Christianity in the Middle East

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 12–16 million (2011)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 8.9 million (est.)[2][a] 7.7–15.4 million (2005)[5] | |

| 1,700,000–2,300,000 (2011)[2][6] | |

| 1,500,000–1,800,000 (2011)[2] | |

| 793,000 (2008)[7] | |

| 300,000[8] (490,000[2][a]) | |

| 300,000–370,000[9] | |

| 175,000–400,000[2] | |

| 144,000[2] (196,000[2][a]) | |

| 120,000[10][11] (310,000[12][a]) | |

| 50,000[13] (75,000[2][a]) | |

| 1,000[14] (88,000[2][a]) | |

| 400[15](450,000[16][a]) | |

| <100 (41,000[2][a]) | |

| <10 (168,000[2][a]) | |

| 0 (1,200,000[2][a]) | |

| 0 (944,000[2][a]) | |

| 0 (120,000[2][a]) | |

| Languages | |

| Arabic, Aramaic, Coptic, Armenian, Greek, Georgian, Kurdish, Persian, Turkish, Hebrew, Bulgarian | |

| Religion | |

| Christianity | |

[a].^ (including foreign residents) | |

Christianity, which originated in the Middle East in the 1st century AD, had been one of the major religions of the region from 4th-century Byzantine reforms and until the Arab Muslim conquests of the mid-to-late 7th century AD. Christianity in the Middle East is characterized with its diverse beliefs and traditions, compared to other parts of the old world. Christians now make up 5% of the Middle Eastern population, down from 20% in the early 20th century.[17]

The number of Middle Eastern Christians is dropping due to such factors as low birth rates compared with Muslims, disproportionately high emigration rates, and ethnic and religious persecution. In addition, political turmoil has been and continues to be a major contributor pressing indigenous Middle Eastern Christians of various ethnicities towards seeking security and stability outside their homelands. Recent spread of Jihadist and Salafist ideology, foreign to the tolerant values of the local communities in Syria and Egypt has also played a role in unsettling Christians' decades-long peaceful existence.[18] In 2011, it was estimated that at the present rate, the Middle East's 12 million Christians would likely drop to 6 million by the year 2020.[19]

Proportionally, Lebanon has the highest rate of Christians in the Middle East, where the percentage ranges between 39% and 40.5%, followed by Egypt where most likely Christians (especially ethnic Copts) account for about 10 percent.

The largest Christian group in the Middle East is the Arabic-speaking Copts, who number 6–11 million people,[3] although Coptic sources claim the figure is closer to 12–16 million.[20][21] Copts reside mainly in Egypt, but also in Sudan and Libya, with tiny communities in Israel, Cyprus, Jordan, Lebanon, and Tunisia.

The second largest Christian group in the Middle East is the Arabic-speaking Maronites who are Catholics and number some 1.1–1.2 million across the Middle East, mainly concentrated within Lebanon. Many Maronites often avoid an Arabic ethnic identity in favour of a pre-Arab Phoenician-Canaanite heritage, to which most of the Lebanese population belongs. In Israel, Maronites are classified as ethnic Arameans and not Lebanese (together with smaller Aramaic-speaking Christian populations of Syriac Orthodox and Greek Catholics).

The Arab Christians, who mostly descended from Arab Christian tribes, are adherents of the Eastern Orthodox Church. They number more than 1.5 million. Roman Catholics of the Latin Rite are small in numbers. Most Catholics are Maronite, Melkites, Catholic Syrians, Armenians and Chalaeans (from Iraq).Protestants altogether number about 400,000. Arabized Catholic Melkite Christians of the Byzantine Rite, who are usually referred as Arab Christians as well, number over 1 million in the Middle East. They came into existence as a result of a schism within the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch over election of a Patriarch in 1724.

The Eastern Aramaic speaking Assyrians of Iraq, southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran and northeastern Syria, who number 2–3 million, have suffered both ethnic and religious persecution over the last few centuries such as the Assyrian Genocide conducted by the Ottoman Turks, leading to many fleeing and congregating in areas in the north of Iraq and northeast of Syria. The great majority are Catholic Chalaeans. In Iraq, the numbers of Assyrians has declined to between 250,000 to 300,000 (from 0.8–1.4 million before 2003 US invasion). Christians were 6-6% of the population in 2003.[22] During 2014, the Assyrian population of North Iraq collapsed due to the Jihadist persecution.

The Armenians number around half a million in the Middle East, with their largest community in Iran with 200,000 members.[23] The number of Armenians in Turkey is disputed having a wide range of estimations. More Armenian communities reside in Lebanon, Jordan and to lesser degree in other Middle Eastern countries such as Iraq, Israel and Egypt. The Armenian Genocide during and after World War I drastically reduced the once sizeable Armenian population.

The Anatolian Greeks, who had once inhabited large parts of the western Middle East and Asia Minor, have declined since the Arab conquests and severely reduced in Turkey, as a result of the Asia Minor Catastrophe, which followed World War I. Today the biggest Middle Eastern Greek community resides in Cyprus numbering around 793,000 (2008).[7] Cypriot Greeks constitute the only Christian majority state in the Middle East, although Lebanon was founded with a Christian majority in the first half of the 20th century. In addition, some of the modern Arab Christians (especially Melkites) constitute Arabized Greco-Roman communities.

Smaller Christian groups include; Georgians, Russians and others. Converts such as Kurdish, Turcoman, Iranian, Azeri, Circassian and Arab exist in small numbers. There are currently several million Christian foreign workers in the Gulf area, mostly from the Philippines, India, Sri Lanka and Indonesia. In the Persian Gulf states, Bahrain has 1,000 Christian citizens[14] and Kuwait has 400 native Christian citizens,[15] in addition to 450,000 Christian foreign residents in Kuwait.[16]

Middle Eastern Christians are relatively wealthy, well educated, and politically moderate,[24] as they have today an active role in various social, economical, sporting and political aspects in the Middle East.

History

Evangelization and early history

| Christianity by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Christianity spread rapidly from Jerusalem along major trade routes to major settlements, finding its strongest growth among Hellenized Jews in places like Antioch and Alexandria. The Greek-speaking Mediterranean region was a powerhouse for the Early Church, producing many revered Church Fathers as well as those who became labelled as heresiarchs, such as Nestorius.

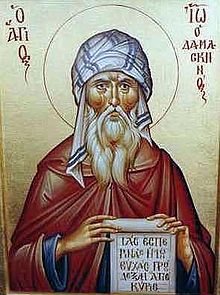

From Antioch, where Christians were first so called, came Ignatius, Diodore of Tarsus, John Chrysostom, Theodore of Mopsuestia, Nestorius, Theodoret, John of Antioch, Severus of Antioch and Peter the Fuller, many of whom are associated with the School of Antioch. In like manner, Alexandria boasted many prominent theologians, including Athenagoras, Pantaenus, Clement, Origen, Dionysius, Gregory Thaumaturgus, Arius, Athanasius, Didymus the Blind, Cyril and Dioscorus, associated with School of Alexandria. The two schools dominated the theological controversies of the first centuries of Christian theology. Whereas Antioch traditionally focused the grammatical and historical interpretation of Scripture and developed a dyophysite christology, Alexandria was much influenced by neoplatonism, using an allegorical interpretation and developing miaphysitism. Other prominent centres of Christian learning developed in Asia Minor (most remarkably among the Cappadocian Fathers) and the Levantine coast (Gaza, Caesarea and Beirut).

