Origin of the Albanians: Difference between revisions

Woohookitty (talk | contribs) m WikiCleaner 0.99 - Repairing link to disambiguation page - (You can help) |

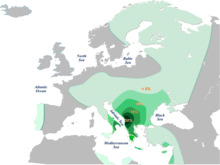

→Genetic studies: Adding map of J2 |

||

| Line 239: | Line 239: | ||

| issue = 5 }}</ref><ref name=Pericic>{{Cite news | author=Peričic et al. | year=2005 | title=High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations | periodical=Mol. Biol. Evol. | volume=22 | issue=10 | pages=1964–75 | pmid=15944443 | url=http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/22/10/1964 | doi=10.1093/molbev/msi185 | last2=Lauc | first2=LB | last3=Klarić | first3=IM | last4=Rootsi | first4=S | last5=Janićijevic | first5=B | last6=Rudan | first6=I | last7=Terzić | first7=R | last8=Colak | first8=I | last9=Kvesić | first9=A}}</ref> |

| issue = 5 }}</ref><ref name=Pericic>{{Cite news | author=Peričic et al. | year=2005 | title=High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations | periodical=Mol. Biol. Evol. | volume=22 | issue=10 | pages=1964–75 | pmid=15944443 | url=http://mbe.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/22/10/1964 | doi=10.1093/molbev/msi185 | last2=Lauc | first2=LB | last3=Klarić | first3=IM | last4=Rootsi | first4=S | last5=Janićijevic | first5=B | last6=Rudan | first6=I | last7=Terzić | first7=R | last8=Colak | first8=I | last9=Kvesić | first9=A}}</ref> |

||

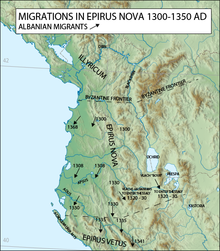

[[Image:Cardial map.png|thumb|255px|left|Distribution of Cardial Pottery corresponds with that of Hg J2]] |

|||

* [[Haplogroup J (Y-DNA)|Y haplogroup J]] in the modern Balkans is mainly represented by the sub-clade J2b (also known as J-M12 or J-M102 for example). Like E-V13, this clade is spread throughout Europe with a seeming centre and origin near Albania.<ref name=cruciani2007/><ref name=battaglia/><ref name=semino2004>{{Cite news | author=Semino et al. | year=2000 | title=The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic ''Homo sapiens sapiens'' in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective | periodical=Science | volume=290 | pages=1155–59 | pmid=11073453 | url=http://hpgl.stanford.edu/publications/Science_2000_v290_p1155.pdf | doi=10.1126/science.290.5494.1155}}</ref><ref name=Pericic/> |

* [[Haplogroup J (Y-DNA)|Y haplogroup J]] in the modern Balkans is mainly represented by the sub-clade J2b (also known as J-M12 or J-M102 for example). Like E-V13, this clade is spread throughout Europe with a seeming centre and origin near Albania.<ref name=cruciani2007/><ref name=battaglia/><ref name=semino2004>{{Cite news | author=Semino et al. | year=2000 | title=The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic ''Homo sapiens sapiens'' in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective | periodical=Science | volume=290 | pages=1155–59 | pmid=11073453 | url=http://hpgl.stanford.edu/publications/Science_2000_v290_p1155.pdf | doi=10.1126/science.290.5494.1155}}</ref><ref name=Pericic/> |

||

Revision as of 13:51, 11 October 2010

| History of Albania |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

|

|

The origin of the Albanians has been for some time a matter of dispute among historians. Most historians conclude that the Albanians are descendants of populations of the prehistoric Balkans, such as the Illyrians, Dacians or Thracians. Little is known about these peoples, and they blended into one another in Thraco-Illyrian and Daco-Thracian contact zones even in antiquity.

The Albanians first appear in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the late 11th century. At this point, they are already fully Christianized. Very little evidence of pre-Christian Albanian culture survives and Albanian mythology and folklore as it presents itself is notoriously syncretized from various sources, especially showing Greek influence.[1]

Regarding the classification of the Albanian language, it forms a separate branch of Indo-European, emerging in the Middle Ages (first attestation 15th century), apparently based on the wider Paleo-Balkans group of antiquity.

Studies in genetic anthropology show that the Albanians share the same ancestry as most other European peoples.[2]

Place of origin

The place where the Albanian language was formed is uncertain, but analysis has suggested that it was in a mountainous region, rather than in a plain or seacoast[3]: while the words for plants and animals characteristic of mountainous regions are entirely original, the names for fish and for agricultural activities (such as ploughing) are borrowed from other languages.[4]

It can also be presumed that the Albanians did not live in Dalmatia, because the Latin influence over Albanian is of Eastern Romance origin, rather than of Dalmatian origin. This influence includes Latin words exhibiting idiomatic expressions and changes in meaning found only in Eastern Romance and not in other Romance languages. Adding to this the many words found in Romanian with Albanian cognates (see Eastern Romance substratum), it may be assumed that Romanians and Albanians lived in close proximity at one time.[4] Generally, the areas where this might have happened are considered to be regions varying from Transylvania, what is now Eastern Serbia (the region around Naissus and the Morava valley), Kosovo and Northern Albania.[5]

However, most agricultural terms in Romanian are of Latin origin, but not the terms related to city activities — indicating that Romanians were an agricultural people in the low plains, as opposed to Albanians, who were originally shepherds in the highlands.

Some scholars even explain the gap between the Bulgarian and Serbian languages by postulating an Albanian-Romanian buffer-zone east of the Morava river.[citation needed] Although an intermediary Serbian dialect exists, it was formed only later, after the Serbian expansion to the east.[citation needed]

Another argument that sustains a northern origin of the Albanians is the relatively small number of words of Greek origin,[6] even though Southern Illyria neighbored the Classical Greek civilization and there was a number of Greek colonies along the Illyrian coastline.Several Illyrian tribes had even become bilingual early on[7] such as the Taulantii and the Bylliones. Southern Illyria, called Epirus Nova by the Romans, is considered to have become Greek due to colonization[8] by Greeks[9] and Hellenization[8] of the natives, to the point where the Romans called it Illyria Graeca.[10] This further supports a Northern origin for the Albanians.

