Jerry Brown: Difference between revisions

m Reverted edits by 156.3.74.84 (talk) to last revision by JamesBWatson (HG) |

|||

| Line 52: | Line 52: | ||

== Early life and education == |

== Early life and education == |

||

Bieber was born on March 1, 1994, in London, Ontario[12] and was raised in Stratford, Ontario. Bieber's mother, Pattie Mallette, was 18 years old when she became pregnant with her son. Mallette, who worked a series of low-paying office jobs, raised Bieber as a single mother. However, Bieber maintains contact with his father, Jeremy Bieber.[13][14] As he grew, Bieber taught himself to play the piano, drums, guitar, and trumpet.[15] In early 2007, when he was twelve, Bieber sang Ne-Yo's "So Sick" for a local singing competition in Stratford and placed second.[5] Mallette posted a video of the performance on YouTube for their family and friends to see. She continued to upload videos of Bieber singing covers of various R&B songs, and Bieber's popularity on the site grew.[9] |

|||

Brown was born in [[San Francisco, California|San Francisco]], California, the only son of four siblings born to [[Bernice Layne Brown]] and former San Francisco lawyer, [[district attorney]] and later California governor [[Edmund G. Brown|Edmund G. "Pat" Brown, Sr.]]<ref name=Arnold>{{cite book |title = California after Arnold | last=Cummings, Reddy| first=Stephen, Patrick| publisher = Algora Publishing |date = September 14, 2009| page = 179| isbn=978-0875867397 }}</ref> He graduated from [[St. Ignatius College Preparatory|St. Ignatius High School]] in 1955 and studied at [[Santa Clara University]]. In 1956, he entered Sacred Heart Novitiate, a [[Society of Jesus|Jesuit]] [[seminary]], intending to become a [[Roman Catholicism in the United States|Catholic]] [[priest]]. However, Brown left the seminary and entered [[University of California, Berkeley]], where he graduated with a [[Bachelor of Arts]] in Classics in 1961. Brown went on to [[Yale Law School]] and graduated with a [[Juris Doctor]] in 1964.<ref name="Arnold" /> |

|||

After law school, Brown worked as a [[law clerk]] for [[Supreme Court of California]] Justice [[Mathew Tobriner]] and studied in [[Mexico]] and [[Latin America]]. |

|||

== Legal career and entrance into politics == |

== Legal career and entrance into politics == |

||

Revision as of 20:24, 3 November 2010

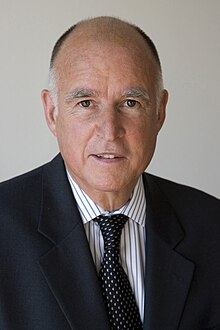

Jerry Brown | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor-elect of California | |

| Assuming office January 3, 2011 | |

| Lieutenant | Gavin Newsom |

| Succeeding | Arnold Schwarzenegger |

| 34th Governor of California | |

| In office January 6, 1975 – January 3, 1983 | |

| Lieutenant | Mervyn M. Dymally (1975–1979) Mike Curb (1979–1983) |

| Preceded by | Ronald Reagan |

| Succeeded by | George Deukmejian |

| 31st California Attorney General | |

| Assumed office January 9, 2007 | |

| Governor | Arnold Schwarzenegger |

| Preceded by | Bill Lockyer |

| 44th Mayor of Oakland | |

| In office January 4, 1999 – January 8, 2007 | |

| Preceded by | Elihu Harris |

| Succeeded by | Ron Dellums |

| 24th Secretary of State of California | |

| In office January 4, 1971 – January 6, 1975 | |

| Governor | Ronald Reagan |

| Preceded by | H. P. Sullivan (Acting) |

| Succeeded by | March Fong Eu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 7, 1938 San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | Anne Gust |

| Residence(s) | Oakland, California, U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of California, Berkeley Yale Law School |

Edmund Gerald "Jerry" Brown, Jr. (born April 7, 1938) is an American politician. Brown is currently serving as the 31st Attorney General of the state of California. He was elected to a third, non-consecutive term as Governor on November 2, 2010. Governor-elect Brown is scheduled to take office in January 2011, 28 years after his last term ended.

Brown was elected three times as Governor in 1974, 1978, and 2010. During his first term (as California's 34th Governor), he was the youngest Governor in modern California, and in 2011 (as California's 39th Governor) will become its oldest. In 1990, California voters passed a law limiting governors and other statewide elected officials to two four-year terms, but Brown's prior service was not counted under the term-limits law, because he served his first two terms before the law was passed. [2] Thus, if he completes his third term, he will become the longest-serving Governor in the state's past and future, unless term limits are repealed at some point. No one else will be able to serve longer than Brown is likely to serve, due to the term limits. (Earl Warren served 2 1/2 terms from 1943 to 1953.)[3]

Brown has been elected to a number of state and local offices, spanning terms on the Los Angeles Community College District Board of Trustees (1969–1971), as California Secretary of State (1971–1975), as Governor of California (1975–1983), chairman of the California Democratic Party (1989–1991), as well as the Mayor of Oakland (1999–2007).

Brown sought the Democratic nominations for President of the United States in 1976, 1980, and 1992, as well as the United States Senate in 1982 but was unsuccessful in these attempts.

