Financial District, Manhattan

Financial District | |

|---|---|

![The Financial District of Lower Manhattan, including Wall Street, is the world's principal financial and fintech center.[1]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/dc/NYC_Downtown_Manhattan_Skyline_seen_from_Paulus_Hook_2019-12-20_IMG_7347_FRD.jpg/300px-NYC_Downtown_Manhattan_Skyline_seen_from_Paulus_Hook_2019-12-20_IMG_7347_FRD.jpg) The Financial District of Lower Manhattan, including Wall Street, is the world's principal financial and fintech center.[1] | |

Location in New York City | |

| Coordinates: 40°42′27″N 74°00′33″W / 40.70750°N 74.00917°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| City | New York City |

| Borough | Manhattan |

| Community District | Manhattan 1[2] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.17 km2 (0.453 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 57,627 |

| • Density | 49,000/km2 (130,000/sq mi) |

| Economics | |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 10004–10007, 10038 |

| Area code | 212, 332, 646, and 917 |

The Financial District of Lower Manhattan, also known as FiDi,[3] is a neighborhood located on the southern tip of Manhattan in New York City. It is bounded by the West Side Highway on the west, Chambers Street and City Hall Park on the north, Brooklyn Bridge on the northeast, the East River to the southeast, and South Ferry and the Battery on the south.

The City of New York was created in the modern-day Financial District in 1624, and the neighborhood roughly overlaps with the boundaries of the New Amsterdam settlement in the late 17th century.[4] The district comprises the offices and headquarters of many of the city's major financial institutions, including the New York Stock Exchange and the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Anchored on Wall Street in the Financial District, New York City has been called both the leading financial center and the most economically powerful city of the world,[5][6] and the New York Stock Exchange is the world's largest stock exchange by total market capitalization.[7][8] Several other major exchanges have or had headquarters in the Financial District, including the New York Mercantile Exchange, NASDAQ, the New York Board of Trade, and the former American Stock Exchange.

The Financial District is part of Manhattan Community District 1, and its primary ZIP Codes are 10004, 10005, 10006, 10007, and 10038.[2] It is patrolled by the 1st Precinct of the New York City Police Department.

Description

[edit]The Financial District encompasses roughly the area south of City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan but excludes Battery Park and Battery Park City. The former World Trade Center complex was located in the neighborhood until the September 11, 2001, attacks; the neighborhood includes the successor One World Trade Center. The heart of the Financial District is often considered to be the corner of Wall Street and Broad Street, both of which are contained entirely within the district.[9] The northeastern part of the Financial District (along Fulton Street and John Street) was known in the early 20th century as the Insurance District, due to the large number of insurance companies that were either headquartered there, or maintained their New York offices there.

Although the term is sometimes used as a synonym for Wall Street, the latter term is often applied metonymously to the financial markets as a whole (and is also a street in the district), whereas "the Financial District" implies an actual geographical location. The Financial District is part of Manhattan Community Board 1, which also includes five other neighborhoods (Battery Park City, Civic Center, Greenwich South, Seaport, and Tribeca).[2]

Street grid

[edit]

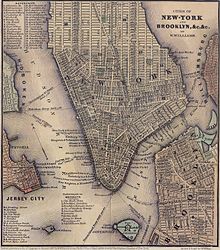

The streets in the area were laid out as part of the Castello Plan prior to the Commissioners' Plan of 1811, a grid plan that dictates the placement of most of Manhattan's streets north of Houston Street. Thus, it has small streets "barely wide enough for a single lane of traffic are bordered on both sides by some of the tallest buildings in the city", according to one description, which creates "breathtaking artificial canyons".[10] Some streets have been designated as pedestrian-only with vehicular traffic prohibited.[11]

Tourism

[edit]The Financial District is a major location of tourism in New York City. One report described Lower Manhattan as "swarming with camera-carrying tourists".[12] Tour guides highlight places such as Trinity Church, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building gold vaults 80 feet below street level (worth $100 billion), and the New York Stock Exchange Building.[13] A Scoundrels of Wall Street Tour is a walking historical tour which includes a museum visit and discussion of various financiers "who were adept at finding ways around finance laws or loopholes through them".[14] Occasionally artists make impromptu performances; for example, in 2010, a troupe of 22 dancers "contort their bodies and cram themselves into the nooks and crannies of the Financial District in Bodies in Urban Spaces" choreographed by Willi Donner.[15] One chief attraction, the Federal Reserve, paid $750,000 to open a visitors' gallery in 1997. The New York Stock Exchange and the American Stock Exchange also spent money in the late 1990s to upgrade facilities for visitors. Attractions include the gold vault beneath the Federal Reserve and that "staring down at the trading floor was as exciting as going to the Statue of Liberty".[12]

Architecture

[edit]The Financial District's architecture is generally rooted in the Gilded Age, though there are also some art deco influences in the neighborhood. The area is distinguished by narrow streets, a steep topography, and high-rises[10] Construction in such narrow steep areas has resulted in occasional accidents such as a crane collapse.[16] One report divided lower Manhattan into three basic districts:[10]

- The Financial District proper—particularly along John Street

- South of the World Trade Center area—the handful of blocks located south of the World Trade Center along Greenwich, Washington and West Streets

- Seaport district—characterized by century-old low-rise buildings and South Street Seaport; the seaport is "quiet, residential, and has an old world charm" according to one description.[10]

Federal Hall National Memorial, on the site of the first U.S. capitol and the first inauguration of George Washington as the first President of the United States, is located at the corner of Wall Street and Nassau Street.

The Financial District has a number of tourist attractions such as the South Street Seaport Historic District, newly renovated Pier 17, the New York City Police Museum, the Museum of American Finance, the National Museum of the American Indian, Trinity Church, St. Paul's Chapel, and the famous bull. Bowling Green is the starting point of traditional ticker-tape parades on Broadway, where here it is also known as the Canyon of Heroes. The Museum of Jewish Heritage and the Skyscraper Museum are both in adjacent Battery Park City which is also home to the Brookfield Place (formerly World Financial Center).

