice issues in Hunters Point

- Artists at Hunters Point Shipyard

- Department of the Navy BRAC Program Management Office