Written sources

Arbanon

While the exonym Albania for the general region inhabited by the Albanians can be traced back to the Roman era, and possibly an Illyrian tribe, its endonym being shqiptar.

- In the 2nd century BC, the History of the World written by Polybius, mentions a location named Arbon[11] or Arbo[12] (Template:Lang-el)[13] that was perhaps an island[14] in Liburnia or another location within Illyria. Stephanus of Byzantium centuries later, cites Polybius, saying it was a city in Illyria and gives an ethnic name(see below) for its inhabitants.

- In the 2nd century AD, Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria, drafted a map that shows the city of Albanopolis (located Northeast of Durrës). Ptolemy also mentions the Illyrian tribe named Albanoi[15], who lived around this city.

- In the 6th century AD, Stephanus of Byzantium in his important geographical dictionary entitled Ethnica (Εθνικά)[16] mentions a city in Illyria called Arbon (Template:Lang-el), with its inhabitants called Arbonios (Template:Lang-el) and Arbonites (Template:Lang-el). He cites Polybius[16] (he does so many[17][18] times in ethnica) and does not claim that such city or people existed during his time.

In the 12th to 13th centuries, Byzantine writers use the words Arbanon (Template:Lang-el) for a principality in the region of Kruja.

Byzantine references to "Albanians"

- In History written in 1079-1080, Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates referred to the Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the duke of Dyrrachium. It is disputed, however, whether that refers to Albanians in an ethnic sense.[19]

- The earliest Serbian source mentioning "Albania" (Ar'banas') is a charter by Stefan Nemanja, dated 1198, which lists the region of Pilot (Pulatum) among the parts Nemanja conquered from Albania (ѡд Арьбанась Пилоть, "de Albania Pulatum").[20]

- 1285 in Dubrovnik (Ragusa) a document states: "Audivi unam vocem clamantem in monte in lingua albanesca" (I heard a voice crying in the mountains in the Albanian language).[21]

- Arbanasi people are recorded as being 'half-believers' (non-Orthodox Christians) and speaking their own language in the Fragment of Origins of Nations between 1000-1018 by an anonymous author in a Bulgarian text of the 11th century.[22]

- Arbanitai of Arbanon are recorded in an account by Anna Comnena of the troubles in that region during the reign of her father Alexius I Comnenus (1081–1118) by the Normans.[23]

Albanian endonym "Shqiptar"

There are various theories of the origin of the word shqiptar:

- A theory by Ludwig Thallóczy, Milan Šufflay and Konstantin Jireček, which is today considered obsolete, derived the name from a Drivastine family name recorded in varying forms during the 14th century: Schepuder (1368), Scapuder (1370), Schipudar, Schibudar (1372), Schipudar (1383, 1392), Schapudar (1402), etc.

- Gustav Meyer derived Shqiptar from the Albanian verbs shqipoj (to speak clearly) and shqiptoj (to speak out, pronounce), which are in turn derived from the Latin verb excipere, denoting brethren who speak the Albanian language, similar to the ethno-linguistic dichotomies Sloven-Nemac and Deutsch-Wälsch.[24] This theory is also sustained by Robert Elsie.[25]

- Petar Skok suggested that the name originated from Scupi (Template:Lang-sq), the capital of the Roman province of Dardania.[26]

- The most accredited theory is that of Maximilian Lambertz who derived the word from the Albanian noun shqype or shqiponjë (eagle), which, according to Albanian folk etymology, denoted a bird totem dating from the times of Skanderbeg, as displayed on the Albanian flag.[26]

First attestation of the Albanian language

The first document in the Albanian language (as spoken in the region around Mat) was recorded in 1462 by Paulus Angelus (whose name was later Albanized to Pal Engjëll), the archbishop of the Catholic Archdiocese of Durazzo (modern Durrës).[27]

Paleo-Balkanic predecessors

While Albanian (shqip) ethnogenesis clearly postdates the Roman era, an ultimate composition from prehistoric populations is widely held plausible, already because of the isolated position of the Albanian language within Indo-European.

The three chief candidates considered by historians are Illyrian, Dacian, or Thracian, though there were other non-Greek groups in the ancient Balkans, including Paionians (who lived north of Macedon) and Agrianians. The Illyrian language and the Thracian language are often considered to have been on different Indo-European branches. Not much is left of the old Illyrian, Dacian or Thracian tongues, making it difficult to match Albanian with them.

There is debate whether the Illyrian language was a centum or a satem language. It is also uncertain whether Illyrians spoke a homogeneous language or rather a collection of different but related languages that were wrongly considered the same language by ancient writers. Some of those tribes, along with their language, are no longer considered Illyrian.[28][29] The same is sometimes said of the Thracian language. For example, based on the toponyms and other lexical items, Thracian and Dacian were probably different but related languages.

In the early half of the 20th century, many scholars thought that Thracian and Illyrian were one language branch, but due to the lack of evidence, most linguists are skeptical and now reject this idea, and usually place them on different branches.

