Baltimore Memorial Stadium

"The Old Grey Lady of 33rd Street" "The World's Largest Outdoor Insane Asylum" | |

Memorial Stadium in 2000 | |

| |

| Address | 900 East 33rd Street |

|---|---|

| Location | Baltimore, Maryland |

| Coordinates | 39°19′46″N 76°36′5″W / 39.32944°N 76.60139°W |

| Owner | City of Baltimore |

| Operator | Maryland Stadium Authority |

| Capacity | 31,000 (1950) 47,855 (1953) 53,371 (1991) |

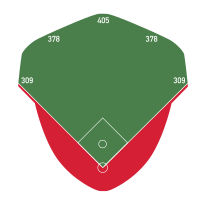

| Field size | Left Field – 309 ft Left-Center – 446 ft (1954), 378 ft (1990) Center Field – 445 ft (1954), 405 ft (1980) Right-Center – 446 ft (1954), 378 ft (1990) Right Field – 309 ft  |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1921 (first version) 1949 (second version) |

| Opened | December 2, 1922 (first version) April 20, 1950 (second version) |

| Closed | December 14, 1997 |

| Demolished | April 2001–February 15, 2002[1] |

| Construction cost | US$6.5 million ($82.3 million in 2023 dollars[2]) |

| Architect | Hall, Border, and Donaldson[3] |

| Structural engineer | R. E. L. Williams (building construction), Faisant and Kooken (consulting)[4] |

| General contractor | DeLucca-Davis & Carozza/Joseph F. Hughes[5] |

| Tenants | |

Baltimore Orioles (IL) mid-season 1944–1953

Baltimore Colts (AAFC / NFL) 1947–1950

Baltimore Comets (NASL) 1974–1975 | |

Baltimore Memorial Stadium was a multi-purpose stadium in Baltimore, Maryland, that formerly stood on 33rd Street (aka 33rd Street Boulevard, renamed "Babe Ruth Plaza") on an oversized block officially called Venable Park, which was a former city park from the 1920s. The block was bound by Ellerslie Avenue to the west, 36th Street to the north, and Ednor Road to the east. Two stadiums were located here; a 1922 version known as Baltimore Stadium or Municipal Stadium (or sometimes Venable Stadium) and, for a time, Babe Ruth Stadium in reference to the then-recently deceased Baltimore native. The rebuilt multi-sport stadium, when reconstruction (expansion to an upper deck) was completed in mid-1954, would become known as Memorial Stadium. The stadium was also known as "The Old Gray Lady of 33rd Street," and also "The World's Largest Outdoor Insane Asylum" when used by the Baltimore Colts.[6] the latter which was coined by Cooper Rollow.[7]

Teams hosted

This pair of structures hosted the following teams:

Baseball

- Baltimore Orioles, International League, mid-season 1944–1953

- Baltimore Orioles, American League, 1954–1991

- United States Congressional Baseball Game, 1973–1976

- Bowie Baysox, Eastern League (Orioles farm club), 1993

Football

Professional

- Baltimore Colts, AAFC 1947–1949, NFL 1950

- Baltimore Colts, National Football League, 1953–1983

- Miami vs New Orleans NFL preseason game, 1992, attracted 60,021 fans

- Baltimore Stallions/Baltimore F.C., Canadian Football League, 1994–1995

- Baltimore Ravens, National Football League, 1996–1997

High school

- Baltimore City College vs Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, Thanksgiving Day 1954–1999, known as "City vs. Poly" or "Poly vs. City".

- Calvert Hall College vs Loyola Blakefield Thanksgiving Day 1957–1999, known as " Calvert Hall vs. Loyola", the Turkey Bowl".

College/University/Military Academies

- Maryland Terrapins football (partial schedule, 1920s-1930s, mostly for games against Johns Hopkins and Western Maryland)

- Navy Midshipmen football (partial schedule, 1920s-1933, 1935-60, 1986, 1988, for games against Army and Notre Dame)

