Saint Patrick

Patrick | |

|---|---|

Stained-glass window of St. Patrick from Saint Patrick Catholic Church, Junction City, Ohio, United States | |

| |

| Born | Roman or sub-Roman Britain |

| Died | mid-fifth to early-sixth century Ireland |

| Venerated in | |

| Major shrine | |

| Feast | 17 March (Saint Patrick's Day) |

| Attributes | Crozier, mitre, holding a shamrock, carrying a cross, repelling serpents, harp |

| Patronage | Ireland, Nigeria, Montserrat, Archdiocese of New York, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Newark, Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles, Boston, Rolla, Missouri, Loíza, Puerto Rico, Murcia (Spain), Clann Giolla Phádraig, engineers, paralegals, Archdiocese of Melbourne; invoked against snakes, sins[1] |

Saint Patrick (Latin: Patricius; Irish: Pádraig [ˈpˠɑːɾˠɪɟ] or [ˈpˠaːd̪ˠɾˠəɟ]; Welsh: Padrig) was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, the other patron saints being Brigid of Kildare and Columba. Patrick was never formally canonised by the Catholic Church,[2] having lived before the current laws it established for such matters. He is venerated as a saint in the Catholic Church, the Lutheran Church, the Church of Ireland (part of the Anglican Communion), and in the Eastern Orthodox Church, where he is regarded as equal-to-the-apostles and Enlightener of Ireland.[3][4]

The dates of Patrick's life cannot be fixed with certainty, but there is general agreement that he was active as a missionary in Ireland during the fifth century. A recent biography[5] on Patrick shows a late fourth-century date for the saint is not impossible.[6] According to tradition dating from the early Middle Ages, Patrick was the first bishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland, and is credited with bringing Christianity to Ireland, converting a pagan society in the process. He has been generally so regarded ever since, despite evidence of some earlier Christian presence.[7]

According to Patrick's autobiographical Confessio, when he was about sixteen, he was captured by Irish pirates from his home in Britain and taken as a slave to Ireland. He writes that he lived there for six years as an animal herder before escaping and returning to his family. After becoming a cleric, he returned to spread Christianity in northern and western Ireland. In later life, he served as a bishop, but little is known about where he worked. By the seventh century, he had already come to be revered as the patron saint of Ireland.

Saint Patrick's Day, considered his feast day, is observed on 17 March, the supposed date of his death. It is celebrated in Ireland and among the Irish diaspora as a religious and cultural holiday. In the Catholic Church in Ireland, it is both a solemnity and a holy day of obligation.

Sources

Two Latin works survive which are generally accepted as having been written by St. Patrick. These are the Declaration (Latin: Confessio)[8] and the Letter to the soldiers of Coroticus (Latin: Epistola),[9] from which come the only generally accepted details of his life.[10] The Declaration is the more biographical of the two. In it, Patrick gives a short account of his life and his mission. Most available details of his life are from subsequent hagiographies and annals, which have considerable value but lack the empiricism scholars depend on today.[11]

Name

The only name that Patrick uses for himself in his own writings is Pātricius [paːˈtrɪ.ki.ʊs], which gives Old Irish: Pátraic [ˈpˠaːd̪ˠɾˠəɟ] and Irish: Pádraig ([ˈpˠaːd̪ˠɾˠəɟ] or [ˈpˠɑːɾˠɪɟ]); English Patrick; Scottish Gaelic: Pàdraig; Welsh: Padrig; Cornish: Petroc.

Hagiography records other names he is said to have borne. Tírechán's seventh-century Collectanea gives: "Magonus, that is, famous; Succetus, that is, god of war; Patricius, that is, father of the citizens; Cothirthiacus, because he served four houses of druids."[12] "Magonus" appears in the ninth-century Historia Brittonum as Maun, descending from British *Magunos, meaning "servant-lad".[12] "Succetus", which also appears in Muirchú moccu Machtheni's seventh-century Life as Sochet,[12] is identified by Mac Neill as "a word of British origin meaning swineherd".[13] Cothirthiacus also appears as Cothraige in the 8th-century biographical poem known as Fiacc's Hymn and a variety of other spellings elsewhere, and is taken to represent a Primitive Irish: *Qatrikias, although this is disputed. Harvey argues that Cothraige "has the form of a classic Old Irish tribal (and therefore place-) name", noting that Ail Coithrigi is a name for the Rock of Cashel, and the place-names Cothrugu and Catrige are attested in Counties Antrim and Carlow.[14]

Dating

The dates of Patrick's life are uncertain; there are conflicting traditions regarding the year of his death. His own writings provide no evidence for any dating more precise than the 5th century generally. His Biblical quotations are a mixture of the Old Latin version and the Vulgate, completed in the early 5th century, suggesting he was writing "at the point of transition from Old Latin to Vulgate",[15] although it is possible the Vulgate readings may have been added later, replacing earlier readings.[16] The Letter to Coroticus implies that the Franks were still pagans at the time of writing:[17] their conversion to Christianity is dated to the period 496–508.[18]

The Irish annals date Patrick's arrival in Ireland at 432, but they were compiled in the mid-6th century at the earliest.[17] The date 432 was probably chosen to minimise the contribution of Palladius, who was known to have been sent to Ireland in 431, and maximise that of Patrick.[19] A variety of dates are given for his death. In 457 "the elder Patrick" (Irish: Patraic Sen) is said to have died: this may refer to the death of Palladius, who according to the Book of Armagh was also called Patrick.[19] In 461/2 the annals say that "Here some record the repose of Patrick";[20]: 19 in 492/3 they record the death of "Patrick, the arch-apostle (or archbishop and apostle) of the Scoti", on 17 March, at the age of 120.[20]: 31

While some modern historians[21] accept the earlier date of c. 460 for Patrick's death, scholars of early Irish history tend to prefer a later date, c. 493. Supporting the later date, the annals record that in 553 "the relics of Patrick were placed sixty years after his death in a shrine by Colum Cille" (emphasis added).[22] The death of Patrick's disciple Mochta is dated in the annals to 535 or 537,[22][23] and the early hagiographies "all bring Patrick into contact with persons whose obits occur at the end of the fifth century or the beginning of the sixth".[24] However, E. A. Thompson argues that none of the dates given for Patrick's death in the Annals are reliable.[25] A recent biography argues that a late fifth-century date for the saint is not impossible.[26]: 34–35

Life

Patrick was born at the end of Roman rule in Britain. His birthplace is not known with any certainty; some traditions place it in what is now England—one identifying it as Glannoventa (modern Ravenglass in Cumbria). In 1981, Thomas argued at length for the areas of Birdoswald, twenty miles (32 km) east of Carlisle on Hadrian's Wall. Thomas 1981, pp. 310–14. In 1993, Paor glossed it as "[probably near] Carlisle". There is a Roman town known as Bannaventa in Northamptonshire, which is phonically similar to the Bannavem Taburniae mentioned in Patrick's confession, but this is probably too far from the sea.[27] Claims have also been advanced for locations in present-day Scotland, with the Catholic Encyclopedia stating that Patrick was born in Kilpatrick, Scotland.[28] In 1926 Eoin MacNeill also advanced a claim for Glamorgan in south Wales,[29] possibly the village of Banwen, in the Upper Dulais Valley, which was the location of a Roman marching camp.[30]

Patrick's father, Calpurnius, is described as a decurion (Senator and tax collector) of an unspecified Romano-British city, and as a deacon; his grandfather Potitus was a priest from Bonaven Tabernia.[31] However, Patrick's confession states he was not an active believer in his youth, and considered himself in that period to be "idle and callow".[32]

According to the Confession of Saint Patrick, at the age of sixteen, he was captured by a group of Irish pirates, from his family's Villa at "Bannavem Taburniae".[33] They took him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years. Patrick writes in the Confession[33] that the time he spent in captivity was critical to his spiritual development. He explains that the Lord had mercy on his youth and ignorance, and afforded him the opportunity to be forgiven his sins and to grow in his faith through prayer.