Early life and education

Bieber was born on March 1, 1994, in London, Ontario[12] and was raised in Stratford, Ontario. Bieber's mother, Pattie Mallette, was 18 years old when she became pregnant with her son. Mallette, who worked a series of low-paying office jobs, raised Bieber as a single mother. However, Bieber maintains contact with his father, Jeremy Bieber.[13][14] As he grew, Bieber taught himself to play the piano, drums, guitar, and trumpet.[15] In early 2007, when he was twelve, Bieber sang Ne-Yo's "So Sick" for a local singing competition in Stratford and placed second.[5] Mallette posted a video of the performance on YouTube for their family and friends to see. She continued to upload videos of Bieber singing covers of various R&B songs, and Bieber's popularity on the site grew.[9]

Legal career and entrance into politics

Returning to California, Brown took the state bar exam and passed on his second attempt.[4] Brown then settled in Los Angeles, California and joined the law firm of Tuttle & Taylor. In 1969, he ran for the newly created Los Angeles Community College Board of Trustees, which oversaw community colleges in the city, and placed first in a field of 124.[5]

In 1970 Brown was elected California Secretary of State. He argued before the California Supreme Court and won against Standard Oil of California, International Telephone and Telegraph, Gulf Oil, and Mobil for election law violations (Brown vs. Superior Court).[5] In addition Brown forced legislators to comply with campaign disclosure laws. While holding this office, he discovered Richard Nixon’s use of falsely notarized documents to earn a tax deduction; Nixon was then serving as U.S. president. Brown also drafted and helped to pass the California Fair Political Practices Act which established the California Fair Political Practices Commission.

Governor of California (1975–1983)

First term

In 1974, Brown was elected Governor of California. He succeeded Republican Governor Ronald Reagan, who had planned on retiring from office after serving two terms. Reagan had become governor after defeating Brown's father, Edmund G. "Pat" Brown, Sr., in the 1966 election. Jerry Brown took office on January 6, 1975.[6]

Upon taking office, Brown gained a reputation as a fiscal conservative.[7][8] The American Conservative later noted he was "much more of a fiscal conservative than Governor Reagan."[8] His fiscal restraint resulted in one of the biggest budget surpluses in state history, roughly $5 billion.[8][9][10] For his personal life, Brown refused many of the privileges and perks of the office, forgoing the newly constructed governor's residence and instead renting a modest apartment at the corner of 14th and N Streets, adjacent to Capitol Park in downtown Sacramento.[11] Instead of riding as a passenger in a chauffeured limousine as previous governors had done, Brown drove to work in a Plymouth Satellite sedan.[12][13]

During his two-term, eight-year governorship, Brown had a strong interest in environmental issues. Brown appointed J. Baldwin to work in the newly created California Office of Appropriate Technology, Sim Van der Ryn as State Architect, and Stewart Brand as Special Advisor. He appointed John Bryson, later the CEO of Southern California Edison Electric Company and a founding member of the Natural Resources Defense Council, chairman of the California State Water Board in 1976. Brown also reorganized the California Arts Council, boosting its funding by 1300 percent and appointing artists to the council [5] and appointed more women and minorities to office than any other previous California governor.[5] In 1977 he sponsored the "first-ever tax incentive for rooftop solar" among many environmental intiatives.[14]

In 1975, Brown obtained the repeal of the "depletion allowance", a tax break for the state's oil industry, despite the efforts of the lobbyist Joe Shell, a former intraparty rival to Richard M. Nixon. The decisive vote against the allowance was cast in the California State Senate by the usually pro-business Republican Senator Robert S. Stevens. Shell claimed that Stevens had promised him that he would support keeping the allowance: "He had shaken my hand and told me he was with me." Brown later rewarded Stevens with a judicial appointment, but Stevens was driven from the bench for making salacious telephone calls.[15]

Like his father, Brown strongly opposed the death penalty and vetoed it as Governor, which the legislature overrode in 1977. He also appointed judges who opposed capital punishment. One of these appointments, Rose Bird as the Chief Justice of the California Supreme Court, was recalled in 1986 by voters angry at her opposition to the death penalty. She and two other Brown appointed justices were the first such removals in California history.[16] In 1960, he had lobbied his father, then Governor, to spare the life of Caryl Chessman and reportedly won a 60-day stay for him.[17][18]

He was both in favor of a Balanced Budget Amendment and opposed to Proposition 13, the latter of which would decrease property taxes and greatly reduce revenue to cities and counties.[8][19] When Proposition 13 passed in June of 1978, he heavily cut state spending and, along with the Legislature, spent much of the $5 billion surplus to meet the proposition's requirements and help offset the revenue losses which made cities, counties and schools more dependent on the state.[8][9][19] His actions in response to the proposition earned him praise from Proposition 13 author Howard Jarvis who went as far to make a television commercial for Brown just before his successful reelection bid in 1978.[19][20]

The controversial proposition immediately cut tax revenues and required a two-thirds supermajority to raise taxes.[21] Proposition 13 "effectively destroyed the funding base of local governments and school districts, which thereafter depended largely on Sacramento for their revenue".[22] Max Neiman, a professor at the Institute of Government Studies at University of California, Berkeley, credited Brown in "bailing out local government and school districts" but felt it was harmful "because it made it easier for people to believe that Proposition 13 wasn't harmful."[14]

Second term

Some notable figures were given priority, correspondence access to him in either advisory or personal roles. These included, United Farm Workers of America founder Cesar Chavez, Hewlett-Packard co-founder David Packard, labor leader Jack Henning, and Charles Manatt, then-Chairman of the California State Democratic Party. Mail was routed as VIP to be delivered directly to the governor, however, it is unclear as to exactly how long this may have occurred.[23]