The origins debate is often politically charged, and to be conclusive more evidence is needed. Such evidence unfortunately may not be easily forthcoming because of a lack of sources. Scholars are beginning to move away from a single-origin scenario of Albanian ethnogenesis. The area of what is now Macedonia and Albania was a melting pot of Thracian, Illyrian and Greek cultures in ancient times.[citation needed]

Illyrian origin

The theory that Albanians were related to the Illyrians was proposed for the first time by the Swedish[30] historian Johann Erich Thunmann in 1774.[31] The scholars who advocate an Illyrian origin are numerous.[32][33][34][35] There are two variants of the theory: one is that the Albanians are the descendants of indigenous Illyrian tribes dwelling in what is now Albania.[36] The other is that the Albanians are the descendants of Illyrian tribes located north of the Jireček Line and probably north or northeast of Albania.[37]

The arguments for the Illyrian-Albanian connection have been as follows:[35][38]

- The national name Albania is derived from Albanoi,[39][40][41] an Illyrian tribe mentioned by Ptolemy about 150 A.D., though nothing absolutely proves a connection to the later Albanians, who appear in the historical record in Byzantine documents of the 11th century.[42]

- From what we know from the old Balkan populations territories (Greeks, Illyrians, Thracians, Dacians), Albanian language is spoken in the same region where Illyrian was spoken in ancient times.[43]

- There is no evidence of any major migration into Albanian territory since the records of Illyrian occupation.[44]

- Many of what remain as attested words to Illyrian have an Albanian explanation and also a number of Illyrian lexical items (toponyms, hydronyms, oronyms, anthroponyms, etc.) have been linked to Albanian.[45]

- Borrowed words (e.g. Gk (NW) "device, instrument" mākhaná > *mokër "millstone" Gk (NW) drápanon > *drapër "sickle" etc.) from Greek language date back before the Christian era[44] and are mostly of Doric dialect of Greek language,[46] which means that the ancestors of the Albanians were in Northwestern part of Ancient Greek civilization and probably borrowed them from Greek cities (Dyrrachium, Apollonia, etc.) in the Illyrian territory, colonies which belonged to the Doric division of Greek, or from the contacts in Epirus area.

- Borrowed words from Latin (e.g. Latin aurum > ar "gold", gaudium > gaz "gas" etc.[47]) date back before the Christian era,[48][38] while Illyrians in the today's Albanian territory were the first from the old Balkan populations to be conquered by Romans in 229 - 167 B.C., Thracians were conquered in 45 A.D. and Dacians in 106 A.D.

- The ancient Illyrian place-names of the region have achieved their current form following Albanian phonetic rules e.g. Durrachion > Durrës (with the Albanian initial accent) Aulona > Vlonë~Vlorë (with rhotacism) Scodra > Shkodra etc.[38][44][46][49]

- The characteristics of the Albanian dialects Tosk and Geg[50] in the treatment of the native and loanwords from other languages, have led to the conclusion that the dialectal split preceded the Slavic migration to the Balkans[51][52] which means that in that period (5th to 6th century AD) Albanians were occupying pretty much the same area around Shkumbin river[53] which straddled the Jirecek line.[38][54]

To propagate the connection, the Albanian communist regime adopted a policy of naming people with "Illyrian" names.[55] The reverses of three Albanian coins depict Illyrian motives: an Illyrian helmet in the 50 lekë coin issued in 2003, king Gentius in the 50 lekë coin issued in 1996 and 2000, and queen Teuta in the 100 lekë coin issued in 2000.[56] Gentius is also depicted on the obverse of the 2000 lekë banknote, issued in 2008.[57]

Arguments against Illyrian origin

The theory of an Illyrian origin of the Albanians is challenged on linguistic grounds.[4]

- According to linguist V. Georgiev, the theory of an Illyrian origin for the Albanians is weakened by a lack of any Albanian names before the 12th century and the relative absence of Greek influence that would surely be present if the Albanians inhabited their homeland continuously since ancient times.[58] The number of Greek words borrowed in Albania is small; if the Albanians originated near modern-day Albania, there should be more.[59]

- According to Georgiev, although some Albanian toponyms descend from Illyrian, Illyrian toponyms from antiquity have not changed according to the usual phonetic laws applying to the evolution of Albanian. Furthermore, placenames can be a special case and the Albanian language more generally has not been proven to be of Illyrian stock.[42]

- Many linguists have tried to link Albanian with Illyrian, but without clear results.[42][60] Albanian belongs to the satem group within Indo-European language tree, while there is a debate weather Illyrian was centum or satem. On the other hand, Dacian[60] and Thracian[61] seem to belong to satem.

- There is a lack of clear archaeological evidence for a continuous settlement of an Albanian-speaking population since Illyrian times. For example, while Albanians scholars maintain that the Komani-Kruja burial sites support the Illyrian-Albanian continuity theory, most scholars reject this and consider that the remains indicate a population of Romanized Illyrians who spoke a Romance language.[62][63][64] Recently, some Albanian archeologists have also been moving away from describing the Komani-Kruja culture as a proto-Albanian culture.[65]

- The Illyrians as a people went extinct, so did their languages by the 6th century.[66] Today, almost nothing of it survives except for names.[67] Ancient Illyrians were subject to varying degrees of Celticization,[68][69] Hellenization,[70] Romanization[71][72] and later Slavicisation.

Thracian or Dacian origin

Aside from an Illyrian origin, a Dacian or Thracian origin is also hypothesized. There are a number of factors taken as evidence for a Dacian or Thracian origin of Albanians.

The German historian Gottfried Schramm (1994) suggests an origin of the Albanians in the Bessoi, a Thracian tribe that was Christianized as early as during the 4th century. Schramm argues that such an early Christianization would explain the otherwise surprising virtual absence of any traces of a pre-Christian pagan religion among the Albanians as they appear in history during the Late Middle Ages.[73] According to this theory, the Bessoi were deported en masse by the Byzantines at the beginning of the 9th century to central Albania for the purpose of fighting against the Bulgarians. In their new homeland, the ancestors of the Albanians took the geographic name Arbanon as their ethnic name and proceeded to assimilate local populations of Slavs, Greeks, and Romans.[74]

Albanian shares several hundred [75] common words with Eastern Romance, these Eastern Romance words being part of the pre-Roman substrate (see: Eastern Romance substratum) and not loans;[citation needed] Albanian and Eastern Romance also share grammatical features (see Balkan language union) and phonological features, such as the common phonemes or the rhotacism of "n".[76]

According to linguist Vladimir Georgiev, Latin loanwords into Albanian show East Balkan Latin (proto-Romanian) phonetics, rather than West Balkan (Dalmatian) phonetics.[4] Combined with the fact that the Romanian language contains several hundred words similar only to Albanian, Georgiev proposes the Albanian language formed between the 4th and 6th century in or near modern-day Romania, which was Dacian territory.[59] Georgiev suggests that Romanian is a fully Romanised Dacian language, whereas Albanian is only partly so.[77] Georgiev's theory was criticzed by Noel Malcolm [78] because of a structural difference between the Albanian language and the survived text of a Thracian tribe.