The Dál Riata raiders who kidnapped him introduced him to the Irish culture that would define his life and reputation.[32] While in captivity, he worked as a shepherd and strengthened his relationship with God through prayer, eventually leading him to deepen his faith.[33]

After six years of captivity, he heard a voice telling him that he would soon go home, and then that his ship was ready. Fleeing his master, he travelled to a port, two hundred miles away,[34] where he found a ship and with difficulty persuaded the captain to take him. After three days' sailing, they landed, presumably in Britain, and apparently all left the ship, walking for 28 days in a "wilderness" and becoming faint from hunger. Patrick's account of his escape from slavery and return home to Britain is recounted in his Declaration.[35] After Patrick prayed for sustenance, they encountered a herd of wild boar;[36] since this was shortly after Patrick had urged them to put their faith in God, his prestige in the group was greatly increased. After various adventures, he returned home to his family, now in his early twenties.[37] After returning home to Britain, Patrick continued to study Christianity.

Patrick recounts that he had a vision a few years after returning home:

I saw a man coming, as it were from Ireland. His name was Victoricus, and he carried many letters, and he gave me one of them. I read the heading: "The Voice of the Irish". As I began the letter, I imagined in that moment that I heard the voice of those very people who were near the wood of Foclut, which is beside the western sea—and they cried out, as with one voice: "We appeal to you, holy servant boy, to come and walk among us."[38]

A.B.E. Hood suggests that the Victoricus of St. Patrick's vision may be identified with Saint Victricius, bishop of Rouen in the late fourth century, who had visited Britain in an official capacity in 396.[39] However, Ludwig Bieler disagrees.[40]

Patrick studied in Europe principally at Auxerre. J. B. Bury suggests that Amator ordained Patrick to the diaconate at Auxerre.[41] Patrick is thought to have visited the Marmoutier Abbey, Tours and to have received the tonsure at Lérins Abbey. Saint Germanus of Auxerre, a bishop of the Western Church, ordained him to the priesthood.[42] Maximus of Turin is credited with consecrating him as bishop.[43]

Acting on his vision, Patrick returned to Ireland as a Christian missionary.[33] According to Bury, his landing place was Wicklow, County Wicklow, at the mouth of the river Inver-dea, which is now called the Vartry.[44] Bury suggests that Wicklow was also the port through which Patrick made his escape after his six years' captivity, though he offers only circumstantial evidence to support this.[45] Tradition has it that Patrick was not welcomed by the locals and was forced to leave and seek a more welcoming landing place further north. He rested for some days at the islands off the Skerries coast, one of which still retains the name of Inis-Patrick. The first sanctuary dedicated by Patrick was at Saul. Shortly thereafter Benin (or Benignus), son of the chieftain Secsnen, joined Patrick's group.[43]

Much of the Declaration concerns charges made against Patrick by his fellow Christians at a trial. What these charges were, he does not say explicitly, but he writes that he returned the gifts which wealthy women gave him, did not accept payment for baptisms, nor for ordaining priests, and indeed paid for many gifts to kings and judges, and paid for the sons of chiefs to accompany him. It is concluded, therefore, that he was accused of some sort of financial impropriety, and perhaps of having obtained his bishopric in Ireland with personal gain in mind.[46]

The condemnation might have contributed to his decision to return to Ireland. According to Patrick's most recent biographer, Roy Flechner, the Confessio was written in part as a defence against his detractors, who did not believe that he was taken to Ireland as a slave, despite Patrick's vigorous insistence that he was.[47] Patrick eventually returned to Ireland, probably settling in the west of the island, where, in later life, he became a bishop and ordained subordinate clerics.

From this same evidence, something can be seen of Patrick's mission. He writes that he "baptised thousands of people",[48] even planning to convert his slavers.[35] He ordained priests to lead the new Christian communities. He converted wealthy women, some of whom became nuns in the face of family opposition. He also dealt with the sons of kings, converting them too.[49] The Confessio is generally vague about the details of his work in Ireland, though giving some specific instances. This is partly because, as he says at points, he was writing for a local audience of Christians who knew him and his work. There are several mentions of travelling around the island and of sometimes difficult interactions with the ruling elite. He does claim of the Irish:

Never before did they know of God except to serve idols and unclean things. But now, they have become the people of the Lord, and are called children of God. The sons and daughters of the leaders of the Irish are seen to be monks and virgins of Christ![50]

Patrick's position as a foreigner in Ireland was not an easy one. His refusal to accept gifts from kings placed him outside the normal ties of kinship, fosterage and affinity. Legally he was without protection, and he says that he was on one occasion beaten, robbed of all he had, and put in chains, perhaps awaiting execution.[51] Patrick says that he was also "many years later" a captive for 60 days, without giving details.[52]

Murchiú's life of Saint Patrick contains a supposed prophecy by the druids which gives an impression of how Patrick and other Christian missionaries were seen by those hostile to them:

The second piece of evidence that comes from Patrick's life is the Letter to Coroticus or Letter to the Soldiers of Coroticus, written after a first remonstrance was received with ridicule and insult. In this, Patrick writes[55] an open letter announcing that he has excommunicated Coroticus because he had taken some of Patrick's converts into slavery while raiding in Ireland. The letter describes the followers of Coroticus as "fellow citizens of the devils" and "associates of the Scots [of Dalriada and later Argyll] and Apostate Picts".[56] Based largely on an eighth-century gloss, Coroticus is taken to be King Ceretic of Alt Clut.[57] Thompson however proposed that based on the evidence it is more likely that Coroticus was a British Roman living in Ireland.[58] It has been suggested that it was the sending of this letter which provoked the trial which Patrick mentions in the Confession.[59]

Seventh-century writings

An early document which is silent concerning Patrick is the letter of Columbanus to Pope Boniface IV of about 613. Columbanus writes that Ireland's Christianity "was first handed to us by you, the successors of the holy apostles", apparently referring to Palladius only, and ignoring Patrick.[60] Writing on the Easter controversy in 632 or 633, Cummian—it is uncertain whether this is Cumméne Fota, associated with Clonfert, or Cumméne Find—does refer to Patrick, calling him "our papa"; that is, pope or primate.[61]

Two works by late seventh-century hagiographers of Patrick have survived. These are the writings of Tírechán and the Vita sancti Patricii of Muirchú moccu Machtheni.[62] Both writers relied upon an earlier work, now lost, the Book of Ultán.[63] This Ultán, probably the same person as Ultan of Ardbraccan, was Tírechán's foster-father. His obituary is given in the Annals of Ulster under the year 657.[64] These works thus date from a century and a half after Patrick's death.

Tírechán writes, "I found four names for Patrick written in the book of Ultán, bishop of the tribe of Conchobar: holy Magonus (that is, "famous"); Succetus (that is, the god of war); Patricius (that is, father of the citizens); Cothirtiacus (because he served four houses of druids)."[65]

Muirchu records much the same information, adding that "[h]is mother was named Concessa".[66] The name Cothirtiacus, however, is simply the Latinised form of Old Irish Cothraige, which is the Q-Celtic form of Latin Patricius.[67]

The Patrick portrayed by Tírechán and Muirchu is a martial figure, who contests with druids, overthrows pagan idols, and curses kings and kingdoms.[68] On occasion, their accounts contradict Patrick's own writings: Tírechán states that Patrick accepted gifts from female converts although Patrick himself flatly denies this. However, the emphasis Tírechán and Muirchu placed on female converts, and in particular royal and noble women who became nuns, is thought to be a genuine insight into Patrick's work of conversion. Patrick also worked with the unfree and the poor, encouraging them to vows of monastic chastity. Tírechán's account suggests that many early Patrician churches were combined with nunneries founded by Patrick's noble female converts.[69]

The martial Patrick found in Tírechán and Muirchu, and in later accounts, echoes similar figures found during the conversion of the Roman Empire to Christianity. It may be doubted whether such accounts are an accurate representation of Patrick's time, although such violent events may well have occurred as Christians gained in strength and numbers.[70]

Much of the detail supplied by Tírechán and Muirchu, in particular the churches established by Patrick, and the monasteries founded by his converts, may relate to the situation in the seventh century, when the churches which claimed ties to Patrick, and in particular Armagh, were expanding their influence throughout Ireland in competition with the church of Kildare. In the same period, Wilfred, Archbishop of York, claimed to speak, as metropolitan archbishop, "for all the northern part of Britain and of Ireland" at a council held in Rome in the time of Pope Agatho, thus claiming jurisdiction over the Irish church.[71]

Other presumed early materials include the Irish annals, which contain records from the Chronicle of Ireland. These sources have conflated Palladius and Patrick.[72] Another early document is the so-called First Synod of Saint Patrick. This is a seventh-century document, once, but no longer, taken as to contain a fifth-century original text. It apparently collects the results of several early synods, and represents an era when pagans were still a major force in Ireland. The introduction attributes it to Patrick, Auxilius, and Iserninus, a claim which "cannot be taken at face value."[73]

