Venezuelan bolívar

| bolívar soberano venezolano (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| File:BsS.jpg Banknotes and coins of the bolívar soberano up to Bs. 500 | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | VES (numeric: 928) |

| Subunit | 0.01 |

| Unit | |

| Plural | bolívares soberanos |

| Symbol | Bs.S.[1] or Bs. |

| Nickname | bolo(s), luca(s), real(es) |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | céntimo |

| Banknotes | Bs.S. 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200, 500,[1] 10,000, 20,000, 50,000 |

| Coins | 50 céntimos, Bs.S. 1 |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Banco Central de Venezuela |

| Website | www |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | |

| Value | Official rate US$1 = Bs.S 125975 (April 16, 2020)[1] Parallel rate US$1 = Bs.S 134805 (April 16, 2020)[3] |

The main currency of Venezuela since 20 August 2018 has been the bolívar soberano (sovereign bolivar) (sign: Bs.S.[1] or Bs.;[4] plural: bolívares soberanos; ISO 4217 code: VES).

It will replace the bolívar fuerte (strong bolívar, sign: Bs.F., ISO 4217 code: VEF) after a transition period.[5] The primary reason for replacement, at a rate of 1 Bs.S. to 100,000 Bs.F, was hyperinflation.[citation needed]

On 1 January 2008, the bolívar fuerte had itself replaced, because of inflation,[6] the original bolívar introduced in 1879 (sign: Bs.;[1] ISO 4217 code: VEB). It did so at a rate of 1 Bs.F. to 1000 Bs.

History

Bolívar

| Preceded by: Venezolano Reason: unification of circulating currencies Ratio: 1⁄5 venezolano = 1 bolívar |

Currency of Venezuela 31 March 1879 – 31 December 2007 |

Succeeded by: Bolívar fuerte Reason: inflation Ratio: 1000 bolívares = 1 bolívar fuerte |

| bolívar (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | VEB |

| Unit | |

| Plural | bolívares |

| Symbol | Bs. |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | céntimo |

| Plural | |

| céntimo | céntimos |

| Banknotes | 2000, 5000, 10,000, 20,000, 50,000 bolívares |

| Coins | 10, 20, 50, 100, 500, 1000 bolívares |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Banco Central de Venezuela |

| Website | www |

The Bolívar is named after the hero of Latin American independence Simón Bolívar. The bolívar was adopted by the monetary law of 1879, replacing the short-lived venezolano at a rate of five bolívares to one venezolano. Initially, the bolívar was defined on the silver standard, equal to 4.5 g fine silver, following the principles of the Latin Monetary Union. The monetary law of 1887 made the gold bolívar unlimited legal tender, and the gold standard came into full operation in 1910. Venezuela went off gold in 1930, and in 1934, the bolívar exchange rate was fixed in terms of the U.S. dollar at a rate of 3.914 bolívares = 1 U.S. dollar, revalued to 3.18 bolívares = 1 U.S. dollar in 1937, a rate which lasted until 1941. Until 18 February 1983 (now called Black Friday (Viernes Negro) by many Venezuelans),[7] the bolívar had been the region's most stable and internationally accepted currency. It then fell prey to high devaluation.

Exchange controls were imposed on February 5, 2003, to limit capital flight.[8] The rate was pegged to the U.S. dollar at a fixed exchange rate of Bs 1,600 to the dollar.

Bolívar fuerte

| Preceded by: Bolívar Reason: inflation Ratio: 1000 bolívares = 1 bolívar fuerte |

Currency of Venezuela 1 January 2008 – 20 August 2018 |

Succeeded by: Bolívar soberano Reason: hyperinflation Ratio: 100,000 bolívares fuertes = 1 bolívar soberano |

| bolívar fuerte venezolano (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| File:Bolívar fuerte notes.jpg Various 2007–2015 series bolívar fuerte notes | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | VEF |

| Unit | |

| Plural | bolívares fuertes |

| Symbol | Bs.F.[1] or Bs. |

| Nickname | bolo(s), luca(s), real(es) |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | céntimo |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | Bs.F. 1000, 2000, 5000, 10,000, 20,000, 100,000[1] |

| Rarely used | Bs.F. 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 |

| Coins | |

| Rarely used | Bs.F. 1, 10, 50, and 100[1] |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) | |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Banco Central de Venezuela |

| Website | www |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | |

| Pegged with | US$1 = Bs. 248,832 (Dicom auction)[1] (see this section for parallel market rate)[10] |

Coins and low-value banknotes were rendered obsolete by hyperinflation. | |

The government announced on 7 March 2007 that the bolívar would be revalued at a ratio of 1,000 to 1 on 1 January 2008 and renamed the bolívar fuerte in an effort to facilitate the ease of transaction and accounting.[11] The newer name is literally translated as "strong bolívar"[12][13] but is also a reference to an old coin called the peso fuerte worth 10 Spanish reales.[14] The name "bolívar fuerte" is used to distinguish it from the older currency that was being used along with the bolívar fuerte.[15][original research?] The official exchange rate is restricted to individuals by CADIVI, which imposes an annual limit on the amount available for travel.

