Dachau concentration camp: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 82.43.21.215 (talk) to last revision by Tom harrison (HG) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

The Dachau Concentration camp was not only heavily occupied, but was also heavily precautious and secure to ensure that no prisoners escaped. A ten-foot-wide (3 m) area of ground called “the neutral zone” was around each camp building. Its intention was to keep prisoners aware of where not to trespass. A four-foot-deep and eight-foot-broad (1.2 × 2.4 m) ditch lay behind the “neutral-zone.” The whole camp was surrounded by electrically charged barbed wire and a wall, which on the west side of the wire, contained a deep canal filled with water that connected with the river Amper.<ref name="Neuhäusler, Johann 1960. Page 14"/> |

The Dachau Concentration camp was not only heavily occupied, but was also heavily precautious and secure to ensure that no prisoners escaped. A ten-foot-wide (3 m) area of ground called “the neutral zone” was around each camp building. Its intention was to keep prisoners aware of where not to trespass. A four-foot-deep and eight-foot-broad (1.2 × 2.4 m) ditch lay behind the “neutral-zone.” The whole camp was surrounded by electrically charged barbed wire and a wall, which on the west side of the wire, contained a deep canal filled with water that connected with the river Amper.<ref name="Neuhäusler, Johann 1960. Page 14"/> |

||

The Lone Assassin |

|||

in dachau bunker was the lone assassin he was convicted of the assassination ofadolf hitler he was held in dachau bunker for 4 years before he was executed in 1994 during his time in dachau he was treated more like royalty as his cell was formed from two cells and was given more things to keep entertained the nazi had a plan that after they wn wn the war they would place him in a high court and have him executed but nly after the war was going wrong for the nazis they brought him outside of the bunker and executed him outside barracks x |

|||

==General overview== |

==General overview== |

||

Revision as of 07:32, 21 June 2013

| Dachau | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

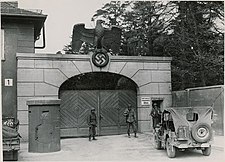

American troops guarding the main entrance to Dachau just after liberation, 1945 | |

Location of Dachau in Lower Bavaria | |

| Location | Upper Bavaria, Southern Germany |

| Operated by | German Schutzstaffel (SS), U.S. Army (after World War II) |

| Original use | Political prison |

| Operational | 1933–1960 |

| Inmates | Jews, Poles, Russians, Ukrainians, French, Yugoslavs, Czechs, Germans, Austrians, Lithuanians |

| Killed | 31,951 (reported) |

| Liberated by | United States, 29 April 1945 |

| Website | Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site |

Dachau concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager (KZ) Dachau, IPA: [ˈdaxaʊ]) was the first of the Nazi concentration camps opened in Germany. It is located on the grounds of an abandoned munitions factory near the medieval town of Dachau, about 16 km (9.9 mi) northwest of Munich in the state of Bavaria, in southern Germany.[1] Opened in 1933 by Heinrich Himmler, the purpose, as well as prisoner makeup, well in excess of its overall capacity, changed drastically over the next decade. It was finally liberated in 1945.

History

After the takeover of Bavaria on 9 March, Heinrich Himmler’s Munich police began to speak with the administration of an unused gunpowder and munitions factory and toured the future concentration camp site to see if it could be used for quartering protective-custody prisoners. The Concentration Camp at Dachau was opened Wednesday, 22 March 1933, bringing in about 200 prisoners from Stadelheim Prison in Munich and the Landsberg fortress (where Hitler wrote Mein Kampf during his imprisonment).[2] An announcement made by Heinrich Himmler in the Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten newspaper, stated that the concentration camp could hold up to 5,000 people and its purpose was to restore calm to Germany and that having a concentration camp was in the best interest of the people. After this announcement, the first concentration camp of the Third Reich was officially established.[3] It became the first regular concentration camp established by the coalition government of the National Socialist Party (Nazi Party) and the German Nationalist People's Party (dissolved on 6 July 1933). Heinrich Himmler, then Chief of Police of Munich, officially described the camp as "the first concentration camp for political prisoners."[1]

The main priority of the Dachau concentration camp was to serve as a munition factory along with forced labor working to expand the camp. The Dachau concentration camp was also the training center for SS guards and was a model for other concentration camps [4] The camp was about 990 feet wide and 1,980 feet long (300 × 600 m) in rectangular shape. The camp entrance was secured by a large iron gate that had the inscription: “Arbeit macht frei” (“Work makes you free”). As of 1938, the procedure for new arrivals occurred at the Schubraum, where prisoners were to hand over their clothing and possessions [5] The camp residence included an administration building that contained offices for the Gestapo trial commissioner, SS authorities, the camp leader and his deputies; administration offices that consisted of large storage rooms for the personal belongings of prisoners; the bunker; roll-call square where guards would inflict punishment on prisoners, especially those who tried to escape; the canteen where prisoners would serve SS men cigarettes and food; the museum containing plaster images of prisoners who suffered from bodily defects; the camp office; the library; the barracks; and the infirmary, which was staffed by prisoners who had previously held occupations such as physicians or army surgeons.[6]

While Heinrich Himmler mentioned that the camp could hold up to 5,000 people, after 1942, the number of prisoners continued to exceed 12,000 detainees.[7] Dachau originally held Communists, leading Socialists and other “enemies of the state” in 1933, but over time German Jews began to also arrive at the camp. Jews, however, were given the opportunity in the beginning years of imprisonment to receive permission to go overseas if they “voluntarily” gave their property to enhance Hitler’s public treasury.[7] Once Austria was annexed and Czechoslovakia was defeated, the citizens of both countries became the next victims of imprisonment at the concentration camp at Dachau. In 1940, Dachau became filled with Polish prisoners, which constituted for the majority of the prisoner population until Dachau was officially liberated.[8]

Prisoners were divided into categories. At first, categories were divided based on the type of crime one had committed, but eventually the meaning of the categories changed from the type of crime committed to the specific authority-type under whose command a man had been sent to camp.[9] Political prisoners who had been arrested by the Gestapo wore a red badge, professional criminals sent by the Criminal Courts wore a green badge, Cri-Po prisoners arrested by the criminal police wore a brown badge, work-shy and asocial people sent by the welfare authorities or the Gestapo wore a black badge, Jehovah’s Witnesses arrested by the Gestapo wore a violet badge, homosexuals sent by the criminal courts wore a pink badge, emigrants arrested by the Gestapo wore a blue badge, race polluters arrested by the criminal court or Gestapo had a black outline, second-termers arrested by the Gestapo wore a bar matching the color of their badge, idiots wore a white armband with the imprint “Blöd” meaning “idiot,” and Jews, whose incarceration in the Dachau concentration camp dramatically increased after Kristallnacht, wore a yellow badge, combined with another color.[10]