Legends

Patrick uses shamrock in an illustrative parable

Legend credits Patrick with teaching the Irish about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity by showing people the shamrock, a three-leafed plant, using it to illustrate the Christian teaching of three persons in one God.[74] The earliest written version of the story is given by the botanist Caleb Threlkeld in his 1726 Synopsis stirpium Hibernicarum, but the earliest surviving records associating Patrick with the plant are coins depicting Patrick clutching a shamrock which were minted in the 1680s.[75][76]

In pagan Ireland, three was a significant number and the Irish had many triple deities, a fact that may have aided Patrick in his evangelisation efforts when he "held up a shamrock and discoursed on the Christian Trinity".[77][78] Patricia Monaghan says there is no evidence that the shamrock was sacred to the pagan Irish.[77] However, Jack Santino speculates that it may have represented the regenerative powers of nature, and was recast in a Christian context. Icons of St Patrick often depict the saint "with a cross in one hand and a sprig of shamrocks in the other".[79] Roger Homan writes, "We can perhaps see St Patrick drawing upon the visual concept of the triskele when he uses the shamrock to explain the Trinity".[80]

Patrick banishes snakes from Ireland

Ireland was well known to be a land without snakes, and this was noted as early as the third century by Gaius Julius Solinus, but later legend credited Patrick with banishing snakes from the island. The earliest text to mention an Irish saint banishing snakes from Ireland is in fact the Life of Saint Columba (chapter 3.23), written in the late seventh or early eighth century.[81] The earliest writings about Patrick ridding Ireland of snakes are by Jocelyn of Furness in the late twelfth century,[82] who says that Patrick chased them into the sea after they attacked him during his fast on a mountain.[83] Gerald of Wales also mentions the story in the early thirteenth century, but he is doubtful of its truthfulness.[84] The hagiographic theme of banishing snakes may draw on the Biblical account of the staff of the prophet Moses. In Exodus 7:8–7:13, Moses and Aaron use their staffs in their struggle with Pharaoh's sorcerers, the staffs of each side turning into snakes. Aaron's snake-staff prevails by consuming the other snakes.[85]

Post-glacial Ireland never had snakes.[83] "At no time has there ever been any suggestion of snakes in Ireland, so [there was] nothing for St. Patrick to banish", says naturalist Nigel Monaghan, keeper of natural history at the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin, who has searched extensively through Irish fossil collections and records.[83]

Patrick's fast on the mountain

Tírechán wrote in the 7th century that Patrick spent forty days on the mountaintop of Cruachán Aigle, as Moses did on Mount Sinai. The 9th century Bethu Phátraic says that Patrick was harassed by a flock of black demonic birds while on the peak, and he banished them into the hollow of Lugnademon ("hollow of the demons") by ringing his bell. Patrick ended his fast when God gave him the right to judge all the Irish at the Last Judgement, and agreed to spare the land of Ireland from the final desolation.[86][28] A later legend tells how Patrick was tormented on the mountain by a demonic female serpent named Corra or Caorthannach. Patrick is said to have banished the serpent into Lough Na Corra below the mountain, or into a hollow from which the lake burst forth.[87] The mountain is now known as Croagh Patrick (Cruach Phádraig) after the saint.

Patrick and Dáire

According to tradition, Patrick founded his main church at Armagh (Ard Mhacha) in the year 445. Muirchú writes that a pagan chieftain named Dáire would not let Patrick build a church on the hill of Ard Mhacha, but instead gave him lower ground to the east. One day, Dáire's horses die after grazing on the church land. He tells his men to kill Patrick, but is himself struck down with illness. Dáire's men beg Patrick to heal him, and Patrick's holy water revives both Dáire and his horses. Dáire rewards Patrick with a great bronze cauldron and gave him the hill of Ard Mhacha to build a church, which eventually became the head church of Ireland. Dáire has similarities with the Dagda, an Irish god who owns a cauldron of plenty.[88]

In a later legend, the pagan chieftain is named Crom. Patrick asks the chieftain for food, and Crom sends his bull, in the hope that it will drive off or kill Patrick. Instead, it meekly submits to Patrick, allowing itself to be slaughtered and eaten. Crom demands his bull be returned. Patrick has the bull's bones and hide put together and brings it back to life. In some versions, Crom is so impressed that he converts to Christianity, while in others he is killed by the bull. In parts of Ireland, Lughnasa (1 August) is called 'Crom's Sunday' and the legend could recall bull sacrifices during the festival.[89]

Patrick speaks with ancient Irish ancestors

The twelfth-century work Acallam na Senórach tells of Patrick being met by two ancient warriors, Caílte mac Rónáin and Oisín, during his evangelical travels. The two were once members of Fionn mac Cumhaill's warrior band the Fianna, and somehow survived to Patrick's time.[90] In the work St. Patrick seeks to convert the warriors to Christianity, while they defend their pagan past. The heroic pagan lifestyle of the warriors, of fighting and feasting and living close to nature, is contrasted with the more peaceful, but unheroic and non-sensual life offered by Christianity.[91]

Patrick and the innkeeper

A much later legend tells of Patrick visiting an inn and chiding the innkeeper for being ungenerous with her guests. Patrick tells her that a demon is hiding in her cellar and being fattened by her dishonesty. He says that the only way to get rid of the demon is by mending her ways. Sometime later, Patrick revisits the inn to find that the innkeeper is now serving her guests cups of whiskey filled to the brim. He praises her generosity and brings her to the cellar, where they find the demon withering away. It then flees in a flash of flame, and Patrick decrees that people should have a drink of whiskey on his feast day in memory of this. This is said to be the origin of "drowning the shamrock" on Saint Patrick's Day.[92]

Battle for the body of St Patrick

According to the Annals of the Four Masters, an early-modern compilation of earlier annals, his corpse soon became an object of conflict in the Battle for the Body of Saint Patrick (Cath Coirp Naomh Padraic):

The Uí Néill and the Airgíalla attempted to bring it to Armagh; the Ulaid tried to keep it for themselves.

When the Uí Néill and the Airgíalla came to a certain water, the river swelled against them so that they were not able to cross it. When the flood had subsided the Ui Neill and the Ulaid united on terms of peace, to bring the body of Patrick with them. It appeared to each of them that each had the body conveying it to their respective territories. The body of Patrick was afterwards interred at Dun Da Lethglas with great honour and veneration; and during the twelve nights that the religious seniors were watching the body with psalms and hymns, it was not night in Magh Inis or the neighbouring lands, as they thought, but as if it were the full undarkened light of day.[93]

Modern theories

"Two Patricks" theory

Irish academic T. F. O'Rahilly proposed the "Two Patricks" theory,[94] which suggests that many of the traditions later attached to Saint Patrick actually concerned the aforementioned Palladius, who, according to Prosper of Aquitaine's Chronicle, was sent by Pope Celestine I as the first bishop to Irish Christians in 431. Palladius was not the only early cleric in Ireland at this time. The Irish-born Saint Ciarán of Saigir lived in the later fourth century (352–402) and was the first bishop of Ossory. Ciaran, along with saints Auxilius, Secundinus and Iserninus, is also associated with early churches in Munster and Leinster. By this reading, Palladius was active in Ireland until the 460s.[95]

Prosper associates Palladius' appointment with the visits of Germanus of Auxerre to Britain to suppress Pelagianism and it has been suggested that Palladius and his colleagues were sent to Ireland to ensure that exiled Pelagians did not establish themselves among the Irish Christians. The appointment of Palladius and his fellow bishops was not obviously a mission to convert the Irish, but more probably intended to minister to existing Christian communities in Ireland.[96] The sites of churches associated with Palladius and his colleagues are close to royal centres of the period: Secundus is remembered by Dunshaughlin, County Meath, close to the Hill of Tara which is associated with the High King of Ireland; Killashee, County Kildare, close to Naas with links with the kings of Leinster, is probably named for Auxilius. This activity was limited to the southern half of Ireland, and there is no evidence for them in Ulster or Connacht.[97]

Although the evidence for contacts with Gaul is clear, the borrowings from Latin into Old Irish show that links with Roman Britain were many.[98] Iserninus, who appears to be of the generation of Palladius, is thought to have been a Briton, and is associated with the lands of the Uí Ceinnselaig in Leinster. The Palladian mission should not be contrasted with later "British" missions, but forms a part of them;[99] nor can the work of Palladius be uncritically equated with that of Saint Patrick, as was once traditional.[94]

