Human history: Difference between revisions

Golden Mage (talk | contribs) |

Cerebellum (talk | contribs) add paragraph on contact between Polynesians and Native Americans |

||

| Line 247: | Line 247: | ||

At around the same time, a powerful [[thalassocracy]] appeared in eastern Polynesia, centred around the [[Society Islands]], specifically on the sacred [[Taputapuatea marae]], which drew in eastern Polynesian colonists from places as far away as Hawaii, New Zealand (''[[Aotearoa]]''), and the Tuamotu Islands for political, spiritual, and economic reasons, until the unexplained collapse of regular long-distance voyaging in the eastern Pacific a few centuries before Europeans began exploring the area. |

At around the same time, a powerful [[thalassocracy]] appeared in eastern Polynesia, centred around the [[Society Islands]], specifically on the sacred [[Taputapuatea marae]], which drew in eastern Polynesian colonists from places as far away as Hawaii, New Zealand (''[[Aotearoa]]''), and the Tuamotu Islands for political, spiritual, and economic reasons, until the unexplained collapse of regular long-distance voyaging in the eastern Pacific a few centuries before Europeans began exploring the area. |

||

The question of [[Pre-Columbian transoceanic contact theories|pre-Columbian contact]] between Polynesians and Native Americans has long been controversial.<ref name="Ioannidis et al."/> In 2020, a genome-wide DNA analysis of Polynesians and Native South Americans shed new light on the debate by reporting evidence of [[genetic admixture|intermingling]] between Polynesian people and [[pre-Columbian cultures of Colombia|pre-Columbian]] [[Zenú|Zenú people]] around 1200 CE.<ref name="Ioannidis et al.">{{Cite journal|last1=Ioannidis|first1=Alexander G.|last2=Blanco-Portillo|first2=Javier|last3=Sandoval|first3=Karla|last4=Hagelberg|first4=Erika|last5=Miquel-Poblete|first5=Juan Francisco|last6=Moreno-Mayar|first6=J. Víctor|last7=Rodríguez-Rodríguez|first7=Juan Esteban|last8=Quinto-Cortés|first8=Consuelo D.|last9=Auckland|first9=Kathryn|last10=Parks|first10=Tom|last11=Robson|first11=Kathryn|date=2020-07-08|title=Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement|journal=Nature|volume=583|issue=7817|pages=572–577|language=en|doi=10.1038/s41586-020-2487-2|pmid=32641827|pmc=8939867 |bibcode=2020Natur.583..572I|s2cid=220420232|issn=0028-0836}}</ref> Whether this happened because of [[indigenous peoples of the Americas|indigenous American]] people reaching eastern Polynesia or because the northern coast of South America was visited by Polynesians is not clear.<ref>{{cite web |last=Wade |first=Lizzie |date=8 July 2020 |title=Polynesians steering by the stars met Native Americans long before Europeans arrived |url=https://www.science.org/content/article/polynesians-steering-stars-met-native-americans-long-europeans-arrived |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200717034835/https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/07/polynesians-steering-stars-met-native-americans-long-europeans-arrived |archive-date=17 July 2020 |access-date=11 July 2020 |work=[[Science (journal)|Science]] }}</ref> |

|||

Indigenous written records from this period are virtually nonexistent, as it seems that all [[Pacific Islander]]s, with the possible exception of the [[Rapa Nui people|Rapa Nui]] and their currently undeciphered [[Rongorongo]] script, had no writing systems of any kind until after their introduction by European colonists. However, some indigenous prehistories can be estimated and academically reconstructed through careful, judicious analysis of native oral traditions, colonial ethnography, archaeology, physical anthropology, and linguistics research. |

Indigenous written records from this period are virtually nonexistent, as it seems that all [[Pacific Islander]]s, with the possible exception of the [[Rapa Nui people|Rapa Nui]] and their currently undeciphered [[Rongorongo]] script, had no writing systems of any kind until after their introduction by European colonists. However, some indigenous prehistories can be estimated and academically reconstructed through careful, judicious analysis of native oral traditions, colonial ethnography, archaeology, physical anthropology, and linguistics research. |

||

Revision as of 09:44, 27 June 2023

| Part of a series on |

| Human history |

|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Stone Age) (Pleistocene epoch) |

| ↓ Future |

Human history is the narrative of humankind's past. Humans evolved in Africa c. 300,000 years ago and initially lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers. Humans migrated out of Africa during the Last Glacial Period (Ice Age) and had colonized almost the entire Earth by the time the Ice Age ended 12,000 years ago.

The Agricultural Revolution began in fertile river valleys of the Near East around 10,000 BCE: humans began the systematic husbandry of plants and animals, and many humans transitioned from a nomadic life to a sedentary existence as farmers in permanent settlements. As efficient grain husbandry developed, surpluses fostered the development of advanced non-agricultural occupations, division of labor, social stratification, including the rise of a leisured upper class, and urbanization. The growing complexity of human societies necessitated systems of accounting and writing. True writing is first recorded in Sumer at the end of the 4th millennium BCE, followed soon after in other parts of the Near East.

During the late Bronze Age, Hinduism developed in the Indian subcontinent, while the Axial Age witnessed the appearance of religions such as Buddhism, Jainism, Judaism, Taoism, and Zoroastrianism. As civilizations flourished, ancient history saw the rise and fall of empires. Subsequent post-classical history (the "Middle Ages", from about 500 to 1500 CE) witnessed the rise of Christianity and Islam, as well as the Renaissance (from around 1300 CE).

The 15th-century introduction of movable-type printing in Europe facilitated the dissemination of information, hastening the end of the Middle Ages and eventually enabling the Scientific Revolution. The early modern period, from about 1500 to 1800 CE, saw the Age of Discovery and the Age of Enlightenment. Sikhism also flourished in the Punjab. By the 18th century, the accumulation of knowledge and technology had reached a critical mass that brought about the Industrial Revolution and began the late modern period, which started around 1800 CE and continues.

The foregoing historical periodization (antiquity, followed by the post-classical, early-modern, and late-modern periods) applies best to the history of Europe. Elsewhere, including China and India, historical timelines unfolded differently up to the 18th century. By then, however, due to extensive international trade and colonization, the histories of most civilizations had become substantially intertwined. Over the last quarter-millennium, the rates of growth of human populations, agriculture, industry, commerce, scientific knowledge, technology, communications, weapons destructiveness, and environmental degradation have greatly accelerated.

Prehistory (c. 3.3 million years ago – c. 3000 BCE)

Human evolution

Humans evolved in Africa from other primates.[2] Genetic measurements indicate that the ape lineage which would lead to Homo sapiens diverged from the lineage that would lead to chimpanzees and bonobos, the closest living relatives of modern humans, somewhere between 13 million and 5 million years ago.[3][4][5] The term hominin denotes human ancestors that lived after the split with chimpanzees and bonobos,[6] including many species and at least two distinct genera: Australopithecus and Homo.[7] Other fossil specimens such as Paranthropus, Kenyanthropus, and Orrorin may represent additional genera, but paleontologists debate their taxonomic status.[7] The early hominins such as Australopithecus had the same brain size as apes but were distinguished from apes by walking on two legs, an adaptation perhaps associated with a shift from forest to savanna habitats.[8] Hominins began to use rudimentary stone tools c. 3.3 million years ago,[a] marking the advent of the Paleolithic era.[12][13]

The genus Homo evolved from Australopithecus.[14] The earliest members of Homo share key traits with Australopithecus, but tend to have larger brains and smaller teeth.[15][16] The earliest record of Homo is the 2.8 million-year-old specimen LD 350-1 from Ethiopia,[16] and the earliest named species is Homo habilis which evolved by 2.3 million years ago.[17] H. erectus (the African variant is sometimes called H. ergaster) evolved by 2 million years ago[18][b] and was the first hominin species to leave Africa and disperse across Eurasia.[20] Perhaps as early as 1.5 million years ago, but certainly by 250,000 years ago, humans began to use fire for heat and cooking.[21][22]

Beginning about 500,000 years ago, Homo diversified into many new species of archaic humans such as the Neanderthals in Europe, the Denisovans in Siberia, and the diminutive H. floresiensis in Indonesia.[23][24] Human evolution was not a simple linear or branched progression but involved interbreeding between related species.[25][26] Genomic research has shown that hybridization between substantially diverged lineages was common in human evolution.[27] DNA evidence suggests that several genes of Neanderthal origin are present among all non-African populations, and Neanderthals and other hominins, such as Denisovans, may have contributed up to 6% of their genome to present-day humans.[28][29]

