Psychedelic rock

| Psychedelic rock | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Cultural origins | Mid 1960s, United States and United Kingdom |

| Typical instruments | |

| Derivative forms | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Regional scenes | |

| Local scenes | |

| Other topics | |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

|

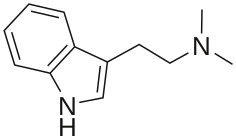

Psychedelic rock is a style of rock music that is inspired or influenced by psychedelic culture and attempts to replicate and enhance the mind-altering experiences of psychedelic drugs, most notably LSD. It often uses new recording techniques and effects and sometimes draws on sources such as the ragas and drones of Indian music.

It was pioneered by pop and rock musicians including the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Byrds, emerging as a genre during the mid-1960s among folk-, blues-, and jazz-based bands in the United Kingdom and United States. Its peak years were between 1966 and 1969 with milestone events such as the 1967 Summer of Love and the 1969 Woodstock Rock Festival, becoming an international musical movement and associated with a widespread counterculture, before beginning a decline as changing attitudes, the loss of some key individuals and a back-to-basics movement, led surviving performers to move into new musical areas.

In the 1960s, there were two main types of psychedelic rock: the whimsical British variant, and the harder American West Coast acid rock. The terms "psychedelic rock" and "acid rock" are often deployed interchangeably, but "acid rock" sometimes refers to the more extreme ends of the genre. Psychedelic rock influenced the creation of psychedelic soul and bridged the transition from early blues- and folk music-based rock to progressive rock, glam rock, hard rock and as a result influenced the development of subgenres such as heavy metal. Since the late 1970s it has been revived in various forms of neo-psychedelia.

Characteristics

As a musical style, psychedelic rock attempted to replicate the effects of and enhance the mind-altering experiences of hallucinogenic drugs, incorporating new electronic sound effects and recording effects, extended solos, and improvisation.[1] Major features include:

- electric guitars, often used with feedback, wah wah and fuzzbox effects units;[1]

- elaborate studio effects, such as backwards tapes, panning, phasing, long delay loops, and extreme reverb;[2]

- non-Western instruments, specifically those originally used in Indian classical music such as the sitar and tabla;[3]

- a strong keyboard presence, especially electric organs, harpsichords, or the Mellotron (an early tape-driven 'sampler');[4]

- extended instrumental solos, especially guitar solos, or jams;[5]

- complex song structures, key and time signature changes, modal melodies and drones;[5]

- electronic instruments such as synthesizers and the theremin;[6][7]

- lyrics that made direct or indirect reference to hallucinogenic drugs, as in Jefferson Airplane's "White Rabbit" or Jimi Hendrix's "Purple Haze";[8]

- surreal, whimsical, esoterically or literary-inspired, lyrics.[9][10]

Etymology and acid rock

The term "psychedelic" was first coined in 1956 by psychiatrist Humphry Osmond as an alternative descriptor for hallucinogenic drugs in the context of psychedelic psychotherapy.[11] As the countercultural scene developed in San Francisco, the terms acid rock and psychedelic rock were used in 1966 to describe the new drug-influenced music[12] and were being widely used by 1967.[13] The terms psychedelic rock and acid rock are often used interchangeably,[8] but acid rock may be distinguished as a more extreme variation that was heavier, louder, relied on long jams,[14] focused more directly on LSD, and made greater use of distortion.[15]

History

Background

From the second half of the 1950s, Beat Generation writers like William Burroughs, Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg[16] wrote about and took drugs, including cannabis and Benzedrine, raising awareness and helping to popularise their use.[17] In the same period Lysergic acid diethylamide, better known as LSD, or "acid" (at the time a legal drug), began to be used in the US and UK as an experimental treatment, initially promoted as a potential cure for mental illness.[18]

In the early 1960s the use of LSD and other hallucinogens was advocated by proponents of the new "consciousness expansion", such as Timothy Leary, Alan Watts, Aldous Huxley and Arthur Koestler,[19][20] their writings profoundly influenced the thinking of the new generation of youth.[21] The sensory effects of LSD may include hallucinations of colored patterns, crawling geometric patterns, after image-like trails of moving objects ("tracers"), synthaesia and auditory effects such as an echo-like distortion of sounds and a general intensification of the experience of music.[citation needed]

By the mid-1960s, the psychedelic life-style had already developed in California, and an entire subculture developed. This was particularly true in San Francisco, due in part to the first major underground LSD factory, established there by Owsley Stanley.[13] There was also an emerging music scene of folk clubs, coffee houses and independent radio stations catering to a population of students at nearby Berkeley, and to free thinkers that had gravitated to the city.[22] From 1964, the Merry Pranksters, a loose group that developed around novelist Ken Kesey, sponsored the Acid Tests, a series of events based around the taking of LSD (supplied by Stanley), accompanied by light shows, film projection and discordant, improvised music known as the psychedelic symphony.[23][24] The Pranksters helped popularize LSD use through their road trips across America in a psychedelically-decorated school bus, which involved distributing the drug and meeting with major figures of the beat movement, and through publications about their activities such as Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968).[25]

