History of the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) has been the governing party of the Republic of South Africa since 1994. The ANC was founded on 8 January 1912 in Bloemfontein and is the oldest liberation movement in Africa.[1]

Called the South African Native National Congress until 1923, the ANC was founded as a national discussion forum and organised pressure group, which sought to advance black South Africans’ rights at times using violent and other times diplomatic methods. Its early membership was a small, loosely centralised coalition of traditional leaders and educated, religious professionals, and it was staunchly loyal to the British crown during the First World War.[2] It was in the early 1950s, shortly after the National Party’s adoption of a formal policy of apartheid, that the ANC became a mass-based organisation.[2] In 1952, the ANC's membership swelled during the uncharacteristically militant Defiance Campaign of civil disobedience, towards which the ANC had been led by a new generation of leaders, including Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, and Walter Sisulu. In 1955, it signed the Freedom Charter, which – along with the subsequent Treason Trial – cemented its so-called Congress Alliance with other anti-apartheid groups.

At the turn of the decade, a series of significant events in quick succession changed the course of the movement. First, in 1959, a group of dissidents broke away from the ANC to form the rival Pan Africanist Congress, objecting to the ANC's new programme of multi-racialism as embodied in the Freedom Charter. This was one of two significant splits in the ANC on the basis of its racial policies – in 1975, the so-called Gang of Eight was expelled for objecting to the ANC's 1969 decision to open its membership to all races. The second major shift came when in March 1960, following the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC was banned, marking the beginning of a period of escalating state repression. Forced underground, the ANC and South African Communist Party (SACP) founded Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), which was to become the ANC's military wing. Announcing the beginning of an armed struggle against apartheid, MK embarked upon a sabotage campaign.

By 1965, pursuant to the imprisonment of many of its top leaders in the Rivonia Trial and Little Rivonia Trial, the ANC was forced into exile. It remained in exile until it was unbanned in 1990. For most of this period, the ANC was led by Tambo, headquartered first in Morogoro, Tanzania, and then in Lusaka, Zambia, and primarily supported by Sweden and the Soviet Union.[3] Its exile was marked by an increasingly close alliance with the SACP, as well as by periods of significant unrest inside MK, including the Mkatashinga mutinies in 1983–84. Throughout these years, the ANC's central objective was the overthrow of apartheid, by means of the "Four Pillars": armed struggle; an internal underground; popular mobilisation; and international isolation of the apartheid regime.[3] After the 1976 Soweto uprising, MK received a large influx of new recruits, who were used to escalate the armed struggle inside South Africa; ANC attacks, for the first time, killed large numbers of civilians.[4] Yet even as the armed attacks continued, the ANC embarked upon secret talks about a possible negotiated settlement to end apartheid, beginning with a series of meetings with civil society and business leaders in the mid-1980s, and complemented by Mandela's own meetings with state officials during his imprisonment.

The ANC was unbanned on 2 February 1990, and its leaders returned to South Africa to begin formal negotiations. Following his release, Mandela was elected president of the ANC at its 48th National Conference in 1991. Pursuant to the 1994 elections, which marked the end of apartheid, the ANC became the majority party in the national government and most of the provincial governments, and Mandela was elected national president. The ANC has retained control of the national government since then.

Origins

The organisation was founded as the South African Native National Congress (SANNC) in Bloemfontein on 8 January 1912, in the aftermath of the foundation of the Union of South Africa and not long before the passage of the Natives Land Act.[5] Zulu hymns were sung at the founding meeting.[6] The Congress's membership at this early stage has been described as comprising an "elite" of black South African society, especially including chiefs and professionals educated at mission schools.[5] Its founding leaders were John Dube (President), Sol Plaatje (Secretary), and Pixley ka Isaka Seme (Treasurer), of whom historian Tom Lodge says:[6]

These were men who retained close ties with the African aristocracy, the rural chieftaincy, who, while anxious to promote the general advancement and 'upliftment of the race', were also conservatives, concerned with protecting a moral and social order they correctly perceived to be under attack. Congress was intended to function first as a national forum to discuss the issues which affected 'the dark races of the subcontinent', and second as an organised pressure group. It planned to agitate for changes through 'peaceful propaganda', the election to legislative bodies of Congress sympathisers, through protests and enquiries, and finally, through 'passive action or continued movement' – a clear reference to the tactics which were being employed by Gandhi and his followers in the South African Indian community.

The Congress did indeed have moderate objectives and methods during its early years, engaging in what Raymond Suttner calls "the politics of petitioning".[2] For example, in 1914 and 1919, it sent delegations to Britain to request imperial intervention in South Africa to protect the rights of black South Africans.[6] Thereafter, however, its posture changed slightly: in 1919 and 1920, it became involved in an anti-pass campaign and supported striking municipal workers and mineworkers.[6] The pass laws were a consistent target of the Congress over its first few decades, as those laws were gradually extended and entrenched, such as through the 1923 Natives (Urban Areas) Act.[7] Possibly inspired by Mahatma Gandhi's concept of satyagraha,[8] developed only years earlier in South Africa, the Congress protested the pass laws through a (somewhat sporadic) programme of passive resistance.[5]

The 1920s were notable in South Africa for what has been characterised as intensive growth in class consciousness, including the growing popularity of bodies such as the International Socialist League and, after its establishment in 1921, the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA) – a growing number of Congress members were socialists.[6] Such influences had additional scope to operate locally in the early Congress, which was significantly decentralised: the national organisation met only once annually, at the national conference.[2] For another example of decentralisation, membership was officially open only to black men (with women allowed to join only from 1943), but the practice appears to have been different at the local level.[2]

The ANC, having been renamed in 1923, was led by Josiah Gumede from 1927, and in the same year announced that it planned to embark on a course of mass mobilisation, including by constructing local branch memberships. This did not fully materialise, but the ANC did support the CPSA-founded League of African Rights, a body intended to agitate for various civil and political rights, and Gumede was elected its president. However, in late 1929, the ANC overruled Gumede and declined to support the League's mass anti-pass demonstrations. The League collapsed shortly afterwards, and in April 1930 Gumede was voted out of his ANC office.[6] Gumede's successor was Seme, who pursued the support of the traditionalist chiefs and moved ANC policy back to the right. The ANC under Seme has been described as being at "the nadir of [its] influence".[6][2] Relations with the CPSA soured when the ANC refused to support pass-burning demonstrations in Johannesburg in 1930, and the (short-lived) Independent ANC was formed in a split by dissidents from the left-leaning region that is now the Western Cape.[6]

A just and permanent peace will be possible only if the claims of all classes, colours and races for sharing and for full participation in the educational, political and economic activities are granted and recognised.

– Alfred Xuma, foreword to the 1943 African Claims document

However, amid a surge of trade union activity in the 1940s, the ANC experienced a revival and moderate radicalisation[6] under President-General Alfred Bitini Xuma. In response to the publication in 1941 of the Allied Powers' Atlantic Charter, in 1943 the ANC's national conference signed the "African Claims" document.[9] Notably, the document included demands for self-government and for black political rights, thus marking a shift in the ANC's objectives.[5][6] Xuma proved willing to form tactical alliances with the CPSA – he chaired a joint CPSA-ANC anti-pass committee – and with the Indian Congresses (the Transvaal Indian Congress and Gandhi's Natal Indian Congress), who at the time were protesting the Asiatic Land Tenure and Representation Act.[6] On 9 March 1947, the ANC signed a co-operation agreement, the so-called "Three Doctors' Pact",[10] with the Indian Congresses.[5] By that year, the ANC had swelled to a record 5,517 members, more than half of them in the Transvaal. This represented a larger and more informal following than the ANC had had in the past, attracted in particular by large mass meetings it had begun to organise.[6]

Early opposition to apartheid

| Part of a series on |

| Apartheid |

|---|

|

The 1948 general election brought to power the Afrikaner nationalist National Party, which would not be voted out for the next 46 years. The party had campaigned on a platform of apartheid, an explicit policy of institutionalised racial segregation. Upon his election, Prime Minister D. F. Malan set about implementing apartheid, particularly through a series of laws which further restricted the civil, political, and economic rights and freedoms of non-white South Africans. This naturally wrought a significant shift in the agenda and approach of non-white political organisations, including the ANC. Of immediate significance to the ANC (and to the CPSA, which was banned) was the Suppression of Communism Act of 1950, whose notoriously broad definition of communism was used to justify banning orders on several ANC members and leaders, limiting their political activity and freedom of movement.[2] Eleven of the 27 members of the 1952 National Executive Committee (NEC) were banned; and by 1955, 42 ANC leaders, including Walter Sisulu, had been banned.[11]

During the 1950s, while the ANC intensified its domestic programme of protest action, it also began calling in the international arena for sanctions against the apartheid state. In 1958 in Ghana,[12] ANC President Albert Luthuli called for sanctions. The next year, a group of ANC members went into exile in London and launched the British "Boycott South Africa" movement there.[13]

[A]t the time I first joined, the ANC was an organisation of teachers, intellectuals, clergymen – all the elite of African society. Young people were not very much interested in the ANC. They felt it was an organisation of elderly people. As a result, the ANC never became progressive until it was joined by younger people: the Tambos, Mandelas and so on... It was when those young people came into the ANC that there was transformation in so far as the ideology was concerned, because in the past the elderly people believed in demonstrations, reconciliation with the powers that be and so on. They weren't very much interested in action against the government.

