Asterix

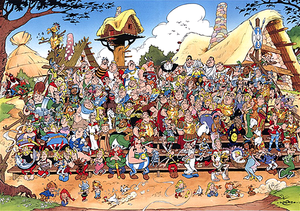

Some of the many characters in Asterix. In the front row are the regular characters, with Asterix himself in the centre. | |

| Author | René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | Albert Uderzo |

| Country | France |

| Language | French (translated into more than 100 different languages and dialects) |

| Genre | Humor and satire |

| Publisher | Dargaud (France) |

| Published | 29 October 1959 – 22 October 2010 (original period) |

| No. of books | 34 (List of books) |

Asterix or The Adventures of Asterix ([Astérix or Astérix le Gaulois] Error: {{Lang-xx}}: text has italic markup (help), IPA: [asteʁiks lə ɡolwa]) is a series of French comic books written by René Goscinny and illustrated by Albert Uderzo (Uderzo also took over the job of writing the series after the death of Goscinny in 1977). The series first appeared in French in the magazine Pilote on 29 October 1959. As of 2009, 34 comic books in the series have been released.

The series follows the exploits of a village of indomitable Gauls as they resist Roman occupation. They do so by means of a magic potion, brewed by their druid, which gives the recipient superhuman strength. The protagonist, the titular character Asterix, along with his friend Obelix have various adventures. The "ix" suffix of both names echoes the names of real Gaulish chieftains such as Vercingetorix, Orgetorix, and Dumnorix. Many of the stories have them travel to foreign countries, though others are set in and around their village. For much of the history of the series (Volumes 4 through 29), settings in Gaul and abroad alternated, with even-numbered volumes set abroad and odd-numbered volumes set in Gaul, mostly in the village.

The Asterix series is one of the most popular Franco-Belgian comics in the world, with the series being translated into over 100 languages, and it is popular in most European countries. Asterix is less well known in the United States and Japan.

The success of the series has led to the adaptation of several books into 14 films: ten animated, and four with live actors. There have also been a number of games based on the characters, and a theme park near Paris, Parc Astérix, is themed around the series. To date, 325 million copies of 34 Asterix books have been sold worldwide, making co-creators René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo France's bestselling authors abroad.[1][2]

History

Prior to creating the Asterix series, Goscinny and Uderzo had previously had success with their series Oumpah-pah, which was published in the Tintin magazine.[3]

Astérix was originally serialised in the magazine Pilote, in the very first issue published on 29 October 1959.[4] In 1961 the first book was put together entitled Asterix the Gaul. From then on, books were released generally on a yearly basis.

Uderzo's first sketches portrayed Asterix as a huge and strong traditional Gaulish warrior. But Goscinny had a different picture in his mind. He visualized Asterix as a shrewd small sized warrior who would prefer intelligence over strength. However, Uderzo felt that the small sized hero needed a strong but dim companion to which Goscinny agreed. Hence, Obelix was born.[5] Despite the growing popularity of Asterix with the readers, the financial backing for Pilote ceased. Pilote was taken over by Georges Dargaud.[5]

When Goscinny died in 1977, Uderzo continued the series alone on the demand of the readers who implored him to continue. He continued the series but on a less frequent basis. Most critics and fans of the series prefer Goscinny's albums.[6] Uderzo created his own publishing company, Les Editions Albert-René, which published every album drawn and written by Uderzo alone since then.[5] However, Dargaud, the initial publisher of the series, kept the publishing rights on the 24 first albums made by both Uderzo and Goscinny. In 1990, the Uderzo and Goscinny families decided to sue Dargaud to take over the rights. In 1998, after a long trial, Dargaud lost the rights to publish and sell the albums. Uderzo decided to sell these rights to Hachette instead of Albert-René, but the publishing rights on new albums were still owned by Albert Uderzo (40%), Sylvie Uderzo (20%) and Anne Goscinny (40%).

