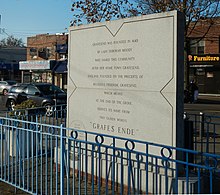

Gravesend, Brooklyn

40°35′54″N 73°58′14″W / 40.5982°N 73.9705°W

Gravesend is a neighborhood in the south-central section of the New York City borough of Brooklyn, in the U.S. state of New York. As of 2010, Gravesend had a population of 29,436.[1]

Gravesend was one of the original towns in the Dutch colony of New Netherland and became one of the six original towns of Kings County in colonial New York. It was the only English chartered town in what became Kings County and was designated the "Shire Town" when the English assumed control, as it was the only one where records could be kept in English. Courts were removed to Flatbush in 1685.

Gravesend is notable for being founded by a woman, Lady Deborah Moody; a land patent was granted to the English settlers by Governor Willem Kieft, December 19, 1645. A prominent early settler was Anthony Janszoon van Salee. Gravesend Town encompassed 7,000 acres (2,800 ha) in southern Kings County, including the entire island of Coney Island, which was originally the town's common lands on the Atlantic Ocean, divided up, as was the town itself, into 41 parcels for the original patentees. When the town was first laid out, almost half were salt marsh wetlands and sandhill dunes along the shore of Gravesend Bay.

Gravesend was annexed by the City of Brooklyn in 1894.[2]

Name

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

The derivation of the name "Gravesend" is unclear. Some speculate that it was named after the English seaport of Gravesend, Kent.[3] An alternative explanation suggests that it was named by Willem Kieft for the Dutch settlement of "'s- Gravesande", which means "Count's Beach" or "Count's Sand".[4][5] There is also a town in the Netherlands called 's-Gravenzande.

Geography

The modern neighborhood of Gravesend lies between Coney Island Avenue to the east, Stillwell Avenue to the west, Kings Highway to the north, and Coney Island Creek and Shore Parkway to the south. To the east of Gravesend is Sheepshead Bay, to the northeast Midwood, to the northwest Bensonhurst, and to the west Bath Beach. To the south, across Coney Island Creek, lies the neighborhood of Coney Island, and across Shore Parkway lies Brighton Beach. The neighborhood center is still the four blocks bounded by Village Road South, Village Road East, Village Road North, and Van Sicklen Street, where the Moody House and Van Sicklen family cemetery are located. Next to, and parallel with the van Sicklen Family Cemetery is the Old Gravesend Cemetery, where Lady Moody is purported to be interred. Gravesend Cemetery's most exotic occupant is Egyptian émigré Mohammad Ben Misoud, who was part of a Coney Island attraction and was afforded a proper Muslim funeral upon his death in August, 1896.

Gravesend is served by three lines of the New York City Subway system. The services and lines, respectively, are the D train on the BMT West End Line at 25th Avenue and Bay 50th Street (facing John Dewey High School); the F and <F> trains on the IND Culver Line at Kings Highway, Avenue U, and Avenue X; and the N and W trains on the BMT Sea Beach Line at Kings Highway, Avenue U, and 86th Street. The Coney Island subway yard is in the neighborhood.[5] Gravesend is patrolled by the NYPD's 60th, 61st, and 62nd Precincts.[6]

History

Early history

The island and its environs were first inhabited by bands of the Lenape.[7] The first known European to set foot in the area that would become Gravesend was Henry Hudson, whose ship, the Half Moon, landed on Coney Island in the fall of 1609.[dubious – discuss]

The land subsequently became part of the New Netherland Colony, and in 1643 it was granted to Deborah Moody, an English expatriate who hoped to establish a community where she and her followers could practice their Anabaptist beliefs free from persecution. Due to clashes with the local native tribes the town wasn't completed until 1645. But when the town charter was finally signed and granted it became one of the first such titles to ever be awarded to a woman in the new world.[8]

The town Lady Moody established was one of the earliest planned communities in America. It consisted of a perfect square surrounded by a 20-foot-high wooden palisade. The town was bisected by two main roads, Gravesend Road (now McDonald Avenue) running from north to south, and Gravesend Neck Road,[8] running from east to west. These roads divided the town into four quadrants which were subdivided into ten plots of land each; the grid of the original town can still be seen on maps and aerial photographs of the area. At the center of town, where the two main roads met, a town hall was constructed where town meetings were held once a month.[5][7] Today, Lady Moody is believed to be buried in Old Gravesend Cemetery.[9]

The religious freedom of early Gravesend made it a desirable home for ostracized or controversial groups, such as the Quakers, who briefly made their home in the town before being chased out by New Netherland director general Peter Stuyvesant, who was wary of Gravesend's open acceptance of "heretical" sects.[7]