Since the government of Hugo Chávez established strict currency controls in 2003, there have been a series of five currency devaluations, disrupting the economy.[16] On 8 January 2010, the value was changed by the government from the fixed exchange rate of 2.15 bolívares fuertes to 2.60 bolívares for some imports (certain foods and healthcare goods) and 4.30 bolívares for other imports like cars, petrochemicals, and electronics.[17] On 4 January 2011, the fixed exchange rate became 4.30 bolívares for US$1.00 for both sides of the economy. On 13 February 2013 the bolívar fuerte was devalued to 6.30 bolívares per US$1 in an attempt to counter budget deficits.[18] On 18 February 2016, President Maduro used his newly granted economic powers to devalue the official exchange rate of the bolívar fuerte from 6.3 Bs.F per US$1 to 10 Bs.F per US$1, which is a 37% depreciation against the U.S. dollar.[19]

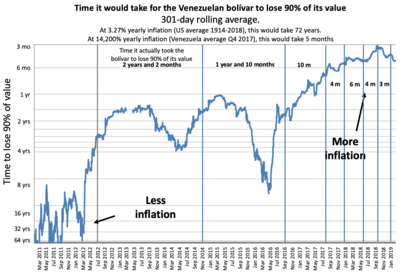

The bolívar fuerte entered hyperinflation in November 2016.[20]

On January 26, 2018, the government retired the protected and subsidized 10 Bs.F per US$1 exchange rate that was highly overvalued as a result of rampant inflation.[21] On February 5, 2018, the Central Bank of Venezuela announced a 99.6% [sic] devaluation, with the exchange rate going to 25,000 Bs.F per USD. This made the bolívar fuerte the second-least valued circulating currency in the world based on the official exchange rate, behind only the Iranian rial, and between September 2017 and August 2018, according to the informal exchange rate, the bolívar fuerte was the least valued circulating currency unit in the world.[22][dubious – discuss]

The official exchange rate stood at 248,832 VEF/USD as of August 10, 2018, making it the least valued circulating currency in the world based on official exchange rates.[23]

In June 2018, the government authorized a new exchange rate for buying, but not selling currency. On August 13, 2018, the rate was 4,010,000 VEF/USD according to ZOOM Remesas.[24]

Bolívar soberano

| Preceded by: Bolívar fuerte Reason: hyperinflation Ratio: 100,000 bolívares fuertes = 1 bolívar soberano |

Currency of Venezuela 20 August 2018 – 2020 |

On 22 March 2018, President Nicolás Maduro announced a new monetary reform program, with a planned revaluation of the currency at a ratio of 1 to 1,000.[25] The change was to be made effective from 4 June 2018.[26][27]

In May 2018, the government required prices to be expressed in both bolívares fuertes and bolívares soberanos at the then-planned rate of 1,000 to 1. For example, one kilogram of pasta was shown with a price of BsF. 695,000 and BsS. 695. Prices expressed in the new currency were rounded to the nearest 50 céntimos as that was expected to be the lowest denomination in circulation at launch. The rounding created difficulties because some items and sales qualities were priced at significantly less than 0.50 BsS.; for example a litre of gasoline and a Caracas Metro ticket typically cost BsS. 0.06 and BsS. 0.04, respectively.[28]

The change in currency was originally scheduled for June 4, 2018. The President delayed the planned June launch date of the bolívar soberano, citing from Aristides Maza, "the period established to carry out the conversion is not enough".[29] The revaluation was rescheduled to 20 August 2018, and the rate changed to 100,000 to 1, with prices being required to be expressed at the new rate starting 1 August 2018.[30]

On 20 August 2018, the Maduro government launched the new bolívar soberano currency,[31] with one bolívar soberano worth 100,000 bolívares fuertes. New coins in denominations of 50 céntimos and 1 bolívar soberano, and new banknotes in denominations of 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 200 and 500 bolívares soberanos were introduced.[32] Under the country's official fixed exchange rate to the US dollar the new currency was devalued by roughly 95% compared to the old bolívar fuerte.[33] The day was declared a bank holiday to allow the banks to adjust to the new currency.[34] Initially, during a transition period the bolívar soberano was to be run alongside the bolívar fuerte.[5] However, from the start of the transition, on 20 August, bolívar fuerte notes of 500 and less could not be used; only deposited at banks.[35]

Concurrently with the release of the new currency, the minimum wage was raised to 1,800 bolívares soberanos per month,[36] a 33-fold increase,[37] and sales tax increased from 12% to 16%.[37]