Politically, the Middle East of the first four Christian centuries was divided between the Roman Empire and the Parthian Empire (later Sasanian Persia). Christians experienced sporadic persecutions in both political spheres. Within the Parthian Empire, most Christians lived in the region of Mesopotamia/Asuristan (Assyria) and were ethnic Assyrian Mesopotamians who spoke eastern Aramaic dialects loosely related to those Western Aramaic dialects spoken by their co-religionists just across the Roman border. Legendary accounts are of the evangelization of the East by Thomas (Mar Toma), Addai/Thaddaeus and Mari. Syriac emerged as the standard Aramaic dialect of the three Assyrian border cities of Edessa, Nisibis and Arbela. Translation of the scriptures into Syriac began early in this region, with a Jewish group (probably non-rabbinic) producing a translation of the Hebrew Bible becoming the basis of the Church of the Easts Christian Peshitta. Syriac Christianity is most famous for its poet-theologians, Aphrahat, Ephrem, Narsai and Jacob of Serugh.

Eusebius[25] credits Mark the Evangelist as the bringer of Christianity to Egypt, and manuscript evidence shows that the faith was firmly established there by the middle of the 2nd century. Although the Greek-speaking community of Alexandria dominated the Egyptian church, speakers of native Coptic and many bilingual Christians were the majority. From the early 4th century, at the latest, the monastic movement emerged in the Egyptian desert, led by Anthony and Pachomius (see Desert Fathers).

Eusebius (EH 6:20) also mentions the appointment of a bishop and the holding of a synod in Bostra around 240, which is the earliest reference to church organisation in an Arabic-speaking area. Later that decade, Eusebius (6:37) describes another synod in Arabia Petraea. Some scholars have followed hints in Eusebius and Jerome that Philip the Arab, the son of an Arab sheikh, may have been the first Christian Roman Emperor. However, evidence to support this theory is thin. The Ghassanid tribe were important Christian foederati of Rome, while the Lakhmids were an Arab Christian tribe that fought for the Persians. Although the Hejaz was never a stronghold of Arab Christianity, there are reports of Christians around Mecca and Yathrib before the advent of Islam. One hadith even speaks of an icon of the Virgin and Child in the Ka'ba.

Christianity came to Armenia both from the south, Mesopotamia/Assyria, and the west, Asia Minor, as demonstrated by the Greek and Syriac origin of Christian terms in early Armenian texts. Eusebius (EH 6:46, 2) mentions Meruzanes as the bishop of the Armenians around 260. Following the conversion of King Trdat III to Christianity, Gregory the Illuminator was consecrated Bishop of Armenia in 314. Armenians continue to celebrate their church as the oldest national church. Gregory was consecrated at Caesarea in Cappadocia.

The Georgian kingdom of Iberia (Kartli) was probably evangelized first in the 2nd or 3rd century. However, the church was only established there in 330s. A number of sources, both in Georgian and other languages, associate Nino of Cappadocia with bringing Christianity to the Georgians and converting King Mirian III of Iberia. Georgian Christian literature emphasizes her connexion with Jerusalem and the role played the Georgian Jewish community in the growth of Christianity. Certainly, early Georgian liturgy does share a number of conspicuous features with that of Jerusalem. The Black Sea coastal kingdom of Lazica (Egrisi) had closer ties to Constantinople, and its bishops were by imperial appointment. Although the Lazican church originated around the same time as its Iberian neighbour, it was not until 523 when its king, Tzath, accepted the faith. The Iberian church was under the authority of the Patriarch of Antioch, until the reforming king Vakhtang Gorgasali set up an independent catholicos in 467.

In 314, the Edict of Milan proclaimed religious toleration in the Roman Empire, and Christianity rapidly rose to prominence. The church's dioceses and bishoprics came to be modelled on state administration: partly the motive for the Council of Nicaea in 325. However, Christians in the Zoroastrian Sasanian Empire (speaking variously Syriac, Armenian or Greek) are often found distancing themselves politically from their Roman co-religionists to appease the shah. Thus, around 387, when the Armenian Highland came under Sasanian control, a separate leadership from that in Caesarea developed and eventually settled in Echmiadzin, a division that still, to some extent, exists to this day. Likewise, in the 4th century, the bishop of Seleucia-Ctesiphon, the Sasanian capital, was recognised as leader of the Syriac and Greek-speaking Christians in Persia, assuming the title catholicos, later patriarch.

Christianity in Ethiopia and Nubia is traditionally linked to the biblical tale of the conversion of the Ethiopian eunuch in the Acts of the Apostles (8. 26–30). The Kebra Nagast also connects the Yemenite Queen of Sheba with the royal line of Axum. Evidence from coinage and other historical references point to the early 4th-century conversion of King Ezana of Axum as the establishment of Christianity, whence Nubia and other surrounding areas were evangelized, all under the oversight of the Patriarch of Alexandria. In the 6th century, Ethiopian military might conquered a large portion of Yemen, strengthening Christian concentration in southern Arabia.

Schisms

The first major disagreement that led to a fracturing of the church was the so-called Nestorian Schism of the 5th century. This argument revolved around claims by Alexandrians over alleged theological extremism by Antiochians, and its battleground was the Roman capital, Constantinople, originating from its bishop's, Nestorius's, teaching on the nature of Christ. He was condemned for splitting Christ's person into separate divine and human natures, the extremes of this view, however, were not preached by Nestorius. Cyril of Alexandria succeeded in the deposition of Nestorius at the First Council of Ephesus in 431. The result led to a crisis among the Antiochians, some of whom, including Nestorius himself, found protection in Persia, which continued to espouse traditional Antiochian theology. The schism led to the total isolation of the Persian-sphere Church of the East, and the adoption of much Alexandrian theology in the Antiochian sphere of influence.

Some of the Alexandrian victors at Ephesus, however, began to push their anti-Nestorian agenda too far, of whom Eutyches was the most prominent. Much back and forth led to the Council of Chalcedon of 451, which found a compromise that returned to a theology closer to that of Antioch, refereed by Rome, and condemned the monophysite theology of Eutyches. However, the outcome was rejected by many Christians in the Middle East, especially by non-Greek-speaking Christians on the fringe of the Roman Empire – Copts, Syriacs, Assyrians and Armenians. In 482, Emperor Zeno attempted to reconcile his church with his Henotikon. However, reunion was never achieved, and the non-Chalcedonians adopted miaphysitism based on traditional Alexandrian doctrine, in revolt against the Byzantine Church. These so-called Oriental Orthodox Churches include the majority of Egyptian Christians – the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria – majority of Ethiopian and Eritrean Christians – the Ethiopian and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Churchs – many Syriacs – the Syriac Orthodox Church – and the majority of Armenians – the Armenian Apostolic Church.