Another key anchor for the area is the New York Stock Exchange. City authorities realize its importance, and believed that it has "outgrown its neoclassical temple at the corner of Wall and Broad streets", and in 1998 offered substantial tax incentives to try to keep it in the Financial District.[17] Plans to rebuild it were delayed by the September 11, 2001, attacks.[17] The Exchange still occupies the same site. The Exchange is the locus for a large amount of technology and data. For example, to accommodate the three thousand persons who work directly on the Exchange floor requires 3,500 kilowatts of electricity, along with 8,000 phone circuits on the trading floor alone, and 200 miles of fiber-optic cable below ground.[18]

Official landmarks

[edit]Buildings in the Financial District can have one of several types of official landmark designations:

- The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission is the New York City agency that is responsible for identifying and designating the city's landmarks and the buildings in the city's historic districts. New York City landmarks (NYCL) can be categorized into one of several groups: individual (exterior), interior, and scenic landmarks.[19]

- The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance.[20]

- The National Historic Landmark (NHL) focuses on places of significance in American history, architecture, engineering, or culture; all NHL sites are also on the NRHP.[21]

The following landmarks are situated south of Morris Street and west of Whitehall Street/Broadway:[22]

- 21 West Street (NRHP, NYCL)[23]

- Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, Bowling Green (NHL, NRHP, NYCL, NYCL interior)[24]

- Bowling Green fence (NYCL)[25]

- Bowling Green (NRHP)[26]

- Bowling Green Offices Building, 11 Broadway (NYCL)[27]

- Castle Clinton, the Battery (NRHP, NYCL)[28]

- City Pier A, the Battery (NRHP, NYCL)[29]

- Cunard Building, 25 Broadway (NYCL, NYCL interior)[30]

- Downtown Athletic Club, 19 West Street (NYCL)[31]

- Interborough Rapid Transit System, Battery Park Control House (NRHP, NYCL)[32]

- International Mercantile Marine Company Building, 1 Broadway (NRHP, NYCL)[33]

- James Watson House, 7 State Street (NRHP, NYCL)[34]

- Whitehall Building, 17 Battery Place (NYCL)[35]

The following landmarks are located west of Broadway between Morris and Barclay Streets:[22]

- American Stock Exchange Building (NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[36]

- 65 Broadway (NYCL)[37]

- 90 West Street (NRHP, NYCL)[38]

- 94 Greenwich Street (NYCL)[39]

- 195 Broadway (NYCL, NYCL interior)[40]

- Empire Building, 71 Broadway (NRHP, NYCL)[41]

- New York County Lawyers' Association Building, 14 Vesey Street (NRHP, NYCL)[42]

- Old New York Evening Post Building, 20 Vesey Street (NRHP, NYCL)[43]

- Robert and Anne Dickey House, 67 Greenwich Street (NYCL)[44]

- St. George's Syrian Catholic Church, 103 Washington Street (NYCL)[45]

- St. Paul's Chapel, Broadway at Fulton Street (NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[46]

- St. Peter's Roman Catholic Church, 22 Barclay Street (NRHP, NYCL)[47]

- Trinity and United States Realty Buildings, 111-115 Broadway (both NYCL)[48]

- Trinity Church, Broadway at Wall Street (NRHP, NYCL)[49]

- Verizon Building, 140 West Street (NRHP, NYCL, NYCL interior)[50]

The following landmarks are located south of Wall Street and east of Broadway/Whitehall Street:[22]

- 1 Hanover Square (NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[51]

- 1 Wall Street (NYCL)[52]

- 1 Wall Street Court (NRHP, NYCL)[53]

- 1 William Street (NYCL)[54]

- 20 Exchange Place (NYCL)[55]

- 23 Wall Street (NRHP, NYCL)[56]

- 26 Broadway (NYCL)[57]

- 55 Wall Street (NRHP, NYCL, NYCL interior)[58]

- American Bank Note Company Building, 70 Broad Street (NRHP, NYCL)[59]

- Battery Maritime Building, South Street (NRHP, NYCL)[60]

- Broad Exchange Building, 25 Broad Street (NRHP, NYCL)[61]

- Delmonico's Building, 56 Beaver Street (NYCL)[62]

- First Precinct Police Station, 100 Old Slip (NRHP, NYCL)[63]

- Fraunces Tavern, 54 Pearl Street (NRHP, NYCL)[64]

- New York Stock Exchange Building, 8-18 Broad Street (NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[65]

- Wall and Hanover Building, 59–63 Wall Street (NRHP)[66]

The following landmarks are located east of Broadway between Wall Street and Maiden Lane:[22]

- 14 Wall Street (NYCL)[67]

- 28 Liberty Street (NYCL)[68]

- 40 Wall Street (NRHP, NYCL)[69]

- 48 Wall Street (NRHP, NYCL)[70]

- 56 Pine Street (NRHP, NYCL)[71]

- 70 Pine Street (NYCL, NYCL interior)[72]

- 90–94 Maiden Lane (NYCL)[73]

- American Surety Building, 100 Broadway (NYCL)[74]

- Chamber of Commerce Building, 65 Liberty Street (NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[75]

- Down Town Association Building, 60 Pine Street (NYCL)[76]

- Equitable Building (NHL, NRHP, NYCL)[77]

- Federal Hall National Memorial, 26 Wall Street (NHL, NRHP, NYCL, NYCL interior)[78]

- Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building, 33 Liberty Street (NRHP, NYCL)[79]

- Liberty Tower, 55 Liberty Street (NRHP, NYCL)[80]

- Marine Midland Building, 140 Broadway (NYCL)[81]

The following landmarks are located east of Broadway and Park Row between Maiden Lane and the Brooklyn Bridge:[22]

- 5 Beekman Street (NYCL)[82]

- 63 Nassau Street (NYCL)[83]

- 150 Nassau Street (NYCL)[84]

- Bennett Building, 99 Nassau Street (NYCL)[85]

- Corbin Building, 13 John Street (NRHP, NYCL)[86]

- Excelsior Power Company Building, 33–43 Gold Street (NYCL)[87]

- John Street Methodist Church, 44 John Street (NRHP, NYCL)[88]

- Keuffel & Esser Company Building, 127 Fulton Street (NYCL)[89]

- Morse Building, 138-42 Nassau Street (NYCL)[90]

- New York Times Building, 41 Park Row (NYCL)[91]

- Park Row Building, 15 Park Row (NRHP, NYCL)[92]

- Potter Building, 38 Park Row (NYCL)[93]

The following landmarks apply to multiple distinct areas:[22]

- Fraunces Tavern Block Historic District (NRHP, NYCL)[94]

- South Street Seaport Historic District (NRHP, NYCL; includes numerous individual landmarks)[95]

- Street Plan of New Amsterdam and Colonial New York (NYCL)[96]

- Stone Street Historic District (NYCL)[97]

- Wall Street, Fulton Street station interiors (NYCL)[98]

History

[edit]New Amsterdam

[edit]

