The Star-Spangled Banner

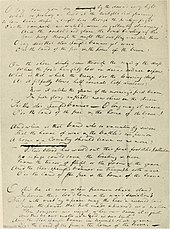

One of two surviving copies of the 1814 broadside printing of the "Defence of Fort McHenry", a poem that later became the lyrics of the national anthem of the United States. | |

National anthem of the | |

| Lyrics | Francis Scott Key, 1814 |

|---|---|

| Music | John Stafford Smith, c. 1773 |

| Adopted | March 4, 1931[1] |

| Audio sample | |

"The Star-Spangled Banner" instrumental | |

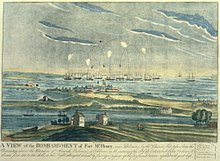

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is the national anthem of the United States of America. The lyrics come from "Defence of Fort M'Henry",[2] a poem written on September 14, 1814, by the 35-year-old lawyer and amateur poet Francis Scott Key after witnessing the bombardment of Fort McHenry by British ships of the Royal Navy in Baltimore Harbor during the Battle of Baltimore in the War of 1812. Key was inspired by the large American flag, the Star-Spangled Banner, flying triumphantly above the fort during the American victory.

The poem was set to the tune of a popular British song written by John Stafford Smith for the Anacreontic Society, a men's social club in London. "To Anacreon in Heaven" (or "The Anacreontic Song"), with various lyrics, was already popular in the United States. Set to Key's poem and renamed "The Star-Spangled Banner", it soon became a well-known American patriotic song. With a range of one octave and one fifth (a semitone more than an octave and a half), it is known for being difficult to sing. Although the poem has four stanzas, only the first is commonly sung today.

"The Star-Spangled Banner" was recognized for official use by the United States Navy in 1889, and by U.S. President Woodrow Wilson in 1916, and was made the national anthem by a congressional resolution on March 3, 1931 (46 Stat. 1508, codified at 36 U.S.C. § 301), which was signed by President Herbert Hoover.

Before 1931, other songs served as the hymns of American officialdom. "Hail, Columbia" served this purpose at official functions for most of the 19th century. "My Country, 'Tis of Thee", whose melody is identical to "God Save the Queen", the British national anthem,[3] also served as a de facto anthem.[4] Following the War of 1812 and subsequent American wars, other songs emerged to compete for popularity at public events, among them "The Star-Spangled Banner", as well as "America the Beautiful".

Early history

Francis Scott Key's lyrics

On September 3, 1814, following the Burning of Washington and the Raid on Alexandria, Francis Scott Key and John Stuart Skinner set sail from Baltimore aboard the ship HMS Minden, flying a flag of truce on a mission approved by President James Madison. Their objective was to secure the exchange of prisoners, one of whom was Dr. William Beanes, the elderly and popular town physician of Upper Marlboro and a friend of Key's who had been captured in his home. Beanes was accused of aiding the arrest of British soldiers. Key and Skinner boarded the British flagship HMS Tonnant on September 7 and spoke with Major General Robert Ross and Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane over dinner while the two officers discussed war plans. At first, Ross and Cochrane refused to release Beanes, but relented after Key and Skinner showed them letters written by wounded British prisoners praising Beanes and other Americans for their kind treatment.

Because Key and Skinner had heard details of the plans for the attack on Baltimore, they were held captive until after the battle, first aboard HMS Surprise and later back on HMS Minden. After the bombardment, certain British gunboats attempted to slip past the fort and effect a landing in a cove to the west of it, but they were turned away by fire from nearby Fort Covington, the city's last line of defense.

During the rainy night, Key had witnessed the bombardment and observed that the fort's smaller "storm flag" continued to fly, but once the shell and Congreve rocket[5] barrage had stopped, he would not know how the battle had turned out until dawn. On the morning of September 14, the storm flag had been lowered and the larger flag had been raised.

During the bombardment, HMS Erebus provided the "rockets' red glare". HMS Meteor provided at least some of the "bombs bursting in air".

