North American X-15

| X-15 | |

|---|---|

The X-15 pulling away from its drop launch plane | |

| General information | |

| Type | Experimental high-speed rocket-powered research aircraft |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| Primary users | United States Air Force |

| Number built | 3 |

| History | |

| Introduction date | 17 September 1959 |

| First flight | 8 June 1959 [1] |

| Retired | December 1968 [1] |

The North American X-15 is a hypersonic rocket-powered aircraft operated by the United States Air Force and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as part of the X-plane series of experimental aircraft. The X-15 set speed and altitude records in the 1960s, crossing the edge of outer space and returning with valuable data used in aircraft and spacecraft design. The X-15's highest speed, 4,520 miles per hour (7,274 km/h; 2,021 m/s),[1] was achieved on 3 October 1967,[2] when William J. Knight flew at Mach 6.7 at an altitude of 102,100 feet (31,120 m), or 19.34 miles. This set the official world record for the highest speed ever recorded by a crewed, powered aircraft, which remains unbroken.[3][4]

During the X-15 program, 12 pilots flew a combined 199 flights.[1] Of these, 8 pilots flew a combined 13 flights which met the Air Force spaceflight criterion by exceeding the altitude of 50 miles (80 km), thus qualifying these pilots as being astronauts; of those 13 flights, two (flown by the same civilian pilot) met the FAI definition (100 kilometres (62 mi)) of outer space. The 5 Air Force pilots qualified for military astronaut wings immediately, while the 3 civilian pilots were eventually awarded NASA astronaut wings in 2005, 35 years after the last X-15 flight.[5][6]

Design and development

[edit]

The X-15 was based on a concept study from Walter Dornberger for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) of a hypersonic research aircraft.[7] The requests for proposal (RFPs) were published on 30 December 1954 for the airframe and on 4 February 1955 for the rocket engine. The X-15 was built by two manufacturers: North American Aviation was contracted for the airframe in November 1955, and Reaction Motors was contracted for building the engines in 1956.

Like many X-series aircraft, the X-15 was designed to be carried aloft and drop launched from under the wing of a B-52 mother ship. Air Force NB-52A, "The High and Mighty One" (serial 52-0003), and NB-52B, "The Challenger" (serial 52-0008, also known as Balls 8) served as carrier planes for all X-15 flights. Release of the X-15 from NB-52A took place at an altitude of about 8.5 miles (13.7 km) (45,000 feet) and a speed of about 500 miles per hour (805 km/h).[8] The X-15 fuselage was long and cylindrical, with rear fairings that flattened its appearance, and thick, dorsal and ventral wedge-fin stabilizers. Parts of the fuselage (the outer skin[9]) were heat-resistant nickel alloy (Inconel-X 750).[7] The retractable landing gear comprised a nose-wheel carriage and two rear skids. The skids did not extend beyond the ventral fin, which required the pilot to jettison the lower fin just before landing. The lower fin was recovered by parachute.

Cockpit and pilot systems

[edit]

The X-15 was the product of developmental research, and changes were made to various systems over the course of the program and between the different models. The X-15 was operated under several different scenarios, including attachment to a launch aircraft, drop, main engine start and acceleration, ballistic flight into thin air/space, re-entry into thicker air, unpowered glide to landing, and direct landing without a main-engine start. The main rocket engine operated only for a relatively short part of the flight but boosted the X-15 to its high speeds and altitudes. Without the main rocket engine thrust, the X-15's instruments and control surfaces remained functional, but the aircraft could not maintain altitude.

