List of Christians in science and technology

Appearance

This is a list of Christians in science and technology. People in this list should have their Christianity as relevant to their notable activities or public life, and who have publicly identified themselves as Christians or as of a Christian denomination.

Before the 18th century

- Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179): also known as Saint Hildegard and Sibyl of the Rhine, was a German Benedictine abbess. She is considered to be the founder of scientific natural history in Germany[2]

- Robert Grosseteste (c.1175–1253): Bishop of Lincoln, he was the central character of the English intellectual movement in the first half of the 13th century and is considered the founder of scientific thought in Oxford. He had a great interest in the natural world and wrote texts on the mathematical sciences of optics, astronomy and geometry. He affirmed that experiments should be used in order to verify a theory, testing its consequences and added greatly to the development of the scientific method.[3]

- Albertus Magnus (c.1193–1280): patron saint of scientists in Catholicism who may have been the first to isolate arsenic. He wrote that: "Natural science does not consist in ratifying what others have said, but in seeking the causes of phenomena." Yet he rejected elements of Aristotelianism that conflicted with Catholicism and drew on his faith as well as Neo-Platonic ideas to "balance" "troubling" Aristotelian elements.[note 1][4]

- Jean Buridan (1300–58): French philosopher and priest. One of his most significant contributions to science was the development of the theory of impetus, that explained the movement of projectiles and objects in free-fall. This theory gave way to the dynamics of Galileo Galilei and for Isaac Newton's famous principle of inertia.

- Nicole Oresme (c.1323–1382): Theologian and bishop of Lisieux, he was one of the early founders and popularizers of modern sciences. One of his many scientific contributions is the discovery of the curvature of light through atmospheric refraction.[5]

- Nicholas of Cusa (1401–1464): Catholic cardinal and theologian who made contributions to the field of mathematics by developing the concepts of the infinitesimal and of relative motion. His philosophical speculations also anticipated Copernicus’ heliocentric world-view.[6]

- Otto Brunfels (1488–1534): A theologian and botanist from Mainz, Germany. His Catalogi virorum illustrium is considered to be the first book on the history of evangelical sects that had broken away from the Catholic Church. In botany his Herbarum vivae icones helped earn him acclaim as one of the "fathers of botany".[7]

- William Turner (c.1508–1568): sometimes called the "father of English botany" and was also an ornithologist. He was arrested for preaching in favor of the Reformation. He later became a Dean of Wells Cathedral, but was expelled for nonconformity.[8]

- Ignazio Danti (1536–1586): As bishop of Alatri he convoked a diocesan synod to deal with abuses. He was also a mathematician who wrote on Euclid, an astronomer, and a designer of mechanical devices.[9]

- Francis Bacon (1561–1626): Considered among the fathers of empiricism and is credited with establishing the inductive method of experimental science via what is called the scientific method today.[10][11]

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642): Italian astronomer, physicist, engineer, philosopher, and mathematician who played a major role in the scientific revolution during the Renaissance.[12][13]

- Laurentius Gothus (1565–1646): A professor of astronomy and Archbishop of Uppsala. He wrote on astronomy and theology.[14]

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630): Prominent astronomer of the Scientific Revolution, discovered Kepler's laws of planetary motion.

- Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655): Catholic priest who tried to reconcile Atomism with Christianity. He also published the first work on the Transit of Mercury and corrected the geographical coordinates of the Mediterranean Sea.[15]

- Anton Maria of Rheita (1597–1660): Capuchin astronomer. He dedicated one of his astronomy books to Jesus Christ, a "theo-astronomy" work was dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary, and he wondered if beings on other planets were "cursed by original sin like humans are."[16]

- Juan Lobkowitz (1606–1682): Cistercian monk who did work on Combinatorics and published astronomy tables at age 10. He also did works of theology and sermons.[17]

- Seth Ward (1617–1689): Anglican Bishop of Salisbury and Savilian Chair of Astronomy from 1649 to 1661. He wrote Ismaelis Bullialdi astro-nomiae philolaicae fundamenta inquisitio brevis and Astronomia geometrica. He also had a theological/philosophical dispute with Thomas Hobbes and as a bishop was severe toward nonconformists.[18]

- Blaise Pascal (1623–1662): Jansenist thinker;[note 2] well known for Pascal's law (physics), Pascal's theorem (math), Pascal's calculator (computing) and Pascal's Wager (theology).[19]

- John Wilkins, FRS (14 February 1614–19 November 1672) was an Anglican clergyman, natural philosopher and author, and was one of the founders of the Royal Society. He was Bishop of Chester from 1668 until his death.

- Francesco Redi (1626–1697): Italian physician and Roman Catholic who is remembered as the "father of modern parasitology".

- Robert Boyle (1627–1691): Prominent scientist and theologian who argued that the study of science could improve glorification of God.[20][21] A strong Christian apologist, he is considered one of the most important figures in the history of Chemistry.

- Isaac Barrow (1630–1677): English theologian, scientist, and mathematician. He wrote Expositions of the Creed, The Lord's Prayer, Decalogue, and Sacraments and Lectiones Opticae et Geometricae.[22]

- Nicolas Steno (1638–1686): Lutheran convert to Catholicism, his beatification in that faith occurred in 1987. As a scientist he is considered a pioneer in both anatomy and geology, but largely abandoned science after his religious conversion.[23]

- Isaac Newton (1643–1727): Prominent scientist during the Scientific Revolution. Physicist, discoverer of gravity.[24]

18th century (1701–1800)

- John Ray (1627–1705): English botanist who wrote The Wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation (1691) and was among the first to attempt a biological definition for the concept of species. The John Ray Initiative[25] of Environment and Christianity is also named for him.[26]

- Gottfried Leibniz (1646–1716): He was a philosopher who developed the philosophical theory of the Pre-established harmony; he is also most noted for his optimism, e.g., his conclusion that our Universe is, in a restricted sense, the best possible one that God could have created. He also made major contributions to mathematics, physics, and technology. He created the Stepped Reckoner and his Protogaea concerns geology and natural history. He was a Lutheran who worked with convert to Catholicism John Frederick, Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg in hopes of a reunification between Catholicism and Lutheranism.[27]

- Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723): Dutch Reformed Calvinist who is remembered as the "father of microbiology".

- Stephen Hales (1677–1761): Copley Medal winning scientist significant to the study of plant physiology. As an inventor designed a type of ventilation system, a means to distill sea-water, ways to preserve meat, etc. In religion he was an Anglican curate who worked with the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and for a group working to convert black slaves in the West Indies.[28]

- Firmin Abauzit (1679–1767): physicist and theologian. He translated the New Testament into French and corrected an error in Newton's Principia.[29]

- Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772): He did a great deal of scientific research with the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences having commissioned work by him.[30] His religious writing is the basis of Swedenborgianism and several of his theological works contained some science hypotheses, most notably the Nebular hypothesis for the origin of the Solar System.[31]

- Albrecht von Haller (1708–1777): Swiss anatomist, physiologist known as "the father of modern physiology." A Protestant, he was involved in the erection of the Reformed church in Göttingen, and, as a man interested in religious questions, he wrote apologetic letters which were compiled by his daughter under the name .[32]

- Leonhard Euler (1707–1783): significant mathematician and physicist, see List of topics named after Leonhard Euler. The son of a pastor, he wrote Defense of the Divine Revelation against the Objections of the Freethinkers and is also commemorated by the Lutheran Church on their Calendar of Saints on May 24.[33]

- Mikhail Lomonosov (1711–1765): Russian Orthodox Christian who discovered the atmosphere of Venus and formulated the law of conservation of mass in chemical reactions.

- Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794): considered the "father of modern chemistry". He is known for his discovery of oxygen's role in combustion, developing chemical nomenclature, developing a preliminary periodic table of elements, and the law of conservation of mass. He was a Catholic and defender of scripture.[34]

- Herman Boerhaave (1668–1789): remarkable Dutch physician and botanist known as the founder of clinical teaching. A collection of his religious thoughts on medicine, translated from Latin into English, has been compiled under the name Boerhaaveìs Orations.[35]

- John Michell (1724–1793): English clergyman who provided pioneering insights in a wide range of scientific fields, including astronomy, geology, optics, and gravitation.[36][37]

- Maria Gaetana Agnesi (1718–1799): mathematician appointed to a position by Pope Benedict XIV. After her father died she devoted her life to religious studies, charity, and ultimately became a nun.[38]

- Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778): Swedish botanist, physician, and zoologist, "father of modern taxonomy".