What is now the Financial District was once part of New Amsterdam, situated on the strategic southern tip of the island of Manhattan. New Amsterdam was derived from Fort Amsterdam, meant to defend the fur trade operations of the Dutch West India Company in the North River (Hudson River). In 1624, it became a provincial extension of the Dutch Republic and was designated as the capital of the province of New Netherland in 1625.[99] By 1655, the population of New Netherland had grown to 2,000 people, with 1,500 living in New Amsterdam. By 1664, the population of New Netherland had skyrocketed to almost 9,000 people, 2,500 of whom lived in New Amsterdam, 1,000 lived near Fort Orange, and the remainder in other towns and villages.[100][101] In 1664 the English took over New Amsterdam and renamed it New York City.[102]

19th and 20th centuries

[edit]In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the corporate culture of New York was a primary center for the construction of early skyscrapers, and was rivaled only by Chicago on the American continent. There were also residential sections, such as the Bowling Green section between Broadway and the Hudson River, and between Vesey Street and the Battery. The Bowling Green area was described as "Wall Street's back yard" with poor people, high infant mortality rates, and the "worst housing conditions in the city".[103] As a result of the construction, looking at New York City from the east, one can see two distinct clumps of tall buildings—the Financial District on the left, and the taller Midtown neighborhood on the right. The geology of Manhattan is well-suited for tall buildings, with a solid mass of bedrock underneath Manhattan providing a firm foundation for tall buildings. Skyscrapers are expensive to build, but the scarcity of land in the Financial District made it suitable for the construction of skyscrapers.[104]

Business writer John Brooks in his book Once in Golconda considered the start of the 20th century period to have been the area's heyday.[105] The address of 23 Wall Street, the headquarters of J. P. Morgan & Company, known as The Corner, was "the precise center, geographical as well as metaphorical, of financial America and even of the financial world".[105]

On September 16, 1920, close to the corner of Wall and Broad Street, the busiest corner of the Financial District and across the offices of the Morgan Bank, a powerful bomb exploded. It killed 38 and seriously injured 143 people.[106] The area was subjected to numerous threats; one bomb threat in 1921 led to detectives sealing off the area to "prevent a repetition of the Wall Street bomb explosion".[107]

Late-20th century growth

[edit]

During most of the 20th century, the Financial District was a business community with practically only offices which emptied out at night. Writing in The Death and Life of Great American Cities in 1961, urbanist Jane Jacobs described a "deathlike stillness that settles on the district after 5:30 and all day Saturday and Sunday".[108] But there has been a change towards greater residential use of the area, pushed forwards by technological changes and shifting market conditions. The general pattern is for several hundred thousand workers to commute into the area during the day, sometimes by sharing a taxicab[109] from other parts of the city as well as from New Jersey and Long Island, and then leave at night. In 1970 only 833 people lived "south of Chambers Street"; by 1990, 13,782 people were residents with the addition of areas such as Battery Park City[17] and Southbridge Towers.[110] Battery Park City was built on 92 acres of landfill, and 3,000 people moved there beginning about 1982, but by 1986 there was evidence of more shops and stores and a park, along with plans for more residential development.[111]

Construction of the World Trade Center began in 1966, but the World Trade Center had trouble attracting tenants when completed. Nonetheless, some substantial firms purchased space there. Its impressive height helped make it a visual landmark for drivers and pedestrians. In some respects, the nexus of the Financial District moved physically from Wall Street to the World Trade Center complex and surrounding buildings such as the Deutsche Bank Building, 90 West Street, and One Liberty Plaza. Real estate growth during the latter part of the 1990s was significant, with deals and new projects happening in the Financial District and elsewhere in Manhattan; one firm invested more than $24 billion in various projects, many in the Wall Street area.[112] In 1998, the NYSE and the city struck a $900 million deal which kept the NYSE from moving across the river to Jersey City; the deal was described as the "largest in city history to prevent a corporation from leaving town".[113] A competitor to the NYSE, NASDAQ, moved its headquarters from Washington to New York.[114]

In 1987, the stock market plunged[17] and, in the relatively brief recession following, lower Manhattan lost 100,000 jobs according to one estimate.[110] Since telecommunications costs were coming down, banks and brokerage firms could move away from the Financial District to more affordable locations.[110] The recession of 1990–91 was marked by office vacancy rates downtown which were "persistently high" and with some buildings "standing empty".[10]

Residential neighborhood

[edit]In 1995, city authorities offered the Lower Manhattan Revitalization Plan which offered incentives to convert commercial properties to residential use.[10] According to one description in 1996, "The area dies at night ... It needs a neighborhood, a community."[110] During the past two decades there has been a shift towards greater residential living areas in the Financial District, with incentives from city authorities in some instances.[17] Many empty office buildings have been converted to lofts and apartments; for example, the Liberty Tower, the office building of oil magnate Harry Sinclair, was converted to a co-op in 1979.[110] In 1996, a fifth of buildings and warehouses were empty, and many were converted to living areas.[110] Some conversions met with problems, such as aging gargoyles on building exteriors having to be expensively restored to meet with current building codes.[110] Residents in the area have sought to have a supermarket, a movie theater, a pharmacy, more schools, and a "good diner".[110] The discount retailer named Job Lot used to be located at the World Trade Center but moved to Church Street; merchants bought extra unsold items at steep prices and sold them as a discount to consumers, and shoppers included "thrifty homemakers and browsing retirees" who "rubbed elbows with City Hall workers and Wall Street executives"; but the firm went bust in 1993.[115] There were reports that the number of residents increased by 60% during the 1990s to about 25,000 although a second estimate (based on the 2000 census based on a different map) places the residential population in 2000 at 12,042. By 2001 there were several grocery stores, dry cleaners, and two grade schools and a top high school.[17]

21st century

[edit]September 11 attacks

[edit]In 2001, the Big Board, as some termed the NYSE, was described as the world's "largest and most prestigious stock market".[116] When the World Trade Center was destroyed on September 11, 2001, it left an architectural void as new developments since the 1970s had played off the complex aesthetically. The attacks "crippled" the communications network.[116] One estimate was that 45% of the neighborhood's "best office space" had been lost.[17] The physical destruction was immense:

Debris littered some streets of the financial district. National Guard members in camouflage uniforms manned checkpoints. Abandoned coffee carts, glazed with dust from the collapse of the World Trade Center, lay on their sides across sidewalks. Most subway stations were closed, most lights were still off, most telephones did not work, and only a handful of people walked in the narrow canyons of Wall Street yesterday morning.