– Dan Tloome, ANC NEC member[14]

1949: Youth League putsch

While the state was introducing formal apartheid, the ANC was itself changing by virtue of the rise of a younger generation of activists from the ANC Youth League, including Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, and Oliver Tambo. The League had been formed in 1944 by Anton Lembede and was known for its "Africanist" ideology, closely resembling that later adopted by the Pan Africanist Congress and emphasising indigenous leadership and national self-determination.[6][7] At the ANC's 38th National Conference in December 1949 in Bloemfontein,[15] in a "remarkable putsch", the Youth League successfully campaigned for the replacement of incumbent ANC President Xuma by James Moroka, as well as for the instalment of Sisulu as Secretary-General and for six[6] seats on the ANC NEC.[5] The League tabled a broad and systematic Programme of Action.[16] The Programme explicitly advocated African nationalism and called for the use of grassroots and mass mobilisation techniques – such as strikes, stay-aways, and boycotts – which in the past had been used successfully by other groups, such as the CPSA, but not by the ANC itself.[5]

Thus from 1950 the ANC began to participate more consistently in mass-based action. In 1950, the ANC, under Moroka, supported a May Day stay-away, known as the "People’s Holiday", which led to the deaths of 18 people in clashes between protesters and the police. ANC support for the stay-away was not, however, unanimous – the Youth League, in particular, was concerned that the socialist or internationalist connotations of May Day were at odds with the Africanist position of the Programme of Action.[15] There was broader support for the subsequent "Day of Protest", a stay-at-home on 26 June 1950 organised with the Indian Congress in protest of the May Day shootings and Suppression of Communism legislation.[15]

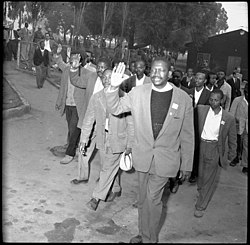

1952–53: Defiance Campaign

In 1951, the ANC, the Indian Congress, and the coloured Franchise Action Council began planning for a joint campaign of mass civil disobedience,[15] inspired by a 1946–48 resistance campaign organised by the Indian Congresses and in turn inspired by campaigns led by Gandhi earlier in the century.[2] This joint campaign became the Defiance Campaign, launched on 26 June 1952. It targeted six laws – including the Group Areas Act, Suppression of Communism Act, and Voters' Representation Act – whose repeal the ANC had demanded in a January 1952 ultimatum to the Prime Minister.[15] Although the protests remained non-violent, the notion of "defiance" represented a rhetorical escalation from the ANC's earlier programme of "passive" resistance.[5] Thousands of volunteers were trained to carry out acts of civil disobedience, and on one estimate 8,000 people were arrested over subsequent months.[2] The campaign wound down in late 1952 and officially ended in 1953, when further repressive legislation was passed: the Public Safety Act enabled the government to call a state of emergency, while the Criminal Law Amendment Act punished civil disobedience with a three-year prison sentence and/or flogging.[15]

In July 1952, 20 or 21 non-white leaders of the campaign, including Mandela, Sisulu, and ANC President Moroka, were charged with violating the Suppression of Communism Act. Judge Franz Rumpff found them guilty of “statutory communism” – it was clear that Moroka, for example, was not ideologically a communist – and suspended their sentences.[17][18] However, Moroka had fallen out of favour with the ANC during the trial – he had pursued a separate legal defence and had publicly disowned the Defiance Campaign and the ANC's objective of racial equality.[19][20] In December 1952, Luthuli, who had risen to prominence during the Defiance Campaign,[2] beat Moroka in a vote to become ANC President.[7][11]

ANC membership rose from around 7,000[2] to 100,000 over the course of the Defiance Campaign.[2][11] In late 1953, in response to this expansion – and anticipating further legal constraints on the ANC's activities – Mandela proposed a new organisational system, known as the "M Plan", under which branches would be divided into "cells", each centred around a single street and headed by a steward.[3] It was most effectively implemented in the Eastern Cape.[11] The new legislation made civil disobedience infeasible, and the ANC turned to other methods, including boycotts, demonstrations, and non-cooperation.[11] The years following the Defiance Campaign were also notable for the ANC's renewed commitment to collaboration with other anti-apartheid groups.[2] For example, in November 1952 in Johannesburg, the ANC and Indian Congress held a public meeting at which Tambo and Yusuf Cachalia called for the establishment of an anti-apartheid organisation open to whites and able to coordinate with the Congresses.[11] This led to the foundation of the South African Congress of Democrats in 1953.

1955: Congress of the People

The People Shall Govern!

All National Groups Shall Have Equal Rights!

The People Shall Share in the Country's Wealth!

The Land Shall Be Shared Among Those Who Work It!

All Shall Be Equal Before The Law!

All Shall Enjoy Equal Human Rights!

There Shall Be Work And Security!

The Doors of Learning And of Culture Shall Be Opened!

There Shall Be Houses, Security And Comfort!

There Shall Be Peace And Friendship!

At an ANC meeting in August 1953, Z. K. Matthews proposed a national convention which would represent all groups of South African society and could "draw up a Freedom Charter for the democratic South Africa of the future".[11] The next month, the ANC national conference endorsed this proposal,[11] and the Congress of the People was held, with the cooperation of other groups, in Kliptown, Soweto, in June 1955.[2] The alliance of the groups present at the congress, which endured long afterwards, later became known as the Congress Alliance.[2] The congress ratified the Freedom Charter,[21] a document based on demands articulated during a process of mass participation and which became a fundamental document for the anti-apartheid struggle.[2]

Suttner says of the charter, "Its strength lay at once in its being a statement of general freedoms found in most human rights documents and also in its speaking directly to the specific form of rights violation under apartheid."[2] The content of the charter and the composition of the congress were both explicitly multi-racial, even as the individual groups present were separated along racial lines.[2][5] Famously, part of it reads (with a crucial phrase later included in the preamble to the post-apartheid Constitution of 1996):[21]

We, the People of South Africa, declare for all our country and the world to know: that South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people... And we pledge ourselves to strive together, sparing neither strength nor courage, until the democratic changes here set out have been won... Let all who love their people and their country now say, as we say here: 'THESE FREEDOMS WE WILL FIGHT FOR, SIDE BY SIDE, THROUGHOUT OUR LIVES, UNTIL WE HAVE WON OUR LIBERTY.'