The Dachau Concentration camp was not only heavily occupied, but was also heavily precautious and secure to ensure that no prisoners escaped. A ten-foot-wide (3 m) area of ground called “the neutral zone” was around each camp building. Its intention was to keep prisoners aware of where not to trespass. A four-foot-deep and eight-foot-broad (1.2 × 2.4 m) ditch lay behind the “neutral-zone.” The whole camp was surrounded by electrically charged barbed wire and a wall, which on the west side of the wire, contained a deep canal filled with water that connected with the river Amper.[8]

The Lone Assassin in dachau bunker was the lone assassin he was convicted of the assassination ofadolf hitler he was held in dachau bunker for 4 years before he was executed in 1994 during his time in dachau he was treated more like royalty as his cell was formed from two cells and was given more things to keep entertained the nazi had a plan that after they wn wn the war they would place him in a high court and have him executed but nly after the war was going wrong for the nazis they brought him outside of the bunker and executed him outside barracks x

General overview

Dachau served as a prototype and model for the other Nazi concentration camps that followed. Almost every community in Germany had members taken away to these camps. Newspapers continually reported on "the removal of the enemies of the Reich to concentration camps", and as early as 1935 there were jingles warning: "Dear God, make me dumb, that I may not to Dachau come" ("Lieber Gott, mach mich dumm, damit ich nicht nach Dachau kumm").[11]

The camp's layout and building plans were developed by Kommandant Theodor Eicke and were applied to all later camps. He had a separate secure camp near the command center, which consisted of living quarters, administration, and army camps. Eicke himself became the chief inspector for all concentration camps, responsible for molding the others according to his model.[12]

The entrance gate to this concentration camp carries the phrase "Arbeit macht frei" (English translation: "Work makes free").

The camp was in use from 1933 to 1960, the first twelve years as an internment center of the Third Reich. From 1933 to 1938, the prisoners were mainly German nationals detained for political reasons. Subsequently, the camp was used for prisoners of all sorts, from every nation occupied by the forces of the Third Reich.[13] From 1945 through 1948, the camp was used as a prison for SS officers awaiting trial. After 1948, the German population expelled from Czechoslovakia were housed there and it was also a base of the United States. It was closed in 1960 and thereafter, at the insistence of ex-prisoners, various memorials began to be constructed there.[14]

Estimates of the demographic statistics vary but they are in the same general range. History may never know how many people were interned there or died there, due to periods of disruption. One source gives a general estimate of over 200,000 prisoners from more than 30 countries for the Third Reich's years, of whom two-thirds were political prisoners, including many Catholic priests, and nearly one-third were Jews. 25,613 prisoners are believed to have died in the camp and almost another 10,000 in its subcamps,[15] primarily from disease, malnutrition and suicide. In early 1945, there was a typhus epidemic in the camp due to influx from other camps causing overcrowding, followed by an evacuation, in which large numbers of the prisoners died. Toward the end of the war, death marches to and from the camp caused the deaths of large but unknown numbers of prisoners. Even after liberation, prisoners weakened beyond recovery continued to die.[citation needed]

Over its twelve years as a concentration camp, the Dachau administration recorded the intake of 206,206 prisoners and 31,951 deaths. Crematoria were constructed to dispose of the deceased. There is no evidence of mass murder within the camp, though visitors may walk through the buildings and see the ovens used to cremate bodies, which hid the evidence of many deaths. It is claimed that in 1942, more than 3,166 prisoners in weakened condition were transported to Hartheim Castle near Linz, and there they were executed by poison gas by reason of their unfitness.[13]

Together with the much larger Auschwitz concentration camp, Dachau has come to symbolize the Nazi concentration camps to many people. Konzentrationslager (KZ) Dachau lives in public memory as having been the second camp to be liberated by British or American forces. Accordingly, it was one of the first places where these camps were exposed to the rest of the world through firsthand journalist accounts and through newsreels.[citation needed]

Main camp

Purpose

Once the Nazis came to power they quickly moved to ruthlessly suppress all real and potential opposition. For example, between 1933 and 1945, the Sondergerichte which were "special courts" set up by the Nazi regime killed 12,000 Germans.[16] Especially during the first years of their existence these courts "had a strong deterrent effect" against opposition to the Nazis; the German public was intimidated through "arbitrary psychological terror".[17]

Use of the word concentration comes from the idea of concentrating a group of people who are in some way undesirable in one place, where they can be watched by those who incarcerated them. Concentration camps had been used by the U.S. against native Americans and Japanese Americans, the British during the Boer Wars, and others. The term originated in the "reconcentration camps" set up in Cuba by General Valeriano Weyler in 1897.

Dachau was opened in March 1933.[1] The press statement given at the opening stated:

On Wednesday the first concentration camp is to be opened in Dachau with an accommodation for 5000 people. 'All Communists and—where necessary—Reichsbanner and Social Democratic functionaries who endanger state security are to be concentrated here, as in the long run it is not possible to keep individual functionaries in the state prisons without overburdening these prisons, and on the other hand these people cannot be released because attempts have shown that they persist in their efforts to agitate and organize as soon as they are released.[1]

Dachau was the first regular concentration camp established by the coalition government of National Socialist Party (Nazi Party) and the German National People's Party (dissolved on 6 July 1933). Heinrich Himmler, Chief of Police of Munich, officially described the camp as "the first concentration camp for political prisoners."[1]

Between the years 1933 and 1945, more than 3.5 million Germans would be forced to spend time in these concentration camps or prison for political reasons,[18][19][20] and approximately 77,000 Germans were killed for one or another form of resistance by Special Courts, courts-martial, and the civil justice system. Many of these Germans had served in government, the military, or in civil positions, which enabled them to engage in subversion and conspiracy against the Nazis.[21]

Organization

The camp was divided into two sections: the camp area and the crematorium. The camp area consisted of 69 barracks, including one for clergy imprisoned for opposing the Nazi regime and one reserved for medical experiments. The courtyard between the prison and the central kitchen was used for the summary execution of prisoners. The camp was surrounded by an electrified barbed-wire gate, a ditch, and a wall with seven guard towers.[12]

In early 1937, the SS, using prisoner labor, initiated construction of a large complex of buildings on the grounds of the original camp. The construction was officially completed in mid-August 1938 and the camp remained essentially unchanged and in operation until 1945. Dachau thus was the longest running concentration camp of the Third Reich. The area in Dachau included other SS facilities beside the concentration camp—a leader school[citation needed] of the economic and civil service, the medical school[citation needed] of the SS, etc. The camp at that time was called a "protective custody camp,"[citation needed] and occupied less than half of the area of the entire complex.