Early humans

Homo sapiens emerged in Africa around 300,000 years ago from a species commonly designated as either H. heidelbergensis or H. rhodesiensis, who had already developed a culture of hunting, as the Schöningen spears show.[30] Humans continued to develop over the succeeding millennia, and by 100,000 years ago, were already using jewellery and ochre to adorn the body.[31] By 50,000 years ago, they exhibited many characteristic behaviors such as burial of the dead, use of projectile weapons, and seafaring.[32] One of the most important changes (the date of which is unknown) was the development of syntactic language, which dramatically improved humans' ability to communicate.[33] Signs of early artistic expression can be found in the form of cave paintings and sculptures made from ivory, stone, and bone, implying a form of spirituality generally interpreted as animism[34] or shamanism.[35] Paleolithic humans lived as hunter-gatherers and were generally nomadic.[36] They inhabited grasslands or sparsely wooded areas and avoided dense forest cover.[37]

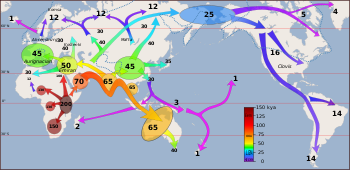

The migration of anatomically modern humans out of Africa took place in multiple waves beginning 194,000–177,000 years ago.[38][c] The dominant view among scholars (Southern Dispersal) is that the early waves of migration died out and all modern non-Africans are descended from a single group that left Africa 70,000–50,000 years ago.[42][43][44] H. sapiens proceeded to colonize all the continents and larger islands, arriving in Australia 65,000 years ago,[45] Europe 45,000 years ago,[42] and the Americas by 21,000 years ago.[46] These migrations occurred during the most recent Ice Age, when temperate regions of today were extremely inhospitable.[47] Nevertheless, by the end of the Ice Age some 12,000 years ago, humans had colonized nearly all ice-free parts of the globe.[48] Human expansion coincided with both the Quaternary extinction event and the extinction of the Neanderthals.[49] These extinctions were probably caused by climate change, human activity, or a combination of the two.[50][51]

Rise of agriculture

Beginning around 10,000 BCE, the Neolithic Revolution marked the development of agriculture, which fundamentally changed the human lifestyle.[52] Agriculture began independently in different parts of the globe,[53] and included a diverse range of taxa, in at least 11 separate centres of origin.[54] Cereal crop cultivation and animal domestication had occurred in Mesopotamia by at least 8500 BCE in the form of wheat, barley, sheep, and goats.[55] The Yangtze River Valley in China domesticated rice around 8000 BCE; the Yellow River Valley may have cultivated millet by 7000 BCE.[56] Pigs were the most important domesticated animal in early China.[57] People in Africa's Sahara cultivated sorghum and several other crops between 8000 and 5000 BCE,[d] while other agricultural centres arose in the Ethiopian Highlands and the West African rainforests.[59] In the Indus River Valley, crops were cultivated by 7000 BCE and cattle were domesticated by 6500 BCE.[60] In the Americas, squash was cultivated by at least 8500 BCE in South America, and domesticated arrowroot appeared in Central America by 7800 BCE.[61] Potatoes were first cultivated in the Andes of South America, where the llama was also domesticated.[62] It is likely that women played a central role in plant domestication throughout these developments.[63][64]

There is no scholarly consensus on why the Neolithic Revolution occurred.[65] For example, in some theories agriculture was the result of an increase in population which led people to seek out new food sources, while in others agriculture was the cause of population growth as the food supply improved.[66] Other proposed factors include climate change, resource scarcity, and ideology.[67] The effects of the transition to agriculture are better understood: it created food surpluses that could support people not directly engaged in food production,[68] permitting far denser populations and the creation of the first cities and states.[52]

Cities were centres of trade, manufacturing, and political power.[69] Cities established a symbiosis with their surrounding countrysides, absorbing agricultural products and providing, in return, manufactured goods and varying degrees of political control.[70][71] Early proto-cities appeared at Jericho and Çatalhöyük around 6000 BCE.[72] Pastoral societies based on nomadic animal herding also developed, mostly in dry areas unsuited for plant cultivation such as the Eurasian Steppe or the African Sahel.[73] Conflict between nomadic herders and sedentary agriculturalists occurred frequently and became a recurring theme in world history.[74]

Metalworking was first used in the creation of copper tools and ornaments around 6400 BCE.[59] Gold and silver soon followed, primarily for use in ornaments.[59] The need for metal ores stimulated trade, as many areas of early human settlement lacked the necessary ores.[75] The first signs of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin, date to around 2500 BCE, but the alloy did not become widely used until much later.[76]

Neolithic societies usually worshiped ancestors, sacred places, or anthropomorphic deities.[77] Entities such as the Sun, Moon, Earth, sky, and sea were often deified.[78] The vast complex of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, dated 9500–8000 BCE,[79] is a spectacular example of a Neolithic religious or civic site.[80] It may have been built by hunter-gatherers rather than a sedentary population.[80] Elaborate mortuary practices developed in the Levant during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, in which certain high-status individuals were buried under the floors of houses and the graves were later re-opened for the skulls to be removed.[81] Some of the skulls were then covered in plaster, painted, and displayed in public.[82][83]

Ancient history (c. 3000 BCE – c. 500 CE)

Cradles of civilization

The Bronze Age saw the development of cities and civilizations.[84][85] Early civilizations arose close to rivers, first in Mesopotamia (3000 BCE) with the Tigris and Euphrates,[86][87][88] followed by the Egyptian civilization along the Nile River (3000 BCE),[89][90] the Indus Valley civilization in Pakistan and northwestern India (2500 BCE),[91][92][93] and the Chinese civilization along the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers (2200 BCE).[94][95]

These societies developed a number of unifying characteristics, including a central government, a complex economy and social structure, systems for keeping records, and distinct cultures and religions.[96] These cultures variously invented the wheel,[97] mathematics,[98] bronze-working,[99] sailing boats,[100] the potter's wheel,[99] woven cloth,[101] construction of monumental buildings,[101] and writing.[102] Polytheistic religions developed, centred on temples where priests and priestesses performed sacrificial rites.[103]

Writing facilitated the administration of cities, the expression of ideas, and the preservation of information.[104] Scholars recognize that writing may have independently developed in at least four ancient civilizations: Mesopotamia (3300 BCE),[105] Egypt (around 3250 BCE),[106][107] China (1200 BCE),[108] and lowland Mesoamerica (by 650 BCE).[109] Among the earliest surviving written religious scriptures are the Egyptian Pyramid Texts, the oldest of which date to between 2400 and 2300 BCE.[110]

Sumer, located in Mesopotamia, is the first known complex civilization, having developed the first city-states in the 4th millennium BCE.[87] It was these cities that produced the earliest known form of writing, cuneiform script.[111] Cuneiform writing began as a system of pictographs, whose pictorial representations eventually became simplified and more abstract.[111] Cuneiform texts were written by using a blunt reed as a stylus to draw symbols upon clay tablets.[112]

Transport was facilitated by waterways—by rivers and seas.[113] The Mediterranean Sea, at the juncture of three continents, fostered the projection of military power and the exchange of goods, ideas, and inventions.[114] This era also saw new land technologies, such as horse-based cavalry and chariots, that allowed armies to move faster.[99] Trade increasingly became a source of power as states with access to important resources or controlling important trade routes rose to dominance.[115]

The growth of cities was often followed by the establishment of states and empires.[116] In Mesopotamia, there prevailed a pattern of independent warring city-states and of a loose hegemony shifting from one city to another.[117] In Egypt, by contrast, the initial division into Upper and Lower Egypt was followed by unification of all the valley around 3100 BCE.[118] In Crete, the Minoan civilization had entered the Bronze Age by 2700 BCE and is regarded as the first civilization in Europe.[119] Around 2600 BCE, the Indus Valley civilization built major cities at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro and developed a writing system of over 400 symbols, which remains undeciphered.[120][121] China entered the Bronze Age by 2000 BCE.[122] The Shang dynasty (1766–1045 BCE) was the first to use writing, inscribing the results of divination ceremonies on oracle bones – ox shoulder blades and turtle shells.[122][123] In the 25th–21st centuries BCE, the empires of Akkad and the Neo-Sumerians arose in Mesopotamia.[124]

Over the following millennia, civilizations developed across the world.[125] By 1600 BCE, Mycenaean Greece began to develop.[126] It flourished until the Late Bronze Age collapse that affected many Mediterranean civilizations between 1300 and 1000 BCE.[127] In India, this era was the Vedic period (1750–600 BCE), which laid the foundations of Hinduism and other cultural aspects of early Indian society, and ended in the 6th century BCE.[128] The Vedas contain the earliest references to India's caste system, which divided society into four hereditary classes: priests, warriors, farmers and traders, and laborers.[129] From around 550 BCE, many independent kingdoms and republics known as the Mahajanapadas were established across the subcontinent.[130]