Abduction reinterpreted

According to Patrick's own account, it was Irish raiders who brought him to Ireland where he was enslaved and held captive for six years.[100] However, a recent alternative interpretation by Roy Flechner of Patrick's departure to Ireland suggests that, as the son of a decurion, he would have been obliged by Roman law to serve on the town council (curia), but chose instead to abscond from the onerous obligations of this office by fleeing abroad, as many others in his position had done in what has become known as the 'flight of the curiales'.[101] Flechner also asserts the improbability of an escape from servitude and a journey of the kind that Patrick purports to have undertaken. He also interprets the biblical allusions in Patrick's account (e.g. the theme of freedom after six years of servitude in Exod. 21:2 or Jer. 34:14), as implying parts of the account may not have been intended to be understood literally.[102]

Sainthood and veneration

17 March, popularly known as Saint Patrick's Day, is believed to be his death date and is the date celebrated as his Feast Day.[103] The day became a feast day in the Catholic Church due to the influence of the Waterford-born Franciscan scholar Luke Wadding, as a member of the commission for the reform of the Breviary in the early part of the 17th century.[104]

For most of Christianity's first thousand years, canonisations were done on the diocesan or regional level. Relatively soon after the death of people considered very holy, the local Church affirmed that they could be liturgically celebrated as saints. As a result, Patrick has never been formally canonised by a pope (common before 10th century); nevertheless, various Christian churches declare that he is a saint in Heaven (see List of Saints). He is still widely venerated in Ireland and elsewhere today.[105]

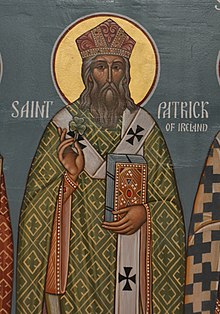

Patrick is honoured with a feast day on the liturgical calendar of the Episcopal Church (USA) and with a commemoration on the calendar of Evangelical Lutheran Worship, both on 17 March. Patrick is also venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church as a pre-Schism Western saint, especially among Orthodox Christians living in Ireland and the Anglosphere;[106] as is usual with saints, there are Orthodox icons dedicated to him.[107]

Saint Patrick remains a recurring figure in Folk Christianity and Irish folktales.[108]

Patrick is said to be buried at Down Cathedral in Downpatrick, County Down, alongside Saint Brigid and Saint Columba, although this has never been proven. Saint Patrick Visitor Centre is a modern exhibition complex located in Downpatrick and is a permanent interpretative exhibition centre featuring interactive displays on the life and story of Patrick. It provides the only permanent exhibition centre in the world devoted to Patrick.[109]

Patrick is remembered in the Church of England with a Lesser Festival on 17 March.[110]

On 9 March 2017, his name was added to the Russian Orthodox Church calendar by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church.[111][112]

Saint Patrick's Breastplate

Saint Patrick's Breastplate is a lorica, or hymn, which is attributed to Patrick during his Irish ministry in the 5th century.

Saint Patrick's crosses

There are two main types of crosses associated with Patrick, the cross pattée and the Saltire. The cross pattée is the more traditional association, while the association with the saltire dates from 1783 and the Order of St. Patrick.

The cross pattée has long been associated with Patrick, for reasons that are uncertain. One possible reason is that bishops' mitres in Ecclesiastical heraldry often appear surmounted by a cross pattée.[113][114] An example of this can be seen on the old crest of the Brothers of St. Patrick.[115] As Patrick was the founding bishop of the Irish church, the symbol may have become associated with him. Patrick is traditionally portrayed in the vestments of a bishop, and his mitre and garments are often decorated with a cross pattée.[116][117][118][119][120]

The cross pattée retains its link to Patrick to the present day. For example, it appears on the coat of arms of both the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Armagh[121] and the Church of Ireland Archdiocese of Armagh.[122] This is on account of Patrick being regarded as the first bishop of the Diocese of Armagh. It is also used by Down District Council which has its headquarters in Downpatrick, the reputed burial place of Patrick.

Saint Patrick's Saltire is a red saltire on a white field. It is used in the insignia of the Order of Saint Patrick, established in 1783, and after the Acts of Union 1800 it was combined with the Saint George's Cross of England and the Saint Andrew's Cross of Scotland to form the Union Flag of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. A saltire was intermittently used as a symbol of Ireland from the seventeenth century but without reference to Patrick.

It was formerly a common custom to wear a cross made of paper or ribbon on St Patrick's Day. Surviving examples of such badges come in many colours[123] and they were worn upright rather than as saltires.[124]

Thomas Dinely, an English traveller in Ireland in 1681, remarked that "the Irish of all stations and condicõns were crosses in their hatts, some of pins, some of green ribbon."[125] Jonathan Swift, writing to "Stella" of Saint Patrick's Day 1713, said "the Mall was so full of crosses that I thought all the world was Irish".[126] In the 1740s, the badges pinned were multicoloured interlaced fabric.[127] In the 1820s, they were only worn by children, with simple multicoloured daisy patterns.[127][128] In the 1890s, they were almost extinct, and a simple green Greek cross inscribed in a circle of paper (similar to the Ballina crest pictured).[129] The Irish Times in 1935 reported they were still sold in poorer parts of Dublin, but fewer than those of previous years "some in velvet or embroidered silk or poplin, with the gold paper cross entwined with shamrocks and ribbons".[130]

Saint Patrick's Bell

The National Museum of Ireland in Dublin possesses a bell (Clog Phádraig)[131][133] first mentioned, according to the Annals of Ulster, in the Book of Cuanu in the year 552. The bell was part of a collection of "relics of Patrick" removed from his tomb sixty years after his death by Colum Cille to be used as relics. The bell is described as "The Bell of the Testament", one of three relics of "precious minna" (extremely valuable items), of which the other two are described as Patrick's goblet and "The Angels Gospel". Colum Cille is described to have been under the direction of an "Angel" for whom he sent the goblet to Down, the bell to Armagh, and kept possession of the Angel's Gospel for himself. The name Angels Gospel is given to the book because it was supposed that Colum Cille received it from the angel's hand. A stir was caused in 1044 when two kings, in some dispute over the bell, went on spates of prisoner taking and cattle theft. The annals make one more apparent reference to the bell when chronicling a death, of 1356: "Solomon Ua Mellain, The Keeper of The Bell of the Testament, protector, rested in Christ."

The bell was encased in a "bell shrine", a distinctive Irish type of reliquary made for it, as an inscription records, by King Domnall Ua Lochlainn sometime between 1091 and 1105. The shrine is an important example of the final, Viking-influenced, style of Irish Celtic art, with intricate Urnes style decoration in gold and silver. The Gaelic inscription on the shrine also records the name of the maker "U INMAINEN" (which translates to "Noonan"), "who with his sons enriched/decorated it"; metalwork was often inscribed for remembrance.

The bell itself is simple in design, hammered into shape with a small handle fixed to the top with rivets. Originally forged from iron, it has since been coated in bronze. The shrine is inscribed with three names, including King Domnall Ua Lochlainn's. The rear of the shrine, not intended to be seen, is decorated with crosses while the handle is decorated with, among other works, Celtic designs of birds. The bell is accredited with working a miracle in 1044,[further explanation needed] and having been coated in bronze to shield it from human eyes, for which it would be too holy. It measures 12.5 × 10 cm at the base, 12.8 × 4 cm at the shoulder, 16.5 cm from base to shoulder, 3.3 cm from shoulder to top of the handle and weighs 1.7 kg.[134]

Saint Patrick and Irish identity

Patrick features in many stories in the Irish oral tradition and there are many customs connected with his feast day. The folklorist Jenny Butler discusses how these traditions have been given new layers of meaning over time while also becoming tied to Irish identity both in Ireland and abroad. The symbolic resonance of the Saint Patrick figure is complex and multifaceted, stretching from that of Christianity's arrival in Ireland to an identity that encompasses everything Irish. In some portrayals, the saint is symbolically synonymous with the Christian religion itself. There is also evidence of a combination of indigenous religious traditions with that of Christianity, which places St Patrick in the wider framework of cultural hybridity. Popular religious expression has this characteristic feature of merging elements of culture. Later in time, the saint became associated specifically with Catholic Ireland and synonymously with Irish national identity. Subsequently, Saint Patrick is a patriotic symbol along with the colour green and the shamrock. Saint Patrick's Day celebrations include many traditions that are known to be relatively recent historically but have endured through time because of their association either with religious or national identity. They have persisted in such a way that they have become stalwart traditions, viewed as the strongest "Irish traditions".[135]

Places associated with Saint Patrick

- Slemish, County Antrim and Killala Bay, County Mayo

- When captured by raiders, there are two theories as to where Patrick was enslaved. One theory is that he herded sheep in the countryside around Slemish. Another theory is that Patrick herded sheep near Killala Bay, at a place called Fochill.