History

Municipal Stadium/Baltimore Stadium/Venable Stadium/Babe Ruth Stadium

Memorial Stadium started out in life as Municipal Stadium, also known as Baltimore Stadium, and as Venable Stadium. Designed by Pleasants Pennington and Albert W. Lewis, it was built in 1922 over a six-month period at the urging of the Mayor, William F. Broening (1870–1953, served 1919–1923, 1927–1931), in a previously undeveloped area just north beyond the city's iconic rows of rowhouses where upon they reached out in the 1920s to many of the largest 19th-century country estates of the wealthy in the northeastern wedge of the city. Constructed in the former Venable Park, established in the early 20th century, the stadium was operated by the city's Board of Park Commissioners on behalf of the Baltimore City Department of Recreation and Parks. It was primarily a football stadium, a large horseshoe with an earthen-mound exterior and its open end with a large stone gateway of a Greek/Roman colonnade and porticoes on the open-faced south side facing the new 33rd Street boulevard/parkway which had just recently been cut through east to west. In this configuration, it seated anywhere from 70,000 to 80,000 people.[8]

In its early years it hosted various public and private high school and college-level games, including the annual "Poly - City Game" on the regular Thanksgiving Day "double-header where the "Collegians" (later known as the "Black Knights" in reference to their iconic "Castle on the Hill") of Baltimore City College opposed its rival Baltimore Polytechnic Institute "Engineers" (since 1889), along with the Roman Catholic high schools' "Loyola - Calvert Hall" Game pitting the Cardinals of Calvert Hall College against Loyola High School at Blakefield's Dons before crowds of school students, parents, alumni and the city's sports fans numbering 30,000. Also occasional home games for the University of Maryland at College Park's "Terrapins" football and the home team favorites United States Naval Academy (at Annapolis) "Midshipmen" versus the United States Military Academy at West Point's "Cadets" (also known later as the "Black Knights") in several Army–Navy Games, attracting a national audience and media coverage.

In mid-summer 1944 it was pressed into service as a baseball park by the Baltimore Orioles of the International League, when their previous long-time home, "Oriole Park" (the fifth to hold the name, and the last to do so until the current incarnation opened in 1992) on the northwest corner at Greenmount Avenue and 29th Street in the Abell neighborhood, to the southwest, was destroyed by a late-night fire in July 1944.

In 1944, the minor league Orioles went on to win the International League championship and the Junior World Series over the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. The large post-season crowds at Municipal Stadium, which would not have been possible at Oriole Park, and which easily surpassed the attendance at major league baseball's own World Series, caught the attention of the Major Leagues and their team owners, and Baltimore suddenly became a viable option for teams looking to move.[9]

Soon after the death of Hall of Famer and Baltimore native Babe Ruth in August, 1948, the venue was renamed "Babe Ruth Stadium". It was renamed again, in late 1949, as "Memorial Stadium", in honor of America's military veterans. The name "Babe Ruth Stadium" remained an unofficial alternate name for some years afterward.

Baltimore Memorial Stadium

Spurred by the Orioles' success, and also by the new presence of professional football, the City chose to rebuild the stadium as a facility of "major league caliber", which they renamed Baltimore Memorial Stadium in honor of the thousands of the city's dead of the recently concluded World War II.[10] Baltimore mayor Thomas L.J. D'Alesandro, Jr. championed the new stadium project and overcame various legal and political hurdles which delayed progress on the project.

The initial plan called for a single, horseshoe-shaped deck to be built, with the open end facing north, and was designed to host football as well as baseball. It was engineered with enough strength to eventually support a second deck and a roof.

The lower deck reconstruction began in the spring/early summer of 1949 and was done in stages, first at the previously open south end of the stadium, and slowly obliterating the old Municipal Stadium stands, even as the International League Orioles continued playing on their makeshift diamond, along with the new Baltimore Colts of the former All-America Football Conference merged with the reorganized National Football League.

The old seating at the north end was retained for the pro and college football seasons that fall. By year's end, the horseshoe was sufficiently completed to allow the baseball infield to be relocated from the northwest corner of the field to the south end, and the Orioles opened the 1950 season at the newly oriented diamond. Construction continued on the single deck, until finally all the remnants of the old stadium were gone. The new facility could seat around 31,000.

With realistic rumors circulating of a return to the major leagues, the second deck construction was begun during the summer of 1953. First, two groups of sections were built facing the 50 yard line. Then they were extended toward the south end, completing the upper deck horseshoe. Additional plans to fully enclose the stadium and add a roof to the upper tier were never implemented, although an extra upper deck section would be added on each side in 1964.

Work accelerated in November 1953 when the St. Louis Browns of the American League were announced to be moving to Baltimore to become the new major league version of the Baltimore Orioles, to begin play in April 1954, the city's first major league franchise in over 50 years (not counting the Federal League experiment). The total cost of the multi-phase project was $6.5 million.

