American imperialism

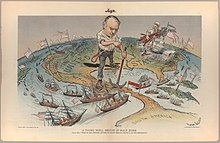

American imperialism is the economic, military and cultural influence of the United States on other countries. Such influence often goes hand in hand with expansion into foreign territories. The concept of an American Empire was first popularized during the presidency of James K. Polk who led the United States into the Mexican–American War of 1846, and the eventual annexation of California and other western territories via the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the Gadsden purchase.[1][2]

Imperialism

Thomas Jefferson, in the 1790s, awaited the fall of the Spanish Empire "until our population can be sufficiently advanced to gain it from them piece by piece."[3][4] In turn, historian Sidney Lens notes that "the urge for expansion – at the expense of other peoples – goes back to the beginnings of the United States itself."[1] Yale historian Paul Kennedy put it, "From the time the first settlers arrived in Virginia from England and started moving westward, this was an imperial nation, a conquering nation." [5]

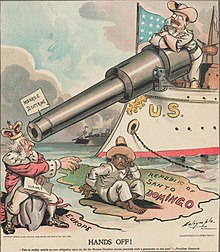

In the late 19th century, foreign territories such as Hawaii and Latin America were sought after by the United States. The Teller Amendment and the Platt Amendment were used in unison to grant the United States the right to intervene in those territories if that particular government was deemed unfit to rule itself. The American government now held the power to both criticize and occupy these nations if they were deemed to be unstable.

Stuart Creighton Miller says that the public's sense of innocence about Realpolitik impairs popular recognition of U.S. imperial conduct. The resistance to actively occupying foreign territory has led to policies of exerting influence via other means, including governing other countries via surrogates or puppet regimes, where domestically unpopular governments survive only through U.S. support.[6]

The maximum geographical extension of American direct political and military control happened in the aftermath of World War II, in the period after the surrender and occupations of Germany and Austria in May and later Japan and Korea in September 1945 and before the independence of the Philippines in July 1946.[7]

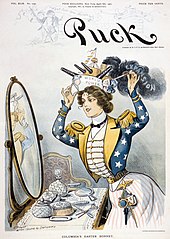

American exceptionalism

American exceptionalism is the theory that the United States occupies a special niche among the nations of the world[8] in terms of its national credo, historical evolution, and political and religious institutions and origins.

Philosopher Douglas Kellner traces the identification of American exceptionalism as a distinct phenomenon back to 19th century French observer Alexis de Tocqueville, who concluded by agreeing that the U.S., uniquely, was "proceeding along a path to which no limit can be perceived."[9]

American exceptionalism is popular among people within the U.S.,[10] but its validity and its consequences are disputed. Some American citizens will participate in exceptionalism without even being aware of it. Such instances occur when American interests and advancements are justified solely on the basis of its economic standing or the protection of human rights. The American public's attitude towards intervention in Cuba and the Philippines was one of sheer sympathy[citation needed]

As a Monthly Review editorial opines on the phenomenon, "in Britain, empire was justified as a benevolent 'white man's burden'. And in the United States, empire does not even exist; 'we' are merely protecting the causes of freedom, democracy and justice worldwide."[11]

Views of American imperialism

Journalist Ashley Smith divides theories of the U.S. imperialism into 5 broad categories: (1) "liberal" theories, (2) "social-democratic" theories, (3) "Leninist" theories, (4) theories of "super-imperialism", and (5) "Hardt-and-Negri-ite" theories.[12][page needed] There is also a conservative, anti-interventionist view as expressed by American journalist John T. Flynn:

The enemy aggressor is always pursuing a course of larceny, murder, rapine and barbarism. We are always moving forward with high mission, a destiny imposed by the Deity to regenerate our victims, while incidentally capturing their markets; to civilise savage and senile and paranoid peoples, while blundering accidentally into their oil wells.[13]

A "social-democratic" theory says that imperialistic U.S. policies are the products of the excessive influence of certain sectors of U.S. business and government—the arms industry in alliance with military and political bureaucracies and sometimes other industries such as oil and finance, a combination often referred to as the "military–industrial complex". The complex is said to benefit from war profiteering and the looting of natural resources, often at the expense of the public interest.[14] The proposed solution is typically unceasing popular vigilance in order to apply counter-pressure.[15] Johnson holds a version of this view.

