Adolescence: Difference between revisions

ClueBot NG (talk | contribs) m Reverting possible vandalism by 2607:FB90:2B03:A584:A030:2BFA:E6DB:DAEF to version by Callanecc. Report False Positive? Thanks, ClueBot NG. (2768662) (Bot) |

THE VHS GUIDE TO TEENS |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{pp-vandalism|small=yes}} |

|||

{{About|the video format}} |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=July 2011}} |

|||

<!--There is a reliable source for the name "Video Home System". PLEASE DO NOT CHANGE THE NAME without at least providing an equally reliable source.--> |

|||

{{Infobox media |

|||

|name = Video Home System |

|||

|logo = [[File:VHS logo.svg|90px|VHS logo]] |

|||

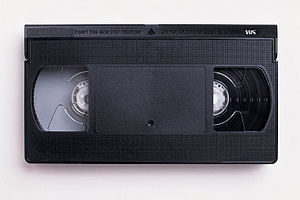

|image = [[File:VHS-cassette.jpg|300px|border]] |

|||

|caption = Top view of a VHS cassette |

|||

|type = [[Video recording]] media |

|||

|encoding = [[Frequency modulation|FM]] on [[magnetic tape]]; PAL, NTSC, SECAM |

|||

|common lengths = 120, 160 minutes (Standard Play Mode) |

|||

|unusual lengths = 5, 10, 15, 30, 60, 90, 130, 180, 190, 200, 210 minutes (Standard Play Mode) |

|||

|start date = 1976 |

|||

|end date = 2008 |

|||

|capacity = |

|||

|read = [[Helical scan]] |

|||

|write = Helical scan |

|||

|standard = |

|||

|owner = [[JVC]] (Victor Company of Japan) |

|||

|use = [[Home video]], [[Home movies|home movie]], [[educational]], [[feature film]]s |

|||

}} |

|||

<!-- Please do not insert claims that the original name was "Vertical Helical Scan" or that that is an authoritative alternate name. See [[talk:VHS/FAQ]] ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:VHS/FAQ ). Thanks. --> |

|||

[[File:VHS recorder, camera and cassette.jpg|thumb|right|VHS recorder, camcorder and cassette.]] |

|||

The '''Video Home System'''<ref>[http://www.ieeeghn.org/wiki/index.php/Milestones:Development_of_VHS,_a_World_Standard_for_Home_Video_Recording,_1976 IEEE History Center: Development of VHS], cites the original name as "Video Home System", from an article by Yuma Shiraishi, one of its inventors. Retrieved December 28, 2006.</ref><ref name="PopSciNov77">{{cite web|url = http://books.google.com/books?id=bwEAAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA81&lpg=PA81&dq=HR-3300+HR-3300U&source=bl&ots=DpPL1JjUqy&sig=55H7STDNQ3Utttm8udw2sakJ4io&hl=en&sa=X&ei=4Y5vUM_4IuK6igKlmoHoDg&ved=0CDMQ6AEwAw#v=onepage&q&f=false|title = Popular Science|work = google.com|publisher = Times Mirror Magazine inc.|date = November 1977}}</ref> ('''VHS''')<ref name="latimes1">{{cite news|url=http://articles.latimes.com/2008/dec/22/entertainment/et-vhs-tapes22 |title=VHS era is winding down |publisher=Articles.latimes.com |date=2008-12-22 |accessdate=2011-07-11 |first=Geoff |last=Boucher}}</ref> is a [[technical standard|standard]] for [[consumerization|consumer-level]] [[analog recording|analog]] [[video recording]] on tape [[Videocassette|cassettes]]. Developed by [[JVC|Victor Company of Japan]] (JVC) in the early 1970s, it was released in Japan in late 1976 and in the USA in early 1977. |

|||

From the 1950s, [[magnetic tape]] video recording became a major contributor to the television industry, via the first commercialized [[video tape recorder]]s (VTRs). At that time, the devices were used only in expensive professional environments such as [[television studio]]s and medical imaging ([[fluoroscopy]]). In the 1970s, videotape entered home use, creating the [[home video]] industry and changing the economics of the [[television]] and [[film|movie]] businesses. The television industry viewed [[videocassette recorder]]s (VCRs) as having the power to disrupt their business, while television users viewed the VCR as the means to take control of their hobby.<ref>Glinis, Shawn Michael. "VCRs: The End of TV as Ephemera." University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, May 2015. Web. 09 Oct. |

