1950 United States Senate election in California

| |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

Election results by county | |||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||

The 1950 United States Senate election in California followed a campaign characterized by accusations and name-calling. Republican Richard Nixon defeated Democrat Helen Gahagan Douglas, after Democratic incumbent Sheridan Downey withdrew during the primary election campaign. Douglas and Nixon each gave up their congressional seats to run against Downey; no other representatives were willing to risk the contest.

Both Douglas and Nixon announced their candidacies in late 1949. In March 1950 Downey withdrew from a vicious primary battle with Douglas by announcing his retirement, after which Los Angeles Daily News publisher Manchester Boddy joined the race. Boddy attacked Douglas as a leftist and was the first to compare her to New York Congressman Vito Marcantonio, who was accused of being a communist. Boddy, Nixon, and Douglas each entered both party primaries, a practice known as cross-filing. In the Republican primary, Nixon was challenged only by cross-filers and fringe candidates.

Nixon won the Republican primary and Douglas the Democratic contest, with each also finishing third in the other party's contest (Boddy finished second in both races). The contentious Democratic race left the party divided, and Democrats were slow to rally to Douglas—some even endorsed Nixon. The Korean War broke out only days after the primaries, and both Nixon and Douglas contended that the other had often voted with Marcantonio to the detriment of national security. Nixon's attacks were far more effective, and he won the November 7 general election by almost 20 percentage points, carrying 53 of California's 58 counties and all metropolitan areas.

Though Nixon was later criticized for his tactics in the campaign, he defended his actions, and also stated that Douglas's positions were too far to the left for California voters. Other reasons for the result have been suggested, ranging from tepid support for Douglas from President Truman and his administration to the reluctance of voters in 1950 to elect a woman. The campaign gave rise to two memorable political nicknames, both coined by Boddy or making their first appearance in his newspaper: "the Pink Lady" for Douglas and "Tricky Dick" for Nixon.

Background

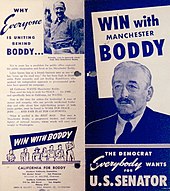

California Senator Sheridan Downey was first elected in 1938. An attorney, he ran unsuccessfully in 1934 for Lieutenant Governor of California as Upton Sinclair's running mate, and had a reputation as a liberal.[1] As a senator, however, his positions gradually moved to the right, and he began to favor corporate interests.[2] Manchester Boddy, the editor and publisher of the Los Angeles Daily News, was born on a potato farm in Washington state. He had little newspaper experience when, in 1926, he was given the opportunity to purchase the Daily News by a bankruptcy court,[3] but built it into a small but thriving periodical.[4] He shared his views with his readers through his column, "Thinking and Living", and, after initial Republican leanings, was a firm supporter of the New Deal.[5] While the Daily News had not endorsed the Sinclair-Downey ticket,[a] Boddy had called Sinclair "a great man" and allowed the writer-turned-gubernatorial candidate to set forth his views on the newspaper's front page.[6]

Both Helen Douglas and Richard Nixon entered electoral politics in the mid-1940s. Douglas, a New Deal Democrat, was a former actress and opera singer, and the wife of actor Melvyn Douglas. She represented the 14th congressional district beginning in 1945.[7] Nixon grew up in a working-class family in Whittier.[8] In 1946, he defeated 12th district Congressman Jerry Voorhis to claim a seat in the United States House of Representatives,[9] where he became known for his anticommunist activities, including his involvement in the Alger Hiss affair.[10]

In the 1940s, California experienced a huge influx of migrants, increasing its population by 55%.[11] Party registration in 1950 was 58.4% Democratic and 37.1% Republican.[12] However, other than Downey, most major California officeholders were Republican, including Governor Earl Warren (who was seeking a third term in 1950) and Senator William Knowland.[1]

During the 1950 campaign, both Nixon and Douglas were accused of having a voting record comparable to that of New York Congressman Vito Marcantonio. The sole congressman from the American Labor Party at the time, Marcantonio represented East Harlem. He was accused of being a communist,[13] though he denied being one; he rarely discussed the Soviet Union or communism. Marcantonio opposed restrictions on communists and the Communist Party, stating that such restrictions violated the Bill of Rights. He regularly voted against contempt citations requested by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), on which Nixon served.[14]

Primary campaign

Democratic contest

Early campaign

Douglas disregarded advice from party officials to wait until 1952 to run for the Senate, when Republican Senator Knowland would be up for reelection.[15] Fundraising for the campaign was a concern from the beginning; Douglas friend and aide Ed Lybeck wrote her that she would probably need to raise $150,000 ($1.8 million today),[16] which Douglas considered a massive sum.[17] Lybeck wrote,

Now, you can win. You will not be a favorite; you'll be rather a long shot. But given luck and money and a hell of a lot of work, you can win ... but for Christ's sake don't commit suicide with no dough ... Maybe you can't crucify mankind on a cross of gold, but you can sure as hell crucify a statewide candidate upon a cross of no-gold.[17]

On October 5, 1949, Douglas made a radio appearance announcing her candidacy.[15] She attacked Downey almost continuously throughout the remainder of the year,[18] accusing him of being a do-nothing, a tool of big business, and an agent of oil interests.[19] She hired Harold Tipton, a newcomer to California who had managed a successful congressional campaign in the Seattle area, as her campaign manager.[20] Douglas realized that Nixon would most likely be the Republican nominee, and felt that were she to win the primary, the wide gap between Nixon's positions and hers would cause voters to rally to her.[18] Downey, who suffered from a severe ulcer, was initially undecided about running, but announced his candidacy in early December in a speech that included an attack on Douglas.[21] Earl Desmond, a member of the California State Senate from Sacramento whose positions were similar to Downey's, also entered the race.[22]

In January 1950, Douglas opened campaign headquarters in Los Angeles and San Francisco, which was seen as a signal that she was serious about contesting Downey's seat and would not withdraw from the race.[12] Downey challenged Douglas to a series of debates; Douglas, who was not a good debater, declined.[22] The two candidates traded charges via press and radio, with Downey describing Douglas's views as extremist.[21]

Douglas's formal campaign launch on February 28 was overshadowed by rumors that Downey might retire, which Douglas called a political maneuver on Downey's part to get the attention of the press.[22] However, on March 29, amid rumors that he was doing badly in the polls, Downey announced both his retirement and his endorsement of Los Angeles Daily News publisher Manchester Boddy.[23] In his statement, the senator indicated that, due to his ill health, he was not up to "waging a personal and militant campaign against the vicious and unethical propaganda" of Douglas.[24]