Precursors

Music critic Richie Unterberger states: "Trying to pin down the first psychedelic record is nearly as elusive as trying to name the first rock & roll record. Far-fetched claims have been advanced for songs running from the Tornados' futuristic 1962 number one instrumental 'Telstar' to the Dave Clark Five's massively reverb-laden 'Any Way You Want It'."[10] There had long been a culture of drug use among jazz and blues musicians, and, in the early 1960s, use of drugs (including cannabis, peyote, mescaline and LSD[26]) had begun to grow among folk and rock musicians, who also began to include drug references in their songs.[27] The first mention of LSD on a rock record was the Gamblers' 1960 surf instrumental "LSD 25".[28][nb 1] New York folk musician Peter Stampfel claimed to be the first to use the word "psychedelic" in a song lyric (The Holy Modal Rounders' version of "Hesitation Blues", 1963).[29] XTC's Andy Partridge identifies novelty records as the direct antecedent to psychedelia: "They use exactly the same techniques—sped-up bits, slowed-down bits, too much echo, too much reverb, that bit goes backwards. When the generation that grew up on kids' novelty records began making records for themselves, it came out as psychedelia. That genre is just grown-up novelty songs! ... There was no transition to be made. You go from things like 'Flying Purple People Eater' to 'I Am the Walrus'. They go hand-in-hand."[30]

In terms of bridging the relationship between music and hallucinogens, the Beatles and the Beach Boys were the most pivotal.[31] In 1965, the Beach Boys' leader Brian Wilson started experimenting with song composition while under the influence of psychedelic drugs,[32] and after being introduced to cannabis by Bob Dylan, members of the Beatles also began using LSD.[10] The phenomenal success of these two bands allowed them the means to experiment with new technology over entire albums.[33] The Beatles' May 1966 B-side "Rain" was the first pop recording to include reversed sounds,[34] and drug references began to appear with the Beatles' "Day Tripper" (December 1965)[35][nb 2] and the Beach Boys' "Sloop John B" (March 1966).[36][nb 3]

In Unterberger's opinion, the Byrds, emerging from the Californian folk scene, were more responsible than the Beatles for "sounding the psychedelic siren".[10] Drug use and attempts at psychedelic music moved out of acoustic folk-based music towards rock soon after the Byrds "plugged in" to produce a chart topping version of Dylan's "Mr. Tambourine Man" in the summer of 1965, which became a folk rock standard.[37][38] In the song's lyric, the narrator requests: "Take me on a trip upon your magic swirling ship".[13][nb 4] A number of Californian-based folk acts followed the Byrds into folk-rock, bringing their psychedelic influences with them, to produce the "San Francisco Sound".[10][23][nb 5]

British psychedelic rock, like its American counterpart, also had roots in the folk scene. Blues, drugs, jazz and eastern influences had featured since 1964 in the work of Davy Graham and Bert Jansch.[39] The Beatles introduced guitar feedback with "I Feel Fine" (1964)[10] and incorporated drug-inspired drone on "Ticket to Ride" (1965).[40] The Kinks and the Yardbirds also incorporated droning guitars to mimic the qualities of the sitar,[41] but the Beatles' "Norwegian Wood" (December 1965) marked the first released recording on which a member of a Western rock group played an Indian instrument.[42] The song is generally credited for sparking a musical craze for the sound of the sitar in the mid-1960s – a trend which would later be associated with the growth of the essence of psychedelic rock.[41][nb 6]

The San Francisco music scene developed as The Fillmore, the Avalon Ballroom, and The Matrix began booking local rock bands on a nightly basis. The first Trips Festival, sponsored by the Merry Pranksters and held at the Longshoremen's Hall in January 1966, saw The Grateful Dead, and Big Brother and the Holding Company play to an audience of 10,000, giving many their first encounter with both acid rock, with its long instrumentals and unstructured jams, and LSD.[citation needed] A major figure in the expansion of the genre was promoter Bill Graham, whose first rock concert in 1965 was a benefit that included Allen Ginsberg and the then unknown Jefferson Airplane on the bill. He produced shows attracting most of the major psychedelic rock bands and operated The Fillmore. When this proved too small he took over Winterland and then the Fillmore West (in San Francisco) and the Fillmore East (in New York City), where the major rock artists, from both the US and the UK, came to play.[43]