The expanded stadium was still under construction as of opening day in 1954, with the new entrance plaza and the new outfield lighting not yet completed. Work was finally done by late spring/early summer, the crowning touch being the large memorial plaque over the entrance.

On April 15, 1954, thousands of Baltimoreans jammed city streets as the new Orioles paraded from downtown at the Baltimore City Hall to Memorial Stadium for their first home game. During the 90-minute parade, the new "Birds" signed autographs, handed out pictures and threw styrofoam balls to the crowd as the throngs marched down several major city streets ending on East 33rd Street. Inside, more than 46,000 watched the Orioles beat the Chicago White Sox, 3–1, to win their home opener and move into first place (although temporarily) in the American League.[11]

Both the new Orioles and the Colts had some great successes over the next few decades, winning several championships. Among the noteworthy Orioles who played here by the 1960s to 90's were pitcher Jim Palmer, first basemen John (Boog) Powell and Eddie Murray, shortstop Cal Ripken Jr., third baseman Brooks Robinson, and outfielder Frank Robinson. Among the Colts' greats were quarterback Johnny Unitas, wide receiver Raymond Berry, and running backs Alan Ameche and Lenny Moore, as well as tight end John Mackey. Over the next few decades, both teams became among the winningest and competitive franchises in their sports, sending a number of players to their respective Halls of Fame. Following the stunning win of their first championship in what became known as "The Greatest Game Ever Played" versus the New York Giants in the 1958 title game in New York City, the Colts later repeated the accomplishment in the next year's NFL championship game of 1959, which the "Hosses" won, playing at the stadium before a home crowd. It was the enthusiasm of Colts fans in particular that led to the stadium being dubbed "The World's Largest Outdoor Insane Asylum" by Cooper Rollow, the Chicago Tribune's head NFL sports writer at the time.

The stadium was not without its critiques. Traffic and a parking shortage made accessing the stadium difficult. Concrete poles blocked views, and unsheltered areas grew hot in the summer. Most of the seats were bench-style, with few having chair backs.[12]

Fatal escalator accident

On May 2, 1964, a freak accident involving a stadium escalator caused the death of a teenaged girl and injuries to 46 other children. That day, the Orioles held "Safety Patrol Day" to honor schoolchildren who served in their schools' safety patrols, in which they helped their fellow students travel to and from school safely. For the event, 20,000 schoolchildren from around the state of Maryland were given free admission to the Orioles' game against the Cleveland Indians.

While the national anthem was playing before the start of the game, hundreds of children began getting onto an escalator that traveled from the lower deck to the upper deck on the stadium's third base side. Unfortunately, while three or four children at a time were getting on the escalator at the bottom, the top of the escalator was partially blocked by a narrow metal gate that allowed only one person to pass through. The mass of children was thus blocked at the top, and children began falling back on top of one another in a crush of bodies as other children continued to get on at the bottom and as the jagged metal steps of the escalator continued to move beneath all of them. The moving steps cut and mutilated the children until a stadium usher, 65-year-old Melville Gibson, finally reached the escalator's emergency shut-off switch and turned the escalator off. Previously, the shut-off switch had been moved to a wall across from the escalator in order to prevent pranksters from turning it off while people were on it.

A 14-year-old girl, Annette S. Costantini, was killed in the accident. 46 other children were injured, some seriously.

The gate at the top of the escalator — called a "people channeler" — had apparently been left there after a previous event, when the escalator's direction had been switched to move people downward. The gate's purpose was to control the flow of people getting onto the escalator. Shortly before the tragedy, Orioles management had decided to open the stadium's upper deck to Safety Patrol members who were still arriving by game time, after early-arriving children had filled the bleachers. Children heading for the upper deck then got onto the escalator.

