Ural-Altaic languages

| Ural–Altaic | |

|---|---|

| (obsolete) | |

| Geographic distribution | Eurasia |

| Linguistic classification | Proposed language family |

| Subdivisions | |

| Language codes | |

| Glottolog | None |

Distribution of Uralic, Altaic, and Yukaghir languages | |

Ural–Altaic, also Uralo-Altaic or Uraltaic, is an obsolete language-family proposal uniting the Uralic and Altaic languages.

Originally suggested in the 19th century, the hypothesis remained debated into the mid 20th century, often with disagreements exacerbated by pan-nationalist agendas,[1] enjoyed its greatest popularity by the proponents in Britain.[2] Since the 1960s, the hypothesis has been widely rejected.[3][4][5][6] From the 1990s, interest in a relationship between the Altaic, Indo-European and Uralic families has been revived in the context of the Eurasiatic linguistic superfamily[7] hypothesis. Bomhard (2008) treats Uralic, Altaic and Indo-European as Eurasiatic daughter groups on equal footing.[8]

History of the hypothesis

In a book published in 1730, Philip Johan von Strahlenberg, Swedish explorer and prisoner-of-war in Siberia, described Finno-Ugric, Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Caucasian languages as sharing common features.

Danish philologist Rasmus Christian Rask described what he vaguely called "Scythian" languages in 1834, which included Finno-Ugric, Turkic, Samoyedic, Eskimo, Caucasian, Basque and others.

The hypothesis[clarification needed] was elaborated at least as early as 1836 by W. Schott[9] and in 1838 by F. J. Wiedemann.[10]

The "Altaic" hypothesis, as mentioned by Finnish linguist and explorer Matthias Castrén[11][12] by 1844, included Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic, collectively known as "Chudic", and Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic, collectively known as "Tataric". Subsequently, Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic came to be referred to as Altaic languages, whereas Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic were called Uralic. The similarities between these two families led to their retention in a common grouping, named Ural–Altaic.

Between the 1850s and 1870s, there were efforts by Frederick Roehrig to including some Native American languages in a "Turanian" or "Ural-Altaic" family, and between the 1870s and 1890s speculations about links with Basque.[13]

In Hungary the idea of the Ural–Altaic relationship remained widely implicitly accepted in the late 19th and the mid-20th century, though more out of pan-nationalist than linguistic reasons, and without much detailed research carried out. Elsewhere the notion had sooner fallen into discredit, with Ural–Altaic supporters elsewhere such as the Finnish Altaicist Martti Räsänen being in the minority.[14] The contradiction between Hungarian linguists' convictions and the lack of clear evidence eventually provided motivation for scholars such as Aurélien Sauvageot and Denis Sinor to carry out more detailed investigation of the hypothesis, which so far has failed to yield generally accepted results. Nicholas Poppe in his article The Uralo-Altaic Theory in the Light of the Soviet Linguistics (1940) also attempted to refute Castrén's views by showing that the common agglutinating features may have arisen independently.[15]

Beginning in the 1960s, the hypothesis came to be seen even more controversial, due to the Altaic family itself also falling out universal acceptance. Today, the hypothesis that Uralic and Altaic are related more closely to one another than to any other family has almost no adherents.[16] There are, however, a number of hypotheses that propose a macrofamily including Uralic, Altaic and other families. None of these hypotheses has widespread support.

In his Altaic Etymological Dictionary, co-authored with Anna V. Dybo and Oleg A. Mudrak, Sergei Starostin characterized the Ural–Altaic hypothesis as "an idea now completely discarded".[16] In Starostin's sketch of a "Borean" super-phylum, he puts Uralic and Altaic as daughters of an ancestral language of ca. 9,000 years ago from which the Dravidian languages and the Paleo-Siberian languages, including Eskimo-Aleut, are also descended. He posits that this ancestral language, together with Indo-European and Kartvelian, descends from a "Eurasiatic" protolanguage some 12,000 years ago, which in turn would be descended from a "Borean" protolanguage via Nostratic.[17]