Key was inspired by the American victory and the sight of the large American flag flying triumphantly above the fort. This flag, with fifteen stars and fifteen stripes, had been made by Mary Young Pickersgill together with other workers in her home on Baltimore's Pratt Street. The flag later came to be known as the Star-Spangled Banner and is today on display in the National Museum of American History, a treasure of the Smithsonian Institution. It was restored in 1914 by Amelia Fowler, and again in 1998 as part of an ongoing conservation program.

Aboard the ship the next day, Key wrote a poem on the back of a letter he had kept in his pocket. At twilight on September 16, he and Skinner were released in Baltimore. He completed the poem at the Indian Queen Hotel, where he was staying, and titled it "Defence of Fort M'Henry".

Much of the idea of the poem, including the flag imagery and some of the wording, is derived from an earlier song by Key, also set to the tune of "The Anacreontic Song". The song, known as "When the Warrior Returns",[6] was written in honor of Stephen Decatur and Charles Stewart on their return from the First Barbary War.

Absent elaboration by Francis Scott Key prior to his death in 1843, some have speculated in modern times about the meaning of phrases or verses. According to British historian Robin Blackburn, the words "the hireling and slave" allude to any ex-slaves in the British ranks, who had been promised liberty and demanded to be placed in the battle line "where they might expect to meet their former masters"[7] (even though Britain itself practiced slavery until 1833 when it was abolished in most of the Empire) -- a tactic later used by President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation which applied only to slaves in rebelling states but not Union ones. Professor Mark Clague has stated that the "middle two verses of Key's lyric vilify the British enemy in the War of 1812" and "in no way glorifies or celebrates slavery."[8] Clague notes that the language used to refer to "British professional soldiers (hirelings) but also the Corps of Colonial Marines (slaves)" which Key viewed as "scoundrels and ... traitors who threatened to spark a national insurrection," led to the omission of the third verse during World War I when Britain was an ally. Others[9] contend it speaks to checkered allegiances[10] with "hireling" referring to mercenaries motivated by money [11] not country and enlisted Americans "who so vauntingly swore" loyalty only to turn "slave" by the long-standing British practice of impressment,[12] which rejoins the song's preceding line of "Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps pollution" of invaders under the Britsh flag.[13]

After the U.S. and the British signed a peace treaty at the end of 1814, the U.S. government demanded the return of American “property,” which by that point numbered about 6,000 people. The British refused. Most of the 6,000 eventually settled in Canada, with some going to Trinidad.[14]

John Stafford Smith's music

Key gave the poem to his brother-in-law Judge Joseph H. Nicholson who saw that the words fit the popular melody "The Anacreontic Song", by English composer John Stafford Smith. This was the official song of the Anacreontic Society, an 18th-century gentlemen's club of amateur musicians in London. Nicholson took the poem to a printer in Baltimore, who anonymously made the first known broadside printing on September 17; of these, two known copies survive.

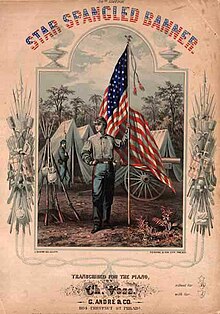

On September 20, both the Baltimore Patriot and The American printed the song, with the note "Tune: Anacreon in Heaven". The song quickly became popular, with seventeen newspapers from Georgia to New Hampshire printing it. Soon after, Thomas Carr of the Carr Music Store in Baltimore published the words and music together under the title "The Star Spangled Banner", although it was originally called "Defence of Fort M'Henry". The song's popularity increased, and its first public performance took place in October, when Baltimore actor Ferdinand Durang sang it at Captain McCauley's tavern. Washington Irving, then editor of The Analectic Magazine in Philadelphia, reprinted the song in November 1814.

By the early 20th century, there were various versions of the song in popular use. Seeking a singular, standard version, President Woodrow Wilson tasked the U.S. Bureau of Education with providing that official version. In response, the Bureau enlisted the help of five musicians to agree upon an arrangement. Those musicians were Walter Damrosch, Will Earhart, Arnold J. Gantvoort, Oscar Sonneck and John Philip Sousa. The standardized version that was voted upon by these five musicians premiered at Carnegie Hall on December 5, 1917, in a program that included Edward Elgar's Carillon and Gabriel Pierné's The Children's Crusade. The concert was put on by the Oratorio Society of New York and conducted by Walter Damrosch.[15] An official handwritten version of the final votes of these five men has been found and shows all five men's votes tallied, measure by measure.[16]

The Italian opera composer Giacomo Puccini used an extract of the melody in writing the aria "Dovunque al mondo..." in 1904 for his work Madama Butterfly.

