Anti-capitalism

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economic system, such as socialism or communism.

History of movements

Anti-capitalism was widespread among workers in the United States in the 1900s and 1910s, and Colorado was especially known as a center of anti-capitalist labor movements in that era.[1]

Socialism

Socialism advocates public or direct worker ownership and administration of the means of production and allocation of resources, and a society characterized by equal access to resources for all individuals, with an egalitarian method of compensation.[2][3]

- A theory or policy of social organisation which aims at or advocates the ownership and democratic control of the means of production, by workers or the community as a whole, and their administration or distribution in the interests of all.

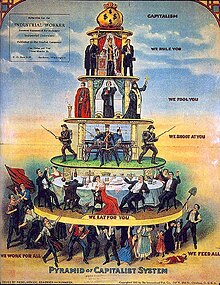

- Socialists argue for a worker cooperative/community economy, or the commanding heights of the economy,[4] with democratic control by the people over the state, although there have been some undemocratic philosophies. "State" or "worker cooperative" ownership is in fundamental opposition to "private" ownership of means of production, which is a defining feature of capitalism. Most socialists argue that capitalism unfairly concentrates power, wealth and profit, among a small segment of society that controls capital and derives its wealth through exploitation.

Socialists argue that the accumulation of capital generates waste through externalities that require costly corrective regulatory measures. They also point out that this process generates wasteful industries and practices that exist only to generate sufficient demand for products to be sold at a profit (such as high-pressure advertisement); thereby creating rather than satisfying economic demand.[5][6]

Socialists argue that capitalism consists of irrational activity, such as the purchasing of commodities only to sell at a later time when their price appreciates, rather than for consumption, even if the commodity cannot be sold at a profit to individuals in need; they argue that making money, or accumulation of capital, does not correspond to the satisfaction of demand.[5]

Private ownership imposes constraints on planning, leading to inaccessible economic decisions that result in immoral production, unemployment and a tremendous waste of material resources during crisis of overproduction. According to socialists, private property in the means of production becomes obsolete when it concentrates into centralized, socialized institutions based on private appropriation of revenue (but based on cooperative work and internal planning in allocation of inputs) until the role of the capitalist becomes redundant.[7] With no need for capital accumulation and a class of owners, private property in the means of production is perceived as being an outdated form of economic organization that should be replaced by a free association of individuals based on public or common ownership of these socialized assets.[8] Socialists view private property relations as limiting the potential of productive forces in the economy.[9]

Early socialists (Utopian socialists and Ricardian socialists) criticized capitalism for concentrating power and wealth within a small segment of society,[10] and for not utilising available technology and resources to their maximum potential in the interests of the public.[9]

Anarchism and libertarian socialism

For the influential German individualist anarchist philosopher Max Stirner, "private property is a spook" which "lives by the grace of law" and it "becomes 'mine' only by effect of the law". In other words, private property exists purely "through the protection of the State, through the State's grace." Recognising its need for state protection, Stirner argued that "[i]t need not make any difference to the 'good citizens' who protects them and their principles, whether an absolute King or a constitutional one, a republic, if only they are protected. And what is their principle, whose protector they always 'love'? Not that of labour", rather it is "interest-bearing possession ... labouring capital, therefore ... labour certainly, yet little or none at all of one's own, but labour of capital and of the—subject labourers."[12] French anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon opposed government privilege that protects capitalist, banking and land interests, and the accumulation or acquisition of property (and any form of coercion that led to it) which he believed hampers competition and keeps wealth in the hands of the few. The Spanish individualist anarchist Miguel Giménez Igualada saw:[13]

capitalism [as] an effect of government; the disappearance of government means capitalism falls from its pedestal vertiginously...That which we call capitalism is not something else but a product of the State, within which the only thing that is being pushed forward is profit, good or badly acquired. And so to fight against capitalism is a pointless task, since be it State capitalism or Enterprise capitalism, as long as Government exists, exploiting capital will exist. The fight, but of consciousness, is against the State.