Angela Marcantonio (2002) argues that the Finno-Permic and Ugric languages are no more closely related to each other than either is to Turkic, thereby positing a grouping very similar to Ural–Altaic or indeed to Castrén's original Altaic proposal. This thesis has been criticized by mainstram Uralic scholars.[18][19][20]

Linguist Martine Robbeets exemplify that "The Ural-Altaic theory was rather widely accepted in the 19th century, but after the affinity of the Uralic languages was established, the Ural-Altaic theory lost many of its supporters. Although it is commonplace in contemporary linguistic literature to reject the Ural-Altaic theory as such, the debate on possible genetic links between well established families is more animated than ever before. It is in this light that attempts to establish Nostratic or Eurasianic can be seen."[21]

According to the linguist Juha Janhunen typological parallels among Uralic and Altaic languages are accompanied by areal adjacency, calling it "a distinct Ural-Altaic language area and language type" belonging to a "single trans-Eurasian belt of agglutinative languages" in which Turkic, Mongolic, Tungusic, Korean, and Japanese are included.[22]

Typology

There is general agreement on several typological similarities being widely found among the languages considered under Ural–Altaic:[23]

- head-final and subject–object–verb word order

- in most of the languages, vowel harmony

- morphology that is predominantly agglutinative and suffixing

- zero copula

- non-finite clauses

- lack of grammatical gender

- lack of consonant clusters in word-initial position

- lack of a separate verb for "to have"

Such similarities do not constitute sufficient evidence of genetic relationship all on their own, as other explanations are possible. Juha Janhunen has argued that although Ural–Altaic is to be rejected as a genealogical relationship, it remains a viable concept as a well-defined language area, which in his view has formed through the historical interaction and convergence of four core language families (Uralic, Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic), and their influence on the more marginal Korean and Japonic.[24]

Contrasting views on the typological situation have been presented by other researchers. Michael Fortescue has connected Uralic instead as a part of an Uralo-Siberian typological area (comprising Uralic, Yukaghir, Chukotko-Kamchatkan and Eskimo-Aleut), contrasting with a more narrowly defined Altaic typological area;[25] while Anderson has outlined a specifically Siberian language area, including within Uralic only the Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic groups; within Altaic most of the Tungusic family as well as Siberian Turkic and Buryat (Mongolic); as well as Yukaghir, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Eskimo-Aleut, Nivkh, and Yeniseian.[26]

Relationship between Uralic and Altaic

The Altaic language family was generally accepted by linguists from the late 19th century up to the 1960s, but since then has been in dispute. For simplicity's sake, the following discussion assumes the validity of the Altaic language family.

Two senses should be distinguished in which Uralic and Altaic might be related.

- Do Uralic and Altaic have a demonstrable genetic relationship?

- If they do have a demonstrable genetic relationship, do they form a valid linguistic taxon? For example, Germanic and Iranian have a genetic relationship via Proto-Indo-European, but they do not form a valid taxon within the Indo-European language family, whereas in contrast Iranian and Indo-Aryan do via Indo-Iranian, a daughter language of Proto-Indo-European that subsequently calved into Indo-Aryan and Iranian.

In other words, showing a genetic relationship does not suffice to establish a language family, such as the proposed Ural–Altaic family; it is also necessary to consider whether other languages from outside the proposed family might not be at least as closely related to the languages in that family as the latter are to each other. This distinction is often overlooked but is fundamental to the genetic classification of languages.[27] Some linguists indeed maintain that Uralic and Altaic are related through a larger family, such as Eurasiatic or Nostratic, within which Uralic and Altaic are no more closely related to each other than either is to any other member of the proposed family, for instance than Uralic or Altaic is to Indo-European (for example Greenberg).[28]

Evidence for a genetic relationship

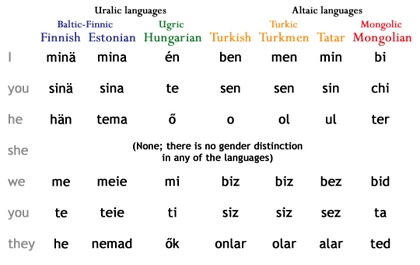

Some[who?] linguists point out strong similarities in the personal pronouns of Uralic and Altaic languages. Because pronouns are among the elements of language most resistant to change and it is very rare for one language to replace its pronouns wholesale with those of another, these similarities, if accepted as non-accidental, would be strong evidence for genetic relationship. It should be noted that the "s" in the Finnic second person pronoun *sinä is a result of a ti > si sound law [29] in Proto-Finnic, and comes from earlier form *tinä, as in the plural form te and the Hungarian pronoun te.