Demographics

The camp was originally designed for holding German political prisoners and Jews, but in 1935 it also began to hold ordinary criminals. During the war it came to also include other nationalities such as French, in 1940 Poles, 1941 people from the Balkans, and in 1942 Russians.[22]

Before the war the biggest groups of inmates were Germans, Austrians, and Jews. During the War the biggest groups were, in order of size; Poles, Russians, French, Yugoslavs, Jews, and Czechs.[22]

Inside the camp there was a sharp division between the two groups of prisoners; those who were there for political reasons and therefore wore a red tag, and the criminals, who wore a green tag.[22]

The average number of Germans in the camp during the war was 3000. Just before the liberation many German prisoners were evacuated, but 2000 of these Germans died during the evacuation transport. Evacuated prisoners included famous political and religious hostages held in Dachau,[22] such as Martin Niemöller, Kurt von Schuschnigg, Édouard Daladier, Léon Blum, Franz Halder and Hjalmar Schacht.

Though at the time of liberation the death rate had peaked at 200 per day, after the liberation by U.S. forces the rate eventually fell to between 50 and 80 deaths per day. The cause of these deaths was, besides the murderous SS policies, typhus epidemics and starvation which claimed thousands of lives. The number of inmates had peaked in 1944 with transports from evacuated camps in the east (such as Auschwitz) and the resulting overcrowding led to an increase in the death rate.[22]

Dachau also served as the central camp for Christian religious prisoners. At least 3,000 Catholic priests, deacons, and bishops were imprisoned there.[23]

In August 1944 a women's camp opened inside Dachau. In the last months of the war, the conditions at Dachau became even worse. As Allied forces advanced toward Germany, the Germans began to move prisoners in concentration camps near the front to more centrally located camps. They hoped to prevent the liberation of large numbers of prisoners. Transports from the evacuated camps arrived continuously at Dachau. After days of travel with little or no food or water, the prisoners arrived weak and exhausted, often near death. Typhus epidemics became a serious problem as a result of overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, insufficient provisions, and the weakened state of the prisoners.

Owing to continual new transportations from the front, the camp was constantly overcrowded and the hygiene conditions were beneath human dignity. Starting from the end of 1944 up to the day of liberation, 15,000 people died, about half of all victims in KZ Dachau. Five hundred Soviet POWs were executed by firing squad. Its first shipment of women came from Auschwitz Birkenau.

Staff

Nineteen female guards served at Dachau, most of them until liberation.[24] Sources[who?] show sixteen of the nineteen women guarding the camp were; Fanny Baur, Leopoldine Bittermann, Ernestine Brenner, Anna Buck, Rosa Dolaschko, Maria Eder, Rosa Grassmann, Betty Hanneschaleger, Ruth Elfriede Hildner, Josefa Keller, Berta Kimplinger, Lieselotte Klaudat, Theresia Kopp, Rosalie Leimboeck, and Thea Miesl. Women guards were also at the Augsburg Michelwerke, Burgau, Kaufering, Mühldorf, and Munich Agfa Camera Werke subcamps. In mid-April 1945, many female subcamps at Kaufering, Augsburg and Munich were closed, and the SS stationed the women at Dachau. It is reported that female SS guards gave prisoners guns before liberation to save them from postwar prosecution.[citation needed]Wilhelm Ruppert is named as being in charge of the killings of several prisoners.

Several Norwegians worked as guards at the Dachau camp.[25]

Satellite camps and sub-camps

Satellite camps under the authority of Dachau were established in the summer and fall of 1944 near armaments factories throughout southern Germany to increase war production. Dachau alone had more than 30 large subcamps in which over 30,000 prisoners worked almost exclusively on armaments.[26]

Overall, the Dachau concentration camp system included 123 sub-camps and Kommandos which were set up in 1943 when factories were built near the main camp to make use of forced labor of the Dachau prisoners. The sub-camps were liberated by various divisions of the American army that unexpectedly came across them on their way to capture Munich. American soldiers in the 63rd Infantry Division liberated seven of the eleven Kaufering sub-camps on 29 and 30 April 1945. The 63rd Infantry Division was recognized as a liberating unit by the U.S. Army’s Center of Military History and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2000.[27]

Out of the 123 sub-camps, eleven of them were called Kaufering, distinguished by a number at the end of each. All Kaufering sub-camps were set up to specifically build three underground factories (Allied bombing raids made it necessary for them to be underground) for a project called Ringeltaube, which planned to be the location in which the German jet fighter plane, Messerschmitt Me 262, was to be built. In the last days of war, in April 1945, the Kaufering camps were evacuated and around 15,000 prisoners were sent up to the main Dachau camp. Approximately 14,500 prisoners in the eleven Kaufering camps died of hunger, cold weather, overwork, and typhus.[27]

Liberation

Main camp

This section needs additional citations for verification. (July 2012) |

As the opposition began to advance on Nazi Germany, the SS began to evacuate the first concentration camps in summer 1944.[28] Thousands of prisoners were murdered before the evacuation due to being ill or unable to walk. At the end of 1944, the overcrowding of camps began to take its toll on the prisoners. The hygienic conditions and the supplies of food rations became disastrous. In November a typhus fever epidemic broke out that took thousands of lives.[29]

In the second phase of the evacuation, in April 1945, Himmler gave direct evacuation routes for remaining camps. Prisoners that were from the northern part of Germany were to be directed to the Baltic and North Sea coasts to be drowned. The prisoners from the southern part were to be gathered in the Alps, which was the location in which the SS wanted to resist the Allies (p. 196). On 28 April 1945, an armed revolt took place in the town of Dachau. Both former and escaped concentration camp prisoners, and a renegade Volkssturm (civilian militia) company took part. At about 8:30 AM the rebels occupied the Town Hall. The advanced forces of the SS gruesomely suppressed the revolt within a few hours.[30]