As the X-15 also had to be controlled in an environment where there was too little air for aerodynamic flight control surfaces, it had a reaction control system (RCS) that used rocket thrusters.[10] There were two different X-15 pilot control setups: one used three joysticks, the other, one joystick.[11]

The X-15 type with multiple control sticks for the pilot placed a traditional center stick between a left 3-axis joystick that sent commands to the Reaction Control System,[12] and a third joystick on the right used during high-G maneuvers to augment the center stick.[12] In addition to pilot input, the X-15 "Stability Augmentation System" (SAS) sent inputs to the aerodynamic controls to help the pilot maintain attitude control.[12] The Reaction Control System (RCS) could be operated in two modes – manual and automatic.[11] The automatic mode used a feature called "Reaction Augmentation System" (RAS) that helped stabilize the vehicle at high altitude.[11] The RAS was typically used for approximately three minutes of an X-15 flight before automatic power off.[11]

The alternative control setup used the MH-96 flight control system, which allowed one joystick in place of three and simplified pilot input.[13] The MH-96 could automatically blend aerodynamic and rocket controls, depending on how effective each system was at controlling the aircraft.[13]

Among the many controls were the rocket engine throttle and a control for jettisoning the ventral tail fin.[12] Other features of the cockpit included heated windows to prevent icing and a forward headrest for periods of high deceleration.[12]

The X-15 had an ejection seat designed to operate at speeds up to Mach 4 (4,500 km/h; 2,800 mph) and/or 120,000 feet (37 km) (23 miles) altitude, although it was never used during the program.[12] In the event of ejection, the seat was designed to deploy fins, which were used until it reached a safer speed/altitude at which to deploy its main parachute.[12] Pilots wore pressure suits, which could be pressurized with nitrogen gas.[12] Above 35,000 feet (11 km) altitude, the cockpit was pressurized to 3.5 psi (24 kPa; 0.24 atm) with nitrogen gas, while oxygen for breathing was fed separately to the pilot.[12]

Propulsion

[edit]

The initial 24 powered flights used two Reaction Motors XLR11 liquid-propellant rocket engines, enhanced to provide a total of 16,000 pounds-force (71 kN) of thrust as compared to the 6,000 pounds-force (27 kN) that a single XLR11 provided in 1947 to make the Bell X-1 the first aircraft to fly faster than the speed of sound. The XLR11 used ethyl alcohol and liquid oxygen.

By November 1960, Reaction Motors delivered the XLR99 rocket engine, generating 57,000 pounds-force (250 kN) of thrust. The remaining 175 flights of the X-15 used XLR99 engines, in a single engine configuration. The XLR99 used anhydrous ammonia and liquid oxygen as propellant, and hydrogen peroxide to drive the high-speed turbopump that delivered propellants to the engine.[10] It could burn 15,000 pounds (6,804 kg) of propellant in 80 seconds;[10] Jules Bergman titled his book on the program Ninety Seconds to Space to describe the total powered flight time of the aircraft.[14]

The X-15 reaction control system (RCS), for maneuvering in the low-pressure/density environment, used high-test peroxide (HTP), which decomposes into water and oxygen in the presence of a catalyst and could provide a specific impulse of 140 s (1.4 km/s).[11][15] The HTP also fueled a turbopump for the main engines and auxiliary power units (APUs).[10] Additional tanks for helium and liquid nitrogen performed other functions; the fuselage interior was purged with helium gas, and liquid nitrogen was used as coolant for various systems.[10]

Wedge tail and hypersonic stability

[edit]

The X-15 had a thick wedge tail to enable it to fly in a steady manner at hypersonic speeds.[16] This produced a significant amount of base drag at lower speeds;[16] the blunt end at the rear of the X-15 could produce as much drag as an entire F-104 Starfighter.[16]

A wedge shape was used because it is more effective than the conventional tail as a stabilizing surface at hypersonic speeds. A vertical-tail area equal to 60 percent of the wing area was required to give the X-15 adequate directional stability.

— Wendell H. Stillwell, X-15 Research Results (SP-60)

Stability at hypersonic speeds was aided by side panels that could be extended from the tail to increase the overall surface area, and these panels doubled as air brakes.[16]

Operational history

[edit]Before 1958, United States Air Force (USAF) and NACA officials discussed an orbital X-15 spaceplane, the X-15B that would launch into outer space from atop an SM-64 Navaho missile. This was canceled when the NACA became NASA and adopted Project Mercury instead.