It was the worst accident in the history of the stadium.[13][14][15][16]

Airplane crash

A small private airplane crashed on the stadium premises on December 19, 1976, just minutes after the conclusion of an NFL playoff game with the Pittsburgh Steelers. The airplane, a Piper Cherokee, buzzed the stadium, and then crashed into the upper deck overlooking the south end zone.[17] The Steelers had won the game handily (40–14), and most of the fans had already exited the stadium by the time the game ended. There were no serious injuries, and the pilot was arrested for violating air safety regulations.[18][19][20][21] Donald Kroner was the 33-year-old pilot charged with reckless flying, littering, and making a bomb threat against former Baltimore Colts linebacker Bill Pellington. Pellington owned a bar and restaurant from which Kroner was once ejected for using foul language.[22]

The crash is the subject of the 2022 documentary Section 1 by Secret Base's Jon Bois and Alex Rubenstein.[23]

Later years

This section possibly contains original research. (November 2015) |

Robert Irsay, then owner of Los Angeles Rams, and then-current Colts owner Carroll Rosenbloom swapped franchises in 1972. Under the new Irsay regime, the Colts' new general manager Joe Thomas made some daring and ultimately rewarding trades and drafts which again brought the Colts to prominence in the NFL. However, by the late '70s/early '80s, key injuries (especially to their franchise QB, Bert Jones, who ironically wound up going to the Rams) and ill-advised personnel moves by Irsay caused the team's fortunes to sag, and attendance in the modest stadium did as well. Further, neither Irsay nor the city could agree to desperately-needed improvements to the aging and tattered stadium, so Irsay started visiting other cities, seeking to either motivate the city or woo another. Finally, a quick travel stop with a B.W.I. Airport conference was held with City Mayor William Donald Schaefer, which also proved fruitless. Irsay then negotiated with Indiana officials and in Indianapolis with Mayor William H. Hudnut, III, and they stunned the sports world by transferring to Indianapolis, with Mayflower Moving Company moving vans trucking the club's equipment to Indiana in the middle of a snowy night on March 29, 1984, under the threat of a measure introduced into the state legislature to initiate condemnation proceedings for the city and state to assert "eminent domain" and take ownership of the franchise on behalf of the citizens and fans. This event dramatically shifted the political establishment's view on how best to address the later continued stadium upgrade needs of the Orioles, the only remaining tenant.

Community reaction

When the decision to abandon Memorial Stadium (in favor of the new downtown ballpark) became imminent, various citizen groups began to organize opposition to the decision. In particular, the neighborhoods surrounding Memorial Stadium became anxious about the impact on their area of an abandoned "white elephant": there simply wasn't any other use that would generate the funds to properly maintain the site, and there were no funds for demolition and redevelopment. While the stadium events may have created periodic disruptions to local life, it did provide easy access to major league sports and special attention from the city for maintenance of the area.

The mayor and other power brokers knew of strong general public opposition to subsidizing a new ballpark. City-wide and local community leaders also knew of this potential, but there was also a shortage of leaders willing to take on this task (although this was never stated, and may not have been known by Mayor Schaefer). During this pivotal period, local community leaders decided to "bargain away the petition drive" for certain considerations. To do this, area community groups formed the "Stadium Neighborhoods Coalition" (SNC) and negotiated the following: (1) Establishment of an official Memorial Redevelopment Stadium Task Force with public meetings and minutes; and, (2) a written pledge by then Mayor Schaefer to provide upfront funding for any demolition and redevelopment resulting from this community process.

The Orioles played their final game at the stadium on October 6, 1991, which ended in a defeat at the hands of the Detroit Tigers, 7-1; a postgame ceremony was held with 78 past Oriole players meeting, and ended with home plate being removed by the grounds crew and placed in a stretch limousine. It was sent across town to Camden Yards under police escort where it would be placed at the new stadium minutes later.[24]

For the next decade, while the community input process lumbered on, Memorial Stadium hosted a minor league baseball team and two new professional football teams. The Bowie Baysox, a minor league affiliate of the Orioles, played their inaugural 1993 season at Memorial Stadium while their permanent home ballpark was being built. As the Orioles were then in their second season at Camden Yards, this gave Baltimore the rare distinction of hosting both major league and minor league teams simultaneously; currently, New York City has that honor with the presence of the Brooklyn Cyclones, who are affiliated with the Mets.

