Swat District

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Swat

سوات | |

|---|---|

Springtime photograph of the Swat River running through the valley, May 2015 | |

| Nickname: Switzerland of the East[1] | |

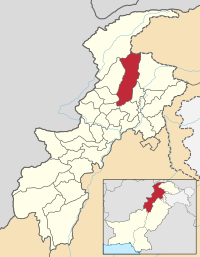

Swat District, highlighted red, shown within the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | |

| Coordinates: 35°12′N 72°29′E / 35.200°N 72.483°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| Capital | Saidu Sharif |

| Largest city | Mingora |

| Area | |

| • District | 5,337 km2 (2,061 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • District | 2,309,570 |

| • Density | 430/km2 (1,100/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 695,900 |

| • Rural | 1,613,670 |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| Area code | Area code 0946 |

| Languages (1981)[3] | |

Swat District (Pashto: سوات ولسوالۍ, pronounced [ˈswaːt̪]) is a district in the Malakand Division of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Centred upon the upper portions of the Swat River, the modern-day district was a major centre of early Buddhism under the ancient kingdom of Gandhara, due to which a strong presence of Buddhist cultural influence exists in the region. Swat was home to Hinduism and later Gandharan Buddhism until the 10th century, after which the area predominantly came under Muslim control and Islamic influence.[4][5] Until 1969, Swat was part of the Yusafzai State of Swat, a self-governing princely state that was inherited by Pakistan following its independence from British rule. The region was seized by the Tehrik-i-Taliban in late-2007,[6] and its highly-popular tourist industry was subsequently decimated until Pakistani control was re-established in mid-2009.[7]

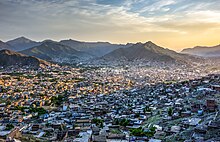

Swat's capital is the city of Saidu Sharif, although the largest city and main commercial centre is the nearby city of Mingora.[8][better source needed] With a population of 2,309,570 per the 2017 national census, Swat is the 15th-largest district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. With the exception of the uppermost regions of the valley, which are inhabited by ethnic Kohistanis, Swat is mostly inhabited by Yusufzai Pashtuns, who arrived in the region from the southern Kabul Valley in 16 CE.[5]

The average elevation of Swat is 980 m (3,220 ft),[5] resulting in a considerably cooler and wetter climate compared to the rest of Pakistan. With lush forests, verdant alpine meadows, and snow-capped mountains, Swat is one of the country's most popular tourist destinations.[9][10]

Etymology

The name "Swat" is of Sanskrit origin. One theory derives it from Suvastu, the ancient name of the Swat River (Suastus in Greek literature);[11] Suvastu (lit. 'clear azure water') is attested in the earliest Sanskrit-language Hindu text, the Rigveda.[12] Another theory derives the word Swat from the Sanskrit word "Shveta" (lit. 'white'), also used to describe the clear water of the Swat River.[11]

History

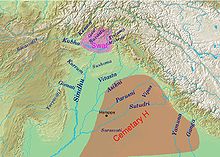

The earliest recorded history of the region, preserved through the oral tradition, was the settlement and societies of the Indo-Aryan peoples. According to E. R. Leach: "Swat lies on the edge of the Indian world".[13] These Indo-Aryan tribes of the Rigveda created the earliest settlement and cultures in Swat. Some of these Indo-Aryan settlements, launched from Swat, gave rise to or influenced the early cultures of ancient India, such as the Cemetery H culture, Copper Hoard culture and Painted Grey Ware culture. Later movements of the Indo-Aryan tribes saw the emergence of ethnic Nuristani and Dardic populations.[14]

In 327 BC, Alexander the Great fought his way to Odigram and Barikot and stormed their battlements; in Greek accounts, these towns are identified as Ora and Bazira. This area was then ruled over by the Indo-Greek Kingdom for centuries. Around the second century BC, the area was occupied by Buddhists, who were attracted by the peace and serenity of the land. There are many remains that testify to their skills as sculptors and architects. Some time later, ethnic Swatis entered the area along with Sultans from Kunar (present-day Afghanistan). The formal establisher of the Yousafzai State of Swat's last official ruling family before the princely state's merger with Pakistan was the Muslim saint Akhund Abdul Gaffur, more commonly known as Saidu Baba.[15][16]