Additionally, the bolívar soberano is supposed to have a fixed exchange rate to the petro cryptocurrency, with a rate of 3,600 bolívares soberanos to one petro;[38][39] a peg of petro and bolívar soberano was announced by Maduro as early as 15 August.[citation needed] The petro is supposedly tied to the price of a barrel of oil (about US$60 in August 2018).[38][39] As of the end of August 2018, there is no evidence that the cryptocurrency is being traded.[40] Petro is regarded by many as a scam.[41][40][42]

Following the introduction of the bolívar soberano, inflation increased from 61,463 percent on 21 August 2018 to 65,320 percent on 22 August 2018.[41] By 24 August 2018, the introduction of the bolívar soberano had not prevented hyperinflation.[43] According to inflation analyst Steve Hanke, between 18 August and 21 August 2018, the inflation rate increased from 48,760 percent to 65,320 percent.[20][41]

On 22 August, DolarToday estimated the free market exchange rate at 71.2 bolívares soberanos per US dollar.[3] AirTM's reported exchange rate was 75.6 VES/USD.[44][45]

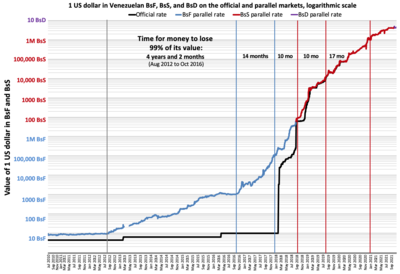

Currency black market

The black (or parallel) market value of the bolívar fuerte and the bolívar soberano has been significantly lower than the fixed exchange rate and other rates set by the Venezuelan government (SICAD, SIMADI, DICOM). In November 2013, it was almost one-tenth that of the official fixed exchange rate of 6.3 bolívares per U.S. dollar.[46] In September 2014, the currency black market rate for the bolívar fuerte reached 100 VEF/USD;[47] on 25 February 2015, it went over 200 VEF/USD.[48] on 7 May 2015, it was over 275 VEF/USD and on 22 September 2015, it was over 730 VEF/USD.[49] Venezuela still had the highest inflation rate in the world in July 2015.[50] By 3 February 2016, this rate reached 1,000 VEF/USD. This rate surpassed 4,300 VEF/USD on 10 December 2016. It surpassed 10,000 VEF/USD on 28 July 2017, and on 7 September 2017, the rate surpassed 20,000 VEF/USD for the first time. Inflation accelerated, and on 1 December 2017, it reached 100,000 VEF/USD for the first time ever. The rate surpassed 200,000 VEF/USD on 18 January 2018, then 500,000 VEF/USD on 16 April, 1 million VEF/USD on 30 May, 2 million VEF/USD on 7 June, and 5 million VEF/USD on 16 August.[3]

At the time of redomination on 20 August 2018, the exchange rate was 59.21 VES/USD. By the end of the month it reached 87 VES/USD. The rate then surpassed 100 VES/USD on 3 October 2018, 1,000 VES/USD on 9 January 2019, 10,000 VES/USD on 19 July, and 50,000 VES/USD on 29 December. According to DolarToday, the parallel exchange rate was 54,702.82 VES/USD as of 1 January 2020.[3]

It is illegal to publish the "parallel exchange rate" in Venezuela.[51] One popular website that has been publishing parallel exchange rates since 2010 is DolarToday, which has also been critical of the Maduro government.[52]

Exchange rate history

This table shows a condensed history of the parallel foreign exchange rate of the Venezuelan bolívar to one United States dollar between 2012 and 2020, according to DolarToday.[53]

| Bolívar fuerte (Bs.F) 1 Bs.F = 1,000 Bs. |

Bolívar soberano (Bs.S) 1 Bs.S = 100,000 Bs.F | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coins

Bolívar

In 1879, silver coins were introduced in denominations of 1⁄5, 1⁄2, 1, 2, and 5 bolívares, together with gold 20 bolívares. Gold 100 bolívares were also issued between 1886 and 1889. In 1894, silver 1⁄4 bolívar coins were introduced, followed by cupro-nickel 5 and 12+1⁄2 céntimos in 1896.

In 1912, production of gold coins ceased, whilst production of the 5 bolívares ended in 1936. In 1965, nickel replaced silver in the 25 and 50 céntimos, with the same happening to the 1 and 2 bolívares in 1967. In 1971, cupro-nickel 10 céntimo coins were issued, the 12+1⁄2 céntimos having last been issued in 1958. A nickel 5 bolívares was introduced in 1973. Clad steel (first copper, then nickel and cupro-nickel) was used for the 5 céntimos from 1974. Nickel clad steel was introduced for all denominations from 25 céntimos up to 5 bolívares in 1989.

In 1998, after a period of high inflation, a new coinage was introduced consisting of 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 bolívares denominations.