National anthem

The song gained popularity throughout the 19th century and bands played it during public events, such as July 4th celebrations. On July 27, 1889, Secretary of the Navy Benjamin F. Tracy signed General Order #374, making "The Star-Spangled Banner" the official tune to be played at the raising of the flag.

In 1916, President Woodrow Wilson ordered that "The Star-Spangled Banner" be played at military and other appropriate occasions. The playing of the song two years later during the seventh-inning stretch of Game One of the 1918 World Series, and thereafter during each game of the series is often cited as the first instance that the anthem was played at a baseball game,[17] though evidence shows that the "Star-Spangled Banner" was performed as early as 1897 at opening day ceremonies in Philadelphia and then more regularly at the Polo Grounds in New York City beginning in 1898. In any case, the tradition of performing the national anthem before every baseball game began in World War II.[18]

On April 10, 1918, John Charles Linthicum, U.S. Congressman from Maryland, introduced a bill to officially recognize "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the national anthem.[19] The bill did not pass.[19]

On April 15, 1929, Linthicum introduced the bill again, his sixth time doing so.[19]

On November 3, 1929, Robert Ripley drew a panel in his syndicated cartoon, Ripley's Believe it or Not!, saying "Believe It or Not, America has no national anthem".[20]

In 1930, Veterans of Foreign Wars started a petition for the United States to officially recognize "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the national anthem.[21] Five million people signed the petition.[21] The petition was presented to the United States House Committee on the Judiciary on January 31, 1930.[22] On the same day, Elsie Jorss-Reilley and Grace Evelyn Boudlin sang the song to the Committee to refute the perception that it was too high pitched for a typical person to sing.[23] The Committee voted in favor of sending the bill to the House floor for a vote.[24] The House of Representatives passed the bill later that year.[25]

The Senate passed the bill on March 3, 1931.[25]

President Herbert Hoover signed the bill on March 4, 1931, officially adopting "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the national anthem of the United States of America.[1]

Lyrics

O say can you see, by the dawn's early light,

What so proudly we hailed at the twilight's last gleaming,

Whose broad stripes and bright stars through the perilous fight,

O'er the ramparts we watched, were so gallantly streaming?

And the rockets' red glare, the bombs bursting in air,

Gave proof through the night that our flag was still there;

O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

On the shore dimly seen through the mists of the deep,

Where the foe's haughty host in dread silence reposes,

What is that which the breeze, o'er the towering steep,

As it fitfully blows, half conceals, half discloses?

Now it catches the gleam of the morning's first beam,

In full glory reflected now shines in the stream:

'Tis the star-spangled banner, O long may it wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

And where is that band who so vauntingly swore

That the havoc of war and the battle's confusion,

A home and a country, should leave us no more?

Their blood has washed out their foul footsteps' pollution.

No refuge could save the hireling and slave

From the terror of flight, or the gloom of the grave:

And the star-spangled banner in triumph doth wave,

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave.

O thus be it ever, when freemen shall stand

Between their loved homes and the war's desolation.

Blest with vict'ry and peace, may the Heav'n rescued land

Praise the Power that hath made and preserved us a nation!

Then conquer we must, when our cause it is just,

And this be our motto: 'In God is our trust.'

And the star-spangled banner in triumph shall wave

O'er the land of the free and the home of the brave![26]

Additional Civil War period lyrics

In indignation over the start of the American Civil War, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.[27] added a fifth stanza to the song in 1861, which appeared in songbooks of the era.[28]

When our land is illumined with Liberty's smile,

If a foe from within strike a blow at her glory,

Down, down with the traitor that dares to defile

The flag of her stars and the page of her story!

By the millions unchained who our birthright have gained,

We will keep her bright blazon forever unstained!

And the Star-Spangled Banner in triumph shall wave

While the land of the free is the home of the brave.