Linguist Eric Hamp disagrees with Georgiev's theory, positing that Albanian is more closely relate to Baltic and Slavic rather than Thracian.[79] Romanian scholars tend to favour the Thracian hypothesis.[80]

Cities whose names follow Albanian phonetic laws - such as Shtip (Štip), Shkupi (Skopje) and Niš - lie in the areas once inhabited by Thracians, Dardani, and Paionians; however, Illyrians also inhabited or may have inhabited these regions, including Naissus.

There are some close correspondences between Thracian and Albanian words.[81] However, as with Illyrian, most Dacian and Thracian words and names have not been closely linked with Albanian (v. Hemp). Also, many Dacian and Thracian placenames were made out of joined names (such as Dacian Sucidava or Thracian Bessapara; see List of Dacian cities and List of ancient Thracian cities), while the modern Albanian language does not allow this.[81]

There are no records that indicate a major migration of Dacians into present day Albania, but two Dacian cities existed: Thermidava[82][83][84] close to Scodra and Quemedava[84] in Dardania. Also, Thracians existed in Dardapara. Phrygian tribes such as the Bryges were present in Albania near Durrës since before the Roman conquest (v. Hemp).[81] An argument against a Thracian origin (which does not apply to Dacian) is that most Thracian territory was on the Greek half of the Jirecek Line, aside from varied Thracian populations stretching from Thrace into Albania, passing through Paionia and Dardania and up into Moesia; it is considered that most Thracians were Hellenized in Thrace (v. Hoddinott) and Macedonia.

Apart from the linguistic theory that Albanian is more akin to eastern Romance (i.e. Dacian substrate) than western Roman (with Illyrian substrate- such as Dalmatian), Georgiev also notes that marine words in Albanian are borrowed from other languages, suggesting that Albanians were not originally a coastal people (as the Illyrians were).[77] The scarcity of Greek loan words also supports a Dacian theory - if Albanians originated in the region of Illyria there would surely be a heavy Greek influence.[77]

The Dacian theory could also be consistent with the known patterns of barbarian incursions. Although there is no documentation of an Albanian migration (in fact there is no documentation of Albanians per se until the 11th century), the Morava valley region adjacent to Dacia was most heavily affected by migrations of Goths and Slavs, and was moreover a natural invasion route.[77] Thus it would have been a region whose indigenous population would naturally have fled,[77] for example to the relative safety of mountainous northern Albania.

Genetic studies

Various genetic studies have been done on the European population, some of them including current Albanian population, Albanian-speaking populations outside Albania, and the Balkan region as a whole.

One of the first studies was that of Belledi et al. (2000)[85] which suggested that the Albanians share the same ancestry as most other European peoples. A recent study suggests a low admixture between Albanians and other populations[86]

Looking at more recent studies specifically about Y chromosomal lineages, several of the most common lineages in the Balkans vary considerably between the Albanian region and other neighbouring regions. The two haplogroups most strongly associated with the Albanian area are often considered to have arrived in Europe from the Near East with the Neolithic revolution or late Mesolithic, early in the Holocene epoch. From here in the Balkans, it is thought, they spread to the rest of Europe.

- Y haplogroup E1b1b (E-M35) in the modern Balkan population is dominated by its sub-clade E1b1b1a (E-M78) and specifically by the most common European sub-clade of E-M78, E-V13.[87] This haplogroup shows highest frequencies in and around Albanian speaking regions, however, its diversity there is correspondingly lower. This implies that V-13 did not originate in the Albanian regions, but rather accrued high frequency due to phenomena such as drift.[citation needed] Most E-V13 in Europe and elsewhere descend from a common ancestor who lived in the Balkans in the late Mesolithic or Neolithic. The current distribution of this lineage might be the result of several demographic expansions from the Balkans, such as that associated with the Neolithic revolution, the Balkan Bronze Age, and more recently, during the Roman era during the so-called "rise of Illyrican soldiery".[87][88][89][90][91][92]

- Y haplogroup J in the modern Balkans is mainly represented by the sub-clade J2b (also known as J-M12 or J-M102 for example). Like E-V13, this clade is spread throughout Europe with a seeming centre and origin near Albania.[87][88][90][92]

Common in the Balkans but not specifically associated with Albania and the Albanian language are I-M423 and R1a-M17:

- Y haplogroup I is only found in Europe, and may have been there since before the LGM. Several of its sub-clades are found in significant amounts in the Balkans. The specific I sub-clade which has attracted most discussion in Balkan studies currently referred to as I2a2, defined by SNP M423[93][94] This clade has higher frequencies to the north of the Albanophone area, in Dalmatia and Bosnia.[92]

- Haplogroup R1a is common in Central and Eastern Europe (and is also common in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent). In the Balkans, it is strongly associated with Slavic areas.[92]

The other most common Y haplogroup in the Balkans has strong associations with many parts of Europe:

- Haplogroup R1b is common all over Europe but especially common on the western Atlantic coast of Europe, and is also found in the Middle East and some parts of Africa. In Europe including the Balkans, it tends to be less common in Slavic speaking areas, where R1a is often the most common haplogroup. It shows similar frequencies among Albanians and Greeks at around 20% of the male population, but is much less common in Serbia and Bosnia.[92]