In addition to its claims to civil and political equality, the charter incorporated demands for the nationalisation of South Africa's mineral wealth and other economic sectors.[5] According to Lodge, the ANC's endorsement of the charter reflected the changing character of its leadership and membership, who in 1955 were more likely to have legal, trade union, or non-professional backgrounds than the earlier generation of professional and religious leaders.[11]

1956–61: Treason Trial

In December 1956, 156 prominent figures in the Congress Alliance were arrested and charged with treason, with the text of the Freedom Charter considered important evidence for the charges.[2] The initial defendants in the resulting Treason Trial included Mandela, Sisulu, Tambo, ANC President Luthuli, and most of the rest of the ANC's NEC. All the defendants were released or acquitted by 1961, but the protracted trial apparently led to the neglect of organisational and administrative duties by ANC leadership.[2][11] However, the trial has been interpreted as cementing the ties among Congress Alliance members (and with several communist leaders, such as Joe Slovo and Ruth First, who were also charged).[3] Mandela later joked that the detention of the defendants in communal cells enabled "the largest and longest unbanned meeting of the Congress Alliance in years".[22]

1959: Breakaway of the Pan Africanist Congress

In April 1959, in an escalation of longstanding ideological tensions, a group of young Africanists broke away from the ANC to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), under the leadership of the charismatic Robert Sobukwe.[5] The Africanist bloc had generally opposed the Freedom Charter and the broader Congress Alliance, feeling that the influence of the latter had steered the ANC away from the African nationalism asserted in the 1949 Programme of Action, in favour of a new de facto policy of accommodating whites and communists.[5][11] The complexity of the rationale for the bloc's opposition to multi-racialism is reflected in Sobukwe's opening address to the PAC's founding convention:[23]

...multi-racialism is in fact a pandering to European bigotry and arrogance. It is a method of safeguarding white interests irrespective of population figures. In that sense it is a complete negation of democracy. To us the term 'multi-racialism' implies that there are such basic insuperable differences between the various national groups here that the best course is to keep them permanently distinctive in a kind of democratic apartheid. That to us is racialism multiplied, which probably is what the term truly connotes. We aim, politically, at a government of the Africans by the Africans for Africans, with everybody who owes his only loyalty to Afrika and who is prepared to accept the democratic rule of an African majority being regarded as an African. We guarantee no minority rights, because we think in terms of individuals, not groups.

According to Lodge, another aspect of the disagreement concerned differing pictures of the ANC's role in mass mobilisation. The Africanists believed that a nationalist platform would be more effective at garnering a mass following than would the coalition of sectional interests represented by the Congress Alliance.[11] At the same time, Sobukwe argued that the role of a liberation movement was only to "show the light" to the masses, who by spontaneous action would "find their way", while the ANC leadership of the time tended towards a view on which it should take a more active role in directing and channeling the aspirations of the people.[11] The ANC and PAC immediately became rivals.[5]

1960: Banning

On 21 March 1960, in what became known as the Sharpeville massacre, the police opened fire on an anti-pass demonstration organised by the PAC, killing 69 people and injuring 180 others. The PAC had organised its protest for that date in order to pre-empt the ANC's own anti-pass campaign, which was scheduled to begin later in March.[5] In response to the massacre, the ANC declared a day of mourning and leaders publicly burned their passes in protest.[2] The government declared a state of emergency and, on 8 April, both the ANC and the PAC were banned.[24] They were not unbanned until February 1990, almost thirty years later.

Exile and armed struggle

1961: Establishment of Umkhonto we Sizwe

Following the Sharpeville massacre, the ANC abandoned its policy of exclusively non-violent resistance. In December 1960, the reconstituted CPSA underground, now the South African Communist Party (SACP) – which included several ANC leaders, including Mandela and Sisulu – resolved that the Congress movement should reconsider its reliance on non-violence.[24] In June 1961, Mandela presented a proposal to the ANC NEC, and then to the joint leadership of the Congress Alliance, which entailed a "turn to violence".[24] Accordingly, later that year, a military body was formed, called Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK, Spear of the Nation). Mandela was its first commander-in-chief and its High Command also included Sisulu and Joe Slovo of the SACP.[24] At this stage, MK was not yet an official ANC body, nor had it been directly established by the ANC NEC: it was considered an autonomous organisation, established and staffed by members of the SACP as well as the ANC.[24][25] Importantly, this meant that MK membership was open to all races, during a period in which ANC membership remained open only to black Africans.[3] This non-racial membership policy remained in place after the ANC had formally recognised MK as its armed wing in October 1962.[24]

It was only when all else had failed, when all channels of peaceful protest had been barred to us, that the decision was made to embark on violent forms of political struggle, and to form Umkhonto we Sizwe. We did so not because we desired such a course, but solely because the Government had left us with no other choice.

– Nelson Mandela's 1964 statement from the dock

The ANC's official rationale for initiating the armed struggle – that it had been an unavoidable and unanimous response to increased state repression – has since been complicated by historians.[24][4] In particular, several have argued that some groups within the ANC had supported a strategy of armed resistance in the years prior to Sharpeville, for separate reasons – especially to improve the ANC's international standing and to fulfil the demands of some of its constituents – and, controversially, have argued that ANC President Luthuli in fact remained staunchly opposed to the use of violence.[3][26][27]

The launch of MK was marked by the inauguration of a campaign of sabotage attacks, beginning on 16 December 1961 with a wave of bombings against government installations which were (at the instruction of the High Command) unoccupied.[24] In May 1962, a memorandum co-authored by Mandela, Tambo, and Robert Resha referred to the MK sabotage attacks as "the first phase of a comprehensive plan for the waging of guerrilla operations",[24] a position endorsed by the ANC's national conference in October 1962.[24] Yet sabotage attacks, not guerrilla warfare, remained the primary activity of MK, with about 200 such attacks taking place between December 1961 and December 1964.[24]

Founding of the external mission

After its banning in April 1960, the ANC was driven underground. In the following years, many of its leaders were banned or arrested, including Mandela in 1962 and much of the rest of MK's top leadership in 1963 during the raid on Liliesleaf farm.[25] Mandela, Sisulu, Ahmed Kathrada, Govan Mbeki, and several others were sentenced to life imprisonment during the subsequent Rivonia trial, with still others joining them on Robben Island pursuant to the Little Rivonia trial. Luthuli remained banned and under house arrest in Zululand until his death in 1967 (though he was permitted to accept his 1960 Nobel Peace Prize).[7] Thus from around 1963, the ANC effectively abandoned much of even its underground presence inside South Africa and operated almost entirely from its external mission, with headquarters first in Morogoro, Tanzania, and later in Lusaka, Zambia.[28] Tambo, who had been directed to set up the external mission in March 1960, thus became the ANC's de facto leader, and when Luthuli died in 1967 he became acting ANC President.[25][3] From 1963, MK training was organised in Dar es Salaam, and by 1965 MK activities were concentrated at its Kongwa camp,[28] one of its four Tanzanian military bases.[29] According to historian Stephen Ellis, "it is no exaggeration to say that the ANC was in danger of extinction inside South Africa" during this period.[25]

1969: Hani memorandum

In its early years of exile, while MK focused on training its recruits and re-establishing an organisational structure under the command of Joe Modise, the MK rank-and-file reportedly grew frustrated with the paucity of its operational activity inside South Africa.[3][30][29] In 1967 and 1968, MK launched the Wankie and Sipolilo campaigns, both joint campaigns with the Zimbabwe People's Revolutionary Army. The campaigns, which aimed to infiltrate MK cadres back into South Africa through Zambia and Rhodesia, were considerable failures. Following armed confrontations with joint Rhodesian and South African security forces, a majority of the MK operatives involved were killed or imprisoned.[29] When two veterans of the Wankie campaign returned from prison in Botswana – one of them Chris Hani, who had been the commissar of MK's "Luthuli Detachment" and was then in his mid-20s – they and five other cadres wrote a memorandum, known as the Hani memorandum,[3] criticising the "wrong policies and personal failures" of the ANC leadership.[29] The memorandum cited corruption, nepotism, and a misplaced focus on garnering international support over fighting on the home (South African) front;[30] and it specifically named Modise and ANC Secretary-General Duma Nokwe as culprits.[31] All seven signatories to the memorandum were suspended.[29]

1969: Morogoro conference

In response to the Hani memorandum and other signs of "crisis" in the MK ranks, Tambo called the landmark Morogoro Conference, the ANC's first consultative conference and first conference in exile, held between 25 April and 1 May 1969.[30] Most dramatically, at the conference Tambo referred to a "loss of confidence in the men who have been leading our struggle from Lusaka" and offered his resignation as acting ANC President.[30] Once he had left the meeting, the conference passed an unopposed vote of confidence in him,[30] and he ultimately remained acting President until his appointment was formally confirmed in 1985.[28] The conference also reinstated Hani and the other six cadres who had been suspended, and it adopted a new "Strategy and Tactics" document, drafted by Slovo.[30] The document affirmed that the seizure by force of state power in South Africa was a central objective of the struggle, but, acknowledging a position expressed by the Hani memorandum, it clarified the relationship between military and political struggle:[32]

[O]ur movement must reject all manifestations of militarism which separates armed people's struggle from its political context... The primacy of the political leadership is unchallenged and supreme and all revolutionary formations and levels (whether armed or not) are subordinate to this leadership.