Alfred T. Mahan, who served as an officer in the U.S. Navy during the late 19th century, supported the notion of American imperialism in his 1890 book titled The Influence of Sea Power upon History. In chapter one Mahan argued that modern industrial nations must secure foreign markets for the purpose of exchanging goods and, consequently, they must maintain a maritime force that is capable of protecting these trade routes.[16][page needed]

A theory of "super-imperialism" says that imperialistic U.S. policies are not driven simply by the interests of American businesses, but by the interests of the economic elites of a global alliance of developed countries. Capitalism in Europe, the U.S. and Japan has become too entangled, in this view, to permit military or geopolitical conflict between these countries, and the central conflict in modern imperialism is between the global core and the global periphery rather than between imperialist powers.

Empire

Following the invasion of Afghanistan in 2001, the idea of American imperialism was reexamined. On October 15, the cover of William Kristol's Weekly Standard carried the headline, "The Case for American Empire." Rich Lowry, editor in chief of the National Review, called for "a kind of low-grade colonialism" to topple dangerous regimes beyond Afghanistan.[17] The columnist Charles Krauthammer declared that, given complete U.S. domination "culturally, economically, technologically and militarily," people were "now coming out of the closet on the word 'empire.'"[5] The New York Times Sunday magazine cover for January 5, 2003, read "American Empire: Get Used To It." The phrase “American empire” appeared more than 1000 times in news stories during November 2002 – April 2003.[18]

In the book "Empire", Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri argued that "the decline of Empire has begun".[19] Hardt says the Iraq War is a classically imperialist war, and is the last gasp of a doomed strategy.[20] This new era still has colonizing power, but it has moved from national military forces based on an economy of physical goods to networked biopower based on an informational and affective economy. The U.S. is central to the development and constitution of a new global regime of international power and sovereignty, termed Empire, but is decentralized and global, and not ruled by one sovereign state; "the United States does indeed occupy a privileged position in Empire, but this privilege derives not from its similarities to the old European imperialist powers, but from its differences."[21] Hardt and Negri draw on the theories of Spinoza, Foucault, Deleuze and Italian autonomist marxists.[22][23]

Geographer David Harvey says there has emerged a new type of imperialism due to geographical distinctions as well as uneven levels of development.[24] He says there has emerged three new global economic and politics blocs: the United States, the European Union and Asia centered on China and Russia.[25][verification needed] He says there are tensions between the three major blocs over resources and economic power, citing the 2003 invasion of Iraq, whose goal was to prevent rivals from controlling oil.[26] Furthermore, Harvey argues there can arise conflict within the major blocs between capitalists and politicians due to their opposing economic interests.[27] Politicians, on the other hand, live in geographically fixed locations and are, in the U.S. and Europe, accountable to the electorate. The 'new' imperialism, then, has led to an alignment of the interests of capitalists and politicians in order to prevent the rise and expansion of possible economic and political rivals from challenging America's dominance.[28]

Classics professor and war historian Victor Davis Hanson dismisses the notion of an American empire altogether, mockingly comparing it to other empires: "We do not send out proconsuls to reside over client states, which in turn impose taxes on coerced subjects to pay for the legions. Instead, American bases are predicated on contractual obligations — costly to us and profitable to their hosts. We do not see any profits in Korea, but instead accept the risk of losing almost 40,000 of our youth to ensure that Kias can flood our shores and that shaggy students can protest outside our embassy in Seoul."[29]

Factors unique to the "Age of imperialism"

A variety of factors may have coincided during the "Age of Imperialism" in the late 19th century, when the United States and the other major powers rapidly expanded their territorial possessions. Some of these are explained, or used as examples for the various perceived forms of American imperialism.

