Magnesium hydroxide

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Magnesium hydroxide

| |

| Other names

Magnesium dihydroxide

Milk of magnesia | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.013.792 |

| EC Number |

|

| E number | E528 (acidity regulators, ...) |

| 485572 | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| Mg(OH)2 | |

| Molar mass | 58.3197 g/mol |

| Appearance | White solid |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Density | 2.3446 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 350 °C (662 °F; 623 K) decomposes |

| |

Solubility product (Ksp)

|

5.61×10−12 |

| −22.1·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Refractive index (nD)

|

1.559[1] |

| Structure | |

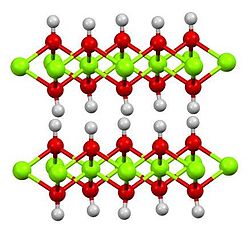

| Hexagonal, hP3[2] | |

| P3m1 No. 164 | |

a = 0.312 nm, c = 0.473 nm

| |

| Thermochemistry | |

Heat capacity (C)

|

77.03 J/mol·K |

Std molar

entropy (S⦵298) |

64 J·mol−1·K−1[3] |

Std enthalpy of

formation (ΔfH⦵298) |

−924.7 kJ·mol−1[3] |

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵)

|

−833.7 kJ/mol |

| Pharmacology | |

| A02AA04 (WHO) G04BX01 (WHO) | |

| Hazards | |

| GHS labelling: | |

[4] [4]

| |

| Warning[4] | |

| H315, H319, H335[4] | |

| P261, P280, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P405, P501[4] | |

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |

| Flash point | Non-flammable |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

8500 mg/kg (rat, oral) |

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | External MSDS |

| Related compounds | |

Other anions

|

Magnesium oxide |

Other cations

|

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Magnesium hydroxide is the inorganic compound with the chemical formula Mg(OH)2. It occurs in nature as the mineral brucite. It is a white solid with low solubility in water (Ksp = 5.61×10−12).[5] Magnesium hydroxide is a common component of antacids, such as milk of magnesia.

Preparation

Combining a solution of many magnesium salts with alkaline water induces precipitation of solid Mg(OH)2:

- Mg2+ + 2 OH− → Mg(OH)2

On a commercial scale, Mg(OH)2 is produced by treating seawater with lime (Ca(OH)2). 600 m3 (158,503 US gallons) of seawater gives about one ton of Mg(OH)2. Ca(OH)2 is far more soluble than Mg(OH)2, so the latter precipitates as a solid:[6]

Uses

Precursor to MgO

Most Mg(OH)2 that is produced industrially, as well as the small amount that is mined, is converted to fused magnesia (MgO). Magnesia is valuable because it is both a poor electrical conductor and an excellent thermal conductor.[6]

Health

Metabolism

Magnesium hydroxide is used in suspension as either an antacid or a laxative, depending on concentration.

As an antacid, magnesium hydroxide is dosed at approximately 0.5–1.5 g in adults and works by simple neutralization, where the hydroxide ions from the Mg(OH)2 combine with acidic H+ ions produced in the form of hydrochloric acid by parietal cells in the stomach to produce water.

As a laxative, magnesium hydroxide is dosed at 2–5 g, and works in a number of ways. First, Mg2+ is poorly absorbed from the intestinal tract, so it draws water from the surrounding tissue by osmosis. Not only does this increase in water content soften the feces, it also increases the volume of feces in the intestine (intraluminal volume) which naturally stimulates intestinal motility. Furthermore, Mg2+ ions cause the release of cholecystokinin (CCK), which results in intraluminal accumulation of water, electrolytes, and increased intestinal motility. Some sources claim that the hydroxide ions themselves do not play a significant role in the laxative effects of milk of magnesia, as basic solutions (i.e., solutions of hydroxide ions) are not strongly laxative, and non-basic Mg2+ solutions, like MgSO4, are equally strong laxatives, mole for mole.[7]

Only a small amount of the magnesium from magnesium hydroxide is usually absorbed by the intestine (unless one is deficient in magnesium). However, magnesium is mainly excreted by the kidneys so long-term, daily consumption of milk of magnesia by someone suffering from kidney failure could lead in theory to hypermagnesemia. Unabsorbed drug is excreted in feces; absorbed drug is excreted rapidly in urine.[8]