Boddy filed his election paperwork the next day, on the final day petitions were accepted, with his papers signed by Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron, a Republican, and by Downey campaign manager and 1946 Democratic senatorial candidate Will Rogers, Jr.[25] The publisher had been urged to enter the race by state Democratic leaders and by wealthy oilmen.[26] He had no political experience; Democratic leaders had sought to draft him to run for the Senate in 1946, but he had declined. He later stated that his reasons for running were that the race would be a challenge, and that he would meet interesting people.[27] Boddy, Douglas, and Nixon each "cross-filed", entering both major party primaries.[28]

Douglas called Downey's departure in favor of the publisher a cheap gimmick[24] and made no attempt to reach a rapprochement with the senator,[29] who entered Bethesda Naval Hospital for treatment in early April, and was on sick leave from Congress for several months.[30] The change in opponents was a mixed blessing for Douglas; it removed the incumbent from the field, but deprived her of the endorsement of the Daily News—one of the few big city papers to consistently support her.[31]

Boddy versus Douglas

For the first month of Boddy's abbreviated ten-week campaign, he and Douglas avoided attacking each other.[32] Boddy's campaign depicted him as born in a log cabin, and highlighted his World War I service. The publisher campaigned under the slogan, "Manchester Boddy, the Democrat Every Body Wants."[b] Boddy stated that he was fighting for the "little man", and alleged that the average individual was overlooked by both big government and big labor.[33] However, his campaign, having a late start, was disorganized. The candidate himself had little charisma, and little presence as a public speaker. According to Rob Wagner, who wrote of the campaign in his history of Los Angeles newspapers of the era, Boddy "was all sizzle and no substance".[26]

The campaign calm broke off near the end of April 1950, when Boddy's Daily News and affiliated newspapers referred to the congresswoman as "decidedly pink" and "pink shading to deep red".[32] At the end of the month, the Daily News referred to her for the first time as "the pink lady".[32] Douglas generally ignored Boddy's attacks, which continued unabated through May. In a Daily News column, Boddy wrote that Douglas was part of "a small minority of red hots" which proposed to use the election to "establish a beachhead on which to launch a Communist attack on the United States".[34] One Boddy campaign publication was printed with red ink, and stated that Douglas "has too often teamed up with the notorious extreme radical, Vito Marcantonio of New York City, on votes that seem more in the interest of Soviet Russia than of the United States".[34]

On May 3, Congressman George Smathers defeated liberal Senator Claude Pepper for the Democratic Senate nomination in Florida.[35] Smathers' tactics included dubbing his opponent "Red Pepper" and distributing red-covered brochures, The Red Record of Senator Claude Pepper, that included a photograph of Pepper with Marcantonio.[36] Soon after Smathers' triumph in the primary, which in the days of the yellow dog South was tantamount to election, South Dakota Republican Senator Karl Mundt, who when in the House had served with Nixon on HUAC, sent him a letter telling him about Smathers' brochure. Senator Mundt wrote to Nixon, "It occurs to me that if Helen is your opponent in the fall, something of a similar nature might well be produced ..."[37] Douglas wrote of Senator Pepper's defeat, "The loss of Pepper is a great tragedy, and we are sick about it."[35] She also noted, "What a vicious campaign was carried on against him. No doubt the fur will begin to fly out here too", and "It is revolting to think of the depths to which people will go."[35]

Downey reentered the fray on May 22, when he made a statewide radio address on behalf of Boddy, stating his belief that Douglas was not qualified to be a senator.[38] He concluded, "Her record clearly shows very little hard work, no important influence on legislation, and almost nothing in the way of solid achievement. The fact that Mrs. Douglas has continued to bask in the warm glow of publicity and propaganda should not confuse any voter as to what the real facts are."[39]

Douglas brought an innovation to the race—a small helicopter, which she used to travel around the state at a time when there were few freeways linking California's cities. She got the idea from her friend, Texas Senator Lyndon Johnson, who had used a helicopter in his close 1948 race. Douglas leased the craft from a helicopter company in Palo Alto owned by Republican supporters, who hoped her influence would lead to a defense contract. When she used it to land in San Rafael, her local organizer, Dick Tuck, called it the "Helencopter", and the name stuck.[40]

In early April, polls gave Nixon some chance of winning the Democratic primary, which would mean his election was secured. He sent out mailings to Democratic voters. Boddy attacked Nixon for the mailings; Nixon responded that Democratic voters should have the opportunity to express no confidence in the Truman administration by voting for a Republican. "Democrats for Nixon", a group affiliated with Nixon's campaign, asked Democratic voters "as one Democrat to another" to vote for the congressman, sending out flyers which did not mention his political affiliation.[41] Boddy quickly struck back in his paper, accusing Nixon of misrepresenting himself as a Democrat.[42] A large ad in the same issue by the "Veterans Democratic Committee" warned Democratic voters that Nixon was actually a Republican and referred to him for the first time as "Tricky Dick".[41] The exchange benefited neither Nixon nor Boddy; Douglas won the primary on June 6 and exceeded their combined vote total.[43]

Republican contest

In mid-1949, Nixon, although anxious to advance his political career, was reluctant to run for the Senate unless he was confident of winning the Republican primary.[44] He considered his party's prospects in the House to be bleak, absent a strong Republican trend, and wrote "I seriously doubt if we can ever work our way back in power. Actually, in my mind, I do not see any great gain in remaining a member of the House, even from a relatively good District, if it means we would be simply a vocal but ineffective minority."[45][c]

In late August 1949, Nixon embarked on a putatively nonpolitical speaking tour of Northern California, where he was less well known, to see if his candidacy would be well received if he ran.[45] With many of his closest advisers urging him to do so, Nixon decided in early October to seek the Senate seat.[18] He hired a professional campaign manager, Murray Chotiner, who had helped to run successful campaigns for both Governor Warren and Senator Knowland and had played a limited role in Nixon's first congressional race.[46]

Nixon announced his candidacy in a radio broadcast on November 3, painting the race as a choice between a free society and state socialism.[47] Chotiner's philosophy for the primary campaign was to focus on Nixon and ignore the opposition.[48] Nixon did not indulge in negative campaigning in the primaries; according to Nixon biographer Irwin Gellman, the internecine warfare in the Democratic Party made it unnecessary.[49] The Nixon campaign spent most of late 1949 and early 1950 concentrating on building a statewide organization, and on intensive fundraising, which proved successful.[12][50]

Nixon had built part of his reputation in the House on his role in the Alger Hiss affair. Hiss's retrial for perjury after a July 1949 hung jury was a cloud over Nixon's campaign; if Hiss was acquitted, Nixon's candidacy would be in serious danger.[51] On January 21, 1950, the jury found Hiss guilty, and Nixon received hundreds of congratulatory messages, including one from the only living former President, Herbert Hoover.[52]