The former coins were:

- 10 bolívares

- 20 bolívares

- 50 bolívares

- 100 bolívares

- 500 bolívares

- 1000 bolívares (minted 2005, issued late 2006, incorrectly rumoured as recalled due to official Coat of Arms change during the interval)[54]

All the coins had the same design. On the obverse the left profile of the Libertador Simón Bolívar is depicted, along with the inscription "Bolívar Libertador" within a heptagon, symbolizing the seven stars of the flag. On the reverse the coat of arms is depicted, circled by the official name of the country, with the date and the denomination below. In 2001, the reverse design was changed, putting the denomination of the coin at the right of the shield of the coat of arms, Semi-Circled by the official name of the country and the year of its emission below.

Bolívar fuerte

Coins of the bolívar fuerte were in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 12+1⁄2, 25, 50 céntimos, and 1 bolívar. They were quickly rendered obsolete by high inflation. It may be noticed that there was a 12+1⁄2-céntimo coin and a 1-céntimo coin, but no 1⁄2-céntimo coin. Therefore, giving correct change for a purchase of, say, 4+1⁄2 céntimos would require using a 12+1⁄2-céntimo coin and getting 8 céntimos back.

| 2008 Series | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Shape | Composition | Weight | Diameter | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | Obverse image | Reverse image |

| 1 céntimo | Round | Copper-plated steel | 1.36 g | 15 mm | Reeded | Denomination of the coin, the eight stars and waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

| 5 céntimos | Round | Copper-plated steel | 2.03 g | 17 mm | Plain | Denomination of the coin, the eight stars and waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

| 10 céntimos | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 2.62 g | 18 mm | Reeded | Denomination of the coin, the eight stars and waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

| 12+1⁄2 céntimos | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 3.93 g | 23 mm | Plain | Denomination of the coin, the eight stars of the national flag and two palm branches | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

| 25 céntimos | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 3.86 g | 20 mm | Plain | Denomination of the coin, the eight stars and waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

| 50 céntimos | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 4.3 g | 22 mm | Segmented (Plain and Reeded edges) | Denomination of the coin, the eight stars and waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

| Bs. 1 | Round | Copper-Nickel center, Brass ring | 8.04 g | 24 mm | Smooth 'BCV1' | Effigy of the Liberator Simón Bolívar, waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Denomination of the coin, the eight stars and the waves representing the patterns of the national flag, the Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

In December 2016, it was announced that coins of 10, 50, and 100 bolívares would enter circulation. These three coins would replace the banknotes of the same denominations.[55]

| 2016 Series | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Shape | Composition | Weight | Diameter | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | Obverse & Reverse image |

| 10 bolívares | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 3.5 g | 21.3 mm | Smooth | Effigy of the Liberator Simón Bolívar, waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |

|

| 50 bolívares | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 5.3 g | 23.5 mm | Smooth | Effigy of the Liberator Simón Bolívar, waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |

|

| 100 bolívares | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 6.5 g | 25.5 mm | Segmented (Plain and Reeded edges) | Effigy of the Liberator Simón Bolívar, waves representing the patterns of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela and the name of the country of emission |

|

Bolívar soberano

Bolívar soberano coins were announced to be produced in denominations of 50 céntimos and 1 bolívar (50,000 bolívares fuertes and 100,000 bolívares fuertes). These two coins are worthless by Sept 2019.

| 2018 Series | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Shape | Composition | Diameter | Edge | Obverse | Reverse | Obverse image | Reverse image |

| 50 céntimos | Round | Nickel-plated steel | 22 mm | Decorated | Effigy of the Liberator Simón Bolívar, the eight stars of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela, waves representing the patterns of the national flag and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

| 1 bolívar | Round | Copper-Nickel center, Brass ring | 24 mm | - | Effigy of the Liberator Simón Bolívar, the eight stars of the national flag | Coat of Arms of Venezuela, waves representing the patterns of the national flag and the name of the country of emission |  |

|

Banknotes

Bolívar

In 1940, the Banco Central de Venezuela began issuing paper money, introducing by 1945 denominations of 10, 20, 50, 100 and 500 bolívares. 5-bolívar notes were issued between 1966 and 1974, when they were replaced by coins. In 1989, notes for 1, 2 and 5 bolívares were issued.

As inflation took hold, higher denominations of banknotes started being introduced: 1,000 bolívares in 1991, 2,000 and 5,000 bolívares in 1994, and 10,000, 20,000 and 50,000 bolívares in 1998. The first 20,000-bolívar banknotes were made in a green color similar to the one of the 2,000 banknotes, which caused confusion, and new banknotes were made in the new olive green color.

Starting from 2000, banknotes ranging from 5,000 bolívares to 50,000 bolívares were renamed to REPÚBLICA BOLIVARIANA DE VENEZUELA instead of BANCO CENTRAL DE VENEZUELA on the front, after the 1999 constitution was adopted. Moreover, banknotes of 10,000, 20,000 and 50,000 bolívares were updated in April 2006 after the National Assembly approved changes to the coat of arms, which were made official on March 12, 2006.