Another study of old Balkan populations and their genetic affinities with current European populations was done in 2004, based on mitochondrial DNA on the skeletal remains of some old Thracian populations from SE of Romania, dating from the Bronze and Iron Age.[95] This study was during excavations of some human fossil bones of 20 individuals dating about 3200–4100 years, from the Bronze Age, belonging to some cultures such as Tei, Monteoru and Noua were found in graves from some necropoles SE of Romania, namely in Zimnicea, Smeeni, Candesti, Cioinagi-Balintesti, Gradistea-Coslogeni and Sultana-Malu Rosu; and the human fossil bones and teeth of 27 individuals from the early Iron Age, dating from the 10th to 7th century B.C. from the Hallstatt Era (the Babadag Culture), were found extremely SE of Romania near the Black Sea coast, in some settlements from Dobrogea, namely: Jurilovca, Satu Nou, Babadag, Niculitel and Enisala-Palanca.[95] After comparing this material with the present-day European population, the authors concluded:

Computing the frequency of common point mutations of the present-day European population with the Thracian population has resulted that the Italian (7.9 %), the Albanian (6.3 %) and the Greek (5.8 %) have shown a bias of closer genetic kinship with the Thracian individuals than the Romanian and Bulgarian individuals (only 4.2%).[95]

Obsolete theories

Caucasian theory

One of the earliest theories on the origins of the Albanians identified the proto-Albanians with an area of the Caucasus referred to by classical geographers as "Albania", which roughly corresponds with modern-day Azerbaijan. This theory supposed that the ancestors of the Albanians migrated westward to the Balkans in the late classical or early Medieval period. The Caucasian theory was first proposed by Renaissance humanists who were familiar with the works of classical geographers, and later developed by Francois de Pouqeville. It still retains currency in Balkan polemics.

Pelasgian theory

Another obsolete theory on the origin of the Albanians is that they descend from the Pelasgians, a generic term used by classical authors to denote the autochthonous inhabitants of Greece. This theory was expounded by the Austrian linguist Johann Georg von Hahn in his work Albanesiche Studien in 1854. According to Hahn, the Pelasgians were the original proto-Albanians and the language spoken by the Pelasgians, Illyrians, Epirotes and ancient Macedonians were closely related. This theory quickly attracted support in Albanian circles, as it established a claim of priority over other Balkan nations, particularly the Greeks. In addition to establishing "historic right" to territory this theory also established that ancient Greek civilization and its achievements had an "Albanian" origin.[96] Although it is nowadays completely rejected by academics, it retains staunch support among Albanian nationalist circles for the above reasons.[97]

See also

- Albanian nationalism

- Illyrians

- Prehistoric Balkans

- Paleo-Balkan languages

- Historiography and nationalism

- Illyrian language

- Origin of the Romanians

- Dacian language

- Thracian language

- Ethnogenesis

- Illyrian movement

References

- ^ Mircea Eliade, Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of religion, Macmillan, 1987, ISBN 9780029097007, p. 179.

- ^ Michele Belledi, Estella S. Poloni, Rosa Casalotti, Franco Conterio, Ilia Mikerezi, James Tagliavini and Laurent Excoffier. "Maternal and paternal lineages in Albania and the genetic structure of Indo-European populations". European Journal of Human Genetics, July 2000, Volume 8, Number 7, pp. 480-486. "Mitochondrial DNA HV1 sequences and Y chromosome haplotypes (DYS19 STR and YAP) were characterized in an Albanian sample and compared with those of several other Indo-European populations from the European continent. No significant difference was observed between Albanians and most other Europeans, despite the fact that Albanians are clearly different from all other Indo-Europeans linguistically. We observe a general lack of genetic structure among Indo-European populations for both maternal and paternal polymorphisms, as well as low levels of correlation between linguistics and genetics, even though slightly more significant for the Y chromosome than for mtDNA. Altogether, our results show that the linguistic structure of continental Indo-European populations is not reflected in the variability of the mitochondrial and Y chromosome markers. This discrepancy could be due to very recent differentiation of Indo-European populations in Europe and/or substantial amounts of gene flow among these populations."

- ^ http://members.tripod.com/~Groznijat/balkan/ehamp.html Eric Hamp, "The position of Albanian, Ancient IE dialects, Proceedings of the Conference on IE linguistics held at the University of California, Los Angeles, April 25–27, 1963, ed. By Henrik Birnbaum and Jaan Puhvel. "It is clear that in the Middle Ages the Albanians extended farther north (Jokl, Albaner §2); that there are persuasive arguments which have been advanced against their having extended as far as the Adriatic coast — the fact that Scodra 'Scutari' (Shkodër) shows un-Albanian development (see §6 below), that there is no demonstrated old maritime vocabulary (see above), and that there are few ancient Greek loans (Jokl, Albaner §5; but see §5 below)

- ^ a b c d Fine, JA. The Early medieval Balkans. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1991. p.10. [1]

- ^ W. Cimochowski (BUShT 1958:3.37-48)

- ^ Eric Hamp. Birnbaum, Henrik; Puhvel, Jaan (eds.). The position of Albanian, Ancient IE dialects, Proceedings of the Conference on IE linguistics held at the University of California, Los Angeles, April 25–27, 1963.

- ^

Lewis, D. M.; Boardman, John; Hornblower, Simon; Ostwald, M., eds. (1994). The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume 6: The Fourth Century BC. p. 423. ISBN 0521233488.

Through contact with their Greek neighbors some Illyrian tribes became bilingual (Strabo Vii.7.8.Diglottoi) in particular the Bylliones and the Taulantian tribes close to Epidamnus.

- ^ a b

"Τόμοι". American Journal of Philology. Project Muse: 263. 1977.