By 1959, the Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar space-glider program was to become the USAF's preferred means for launching military crewed spacecraft into orbit. This program was canceled in the early 1960s before an operational vehicle could be built.[5] Various configurations of the Navaho were considered, and another proposal involved a Titan I stage.[17]

Three X-15s were built, flying 199 test flights, the last on 24 October 1968.

The first X-15 flight was an unpowered glide flight by Scott Crossfield, on 8 June 1959. Crossfield also piloted the first powered flight on 17 September 1959, and his first flight with the XLR-99 rocket engine on 15 November 1960. Twelve test pilots flew the X-15. Among these were Neil Armstrong, later a NASA astronaut and the first man to set foot on the Moon, and Joe Engle, later a commander of NASA Space Shuttle missions.

In a 1962 proposal, NASA considered using the B-52/X-15 as a launch platform for a Blue Scout rocket to place satellites weighing up to 150 pounds (68 kg) into orbit.[17][18]

In July and August 1963, pilot Joe Walker exceeded 100 km in altitude, joining NASA astronauts and Soviet cosmonauts as the first human beings to cross that line on their way to outer space. The USAF awarded astronaut wings to anyone achieving an altitude of 50 miles (80 km), while the FAI set the limit of space at 100 kilometers (62.1 mi).

On 15 November 1967, U.S. Air Force test pilot Major Michael J. Adams was killed during X-15 Flight 191 when X-15-3, AF Ser. No. 56-6672, entered a hypersonic spin while descending, then oscillated violently as aerodynamic forces increased after re-entry. As his aircraft's flight control system operated the control surfaces to their limits, acceleration built to 15 g0 (150 m/s2) vertical and 8.0 g0 (78 m/s2) lateral. The airframe broke apart at 60,000 feet (18 km) altitude, scattering the X-15's wreckage across 50 square miles (130 km2). On 8 May 2004, a monument was erected at the cockpit's locale, near Johannesburg, California.[19] Major Adams was posthumously awarded Air Force astronaut wings for his final flight in X-15-3, which had reached an altitude of 50.4 miles (81.1 km). In 1991, his name was added to the Astronaut Memorial.[19]

The second plane, X-15-2, was rebuilt [20] after a landing accident on 9 November 1962 which damaged the craft and injured its pilot, John McKay.[21] The new plane renamed X-15A-2, had a new 28 -in. fuselage extension to carry liquid hydrogen.[1] It was lengthened by 2.4 feet (73 cm), had a pair of auxiliary fuel tanks attached beneath its fuselage and wings, and a complete heat-resistant ablative coating was added. It took flight for the first time on 25 June 1964. It reached its maximum speed of 4,520 miles per hour (7,274 km/h) in October 1967 with pilot William "Pete" Knight of the U.S. Air Force in control.

Five principal aircraft were used during the X-15 program: three X-15 planes and two modified "nonstandard" NB-52 bombers:

- X-15-1 – 56-6670, 81 free flights

- X-15-2 (later X-15A-2) – 56-6671, 31 free flights as X-15-2, 22 free flights as X-15A-2; 53 in total

- X-15-3 – 56-6672, 65 free flights, including the Flight 191 disaster

- NB-52A – 52-003 nicknamed The High and Mighty One (retired in October 1969)

- NB-52B – 52-008 nicknamed The Challenger, later Balls 8 (retired in November 2004)

Additionally, F-100, F-104 and F5D chase aircraft and C-130 and C-47 transports supported the program.[22]

The 200th flight over Nevada was first scheduled for 21 November 1968, to be flown by William "Pete" Knight. Numerous technical problems and outbreaks of bad weather delayed this proposed flight six times, and it was permanently canceled on 20 December 1968. This X-15 (56-6670) was detached from the B-52 and then put into indefinite storage. The aircraft was later donated to the Smithsonian Air & Space Museum for display.