History of milk of magnesia

On May 4, 1818, American inventor John Callen received a patent (No. X2952) for magnesium hydroxide.[9] In 1829, Sir James Murray used a "condensed solution of fluid magnesia" preparation of his own design[10] to treat the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Marquis of Anglesey, of stomach pain. This was so successful (advertised in Australia and approved by the Royal College of Surgeons in 1838)[11] that he was appointed resident physician to Anglesey and two subsequent Lords Lieutenant, and knighted. His fluid magnesia product was patented two years after his death in 1873.[12]

The term milk of magnesia was first used by Charles Henry Phillips in 1872 for a suspension of magnesium hydroxide formulated at about 8%w/v.[13] It was sold under the brand name Phillips' Milk of Magnesia for medicinal usage.

Although the name may at some point have been owned by GlaxoSmithKline, USPTO registrations show "Milk of Magnesia"[14] and "Phillips' Milk of Magnesia"[15] have both been assigned to Bayer since 1995. In the UK, the non-brand (generic) name of "Milk of Magnesia" and "Phillips' Milk of Magnesia" is "Cream of Magnesia" (Magnesium Hydroxide Mixture, BP).

It was used in Steven Spielberg's first short movie called Amblin'.

As food additive

It is added directly to human food, and is affirmed as generally recognized as safe by the FDA.[16] It is known as E number E528.

Magnesium hydroxide is marketed for medical use as chewable tablets, as capsules, powder, and as liquid suspensions, sometimes flavored. These products are sold as antacids to neutralize stomach acid and relieve indigestion and heartburn. It also is a laxative to alleviate constipation. As a laxative, the osmotic force of the magnesia acts to draw fluids from the body. High doses can lead to diarrhea, and can deplete the body's supply of potassium, sometimes leading to muscle cramps.[17]

Some magnesium hydroxide products sold for antacid use (such as Maalox) are formulated to minimize unwanted laxative effects through the inclusion of aluminum hydroxide, which inhibits the contractions of smooth muscle cells in the gastrointestinal tract,[18] thereby counterbalancing the contractions induced by the osmotic effects of the magnesium hydroxide.

Other niche uses

Magnesium hydroxide is also a component of antiperspirant.[19] Magnesium hydroxide is useful against canker sores (aphthous ulcer) when used topically.[20]

Waste water treatment

Magnesium hydroxide powder is used industrially to neutralize acidic wastewaters.[21] It is also a component of the Biorock method of building artificial reefs.

Fire retardant

Natural magnesium hydroxide (brucite) is used commercially as a fire retardant. Most industrially used magnesium hydroxide is produced synthetically.[22] Like aluminium hydroxide, solid magnesium hydroxide has smoke suppressing and flame retardant properties. This property is attributable to the endothermic decomposition it undergoes at 332 °C (630 °F):

- Mg(OH)2 → MgO + H2O

The heat absorbed by the reaction retards the fire by delaying ignition of the associated substance. The water released dilutes combustible gases. Common uses of magnesium hydroxide as a flame retardant include additives to cable insulation (i.e. cables for high quality cars, submarines, the Airbus A380, Bugatti Veyron and the PlayStation 4, PlayStation 2, etc.), insulation plastics, roofing (e.g. London Olympic Stadium), and various flame retardant coatings. Other mineral mixtures that are used in similar fire retardant applications are natural mixtures of huntite and hydromagnesite.[23][24][25][26][27]

Mineralogy

Brucite, the mineral form of Mg(OH)2 commonly found in nature also occurs in the 1:2:1 clay minerals amongst others, in chlorite, in which it occupies the interlayer position normally filled by monovalent and divalent cations such as Na+, K+, Mg2+ and Ca2+. As a consequence, chlorite interlayers are cemented by brucite and cannot swell nor shrink.

Brucite, in which some of the Mg2+ cations have been substituted by Al3+ cations, becomes positively charged and constitutes the main basis of layered double hydroxide (LDH). LDH minerals as hydrotalcite are powerful anion sorbents but are relatively rare in nature.

Brucite may also crystallise in cement and concrete in contact with seawater. Indeed, the Mg2+ cation is the second most abundant cation in seawater, just behind Na+ and before Ca2+. Because brucite is a swelling mineral, it causes a local volumetric expansion responsible for tensile stress in concrete. This leads to the formation of cracks and fissures in concrete, accelerating its degradation in seawater.