At the end of January 1950, a subcommittee of the California Republican Assembly, a conservative grassroots group, endorsed former Lieutenant Governor Frederick Houser (who had lost narrowly to Downey in 1944) over Nixon for the Senate candidacy by a 6–3 vote, only to be reversed by the full committee, which endorsed Nixon by 13–12.[53] Houser eventually decided against running.[54] Los Angeles County Supervisor Raymond Darby commenced a Senate run, but changed his mind and instead ran for lieutenant governor. Darby was defeated by incumbent Lieutenant Governor Goodwin Knight in the Republican primary.[55] Knight had also been considered likely to run for the Senate, but decided to seek re-election instead.[44] Actor Edward Arnold began a Senate run, but dropped it in late March, citing a lack of time to prepare his campaign.[56] Nixon was opposed for the Republican nomination only by cross-filing Democrats and by two fringe candidates: Ulysses Grant Bixby Meyer, a consulting psychologist for a dating service,[55] and former judge and law professor Albert Levitt, who opposed "the political theories and activities of national and international Communism, Fascism, and Vaticanism" and was unhappy that the press was paying virtually no attention to his campaign.[57]

On March 20, Nixon cross-filed in the two major party primaries, and two weeks later began to criss-cross the state in his campaign vehicle: a yellow station wagon with "Nixon for U.S. Senator" in big letters on both sides. According to one contemporary news account, in his "barnstorming tour", Nixon intended to "[talk] up his campaign for the U.S. Senate on street corners and wherever he can collect a crowd."[56] During his nine-week primary tour, he visited all of California's 58 counties, speaking sometimes six or eight times in a day.[23] His wife Pat Nixon stood by as her husband spoke, distributing campaign thimbles that urged the election of Nixon and were marked with the slogan "Safeguard the American Home". She distributed more than 65,000 by the end of the campaign.[35]

A Douglas supporter heard Nixon speak during the station wagon tour, and wrote to the congresswoman:

He gave a magnificent speech. He is one of the cleverest speakers I have ever heard. The questions on the Mundt-Nixon bill, his views on the loyalty oath, and the problem of international communism were just what he was waiting for. Indeed, he was so skillful—and, I might add, cagey—that those who came indifferent were sold, and even many of those who came to heckle went away with doubts ... If he is only a fraction as effective as he was here you have a formidable opponent on your hands.[58]

With no serious challenge from Republican opponents, Nixon won an overwhelming victory in the Republican primary, with his cross-filing rivals, Boddy, Douglas, and Desmond, dividing a small percentage of the vote but running well ahead of the two fringe candidates.[49]

Joint appearances

There were no candidate debates, but Douglas and Nixon met twice on the campaign trail during the primary season. The first meeting took place at the Commonwealth Club[d] in San Francisco, where Nixon waved a check for $100 that his campaign had received from "Eleanor Roosevelt", with an accompanying letter, "I wish it could be ten times more. Best wishes for your success."[49] The audience was shocked at the idea of Eleanor Roosevelt, widow of Democratic former president Franklin Roosevelt and known for her liberal views, contributing to Nixon's campaign.[49] Nixon went on to explain that the envelope was postmarked Oyster Bay, New York, and that the Eleanor Roosevelt who had sent the contribution was Eleanor Butler Roosevelt, the widow of former Republican president Theodore Roosevelt's eldest son.[49][59] The audience laughed,[49] and Douglas later wrote that she had been distracted and gave a poor speech.[e] A memo from Chotiner several days later noted that Boddy had failed to attend the function, and that Douglas wished that she had also not attended.[e]

A second joint appearance took place in Beverly Hills. According to Nixon campaign adviser Bill Arnold, Douglas arrived late, while Nixon was already speaking. Nixon ostentatiously looked at his watch, provoking laughter from the audience. The laughter recurred as Nixon, sitting behind Douglas as she spoke, fidgeted to indicate his disapproval of what she was saying; she appeared bewildered at the laughter. Douglas concluded her remarks and Nixon rose to speak again, but she did not stay to listen.[49]

General election

War in Korea, conflict in California

The rift in the Democratic party caused by the primary was slow to heal; Boddy's supporters were reluctant to join Douglas's campaign, even with President Truman's encouragement.[60] The President refused to campaign in California; he resented Democratic gubernatorial candidate James Roosevelt. Roosevelt, the eldest son of Franklin Roosevelt, had urged Democrats not to renominate Truman in 1948, but to instead nominate General Dwight Eisenhower.[60] Fundraising continued to be a major problem for Douglas, the bulk of whose financial support came from labor unions.[60] The weekend after the primary, Nixon campaign officials held a conference to discuss strategy for the general election campaign. They decided on a fundraising goal of just over $197,000 (today, about $2,400,000). They were helped in that effort when Democratic Massachusetts Congressman John F. Kennedy, a political opponent of Nixon's, came to Nixon's office and gave him a donation of $1,000 on behalf of Joseph P. Kennedy, Sr., his father.[61] John Kennedy indicated that he could not endorse Nixon, but that he would not be heartbroken if Douglas was returned to her acting career.[62] Joseph Kennedy later stated that he gave Nixon the money because Douglas was a communist.[61]

Nixon's positions generally favored large corporations and farming interests, while Douglas's did not, and Nixon reaped the reward with contributions from them.[63] Nixon favored the Taft-Hartley Act, passage of which had been bitterly opposed by labor unions; Douglas advocated its repeal. Douglas supported a requirement that federally subsidized water from reclamation projects only go to farms of not more than 160 acres (0.65 km2); Nixon fought for the repeal of that requirement.[63]

When the Korean War broke out in late June, Douglas and her aides feared being put on the defensive by Nixon on the subject of communism, and sought to preempt his attack.[64] Douglas's opening campaign speech included a charge that Nixon had voted with Marcantonio to deny aid to South Korea and to cut aid to Europe in half.[65] Chotiner later cited this as the crucial moment of the campaign:

She was defeated the minute she tried to do it, because she could not sell the people of California that she would be a better fighter against communism than Dick Nixon. She made the fatal mistake of attacking our strength instead of sticking to attacking our weakness.[66][67]

Nixon objected to Douglas's speech, stating that he had opposed the Korea bill because it did not include aid to Taiwan, and had supported it once the aid had been included.[68] As for the Europe charge, according to Nixon biographer Stephen Ambrose, Nixon was so well known as a supporter of the Marshall Plan that Douglas's charge had no credibility.[66] In fact, Nixon had opposed a two-year reauthorization of the Marshall Plan, favoring a one-year reauthorization with a renewal provision, allowing for more congressional oversight.[66]

Nixon realized that the battle in California would be fought over the threat of communism, and his campaign staff began to research Douglas's voting record.[61] Republican officials in Washington sent the campaign a report listing 247 times Marcantonio (who generally followed the Democratic line) and Douglas had voted together, and 11 times that they had not.[69] Nixon biographer Conrad Black suggests that Nixon's strategy in keeping the focus on communism was to "distract [Douglas] from her strengths—a sincere and attractive woman fighting bravely for principles most Americans would agree with if they were packaged correctly—to scrapping ... on matters where she could not win."[70] Chotiner stated 20 years later that Marcantonio suggested the comparison of voting records, as he disliked Douglas for failing to support his beliefs fully.[71]