1966–69: Peak years

Beginnings and early records

Music journalists Pete Prown and Harvey P. Newquist locate the "peak years" of psychedelic rock between 1966 and 1969.[1] Author Jim DeRogatis says the birth date of psychedelic (or acid) rock is "best listed at 1966".[45] In March 1966, the Byrds moved rapidly away from folk rock with their single "Eight Miles High", which made use of free jazz and Indian ragas, and the lyrics of which were widely taken to refer to drug use.[10] The result of this directness was limited airplay, and there was a similar reaction when Dylan, who had also electrified to produce his own brand of folk rock, released "Rainy Day Women ♯ 12 & 35" (April 1966), with its repeating chorus of "Everybody must get stoned!".[46]

Another record often considered one of the earliest in the canon of psychedelic rock is the Beach Boys' album Pet Sounds (May 1966).[47][nb 7] It contained many elements that would be incorporated into psychedelia, with its artful experiments, psychedelic lyrics based on emotional longings and self-doubts, elaborate sound effects and new sounds on both conventional and unconventional instruments.[49][50] Scholar Philip Auslander explains that even though psychedelic music is not normally associated with the Beach Boys, the "odd directions" and experiments in Pet Sounds "put it all on the map. ... basically that sort of opened the door — not for groups to be formed or to start to make music, but certainly to become as visible as say Jefferson Airplane or somebody like that."[31] According to The Kindland's Mike McPadden, the album "ignited a psychedelic pop revolution", inspiring mainstream pop acts to take part in the psychedelic culture.[51]

Like Pet Sounds, the Beatles' album Revolver (August 1966) explored musical soundscapes that could not be replicated on stage, even with the help of an orchestra,[52] and it helped precipitate the psychedelic pop style.[53][nb 8] That same month, the Texas band 13th Floor Elevators debuted with The Psychedelic Sounds of the 13th Floor Elevators. They were the first group to advertise themselves as psychedelic rock, having done so since the end of 1965.[5][nb 9] Psychedelic Sounds was the first album to use "psychedelic" as part of its title.[5] Wondering Sound contributor Rachael Maddux writes that even though Pet Sounds and Psychedelic Sounds are considered early psychedelic rock albums, there are "obvious differences" in their music: "Even the album covers are a study in contrasts."[47]

The first acid (or psychedelic) rock single to break into the top 10 in popular music charts[failed verification] was Count Five's "Psychotic Reaction" (June 1966). As in most early acid rock music, the song's most characteristic element was its replacement of the melodic electric guitar with howling feedback and distortion.[8] By the end of the year, the Beatles and the Beach Boys were the only acts to have high-charting psychedelic rock songs.[55] The Beach Boys' October 1966 single "Good Vibrations" was one of the first pop songs to incorporate psychedelic lyrics and sounds.[56][57][verification needed] As psychedelia gained prominence, Beach Boys-style harmonies would be ingrained into the newer psychedelic pop.[53]

Continued development

From 1967 to 1968, psychedelic rock was the prevailing sound of rock music, either in the whimsical British variant, or the harder American West Coast acid rock.[59] Compared with American psychedelia, British psychedelic music was often more arty in its experimentation, and it tended to stick within pop song structures.[60] Pink Floyd's "Arnold Layne" (January 1967) and "See Emily Play" (May 1967), both written by Syd Barrett, helped set the pattern for British pop-psychedelia.[58] Previous to that year, British media outlets for psychedelic culture were limited to stations like Radio Luxembourg and pirate radio like Radio London, particularly the programmes hosted by DJ John Peel.[61] The growth of underground culture was facilitated by the emergence of alternative weekly publications like IT (International Times) and OZ magazine which featured psychedelic and progressive music together with the counterculture lifestyle, which involved long hair, and the wearing of wild shirts from shops like Mr Fish, Granny Takes a Trip and old military uniforms from Carnaby Street (Soho) and Kings Road (Chelsea) boutiques.[62]

Jefferson Airplane's Surrealistic Pillow (February 1967) was the first album to come out of San Francisco during this era, which sold well enough to bring the city's music scene to the attention of the record industry: from it they took two of the earliest[contradictory] psychedelic hit singles: "White Rabbit" and "Somebody to Love".[63] That same month, the Beatles released the double A-side "Strawberry Fields Forever" and "Penny Lane", which Ian MacDonald says opened a strain of "British pop-pastoral" music explored by late 1960s groups like Pink Floyd, Traffic, Family, and Fairport Convention.[64] Soon, British clubs like the UFO Club, Middle Earth Club, The Roundhouse, the Country Club and the Art Lab were drawing capacity audiences with psychedelic rock and ground-breaking liquid light shows.[65] A major figure in the development of British psychedelia was the American promoter and record producer Joe Boyd, who moved to London in 1966. He co-founded venues including the UFO Club, produced Pink Floyd's first single, "Arnold Layne", and went on to manage folk and folk rock acts including Nick Drake, the Incredible String Band and Fairport Convention.[66][67]