- Glastonbury Abbey, Somerset, UK

- It is claimed that he was buried within the Abbey grounds next to the high altar, which has led to many believing this is why Glastonbury was popular among Irish pilgrims. It is also believed that he was 'the founder and the first Abbot of Glastonbury Abbey.' [136] This was recorded by William of Malmesbury in his document "De antiquitate Glastoniensis ecclesiae (Concerning the Antiquity of Glastonbury)" that was compiled between 1129 and 1135, where it was noted that "After converting the Irish and establishing them solidly in the Catholic faith he returned to his native land, and was led by guidance from on high to Glastonbury. There he came upon certain holy men living the life of hermits. Finding themselves all of one mind with Patrick they decided to form a community and elected him as their superior. Later, two of their members resided on the Tor to serve its Chapel."[137] Within the grounds of the Abbey lies St. Patrick's Chapel, Glastonbury which is a site of pilgrimage to this day. The well-known Irish Scholar James Carney also elaborated on this claim and wrote "it is possible that Patrick, tired and ill at the end of his arduous mission felt released from his vow not to leave Ireland, and returned to the monastery from which he had come, which might have been Glastonbury".[138] It is also another possible burial site of the saint, where it is documented he has been "interred in the Old Wattle Church".[136]

- Saul Monastery (from Irish Sabhall Phádraig, meaning 'Patrick's barn')[139]

- It is claimed that Patrick founded his first church in a barn at Saul, which was donated to him by a local chieftain called Dichu. It is also claimed that Patrick died at Saul or was brought there between his death and burial. Nearby, on the crest of Slieve Patrick, is a huge statue of Patrick with bronze panels showing scenes from his life.

- Hill of Slane, County Meath

- Muirchu moccu Machtheni, in his highly mythologised seventh-century Life of Patrick, says that Patrick lit a Paschal fire on this hilltop in 433 in defiance of High King Laoire. The story says that the fire could not be doused by anyone but Patrick, and it was here that he explained the Holy Trinity using the shamrock.

- Croagh Patrick, County Mayo (from Irish Cruach Phádraig, meaning 'Patrick's stack')[140]

- It is claimed that Patrick climbed this mountain and fasted on its summit for the forty days of Lent. Croagh Patrick draws thousands of pilgrims who make the trek to the top on the last Sunday in July.

- Lough Derg, County Donegal (from Irish Loch Dearg, meaning 'red lake')[141]

- It is claimed that Patrick killed a large serpent on this lake and that its blood turned the water red (hence the name). Each August, pilgrims spend three days fasting and praying there on Station Island.

- Armagh

- It is claimed that Patrick founded a church here and proclaimed it to be the most holy church in Ireland. Armagh is today the primary seat of both the Catholic Church in Ireland and the Church of Ireland, and both cathedrals in the town are named after Patrick.

- Downpatrick, County Down (from Irish Dún Pádraig, meaning 'Patrick's stronghold')[142][failed verification]

- It is claimed that Patrick was brought here after his death and buried in the grounds of Down Cathedral.

Other places named after Saint Patrick include:

- Patrickswell Lane, a well in Drogheda Town where St. Patrick opened a monastery and baptised the townspeople.

- Ardpatrick, County Limerick (from Irish Ard Pádraig, meaning 'high place of Patrick')[143][failed verification]

- Patrick Water (Old Patrick Water), Elderslie, Renfrewshire. from Scots' Gaelic "AlltPadraig" meaning Patrick's Burn[144][145][146][147]

- Patrickswell or Toberpatrick, County Limerick (from Irish Tobar Phádraig, meaning 'Patrick's well')[148]

- St Patrick's Well,[149] Patterdale

- Three churches in the Diocese of Carlisle[150] are dedicated to St Patrick, they are all within the historic county of Westmorland: St Patrick's Patterdale, at the head of Ullswater (the present church was built in the 19th Century but the chapel in Patricksdale is mentioned in a charter of 1348[151]); St Patrick's Bampton, near Shap; St Patrick's Preston Patrick near Kirkby Lonsdale.

- St Patrick's Chapel, Heysham, a ruined chapel near St Peter's Church, Heysham, Lancashire. The chapel dates from the 8th Century.

- St Patrick's Island, County Dublin

- Old Kilpatrick, near Dumbarton, Scotland from "Cill Phàdraig," Patrick's Church, a claimant to his birthplace

- St Patrick's Isle, off the Isle of Man

- St. Patricks, Newfoundland and Labrador, a community in the Baie Verte district of Newfoundland

- Llanbadrig (church), Ynys Badrig (island), Porth Padrig (cove), Llyn Padrig (lake), and Rhosbadrig (heath) on the island of Anglesey in Wales

- Templepatrick, County Antrim (from Irish Teampall Phádraig, meaning 'Patrick's church')[152]

- St Patrick's Hill, Liverpool, on old maps of the town near to the former location of "St Patrick's Cross"[153]

- Parroquia San Patricio y Espiritu Santo. Loiza, Puerto Rico. The site was initially mentioned in 1645 as a chapel. The actual building was completed by 1729, is one of the oldest churches in the Americas and today represents the faith of many Irish immigrants that settled in Loiza by the end of the 18th century. Today it is a museum.

In literature

- Pedro Calderón de la Barca wrote El Purgatorio de San Patricio in 1634.[154]

- Robert Southey wrote a ballad called "Saint Patrick's Purgatory", first published in 1798, based on popular legends surrounding the saint's name.[154]

- Patrick is mentioned in a 17th-century ballad about "Saint George and the Dragon"

- Stephen R. Lawhead wrote the fictional Patrick: Son of Ireland loosely based on the saint's life, including imagined accounts of training as a druid and service in the Roman army before his conversion.[155]

- The 1999 historical novel Let Me Die in Ireland by Anabaptist author and attorney David Bercot is based on the documented facts of Patrick's life rather than the legend, and suggests implications of his example for Christians today.[156]

In film

- St. Patrick: The Irish Legend is a 2000 television historical drama film about the saint's life. Patrick is portrayed by Patrick Bergin.

- The Patron Saint of Ireland is a 2020 film based on Patrick's own writings and the earliest traditions. Patrick is portrayed by Seán Ó Meallaigh, with Robert McCormack playing him when he is younger and John Rhys-Davies in later life. It is available on Netflix in UK and Ireland.

See also

- Saint Mun

- Saint Patrick, patron saint archive

- Saint Patrick's Breastplate

- Saint Patrick's Day

- St Patrick halfpenny

- St Patrick's blue

- St Patrick's Purgatory

- St Patrick's Rock

References

- ^ "Saints by Cause". Archived from the original on 10 August 2006. Retrieved 25 August 2006.

- ^ See Flechner 2019, p. 1

- ^ "Who Was St. Patrick?". History.com. 16 October 2023.

- ^ Ritschel, Chelsea; Michallon, Clémence (17 March 2022). "What is the meaning behind St Patrick's Day?". The Independent. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

The day of celebration, which marks the day of St Patrick's death, is a religious holiday meant to celebrate the arrival of Christianity in Ireland, and made official by the Catholic Church in the early 17th century. Observed by the Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, the Eastern Orthodox Church, and the Lutheran Church, the day was typically observed with services, feasts and alcohol.

- ^ Saint Patrick Retold: The Legend and History of Ireland's Patron Saint. Princeton University Press. 2019. ISBN 9780691190013. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ See Flechner 2019, pp. 34–35

- ^ "Who was Saint Patrick and why does he have a day?". National Geographic. 1 February 2019. Archived from the original on 5 March 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2023.