Within anarchism there emerged a critique of wage slavery, which refers to a situation perceived as quasi-voluntary slavery,[14] where a person's livelihood depends on wages, especially when the dependence is total and immediate.[15][16] It is a negatively connoted term used to draw an analogy between slavery and wage labor by focusing on similarities between owning and renting a person. The term wage slavery has been used to criticize economic exploitation and social stratification, with the former seen primarily as unequal bargaining power between labor and capital (particularly when workers are paid comparatively low wages, e.g. in sweatshops),[17] and the latter as a lack of workers' self-management, fulfilling job choices and leisure in an economy.[18][19][20] Libertarian socialists believe if freedom is valued, then society must work towards a system in which individuals have the power to decide economic issues along with political issues. Libertarian socialists seek to replace unjustified authority with direct democracy, voluntary federation, and popular autonomy in all aspects of life,[21] including physical communities and economic enterprises. With the advent of the Industrial Revolution, thinkers such as Proudhon and Marx elaborated the comparison between wage labor and slavery in the context of a critique of societal property not intended for active personal use,[22][23] Luddites emphasized the dehumanization brought about by machines, while later American anarchist Emma Goldman famously denounced wage slavery by saying: "The only difference is that you are hired slaves instead of block slaves."[11] Goldman believed that the economic system of capitalism was incompatible with human liberty. "The only demand that property recognizes," she wrote in Anarchism and Other Essays, "is its own gluttonous appetite for greater wealth, because wealth means power; the power to subdue, to crush, to exploit, the power to enslave, to outrage, to degrade."[24] She also argued that capitalism dehumanized workers, "turning the producer into a mere particle of a machine, with less will and decision than his master of steel and iron."[24]

Noam Chomsky contends that there is little moral difference between chattel slavery and renting one's self to an owner or "wage slavery". He feels that it is an attack on personal integrity that undermines individual freedom. He holds that workers should own and control their workplace.[25] Many libertarian socialists argue that large-scale voluntary associations should manage industrial manufacture, while workers retain rights to the individual products of their labor.[26] As such, they see a distinction between the concepts of "private property" and "personal possession". Whereas "private property" grants an individual exclusive control over a thing whether it is in use or not, and regardless of its productive capacity, "possession" grants no rights to things that are not in use.[27]

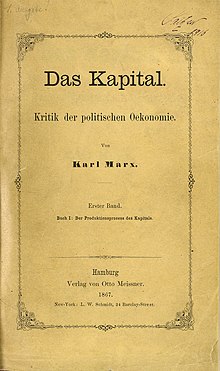

In addition to individualist anarchist Benjamin Tucker's "big four" monopolies (land, money, tariffs, and patents), Kevin Carson argues that the state has also transferred wealth to the wealthy by subsidizing organizational centralization, in the form of transportation and communication subsidies. He believes that Tucker overlooked this issue due to Tucker's focus on individual market transactions, whereas Carson also focuses on organizational issues. Carson holds that "capitalism, arising as a new class society directly from the old class society of the Middle Ages, was founded on an act of robbery as massive as the earlier feudal conquest of the land. It has been sustained to the present by continual state intervention to protect its system of privilege without which its survival is unimaginable."[28] Carson coined the pejorative term "vulgar libertarianism", a phrase that describes the use of a free market rhetoric in defense of corporate capitalism and economic inequality. According to Carson, the term is derived from the phrase "vulgar political economy", which Karl Marx described as an economic order that "deliberately becomes increasingly apologetic and makes strenuous attempts to talk out of existence the ideas which contain the contradictions [existing in economic life]."[29]