- The prevalence of racism, notably John Fiske's conception of Anglo-Saxon racial superiority, and Josiah Strong's call to "civilize and Christianize"—all manifestations of a growing Social Darwinism and racism in some schools of American political thought.[30]

- Early in his career, as Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt was instrumental in preparing the Navy for the Spanish–American War[31] and was an enthusiastic proponent of testing the U.S. military in battle, at one point stating "I should welcome almost any war, for I think this country needs one".[32][33][34]

Industry and trade are two of the most prevalent factors unique to imperialism. American intervention in both Latin America and Hawaii resulted in multiple industrial investments, including the popular industry of Dole bananas. If the United States was able to annex a territory, in turn they were granted access to the trade and capital of those territories. In 1898, Senator Albert Beveridge proclaimed that an expansion of markets was absolutely necessary, "American factories are making more than the American people can use; American soil is producing more than they can consume. Fate has written our policy for us; the trade of the world must and shall be ours."[35]

U.S. foreign policy debate

This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards. (January 2014) |

Annexation is a crucial instrument in the expansion of a nation, due to the fact that once a territory is annexed it must act within the confines of its superior counterpart. The United States Congress' ability to annex a foreign territory is explained in a report from the Congressional Committee on Foreign Relations, "If, in the judgment of Congress, such a measure is supported by a safe and wise policy, or is based upon a natural duty that we owe to the people of Hawaii, or is necessary for our national development and security, that is enough to justify annexation, with the consent of the recognized government of the country to be annexed."[36]

Prior to annexing a territory, the American government still held immense power through the various legislations passed in the late 1800s. The Platt Amendment was utilized to prevent Cuba from entering into any agreements with foreign nations, and also granted the Americans the right to build naval stations on their soil.[37] Executive officials in the American government began to determine themselves the supreme authority in matters regarding the recognition or restriction of independence.[37]

When asked on April 28, 2003, on al-Jazeera whether the United States was "empire building," Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld replied "We don't seek empires, we're not imperialistic. We never have been."[38]

However, historian Donald W. Meinig says the imperial behavior by the United States dates at least to the Louisiana Purchase, which he describes as an "imperial acquisition—imperial in the sense of the aggressive encroachment of one people upon the territory of another, resulting in the subjugation of that people to alien rule." The U.S. policies towards the Native Americans he said were "designed to remold them into a people more appropriately conformed to imperial desires."[39]

Writers and academics of the early 20th century, like Charles A. Beard, in support of non-interventionism (sometimes referred to as "isolationism"), discussed American policy as being driven by self-interested expansionism going back as far as the writing of the Constitution. Some politicians today do not agree. Pat Buchanan claims that the modern United States' drive to empire is "far removed from what the Founding Fathers had intended the young Republic to become."[40]

Andrew Bacevich argues that the U.S. did not fundamentally change its foreign policy after the Cold War, and remains focused on an effort to expand its control across the world.[41] As the surviving superpower at the end of the Cold War, the U.S. could focus its assets in new directions, the future being "up for grabs" according to former Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz in 1991.[42]

In Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media, the political activist Noam Chomsky argues that exceptionalism and the denials of imperialism are the result of a systematic strategy of propaganda, to "manufacture opinion" as the process has long been described in other countries.[43]

Thorton wrote that "[...]imperialism is more often the name of the emotion that reacts to a series of events than a definition of the events themselves. Where colonization finds analysts and analogies, imperialism must contend with crusaders for and against."[44] Political theorist Michael Walzer argues that the term hegemony is better than empire to describe the US's role in the world;[45] political scientist Robert Keohane agrees saying, a "balanced and nuanced analysis is not aided...by the use of the phrase 'empire' to describe United States hegemony, since 'empire' obscures rather than illuminates the differences in form of rule between the United States and other Great Powers, such as Great Britain in the 19th century or the Soviet Union in the twentieth.".[46]

Emmanuel Todd assumes that USA cannot hold for long the status of mondial hegemonic power due to limited resources. Instead, USA is going to become just one of the major regional powers along with European Union, China, Russia, etc. Other political scientists, such as Daniel Nexon and Thomas Wright, argue that neither term exclusively describes foreign relations of the United States. The U.S. can be, and has been, simultaneously an empire and a hegemonic power. They claim that the general trend in U.S. foreign relations has been away from imperial modes of control.[47]

Cultural imperialism

Some critics of imperialism argue that military and cultural imperialism are interdependent. American Edward Said, one of the founders of post-colonial theory, said that,

[...], so influential has been the discourse insisting on American specialness, altruism and opportunity, that imperialism in the United States as a word or ideology has turned up only rarely and recently in accounts of the United States culture, politics and history. But the connection between imperial politics and culture in North America, and in particular in the United States, is astonishingly direct.[48]