Buddhist heritage

The early presence of Buddhism in this region is said to have come via the settlement of Oddiyana, where Tantric Buddhism flourished under Indrabhuti, the king of Swat in the early eighth century and one of the original Siddhas. However, there is an old and well-known scholarly dispute as to whether Oddiyana was located in the Swat Valley of northwestern Pakistan, the eastern Indian state of Odisha, or somewhere else. Padmasambhava (flourished eighth century AD), the semi-legendary Indian Buddhist mystic who introduced Tantric Buddhism to Tibet was, according to tradition, native to Oddiyana.[17] He is revered as the second Buddha in Tibet, and is said to have been the son of Indrabhuti. Lakshminkaradevi, Indrabhuti's sister, is also said to have been an accomplished Siddha in the ninth century AD.[18]

The ancient kingdom of Gandhara, the Purushapura valley and the adjacent hilly regions of Swat, Buner, Dir, and Bajaur, were one of the earliest centres of Buddhist culture following the reign of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in the third century BC. The name Gandhara's earliest literary occurrence is in the Rigveda, which is usually synonymous with the region.[19][page needed]

The Gandhara school is credited with having the first representations of the Buddha in human form, rather than symbolically.[citation needed]

Hindu Shahi

After an early Buddhist phase, Hinduism reasserted itself, and by the time of the Muslim conquests (c. 1000 AD), the population in the region was predominantly Hindu.[16]: 19

Prior to the Abbasid Caliphate's takeover of the region, Swat was ruled by the Hindu Shahi dynasty, who built an extensive array of temples and other architectural buildings, of which ruins remain today. Sanskrit is believed to have been the lingua franca of the locals during this time.[20] Hindu Shahi rulers built fortresses to guard and tax the commerce through this area, and ruins dating back to their rule can be seen on the hills at the southern entrance of Swat, at the Malakand Pass.[21]

Taliban destruction of Buddhist relics

The Swat Valley, located in present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province, has many Buddhist carvings, statues, and stupas. The town of Jehanabad contains a Seated Buddha statue.[22][dead link] Kushan-era Buddhist stupas and statues in the Swat Valley were demolished by the Taliban, and after two further attempts,[23][dead link] the Jehanabad Buddha's face was blown up using dynamite.[24][25] Only the Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, which were also demolished by the Taliban, were larger than the Buddha statue in Swat, Pakistan.[26] The Government of Pakistan failed to safeguard the Buddha statue after the Taliban's initial attempts at destroying the Buddha took place, although they did not cause permanent harm; when the second Taliban attack took place shortly afterwards, the statue's feet, shoulders, and face were demolished.[27] The Taliban and looters subsequently destroyed many of Pakistan's Buddhist artifacts, which dated back to the seventh-century BC Gandhara Buddhist civilization.[28] The Taliban deliberately targeted Gandhara Buddhist relics for destruction.[29] Gandhara artifacts remaining from the demolitions were thereafter plundered by thieves and smugglers.[30] In 2009, the Archbishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Lahore, Lawrence John Saldanha, wrote a letter to the Pakistani government denouncing the Taliban's activities in the Swat Valley, including their destruction of ancient Buddha statues and their attacks on Christians, Sikhs, and Hindus.[31] The Buddha statue in Swat was repaired by a group of Italians in a nine-year-long process following the demolition.[32]

Geography

Swat is surrounded by Chitral, Upper Dir and Lower Dir to the west, Gilgit-Baltistan to the north, and Kohistan, Buner and Shangla to the east and southeast, respectively. The former tehsil of Buner was granted the status of a separate district in 1991.[33] The Swat Valley is located in northern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and is enclosed by the Himalayas and Hindu Kush. Consequently, Swat's physical terrain can be divided into mountainous ranges and plains.

Plains

The length of the valley from Landakay to Gabral is 91 miles. Two narrow strips of plains run along the banks of Swat River from Landakay to Madyan. Beyond Madyan in Kohistan-e-Swat, the plain is too little to be mentioned. So far as the width concerns, it is not similar, it varies from place to place. We can say that the average width is 5 miles. The widest portion of the valley is between Barikot and Khwaza Khela. The widest viewpoint and the charming sight where a major portion of the valley is seen is at Gulibagh on the main road, which leads to Madyan.