— Leslie Eaton and Kirk Johnson of The New York Times, September 16, 2001.[18]

Still, the NYSE was determined to re-open on September 17, almost a week after the attack.[18] After September 11, the financial services industry went through a downturn with a sizable drop in year-end bonuses of $6.5 billion, according to one estimate from a state comptroller's office.[115]

To guard against a vehicular bombing in the area, authorities built concrete barriers, and found ways over time to make them more aesthetically appealing by spending $5000 to $8000 apiece on bollards. Several streets in the neighborhood, including Wall and Broad Streets, were blocked off by specially designed bollards:

Rogers Marvel designed a new kind of bollard, a faceted piece of sculpture whose broad, slanting surfaces offer people a place to sit in contrast to the typical bollard, which is supremely unsittable. The bollard, which is called the Nogo, looks a bit like one of Frank Gehry's unorthodox culture palaces, but it is hardly insensitive to its surroundings. Its bronze surfaces actually echo the grand doorways of Wall Street's temples of commerce. Pedestrians easily slip through groups of them as they make their way onto Wall Street from the area around historic Trinity Church. Cars, however, cannot pass.

— Blair Kamin in the Chicago Tribune, 2006

Redevelopment

[edit]The destruction of the World Trade Center spurred development on a scale that had not been seen in decades.[104] Tax incentives provided by federal, state and local governments encouraged development. A new World Trade Center complex centered on Daniel Libeskind's Memory Foundations was after the 9/11 attacks. The centerpiece, which is now a 1,776 ft (541 m) tall structure, opened in 2014 as the One World Trade Center.[117] Fulton Center, a new transit complex intended to improve access to the area, opened in 2014,[118] followed by the World Trade Center Transportation Hub in 2016.[119][120] Additionally, in 2007, the Maharishi Global Financial Capital of New York opened headquarters at 70 Broad Street near the NYSE, in an effort to seek investors.[121]

By the 2010s, the Financial District had become established as a residential and commercial neighborhood. Several new skyscrapers such as 125 Greenwich Street and 130 William were being developed, while other structures such as 1 Wall Street, the Equitable Building, and the Woolworth Building were extensively renovated.[122] Additionally, there were more signs of dogwalkers at night and a 24-hour neighborhood, although the general pattern of crowds during the working hours and emptiness at night was still apparent. There were also ten hotels and thirteen museums in 2010.[10] In 2007 the French fashion retailer Hermès opened a store in the Financial District to sell items such as a "$4,700 custom-made leather dressage saddle or a $47,000 limited edition alligator briefcase".[11] However, there are reports of panhandlers like elsewhere in the city.[123] By 2010 the residential population had increased to 24,400 residents.[124] and the area was growing with luxury high-end apartments and upscale retailers.[125]

On October 29, 2012, New York and New Jersey were inundated by Hurricane Sandy. Its 14-foot-high storm surge, a local record, caused massive street flooding in many parts of Lower Manhattan. Power to the area was knocked out by a transformer explosion at a Con Edison plant. With mass transit in New York City already suspended as a precaution even before the storm hit, the New York Stock Exchange and other financial exchanges were closed for two days, re-opening on October 31.[126] From 2013 to 2021, nearly two hundred buildings in the Financial District were converted to residential use. Furthermore, between 2001 and 2021, the proportion of companies in the area that were in the finance and insurance industries declined from 55 to 30 percent.[127]

Demographics

[edit]For census purposes, the New York City government classifies the Financial District as part of a larger neighborhood tabulation area called Battery Park City-Lower Manhattan.[128] Based on data from the 2010 United States Census, the population of Battery Park City-Lower Manhattan was 39,699, an increase of 19,611 (97.6%) from the 20,088 counted in 2000. Covering an area of 479.77 acres (194.16 ha), the neighborhood had a population density of 82.7/acre (52,900/sq mi; 20,400/km2).[129] The racial makeup of the neighborhood was 65.4% (25,965) White, 3.2% (1,288) African American, 0.1% (35) Native American, 20.2% (8,016) Asian, 0.0% (17) Pacific Islander, 0.4% (153) from other races, and 3.0% (1,170) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 7.7% (3,055) of the population.[130]

The entirety of Community District 1, which comprises the Financial District and other Lower Manhattan neighborhoods, had 63,383 inhabitants as of NYC Health's 2018 Community Health Profile, with an average life expectancy of 85.8 years.[131]: 2, 20 This is higher than the median life expectancy of 81.2 for all New York City neighborhoods.[132]: 53 (PDF p. 84) [133] Most inhabitants are young to middle-aged adults: half (50%) are between the ages of 25–44, while 14% are between 0–17, and 18% between 45–64. The ratio of college-aged and elderly residents was lower, at 11% and 7% respectively.[131]: 2

As of 2017, the median household income in Community Districts 1 and 2 (including Greenwich Village and SoHo) was $144,878.[134] In 2018, an estimated 9% of Financial District and Lower Manhattan residents lived in poverty, compared to 14% in all of Manhattan and 20% in all of New York City. One in twenty-five residents (4%) were unemployed, compared to 7% in Manhattan and 9% in New York City. Rent burden, or the percentage of residents who have difficulty paying their rent, is 38% in Financial District and Lower Manhattan, compared to the boroughwide and citywide rates of 45% and 51% respectively. Based on this calculation, as of 2018[update], Financial District and Lower Manhattan are considered high-income relative to the rest of the city and not gentrifying.[131]: 7

The population of the Financial District has grown to an estimated 61,000 residents as of 2018,[135] up from 43,000 as of 2014, which in turn was nearly double the 23,000 recorded at the 2000 Census.[136]

Political representation

[edit]Local

[edit]In the New York City Council, the Financial District is part of District 1, represented by Democrat Christopher Marte.[137][138]