International relations scholar David Rothkopf disagrees and argues that cultural imperialism is the innocent result of globalization, which allows access to numerous U.S. and Western ideas and products that many non-U.S. and non-Western consumers across the world voluntarily choose to consume.[49] Matthew Fraser has a similar analysis, but argues further that the global cultural influence of the U.S. is a good thing.[50]

Nationalism is the main process through which the government is able to shape public opinion. Propaganda in the media is strategically placed in order to promote a common attitude among the people. Louis A. Perez Jr. provides an example of propaganda used during the war of 1898, "We are coming, Cuba, coming; we are bound to set you free! We are coming from the mountains, from the plains and inland sea! We are coming with the wrath of God to make the Spaniards flee! We are coming, Cuba, coming; coming now!"[37]

U.S. military bases

Chalmers Johnson argues that America's version of the colony is the military base.[51] Chip Pitts argues similarly that enduring U.S. bases in Iraq suggest a vision of "Iraq as a colony".[52]

While territories such as Guam, the United States Virgin Islands, the Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa and Puerto Rico remain under U.S. control, the U.S. allowed many of its overseas territories or occupations to gain independence after World War II. Examples include the Philippines (1946), the Panama canal zone (1979), Palau (1981), the Federated States of Micronesia (1986) and the Marshall Islands (1986). Most of them still have U.S. bases within their territories. In the case of Okinawa, which came under U.S. administration after the Battle of Okinawa during the Second World War, this happened despite local popular opinion.[53] As of 2003[update], the United States had bases in over 36 countries worldwide.[54]

Benevolent imperialism

One of the earliest historians of American Empire, William Appleman Williams, wrote, "The routine lust for land, markets or security became justifications for noble rhetoric about prosperity, liberty and security."[55]

Max Boot defends U.S. imperialism by claiming: "U.S. imperialism has been the greatest force for good in the world during the past century. It has defeated communism and Nazism and has intervened against the Taliban and Serbian ethnic cleansing.[56]" Boot used "imperialism" to describe United States policy, not only in the early 20th century but "since at least 1803".[57][58] This embrace of empire is made by others neoconservatives, including British historian Paul Johnson, and writers Dinesh D'Souza and Mark Steyn. It is also made by some liberal hawks, such as political scientist Zbigniew Brzezinski and Michael Ignatieff.[59]

British historian Niall Ferguson argues that the United States is an empire and believes that this is a good thing. Ferguson has drawn parallels between the British Empire and the imperial role of the United States in the late 20th and early 21st centuries, though he describes the United States' political and social structures as more like those of the Roman Empire than of the British. Ferguson argues that all of these empires have had both positive and negative aspects, but that the positive aspects of the U.S. empire will, if it learns from history and its mistakes, greatly outweigh its negative aspects.[60][page needed]

Another point of view implies that United States expansion overseas has indeed been imperialistic, but that this imperialism is only a temporary phenomenon; a corruption of American ideals or the relic of a past historical era. Historian Samuel Flagg Bemis argues that Spanish–American War expansionism was a short-lived imperialistic impulse and "a great aberration in American history", a very different form of territorial growth than that of earlier American history.[61] Historian Walter LaFeber sees the Spanish–American War expansionism not as an aberration, but as a culmination of United States expansion westward.[62]

Historian Victor Davis Hanson argues that the U.S. does not pursue world domination, but maintains worldwide influence by a system of mutually beneficial exchanges.[63] On the other hand, a Filipino revolutionary General Emilio Aguinaldo felt as though the American involvement in the Philippines was destructive, "...the Filipinos fighting for Liberty, the American people fighting them to give them liberty. The two peoples are fighting on parallel lines for the same object."[64] American influence worldwide and the effects it has on other nations have multiple interpretations according to whose perspective is being taken into account.

Liberal internationalists argue that even though the present world order is dominated by the United States, the form taken by that dominance is not imperial. International relations scholar John Ikenberry argues that international institutions have taken the place of empire.[65]

International relations scholar Joseph Nye argues that U.S. power is more and more based on "soft power", which comes from cultural hegemony rather than raw military or economic force.[66] This includes such factors as the widespread desire to emigrate to the United States, the prestige and corresponding high proportion of foreign students at U.S. universities, and the spread of U.S. styles of popular music and cinema. Mass immigration into America may justify this theory, but it is hard to know for sure whether the United States would still maintain its prestige without its military and economic superiority.