The Summer of Love of 1967 saw a huge number of young people from across America and the world travel to the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, boosting the population from 15,000 to around 100,000.[68] It was prefaced by the Human Be-In event in March and reached its peak at the Monterey Pop Festival in June, the latter helping to make major American stars of Janis Joplin, lead singer of Big Brother and the Holding Company, Jimi Hendrix, and the Who.[69] Existing "British Invasion" acts now joined the psychedelic revolution, including Eric Burdon (previously of The Animals) and The Who, whose The Who Sell Out (December 1967) included psychedelic influenced tracks "I Can See for Miles" and "Armenia City in the Sky".[70] The Incredible String Band's The 5000 Spirits or the Layers of the Onion (July 1967) developed their folk music into full blown psychedelia, which would be a major influence on psychedelic rock.[71]

According to author Edward Macan, there ultimately existed three distinct wings of British psychedelic music.[72] The first was based on a heavy, electric reinterpretation of the blues played by the Rolling Stones, adding guitarist Pete Townshend of the Who's pioneering power chord style to the mix. Groups of this nature were dominated by Cream, the Yardbirds, and Hendrix. [72] The second drew strongly from jazz sources and was represented early on by Traffic, Colosseum, If, and the Canterbury scene spearheaded by Soft Machine and Caravan. Their music was considerably more complex than the Cream/Hendrix/Yardbirds approach.[73] The third wing was represented by the Moody Blues, Pink Floyd, and the Nice, who were influenced by the later music of the Beatles, unlike the other two wings.[73] Several of the English psychedelic bands who followed in the wake of the Beatles' psychedelic album Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band (June 1967) developed characteristics of the Beatles' music (specifically their classical influence) further than either the Beatles or contemporaneous West Coast psychedelic bands.[74]

International expansion

The US and UK were the major centres of psychedelic music, but in the late 1960s scenes began to develop across the world, including continental Europe, Australasia, Asia and south and Central America.[75]

In the later 1960s psychedelic scenes developed in a large number of countries in continental Europe, including the Netherlands with bands like The Outsiders,[76] Denmark where it was pioneered by Steppeulvene,[77] and Germany, where musicians began to fuse music of psychedelia and the electronic avant-garde. 1968 saw the first major German rock festival in Essen,[78] and the foundation of the Zodiak Free Arts Lab in Berlin by Hans-Joachim Roedelius, and Conrad Schnitzler, which helped bands like Tangerine Dream and Amon Düül achieve cult status.[79]

A thriving psychedelic music scene in Cambodia, influenced by psychedelic rock and soul broadcast by US forces radio in Vietnam,[80] was pioneered by artists such as Sinn Sisamouth and Ros Sereysothea.[81] In South Korea, Shin Jung-Hyeon, often considered the godfather of Korean rock, played psychedelic-influenced music for the American soldiers stationed in the country. Following Shin Jung-Hyeon, the band San Ul Lim (Mountain Echo) often combined psychedelic rock with a more folk sound.[82] In Turkey, Anatolian rock artist Erkin Koray blended classic Turkish music and Middle Eastern themes into his psychedelic-driven rock, helping to found the Turkish rock scene with artists such as Cem Karaca, Mogollar and Baris Manco.[83]

Decline

Psychedelic trends climaxed in the 1969 Woodstock festival, which saw performances by most of the major psychedelic acts, including Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, and the Grateful Dead.[84] By the end of the 1960s, psychedelic rock was in retreat. In 1966, LSD had been made illegal in the US and UK.[85] In 1969, the murders of Sharon Tate and Leno and Rosemary LaBianca by Charles Manson and his "family" of followers, claiming to have been inspired by Beatles' songs such as "Helter Skelter", has been seen as contributing to an anti-hippie backlash.[86] At the end of the same year, the Altamont Free Concert in California, headlined by the Rolling Stones, became notorious for the fatal stabbing of black teenager Meredith Hunter by Hells Angel security guards.[87]

Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys,[56] Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones, Peter Green of Fleetwood Mac and Syd Barrett of Pink Floyd were early "acid casualties", helping to shift the focus of the respective bands of which they had been leading figures.[88] Some groups, such as the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Cream, broke up.[89] Jimi Hendrix died in London in September 1970, shortly after recording Band of Gypsys (1970), Janis Joplin died of a heroin overdose in October 1970 and they were closely followed by Jim Morrison of the Doors, who died in Paris in July 1971.[90] Many surviving acts moved away from psychedelia into either more back-to-basics "roots rock", traditional-based, pastoral or whimsical folk, the wider experimentation of progressive rock, or riff-based heavy rock.[10]