Marxism

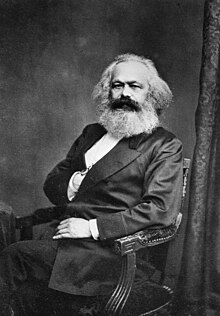

Karl Marx saw capitalism as a historical stage, once progressive but which would eventually stagnate due to internal contradictions and would eventually be followed by socialism. Marx claimed that capitalism was nothing more than a necessary stepping stone for the progression of man, which would then face a political revolution before embracing the classless society.[30]

Contemporary anti-capitalism

Inspired by Marxist thought, the Frankfurt School in Germany was established in 1923, with the purpose of analyzing the superstructure. Marx defined the superstructure as the social stratification and mores reflecting the economic base of capitalism. Through the 1930s, the Frankfurt School, led by thinkers such as Herbert Marcuse and Max Horkheimer created the philosophical movement of critical theory. Later, Critical theorist Jürgen Habermas noted that the universality of modern worldviews posed a threat to marginalized perspectives outside of western rationality. While Critical Theory emphasized the social issues stemming from capitalism with intention towards liberating humanity, it did not directly offer an alternative economic model. Instead its analysis shifted attention to the reinforcement of existing power dynamics through statecraft and a complicit citizenry.

In turn, Critical Theory inspired postmodern philosophers such as Michel Foucault to conceptualize how we form identities through social interaction.[31] During the 1960s and 1970s the global political movement called the New Left explored what liberation entailed through social activism on behalf of these identities. Therefore, socialist identifying movements critical of capitalism extended their reach beyond purely economic considerations and became involved in anti-war and civil rights movements. Later this postmodern activism centered around identities regarding ethnicity, gender, orientation, and race would influence more direct anti-capitalist movements.[32]

New critiques of capitalism also developed in accordance with modern concerns. Anti-globalization and alter-globalization oppose what they view as the sweeping neoliberal and pro-corporate capitalism that spread internationally in the wake of the Soviet Union's fall. They are particularly critical of international financial institutions and regulations such as the IMF, WTO, and free trade agreements. In response they promote the autonomy of sovereign people and the importance of environmental concerns as priorities over international market participation. Notable examples of contemporary anti-globalist movements include Mexico's EZLN. The World Social Forum, began in 2002, is an annual international event dedicated to countering capitalist globalization through networking of attending organizations.[33]

According to historian Gary Gerstle, the ideological space for anti-capitalism in the United States shrank significantly with the end of the Cold War and the globalization of capitalism, forcing the left to "redefine their radicalism in alternative terms" by heavily focusing on multiculturalism and partisan culture war issues, which "turned out to be those that the capitalist system could more, rather than less, easily manage."[34] Late philosopher Mark Fisher referred to this phenomenon as capitalist realism: "the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it."[35]

See also

- Accumulation by dispossession

- Adbusters

- Alter-globalization

- Anti-Capitalist Convergence

- Anti-consumerism

- Anti-globalization

- Christian views on poverty and wealth

- Fascist economy

- Degrowth

- Distributism

- Eye of a needle

- Global justice movement

- Hairshirt environmentalism

- Islamic views on poverty

- List of anti-capitalist and communist parties with national parliamentary representation

- New Anticapitalist Party

- Post-capitalism

- Real utopias

- Religious economy

- Religious views on capitalism

- Social democracy

- Solidarity economy

- Syndicalism

- Hatari (band)

References

- ^ Andrews, Thomas G. (2008). Killing for Coal: America's Deadliest Labor War. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-674-03101-2.

- ^ Newman, Michael. (2005) Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280431-6

- ^ "Socialism". Oxford English Dictionary.

- ^ "Socialism". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008.

- ^ a b "Let's produce for use, not profit". socialist standard. May 2010. Archived from the original on July 16, 2010.

- ^ Fred Magdoff and Michael D. Yates. "What Needs To Be Done: A Socialist View". Monthly Review. Retrieved 2014-02-23.

- ^ Engels, Fredrich. Socialism: Utopian and Scientific. Retrieved October 30, 2010, from Marxists.org: http://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1880/soc-utop/ch03.htm, "The bourgeoisie demonstrated to be a superfluous class. All its social functions are now performed by salaried employees."