Alternative lyrics

In a version hand-written by Francis Scott Key in 1840, the third line reads "Whose bright stars and broad stripes, through the clouds of the fight".[29]

Modern history

Performances

The song is notoriously difficult for nonprofessionals to sing because of its wide range – a 12th. Humorist Richard Armour referred to the song's difficulty in his book It All Started With Columbus.

In an attempt to take Baltimore, the British attacked Fort McHenry, which protected the harbor. Bombs were soon bursting in air, rockets were glaring, and all in all it was a moment of great historical interest. During the bombardment, a young lawyer named Francis Off Key [sic] wrote "The Star-Spangled Banner", and when, by the dawn's early light, the British heard it sung, they fled in terror.

— Richard Armour

Professional and amateur singers have been known to forget the words, which is one reason the song is sometimes pre-recorded and lip-synced.[citation needed] Other times the issue is avoided by having the performer(s) play the anthem instrumentally instead of singing it. The pre-recording of the anthem has become standard practice at some ballparks, such as Boston's Fenway Park, according to the SABR publication The Fenway Project.[30]

"The Star-Spangled Banner" is traditionally played at the beginning of public sports events and orchestral concerts in the United States, as well as other public gatherings. The National Hockey League and Major League Soccer both require venues in both the U.S. and Canada to perform both the Canadian and American national anthems at games that involve teams from both countries (with the "away" anthem being performed first).[31][better source needed] It is also usual for both American and Canadian anthems (done in the same way as the NHL and MLS) to be played at Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association games involving the Toronto Blue Jays and the Toronto Raptors (respectively), the only Canadian teams in those two major U.S. sports leagues. The Buffalo Sabres of the NHL, which play in a city on the Canada–US border and have a substantial Canadian fan base, play both anthems before all home games regardless of where the visiting team is based.[32]

Two especially unusual performances of the song took place in the immediate aftermath of the United States September 11 attacks. On September 12, 2001, the Queen broke with tradition and allowed the Band of the Coldstream Guards to perform the anthem at Buckingham Palace, London, at the ceremonial Changing of the Guard, as a gesture of support for Britain's ally.[33] The following day at a St. Paul's Cathedral memorial service, the Queen joined in the singing of the anthem, an unprecedented occurrence.[34]

200th anniversary celebrations

The 200th anniversary of the "Star-Spangled Banner" occurred in 2014 with various special events occurring throughout the United States. A particularly significant celebration occurred during the week of September 10–16 in and around Baltimore, Maryland. Highlights included playing of a new arrangement of the anthem arranged by John Williams and participation of President Obama on Defender's Day, September 12, 2014, at Fort McHenry.[35] In addition, the anthem bicentennial included a youth music celebration[36] including the presentation of the National Anthem Bicentennial Youth Challenge winning composition written by Noah Altshuler.

Adaptations

The first popular music performance of the anthem heard by mainstream America was by Puerto Rican singer and guitarist José Feliciano. He created a nationwide uproar when he strummed a slow, blues-style rendition of the song[37] at Tiger Stadium in Detroit before game five of the 1968 World Series, between Detroit and St. Louis.[38] This rendition started contemporary "Star-Spangled Banner" controversies. The response from many in Vietnam-era America was generally negative. Despite the controversy, Feliciano's performance opened the door for the countless interpretations of the "Star-Spangled Banner" heard in the years since.[39] One week after Feliciano's performance, the anthem was in the news again when American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos lifted controversial raised fists at the 1968 Olympics while the "Star-Spangled Banner" played at a medal ceremony.