Influence

Other genres

Following the lead of Hendrix in rock, psychedelia began to influence African American musicians, particularly the stars of the Motown label.[91] This psychedelic soul was influenced by the civil rights movement, giving it a darker and more political edge than much acid rock.[91] Building on the funk sound of James Brown, it was pioneered from about 1968 by Sly and the Family Stone and The Temptations. Acts that followed them into this territory included the Supremes, The Chambers Brothers, The 5th Dimension,[92] Edwin Starr and the Undisputed Truth.[91] George Clinton's interdependent Funkadelic and Parliament ensembles and their various spin-offs took the genre to its most extreme lengths making funk almost a religion in the 1970s,[93] producing over forty singles, including three in the US top ten, and three platinum albums.[94] While psychedelic rock began to waver at the end of the 1960s, psychedelic soul continued into the 1970s, peaking in popularity in the early years of the decade, and only disappearing in the late 1970s as tastes began to change.[91] Acts like Earth, Wind and Fire, Kool and the Gang and Ohio Players, who began as psychedelic soul artists, incorporated its sounds into funk music and eventually the disco which partly replaced it.[95]

Rock music

Many of the British musicians and bands that had embraced psychedelia went on to create progressive rock in the 1970s, including Pink Floyd, Soft Machine and members of Yes. King Crimson's album In the Court of the Crimson King (1969) has been seen as an important link between psychedelia and progressive rock.[96] While bands such as Hawkwind maintained an explicitly psychedelic course into the 1970s, most dropped the psychedelic elements in favour of wider experimentation.[97] The incorporation of jazz into the music of bands like Soft Machine and Can also contributed to the development of the jazz rock of bands like Colosseum.[98] As they moved away from their psychedelic roots and placed increasing emphasis on electronic experimentation, German bands like Kraftwerk, Tangerine Dream, Can and Faust developed a distinctive brand of electronic rock, known as kosmische musik, or in the British press as "Kraut rock".[99] The adoption of electronic synthesisers, pioneered by Popol Vuh from 1970, together with the work of figures like Brian Eno (for a time the keyboard player with Roxy Music), would be a major influence on subsequent electronic rock.[100]

Psychedelic rock, with its distorted guitar sound, extended solos and adventurous compositions, has been seen as an important bridge between blues-oriented rock and later heavy metal. American bands whose loud, repetitive psychedelic rock emerged as early heavy metal included the Amboy Dukes and Steppenwolf.[8] From England, two former guitarists with the Yardbirds, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, moved on to form key acts in the genre, The Jeff Beck Group and Led Zeppelin respectively.[101] Other major pioneers of the genre had begun as blues-based psychedelic bands, including Black Sabbath, Deep Purple, Judas Priest and UFO.[101][102] Psychedelic music also contributed to the origins of glam rock, with Marc Bolan changing his psychedelic folk duo into rock band T. Rex and becoming the first glam rock star from 1970.[103] From 1971 David Bowie moved on from his early psychedelic work to develop his Ziggy Stardust persona, incorporating elements of professional make up, mime and performance into his act.[104]

See also

Notes

- ^ Their keyboardist, Bruce Johnston, would go on to join the Beach Boys in 1965. He would recall: "[LSD is] something I've never thought about and never done."[28]

- ^ And more explicitly in "Doctor Robert" (August 1966)[35]

- ^ The Rolling Stones had drug references and psychedelic hints in their singles "19th Nervous Breakdown" (February 1966) and "Paint It, Black" (May 1966), the latter featuring drones and sitar.[10]

- ^ Whether this was intended as a drug reference was unclear, but the line would enter rock music when the song was a hit for the Byrds later in the year.[13] Dylan indicated that he had smoked cannabis, but has denied using hard drugs. Nevertheless, his lyrics would continue to contain apparent drug references.[25]

- ^ Particularly prominent[according to whom?] products of the scene were The Grateful Dead (who had effectively become the house band of the Acid Tests),[24] Country Joe and the Fish, The Great Society, Big Brother and the Holding Company, The Charlatans, Moby Grape, Quicksilver Messenger Service and Jefferson Airplane.[10]

- ^ Previously, Indian instrumentation had been included in Ken Thorne's orchestral score for the band's Help! film soundtrack.[42]

- ^ Brian Boyd of The Irish Times credits the Byrds' Fifth Dimension (July 1966) with being the first psychedelic album.[48]

- ^ Revolver also featured the Beatles' first psychedelic song: "Tomorrow Never Knows".[54]

- ^ The term was first used in print in the Austin American Statesman in an article about the band titled "Unique Elevators shine with psychedelic rock", dated 10 February 1966.[5]

References

- ^ a b c Prown & Newquist 1997, p. 48.