The name Melkite (meaning 'of the king'), originally intended as a slur, came to be applied to those who adhered to Chalcedon (it is no longer used to describe them), who continued to be organised into the historic and autocephalous patriarchates of Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria and Jerusalem. Collectively they form the traditional basis for the Greek Orthodox Church, known as Rūm Orthodox (Template:Lang-ar) in Arabic, which is their language of worship throughout Egypt, the Palestinian Authority, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria and diaspora. The Georgian Orthodox and Apostolic Church held to a moderate Antiochian doctrine through these schisms and began aligning itself with Byzantium from the early 7th century, and finally broke off ties with their Armenian non-Chalcedonian neighbours in the 720s.

Arab Muslim conquests

The Arab Muslim conquests of the 7th century brought to end the hegemony of Byzantium and Persia over the Middle East. The conquest came at the end of a particularly gruelling period of the Roman-Persian Wars, from the beginning of the 7th century, in which the Sasanid Shah Khosrau II had captured much of the Syria, Egypt, Anatolia and the Caucasus, and the Byzantines under Heraclius only managed a decisive counter-attack in the 620s.

The Greek-Orthodox Patriarch Sophronius negotiated with Caliph Umar in 637 for the peaceful transfer of the city into Arab control (including The Umariyya Covenant). Likewise, resistance to the Arab onslaught in Egypt was minimal. This seems to be more due to the war fatigue throughout the region rather than entirely due to religious differences.

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Turks carried out a series of violent massacres of ethnic Assyrian and Armenian Christians in the 1870s, these killings, which resulted in over ten thousand deaths, were known as the Hamidian massacre.

The Ottoman Turks conducted a large-scale genocide and ethnic cleansing of the ancient and indigenous, Greek, Armenian and Syriacs Christian inhabitants of Anatolia during and immediately after World War I, resulting in well over 1 million deaths and large-scale deportations. A 2008 conference organised by Kurdish PEN reached the conclusion that Turkey was guilty of genocide, estimating that 50,000–80,000 were killed in the aftermath of the Dersim rebellion.[26]

Under European colonial rule

Persecution of Christians in Middle East

Christians in the Middle East face continuous persecution and are often isolated.[27] Although discrimination and persecution of indigenous Christians long predates western colonialism, suspicions of the West prevalent in much of the Middle East and often transformed into outright hatred because of the ravages attributed to Western colonialism, and unqualified support for Israel, has fueled hatred against Christians because they have been perceived as sharing the same religious beliefs with the Western colonialists. Derogatory words and insults are often used on these Pre-Arab and Pre-Islamic Christians, describing them illogically as "illegitimate children of the crusaders" or as "slaves of western colonialists".

In spite of this, every country in the Middle East has at least a small number of believers in Christ from a Muslim background.[28]

Christians today

Bahrain

Bahrain's second biggest religious group is the native Christian minority living in Bahrain.[14] Bahraini Christians number 1,000 people. In the 5th century, Bahrain was a center of Nestorian Christianity, including two of its bishoprics.[29] The ecclesiastical province covering Bahrain was known as Bet Qatraye.[30] Samahij was the seat of bishops. Bahrain was a center of Nestorian Christianity until al-Bahrain adopted Islam in 629 AD.[31] As a sect, the Nestorians were often persecuted as heretics by the Byzantine Empire, but Bahrain was outside the Empire's control offering some safety.

The names of several of Muharraq Island’s villages today reflect this Christian legacy, with Al Dair meaning "the monastery" or "the parish." In 410 AD, according to the Oriental Syriac Church synodal records, a bishop named Batai was excommunicated from the church in Bahrain.[32] Alees Samaan, the current Bahraini ambassador to the United Kingdom is a native Christian.

Egypt

Most Christians in Egypt are ethnic Copts, who are mainly members of the Coptic Orthodox Church. The Coptic language – a derivative of the Ancient Egyptian language, written mainly in the Greek alphabet, is used as the liturgical language of all Coptic churches inside and outside of Egypt. The Copts constitute the largest population of Christians in the Middle East, numbering between 6–11 million.[3] Although ethnic Copts in Egypt now speak Egyptian Arabic (the Coptic language having ceased to be a working language by the 18th century), they believe in an Ancient Egyptian Coptic identity rather than an Arab identity. (also referred to as Pharaonism). The ancient Egyptian language is descended from the Afroasiatic language family which is theorized to originate in Southwest Asia before eventually spreading and entering North Africa. There is a wide range of estimations regarding the numbers of Copts in Egypt, though without an official census there is no reliable official data. In 2008, Coptic groups claimed to compose some 12–16 million people. However, the Egyptian government has accused Christian groups and western media[citation needed] of overestimating the population of Christians in Egypt. Egyptian government sources, however, claim[citation needed] that the actual number of Christians living in Egypt is significantly lower than this.

Many Copts are internationally renowned. Some of the most well known Copts include Boutros Boutros-Ghali, the sixth Secretary-General of the United Nations; Sir Magdi Yacoub, the internationally renowned cardiothoracic surgeon; Hani Azer, the world-leading civil engineer; billionaire Fayez Sarofim, one of the richest men in the world; and Naguib Sawiris, the CEO of Orascom.

Iraq

Christianity has a long history in Iraq, with the early conversions of the indigenous inhabitants of Assyria (Parthian controlled Assuristan) dating from the 1st to 3rd centuries AD. This region was the birthplace of Eastern Rite (Church of the East) Christianity, a flourishing Syriac literary tradition, and the centre of a missionary expansion that stretched as far as India, Central Asia and China.

Assyrian Christians still made up the majority population in northern Iraq until the massacres conducted by Tamurlane in the 14th century. In modern times, Assyrian Christians numbered about 636,000 to 800,000 in 2005, representing 3% to 5% of the population of the country. By the US withdrawal in 2011, the number of Christians in Iraq plunged to as low as roughly 500,000, mostly in Iraqi Kurdistan. The vast majority are Neo-Aramaic speaking ethnic Assyrians (also known as Chaldo-Assyrians), descendant from the ancient Mesopotamians, who are concentrated in the north, particularly the Nineveh Plains, Dohuk region, and in and around cities such as Mosul, Erbil, Kurkuk and in Baghdad. There are also a very small proportion of Arab Christians and small numbers of Armenian, Kurdish, Iranian and Turcoman Christians.