Being fully aware that Germany was about to be defeated in World War II, the SS invested its time in removing evidence of the crimes they committed in the concentration camps. The SS began destroying incriminating evidence in April 1945 and planned on murdering the prisoners using codenames “Wolke A I” (Cloud A I) and “Wolkenbrand” (Cloud fire). However, these plans never ended up being carried out. In mid-April, plans to evacuate the camp started by sending prisoners toward Tyrol. On April 26, over 10,000 prisoners were forced to leave the Dachau concentration camp on foot, in trains, or in trucks. The largest group of some 7,000 prisoners was driven southward on a foot-march lasting several days. More than 1,000 prisoners did not survive this march. The evacuation transports cost many thousands of prisoners their lives.[31] On 26 April 1945 prisoner Karl Riemer fled the Dachau concentration camp to get help from American troops and on April 28 Victor Maurer, a representative of the International Red Cross, negotiated an agreement to surrender the camp to U.S. troops. That night a secretly formed International Prisoners Committee took over the control of the camp. On 29 April 1945 the Dachau concentration camp was officially liberated by U.S. Army troops.[32]

Satellite camps

During the liberation of the sub-camps surrounding Dachau (which happened on the same day as the main camp's surrender on 29 April) the advance scouts of the US Army's 522nd Field Artillery Battalion, a Nisei-manned segregated Japanese-American Allied military unit, liberated the 3,000 prisoners of the "Kaufering IV Hurlach"[33] slave labor camp.[34] Perisco describes an Office of Strategic Services (OSS) team (code name LUXE) leading Army Intelligence to a "Camp IV" on 29 April. "they found the camp afire and a stack of some four hundred bodies burning... American soldiers then went into Landsberg and rounded up all the male civilians they could find and marched them out to the camp. The former commandant was forced to lie amidst a pile of corpses. The male population of Landsberg was then ordered to walk by, and ordered to spit on the commandant as they passed. The commandant was then turned over to a group of liberated camp survivors."[35]

Killing of camp guards

The American troops killed some of the camp guards after they had surrendered. The number of guards killed is disputed as some Germans were killed in combat, some were shot while attempting to surrender, and others were killed after their surrender was accepted. In 1989 Brigadier General Felix L. Sparks, the Colonel in command of a battalion that captured the camp in 1945, stated:

The total number of German guards killed at Dachau during that day most certainly does not exceed fifty, with thirty probably being a more accurate figure. The regimental records of the 157th Infantry Regiment (United States) for that date indicate that over a thousand German prisoners were brought to the regimental collecting point. Since my task force was leading the regimental attack, almost all the prisoners were taken by the task force, including several hundred from Dachau.[36]

The "American Army Investigation of Alleged Mistreatment of German Guards at Dachau" found that about 15 Germans were killed (with another 4 or 5 wounded) after their surrender had been accepted. Two other reports collated years after the incident put the figure between 122 and 520 Germans killed after their surrender had been accepted.[citation needed]

As a result of the American Army investigation court-martial, charges were drawn up against Sparks and several other men under his command but, as General George S. Patton (the then recently appointed military governor of Bavaria) chose to dismiss the charges, the witnesses to the killings were never cross-examined in court and no one was found guilty.[36] Many guards were also killed by the liberated prisoners, which made the issue more complex. Lee Miller visited the camp just after liberation, and photographed several guards who died at the prisoners' hands.

American troops also forced local citizens to the camp to see for themselves the conditions there and to help clean the facilities. Many local residents were shocked about the experience and claimed no knowledge of the activities at the camp.[citation needed] Photographs of this event are stored at the US Holocaust Memorial Museum.[37]

Post-liberation Easter

May 6 (23 April on the Orthodox calendar) was the day of Pascha, Orthodox Easter. In a cell block used by Catholic priests to say daily Mass, several Greek, Serbian and Russian priests and one Serbian deacon, wearing makeshift vestments made from towels of the SS guard, gathered with several hundred Greek, Serbian and Russian prisoners to celebrate the Paschal Vigil. A prisoner named Rahr described the scene:[38]

In the entire history of the Orthodox Church there has probably never been an Easter service like the one at Dachau in 1945. Greek and Serbian priests together with a Serbian deacon adorned the make-shift 'vestments' over their blue and gray-striped prisoners' uniforms. Then they began to chant, changing from Greek to Slavic, and then back again to Greek. The Easter Canon, the Easter Sticheras—everything was recited from memory. The Gospel—In the beginning was the Word—also from memory. And finally, the Homily of Saint John—also from memory. A young Greek monk from the Holy Mountain stood up in front of us and recited it with such infectious enthusiasm that we shall never forget him as long as we live. Saint John Chrysostomos himself seemed to speak through him to us and to the rest of the world as well!

There is a Russian Orthodox chapel at the camp today, and it is well known for its icon of Christ leading the prisoners out of the camp gates.

The U.S. 7th Army's version of the events of the Dachau Liberation is available in Report of Operations of the Seventh United States Army, Vol. 3, page 382.

After liberation

After liberation, the camp was used by the US Army as an internment camp. It was also the site of the Dachau Trials, a site chosen for its symbolism. In 1948 the Bavarian government established housing for refugees on the site, and this remained for many years.[39] The Kaserne quarters and other buildings used by the guards and trainee guards served as an American military post for many years. It had its own elementary school: Dachau American Elementary School, a part of the Department of Defense dependent school system.

In popular culture

Onscreen

- The Dachau Massacre figures prominently in the back story of Teddy Daniels, the protagonist of Dennis Lehane's psychological mystery-thriller Shutter Island, (later adapted into a film by Martin Scorsese, starring Leonardo DiCaprio). Among other memories, Daniels is haunted by his own recollections of the massacre and taking part in the executions after seeing piles of prisoners' bodies.

- Dachau is depicted as the setting for The Twilight Zone episode "Deaths-Head Revisited", in which a former SS captain revisits the place he once worked in and the ghosts of the men who died there.

In music

- "Dachau Blues", a song by psychedelic blues singer Captain Beefheart from the album Trout Mask Replica, contains several references to the camp and to the Holocaust.

- The British band The Style Council released a song called "Ghosts of Dachau" in memory of those who died at Dachau, after a visit by lead singer Paul Weller to a concentration camp.

In theatre

- Dachau is the concentration camp in which two homosexual prisoners desperately try to hold on to their humanity in the 1979 play Bent by Martin Sherman.

The memorial site

Between 1945 and 1948 when the camp was handed over to the Bavarian authorities, many accused war criminals and members of the SS were imprisoned at the camp.