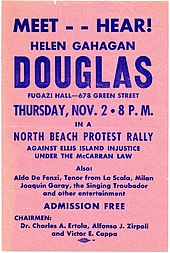

Public support for the Korean War initially resulted in anger towards communists, and Nixon advocated the passage of legislation he had previously introduced with Senator Mundt which would tighten restrictions on communists and the Communist Party. Douglas argued that there was already sufficient legislation to effect any necessary prosecutions, and that the Mundt-Nixon bill (soon replaced by the similar McCarran-Wood bill) would erode civil liberties.[72] With the bill sure to pass, Douglas was urged to vote in favor to provide herself with political cover. She declined to do so, though fellow California Representative Chester E. Holifield warned her that she would not be able to get around the state fast enough to explain her vote and Nixon would "beat [her] brains in".[73] Douglas was one of only 20 representatives (including Marcantonio) who voted against the bill. Truman vetoed it; Congress enacted it over his veto by wide margins in late September. Douglas was one of 47 representatives (including Marcantonio) to vote to sustain the veto.[74] In a radio broadcast soon after the veto override, Douglas announced that she stood with the President, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in their fight against communism.[75]

Debut of the Pink Sheet

On September 10, Eleanor Roosevelt, the late president's widow and the gubernatorial candidate's mother, arrived in California for a quick campaign swing to support her son and Douglas before she had to return to New York as a delegate to the United Nations. Douglas hoped that the former first lady's visit would mark a turning point in the campaign.[76] At a Democratic rally featuring Mrs. Roosevelt the next day in Long Beach, Nixon workers first handed out a flyer headed "Douglas–Marcantonio Voting Record", printed with dark ink on pink paper. The legal-size flyer compared the voting records of Douglas and Marcantonio, principally in the area of national security, and concluded that they were indistinguishable. In contrast, the flyer said, Nixon had voted entirely in opposition to the "Douglas–Marcantonio Axis".[77] It implied that sending Douglas to the Senate would be no different from electing Marcantonio, and asked if that was what Californians wanted.[77] The paper soon became known as the "Pink Sheet".[77] Chotiner later stated that the color choice was made at the print shop when campaign officials approved the final copy, and "for some reason or other it just seemed to appeal to us for the moment".[f] An initial print run of 50,000 was soon followed by a reprint of 500,000, distributed principally in heavily populated Southern California.[f]

Douglas made no immediate response to the Pink Sheet, despite the advice of Mrs. Roosevelt, who appreciated its power and urged her to answer it.[78] Douglas later stated that she had failed to understand the appeal of the Pink Sheet to voters, and simply thought it absurd.[78] Nixon followed up on the Pink Sheet with a radio address on September 18, accusing Douglas of being "a member of a small clique which joins the notorious communist party-liner Vito Marcantonio of New York, in voting time after time against measures that are for the security of this country".[79] He assailed Douglas for advocating that Taiwan's seat on the United Nations Security Council be given to the People's Republic of China, as appeasement towards communism.[g]

Late in September, Douglas complained of alleged whispering campaigns aimed at her husband's Jewish heritage, and which stated that he was a communist.[80] At the end of September, the splits in the Democratic Party became open when 64 prominent Democrats, led by George Creel, endorsed Nixon and castigated Douglas. Creel said, "She has voted consistently with Vito Marcantonio. Belated flag-waving cannot erase this damning record, nor can the tawdry pretense of 'liberalism' excuse it."[81] According to Creel, Downey was working behind the scenes to secure Nixon's election.[82]

James Roosevelt's lackluster campaign led Douglas backers to state that he was not only failing to help Douglas, he was not even helping himself.[83] With polls showing the two major Democratic candidates in dire straits, Roosevelt wrote to President Truman, proposing that Truman campaign in the state in the final days before the election. Truman refused to do so.[84] He also declined Douglas's pleas for a letter of support (privately calling her "one of the worst nuisances"), and even refused to allow her to be photographed with him at a signing ceremony for a water bill which would benefit California.[85] When Truman flew to Wake Island in early October to confer with General Douglas MacArthur regarding the Korean situation, he returned via San Francisco, but told the press he had no political appointments scheduled.[84] He spoke at an event at the War Memorial Opera House during his stopover, but both Roosevelt and Douglas were relegated to orchestra-level seats, far from the presidential box.[84] Vice President Alben Barkley did visit the state to campaign for the Democrats. However, Time magazine wrote that he did not appear to be helpful to Douglas's campaign. The Vice President stated that while he was not familiar with Douglas's votes, he was certain that she had voted the way she did out of sincere conviction and urged Californians to give the Senate a "dose of brains and beauty".[86] Attorney General McGrath also came to California to campaign for the Democrats,[87] and freshman Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota tirelessly worked the San Joaquin Valley, talking to farmers and workers.[88]

Name-calling and supporters: the final days

Douglas adopted Boddy's "Tricky Dick" nickname for Nixon, and also referred to him as "pee wee".[89] Her name-calling had an effect on Nixon: when told she had called him "a young man with a dark shirt" in an allusion to Nazism, he inquired, "Did she say that? Why, I'll castrate her."[h] Campaign official Bill Arnold joked that it would be difficult to do, and Nixon replied that he would do it anyway.[h] Nixon returned the attacks; at friendly gatherings and especially at all-male events, he stated that Douglas was "pink right down to her underwear".[88]

Douglas's last large-scale advertisement blitz contained another Nazi allusion. Citing five votes in which Nixon and Marcantonio had voted together and in opposition to Douglas, it accused Nixon of using "the big lie" and stated: "HITLER invented it/STALIN perfected it/NIXON uses it".[90] Nixon responded, "Truth is not smear. She made the record. She has not denied a single vote. The iron curtain of silence has closed around the opposition camp."[91] Through the final days of the campaign, he struck a constant drumbeat: Douglas was soft on communism.[92]

Though polls showed Nixon well ahead, his campaign did not let up. A fundraising solicitation warned, "Right Now Nixon Is Losing ... Not Enough Money".[93] Skywriting urged voters to cast their ballots for him. Borrowing an idea from Nixon's 1946 campaign, the campaign announced that people should answer their phones, "Vote for Nixon"; random calls would be made from campaign headquarters and households that answered their phones that way would receive scarce consumer appliances. Chotiner even instructed that 18-month-old copies of The Saturday Evening Post, containing a flattering story about Nixon, be left in doctor's offices, barber shops, and other places where people wait across the state.[93]