Marvin Gaye gave a soul-influenced performance at the 1983 NBA All-Star Game and Whitney Houston gave a soulful rendition before Super Bowl XXV in 1991, which was released as a single that charted at number 20 in 1991 and number 6 in 2001 (along with José Feliciano, the only times the anthem has been on the Billboard Hot 100). In 1993, Kiss did an instrumental rock version as the closing track on their album, Alive III. Another famous instrumental interpretation is Jimi Hendrix's version, which was a set-list staple from autumn 1968 until his death in September 1970, including a famous rendition at the Woodstock music festival in 1969. Incorporating sonic effects to emphasize the "rockets' red glare", and "bombs bursting in air", it became a late-1960s emblem. Roseanne Barr gave a controversial performance of the anthem at a San Diego Padres baseball game at Jack Murphy Stadium on July 25, 1990. The comedian belted out a screechy rendition of the song, and afterward she attempted a gesture of ball players by spitting and grabbing her crotch as if adjusting a protective cup. The performance offended some, including the sitting U.S. President, George H. W. Bush.[40] Sufjan Stevens has frequently performed the "Star-Spangled Banner" in live sets, replacing the optimism in the end of the first verse with a new coda that alludes to the divisive state of the nation today. David Lee Roth both referenced parts of the anthem and played part of a hard rock rendition of the anthem on his song, "Yankee Rose" on his 1986 solo album, Eat 'Em and Smile. Steven Tyler also caused some controversy in 2001 (at the Indianapolis 500, to which he later issued a public apology) and again in 2012 (at the AFC Championship Game) with a cappella renditions of the song with changed lyrics.[41] A version of Aerosmith's Joe Perry and Brad Whitford playing part of the song can be heard at the end of their version of "Train Kept A-Rollin'" on the Rockin' the Joint album. The band Boston gave an instrumental rock rendition of the anthem on their Greatest Hits album. The band Crush 40 made a version of the song as opening track from the album Thrill of the Feel (2000).

In March 2005, a government-sponsored program, the National Anthem Project, was launched after a Harris Interactive poll showed many adults knew neither the lyrics nor the history of the anthem.[42]

References in film, television, literature

Several films have their titles taken from the song's lyrics. These include two films titled Dawn's Early Light (2000[43] and 2005);[44] two made-for-TV features titled By Dawn's Early Light (1990[45] and 2000);[46] two films titled So Proudly We Hail (1943[47] and 1990);[48] a feature (1977)[49] and a short (2005)[50] titled Twilight's Last Gleaming; and four films titled Home of the Brave (1949,[51] 1986,[52] 2004,[53] and 2006).[54]

Customs

United States Code, 36 U.S.C. § 301, states that during a rendition of the national anthem, when the flag is displayed, all present except those in uniform should stand at attention facing the flag with the right hand over the heart; Members of the Armed Forces and veterans who are present and not in uniform may render the military salute; men not in uniform should remove their headdress with their right hand and hold the headdress at the left shoulder, the hand being over the heart; and individuals in uniform should give the military salute at the first note of the anthem and maintain that position until the last note; and when the flag is not displayed, all present should face toward the music and act in the same manner they would if the flag were displayed. Military law requires all vehicles on the installation to stop when the song is played and all individuals outside to stand at attention and face the direction of the music and either salute, in uniform, or place the right hand over the heart, if out of uniform. A law passed in 2008 allows military veterans to salute out of uniform, as well.[55][56]

However, this statutory suggestion does not have any penalty associated with violations. 36 U.S.C. § 301 This behavioral requirement for the national anthem is subject to the same First Amendment controversies that surround the Pledge of Allegiance.[57] For example, Jehovah's Witnesses do not sing the national anthem, though they are taught that standing is an "ethical decision" that individual believers must make based on their "conscience."[58][59][60]

Protests

1968 Olympics Black Power Salute

The 1968 Olympics Black Power salute was a political demonstration conducted by African-American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics in the Olympic Stadium in Mexico City. After having won gold and bronze medals respectively in the 200 meter running event, they turned on the podium to face their flags, and to hear the American national anthem, "The Star-Spangled Banner". Each athlete raised a black-gloved fist, and kept them raised until the anthem had finished. In addition, Smith, Carlos, and Australian silver medalist Peter Norman all wore human rights badges on their jackets. In his autobiography, Silent Gesture, Smith stated that the gesture was not a "Black Power" salute, but a "human rights salute". The event is regarded as one of the most overtly political statements in the history of the modern Olympic Games.[61]

2016 protests

Before a preseason NFL game in 2016, Colin Kaepernick sat down, as opposed to the tradition of standing, during the playing of the anthem. During a post-game interview he explained his position stating, "I am not going to stand up to show pride in a flag for a country that oppresses black people and people of color. To me, this is bigger than football and it would be selfish on my part to look the other way. There are bodies in the street and people getting paid leave and getting away with murder", referencing a series of events that led to the Black Lives Matter movement and adding that he would continue to protest until he feels like "[the American flag] represents what it’s supposed to represent”.[62]