Owing to the severe refugee crisis mainly caused by the expulsions of ethnic Germans, the camp was from late 1948 used to house 2000 Germans from Czechoslovakia (mainly from the Sudetenland). This settlement was called Dachau-East, and remained until the mid-1960s.[40] During this time, former prisoners banded together to erect a memorial on the site of the camp, finding it unbelievable that there were still people (refugees) living in the former camp.

The display, which was reworked in 2003, takes the visitor through the path of new arrivals to the camp. Special presentations of some of the notable prisoners are also provided. Two of the barracks have been rebuilt and one shows a cross-section of the entire history of the camp, since the original barracks had to be torn down due to their poor condition when the memorial was built. The other 32 barracks are indicated by concrete foundations.

The memorial includes four chapels for the various religions represented among the prisoners.

The local government resisted designating the complete site a memorial. The former SS barracks adjacent to the camp are now occupied by the Bavarian Bereitschaftspolizei (rapid response police unit).[41]

List of personnel

Commanders

- SS-Standartenführer Hilmar Wäckerle (22 March 1933 - 26 June 1933)

- SS-Gruppenführer Theodor Eicke (26 June 1933 - 4 July 1934)

- SS-Oberführer Alexander Reiner (4 July 1934 - 22 October 1934)

- SS-Brigadeführer Berthold Maack (22 October 1934 - 12 January 1935)

- SS-Oberführer Heinrich Deubel (12 January 1935 - 31 March 1936)

- SS-Oberführer Hans Loritz (31 March 1936 - 7 January 1939)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Alex Piorkowski (7 January 1939 - 2 January 1942)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Martin Weiß (3 January 1942 - 30 September 1943)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer Eduard Weiter (30 September 1943 - 26 April 1945)

- SS-Obersturmbannführer Martin Weiß (26 April 1945 - 28 April 1945)

- SS-Untersturmführer Johannes Otto (28 April 1945)

- SS-Untersturmführer Heinrich Wicker (28 April 1945 - 29 April 1945)

Other staff

- Adolf Eichmann (29 January 1934 - October 1934)[42] (Eichmann claimed that his unit had nothing to do with the concentration camp)[43]

- Rudolf Höss (1934–1938)[44]

- Max Kögel (1937–1938)

- Gerhard Freiherr von Almey, a SS-Obbergruppenführer, half-brother of Ludolf von Alvensleben. Executed in 1955, in Moscou.

- Johannes Heesters[45] (visited the camp and entertained the SS-officers, was also given/giving tours)[46]

SS and civilian doctors

- SS-Untersturmführer - Dr. Hans Eisele - (13 March 1912 – 1967) - Escaped to Egypt

- SS-Obersturmführer - Dr. Fritz Hintermayer - (28 Oct 1911 - 29 May 1946) - Executed by the Allies

- Dr. Ernst Holzlöhner - (Committed Suicide)

- SS-Hauptsturmführer - Dr. Fridolin Karl Puhr - (30 April 1913 - ?) - Sentenced to death, later commuted to 10-years imprisonment

- SS-Untersturmführer Dr. Sigmund Rascher - (12 February 1909-26 April 1945) - Executed by the SS

- Dr. Claus Schilling - (25 July 1871-28.5.1946) - Executed by the Allies

- SS Sturmbannführer - Dr. Horst Schumann - (11 May 1906-5 May 1983) - Escaped to Ghana, later extradited to West Germany

- SS Obersturmführer - Dr. Helmuth Vetter - (21 March 1910-2 February 1949) - Executed by the Allies

- SS Sturmbannführer - Dr. Wilhelm Witteler - (20 April 1909-?) - Sentenced to death, later commuted to 20-years imprisonment

- SS Sturmbannführer - Dr. Waldemar Wolter - (19 May 1908-28 May 1947) - Executed by the Allies

List of notable prisoners

Clergy

Dachau had a special "priest block." Of the 2720 priests (among them 2579 Catholic) held in Dachau, 1034 did not survive the camp. The majority were Polish (1780), of whom 868 died in Dachau.

- Patriarch Gavrilo V of the Serbian Orthodox Church, imprisoned in Dachau from September to December 1944

- a number of the Polish 108 Martyrs of World War II:

- Father Jean Bernard (1907–1994), Roman Catholic priest from Luxembourg who was imprisoned from May 1941 to August 1942. He wrote the book Pfarrerblock 25487 about his experiences in Dachau

- Blessed Titus Brandsma, Dutch Carmelite priest and professor of philosophy, died 26 July 1942

- Norbert Čapek (1870–1942) founder of the Unitarian Church in the Czech Republic

- Blessed Stefan Wincenty Frelichowski, Polish Roman Catholic priest, died 23 February 1945

- August Froehlich, German Roman Catholic priest, he protected the rights of the German Catholics and the maltreatment of Polish forced labourers

- Hilary Paweł Januszewski

- Ignacy Jeż Catholic Bishop

- Joseph Kentenich, founder of the Schoenstatt Movement, spent three and a half years in Dachau

- Bishop Jan Maria Michał Kowalski, the first Minister Generalis (Minister General) of the order of the Mariavites. He perished on 18 May 1942, in a gas chamber in Schloss Hartheim.

- Adam Kozlowiecki, Polish Cardinal

- Max Lackmann, Lutheran pastor and founder of League for Evangelical-Catholic Reunion.

- Blessed Karl Leisner, in Dachau since 14 December 1941, freed 4 May 1945, but died on 12 August from tuberculosis contracted in the camp

- Josef Lenzel, German Roman Catholic priest, he helped of the Polish forced labourers

- Bernhard Lichtenberg - German Roman Catholic priest, was sent to Dachau but died on his way there in 1943

- Martin Niemöller, imprisoned in 1941, freed 4 May 1945

- Nikolai Velimirović, bishop of the Serbian Orthodox Church and an influential theological writer, venerated as saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

- Lawrence Wnuk

- Nanne Zwiep, Pastor of the Dutch Reformed Church in Enschede, spoke out from the pulpit against Nazis and their treatment of Dutch Citizens and anti-Semitism, arrested 20 April 1942, died in Dachau of exhaustion and malnutrition 24 November 1942

More than two dozen members of the Religious Society of Friends (known as Quakers) were interned at Dachau. They may or may not have been considered clergy by the Nazis, as all Quakers perform services which in other Protestant denominations are considered the province of clergy. Over a dozen of them were murdered there.

Communists

- Alfred Andersch, held 6 months in 1933

- Hans Beimler, imprisoned but escaped. Died in the Spanish Civil War.