19th century (1801–1900)

- Joseph Priestley (1733–1804): Nontrinitarian clergyman who wrote the controversial work History of the Corruptions of Christianity. He is credited with discovering oxygen.[note 3]

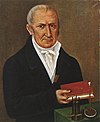

- Alessandro Volta (1745–1827): Italian physicist who invented the first electric battery. The unit Volt was named after him.[39]

- Samuel Vince (1749–1821): Cambridge astronomer and clergyman. He wrote Observations on the Theory of the Motion and Resistance of Fluids and The credibility of Christianity vindicated, in answer to Mr. Hume's objections. He won the Copley Medal in 1780, before the period dealt with here ended.[40]

- Isaac Milner (1750–1820): Lucasian Professor of Mathematics known for work on an important process to fabricate Nitrous acid. He was also an evangelical Anglican who co-wrote Ecclesiastical History of the Church of Christ with his brother and played a role in the religious awakening of William Wilberforce. He also led to William Frend being expelled from Cambridge for a purported attack by Frend on religion.[41]

- William Kirby (1759–1850): Parson-naturalist who wrote On the Power Wisdom and Goodness of God. As Manifested in the Creation of Animals and in Their History, Habits and Instincts and was a founding figure in British entomology.[42][43] was an English chemist, physicist, and meteorologist. He is best known for introducing the atomic theory into chemistry. He was a Quaker Christian.[44]

- John Dalton (1766–1844): an English chemist, physicist, and meteorologist. He is best known for introducing the atomic theory into chemistry, and for his research into colour blindness, sometimes referred to as Daltonism in his honour.

- Georges Cuvier (1769–1832): French naturalist and zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "father of paleontology".

- Thomas Robert Malthus (1766–1834): English cleric and scholar whose views on population caps were an influence on pioneers of evolutionary biology, including Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace.

- Andre Marie Ampere (1775–1836): one of the founders of classical electromagnetism. The unit for electric current, Ampere, is named after him.[45]

- Olinthus Gregory (1774–1841): wrote Lessons Astronomical and Philosophical in 1793 and became mathematical master at the Royal Military Academy in 1802. An abridgment of his 1815 Letters on the Evidences of Christianity was done by the Religious Tract Society.[46]

- John Abercrombie (1780–1844): Scottish physician and Christian philosopher[47] who created the a textbook about neuropathology.

- Augustin-Louis Cauchy (1789–1857): French mathematician, engineer, and physicist who made pioneering contributions to several branches of mathematics, including mathematical analysis and continuum mechanics. He was a committed Catholic and member of the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul.[48] Cauchy lent his prestige and knowledge to the École Normale Écclésiastique, a school in Paris run by Jesuits, for training teachers for their colleges. He also took part in the founding of the Institut Catholique de Paris. Cauchy had links to the Society of Jesus and defended them at the academy when it was politically unwise to do so.

- William Buckland (1784–1856): Anglican priest/geologist who wrote Vindiciae Geologiae; or the Connexion of Geology with Religion explained. He was born in 1784, but his scientific life did not begin before the period discussed herein.[49]

- Mary Anning (1799–1847): paleontologist who became known for discoveries of certain fossils in Lyme Regis, Dorset. Anning was devoutly religious, and attended a Congregational, then Anglican church.[50]

- Marshall Hall (1790–1857): notable English physiologist who contributed with anatomical understanding and proposed a number of techniques in medical science. A Christian, his religious thoughts were collected in the biographical book Memoirs of Marshall Hall, by his widow[51] (1861). He was also an abolitionist who opposed slavery on religious grounds. He believed the institution of slavery was a sin against God and denial of the Christian faith.[52]

- John Stevens Henslow (1796–1861): British priest, botanist and geologist who was Charles Darwin's tutor and enabled him to get a place on HMS Beagle.

- Lars Levi Læstadius (1800–1861): botanist who started a revival movement within Lutheranism called Laestadianism. This movement is among the strictest forms of Lutheranism. As a botanist he has the author citation Laest and discovered four species.[53]

- Edward Hitchcock (1793–1864): geologist, paleontologist, and Congregationalist pastor. He worked on Natural theology and wrote on fossilized tracks.[54]

- Benjamin Silliman (1779–1864): chemist and science educator at Yale; the first person to distill petroleum, and a founder of the American Journal of Science, the oldest scientific journal in the United States. An outspoken Christian,[55] he was an old-earth creationist who openly rejected materialism.

- Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866): son of a pastor,[note 4] he entered the University of Göttingen at the age of 19, originally to study philology and theology in order to become a pastor and help with his family's finances. Upon the suggestion of Gauss, he switched to mathematics.[56] He made lasting contributions to mathematical analysis, number theory, and differential geometry, some of them enabling the later development of general relativity.

- William Whewell (1794–1866): professor of mineralogy and moral philosophy. He wrote An Elementary Treatise on Mechanics in 1819 and Astronomy and General Physics considered with reference to Natural Theology in 1833.[57][58] He is the wordsmith who coined the terms "scientist", "physicist", "anode", "cathode" and many other commonly used scientific words.

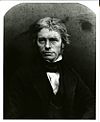

- Michael Faraday (1791–1867): Glasite church elder for a time, he discussed the relationship of science to religion in a lecture opposing Spiritualism.[59][60] He is known for his contributions in establishing electromagnetic theory and his work in chemistry such as establishing electrolysis.

- James David Forbes (1809–1868): physicist and glaciologist who worked extensively on the conduction of heat and seismology. He was a Christian as can be seen in the work "Life and Letters of James David Forbes" (1873).

- Charles Babbage (1791–1871): mathematician and analytical philosopher known as the first computer scientist who originated the idea of a programmable computer. He wrote the Ninth Bridgewater Treatise,[61][62] and the Passages from the Life of a Philosopher (1864) where he raised arguments to rationally defend the belief in miracles.[63]

- Adam Sedgwick (1785–1873): Anglican priest and geologist whose A Discourse on the Studies of the University discusses the relationship of God and man. In science he won both the Copley Medal and the Wollaston Medal.[64] His students included Charles Darwin.

- John Bachman (1790–1874): wrote numerous scientific articles and named several species of animals. He also was a founder of the Lutheran Theological Southern Seminary and wrote works on Lutheranism.[65]

- Temple Chevallier (1794–1873): priest and astronomer who did Of the proofs of the divine power and wisdom derived from the study of astronomy. He also founded the Durham University Observatory, hence the Durham Shield is pictured.[66]

- Robert Main (1808–1878): Anglican priest who won the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1858. Robert Main also preached at the British Association of Bristol.[67]

- James Clerk Maxwell (1831–1879): Although Clerk as a boy was taken to Presbyterian services by his father and to Anglican services by his aunt, while still a young student at Cambridge he underwent an Evangelical conversion that he described as having given him a new perception of the Love of God.[note 5] Maxwell's evangelicalism "committed him to an anti-positivist position."[68][69] He is known for his contributions in establishing electromagnetic theory (Maxwell's Equations) and work on the chemical kinetic theory of gases.

- James Bovell (1817–1880): Canadian physician and microscopist who was member of Royal College of Physicians. He was the mentor of William Osler, as well as an Anglican minister and religious author who wrote about natural theology.[70]

- Andrew Pritchard (1804–1882): English naturalist and natural history dealer who made significant improvements to microscopy and wrote the standard work on aquatic micro-organisms. He devoted much energy to the chapel he attended, Newington Green Unitarian Church.

- Gregor Mendel (1822–1884): Augustinian Abbot who was the "father of modern genetics" for his study of the inheritance of traits in pea plants.[71] He preached sermons at Church, one of which deals with how Easter represents Christ's victory over death.[72]

- Lewis Carroll (1832–1898): [real name: Charles Lutwidge Dodgson], English writer, mathematician, and Anglican deacon. Robbins' and Rumsey's investigation of Dodgson's method, a method of evaluating determinants, led them to the Alternating Sign Matrix conjecture, now a theorem.

- Heinrich Hertz (1857–1894): German physicist who first conclusively proved the existence of the electromagnetic waves.