They had numbered over 1.4 million in 1980, or 7% of the population, but almost 400,000 fled to other countries, especially after the Invasion of Iraq in 2003. The Iraqi Christian population is also declining due to lower birth rates and higher death rates than their Muslim compatriots. Since the 2003 invasion, Iraqi Christians suffer from lack of security. Many lived in the capital Baghdad and in Mosul prior to the Iraq war,[33] but most have since fled to northern Iraq, where Assyrian Christians form a majority in some districts. Christians belong to Syriac churches such as the Chaldean Catholic Church, the Assyrian Church of the East, the Ancient Church of the East, the Syriac Catholic Church and the Syriac Orthodox Church, with a small number of Protestant converts. The Iraqi former foreign minister and deputy prime minister Tariq Aziz (real name Michael Youkhanna) is probably the most famous Assyrian Iraqi Christian, along with the footballer Ammo Baba. Assyrians in Iraq have traditionally excelled in business, sports, the arts, music, and the military.

Assyrians are distinct from other Semitic Christian groups in the Middle East in that they have retained their original Neo-Aramaic language and Syriac written script, resisting the adoption of Arabic language.

In his recent PhD thesis[34] and in his recent book[35] the Israeli scholar Mordechai Zaken discussed the history of the Assyrian Christians of Turkey and Iraq (in the Kurdish vicinity) during the last 180 years, from 1843 onwards. In his studies Zaken outlines three major eruptions that took place between 1843 and 1933 during which the Assyrian Christians lost their land and hegemony in their habitat in the Hakkārī (or Julamerk) region in southeastern Turkey and became refugees in other lands, notably Iran and Iraq, and ultimately in exiled communities in Western countries (the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Russia and within many of the 28 EU member states like Sweden, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom). Mordechai Zaken wrote this important study from an analytical and comparative point of view, comparing the Assyrian Christians experience with the experience of the Kurdish Jews who had been dwelling in Kurdistan for two thousands years or so, but were forced to migrate the land to Israel in the early 1950s. The Jews of Kurdistan were forced to leave and migrate as a result of the Arab-Israeli war, as a result of the increasing hostility and acts of violence against Jews in Iraq and Kurdish towns and villages, and as a result of a new situation that had been built up during the 1940s in Iraq and Kurdistan in which the ability of Jews to live in relative comfort and relative tolerance (that was erupted from time to time prior to that period) with their Arab and Muslim neighbors, as they did for many years, practically came to an end. At the end, the Jews of Kurdistan had to leave their Kurdish habitat en masse and migrate into Israel. The Assyrian Christians on the other hand, came to similar conclusion but migrated in stages following each and every eruption of a political crisis with the regime in which boundaries they lived or following each conflict with their Muslim, Turkish, Arabs or Kurdish neighbors, or following the departure or expulsion of their patriarch Mar Shimon in 1933, first to Cyprus and then to the United States. Consequently, indeed there is still a small and fragile community of Assyrians in Iraq, however, millions of Assyrian Christians live today in exile in many communities in the West.[36]

Iran

Iran's Christian minority numbers some 300,000–370,000. Most are ethnic Armenians (up to 250,000–300,000[37]) and Assyrians (up to 40,000), who follow Armenian Orthodox and Assyrian Church of the East Christianity respectively.[38] There are at least 600 churches serving the nation its Christian adherents.[39]

Christianity had an early presence in Iran, dating to Parthian and Sassanid times, although the major religion among the Iranian peoples themselves was Zoroastrianism. The Sassanid Empire was the centre of the Nestorian Church. Many of the early followers were Armenians, and transplanted Assyrians living in the Urmia region, and along the north western border with Mesopotamia. These were added to by other Semites, followers of the Nestorian church, some of whom were Assyrians from Mesopotamia, others being from Syria. Furthermore, there has been a thriving native Christian Armenian community since ancient times in northwestern Iran, nowadays Iranian Azerbaijan. The many Armenian churches and monasteries in the region, such as the notable St. Thaddeus Monastery, are extant remainders of this. Other significantly Christian populated areas in Parthian and Sassanid Iran included the provinces of Persian Armenia, Caucasian Albania, and Caucasian Iberia, amongst others. In the course of the 20th century, Iran's large Christian minority, mainly the native Armenians and Assyrians who have a presence in Iran for millennia, took a heavy blow due to the Assyrian Genocide (by Ottoman troops crossing the border), Armenian Genocide (by Ottoman troops crossing the border), the Iranian Revolution and the Iran–Iraq War. Especially due to the two Ottoman-conducted genocides, regions where Christians even made up majorities or had a significant native historical presence for millennia, never became the same again. However, due to the same genocides, Iran's Christian community was boosted as well at the same time as many migrated to Iran from the Ottoman regions. The 21st century war in Iraq brought another wave of Christian refugees, especially Assyrians and to a lesser extent Armenians. Continuing as of 2015, Christianity is reportedly the fastest growing religion in Iran with an average annual rate of 5.2%.[40]

The most famous contemporary Christian of Iranian origin is probably the American tennis player Andre Agassi, who is ethnically Armenian-Assyrian. The "Armenian Monastic Ensemble", which includes several of the nations most ancient Christian Armenian churches and monasteries, are inscribed on the UNESCO world heritage list.

Israel

Most Christians residing permanently in Israel are Arabs, numbering roughly 135,000, who belong 67% to the Catholic Church.[citation needed] Of all Catholics, 40% belong to the Melkite Greek Catholic Church, 20% to the Latin Church and 7% to the Maronite Church.[citation needed] 32% of all Christians belong to the Greek Orthodox Church and 1% are members of other denominations.[citation needed] Smaller communities of Middle Eastern Christian peoples in Israel also include the Lebanese Maronites, Assyrians, Armenians, Georgians, Copts and Messianic Jews. During the 1990s, the Christian community had been increased due to the immigration of Jewish-Christian mixed marriages, who had predominantly arrived from the countries of the former Soviet Union. This added another 20–30 thousands of mostly Greek Orthodox Christians with Russian and Ukrainian ancestry.

In recent years, the Christian population in Israel has increased significantly by the migration of foreign workers from a number of countries (predominantly the Philippines and Romania). Numerous churches have opened in Tel Aviv, in particular.[42]

Nine churches are officially recognised under Israel's confessional system, for the self-regulation of status issues, such as marriage and divorce. These are the Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic (Latin rite), Gregorian-Armenian, Armenian Catholic, Syriac Catholic, Chaldean (Uniate), Melkite (Greek Catholic), Assyrian Church of the East, Ethiopian Orthodox, Maronite and Syriac Orthodox churches. There are more informal arrangements with other churches such as the Anglican Church and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Arab Christians are one of the most educated groups in Israel. Maariv have describe the Arab Christians sectors as "the most successful in education system",[43] since Arab Christians fared the best in terms of education in comparison to any other group receiving an education in Israel.[41] Arab Christians have one of the highest rates of success in the matriculation examinations, (64%)[41] both in comparison to the Muslims and the Druze and in comparison to all students in the Jewish education system as a group.[41] The rate of students studying in the field of medicine was also higher among the Arab Christian students, compared with all the students from other sectors. The percentage of Arab Christian women who are higher education students is higher than other sectors.[43]