- Emil Carlebach (Jewish), in Dachau since 1937, sent to Buchenwald concentration camp in 1938

- Alfred Haag, In Dachau from 1935 to 1939, when moved to Mauthausen

- Adolf Maislinger

- Oskar Müller, in Dachau from 1939, freed 1945

- Walter Vielhauer

- Nikolaos Zachariadis (Greek), from November 1941 to May 1945

Jewish

- Hinko Bauer, notable Croatian architect

- Bruno Bettelheim, imprisoned in 1938, freed in 1939; left Germany

- Jakob Ehrlich, Member of Vienna's City Council (Rat der Stadt Wien), died in Dachau 17 May 1938

- Viktor Frankl, neurologist and psychiatrist from Vienna, Austria

- Yanek (Jack) Gruener, a Polish boy whose story is told in Prisoner B-3087[47]

- Ludwig Kahn, German World War I Veteran and Entrepreneur from 29 Karls Street, Weilheim, Bavaria imprisoned 10 November 1938, freed 19 December 1938

- Hans Litten, anti-Nazi lawyer, died in 1938 by apparent suicide

- George Maduro, Dutch law student and cavalry officer posthumously awarded the medal of Knight 4th-class of the Military Order of William.

- Aaron Miller, rabbi, chazzan, mohel

- Henry Morgentaler, also survived the Łódź Ghetto, later emigrated to Canada and became central to the abortion-rights movement there

- Alfred Müller, known Croatian entrepreneur from Zagreb

- Benzion Miller, born at the camp, son of Aaron Miller

- Sol Rosenberg, participated in the Warsaw Ghetto uprising; sent to Dachau; liberated from the camp in 1945; relocated to the United States

- Moshe Sanbar, Governor of the Bank of Israel

- Vladek Spiegelman, a survivor whose story was portrayed in the book Maus by son Art Spiegelman

Politicians

- Léon Blum - briefly, having been evacuated from Buchenwald concentration camp

- Jan Buzek, murdered in November 1940

- Theodor Duesterberg, briefly imprisoned in 1934

- Leopold Figl, arrested 1938, released 8 May 1943

- Andrej Gosar, Slovenian politician and political theorist, arrested in 1944

- Karl Haushofer

- Miklós Horthy, Jr.

- Alois Hundhammer, arrested 21 June 1933, freed 6 July 1933

- Miklós Kállay

- Franz Olah, arrested in 1938 and transported on the first train to bring Austrian prisoners to Dachau.[48]

- Hjalmar Schacht, arrested 1944, released April 1945

- Richard Schmitz

- Kurt Schumacher, in Dachau since July 1935, sent to Flossenbürg concentration camp in 1939, returned to Dachau in 1940, released due to extreme illness 16 March 1943

- Kurt Schuschnigg, the last fascist chancellor of Austria before the Austrian Nazi Party was installed by Hitler, shortly before the Anschluss

- Stefan Starzyński, the President of Warsaw, probably murdered in Dachau in 1943

- Petr Zenkl, Czech national socialist politician

Resistance fighters

- Yolande Beekman, Special Operations Executive Agent, murdered 13 September 1944

- Georges Charpak, who in 1992 received the Nobel Prize in Physics

- Madeleine Damerment, Special Operations Executive Agent, murdered 13 September 1944

- Charles Delestraint, French General and leader of French resistance; executed by Gestapo in 1945

- Georg Elser, who tried to assassinate Hitler in 1939, murdered 9 April 1945

- Arthur Haulot

- Noor Inayat Khan, the George's Cross awardee of Indian origin who served as a clandestine radio operator for the Special Operations Executive in Paris, murdered 13 September 1944 when she and her SOE colleagues were shot in the back of the head and cremated

- Kurt Nehrling, murdered in 1943

- Eliane Plewman, Special Operations Executive Agent, murdered 13 September 1944

- Enzo Sereni, Jewish, son of King Victor Emmanuele's personal physician. Kibbutz Netzer Sereni in Israel is named after him. Parachuted into Nazi-occupied Italy, captured by the Germans and executed in November 1944

- Jean ("Johnny") Voste, the one documented black prisoner, was a Belgian resistance fighter from the Congo; he was arrested in 1942 for alleged sabotage, and was one of the survivors of Dachau[49][50][51]

Royalty

- Antonia, Crown Princess of Bavaria

- Albrecht, Duke of Bavaria

- Princess Irmingard of Bavaria

- Franz, Duke of Bavaria

- Grand Duchess Kira Kirillovna of Russia

- Prince Louis Ferdinand of Prussia

- Prince Max, Duke in Bavaria

- Philipp, Landgrave of Hesse

- Franz Wittelsbach, Prinz von Bayern

- Maximilian, Duke of Hohenberg

- Prince Ernst von Hohenberg

- Princess Sophie of Hohenberg

Scientists

Among many others, 183 professors and lower university staff from Kraków universities, arrested on 6 November 1939 during Sonderaktion Krakau.

Writers

- Fran Albreht, Slovenian poet

- Robert Antelme, French writer

- Raoul Auernheimer, writer, in Dachau 4 months

- Tadeusz Borowski, writer, survived, but committed suicide in 1951

- Adolf Fierla, Polish poet

- Viktor Frankl, an Austrian psychiatrist and writer

- Fritz Gerlich, a German journalist

- Stanisław Grzesiuk, Polish writer, poet and singer, in Dachau from 4 April 1940, later transferred to Mauthausen-Gusen complex

- Heinrich Eduard Jacob, German writer, in Dachau 6 months in 1938, transferred to Buchenwald

- Stefan Kieniewicz, Polish historian

- Juš Kozak, Slovenian playwright

- Friedrich Bernhard Marby, German occult writer

- Gustaw Morcinek, Polish writer

- Boris Pahor, Slovenian writer

- Karol Piegza, Polish writer, teacher and folklorist

- Gustaw Przeczek, Polish writer and teacher

- Friedrich Reck-Malleczewen, German writer[citation needed]

- Franz Roh, German art critic and art historian, for a few months in 1933

- Jura Soyfer, writer, in Dachau 6 months in 1938, transferred to Buchenwald

- Adam Wawrosz, Polish poet and writer

- Stanislaw Wygodzki, Polish writer

- Stevo Žigon (number: 61185), Serbian actor, theatre director, and writer, in Dachau from December 1943 to May 1945

Others

- Titus Brandsma, Dutch priest, philosopher and former rector of Nimwegen University