Economy

Approximately 38% of economy of Swat depends on Tourism[34] and 31% depends on Agriculture.[35]

Agriculture

Gwalerai village located near Mingora is one of those few villages which produces 18 varieties of apples due to its temperate climate in summer. The apple produced here is consumed in Pakistan as well as exported to other countries. It is known as ‘the apple of Swat’.[36] Swat is famous for peach production mostly grown in the valley bottom plains and accounts for about 80% of the peach production of the country. Mostly marketed in the national markets with a brand name of "Swat Peaches". The supply starts from April and continues till September because of a diverse range of varieties grown.

Demographics

The population of Swat District is 2,309,570 as per the 2017 census, making it the third-largest district of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa after Peshawar District and Mardan District.[37] Swat is populated mostly by mainly Yousafzai Pashtuns and Kohistani communities. The language spoken in the valley is Pashto, with a minority of Torwali and Kalami speakers in the Swat Kohistan region of Upper Swat.

Education

According to the Alif Ailaan Pakistan District Education Rankings for 2017, Swat District with a score of 53.1, is ranked 86 out of 155 districts in terms of education. Furthermore, school infrastructure score is 90.26 ranking the district at number 31 out of 155 districts.[38]

Tribes

Administrative divisions

The District of Swat is subdivided into 7 tehsils:[40]

Each tehsil comprises certain numbers of union councils. There are 65 union councils in the district: 56 rural and 9 urban.

According to the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Local Government Act, 2013,[41] a new local governments system was introduced, in which Swat District is included. This system has 67 wards, in which the total amount of village councils are around 170, while neighbourhood councils number around 44.[42]

Politics

The region elects three male members of the National Assembly of Pakistan (MNAs), one female MNA, seven male members of the Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (MPAs)[43] and two female MPAS. In the 2002 National and Provincial elections, the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal, an alliance of religious political parties, won all the seats.

Notable people

- Malala Yousafzai

- Ziauddin Yousafzai

- Mubarika Yusufzai

- Wāli of Swat

- Jamila Ahmad

- Sabra Shakir is a Pakistani politician who had been a Member of the Provisional Assembly of Pakistan from 2002 to 2007.

- Anwar Ali

- Nazia Iqbal

- Ghazala Javed

- Afzal Khan Lala

- Haider Ali Khan

- Malak Jamroz Khan

- Rahim Khan

- Ancestors of Bollywood actor Salman Khan hail from Swat Valley

- Nasirul Mulk

- Badar Munir

- Murad Saeed

- Shaheen Sardar Ali

- Rahim Shah

- Sherin Zada

- Rafi-ul-mulk/kaki khan

See also

References

- ^ Steven stee 2013.

- ^ "DISTRICT AND TEHSIL LEVEL POPULATION SUMMARY WITH REGION BREAKUP: KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. 3 January 2018. Retrieved 23 April 2018.

- ^ Stephen P. Cohen (2004). The Idea of Pakistan. Brookings Institution Press. p. 202. ISBN 0815797613.

- ^ East and West, Volume 33. Istituto italiano per il Medio ed Estremo Oriente. 1983. p. 27.

According to the 13th century Tibetan Buddhist Orgyan pa forms of magic and Tantra Buddhism and Hindu cults still survived in the Swāt area even though Islam had begun to uproot them (G. Tucci, 1971, p. 375) ... The Torwali of upper Swāt would have been converted to Islam during the course of the 17th century (Biddulph, p. 70 ).

- ^ a b c Mohiuddin, Yasmeen Niaz (2007). Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781851098019.

- ^ Abbas, Hassan (24 June 2014). The Taliban Revival: Violence and Extremism on the Pakistan-Afghanistan Frontier. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300178845.

- ^ Craig, Tim (9 May 2015). "The Taliban once ruled Pakistan's Swat Valley. Now peace has returned". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 11 February 2018.

- ^ "Pakistan troops seize radical cleric's base: officials" Archived 2 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Agence France Presse article, 28 November 2007, accessed same day

- ^ Khaliq, Fazal (17 January 2018). "Tourists throng Swat to explore its natural beauty". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "The revival of tourism in Pakistan". Daily Times. 9 February 2018. Retrieved 12 February 2018.

- ^ a b Sultan-i-Rome (2008). Swat State (1915–1969) from Genesis to Merger: An Analysis of Political, Administrative, Socio-political, and Economic Development. Oxford University Press. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-19-547113-7.