World War I

American imperialism did not end with the First World War. When the First World War broke out in Europe, President Woodrow Wilson promised American neutrality throughout the war. This promise was broken when the United States entered the war after the Zimmermann Telegram. The war for the United States was "a war for empire" according to the historian W. E. B. Du Bois, as historian Howard Zinn explains in his book, A Peoples Republic .[67] Zinn argues that the United States entered the war in order to create an international market that could be beneficial to the United States through conquest.[68]

During the First World War, some of the American Imperialism at the time can be viewed as imperialism to stop the spread of democracy to certain countries, such as Haiti. According to the noted writer and progressive Randolph Bourne, the United States did not enter the war with intentions to make the world a better place or else they would have required a principle of international order. Bourne criticizes intellectuals who gave support for the war without knowing the true intentions of the United States government. Even though Bourne believes that the United States entered the war imperialistically, he states that many intellectuals believed at the time that the United States intervened in the war to promote democracy. Bourne believes that by leading the public into the war, with many intellectuals unsure of the actual reasons for the war, the country led an apathetic nation into what he considers an irresponsible war.[69]

The United States invaded Haiti in July 1915 after having made landfall eight times previously. American rule in Haiti continued through 1942, but was initiated during World War I. The historian Mary Renda in her book, Taking Haiti, talks about the American invasion of Haiti to bring about political stability through U.S. control. The American government did not believe Haiti was ready for self-governing or democracy, according to Renda. In order to bring about political stability in Haiti, without allowing for self-governance, the United States secured control and integrated the country into the international capitalist economy, while preventing Haiti from securing their own democracy. In order to convince the American public of the uncivilized nature of Haiti, the United States government used paternalism to make it seem to the American government that the Haitian political process was uncivilized. While Haiti had been running their own government for many years before American intervention, the United States felt as though Haiti was unfit for self-rule, even though it may not have been true at all. Americans saw the Haitians as children in need of guidance due to the corrupt thoughts of the U.S. officials who rationalized American imperialism in Haiti. Through their imperialistic control, the United States made the Haitian government agree to terms laid out by the U.S. government as well as directly supervising the Haitian economy. This direct supervision of the Haitian economy stressed the uncivilized nature of the Haitian political process by the American government to the U.S. citizens and prevented the spread of democracy to Haiti where they were unable to form their own government under U.S. imperialistic control.[70]

In February, Russia went through the first revolution of 1917, which removed Tsar Nicholas II from power. The United States, including President Wilson, praised this revolution and felt that it was a step towards post-war world order. Not long after in October 1917, the Bolsheviks overthrew the new Russian 'unity' government in the second revolution. The United States government was stunned with the second revolution and was against the Bolshevik proposed armistice with the Central Powers. In order to keep the Bolsheviks from gaining allied supplies in Russia, Wilson agreed to an intervention in Russia. The United States and the allies entered into a war with the Soviets, with the first U.S. troops landing in Russia in September 1918. After the defeat of the Germans, the war in Russia continued, with the United States and the allies opposing the Bolsheviks. This intervention in Russia was imperialistic by its nature opposing the Soviet government in favor of a government that would align with the allied and American views. In their attempt to overthrow the Bolshevik government, the United States showed an imperialistic attitude towards a nation that was still aligned with the allies officially.[71]

See also

Notes and references

- ^ a b Lens, Sidney; Zinn, Howard (2003) [1971]. The Forging of the American Empire. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 0-7453-2100-3.

- ^ Field, James A., Jr. (June 1978). "American Imperialism: The Worst Chapter in Almost Any Book". The American Historical Review. 83 (3): 644–668. doi:10.2307/1861842. JSTOR 1861842.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Susan Welch; John Gruhl; Susan M. Rigdon; Sue Thomas (2011). Understanding American Government. Cengage Learning. pp. 583, 671 (note 3). ISBN 978-0-495-91050-3.

- ^ Walter LaFeber (1993). Inevitable Revolutions: The United States in Central America. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-393-30964-5.