-

NB-52A (s/n 52-003), permanent test variant, carrying an X-15, with mission markings; horizontal X-15 silhouettes denote glide flights, diagonal silhouettes denote powered flights.

-

X-15 just after release.

-

X-15 touching down on its skids, with the lower ventral fin jettisoned.

-

X-15A-2 (56-6671) with external fuel tanks

-

X-15 profiles

-

X-15A-2 with pink ablative coating before being covered with white sealant

Aircraft on display

[edit]

Both surviving X-15s are currently on display at museums in the United States. In addition, three mockups and both B-52 Stratofortresses used as motherships are on display as well.

- X-15-1 (AF Ser. No. 56-6670) is on display in the National Air and Space Museum "Milestones of Flight" gallery, Washington, D.C., but is currently undergoing conservation work at the Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar in the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center.

- X-15A-2 (AF Ser. No. 56-6671) is at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio. It was retired to the museum in October 1969.[23] The aircraft is displayed in the museum's Research and Development Gallery alongside other "X-planes", including the Bell X-1B and Douglas X-3 Stiletto.

Mockups

[edit]- Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards AFB, California, United States (painted with AF Ser. No. 56-6672)

- Pima Air & Space Museum, adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB, Tucson, Arizona (painted with AF Ser. No. 56-6671)

- Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum, McMinnville, Oregon (painted with AF Ser. No. 56-6672). A full-scale wooden mockup of the X-15, it is displayed along with one of the rocket engines.

Stratofortress mother ships

[edit]

- NB-52A (AF Ser. No. 52-003) is displayed at the Pima Air & Space Museum adjacent to Davis–Monthan AFB in Tucson, Arizona. It launched the X-15-1 30 times, the X-15-2, 11 times, and the X-15-3 31 times (as well as the M2-F2 four times, the HL-10 11 times and the X-24A twice).

- NB-52B (AF Ser. No. 52-008) is on permanent display outside the north gate of Edwards AFB, California. It launched the majority of X-15 flights.

Record flights

[edit]

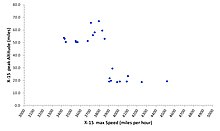

Highest flights

[edit]During 13 of the 199 total X-15 flights, eight pilots flew above 264,000 feet (50.0 mi; 80 km), thereby qualifying as astronauts according to the US Armed Forces definition of the space border. All five Air Force pilots flew above 50 miles and were awarded military astronaut wings contemporaneously with their achievements, including Adams, who received the distinction posthumously following the flight 191 disaster.[24] However the other three were NASA employees and did not receive a comparable decoration at the time. In 2004, the Federal Aviation Administration conferred its first-ever commercial astronaut wings on Mike Melvill and Brian Binnie, pilots of the commercial SpaceShipOne, another spaceplane with a flight profile comparable to the X-15's. Following this in 2005, NASA retroactively awarded its civilian astronaut wings to Dana (then living), and to McKay and Walker (posthumously).[25][26] Forrest S. Petersen, the only Navy pilot in the X-15 program, never took the aircraft above the requisite altitude and thus never earned astronaut wings.

Of the thirteen flights, only two — flights 90 and 91, piloted by Walker — exceeded the 100 km (62 mi) altitude used by the FAI to denote the Kármán line.