The following is a list of former Venezuelan bolívar banknotes:

| Pre-1998 series banknotes (from various series) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Denomination | Emission Year | Obverse | Reverse | |

| 5 bolívares | 1968 | Simón Bolívar and Francisco de Miranda | National Pantheon of Venezuela | ||

| 10 bolívares | 1968 | Simón Bolívar and Mariscal Sucre | Altar de la Patria, Campo de Carabobo | ||

| 20 bolívares | 1971 | Jose Antonio Paez | Altar de la Patria, Campo de Carabobo | ||

| 50 bolívares | 1971 | Andrés Bello | Palace of the Academies | ||

| 100 bolívares | 1971 | Simón Bolívar | Federal Legislative Palace | ||

| 500 bolívares | 1981 | Simón Bolívar | A branch of orchids | ||

| 1,000 bolívares | 1991 | Simón Bolívar | Signing of the Venezuelan Declaration of Independence | ||

| 2,000 bolívares | 1994 | Antonio José de Sucre | The Battle of Junín | ||

| 5,000 bolívares | 1994 | Simón Bolívar and his coat of arms | A reproduction of the painting El 19 de Abril de 1810 by Juan Lovera | ||

| 1998 Series | |||||

| [1] | [2] | 1,000 bolívares | 1998 | Simón Bolívar | A picture of National Pantheon in Caracas |

| [3] | [4] | 2,000 bolívares | 1998 | Andrés Bello | A picture of frailejones and a view of the Pico Bolívar |

| [5] | [6] | 10,000 bolívares | 1998 | Simón Bolívar | Teresa Carreño Cultural Complex, Caracas |

| [7] | [8] | 20,000 bolívares | 1998 | Simón Rodríguez and the Angel Falls in the background | A blue-and-yellow macaw and the Angel Falls |

| [9] | [10] | 50,000 bolívares | 1998 | José María Vargas | Central University of Venezuela, Caracas |

| 2000-2006 Series "REPÚBLICA BOLIVARIANA DE VENEZUELA" | |||||

| [11] | [12] | 5,000 bolívares | 2000 | Francisco de Miranda | Picture of two angelfishes and a panorama of the Guri Dam. |

| [13] | [14] | 10,000 bolívares | 2000 | Antonio José de Sucre | A Marpesia petreus butterfly and the Supreme Tribunal of Justice |

| [15] | [16] | 20,000 bolívares | 2001 | Simón Rodríguez and the Angel Falls in the background | A blue-and-yellow macaw and the Angel Falls |

| [17] | [18] | 50,000 bolívares | 2005 | José María Vargas | Central University of Venezuela, Caracas |

Bolívar fuerte

2008–2016 ("2007")

New banknotes of the series 2007–2015 with values of 2 to 100 BsF were issued from 20 March 2007 until 5 November 2015 and became legal tender from 1 January 2008 to 20 August 2018. The greater the values, the longer re-issuing occurred. Only the 50 and 100 BsF notes were re-issued in November 2015.

- 2 BsF: March 20, 2007 to October 29, 2013

- 5 BsF: March 20, 2007 to August 19, 2014

- 10 BsF: March 20, 2007 to August 19, 2014

- 20 BsF: March 20, 2007 to August 19, 2014

- 50 BsF: March 20, 2007 to November 5, 2015[56]

- 100 BsF: March 20, 2007 to November 5, 2015[56]

The obverse side is portrait-oriented, with the lower half carrying a portrait, while the reverse side is landscape-oriented, the left two thirds showing an animal in front of its habitat.

Re-issues retain the value-specific motifs, but the printing quality is different. The notes are printed by Casa de la Moneda Venezuela in Venezuela.[56]

2016–17

High inflation, which was a part of Venezuela's economic collapse, caused the bolívar fuerte's value to plummet. The 2- and 5-bolívar notes were no longer found in circulation due to the hyperinflation, but remained legal tender. By December 2016, the 100-bolívar note, Venezuela's largest denomination of currency, was only worth about US$0.23 on the black market.[57]