For the same reason, dolomite cannot be used as construction aggregate for making concrete. The reaction of magnesium carbonate with the free alkali hydroxides present in the cement porewater also leads to the formation of expansive brucite.

- MgCO3 + 2 NaOH → Mg(OH)2 + Na2CO3

This reaction, one of the two main alkali–aggregate reaction (AAR) is also known as alkali–carbonate reaction.

References

- ^ Pradyot Patnaik. Handbook of Inorganic Chemicals. McGraw-Hill, 2002, ISBN 0-07-049439-8

- ^ Toshiaki Enoki and Ikuji Tsujikawa (1975). "Magnetic Behaviours of a Random Magnet, NipMg(1-p)(OH2)". J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 39 (2): 317–323. doi:10.1143/JPSJ.39.317.

- ^ a b Zumdahl, Steven S. (2009). Chemical Principles 6th Ed. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. A22. ISBN 978-0-618-94690-7.

- ^ a b c d "Magnesium Hydroxide". American Elements. Retrieved May 9, 2019.

- ^ Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (76th ed.). CRC Press. 12 March 1996. ISBN 0849305969.

- ^ a b Margarete Seeger; Walter Otto; Wilhelm Flick; Friedrich Bickelhaupt; Otto S. Akkerman. "Magnesium Compounds". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a15_595.pub2. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Tedesco FJ, DiPiro JT (1985). "Laxative use in constipation". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 80 (4): 303–9. PMID 2984923.

- ^ https://www.glowm.com/resources/glowm/cd/pages/drugs/m001.html

- ^ Patent USX2952 - Magnesia, medicated, liquid - Google Patents

- ^ Michael Hordern, A World Elsewhere (1993), p. 2.

- ^ "Sir James Murray's condensed solution of fluid magnesia". The Sydney Morning Herald. Vol. 21, no. 2928. October 7, 1846. p. 1, column 4.

- ^ Ulster History. Sir James Murray – Inventor of Milk of Magnesia. 1788 to 1871 Archived 2011-06-05 at the Wayback Machine, 24 February 2005

- ^ When was Phillips' Milk of Magnesia introduced? FAQ, phillipsrelief.com, accessed 4 July 2016

- ^ results from the TARR web server: Milk of Magnesia

- ^ results from the TARR web server: Phillips' Milk of Magnesia

- ^ "Compound Summary for CID 14791 - Magnesium Hydroxide". PubChem.

- ^ Magnesium Hydroxide – Revolution Health

- ^ Washington, Neena (2 August 1991). Antacids and Anti Reflux Agents. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-8493-5444-7.

- ^ Milk of Magnesia Makes Good Antiperspirant

- ^ Canker sores, 2/1/2009

- ^ Aileen Gibson and Michael Maniocha White Paper: The Use Of Magnesium Hydroxide Slurry For Biological Treatment Of Municipal and Industrial Wastewater, August 12, 2004

- ^ Rothon, RN (2003). Particulate Filled Polymer Composites. Shrewsbury, UK: Rapra Technology. pp. 53–100.

- ^ Hollingbery, LA; Hull TR (2010). "The Thermal Decomposition of Huntite and Hydromagnesite - A Review". Thermochimica Acta. 509 (1–2): 1–11. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2010.06.012.

- ^ Hollingbery, LA; Hull TR (2010). "The Fire Retardant Behaviour of Huntite and Hydromagnesite - A Review". Polymer Degradation and Stability. 95 (12): 2213–2225. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2010.08.019.

- ^ Hollingbery, LA; Hull TR (2012). "The Fire Retardant Effects of Huntite in Natural Mixtures with Hydromagnesite". Polymer Degradation and Stability. 97 (4): 504–512. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2012.01.024.

- ^ Hollingbery, LA; Hull TR (2012). "The Thermal Decomposition of Natural Mixtures of Huntite and Hydromagnesite". Thermochimica Acta. 528: 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.tca.2011.11.002.

- ^ Hull, TR; Witkowski A; Hollingbery LA (2011). "Fire Retardant Action of Mineral Fillers". Polymer Degradation and Stability. 96 (8): 1462–1469. doi:10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2011.05.006.