| Flight | Date | Top speed[a] | Altitude | Pilot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight 91 | 22 August 1963 | 3,794 mph (6,106 km/h) (Mach 5.58) | 67.1 mi (108.0 km) | Joseph A. Walker |

| Flight 90 | 19 July 1963 | 3,710 mph (5,971 km/h) (Mach 5.50) | 65.9 mi (106.1 km) | Joseph A. Walker |

| Flight 62 | 17 July 1962 | 3,832 mph (6,167 km/h) (Mach 5.45) | 59.6 mi (95.9 km) | Robert M. White |

| Flight 174 | 1 November 1966 | 3,750 mph (6,035 km/h) (Mach 5.46) | 58.1 mi (93.5 km) | William H. "Bill" Dana |

| Flight 150 | 28 September 1965 | 3,732 mph (6,006 km/h) (Mach 5.33) | 56.0 mi (90.1 km) | John B. McKay |

| Flight 87 | 27 June 1963 | 3,425 mph (5,512 km/h) (Mach 4.89) | 54.0 mi (86.9 km) | Robert A. Rushworth |

| Flight 138 | 29 June 1965 | 3,432 mph (5,523 km/h) (Mach 4.94) | 53.1 mi (85.5 km) | Joe H. Engle |

| Flight 190 | 17 October 1967 | 3,856 mph (6,206 km/h) (Mach 5.53) | 53.1 mi (85.5 km) | William J. "Pete" Knight |

| Flight 77 | 17 January 1963 | 3,677 mph (5,918 km/h) (Mach 5.47) | 51.5 mi (82.9 km) | Joseph A. Walker |

| Flight 143 | 10 August 1965 | 3,550 mph (5,713 km/h) (Mach 5.20) | 51.3 mi (82.6 km) | Joe H. Engle |

| Flight 197 | 21 August 1968 | 3,443 mph (5,541 km/h) (Mach 5.01) | 50.7 mi (81.6 km) | William H. Dana |

| Flight 153 | 14 October 1965 | 3,554 mph (5,720 km/h) (Mach 5.08) | 50.5 mi (81.3 km) | Joe H. Engle |

| Flight 191 | 15 November 1967 | 3,570 mph (5,745 km/h) (Mach 5.20) | 50.4 mi (81.1 km) | Michael J. Adams† |

† fatal

Fastest recorded flights

[edit]| Flight | Date | Top speed[a] | Altitude | Pilot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight 188 | 3 October 1967 | 4,520 mph (7,274 km/h) (Mach 6.70) | 19.3 mi (31.1 km) | William J. "Pete" Knight |

| Flight 175 | 18 November 1966 | 4,250 mph (6,840 km/h) (Mach 6.33) | 18.7 mi (30.1 km) | William J. "Pete" Knight |

| Flight 59 | 27 June 1962 | 4,104 mph (6,605 km/h) (Mach 5.92) | 23.4 mi (37.7 km) | Joseph A. Walker |

| Flight 45 | 9 November 1961 | 4,093 mph (6,587 km/h) (Mach 6.04) | 19.2 mi (30.9 km) | Robert M. White |

| Flight 97 | 5 December 1963 | 4,018 mph (6,466 km/h) (Mach 6.06) | 19.1 mi (30.7 km) | Robert A. Rushworth |

| Flight 64 | 26 July 1962 | 3,989 mph (6,420 km/h) (Mach 5.74) | 18.7 mi (30.1 km) | Neil A. Armstrong |

| Flight 137 | 22 June 1965 | 3,938 mph (6,338 km/h) (Mach 5.64) | 29.5 mi (47.5 km) | John B. McKay |

| Flight 89 | 18 July 1963 | 3,925 mph (6,317 km/h) (Mach 5.63) | 19.8 mi (31.9 km) | Robert A. Rushworth |

| Flight 86 | 25 June 1963 | 3,911 mph (6,294 km/h) (Mach 5.51) | 21.2 mi (34.1 km) | Joseph A. Walker |

| Flight 105 | 29 April 1964 | 3,906 mph (6,286 km/h) (Mach 5.72) | 19.2 mi (30.9 km) | Robert A. Rushworth |

Pilots

[edit]-

The X-15 flight crew, left to right: Air Force Captain Joseph H. Engle, Air Force Major Robert A. Rushworth, NASA pilot John B. "Jack" McKay, Air Force Major William J. "Pete" Knight, NASA pilot Milton O. Thompson, and NASA pilot William H. Dana.