- ^ S. Borthwick and R. Moy, Popular Music Genres: an Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1745-0, pp. 52–4.

- ^ R. Rubin and J. P. Melnick, Immigration and American Popular Culture: an Introduction (New York, NY: New York University Press, 2007), ISBN 0-8147-7552-7, pp. 162–4.

- ^ D. W. Marshall, Mass Market Medieval: Essays on the Middle Ages in Popular Culture (Jefferson NC: McFarland, 2007), ISBN 0-7864-2922-4, p. 32.

- ^ a b c d e M. Hicks, Sixties Rock: Garage, Psychedelic, and Other Satisfactions Music in American Life (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000), ISBN 0-252-06915-3, pp. 64–6.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 230.

- ^ R. Unterberger, Samb Hicks, Jennifer Dempsey, "Music USA: the Rough Guide", (Rough Guides, 1999), ISBN 1-85828-421-X, p. 391.

- ^ a b c d Browne & Browne 2001, p. 8.

- ^ G. Thompson, Please Please Me: Sixties British Pop, Inside Out (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), ISBN 0-19-533318-7, p. 197.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1322–1323.

- ^ N. Murray, Aldous Huxley: A Biography (Hachette, 2009), ISBN 0-7481-1231-6, p. 419.

- ^ "Logical Outcome of fifty years of art", LIFE, 9 September 1966, p. 68.

- ^ a b c d DeRogatis 2003, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Psychedelic rock at AllMusic

- ^ Eric V. d. Luft, Die at the Right Time!: A Subjective Cultural History of the American Sixties (Gegensatz Press, 2009), ISBN 0-9655179-2-6, p. 173.

- ^ J. Campbell, This is the Beat Generation: New York, San Francisco, Paris (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001), ISBN 0-520-23033-7.

- ^ R. Worth, Illegal Drugs: Condone Or Incarcerate? (Marshall Cavendish, 2009), ISBN 0-7614-4234-0, p. 30.

- ^ D. Farber, "The Psychologists Psychology:The Intoxicated State/Illegal Nation - Drugs in the Sixties Counterculture", in P. Braunstein and M. W. Doyle (eds), Imagine Nation: The Counterculture of the 1960s and '70s (New York: Routledge, 2002), ISBN 0-415-93040-5, p. 21.

- ^ Anne Applebaum, "Did The Death Of Communism Take Koestler And Other Literary Figures With It?", The Huffington Post, 26 January 2010.

- ^ "Out-Of-Sight! SMiLE Timeline". Archived from the original on 1 February 2010. Retrieved 30 October 2011.

- ^ L. R. Veysey, The Communal Experience: Anarchist and Mystical Communities in Twentieth-Century America (Chicago IL, University of Chicago Press, 1978), ISBN 0-226-85458-2, p. 437.

- ^ R. Unterberger, Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock's Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock (London: Backbeat Books, 2003), ISBN 0-87930-743-9, pp. 11–13.

- ^ a b Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 41 - The Acid Test: Psychedelics and a sub-culture emerge in San Francisco. [Part 1] : UNT Digital Library" (audio). Pop Chronicles. Digital.library.unt.edu. Retrieved 6 May 2011.

- ^ a b M. Hicks, Sixties Rock: Garage, Psychedelic, and Other Satisfactions Music in American Life (Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2000), ISBN 0-252-06915-3, p. 60.

- ^ a b J. Mann, Turn on and Tune in: Psychedelics, Narcotics and Euphoriants (Royal Society of Chemistry, 2009), ISBN 1-84755-909-3, p. 87.

- ^ T. Albright, Art in the San Francisco Bay area, 1945-1980: an Illustrated History (University of California Press, 1985), ISBN 0-520-05193-9, p. 166.

- ^ J. Shepherd, Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World: Media, Industry and Society (New York, NY: Continuum, 2003), ISBN 0-8264-6321-5, p. 211.

- ^ a b DeRogatis 2003, p. 7.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Partridge & Bernhardt 2016.

- ^ a b Longman, Molly (20 May 2016). "Had LSD Never Been Discovered Over 75 Years Ago, Music History Would Be Entirely Different". Music.mic.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 65.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Reising & LeBlanc 2009, p. 95.

- ^ a b Everett 1999, p. 45.

- ^ Ruskin, Zach (19 May 2016). "You Still Believe in Me: An Interview with Brian Wilson".

- ^ R. Unterberger, Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock's Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock (London: Backbeat Books, 2003), ISBN 0-87930-743-9, p. 1.

- ^ R. Unterberger. "Folk Rock: An Overview". Richieunterberger.com. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ C. Grunenberg and J. Harris, Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and Counterculture in the 1960s (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-85323-919-3, p. 137.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, p. 128.