The conference resolved to open membership of the ANC to non-blacks.[4][30] Although the NEC remained open only to black members, the conference also established the powerful[3] and multi-racial Revolutionary Council, on which MK and the SACP were well represented. The council, chaired by Tambo, oversaw both political and military aspects of the ANC's internal anti-apartheid struggle, until it was replaced by the Politico-Military Council in 1983.[28]

1975: Expulsion of the Gang of Eight

After 1969, a dissident Africanist faction, known as the "Gang of Eight" or "Group of Eight", objected to the influence given at Morogoro to non-Africans and the SACP. As their objections became more boisterous, they were expelled from the ANC in 1975.[30][33] The group included Tennyson Makiwane, his brother Ambrose, and at least one other member of the NEC.[34] At a public gathering in 1975, Makiwane read out a statement which claimed that the SACP used the ANC as its "front organisation", and that a "non-African clique" had "hijacked the ANC" and was attempting "to substitute a class approach for the national approach to our struggle".[34][35] The Central Committee of the SACP published a statement on the group's expulsion in its journal, the African Communist, under the title "The Enemy Hidden Under the Same Colour", comparing the group to the Africanist faction which had broken away to form the PAC in 1959.[35]

Armed resistance

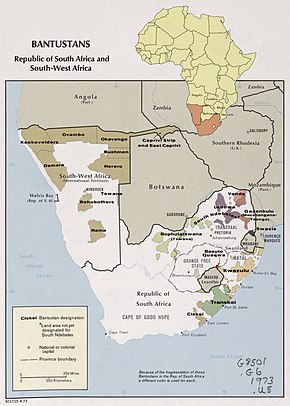

From the mid-1970s, conditions for an armed struggle improved: Angola and Mozambique achieved independence in 1975, allowing the ANC to set up facilities considerably closer to the home front, and, from 1976, the Soweto uprising in South Africa saw thousands of students cross the borders to seek military training. According to one estimate, the ANC in exile expanded from 1,000 members in 1975 to 9,000 members in 1980, with most of the increase accounted for by new MK cadres.[36] Most of the new recruits, beginning with the "June 16 Detachment", were sent to MK camps in Angola, and small numbers were infiltrated back into South Africa to carry out attacks.[37][38] In March 1979, the ANC leadership, by then headquartered in Lusaka, undertook a strategic review following a 1978 visit to Vietnam. Its report was published in March 1979 as the "Green Book" and outlined the "Four Pillars of the Revolution": armed struggle; an internal underground; popular mobilisation; and international isolation of the apartheid regime.[3] The new military strategy emphasised urban areas, in contrast to the rural guerrilla war originally envisaged. Also in 1979, Tambo directed Slovo to establish a special operations unit, whose focus became "armed propaganda": attacks on symbolic state targets, partly aimed at attracting new MK recruits under the slogan, "Swell the Ranks of Umkhonto we Sizwe".[3][37] Perhaps most memorably, on 1 June 1980 the unit bombed the Sasol oil refinery complex, causing damage estimated at R66 million.[37] Likewise, a 1982 special operations bombing of the Koeberg nuclear power station was reported to cost the state between R20 million and R100 million in damages.[4][37][39]

At last... the ANC has stopped blowing up walls. It's now doing the right thing. It can't make sense to continue blowing up pylons if we're going to get massacred for it and going to get hanged. It's not going to be possible for us to continue our action on the exclusive basis that no civilians shall be killed. That is implicit in our idea of intensifying the struggle... People are very resentful and feel they want to hurt... They somehow felt the ANC had been denying them this.

– ANC statement on the 1983 Church Street bombing, which killed 19 people[4]

MK guerrilla activity increased steadily over this period, with one estimate recording an increase from 23 incidents in 1977 to 136 incidents in 1985.[38] By 1986, the most common type of incident was attacks on or clashes with the police, including black policemen; MK operatives also targeted community councillors and bantustan politicians, and attacked infrastructure instalments using landmines, limpet mines, and grenades.[38] The ANC had maintained that any civilian casualties would be regrettable and unintended,[37][38] but a number of civilians were killed in these attacks, including in the 1983 Church Street bombing, the 1985 Amanzimtoti bombing, the 1986 Magoo's Bar bombing, and the 1987 Johannesburg Magistrate's Court bombing. There was apparently some disagreement within the ANC (and within the ANC-MK-SACP bloc) as to whether MK attacks aimed to initiate an armed insurrection or only to weaken the apartheid government's position.[3] Publicly, Tambo suggested the latter, telling the media in 1986 that the ANC's main objective was not "military victory but to force Pretoria to the negotiating table".[38]

During this period, the South African Defence Force engaged in a number of raids and bombings on ANC bases in the countries neighbouring South Africa, such as the 1981 raid on Maputo, 1983 raid on Maputo, and 1985 raid on Gaborone. Several ANC members, such as Dulcie September and Joe Gqabi, were targeted for assassination during the 1980s.

1980–81: Shishita

The ANC's national intelligence and security department (commonly known as NAT) had greatly expanded during the post-1976 influx of recruits, among whom the ANC worried there might be state agents and whom NAT screened.[36] The security wing of NAT became known as Mbokodo (the Grinding Stone), and by 1980 Tambo was concerned that it was suppressing ideological disagreement and alienating the rank-and-file.[36][40] There were later widespread allegations that dissident MK cadres had faced torture, detention without trial, and even execution.[41][42]

In 1980 and 1981, worsening relations between MK and the Zambian government – primarily due to a large undeclared weapons cache found by Zambian security forces on an ANC farm outside Lusaka – triggered a "panic" within the ANC leadership about poor discipline among MK members, first in Zambia and then also in Angola.[40] Concerns included drug smuggling, car theft, dagga abuse, drunk driving, and a general element of ill discipline, as when in 1981 a group of MK members refused to transfer from Zambia to Angola because they perceived the Angolan camps as a place of punishment ("the ANC's Siberia").[40] This was followed by a major clean-up operation, known as "Shishita", during which NAT rounded up dozens of MK cadres and transferred them to Angola for detention and interrogation.[3] In the so-called Shishita report of 1981, formally titled the "Report on subversive activities of police agents in our movement", NAT claimed to have uncovered an extensive spying ring and a plot to assassinate the ANC leadership. Although most of the confessions had been extracted under torture, with several people dying during interrogation, the confessed spies were executed in Angola in the years that followed.[40]

1983–84: Mkatashinga

In December 1983, at the MK camp in Viana, Angola, unrest broke out on such a scale that it is generally characterised as a mutiny. Known as Mkatashinga (derived from a Kimbundu word meaning exhausted soldier),[43] the revolt was triggered by cadres' demand that they be sent to fight the apartheid state in South Africa, rather than to fight further battles in the Angolan Civil War. Cadres also objected to the conduct of Mbokodo.[44] During the ensuing fights between the mutineers and loyalists, several MK members died, and others were arrested and detained in prison camps, some to be tried later by military tribunals.[44] It has been called "the most shameful episode in the history of the ANC".[43]

Between the mutiny at Viana and a second only months later at the Pango camp, the ANC appointed the Commission of Inquiry into Recent Developments in the People's Republic of Angola, chaired by MK commissar Hermanus Loots (code-named James Stuart), to probe cadres' grievances.[3] Its 1984 report, known as the Stuart report, found no evidence to substantiate rumours that enemy agents were responsible for the "disturbances", and made several recommendations for improving conditions in the camps. The report was not made public until almost ten years later.[36][40]