... the partly Hellenic and partly Hellenized Epirus Nova

{{cite journal}}: More than one of|pages=and|page=specified (help) - ^

Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière Hammond (1976). Migrations and invasions in Greece and adjacent areas. p. 54. ISBN 0815550472.

The line of division between Illyricum and the Greek area Epirus nova

- ^ The Loeb Editor's Notes,28 Nova Epirus or Illyris Graeca

- ^ The general history of Polybius, Tome 1,"and escaped to Arbon"

- ^ Polybius, Histories,2.11,"Of the Illyrian troops engaged in blockading Issa, those that belonged to Pharos were left unharmed, as a favour to Demetrius; while all the rest scattered and fled to Arbo"

- ^ Polybius, Histories,2.11,"είς τόν Άρβωνα σκεδασθέντες"

- ^ Strabo, Geography H.C. Hamilton, Esq., W. Falconer, M.A., Ed,"The Libyrnides are the islands of Arbo, Pago, Isola Longa, Coronata, &c., which border the coasts of ancient Liburnia, now Murlaka."

- ^ (Ptolemy. Geogr. Ill 12,20)

- ^ a b Ethnica, Epitome, page 111,line 14, : Αρβών πόλις Ιλλυριας.Πολύβιος δευτέρα, το εθνικόν Αρβώνιος και Αρβωνίτης, ως Αντρώνιος και Ασκαλωνίτης.

- ^ Encyclopedia of ancient Greece by Nigel Guy Wilson,page 597,Polybius' own attitude to Rome has been variously interpreted, pro-Roman, ...frequently cited in reference works such as Stephanus' Ethnica and the Suda. ...

- ^ Hispaniae: Spain and the Development of Roman Imperialism, 218-82 BC by J. S. Richardson,In four places, the lexicographer Stephanus of Byzantium refers to towns and ... Artemidorus as source, and in three of the four examples cites Polybius.

- ^ Pritsak, Omeljan (1991). "Albanians". Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Vol. 1. New York/Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Thalloczy/Jirecek/Sufflay, Acta et diplomata res Albaniae mediae aetatis, Vindobonae, MCMXIII, I, 113 (1198).

- ^ Konstantin Jireček: Die Romanen in den Städten Dalmatiens während des Mittelalters, I, 42-44.

- ^ R. Elsie: Early Albania, a Reader of Historical Texts, 11th - 17th Centuries, Wiesbaden 2003, p. 3

- ^ Comnena, Anna. The Alexiad, Book IV.

- ^ Mirdita, Zef (1969). "Iliri i etnogeneza Albanaca". Iz istorije Albanaca. Zbornik predavanja. Priručnik za nastavnike. Beograd: Zavod za izdavanje udžbenika Socijalističke Republike Srbije. pp. 13–14.

{{cite conference}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Robert Elsie, A dictionary of Albanian religion, mythology and folk culture, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2001, ISBN 9781850655701, p. 79.

- ^ a b "ALBANCI". Enciklopedija Jugoslavije 2nd ed. Vol. Supplement. Zagreb: JLZ. 1984. p. 1.

- ^ Elsie, Robert (1986). "Paulus Angelus". Dictionary of Albanian Literature. New York/Westport/London: Greenwood Press. p. 4.

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, p. 183. "We may begin with the Venetic peoples, Veneti, Carni, Histri and Liburni, whose language set them apart from the rest of the Illyrians."

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992. ISBN 0631198075, p. 81. "In Roman Pannonia the Latobici and Varciani who dwelt east of the Venetic Catari in the upper Sava valley were Celtic but the Colapiani of the Colapis (Kulpa) valley were Illyrians..."

- ^ "Johann Thunmann: On the History and Language of the Albanians and Vlachs". Elsie.

- ^ Thunmann, Johannes E. "Untersuchungen uber die Geschichte der Oslichen Europaischen Volger". Teil, Leipzig, 1774.

- ^ Indo-European language and culture: an introduction By Benjamin W. Fortson Edition: 5, illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2004 ISBN 1405103167, 9781405103169

- ^ Stipčević, Alexander. Iliri (2nd edition). Zagreb, 1989 (also published in Italian as "Gli Illiri")

- ^ NGL Hammond The Relations of Illyrian Albania with the Greeks and the Romans. In Perspectives on Albania, edited by Tom Winnifrith, St. Martin’s Press, New York 1992

- ^ a b Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture By J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1997 ISBN 1884964982, 9781884964985

- ^ Thunman, Hahn, Kretschmer, Ribezzo, La Piana, Sufflay, Erdeljanovic and Stadtmuller referenced at Hamp see (The position of Albanian, E. Hamp 1963)

- ^ Jireček as referenced at Hamp see (The position of Albanian, E. Hamp 1963)

- ^ a b c d Demiraj, Shaban. Prejardhja e shqiptarëve në dritën e dëshmive të gjuhës shqipe.(Origin of Albanians through the testimonies of the Albanian language) Shkenca (Tirane) 1999

- ^ History of the Byzantine Empire, 324-1453 By Alexander A. Vasiliev Edition: 2, illustrated Published by Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1958 ISBN 0299809269, 9780299809263 (page 613)

- ^ History of the Balkans: Eighteenth and nineteenth centuries By Barbara Jelavich Edition: reprint, illustrated Published by Cambridge University Press, 1983 ISBN 0521274583, 9780521274586 (page 25)

- ^ The Indo-European languages By Anna Giacalone Ramat, Paolo Ramat Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1998 ISBN 041506449X, 9780415064491 (page 481)

- ^ a b c Madrugearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.146. [2]

- ^ Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture By J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1997 ISBN 1884964982, 9781884964985 page 11

- ^ a b c Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture By J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1997 ISBN 1884964982, 9781884964985 page 11 link [3]

- ^ Erik Hamp, The Position of Albanian, University of Chigaco, ..Jokl's Illyrian-Albanian correspondences (Albaner §3a) are probably the best known. Certain of these require comment...