- ^ a b Emily Eakin "Ideas and Trends: All Roads Lead To DC" New York Times , March 31, 2002.

- ^ Johnson, Chalmers, Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire (2000), pp.72–9

- ^ "Philippine Republic Day". www.gov.ph.

- ^ Frederick Jackson Turner, Archived 2008-05-21 at the Wayback Machine, sagehistory.net (archived from the original on May 21, 2008).

- ^ Kellner, Douglas (April 25, 2003). "American Exceptionalism". Archived from the original on February 17, 2006. Retrieved February 20, 2006.

- ^ Edwords, Frederick (November–December 1987). "The religious character of American patriotism. It's time to recognize our traditions and answer some hard questions". The Humanist (p. 20-24, 36).

- ^ Magdoff, Harry; John Bellamy Foster (November 2001). "After the Attack...The War on Terrorism". Monthly Review. 53 (6): 7. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Smith, Ashley (June 24, 2006). The Classical Marxist Theory of Imperialism. Socialism 2006. Columbia University.

- ^ "Books" (PDF). Mises Institute.

- ^ C. Wright Mills, The Causes of World War Three, Simon and Schuster, 1958, pp. 52, 111

- ^ Flynn, John T. (1944) As We Go Marching.

- ^ Alfred Thayer Mahan (1987). The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660–1783. Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-25509-5.

- ^ Nina J. Easton, "Thunder on the Right," American Journalism Review 23 (December 2001), 320.

- ^ David A. Lake, “Escape from the State-of-Nature: Authority and Hierarchy in World Politics,” International Security, 32/1: (2007), p 48.

- ^ Empire hits back. The Observer, July 15, 2001.

- ^ Hardt, Michael (July 13, 2006). "From Imperialism to Empire". The Nation.

- ^ Negri, Antonio; Hardt, Michael (2000). Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00671-2. Retrieved October 8, 2009. p. xiii–xiv.

- ^ Michael Hardt, Gilles Deleuze: an Apprenticeship in Philosophy, ISBN 0-8166-2161-6

- ^ Autonomism#Italian autonomism

- ^ Harvey, David (2005). The new imperialism. Oxford University Press. p. 101. ISBN 978-0-19-927808-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - ^ Harvey 2005, p. 31.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Harvey 2005, p. 187.

- ^ Harvey 2005, pp. 76–78

- ^ VDH's Private Papers::A Funny Sort of Empire

- ^ Thomas Friedman, "The Lexus and the Olive Tree", p. 381, and Manfred Steger, "Globalism: The New Market Ideology," and Jeff Faux, "Flat Note from the Pied Piper of Globalization," Dissent, Fall 2005, pp. 64–67.

- ^ Brands, Henry William. (1997). T.R.: The Last Romantic. New York: Basic Books. Reprinted 2001, full biography OCLC 36954615, ch 12

- ^ "April 16, 1897: T. Roosevelt Appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy". Crucible of Empire—Timeline. PBS Online. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ "Transcript For "Crucible Of Empire"". Crucible of Empire—Timeline. PBS Online. Retrieved July 26, 2007.

- ^ Tilchin, William N. Theodore Roosevelt and the British Empire: A Study in Presidential Statecraft (1997)

- ^ Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States: 1492–2001. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. Print.

- ^ United States. Cong. Senate. Committee on Foreign Relations. Annexation of Hawaii. Comp. Davis. 55th Cong., 2nd sess. S. Rept. 681. Washington, D.C.: G.P.O., 1898. Print.

- ^ a b c Pérez, Louis A. The War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1998. Print.

- ^ "USATODAY.com – American imperialism? No need to run away from label". usatoday.com.

- ^ Meinig, Donald W. (1993). The Shaping of America: A Geographical Perspective on 500 Years of History, Volume 2: Continental America, 1800–1867. Yale University Press. pp. 22–23, 170–196, 516–517. ISBN 0-300-05658-3.

- ^ Buchanan, Pat (1999). A Republic, Not an Empire: Reclaiming America's Destiny. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0-89526-272-X. p. 165.

- ^ Bacevich, Andrew (2004). American Empire: The Realities and Consequences of U.S. Diplomacy. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-01375-1.