Jordan

In Jordan, Christians constitute about 7% of the population (about 400,000 people).[2] This percentage represents a sharp decrease from a figure of 18% in the early 20th century. This drop is largely due to an influx of Muslim Arabs from the Hijaz after the First World War, low birth rates in comparison with Muslims and the large numbers of Palestinians (85–90% Muslim) who fled to Jordan after 1948. Almost 50% of Jordanian Christians belong to the Eastern Orthodox Church. 45% are Catholics,[44] with a small minority adhering to Protestantism. Christians are well integrated in the Jordanian society and have a high level of freedom. Nearly all Christians belong to the middle or upper classes. Moreover, Christians enjoy more economic and social opportunity in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan than elsewhere in the Middle East and North Africa. They have a disproportionately large representation in the Jordanian parliament (10% of the Parliament) and hold important government portfolios, ambassadorial appointments abroad, and positions of high military rank. A survey by a Western embassy found that half of Jordan's prominent business families were Christians. Christians run about a third of Jordan's economy.[45]

Jordanian Christians are allowed by the public and private sectors to leave work to attend Divine Liturgy or Mass on Sundays. All Christian religious ceremonies are publicly celebrated. Christians have established good relations with the royal family and the various Jordanian government officials and they have their own ecclesiastic courts for matters of personal status.

Most native Christians in Jordan identify themselves as Arab, though there are also non-Arab Assyrian/Syriac, Armenian and Maronite groups in the country.

Lebanon

Lebanon holds the largest proportion of Christians in the Arab world proportionally and falls behind only Egypt and Syria in absolute numbers. Christians formed a majority of Lebanon's population before the Lebanese Civil War, but now are believed to form a large minority. However, if one counts the estimated 8–14-million-strong Lebanese diaspora, they form far more than the majority of the population. The exact number of Christians is uncertain because no official census has been made in Lebanon since 1932. Lebanese Christians belong mostly to the Maronite Catholic Church and Greek Orthodox, with sizable minorities belonging to the Melkite Greek Catholics. Lebanese Christians are the only Christians in the Middle East with a sizable political role in the country, as a result of the National Pact. As a result of it, the Lebanese president, half of the cabinet, and half of the parliament follow one of the various Lebanese Christian rites.[46]

Maronite tradition can be traced back to Saint Maron in the 4th century, the founder of national and ecclesiastical Maronitism. Saint Maron adopted an ascetic, reclusive life on the banks of the Orontes river near Homs–Syria and founded a community of monks who preached the Gospel in the surrounding area. The Saint Maron Monastery was too close to Antioch, making the monks vulnerable to emperor Justinian II’s persecution. To escape persecution, Saint John Maron, the first Maronite patriarch-elect, led his monks into the Lebanese mountains; the Maronite monks finally settled in the Qadisha valley. During the Muslim conquest, Muslims persecuted the Christians, particularly the Maronites, with the persecution reaching a peak during the Umayyad caliphate. Nevertheless, the influence of the Maronite establishment spread throughout the Lebanese mountains and became a considerable feudal force[citation needed]. After the Muslim Conquest, the Maronite Church became isolated and did not reestablish contact with the Church of Rome until the 12th century.[47] According to Kamal Salibi, a Lebanese Protestant Christian, some Maronites may have been descended from an Arabian tribe, who immigrated thousands of years ago from the Southern Arabian Peninsula. Salibi maintains "It is very possible that the Maronites, as a community of Arabian origin, were among the last Arabian Christian tribes to arrive in Syria before Islam".[47] Many Lebanese Maronite Christians reject this, however, and point out that they are of pre-Arab origin.

Many Lebanese Maronite Christians consider themselves of indigenous Phoenician ancestry, arguing that their presence predates the arrival of Arabs in the region. Though they originate from the Orontes river near Homs, Syria and founded a community of monks who left the Syriac Orthodox church.

Turkey

Christianity has a long history in Anatolia (now part of the Republic of Turkey), which is the birthplace of numerous Christian Apostles and Saints, such as Paul of Tarsus, Timothy, Nicholas of Myra, Polycarp of Smyrna and many others. Two out of the five centers (Patriarchates) of the ancient Pentarchy are in Turkey: Constantinople (Istanbul) and Antioch (Antakya). Antioch was also the place where the followers of Jesus were called "Christians" for the first time in history, as well as being the site of one of the earliest and oldest surviving churches, established by Saint Peter himself. For a thousand years, the Hagia Sophia was the largest church in the world.

The Assyrian and Armenian peoples have an ancient history in southeastern Anatolia, dating back to 2000 BC and 600 BC respectively, both of these peoples were Christianized between the 1st and 3rd centuries AD. Similarly, the Greeks of western Anatolia and Georgians of the Black Sea region have histories dating from the 20th and 10th centuries BC respectively, and were also Christianized during the first few centuries AD.

These ancient Christian ethnic groups were drastically reduced by genocide during and after World War I (see Armenian Genocide, Assyrian Genocide and Greek Genocide) at the hands of the Ottoman Turkish army and their Kurdish allies. Population exchange between Greece and Turkey is another reason.

The percentage of Christians in Turkey fell from 19 percent in 1914 to 2.5 percent in 1927,[48] due to events which had a significant impact on the country's demographic structure, such as the Armenian Genocide, the population exchange between Greece and Turkey,[49] and the emigration of Christians (such as Levantines, Greeks, Armenians etc.) to foreign countries (mostly in Europe and the Americas) that actually began in the late 19th century and gained pace in the first quarter of the 20th century, especially during World War I and after the Turkish War of Independence.[50] Today there are more than 160,000 people of different Christian denominations, representing less than 0.2 percent of Turkey's population,[51] including an estimated 80,000 Oriental Orthodox,[52] 35,000 Roman Catholics,[53] 18,000 Antiochian Greeks,[54] 5,000 Greek Orthodox[52] and smaller numbers of Protestants (Mostly ethnic Turkish).[55] Currently there are 236 churches open for worship in Turkey.[56] The Eastern Orthodox Church has been headquartered in Istanbul since the 4th century.[57][58]

Palestine

About 173,000 Arab Palestinian Christians lived in the Palestinian Authority (including the West Bank and Gaza Strip) in the 1990s.[33] Both the founder of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, George Habash, and the founder if its offshoot the DFLP, Nayif Hawatmeh, were Christians, as is prominent Palestinian activist and former Palestinian Authority minister Hanan Ashrawi. Nowadays, 50% of all Palestinian Christians are Catholics.[44]

Over the last years, unlike the increase trend in the Christian population of Israel, the number of Christians in the Palestinian Authority has declined severely. The decline of Christianity in the Palestinian Authority is largely attributed to poor birth rates, compared with the dominant Muslim population; and anti-Christian attitudes by radical Muslim organizations and the general Muslim public. The updated number of Arab Christians in the Palestinian Authority is under 75,000.[2]