List of aldermen/councilmen who have represented the Financial District

- 1922–1930: Martin F. Tanahey, Democratic

- 1938–1947: Borough-wide proportional representation

- 1965–1974: Saul Sharison

- 1974–1977: Anthony Gaeta, Democratic

- 1977–1985: Nicholas LaPorte, Democratic

- 1985: Frank Fossella, Democratic

- 1986–1990: Susan Molinari, Republican

- 1990–1991: Alfred C. Cerullo III, Republican

- 1991–2001: Kathryn E. Freed, Democratic

- 2002–2010: Alan Gerson, Democratic

- 2010–2021: Margaret Chin, Democratic

- 2022–present: Christopher Marte, Democratic

State

[edit]The Financial District is part of New York's 27th State Senate district,[139] represented by Brian P. Kavanagh.[140] In the New York State Assembly, the neighborhood is in the 61st, 65th, and 66th districts,[139] represented respectively by Charles Fall, Grace Lee, and Deborah Glick.[141]

| Years | New York County's 1st District |

|---|---|

| 1902 | Thomas F. Baldwin, Democratic |

| 1903 | Andrew J. Doyle, Democratic |

| 1904–1906 | Thomas B. Caughlan, Democratic |

| 1907 | James F. Cavanaugh, Democratic |

| 1908–1914 | Thomas B. Caughlan, Democratic |

| 1915–1917 | John J. Ryan, Democratic |

| 1918–1930 | Peter J. Hamill, Democratic |

| 1930 | Vacant |

| 1930–1942 | James J. Dooling, Democratic |

| 1943–1944 | John J. Lamula, Republican |

| 1945–1946 | MacNeil Mitchell, Republican |

| 1947–1954 | Maude E. Ten Eyck, Republican |

| 1955–1965 | William F. Passannante, Democratic |

Federal

[edit]Politically, the Financial District in New York's 10th congressional district;[142] as of 2022[update], it is represented by Dan Goldman.[143]

Police and crime

[edit]Financial District and Lower Manhattan are patrolled by the 1st Precinct of the NYPD, located at 16 Ericsson Place.[144] The 1st Precinct ranked 63rd safest out of 69 patrol areas for per-capita crime in 2010. Though the number of crimes is low compared to other NYPD precincts, the residential population is also much lower.[145] As of 2018[update], with a non-fatal assault rate of 24 per 100,000 people, Financial District and Lower Manhattan's rate of violent crimes per capita is less than that of the city as a whole. The incarceration rate of 152 per 100,000 people is lower than that of the city as a whole.[131]: 8

The 1st Precinct has a lower crime rate than in the 1990s, with crimes across all categories having decreased by 86.3% between 1990 and 2018. The precinct reported 1 murder, 23 rapes, 80 robberies, 61 felony assaults, 85 burglaries, 1,085 grand larcenies, and 21 grand larcenies auto in 2018.[146]

Fire safety

[edit]The Financial District is served by three New York City Fire Department (FDNY) fire stations:[147]

- Engine Company 4/Ladder Company 15/Decon Unit – 42 South Street[148]

- Engine Company 6 – 49 Beekman Street[149]

- Engine Company 10/Ladder Company 10 – 124 Liberty Street[150]

Health

[edit]As of 2018[update], preterm births and births to teenage mothers are less common in Financial District and Lower Manhattan than in other places citywide. In Financial District and Lower Manhattan, there were 77 preterm births per 1,000 live births (compared to 87 per 1,000 citywide), and 2.2 teenage births per 1,000 live births (compared to 19.3 per 1,000 citywide), though the teenage birth rate is based on a small sample size.[131]: 11 Financial District and Lower Manhattan have a low population of residents who are uninsured. In 2018, this population of uninsured residents was estimated to be 4%, less than the citywide rate of 12%, though this was based on a small sample size.[131]: 14

The concentration of fine particulate matter, the deadliest type of air pollutant, in Financial District and Lower Manhattan is 0.0096 mg/m3 (9.6×10−9 oz/cu ft), more than the city average.[131]: 9 Sixteen percent of Financial District and Lower Manhattan residents are smokers, which is more than the city average of 14% of residents being smokers.[131]: 13 In Financial District and Lower Manhattan, 4% of residents are obese, 3% are diabetic, and 15% have high blood pressure, the lowest rates in the city—compared to the citywide averages of 24%, 11%, and 28% respectively.[131]: 16 In addition, 5% of children are obese, the lowest rate in the city, compared to the citywide average of 20%.[131]: 12

Ninety-six percent of residents eat some fruits and vegetables every day, which is more than the city's average of 87%. In 2018, 88% of residents described their health as "good", "very good", or "excellent", more than the city's average of 78%.[131]: 13 For every supermarket in Financial District and Lower Manhattan, there are 6 bodegas.[131]: 10

The nearest major hospital is NewYork-Presbyterian Lower Manhattan Hospital in the Civic Center area.[151][152]

Post offices and ZIP Codes

[edit]Financial District is located within several ZIP Codes. The largest ZIP Codes are 10004, centered around the Battery; 10005, around Wall Street; 10006, around the World Trade Center; 10007, around City Hall; and 10038, around South Street Seaport. There are also several smaller ZIP Codes spanning one block, including 10045 around the Federal Reserve Bank; 10271 around the Equitable Building; and 10279 around the Woolworth Building.[153]

The United States Postal Service operates four post offices in the Financial District:

- Church Street Station – 90 Church Street[154]

- Hanover Station – 1 Hanover Street[155]

- Peck Slip Station – 114 John Street[156]

- Whitehall Station – 1 Whitehall Street[157]

Education

[edit]Financial District and Lower Manhattan generally have a higher rate of college-educated residents than the rest of the city as of 2018[update]. The vast majority of residents age 25 and older (84%) have a college education or higher, while 4% have less than a high school education and 12% are high school graduates or have some college education. By contrast, 64% of Manhattan residents and 43% of city residents have a college education or higher.[131]: 6 The percentage of Financial District and Lower Manhattan students excelling in math rose from 61% in 2000 to 80% in 2011, and reading achievement increased from 66% to 68% during the same time period.[158] The Financial District is home to Pace University's New York City Campus, one of the oldest Universities in New York City.

Financial District and Lower Manhattan's rate of elementary school student absenteeism is lower than the rest of New York City. In Financial District and Lower Manhattan, 6% of elementary school students missed twenty or more days per school year, less than the citywide average of 20%.[131]: 6 [132]: 24 (PDF p. 55) Additionally, 96% of high school students in Financial District and Lower Manhattan graduate on time, more than the citywide average of 75%.[131]: 6

Schools

[edit]

The New York City Department of Education operates the following public schools in the Financial District:[159]

- Urban Assembly School of Business for Young Women (grades 9-12)[160]

- Spruce Street School (grades PK-8)[161]

- Millennium High School (grades 9-12)[162]

- Leadership and Public Service High School (grades 9-12)[163]

- Manhattan Academy for Arts and Languages (grades 9-12)[164]

- High School of Economics and Finance (grades 9-12)[165]

Libraries

[edit]The New York Public Library (NYPL) operates two branches nearby. The New Amsterdam branch is located at 9 Murray Street near Broadway. It was established on the ground floor of an office building in 1989.[166] The Battery Park City branch is located at 175 North End Avenue near Murray Street. Completed in 2010, the two-story branch is NYPL's first LEED-certified branch.[167]