Speakers of the Bantu languages began expanding across Central and Southern Africa as early as 3000 BCE.[131] Their expansion and encounters with other groups resulted in the spread of mixed farming and ironworking throughout sub-Saharan Africa, and produced societies such as the Nok culture in modern Nigeria by 500 BCE.[132] The Lapita culture emerged in the Bismarck Archipelago near New Guinea around 1500 BCE and colonized many uninhabited islands of Remote Oceania, reaching as far as Samoa by 700 BCE.[133]

In the Americas, the Norte Chico culture emerged in coastal Peru around 3100 BCE.[134] The Norte Chico built public monumental architecture at the city of Caral, dated 2627–1977 BCE.[135][136] The later Chavín polity is sometimes described as the first Andean state.[137] It centred on the religious site at Chavín de Huantar, a place of pilgrimage and consumption of psychoactive substances.[138] Other important Andean cultures include the Moche, whose ceramics depict many aspects of daily life, and the Nazca, who created animal-shaped designs in the desert called Nazca lines.[139] The Olmecs of Mesoamerica developed by about 1200 BCE[140] and are known for the colossal stone heads that they carved from basalt.[141] They also devised the Mesoamerican calendar that was used by later cultures such as the Maya and Teotihuacan.[142] Societies in North America were primarily egalitarian hunter-gatherers, supplementing their diet with the plants of the Eastern Agricultural Complex.[143] They came together, seemingly voluntarily, to build earthworks such as Watson Brake (4000 BCE) and Poverty Point (3600 BCE), both in Louisiana.[144]

Axial Age

From 800–200 BCE,[145] the "Axial Age" saw the development of a set of transformative philosophical and religious ideas, mostly independently, in many different places.[146] Chinese Confucianism,[147] Indian Buddhism and Jainism,[148] and Jewish monotheism all developed during this period.[149] Persian Zoroastrianism began earlier, perhaps around 1000 BCE, but was institutionalized by the Achaemenid state during the Axial Age.[150] New philosophies took hold in Greece during the 5th century BCE, epitomized by thinkers such as Plato and Aristotle.[151]

Axial Age ideas were tremendously important for subsequent intellectual and religious history. Confucianism was one of the three schools of thought that came to dominate Chinese thinking, along with Taoism and Legalism.[152] The Confucian tradition, which would become particularly influential, looked for political morality not to the force of law but to the power and example of tradition.[153] Confucianism would later spread to Korea and Japan.[154] Buddhism reached China during the Han dynasty and spread widely, with 30,000 Buddhist temples in northern China alone by the 7th century CE.[155] Buddhism became the main religion in much of South, Southeast, and East Asia.[156] The Greek philosophical tradition[157] diffused throughout the Mediterranean world and as far as India, starting in the 4th century BCE after the conquests of Alexander the Great of Macedon.[158] The Christian and Muslim religions are both based on the Jewish idea of monotheism.[159]

Regional empires

The millennium from 500 BCE to 500 CE saw a series of empires of unprecedented size develop. Well-trained professional armies, unifying ideologies, and advanced bureaucracies created the possibility for emperors to rule over large domains whose populations could attain numbers upwards of tens of millions of subjects.[160] The great empires depended on military annexation of territory and on the formation of defended settlements to become agricultural centres. International trade expanded, most notably the massive trade routes in the Mediterranean Sea, the maritime trade web in the Indian Ocean,[161] and the Silk Road.[162]

There were a number of regional empires during this period. The kingdom of the Medes helped to destroy the Assyrian Empire in tandem with the nomadic Scythians and the Babylonians.[163] Nineveh, the capital of Assyria, was sacked by the Medes in 612 BCE.[164] The Median Empire gave way to successive Iranian empires, including the Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BCE),[165] the Parthian Empire (247 BCE–224 CE),[166][167] and the Sasanian Empire (224–651 CE).[167]

Several empires began in modern-day Greece. The Delian League, founded in 477 BCE,[168] and the Athenian Empire (454–404 BCE) were two such examples.[169] Later, Alexander the Great (356–323 BCE), of Macedon, founded an empire extending from present-day Greece to present-day India.[170][171] The empire divided shortly after his death, but resulted in the spread of Greek culture throughout conquered regions, a process referred to as Hellenization.[172] The Hellenistic period lasted from 323 to 31 BCE.[173]

In Asia, the Maurya Empire (322–185 BCE) existed in present-day India;[174] in the 3rd century BCE, most of South Asia was united to the Maurya Empire by Chandragupta Maurya and flourished under Ashoka the Great.[175] From the 4th to 6th centuries, the Gupta dynasty oversaw the period referred to as ancient India's Golden Age.[176] The ensuing stability contributed to heralding in an efflorescence of Hindu and Buddhist culture in the 4th and 5th centuries, as well as major advances in science and mathematics.[177] In South India, three prominent Dravidian kingdoms emerged: the Cheras,[178] Cholas,[179] and Pandyas.

In Europe, the Roman Empire, centred in present-day Italy, began in the 7th century BCE.[180] In the 3rd century BCE, the Roman Republic began expanding its territory through conquest and alliances.[181] By the time of Augustus (63 BCE–14 CE), the first Roman Emperor, Rome had already established dominion over most of the Mediterranean Sea.[182] The empire would continue to grow, controlling much of the land from England to Mesopotamia, reaching its greatest extent under Trajan (died 117 CE).[183] In the 4th century CE, the empire split into western and eastern regions, with (usually) separate emperors.[184] The Western Roman Empire would fall, in 476 CE, to German influence under Odoacer.[184] The Eastern Roman Empire, now known as the Byzantine Empire, with its capital at Constantinople, would continue for another thousand years until the city was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in 1453.[185] During most of its existence, the Byzantine Empire was one of the most powerful economic, cultural, and military forces in Europe,[186] and Constantinople is generally considered to be the centre of "Eastern Orthodox civilization".[187][188]

In China, the Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), the first imperial dynasty of China, was followed by the Han dynasty (202 BCE–220 CE).[189] The Han dynasty was comparable in power and influence to the Roman Empire that lay at the other end of the Silk Road.[190] Han China developed advanced cartography, shipbuilding, and navigation. The Chinese invented cast iron, and created finely wrought bronze figurines.[191] As with other empires during the classical period, Han China advanced significantly in the areas of government, education, mathematics, astronomy, technology, and many others.[192]

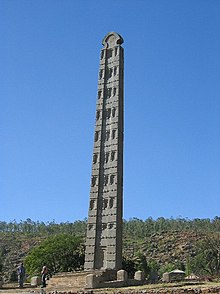

In Africa, the Kingdom of Aksum, centred in present-day Ethiopia, established itself by the 1st century CE as a major trading empire, dominating its neighbours in South Arabia and Kush and controlling the Red Sea trade.[193] It minted its own currency and carved enormous monolithic stelae to mark its emperors' graves.[194]

Successful regional empires were also established in the Americas, arising from cultures established as early as 2500 BCE.[195] In Mesoamerica, vast pre-Columbian societies were built, the most notable being the Zapotec civilization (700 BCE–1521 CE),[196] and the Maya civilization, which reached its highest state of development during the Mesoamerican classic period (c. 250–900 CE),[197] but continued throughout the post-classic period.[198] The great Maya city-states slowly rose in number and prominence, and Maya culture spread throughout the Yucatán and surrounding areas.[199] The Maya developed a writing system and were the first to use the concept of zero in their mathematics.[200] West of the Maya area, in central Mexico, the city of Teotihuacan grew based on its control of the obsidian trade.[201] Its power peaked around 450 CE, when its 125,000–150,000 inhabitants made it one of the world's largest cities.[202]

Technology developed sporadically in the ancient world.[203] There were periods of rapid technological progress, such as the Hellenistic period in the Mediterranean region, during which hundreds of technologies were invented.[204] There were also periods of technological decay, as during the Roman Empire's decline and fall and the ensuing early medieval period.[205] Two of the most important innovations were the stirrup (Central Asia, 1st century CE)[206] and paper (China, 1st and 2nd centuries CE),[207] both of which diffused widely throughout the world. The Chinese also learned to make silk and built massive engineering projects such as the Great Wall of China and the Grand Canal.[208] The Romans were also accomplished builders, inventing concrete and perfecting the use of arches in construction.[209]