Although Uderzo declared he did not want anyone to continue the series after his death, which is similar to the request Hergé made regarding his The Adventures of Tintin, his attitude changed and in December 2008 he sold his stake to Hachette, which took over the company and now own the rights. This has provoked a family row.[7]

In a letter published in the French newspaper Le Monde in 2009, Uderzo's daughter, Sylvie, attacked her father's decision to sell the family publishing firm and the rights to produce new Astérix adventures after his death. She is reported as saying "...the co-creator of Astérix, France’s comic strip hero, has betrayed the Gaulish warrior to the modern-day Romans – the men of industry and finance”.[8][9] René Goscinny's daughter Anne also gave her agreement to the continuation of the series and sold her rights at the same time. She is reported to have said that "Asterix has already had two lives: one during my father's lifetime and one after it. Why not a third?".[10] A few months later, Uderzo appointed three illustrators, who had been his assistants for many years, to continue the series.[6] In 2011, Uderzo announced that a new Asterix album was due out in 2013, with Jean-Yves Ferri writing the story and Frédéric Mébarki drawing it.[11] A year later, in 2012, the publisher Albert-René announced that Frédéric Mébarki had renounced to drawing the new album, due to the pressure he felt in following in the steps of Uderzo. Comic artist Didier Conrad was officially announced to take over drawing duties from Mébarki, with the due date of the new album in 2013 unchanged.[12][13]

List of titles

Numbers 1 - 24, 32 and 34 are by both Goscinny and Uderzo. Numbers 25 - 31 and 33 are solely the work of Uderzo. Years stated are for their initial release.

Asterix Conquers Rome is a comic book adaptation of the animated film The Twelve Tasks of Asterix. It was released in 1976, making it technically the 23rd Asterix volume to be published. But it has been rarely reprinted and is not considered to be canonical to the series. The only English translation ever to be published were in the Asterix Annual 1980 and as a standalone volume in 1984.

In 2007, Les Editions Albert René released a tribute volume titled Astérix et ses Amis, a 60 pages comic book made up of various short stories (from one to four pages). It was a tribute to Albert Uderzo on the occasion of his 80th birthday by 34 renowned European comics artists. The volume was translated into nine languages, but has not yet been translated into English.[16]

Synopsis and characters

The main setting for the series is an unnamed coastal village in Armorica (present-day Brittany), a province of Gaul (modern France), in the year 50 BC. Julius Caesar has conquered nearly all of Gaul for the Roman Empire. The little Armorican village, however, has held out because the villagers can gain temporary superhuman strength by drinking a magic potion brewed by the local village druid, Getafix.

The main protagonist and hero of the village is Asterix, who, because of his shrewdness, is usually entrusted with the most important affairs of the village. He is aided in his adventures by his rather fat and unintelligent friend, Obelix, who, because he fell into the druid's cauldron of the potion as a baby, has permanent superhuman strength. Obelix is usually accompanied by Dogmatix, his little dog. (Except for Asterix and Obelix, the names of the characters change with the language. For example, Obelix's dog's name is "Dogmatix" in English, but "Idéfix" in the original French edition.)

Asterix and Obelix (and sometimes other members of the village) go on various adventures both within the village and in far away lands. Places visited in the series include parts of Gaul (Lutetia, Corsica etc.), neighbouring nations (Belgium, Spain, Britain, Germany etc.), and far away lands (North America, Middle East, India etc.).

The series employs science-fiction and fantasy elements in the more recent books; for instance, the use of extraterrestrials in Asterix and the Falling Sky and the city of Atlantis in Asterix and Obelix All at Sea.