- Philip Henry Gosse (1810–1888): marine biologist who wrote Aquarium (1854), and A Manual of Marine Zoology (1855–56). He is more notable as a Christian Fundamentalist who coined the idea of Omphalos (theology).[73]

- Asa Gray (1810–1888): His Gray's Manual remains a pivotal work in botany. His Darwiniana has sections titled "Natural selection not inconsistent with Natural theology", "Evolution and theology", and "Evolutionary teleology." The preface indicates his adherence to the Nicene Creed in concerning these religious issues.[74]

- Julian Tenison Woods (1832–1889): co-founder of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart who won a Clarke Medal shortly before death. A picture from Waverley Cemetery, where he's buried, is shown.[75]

- Louis Pasteur (1822–1895): French biologist, microbiologist and chemist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization.

- James Dwight Dana (1813–1895): geologist, mineralogist, and zoologist. He received the Copley Medal, Wollaston Medal, and the Clarke Medal. He also wrote a book titled Science and the Bible and his faith has been described as "both orthodox and intense."[76]

- James Prescott Joule (1818–1889): studied the nature of heat, and discovered its relationship to mechanical work. This led to the law of conservation of energy, which led to the development of the first law of thermodynamics. The SI derived unit of energy, the joule, is named after James Joule.[77]

- John William Dawson (1820–1899): Canadian geologist who was the first president of the Royal Society of Canada and served as president of both the British and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. A presbyterian, he spoke against Darwin's theory and came to write The Origin of the World, According to Revelation and Science (1877) where he put together his theological and scientific views.[78]

- Armand David (1826–1900): Catholic missionary to China and member of the Lazarists who considered his religious duties to be his principal concern. He was also a botanist with the author abbreviation David and as a zoologist he described several species new to the West.[79]

- Joseph Lister (1827–1912): British surgeon and a pioneer of antiseptic surgery. He raised as a Quaker, he subsequently left the Quakers, joined the Scottish Episcopal Church.[80]

20th century (1901–2000)

According to 100 Years of Nobel Prizes a review of Nobel prizes award between 1901 and 2000 reveals that (65.4%) of Nobel Prizes Laureates, have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference.[81] Overall, 72.5% of all the Nobel Prizes in Chemistry,[82] 65.3% in Physics,[82] 62% in Medicine,[82] 54% in Economics were either Christians or had a Christian background.[82]

- John Hall Gladstone (1827–1902): served as president of the Physical Society between 1874 and 1876 and during 1877–1879 was president of the Chemical Society. He also belonged to the Christian Evidence Society.[83][84]

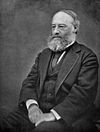

- George Stokes (1819–1903): minister's son, he wrote a book on Natural Theology. He was also one of the Presidents of the Royal Society and made contributions to Fluid dynamics.[85][86]

- Henry Baker Tristram (1822–1906): founding member of the British Ornithologists' Union. His publications included The Natural History of the Bible (1867) and The Fauna and Flora of Palestine (1884).[87]

- Enoch Fitch Burr (1818–1907): astronomer and Congregational Church pastor who lectured extensively on the relationship between science and religion. He also wrote Ecce Coelum: or Parish Astronomy in 1867. He once stated that "an undevout astronomer is mad" and held a strong belief in extraterrestrial life.[88][89]

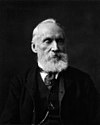

- Lord Kelvin (1824–1907): At the University of Glasgow he did important work in the mathematical analysis of electricity and formulation of the first and second laws of thermodynamics. He gave a famous address to the Christian Evidence Society. In science he won the Copley Medal and the Royal Medal.[90]

- William Dallinger (1839–1909): British minister in the Wesleyan Methodist Church and an accomplished scientist who studied the complete lifecycle of unicellular organisms under the microscope.[91]

- Emil Theodor Kocher (1841–1917): Swiss physician and medical researcher who received the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his work in the physiology, pathology and surgery of the thyroid. Kocher was a deeply religious man and also part of the Moravian Church, Kocher attributed all his successes and failures to God.[92]

- Georg Cantor (1845–1918): German mathematician who created the theory of transfinite numbers and set theory, which has become a fundamental theory in mathematics. He was a devout Lutheran whose explicit Christian beliefs shaped his philosophy of science.[93] Joseph Dauben has traced the impact Cantor's Christian convictions had on the development of transfinite set theory.[94][95]

- J. J. Thomson (1856–1940): English physicist and Nobel Laureate in Physics, credited with the discovery and identification of the electron; and with the discovery of the first subatomic particle. He was an Anglican.[96][97][98]

- Wilhelm Röntgen (1845–1923): German engineer and physicist, who, on 8 November 1895, produced and detected electromagnetic radiation in a wavelength range known as X-rays or Röntgen rays, an achievement that earned him the first Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901[99]

- Giuseppe Mercalli (1850–1914): Italian volcanologist and Catholic priest. He is best remembered for the Mercalli intensity scale for measuring earthquakes.

- Pierre Duhem (1861–1916): worked on Thermodynamic potentials and wrote histories advocating that the Roman Catholic Church helped advance science.[100][101][102][103][104]

- James Britten (1846–1924): botanist who was heavily involved in the Catholic Truth Society.[105][106]

- Charles Doolittle Walcott (1850–1927): paleontologist, most notable for his discovery of the Burgess Shale of British Columbia. Stephen Jay Gould said that Walcott, "discoverer of the Burgess Shale fossils, was a convinced Darwinian and an equally firm Christian, who believed that God had ordained natural selection to construct a history of life according to His plans and purposes."[107]

- Johannes Reinke (1849–1931): German phycologist and naturalist who founded the German Botanical Society. An opposer of Darwinism and the secularization of science, he wrote Kritik der Abstammungslehre (Critique of the theory of evolution), (1920), and Naturwissenschaft, Weltanschauung, Religion, (Science, philosophy, religion), (1923). He was a Lutheran.[108]

- Guglielmo Marconi (1874–1937): Italian inventor and electrical engineer known for his pioneering work on long-distance radio transmission and for his development of Marconi's law and a radio telegraph system. He shared the 1909 Nobel Prize in Physics.[109][110]

- Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955): French Jesuit paleontologist, co-discoverer of the Peking Man, noted for his work on evolutionary theory and Christianity. He postulated the Omega Point as the end-goal of Evolution and he is widely regarded as one of the most important Catholic theologians of the 20th century.

- William Williams Keen (1837–1932): first brain surgeon in the United States, and a prominent surgical pathologist who served as president of the American Medical Association. He also wrote I believe in God and in evolution.[111]

- Francis Patrick Garvan (1875–1937): Priestley Medalist who received a "Mendel Medal" from Villanova University, was mentioned by Catholic Action as a "prominent Catholic layman", and was involved with the Catholic University of America.[112][113]

- Pavel Florensky (1882–1937): Russian Orthodox priest who wrote a book on Dielectrics and wrote of imaginary numbers having a relationship to the Kingdom of God.[114]

- Eberhard Dennert (1861–1942): German naturalist and botanist who founded in 1907 the Kepler Association, a group of German intellectuals who strongly opposed Ernst Haeckel's Monist League and Darwin's theory.[115] A Lutheran, he wrote Vom Sterbelager des Darwinismus, which had an authorized English translation under the name At The Deathbed of Darwinism (1904).[116]

- George Washington Carver (1864–1943): American scientist, botanist, educator, and inventor. Carver believed he could have faith both in God and science and integrated them into his life. He testified on many occasions that his faith in Jesus was the only mechanism by which he could effectively pursue and perform the art of science.[117]

- Arthur Eddington (1882–1944): British astrophysicist of the early 20th century. He was also a philosopher of science and a popularizer of science. The Eddington limit, the natural limit to the luminosity of stars, or the radiation generated by accretion onto a compact object, is named in his honor. He is famous for his work regarding the theory of relativity. Eddington was a lifelong Quaker, and gave the Gifford Lectures in 1927.[118]

- Alexis Carrel (1873–1944): French surgeon and biologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1912 for pioneering vascular suturing techniques.[119]

- Charles Glover Barkla (1877–1944): British physicist, and the winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1917 for his work in X-ray spectroscopy and related areas in the study of X-rays (Roentgen rays).[120] Mr. Barkla was a Methodist and considered his work to be part of the quest for God, the Creator".[121][122][123]

