Italian language in the United States

| 1910a | |

| 1920a | |

| 1930a | |

| 1940a | |

| 1960a | |

| 1970a | |

| 1980[1] | |

| 1990[2] | |

| 2000[3] | |

| 2010[4] | |

| ^a Foreign-born population only[5] | |

The Italian language has been a widely spoken language in the United States of America for more than one hundred years, due to large-scale immigration beginning in the late 19th century. Today it is the eighth most spoken language in the country.

History

The first Italian Americans began to immigrate en masse began around 1880. The first Italian immigrants, mainly from Sicily and other parts of Southern Italy, were largely men, and many planned to return to the Italy after making money in the US, so the speaker population of Italian was not always constant or continuous. Between 1890 and 1900, 655,888 Italians went to the United States, and more than 2 million between 1900 and 1910, though around 40% of these eventually returned to Italy. All told, between 1820 and 1978, some 5.3 million Italians went to the United States. Like many ethnic groups, such as the Germans in Little Germany, French Canadians in Little Canadas, and Chinese in Chinatowns, who emigrated to the Americas, the Italians often lived in ethnic enclaves, often known as Little Italies, especially in New York City, St. Louis, Chicago, Boston, and Philadelphia, and continued to speak their original languages.

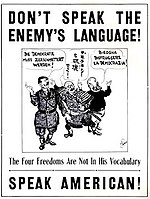

During World War II

During World War Two, use of Italian languages in the U.S. was discouraged. In addition, many Italian-Americans were interned,[6] property was confiscated,[6] and Italian-language periodicals were closed[citation needed].

The language today

| State | Italian speakers | % of all Italian speakers |

|---|---|---|

| New York | ||

| New Jersey | ||

| California | ||

| Pennsylvania | ||

| Florida | ||

| Massachusetts | ||

| Illinois | ||

| Connecticut | ||

Today, though 15,638,348 American citizens report themselves as Italian Americans, only 1,008,371 of these report speaking an Italian language at home (0.384% of the national population). But Italian is the 3rd foreign language spoken at home in US and it represents the 2nd largest ethnic market in the US behind only the Hispanic market.[8] Cities with Italian and Sicilian speaking communities include Buffalo, Chicago, Miami, New York City, Philadelphia, and St. Louis. Assimilation has played a large role in the decreasing amount of Italian speakers today. Of those who speak Italian at home in the United States, 361,245 are over the age of 65, and only 68,030 are below the age of 17.

Despite it being the fifth most studied language in higher education (college & graduate) settings throughout America,[9] the Italian language has struggled to maintain being an AP course of study in high schools nationwide. It was only in 2006 where AP Italian classes were first introduced, and they were soon dropped from the national curricula after the spring of 2009.[10] The organization which manages such curricula, the College Board, ended the AP Italian program because it was "losing money" and had failed to add 5,000 new students each year. Since the programs termination in the spring of 2009, various Italian organizations and activists have attempted to revive the course of study. For example, Margaret Cuomo, sister of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo, was the impetus for the program's birth in 2006 and is currently attempting to secure funding and teachers to reinstate the program. Also, Italian organizations have begun fundraisers to revive AP Italian. Organizations such as the National Italian American Foundation (NIAF) and Order Sons of Italy in America have made strides in collecting money, and are prepared to aid in the monetary responsibility any new AP Italian program would bring with it.

Moreover, web based Italian organizations, such as ItalianAware, have begun book donation campaigns to improve the status and representation of Italian language and Italian/ Italian American literature in New York Public Libraries. According to ItalianAware, the Brooklyn Public Library is the worst offender in New York City.[11] It has 11 books pertaining to the Italian language and immigrant experience available for checkout spread across 60 branches. That amounts to 1 book for every 6 branches in Brooklyn, which (according to ItalianAware) cannot supply the large Italian/Italian American community in Brooklyn, New York. ItalianAware aims to donate 100 various books on the Italian/ Italian American experience, written in Italian or English, to the Brooklyn Public Library by the end of 2010.

Forms of Italian

Early waves of Italian-American immigrants typically did not speak Italian language which originated from the Tuscan language, or spoke it as a second language acquired in school. Instead they typically spoke other Italo-Romance languages, particularly from Southern Italy, such as Sicilian language and Neapolitan language. Both of these languages have wide variety of dialects within them, including Salentino, Calabrese, etc. Additionally many villages may have spoken other non Italo-Romance minority languages such as Griko or the Arbëresh language. Today, the Italian language, which is most similar to the Tuscan (although not the same), is widely taught in Italian schools. Although many other minority languages have official status in Italy neither Sicilian language nor Neapolitan language are recognised by the Italian Republic. Although Italy is a signatory to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages it has not ratified the treaty. Thus limiting Italy's responsibility in the preservation of regional languages that it has not chosen to protect by domestic law.

Media

Although the Italian language is much less used today than it has been previously, there are still several Italian-only media outlets, among which are the St. Louis newspaper Il Pensiero and the New Jersey daily paper America Oggi and ICN Radio.

Il Progresso Italo Americano was edited by Carlo Barsotti (1850–1927).[12]

Arba Sicula (Sicilian Dawn) is a semiannual publication of the society of the same name, dedicated to preserving the Sicilian language. The magazine and a periodic newsletter offer prose, poetry and comment in Sicilian, with adjacent English translations.

See also

References

- ^ "Appendix Table 2. Languages Spoken at Home: 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2007". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ "Detailed Language Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for Persons 5 Years and Over --50 Languages with Greatest Number of Speakers: United States 1990". United States Census Bureau. 1990. Retrieved July 22, 2012.

- ^ "Language Spoken at Home: 2000". United States Bureau of the Census. Retrieved August 8, 2012.

- ^ "Detailed Languages Spoken at Home 2006-2008".

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ^ "Mother Tongue of the Foreign-Born Population: 1910 to 1940, 1960, and 1970". United States Census Bureau. March 9, 1999. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ^ a b [1] Archived July 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Table 5.Detailed List of Languages Spoken at Home for the Population 5 Years and Over by State: 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. February 25, 2003. Retrieved October 3, 2012.

- ^ "Newsletter". Netcapricorn.com. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ "Languages Spoken and Learned in the United States". Vistawide.com. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ Pilon, Mary (2010-05-10). "Italian Job: Resurrect the AP Exam". The Wall Street Journal.

- ^ "Literature Donations". Italianaware.com. Retrieved 2015-10-26.

- ^ "Verdi Monument - Historical Sign". Nycgovparks.org. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

Further reading

- "Publications in Foreign Languages: Italian", Ayer & Son's American Newspaper Annual, Philadelphia: N. W. Ayer & Son, 1907

{{citation}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) (help) - Peter R. Eisenstadt, Laura-Eve Moss, ed. (2005). "Ethnic Press: Italian". Encyclopedia Of New York State. Syracuse University Press. ISBN 9780815608080.