- ^ a b Çabej, E. "Die alteren Wohnsitze der Albaner auf der Balkanhalbinsel im Lichte der Sprache und der Ortsnamen," VII Congresso internaz. di sciense onomastiche, 1961 241-251; Albanian version BUShT 1962:1.219-227

- ^ Çabej, Eqrem. Karakteristikat e huazimeve latine të gjuhës shqipe.(The characteristics of Latin Loans in Albanian language) SF 1974/2 (In German RL 1962/1) (13-51)

- ^ Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture By J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1997 ISBN 1884964982, 9781884964985 (page 11) borrowed words from Greek and Latin date back to before Christian era see also (page 9) Even very common words such as mik"friend"(<Lat. amicus) or këndoj"sing (<Lat. cantare) come from Latin and attest to a widespread intermingling of pre-Albanian and Balkan Latin speakers during the Roman period, roughfly from the second century BC to the fifth century AD.

- ^ Cimochowski, W. "Des recherches sur la toponomastique de l’Albanie," Ling. Posn. 8.133-45 (1960). On Durrës

- ^ In Tosk /a/ before a nasal has become a central vowel (shwa), and intervocalic /n/ has become /r/. These two sound changes have affected only the pre-Slav stratum of the Albanian lexicon, that is the native words and loanwords from Greek and Latin (page 23) Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World By Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Contributor Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Edition: illustrated Published by Elsevier, 2008 ISBN 0080877745, 9780080877747

- ^ The dialectal split into Geg and Tosk happened sometime after the region become Christianized in the fourth century AD; Christian Latin loanwords show Tosk rhotacism, such as Tosk murgu"monk" (Geg mungu) from Lat. monachus. (page 392) Indo-European language and culture: an introduction By Benjamin W. Fortson Edition: 5, illustrated Published by Wiley-Blackwell, 2004 ISBN 1405103167, 9781405103169

- ^ The Greek and Latin loans have undergone most of the far-reaching phonological changes which have so altered the shape of inherited words while Slavic and Turkish words do not show those changes. Thus Albanian must have acquired much of its present form by the time Slavs entered into Balkans in the fifth and sixth centuries AD (page 9)Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture By J. P. Mallory, Douglas Q. Adams Edition: illustrated Published by Taylor & Francis, 1997 ISBN 1884964982, 9781884964985

- ^ The river Shkumbin in central Albania historically forms the boundary between those two dialects, with the population on the north speaking varieties of Geg and the population on the south varieties of Tosk. (page 23) Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World By Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Contributor Keith Brown, Sarah Ogilvie Edition: illustrated Published by Elsevier,2008 ISBN 0080877745, 9780080877747

- ^ See also Hamp 1963 The isogloss is clear in all dialects I have studied, which embrace nearly all types possible. It must be relatively old, that is, dating back into the post-Roman first millennium. As a guess, it seems possible that this isogloss reflects a spread of the speech area, after the settlement of the Albanians in roughly their present location, so that the speech area straddled the Jireček Line.

- ^ Vickers, Miranda. The Albanians. I.B. Tauris, 1999, ISBN 960-210-279-9, p. 196. "From time to time official lists were published with pagan, so-called Illyrian or freshly minted names considered appropriate for the new breed of revolutionary Albanians."

- ^ Bank of Albania. Currency: Albanian coins in circulation, issue of 1995, 1996 and 2000. – Retrieved on 23 March 2009.

- ^ Bank of Albania. Currency: Banknotes in circulation. – Retrieved on 23 March 2009.

- ^ Turnock, David. The Making of Eastern Europe, from the Earliest Times to 1815. Taylor and Francis, 1988. p.137 [4]

- ^ a b Fine, JA. The Early medieval Balkans. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1991. p.11. [5]

- ^ a b The Cambridge ancient history by John Boederman,ISBN 0521224969,2002,page 848

- ^ The Illyrian Language

- ^ Madrugearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.147. [6]

- ^ Wilkes, J. J. The Illyrians. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1992, ISBN 0631198075, p. 278. "...likely identification seems to be with a Romanized population of Illyrian origin driven out by Slav settlements further north, the 'Romanoi' mentioned..."

- ^ Jirecek, Konstantin. "The history of the Serbians" (Geschichte der Serben), Gotha, 1911

- ^ Madrugearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.149. [7]

- ^ Xil,"An ancient language of the Balkans. Based upon geographical proximity, this is traditionally seen as the ancestor of Modern Albanian. It is more likely, however, that Thracian is Modern Albanian's ancestor, since both Albanian and Thracian belong to the satem group of Indo-European, while Illyrian belonged to the centum group. 2nd half of 1st Millennium BC - 1st half of 1st Millennium AD. "

- ^ Wilkes (1992): "Though almost nothing of it survives, except for names, the Illyrian language has figured prominently…" (p. 67)

- ^ A dictionary of the Roman Empire Oxford paperback reference,ISBN 0195102339,1995,page 202,"contact with the peoples of the Illyrian kingdom and at the Celticized tribes of the Delmatae"

- ^ Pannonia and Upper Moesia. A History of the Middle Danube Provinces of the Roman Empire. A Mocsy, S Frere

- ^ Stanley M. Burstein, Walter Donlan, Jennifer Tolbert Roberts, and Sarah B. Pomeroy. A Brief History of Ancient Greece: Politics, Society, and Culture. Oxford University Press, p. 255.

- ^ Epirus Vetus: The Archaeology of a Late Antique Province (Duckworth Archaeology) by William Bowden,2003,page 211: "... in the ninth century. Wilkes suggested that they represented a `Romanized population of Illyrian origin driven out by Slav settlements further north', ..."

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium (3-Volume Set) by Alexander P. Kazhdan,1991,page 248,"... were well fortified. In the 6th and 7th C. the romanized Thraco-Illyrian population was forced to settle in the mountains; they reappear ..."