- John Ambrose Fleming (1849–1945): noted for the Right-hand rule and work on vacuum tubes. He also won the Hughes Medal. In religious activities he was president of the Victoria Institute, and preached at St Martin-in-the-Fields.[124][125][126]

- Philipp Lenard (1862–1947): German physicist and the winner of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1905 for his research on cathode rays and the discovery of many of their properties. He was also an active proponent of the Nazi ideology.[127][128]

- Robert Millikan (1868–1953): second son of Reverend Silas Franklin Millikan, he wrote about the reconciliation of science and religion in books like Evolution in Science and Religion. He won the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physics.[129][130][131][132][133]

- Karl Landsteiner (1868–1943): Austrian biologist, physician, and immunologist.[134] In 1930, he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Landsteiner converted from Judaism to Roman Catholicism in 1890.[135]

- Charles Stine (1882–1954): son of a minister who was VP of DuPont. In religion he wrote A Chemist and His Bible and as a chemist he won the Perkin Medal.[136]

- E. T. Whittaker (1873–1956): converted to Catholicism in 1930 and member of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences. His 1946 Donnellan Lecture was entitled on Space and Spirit. Theories of the Universe and the Arguments for the Existence of God. He also received the Copley Medal and had written on Mathematical physics before conversion.[137]

- Arthur Compton (1892–1962): won a Nobel Prize in Physics. He also was a deacon in the Baptist Church and wrote an article in Christianity Takes a Stand that supported the controversial idea of the United States maintaining the peace through a nuclear-armed air force.[138][139]

- Victor Francis Hess (1883–1964): practicing Roman Catholic who won a Nobel Prize in Physics and discovered cosmic rays.[140] In 1946 he wrote on the topic of the relationship between science and religion in his article "My Faith", in which he explained why he believed in God.[141]

- Ronald Fisher (1890–1962): English statistician, evolutionary biologist and geneticist. He preached sermons and published articles in church magazines.[142]

- Georges Lemaître (1894–1966): Roman Catholic priest who was first to propose the Big Bang theory.[143]

- Kathleen Lonsdale (1903–1971): notable Irish crystallographer, the first woman tenured professor at University College London, first woman president of the International Union of Crystallography, and first woman president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. She converted to Quakerism and was an active Christian pacifist. She was the first secretary of the Churches' Council of Healing and delivered a Swarthmore Lecture.

- Igor Sikorsky (1889–1972): Russian–American aviation pioneer in both helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft. Sikorsky was a deeply religious Russian Orthodox Christian[144] and authored two religious and philosophical books (The Message of the Lord's Prayer and The Invisible Encounter).

- Neil Kensington Adam (1891–1973): British chemist who wrote the article A CHRISTIAN SCIENTIST'S APPROACH TO THE STUDY OF NATURAL SCIENCE.[145][146]

- David Lack (1910–1973): director of the Edward Grey Institute of Field Ornithology and in part known for his study of the genus Euplectes. He converted to Anglicanism at 38 and wrote Evolutionary Theory and Christian Belief in 1957.[147][148]

- Hugh Stott Taylor (1910–1974): chemist who received Villanova University's "Mendel Medal"[149] and was made a Knight Commander of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great.[150]

- Charles Coulson (1910–1974): Methodist who wrote Science and Christian Belief in 1955. In 1970 he won the Davy Medal.[151]

- George R. Price (1922–1975): American population geneticist who while a strong atheist converted to Christianity. He went on to write commentaries on the New Testament and dedicated portions of his life to helping the poor.[152]

- Theodosius Dobzhansky (1900–1975): Russian Orthodox geneticist who criticized young Earth creationism in an essay, "Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution," and argued that science and faith did not conflict.[153][154]

- Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976): German theoretical physicist and one of the key pioneers of quantum mechanics. Heisenberg was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for 1932 "for the creation of quantum mechanics".[155]

- Michael Polanyi (1891–1976): born Jewish, but became a Christian. In 1926 he was appointed to a Chemistry chair in Berlin, but in 1933 when Hitler came to power he accepted a Chemistry chair (and then in 1948 a Social Sciences chair) at the University of Manchester. In 1946 he wrote Science, Faith, and Society ISBN 0-226-67290-5.[156]

- Wernher von Braun (1912–1977): "one of the most important rocket developers and champions of space exploration during the period between the 1930s and the 1970s."[157] He was a Lutheran who as a youth and young man had little interest in religion. But as an adult he developed a firm belief in the Lord and in the afterlife. He was pleased to have opportunities to speak to peers (and anybody else who would listen) about his faith and Biblical beliefs.[158]

- Pascual Jordan (1902–1980): German theoretical and mathematical physicist who made significant contributions to quantum mechanics and quantum field theory. He contributed much to the mathematical form of matrix mechanics, and developed canonical anticommutation relations for fermions.[159][160]

- Peter Stoner (1888–1980): co-founder of the American Scientific Affiliation who wrote Science Speaks.[161][162]

- Gerty Cori (1896–1957): Czech-American biochemist who became the third woman—and first American woman—to win a Nobel Prize in science, and the first woman to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Gerty converted to Catholicism.[163][164]

- Henry Eyring (1901–1981): American chemist known for developing the Eyring equation. Also a Latter-Day Saint whose interactions with LDS President Joseph Fielding Smith on science and faith are a part of LDS history.[165][166]

- Kurt Gödel (1906–1978): German-Austrian logician, mathematician, and analytic philosopher. He described his religion as "baptized Lutheran (but not member of any religious congregation). My belief is theistic, not pantheistic, following Leibniz rather than Spinoza."[167] He described himself as religious and read the Bible in bed every Sunday morning.[168] Gödel characterized his own philosophy in the following way: "My philosophy is rationalistic, idealistic, optimistic, and theological."[169] Gödel's interest in theology is noticeable in the Max Phil Notebooks.[170]

- Mary Kenneth Keller (1914–1985): American nun who was the first woman to earn a PhD in computer science in the US.[171]

- William G. Pollard (1911–1989): Anglican priest who wrote Physicist and Christian. In addition he worked on the Manhattan Project and for years served as the executive director of Oak Ridge Institute of Nuclear Studies.[172]

- Frederick Rossini (1899–1990): American noted for his work in chemical thermodynamics. In science he received the Priestley Medal and the National Medal of Science. An example of the second medal is pictured. As a Catholic he received the Laetare Medal of the University of Notre Dame. He was dean of the College of Science at Notre Dame from 1960 to 1971, a position he may have taken partly due to his faith.[173][174]

- Aldert van der Ziel (1910–1991): researched Flicker noise and has the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers named an award for him. He also was a conservative Lutheran who wrote The Natural Sciences and the Christian Message.[175]

- Jérôme Lejeune (1926–1994): French pediatrician and geneticist known for research into chromosome abnormalities, particularly Down syndrome. He was the first president of the Pontifical Academy for Life and has been named a "Servant of God."[176][177]

- Alonzo Church (1903–1995): American mathematician and logician who made major contributions to mathematical logic and the foundations of theoretical computer science. He was a lifelong member of the Presbyterian church.[178]

- Ernest Walton (1903–1995): Irish physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1951 for his work with John Cockcroft with "atom-smashing" experiments done at Cambridge University in the early 1930s, and so became the first person in history to artificially split the atom, thus ushering the nuclear age. He spoke on science and faith topics.[179]

- Nevill Francis Mott (1905–1996): Anglican, was a Nobel Prize-winning physicist known for explaining the effect of light on a photographic emulsion.[180] He was baptized at 80 and edited Can Scientists Believe?.[181]

- Mary Celine Fasenmyer (1906–1996): member of the Sisters of Mercy known for Sister Celine's polynomials. Her work was also important to WZ Theory.[182]

- Arthur Leonard Schawlow (1921–1999): American physicist who is best remembered for his work on lasers, for which he shared the 1981 Nobel Prize in Physics. Shawlow was a "fairy Orthodox Protestant."[183] In an interview, he commented regarding God: "I find a need for God in the universe and in my own life."[184]