-

The X-15 pilots clown around in front of the #2 aircraft. From left to right: Joseph Engle, Robert Rushworth, John McKay, William Knight, Milton Thompson, and William Dana.

| Pilot | Organization | Year assigned to X-15[30][31] |

Total flights |

USAF space flights |

FAI space flights |

Max Mach |

Max speed (mph) |

Max altitude (miles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michael J. Adams† | U.S. Air Force | 1966 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 5.59 | 3,822 | 50.3 |

| Neil A. Armstrong | NASA | 1960[32] | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5.74 | 3,989 | 39.2 |

| Scott Crossfield | North American Aviation | 1959 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2.97 | 1,959 | 15.3 |

| William H. Dana | NASA | 1965 | 16 | 2 | 0 | 5.53 | 3,897 | 58.1 |

| Joe H. Engle | U.S. Air Force | 1963 | 16 | 3 | 0 | 5.71 | 3,887 | 53.1 |

| William J. Knight | U.S. Air Force | 1964 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 6.7 | 4,519 | 53.1 |

| John B. McKay | NASA | 1960 | 29 | 1 | 0 | 5.65 | 3,863 | 55.9 |

| Forrest S. Petersen | U.S. Navy | 1958 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 | 3,600 | 19.2 |

| Robert A. Rushworth | U.S. Air Force | 1958 | 34 | 1 | 0 | 6.06 | 4,017 | 53.9 |

| Milton O. Thompson | NASA | 1963 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 5.48 | 3,723 | 40.5 |

| Joseph A. Walker†† | NASA | 1960[33] | 25 | 3 | 2 | 5.92 | 4,104 | 67.0 |

| Robert M. White | U.S. Air Force | 1957 | 16 | 1 | 0 | 6.04 | 4,092 | 59.6 |

† Killed in the crash of X-15-3

†† Died in a group formation accident on June 8, 1966.

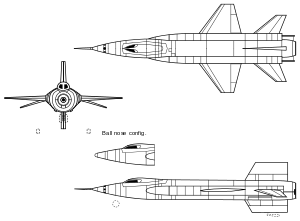

Specifications

[edit]

Other configurations include the Reaction Motors XLR11 equipped X-15, and the long version.

Data from [31]

General characteristics

- Crew: One

- Length: 49 ft 2 in (14.99 m) [b]

- Wingspan: 22 ft 4 in (6.81 m) [c]

- Height: 13 ft 1 in (3.99 m) [d]

- Wing area: 200 sq ft (19 m2)

- Empty weight: 14,600 lb (6,622 kg) [e]

- Gross weight: 33,500 lb (15,195 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Reaction Motors XLR99-RM-2 liquid-fuelled rocket engine, 70,400 lbf (313 kN) thrust

Performance

- Maximum speed: 4,520 mph (7,270 km/h, 3,930 kn)

- Range: 280 mi (450 km, 240 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 354,330 ft (108,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 60,000 ft/min (300 m/s)

- Thrust/weight: 2.07

In popular culture

[edit]See also

[edit]Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b The speed of sound in the atmosphere varies with altitude, so a comparatively lower airspeed (measured in mph or km/h) can correspond to a higher Mach number.[27]

- ^

- 56’ 1.5” With nose boom and XLR-11 rocket engine

- 55’ 2.5” With nose boom and XLR-99 rocket engine

- 50’ 1” With Q-Ball nose and XLR-11 rocket engine

- 49’ 2” With Q-Ball nose and XLR-99 rocket engine

- 51’ 11” Modified 66671 aircraft (X-15A-2)

- ^

- 22’ 4” Standard aircraft

- 23’ 8” With wing tip pods

- ^

- 13’ 1” Standard aircraft

- 11’ 6” Without lower ventral fin and with landing gear extended

- ^

- Burn-out weight: 14,500 lb Standard aircraft

- Landing weight: 13,800 lb Standard aircraft

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Gibbs, Yvonne, ed. (28 February 2014). "NASA Armstrong Fact Sheet: X-15 Hypersonic Research Program". NASA. Retrieved 4 October 2015.