- ^ MacAnnaidh, S. (2013). Irish History. Parragon Books Ltd. ISBN 978-1-4723-2723-9

- ^ Both texts in original Latin, various translations and with images of all extant manuscript testimonies on the "Saint Patrick's Confessio HyperStack website". Royal Irish Academy Dictionary of Medieval Latin from Celtic Sources. Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ Macthéni, Muirchú maccu; White, Newport John Davis (1920). St. Patrick, his writings and life. New York: The Macmillan Company. pp. 31–51, 54–60. Archived from the original on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ "Saints' Lives". Internet Medieval Sources. Fordham University. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 4 July 2017.[page needed]

- ^ a b c Dumville 1993, p. 90

- ^ Eoin Mac Neill, St. Patrick, Clonmore and Reynolds, 1964, pp. 87–88

- ^ Anthony Harvey, "The Significance of Cothraige", Ériu Vol. 36, 1985, pp. 1–9

- ^ Dumville 1993, p. 16

- ^ See Flechner 2011, pp. 125–26

- ^ a b Ó Cróinín 1995, p. 26

- ^ Stancliffe 2004

- ^ a b Byrne 1973, pp. 78–79

- ^ a b Hennessy, W. M. (trans.) Annals of Ulster; otherwise, Annals of Senat, Vol. I. Alexander Thom & Co. (Dublin), 1887.

- ^ Dumville, pp. 116–; Wood 2001, p. 45 n.5

- ^ a b Paor 1993, pp. 121–22

- ^ Ó Cróinín 1995, p. 27

- ^ Byrne 1973, p. 80

- ^ Thompson, E.A. (1999). Who Was Saint Patrick?. The Boydell Press. pp. 166–75.

- ^ Roy Flechner (2019). Saint Patrick Retold: The Legend and History of Ireland's Patron Saint. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691190013. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Paor 1993, pp. 88, 96; Bury 1905, p. 17

- ^ a b Moran, Patrick Francis (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ MacNeill, Eoin (1926). "The Native Place of St. Patrick". Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Dublin: Hodges, Figgis: 118–40. Retrieved 17 March 2013. noting that the western coasts of southern Scotland and northern England held little to interest a raider seeking quick access to booty and numerous slaves, while the southern coast of Wales offered both. In addition, the region was home to Uí Liatháin and possibly also yDéisi settlers during this time, so Irish raiders would have had the contacts to tell them precisely where to go to quickly obtain booty and capture slaves. MacNeill also suggests a possible home town in Wales based on naming similarities but allows that the transcription errors in manuscripts make this little more than an educated guess.

- ^ Cadw. "Roman Marching Camp South East of Coelbren Fort (GM343)". National Historic Assets of Wales. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

- ^ Turner, J. H. (1890). "An Inquiry as to the Birthplace of St. Patrick. By J.H. Turner, M.A. p. 268. Read before the Society, 8 January 1872. Archaeologia Scotica pp. 261–84. Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, Volume 5, 1890". Archaeologia Scotica. 5: 261–284. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2019.

- ^ a b Schama, Simon (2003). A History of Britain 1: 3000 BC-AD 1603 At the Edge of the World? (Paperback 2003 ed.). London: BBC Worldwide. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-563-48714-2.

- ^ a b c d "Confession of St Patrick". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. 7 April 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ^ "Confession of St. Patrick, Part 17". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ a b Ramirez, Janina (21 July 2016). The Private Lives of the Saints: Power, Passion and Politics in Anglo-Saxon England. Ebury Publishing. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-7535-5561-3.

- ^ "Confession #19". St Patrick's Confessio. Royal Irish Academy. Archived from the original on 19 March 2016. Retrieved 25 March 2016.

- ^ Paor 1993, pp. 99–100; Charles-Edwards 2000, p. 229; Confessio; 17–19

- ^ Paor 1993, p. 100 Paor glosses Foclut as "west of Killala Bay, in County Mayo", but it appears that the location of Fochoill (Foclut or Voclut) is still a matter of debate. See Charles-Edwards 2000, p. 215; Confessio; 17

- ^ Hood 1978, p. 4

- ^ Thomas 1981, p. 51

- ^ Bury, J.B., "Sources of the Early Patrician Documents", The English Historical Review, (Mandell Creighton et al, eds.), Longman., July 1904, p. 499

- ^ Bridgwater, William; Kurtz, Seymour, eds. (1963). "Saint Patrick". The Columbia Encyclopedia (3rd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 1611–12.

- ^ a b

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Moran, Patrick Francis (1913). "St. Patrick". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Moran, Patrick Francis (1913). "St. Patrick". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Bury 1905, p. 81

- ^ Bury 1905, p. 31

- ^ Thomas 1981, pp. 337–41; Paor 1993, pp. 104–07; Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 217–19

- ^ See Flechner 2019, p. 55

- ^ "Confession of St. Patrick, Part 50". Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Archived from the original on 23 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 219–25; Thomas 1981, pp. 337–41; Paor 1993, pp. 104–07

- ^ "Confession | St. Patrick's Confessio". www.confessio.ie. Archived from the original on 28 June 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ^ Paor 1993, p. 107; Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 221–22

- ^ Confessio; 21

- ^ This is presumed to refer to Patrick's tonsure.

- ^ After Ó Cróinín 1995, p. 32; Paor 1993, p. 180 See also Ó Cróinín 1995, pp. 30–33

- ^ "Letter To Coroticus, by Saint St. Patrick". Gilder Lehrman Center at Yale University. Archived from the original on 22 March 2010. Retrieved 11 March 2010.

- ^ Todd, James (1864). "The Epistle on Coroticus". St. Patrick: Apostle of Ireland: a Memoir of His Life and Mission, with an Introductory Dissertation on Some Early Usages of the Church in Ireland, and Its Historical Position from the Establishment of the English Colony to the Present Day. Dublin: Hodges, Smith, & Co. pp. 383–85. Archived from the original on 1 May 2016. Retrieved 17 October 2015.

- ^ Paor 1993, pp. 109–13; Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 226–30

- ^ Thompson 1980

- ^ Thomas 1981, pp. 339–43

- ^ Paor 1993, pp. 141–43; Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 182–83 Bede, writing a century later, refers to Palladius only.

- ^ Paor 1993, pp. 151–1l53; Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 182–83

- ^ Both texts in original Latin and English translations and images of the Book of Armagh manuscript copy on the "Saint Patrick's Confessio HyperStack website". Archived from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2011.

- ^ Aideen O'Leary, "An Irish Apocryphal Apostle: Muirchú's Portrayal of Saint Patrick" The Harvard Theological Review 89.3 (July 1996), pp. 287–301, traces Muichù's sources and his explicit parallels of Patrick with Moses, the bringer of rechte Litre, the "letter of the Law"; the adversary, King Lóegaire, takes the role of Pharaoh.

- ^ Annals of Ulster, AU 657.1: "Obitus... Ultán moccu Conchobair."

- ^ Paor 1993, p. 154

- ^ Paor 1993, pp. 175–77

- ^ White 1920, p. 110

- ^ Their works are found in Paor, pp. 154–74 & 175–97 respectively.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 224–26

- ^ Ó Cróinín 1995, pp. 30–33. Ramsay MacMullen's Christianizing the Roman Empire (Yale University Press, 1984) examines the better-recorded mechanics of conversion in the Empire, and forms the basis of Ó Cróinín's conclusions.

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 416–17 & 429–40

- ^ The relevant annals are reprinted in Paor 1993, pp. 117–30

- ^ Paor's conclusions at p. 135, the document itself is given at pp. 135–38.

- ^ St. Patrick's Day Facts: Snakes, a Slave, and a Saint Archived 29 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine National Geographic Retrieved 10 February 2011

- ^ Flechner 2019, p. 221.

- ^ Threlkeld, Caleb Synopsis stirpium Hibernicarum alphabetice dispositarum, sive, Commentatio de plantis indigenis præsertim Dublinensibus instituta. With An appendix of observations made upon plants, by Dr. Molyneux, 1726, cited in "shamrock, n.", The Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. 1989

- ^ a b Monaghan, Patricia (2009). The Encyclopedia of Celtic Mythology and Folklore. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1438110370.

- ^ Hegarty, Neil (2012). Story of Ireland. Ebury Publishing. ISBN 978-1448140398.

- ^ Santino, Jack (1995). All Around the Year: Holidays and Celebrations in American Life. University of Illinois Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0252065163.

- ^ Homan, Roger (2006). The Art of the Sublime: Principles of Christian Art and Architecture. Ashgate Publishing. p. 37.