|||

2015.</ref> |

|||

In the 1980s and 1990s, at the peak of VHS's popularity, there were [[videotape format war]]s in the home video industry. Two of the formats, VHS and [[Betamax]], received the most media exposure. VHS eventually won the war; dominating 60 percent of the North American market by 1980<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.videomaker.com/article/f22/17178-the-rapid-evolution-of-the-consumer-camcorder|title=The Rapid Evolution of the Consumer Camcorder|access-date=2016-08-06}}</ref><ref name="beta_end">{{Cite web|url=http://www.techspot.com/news/62733-sony-finally-decides-time-kill-betamax.html|title=Sony finally decides it's time to kill Betamax|language=en-us|access-date=2016-08-06}}</ref> and succeeding as the dominant home video format throughout the tape [[Magnetic media|media]] period.<ref name="jchyung">{{cite web|url=http://besser.tsoa.nyu.edu/impact/f96/Projects/jchyung/ |title=Lessons Learned from the VHS – Betamax War |publisher=Besser.tsoa.nyu.edu |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> |

|||

[[Optical disc]] formats later began to offer better quality than analog consumer video tape such as standard and super-VHS. The earliest of these formats, [[LaserDisc]], was not widely adopted. However, after the introduction of the [[DVD]] format in 1997, VHS's market share began to decline.<ref name="wp-gonewiththerewind">[http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/26/AR2005082600332.html ''"Parting Words For VHS Tapes, Soon to Be Gone With the Rewind"''], Washington Post, August 28, 2005.</ref><ref>{{cite news| url= http://washingtontimes.com/news/2003/jun/20/20030620-113258-1104r/| title=It's unreel: DVD rentals overtake videocassettes| newspaper=The Washington Times| date=2003-06-20| accessdate=2010-06-02| location=Washington, D.C. }}</ref> By 2008, DVD had achieved mass acceptance and replaced VHS as the preferred low end method of distribution.<ref name="VHS era is winding down">[{{cite web|url=http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/news/la-et-vhs-tapes22-2008dec22,0,5852342.story |title=VHS era is winding down|work=Latimes.com}}</ref>{{TOC limit|3}} |

|||

== History == |

|||

<!-- please do not insert claims that the original name was "Vertical Helical Scan" or that that is an authoritative alternate name. See [[talk:VHS/FAQ]] ( https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Talk:VHS/FAQ ). Thanks. --> |

|||

=== Prior to VHS === |

|||

{{details|Video tape recorder}} |

|||

After several attempts by other companies, the first commercially successful VTR, the [[Quadruplex videotape|Ampex VRX-1000]], was introduced in 1956 by [[Ampex|Ampex Corporation]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cedmagic.com/history/ampex-commercial-vtr-1956.html |title=AMPEX VRX-1000 – The First Commercial Videotape Recorder in 1956 | publisher=CED Magic |accessdate=2013-03-24}}</ref> At a price of US$50,000 in 1956 (over $400,000 in 2016's inflation), and US$300 (over $2,000 in 2016's inflation) for a 90-minute reel of tape, it was intended only for the professional market. |

|||

[[Kenjiro Takayanagi]], a television broadcasting pioneer then working for JVC as its vice president, saw the need for his company to produce VTRs for the Japan market, and at a more affordable price. In 1959, JVC developed a two-head video tape recorder, and by 1960 a color version for professional broadcasting.<ref name="takayanagi">{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=TOMOmmrvwCcC|title=The History of Television 1942-2000, pg 169 |publisher=Albert Abramson |year=2003 |accessdate=2013-03-24|isbn=9780786432431}}</ref> In 1964, JVC released the DV220, which would be the company's standard VTR until the mid-1970s. |