In 1979 San Francisco punk band the Dead Kennedys' first single, "California Über Alles", was released; it was performed from the perspective of then-governor Brown painting a picture of a hippie-fascist state, satirizing what they considered his mandating of liberal ideas in a fascist manner, commenting on what lyricist Jello Biafra saw as the corrosive nature of power. The imaginary Brown had become President Brown presiding over secret police and gas chambers. Biafra later said in an interview with Nardwuar that he now feels differently about Brown; as it turned out Brown was not as bad as Biafra thought he would be, and subsequent songs have been written about other politicians deemed worse.[24]

Brown proposed the establishment of a state space academy and the purchasing of a satellite that would be launched into orbit to provide emergency communications for the state —- a proposal similar to one that was indeed eventually adopted. In 1979, an out-of-state columnist, Mike Royko, then at the Chicago Sun-Times, picked up on the nickname from Brown's girlfriend at the time, Linda Ronstadt, who was quoted in a 1978 Rolling Stone magazine interview humorously calling him "Moonbeam".[25][26] A year later Royko expressed his regret for publicizing the nickname[27], and in 1991 Royko disavowed it entirely, proclaiming Brown to be just as serious as any other politician.[28][29]

Brown chose not to run for a third term in 1982 and instead ran for the United States Senate, but lost to then San Diego mayor Pete Wilson. He was succeeded as governor by George Deukmejian, then the Attorney General of California, in 1982.

1976 Democratic presidential primary

While serving as governor, Brown twice ran for the Democratic nomination for president. The first time, in 1976, Brown entered the race in March after the primary season had begun, and over a year after some candidates had started campaigning. He declared: "The country is rich, but not so rich as we have been led to believe. The choice to do one thing may preclude another. In short, we are entering an era of limits."[30][31]

Brown's name began appearing on primary ballots in May and he won big victories in Maryland, followed by Nevada, and his home state of California.[32] Brown missed the deadline in Oregon, but he ran as a write-in candidate and finished a strong third behind Carter and Senator Frank Church of Idaho, another late candidate. Brown is often credited with winning the New Jersey and Rhode Island primaries, but in reality, uncommitted slates of delegates that Brown advocated in those states finished first. With support from Louisiana Governor Edwin Edwards Brown won a majority of delegates at the Louisiana delegate selection convention; thus Louisiana was the only southern state to not support Southerners Carter or Alabama Governor George Wallace. Despite this success, he was unable to stall Carter's momentum, and his rival was nominated on the first ballot at the 1976 Democratic National Convention. Brown finished third with roughly 300 delegate votes, narrowly behind Congressman Morris Udall and well behind Carter. Brown's name was placed in nomination by United Farm Workers President Cesar Chavez.

1980 Democratic presidential primary

In 1980, Brown challenged Carter for renomination. His candidacy had been anticipated by the press ever since he won re-election as governor in 1978 over the Republican Evelle Younger by the biggest margin in California history, 1.3 million votes. But Brown had trouble gaining traction in both fundraising and polling for the presidential nomination. This was widely believed to be the result of the more prominent candidacy of liberal icon Senator Ted Kennedy of Massachusetts.

Brown's 1980 platform, which he declared to be the natural result of combining Buckminster Fuller's visions of the future and E.F. Schumacher's theory of "Buddhist economics", was much expanded from 1976. Gone was his "era of limits" slogan, replaced by a promise to, in his words, "Protect the Earth, serve the people, and explore the universe." Three main planks of his platform were a call for a constitutional convention to ratify the Balanced Budget Amendment, a promise to increase funds for the space program, and, in the wake of the 1979 Three Mile Island accident, opposition to nuclear power. On the subject of the 1979 energy crisis, Brown decried the "Faustian bargain" that he claimed Carter had entered into with the oil industry, and declared that he would greatly increase federal funding of research into solar power. He endorsed the idea of mandatory non-military national service for the nation's youth, and suggested that the Defense Department cut back on support troops while beefing up the number of combat troops. He described the health care industry as a "high priesthood" engaged in a "medical arms race" and called for a market-oriented system of universal health care.

As his campaign began to attract more and more members of what some more conservative commentators described as "the fringe", including activists like Jane Fonda, Tom Hayden, and Jesse Jackson, Brown's polling numbers began to suffer. He received only 10% of the vote in the New Hampshire primary and he was soon forced to announce that his decision to remain in the race would hinge on a good showing in the Wisconsin primary. Although he had polled well there throughout the primary season, an attempt to film a live speech in Madison, the state's capital, into a special effects-filled, 30-minute commercial (produced and directed by Francis Ford Coppola) was disastrous.[33]

1980s

In 1982, Brown chose not to seek a third term as Governor. Instead, he ran for the U.S. Senate for the seat being vacated by Republican S.I. Hayakawa. Brown was defeated by Republican San Diego Mayor Pete Wilson by a margin of 52% to 45%. After his Senate defeat Brown was left with few political options.[34] Republican George Deukmejian, a Brown critic, narrowly won the governorship in 1982, succeeding Brown, and was reelected overwhelmingly in 1986. After his Senate defeat in 1982, many considered Brown's political career to be over.[34] Brown traveled to Japan to study Buddhism, studying with Christian/Zen practitioner Hugo Enomiya-Lassalle under Yamada Koun-roshi. In an interview he explained, "Since politics is based on illusions, zazen definitely provides new insights for a politician. I then come back into the world of California and politics, with critical distance from some of my more comfortable assumptions."[35] He also visited Mother Teresa in Calcutta, India, where he ministered to the sick in one of her hospices.[36] He explained, "Politics is a power struggle to get to the top of the heap. Calcutta and Mother Teresa are about working with those who are at the bottom of the heap. And to see them as no different than yourself, and their needs as important as your needs. And you're there to serve them, and doing that you are attaining as great a state of being as you can."[35]