- ^ Roy Flechner (2019). Saint Patrick Retold: The Legend and History of Ireland's Patron Saint. Princeton University Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-691-19001-3. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Robinson, William Erigena. New Haven Hibernian Provident Society. St. Patrick and the Irish: an oration, before the Hibernian Provident Society, of New Haven, 17 March 1842. p. 8. Archived 11 June 2020 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c Owen, James (13 March 2008). "Snakeless in Ireland: Blame Ice Age, Not St. Patrick". National Geographic News. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 17 March 2011.

- ^ Saint Patrick Retold: The Legend and History of Ireland's Patron Saint. Princeton University Press. 2019. p. 211. ISBN 978-0691190013. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- ^ Hassig, Debra, The mark of the beast: the medieval bestiary in art, Life, and literature (Taylor & Francis, 1999)[page needed]

- ^ Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (1991). Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice Hall Press. p. 358.

- ^ Corlett, Christiaan. "The Prehistoric Ritual Landscape of Croagh Patrick, Co Mayo". The Journal of Irish Archaeology, Vol. 9. Wordwell, 1998. p.19

- ^ Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. pp.357–358

- ^ Franklin, Anna; Mason, Paul (2001). Lammas: Celebrating Fruits of the First Harvest. Llewellyn Publications. p. 26.

- ^ Nagy, Joseph Falaky (2006). "Acallam na Senórach". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Oxford: ABC-CLIO. p. 8. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- ^ MacKillop, James (1998). "Acallam na Senórach". Dictionary of Celtic Mythology. Oxford. ISBN 0-19-860967-1.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí. Myth, Legend & Romance: An encyclopaedia of the Irish folk tradition. Prentice Hall Press, 1991. pp.360–361

- ^ O'Donovan, John, ed. (1856). Annála Rioghachta Éireann. Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters ... with a Translation and Copious Notes. 7 vols. Translated by O'Donovan (2nd ed.). Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. s.a. 493.3 CELT editions. Full scans at Internet Archive: Vol. 1; Vol. 2; Vol. 3; Vol. 4; Vol. 5; Vol. 6; Indices.

- ^ a b O'Rahilly 1942

- ^ Byrne, pp. 78–79; Paor 1993, pp. 6–7, 88–89; Duffy 1997, pp. 16–17; Fletcher 1997, pp. 300–06; Yorke 2006, p. 112

- ^ There may well have been Christian "Irish" people in Britain at this time; Goidelic-speaking people were found on both sides of the Irish Sea, with Irish being spoken from Cornwall to Argyll. The influence of the Kingdom of Dyfed may have been of particular importance. See Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 161–72; Dark 2000, pp. 188–90; Ó Cróinín 1995, pp. 17–18; Thomas 1981, pp. 297–300

- ^ Duffy 1997, pp. 16–17; Thomas 1981, p. 305

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 184–87; Thomas 1981, pp. 297–300; Yorke 2006, pp. 112–14

- ^ Charles-Edwards 2000, pp. 233–40

- ^ Was St Patrick a slave-trading Roman official who fled to Ireland? Archived 8 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine 17 March 2012 Dr Roy Flechner Cambridge Research News. Retrieved 9 March 2016. This article was published in Tome: Studies in Medieval History and Law in Honour of Thomas Charles-Edwards, ed. F. Edmonds and P. Russell (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2011).

- ^ See Flechner 2011, pp. 130–33

- ^ See Flechner 2011, pp. 127–28

- ^ "Ὁ Ἅγιος Πατρίκιος Ἀπόστολος τῆς Ἰρλανδίας" [The Agios Patricios Apostle of Ireland]. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ [Great Synaxaristes] (in Greek). Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

Ημ. Εορτής: 17 Μαρτίου [Feast Date: March 17]

- ^ Gregory Cleary (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Ask a Franciscan: Saints Come From All Nations – March 2001 Issue of St. Anthony Messenger Magazine Online". Archived from the original on 23 May 2011. Retrieved 25 August 2006.

- ^ "St Patrick the Bishop of Armagh and Enlightener of Ireland". oca.org. Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 11 November 2007.

- ^ "Icon of St. Patrick". www.orthodoxengland.org.uk. Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 17 March 2008.

- ^ O Suilleabhain, Sean (1952). Miraculous Plenty: Irish Religious Folktales and Legends. University College Dublin. ISBN 978-0-9565628-2-1.

- ^ About Us Archived 4 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine The Saint Patrick Centre Retrieved 20 February 2011

- ^ "The Calendar". The Church of England. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ "В месяцеслов Русской Православной Церкви включены имена древних святых, подвизавшихся в западных странах / Новости / Патриархия.ru". Патриархия.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ "ЖУРНАЛЫ заседания Священного Синода от 9 марта 2017 года / Официальные документы / Патриархия.ru". Патриархия.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 27 June 2023.

- ^ "Heraldic Dictionary – Crowns, Helmets, Chaplets & Chapeaux". Rarebooks.nd.edu. 24 February 2003. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "An Archbishop's Mitre | ClipArt ETC". Etc.usf.edu. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "Patrician Brothers Crest". 2 May 2006. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006.

- ^ "Happy Saint Patrick's Day!". Catholicism.about.com. Archived from the original on 11 May 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "St. Patrick". Catholicharboroffaithandmorals.com. Archived from the original on 1 June 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "Happy Saint Patrick's Day, 2011". Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Our Stained Glass Windows – St. Patrick". Archived from the original on 12 November 2013.

- ^ "Optional Memorial of St. Patrick, bishop and confessor (Solemnity Aus, Ire, Feast New Zeal, Scot, Wales) – March 17, 2012 – Liturgical Calendar – Catholic Culture". Catholicculture.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Armagh". Armagharchdiocese.org. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 5 July 2018. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ "The Church of Ireland Diocese of Armagh | For information about the Church of Ireland Diocese of Armagh". Armagh.anglican.org. Archived from the original on 3 February 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2018.

- ^ Hayes-McCoy, p. 40

- ^ Morley, Vincent (27 September 2007). "St. Patrick's Cross". Archived from the original on 13 November 2013. Retrieved 29 June 2009.

- ^ Colgan, Nathaniel (1896). "The Shamrock in Literature: a critical chronology". Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland. 26. Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland: 349.

- ^ Swift, Jonathan (2008). "Letter 61". Journal to Stella. eBooks@Adelaide. University of Adelaide. Archived from the original on 25 May 2013. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- ^ a b Croker, Thomas Crofton (1839). The Popular Songs of Ireland. Collected and Edited, with Introductions and Notes. Henry Colburn. pp. 7–9. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland Vol. 18, plate facing p. 249 'Kilmalkedar'; fig. 4 is "St. Patrick's Cross" [p. 251] of children in S. of Irl. c. 1850s

- ^ Colgan, p. 351, fn.2

- ^ "Irishman's Diary: The Patrick's Cross". The Irish Times. 13 March 1935. p. 4 – via ProQuest.

- ^ "Clog Phádraig agus a Chumhdach [The Bell of St. Patrick and its Shrine]". Dublin: NMI. 2015. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Haweis, Hugh Reginald (1878), , in Baynes, T. S. (ed.), Encyclopædia Britannica, vol. 3 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, p. 536

- ^ The bell was formerly known as "The Bell of St Patrick's Will" (Clog an eadhachta Phatraic),[132] in reference to a medieval forgery which purported to have been the saint's last will and testament.

- ^ Treasures of early Irish art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D.: from the collections of the National Museum of Ireland, Royal Irish Academy, Trinity College, Dublin Archived 26 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), bell No. 45, shrine # 61; The Bellshrine of St. Patrick Archived 20 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine, Clan McLaughlan website

- ^ Butler, Jenny (2012), "St. Patrick, Folklore and Irish National Identity" 84–101 in Heimo, Anne; Hovi, Tuomas; Vasenkari, Maria, ed. Saint Urho – Pyhä Urho – From Fakelore To Folklore, University of Turku: Finland. ISBN 978-951-29-4897-0

- ^ a b "'St Patrick's life shows the ties between Ireland and Somerset'". Matthew Bell. 16 March 2016. Archived from the original on 1 October 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Ademi de Domerham Historia de Rebus Gestis Glastoniensibus, ed. T. Hearne, Oxford, 1727, see:- Glastonbury Library.

- ^ J. Carney, The Problem of St. Patrick, Dublin 1961, p.121.