- Carlos Chagas Filho (1910–2000): neuroscientist who headed the Pontifical Academy of Sciences for 16 years. He studied the Shroud of Turin and his "the Origin of the Universe", "the Origin of Life", and "the Origin of Man" involved an understanding between Catholicism and Science. He was from Rio de Janeiro.[185]

21st century (2001–2100)

- Sir Robert Boyd (1922–2004): pioneer in British space science who was vice president of the Royal Astronomical Society. He lectured on faith being a founder of the "Research Scientists' Christian Fellowship" and an important member of its predecessor Christians in Science.[186]

- Richard H. Bube (1927–2018): emeritus professor of the material sciences at Stanford University. He was a prominent member of the American Scientific Affiliation.[187]

- Rod Davies (1930–2015): professor of radio astronomy at the University of Manchester. He was the president of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1987–1989, and director of the Jodrell Bank Observatory in 1988–97. He is best known for his research on the cosmic microwave background and the 21 cm line.[188]

- Richard Smalley (1943–2005): Nobel laureate in Chemistry known for buckyballs. In his last years he renewed an interest in Christianity and supported Old Earth Creationism

- Mariano Artigas (1938–2006): had doctorates in both physics and philosophy. He belonged to the European Association for the Study of Science and Theology and also received a grant from the Templeton Foundation for his work in the area of science and religion.[189]

- J. Laurence Kulp (1921–2006): Plymouth Brethren member who led major studies on the effects of nuclear fallout and acid rain. He was a prominent advocate in American Scientific Affiliation circles in favor of an Old Earth and against flood geology.[190][191][192][193]

- Arthur Peacocke (1924–2006): Anglican priest and biochemist, his ideas may have influenced Anglican and Lutheran views of evolution. Winner of the 2001 Templeton Prize[194]

- John Billings (1918–2007): Australian physician who developed the Billings ovulation method of Natural family planning. In 1969, Billings was made a Knight Commander of the Order of St. Gregory the Great (KCSG) by Pope Paul VI.[195]

- Russell L. Mixter (1906–2007): noted for leading the American Scientific Affiliation (ASA) away from anti-evolutionism, and for his advocacy of progressive creationism.[193][196]

- C. F. von Weizsäcker (1912–2007): German nuclear physicist who is the co-discoverer of the Bethe-Weizsäcker formula. His The Relevance of Science: Creation and Cosmogony concerned Christian and moral impacts of science. He headed the Max Planck Society from 1970 to 1980. After that he retired to be a Christian pacifist.[197]

- Stanley Jaki (1924–2009): Benedictine priest and Distinguished Professor of Physics at Seton Hall University, New Jersey, who won a Templeton Prize and advocated the idea modern science could only have arisen in a Christian society.[198]

- Allan Sandage (1926–2010): astronomer who did not really study Christianity until after age forty. He wrote the article A Scientist Reflects on Religious Belief and made discoveries concerning the Cigar Galaxy.[199][200][201][202]

- Ernan McMullin (1924–2011): ordained in 1949 as a catholic priest, McMullin was a philosopher of science who taught at the University of Notre Dame. McMullin wrote on the relationship between cosmology and theology, the role of values in understanding science, and the impact of science on Western religious thought, in books such as Newton on Matter and Activity (1978) and The Inference that Makes Science (1992). He was also an expert on the life of Galileo.[203] McMullin also opposed intelligent design and defended theistic evolution.[204]

- Joseph Murray (1919–2012): Catholic surgeon who pioneered transplant surgery. He won the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1990.[205]

- Ian Barbour (1923–2013): physicist who wrote Christianity and the Scientists in 1960, and When Science Meets Religion ISBN 0-06-060381-X in 2000.[206]

- Charles H. Townes (1915–2015): in 1964 he won the Nobel Prize in Physics and in 1966 he wrote The Convergence of Science and Religion.[207][208]

- Peter E. Hodgson (1928–2008): British physicist, was one of the first to identify the K meson and its decay into three pions, and a consultant to the Pontifical Council for Culture.

- Nicola Cabibbo (1935–2010): Italian physicist, discoverer of the universality of weak interactions (Cabibbo angle), president of the Pontifical Academy of Sciences from 1993 until his death.

- Walter Thirring (1927–2014): Austrian physicist after whom the Thirring model in quantum field theory is named. He is the son of the physicist Hans Thirring, co-discoverer of the Lense-Thirring frame dragging effect in general relativity. He also wrote Cosmic Impressions: Traces of God in the Laws of Nature.[209]

- Edward Nelson (1932–2014): American mathematician known for his work on mathematical physics and mathematical logic. In mathematical logic, he was noted especially for his internal set theory, and views on ultrafinitism and the consistency of arithmetic. He also wrote on the relationship between religion and mathematics.[210][211][212]

- Peter Grünberg (1939–2018): German physicist; Nobel Prize in Physics laureate for his discovery with Albert Fert of giant magnetoresistance which brought about a breakthrough in gigabyte hard disk drives[213]

- Martin Bott (1926–2018): British geologist and now emeritus professor in the Department of Earth Sciences at the University of Durham, England. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1976 and was the 1992 recipient of the Wollaston Medal from the Geological Society of America.[214]

- R. J. Berry (1934–2018): former president of both the Linnean Society of London and the "Christians in Science" group. He wrote God and the Biologist: Personal Exploration of Science and Faith (Apollos 1996) ISBN 0-85111-446-6 He taught at University College London for over 20 years.[215][216]

- Derek Burke (1930–2019): British academic and molecular biologist. Formerly a vice-chancellor of the University of East Anglia. Specialist advisor to the House of Commons Select Committee on Science and Technology since 1985.[217][218]

- George Coyne (1933–2020): Jesuit astronomer and former director of the Vatican Observatory.[219]

- Katherine Johnson (1918–2020): space scientist, physicist, and mathematician whose calculations of orbital mechanics as a NASA employee were critical to the success of the first and subsequent U.S. manned spaceflights. She was portrayed as a lead character in the film Hidden Figures.[220]

- Freeman Dyson (1923–2020): English-born American theoretical physicist and mathematician, known for his work in quantum electrodynamics, solid-state physics, astronomy and nuclear engineering.

- John T. Houghton (1931–2020): British atmospheric physicist who was the co-chair of the Nobel Peace Prize winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) scientific assessment working group. He was professor in atmospheric physics at the University of Oxford and former director general at the Met Office.

- John D. Barrow (1952–2020): English cosmologist based at the University of Cambridge who did notable writing on the implications of the Anthropic principle. He is a United Reformed Church member and won the Templeton Prize in 2006. He once held the position of Gresham Professor of Astronomy as well as Gresham Professor of Geometry.[221][222]

- Henri Fontaine (1924–2020): French Roman Catholic missionary, pre-Tertiary geologist/paleontologist, Paleozoic corals specialist, and archaeologist.

- John Polkinghorne (1930–2021): British particle physicist and Anglican priest who wrote Science and the Trinity (2004) ISBN 0-300-10445-6. He was professor of mathematical physics at the University of Cambridge prior to becoming a priest. Winner of the 2002 Templeton Prize.[223]

Currently living

Biological and biomedical sciences

- Denis Alexander (born 1945): Emeritus Director of the Faraday Institute at the University of Cambridge and author of Rebuilding the Matrix – Science and Faith in the 21st Century. He also supervised a research group in cancer and immunology at the Babraham Institute.[224]

- Werner Arber (born 1929): Swiss microbiologist and geneticist. Along with American researchers Hamilton Smith and Daniel Nathans, he shared the 1978 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of restriction endonucleases. In 2011, Pope Benedict XVI appointed Arber as president of the Pontifical Academy—the first Protestant to hold that position.[225]

- Robert T. Bakker (born 1945): paleontologist who was a leading figure in the "Dinosaur Renaissance" and known for the theory some dinosaurs were warm-blooded. He is also a Pentecostal preacher who advocates theistic evolution and has written on religion.[226][227]

- Dan Blazer (born 1944): American psychiatrist and medical researcher who is Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Duke University School of Medicine. He is known for researching the epidemiology of depression, substance use disorders, and the occurrence of suicide among the elderly. He has also researched the differences in the rate of substance use disorders among races.[228]

- William Cecil Campbell (born 1930): Irish-American biologist and parasitologist known for his work in discovering a novel therapy against infections caused by roundworms, for which he was jointly awarded the 2015 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine[229]

- Francis Collins (born 1950): director of the National Institutes of Health and former director of the US National Human Genome Research Institute. He has also written on religious matters in articles and the book The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief.[230][231]

- Peter Dodson (born 1946): American paleontologist who has published many papers and written and collaborated on books about dinosaurs. An authority on Ceratopsians, he has also authored several papers and textbooks on hadrosaurs and sauropods, and is a co-editor of The Dinosauria. He is a professor of Vertebrate Paleontology and of Veterinary Anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania.