- ^ a b Bellman 1998, p. 292.

- ^ a b Lavezzoli 2006, p. 173.

- ^ N. Talevski, Knocking on Heaven's Door: Rock Obituaries (Omnibus Press, 2006), ISBN 1-84609-091-1, p. 218.

- ^ Hanley 2015, p. 37.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 9.

- ^ R. Unterberger, Eight Miles High: Folk-Rock's Flight from Haight-Ashbury to Woodstock (London: Backbeat Books, 2003), ISBN 0-87930-743-9, p. 4.

- ^ a b Maddux, Rachael (16 May 2011). "Six Degrees of The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds". Wondering Sound.

- ^ Boyd, Brian (4 June 2016). "The Beatles, Bob Dylan and The Beach Boys: 12 months that changed music". The Irish Times.

- ^ R. Unterberger, "British Psychedelic", Allmusic. Retrieved 7 June 2011.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, pp. 35–40.

- ^ McPadden, Mike (13 May 2016). "The Beach Boys' Pet Sounds and 50 Years of Acid-Pop Copycats". The Kind.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 14.

- ^ a b Anon. "Psychedelic Pop". AllMusic.

- ^ Morrison 2000, p. 183.

- ^ Shephard & Leonard 2013, p. 182.

- ^ a b DeRogatis 2003, pp. 33–39.

- ^ T. Holmes, Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture (London: Taylor & Francis, 3rd edn., 2008), ISBN 0-415-95781-8.

- ^ a b Kitts & Tolinski 2002, p. 6.

- ^ Brend 2005, p. 88.

- ^ British Psychedelia at AllMusic

- ^ Pirate Radio, Ministry of Rock.co.uk. Retrieved 9 February 2010.

- ^ P. Gorman, The Look: Adventures in Pop & Rock Fashion (Sanctuary, 2001), ISBN 1-86074-302-1.

- ^ P. Frame, Rock Family Trees (London: Omnibus Press, 1980), ISBN 0-86001-414-2, p. 9.

- ^ MacDonald 1998, p. 216.

- ^ C. Grunenberg and J. Harris, Summer of Love: Psychedelic Art, Social Crisis and Counterculture in the 1960s (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-85323-919-3, pp. 83–4.

- ^ R. Unterberger, "Nick Drake: biography", Allmusic. Retrieved 7 May 2011.

- ^ B. Sweers, Electric Folk: The Changing Face of English Traditional Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005), ISBN 0-19-515878-4, p. 86.

- ^ G. Falk and U. A. Falk, Youth Culture and the Generation Gap (New York, NY: Algora, 2005), ISBN 0-87586-368-X, p. 186.

- ^ W. E. Studwell and D. F. Lonergan, The Classic Rock and Roll Reader: Rock Music from its Beginnings to the mid-1970s (London: Routledge, 1999), ISBN 0-7890-0151-9, p. 223.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. pp. 29, 1027, 1220.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 120.

- ^ a b Macan 1997, p. 19.

- ^ a b Macan 1997, p. 20.

- ^ Macan 1997, p. 21.

- ^ S. Borthwick and R. Moy, Popular Music Genres: an Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2004), ISBN 0-7486-1745-0, p. 44.

- ^ R. Unterberger, Unknown Legends of Rock 'n' Roll: Psychedelic Unknowns, Mad Geniuses, Punk Pioneers, Lo-fi Mavericks & More (Miller Freeman, 1998), ISBN 0-87930-534-7, p. 411.

- ^ P. Houe and S. H. Rossel, Images of America in Scandinavia (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1998), ISBN 90-420-0611-0, p. 77.

- ^ P. Buckley, The Rough Guide to Rock, (Rough Guides , 1999), ISBN 1-85828-457-0, p.26

- ^ P. Stump, Digital Gothic: a Critical Discography of Tangerine Dream (Wembley, Middlesex: SAF, 1997), ISBN 0-946719-18-7, p. 33.

- ^ M. Wood, "Dengue Fever: Multiclti Angelanos craft border-bluring grooves" Spin, January 2008, p. 46.

- ^ R. Unterberger, "Various Artists: Cambodian Rocks Vol. 1: review", Allmusic retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ "KOREAN PSYCH & ACID FOLK, part 1". Progressive.homestead.com. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ V. Karaege, Erkin Koray Allmusic. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ A. Bennett, Remembering Woodstock (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2004), ISBN 0-7546-0714-3.

- ^ I. Inglis, The Beatles, Popular Music and Society: a Thousand Voices (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2000), ISBN 0-312-22236-X, p. 46.