Upon his return from abroad in 1988, he announced that he would stand as a candidate to become chairman of the California Democratic Party. Brown won the position in 1989 against investment banker Steve Westly.[37] Although Brown greatly expanded the party's donor base and enlarged its coffers, with a focus on grassroots organizing and get out the vote drives, he was criticized for not spending enough money on TV ads, which was felt to have contributed to Democratic losses in several close races in 1990. In early 1991, Brown abruptly resigned his post and announced that he would run for the Senate seat held by the retiring Alan Cranston. Although Brown consistently led in the polls for both the nomination and the general election, he abandoned the campaign, deciding instead to run for the presidency for a third time.

1992 Democratic presidential primary

When he announced his intention to run for president against President George H.W. Bush, many in the media and his own party dismissed his campaign as having little chance of gaining significant support. Ignoring them, Brown embarked on an ultra-grassroots campaign to, in his words, "take back America from the confederacy of corruption, careerism, and campaign consulting in Washington".[38] Brown tapped into a populist streak in the Democratic Party.

In his stump speech, first used while officially announcing his candidacy on the steps of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Brown told listeners that he would only be accepting campaign contributions from individuals and that he would accept no contribution over $100.[23] Continuing with his populist reform theme, he assailed what he dubbed "the bipartisan Incumbent Party in Washington" and called for term limits for members of Congress. Citing various recent scandals on Capitol Hill, particularly the recent House banking scandal and the large congressional pay-raises from 1990, he promised to put an end to Congress being a "Stop-and-Shop for the moneyed special interests".

As he campaigned in various primary states, Brown would eventually expand his platform beyond a policy of strict campaign finance reform. Although he would focus on a variety of issues throughout the campaign, most especially his endorsement of living wage laws and his opposition to free trade agreements such as North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), he mostly concentrated on his tax policy, which had been created specifically for him by Arthur Laffer, the famous supporter of supply-side economics who created the Laffer curve. This plan, which called for the replacement of the progressive income tax with a flat tax and a value added tax, both at a fixed 13% rate, was decried by his opponents as regressive. Nevertheless, it was endorsed by The New York Times, The New Republic, and Forbes, and its raising of taxes on corporations and elimination of various loopholes which tended to favor the very wealthy, proved to be popular with voters. This was, perhaps, not surprising, as various opinion polls taken at the time found that as many as three-quarters of all Americans believed the current tax code to be unfairly biased toward the wealthy.

Quickly realizing that his campaign's limited budget meant that he could not afford to engage in conventional advertising, Brown began to use a mixture of alternative media and unusual fund raising techniques. Unable to pay for actual commercials, Brown used frequent cable television and talk radio interviews as a form of free media to get his message to the voters. In order to raise funds, he purchased a toll-free telephone number, (the same number is still in use by Brown) which adorned all of his campaign paraphernalia.[39] During the campaign, Brown's repetition of this number combined with the moralistic language used, led some to describe him as a "political televangelist" with a "anti-politics gospel".[40]

Despite poor showings in the Iowa caucus (1.6%) and the New Hampshire primary (8.0%), Brown soon managed to win narrow victories in Maine, Colorado, Nevada, Alaska, and Vermont, but he continued to be considered an also-ran for much of the campaign. It was not until shortly after Super Tuesday, when the field had been narrowed to Brown, former Senator Paul Tsongas of Massachusetts, and frontrunning Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas, that Brown began to emerge as a major contender in the eyes of the press. On March 17, Brown forced Tsongas from the race when he received a strong third-place showing in the Illinois primary and then defeated the senator for second place in the Michigan primary by a wide margin. Exactly one week later, he cemented his position as a major threat to Clinton when he eked out a narrow win in the bitterly-fought Connecticut primary.

As the press focused on the primaries in New York and Wisconsin, which were both to be held on the same day, Brown, who had taken the lead in polls in both states, made a gaffe: he announced to an audience of various leaders of New York City's Jewish community that, if nominated, he would consider the Reverend Jesse Jackson as a vice-presidential candidate.[41] Jackson, who had made a pair of comments that were perceived to be anti-Semitic about Jews in general and New York City's Jews in particular while running for president in 1984, was still despised in Jewish communities. Jackson also had ties to Louis Farrakhan, who said Judaism was a "gutter religion," and with Yasir Arafat, the chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization.[41] Brown's polling numbers suffered. On April 7, he lost narrowly to Bill Clinton in Wisconsin (37–34), and dramatically in New York (41–26).