Most ancient societies had slaves.[210] Slavery was particularly prevalent in Athens and Rome, where slaves made up a large proportion of the population and were foundational to the economy.[211]

Declines, falls, and resurgence

The ancient empires faced common problems associated with maintaining huge armies and supporting a central bureaucracy. These costs fell most heavily on the peasantry, while land-owning magnates increasingly evaded centralized control and its costs. Barbarian pressure on the frontiers hastened internal dissolution. China's Han dynasty fell into civil war in 220 CE, beginning the Three Kingdoms period, while its Roman counterpart became increasingly decentralized and divided about the same time in what is known as the Crisis of the Third Century.[212] From the Eurasian Steppe, horse-based nomads dominated a large part of the continent.[213] The development of the stirrup and the use of horse archers made the nomads a constant threat to sedentary civilizations.[214]

The gradual breakup of the Roman Empire coincided with the spread of Christianity outward from West Asia.[215] The Western Roman Empire fell under the domination of Germanic tribes in the 5th century,[216] and these polities gradually developed into a number of warring states, all associated in one way or another with the Catholic Church.[217] The remaining part of the Roman Empire, in the eastern Mediterranean, continued as what came to be called the Byzantine Empire.[218] Centuries later, a limited unity would be restored to Western Europe through the establishment in 962 of a revived "Roman Empire",[219] later called the Holy Roman Empire,[220] comprising a number of states in what is now Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Czechia, Belgium, Italy, and parts of France.[221][222]

In China, dynasties would rise and fall, but, by sharp contrast to the Mediterranean-European world, dynastic unity would be restored.[223] After the fall of the Eastern Han dynasty and the demise of the Three Kingdoms, nomadic tribes from the north began to invade, causing many Chinese people to flee southward.[224] The Sui dynasty successfully reunified the whole of China[225] in 581,[226] and laid the foundations for a Chinese golden age under the Tang dynasty (618–907).[227][228] China witnessed several collapses but each ended with imperial resurrection. These resurrections were not merely symbolic – as it was in the case of the various self-proclaimed heirs of the Roman Empire—but substantial, as far as political structure is concerned.[229]

Post-classical history (c. 500 CE – c. 1500 CE)

The term "post-classical era", though derived from the name of the era of "classical antiquity", takes in a broader geographic sweep.[230] The era is commonly dated from the 5th century fall of the Western Roman Empire, which fragmented into many separate kingdoms, some of which would later be confederated under the Holy Roman Empire. The Byzantine Empire survived until late in the post-classical or medieval period.

From the 10th to 13th centuries, the Medieval Warm Period in the northern hemisphere aided agriculture and led to population growth in parts of Europe and Asia.[231] It was followed by the Little Ice Age, which, along with the plagues of the 14th century, put downward pressure on the population of Eurasia.[231] Some of the major inventions of the period were gunpowder, printing, and the compass, all of which originated in China.[232]

The post-classical period encompasses the early Muslim conquests, the subsequent Islamic Golden Age, and the commencement and expansion of the Arab slave trade, followed by the Mongol invasions and the founding of the Ottoman Empire.[233] South Asia saw a series of middle kingdoms of India, followed by the establishment of Islamic empires in India.[234]

In West Africa, the Mali and Songhai Empires rose.[235] On the southeast coast of Africa, Arabic ports were established where gold, spices, and other commodities were traded. This allowed Africa to join the Southeast Asia trading system, bringing it contact with Asia; this, along with Muslim culture, resulted in the Swahili culture.[236]

China experienced the successive Sui, Tang, Song, Yuan, and early Ming dynasties.[237] Middle Eastern trade routes along the Indian Ocean, and the Silk Road through the Gobi Desert, provided limited economic and cultural contact between Asian and European civilizations.[203]

During the same period, civilizations in the Americas, such as the Mississippians,[238] Aztecs,[239] Maya,[240] and Inca reached their zenith.[241]

Greater Middle East

Prior to the advent of Islam in the 7th century, the Middle East was dominated by the Byzantine and Sasanian Empires that frequently fought each other for control of several disputed regions.[242] This was also a cultural battle, with Byzantine Christian culture competing against Persian Zoroastrian traditions.[243] The birth of Islam created a new contender that quickly surpassed both of these empires.[244] The new religion greatly affected the history of the Old World, especially the Middle East.[245]

From their centre on the Arabian Peninsula, Muslims began their expansion during the 7th century.[246] By 750 CE, they came to conquer most of the Middle East, North Africa, and parts of Europe,[247] ushering in an era of learning, science, and invention known as the Islamic Golden Age.[248] The knowledge and skills of the ancient Middle East, Greece, and Persia were preserved in the post-classical era by Muslims,[248] who also added new and important innovations from outside, such as the manufacture of paper from China[249] and decimal positional numbering from India.[250] Islamic civilization expanded both by conquest and on the basis of its merchant economy.[251] Merchants brought goods and their Islamic faith to China, India, Southeast Asia, and Africa.[252]

The crusading movement was a religiously motivated European effort to roll back Muslim territory and regain control of the Holy Land.[253] It was ultimately unsuccessful and served more to weaken the Byzantine Empire, especially with the sack of Constantinople in 1204.[254] Arab domination of the region ended in the mid-11th century with the arrival of the Seljuk Turks, migrating south from the Turkic homelands.[255] In the early 13th century, a new wave of invaders, the Mongols, swept through the region but were eventually eclipsed by the Turks and the founding of the Ottoman Empire in modern-day Turkey around 1280.[233]

North Africa saw the rise of polities established by the Berbers, such as Marinid Morocco, Zayyanid Algeria, and Hafsid Tunisia. [256] The coastal region was known to Europeans as the Barbary Coast. Pirates based in North African ports conducted operations that included capturing merchant ships and raiding coastal settlements.[257] Many European captives were sold in North African markets as part of the Barbary slave trade.[257]

Starting with the Sui dynasty (581–618), the Chinese began expanding to the west.[258] They were confronted by Turkic nomads, who were becoming the most dominant ethnic group in Central Asia.[259][260] Originally the relationship was largely cooperative but in 630, the Tang dynasty began an offensive against the Turks by capturing areas of the Ordos Desert.[261] In the 8th century, Islam began to penetrate the region and soon became the sole faith of most of the population, though Buddhism remained strong in the east.[262] The desert nomads of Arabia could militarily match the nomads of the steppe, and the Umayyad Caliphate gained control over parts of Central Asia.[259] The Hephthalites were the most powerful of the nomad groups in the 5th and 6th centuries, and controlled much of the region.[263] From the 9th to 13th centuries, the region was divided among several powerful states, including the Samanid Empire,[264] the Seljuk Empire,[265] and the Khwarazmian Empire. In 1370, Timur, a Turkic leader in the Mongol military tradition, conquered most of the region and founded the Timurid Empire.[266] However, Timur's large empire collapsed soon after his death,[267] which enabled the Uzbek Khanate to become the preeminent state in Central Asia.

In the aftermath of the Byzantine–Sasanian Wars, the Caucasus and its diverse group of peoples gained freedom from foreign suzerainty. As the Byzantines and Sasanians became exhausted due to continuous wars, the Rashidun Caliphate had the opportunity to expand into the Caucasus during the early Muslim conquests. In the 13th century, the arrival of the Mongols resulted in multiple invasions of the region.[268]

Europe

Since at least the 4th century, Christianity, primarily Catholicism,[269] and later Protestantism,[270][271] has played a prominent role in the shaping of Western civilization.[272][273][274] Europe during the Early Middle Ages was characterized by depopulation, deurbanization, and barbarian invasions, all of which had begun in late antiquity.[275] The barbarian invaders formed their own new kingdoms in the remains of the Western Roman Empire.[276] Although there were substantial changes in society and political structures, most of the new kingdoms incorporated existing Roman institutions.[277] Christianity expanded in Western Europe, and monasteries were founded.[278] In the 7th and 8th centuries, the Franks under the Carolingian dynasty established an empire covering much of Western Europe;[279] it lasted until the 9th century, when it succumbed to pressure from new invaders—the Vikings,[280] Magyars, and Arabs.[281]

During the High Middle Ages, which began after 1000, the population of Europe increased as technological and agricultural innovations allowed trade to flourish and crop yields to increase.[282] Manorialism, the organization of peasants into villages that owed rents and labor service to nobles, and feudalism, a political structure whereby knights and lower-status nobles owed military service to their overlords in return for the right to rents from lands and manors, were two of the ways of organizing medieval society that developed during the Middle Ages.[283] Kingdoms became more centralized after the decentralizing effects of the breakup of the Carolingian Empire.[284] In 1054, the Great Schism between the Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches led to the prominent cultural differences between Western and Eastern Europe.[285] The Crusades were a series of religious wars waged by Christians to wrest control of the Holy Land from the Muslims and succeeded for long enough to establish some Crusader states in the Levant.[286] Italian merchants imported slaves to work in households or in sugar processing.[287] Intellectual life was marked by scholasticism and the founding of universities, while the building of Gothic cathedrals and churches was one of the outstanding artistic achievements of the age.[288]