- ^ ERIC SCHMITT, "Washington at Work; Ex-Cold Warrior Sees the Future as 'Up for Grabs'" The New York Times December 23, 1991.

- ^ Edward Hallett Carr, The Twenty Years' Crisis 1919–1939: An Introduction to the Study of International Relations, 1939.

- ^ Thornton, Archibald Paton (September 1978). Imperialism in the Twentieth Century. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-24848-1.

- ^ Walzer, Michael. "Is There an American Empire?". www.freeindiamedia.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2006. Retrieved June 10, 2006.

- ^ Keohane, Robert O. "The United States and the Postwar Order: Empire or Hegemony?" (Review of Geir Lundestad, The American Empire) Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 28, No. 4 (November , 1991), p. 435

- ^ Nexon, Daniel and Wright, Thomas "What's at Stake in the American Empire Debate" American Political Science Review, Vol. 101, No. 2 (May 2007), p. 266-267

- ^ Said, Edward. Culture and Imperialism, speech at York University, Toronto, February 10, 1993. (archived from the original on October 13, 2007)./ Archived] 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Rothkopf, David In Praise of Cultural Imperialism? Foreign Policy, Number 107, Summer 1997, pp. 38–53

- ^ Fraser, Matthew (2005). Weapons of Mass Distraction: Soft Power and American Empire. St. Martin's Press.

- ^ America's Empire of Bases

- ^ Pitts, Chip (November 8, 2006). "The Election on Empire". The National Interest. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Patrick Smith, Pay Attention to Okinawans and Close the U.S. Bases, International Herald Tribune (Opinion section), March 6, 1998.

- ^ "Base Structure Report" (PDF). USA Department of Defense. 2003. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 10, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2007.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ William Appleman Williams, "Empire as a Way of Life: An Essay on the Causes and Character of America's Present Predicament Along with a Few Thoughts About an Alternative" (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), S1.

- ^ Max Boot. "American Imperialism? No Need to Run Away from Label". Op-Ed. Council on Foreign Relations.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ American Imperialism? No Need to Run Away From the Label USA Today May 6, 2003

- ^ "Max Boot, "Neither New nor Nefarious: The Liberal Empire Strikes Back," November 2003". mtholyoke.edu.

- ^ Heer, Jeet (March 23, 2003). "Operation Anglosphere". Boston Globe. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Ferguson, Niall (June 2, 2005). Colossus: The Rise and Fall of the American Empire. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-101700-7.

- ^ Miller, Stuart Creighton (1982). "Benevolent Assimilation" The American Conquest of the Philippines, 1899–1903. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-02697-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) p. 3. - ^ Lafeber, Walter (1975). The New Empire: An Interpretation of American Expansion, 1860–1898. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9048-0.

- ^ Hanson, Victor Davis (November 2002). "A Funny Sort of Empire". National Review. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Aguinaldo, Emilio (September 1899). "Aguinaldo's Case Against the United States" (PDF). North American Review.

- ^ Ikenberry, G. John (March–April 2004). "Illusions of Empire: Defining the New American Order". Foreign Affairs.

- ^ Cf. Nye, Joseph Jr. (2005). Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. Public Affairs. 208 pp.

- ^ Zinn, Howard. A People's History of the United States. New York: HarperCollins, 2003. p. 363

- ^ Zinn, pp. 359–376

- ^ Bourne, "The War and the Intellectuals," The Seven Arts, pp. 133–146

- ^ Renda, "Introduction," in Taking Haiti: Military Occupation & the Culture of U.S. Imperialism, 1915–1940, pp. 10–22, 29–34

- ^ Powaski, "The United States and the Bolshevik Revolution, 1917–1933," in The Cold War:. The United States and the Soviet Union, 1917–1991, pp. 5–34

Further reading

- Bacevich, Andrew (2008). The Limits of Power: The End of American Exceptionalism. Macmillan. ISBN 0-8050-8815-6.

- Boot, Max (2002). The Savage Wars of Peace: Small Wars and the Rise of American Power. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-00721-X.

- Brown, Seyom (1994). Faces of Power: Constancy and Change in United States Foreign Policy from Truman to Clinton. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-09669-0.

- Burton, David H. (1968). Theodore Roosevelt: Confident Imperialist. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ASIN B0007GMSSY.