On 7 December 2016, a new series of banknotes (recolors of the previous notes) in denominations of 500, 1,000, 2,000, 5,000, 10,000, and 20,000 bolívares fuertes was unveiled to the Venezuelan public.[55][57] Days later on 11 December, President Nicolás Maduro who had been ruling by decree wrote into law that the 100 Bs.F. would be pulled from circulation within 72 hours because "mafias" were allegedly storing those particular bills to drive inflation.[58] With more than 6 billion 100 Bs.F. notes issued consisting of 46% of Venezuela's issued currency, Maduro enacted an exchange for Venezuelan citizens to transfer all 100 Bs.F. notes for 100 Bs.F. coins while also blocking international travel to prevent the return of the bolívares that were supposedly stockpiled.[58][59] The government justified the move claiming that the United States was working with crime syndicates to spirit away Venezuela's paper money to warehouses in Europe to cause the fall of the government. The government was thwarting this threat by withdrawing the notes from circulation.[60] On 14 February 2017, Paraguayan authorities uncovered a 30-tonne stash of 50- and 100-bolívar notes totaling 1.5 billion Bs.F on its Brazilian border that had not yet been circulated.[61] According to a United States Department of Defense adviser linked to The Pentagon, the 1.5 billion Bs.F was printed by Venezuela and destined for Bolivia, since unlike the implied exchange rate of thousands of bolívares fuertes equaling one United States dollar, the exchange rate was approximately 10 bolívares fuertes per dollar, making the value of the stash 419 times stronger, from US$358,000 to US$150 million.[61] The Pentagon adviser further stated that the Venezuelan government tried to send the newly printed notes to be exchanged by the Bolivian government so Bolivia could pay 20% of its debt to Venezuela, and so Venezuela could use the US dollars for its own disposal.[61]

On November 3, 2017, the Banco Central de Venezuela issued a 100,000-bolívar note which is similar to the 100-bolívar note of the 2007 series and the 20,000-bolívar of the 2016 series, but with the denomination spelled out in full instead of adding an additional three zeros to the number 100. This denomination was worth US$2.42 using the unofficial exchange rate at the date of its release.

New banknotes of the 2016–17 series with values of 500 to 100,000 BsF were issued from 7 December 2016 until 20 August 2018, the day when the bolívar soberano was introduced. Notes from 5,000 BsF to 100,000 BsF were recently re-issued in December 2017.

- 500 BsF: August 18, 2016 to March 23, 2017

- 1,000 BsF: August 18, 2016 to March 23, 2017

- 2,000 BsF: August 18, 2016

- 5,000 BsF: August 18, 2016 to December 13, 2017

- 10,000 BsF: August 18, 2016 to December 13, 2017

- 20,000 BsF: August 18, 2016 to December 13, 2017

- 100,000 BsF: September 7, 2017 to December 13, 2017

Maduro has announced that after the currency redenomination has carried out on 20 August 2018, these old denominations with a face value of 1,000 bolívares fuertes or higher will circulate in parallel with the new series of bolívar soberano notes and will continue to be used for a limited time.[62] Banknotes with a face value below 1000 bolívares fuertes were withdrawn from circulation and ceased to be legal tender on 20 August 2018. They have to be deposited in local banks.[63][64]

2018

By May 2018, the bolívar fuerte's banknotes represented very little value and they had become in short supply.[65] Weighing scales could no longer convert mass to price and receipts could no longer fit the numbers on their paper.[66]

On June 2018, seven months after its release, the value of the 100,000-bolívar note (largest denomination), had its value reduced by 98%, from US$2.42 (in November 2017) to US$0.05, as a result of increasing hyperinflation.

The lower denomination bolívar fuerte banknotes (up to Bs.F 500) were demonetized on 20 August 2018; with the introduction of the bolívar soberano. Higher denominations (Bs. 1,000 and above) remained legal tender during a transition period. On 30 November 2018, it was announced that the remaining denominations of the old currency will be withdrawn from circulation and cease to be legal tender on 5 December 2018.[67]

Bolívar soberano

2018–19 ("2018")

The bolívar soberano banknotes were introduced to the public on 20 August 2018 in denominations of BsS 2, BsS 5, BsS 10, BsS 20, BsS 50, BsS 100, BsS 200 and BsS 500. Only the 50 BsS, 100 BsS and 500 BsS were recently reissued on May 18, 2018.

- 2 BsS: January 15, 2018

- 5 BsS: January 15, 2018

- 10 BsS: January 15, 2018

- 20 BsS: January 15, 2018

- 50 BsS: January 15, 2018 to May 18, 2018

- 100 BsS: January 15, 2018 to May 18, 2018

- 200 BsS: January 15, 2018 to March 13, 2018

- 500 BsS: January 15, 2018 to May 18, 2018

Four months after entry into circulation, the Bs.S 2 (about US$0.002 at that time), began being refused in shops and state banks, as its value has significantly declined since redenomination.[68][69]

By Dec.2019. Of all soberono Bolivar notes issued on 20 August 2018. Only the highest denomination 500 Bolivar notes are still in use. All other denomination are deemed worthless and the shops don't accept them

2019

Further inflation since redenomination has resulted in the entry of BsS 10,000, BsS 20,000 and BsS 50,000 banknotes into circulation effective 13 June 2019.[70] The Central Bank of Venezuela said in a statement that the introduction of the new banknotes will "make the payment system more efficient and facilitate commercial transactions."[71]

The highest denomination banknote (BsS 50,000) is worth US$0.50 as of 10 April 2020 on the black market and the minimum wage is BsS 250,000 (~US$2.50) per month. All bolivar soberano banknotes issued on Aug 2018 are useless by April 2020. On 23rd April 2020, the exchange rate per xe.com was 1 USD = 144,697.34 bolivares soberanos; the following day the rate slid to 1 USD = 171,140.42 VES.