The Mongols reached Europe in 1236 and conquered Russia, along with briefly invading Poland and Hungary.[289] Lithuania cooperated with the Mongols but remained independent. It eventually formed a personal union with Poland in the late 14th century.[290]

The Late Middle Ages were marked by difficulties and calamities.[291] Famine, plague, and war devastated the population of Western Europe.[292] The Black Death alone killed approximately 75 to 200 million people between 1347 and 1350.[293][294] It was one of the deadliest pandemics in human history. Starting in Asia, the disease reached the Mediterranean and Western Europe during the late 1340s,[295] and killed tens of millions of Europeans in six years; between a quarter and a third of the population perished.[296]

The Middle Ages witnessed the first sustained urbanization of Northern and Western Europe and it lasted until the beginning of the early modern period in the 16th century,[297] marked by the rise of nation states,[298] the division of Western Christianity in the Reformation,[299] the birth of humanism in the Renaissance,[300] and the beginnings of European overseas expansion.[301]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Medieval sub-Saharan Africa was home to many different civilizations. In the Horn of Africa, the Kingdom of Aksum declined in the 7th century.[302] The Zagwe dynasty that later emerged was famed for its rock cut architecture at Lalibela. The Zagwe would then fall to the Solomonic dynasty who claimed descent from the Aksumite emperors[303] and would rule the country well into the 20th century. In the West African Sahel region, many Islamic empires rose, such as the Ghana, Mali, Songhai, and Kanem–Bornu Empires.[304] They controlled the trans-Saharan trade in gold, salt, and slaves.[305] West Africa became the world's largest gold exporter by the 14th century.[306]

South of the Sahel, civilizations rose in the coastal forests. These include the Yoruba city of Ifẹ, noted for its art,[307] and the Oyo Empire,[308] the Edo Kingdom of Benin centred in Benin City,[309] the Igbo Kingdom of Nri that produced advanced bronze art at Igbo-Ukwu,[310] and the Akan who are noted for their intricate architecture.[311]

Central Africa saw the formation of several states, including the Kingdom of Kongo.[312] In what is now modern Southern Africa, native Africans created various kingdoms such as the Kingdom of Mutapa. They flourished through trade with the Swahili on the East African coast.[313] They built large defensive stone structures without mortar such as Great Zimbabwe, capital of the Kingdom of Zimbabwe,[314] Khami, capital of the Kingdom of Butua,[315] and Danangombe (Dhlo-Dhlo), capital of the Rozvi Empire. The Swahili people themselves were the inhabitants of the East African coast from Kenya to Mozambique who traded extensively with Arabs, who introduced them to Islam.[316] They built many port cities such as Mombasa, Mogadishu, and Kilwa, which were known to Islamic geographers.[316]

Seafarers from Southeast Asia colonized Madagascar sometime between the 4th and 9th centuries,[317] creating what geographer Jared Diamond called "the single most astonishing fact of human geography".[318] To reach Madagascar, the settlers crossed 6,000 miles of ocean in sailing canoes,[319] probably without maps or compasses.[318] A wave of Bantu-speaking migrants from southeastern Africa also arrived in Madagascar around 1000 CE.[320]

South Asia

After the fall (550 CE) of the Gupta Empire, North India was divided into a complex and fluid network of smaller kingly states.[321] Early Muslim incursions began in the northwest in 711 CE, when the Arab Umayyad Caliphate conquered much of present-day Pakistan.[247] The Arab military advance was largely halted at that point, but Islam still spread in India, largely due to the influence of Arab merchants along the western coast.[236] The 9th century saw a Tripartite Struggle for control of North India, among the Pratihara, Pala, and Rashtrakuta Empires.

Post-classical dynasties in South India included those of the Chalukyas, Hoysalas, Cholas, and Mysores. Science, engineering, art, literature, astronomy, and philosophy flourished under the patronage of these kings.[322] Some of the other important states that emerged in South India during this time included the Bahmani Sultanate and Vijayanagara Empire.[323]

Northeast Asia

After a period of relative disunity, China was reunified by the Sui dynasty in 589[324] and under the succeeding Tang dynasty (618–907) China entered a Golden Age.[228] The Sui and Tang instituted the long-lasting imperial examination system, under which administrative positions were open only to those who passed an arduous test on Confucian thought and the Chinese classics.[325][326] China competed with Tibet (618–842) for control of areas in Inner and Central Asia.[327] The Tang dynasty eventually splintered, however, and after half a century of turmoil the Song dynasty reunified much of China,[328] when it was, according to William McNeill, the "richest, most skilled, and most populous country on earth".[329] Pressure from nomadic empires to the north became increasingly urgent.[330] By 1127, North China had been lost to the Jurchens in the Jin–Song Wars, and the Mongols conquered all of China in 1279.[331] After about a century of Mongol Yuan dynasty rule, the ethnic Chinese reasserted control with the founding of the Ming dynasty in 1368.[330]

In Japan, the imperial lineage had been established by this time, and during the Asuka period (538–710) the Yamato Province developed into a clearly centralized state.[332] Buddhism was introduced, and there was an emphasis on the adoption of elements of Chinese culture and Confucianism.[333] The Nara period of the 8th century was characterized by the appearance of a nascent literary culture, as well as the development of Buddhist-inspired artwork and architecture.[334][335] The Heian period (794 to 1185) saw the peak of imperial power, followed by the rise of militarized clans, and the beginning of Japanese feudalism.[336] The feudal period of Japanese history, dominated by powerful regional lords (daimyos) and the military rule of warlords (shoguns) such as the Ashikaga and Tokugawa shogunates, stretched from 1185 to 1868.[337][338] The emperor remained, but mostly as a figurehead, and the power of merchants was weak.

Postclassical Korea saw the end of the Three Kingdoms era, the three kingdoms being Goguryeo, Baekje, and Silla.[339] Silla conquered Baekje in 660, and Goguryeo in 668,[340] marking the beginning of the Northern and Southern States period, with Unified Silla in the south and Balhae, a successor state to Goguryeo, in the north.[341] In 892 CE, this arrangement reverted to the Later Three Kingdoms, with Goguryeo (then called Taebong and eventually named Goryeo) emerging as dominant, unifying the entire peninsula by 936.[342] The founding Goryeo dynasty ruled until 1392, succeeded by the Joseon dynasty,[343] which ruled for approximately 500 years.

In Mongolia, Genghis Khan united the various tribes under one banner.[296] The Mongol Empire expanded to comprise all of China and Central Asia, as well as large parts of Russia and the Middle East.[344] After Möngke Khan died in 1259,[345] the Mongol Empire was divided into four successor states.[268]

Southeast Asia

The Southeast Asian polity of Funan, which originated in the 2nd century CE, went into decline in the 6th century as Chinese trade routes shifted away from its ports.[346] It was replaced by the Khmer Empire in 802 CE.[347] The Khmers' capital city, Angkor, was the most extensive city in the world prior to the industrial age and contained Angkor Wat, the world's largest religious monument.[348][349] The Sukhothai (mid-13th century CE) and Ayutthaya Kingdoms (1351 CE) were major powers of the Thais, who were influenced by the Khmers.[350]

Starting in the 9th century, the Pagan Kingdom rose to prominence in modern Myanmar.[351] Its collapse brought about political fragmention that ended with the rise of the Toungoo Empire in the 16th century.[352] Other notable kingdoms of the period include Srivijaya[353] and Lavo (both coming into prominence in the 7th century), Champa[354] and Hariphunchai (both about 750),[355] Đại Việt (968),[356] Lan Na (13th century),[357] Majapahit (1293),[358] Lan Xang (1353),[359] and Ava (1365).[360]

This period saw the spread of Islam to present-day Indonesia (beginning in the 13th century)[361] and the emergence of the Malay states, including Brunei and Malacca.[362] In the Philippines, several polities were formed such as Tondo, Cebu, and Butuan.[363]

Oceania

In Oceania, the Tuʻi Tonga Empire was founded in the 10th century CE and expanded between 1250 and 1500.[364] Tongan culture, language, and hegemony spread widely throughout eastern Melanesia, Micronesia, and central Polynesia during this period,[365] influencing east 'Uvea, Rotuma, Futuna, Samoa, and Niue, as well as specific islands and parts of Micronesia (Kiribati, Pohnpei, and miscellaneous outliers), Vanuatu, and New Caledonia (specifically, the Loyalty Islands, with the main island being predominantly populated by the Melanesian Kanaks and their cultures).[366] In Northern Australia, there is evidence that Aboriginal Australians regularly traded with Makassan trepangers from Indonesia before the arrival of Europeans.[367][368]

At around the same time, a powerful thalassocracy appeared in eastern Polynesia, centred around the Society Islands, specifically on the sacred Taputapuatea marae, which drew in eastern Polynesian colonists from places as far away as Hawaii, New Zealand (Aotearoa), and the Tuamotu Islands for political, spiritual, and economic reasons, until the unexplained collapse of regular long-distance voyaging in the eastern Pacific a few centuries before Europeans began exploring the area.