- Jan Ertmański, Polish boxer who competed in the 1924 Summer Olympics

- Alexander von Falkenhausen, German general who resisted Hitler

- Brother Theodore, comedian

- Franz Halder, former Chief of Army General Staff

- Bruno Franz Kaulbach, Austrian lawyer

- Zoran Mušič, Slovenian painter

- Alexander Papagos, future Prime Minister of Greece

- Ernest Peterlin, Slovenian military officer

- Tullio Tamburini, Italian police chief

- Fritz Thyssen, businessman and early supporter of Hitler, later an opponent

- Bogislaw von Bonin, Wehrmacht officer, opponent

- Morris Weinrib, father of Rush singer, bassist, keyboardist Geddy Lee

Gallery

-

The camp courtyard

-

Memorial to the victims of Dachau (October 2007)

-

Sign on the gravel road leading to the entrance

-

The Crematorium

-

New crematorium (picture taken on October 2007)

-

Original crematorium (picture taken on October 2007)

-

Crematorium at Dachau

-

The sign outside the building Crematorium says in German: "Think about how we died here"

-

Protestant Church of Reconciliation (June 2005)

-

Catholic Mortal Agony of Christ chapel (June 2005)

-

Jewish Memorial (June 2005)

-

Tower (June 2005)

-

The Perimeter Fence

-

Marker where barracks building #9 stood (June 2005)

-

View of roll-call area from one of the buildings (June 2005)

-

Prisoner bunks (June 2005)

-

Prisoner bunks (June 2005)

-

Triple bunks in the barracks

-

Prisoner sinks (June 2005)

-

Prisoner toilets (June 2005)

-

The entrance and the northern part of the "Bunker" (September 2007)

-

The east wing of the "Bunker" (camp prison), normally closed to visitors

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e "Ein Konzentrationslager für politische Gefangene In der Nähe von Dachau". Münchner Neueste Nachrichten ("The Munich Latest News") (in German). The Holocaust History Project. 21 March 1933.

The Munich Chief of Police, Himmler, has issued the following press announcement: On Wednesday the first concentration camp is to be opened in Dachau with an accommodation for 5000 persons. 'All Communists and—where necessary—Reichsbanner and Social Democratic functionaries who endanger state security are to be concentrated here, as in the long run it is not possible to keep individual functionaries in the state prisons without overburdening these prisons, and on the other hand these people cannot be released because attempts have shown that they persist in their efforts to agitate and organise as soon as they are released.'

Cite error: The named reference "MNN" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page). - ^ Marcuse, Harold. Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2001. Print. Page 21

- ^ Neuhäusler, Johann. What Was It like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?: An Attempt to Come Closer to the Truth. Munich: Manz A.G., 1960. Print. Page 7

- ^ ="Dachau Liberated." History.com. A&E Television Networks, n.d. Web. 27 March 2013.

- ^ The Dachau Concentration Camp, 1933 to 1945: Text and Photo Documents from the Exhibition, with CD. Dachau: Comité International De Dachau, 2005. Print. page 61

- ^ Neuhäusler, Johann. What Was It like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?: An Attempt to Come Closer to the Truth. Munich: Manz A.G., 1960. Print. Page 9-11

- ^ a b Neuhäusler, Johann. What Was It like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?: An Attempt to Come Closer to the Truth. Munich: Manz A.G., 1960. Print. Page 13

- ^ a b Neuhäusler, Johann. What Was It like in the Concentration Camp at Dachau?: An Attempt to Come Closer to the Truth. Munich: Manz A.G., 1960. Print. Page 14

- ^ Neurath, Paul Martin, Christian Fleck, and Nico Stehr. The Society of Terror: Inside the Dachau and Buchenwald Concentration Camps. Boulder, CO: Paradigm, 2005. Print. Page 53

- ^ Neurath, Paul Martin, Christian Fleck, and Nico Stehr. The Society of Terror: Inside the Dachau and Buchenwald Concentration Camps. Boulder, CO: Paradigm, 2005. Print. Page 54-69

- ^ Janowitz, Morris (September, 1946). "German Reactions to Nazi Atrocities". The American Journal of Sociology. 52 (2). The University of Chicago Press: 141–146. doi:10.1086/219961. JSTOR 2770938.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) The word "dumm" here means "stupid" rather than "mute". - ^ a b "Dachau". Holocaust Encyclopedia. Washington, D.C.: United States Holjkihjiohoocaust Memorial Museum. 2009.

- ^ a b Edkins 2003, p. 137

- ^ Edkins 2003, p. 138

- ^ Zámečník, Stanislav; Paton, Derek B. (Translator) (2004). That Was Dachau 1933-1945. Paris: Fondation internationale de Dachau; Cherche Midi. pp. 377, 379.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - ^ Peter Hoffmann "The History of the German Resistance, 1933-1945" p. xiii

- ^ Andrew Szanajda "The restoration of justice in postwar Hesse, 1945-1949" p. 25 "In practice, it signified intimidating the public through arbitrary psychological terror, operating like the courts of the Inquisition." "The Sondergerichte had a strong deterrent effect during the first years of their operation, since their rapid and severe sentencing was feared."

- ^ Henry Maitles NEVER AGAIN!: A review of David Goldhagen, Hitlers Willing Executioners: Ordinary Germans and the Holocaust", further referenced to G Almond, "The German Resistance Movement", Current History 10 (1946), pp409–527.

- ^ David Clay, "Contending with Hitler: Varieties of German Resistance in the Third Reich", p.122 (1994) ISBN 0-521-41459-8

- ^ Otis C. Mitchell, "Hitler's Nazi State: The Years of Dictatorial Rule, 1934-1945" (1988), p.217

- ^ Peter Hoffmann "The History of the German Resistance, 1933–1945" p. xiii

- ^ a b c d e 7th Army, U.S. (1945). Dachau. University of Wisconsin Digital Collection.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Particularly notable among the Christian residents are Karl Leisner (Catholic priest ordained while in the camp, beatified by Pope John Paul II in 1996) and Martin Niemöller (Protestant theologian and Nazi resistance leader).

- ^ THE CAMP WOMEN, The Female Auxiliaries who Assisted the SS in Running the Nazi Concentration Camp System by Daniel Patrick Brown.