In the last days of the campaign, Douglas finally began to receive some of the support she had hoped for. Boddy's paper endorsed her, while Truman praised her.[94] Douglas's actor husband, Melvyn Douglas, on tour with the play Two Blind Mice throughout the campaign, spoke out on behalf of his wife,[91] as did movie stars Myrna Loy and Eddie Cantor.[95] Nixon had several Hollywood personalities supporting him, including Howard Hughes, Cecil B. DeMille and John Wayne.[95] Another actor, Ronald Reagan, was among Douglas's supporters, but when his girlfriend and future wife Nancy Davis took him to a pro-Nixon rally led by actress ZaSu Pitts, he was converted to Nixon's cause and led quiet fundraising for him. Douglas was apparently unaware of this—30 years later she mentioned Reagan in her memoirs as someone who worked hard for her.[96][97]

Chotiner had worked on Warren's 1942 campaign, but had parted ways from him, and the popular governor did not want to be connected to the Nixon campaign.[98] Nonetheless, Chotiner sought to maneuver him into an endorsement.[99] Chotiner instructed Young Republicans head and future congressman Joseph F. Holt to follow Douglas from appearance to appearance and demand to know who she was supporting for governor,[100] as other Young Republicans handed out copies of the Pink Sheet.[96] Douglas repeatedly avoided the question, but with four days to go before the election and the Democratic candidate near exhaustion from the bitter campaign, she responded that she hoped and prayed that Roosevelt would be elected.[101] Holt contacted a delighted Chotiner, who had a reporter ask Warren about Douglas's comments, and the governor responded, "In view of her statement, I might ask her how she expects I will vote when I mark my ballot for United States senator on Tuesday."[101] Chotiner publicized this response as an endorsement of Nixon, and the campaign assured voters that Nixon would be voting for Warren as well.[102]

Despite the polls, Douglas was confident that the Democratic registration edge would lead her to victory, so much so that she offered a Roosevelt staffer a job in her senatorial office.[103] On election day, November 7, 1950, Nixon defeated Douglas by 59 percent to 41.[104] Of California's 58 counties, Douglas won only five, all in Northern California and with relatively small populations;[i][105] Nixon won every urban area.[106] Although Warren defeated Roosevelt by an even larger margin, Nixon won by the greatest number of votes of any 1950 Senate candidate. Douglas, in her concession speech, declined to congratulate Nixon.[104] Marcantonio was also defeated in his New York district.[107]

Aftermath

Candidates

A week after the election, Downey announced that he was resigning for health reasons. Warren appointed Nixon to the short remainder of Downey's term; under the Senate rules at the time, this gave Nixon seniority over the senators sworn in during January.[108] Nixon took office on December 4, 1950.[109] He used little of his seniority, since in November 1952 he was elected vice president as Dwight Eisenhower's running mate, the next step on a path that would lead him to the presidency in 1969. Downey, who as a former senator retained floor privileges, was hired as a lobbyist by oil interests. In 1952, as Republicans took over the White House and control of both houses of Congress, he was fired. An aide stated that the big corporations did not need Downey anymore.[110] Boddy, dispirited by his election defeat and feeling let down by the average citizens for whom he had sought to advocate, lapsed into semi-retirement after his primary defeat. In 1952, he sold his interest in the Daily News, which went into bankruptcy in December 1954.[111]

It was rumored that Douglas would be given a political appointment in the Truman administration,[112] but the Nixon-Douglas race had made such an appointment too controversial for the President.[112] According to Democratic National Committee vice-chair India Edwards, a Douglas supporter, the former congresswoman could not have been appointed dogcatcher.[113] In 1952, she returned to acting, and eight years later campaigned for John F. Kennedy during Nixon's first, unsuccessful presidential run.[112] She also campaigned for George McGovern in his unsuccessful bid to prevent Nixon's 1972 reelection, and called for his ouster from office during the Watergate scandal.[114]

Less than a week after the election, Douglas wrote to one of her supporters that she did not think there was anything her campaign could have done to change the result.[115] Blaming the war, voter mistrust of Truman's foreign policy, and high prices at home, Douglas stated that she lost in California because Nixon was able to take a large part of the women's vote and the labor vote.[115] Later in November, she indicated that liberals must undertake a massive effort to win in 1952.[116] In 1956, she stated in an interview that, while Nixon had never called her a communist, he had designed his whole campaign to create the impression that she was a communist or "communistic".[113] In 1959, she wrote that she had not particularly wanted to be a senator,[112] and in 1962 she stated that the policy of her campaign was to avoid attacks on Nixon.[112] In her memoirs, published posthumously in 1982, she wrote, "Nixon had his victory, but I had mine ... He hadn't touched me. I didn't carry Richard Nixon with me, thank God."[117] She concluded her chapter on the 1950 race with, "There's not much to say about the 1950 campaign except that a man ran for Senate who wanted to get there, and didn't care how."[118]

In 1958, Nixon, by then vice president, allegedly stated that he regretted some of the tactics his campaign had used in the campaign against Douglas, blaming his youth.[119] When the statements were reported, Nixon denied them. He issued press releases defending his campaign, and stating that any impression that Douglas was pro-communist was justified by her record.[119] He said Douglas was part of a whispering campaign accusing him of being "anti-Semitic and Jim Crow".[120] In his 1978 memoirs, he stated that "Helen Douglas lost the election because the voters of California in 1950 were not prepared to elect as their senator anyone with a left-wing voting record or anyone they perceived as being soft on or naive about communism."[121] He indicated that Douglas faced difficulties in the campaign because of her gender, but that her "fatal disadvantage lay in her record and in her views".[121]

History and legend

| Elections in California |

|---|

|

Contemporary accounts ascribed the result to a number of causes. Douglas friend and former Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes blamed Roosevelt's weak candidacy and what he believed was Nixon's use of the red scare. Supervisor John Anson Ford of Los Angeles County chalked up the result to Nixon's skill as a speaker and a lack of objective reporting by the press. Douglas's campaign treasurer, Alvin Meyers, stated that while labor financed Douglas's campaign, it failed to vote for her, and blamed the Truman Administration for "dumping" her.[115] Douglas's San Diego campaign manager claimed that 500,000 people in San Diego and Los Angeles had received anonymous phone calls alleging Douglas was a communist, though he could not name anyone who had received such a call.[122] Time magazine wrote that Nixon triumphed "by making the Administration's failures in Asia his major issue".[123]

As Nixon continued his political rise and then moved towards his downfall, the 1950 race increasingly took on sinister tones. According to Nixon biographer Earl Mazo, "Nothing in the litany of reprehensible conduct charged against Nixon, the campaigner, has been cited more often than the tactics by which he defeated Congresswoman Helen Gahagan Douglas for senator."[124] Douglas friend[125] and McGovern campaign manager Frank Mankiewicz, in his 1973 biography, Perfectly Clear: Nixon from Whittier to Watergate, focused on the race and the Pink Sheet, and alleged that Nixon never won a free election, that is, one without "major fraud".[122]