The question of pre-Columbian contact between Polynesians and Native Americans has long been controversial.[369] In 2020, a genome-wide DNA analysis of Polynesians and Native South Americans shed new light on the debate by reporting evidence of intermingling between Polynesian people and pre-Columbian Zenú people around 1200 CE.[369] Whether this happened because of indigenous American people reaching eastern Polynesia or because the northern coast of South America was visited by Polynesians is not clear.[370]

Indigenous written records from this period are virtually nonexistent, as it seems that all Pacific Islanders, with the possible exception of the Rapa Nui and their currently undeciphered Rongorongo script, had no writing systems of any kind until after their introduction by European colonists. However, some indigenous prehistories can be estimated and academically reconstructed through careful, judicious analysis of native oral traditions, colonial ethnography, archaeology, physical anthropology, and linguistics research.

Americas

In North America, this period saw the rise of the Mississippian culture in the modern-day United States c. 950 CE,[371] marked by the extensive 11th-century urban complex at Cahokia.[372] The Ancestral Puebloans and their predecessors (9th – 13th centuries) built extensive permanent settlements, including stone structures that would remain the largest buildings in North America until the 19th century.[373]

In Mesoamerica, the Teotihuacan civilization fell and the classic Maya collapse occurred.[374] The Aztec Empire came to dominate much of Mesoamerica in the 14th and 15th centuries.[375]

In South America, the 15th century saw the rise of the Inca.[241] The Inca Empire or Tawantinsuyu, with its capital at Cusco, spanned the entire Andes, making it the most extensive pre-Columbian civilization.[376] The Inca were prosperous and advanced, known for an excellent road system and elegant stonework.[377]

Early modern period (c. 1500 CE – c. 1800 CE)

The "early modern period"[e] was the period between the Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution—roughly 1500 to 1800.[297] The early Modern period was characterized by the rise of science, and by increasingly rapid technological progress, secularized civic politics, and the nation state.

Capitalist economies began their rise, initially in the northern Italian republics. The early modern period saw the rise and dominance of mercantilist economic theory, and the decline and eventual disappearance, in much of the European sphere, of feudalism, serfdom, and the power of the Catholic Church.

The period included the Reformation, the Thirty Years' War, the Age of Discovery, European colonial expansion, the peak of European witch-hunting, the Scientific Revolution, and the Age of Enlightenment.[f] During the early modern period, Protestantism eventually became the majority faith throughout Northwestern Europe and in England and English-speaking America.[378]

European expansion

During this period, European powers came to dominate most of the world. Though Europe's most developed regions were more urbanized than any other region of the world, European civilization had gone through a long period of gradual decline and collapse. During the early modern period, Europe was able to regain its dominance; historians still debate the causes.[379]

The 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries saw the rise of maritime European empires, first the Portuguese and Spanish Empires, later the French, English, and Dutch Empires. In the 17th century, private chartered companies were established, such as the English East India Company (founded 1600) – often described as the first multinational corporation – and the Dutch East India Company (founded 1602).[380]

The Age of Discovery was the first period in which Eurasia and Africa engaged in substantial cultural, material, and biologic exchange with the New World. It began in the late 15th century, when the two kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula – Portugal and Castile – sent the first exploratory voyages around the Cape of Good Hope and to the Americas, the latter "discovered" in 1492 by Christopher Columbus.[381] Shortly before the turn of the 16th century, the Portuguese started establishing factories ranging from Africa to Asia and Brazil, for trade in local commodities such as slaves, gold, spices, and lumber. In 1500, Portugal established an international business centre under a royal monopoly, the House of India.[382]

Global integration continued as European colonization of the Americas initiated the Columbian exchange:[383] the exchange of plants, animals, foods, human populations (including slaves), communicable diseases, and culture between the Eastern and Western Hemispheres.[384] It was one of history's most important global events, involving ecology and agriculture.[385] New crops brought from the Americas by 16th-century European seafarers substantially contributed to world population growth.[386]

Regional developments

Greater Middle East

After conquering Constantinople in 1453, the Ottoman Empire quickly came to dominate the Middle East.[387] Persia came under the rule of the Safavids in 1501,[388] succeeded by the Afshars in 1736, the Zands in 1751, and the Qajars in 1794.[389] In North Africa, the Berbers remained in control of independent states until the 16th century.[390] Areas to the north and east in Central Asia were held by the Uzbeks and Pashtuns. At the start of the 19th century, the Russian Empire began its conquest of the Caucasus.

Europe

Europe's Renaissance – the "rebirth" of classical culture, beginning in Italy in the 14th century and extending into the 16th – comprised the rediscovery of the classical world's cultural, scientific, and technological achievements, and the economic and social rise of Europe.[391] The Renaissance engendered a culture of inquisitiveness which ultimately led to humanism[392] and the Scientific Revolution.[393] This period is also celebrated for its artistic and literary attainments.[394] Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy, Geoffrey Chaucer's Canterbury Tales, and the paintings and sculptures of Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo are some of the great works of the era.[395]

In Russia, Ivan the Terrible was crowned in 1547 as the first tsar of Russia, and by annexing the Turkic khanates in the east, transformed Russia into a regional power.[396] The countries of Western Europe, while expanding prodigiously through technological advancement and colonial conquest, competed with each other economically and militarily in a state of almost constant war. Often the wars had a religious dimension, either Catholic versus Protestant (primarily in Western Europe) or Christian versus Muslim (primarily in Eastern Europe), although religious tolerance was in turn encouraged in countries like the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, legally guaranteeing it since the Warsaw Confederation in 1573. Wars of particular note include the Thirty Years' War, the War of the Spanish Succession, the Seven Years' War, and the French Revolutionary Wars.[397] Napoleon Bonaparte came to power in France in 1799, an event foreshadowing the Napoleonic Wars of the early 19th century.[398]

Sub-Saharan Africa

In Africa, this period saw a decline in many civilizations and an advancement in others. The Swahili Coast declined after coming under the control of the Portuguese and later the Omanis. In West Africa, the Songhai Empire fell after an invasion by the Moroccans.[399] Bonoman gave birth to numerous Akan states such as Akwamu, Akyem, Fante, and Adansi, among others.[400] The Kingdom of Zimbabwe gave way to smaller kingdoms such as Mutapa,[401] Butua,[402] and Rozvi.[403]

The Ethiopian Empire suffered from the 1531 invasion by the neighboring Muslim Adal Sultanate, and in 1769 entered the Zemene Mesafint (Age of Princes) during which the Emperor became a figurehead and the country was ruled by warlords, though the royal line later would recover under Emperor Tewodros II. In the Horn of Africa, the Ajuran Sultanate began to decline in the 17th century, and was succeeded by the Geledi Sultanate. Other civilizations in Africa advanced during this period. The Oyo Empire experienced its golden age,[404] as did the Kingdom of Benin. The Ashanti Empire rose to power in what is modern day Ghana in 1670. The Kingdom of Kongo also thrived during this period.[405]

South Asia

In the Indian subcontinent, the Mughal Empire began under Babur in 1526 and lasted for two centuries.[406] Starting in the northwest, the Mughal Empire would come to rule the entire subcontinent by the late 17th century,[407] except for the southernmost Indian provinces, which would remain independent.

Against the Muslim Mughal Empire, the Hindu Maratha Empire was founded by Shivaji on the western coast in 1674.[408] The Marathas gradually gained territory from the Mughals over several decades, particularly in the Mughal–Maratha Wars (1680–1707).[409] The Maratha Empire would fall under the control of the British East India Company in 1818, with all former Maratha and Mughal authority devolving to the British Raj in 1858.[410]

During the same period, Sikhism developed from the spiritual teachings of ten gurus.[411] In 1799, Ranjit Singh established the Sikh Empire in the Punjab. The Sikh Empire would be annexed by the British East India Company in 1849.