- ^ "Placenames NI – The Northern Ireland Place-Name Project". Placenamesni.org. Archived from the original on 17 March 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "Cruach Phádraig, Bunachar Logainmneacha na hÉireann – Placenames Database of Ireland". logainm.ie. Government of Ireland. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "Loch Dearg, Bunachar Logainmneacha na hÉireann – Placenames Database of Ireland". logainm.ie. Government of Ireland. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "Dún Padraig, Bunachar Logainmneacha na hÉireann – Placenames Database of Ireland". logainm.ie. Government of Ireland. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "Ard Padraig, Bunachar Logainmneacha na hÉireann – Placenames Database of Ireland". logainm.ie. Government of Ireland. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "Old Patrick Water, linear feature". Saints in Scottish Place-names. Commemorations of Saints in Scottish Place-names. Archived from the original on 21 September 2015. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- ^ Theatrum Orbis Terrarum Sive Atlas Novus Volume V, Joan Blaeu, Amsterdam 1654

- ^ Registrum Monasterii de Passelet, Paisley Abbey Register 1208, 1211, 1226, 1396

- ^ A History of Elderslie by Derek P. Parker (1983), pp. vi, 3–4, 5

- ^ "Tobar Phádraig, Bunachar Logainmneacha na hÉireann – Placenames Database of Ireland". logainm.ie. Government of Ireland. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 29 December 2020. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "St Patrick's Well". Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "Diocese of Carlisle". Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ "PatterdalePAST: St Patrick's Church". Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ "Teampall Phádraig, Bunachar Logainmneacha na hÉireann – Placenames Database of Ireland". logainm.ie. Government of Ireland. 13 December 2010. Archived from the original on 8 March 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ "Introduction". Saint Patrick's Cross Liverpool. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 19 October 2012.

- ^ a b Philip Edwards, Pilgrimage and Literary Tradition (2005), p. 153

- ^ "Patrick: Son of Ireland | Books". StephenLawhead.com. 23 August 2007. Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 4 October 2009.

- ^ Bercot, David W. (1999). Let Me Die in Ireland: The True Story of Patrick. Tyler, TX: Scroll Pub. ISBN 978-0924722080. OCLC 43552984.

Works cited

- Bury, John Bagnell (1905). Life of St. Patrick and His Place in History. London: Macmillan.

- Byrne, Francis J. (1973). Irish Kings and High-Kings. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5882-4.

- Charles-Edwards, T.M. (2000). Early Christian Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36395-2.

- Dark, Ken (2000). Britain and the End of the Roman Empire. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2532-0.

- Paor, Liam De (1993). Saint Patrick's World: The Christian Culture of Ireland's Apostolic Age. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-144-0.

- Duffy, Seán, ed. (1997). Atlas of Irish History. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-7171-3093-1.

- Dumville, David M. (1993). Saint Patrick, AD 493–1993. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press. ISBN 978-0-85115-332-2.

- Flechner, Roy (2011). "Patrick's Reasons for Leaving Britain". In Russell, Edmonds (ed.). Tome: Studies in Medieval Celtic History and Law in Honour of Thomas Charles-Edwards. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-661-2.

- Flechner, Roy (2019). Saint Patrick Retold: The Legend and History of Ireland's Patron Saint. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691184647. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 11 March 2019.

- Fletcher, Richard (1997). The Conversion of Europe: From Paganism to Christianity 371–1386 AD. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-686302-1.

- Hood, A.B.E. (1978). St. Patrick: his Writings, and Muirchú's Life. London and Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-299-5.

- Ó Cróinín, Dáibhí (1995). Early Medieval Ireland: 400–1200. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-01565-4.

- O'Rahilly, T. F. (1942). The Two Patricks: A Lecture on the History of Christianity in Fifth-Century Ireland. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

- Stancliffe, Claire (2004). "Patrick (fl. 5th cent.)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21562. Retrieved 17 February 2007. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Thomas, Charles (1981). Christianity in Roman Britain to AD 500. London: Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-1442-4.

- Thompson, E.A. (1980). Caird, G.B.; Chadwick, Henry (eds.). "St. Patrick and Coroticus". The Journal of Theological Studies. 31: 12–27. doi:10.1093/jts/XXXI.1.12. ISSN 0022-5185.

- White, Newport J.D. (1920). St. Patrick, His Writings and Life. New York: Macmillan. Archived from the original on 11 June 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Wood, Ian (2001). The Missionary Life: Saints and the Evangelisation of Europe 400–1050. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-31213-5.

- Yorke, Barbara (2006). The Conversion of Britain: Religion, Politics and Society in Britain c. 600–800. London: Longman. ISBN 978-0-582-77292-2.

Further reading

- Brown, Peter (2003). The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200–1000 (2nd ed.). Oxford: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22138-8.

- Cahill, Thomas (1995). How the Irish Saved Civilization. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-41849-2.

- Dumville, David (1994). "The Death Date of St. Patrick". In Howlett, David (ed.). The Book of Letters of Saint Patrick the Bishop. Dublin: Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-85182-136-5.

- Healy, John (1892). . The Ancient Irish Church (1 ed.). London: Religious Tract Society. pp. 17–25.

- Hughes, Kathleen (1972). Early Christian Ireland: Introduction to the Sources. London: Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-0-340-16145-6.

- Iannello, Fausto (2008). "Note storiche sull'Epistola ad Milites Corotici di San Patrizio". Atti della Accademia Peloritana dei Pericolanti, Classe di Lettere, Filosofia e Belle Arti. 84: 275–285.

- Iannello, Fausto (2012), "Il modello paolino nell’Epistola ad milites Corotici di san Patrizio, Bollettino di Studi Latini 42/1: 43–63

- Iannello, Fausto (2013), "Notes and Considerations on the Importance of St. Patrick's Epistola ad Milites Corotici as a Source on the Origins of Celtic Christianity and Sub-Roman Britain". Imago Temporis. Medium Aevum 7 2013: 97–137

- Moran, Patrick Francis Cardinal (1913). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- McCaffrey, Carmel (2003). In Search of Ancient Ireland. Chicago: Ivan R Dee. ISBN 978-1-56663-525-7.

- MacQuarrie, Alan (1997). The Saints of Scotland: Essays in Scottish Church History AD 450–1093. Edinburgh: John Donald. ISBN 978-0-85976-446-9.

- O'Loughlin, Thomas (1999). Saint Patrick: The Man and his Works. London: S.P.C.K.

- O'Loughlin, Thomas (2000). Celtic Theology. London: Continuum.

- O'Loughlin, Thomas (2005). Discovering Saint Patrick. New York: Orbis.

- O'Loughlin, Thomas (2005). "The Capitula of Muirchu's Vita Patricii: do they point to an underlying structure in the text?". Analecta Bollandiana. 123: 79–89. doi:10.1484/J.ABOL.4.00190.

- O'Loughlin, Thomas (2007). Nagy, J. F. (ed.). The Myth of Insularity and Nationality in Ireland. Dublin: Four Courts Press. pp. 132–140.

External links

- Works by Saint Patrick at Project Gutenberg

- The Most Ancient Lives of Saint Patrick, edited by James O'Leary, 1880, from Project Gutenberg.

- Works by or about Saint Patrick at the Internet Archive

- Works by Saint Patrick at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- St. Patrick's Confession and Epistola online from the Royal Irish Academy

- BBC: Religion & Ethics, Christianity: Saint Patrick (Incl. audio)

- Opera Omnia by Migne Patristica Latina with analytical indexes

- CELT Archived 25 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine: Corpus of Electronic Texts at University College Cork includes Patrick's Confessio and Epistola, as well as various lives of Saint Patrick.

- Saint Patrick's Confessio Hypertext Stack as published by the Royal Irish Academy Dictionary of Medieval Latin from Celtic Sources (DMLCS) freely providing digital scholarly editions of Saint Patrick's writings as well as translations and digital facsimiles of all extant manuscript copies.

- History Hub.ie: Saint Patrick – Historical Man and Popular Myth by Elva Johnston (University College Dublin)

- Saint Patrick Timeline | Church History Timelines

- Saint Patrick

- 4th-century births

- 5th-century births

- 5th-century Irish bishops

- 5th-century Christian saints

- 5th-century deaths

- 5th-century writers in Latin

- Christian missionaries in Ireland

- Irish slaves

- Medieval Irish saints

- Medieval Irish writers

- Ancient slaves

- Northern Brythonic saints

- Romano-British saints

- Sub-Roman writers

- Miracle workers

- Writers of captivity narratives

- Anglican saints

- Lutheran saints

- Irish writers in Latin