In the 49ers' final 2016 preseason game on September 1, 2016, Kaepernick opted to kneel during the U.S. national anthem rather than sit as he did in their previous games. He explained his decision to switch was an attempt to show more respect to former and current U.S. military members while still protesting the anthem after having a conversation with former NFL prospect and U.S. military veteran Nate Boyer.[63] Fellow 49ers player Eric Reid joined Kaepernick in kneeling during the national anthem during the final preseason game.[64] Seattle Seahawks player Jeremy Lane also did not stand for the anthem during his final preseason game the same day, stating "It's something I plan to keep on doing until justice is being served."[65]

Seattle Reign and U.S. women's national soccer team player Megan Rapinoe kneeled during the national anthem in a game on September 5, explaining that her decision was a "nod to Kaepernick and everything that he's standing for right now".[66]

In week one, on September 11, Kansas City Chiefs player Marcus Peters raised his fist while the rest of the team interlocked their arms showing solidarity.[67] The entire Seattle Seahawks team stood and interlocked arms.[68]

In week two, Kaepernick again knelt for the national anthem. San Francisco 49ers players Antoine Bethea, Jaquiski Tartt, Eli Harold, Rashard Robinson raised their right fists during the national anthem.[69] Robert Quinn (American football) also raised his right fist in Los Angeles, recalling the 1968 protest.[69] Miami Dolphins players Arian Foster, Kenny Stills and Michael Thomas knelt before their game against the Patriots. Tennessee Titans cornerback Jason McCourty and defensive tackle Jurrell Casey raised their right fists.[69] Philadelphia Eagles players Malcolm Jenkins, Ron Brooks and Steven Means stood together and raised their fists in the air.[70]

Musical artists J. Cole and Trey Songz were seen performing concerts wearing Kaepernick jerseys.[71] A number of U.S. military veterans voiced support using the social media hashtag "veterans for Kaepernick".[72] In the following weeks, Kaepernick's jersey became the top-selling jersey on the NFL's official shop website.[73]

Kaepernick also received public backlash for his protest. A few NFL fans posted videos of them burning Kaepernick jerseys. Former NFL MVP Boomer Esiason called Kaepernick's actions "an embarrassment" while an anonymous NFL executive called Kaepernick "a traitor".[74]

Translations

As a result of immigration to the United States and the incorporation of non-English speaking people into the country, the lyrics of the song have been translated into other languages. In 1861, it was translated into German.[75] The Library of Congress also has record of a Spanish-language version from 1919.[76] It has since been translated into Hebrew[77] and Yiddish by Jewish immigrants,[78] Latin American Spanish (with one version popularized during immigration reform protests in 2006),[79] French by Acadians of Louisiana,[80] Samoan,[81] and Irish.[82] The third verse of the anthem has also been translated into Latin.[83]

With regard to the indigenous languages of North America, there are versions in Navajo[84][85][86] and Cherokee.[87]

Media

See also

References

- ^ a b ""Star-Spangled Banner" Is Now Official Anthem". The Washington Post. March 5, 1931. p. 3.

- ^ "Library of Congress: Defence of Fort M'Henry".

- ^ "My country 'tis of thee [Song Collection]". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2009-01-20.

- ^ Snyder, Lois Leo (1990). Encyclopedia of Nationalism. Paragon House. p. 13. ISBN 1-55778-167-2.

- ^ British Rockets at the US National Park Service, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine. Retrieved February 2008. Archived 2014-04-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "When the Warrior Returns".

- ^ Blackburn, Robin (1988). The Overthrdow of Colonial Slavery, 1776–1848. pp. 288–290.

- ^ http://www.cnn.com/2016/08/31/opinions/star-spangled-banner-criticisms-opinion-clague/

- ^ http://www.snopes.com/2016/08/29/star-spangled-banner-and-slavery/

- ^ http://dailycaller.com/2016/08/29/progressives-put-the-star-spangled-banner-on-their-chopping-block/

- ^ https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/hireling

- ^ http://ijr.com/2016/08/684228-national-anthem-verse-celebrating-slavery-being-used-to-justify-kaepernick-is-really-bad-defense/

- ^ http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/03/arts/music/colin-kaepernick-national-anthem.html

- ^ "The National Anthem Is a Celebration of Slavery".