The Baltimore Stallions played during the Canadian Football League's "southern expansion" experiment to the United States for two seasons in 1994 and 1995. The team was originally known as the "Baltimore CFL Colts", but they were forced to change their name to the Stallions (after one year of playing without an official name) when the NFL was granted a legal court injunction which prevented the CFL franchise from reclaiming the "Colts" name. Owner Jim Speros took over the facility, exchanging tickets to contractors for renovations to help bring the dilapidated stadium to workable condition.[25] Memorial Stadium was unique in that it was one of the few U. S. stadiums that could accommodate the full 65-yard width and 150-yard length of a regulation Canadian football field (most likely since it had been designed for baseball as well as American football). Averaging more than 30,000 spectators a game for two years, the Stallions would eventually become the only American team to win the Grey Cup in 1995.[25]

The CFL Stallions were ultimately forced out of town when Cleveland Browns owner Art Modell announced he was moving his team to Baltimore. Following protracted negotiations between Modell, the two cities and the NFL, it was decided that Modell would be allowed to take his players and organization to Baltimore as the Ravens, while leaving the Browns name and legacy for a replacement team that returned in 1999. The Ravens were tenants of the stadium until the end of the 1997 NFL regular season, when they moved to what is now M&T Bank Stadium. It was bid farewell in style by both the Orioles (in a field-encircling ceremony staged by many former Oriole players and hosted by Hall of Fame announcer Ernie Harwell, who began his announcing career here) and the Ravens (who had many former Colts assemble for a final play, run by Unitas. The play had Unitas hand the ball off to Lydell Mitchell, who then handed the ball to Lenny Moore in a reverse and Moore ran in for a touchdown).

Through all of this, the official Redevelopment Task Force met off and on, deliberating on prospects for long-term use. The community remained quite sensitized about any inappropriate use of this center-of-the-neighborhood structure. When word leaked that the stadium was being considered for staging rock concerts, a group of neighbors organized the group "People Against Concerts at Memorial Stadium" (PACAMS). As Baltimore was deciding to confirm or deny this story—with no immediate answer—a large public opposition developed. With the resulting outpouring of anger, the City publicly confirmed its decision not to lease the site for rock concerts.

In resolving the rock concert problem, a new spirit of proactive advocacy was ignited in the community. In fact, there had been developing a division within established neighborhood groups about the best tactics in securing a good future for the stadium. Should the groups make further use of the direct action tactics of PACAMS, or use quiet lobbying by established groups?

That division was never resolved, as individuals continued to work in different paths. In fact, PACAMS, after its success in preventing the stadium's use for concerts, reconstituted itself as "People Advocating a Community Agenda for Memorial Stadium"—continuing with the successful PACAMS acronym. With PACAMS' public advocacy, and the established groups' holding fast to more traditional lines of community, there ultimately resulted in a large, and well attended, public meeting where several redevelopment proposals were presented. The resulting community preference for a mixed used development led to the successful development now on site.

Demolition and redevelopment

The City of Baltimore solicited proposals for development of the site. Most proposals preserved some or all of the stadium, including the memorial to World War II veterans and words on the facade. One proposal even had a school occupying the former offices of Memorial Stadium and the field used as a recreational facility for the school. Mayor Martin J. O'Malley, however, favored the proposal that resulted in the total razing of the stadium, an act that many fought and protested. Former mayor and governor William Donald Schaefer protested that the stadium was razed for political reasons. The venerable and historic stadium was demolished over a 10-month period beginning in April 2001.[citation needed] Approximately 10,000 cubic yards (7,600 m3) of concrete rubble from it was used to build an artificial reef over a 6-acre (2.4 ha) site in the Chesapeake Bay 3 miles (4.8 km) west of Tolchester Beach in 2002.[26]

As of 2005, the former site of Memorial Stadium housed Maryland's largest YMCA facility and the developing vision of "Stadium Place", a mixed income community for seniors in Baltimore City. Currently there are four senior apartment complexes up and running on site. All of this, the political wranglings, the sports history and the city's attachment to a doomed landmark was captured in a documentary, "The Last Season, The Life and Demolition of Memorial Stadium."

There was also a plan initially to keep the front of the stadium as a dedication to commemorate all who served America during both World Wars, but it had to also be taken down because alone, it was structurally unsafe.[27]

New field

In 2010, work started on developing a new recreational baseball/football field on the site (Cal Ripken Senior Youth Development Field), with home plate being in the same exact location as it was when Memorial Stadium existed.[28] The field was completed in December 2010. A ribbon-cutting ceremony on December 7 was attended by Billy and Cal Ripken, and Governor Martin O'Malley.[29][30]

Layout

The general layout of Memorial Stadium resembled a somewhat scaled-down version of Cleveland Stadium (then home of the MLB Indians and NFL Browns). Due to the need to fit a football field on the premises, the playing area was initially quite large, especially in center field and foul territory. The construction of inner fences after 1958, however, reduced the size of the outfield. The addition of several rows of box seats also reduced the foul ground, ultimately making the stadium much more of a hitters' park than it was originally. It did host the Major League Baseball All-Star Game that year. Memorial Stadium was one of the nation's few venues to host a World Series, an MLB All-Star Game, and an NFL Championship game.