In 1654 the people of Gravesend purchased Coney Island from the local natives for about $15 worth of seashells, guns, and gunpowder.[7]

In August 1776 Gravesend Bay was the landing site of thousands of British soldiers and German mercenaries from their staging area on Staten Island, leading to the Battle of Long Island (also Battle of Brooklyn). The troops met little resistance from the Continental Army advance troops under General George Washington then headquartered in New York City (at the time limited to the tip of Manhattan Island). The battle, in addition to being the first, would prove to be the largest fought in the entire war.[7]

Popularity and success

Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries Gravesend remained a sleepy Long Island suburb. Then, with the opening of three prominent racetracks (Sheepshead Bay Race Track, Gravesend Race Track, and Brighton Beach Race Course) in the late 19th century, and the blossoming of Coney Island into a popular vacation spot, the town was transformed into a successful resort community. John Y. McKane was attributed to all of this. He was a Sheepshead Bay carpenter and contractor who rose to become the Gravesend town supervisor, chief of police, chief of detectives, fire commissioner, schools commissioner, public lands commissioner, superintendent of the Sheepshead Bay Methodist Church, head tenor of the church choir, and Santa Claus at the annual Sabbath school Christmas celebration. From the 1870s to the 1890s McKane cultivated Coney Island, which was then part of the township of Gravesend, as a pleasure ground, participating in the construction both physically and politically. As town constable, he expanded the Gravesend police force considerably and personally patrolled the beach himself often. Despite his honest beginnings, McKane quickly became a dishonest politician; he used the pretense of town permits to extort tribute from every business, large or small, on Coney Island, and while he presented himself publicly as a champion of law and order, he was actually taking a lot of money from the many brothels and gambling parlors that thrived in his bailiwick. It was during McKane’s reign that Coney Island came to be known by many as "Sodom by the Sea".

McKane also made Gravesend's politics corrupt by allowing any and all people, even non-U.S. citizens and dead people, to vote; seasonal migrant workers, criminals, and even corpses buried in the town cemetery were eligible to vote in Gravesend under McKane's new rules, and many of them voted, except for the corpses. On the eve of the 1893 election, William Gaynor, a lawyer running for Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice, decided to test McKane's methods by dispatching over 20 Republican observers to examine the Gravesend voter registries and oversee the voting in all six districts of the town, as he was entitled to do by law. However, when the observers reached Gravesend town hall at dawn on election day, McKane, along with a large group of policemen and cronies, confronted them. When the observers balked and produced injunctions from the Brooklyn Supreme Court McKane supposedly declared "injunctions don't go here" and ordered the men away. A scuffle ensued and five of the observers were beaten and arrested. This event raised great outrage.[10] Early in the following year, McKane was sentenced to six years in Sing Sing. He was released near the end of the century and died of a stroke in his Sheepshead Bay home in 1899.[11] The removal of McKane paved the way for Gravesend and Coney Island to become part of the city of Brooklyn, which they did in 1894. It also allowed George C. Tilyou, who rivaled McKane in office, to create one of Coney Island’s first amusement parks, Steeplechase Park, the opening of which ushered in Coney Island’s golden age.

Coinciding around the same time, in the late 19th century, Gravesend served as a testing ground for the Boynton Bicycle Railroad, the earliest forerunner of the monorail.[12] The BBR consisted of a single-wheeled engine that hauled two double-decker passenger cars along a single track; a second rail above the train, supported by wooden arches, kept it from tipping over. The engine and cars were only four feet wide and were capable of speeds far greater than the much bulkier standard trains. In 1889, the BBR began running a short route between the Gravesend stop of the Sea Beach Railroad (near the intersection of 86th and West Seventh Streets) and Brighton Beach in Coney Island, a distance of just over a mile. Despite the smooth and speedy ride the BBR offered riders, it ultimately failed and the test route fell into disuse, along with the Boynton train itself and the shed that was built to house it.[13]

Later years

Although Coney Island continued to be a major tourist attraction throughout the 20th century, the closing of Gravesend’s great racetracks in the century’s first decade caused the rest of the old town to recede back into obscurity. Most of it became a working- and middle-class residential Brooklyn neighborhood. In the 1950s the city constructed the 28 building Marlboro Houses, located between Avenues V and X from Stillwell Avenue to the Gravesend Rail Yards. It is run by the New York City Housing Authority.[14]

In 1982, an African-American transit worker named Willie Turks was beaten to death in Gravesend by a group of white teenagers.[15] The relationship between the predominantly African-American population of the Marlboro Houses and the predominantly white surrounding neighborhoods remained a point of tension through much of the 1980s.[16]