Humour

The humour encountered in the Asterix comics is often centering on puns, caricatures, and tongue-in-cheek stereotypes of contemporary European nations and French regions. Much of the humour in the initial Asterix books was French-specific, which delayed the translation of the books into other languages for fear of losing the jokes and the spirit of the story. Some translations have actually added local humour: In the Italian translation, the Roman legionnaires are made to speak in 20th century Roman dialect and Obelix's famous "Ils sont fous ces romains" ("These Romans are crazy") is translated as "Sono pazzi questi romani", alluding to the Roman abbreviation SPQR. In another example: Hiccups are written onomatopoeically in French as "hips," but in English as "hic," allowing Roman legionnaries in at least one of the English translations to decline their hiccups in Latin ("hic, haec, hoc"). The newer albums share a more universal humour, both written and visual.[17]

In spite of (or perhaps because of) this stereotyping, and notwithstanding some alleged streaks of French chauvinism, the humour has been very well received by European and Francophone cultures around the world.

Translations

The 34 books or albums (one of which is a compendium of short stories) in the series have been translated into more than 100 languages and dialects. Besides the original French, most albums are available in Estonian, English, Czech, Dutch, German, Galician, Danish, Icelandic, Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, Spanish, Catalan, Basque, Portuguese (and Brazilian Portuguese), Italian, modern Greek, Hungarian, Polish, Romanian, Turkish, Slovene, Bulgarian, Serbian, Croatian, Latvian, and Welsh,[18] as well as Latin.[19]

Some albums have also been translated into languages as diverse as Esperanto, Scots Gaelic, Indonesian, Persian, Mandarin, Korean, Japanese, Bengali, Afrikaans, Arabic, Hindi, Hebrew, Frisian, Romansch, Vietnamese, and Sinhala (Sinhalese) and Ancient Greek.[18]

In France, Finland, and especially in Germany, several volumes were translated into a variety of regional languages and dialects, such as Alsatian, Breton, Chtimi (Picard) and Corsican in France, Bavarian, Swabian and Low German in Germany, and Savo, Karelia, Rauma and Helsinki slang dialects in Finland. Also, in Portugal, a special edition of the first volume, Asterix the Gaul, was translated into local language Mirandese.[20] In Greece, a number of volumes have appeared in the Cretan Greek, Cypriot Greek and Pontic Greek dialects.[21] In the Italian version, while the Gauls speak standard Italian, the legionaries speak in the Romanesque dialect. In former Yugoslavia, "Forum" publishing house translated Corsican in "Asterix in Corsica" into Montenegrin dialect of Serbo-Croatian (today called Montenegrin language).

In the Netherlands several volumes were translated into Frisian, a language related to Old English spoken in the province of Friesland. Also in the Netherlands two volumes were translated into Limburgish, a regional language spoken not only in Dutch Limburg but also in Belgian Limburg and North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Hungarian-language books have been issued in Yugoslavia for the Hungarian minority living in Serbia. Although not a fully autonomic dialect, it slightly differs from the language of the books issued in Hungary. In Sri Lanka, the cartoon series was adapted into Sinhala (Singhalese) as Sura Pappa, the only Sri Lankan translation of a foreign cartoon that managed to keep the spirit of the original series intact.[20]

Most volumes have been translated into Latin and Ancient Greek with accompanying teachers' guides as a way of teaching these ancient languages.

English translation

The translation of the books into English has been done by Derek Hockridge and Anthea Bell, and their English language rendition has been widely praised for maintaining the spirit and humour of the original French version.

Adaptations

The series has been adapted into various media.

Films

Various motion pictures based upon the series have been made.

- Two Romans in Gaul, 1967, live-action, in which Asterix and Obelix appear in a cameo.

- Asterix the Gaul, 1967, animated, based on the book Asterix the Gaul.

- Asterix and the Golden Sickle, 1967, animated, based upon the comic book Asterix and the Golden Sickle, incomplete and never released.

- Asterix and Cleopatra, 1968, animated, based on the book Asterix and Cleopatra.

- The Dogmatix Movie, 1973, animated, a unique story based on Dogmatix and his animal friends, Albert Uderzo created a comic version of the never release movie in 2003.

- The Twelve Tasks of Asterix, 1976, animated, a unique story not based on an existing comic.

- Asterix Versus Caesar, 1985, animated, based on both Asterix the Legionary and Asterix the Gladiator.