- Lindon Eaves (born 1944): British behavioral geneticist who has published on topics as diverse as the heritability of religion and psychopathology. In 1996, he and Kenneth Kendler founded the Virginia Institute for Psychiatric and Behavioral Genetics at Virginia Commonwealth University, where he is currently professor emeritus and actively engaged in research and training.[232][233]

- Darrel R. Falk (born 1946): American biologist and the former president of the BioLogos Foundation.[234]

- Charles Foster (born 1962): science writer on natural history, evolutionary biology, and theology. A Fellow of Green Templeton College, Oxford, the Royal Geographical Society, and the Linnean Society of London,[235] Foster has advocated theistic evolution in his book, The Selfless Gene (2009).[236]

- Tyler VanderWeele: American epidemiologist and biostatistician and Professor of Epidemiology in the Departments of Epidemiology and Biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. He is also the co-director of Harvard University's Initiative on Health, Religion and Spirituality, the director of their Human Flourishing Program, and a faculty affiliate of the Harvard Institute for Quantitative Social Science. His research has focused on the application of causal inference to epidemiology, as well as on the relationship between religion and health.[237][238]

- John Gurdon (born 1933): British developmental biologist. In 2012, he and Shinya Yamanaka were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery that mature cells can be converted to stem cells. In an interview with EWTN.com on the subject of working with the Vatican in dialogue, he says "I'm not a Roman Catholic. I'm a Christian, of the Church of England...I've never seen the Vatican before, so that's a new experience, and I'm grateful for it."[239]

- Brian Heap (born 1935): biologist who was Master of St Edmund's College, University of Cambridge and was a founding member of the International Society for Science and Religion.[240][241]

- Malcolm Jeeves (born 1926): British neuropsychologist who is Emeritus Professor of Psychology at the University of St. Andrews, and was formerly president of The Royal Society of Edinburgh. He established the department of psychology at University of St. Andrews.[242]

- Harold G. Koenig (born 1951): professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Duke University and leading researcher on the effects of religion and spirituality on health. He is also a senior fellow in the Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development at Duke.[243][244][245]

- Larry Kwak (born 1959): renowned American cancer researcher who works at City of Hope National Medical Center. He was formerly chairman of the Department of Lymphoma and Myeloma and co-director of the Center for Cancer Immunology Research at MD Anderson Hospital.[246] He was included on Time's list of 2010's most influential people.

- Doug Lauffenburger (born 1953): American bioengineer who is the Ford Professor of Biological Engineering, Chemical Engineering, and Biology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He is a member of the David H. Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research and MIT Center for Gynepathology Research.[247]

- Noella Marcellino (born 1951): American Benedictine nun with a degree in microbiology. Her field of interests include fungi and the effects of decay and putrefaction.[248]

- Paul R. McHugh (born 1931): American psychiatrist whose research has focused on the neuroscientific foundations of motivated behaviors, psychiatric genetics, epidemiology, and neuropsychiatry. He is Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and former psychiatrist-in-chief at the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

- Kenneth R. Miller (born 1948): molecular biologist at Brown University who wrote Finding Darwin's God ISBN 0-06-093049-7.[249]

- Simon C. Morris (born 1951): British paleontologist and evolutionary biologist who made his reputation through study of the Burgess Shale fossils. He has held the chair of Evolutionary Palaeobiology in the Department of Earth Sciences, University of Cambridge since 1995. He was the co-winner of a Charles Doolittle Walcott Medal and also won a Lyell Medal. He is active in the Faraday Institute for study of science and religion and is also noted on discussions concerning the idea of theistic evolution.[250][251][252]

- William Newsome (born 1952): neuroscientist at Stanford University. A member of the National Academy of Sciences. Co-chair of the BRAIN Initiative, "a rapid planning effort for a ten-year assault on how the brain works."[253] He has written about his faith: "When I discuss religion with my fellow scientists...I realize I am an oddity — a serious Christian and a respected scientist."[254]

- Martin Nowak (born 1965): evolutionary biologist and mathematician best known for evolutionary dynamics. He teaches at Harvard University and is also a member of the Board of Advisers of the Templeton Foundation.[255][256]

- Bennet Omalu (born 1968): Nigerian-American physician, forensic pathologist, and neuropathologist who was the first to discover and publish findings of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in American football players. He is a professor in the UC Davis Department of Medical Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.[257]

- Ghillean Prance (born 1937): botanist involved in the Eden Project. He is a former president of Christians in Science.[258]

- Joan Roughgarden (born 1946): evolutionary biologist who has taught at Stanford University since 1972. She wrote the book Evolution and Christian Faith: Reflections of an Evolutionary Biologist.[259]

- Mary Higby Schweitzer: paleontologist at North Carolina State University who believes in the synergy of the Christian faith and the truth of empirical science.[260][261]

- Andrew Wyllie: Scottish pathologist who discovered the significance of natural cell death, later naming the process apoptosis. Prior to retirement, he was head of the Department of Pathology at the University of Cambridge.[262]

Chemistry

- Peter Agre (born January 30, 1949): American physician, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor, and molecular biologist at Johns Hopkins University who was awarded the 2003 Nobel Prize in Chemistry (which he shared with Roderick MacKinnon) for his discovery of aquaporins. Agre is a Lutheran.[263]

- Andrew B. Bocarsly (born 1954): American chemist known for his research in electrochemistry, photochemistry, solids state chemistry, and fuel cells. He is a professor of chemistry at Princeton University.[264]

- Gerhard Ertl (born 1936): 2007 Nobel Prize winner in Chemistry. He has said in an interview that "I believe in God. (...) I am a Christian and I try to live as a Christian (...) I read the Bible very often and I try to understand it."[265]

- Brian Kobilka (born 1955): American Nobel Prize winner of Chemistry in 2012, and is professor in the departments of Molecular and Cellular Physiology at Stanford University School of Medicine. Kobilka attends the Catholic Community at Stanford, California.[266] He received the Mendel Medal from Villanova University, which it says "honors outstanding pioneering scientists who have demonstrated, by their lives and their standing before the world as scientists, that there is no intrinsic conflict between science and religion."[267]

- Todd Martinez (born 1968): American theoretical chemist who is a professor of chemistry at Stanford University and a professor of photon science at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory. His research focuses primarily on developing first-principles approaches to chemical reaction dynamics, starting from the fundamental equations of quantum mechanics.[268]

- Artem R. Oganov (born 1975): Russian theoretical crystallographer, mineralogist, chemist, physicist, and materials scientist. He is a parishioner of St. Louis Catholic Church in Moscow.[269]

- Henry F. Schaefer, III (born 1944): American computational and theoretical chemist, and one of the most highly cited scientists in the world with a Thomson Reuters H-Index of 116. He is the Graham Perdue Professor of Chemistry and director of the Center for Computational Chemistry at the University of Georgia.[270]

- Troy Van Voorhis: American chemist who is currently the Haslam and Dewey Professor of Chemistry at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[271]

- John White (chemist): Australian chemist who is currently Professor of Physical and Theoretical Chemistry, Research School of Chemistry, at the Australian National University. He is a past president, Royal Australian Chemical Institute and president of Australian Institute of Nuclear Science and Engineering.[272]

Physics and astronomy

- Stephen Barr (born 1953): physicist who worked at Brookhaven National Laboratory and contributed papers to Physical Review as well as Physics Today. He also is a Catholic who writes for First Things and wrote Modern Physics and Ancient Faith. He teaches at the University of Delaware.[273]

- Jocelyn Bell Burnell (born 1943): astrophysicist from Northern Ireland who discovered the first radio pulsars in 1967. She is currently visiting professor of astrophysics at the University of Oxford.