Gaza Strip

Since the Hamas takeover of the Gaza Strip in 2007, anti-Christian attitudes have been on the increase. Unlike in the Palestinian National Authority, the Hamas administration does not include Christians. From about 2,000[46]–3,000[citation needed] Christians before Hamas takeover, as few as several hundred remain in the Gaza Strip under Hamas Administration. Most of the Christians of Gaza relocated to the West Bank or abroad.[citation needed]

Syria

In Syria, Christians formed just under 15% of the population (about 1.2 million people) according to the 1960 census, but no newer census has been taken. Current estimates suggest that they comprise about 10% of the population (1,700,000–2,300,000 [2][6]) due to having lower birth rates and higher emigration rates than their Muslim compatriots. The largest Churches are the Greek Orthodox and Greek Catholic.[46] There are also Syrian Orthodox, Syrian Catholic, Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholic, Assyrian Church of the East and Chaldean Catholic Church (see Iran and Iraq) Christians.[46]

Syrian Christians are largely Arabic-speaking Christians in the bulk of the country (though some may identify as ethnic Arameans), in the big cities there are many ethnic Armenians, and in the northeastern Al-Hasakah Governorate the majority of the Christians are ethnic Assyrians.

Migration

Many millions of Middle Eastern Christians currently live in the diaspora, elsewhere in the world. These include such countries as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, the United States and Venezuela among them. There are also many Middle Eastern Christians in Europe, especially in the United Kingdom, France (due to its historical connections with Lebanon, Egypt, Syria), and to a lesser extent, Ireland, Germany, Spain, Italy, Greece, Bulgaria, Russia, and the Netherlands.

The largest number of Middle Eastern Christians residing in the diaspora is that of Lebanese Christians, who have migrated out of Lebanon for security and economic reasons since WWI. Many fled Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War. The countries with significant Lebanese Christians include such countries as Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Cyprus, Dominican Republic, Germany, Greece, France, Mexico, New Zealand, Sweden, United Kingdom, United States and Venezuela among them.

Assyrian Christians currently reside in diaspora with large communities in the US, Canada, Australia and Europe, reaching more than a million outside of the Middle East. Much of these is attributed to the massive Assyrian Christian exodus from northern Iraq following the 2003 invasion and the consequent Iraq War, and from northeastern Syria following the 2011 Arab Spring and the consequent Syrian Civil War.

Among the Arab Christians, about 400,000 Palestinian Christians reside in the diaspora, largely in the Americas, where their communities have been established since the late 19th century and peaked following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. More emigrated from Lebanon during the Lebanese Civil War.

The majority of self-identifying Arab Americans are Eastern Rite Catholic or Orthodox Christian, according to the Arab American Institute, although most Middle Eastern Christians in the US do not identify as Arabs.[verification needed] On the other hand, most American Muslims are black (African Americans or Sub-Saharan Africans) or of South Asian (Indian, Pakistani or Bangladeshi) origin.

Churches

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (January 2008) |

Coptic Christians

The largest Christian community in the Middle East are the Copts of Egypt, whose churches are mainly divided into:

- Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria

- Coptic Catholic Church

- Evangelical Church of Egypt (Synod of the Nile)

Assyrian Christians

Many Christians in the Middle East are Semitic followers of Syriac Christianity, are ethnically and linguistically distinct from Arabs, and divided into:

- Assyrian Church of the East, (also known as the Church of the East and somewhat inaccurately as the Nestorian Church) 1st century AD – Mainly found among the ethnic Assyrians of Iraq, Iran, south east Turkey and north east Syria.

- Ancient Church of the East since the 20th century – An offshoot of the Assyrian Church of the East. Mainly found in Iraq, Iran, south east Turkey and north east Syria

- Chaldean Catholic Church offshoot of the Assyrian Church since 1683 AD - ethnically the same as Assyrians, made up of Assyrian converts to Catholicism. Mainly found in Iraq, Iran, south east Turkey and north east Syria. Sometimes called Chaldo-Assyrians to avoid division on theological lines.

- Assyrian Evangelical Church – Made up of ethnic Assyrian converts to Protestantism, since 20th century. Mainly found in Iraq, Iran, south east Turkey and north east Syria

- Assyrian Pentecostal Church - Made up of ethnic Assyrian converts to Protestantism, since 20th century. Mainly found in Iraq, Iran, south east Turkey and north east Syria

- Syrian Orthodox Church (also known as the Jacobite Church and sometimes Assyrian Orthodox Church)[59] 1st century AD. Mainly found in Syria, south central Turkey and to a small degree in Iraq and even a smaller degree in Kerala, India by the Syrian Malabar Nasranis.

- Syriac Catholic Church since the 18th century. Mainly in Syria and Iraq.

- Maronite Church, in union with Rome, since the 5th century AD (Mainly living in Lebanon and with large diaspora)

Arab, Greek and Melkite Christians

Christians, belonging mostly to Greek Orthodox and Melkite churches:

All of them are mainly found in countries like Jordan, Israel, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and to a lesser degree in Yemen, Oman, Egypt and Libya.

Armenian Christians

There is also the Armenian Church with its divisions:

Armenia, historically, was the first state to accept Christianity. There are small numbers of Russian Orthodox and Assyrian Christians in Armenia also. Armenian Christians are also to be found in Lebanon, Syria, Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Egypt and the Gulf states as expats.

Georgian Christians

In Georgia, the majority of the population belongs to the Georgian Orthodox Church. The Russian Orthodox Church, the Armenian Churches, the Assyrian Church of the East and the Roman Catholic Church also have adherents there.

Kurdish Christians

The Kurdish-Speaking Church of Christ (The Kurdzman Church of Christ) is an Evangelical church with mainly Kurdish adherents.

Anglicans

The Episcopal Church in Jerusalem and the Middle East is the Anglican church responsible for the Middle East and North Africa. It is quite small, with only some 35,000 members throughout the area.

Turkish Christians

Notable Middle Eastern Christians

Notable Christians of Middle Eastern ancestry in Middle East and Diaspora:

- Andre Agassi – former Iranian-American tennis player (Assyrian-Armenian descent)

- Alees Samaan, the Bahraini ambassador to the United Kingdom.

- Fairuz, Lebanese singer. (Orthodox Christian, originally Maronite)

- Boutros Boutros-Ghali, Egyptian-American 6th Secretary-General of the United Nations (Coptic Orthodox Christian)

- Elias Chacour Archbishop, prominent reconciliation and peace activist in Israel (Melkite Greek Catholic Christian)

- Michel Aflaq, Syrian founder of pan-Arabist Baath party, (Greek Orthodox Christian).

- Tariq Aziz, former Iraqi (Baath party) foreign minister and deputy prime minister (Chaldean Catholic Christian, an ethnic Assyrian)

- Suleiman Mousa, prominent Jordanian historian and author of T.E. Lawrence: An Arab View, (Catholic Christian).