4,520 mph (Mach 6.7 on Oct. 3, 1967,

- ^ Haskins, Caroline; Anderson, Brian; Koebler, Jason (6 October 2017). "Why the Piloted Flight Speed Record Hasn't Been Broken in 50 Years". Retrieved 5 February 2019.

- ^ "North American X-15 High-Speed Research Aircraft". Aerospaceweb.org. 2010. Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ^ Jacopo Prisco (28 July 2020). "X-15: The fastest manned rocket plane ever". CNN. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2001, p. 10.

- ^ Thompson, Elvia H.; Johnsen, Frederick A. (23 August 2005). "NASA Honors High Flying Space Pioneers" (Press release). NASA. Release 05-233. Archived from the original on 13 April 2018. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- ^ a b Käsmann 1999, p. 105.

- ^ "X-15 launch from B-52 mothership". Armstrong Flight Research Center. 6 February 2002. Photo E-4942.

- ^ Gibbs, Yvonne (13 August 2015). "NASA Dryden Fact Sheets - X-15 Hypersonic Research Program". NASA.

- ^ a b c d e Raveling, Paul. "X-15 Pilot Report, Part 1: X-15 General Description & Walkaround". SierraFoot.org. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Jarvis, Calvin R.; Lock, Wilton P. (1965). Operational Experience With the X-15 Reaction Control and Reaction Augmentation Systems (PDF). NASA. OCLC 703664750. TN D-2864. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Raveling, Paul. "X-15 Pilot Report, Part 2: X-15 Cockpit Check". SierraFoot.org. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ a b "Forty Years ago in the X-15 Flight Test Program, November 1961–March 1962". Goleta Air & Space Museum. Retrieved 3 October 2011.

- ^ Gale, Floyd C. (October 1961). "Galaxy's 5-Star Shelf". Galaxy Magazine. Vol. 20, no. 1. p. 174.

- ^ Davies 2003, p. 8.28.

- ^ a b c d Stillwell, Wendell H. (1965). X-15 Research Results: With a Selected Bibliography. NASA. OCLC 44275779. NASA SP-60. Archived from the original on 13 April 2022. Retrieved 4 May 2003.

- ^ a b Wade, Mark. "X-15/Blue Scout". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on 11 October 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2011.

- ^ "Historical note: Blue Scout / X-15". Citizensinspace.org. 21 March 2012.

- ^ a b Merlin, Peter W. (30 July 2004). "Michael Adams: Remembering a Fallen Hero". The X-Press. 46 (6).

- ^ Evans 2013a, p. 183

- ^ Evans 2013a, p. 143

- ^ Jenkins, Dennis R. (2010). X-15: Extending The Frontiers of Flight. NASA. ISBN 978-1-4700-2585-4.

- ^ USAF Museum Guidebook 1975, p. 73.

- ^ Jenkins (2000), Appendix 8, p. 117.

- ^ Johnsen, Frederick A. (23 August 2005). "X-15 Pioneers Honored as Astronauts". NASA. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2019.

- ^ Pearlman, Robert Z. (23 August 2005). "Former NASA X-15 Pilots Awarded Astronaut Wings". space.com.

- ^ a b Evans 2013b, p. 12

- ^ a b X-15 First Flight 1991, Appendix A.

- ^ Evans 2013b

- ^ Cassutt, Michael (November 1998). Who's Who in Space (Subsequent ed.). New York: Macmillan Library Reference. ISBN 9780028649658.

- ^ a b Evans, Michelle (2013). "The X-15 Rocket Plane: Flying the First Wings Into Space-Flight Log" (PDF). Mach 25 Media. pp. 5, 32, 33.