Although Brown continued to campaign in a number of states, he won no further primaries. Although overwhelmingly outspent he won upset victories in seven states and his votes won to money raised ratio was by far the best of any candidate in the race.[42] He still had a sizable number of delegates, and a big win in his home state of California would deprive Clinton of sufficient support to win the Democratic nomination, possibly bringing about a brokered convention. After nearly a month of intense campaigning and multiple debates between the two candidates, Clinton managed to defeat Brown in this final primary by a margin of 48% to 41%. Although he did not win the nomination, Brown was able to boast of one accomplishment: At the following month's Democratic National Convention, he received the votes of 596 delegates on the first ballot, more than any other candidate but Clinton. He spoke at the convention, and to the national viewing audience, yet without endorsing Clinton, through the device of seconding his own nomination. There was animosity between the Brown and Clinton campaigns, and Brown was the first political figure to criticize Bill Clinton over what became the Whitewater controversy.[39]

Mayor of Oakland (1999-2007)

What was to become Brown's re-emergence into politics after sixteen years was also the start of the renaissance of Oakland, California, a down-on-its-luck "overwhelmingly minority city of 400,000."[43] Brown ran as an independent "having left the Democratic Party, blasting what he called the 'deeply corrupted' two-party system."[43] Prior to taking office, Brown campaigned to get the approval of the electorate to convert Oakland's weak mayor political structure, which structured the mayor as chairman of the city council and official greeter, to a strong mayor structure, where the mayor would act as chief executive over the nonpolitical city manager and thus the various city departments, and break tie votes on the Oakland City Council.[43] He won with 59% of the vote in a field of ten candidates.[43] The political left had hoped for some of the more progressive politics from Brown's earlier governorship, but found Brown "more pragmatic than progressive, more interested in downtown redevelopment and economic growth than political ideology".[44]

The city was rapidly losing residents and businesses, and Brown is credited with starting the revitalization of the city using his connections and experience to lessen the economic downturn, while attracting $1 billion of investments, including refurbishing Fox Theater (Oakland), the Port of Oakland and Jack London Square.[43] The downtown district was losing retailers, restaurateurs and residential developers, and Brown sought to attract thousands of new residents with disposable income to revitalize the area.[45] Brown continued his predecessor Elihu Harris's public policy of supporting downtown housing development in the area defined as the Central Business District in Oakland's 1998 General Plan.[46] Since Brown worked toward the stated goal of bringing an additional 10,000 residents to Downtown Oakland, his plan was known as "10K." It has resulted in redevelopment projects in the Jack London District, where Brown purchased and later sold an industrial warehouse which he used as a personal residence,[43] and in the Lakeside Apartments District near Lake Merritt. The 10k plan has touched the historic Old Oakland district, the Chinatown district, the Uptown district, and Downtown. Brown surpassed the stated goal of attracting 10,000 residents according to city records, and built more affordable housing than previous mayoral administrations.[45]

He had campaigned on fixing Oakland's schools, but "bureaucratic battles" dampened his efforts. He concedes he never had control of the schools, and his reform efforts were "largely a bust".[43] He focused instead on creating of two charter schools, the Oakland School for the Arts and the Oakland Military Institute.[43] Another area of disappointment was overall crime. Brown sponsored nearly two dozen crime initiatives to reduce the crime rate.[47] Although he did decrease crime by 13 percent overall, and increased the police force, the city still suffered a "57 percent spike in homicides his final year in office, to 148".[43] Critics were unable to convince voters in the 2006 race for attorney general that he was responsible for the increased crime rate.[43]

Attorney General (2007–2010)

In 2004, Brown expressed interest to be a candidate for the Democratic nomination for Attorney General of California in the 2006 election. In May 2004, he formally filed. He had an active Democratic primary opponent, Los Angeles City Attorney Rocky Delgadillo. who put most of his money into TV ads attacking Brown and spent $4.1 million on the primary campaign. Brown defeated Delgadillo, 63% to 37%. In the general election, Brown defeated Republican State Senator Charles Poochigian 56.3% to 38.2%, which was one of the largest margins of victory in any statewide California race.[48] In the final weeks leading up to Election Day, Brown's eligibility to run for Attorney General was challenged in what Brown called a "political stunt by a Republican office seeker" (Contra Costa County Republican Central Committee chairman and state GOP vice-chair candidate Tom Del Beccaro). Plaintiffs claimed Brown did not meet eligibility according to California Government Code §12503, "No person shall be eligible to the office of Attorney General unless he shall have been admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of the state for a period of at least five years immediately preceding his election or appointment to such office." Legal analysts called the lawsuit frivolous because Brown was admitted to practice law in the State of California on June 14, 1965, and had been so admitted to practice ever since. Although ineligible to practice law because of his voluntary inactive status in the State Bar of California from January 1, 1997 to May 1, 2003, he was nevertheless still admitted to practice. Because of this difference the case was eventually thrown out.[49][50]

As Attorney General, Brown is obligated to represent the state in fighting death penalty appeals and stated that he will follow the law, regardless of his personal beliefs against capital punishment.[17] Some legal scholars note that under current law the Attorney General does not have much discretion over death penalty cases.[51] Capital punishment by lethal injection was halted in California by federal judge Jeremy D. Fogel until new facilities and procedures were put into place.[52] Brown moved to resume capital punishment in 2010 with the execution of Albert Greenwood Brown after the lifting of a statewide moratorium by a California court.[53] Brown's Democratic campaign, which pledged to "enforce the laws" of California, denied any connection between the case and the gubernatorial election. Prosecutor Rod Pacheco, who supports Republican opponent Meg Whitman, said that it would be unfair to accuse Jerry Brown of using the execution for political gain as they never discussed the case.[54]

In June 2008 Brown filed a fraud lawsuit claiming mortgage lender Countrywide Financial engaged in "unfair and deceptive" practices to get homeowners to apply for risky mortgages far beyond their means."[55][56] Brown accused the lender of breaking the state's laws against false advertising and unfair business practices. The lawsuit also claims the defendant misled many consumers by misinforming them about the workings of certain mortgages such adjustable-rate mortgages, interest-only loans, low-documentation loans and home-equity loans while telling borrowers they would be able to refinance before the interest rate on their loans adjusted.[57] The suit was settled in October 2008 after Bank of America acquired Countrywide. The settlement involves the modifying of troubled 'predatory loans' up to $8.4 billion dollars.[58]