Northeast Asia

In 1644, the Ming gave way to the Qing,[412] the last Chinese imperial dynasty, which would rule until 1912.[413] Japan experienced its Azuchi–Momoyama period (1568–1600), followed by the Edo period (1600–1868).[414] The Korean Joseon dynasty (1392–1910) ruled throughout this period, successfully repelling invasions from Japan and China in the 16th and 17th centuries. Expanded maritime trade with Europe significantly affected China and Japan during this period, particularly by the Portuguese who had a presence in Macau and Nagasaki. However, China and Japan would later pursue isolationist policies designed to eliminate foreign influences.

Southeast Asia

In 1511, the Portuguese overthrew the Malacca Sultanate in present-day Malaysia and Indonesian Sumatra.[415] The Portuguese held this important trading territory (and the valuable associated navigational strait) until overthrown by the Dutch in 1641.[380] The Johor Sultanate, centred on the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, became the dominant trading power in the region.[416]

European colonization expanded with the Dutch in Indonesia, the Portuguese in Timor, and the Spanish in the Philippines.[417] Into the 19th century, European expansion would affect the whole of Southeast Asia, with the British in Myanmar and Malaysia, and the French in Indochina.[418] Only Thailand would successfully resist colonization.[418]

Oceania

The Pacific islands of Oceania would also be affected by European contact, starting with the circumnavigational voyage of Ferdinand Magellan (1519–1522),[g] who landed in the Marianas and other islands. Abel Tasman (1642–1644) sailed to present-day Australia, New Zealand, and nearby islands. James Cook (1768–1779) made the first recorded European contact with Hawaii. In 1788, Britain founded its first colony in Australia.[419]

Americas

In the Americas, several European powers vigorously colonized the newly discovered continents, largely displacing the indigenous populations, and destroying the advanced civilizations of the Aztecs and Incas. Diseases introduced by Europeans devastated American societies, killing 60–90 million people by 1600 and reducing the population by 90–95%.[420] Spain, Portugal, Britain, and France all made extensive territorial claims, and undertook large-scale settlement, including the importation of large numbers of African slaves. Portugal claimed Brazil.[421] Spain claimed the rest of South America, Mesoamerica, and southern North America.[421] The Spanish mined and exported prodigious amounts of silver from the Americas.[422] This American silver boom, along with an increase in Japanese silver mining, caused a surge in inflation known as the price revolution in the 16th and 17th centuries.[423]

Britain colonized the east coast of North America, and France colonized the central region of North America. Russia made incursions onto the northwest coast of North America, with a first colony in present-day Alaska in 1784, and the outpost of Fort Ross in present-day California in 1812.[424] In 1762, in the midst of the Seven Years' War, France secretly ceded most of its North American claims to Spain in the Treaty of Fontainebleau. Thirteen of the British colonies declared independence as the United States of America in 1776, ratified by the Treaty of Paris in 1783, ending the American Revolutionary War.[425] Napoleon won France's claims back from Spain in 1800, but sold them to the United States in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803.[426]

Late modern period (c. 1800 CE – present)

19th century

The Scientific Revolution changed humanity's understanding of the world and was followed by the Industrial Revolution, a major transformation of the world's economies.[427] The Scientific Revolution in the 17th century had little immediate effect on industrial technology;[427] only in the second half of the 19th century did scientific advances begin to be applied substantially to practical invention.[428] The Industrial Revolution began in Great Britain and used new modes of production—the factory, mass production, and mechanization—to manufacture a wide array of goods faster and using less labor than previously required.[429]

European empires lost territory in Latin America, which won independence by the 1820s, but expanded elsewhere.[430] Britain gained control of the Indian subcontinent, Burma, and the Malay Peninsula; the French took Indochina; while the Dutch cemented their control over the Dutch East Indies.[418] The British also colonized Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa with large numbers of British colonists emigrating to these colonies. Russia colonized large pre-agricultural areas of Siberia. In the late 19th century, the European powers divided the remaining areas of Africa.[431] Only Ethiopia and Liberia remained independent.[431] Within Europe, economic and military challenges created a system of nation states, and ethno-cultural groupings began to identify themselves as distinctive nations with aspirations for cultural and political autonomy.[432] This nationalism would become important to peoples across the world in the 20th century.[433]

In response to the encroachment of European powers, several countries undertook programs of industrialization and political reform along Western lines.[434] The Meiji Restoration in Japan was successful and led to the establishment of a colonial empire, while the tanzimat reforms in the Ottoman Empire did little to slow Ottoman decline.[435] China achieved some success with its Self-Strengthening Movement, but was devastated by the Taiping Rebellion, history's bloodiest civil war, which killed 20–30 million people between 1850 and 1864.[436][437]

The United States developed to become the world's largest economy by the end of the century, and acquired an empire of its own.[438] During the Second Industrial Revolution, a new set of technological advances including electrical power, the internal combustion engine, and assembly line manufacturing increased productivity once again.[439] Meanwhile, industrial pollution and environmental damage, present since the discovery of fire and the beginning of civilization, accelerated drastically.[440]

20th century

The 20th century opened with Europe at an apex of wealth and power,[441] and with much of the world under its direct colonial control or its indirect domination.[442] Much of the rest of the world was influenced by heavily Europeanized nations: the United States and Japan.[442] As the century unfolded, however, the global system dominated by rival powers was subjected to severe strains, and ultimately yielded to a more fluid structure of independent nation states.[443]

This transformation was catalyzed by wars of unparalleled scope and devastation. World War I led to the collapse of four empires – the Austro-Hungarian, German, Ottoman, and Russian Empires[444] – and weakened the United Kingdom and France. The Armenian, Assyrian, and Greek genocides were the systematic destruction, mass murder, and expulsion during World War I of the Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks in the Ottoman Empire, spearheaded by the ruling Committee of Union and Progress (CUP).[445][446]

In the war's aftermath, powerful ideologies rose to prominence. The Russian Revolution of 1917 created the first communist state,[447] while the 1920s and 1930s saw militaristic fascist dictatorships gain control in Italy,[448] Germany,[448] Spain, and elsewhere. From 1918 to 1920, the Spanish flu caused the deaths of at least 25 million people.[449]

Ongoing national rivalries, exacerbated by the economic turmoil of the Great Depression, helped precipitate World War II. In the war, the vast majority of the world's countries, including all of the great powers, fought as part of two opposing military alliances: the Allies and the Axis. The leading Axis powers were Germany, Japan, and Italy; while the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union, and the Republic of China were the "Big Four" Allied powers.[450]

The militaristic dictatorships of Europe and Japan pursued an ultimately doomed course of imperialist expansionism, in the course of which Germany, under Adolf Hitler, orchestrated the genocide of six million Jews in the Holocaust,[451] while Japan murdered millions of Chinese.[452]

The defeat of the Axis by the Allies in World War II opened the way for the advance of communism into Eastern Europe, China, North Korea, North Vietnam, and Cuba.[453]

When World War II ended in 1945, the United Nations was founded in the hope of preventing future wars,[454] as the League of Nations had been formed following World War I.[455]

World War II had left two countries, the United States and the Soviet Union, with principal power to influence international affairs.[456] Each was suspicious of the other and feared a global spread of the other's, respectively capitalist and communist, political-economic model. This led to the Cold War, a 45-year stand-off and arms race between the United States and its allies, on one hand, and the Soviet Union and its allies on the other.[457]

With the development of nuclear weapons during World War II and their subsequent proliferation, all of humanity was put at risk of nuclear war between the two superpowers, as demonstrated by many incidents, most prominently the October 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.[458] Such war being viewed as impractical, the superpowers instead waged proxy wars in non-nuclear-armed Third World countries.[459][460] Between 1969 and 1972, as part of the Cold War Space Race, twelve American astronauts landed on the Moon and safely returned to Earth.[461]

In China, Mao Zedong implemented industrialization and collectivization reforms as part of the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962), leading to the starvation deaths (1959–1961) of 30–40 million people.[462] After Mao's death, China entered a period of economic liberalization and rapid growth, with the economy expanding by 6.6% per year from 1978 to 2003.[463]

The Cold War ended peacefully in 1991 after the Soviet Union collapsed,[464] partly due to its inability to compete economically with the United States and Western Europe. The United States likewise began to show signs of slippage in its geopolitical influence,[465][466] and its economic inequality increased.[467][468]

In the early postwar decades, the colonies in Asia and Africa of the Belgian, British, Dutch, French, and other European empires won their formal independence.[469] Most Western European and Central European countries gradually formed a political and economic community, the European Union, which expanded eastward to include former Soviet satellite states.[470]