- ^ The Political Economy of Socialism, by Horvat, Branko. 1982. Chapter 1: Capitalism, The General Pattern of Capitalist Development (pp. 15–20)

- ^ a b Marx and Engels Selected Works, Lawrence and Wishart, 1968, p. 40. Capitalist property relations put a "fetter" on the productive forces.

- ^ in Encyclopædia Britannica (2009). Retrieved October 14, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/551569/socialism, "Main" summary: "Socialists complain that capitalism necessarily leads to unfair and exploitative concentrations of wealth and power in the hands of the relative few who emerge victorious from free-market competition—people who then use their wealth and power to reinforce their dominance in society."

- ^ a b Goldman 2003, p. 283.

- ^ Lorenzo Kom'boa Ervin. "G.6 What are the ideas of Max Stirner? in An Anarchist FAQ". Infoshop.org. Archived from the original on 2010-11-23. Retrieved 2010-09-20.

- ^ Igualada, Miguel Gimenez. "Anarquismo" [Anarchism] (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-01-31. Retrieved 2014-03-31.

el capitalismo es sólo el efecto del gobierno; desaparecido el gobierno, el capitalismo cae de su pedestal vertiginosamente...Lo que llamamos capitalismo no es otra cosa que el producto del Estado, dentro del cual lo único que se cultiva es la ganancia, bien o mal habida. Luchar, pues, contra el capitalismo es tarea inútil, porque sea Capitalismo de Estado o Capitalismo de Empresa, mientras el Gobierno exista, existirá el capital que explota. La lucha, pero de conciencias, es contra el Estado.

[capitalism [as] an effect of government; the disappearance of government means capitalism falls from its pedestal vertiginously...That which we call capitalism is not something else but a product of the State, within which the only thing that is being pushed forward is profit, good or badly acquired. And so to fight against capitalism is a pointless task, since be it State capitalism or Enterprise capitalism, as long as Government exists, exploiting capital will exist. The fight, but of consciousness, is against the State.] - ^ Ellerman 1992.

- ^ "wage slave". merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ "wage slave". dictionary.com. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Sandel 1996, p. 184.

- ^ "Conversation with Noam Chomsky". Globetrotter.berkeley.edu. p. 2. Archived from the original on 2019-09-19. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ^ Hallgrimsdottir & Benoit 2007.

- ^ "The Bolsheviks and Workers Control, 1917–1921: The State and Counter-revolution". Spunk Library. Retrieved 4 March 2013.

- ^ Harrington, Austin, et al. Encyclopedia of Social Theory Routledge (2006) p. 50

- ^ Proudhon 1890.

- ^ Marx 1969, Chapter VII

- ^ a b Goldman, Emma. Anarchism and Other Essays. 3rd ed. 1917. New York: Dover Publications Inc., 1969., p. 54.

- ^ "Conversation with Noam Chomsky, p. 2 of 5". Globetrotter.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on September 19, 2019. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ^ Lindemann, Albert S. (1983). A History of European Socialism. Yale University Press. p. 160.

- ^ Ely, Richard; et al. (1914). Property and Contract in Their Relations to the Distribution of Wealth. The Macmillan Company.

- ^ Richman, Sheldon, Libertarian Left Archived 2011-08-14 at the Wayback Machine, The American Conservative (March 2011)

- ^ Marx 1969, p. 501.

- ^ Wallerstein, Immanuel (September 1974). "The Rise and Future Demise of the World Capitalist System: Concepts for Comparative Analysis". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 16 (4): 387–415. doi:10.1017/S0010417500007520. S2CID 73664685.

- ^ Agger, Ben (1991). "Critical Theory, Poststructuralism, Postmodernism: Their Sociological Relevance". Annual Review of Sociology. 17: 105–131. doi:10.1146/annurev.so.17.080191.000541. JSTOR 2083337.