Proposition 8, a contentious voter-approved amendment to the state constitution that banned same-sex marriage was upheld in May 2009 by the California Supreme Court.[59][60] In August 2010, the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California ruled that Proposition 8 violated the Due Process and the Equal Protection Clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.[61] Brown and Republican Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger have declined to appeal the ruling.[62] The state appeals court declined to order the men to defend the proposition and scheduled a hearing in early December to see if there is "legal standing to appeal Walker's ruling."[63]

2010 gubernatorial campaign

Brown's Republican opponent in the election was former eBay president Meg Whitman. On October 3, 2010, Brown was endorsed by the Los Angeles Times, The Sacramento Bee, and the San Francisco Chronicle.[64][65][66] He was endorsed by the San Jose Mercury News on October 10.[67] He was also endorsed by the Service Employees International Union - CA. [68]

Brown announced his candidacy for governor on March 2, 2010.[69] First indicating his interest in early 2008, Brown formed an exploratory committee in order to seek a third term as Governor in 2010, following the expiration of Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's current term.[70] The fact that he has served two terms already does not affect him because Proposition 140 does not apply to those who had served as public officials before the law passed in 1990, as provided in Article 20, Section 7 of the California Constitution.[71]

On November 2, 2010, Jerry Brown successfuly won the governorship.[72] Brown defied "both a crushing conservative wave sweeping the nation and a tsunami of spending by his billionaire opponent", to make an historic return to the office he left 28 years earlier.[73]

Electoral history

- 1970: Elected as California Secretary of State with 51% of the vote

- 1974: Won Democratic primary for Governor of California with 38% of the vote

- 1974: Elected as Governor of California with 50% of the vote

- 1976: Lost Democratic presidential primaries to Jimmy Carter with a nationwide 15% of the vote

- 1978: Won Democratic primary for Governor of California as an incumbent, with 78% of the vote

- 1978: Reelected as Governor of California with 56% of the vote

- 1980: Lost Democratic presidential primaries to Jimmy Carter, finishing third with a nationwide 3% of the vote

- 1982: Won Democratic primary for Senator from California with 51% of the vote

- 1982: Lost California Senate election to Pete Wilson, with 45% of the vote

- 1992: Lost Democratic presidential primaries to Bill Clinton, finishing third with a nationwide 20% of the vote

- 1998: Elected Mayor of Oakland with 59% of the vote

- 2002: Reelected Mayor of Oakland with 63% of the vote

- 2006: Won Democratic primary for California Attorney General with 63% of the vote

- 2006: Elected California Attorney General with 56% of the vote

- 2010: Won Democratic primary for Governor of California with 84% of the vote

- 2010: Elected Governor of California with 53% of the vote

Personal life

A bachelor as governor and mayor, Brown achieved some prominence in gossip columns for dating high-profile women, the most notable of whom was the singer Linda Ronstadt.[74]

Beginning in 1995, Brown hosted a daily call-in talk show on the local Pacifica Radio station, KPFA-FM, in Berkeley broadcast to major US markets.[35] Both the radio program and Brown's political action organization, based in Oakland, were called We the People.[35] His programs, usually featuring invited guests, generally explored alternative views on a wide range of social and political issues, from education and health care to spirituality and the death penalty.[35]

Brown has a long term friendship with Jacques Barzaghi, his aide-de-camp, whom he met in the early 1970s and put on his payroll. Author Roger Rapaport wrote in his 1982 Brown biography California Dreaming: The Political Odyssey of Pat & Jerry Brown, "this combination clerk, chauffeur, fashion consultant, decorator and trusted friend had no discernible powers. Yet late at night, after everyone had gone home to their families and TV consoles, it was Jacques who lingered in the Secretary (of state's) office." Barzaghi and his sixth wife Aisha lived with Brown in the warehouse in Jack London Square; Barzaghi was brought into Oakland city government upon Brown's election as mayor, where Barzaghi first acted as the mayor's armed bodyguard. Brown later rewarded Barzaghi with high-paying city jobs, including "Arts Director." Brown dismissed Barzaghi in July 2004.[75]

In March 2005, Brown announced his engagement to his girlfriend since 1990, Anne Gust, former chief counsel for The Gap.[citation needed] They were married on June 18 in a ceremony officiated by Senator Dianne Feinstein in the Rotunda Building in downtown Oakland. They had a second, religious ceremony later in the day in the Roman Catholic church in San Francisco where Brown's parents had been married. Brown and Gust live in the Oakland Hills in a home purchased for $1.8 million, as reported by The Huffington Post.[76]

References

- ^ Pack, Robert (1978). Jerry Brown, the philosopher-prince. Stein and Day, ISBN 978-0-8128-2437-7 "a story appeared in the New York Times on May 16, 1976, reporting that Brown 'now admits he is no longer a practicing Roman Catholic.' The Times story prompted a member of the staff of The Monitor, the newspaper of the archdiocese of San Francisco, to query Brown, whose answer was, "I was born a Catholic. I was raised a Catholic. I am a Catholic."

- ^ Term Limits

- ^ Earl Warren Biography

- ^ Dolan, Maura (21 February 2006). "A High Bar for Lawyers". Los Angeles Times. p. 3. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ a b c d "Edmund G. Brown, Jr". California Office of the Attorney General. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ Brown, Jerry (1975-01-06). "Inaugural Address". Governors of California. State of California. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ Shoemaker, Dick (August 23, 1975). "Gov. Brown, California". ABC News.