1985: Kabwe conference

Owing to the mutinies, the ANC's second consultative conference, held in Kabwe, Zambia, in mid-1985, was, like the first consultative conference in Morogoro, called pursuant to a "crisis" among the MK rank-and-file.[40] Indeed, one of the mutineers' demands was that such a conference should be called.[44] A report to the conference admitted that some NAT personnel had made "bad, sometimes terrible mistakes",[45] and the conference did attempt to act on the findings of the Stuart report: it agreed with Stuart's recommendation that NAT should be overhauled, and it adopted a code of conduct and established internal judicial procedures for the first time.[40] Also at Kabwe, the NEC (now enlarged) was fully elected, rather than appointed by leadership, for the first time in decades, and Tambo was elected permanently to the ANC presidency, which he had already held in an acting capacity for 18 years.[28] All racial barriers to NEC membership were removed, and Slovo became the first white to be elected.[25] Finally, it was resolved that the ANC should hold consultative conferences, with elections, every five years.[38]

These changes at Kabwe followed an organisational restructuring in 1983, which had replaced the Revolutionary Council with the Politico-Military Council, established various Regional Politico-Military Committees, and formalised the military command structure of MK.[28] In 1987, NAT was put under the oversight of the President's Council, also known as the National Security Committee and chaired by Tambo, and the body previously known as "Political HQ" was replaced by the augmented Internal Political Committee, responsible for the ANC's political underground inside South Africa.[28]

1985: Expulsion of the Marxist Workers' Tendency

In 1979, eminent historian Martin Legassick and three others were suspended from the ANC on the basis of papers they had published, supporting a Trotskyist position and calling for the ANC to revise the strategy underlying its armed struggle. They argued that the armed struggle should aim to elicit mass participation in overthrowing apartheid and bringing about a socialist revolution. They formed the Marxist Workers' Tendency within the ANC in 1981 – the ideology of which was anonymously condemned as "economistic and workerist" in the African Communist[46] – and were permanently expelled in 1985.[3][46]

International relations

For much of its time in exile, the ANC was treated with hostility by the United States and United Kingdom. In a 1986 speech, U.S. President Ronald Reagan condemned acts of "calculated terror" by elements of the ANC, which he said were "creating the conditions for racial war".[47] Two years later, the U.S. State Department classified the ANC as a terrorist organisation, noting that, though it publicly denied targeting civilians, it had been responsible for civilian deaths.[47] Neither the ANC nor Mandela were removed from the U.S. terror watch list until 2008.[48] U.K. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher also called the ANC a terrorist organisation in 1987,[49] although the ANC continued to maintain its London office in Islington, which it occupied from 1978 to 1994 and which is now marked with a plaque.[50]

We draw immense satisfaction and inspiration from the fact that the Soviet Union is resolved to contribute everything within its possibilities and, within the context of our own requests, to assist the ANC, SWAPO and the peoples of our region to achieve these objectives... the Soviet Union is acting neither out of consideration of selfish interest nor with a desire to establish a so-called sphere of influence.

– Tambo in 1986, following a meeting at the Kremlin with Mikhail Gorbachev[45]

On the other side of the Cold War divide, the ANC had a close relationship with the Soviet Union, which was staunchly opposed to the apartheid government, including in regional conflicts in Angola and Mozambique. Ellis has suggested that much of the Soviet support to the ANC came through the ANC's close relationship with the SACP,[3] but, according to Vladimir Shubin, another historian, the ANC had “direct access” to the Soviet leadership from the 1960s.[45] In 1961, SACP leaders Moses Kotane (also a senior ANC member) and Yusuf Dadoo visited Moscow to outline the party's plans to launch an armed struggle, and secured the support of the ruling Communist Party of the Soviet Union.[45] Tambo himself visited Moscow in April 1963, and in subsequent years the ANC sent regular delegations to Moscow.[3]

In return, the organisation received substantial Soviet support. From 1962, ANC members identified as potential leaders were sent to the Soviet Union for academic and political training, and thousands of MK recruits were sent for basic and specialised military training in the Soviet Union over subsequent decades.[3][45] Between 1979 and 1989, at Tambo's request came to Angola to lead training programmes at the MK camps.[45] According to the Russian government, between 1963 and 1990, the Soviet Union provided the ANC with assistance worth about 61 million roubles, including 36 million roubles for military supplies (including tens of thousands of guns), 12 million roubles for other supplies, and the rest for technical assistance and training.[45] This financial and technical support continued well into 1990, with the relationship remaining close enough that Slovo and ANC Secretary-General Alfred Nzo were reportedly in Moscow when the South African government announced Mandela's release and the ANC's unbanning.[45]

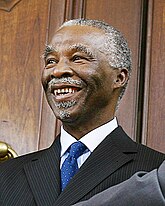

Preliminary negotiations

From the mid-1980s, mounting international and domestic pressure made the apartheid government's position appear increasingly unsustainable, and the attention of some ANC leaders turned to the prospect of negotiating with the South African government to end apartheid. From September 1985, the ANC hosted in Lusaka and Harare several formal deputations from South African civil and labour groups, presumably with an eye to building partnerships and discussing aspects of a potential settlement. These groups included the Progressive Federal Party, the Soweto Parents' Crisis Committee, the Congress of South African Trade Unions, the National Union of South African Students, and the National African Federated Chamber of Commerce.[38] Also in 1985, the ANC met with a group of prominent businessmen, led by the chairman of Anglo American; and ANC representatives, especially Tambo's protégé Thabo Mbeki,[51] continued secretly to engage with businessmen and government officials.[52] However, the armed struggle continued, and within the ANC there was disagreement and perhaps uncertainty about the prudence of pursuing a peaceful settlement, a risky strategy if it alienated the ANC's constituency or resulted in a fruitless renouncement of armed struggle.[3][53]

In this context, in 1986 Tambo sanctioned the initiation of the clandestine Operation Vula, through which the ANC would seek to re-establish an armed underground and political leadership inside South Africa. Through Operation Vula, ANC leaders, including Mac Maharaj and Ronnie Kasrils of the NEC, secretly returned to South Africa after many years in exile. They also established a secret direct channel of communication between Tambo and Mandela, who, still imprisoned, was also in contact with the government on the ANC's behalf.[52][53] When the police uncovered Vula in 1990, eight ANC leaders were charged with terrorism, causing a major scandal at an early phase of the formal negotiations to end apartheid.[54]

Return to South Africa

On 2 February 1990, State President F. W. De Klerk unbanned the ANC and other illegal organisations and announced the beginning of formal negotiations for a peaceful settlement. Mandela was released shortly thereafter.[2] These decisions by the apartheid regime have been attributed to a number of factors and combinations thereof, among them the end of the Cold War, a growing economic crisis inside South Africa, mounting international pressure, and a sustained front of internal dissent.[5] Unbanned, the ANC's exiled leaders were able to return to South Africa to establish overt structures and to participate in the negotiations. It had its new headquarters at Shell House in Johannesburg, until in 1997 it relocated to its current headquarters at Luthuli House.[55]

1990: Formalisation of the Tripartite Alliance

The Tripartite Alliance was established in mid-1990, comprising the ANC (recognised as the Alliance leader), the SACP, and the powerful Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU). Like the SACP, COSATU had already been aligned to the ANC in prior years — in 1987, two years after it was founded, it and many of its affiliates had adopted the Freedom Charter.[56] The membership and leadership of all three bodies also already overlapped significantly.[57]

1990: Johannesburg conference

In December 1990 in Johannesburg, the ANC held a third national consultative conference, its first inside the country, followed by a rally in Soweto with addresses by Mandela and Tambo. This was the first official meeting between exiles, underground members, and formerly imprisoned members of the ANC, and it affirmed the composition of the NEC as elected at the 1985 Kabwe conference.[28] Tambo had returned to South Africa from Lusaka the day before the conference began – after over three decades in exile – and the conference endorsed a message of gratitude to Zambian President Kenneth Kaunda and the people of Zambia for hosting the ANC in exile. The conference also resolved that it would consider suspending negotiations if the state did not release all political prisoners, allow the return of all exiles, and repeal all repressive legislation before 30 April 1991.[58]

1991: Durban conference

In July 1991, at its 48th National Conference in Durban, the ANC elected a new NEC and top leadership. Tambo had stepped down after 24 years as president following a stroke; Mandela was elected to replace him, and Sisulu was elected his deputy.[28] Notably, influential trade unionist Cyril Ramaphosa was elected secretary-general, reflecting the gradual merger that was taking place not only between the former wings of the ANC (that in exile, that underground, and that on Robben Island), but also between the ANC and other anti-apartheid groupings that had been influential inside the country while the ANC was in exile. Also elected to the NEC were leaders of the United Democratic Front (UDF), such as Trevor Manuel, Terror Lekota, and Cheryl Carolus.[59] When the UDF formally disbanded the next month, the ANC was to absorb still more of its former leaders and members.