- Asterix in Britain, 1986, animated, based upon the book Asterix in Britain.

- Asterix and the Big Fight, 1989, animated, based on both Asterix and the Big Fight and Asterix and the Soothsayer.

- Asterix Conquers America, 1994, animated, loosely based upon the comic Asterix and the Great Crossing.

- Asterix and Obelix take on Caesar, 1999, live-action, based primarily upon Asterix the Gaul, Asterix and the Soothsayer, Asterix and the Goths, Asterix the Legionary, and Asterix the Gladiator.

- Asterix and Obelix: Mission Cleopatra, 2002, live-action, based upon the comic book Asterix and Cleopatra.

- Asterix and Obelix in Spain, 2004, live-action, based upon the comic book Asterix in Spain, incomplete and never released because Asterix and the Vikings was in production as the first Asterix cartoon since Asterix conquers America.

- Asterix and the Vikings, 2006, animated, loosely based upon the comic book Asterix and the Normans.

- Asterix at the Olympic Games, 2008, live-action, loosely based upon the comic book Asterix at the Olympic Games.[18][22][23]

- Asterix & Obelix: On Her Majesty's Service, 2012, live-action, based upon the book Asterix in Britain and will be first Asterix movie in stereoscopy 3D

- Asterix: The Land of Gods, 2014 (latest), animated, loosely based upon the comic book The Mansions of the Gods and will be the first animated Asterix movie in stereoscopy 3D.

Games

Many gamebooks, boardgames and video games are based upon the Asterix series. In particular, many video games were released by various computer game publishers.

Theme park

Parc Asterix, a theme park 22 miles north of Paris, based upon the series, was opened in 1989. It is one of the most visited sites in France, with around 1.6 million visitors per year.

Influence in popular culture

- The first French satellite, which was launched in 1965, was named Astérix-1 in honour of Asterix. Asteroid 29401 Asterix was also named in honor of the character. Coincidentally, the word Asterix/Asterisk originates from the Greek for Little Star.

- During the campaign for Paris to host the 1992 Summer Olympics Asterix appeared in many posters over the Eiffel Tower.

- The French company Belin introduced a series of "Asterix" potato chips shaped in the forms of Roman shields, gourds, wild boar, and bones.

- In the UK in 1995, Asterix coins were presented free in every Nutella jar.

- Asterix and Obelix appeared on the cover of Time Magazine for a special edition about France. In a 2009 issue of the same magazine, Asterix is described as being seen by some as a symbol for France's independence and defiance of globalisation.[24] Despite this, Asterix has made several promotional appearances for fast food chain McDonald's, including one advertisement which featured members of the village enjoying the traditional story-ending feast at a McDonald's restaurant.[25]

- Version 4.0 of the operating system OpenBSD features a parody of an Asterix story.[26]

- Action Comics Number 579, published by DC Comics in 1986, written by Lofficier and Illustrated by Keith Giffen, featured an homage to Asterix where Superman and Jimmy Olsen are drawn back in time to a small village of indomitable Gauls.

- Lisa Simpson is delighted at the sight of a rack with Tintin and Asterix comics in a comic book store, depicted in The Simpsons episode "Husbands and Knives".

- In 2005, the The Mirror World Asterix exhibition was held in Brussels. The Belgian post office also released a set of stamps to coincide with the exhibition. A book was released to coincide with the exhibition, containing sections in French, Dutch and English.[27]

- In the episode "Goodnight Mr. Bean", Mr. Bean and Teddy are reading an Asterix comic book.

- Obelix is referenced in The King Blues' 2008 single "My Boulder". The song features the lyrics, "If I'm Obelix, you are my boulder".

- On 29 October 2009, the Google homepage of a great number of countries displayed a logo (called Google Doodle) commemorating 50 years of Asterix.[28]

See also

- Bande dessinée

- English translations of Asterix

- List of Asterix games

- List of Asterix volumes

- Kajko i Kokosz

- Roman Gaul, after Julius Caesar's conquest of 58–51 BC that consisted of five provinces

References

- ^ volumes-sold (8 October 2009). "Asterix the Gaul rises sky high". Reuters.