- ^ Farred, Grant (2000). "Endgame Identity? Mapping the New Left Roots of Identity Politics". New Literary History. 31 (4): 627–648. doi:10.1353/nlh.2000.0045. JSTOR 20057628. S2CID 144650061.

- ^ Gilbert, Jeremy (2008). "Another World Is Possible: The Anti-Capitalist Movement". Anticapitalism and culture: radical theory and popular politics. Berg. pp. 75–106. ISBN 978-1-84788-451-0.

- ^ Gerstle 2022, p. 149.

- ^ Fisher 2009, p. 2.

Bibliography

- Ellerman, David P. (1992). Property and Contract in Economics: The Case for Economic Democracy (PDF). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-309-6. Retrieved 9 March 2013.

- Fisher, Mark (2009). Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative?. John Hunt Publishing. ISBN 978-1846943171.

- Gerstle, Gary (2022). The Rise and Fall of the Neoliberal Order: America and the World in the Free Market Era. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0197519646.

- Goldman, Emma (2003). Falk, Candace; et al. (eds.). Emma Goldman: A Documentary History of the American Years, Volume I: Made for America, 1890–1901. Berkeley & Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-08670-8.

- Hallgrimsdottir, Helga Kristin; Benoit, Cecilia (2007). "From Wage Slaves to Wage Workers: Cultural Opportunity Structures and the Evolution of the Wage Demands of the Knights of Labor and the American Federation of Labor, 1880–1900". Social Forces. 85 (3): 1393–1411. doi:10.1353/sof.2007.0037. JSTOR 4494978. S2CID 154551793.

- Sandel, Michael J. (1996). Democracy's Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-19744-2.

- Marx, Karl (1969) [1863]. Theories of Surplus Value. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Proudhon, Pierre-Joseph (1890) [1840]. What Is Property? or, An Inquiry into the Principle of Right and of Government. New York, NY: Humboldt Publishing.

Further reading

- Ezequiel Adamovsky. Anti-capitalism. Seven Stories Press. 2011

- Alex Callinicos. An Anti-Capitalist Manifesto. Polity. 2003

- Emma Goldman. Anarchism and other essays. Mother Earth Publishing Association. 1910

- David E Lowes. The Anti-Capitalist Dictionary. Zed Books. 2006

- David McNally. Another World Is Possible: Globalization and Anti-Capitalism. Arbeiter Ring Publishing. 2006

- Ludwig von Mises. The Anti-Capitalistic Mentality. Mises Institute. 1956

- Sanders, Bernie (2023). It's OK to Be Angry About Capitalism. Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0593238714.

- Simon Tormey. Anti-Capitalism: A Beginner's Guide. Oneworld Publications. 2013

- Chris Williams. Ecology and Socialism. Haymarket Books. 2010

External links

- Anti-capitalism: theory and practice by Chris Harman, SWP (2000).

- Rough Guide to the Anti-Capitalist Movement, League for the Fifth International

- Rifkin, Jeremy (15 March 2014). "The Rise of Anti-Capitalism". The New York Times.

- Infoshop.org Anarchists Opposed to Capitalism, Infoshop.org

- How The Miners Were Robbed 1907 anti-capitalist pamphlet hosted at EconomicDemocracy

- Sam Ashman "The anti-capitalist movement and the war" Archived 2022-03-28 at the Wayback Machine International Socialist Journal 2003

- Marxists Internet Archive

- Dr. Wladyslaw Jan Kowalski Anti-Capitalism: Modern Theory and Historical Origins

- Aufheben, Anti-Capitalism as an ideology... and as a movement, Libcom.org

- Studies in Anti-Capitalism

- How to Be an Anticapitalist Today. Erik Olin Wright for Jacobin. December 2, 2015.

- Infographic: Where People Are Losing Faith In Capitalism. International Business Times. January 27, 2020.