Negotiations

Political violence

Our own tasks are very clear. To bring about the kind of society that is visualised in the Freedom Charter, we have to break down and destroy the old order. We have to make apartheid unworkable and our country ungovernable. The accomplishment of these tasks will create the situation for us to overthrow the apartheid regime and for power to pass into the hands of the people as a whole.

– ANC President Tambo on Radio Freedom in July 1985[60]

Political violence inside South Africa, often involving ANC supporters, had escalated throughout the 1980s. The campaign to make the townships "ungovernable", which had played a significant role in heightening the internal pressure on the regime to begin negotiations, had also led to the rise of local vigilantes (so-called self-defence units and self-protection units) and kangaroo courts. ANC-aligned groups sometimes executed opponents and suspected collaborators, often by necklacing.[61][62] There were also violent clashes, especially in the Transvaal and Natal, between groups aligned to Inkatha and groups aligned to the ANC or to the UDF, which in turn was aligned to the ANC.[63] Yet it is debatable how much control the ANC in exile had over its supporters inside South Africa during the 1980s.[2][64] One historian argues that when Tambo encouraged South Africans to render the country "ungovernable", he was "trying to place the ANC at the head of an [already] unfolding social revolution".[5] On the practice of necklacing, which received international condemnation, ANC Secretary-General Alfred Nzo said in 1986, "Whatever the people decide to use to eliminate those enemy elements is their decision. If they decide to use necklacings, we support it."[5]

The political violence worsened during the transition to democracy between 1990 and 1994, with as many as 14,000[61] or 15,000[65] people killed during that period. Significant confrontations included the 1992 Boipatong massacre and the 1994 Shell House massacre. It was during this period that ANC leaders began to implicate a state-aligned "third force" in the violence. As early as 1990, the ANC's position was that the violence was "part of a deliberate attempt by the state and its allies to destabilise the ANC and to sow terror and chaos amongst our people".[58] Such allegations have since been partially substantiated.[66][67] Widespread ANC-IFP violence dissipated by 1996,[65] although there were further localised conflicts in following years.

In April 1993, the assassination of Chris Hani, who was by then an extremely popular figure in the ANC and an NEC member, led to an outbreak of violence.[68][69][70] In an unprecedented televised address to the nation, Mandela delivered a plea for calm, which some remember as having prevented the spread of the unrest.[71] Mandela said:[72]

Tonight I am reaching out to every single South African, black and white, from the very depths of my being. A white man, full of prejudice and hate, came to our country and committed a deed so foul that our whole nation now teeters on the brink of disaster. A white woman, of Afrikaner origin, risked her life so that we may know, and bring to justice, this assassin. The cold-blooded murder of Chris Hani has sent shock waves throughout the country and the world. Our grief and anger is tearing us apart... Any lack of discipline is trampling on the values that Chris Hani stood for. Those who commit such acts serve only the interests of the assassins, and desecrate his memory... We will not be provoked into any rash actions.

Government of South Africa

1994–99: Presidency of Nelson Mandela

1994 general election

South Africa's first democratic elections were held between 26 and 29 April 1994. As widely expected, the ANC, running alongside its Tripartite Alliance partners, won comfortably, gaining 62.65% of the national vote and 252 of the 400 seats in the new National Assembly.[73] It also won control of all nine provinces but two: the National Party, later reconstituted as the New National Party (NNP), narrowly won the Western Cape; and Inkatha, by then known as the Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP), won KwaZulu-Natal still more narrowly.[74] The result in KwaZulu-Natal came to be known as "negotiated", in the infamous phrase of an electoral officer – despite allegations of foul play, the ANC opted to accept the IFP's victory, probably in order to avert further violence in the province.[74][73] In line with the interim Constitution, the ANC formed a coalition Government of National Unity, intended to function as a transitional power-sharing mechanism. Mandela became South Africa's first black president and first democratically elected president, and Mbeki was his deputy. The National Party installed De Klerk as a second deputy president, having narrowly achieved the requisite 20% share of the national vote.[73]

Bloemfontein conference

For the first time in the history of our country, we have under one roof, sharing the same vision and planning as equals, delegates from every sector of South African society, including those who hold the highest offices in the land... we can proudly say to the founders: the country is in the hands of the people; the tree of liberty is firmly rooted in the soil of the motherland!

– Mandela's political report to the 49th Conference[75]

In December 1994, newly appointed to government, the ANC held its 49th National Conference in Bloemfontein, under the theme "From Resistance to Reconstruction and Nation-Building".[76] Mandela was re-elected unopposed as ANC president, and Ramaphosa was re-elected unopposed as secretary-general. The composition of the rest of the top leadership changed, ushering in a younger generation – notably, Sisulu declined to stand for re-election and was replaced by Mbeki, while Jacob Zuma won the national chairmanship in a landslide.[77] The expanded NEC contained several figures from the internal struggle against apartheid – the candidate who received the most votes was former Transkei politician Bantu Holomisa.[78] The conference endorsed a substantive restructuring of the organisation for the post-apartheid era,[79] and it reaffirmed several central policies, including the 1992 Ready to Govern policy, the 1994 Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP), and the Health Plan on national health insurance.[80]

Reconstruction and Development Programme

Truth and Reconciliation Commission

In the early 1990s, there was substantial media reporting on alleged abuses in MK camps in exile. The ANC set up two commissions of inquiry to investigate — the Skweyiya Commission, appointed in 1991, and the broader Motsuenyane Commission, appointed in 1993. Both reported substantial abuses, especially by NAT.[81] In 1993, while accepting the findings of the Motsuenyane Commission, the ANC repeated an earlier call by NEC member Kader Asmal for the establishment of a commission to investigate all human rights abuses during apartheid.[82] The ANC-led Government of National Unity established such a body, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), in 1995. In addition to testimony from individual members and leaders, the ANC made a detailed collective submission to the TRC.[83] Providing evidence on the "just and irregular war for national liberation" it had conducted, the ANC, both in its submissions and in its oral testimony, acknowledged some abuses but emphasised that it had not intentionally sought to harm civilians.[84]

In July 1996, Mandela fired Holomisa as deputy minister following his appearance before the commission; the next month, following internal disciplinary proceedings, he was expelled from the ANC for having brought the movement into disrepute. Holomisa had testified in May that that former Transkei politician Stella Sigcau, then an ANC cabinet minister, had accepted a "gift" of R50,000 in 1987 in relation to the Transkei government's decision to grant a gambling monopoly to Sol Kerzner.[85][86] Deputy President Mbeki argued that Holomisa should not have made the allegation public without discussing it with the ANC beforehand.[87]

The TRC has grossly misdirected itself in its 'Findings on the Role of the African National Congress', through the pursuit of objectives which are contrary to the spirit and the intention of the Act under which it was established. These 'findings' show an extraordinary refusal on the part of the Commission to locate itself in the context of the circumstances which related to the struggle against apartheid, both within and outside the country.