- ^ a b c d e Walker, Jesse (November 1, 2009). "Five Faces of Jerry Brown". American Conservative.

- ^ a b Young, Samantha (September 27, 2010). "Brown, Whitman prepare for gubernatorial debate". Associated Press / San Jose Mercury News.

{{cite news}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ "A vote for experience over a big leap of faith". San Francisco Chronicle. October 3, 2010.

- ^ Bachelis 1986, p. 68

- ^ Steinhauer, Jennifer (December 5, 2009). "4 Ex-Governors Craving Jobs of Yore". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ "Jerry Brown Meets Sgt. York & Flavor Flav". CalBuzz. December 10, 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2010.

- ^ a b By COLIN SULLIVAN of Greenwire (2010-10-08). "Jerry Brown's Environmental Record Runs Deep". NYTimes.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Walters, Dan (2008-04-08). "For Joe Shell, character trumped ideology in California politics". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on 2008-04-23.

- ^ Purdum, Todd (1999-12-06). "Rose Bird, Once California's Chief Justice, Is Dead at 63". New York Times. pp. 1–3. Retrieved 2010-10-29.

- ^ a b Zamora, Jim Herron (2006-06-02). "Brown's rivals question commitment to death penalty". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ Lewis, Anthony (1989-08-20). "He Was Their Last Resort". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-19.

- ^ a b c Skelton, George (March 4, 2010). "The parable of 'Jerry Jarvis'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Harris, Don (October 10, 1978). NBC News.

{{cite news}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ McKinley, Jesse (March 13, 2010). "A Candidate Finds Much Changed, and Little". The New York Times.

- ^ Meyerson, Harold (May 28, 2009) "How the Golden State Got Tarnished." Washington Post. . Retrieved 7-22-09.

- ^ a b Chase Davis, California Watch (October 13, 2010). "List reveals who had Jerry Brown's ear in '79". Sfgate.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Ruskin, John (2002). "Nardwuar the Human Serviette vs Jello Biafra". Nardwuar. Retrieved 2009-04-21.

- ^ Zach Friend: California Governor's Race: Why Moonbeam Will Win

- ^ Royko, Mike (April 23, 1979). "OUR LATEST EXPORT: GOV. MOONBEAM--ER, BROWN". Los Angeles Times. p. C11.

- ^ Royko, Mike (August 17, 1980). "Gov. Moonbeam Has Landed". Los Angeles Times. p. E5.

- ^ McKinley, Jesse (March 7, 2010). "How Jerry Brown Became 'Governor Moonbeam'". The New York Times. p. WK5. Retrieved March 8, 2010.

- ^ Royko, Mike (September 10, 1991). "Time to eclipse the 'moonbeam' label". Las Vegas Review-Journal. p. 6.b.

By now, the label had surely faded away, especially since Brown is obviously a serious man and every bit as normal as the next candidate, if not more so.

- ^ Nolte, Carl (May 30, 1999). "California rides the wave". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ Schmalz, Jeffrey (March 30, 1992). "THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: Candidate's Record; Brown Firm on What He Believes, But What He Believes Often Shifts". The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ^ View archival news footage of Brown's campaign speech in Union Square, San Francisco on May 25th 1976: http://diva.sfsu.edu/collections/sfbatv/bundles/189401.

- ^ Lakeland Ledger - Google News Archive Search

- ^ a b "Brown beaten in Senate bid". Eugene Register-Guard. Associated Press. November 2, 1982. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Branfman, Fred (1996-06-03). "The SALON Interview: Jerry Brown - Salon.com". Dir.salon.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ "Jerry Brown: On a quest for change". The Times-News. Associated Press. March 6, 1992. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ "JERRY BROWN WINS STATE PARTY POST". The New York Times. February 13, 1989. Retrieved 6 October 2010.

- ^ The CQ guide to current American government, Volume 49.

- ^ a b Bradley, William (25 May 2008). "The OTHER Big Problem With Hillary's Notorious Remarks". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ "Brown Enters Race as Leader Against 'Corrupt Politics'", Associated Press, Oct 22, 1991. Page A3.

- ^ a b Dowd, Maureen (1992-04-03). "THE 1992 CAMPAIGN - Brown - Candidate Is Tripped Up Over Alliance With Jackson - NYTimes.com". New York State: Select.nytimes.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ "Mike Lux: A Modern Populist Movement". Huffingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Jerry Brown's years as Oakland mayor set stage for political comeback - San Jose Mercury News". Mercurynews.com. 2010-08-29. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Johnson, Chip (2005-10-07). "City awaits word from Dellums - SFGate". Articles.sfgate.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ a b Heredia, Christopher (2006-02-19). "CAMPAIGN 2006: Oakland Mayor / Candidates agree on increasing housing / They differ on how to assist middle-, low-income families - SFGate". Articles.sfgate.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Robert Gammon (3 January 2007). "Inflating the Numbers, The Brown administration came very close on the 10K Plan. So why the grade inflation?". East Bay Express.

- ^ Johnson, Chip (2010-03-09). "Jerry Brown is ex-mayor, not Gov. Moonbeam - SFGate". Articles.sfgate.com. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ McPherson, Bruce. ""Statement of Vote", 2006" (PDF). Elections & Voter Information. California Secretary of State's Office. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ "Editorial: GOP Volunteers Disgrace Party by Opposition to Kennard, Suit Against Brown". Metropolitan News-Enterprise. October 23, 2006. p. 6. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ Richman, Josh (February 10, 2007). "Judge dismisses suit against Brown". InsideBayArea.com. Retrieved 2007-06-12.