"Here"

The only home run ball ever hit completely out of Memorial Stadium was slugged by Frank Robinson on Mother's Day, May 8, 1966, off Cleveland Indians pitcher Luis Tiant.[31] It cleared the left field single-deck portion of the grandstand.[32] A flag was later erected near the spot the ball cleared the back wall, with simply the word "HERE" upon it.

The ball was retrieved by two children, Mike Sparaco and Bill Wheatley, then returned to Frank Robinson.[33] The flag is now in the Baltimore Orioles "Sports Legends" museum at the old Camden Street Station, adjacent to the new ballpark of 1992.

Memorial wall

The exterior wall of the stadium behind home plate was dominated by the following text, spanning most of the stadium's height facing 33rd Street, as a memorial to those killed in the two world wars:

ERECTED BY THE

CITY OF BALTIMORE

1954

DEDICATED BY

THE MAYOR AND THE CITY COUNCIL

AND THE PEOPLE OF BALTIMORE CITY

IN THE STATE OF MARYLAND

As a Memorial to All

Who so Valiantly Fought

and Served in the World

Wars with Eternal

Gratitude to Those Who

Made the Supreme

Sacrifice to Preserve

Equality and Freedom

Throughout the World

TIME WILL NOT DIM THE GLORY OF THEIR DEEDS

The final line is a quote from Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I and first chairman of the American Battle Monuments Commission, 1923–1948.[34]

The stadium wall and its words were demolished along with the rest of the stadium and thrown into the Chesapeake Bay; the final line was saved and now sits outside Oriole Park at Camden Yards, the Orioles' current stadium. A miniature recreation of the stadium wall also sits outside Oriole Park.

Tenants

Memorial Stadium also hosted several University of Maryland home football games against such opponents as Clemson and Penn State. In 1988, the stadium served as Navy's "home" venue for their annual football game against the Notre Dame Fighting Irish.

The ballpark also served as the home venue for Baltimore's two North American Soccer League teams, the Bays (1967–1968) and the Comets (1974). Unlike the football gridiron which was situated from home plate to center field, the soccer pitch was laid out with the right field foul line doubling as an end line, the other one in deep left field and the pitching mound out of bounds. It also hosted the first game of the NPSL Final 1967.

The Canadian Football League's Baltimore Stallions also played at Memorial Stadium in 1994 and 1995.