|||

In 1969 JVC collaborated with [[Sony Corporation]] and [[Matsushita Electric]] (Matsushita was then parent company of [[Panasonic]] and is now known by that name, also majority stockholder of JVC until 2008) in building a video recording standard for the Japanese consumer.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ce.org/Press/CEA_Pubs/941.asp |title=VCR |publisher=Ce.org |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> The effort produced the [[U-matic]] format in 1971, which was the first format to become a unified standard. |

|||

U-matic was successful in business and some broadcast applications (such as electronic news-gathering), but due to cost and limited recording time very few of the machines were sold for home use. |

|||

Soon after, Sony and Matsushita broke away from the collaboration effort, in order to work on video recording formats of their own. Sony started working on [[Betamax]], while Matsushita started working on [[VX (videocassette format)|VX]]. JVC released the CR-6060 in 1975, based on the U-matic format. Sony and Matsushita also produced U-matic systems of their own. |

|||

=== VHS development === |

|||

In 1971, JVC engineers Yuma Shiraishi and Shizuo Takano put together a team to develop a consumer-based VTR.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/1992/01/20/world/shizuo-takano-68-an-engineer-who-developed-vhs-recorders.html |title=Shizuo Takano, 68, an Engineer Who Developed VHS Recorders |work=The New York Times |date=1992-01-20 |accessdate=2011-07-11 |first=Andrew |last=Pollack}}</ref> |

|||

By the end of 1971 they created an internal diagram titled "VHS Development Matrix", which established twelve objectives for JVC's new VTR.<ref name="rickmaybury">{{cite web|url=http://www.rickmaybury.com/Altarcs/homent/he97/vhstoryhtm.htm |title=VHS STORY – Home Taping Comes of Age |publisher=Rickmaybury.com |date=1976-09-07 |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> These included: |

|||

* The system must be compatible with any ordinary television set. |

|||

* Picture quality must be similar to a normal air broadcast. |

|||

* The tape must have at least a two-hour recording capacity. |

|||

* Tapes must be interchangeable between machines. |

|||

* The overall system should be versatile, meaning it can be scaled and expanded, such as connecting a video camera, or dub between two recorders. |

|||

* Recorders should be affordable, easy to operate and have low maintenance costs. |

|||

* Recorders must be capable of being produced in high volume, their parts must be interchangeable, and they must be easy to service. |

|||

In early 1972 the commercial video recording industry in Japan took a financial hit. JVC cut its budgets and restructured its video division, shelving the VHS project. However, despite the lack of funding, Takano and Shiraishi continued to work on the project in secret. By 1973 the two engineers had produced a functional prototype.<ref name="rickmaybury" /> |

|||

=== Competition with Betamax === |

|||

In 1974, the Japanese [[Ministry of International Trade and Industry]] (MITI), desiring to avoid [[consumer confusion]], attempted to force the Japanese video industry to standardize on just one home video recording format.<ref>{{cite web|last=Bylund |first=Anders |url=http://arstechnica.com/gadgets/guides/2010/01/is-the-end-of-the-format-wars-upon-us.ars |title=The format wars: of lasers and (creative) destruction |publisher=Arstechnica.com |date=2010-01-04 |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> Later, Sony had a functional prototype of the [[Betamax]] format, and was very close to releasing a finished product. With this prototype, Sony persuaded the MITI to adopt Betamax as the standard, and allow it to license the technology to other companies.<ref name="rickmaybury" /> |

|||

JVC believed that an [[open standard]], with the format shared among competitors without licensing the technology, was better for the consumer. To prevent the MITI from adopting Betamax, JVC worked to convince other companies, in particular [[Panasonic|Matsushita]] (Japan's largest electronics manufacturer at the time, marketing its products under the National brand in most territories and the Panasonic brand in North America, and JVC's majority stockholder), to accept VHS, and thereby work against Sony and the MITI.<ref name="howells">John Howells. "The Management of Innovation and Technology: The Shaping of Technology and Institutions of the Market Economy" [hardcopy], pg 76-81</ref> Matsushita agreed, primarily out of concern that Sony might become the leader in the field if its proprietary Betamax format was the only one allowed to be manufactured. Matsushita also regarded Betamax's one-hour recording time limit as a disadvantage.<ref name="howells" /> |