Transportation

[edit]The following New York City Subway stations are located in the Financial District:[168]

- Bowling Green, Wall Street (4 and 5 trains)

- Broad Street (J and Z trains)

- Chambers–WTC–Park Place–Cortlandt Street (2, 3, A, C, and E trains)

- City Hall, Rector Street (N, R, and W trains)

- Fulton Street (A and C trains)

- Rector Street, WTC Cortlandt (1, 2, and 3 trains)

- South Ferry/Whitehall Street (1, N, R, and W trains)

The largest transit hub, Fulton Center, was completed in 2014 after a $1.4 billion reconstruction project necessitated by the September 11, 2001, attacks, and involves at least five different sets of platforms. This transit hub was expected to serve 300,000 daily riders as of late 2014.[169] The World Trade Center Transportation Hub and PATH station opened in 2016.[170]

MTA Regional Bus Operations also operates several bus routes in the Financial District, namely the M15, M15 SBS, M20, M55 and M103 routes running north–south through the area, and the M9 and M22 routes running west–east through the area. There are also many MTA express bus routes running through the Financial District.[171] The Lower Manhattan Development Corporation started operating a free shuttle bus, the Downtown Connection, in 2003;[172] the route circulates around the Financial District during the daytime.[173]

Ferry services are also concentrated downtown, including the Staten Island Ferry at the Whitehall Terminal;[174] NYC Ferry at Pier 11/Wall Street and Battery Park City Ferry Terminal;[175] and service to Governors Island at the Battery Maritime Building.[176]

Tallest buildings

[edit]| Name | Image | Height ft (m) |

Floors | Year | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One World Trade Center |

|

1,776 (541.3) | 104 | 2014 | Is the seventh-tallest building in the world and the tallest building in the United States since its topping out on May 10, 2013. It is also the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere and the tallest all-office building in the world.[177][178] |

| 3 World Trade Center |

|

1,079 (329) | 80 | 2018 | Mixed use; opened in 2018.[179] |

| 4 World Trade Center |

|

978 (298) | 74 | 2013 | Third-tallest building at the rebuilt World Trade Center and in the Financial District. The building opened to tenants in 2013.[180] |

| 70 Pine Street |

|

952 (290) | 66 | 1932 | 22nd-tallest building in the United States; formerly known as the American International Building and the Cities Service Building[181][182] 70 Pine is being transformed into a residential skyscraper with 644 rental residences, 132 hotel rooms and 35,000 square feet (3,300 square meters) of retail[183] |

| 30 Park Place |

|

937 (286) | 82 | 2016 | Four Seasons Private Residences and Hotel. Topped-out in 2015 and completed in 2016.[184] |

| 40 Wall Street |

|

927 (283) | 70 | 1930 | 26th-tallest in the United States; was world's tallest building for less than two months in 1930; formerly known as the Bank of Manhattan Trust Building; also known as 40 Wall Street[185][186] |

| 28 Liberty Street |

|

813 (248) | 60 | 1961 | [187][188] |

| 50 West Street |

|

778 (237) | 63 | 2016 | [189][190] |

| 200 West Street |

|

749 (228) | 44 | 2010 | Also known as Goldman Sachs World Headquarters[191][192] |

| 60 Wall Street |

|

745 (227) | 55 | 1989 | Also known as Deutsche Bank Building[193][194] |

| One Liberty Plaza |

|

743 (226) | 54 | 1973 | Formerly known as the U.S. Steel Building[195][196] |

| 20 Exchange Place |

|

741 (226) | 57 | 1931 | Formerly known as the City Bank-Farmers Trust Building[197][198] |

| 200 Vesey Street |

|

739 (225) | 51 | 1986 | Also known as Three World Financial Center[199][200] |

| HSBC Bank Building |

|

688 (210) | 52 | 1967 | Also known as Marine Midland Building[201][202] |

| 55 Water Street |

|

687 (209) | 53 | 1972 | [203][204] |

| 1 Wall Street |

|

654 (199) | 50 | 1931 | Also known as Bank of New York Mellon Building[205][206] |

| 225 Liberty Street |

|

645 (197) | 44 | 1987 | Also known as Two World Financial Center[207][208] |

| 1 New York Plaza |

|

640 (195) | 50 | 1969 | [209][210] |

| Home Insurance Plaza |

|

630 (192) | 45 | 1966 | [211][212] |

Gallery

[edit]-

The Broad Street facade of the New York Stock Exchange

-

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York building

-

The former House of Morgan building at 23 Wall Street

-

Federal Hall, once the U.S. Custom House, now a museum, with the towers of Wall Street behind it

-

One Liberty Plaza, one of the many modern skyscrapers in the area

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Jones, Huw (March 24, 2022). "New York widens lead over London in top finance centres index". www.reuters.com. Archived from the original on June 11, 2022. Retrieved June 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c "NYC Planning | Community Profiles". communityprofiles.planning.nyc.gov. New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on March 20, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Couzzo, Steve (April 25, 2007). "FiDi Soaring High". New York Post. Archived from the original on December 13, 2022. Retrieved December 3, 2014.

The Financial District is over. So is the "Wall Street area." But say hello to FiDi, the coinage of major downtown landlord Kent Swig, who decided it's time to humanize the old F.D. with an easily remembered, fun-sounding acronym.

- ^ "Manhattan, New York – Some of the Most Expensive Real Estate in the World Overlooks Central Park". The Pinnacle List. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 24, 2014.

- ^ "The Global Financial Centres Index 34". Long Finance. September 28, 2023. Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 28, 2023.

- ^ Richard Florida (March 3, 2015). "Sorry, London: New York Is the World's Most Economically Powerful City". Bloomberg.com. The Atlantic Monthly Group. Archived from the original on March 14, 2015. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

Our new ranking puts the Big Apple firmly on top.