- Arnold O. Benz (born 1945): Swiss astrophysicist, currently professor emeritus at ETH Zurich. He is known for his research in plasma astrophysics,[274] in particular heliophysics, and received honorary doctoral degrees from the University of Zurich and The University of the South for his contributions to the dialog with theology.[275][276]

- Katherine Blundell: British astrophysicist who is a professor of astrophysics at the University of Oxford and a supernumerary research fellow at St John's College, Oxford. Her research investigates the physics of active galaxies such as quasars and objects in the Milky Way such as microquasars.[277]

- Stephen Blundell (born 1967): British physicist who is a professor of physics at the University of Oxford. He was the previously head of Condensed Matter Physics at Oxford. His research is concerned with using muon-spin rotation and magnetoresistance techniques to study a range of organic and inorganic materials.[278]

- Andrew Briggs (born 1950): British quantum physicist who is Professor of Nanomaterials at the University of Oxford. He is best known for his early work in acoustic microscopy and his current work in materials for quantum technologies.[279][280]

- Joan Centrella: American astrophysicist known for her research on general relativity, gravity waves, gravitational lenses, and binary black holes. She is the former deputy director of the Astrophysics Science Division at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, and is Executive in Residence for Science and Technology Policy at West Virginia University.[281][282][283]

- Raymond Chiao (born 1940): American physicist renowned for his experimental work in quantum optics. He is currently an emeritus faculty member at the University of California, Merced Physics Department, where he is conducting research on gravitational radiation.[284][285]

- Gerald B. Cleaver: professor in the department of physics at Baylor University and head of the Early Universe Cosmology and Strings (EUCOS) division of Baylor's Center for Astrophysics, Space Physics & Engineering Research (CASPER). His research specialty is string phenomenology and string model building. He is linked to BioLogos and among his lectures are ""Faith and the New Cosmology."[286][287]

- Guy Consolmagno (born 1952): American Jesuit astronomer who works at the Vatican Observatory.

- Cees Dekker (born 1959): Dutch physicist and Distinguished University Professor at the Technical University of Delft. He is known for his research on carbon nanotubes, single-molecule biophysics, and nanobiology. Ten of his group publications have been cited more than 1000 times, 64 papers got cited more than 100 times, and in 2001, his group work was selected as "breakthrough of the year" by the journal Science.[288]

- George Francis Rayner Ellis (born 1939): professor of Complex Systems in the department of mathematics and applied mathematics at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. He co-authored The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time with University of Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking, published in 1973, and is considered one of the world's leading theorists in cosmology. He is an active Quaker and in 2004 he won the Templeton Prize.

- Paul Ewart (born 1948): professor of Physics and head of the sub-department of Atomic and Laser Physics within the Department of Physics, University of Oxford, and fellow and tutor in physics at Worcester College, Oxford, where he is now an emeritus fellow.[289][290][291][292]

- Gerald Gabrielse (born 1951): American physicist renowned for his work on anti-matter. He is the George Vasmer Leverett Professor of Physics at Harvard University, incoming board of trustees professor of physics and director of the Center for Fundamental Physics at Low Energy at Northwestern University.[293][294]

- Pamela L. Gay (born 1973): American astronomer, educator and writer, best known for her work in astronomical podcasting. Doctor Gay received her PhD from the University of Texas, Austin, in 2002.[295] Her position as both a skeptic and Christian has been noted upon.[296]

- Karl W. Giberson (born 1957): Canadian physicist and evangelical, formerly a physics professor at Eastern Nazarene College in Massachusetts, Giberson is a prolific author specializing in the creation-evolution debate and who formerly served as vice president of the BioLogos Foundation.[297] He has published several books on the relationship between science and religion, such as The Language of Science and Faith: Straight Answers to Genuine Questions and Saving Darwin: How to be a Christian and Believe in Evolution.

- Owen Gingerich (born 1930): Mennonite astronomer who went to Goshen College and Harvard. He is Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and of the History of Science at Harvard University and Senior Astronomer Emeritus at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. Mr. Gingerich has written about people of faith in science history.[298][299]

- J. Richard Gott (born 1947): professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University. He is known for developing and advocating two cosmological theories with the flavor of science fiction: Time travel and the Doomsday argument. When asked of his religious views in relation to his science, Gott responded that "I’m a Presbyterian. I believe in God; I always thought that was the humble position to take. I like what Einstein said: "God is subtle but not malicious." I think if you want to know how the universe started, that's a legitimate question for physics. But if you want to know why it's here, then you may have to know—to borrow Stephen Hawking's phrase—the mind of God."[300]

- Monica Grady (born 1958): leading British space scientist, primarily known for her work on meteorites. She is currently Professor of Planetary and Space Science at the Open University.

- Robert Griffiths (born 1937): noted American physicist at Carnegie Mellon University. He has written on matters of science and religion.[301]

- Frank Haig (born 1928): American physics professor

- Daniel E. Hastings: American physicist renowned for his contributions in spacecraft and space system-environment interactions, space system architecture, and leadership in aerospace research and education.[302] He is currently the Cecil and Ida Green Education Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[303]

- Michał Heller (born 1936): Catholic priest, a member of the Pontifical Academy of Theology, a founding member of the International Society for Science and Religion. He also is a mathematical physicist who has written articles on relativistic physics and Noncommutative geometry. His cross-disciplinary book Creative Tension: Essays on Science and Religion came out in 2003. For this work he won a Templeton Prize.[note 6][304]

- Antony Hewish (born 1924): British radio astronomer who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974 (together with Martin Ryle) for his work on the development of radio aperture synthesis and its role in the discovery of pulsars. He was also awarded the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1969. Hewish is a Christian.[305] Hewish also wrote in his introduction to John Polkinghorne's 2009 Questions of Truth, "The ghostly presence of virtual particles defies rational common sense and is non-intuitive for those unacquainted with physics. Religious belief in God, and Christian belief ... may seem strange to common-sense thinking. But when the most elementary physical things behave in this way, we should be prepared to accept that the deepest aspects of our existence go beyond our common-sense understanding."[306]

- Joseph Hooton Taylor Jr. (born 1941): American astrophysicist and Nobel Prize laureate in Physics for his discovery with Russell Alan Hulse of a "new type of pulsar, a discovery that has opened up new possibilities for the study of gravitation." He was the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Physics at Princeton University.[307]

- Colin Humphreys (born 1941): British physicist. He is the former Goldsmiths’ Professor of Materials Science and a current director of research at the University of Cambridge, professor of experimental physics at the Royal Institution in London and a Fellow of Selwyn College, Cambridge. Humphreys also "studies the Bible when not pursuing his day-job as a materials scientist."[308]

- Ian Hutchinson (scientist): physicist and nuclear engineer. He is currently Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering at the Plasma Science and Fusion Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Christopher Isham (born 1944): theoretical physicist who developed HPO formalism. He teaches at Imperial College London. In addition to being a physicist, he is a philosopher and theologian.[309][310]

- Stephen R. Kane (born 1973): Australian astrophysicist who specializes in exoplanetary science. He is a professor of Astronomy and Planetary Astrophysics at the University of California, Riverside and a leading expert on the topic of planetary habitability and the habitable zone of planetary systems.[311][312]

- Ard Louis: professor in theoretical physics at the University of Oxford. Prior to his post at Oxford he taught theoretical chemistry at the University of Cambridge where he was also director of studies in Natural Sciences at Hughes Hall. He has written for The BioLogos Forum.[313]

- Jonathan Lunine (born 1959): American planetary scientist and physicist, and the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences and director of the Center for Radiophysics and Space Research at Cornell University.[314]

- Juan Maldacena (born 1968): Argentine theoretical physicist and string theorist, best known for the most reliable realization of the holographic principle – the AdS/CFT correspondence.[315] He is a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey and in 2016 became the first Carl P. Feinberg Professor of Theoretical Physics in the institute's School of Natural Sciences.