- ^ Gibbs, Yvonne (2 June 2015). "Neil Armstrong with X-15 #1 After Flight". NASA. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

Armstrong was actively engaged in both piloting and engineering aspects of the X-15 program from its inception. He completed the first flight in the aircraft equipped with a new flow-direction sensor (ball nose) and the initial flight in an X-15 equipped with a self-adaptive flight control system. He worked closely with designers and engineers in development of the adaptive system, and made seven flights in the rocket plane from December 1960 until July 1962.

- ^ Conner, Monroe (23 June 2020). "Joseph A. Walker". NASA. Archived from the original on 6 December 2021. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Davies, Mark, ed. (2003). The Standard Handbook for Aeronautical and Astronautical Engineers. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 8–28. ISBN 978-0-07-136229-0.

- Evans, Michelle (2013a). The X-15 Rocket Plane, Flying the First Wings into Space. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-2840-5.

- Evans, Michelle (2013b). "The X-15 Rocket Plane: Flying the First Wings Into Space - Flight Log" (PDF). Mach 25 Media.

- Godwin, Robert, ed. (2001). X-15: The NASA Mission Reports. Burlington, Ontario: Apogee Books. ISBN 1-896522-65-3.

- Hallion, Richard P. (1978). "Saga of the Rocket Ships". In Green, William; Swanborough, Gordon (eds.). Air Enthusiast Six. Bromley, Kent, UK: Pilot Press.

- Jenkins, Dennis R. (2001). Space Shuttle: The History of the National Space Transportation System: The First 100 Missions (3rd ed.). Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-9633974-5-1.

- Jenkins, Dennis R.; Landis, Tony; Miller, Jay (June 2003). American X-Vehicles: An Inventory – X-1 to X-50 (PDF). Monographs in Aerospace History No. 31. NASA. OCLC 68623213. SP-2003-4531. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2020.

- Jenkins, Dennis R.; Dana, William H. (2010). X-15: Extending the Frontiers of Flight. NASA. ISBN 978-0-16-079285-4. SP-2007-562.

- Käsmann, Ferdinand C. W. (1999). Die schnellsten Jets der Welt: Weltrekord-Flugzeuge [The Fastest Jets in the World: World Record Aircraft] (in German). Kolpingring, Germany: Aviatic Verlag. ISBN 3-925505-26-1.

- Price, A. B. (12 January 1968). Design Report – Thermal Protection System, X-15A-2. Denver, Colorado: Martin Marietta Corporation. NASA CR-82003.

- Proceedings of the X-15 First Flight 30th Anniversary Celebration (PDF). NASA. January 1991. NASA CP-3105.

- Thompson, Milton O. (1992). At the Edge of Space: The X-15 Flight Program. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. ISBN 1-56098-107-5.

- Tregaskis, Richard (2000). X-15 Diary: The Story of America's First Space Ship. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse. ISBN 0-595-00250-1.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: Air Force Museum Foundation. 1975.

- Watts, Joe D. (October 1968). Flight Experience With Shock Impingement and Interference Heating on the X-15-2 Research Airplane (PDF). NASA. NASA-TM-X-1669.

External links

[edit]- NASA

- X-15: Hypersonic Research at the Edge of Space

- Hypersonics Before the Shuttle: A Concise History of the X-15 Research Airplane

- The short film Research Project X-15 is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.

- Non-NASA

- X-15A at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- X-15: Advanced Research Airplane, design summary by North America Aviation

- X-15 program

- North American Aviation aircraft

- 1950s United States experimental aircraft

- Rocket-powered aircraft

- Mid-wing aircraft

- Hypersonic aircraft

- Spaceplanes

- Crewed spacecraft

- Suborbital spaceflight

- High-test peroxide

- 1963 in spaceflight

- Aircraft first flown in 1959

- Reusable spacecraft

- Cruciform tail aircraft