Vocabulary of common origin

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2008) |

To demonstrate the existence of a language family, it is necessary to find cognate words that trace back to a common proto-language. Shared vocabulary alone does not show a relationship, as it may be loaned from one language to another or through the language of a third party.

There are shared words between, for example, Turkic and Ugric languages, or Tungusic and Samoyedic languages, which are explainable by borrowing. However, it has been difficult to find Ural–Altaic words shared across all involved language families. Such words should be found in all branches of the Uralic and Altaic trees and should follow regular sound changes from the proto-language to known modern languages, and regular sound changes from Proto-Ural–Altaic to give Proto-Uralic and Proto-Altaic words should be found to demonstrate the existence of a Ural–Altaic vocabulary. Instead, candidates for Ural–Altaic cognate sets can typically be supported by only one of the Altaic subfamilies.[30] In contrast, about 200 Proto-Uralic word roots are known and universally accepted, and for the proto-languages of the Altaic subfamilies and the larger main groups of Uralic, on the order of 1000–2000 words can be recovered.

The basic numerals, unlike among the Indo-European languages (compare Proto-Indo-European numerals), are particularly divergent between all three core Altaic families and Uralic, and to a lesser extent even within Uralic.[31]

| Numeral | Uralic | Turkic | Mongolic | Tungusic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finnish | Hungarian | Tundra Nenets | Old Turkic | Classical Mongolian | Proto-Tungusic | |

| 1 | yksi | egy | ŋob | bir | nigen | *emün |

| 2 | kaksi | kettő/két | śiďa | iki | qoyar | *džör |

| 3 | kolme | három | ńax°r | üč | ɣurban | *ilam |

| 4 | neljä | négy | ťet° | tört | dörben | *dügün |

| 5 | viisi | öt | səmp°ľaŋk° | beš | tabun | *tuńga |

| 6 | kuusi | hat | mət°ʔ | altı | irɣuɣan | *ńöŋün |

| 7 | seitsemän | hét | śīʔw° | yeti | doluɣan | *nadan |

| 8 | kahdeksan | nyolc | śid°nťet° | säkiz | naiman | *džapkun |

| 9 | yhdeksän | kilenc | toquz | yisün | *xüyägün | |

| 10 | kymmenen | tíz | yūʔ | on | arban | *džuvan |

See also

- Altaic languages

- Indo-Uralic languages

- Nostratic languages

- Proto-Uralic language

- Uralic languages

- Uralic–Yukaghir languages

- Uralo-Siberian languages

References

- ^ Sinor 1988, p. 710.

- ^ George van DRIEM: Handbuch der Orientalistik. Volume 1 Part 10. BRILL 2001. Page 336

- ^ Colin Renfrew, Daniel Nettle: Nostratic: Examining a Linguistic Macrofamily - Page 207, Publisher: McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge(1999), ISBN 9781902937007

- ^ Robert Lawrence Trask: The Dictionary of Historical and Comparative Linguistics - PAGE: 357, Publisher: Psychology Press (2000), ISBN 9781579582180

- ^ Lars Johanson, Martine Irma Robbeets : Transeurasian Verbal Morphology in a Comparative Perspective: Genealogy, Contact, Chance -PAGE: 8. Publisher: Otto Harrassowitz Verlag (2010), ISBN 9783447059145

- ^ Ladislav Drozdík: Non-Finite Relativization. A Typological Study in Accessibility. Page 30 (XXX), Publisher: Ústav orientalistiky SAV, ISBN 9788080950668

- ^ Carl J. Becker: A Modern Theory of Language Evolution - Page 320, Publisher iUniverse (2004), ISBN 9780595327102

- ^ Bomhard, Allan R. (2008). Reconstructing Proto-Nostratic: Comparative Phonology, Morphology, and Vocabulary, 2 volumes. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-16853-4

- ^ W. Schott, Versuch über die tatarischen Sprachen (1836)

- ^ F. J. Wiedemann, Ueber die früheren Sitze der tschudischen Völker und ihre Sprachverwandschaft mit dem Völkern Mittelhochasiens (1838).