– ANC statement, 1998[84]

The TRC's five-volume report, published in 1998, recognised the ANC as a major victim of gross human rights abuses during apartheid, but also as a perpetrator of the same.[84] Specifically, the TRC highlighted three categories of ANC actions: its landmine campaign during the 1980s and various bombings which harmed civilians; attacks on suspected collaborators or state witnesses; and the ill treatment, torture, and executions of ANC members in exile.[82] It also assigned partial responsibility to the ANC for the political violence of the early 1990s, especially through its role in arming self-defence units without establishing adequate command-and-control structures.[82]

When it received advance notice of the TRC's findings, the ANC sought to interdict the report's publication, and many of its leaders subsequently rejected the findings.[82][84] TRC Chairperson Desmond Tutu said that he was "taken aback" by this response, given that the findings had been based on the ANC's own "very substantial, full and frank submissions".[82] Yet in a parliamentary debate on the report, the ANC argued that the TRC's findings acted "to delegitimise or criminalise a significant part of the struggle of our people for liberation".[84] A popular ANC talking point was that seeking to equate the actions of the ANC with the actions of the apartheid state was an acceptable form of “moral equivalence".[82]

1999–2008: Presidency of Thabo Mbeki

1999 general election

In the 1999 general election, Mbeki was elected national president, with Zuma as his deputy. Mbeki had ascended to the ANC presidency, unopposed, at the ANC's 50th National Conference in Mafikeng in December 1997. Mandela had since at least February 1995[88] made it clear that he intended to retire in 1999, and Mbeki was understood to be his preferred successor, with Mandela emphasising in the press that Mbeki had already assumed substantial responsibilities and was already "a de facto President".[89] The conference was reportedly preceded by significant political manoeuvring and compromise-brokering, in an effort by the top leadership to ensure that Mandela's succession did not lead to internal conflict.[90][91]

The 1999 elections, conducted under the new Constitution of 1996, marked the end of the Government of National Unity. The ANC had campaigned for, and narrowly received, a two-thirds majority in the National Assembly, and it gained 14 additional seats.[92] It performed markedly better in the Western Cape than it had in 1994, securing a plurality,[92] but the NNP and Democratic Party formed a coalition, blocking ANC control of the province.[74] The ANC likewise gained a plurality in KwaZulu-Natal and became the senior party in a provincial coalition with the IFP,[74] and it comfortably retained control of the other seven provinces.

Arms Deal

In December 1999, following several years of planning and negotiations during the Mandela presidency, the ANC-led government signed R30-billion in defence procurement contracts, under what is commonly known as the Arms Deal. The deal is commonly associated with the large-scale corruption that is alleged to have taken place during and after the procurement process, and some critics have said that it was a defining moment or turning point for the ANC government, less than five years into its tenure.[93][94][95][96] Arms Deal-related corruption allegations have provided a series of political scandals in the years since then, and in 2003 the ANC Chief Whip Tony Yengeni pleaded guilty to fraud in a plea bargain.[97] The ANC itself has been accused of profiting from the deal.[98][99]

Arms Deal corruption was investigated by the Scorpions, an elite unit of the National Prosecuting Authority, which also, in a highly politicised trial, prosecuted the National Police Commissioner Jackie Selebi for corruption. In 2008, the ANC-controlled Parliament disbanded the unit, a decision which faced severe criticism[100][101] and which at least some commentators have linked to its investigations into ANC politicians, especially in relation to the Arms Deal.[102][103] In 2011, the Constitutional Court ruled that the disbanding of the Scorpions had been unconstitutional.[104]

HIV/AIDS policy

Strain in the Tripartite Alliance

By 2002, there were widespread rumours of a rift between the ANC and the SACP,[105] as well as tensions with the third Tripartite Alliance partner, COSATU, which held anti-privatisation protests in July of that year.[106][107] At the centre of their disagreements was the economic policy of the Mbeki government, especially the Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) programme, which leftists perceived as neoliberal.[108][109] Relatedly, the ANC and SACP complained that they were being marginalised by Mbeki's increasingly centralised administration.[110] Nonetheless, the ANC's 51st National Conference in Stellenbosch in 2002 proceeded without contest, although in an address to delegates Mbeki was scathing about the detrimental influence of "ultra-leftists".[111]

The rift in the Tripartite Alliance worsened later in Mbeki's presidency, especially once SACP and COSATU's general secretaries, Blade Nzimande and Zwelinzima Vavi, became overt supporters of Zuma in his burgeoning rivalry with Mbeki.[112] Further criticisms from the left targeted the Mbeki government's HIV/AIDS policy and its foreign policy on Zimbabwe, whose government was then led by Robert Mugabe.[113] By 2006, both the SACP and COSATU had accused the ANC of becoming a bourgeois nationalist party, no longer representative of the interests of the poor and working class.[109]

2004 general election

In the 2004 general election, the ANC gained 13 seats in the National Assembly. It retained its plurality in both KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape, as well as its majority in the other provinces. In the Western Cape, it formed a coalition with the NNP to exclude the new Democratic Alliance (DA).[74] In the aftermath of the elections, the NNP, which had performed very poorly – and which had in 2000 attempted a failed merger with the DA[92] – announced that it would disband and that its members would join the ANC during the floor crossing period.[114] This followed a 2002 cooperation agreement between the ANC and NNP, which had seen two NNP members appointed as national deputy ministers.[115]

Polokwane conference

Although both Mbeki and Zuma were reappointed after the 2004 election, on 14 June 2005 Mbeki removed Zuma from his post as deputy president. This followed the conviction of Schabir Shaik on corruption charges, with the court finding that Shaik had made corrupt payments to Zuma in relation to the Arms Deal.[116] Zuma was replaced by Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka. Though he soon faced his own corruption charges (and from December a rape charge), he retained the ANC deputy presidency, after a brief suspension during the rape trial.[117] An intense rivalry developed between him and Mbeki, with internal factions developing around each. Key points of contention between the two groups reportedly included cadre deployment, political prosecutions, and the ANC's relationship to its Tripartite Alliance partners.[110][118][119][120] Allegations abounded that ANC politicians on both sides were abusing their state offices in service of the rivalry – in October 2005, for example, top Zuma-aligned officials in the National Intelligence Agency had been suspended for illegally spying on Saki Macozoma, an Mbeki ally.[121] There were some disputes on the branch level during the run-up to the 2006 local elections,[122] which were also preceded by service delivery protests,[123] but the ANC ultimately performed well in the election.

By April 2007,[110][124] it was clear that Mbeki intended to run for a third term as ANC President – although he was prohibited by the Constitution from standing again for the national presidency, the ANC has no such term limits internally. Some suspected that Mbeki intended to continue to exert substantial influence over the government through his ANC office.[110][125] Zuma, with the support of the SACP and COSATU, emerged as a challenger to Mbeki in the run-up to the ANC's 52nd National Conference. This resulted in the party's first contested presidential election since that which had deposed Moroka in 1952.[126][127] At the conference, held in Polokwane, Limpopo, in December 2007, Zuma won the ANC presidency, and a slate of Zuma-aligned candidates won other top leadership positions. No fewer than eleven members of Mbeki's cabinet, as well as several other stalwarts of the movement, failed to gain re-election to the NEC.[128][129]

Speculation abounded that Mbeki would resign from, or be pushed out from, the national presidency before the end of his term in April 2009. When the corruption charges against Zuma were reinstated, Mbeki was accused of orchestrating a political conspiracy.[130] In September 2008, High Court Judge Chris Nicholson, while dismissing the corruption charges against Zuma on a technicality, found that there was evidence of "political meddling" by Mbeki in Zuma's case. Nicholson's judgement was later overturned, but the Polokwane-elected NEC immediately called a special meeting and decided after 14 hours of debate that Mbeki should leave his office.[110] The NEC, a party-political organ, had no legal authority to recall Mbeki directly, but the ANC-controlled Parliament would have had the authority to do so. Mbeki decided to accede and resign in order to avoid a protracted and high-profile battle in Parliament.[110][131] About a third of his cabinet also resigned, in protest of the NEC's decision. Mbeki was replaced by Kgalema Motlanthe, who had been elected ANC deputy president at Polokwane. Motlanthe led what was viewed as an interim or caretaker administration while Zuma campaigned for the 2009 elections.[132]

Breakaway of the Congress of the People

In response to Polokwane and to Mbeki's "recall", a group of pro-Mbeki ANC members broke away and in November 2008 announced the foundation of a new political party, the Congress of the People (COPE). They were led by former Defence Minister (and two-term ANC chairperson) Terror Lekota and former Gauteng Premier Sam Shilowa, both of whom had been influential in the anti-apartheid struggle but had failed to gain election to the NEC at Polokwane.[110][133][134] In the 2009 general elections, COPE won 7.42% of the national vote and 30 parliamentary seats, becoming the second largest opposition party less than six months after its establishment.