- 10,000 BsS: January 22, 2019

- 20,000 BsS: January 22, 2019

- 50,000 BsS: January 22, 2019

| 2019 Series | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image | Denomination | Emission Year | Obverse | Reverse | |

| [19] | [20] | 10,000 bolívares | 2019 | Simón Bolívar | "Mausoleum of the Liberator" Simón Bolívar |

| [21] | [22] | 20,000 bolívares | 2019 | Simón Bolívar | "Mausoleum of the Liberator" Simón Bolívar |

| [23] | [24] | 50,000 bolívares | 2019 | Simón Bolívar | "Mausoleum of the Liberator" Simón Bolívar |

| Current VES exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR |

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Banco Central de Venezuela". bcv.org.ve (in Spanish).

- ^ "Inflación de 2018 cerró en 1.698.488%, según la Asamblea Nacional" (in Spanish). Efecto Cocuyo. 9 January 2019. Retrieved 9 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d "Indicadores Economía Venezolana". dolartoday.com (in Spanish).

- ^ La idea de Bolívar El Diario, 18 Diciembre 2013

- ^ a b "Venezuela rolls out new currency amid rampant hyperinflation". Al Jazeera. 20 August 2018. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Venezuela Introduces New Currency". Gata. 2008-01-01. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ^ "The weakening of the "strong bolívar"". The Economist. 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-04-09. Retrieved 2011-04-09.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Asamblea Nacional". República Bolivariana de Venezuela (in Spanish). Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Calculadora Dolar Today". Dolar Today. May 8, 2018.

- ^ "Currency of Venezuela – Venezuela's new currency the Venezuelan Bolívar fuerte". Republica-de-venezuela.com. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- ^ television advertisements Bolivar Fuerte Bs.F for the new currency repeatedly use "fuerte" as meaning "strong" such as in "Una economía fuerte" (a strong economy) and "¡Aquí hay fuerza!" (There's strength in this!)

- ^ Rueda, Jorge (2008-01-01). "Venezuela cuts three zeros off bolivar currency". Reuters. Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ^ Numismatic Catalog of Venezuela. "Coins in Pesos Fuerte". Retrieved 2008-02-04.

- ^ "Chavez Passes Law-Decree on Monetary Reform in Venezuela". venezuelanalysis.com. 9 March 2007. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- ^ Mander, Benedict (10 February 2013). "Venezuelan devaluation sparks panic". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ "Venezuela will slash value of currency, the bolivar". BBC. 2010-01-09. Retrieved 2010-01-09.

- ^ "Chavez Devaluation Puts Venezuelans to Queue on Price Raise". Bloomberg. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ^ Holodny, Elena (18 February 2016). "Venezuela raises gas prices 6,200%". Business Insider. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- ^ a b Hanke, Steve (18 August 2018). "Venezuela's Great Bolivar Scam, Nothing but a Face Lift". Forbes. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ "Venezuela eliminates heavily subsidized DIPRO forex rate". Reuters. 30 Jan 2018. Retrieved 2018-01-30.

- ^ "Venezuela announces 99.6 percent devaluation of official forex rate". Reuters. 5 February 2018. Retrieved 20 August 2018.

- ^ http://bcv.org.ve/

- ^ "Casa de Cambio ZOOM". Retrieved 2018-06-23.

- ^ López, Abel (2018-03-22). "Maduro anuncia nueva reconversión monetaria". El Nacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ "Venezuela to revalue ailing bolivar currency from June 4". Nasdaq. 2018-03-22. Archived from the original on 2018-03-23. Retrieved 2018-03-22.

- ^ "Ya está en Gaceta Oficial decreto de reconversión monetaria". Panorama (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-03-26.

- ^ Web, El Nacional (2018-04-29). "Comenzaron a aparecer productos con precios el bolívares soberanos". El Nacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-04-30.

- ^ WEB, EL NACIONAL (2018-05-29). "Maduro pospone entrada en vigencia de la reconversión monetaria". El Nacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-05-29.

- ^ "Inflation-hit Venezuela to remove five zeros from currency". Deutsche Welle. 26 July 2018. Retrieved 2018-07-26.

- ^ "With 1,000,000% inflation, Venezuela slashes five zeroes from its bills". Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Litzmayer, Owen (5 Apr 2018). "Venezuela | Banknote News". www.banknotenews.com. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

- ^ Hopps, Kat (21 August 2018). "Venezuela crisis: How much is the bolivar worth today? Bs to USD to GBP". Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ Sterling, Joe (2018-08-23). "Venezuela issues new currency, amid hyperinflation and social turmoil". CNN. Retrieved 2018-08-23.