- ^ The Star Spangled Banner: Part of the History of The Oratorio Society of New York [1] by the Oratorio Society of New York

- ^ Standardization Manuscript for The Star Spangled Banner [2] on Antiques Roadshow (U.S.).

- ^ "Cubs vs Red Sox 1918 World Series: A Tradition is Born".

- ^ "Musical traditions in sports". CNN.

- ^ a b c "National Anthem Hearing Is Set For January 31". The Baltimore Sun. January 23, 1930. p. 4.

- ^ Ripley's Newsroom [3].

- ^ a b "5,000,000 Sign for Anthem: Fifty-Mile Petition Supports "The Star-Spangled Banner" Bill". The New York Times. January 19, 1930. p. 31.

- ^ "5,000,000 Plea For U.S. Anthem: Giant Petition to Be Given Judiciary Committee of Senate Today". The Washington Post. January 31, 1930. p. 2.

- ^ "Committee Hears Star-Spangled Banner Sung: Studies Bill to Make It the National Anthem". The New York Times. February 1, 1930. p. 1.

- ^ "'Star-Spangled Banner' Favored As Anthem in Report to House". The New York Times. February 5, 1930. p. 3.

- ^ a b "'Star Spangled Banner' Is Voted National Anthem by Congress". The New York Times. March 4, 1931. p. 1.

- ^ Francis Scott Key, The Star Spangled Banner (lyrics), 1814, MENC: The National Association for Music Education National Anthem Project (archived from the original Archived 2013-01-26 at the Wayback Machine on 2013-01-26).

- ^ Butterworth, Hezekiah; Brown, Theron (1906). "The Story of the Hymns and Tunes". George H. Doran Co.: 335.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ The soldier's companion: dedicated ... – Google Books. Books.google.com. 1865. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "Library of Congress image". Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "The Fenway Project – Part One". Red Sox Connection. May 2004.

- ^ Allen, Kevin (2003-03-23). "NHL Seeks to Stop Booing For a Song". USA Today. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- ^ "Fanzone, A-Z Guide: National Anthems". Buffalo Sabres. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

If you are interested in singing the National Anthems at a sporting event at First Niagara Center, you must submit a DVD or CD of your performance of both the Canadian & American National Anthems...

- ^ Graves, David (September 14, 2001) "Palace breaks with tradition in musical tribute". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved August 24, 2011

- ^ Steyn, Mark (September 17, 2001). "The Queen's Tears/And global resolve against terrorism". National Review. Archived from the original on 2013-06-15. Retrieved 2013-04-10.

- ^ Michael E. Ruane (September 11, 2014). "Francis Scott Key's anthem keeps asking: Have we survived as a nation?". Washington Post.

- ^ https://www.anthembicentennial.org

- ^ Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 52 – The Soul Reformation: Phase three, soul music at the summit. [Part 8]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Track 5.

- ^ Paul White, USA TODAY Sports (October 14, 2012). "Jose Feliciano's once-controversial anthem kicks off NLCS". Usatoday.com. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ Jose Feliciano Personal account about the anthem performance

- ^ Letofsky, Irv (July 28, 1990). "Roseanne Is Sorry – but Not That Sorry". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 14, 2012.

- ^ "AOL Radio – Listen to Free Online Radio – Free Internet Radio Stations and Music Playlists". Spinner.com. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- ^ "Harris Interactive poll on "The Star-Spangled Banner"". Tnap.org. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ Dawn's Early Light (2000) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Dawn's Early Light (2005) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Dawn's Early Light TV (1990) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Dawn's Early Light TV (2000) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ So Proudly We Hail (1943) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ So Proudly We Hail (1990) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Twilight's Last Gleaming (1977) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Twilight's Last Gleaming (2005) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Home of the Brave (1949) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ Home of the Brave (1986) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ Home of the Brave (2004) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved December 5, 2007.

- ^ Home of the Brave (2006) on the Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Duane Streufert. "A website dedicated to the Flag of the United States of America – United States Code". USFlag.org. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "U.S. Code". Uscode.house.gov. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ The Circle School v. Phillips, 270 F. Supp. 2d 616, 622 (E.D. Pa. 2003).