2009–18: Presidency of Jacob Zuma

2009 general election

In the 2009 elections, the ANC secured 65.9% of votes at the national level – still a comfortable win, but a loss of 15 seats from 2004 and the beginning of the gradual electoral decline ultimately undergone by the ANC between 2009 and 2018.[74] At the provincial level, the ANC won control of eight of the nine provinces, with a significant jump in support in KwaZulu-Natal, Zuma's home province.[74] However, the ANC conclusively lost the Western Cape to the DA. This was due to its declining popularity among minority voters, especially coloured voters, who constitute a large proportion of the population of the Western Cape.[74]

2014 general election

In the 2014 South African general election, and later in the 2016 South African municipal elections, the ANC again secured a majority of the votes, but a notably reduced majority. In 2016, the DA was able to take control over several key municipalities, including Johannesburg and Pretoria. The ANC also lost votes to the newly established Economic Freedom Fighters, which became South Africa's third biggest party.

Corruption scandals

Nasrec conference

Jacob Zuma was replaced as ANC president by Cyril Ramaphosa at the 2017 ANC national conference.

2018–present: Presidency of Cyril Ramaphosa

2019 general election

Leadership

Presidents

- 1912–1917: John Langalibalele Dube

- 1917–1924: Sefako Mapogo Makgatho

- 1924–1927: Zacharias Richard Mahabane

- 1927–1930: Josiah Tshangana Gumede

- 1930–1936: Pixley ka Isaka Seme

- 1937–1940: Zacharias Richard Mahabane

- 1940–1949: Alfred Bitini Xuma

- 1949–1952: James Sebe Moroka

- 1952–1967: Albert John Luthuli

- 1967–1991: Oliver Reginald Tambo

- 1991–1997: Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

- 1997–2007: Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki

- 2007–2017: Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma

- 2017–present: Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa

Deputy Presidents

- 1912–1936: Walter Rubusana

- 1952–1958: Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

- 1958–1985: Oliver Reginald Tambo

- 1985–1991: Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela

- 1991–1994: Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu

- 1994–1997: Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki

- 1997–2007: Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma

- 2007–2012: Kgalema Petrus Motlanthe

- 2012–2017: Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa

- 2017–2022: David Dabede Mabuza

- 2022–present: Paul Shipokosa Mashatile

Secretary-General

- 1912–1915: Solomon Tshekisho "Sol" Plaatje

- 1915–1917: Saul Msane

- 1917–1919: R.V. Selope Thema

- 1919–1923: H. L. Bud M'belle

- 1923–1927: TD Mweli Skota

- 1927–1930: E. J. Khaile

- 1930–1936: Elijah Mdolomba

- 1936–1949: James Arthur Calata

- 1949–1955: Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu

- 1955–1958: Oliver Reginald Tambo

- 1958–1969: Philemon Pearce Dumasile "Duma" Nokwe

- 1969–1991: Alfred Baphethuxolo Nzo

- 1991–1997: Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa

- 1997–2007: Kgalema Petrus Motlanthe

- 2007–2017: Gwede Mantashe

- 2017–2022: Ace Magashule

- 2022–present: Fikile Mbalula

See also

- History of South Africa

- Security Branch

- Separate development

- Africa Hinterland

- Anti-Apartheid Movement

- Henri Curiel

- Amandla

- Radio Freedom

- National Conference of the African National Congress

References

- ^ Daniels, Lou-Anne (8 January 2019). "#ANC107: A brief history of Africa's oldest liberation movement". Independent Online. South Africa. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Suttner, Raymond (2012). "The African National Congress centenary: a long and difficult journey". International Affairs. 88 (4): 719–738. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2346.2012.01098.x. ISSN 0020-5850. JSTOR 23255615. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Ellis, Stephen (2013). External Mission: The ANC in Exile, 1960-1990. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-933061-4. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Lodge, Tom (1983). "The African National Congress in South Africa, 1976–1983: Guerrilla War and armed propaganda". Journal of Contemporary African Studies. 3 (1–2): 153–180. doi:10.1080/02589008308729424. ISSN 0258-9001. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Butler, Anthony (2012). The Idea of the ANC. Jacana Media. ISBN 978-1-4314-0578-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Lodge, Tom (1983). "Black protest before 1950". Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945. Ravan Press. pp. 1–32. ISBN 978-0-86975-152-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d Clark, Nancy L.; Worger, William H. (2016). South Africa: The Rise and Fall of Apartheid (3rd ed.). Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-12444-8. OCLC 883649263.

- ^ Du Toit, Brian M. (1996). "The Mahatma Gandhi and South Africa". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 34 (4): 643–660. doi:10.1017/S0022278X00055816. ISSN 0022-278X. JSTOR 161593.

- ^ "African Claims in South Africa". South African History Online. 1943. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Three Doctors' Pact". African National Congress. 9 March 1947. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Lodge, Tom (1983). "African political organisations, 1953-1960". Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945. Ravan Press. pp. 67–90. ISBN 978-0-86975-152-7.

- ^ Rose, Hilary (5 December 2004). "Building the Academic Boycott in Britain". Palestina Dossier. Archived from the original on 1 October 2006. Retrieved 14 October 2008.

- ^ Crawford, N.; Klotz, A. (28 January 1999). "Appendix: Chronology of Sanctions Against Apartheid". How Sanctions Work: Lessons from South Africa (PDF). Springer. ISBN 978-1-4039-1591-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Frederikse, Julie (2015). "Class of '44". The Unbreakable Thread: Non-racialism in South Africa. South African History Online. Archived from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Lodge, Tom (1983). "The creation of a mass movement: strikes and defiance, 1950-1952". Black Politics in South Africa Since 1945. Ravan Press. pp. 33–66. ISBN 978-0-86975-152-7. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "38th National Conference: Programme Of Action: Statement of Policy Adopted". African National Congress. 17 December 1949. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ "Death the Leveler". Time. 15 December 1952. Archived from the original on 13 February 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2008.

- ^ Lodge, Tom (2006). Mandela: A Critical Life. Oxford University Press, UK. p. 54. ISBN 978-0-19-280568-3. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Mde, Vukani (15 February 2018). "The ANC should charge and expel Zuma". The Mail & Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ Diko, Yonela (10 January 2018). "Jacob Zuma, the James Moroka of our time". Daily Maverick. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ a b Bernstein, Hilda (1 April 1987). "The freedom charter". Third World Quarterly. 9 (2): 672–677. doi:10.1080/01436598708419993. ISSN 0143-6597.

- ^ Mandela, Nelson (11 March 2008). Long Walk to Freedom: The Autobiography of Nelson Mandela. Little, Brown. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-7595-2104-9.

- ^ Sobukwe, Robert (4 April 1959). "Opening Address at the Africanist Inaugural Convention". South African History Online. Archived from the original on 28 December 2021. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Stevens, Simon (1 November 2019). "The Turn to Sabotage by The Congress Movement in South Africa". Past & Present. 245 (1): 221–255. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz030. ISSN 0031-2746.

- ^ a b c d e Ellis, Stephen (1991). "The ANC in Exile". African Affairs. 90 (360): 439–447. doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.afraf.a098442. ISSN 0001-9909. JSTOR 722941. Archived from the original on 26 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ Vinson, Robert Trent; Carton, Benedict (2018). "Albert Luthuli's private struggle: how an icon of peace came to accept sabotage in South Africa". The Journal of African History. 59 (1): 69. doi:10.1017/S0021853717000718. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 165881850. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Suttner, Raymond (2010). "'The Road to Freedom is via the Cross' 'Just Means' in Chief Albert Luthuli's Life". South African Historical Journal. 62 (4): 693–715. doi:10.1080/02582473.2010.519939. S2CID 145562749. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i African National Congress (1997). "Appendix: ANC structures and personnel". Further submissions and responses by the African National Congress to questions raised by the Commission for Truth and Reconciliation. Pretoria: Department of Justice. Archived from the original on 14 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Houston, Gregory; Ralinala, Rendani Moses (2004). "The Wankie and Sipolilo Campaigns". The Road to Democracy in South Africa. Vol. 1. Zebra Press. pp. 435–492. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Macmillan, Hugh (1 September 2009). "After Morogoro: the continuing crisis in the African National Congress (of South Africa) in Zambia, 1969–1971". Social Dynamics. 35 (2): 295–311. doi:10.1080/02533950903076386. ISSN 0253-3952. S2CID 143455223. Archived from the original on 31 December 2021. Retrieved 26 December 2021.