- ^ Schramm, Gottfried, Anfänge des albanischen Christentums: Die frühe Bekehrung der Bessen und ihre langen Folgen (1994).

- ^ Madrugearu A, Gordon M. The wars of the Balkan peninsula. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. p.151. [8]

- ^ Vekony G. Dacians, Romans, Romanians. Matthia Corvinus, 2002

- ^ Eric P. Hamp, University of Chicago The Position of Albanian (Ancient IE dialects, Proceedings of the Conference on IE linguistics held at the University of California, Los Angeles, April 25–27, 1963, ed. By Henrik Birnbaum and Jaan Puhvel)

- ^ a b c d e Fine, JA. The Early medieval Balkans. Univ. of Michigan Press, 1991. p.11.

- ^ A short History of Kosovo; Chapter 2 Origins: Serbs, Albanians and Vlachs (1999), Ibid.

- ^ Hamp, Eric (1980) It [i.e. the Albanian language] can be said to be related more closely to Baltic and Slavic than to anything else, and certainly not to be close to Thracian see http://www.lituanus.org/1993_2/93_2_05.htm

- ^ Noel Malcolm, A short History of Kosovo, Chapter 2.

- ^ a b c Malcolm, Noel. "Kosovo, a short history". London: Macmillan, 1998, p. 22-40.

- ^ Five Roman emperors: Vespasian, Titus, Domitian, Nerva, Trajan, A.D. 69-117 - by Bernard William Henderson - 1969, page 278,"At Thermidava he was warmly greeted by folk quite obviously Dacians"

- ^ The Geography by Ptolemy, Edward Luther Stevenson,1991,page 36

- ^ a b Ethnic continuity in the Carpatho-Danubian area by Elemér Illyés,1988,ISBN-0880331461,page 223

- ^ Belledi et al. (2000) Maternal and paternal lineages in Albania and the genetic structure of Indo-European populations

- ^ http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:Kqj5uZRfjIUJ:hrcak.srce.hr/file/15462+%22HLA+Class+I+Polymorphism+in+the+Albanian+Population%22&hl=en&ct=clnk&cd=1

- ^ a b c Cruciani, F; La Fratta, R; Trombetta, B; Santolamazza, P; Sellitto, D; Colomb, EB; Dugoujon, JM; Crivellaro, F; Benincasa, T; et al. (2007). "Tracing Past Human Male Movements in Northern/Eastern Africa and Western Eurasia: New Clues from Y-Chromosomal Haplogroups E-M78 and J-M12". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 24 (6): 1300–1311. doi:10.1093/molbev/msm049. PMID 17351267.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help) Also see Supplementary Data. - ^ a b Battaglia; Fornarino, S; Al-Zahery, N; Olivieri, A; Pala, M; Myres, NM; King, RJ; Rootsi, S; Marjanovic, D; et al. (2008). "Y-chromosomal evidence of the cultural diffusion of agriculture in southeast Europe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 17 (6): 820–30. doi:10.1038/ejhg.2008.249. PMID 19107149.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Bird, Steven (2007). "Haplogroup E3b1a2 as a Possible Indicator of Settlement in Roman Britain by Soldiers of Balkan Origin". Journal of Genetic Genealogy. 3 (2).

- ^ a b Semino; et al. (2000). "The Genetic Legacy of Paleolithic Homo sapiens sapiens in Extant Europeans: A Y Chromosome Perspective" (PDF). Science. Vol. 290. pp. 1155–59. doi:10.1126/science.290.5494.1155. PMID 11073453.

{{cite news}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Cruciani, F; La Fratta, R; Santolamazza, P; Sellitto, D; Pascone, R; Moral, P; Watson, E; Guida, V; Colomb, EB; et al. (2004). "Phylogeographic Analysis of Haplogroup E3b (E-M215) Y Chromosomes Reveals Multiple Migratory Events Within and Out Of Africa" (PDF). American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (5): 1014–1022. doi:10.1086/386294. PMC 1181964. PMID 15042509.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|last=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ a b c d e Peričic; Lauc, LB; Klarić, IM; Rootsi, S; Janićijevic, B; Rudan, I; Terzić, R; Colak, I; Kvesić, A; et al. (2005). "High-resolution phylogenetic analysis of southeastern Europe traces major episodes of paternal gene flow among Slavic populations". Mol. Biol. Evol. Vol. 22, no. 10. pp. 1964–75. doi:10.1093/molbev/msi185. PMID 15944443.

{{cite news}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Latest designations can be found on the [www.isogg.org ISOGG] website. In some articles this is described as I-P37.2 not including I-M26.

- ^ Rootsi et al. (2004) Phylogeography of Y-Chromosome Haplogroup I Reveals Distinct Domains of Prehistoric Gene Flow in Europe

- ^ a b c Cardos G., Stoian V., Miritoiu N., Comsa A., Kroll A., Voss S., Rodewald A. (2004 Romanian Society of Legal Medicine) Paleo-mtDNA analysis and population genetic aspects of old Thracian populations from South-East of Romania

- ^ Malcolm N (2002) "Myths of Albanian national identity: Some key elements". In Albanian identities, Schwandner-Sievers S, Fischer JB eds., Indiana University Press. p. 77

- ^ Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers and Bernd Jürgen Fischer, editors of Albanian Identities: Myth and History (Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2002), present papers resulting from the London Conference held in 1999 entitled "The Role of Myth in the History and Development of Albania". The "Pelasgian" myth of Albanians as the most ancient community in southeastern Europe is among those explored in Noel Malcolm's essay, "Myths of Albanian National Identity: Some Key Elements, As Expressed in the Works of Albanian Writers in America in the Early Twentieth Century". The introductory essay by Stephanie Schwandner-Sievers establishes the context of the "Pelasgian Albanian" mythos, applicable to Eastern Europe generally, in terms of the longing for a stable identity in a rapidly opening society.