On December 25, 1987, white youths beat two black men in an apparent "unprovoked attack."[17] In January 1988, in protest of this event specifically and a climate of racial violence in general, Al Sharpton led a march that proceeded from the Marlboro Houses to a police station by way of Bath Avenue; along the way, the 450 marchers were met with chants of "Go back to Africa" and various racial epithets.[18]

Beginning in the 1990s, with an influx of Sephardi Jews (mostly Syrian Jews), the northeast section of the neighborhood saw the development of upscale single-family homes at prices upwards of $1 million.[19]

Education

|

|

Demographic makeup

Gravesend's earliest non-native settlers were predominantly English and Dutch. While slavery was legal in New York, the town also had a significant African American population, many of whom remained in the area even with the abolition of slavery. The now-defunct Gravesend Race Track opened on August 26, 1886 and hired mainly black workers who ended up moving into nearby homes. Later, there was a surge in Irish, Italian, and Jewish residents. Puerto Ricans and Russian, Ukrainian, Chinese, and Mexican immigrants are the most recent residents to share this neighborhood.

In 2008, The New York Times reported that the neighborhood had become particularly popular among Sephardic Jews, and was among multiple Syrian Jewish communities of the United States.[19] The New York Times also reported that in the 2012 presidential election, a precinct in Gravesend was one of the few parts of New York City carried by Mitt Romney, with 133 votes to just 3 for Barack Obama.[20]

In 2011, the surrounding area in which Gravesend is included, southern Brooklyn, had a population of over 170,000 people, with 29,436 of them living in Gravesend. The median income in this area is $48,359.[21]

References

Notes

- ^ http://www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/pdf/census/census2010/t_pl_p1_nta.pdf

- ^ Manbeck, John B. (2008), Brooklyn: Historically Speaking, Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press, ISBN 978-1-59629-500-1, p.79

- ^ "Gravesend Library"

- ^ Letter to the Editor: Gravesend, The New York Times, December 20, 1992. Accessed October 28, 2007. "As a historical archeologist specializing in the early history of New York, I can tell you that what is now the Gravesend section of Brooklyn was not named for the hometown that Lady Deborah Moody and her followers left in England, as you stated in your article about the community on Oct. 18, but by the Dutch governor-general, William Kieft. Kieft chose to name the settlement " 's'Gravesande" after the town in Holland that had been the seat of the Counts of Holland before they moved to the Hague. It means the count's sand or beach."

- ^ a b c ForgottenTour 33, Gravesend, Brooklyn, Forgotten NY. April 2008. Retrieved 2014-10-11.

- ^ 61st Precinct, NYPD.

- ^ a b c d e Gravesend, Forgotten NY

- ^ a b Lady Moody Triangle

- ^ Bradley T. Frandsen; Joan R. Olshansky; Elizabeth Spencer-Ralph (December 1979). "National Register of Historic Places Registration:Old Gravesend Cemetery". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2011-02-20.

- ^ (May 4, 1894). "A New Chapter in History" The Brooklyn Daily Eagle Page 4; "Becoming Wards One By One" The Brooklyn Daily Eagle Page 12

- ^ (September 6, 1899) "John Y. McKane Dies" The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- ^ http://www.scientificamericanpast.com/Scientific%20American%201890%20to%201899/5/lg/sci2171894.htm

- ^ (September 10, 1899) "Boynton Bicycle Railroad" The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- ^ Marlboro Houses at NYCHA

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2014/12/06/opinion/the-unreconstructed-north.html?referrer=&_r=0

- ^ Lowenstein, Roger (25 July 1988). "The Mood Gets Nasty in City Neighborhood as Racial Tension Rises". The Wall Street Journal.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ Manly, Howard (29 December 1987). "'An Unprovoked Attack': Black brothers tell of beating by whites". Newsday.

- ^ Hevesi, Dennis (3 January 1988). "Blacks, to Jeers of Whites, Protest Racism in Brooklyn". The New York Times.

{{cite journal}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ^ a b Mooney, Jake (August 10, 2008). "A Neighborhood Both Insular and Diverse". The New York Times. p. RE9.

- ^ In Manhattan, Largely Blue, One Bright Spot and a Tie for Romney, by Michael M Grynbaum, New York Times, 24 November 2012

- ^ http://www.city-data.com/neighborhood/Gravesend-Brooklyn-NY.html

Bibliography

- French, J. H. Gazetteer Of the State of New York (1860)

- Ierardi, Eric J. Gravesend: Home of Coney Island

- (August 10, 1896) Tombstone For "The Nubian" The Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- (August, 1896) "Turk is Buried with Odd Ceremonies" The New York Times

External links

Media related to Gravesend, Brooklyn at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gravesend, Brooklyn at Wikimedia Commons