- ^ https://mriguide.com/venezuela-bolivar-soberano-transition/

- ^ Venezuela just devalued the bolivar by 95% and pegged it to a cryptocurrency - Business Insider

- ^ a b "Venezuela hikes wages ahead of monetary overhaul". Washington Post. 2018-08-17. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- ^ a b Lam, Eric (20 August 2018). "Here's What Maduro Has Said of Venezuela's Petro Cryptocurrency". Bloomberg News.

- ^ a b Phillips, Tom (20 August 2018). "Venezuela devalues currency and raises minimum wage by 3,000%". the Guardian. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ a b Ellsworth, Brian (30 August 2018). "Special Report: In Venezuela, new cryptocurrency is nowhere to be found". Reuters. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Mak, Aaron (22 August 2018). "Venezuela Is About to Become the First Country to Peg Its Currency to a Cryptocurrency. Don't Believe the Hype". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Moskvitch, Katia (22 August 2018). "Inside the bluster and lies of Petro, Venezuela's cryptocurrency scam". Wired. Retrieved 11 October 2018.

- ^ "Venezuela: New currency fails to curb hyperinflation". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 2018-08-24.

- ^ "AirTM (@theairtm) - Twitter". twitter.com. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ "Venezuela's Currency Is Doing Even Worse Than Previously Thought". Bloomberg.com. 2018-04-04. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

- ^ "Stuck in Venezuela with those currency exchange blues". Los Angeles Times. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ "Venezuela bolivar hits record low 100/U.S. dollar on black market". Reuters. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- ^ "Venezuela's bolívar tumbles beyond 200 mark". Financial Times. 25 February 2015. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ^ "El precio 'REAL' del Dolar paralelo en Venezuela". DolarToday.com. 15 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 February 2013.

- ^ Pardo, Daniel (8 July 2015). "Living with Venezuela's high inflation". BBC News. UK. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- ^ Simon Romero (February 9, 2008). "In Venezuela, Faith in Chávez Starts to Wane". New York Times.

- ^ Otis, John. "Venezuela forces ISPs to police Internet". Committee to Protect Journalists. Retrieved May 15, 2015.

- ^ https://dxj1e0bbbefdtsyig.woldrssl.net/custom/dolartoday.xlsx

- ^ "Coins from Venezuela : 1000 Bolívares – Design B, Type A : Numismatic Catalog of Venezuela". www.numismatica.info.ve. 2016-12-04. Retrieved 2016-12-10.

- ^ a b "Ampliación del cono monetario" (PDF) (Press release) (in Spanish). Banco Central de Venezuela. 20 December 2016. Retrieved 22 August 2018.

- ^ a b c banknotes > Venezuela > series 2007–2015 colnect.com, retrieved 12 December 2016. – Specific (re-)issuing date above pair of signatures above portrait.

- ^ a b "Venezuela's new banknotes". Deutsche Welle. 8 December 2016. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ a b "Venezuela's Maduro orders 100-unit banknotes out of circulation". AFP. 11 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Venezuela pulls most common banknote from circulation to 'beat mafia'". The Guardian. 11 December 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Declaring war on common sense, Venezuela bans its own money". Washington Post. Dec 15, 2016.

- ^ a b c Coutinho, Leonardo (23 February 2017). "Veja: Venezuela y Bolivia son sospechosas de esquema estatal de lavado". Eju TV (in European Spanish). Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "Maduro: El nuevo cono monetario va a coexistir con el viejo "hasta su extensión"". www.noticierodigital.com. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ "Banco Central de Venezuela on Twitter". Twitter. Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ WEB, EL NACIONAL (2018-08-14). "Billetes inferiores a 1.000 bolívares no tendrán valor a partir del 20A". El Nacional (in Spanish). Retrieved 2018-08-14.

- ^ "Venezuelans Are Paying a 100% Premium for Cash". Bloomberg. 2018-03-02. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ^ "Venezuela's Hyperinflation Is Breaking Deli Scales". Bloomberg. 2018-03-14. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ^ "Bolívar Fuerte circulará hasta el miércoles 5 de diciembre | En la Agenda | 2001.com.ve". 2001.com.ve. Retrieved 2018-11-30.

- ^ Krystian (2019-01-06). "Billetes de Bs.S 2 no es aceptado ni en bancos del Estado". Descifrado (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- ^ C, Manuel Tomillo (2019-01-06). "Ya ni los bancos del Estado quieren aceptar los devaluados billetes de Bs.S 2". Caraota Digital (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2019-01-08.

- ^ "Tres nuevos billetes se incorporan al Cono Monetario vigente | Banco Central de Venezuela". bcv.org.ve. Retrieved 2019-06-12.

- ^ "Venezuela adds bigger bank notes due to hyperinflation". Reuters. 12 June 2019. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

Bibliography

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.