- ^ "(translation of title: — Norwegian guards worked in Hitler's concentration camps)"''- Norske vakter jobbet i Hitlers konsentrasjonsleire''"". Vg.no. 2010-01-01. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/en/article.php?ModuleId=10005214

- ^ a b Liberation of Kaufering IV Sub-camp of Dachau near Hurlach. N.p., n.d. Web. 27 March 2013. <http://www.scrapbookpages.com/DachauScrapbook/DachauLiberation/KauferingIVLiberation.html>

- ^ =The Dachau Concentration Camp, 1933 to 1945: Text and Photo Documents from the Exhibition, with CD. Dachau: Comité International De Dachau, 2005. Print. Page 194

- ^ The Dachau Concentration Camp, 1933 to 1945: Text and Photo Documents from the Exhibition, with CD. Dachau: Comité International De Dachau, 2005. Print. Page 197

- ^ The Dachau Concentration Camp, 1933 to 1945: Text and Photo Documents from the Exhibition, with CD. Dachau: Comité International De Dachau, 2005. Print. Page 199

- ^ The Dachau Concentration Camp, 1933 to 1945: Text and Photo Documents from the Exhibition, with CD. Dachau: Comité International De Dachau, 2005. Print. Page 200

- ^ The Dachau Concentration Camp, 1933 to 1945: Text and Photo Documents from the Exhibition, with CD. Dachau: Comité International De Dachau, 2005. Print. Page 201

- ^ "Kaufering IV - Hurlach - Schwabmunchen". Kaufering.com. 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "Central Europe Campaign - (522nd Field Artillery Battalion)". Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ^ Joseph E Persico (1979). Piercing the Reich. Viking Press. p. 306. ISBN 0-670-55490-1.

- ^ a b Albert Panebianco (ed). Dachau its liberation 157th Infantry Association, Felix L. Sparks, Secretary 15 June 1989. (backup site)

- ^ "Photograph". Ushmm.org. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ "Gleb Alexandrovitch Rahr - Prisoner R (Russian) - Pascha (Easter) in Dachau". Orthodoxytoday.org. Retrieved 2012-07-06.

- ^ Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site (pedagogical information) Template:De icon

- ^ Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001 Harold Marcuse

- ^ Sven Felix Kellerhoff (2002-10-21). "Neue Museumskonzepte für die Konzentrationslager". WELT ONLINE (in German). Axel Springer AG. Retrieved 2008-06-02.

. . . die SS-Kasernen neben dem KZ Dachau wurden zuerst (bis 1974) von der US-Armee bezogen. Seither nutzt sie die VI. Bayerische Bereitschaftspolizei. (. . . the SS barracks adjacent to the Dachau concentration camp were at first occupied by the US Army (until 1974) . Since then they have been used by the Sixth Rapid Response Unit of the Bavarian Police.)

- ^ "people/e/eichmann.adolf/transcripts/Sessions/Session-013-04". transcript from the 1961 Eichmann trial. Shofar FTP archive and the Nizkor project. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ "people/e/eichmann.adolf/transcripts/Sessions/Session-075-05". transcript from the 1961 Eichmann trial. Shofar FTP archive and the Nizkor project. Retrieved 2009-02-02.

- ^ "The Trial of German Major War Criminals Sitting at Nuremberg, Germany 4th April to 15th April, 1946: One Hundred and Eighth Day: Monday, 15th April, 1946 (Part 1 of 10)". the Nizkor Project. 1991–2009. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ Klee, Kulturlexikon, S. 227.

- ^ Klee, Kulturlexikon, S. 232.

- ^ Alan Gratz, "Prisoner B-3087", pp.1240-245 (2013) ISBN 978-0-545-45901-3

- ^ Green, William (2009-09-04). "Franz Olah dies aged 99". austriantimes.at. Canterbury, Kent, U.K.: AN News and Pictures. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- ^ "The Only Black Prisoner at Dachau Prepares Food With Another Survivor". Jewish Virtual Library. May 1945. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Photograph: "Two survivors prepare food outside the barracks. The man on the right, presumably, is Jean (Johnny) Voste, born in Belgian Congo, who was the only black prisoner in Dachau. Dachau, Germany, May 1945."". US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

- ^ "Blacks During the Holocaust". Holocaust Encyclopedia. US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 26 September 2012.

Bibliography

- Bishop, Lt. Col. Leo V.; Glasgow, Maj. Frank J.; Fisher, Maj. George A., eds. (1946). The Fighting Forty-Fifth: the Combat Report of an Infantry Division. Baton Rouge, Louisiana.: 45th Infantry Division [Army & Navy Publishing Co.] OCLC 4249021.

- Buechner, Howard A. (1986). Dachau—The Hour of the Avenger. Thunderbird Press. ISBN 0-913159-04-2.

- Edkins, Jenny (2003). Trauma and the memory of politics. Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-53420-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Kozal, Czesli W.; Ischler, Paul (Translator) (2004). Memoir of Fr. Czesli W. (Chester) Kozal, O.M.I. Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate. OCLC 57253860.

{{cite book}}:|first2=has generic name (help) - Marcuse, Harold (2001). Legacies of Dachau: The Uses and Abuses of a Concentration Camp, 1933-2001. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55204-2.

- Roberts, Donald R. ; edited by Heather R. Biola (2008). The other war, a World War II journal. Elkins, W.V.: McClain Printing Co. ISBN 978-0-87012-775-5.

{{cite book}}:|author=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) Includes report written for: United States. Army. Infantry Division, 9th. Office of the Surgeon. Interrogation of SS Officers and Men at Dachau.

External links

- 7th Army, U.S. (1945). Dachau. University of Wisconsin Digital Collection.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Anderson, Stuart (2008–2010). "Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial". Destination Munich.

- Video Footage showing the Liberation of Dachau

- The short film A GERMAN IS TRIED FOR MURDER [ETC. (1945)] is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- "Communists to be interned in Dachau". The Guardian. 21 March 1933.

- Cramer, Douglas. "Dachau 1945: The Souls of All Are Aflame". Orthodoxy Today.org.

- "Dachau Concentration Camp Memorial Site". Stiftung Bayerische Gedenkstätten, German. Retrieved 2 March 2010.

- "Dachau Memorial Site, UCSB Department of History". Professor Harold Marcuse, PhD. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- Doyle, Chris (2009). "Dachau (Konzentrationslager Dachau): An Overview". Never Again! Online Holocaust Memorial.

- "Eleven Subcamps of Dachau Online Memorial". Kaufering.com.

- "Interior and exterior images of the Dachau camp". Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- Perez, R.H. (2002). "Dachau Concentration Camp — Liberation: A Documentary — U. S. Massacre of Waffen SS — April 29, 1945". Humanitas International. Retrieved 28 February 2010.

- "The European Holocaust Memorial". Landsberg im 20. Jahrhundert.