Cold War preparations to deter or to fight a third world war accelerated advances in technologies that, though conceptualized before World War II, had been implemented for that war's exigencies, such as jet aircraft,[471] rocketry,[472] and computers.[473] In the decades after World War II, these advances led to jet travel;[471] artificial satellites with innumerable applications,[474] including GPS; [475] and the Internet,[474] which in the 1990s began to gain traction as a form of communication.[476] These inventions have revolutionized the movement of people, ideas, and information.[477]

However, not all scientific and technological advances in the second half of the 20th century required an initial military impetus. That period also saw ground-breaking developments such as the discovery of the structure of DNA[478] and DNA sequencing,[479] the worldwide eradication of smallpox,[480] the Green Revolution in agriculture,[481] the introduction of the portable cellular phone,[482] the discovery of plate tectonics,[483] crewed and uncrewed exploration of space,[484] and foundational discoveries in physics phenomena ranging from the smallest entities (particle physics) to the greatest entity (physical cosmology).[483]

21st century

The 21st century has seen the expansion of communications with smartphones becoming ubiquitous since the late 2000s and the Internet, which have caused fundamental societal changes in business, politics, and individuals' personal lives.[485]

This period has been marked by growing economic globalization and integration,[486] with consequent increased risk to interlinked economies, as exemplified by the Great Recession of the late 2000s and early 2010s.[487]

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic substantially disrupted global trading and caused recessions in the global economy.[488] As of 2023, more than six million people have died from COVID-19.[489]

Humankind's adverse effects on the Earth have risen due to growing human populations and industrialization.[490] The increased demands on Earth's resources – and failure to implement large-scale use of renewable energy, chiefly via solar thermal collectors and wind turbines – are contributing to environmental degradation, including mass extinctions of plant and animal species, and climate change, which threatens the long-term survival of humankind.[491][492]

References

Explanatory notes

- ^ This date comes from the 2015 discovery of stone tools at the Lomekwi site in Kenya.[9] Some palaeontologists propose an earlier date of 3.39 million years ago based on bones found with butchery marks on them in Dikika, Ethiopia,[10] while others dispute both the Dikika and Lomekwi findings.[11]

- ^ Or perhaps earlier; the 2018 discovery of stone tools from 2.1 million years ago in Shangchen, China predates the earliest known H. erectus fossils.[19]

- ^ These dates come from a 2018 study of an upper jawbone from Misliya Cave, Israel.[39] Researchers studying a fossil skull from Apidima Cave, Greece in 2019 proposed an earlier date of 210,000 years ago.[40] The Apidima Cave study has been challenged by other scholars.[41]

- ^ This occurred during the African humid period, when the Sahara was much wetter than it is today.[58]

- ^ "Early Modern", historically speaking, refers to Western European history from 1501 (after the widely accepted end of the Late Middle Ages; the transition period was the 15th century) to either 1750 or c. 1790–1800, by whichever epoch is favoured by a school of scholars defining the period—which, in many cases of periodization, differs as well within a discipline such as art, philosophy, or history.

- ^ The Age of Enlightenment has also been referred to as the Age of Reason. Historians also include the late 17th century, which is typically known as the Age of Reason or Age of Rationalism, as part of the Enlightenment; however, contemporary historians have considered the Age of Reason distinct to the ideas developed in the Enlightenment. The use of the term here includes both Ages under a single all-inclusive time-frame.

- ^ Magellan died in 1521. The voyage was completed by Spanish navigator Juan Sebastián Elcano in 1522.

- ^ BritainFranceSpainPortugalNetherlandsGermanyOttoman EmpireBelgiumRussiaJapanQing EmpireAustro-HungaryDenmarkSweden-NorwayUSAItalyFree nations

Citations

- ^ "International Programs – Historical Estimates of World Population – U.S. Census Bureau". United States Census Bureau. August 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- ^ Bulliet et al. 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Arnason U, Gullberg A, Janke A (December 1998). "Molecular timing of primate divergences as estimated by two nonprimate calibration points". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 47 (6): 718–727. Bibcode:1998JMolE..47..718A. doi:10.1007/PL00006431. PMID 9847414. S2CID 22217997.

Consistent with the marked shift in the dating of the Cercopithecoidea/Hominoidea split, all hominoid divergences receive a much earlier dating. Thus the estimated date of the divergence between Pan (chimpanzee) and Homo is 10–13 MYBP and that between Gorilla and the Pan/Homo linage ≈17 MYBP.

- ^ Moorjani, Priya; Amorim, Carlos Eduardo G.; Arndt, Peter F.; Przeworski, Molly (2016). "Variation in the molecular clock of primates". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 113 (38): 10607–10612. Bibcode:2016PNAS..11310607M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1600374113. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5035889. PMID 27601674.

Taking this approach, we estimate the human and chimpanzee divergence time is 12.1 million years, and the human and gorilla divergence time is 15.1 million years.

- ^ Patterson N, Richter DJ, Gnerre S, Lander ES, Reich D (June 2006). "Genetic evidence for complex speciation of humans and chimpanzees". Nature. 441 (7097): 1106. Bibcode:2006Natur.441.1103P. doi:10.1038/nature04789. PMID 16710306. S2CID 2325560.

On the basis of the relative genetic divergence of human and chimpanzee (Supplementary Tables 7 and 8; Supplementary Note 9), we infer tgenome < 7.6 Myr ago and, from the bound tspecies < 0.835tgenome, we can infer that tspecies < 6.3 Myr ago. Using a more realistic estimate of human–orangutan genome divergence of less than 17 Myr ago, we obtain a younger bound of tspecies < 5.4 Myr ago.

- ^ Dunbar 2016, p. 8. "Conventionally, taxonomists now refer to the great ape family (including humans) as hominids, while all members of the lineage leading to modern humans that arose after the split with the [Homo-Pan] LCA are referred to as hominins. The older literature used the terms hominoids and hominids respectively."

- ^ a b Cela-Conde, C. J.; Ayala, F. J. (2003). "Genera of the human lineage". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 100 (13): 7684–7689. Bibcode:2003PNAS..100.7684C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0832372100. PMC 164648. PMID 12794185.

Only two or three hominid genera, Australopithecus, Paranthropus, and Homo, had been previously accepted, with Paranthropus considered a subgenus of Australopithecus by some authors.

- ^ Dunbar 2016, pp. 8, 10.

- ^ Harmand, Sonia; et al. (2015). "3.3-million-year-old stone tools from Lomekwi 3, West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 521 (7552): 310–315. Bibcode:2015Natur.521..310H. doi:10.1038/nature14464. PMID 25993961. S2CID 1207285. Archived from the original on 9 October 2021. Retrieved 27 July 2022.

- ^ McPherron, Shannon P.; Alemseged, Zeresenay; Marean, Curtis W.; Wynn, Jonathan G.; Reed, Denné; Geraads, Denis; Bobe, René; Béarat, Hamdallah A. (August 2010). "Evidence for stone-tool-assisted consumption of animal tissues before 3.39 million years ago at Dikika, Ethiopia". Nature. 466 (7308): 857–860. Bibcode:2010Natur.466..857M. doi:10.1038/nature09248. PMID 20703305. S2CID 4356816.

- ^ Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Alcalá, L. (2016). "3.3-Million-Year-Old Stone Tools and Butchery Traces? More Evidence Needed". PaleoAnthropology: 46–53. Archived from the original on 15 September 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2022.

- ^ de la Torre, I. (2019). "Searching for the emergence of stone tool making in eastern Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 116 (24): 11567–11569. Bibcode:2019PNAS..11611567D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1906926116. PMC 6575166. PMID 31164417.

- ^ Stutz, Aaron Jonas (2018). "Paleolithic". In Trevathan, Wenda; Cartmill, Matt; Dufour, Darna; Larsen, Clark (eds.). The International Encyclopedia of Biological Anthropology. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1002/9781118584538.ieba0363. ISBN 978-1-118-58442-2. S2CID 240083827. Archived from the original on 1 August 2022. Retrieved 1 August 2022.

- ^ Strait DS (September 2010). "The Evolutionary History of the Australopiths". Evolution: Education and Outreach. 3 (3): 341–352. doi:10.1007/s12052-010-0249-6. ISSN 1936-6434. S2CID 31979188.

- ^ Kimbel WH, Villmoare B (July 2016). "From Australopithecus to Homo: the transition that wasn't". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences. 371 (1698): 20150248. doi:10.1098/rstb.2015.0248. PMC 4920303. PMID 27298460. S2CID 20267830.