- ^ "2013 WFE Market Highlights" (PDF). World Federation of Exchanges. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 27, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

- ^ "NYSE Listings Directory". Archived from the original on July 19, 2008. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Aaron Donovan (September 9, 2001). "If You're Thinking of Living In/The Financial District; In Wall Street's Canyons, Cliff Dwellers". The New York Times: Real Estate. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Claire Wilson (July 29, 2007). "Hermès Tempts the Men of Wall Street". The New York Times: Real Estate. Archived from the original on June 5, 2015. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b David M. Halbfinger (August 27, 1997). "New York's Financial District Is a Must-See Tourist Destination". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Lisa W. Foderaro (June 20, 1997). "A Financial District Tour". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ T.L. Chancellor (January 14, 2010). "Walking Tours of NYC". USA Today: Travel. Archived from the original on October 5, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Aaron Rutkoff (September 27, 2010). "'Bodies in Urban Spaces': Fitting In on Wall Street". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 2, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Sarah Wheaton and Ravi Somaiya (March 27, 2010). "Crane Falls Against Financial District Building". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Knox, Noelle; Moor, Martha T. (October 24, 2001). "'Wall Street' migrates to Midtown". USA Today. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c Eaton, Leslie; Johnson, Kirk (September 16, 2001). "After the Attacks: Wall Street; Straining to Ring the Opening Bell". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Landmark Types and Criteria - LPC". NYC.gov. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "How to List a Property". National Register of Historic Places (U.S. National Park Service). November 26, 2019. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ "Eligibility". National Historic Landmarks (U.S. National Park Service). August 29, 2018. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f "Discover New York City Landmarks". New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. Archived from the original on January 9, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2019 – via ArcGIS.

- ^ "21 West Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 16, 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Historic Structures Report: Building at 21 West Street" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 11, 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: U.S. Custom House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 31, 1972. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Custom House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 14, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Custom House Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 9, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Bowling Green Fence" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 14, 1970. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2019. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Bowling Green" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 29, 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bowling Green Offices Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 1, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Castle Clinton National Monument" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. October 15, 1966. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Castle Clinton" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: City Pier A" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 27, 1975. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Pier A" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 12, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020. - ^ "Cunard Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Cunard Building, First Floor Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Downtown Athletic Club Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 14, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Battery Park Control House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. May 6, 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Interborough Rapid Transit System, Battery Park Control House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 22, 1973. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: International Mercantile Marine Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. March 2, 1991. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"International Mercantile Marine Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 16, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 2, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: James Watson House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. July 24, 1972. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"James Watson House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Whitehall Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 17, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: American Stock Exchange Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 2, 1978. Retrieved February 17, 2020.[permanent dead link]

"New York Curb Exchange (incorporating the New York Curb Market Building), later known as the American Stock Exchange" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 26, 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "American Express Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 12, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: West Street Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 12, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"West Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 19, 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "94 Greenwich Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 23, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "American Telephone and Telegraph Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 25, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"American Telephone and Telegraph Building Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 25, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Empire Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 13, 1983. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Empire Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Old New York County Lawyers' Association Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 30, 1982. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

"New York County Lawyers' Association Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: New York Evening Post Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. August 16, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2020.

"New York Evening Post Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2020. - ^ "Robert and Anne Dickey House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 28, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 16, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Saint George's Syrian Catholic Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 14, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Saint Paul's Chapel" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 23, 1980. Retrieved February 17, 2020.[permanent dead link]

"Saint Paul's Chapel and Graveyard" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 18, 1966. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2019. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Saint Peter's Roman Catholic Church" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 23, 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"St. Peter's Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019. - ^ "Trinity Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 7, 1988. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Realty Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 7, 1988. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Trinity Church and Graveyard" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 8, 1976. Retrieved February 17, 2020.[permanent dead link]

"Trinity Church and Graveyard" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 16, 1966. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 20, 2019. Retrieved July 28, 2019. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Barclay-Vesey Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 30, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Barclay-Vesey Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 1, 1991. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 19, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Barclay-Vesey Building Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 1, 1991. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: New York Cotton Exchange" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. January 7, 1972. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 10, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Hanover Bank" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "1 Wall Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 6, 2001. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Beaver Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. July 6, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Beaver Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 10, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "J. & W. Seligman & Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "City Bank-Farmers Trust Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 16, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: 23 Wall Street Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 19, 1972. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"J. P. Morgan & Co. Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Standard Oil Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 30, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: National City Bank Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 30, 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"National City Bank Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 1, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"National City Bank Building Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 12, 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: American Bank Note Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 30, 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"American Bank Note Company Office Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Municipal Ferry Pier" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 12, 1976. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Whitehall Ferry Terminal, 11 South Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 25, 1967. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Broad Exchange Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 13, 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Broad Exchange Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 27, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 15, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Delmonico's Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 13, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: First Police Precinct Station House" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. October 29, 1982. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"First Precinct Police Station" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 20, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Fraunces Tavern" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. March 6, 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Fraunces Tavern" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 23, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: New York Stock Exchange" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 2, 1978. Retrieved February 17, 2020.[permanent dead link]

"New York Stock Exchange" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. July 9, 1985. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 14, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Wall and Hanover Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 16, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 28, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bankers Trust Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "One Chase Manhattan Plaza" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 10, 2009. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Manhattan Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 16, 2000. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 23, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Manhattan Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 12, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Bank of New York & Trust Company Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. August 28, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Bank of New York & Trust Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 13, 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Wallace Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. August 28, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"56-58 Pine Street" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 11, 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Cities Service Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 21, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Cities Service Building, First Floor Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 21, 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 27, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "90–94 Maiden Lane Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 1, 1989. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 17, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "American Surety Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Chamber of Commerce Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. February 6, 1973. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Chamber of Commerce of the State of New York" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. January 18, 1966. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 13, 2021. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Down Town Association Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 11, 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Equitable Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 2, 1975. Retrieved February 17, 2020.[permanent dead link]

"Equitable Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Federal Hall" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. October 15, 1966. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"United States Custom House" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Federal Hall Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 27, 1975. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. May 6, 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Federal Reserve Bank of New York Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: Liberty Tower" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. September 15, 1983. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Liberty Tower" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. August 24, 1982. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Marine Midland Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2013. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Temple Court Building and Annex" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. February 10, 1998. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "63 Nassau Street Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 15, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "American Tract Society Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 15, 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Bennett Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 21, 1995. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 2, 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Corbin Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 18, 2003. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Corbin Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 24, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Excelsior Steam Power Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 13, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: John Street United Methodist Church" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. June 4, 1973. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"John Street Methodist Church" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. December 21, 1965. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2019. - ^ "Keuffel & Esser Company Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. April 26, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Morse Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 19, 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 6, 2019. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "New York Times Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 6, 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Park Row Building" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. November 16, 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Park Row Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 15, 1999. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Potter Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 7, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved December 6, 2019.

- ^ "Historic Structures Report: Fraunces Tavern Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. April 28, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"Fraunces Tavern Block Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. November 14, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020. - ^ "Historic Structures Report: South Street Seaport Historic District" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 12, 1978. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

"South Street Seaport Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. May 10, 1977. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 21, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2019. - ^ "Street Plan of New Amsterdam and Colonial New York" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 14, 1983. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved February 17, 2020.