- ^ Sonal Panse. "Goscinny and Uderzo". Buzzle.com. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "René Goscinny". Comic creator. Archived from the original on 24 March 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ BDoubliées. "Pilote année 1959" (in French).

- ^ a b c Kessler, Peter (2). Asterix Complete Guide (First ed.). Hodder Children's Books;. ISBN 0-340-65346-9.

{{cite book}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help); Check date values in:|date=and|year=/|date=mismatch (help); Cite has empty unknown parameters:|laydate=,|separator=,|trans_title=,|trans_chapter=,|laysummary=,|chapterurl=, and|lastauthoramp=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b Hugh Schofield (22 October 2009). "Should Asterix hang up his sword ?". London: BBC News.

- ^ Matt Selman (21 January 2009). "An Open Letter to Albert Uderzo". Techland.com. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

- ^ Shirbon, Estelle (14 January 2009). "Asterix battles new Romans in publishing dispute". Reuters. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

- ^ "Divisions emerge in Asterix camp". BBC News Online. London. 15 January 2009. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 16 January 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Anne Goscinny: "Astérix a eu déjà eu deux vies, du vivant de mon père et après. Pourquoi pas une troisième?"" (in French). Bodoï.

- ^ "Asterix attraction coming to the UK". BBC News Online. 12 October 2011. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ Rich Johnston (15 October 2012). "Didier Conrad Is The New Artist For Asterix". Bleeding Cool. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ^ AFP (10 October 2012). "Astérix change encore de dessinateur" (in French). Le Figaro. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|site=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|trans_title=ignored (|trans-title=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Kessler, Peter (1997). The Complete Guide to Asterix (The Adventures of Asterix and Obelix). Distribooks Inc. ISBN 0-340-65346-9.

- ^ "October 2009 Is Asterix'S 50th Birthday". Teenlibrarian.co.uk. 9 October 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "Les albums hors collection - Astérix et ses Amis - Hommage à Albert Uderzo". Asterix.com. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

- ^ "The vital statistics of Asterix". London: BBC News. 18 October 2007. Archived from the original on 8 February 2010. Retrieved 10 March 2010.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ a b c "Asterix around the World". asterix-obelix-nl.com. Archived from the original on 23 January 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ http://www.asterix.com/encyclopedia/translations/asterix-in-latin.html

- ^ a b "Translations". Asterix.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "List of Asterix comics published in Greece by Mamouth Comix" (in Greek).

- ^ "Astérix & Obélix: Mission Cléopâtre". Soundtrack collectors. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- ^ "Astérix aux jeux olympiques". IMD. 2008. Archived from the original on 4 February 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Cendrowicz, Leo (21 October 2009). "Asterix at 50: The Comic Hero Conquers the World". TIME. Archived from the original on 24 October 2009. Retrieved 21 October 2009.

{{cite news}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ "Asterix the Gaul seen feasting at McDonald's restaurant". www.meeja.com.au. 19 August 2010. Retrieved 19 August 2010.

- ^ "OpenBSD 4.0 homepage". Openbsd.org. 1 November 2006. Archived from the original on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 31 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ The Mirror World exhibition official site

- ^ Google (29 October 2009). "Asterix's anniversary". Retrieved 27 January 2012.

{{cite web}}:|author=has generic name (help)

Sources

- Astérix publications in Pilote BDoubliées Template:Fr icon

- Astérix albums Bedetheque Template:Fr icon

External links

- Official site

- Asterix Wikia

- Asterix the Gaul at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012.

- Asterix around the World – The many languages

- Alea Jacta Est (Asterix for grown-ups) Each Asterix book is examined in detail

- Les allusions culturelles dans Astérix - Cultural allusions Template:Fr icon

- The Asterix Annotations – album-by-album explanations of all the historical references and obscure in-jokes