Attendance

| Baltimore Orioles Attendance at Memorial Stadium[35] | ||||

| Year | Total attendance | Game average | AL rank | |

| 1954 | 1,060,910 | 13,778 | 5th | |

| 1955 | 852,039 | 10,785 | 7th | |

| 1956 | 901,201 | 11,704 | 6th | |

| 1957 | 1,029,581 | 13,371 | 5th | |

| 1958 | 829,991 | 10,641 | 5th | |

| 1959 | 891,926 | 11,435 | 7th | |

| 1960 | 1,187,849 | 15,427 | 3rd | |

| 1961 | 951,089 | 11,599 | 5th | |

| 1962 | 790,254 | 9,637 | 6th | |

| 1963 | 774,343 | 9,560 | 7th | |

| 1964 | 1,116,215 | 13,612 | 4th | |

| 1965 | 781,649 | 9,894 | 6th | |

| 1966 | 1,203,366 | 15,232 | 3rd | |

| 1967 | 955,053 | 12,403 | 6th | |

| 1968 | 943,977 | 11,800 | 6th | |

| 1969 | 1,062,069 | 13,112 | 5th | |

| 1970 | 1,057,069 | 13,050 | 6th | |

| 1971 | 1,023,037 | 13,286 | 3rd | |

| 1972 | 899,950 | 11,688 | 6th | |

| 1973 | 958,667 | 11,835 | 9th | |

| 1974 | 962,572 | 11,884 | 8th | |

| 1975 | 1,002,157 | 13,015 | 9th | |

| 1976 | 1,058,609 | 13,069 | 6th | |

| 1977 | 1,195,769 | 14,763 | 10th | |

| 1978 | 1,051,724 | 12,984 | 10th | |

| 1979 | 1,681,009 | 21,279 | 6th | |

| 1980 | 1,797,438 | 22,191 | 6th | |

| 1981 | 1,024,247 | 18,623 | 8th | |

| 1982 | 1,613,031 | 19,671 | 8th | |

| 1983 | 2,042,071 | 25,211 | 5th | |

| 1984 | 2,045,784 | 25,257 | 5th | |

| 1985 | 2,132,387 | 26,326 | 6th | |

| 1986 | 1,973,176 | 24,977 | 6th | |

| 1987 | 1,835,692 | 22,386 | 9th | |

| 1988 | 1,660,738 | 20,759 | 10th | |

| 1989 | 2,535,208 | 31,299 | 4th | |

| 1990 | 2,415,189 | 30,190 | 5th | |

| 1991 | 2,552,753 | 31,515 | 5th | |

Seating capacity

|

|

Gallery

See also

References

- ^ "Origin & Functions". Maryland Stadium Authority. Retrieved April 30, 2012.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Eggener, Keith. "The Demolition and Afterlife of Baltimore Memorial Stadium," Places Journal, October 2012. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ "J. L. Faisant Dies at 60," The Baltimore Sun, Monday, February 5, 1962. Retrieved October 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Memorial Stadium". Ballparks.com. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ Cooper Rollow, Chicago Tribune, 1959

- ^ Goldsborough, Bob. "Cooper Rollow, 1925–2013," Chicago Tribune, Monday, April 1, 2013. Retrieved March 1, 2023.

- ^ Lowry, Phillip (2005). Green Cathedrals. New York City: Walker & Company. p. 16. ISBN 0-8027-1562-1 – via Google Books.

- ^ Flynn, Tom (2008). Baseball in Baltimore. Maryland: Arcadia Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 9780738553252 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Memorial Stadium Title Approved". The Baltimore Sun. December 6, 1949. Retrieved August 13, 2023.

The municipal stadium was today named Baltimore Memorial Stadium as a tribute to the city's World War II dead.

- ^ APRIL, 1954 | BaseballLibrary.com Archived December 23, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dedford, Frank (April 12, 1971). "Best Damn Team in Baseball". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

- ^ Alvarez, Rafael (July 28, 1991). "In fans' memories, tragedies echo among the cheers". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ "46 hurt; 1 dead in escalator jam Saturday". The Gettysburg Times. Associated Press. May 4, 1964. Retrieved February 26, 2014.

- ^ "Child Dies in Escalator Accident". Star-Banner. Ocala, Florida. Associated Press. May 3, 1964. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "Girl Killed in Escalator Jam". Montreal Gazette. Associated Press. May 4, 1964. Retrieved May 23, 2014.

- ^ "A year in sports". Sports Illustrated. (photo). February 17, 1977. p. 47.

- ^ "Rout was a blessing when plane crashed". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). UPI. December 20, 1976. p. 1B.

- ^ "Touch Down". Milwaukee Journal. (Washington Star Service). December 20, 1976. p. 13, part 2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Small plane crashes into stand minutes after 60,000 leave". Toledo Blade. (Ohio). Associated Press. December 20, 1976. p. 1.

- ^ "Baltimore Stadium". check-six.com.

- ^ Tom (November 11, 2013). "Plane Crashes Into Memorial Stadium". Ghosts of Baltimore. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

- ^ Section 1: A short film from Dorktown, retrieved June 26, 2022

- ^ Brown, Jr., Thomas. "October 6, 1991: Orioles play their final game at Memorial Stadium". sabr.org. Society of American Baseball Research. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ a b Capital News Service. "Baltimore's Forgotten Champions: An Oral History". cnsmaryland.org.

- ^ Meany, Eric (December 28, 2013). "Placement of reef balls on Memorial Stadium rubble to continue for at least five more years". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 31, 2013.

- ^ "Memorial Stadium is still here, just look around". MLB.com. Retrieved January 9, 2022.

- ^ "Stadium Place YMCA". Ripken Design. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ "Joy of sports coming back to the Old Memorial Stadium". WMAR. Baltimore. December 7, 2010. Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ Sharrow, Ryan (December 7, 2010). "Ripken Sr. Foundation completes Memorial Stadium youth field". Baltimore Business Journal.