Historian Ingrid Scobie came to a different conclusion in her biography of Douglas, Center Stage. Scobie concluded that, given voter attitudes at the time, no woman could have won that race. Scobie stated that Nixon's tactics, which used voter anger at communists, contributed to the magnitude of Douglas's defeat, as did the fragmentation of the California Democratic Party in 1950, the weakness of Roosevelt at the head of the ticket, Douglas's idealistic positions (to the left of many California Democrats) and Boddy's attacks.[126] In his early biography of Nixon, Mazo contrasted the two campaigns and concluded, "when compared with the surgeons of the Nixon camp, the Douglas operators performed like apprentice butchers".[127]

Both Roger Morris and Greg Mitchell (who wrote a book about the 1950 race) conclude that Nixon spent large sums of money on the campaign, with Morris estimating $1–2 million (perhaps $12 million—$24 million today) and Mitchell suggesting twice that. Gellman, in his later book, conceded that Nixon's officially reported amount of $4,209 was understated, but indicated that campaign finance law at that time was filled with loopholes, and few if any candidates admitted to their full spending. He considered Morris's and Mitchell's earlier estimates, though, to be "guess[es]" and "fantastic".[128] Black suggests that Nixon spent about $1.5 million and Douglas just under half of that.[129]

Scobie summed up her discussion of Douglas's defeat,

As an actress, she entered Broadway as a star on sheer talent and little training ... [As an opera singer], she sang abroad for two summers, fully expecting that the next step would be the Metropolitan Opera. In politics after five months of working with the [California Democratic] Women's Division, it seemed only natural that she head the state's organization and serve as Democratic National Committeewoman. Restless after three years in those positions, she saw the possibility of becoming a member of Congress as a logical next step. Only four years later, she felt ready to run for the Senate. But her lack of political experience and her inflexible stands on political issues, along with gender questions, eroded the support of the Democratic Party in 1950. What in fact may have hurt her the most is that for which she is most remembered—her idealism.[130]

Primary results

Democratic

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helen Gahagan Douglas | 734,842 | 46.98 | |

| Manchester Boddy | 379,077 | 24.23 | |

| Richard Nixon | 318,840 | 20.38 | |

| Earl D. Desmond | 96,752 | 6.19 | |

| Ulysses Grant Bixby Meyer | 34,707 | 2.22 | |

| Total votes | 1,564,218 | 100.00 | |

Republican

| Candidate | Votes | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Richard Nixon | 740,465 | 64.59 | |

| Manchester Boddy | 156,884 | 13.68 | |

| Helen Gahagan Douglas | 153,788 | 13.41 | |

| Earl D. Desmond | 60,613 | 5.29 | |

| Ulysses Grant Bixby Meyer | 18,783 | 1.64 | |

| Albert Levitt | 15,929 | 1.39 | |

| Total votes | 1,146,462 | 100.00 | |

General election results, November 7, 1950

| Party | Candidate | Votes | % | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Republican | Richard Nixon | 2,183,454 | 59.23 | |||

| Democratic | Helen Gahagan Douglas | 1,502,507 | 40.76 | |||

| Total votes | 3,686,315 | 100.00 | ||||

| Turnout | 73.32 | |||||

| Republican gain from Democratic | ||||||

Results by county

Final results from the Secretary of State of California:[105]

| County | Nixon | Votes | Douglas | Votes | Write-ins | Votes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mono | 76.41% | 664 | 23.59% | 205 | 0% | 0 |