- ^ D. A. Nielsen, Horrible Workers: Max Stirner, Arthur Rimbaud, Robert Johnson, and the Charles Manson Circle: Studies in Moral Experience and Cultural Expression (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2005), ISBN 0-7391-1200-7, p. 84.

- ^ J. Wiener, Come Together: John Lennon in his Time (Chicago IL: University of Illinois Press, 1991), ISBN 0-252-06131-4, pp. 124–6.

- ^ "Garage rock", Billboard, 29 July 2006, 118 (30), p. 11.

- ^ D. Gomery, Media in America: the Wilson Quarterly Reader (Washington DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 2nd edn., 1998), ISBN 0-943875-87-0, pp. 181–2.

- ^ S. Whiteley, Too Much Too Young: Popular Music, Age and Gender (London: Routledge, 2005), ISBN 0-415-31029-6, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d "Psychedelic soul", Allmusic. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ^ G. Case, Out of Our Heads: Rock 'n' Roll Before the Drugs Wore Off (Milwaukie, MI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2010), ISBN 0-87930-967-9, pp. 70–1.

- ^ J. S. Harrington, Sonic Cool: the Life & Death of Rock 'n' Roll (Milwaukie, MI: Hal Leonard Corporation, 2002), ISBN 0-634-02861-8, pp. 249–50.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 226.

- ^ A. Bennett, Rock and Popular Music: Politics, Policies, Institutions (Abingdon: Routledge, 1993), ISBN 0-203-99196-6, p. 239.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 169.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, p. 515.

- ^ A. Blake, The Land Without Music: Music, Culture and Society in Twentieth-Century Britain (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1997), ISBN 0-7190-4299-2, pp. 154–5.

- ^ P. Bussy, Kraftwerk: Man, Machine and Music (London: SAF, 3rd end., 2004), ISBN 0-946719-70-5, pp. 15–17.

- ^ Bogdanov, Woodstra & Erlewine 2002, pp. 1330–1331.

- ^ a b B. A. Cook, Europe Since 1945: an Encyclopedia, Volume 2 (London: Taylor & Francis, 2001), ISBN 0-8153-1336-5, p. 1324.

- ^ DeRogatis 2003, p. 212.

- ^ P. Auslander, Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2006), ISBN 0-472-06868-7, p. 196.

- ^ P. Auslander, "Watch that man David Bowie: Hammersmith Odeon, London, July 3, 1973" in I. Inglis, ed., Performance and Popular Music: History, Place and Time (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2006), ISBN 0-7546-4057-4, p. 72.

Bibliography

- Bellman, Jonathan (1998). The Exotic in Western Music. Northeastern University Press. ISBN 1-55553-319-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas, eds. (2002). All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-653-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help); Unknown parameter|editorlink1=ignored (|editor-link1=suggested) (help); Unknown parameter|editorlink3=ignored (|editor-link3=suggested) (help) - Brend, Mark (2005). Strange Sounds: Offbeat Instruments and Sonic Experiments in Pop. Hal Leonard Corporation.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Browne, Ray Broadus; Browne, Pat (2001). The Guide to United States Popular Culture. Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-821-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carlin, Peter Ames (2006). Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-320-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - DeRogatis, Jim (2003). Turn on Your Mind: Four Decades of Great Psychedelic Rock. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-634-05548-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Everett, Walter (1999). The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York, Ny: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-512941-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Hanley, Jason (2015). We Rock! (Music Lab): A Fun Family Guide for Exploring Rock Music History: From Elvis and the Beatles to Ray Charles and The Ramones, Includes Bios, Historical Context, Extensive Playlists, and Rocking Activities for the Whole Family!. Quarry Books. ISBN 978-1-59253-921-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Macan, Edward (1997). Rocking the Classics: English Progressive Rock and the Counterculture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509887-7.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - MacDonald, Ian (1998). Revolution in the Head: The Beatles' Records and the Sixties. London: Pimlico. ISBN 978-0-7126-6697-8.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Partridge, Andy; Bernhardt, Todd (2016). Complicated Game: Inside the Songs of XTC. Jawbone Press. ISBN 978-1908279781.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Prown, Pete; Newquist, Harvey P. (1997). Legends of Rock Guitar: The Essential Reference of Rock's Greatest Guitarists. Hal Leonard Corporation. ISBN 978-0-7935-4042-6.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Reising, Russell; LeBlanc, Jim (2009). "Magical Mystery Tours, and Other Trips: Yellow submarines, newspaper taxis, and the Beatles' psychedelic years". In Womack, Kenneth (ed.) (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Beatles. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68976-2.

{{cite book}}:|editor-first=has generic name (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Shephard, Tim; Leonard, Anne, eds. (2013). The Routledge Companion to Music and Visual Culture. New York, NY: Routledge. ISBN 9781135956462.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)