- ^ 100 Things Orioles Fans Should Know and Do Before They Die, Dan Connolly, Triumph Books, Chicago, 2015, ISBN 978-1-62937-041-5, p.117

- ^ "Retrosheet Boxscore: Baltimore Orioles 8, Cleveland Indians 3 (2)". www.retrosheet.org.

- ^ Klingaman, Mike (May 6, 2016). "Remembering Frank Robinson's historic, outside-the-park home run, 50 years later". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ "St. Mihiel American Cemetery and Memorial" (PDF). Visitor Brochures. American Battle Monuments Commission. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2013. Retrieved October 27, 2013.

The Commission works to fulfill the vision of its first chairman, General of the Armies John J. Pershing. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I, promised that 'time will not dim the glory of their deeds.'

- ^ "Baltimore Orioles Attendance, Stadiums, and Park Factors". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved October 6, 2022.

- ^ "Memorial Stadium". Stadiums of Pro Football. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Elliot, James C. (November 11, 1957). "N.F.L. Sets Crowd Mark". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Bowen, George (December 27, 1959). "Explosive Teams Meet For Pro Football Title". Times Daily.

- ^ "Colts Defeat Rams, 31 to 17". Chicago Tribune. October 17, 1960. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Rollow, Cooper (November 6, 1961). "Packers Lose, Bears "Boot" Chance". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Rollow, Cooper (October 29, 1962). "Green Bay Wins; Giants Stop Redskins". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ "Pro Football Headed for a Banner Season". The Telegraph. August 18, 1963. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ "Colts-Vikings Game Sold Out". The New York Times. November 7, 1964. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ Snyder, Cameron C. (November 17, 1968). "Colts Favored By 14 Over Cardinals Here Today". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ "Facts of AFC Game". The New York Times. January 3, 1971. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- ^ "National Football League (NFL) – Indianapolis Colts". Rauzulu's Street. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ The NFL Media Information Book, 1983. Workman Publishing Company. 1983. p. 38. ISBN 978-0-89-480367-3.

- ^ Morgan, Jon (August 28, 1996). "Ravens' Prices Among NFL Elite $243.11 for Family of Four Is 4th Highest in League, Survey Says". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Tom (March 3, 2014). "The Ghosts of Old Memorial Stadium". Ghosts of Baltimore. Retrieved February 19, 2019.

Sources

- House of Magic, by the Baltimore Orioles

- The Home Team, by James H. Bready

External links

- Memorial Stadium Demolition

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. MD-1111, "Baltimore Memorial Stadium, 1000 East Thirty-third Street, Baltimore, Baltimore (Independent City), MD"

- The Ghosts of Old Memorial Stadium - Series of old photographs from Ghosts of Baltimore blog

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by | Home of the Baltimore Orioles (minor league) July 4, 1944–1953 |

Succeeded by Final stadium

|

| Preceded by First stadium

|

Home of the Baltimore Colts 1953–1983 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Baltimore Orioles 1954–1991 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Host of the All-Star Game 1958 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the United States Congressional Baseball Game 1973–1976 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by | Home of the Bowie Baysox 1993 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by First stadium

|

Home of the Baltimore Stallions 1994–1995 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by first stadium

|

Home of the Baltimore Ravens 1996–1997 |

Succeeded by |

| Preceded by First stadium

|

Host of AFC Championship Game 1971 |

Succeeded by |

- Sports venues completed in 1950

- Sports venues demolished in 2001

- Sports venues demolished in 2002

- 1950 establishments in Maryland

- 1997 disestablishments in Maryland

- Baltimore Orioles stadiums

- Baltimore Ravens stadiums

- Baltimore Colts stadiums

- Baltimore Bays sports facilities

- Canadian Football League venues

- Demolished sports venues in Maryland

- Defunct American football venues in the United States

- Defunct baseball venues in the United States

- Defunct multi-purpose stadiums in the United States

- Defunct college football venues

- Defunct National Football League venues

- Defunct Canadian football venues

- Defunct Major League Baseball venues

- Defunct minor league baseball venues

- Sports venues in Baltimore

- American football venues in Maryland

- Baseball venues in Maryland

- Multi-purpose stadiums in the United States

- Maryland Terrapins football venues

- Navy Midshipmen football venues

- Historic American Buildings Survey in Baltimore

- North American Soccer League (1968–1984) stadiums

- Demolished buildings and structures in Baltimore

- Canadian football venues in the United States

- Multi-purpose stadiums