| Orange | 73.87% | 55,090 | 26.13% | 19,484 | 0% | 3 |

| Inyo | 72.81% | 2,702 | 27.19% | 1,009 | 0% | 0 |

| Alpine | 72.09% | 93 | 27.91% | 36 | 0% | 0 |

| Imperial | 72.07% | 8,793 | 27.91% | 3,405 | 0.01% | 1 |

| Del Norte | 70.70% | 2,155 | 29.30% | 893 | 0% | 0 |

| San Benito | 70.27% | 2,992 | 29.73% | 1,266 | 0% | 0 |

| Riverside | 67.35% | 36,617 | 32.65% | 17,751 | 0% | 3 |

| Marin | 67.27% | 21,400 | 32.73% | 10,411 | 0.01% | 2 |

| Sutter | 66.63% | 4,993 | 33.37% | 2,501 | 0% | 0 |

| Mariposa | 65.16% | 1,496 | 34.84% | 800 | 0% | 0 |

| San Mateo | 65.12% | 57,118 | 34.87% | 30,587 | 0.01% | 8 |

| Santa Cruz | 65.10% | 17,431 | 34.90% | 9,343 | 0% | 0 |

| Glenn | 64.87% | 3,416 | 35.11% | 1,849 | 0.02% | 1 |

| Tulare | 64.31% | 25,625 | 35.69% | 14,221 | 0% | 0 |

| Colusa | 63.30% | 2,349 | 36.70% | 1,362 | 0% | 0 |

| Lake | 62.46% | 3,223 | 37.54% | 1,937 | 0% | 0 |

| San Luis Obispo | 62.18% | 11,812 | 37.82% | 7,184 | 0% | 0 |

| Sonoma | 61.89% | 23,600 | 38.10% | 14,529 | 0% | 1 |

| Santa Clara | 61.80% | 57,318 | 38.18% | 35,413 | 0.01% | 10 |

| Santa Barbara | 61.55% | 20,521 | 38.45% | 12,817 | 0% | 0 |

| Stanislaus | 61.47% | 22,803 | 38.52% | 14,290 | 0.01% | 2 |

| San Diego | 61.38% | 115,119 | 38.61% | 72,433 | 0.01% | 11 |

| Humboldt | 61.26% | 14,135 | 38.73% | 8,937 | 0% | 1 |

| Nevada | 61.00% | 4,725 | 39.00% | 3,021 | 0% | 0 |

| Tuolumne | 60.58% | 3,307 | 39.42% | 2,152 | 0% | 0 |

| Los Angeles | 60.33% | 931,803 | 39.66% | 612,510 | 0.01% | 195 |

| Napa | 60.23% | 9,449 | 39.77% | 6,239 | 0% | 0 |

| King | 59.51% | 6,977 | 40.49% | 4,747 | 0% | 0 |

| San Bernardino | 59.48% | 53,956 | 40.51% | 36,751 | 0.01% | 4 |

| Mendocino | 59.00% | 7,197 | 40.99% | 5,000 | 0.01% | 1 |

| Merced | 58.85% | 9,922 | 41.14% | 6,937 | 0.01% | 1 |

| Monterey | 58.66% | 19,506 | 41.32% | 13,741 | 0.02% | 6 |

| Tehama | 57.95% | 3,939 | 42.05% | 2,858 | 0% | 0 |

| Fresno | 57.90% | 48,537 | 42.10% | 35,290 | 0% | 0 |

| Madera | 57.88% | 5,307 | 42.12% | 3,862 | 0% | 0 |

| San Francisco | 57.42% | 165,631 | 42.58% | 122,807 | 0% | 4 |

| Yuba | 57.32% | 4,166 | 42.68% | 3,102 | 0% | 0 |

| Modoc | 57.30% | 1,888 | 42.70% | 1,407 | 0% | 0 |

| Calaveras | 56.66% | 2,489 | 43.85% | 1,904 | 0% | 0 |

| Butte | 56.15% | 12,512 | 43.85% | 9,770 | 0% | 0 |

| Kern | 55.73% | 34,452 | 44.27% | 27,363 | 0% | 1 |

| Amador | 55.71% | 2,059 | 44.29% | 1,637 | 0% | 0 |

| Siskiyou | 55.32% | 6,774 | 44.68% | 5,472 | 0% | 0 |

| Sierra | 54.94% | 639 | 44.97% | 523 | 0.09% | 1 |

| San Joaquin | 54.87% | 31,046 | 44.99% | 25,459 | 0.14% | 79 |

| El Dorado | 54.81% | 3,833 | 45.19% | 3,160 | 0% | 0 |

| Trinity | 54.41% | 1,228 | 45.59% | 1,029 | 0% | 0 |

| Alameda | 53.52% | 150,273 | 46.47% | 130,492 | 0.01% | 15 |

| Ventura | 52.37% | 16,543 | 47.62% | 15,042 | 0% | 1 |

| Yolo | 52.08% | 6,411 | 47.92% | 5,899 | 0% | 0 |

| Sacramento | 51.08% | 49,798 | 48.92% | 47,689 | 0% | 0 |

| Placer | 50.46% | 7,835 | 49.54% | 7,691 | 0% | 0 |

| Contra Costa | 49.82% | 44,652 | 50.17% | 44,968 | 0% | 3 |

| Lassen | 48.11% | 2,556 | 51.89% | 2,757 | 0% | 0 |

| Shasta | 44.90% | 5,841 | 55.10% | 7,156 | 0% | 0 |

| Solano | 43.89% | 14,385 | 56.11% | 18,389 | 0% | 0 |

| Plumas | 43.79% | 2,353 | 56.21% | 3,020 | 0% | 0 |

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ Colloquially called the "Uppie and Downey" ticket.

- ^ Denton 2009, p. 144. Note that Denton incorrectly says Boddy (pronounced with a long o) served in World War II, not World War I.

- ^ Republicans controlled the House for only two of the remaining forty-five years of his life.

- ^ By some accounts, the Press Club.

- ^ a b Mitchell 1998, p. 37. Some sources claim that Nixon did not explain that it was Eleanor Butler Roosevelt who sent the contribution, apparently in an attempt to get the crowd to think Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt was a supporter. For example, Morris does not mention an explanation of "which Eleanor Roosevelt", despite the contemporaneous account in People Today, most other Nixon biographers do. In Douglas's memoir (Douglas 1982, p. 314) she does not mention an explanation by Nixon and indicates that she left the meeting and called the former first lady, who assured her of her continued support; the former president's later book In the Arena contains (pages 194–195) a recounting of the anecdote, with explanation, with the amount inflated to $500. Fortnight, "From Wild West Barker to US Senator?" & May 26, 1950, p. 7 states "One morning, to his astonishment, Nixon received a campaign contribution check for $100 signed Eleanor B. Roosevelt. It was, however, from Oyster Bay, not Hyde Park, Eleanor B. being wife of the grandson [actually son] of the late T.R.". Douglas herself states in her memoir (Douglas 1982, p. 314) that any false attempt by Nixon to claim Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt as a supporter would have been quickly unmasked.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, p. 581. Chotiner told several variations on this story; this version seems to be the most widespread.

- ^ Black 2007, p. 161. That transfer would take place in 1971, while Nixon was president.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, p. 326. Mitchell places this story in the primary season, and says that Nixon and Douglas were speaking in the same town on the same day; Arnold went to Douglas's rally and reported back to his boss, and the castration exchange followed.

- ^ Note that most books state that Douglas won only four counties, though Jonathan Bell gets it right.

- ^ a b 1,911 scattered write-ins combined for both parties not included in totals. Douglas also received 2,326 write-in votes as an Independent-Progressive (Henry A. Wallace's party) but as she was not given that listing on the general election ballot, she must have declined it.

Citations

- ^ a b Black 2007, p. 145.

- ^ Scobie 1992, p. 224.

- ^ Rosenstone 1970, pp. 291–3.

- ^ Rosenstone 1970, p. 302.

- ^ Rosenstone 1970, pp. 293–94.

- ^ Rosenstone 1970, pp. 298–99.

- ^ Bochin 1990, p. 23.

- ^ Bochin 1990, p. 3.

- ^ Bochin 1990, p. 22.

- ^ Ambrose 1988, pp. 197–98.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 516.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, p. 291.

- ^ Black 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 165.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, p. 545.

- ^ MeasuringWorth.

- ^ a b Douglas 1982, p. 288.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, p. 285.

- ^ Ambrose 1988, p. 209.

- ^ Scobie 1992, p. 232.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, p. 552.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, p. 292.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, pp. 296–97.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, p. 553.

- ^ Los Angeles Daily News & March 31, 1950.

- ^ a b Wagner 2000, p. 268.

- ^ Wagner 2000, p. 267.

- ^ Mazo 1959, pp. 76–7.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 297.

- ^ Scobie 1992, p. 237.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 555.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, p. 299.

- ^ Rosenstone 1970, p. 303.

- ^ a b Davies & May 30, 1950.

- ^ a b c d Gellman 1999, p. 300.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 310.

- ^ Mundt & May 9, 1950.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 301.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 302.

- ^ Mitchell 1998, p. 35.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, p. 303.

- ^ Los Angeles Daily News & June 5, 1950.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 304.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, p. 282.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, p. 283.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 286.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 535.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f g Gellman 1999, pp. 304–5.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 295.

- ^ Ambrose 1988, p. 201.

- ^ Ambrose 1988, p. 205.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 293.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 298.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, pp. 549–50.

- ^ a b 'Frank Observer' & March 29, 1950.

- ^ Fortnight, "Political Roundup" & May 26, 1950, p. 6.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 556–57.

- ^ People Today & September 12, 1950.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, p. 309.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, pp. 306–7.

- ^ Ambrose 1988, pp. 210–1.

- ^ a b Ambrose 1988, pp. 213–14.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 571.

- ^ Davies & November 1, 1950.

- ^ a b c Ambrose 1988, pp. 215–17.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 572.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 311.