- ^ "Stone Street Historic District" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. June 25, 1996. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "IRT Subway System Underground Interior" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. October 23, 1979. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2019.

- ^ "New Amsterdam becomes New York". HISTORY. February 9, 2010. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Jacobs, Jaap (2009). The Colony of New Netherland. p. 32.

- ^ Park, Kingston Ubarn Cultural. "Dutch Colonization". nps.gov. Archived from the original on May 3, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ Schoolcraft, Henry L. (1907). "The Capture of New Amsterdam". English Historical Review. 22 (88): 674–693. doi:10.1093/ehr/XXII.LXXXVIII.674. JSTOR 550138. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2020.

- ^ "TO CLEAR BACK YARD OF WALL ST. DISTRICT; Bowling Green Neighborhood Association Reports Progress in Lower Manhattan. CITY OFFICIALS GIVE AID Work Said to be Experiment Offering Great Promise for a Community Plan". The New York Times. May 14, 1916. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b "Better than flying: Despite the attack on the twin towers, plenty of skyscrapers are rising. They are taller and more daring than ever, but still mostly monuments to magnificence". The Economist. June 1, 2006. Archived from the original on February 1, 2011. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Daniel Gross (October 14, 2007). "The Capital of Capital No More?". The New York Times: Magazine. Archived from the original on November 9, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Beverly Gage, The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in its First Age of Terror. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009; pp. 160-161.

- ^ "DETECTIVES GUARD WALL ST. AGAINST NEW BOMB OUTRAGE; Entire Financial District Patrolled Following Anonymous Warning to a Broker". The New York Times. December 19, 1921. Archived from the original on October 30, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Jacobs, Jane (December 1, 1992). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 155. ISBN 978-0-679-74195-4. Archived from the original on October 23, 2023. Retrieved March 22, 2023.

- ^ Michael M. Grynbaum (June 18, 2009). "Stand That Blazed Cab-Sharing Path Has Etiquette All Its Own". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Michael Cooper (January 28, 1996). "NEW YORKERS & CO.: The Ghosts of Teapot Dome;Fabled Wall Street Offices Are Now Apartments, but Do Not Yet a Neighborhood Make". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 28, 2020. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Michael deCourcy Hinds (March 23, 1986). "SHAPING A LANDFILL INTO A NEIGHBORHOOD". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Laura M. Holson and Charles V. Bagli (November 1, 1998). "Lending Without a Net; With Wall Street as Its Banker, Real Estate Feels the World's Woes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 12, 2010. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Charles V. Bagli (December 23, 1998). "City and State Agree to $900 Million Deal to Keep New York Stock Exchange". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 18, 2013. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Charles V. Bagli (May 7, 1998). "N.A.S.D. Ponders Move to New York City". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 8, 2024. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ a b Lambert, Bruce (December 19, 1993). "NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: LOWER MANHATTAN; At Job Lot, the Final Bargain Days". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 24, 2011. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ a b Berenson, Alex (October 12, 2001). "A NATION CHALLENGED: THE EXCHANGE; Feeling Vulnerable At Heart of Wall St". The New York Times: Business Day. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Dawsey, Josh (October 23, 2014). "One World Trade to Open Nov. 3, But Ceremony is TBD". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 19, 2020. Retrieved October 23, 2014.

- ^ Yee, Vivian (November 9, 2014). "Out of Dust and Debris, a New Jewel Rises". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 24, 2015. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Verrill, Courtney (March 4, 2016). "New York City's $4 billion World Trade Center Transportation Hub is finally open to the public". Business Insider. Archived from the original on February 21, 2017. Retrieved December 20, 2016.

- ^ "World Trade Center transportation hub, dubbed Oculus, opens to public". ABC7 New York. March 3, 2016. Archived from the original on July 8, 2018. Retrieved July 8, 2018.

- ^ MARIA ASPAN (July 2, 2007). "Maharishi's Minions Come to Wall Street". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 14, 2014. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ Plitt, Amy (March 9, 2016). "The Financial District's massive building boom, mapped". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Patty Stonesifer and Sandy Stonesifer (January 23, 2009). "Sister, Can You Spare a Dime? I don't give to my neighborhood panhandlers. Should I?". Slate. Archived from the original on January 17, 2010. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Sushil Cheema (May 29, 2010). "Financial District Rallies as Residential Area". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on October 20, 2022. Retrieved January 14, 2010.

- ^ Michael Stoler (June 28, 2007). "Refashioned: Financial District Is Booming With Business". New York Sun. Archived from the original on August 6, 2020. Retrieved January 15, 2011.

- ^ "Sandy keeps financial markets closed Tuesday". CBS News. October 30, 2012. Archived from the original on December 7, 2020. Retrieved November 20, 2020.

- ^ Bentley, Elliot (September 1, 2021). "How the 9/11 Attacks Remade New York City's Financial District". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on September 1, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived November 29, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P5 NTA: Total Population and Persons Per Acre - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, February 2012. Accessed June 16, 2016.

- ^ Table PL-P3A NTA: Total Population by Mutually Exclusive Race and Hispanic Origin - New York City Neighborhood Tabulation Areas*, 2010 Archived June 10, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Population Division - New York City Department of City Planning, March 29, 2011. Accessed June 14, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o "Financial District (Including Battery Park City, Civic Center, Financial District, South Street Seaport and Tribeca)" (PDF). nyc.gov. NYC Health. 2018. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved March 2, 2019.

- ^ a b "2016-2018 Community Health Assessment and Community Health Improvement Plan: Take Care New York 2020" (PDF). nyc.gov. New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 9, 2022. Retrieved September 8, 2017.

- ^ Short, Aaron (June 4, 2017). "New Yorkers are living longer, happier and healthier lives". New York Post. Archived from the original on March 2, 2019. Retrieved March 1, 2019.

- ^ "NYC-Manhattan Community District 1 & 2--Battery Park City, Greenwich Village & Soho PUMA, NY". Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2018.

- ^ Bob Pisani (May 18, 2018). "New 3 World Trade Center to mark another step in NYC's downtown revival". CNBC. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ C. J. Hughes (August 8, 2014). "The Financial District Gains Momentum". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 7, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2014.

- ^ "Council Members & Districts". New York City Council. Archived from the original on November 2, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2019.

- ^ "District 1". New York City Council. March 25, 2018. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- ^ a b "NYS Redistricting 2021-2023-??". NYS Redistricting 2021-2023-??. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.

- ^ "Our District Brian Kavanagh". NYSenate.gov. Archived from the original on July 8, 2023. Retrieved July 8, 2023.