- Robert B. Mann (born 1955[316]): professor of physics, University of Waterloo[317] and Perimeter Institute.[318] He was president of Canadian Association of Physicists (2009–10)[319] and of the Canadian Scientific & Christian Affiliation (CSCA).[320] He was a plenary speaker at the 2018 conference of the CSCA and Trinity Western University.[321]

- Ross H. McKenzie (born 1960): Australian physicist who is Professor of Physics at the University of Queensland. From 2008 to 2012 he held an Australian Professorial Fellowship from the Australian Research Council. He works on quantum many-body theory of complex materials ranging from organic superconductors to biomolecules to rare-earth oxide catalysts.[322]

- Tom McLeish (born 1962): theoretical physicist whose work is renowned for increasing our understanding of the properties of soft matter. He was professor in the Durham University Department of Physics and director of the Durham Centre for Soft Matter. He is now the first chair of natural philosophy at the University of York.[323]

- Charles W. Misner (born 1932): American physicist and one of the authors of Gravitation. His work has provided early foundations for studies of quantum gravity and numerical relativity. He is Professor Emeritus of Physics at the University of Maryland.[324]

- Barth Netterfield (born 1968): Canadian astrophysicist and professor in the department of astronomy and the department of physics at the University of Toronto.[325]

- Don Page (born 1948):[326] Canadian theoretical physicist and practicing Evangelical Christian, Page is known for having published several journal articles with Stephen Hawking.[327][328]

- William Daniel Phillips (born 1948): 1997 Nobel Prize laureate in Physics (1997) who is a founding member of The International Society for Science and Religion.[329]

- Karin Öberg (born 1982): Swedish astrochemist,[330] professor of Astronomy at Harvard University and leader of the Öberg Astrochemistry Group at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.[331]

- Eric Priest (born 1943): astrophysicist and authority on Solar Magnetohydrodynamics who won the George Ellery Hale Prize among others. He has spoken on Christianity and Science at the University of St. Andrews where he is an emeritus professor and is a member of the Faraday Institute. He is also interested in prayer, meditation, and Christian psychology.[332]

- Marlan Scully (born 1939): American physicist best known for his work in theoretical quantum optics. He is a professor at Texas A&M University and Princeton University. Additionally, in 2012 he developed a lab at the Baylor Research and Innovation Collaborative in Waco, Texas.[333]

- Russell Stannard (born 1931): British particle physicist who has written several books on the relationship between religion and science, such as Science and the Renewal of Belief, Grounds for Reasonable Belief and Doing It With God?.[334]

- Andrew Steane: British physicist who is Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford. His major works to date are on error correction in quantum information processing, including Steane codes. He was awarded the Maxwell Medal and Prize of the Institute of Physics in 2000.[335]

- Michael G. Strauss (born 1958): American experimental particle physicist. He is a David Ross Boyd Professor at the University of Oklahoma in Norman[336] and a member of the ATLAS experiment at CERN that discovered the Higgs Boson in 2012.[337] He is author of the book The Creator Revealed: A Physicist Examines the Big Bang and the Bible[338] and one of the general editors of Zondervan's Dictionary of Christianity and Science.[339]

- Jeffery Lewis Tallon (born 1948): New Zealand physicist specializing in high-temperature superconductors. He was awarded the Rutherford Medal,[340] the highest award in New Zealand science. In the 2009 Queen's Birthday Honours he was appointed a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to science.[341]

- Frank J. Tipler (born 1947): mathematical physicist and cosmologist, holding a joint appointment in the Departments of Mathematics and Physics at Tulane University. Tipler has authored books and papers on the Omega Point, which he claims is a mechanism for the resurrection of the dead. His theological and scientific theorizing are not without controversy, but he has some supporters; for instance, Christian theologian Wolfhart Pannenberg has defended his theology,[342] and physicist David Deutsch has incorporated Tipler's idea of an Omega Point.[343]

- Daniel C. Tsui (born 1939): Chinese-born American physicist whose areas of research included electrical properties of thin films and microstructures of semiconductors and solid-state physics. In 1998 Tsui was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the discovery of the fractional quantum Hall effect. He was the Arthur LeGrand Doty Professor of Electrical Engineering at Princeton University.[344][345]

- Rogier Windhorst (born 1955): Dutch astrophysicist who is Foundation Professor of Astrophysics at Arizona State University and co-director of the ASU Cosmology Initiative. He is one of the six Interdisciplinary Scientists worldwide for the James Webb Space Telescope, and member of the JWST Flight Science Working Group.[311][312]

- Jennifer Wiseman: Chief of the Laboratory for Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. An aerial of the center is shown. In addition she is a co-discoverer of 114P/Wiseman-Skiff. In religion is a Fellow of the American Scientific Affiliation and on June 16, 2010, became the new director for the American Association for the Advancement of Science's Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion.[346]

- Antonino Zichichi (born 1929): Italian nuclear physicist and former president of the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare. He has worked with the Vatican on relations between the Church and Science.[347][348]

Earth sciences

- Lorence G. Collins (born 1931): American petrologist, best known for his extensive research on metasomatism. He is known for his opposition to creationism and has written several articles presenting his Christian philosophy.[349]

- Katharine Hayhoe (born 1972): atmospheric scientist and professor of political science at Texas Tech University, where she is director of the Climate Science Center.[350]

- Mike Hulme (born 1960): professor of human geography in the department of geography at the University of Cambridge. He was formerly professor of Climate and Culture at King's College London (2013–2017) and is the author of Why We Disagree About Climate Change. He has said of his Christian faith, "I believe because I have not discovered a better explanation of beauty, truth and love than that they emerge in a world created – willed into being – by a God who personifies beauty, truth and love."[351]

- John Suppe (born 1943): professor of geology at National Taiwan University, Geosciences Emeritus at Princeton University. He has written articles like "Thoughts on the Epistemology of Christianity in Light of Science."[352]

- Robert (Bob) White: British geophysicist and Professor of Geophysics in the Earth Sciences department at the University of Cambridge. He is director of the Faraday Institute for Science and Religion.[353]

Engineering

- Fred Brooks (born 1931): American computer architect, software engineer, and computer scientist, best known for managing the development of IBM's System/360 family of computers and the OS/360 software support package, then later writing candidly about the process in his seminal book The Mythical Man-Month. Brooks has received many awards, including the National Medal of Technology in 1985 and the Turing Award in 1999. Brooks is an evangelical Christian who is active with InterVarsity Christian Fellowship and chaired the executive committee for the Central Carolina Billy Graham Crusade in 1973.[354]

- John Dabiri (born 1980): Nigerian-American professor of aeronautics and bioengineering at Stanford University, MacArthur Fellow and one of Popular Science magazine's "Brilliant 10" scientists in 2008.[355]

- Raymond Vahan Damadian (born 1936): medical practitioner and inventor who created the MRI (Magnetic Resonance Scanning Machine). He is a young-earth creationist and there was a controversy on why he did not receive the 2003 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, given that he had come up with the idea and worked on the development of the MRI.

- Pat Gelsinger (born 1962): American computer engineer and architect who was the first chief technology officer of Intel Corporation and is currently the CEO of VMware. He was the architect and design manager on the Intel 80486 which provided the processing power needed for the personal computer revolution through the 1980s into the 1990s.[356][357]

- Donald Knuth (born 1938): American computer scientist, mathematician, and professor emeritus at Stanford University. He is the author of the multi-volume work The Art of Computer Programming and 3:16 Bible Texts Illuminated (1991), ISBN 0-89579-252-4.[358]

- Michael C. McFarland (born 1948): American computer scientist and president of the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts

- Rosalind Picard (born 1962): professor of Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, director and also the founder of the Affective Computing Research Group at the MIT Media Lab, co-director of the Things That Think Consortium, and chief scientist and co-founder of Affectiva. Picard says that she was raised an atheist, but converted to Christianity as a young adult.[359]

- Daniel E. Hastings: professor and department head of Aeronautics and Astronautics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology[360]

- Peter Robinson (computer scientist) (born 1952): British computer scientist who is Professor of Computer Technology at the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory in England, where he works in the Rainbow Group on computer graphics and interaction.[361][362]

- Lionel Tarassenko: holder of the chair in electrical engineering at the University of Oxford since 1997, and is most noted for his work on the applications of neural networks. He led the development of the Sharp LogiCook, the first microwave oven to incorporate neural networks.[363][364]

- James Tour (born 1959): professor of computer science and materials at Rice University, Texas; recognized as one of the world's leading nano-engineers.[365]

- George Varghese (born 1960): currently the chancellor's professor in the department of computer science at UCLA and former principal researcher at Microsoft Research.[366][367]

- Larry Wall (born September 27, 1954): creator of Perl, a programming language.[368]

Others