- Callahan, Patrick (2003). Logics of American Foreign Policy: Theories of America's World Role. New York: Longman. ISBN 0-321-08848-4.

- Card, Orson Scott (2006). Empire. TOR. ISBN 0-7653-1611-0.

- Daalder, Ivo H.; James M. Lindsay (2003). America Unbound: The Bush Revolution in Foreign Policy. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution. ISBN 0-8157-1688-5.

- Fulbright, J. William; Seth P. Tillman (1989). The Price of Empire. Pantheon Books. ISBN 0-394-57224-6.

- Gaddis, John Lewis (2005). Strategies of Containment: A Critical Appraisal of Postwar American National Security Policy (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517447-X.

- Hardt, Michael; Antonio Negri (2001). Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-00671-2. online

- Huntington, Samuel P. (1996). The Clash of Civilizations. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81164-2.

- Johnson, Chalmers (2000). Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire. New York: Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6239-4.

- Johnson, Chalmers (2004). The Sorrows of Empire: Militarism, Secrecy, and the End of the Republic. New York: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-7004-4.

- Johnson, Chalmers (2007). Nemesis: The Last Days of the American Republic. New York, NY: Metropolitan Books. ISBN 0-8050-7911-4.

- Kagan, Robert (2003). Of Paradise and Power: America and Europe in the New World Order. New York: Knopf. ISBN 1-4000-4093-0.

- Kerry, Richard J. (1990). The Star-Spangled Mirror: America's Image of Itself and the World. Savage, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-8476-7649-8.

- Lundestad, Geir (1998). Empire by Integration: The United States and European Integration, 1945–1997. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-878212-8.

- Meyer, William H. (2003). Security, Economics, and Morality in American Foreign Policy: Contemporary Issues in Historical Context. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-086390-4.

- Nye, Joseph S., Jr (2002). The Paradox of American Power: Why the World's Only Superpower Can't Go It Alone. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515088-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Odom, William; Robert Dujarric (2004). America's Inadvertent Empire. Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10069-8.

- Patrick, Stewart; Shepard Forman, eds. (2001). Multilateralism and U.S. Foreign Policy: Ambivalent Engagement. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-58826-042-9.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - Perkins, John (2004). Confessions of an Economic Hit Man. Tihrān: Nashr-i Akhtarān. ISBN 1-57675-301-8.

- Rapkin, David P., ed. (1990). World Leadership and Hegemony. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner. ISBN 1-55587-189-5.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ruggie, John G., ed. (1993). Multilateralism Matters: The Theory and Praxis of an Institutional Form. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-07980-8.

{{cite book}}:|first=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Smith, Tony (1994). America's Mission: The United States and the Worldwide Struggle for Democracy in the Twentieth Century. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03784-1.

- Tomlinson, John (1991). Cultural Imperialism: A Critical Introduction. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-4250-6.

- Todd, Emmanuel (2004). After the Empire: The Breakdown of the American Order. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13103-2.

- Tremblay, Rodrigue (2004). The New American Empire. Haverford, PA: Infinity Pub. ISBN 0-7414-1887-8.

- Zepezauer, Mark (2002). Boomerang!: How Our Covert Wars Have Created Enemies Across the Middle East and Brought Terror to America. Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press. ISBN 1-56751-222-4.

External links

- "Imperial America" by Richard Hass, 2000

- "Empire or Not? A Quiet Debate Over U.S. Role" by Thomas E. Ricks, 2001

- "The Answer to Terrorism? Colonialism" by Paul Johnson, 2001

- "The Need for a New Imperialism" by Martin Wolf, 2001

- "The Case for American Empire" by Max Boot, 2001

- "All Roads Lead to D.C." by Emily Eakin, 2002

- "The Reluctant Imperialist: Terrorism, Failed States, and the Case for American Empire" by Sebastian Mallaby, 2002

- "The New Liberal Imperialism" by Robert Cooper, 2002

- "In Praise of American Empire" by Dinesh D'Souza, 2002

- "Empire lite" by Michael Ignatieff, 2003

- "America and The Tragic Limits of Imperialism" by Robert D. Kaplan, 2003

- "An Empire in Denial: The Limits of US Imperialism" by Niall Ferguson, 2003

- "In Defence of Empires" by Deepak Lal, 2003