- George Wassouf, Syrian singer (an ethnic Syriac)[citation needed][dubious – discuss].

- Edward Said, prominent Palestinian intellectual and writer (Greek Orthodox Christian background).

- Constantin Zureiq, prominent Syrian intellectual and academic (Greek Orthodox Christian).

- George Habash, Palestinian founder of PFLP (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Nayef Hawatmeh, Jordanian founder of DFLP (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Said Khoury, Palestinian entrepreneur, co-founder of the Consolidated Contractors International Company, (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Yousef Beidas, prominent Palestinian Financier (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- John Sununu, US political leader of Palestinian-Lebanese background (Melkite Greek Catholic Christian).

- Hanan Ashrawi, Palestinian scholar and politic activist (Anglican Arab Christian).

- Kamal Salibi, Lebanese historian and scholar (Protestant Christian).

- Steve Bracks (from the Barakat Lebanese family) Australian State MP, Premier of Victoria, Australia, (Catholic Arab Christian).

- René Angélil, Canadian producer and husband of Céline Dion of Lebanese-Syrian background (Greek Catholic Christian).[60]

- Carlos Menem, president of Argentina from 1988 to 1999 of Syrian background (ethnically Arab converted to Roman Catholic from Sunni Islam)

- Emile Habibi, Arab Israeli writer (Anglican Christian).

- Azmi Bishara, former Arab Israeli Knesset member, now residing in Qatar (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Azmi Nassar, Arab Israeli manager of the Palestinian national football team (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Salim Tuama, Hapoel Tel Aviv middlefielder, (Arab citizen of Israel (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Simon Shaheen, Israeli oud and violin virtuoso and composer (Greek Catholic Arab Christian)

- Salim Jubran, member of the Israeli Supreme Court (Maronite Christian)

- Ralph Nader, US Presidential candidate and consumers' rights activist of Lebanese background (Greek Orthodox background, but declines to comment on personal religion).

- Hani Naser, musician, producer (son of Jordanian Christian immigrants).

- Shakira, international superstar from Colombia, daughter of Lebanese father from Zahle and Colombian mother of Spanish and Catalan descent (Greek Orthodox Christian).

- Tony Shalhoub, three-time Emmy Award and Golden Globe-winning American television and film actor of Lebanese background (Maronite Christian).

- Marie Keyrouz, chanter of Eastern Church music, Melkite Greek Catholic nun. Founder of L'Ensemble de la Paix (Ensemble of Peace) and Founder-President of L'Instituit International de Chant Sacré (International Institute of Sacred Chant) in Paris.

- Julio César Turbay, president of Colombia from 1978 to 1982 from Lebanese background (Maronite Christian).

- Carlos Slim Helú, Mexican businessman of Lebanese background (Maronite Christian).

- Bruno Bichir and Demián Bichir, Mexican actors of Lebanese background (Maronite Christians).

- Amin al-Rihani, Lebanese writer and intellectual (Maronite Christian).

- Afif Safieh, Palestinian diplomat (Greek Catholic Arab Christian).

- Bobby Rahal, race car driver, team owner, and businessman of Lebanese background (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Doug Flutie, Heisman Trophy winner, NFL quarterback of Lebanese origin (Maronite Christian).

- Jacques Nasser, past CEO Ford Motor Company, French-American of Lebanese descent (Greek Orthodox Christian).

- Helen Thomas, Whitehouse Journalist, American of Lebanese descent (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- George Mitchell, former US Senator and Politician of Lebanese background (Maronite Christian).

- John Mack, former chairman & CEO of Morgan Stanley - an American of Lebanese descent (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).

- Mosab Hassan Yousef, author of Son of Hamas, American of Palestinian descent (Protestant Arab Christian, converted from Islam).

- Vartan Gregorian, American academic and president of Carnegie Corporation of New York (Iranian-Armenian descent).

- Alex Agase, American – Top level American Football (gridiron) player (Assyrian).

- Lou Agase, American – Top level American Football (gridiron) player (Assyrian).

- Mitch Daniels – Governor of Indiana and potential Republican presidential candidate (Syrian, Greek Orthodox).

- Rosie Malek-Yonan, Iranian-American actress, author, director, public figure and activist. (Assyrian descent).

- Adam Benjamin, Jr., Indiana Congressman (Assyrian).

- Anna Eshoo, California Congressman (Assyrian).

- John Nimrod, Illinois Senator (Assyrian).

- Aril Brikha, techno/nouse music artist (Assyrian).

- Linda George, singer (Assyrian).

- Sargon Gabriel, singer (Assyrian).

- Klodia Hanna, Miss Iraq 2006 (Assyrian).

- Christian Demirtaş, German footballer (Assyrian).

- Daniel Unal, Turkish Footballer – playing for FC Basle in Switzerland (Assyrian Christian).

- Peter Medawar, He was awarded the 1960 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, He is from Lebanese descent (Maronite Christian).[61]

- Elias James Corey, He won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, he is from Lebanese descent (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).[62]

- Tony Fadell, Lebanese American inventor and is known as "one of the fathers of the iPod" (Greek Orthodox ).[63]

- Michael E. DeBakey, World-renowned American cardiac surgeon of Lebanese origin (Maronite Christian).[64]

- Michael Atiyah, British mathematician specialising in geometry (Greek Orthodox Arab Christian).[65]

See also

- Arab Christians

- Rûm Christians or Rum Millet

- Antiochian Greek Christians

- Tantur Ecumenical Institute

- Middle East Council of Churches

References

- ^ Malik, Habib. "The Future of Christians in the Middle East | Hoover Institution". Hoover.org. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r "Guide: Christians in the Middle East". BBC News. 11 October 2011.

- ^ a b c "Coptic Orthodox Church". BBC. Retrieved 27 February 2011. "estimates [for the Coptic Orthodox Church] ranged from 6 to 11 million; 6% (official estimate) to 20% (Church estimate)"

- ^ "Egypt". The World Factbook. CIA. July 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011. "Religions: Coptic 9%", "Population (Egypt): 82,079,639 (July 2011)".

- ^ Khairi Abaza and Mark Nakhla (25 October 2005). "The Copts and Their Political Implications in Egypt". The Washington Institute. Retrieved 27 August 2010. "Christians make up 10–20 percent of Egypt's population of seventy-seven million, though precise estimates of the number of Copts vary widely."

- ^ a b "Syria - International Religious Freedom Report 2006". U.S. Department of State. 2006. Retrieved 28 June 2009.

- ^ a b "2008 estimate". cia.gov. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ^ Christian Official: The Number of Christians in Iraq Has Dropped to Three-Hundred Thousand

- ^ "Christians and Christian converts, Iran, December 2014, p.9" (PDF). Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ Deutsche Welle - Christians in Turkey are second-class citizens

- ^ Washington Post - 3 things Pope Francis hopes to accomplish in Turkey

- ^ المسيحية في العالم: تقرير حول حجم السكان المسيحيين وتوزعهم في العالم، مركز الأبحاث الاميركي بيو، 19 ديسمبر 2011. Template:En icon

- ^ [1]

- ^ a b c "Jew, Christian In Bahrain Chamber". Retrieved 15 June 2012. Cite error: The named reference "bah" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b "International Religious Freedom Report". US State Department. 1999.