- ^ M. A. Castrén, Dissertatio Academica de affinitate declinationum in lingua Fennica, Esthonica et Lapponica, Helsingforsiae, 1839

- ^ M. A. Castrén, Nordische Reisen und Forschungen. V, St.-Petersburg, 1849

- ^ Sean P. HARVEY: Native Tounges: Colonialism and Race from Encounter to the Reservation. Harvard University Press 2015. Page 212

- ^ Sinor 1988, pp. 707–708.

- ^ Nicholas Poppe, The Uralo-Altaic Theory in the Light of the Soviet Linguistics Accessed 2010-04-07

- ^ a b (Starostin et al. 2003:8)

- ^ Sergei Starostin. "Borean tree diagram".

- ^ Linguistic Shadowboxing Accessed 2010-04-07

- ^ Edward J. Vajda, review of The Uralic language family: facts, myths, and statistics Accessed 2016-03-01

- ^ Václav Blažek, review of The Uralic language family: facts, myths, and statistics Accessed 2016-03-01

- ^ In: ROBBEETS, Martine Irma: Is Japanese Related to Korean, Tungusic, Mongolic and Turkic? 2005. p. 18-19.

- ^ Proto-Uralic—what, where, and when? Juha JANHUNEN (Helsinki) The Quasquicentennial of the Finno-Ugrian Society. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia = Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 258. Helsinki 2009. 61–62.

- ^ Sinor 1988, pp. 711–714.

- ^ Janhunen, Juha (2007). "Typological Expansion in the Ural-Altaic belt". Incontri Linguistici: 71–83.

- ^ Fortescue, Michael (1998). Language Relations across Bering Strait: Reappraising the Archaeological and Linguistic Evidence. London and New York: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-70330-3.

- ^ Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2006). "Towards a typology of the Siberian linguistic area". In Matras, Y.; McMahon, A.; Vincent, N. (eds.). Linguistic Areas. Convergence in Historical and Typological Perspective. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 266–300.

- ^ Greenberg 2005

- ^ Greenberg 2000:17

- ^ http://www.reference-global.com/doi/abs/10.1515/flih.1986.7.1.81. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

{{cite web}}:|archive-date=requires|archive-url=(help); Missing or empty|title=(help); Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Sinor 1988, p. 736.

- ^ Sinor 1988, pp. 710–711.

Bibliography

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (2000). Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, Volume 1: Grammar. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Greenberg, Joseph H. (2005). Genetic Linguistics: Essays on Theory and Method, edited by William Croft. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Marcantonio, Angela (2002). The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics. Publications of the Philological Society. Vol. 35. Oxford – Boston: Blackwell.

- Shirokogoroff, S. M. (1931). Ethnological and Linguistical Aspects of the Ural–Altaic Hypothesis. Peiping, China: The Commercial Press.

- Sinor, Denis (1988). "The Problem of the Ural-Altaic relationship". In Sinor, Denis (ed.). The Uralic Languages: Description, History and Modern Influences. Leiden: Brill. pp. 706–741.

- Starostin, Sergei A., Anna V. Dybo, and Oleg A. Mudrak. (2003). Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-13153-1.

- Vago, R. M. (1972). Abstract Vowel Harmony Systems in Uralic and Altaic Languages. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

External links

- "The 'Ugric-Turkic battle': a critical review" by Angela Marcantonio, Pirjo Nummenaho, and Michela Salvagni (2001)

- Review of Marcantonio (2002) by Johanna Laasko

- Keane, Augustus Henry (1911). "Ural-Altaic". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). pp. 784–6. This reflects the contemporary transitional state of understanding of the relationships among the languages.

- Whitney, William Dwight; Rhyn, G. A. F. Van (1879). . The American Cyclopædia.