- ^ "CAMPAIGN 2006: State attorney general / Brown's rivals question commitment to death penalty / He says regardless of his past, he'd enforce the law". The San Francisco Chronicle. August 27, 2010.

- ^ Williams, Carol J. (2010-09-22). "Clock is ticking on first execution at San Quentin's revamped death chamber". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-09-26.

- ^ "Brown Wants Executions To Resume In California". CBS News. Associated Press. 2010-09-22. Retrieved 2010-09-27. [dead link]

- ^ Elias, Paul (2010-09-25). "Timing of Calif. Execution Questioned". Time. Associated Press. Retrieved 2010-09-27.

- ^ "State's suit to target mortgage lender for unfair practices". Chicago Tribune. 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ "Illinois AG sues Countrywide over lending practices". Chicago Tribune. Associated Press. 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ "California sues Countrywide". CNN Money.com. 2008-06-25. Retrieved 2008-06-25.

- ^ "BofA to pay $8 billion over subprime suit",'MSNBC', October 6, 2008

- ^ "Calif. Sup. Ct. arguments on Prop. 8, at a glance". Associated Press. 2009-03-01. Retrieved 2010-08-06.

- ^ "California high court upholds same-sex marriage ban". CNN.com. May 26, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Opinion

- ^ Thompson, Don. "Calif. attorney general hopefuls clash in debate". San Jose Mercury News. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ "Court: Calif. need not defend Prop 8". UPI.com. 2010-09-03. Retrieved 2010-10-13.

- ^ Jerry Brown for governor, editorial, Los Angeles Times, October 3, 2010

- ^ Endorsements: Jerry Brown best pick for governor, editorial, The Sacramento Bee, October 3, 2010

- ^ Chronicle Recommends Jerry Brown for Governor, editorial, San Francisco Chronicle, October 3

- ^ Jerry Brown is the right choice for governor, editorial, San Jose Mercury News, October 10, 2010

- ^ Rebuild California: SEIU Voter Guide

- ^ Kernis, Jay (March 2, 2010). "Intriguing people for March 2, 2010". CNN. Turner Broadcasting. Retrieved March 6, 2010.

- ^ "The Anti-Governator: Jerry Brown wants to be governor of California again". The Economist. 12 June 2008.

- ^ http://www.leginfo.ca.gov/.const/.article_20

- ^ "Brown, Newsom, Boxer elected". The Stanford Daily. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ "Jerry Brown wins governor's race". Hearst Communications Inc. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ^ "Jerry Brown and Linda Ronstadt". Ronstadt-linda.com. Retrieved 2010-08-29.

- ^ Steve Rubenstein and Janine DeFeo, "Barzaghi Departs Jerry Brown Staff", San Francisco Chronicle (July 20, 2004)

- ^ Young, Samantha (2010-06-22) "Jerry Brown House, Worth $1.8 Million, Doesn't Fit California Governor Candidate's Tale Of Frugality", The Huffington Post. Retrieved 2010-09-13.

Bibliography

- Bollens, John C. and G. Robert Williams. Jerry Brown: In a Plain Brown Wrapper (Pacific Palisades, California: Palisades Publishers, 1978). ISBN 0-913530-12-3

- Brown, Governor Jerry. Thoughts (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1976)

- Brown, Jerry. Dialogues (Berkeley, California: Berkeley Hills Books, 1998). ISBN 0-9653774-9-0

- Bachelis, Faren Maree (1986), The Pelican Guide to Sacramento and the Gold Country, Pelican, ISBN 0882894978

- Lorenz, J. D. Jerry Brown: The Man on the White Horse (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co, 1978). ISBN 0-395-25767-0

- McDonald, Heather. "Jerry Brown’s No-Nonsense New Age for Oakland", City Journal, Vol. 9, No. 4, Autumn 1999.

- Pack, Robert. Jerry Brown, The Philosopher-Prince (New York: Stein and Day, 1978). ISBN 0-8128-2437-7

- Rapoport, Roger. California Dreaming: The Political Odyssey of Pat & Jerry Brown (Berkeley, CA: Nolo Press, 1982) ISBN 0-917316-48-7

- Schell, Orville. Brown (New York: Random House, 1978). ISBN 0-394-41043-2

External links

- Office of California Attorney General Jerry Brown official California government site

- Jerry Brown 2010 official gubernatorial campaign site

- Governor Edmund G. "Jerry" Brown official biography from the State of California

- Template:GovLinks

- Blog at TypePad (last entry October 8, 2005)

- Blog at Huffington Post (last entry October 21, 2009)

- Newsmaker of the Week: Jerry Brown, SCVTV, May 31, 2006 (video interview 30:00)

- "Jerry Brown envisions still another public role", Christian Science Monitor, November 6, 2006

- "New office, but vintage Jerry Brown, Tim Reiterman, Los Angeles Times, August 19, 2007

- "Sacramento Dreaming Again, George F. Will, The Washington Post, August 7, 2008

- 1938 births

- American bloggers

- American politicians of Irish descent

- American Roman Catholic politicians

- California Attorneys General

- California Democrats

- Governors of California

- Living people

- Mayors of Oakland, California

- Pacifica Radio

- Santa Clara University alumni

- Secretaries of State of California

- State political party chairs of the United States

- United States presidential candidates, 1976

- United States presidential candidates, 1980

- United States presidential candidates, 1992

- University of California, Berkeley alumni

- Yale Law School alumni