- ^ "Highlights of the Beliefs of Jehovah's Witnesses". Towerwatch.com. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ Botting, Gary Norman Arthur (1993). Fundamental freedoms and Jehovah's Witnesses. University of Calgary Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-895176-06-3. Retrieved 2009-12-13.

- ^ Chryssides, George D. (2008). Historical Dictionary of Jehovah's Witnesses. Scarecrow Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-8108-6074-2. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ^ Lewis, Richard (8 October 2006). "Caught in Time: Black Power salute, Mexico, 1968". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 9 November 2008.

- ^ Wyche, Steve (August 27, 2016). "Colin Kaepernick explains why he sat during national anthem". NFL.com. Retrieved August 27, 2016.

- ^ "LOOK: Green Beret Nate Boyer meets with Colin Kaepernick for a 'good talk'". September 2, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Press, Associated (September 1, 2016). "Colin Kaepernick joined by Eric Reid in kneeling for national anthem protest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ "Seahawks' Jeremy Lane joins Colin Kaepernick's protest, sits during national anthem". Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ CNN, Euan McKirdy. "Megan Rapinoe takes knee in solidarity with Kaepernick". CNN. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ Gajanan, Mahita. "Kansas City Chiefs Cornerback Marcus Peters Raises Fist During National Anthem". Time. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Arnold, Geoffrey. "Seattle Seahawks lock arms during national anthem". oregonlive.com. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ a b c Lamport-Stokes, Mark. "Week 2 brought more kneeling football players, raised fists, in anthem protests". Reuters. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Armour, Nancy. "Malcolm Jenkins, two Eagles teammates raise fists in protest during anthem". USA Today. Retrieved 20 September 2016.

- ^ Gould, Andrew. "J. Cole and Trey Songz Perform in Kap Jerseys". Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Dator, James (August 31, 2016). "U.S. military members show support for Kaepernick". Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ "Kaepernick Says He'll Donate Proceeds From Top-Selling Jersey". ABC News. September 7, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Freeman, Mike. "Kaepernick Anger Intense in NFL Front Offices". Retrieved September 8, 2016.

- ^ Das Star-Spangled Banner, US Library of Congress. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ La Bandera de las Estrellas, US Library of Congress. Retrieved May 31, 2005.

- ^ Hebrew Version

- ^ Abraham Asen, The Star Spangled Banner in pool, 1745, Joe Fishstein Collection of Yiddish Poetry, McGill University Digital Collections Programme. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Day to Day. "A Spanish Version of 'The Star-Spangled Banner'". NPR. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ David Émile Marcantel, La Bannière Étoilée on Musique Acadienne. Retrieved September 14, 2007.

- ^ Zimmer, Benjamin (2006-04-29). "The ''Samoa News'' reporting of a Samoan version". Itre.cis.upenn.edu. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "''An Bhratach Gheal-Réaltach'' – Irish version". Daltai.com. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ Christopher M. Brunelle, Third Verse in Latin, 1999

- ^ "Gallup Independent, 25 March 2005". Gallupindependent.com. 2005-03-25. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ New Mexico Department of Veterans' Services [dead link]

- ^ "Schedule for the Presidential Inauguration 2007, Navajo Nation Government". Navajo.org. 2007-01-09. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- ^ "Cherokee Phoenix, Accessed 2009-08-15". Cherokeephoenix.org. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

Further reading

- Ferris, Marc. Star-Spangled Banner: the Unlikely Story of America's National Anthem. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014. ISBN 9781421415185 OCLC 879370575

- Leepson, Marc. What So Proudly We Hailed: Francis Scott Key, a Life. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. ISBN 9781137278289 OCLC 860395373

External links

- Star-Spangled Banner (Memory): American Treasures of the Library of Congress

- "How the National Anthem Has Unfurled; 'The Star-Spangled Banner' Has Changed a Lot in 200 Years." By WILLIAM ROBIN JUNE 27, 2014 The New York Times

- C-SPAN American History TV tour of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History Star-Spangled Banner exhibit

Historical audio

- The Star Spangled Banner, The Diamond Four, 1898

- The Star Spangled Banner, Margaret Woodrow Wilson, 1915