- ^ Susan Whitfield (2018). Silk, Slaves, and Stupas: Material Culture of the Silk Road. University of California Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0-520-95766-4.

- ^ Leach, E. R. (1960). Aspects of Caste in South India, Ceylon and North-West Pakistan. ISBN 9780521096645.

- ^ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. ISBN 9781884964985.

- ^ S.G. Page 398 and 399, T and C of N.W.F.P by Ibbetson page 11 etc

- ^ a b Fredrik Barth, Features of Person and Society in Swat: Collected Essays on Pathans, illustrated edition, Routledge, 1981

- ^ Hoiberg, Dale (2000). Students' Britannica India. ISBN 9780852297605. Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh: Up to 8th Century A.D., by Omacanda Hāṇḍā Edition: illustrated Published by Indus Publishing, 1994 Page 89

- ^ Architecture and Art Treasures in Pakistan By F. A. Khan, published by Elite Publishers, 1969

- ^ Sorrow and Joy Among Muslim Women The Pushtuns of Northern Pakistan By Amineh Ahmed Published by Cambridge University Press, 2006 Page 21.

- ^ Swat: An Afghan Society in Pakistan: Urbanisation and Change in Tribal Environment By Inam-ur-Rahim, Alain M. Viaro Published by City Press, 2002 Page 59

- ^ Jeffrey Hays. "EARLY HISTORY OF BUDDHISM". Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Taliban defeated by the quiet strength of Pakistan's Buddha". Times of India.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Malala Yousafzai (8 October 2013). I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban. Little, Brown. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-316-32241-6.

The Taliban destroyed the Buddhist statues and stupas where we played Kushan kings haram Jehanabad Buddha.

- ^ Wijewardena, W.A. (17 February 2014). "'I am Malala': But then, we all are Malalas, aren't we?". Daily FT.

- ^ "Attack on giant Pakistan Buddha". BBC News. 12 September 2007. Archived from the original on 15 December 2020.

- ^ "Another attack on the giant Buddha of Swat". AsiaNews.it. 10 November 2007.

- ^ "Taliban and traffickers destroying Pakistan's Buddhist heritage". AsiaNews.it. 22 October 2012.

- ^ "Taliban trying to destroy Buddhist art from the Gandhara period". AsiaNews.it. 27 November 2009.

- ^ Rizvi, Jaffer (6 July 2012). "Pakistan police foil huge artefact smuggling attempt". BBC News.

- ^ Felix, Qaiser (21 April 2009). "Archbishop of Lahore: Sharia in the Swat Valley is contrary to Pakistan's founding principles". AsiaNews.it.

- ^ Khaliq, Fazal (7 November 2016). "Iconic Buddha in Swat valley restored after nine years when Taliban defaced it". DAWN.

- ^ 1998 District Census report of Buner. Census publication. Vol. 98. Islamabad: Population Census Organization, Statistics Division, Government of Pakistan. 2000. p. 1.

- ^ https://korbah.com/hotels/?location_name=Swat&location_id=9694&start=&end=&date=19%2F01%2F2020+12%3A00+am-20%2F01%2F2020+11%3A59+pm&room_num_search=1&adult_number=1&child_number=0&price_range=0%3B23250&taxonomy%5Bhotel_facilities%5D=

- ^ Chief Editor. "Swat Economy". kpktribune.com. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ^ Amjad Ali Sahaab. "Gwalerai — The little village behind Swat's famous apples". dawn.com. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- ^ "Swat District – Population of Cities, Towns and Villages 2017–2018". Pakistan's Political Workers Helpline. 27 May 2018. Retrieved 20 January 2019.

- ^ "Pakistan District Education Rankings 2017" (PDF). elections.alifailaan.pk. Alif Ailaan. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- ^ Claus, Peter J.; Diamond, Sarah; Ann Mills, Margaret (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 447. ISBN 9780415939195.

- ^ http://lgkp.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/Village-Neighbourhood-Councils-Detatails-Annex-D.pdf

- ^ http://lgkp.gov.pk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Local-Government-Elections-Rules-2013.pdf

- ^ "Village/Neighbourhood Council". Retrieved 27 January 2016.

- ^ "Constituencies and MPAs – Website of the Provincial Assembly of the N-W.F.P". Archived from the original on 28 December 2007.

External links

Bibliography

- Malala Yousafzai (8 October 2013), I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban, Little, Brown, ISBN 9780316322416

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)