- ^ Mitchell 1998, p. 65.

- ^ Black 2007, pp. 156–57.

- ^ Bonafede & May 30, 1970.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 313.

- ^ Mitchell 1998, p. 130.

- ^ Gellman 1999, pp. 320–1.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 323.

- ^ Mitchell 1998, pp. 142–3.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, p. 308.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, p. 583.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 584.

- ^ Gellman 1999, pp. 317–18.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 595.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 596.

- ^ Time & September 25, 1950.

- ^ a b c Gellman 1999, pp. 321–22.

- ^ Mitchell 1998, p. 162.

- ^ Time & October 23, 1950.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 597.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, p. 598.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 318.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 330.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, p. 332.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 333.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, pp. 606–7.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 331.

- ^ a b Denton 2009, p. 167.

- ^ a b Morris 1990, pp. 601–2.

- ^ Douglas 1982, p. 323.

- ^ Katcher 1967, p. 260.

- ^ Katcher 1967, pp. 256–57.

- ^ Katcher 1967, p. 257.

- ^ a b Katcher 1967, p. 261.

- ^ Katcher 1967, pp. 261–62.

- ^ Scobie 1992, pp. 274–76.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, p. 335.

- ^ a b c Jordan & November 7, 1950, p. 11.

- ^ Mitchell 1998, p. 244.

- ^ Conklin & November 8, 1950.

- ^ Black 2007, p. 165.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 346.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 614.

- ^ Rosenstone 1970, p. 304.

- ^ a b c d e Morris 1990, pp. 618–19.

- ^ a b Mitchell 1998, p. 255.

- ^ Mitchell 1998, p. 258.

- ^ a b c Mitchell 1998, p. 248.

- ^ Gellman 1999, p. 337.

- ^ Douglas 1982, pp. 334–35.

- ^ Douglas 1982, p. 341.

- ^ a b Mitchell 1998, p. 257.

- ^ Morris 1990, p. 617.

- ^ a b Nixon 1978, p. 78.

- ^ a b Gellman 1999, p. 339.

- ^ Time & November 13, 1950.

- ^ Mazo 1959, p. 71.

- ^ Douglas 1982, p. 310.

- ^ Scobie 1992, pp. 280–1.

- ^ Mazo 1959, p. 80.

- ^ Gellman 1999, pp. 340–41.

- ^ Black 2007, p. 166.

- ^ Scobie 1992, p. 281.

- ^ a b Jordan & June 6, 1950, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Graf 1951, p. 2.

Bibliography

- Ambrose, Stephen (1988). Nixon: The Education of a Politician, 1913–1962. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-65722-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Black, Conrad (2007). Richard M. Nixon: A Life in Full. New York, NY: PublicAffairs Books. ISBN 978-1-58648-519-1.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bochin, Hal (1990). Richard Nixon: Rhetorical Strategist. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-26108-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bonafede, Dan (May 30, 1970). "Men behind Nixon/Murray Chotiner: early tutor, political counselor". National Journal. 2: 1130.

- Denton, Sally (2009). The Pink Lady. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-480-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Douglas, Helen Gahagan (1982). A Full Life. Garden City, NY: Doubleday and Co. ISBN 978-0-385-11045-7. OCLC 7796719.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Political Roundup". Fortnight: the Newsmagazine of California: 6. May 26, 1950.

- "From Wild West Barker to US Senator?". Fortnight: the Newsmagazine of California: 7. May 26, 1950.

- Gellman, Irwin (1999). The Contender. The Free Press. ISBN 978-1-4165-7255-8. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Katcher, Leo (1967). Earl Warren: A Political Biography. McGraw Hill Book Co.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mazo, Earl (1959). Richard Nixon: A Political and Personal Portrait. New York, NY: Harper & Brothers Publishers.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mitchell, Greg (1998). Tricky Dick and the Pink Lady. New York, NY: Random House. ISBN 978-0-679-41621-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Morris, Roger (1990). Richard Milhous Nixon: The Rise of an American Politician. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-8050-1834-9. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Nixon, Richard (1978). RN: The Memoirs of Richard Nixon. New York, NY: Grosset and Dunlop. ISBN 978-0-671-70741-5.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "Red-hot Senate race". People Today. September 12, 1950.

In a recent debate, he read a signature on a contribution he'd just received: Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Douglas gulped. Then he pointed out the signature on the envelope—it was from Mrs. T.R. Roosevelt Jr. of the Republican Oyster Bay Roosevelts.

- Rosenstone, Robert A. (December 1970). "Manchester Boddy and the L.A. Daily News". The California Historical Society Quarterly. XLIX (4): 291–307.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Scobie, Ingrid Winther (1992). Center Stage: Helen Gahagan Douglas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-506896-2.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - "California: Mamma knows best". Time. September 25, 1950. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- "Political notes: Always leave them laughin'". Time. October 23, 1950. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- "National affairs: The Senate". Time. November 13, 1950. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- Wagner, Rob (2000). Red Ink, White Lies: The Rise and Fall of Los Angeles Newspapers 1920–1962. Dragonflyer Press. ISBN 978-0-944933-80-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help)

Other sources

- Conklin, William (November 8, 1950). "Marcantonio loses his seat to Donovan, Coalition choice". The New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2009. (subscription required)

- Davies, Lawrence (May 30, 1950). "3 clash on Coast in Senate contest". The New York Times. Retrieved August 5, 2009. (subscription required)

- Davies, Lawrence (November 1, 1950). "California tests communism issue". The New York Times. Retrieved June 6, 2009. (subscription required)

- Frank Observer (obviously a pseudonym) (March 29, 1950). "Actor Arnold drops U.S. Senate bid". Los Angeles Daily News. p. 8.

- Graf, William (1951). "Statistics of the Congressional Election of November 7, 1950" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. p. 2. Retrieved June 29, 2009.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jordan, Frank (June 6, 1950). "State of California Statement of Vote, Direct Primary Election and Special State-wide Election, June 6, 1950". California State Printing Office.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Jordan, Frank (November 7, 1950). "State of California Statement of Vote, General Election, November 7, 1950". California State Printing Office.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Boddy files petition in Senate race; Mayor Bowron signer". Los Angeles Daily News. March 31, 1950. p. 3.

- "Nixon, Republican, misrepresents himself as a Democrat in election dodge". Los Angeles Daily News. June 5, 1950. p. 3.

- "Six Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a U.S. Dollar Amount, 1774 to Present". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved June 19, 2009. (Consumer bundle)

- Mundt, Karl (May 9, 1950). "Letter from Sen. Karl Mundt to Richard Nixon, May 9, 1950, on file in the Richard M. Nixon Presidential Library and Museum, 1950 Senate race files, box 1".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)

Further reading

- Bell, Jonathan (1988). The Liberal State on Trial. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-13356-2.