- ^ a b "International Religious Freedom Report for 2012". US State Department. 2012.

- ^ Willey, David (10 October 2010). "Rome 'crisis' talks on Middle East Christians". BBC. Retrieved 1 November 2010.

- ^ Chrisafis, Angelique; Kingsley, Patrick; Beaumont, Peter (9 February 2013). "Violent tide of Salafism threatens the Arab spring". The Guardian. London.

- ^ Daniel Pipes. "Disappearing Christians in the Middle East". Daniel Pipes. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "?". United Copts of Great Britain. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 27 August 2010. "In 2008, Pope Shenouda III and Bishop Morkos, bishop of Shubra, declared that the number of Copts in Egypt is more than 12 million." (Arabic)

- ^ "?". العربية.نت الصفحة الرئيسية. Retrieved 27 August 2010. "In 2008, father Morkos Aziz the prominent priest in Cairo declared that the number of Copts (inside Egypt) exceeds 16 million."

- ^ "With Arab revolts, region's Christians mull fate". English.alarabiya.net. 3 October 2011. Retrieved 22 October 2011.

- ^ "Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia: Political Developments and Implications ..." Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ Pope to Arab Christians: Keep the Faith.

- ^ Ecclesiastical History 2:16, 24.

- ^ The Dersim Massacre: Turkish Destruction of the Kurdish People in the Dersim Region

- ^ Fearing Change, Many Christians in Syria Back Assad, New York Times

- ^ Johnstone, Patrick; Miller, Duane Alexander (2015). "Believers in Christ from a Muslim Background: A Global Census". IJRR. 11: 1–19. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University of Chicago Press, 1984

- ^ Nestorian Christianity in the Pre-Islamic UAE and Southeastern Arabia, Peter Hellyer, Journal of Social Affairs, volume 18 number 72 winter 2011, p. 88.

- ^ Curtis E. Larsen. Life and Land Use on the Bahrain Islands: The Geoarchaeology of an Ancient Society University Of Chicago Press, 1984.

- ^ Jean Francois Salles, p. 132.

- ^ a b "Arab Christians – National Geographic Magazine". Ngm.nationalgeographic.com. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ Mordechai Zaken,"Tribal chieftains and their Jewish Subjects: A comparative Study in Survival: PhD Thesis, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2004.

- ^ Mordechai Zaken,"Jewish Subjects and their tribal chieftains in Kurdistan: A Study in Survival", Brill: Leiden and Boston, 2007.

- ^ Joyce Blau, one of the world's leading scholars in the Kurdish culture, languages and history, suggested that "This part of Mr. Zaken’s thesis, concerning Jewish life in Iraqi Kurdistan, "well complements the impressive work of the pioneer ethnologist Erich Brauer. Brauer was indeed one of the most skilled ethnographs of the first half of the 20th century and wrote an important book on the Jews of Kurdistan [Erich Brauer, The Jews of Kurdistan, First edition 1940, revised edition 1993, completed and edited par Raphael Patai, Wayne State University Press, Detroit]

- ^ "In Iran, 'crackdown' on Christians worsens". Christian Examiner. Washington D.C.: Christian Examiner. April 2009. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "Iran – International Religious Freedom Report 2009". The Office of Electronic Information, Bureau of Public Affair. 2009-10-26. Retrieved 2009-12-01.

- ^ "Andranik Teymourian the First Christian to Lead Iran's Football Team retrieved July 2015

- ^ "Religion and Religious Freedom". Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d Christians in Israel: Strong in education

- ^ Adriana Kemp & Rebeca Raijman, "Christian Zionists in the Holy Land: Evangelical Churches, Labor Migrants, and the Jewish State", Identities: Global Studies in Power and Culture, 10:3, 295–318

- ^ a b המגזר הערבי נוצרי הכי מצליח במערכת החינוך

- ^ a b [2]

- ^ الشرق الأوسط.. هاجس يصعب احتماله، الشروق، 2 مايو 2011.

- ^ a b c d [3]

- ^ a b Salibi, Kamal., A house of Many Mansions: The History of Lebanon Reconsidered., University of California Press., Berkeley, 1988. p. 89

- ^ Içduygu, Ahmet; Toktas, Şule; Ali Soner, B. (1 February 2008). "The politics of population in a nation-building process: emigration of non-Muslims from Turkey". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 31 (2): 358–389. doi:10.1080/01419870701491937.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Chapter The refugees question in Greece (1821–1930) in "Θέματα Νεοελληνικής Ιστορίας", ΟΕΔΒ ("Topics from Modern Greek History"). 8th edition". Nikolaos Andriotis. 2008.

{{cite web}}:|format=requires|url=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "'Editors' Introduction: Why a Special Issue?: Disappearing Christians of the Middle East" (PDF). Editors' Introduction. 2001. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Religions". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ a b "Foreign Ministry: 89,000 minorities live in Turkey". Today's Zaman. 15 December 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2011.

- ^ "Statistics by Country". http://www.catholic-hierarchy.org. Retrieved 18 February 2015.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Christen in der islamischen Welt – Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte" (PDF). 2008. Retrieved 11 June 2013.

- ^ "Turkish Protestants still face "long path" to religious freedom". http://www.christiancentury.org. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ "Life, Culture, Religion". Official Tourism Portal of Turkey. 15 April 2009. Archived from the original on 15 April 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ William G. Rusch (2013). The Witness of Bartholomew I, Ecumenical Patriarch. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8028-6717-9.

Constantinople has been the seat of an archiepiscopal see since the fourth century; its ruling hierarch has had the title of"Ecumenical Patriarch" ...

- ^ Erwin Fahlbusch; Geoffrey William Bromiley (2001). The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 40. ISBN 978-90-04-11695-5.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople is the ranking church within the communion of ... Between the 4th and 15th centuries, the activities of the patriarchate took place within the context of an empire that not only was ...

- ^ Assyrian Orthodox Church (Oriental Orthodox)

- ^ "À voir à la télévision le samedi 24 mars - Carré d'as". Le Devoir. Retrieved 26 July 2010.

- ^ "Sir Peter Medawar". New Scientist. 12 April 1984. Retrieved 27 February 2014.

- ^ Elias James Corey – Autobiography

- ^ Krazit, Tom (3 November 2008). "Report: Tony Fadell, iPod chief, to leave Apple post". CNET News.

- ^ Salem, Philip A. "MICHAEL DEBAKEY: THE REAL MAN BEHIND THE GENIUS".

- ^ Elias James Corey – Autobiography

Further reading

- Holland, Tom. "Persecution of Christians in the Middle East is a crime against humanity." The Guardian. Sunday 22 December 2013.