|||

Matsushita's backing of JVC persuaded [[Hitachi]], [[Mitsubishi]], and [[Sharp Corporation|Sharp]]<ref>[http://www.mediacollege.com/video/format/compare/betamax-vhs.html Media College] "The Betamax vs VHS Format War", by Dave Owen, published: 2005-05-01</ref> to back the VHS standard as well.<ref name="rickmaybury" /> Sony's release of its Betamax unit to the Japanese market in 1975 placed further pressure on the MITI to side with the company. However, the collaboration of JVC and its partners was much stronger, and eventually led the MITI to drop its push for an industry standard. JVC released the first VHS machines in Japan in late 1976, and in the United States in early 1977. |

|||

Sony's Betamax competed with VHS throughout the late 1970s and into the 1980s (see [[Videotape format war]]). Betamax's major advantages were its smaller cassette size, higher video quality, and earlier availability but its shorter recording time proved to be a major shortcoming.<ref name="beta_end" /> |

|||

Originally, Beta I machines using the [[NTSC]] television standard were able to record one hour of programming at their standard tape speed of 1.5 [[inches per second]] (ips).<ref name="100greatinventions" /> The first VHS machines could record for two hours, due to both a slightly slower tape speed (1.31 ips.)<ref name="100greatinventions">{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=SPFiZ31mTnUC|title=100 Greatest Inventions, ppg 288-289 |publisher=Citadel Press Books |year=2003 |accessdate=2012-10-06|isbn=9780806524047}}</ref> and significantly longer tape. Betamax's smaller-sized cassette limited the size of the reel of tape, and could not compete with VHS's two-hour capability by extending the tape length.<ref name="100greatinventions" /> Instead, Sony had to slow the tape down to 0.787 ips (Beta II) in order to achieve two hours of recording in the same cassette size.<ref name="100greatinventions" /> This reduced Betamax's once-superior video quality to worse than VHS when comparing two-hour recording.{{citation needed|date=November 2015}} Sony eventually released an extended Beta cassette (Beta III) which allowed NTSC Betamax to break the two-hour limit, but by then VHS had already won the format battle.<ref name="100greatinventions" /> |

|||

Additionally, VHS had a "far less complex tape transport mechanism" than Betamax, and VHS machines were faster at rewinding and fast-forwarding than their Sony counterparts.<ref name="Parekh">{{Cite book|title = Principles of Multimedia|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=TaNmc2IdNVwC|publisher = Tata McGraw-Hill Education|date = 2006-01-01|isbn = 9780070588332|first = Ranjan|last = Parekh}}</ref> |

|||

In machines using the [[PAL]] and [[SECAM]] television formats, Beta's running time was similar to VHS, the quality at least as good, and the format battle was not fought on running time. |

|||

== Initial releases of VHS-based devices == |

|||

[[File:JVC-HR-3300U.jpg|thumb|JVC HR-3300U VIDSTAR – the United States version of the JVC HR-3300. It is virtually identical to the Japan version. Japan's version showed the "Victor" name, and didn't use the "VIDSTAR" name.]] |

|||

The first [[videocassette recorder|VCR]] to use VHS was the [[JVC HR-3300|Victor HR-3300]], and was introduced by the president of JVC in Japan on September 9, 1976.<ref name="nipponsei">{{cite web|url=http://www.nipponsei.jp/n-hajimete/n-hajimete009.html |title=Always Helpful! Full of Information on Recording Media "Made in Japan After All" |publisher=Nipponsei.jp |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.totalrewind.org/vhs/H_3300.htm |title=JVC HR-3300 |publisher=Totalrewind.org |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> JVC started selling the HR-3300 in [[Akihabara]], Tokyo, Japan on October 31, 1976.<ref name="nipponsei" /> Region-specific versions of the JVC HR-3300 were also distributed later on, such as the HR-3300U in the United States, and HR-3300EK in the United Kingdom. The United States received its first VHS-based VCR – the RCA VBT200 on August 23, 1977.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cedmagic.com/history/vbt200.html |title=CED in the History of Media Technology |publisher=Cedmagic.com |date=1977-08-23 |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> The RCA unit was designed by Matsushita, and was the first VHS-based VCR manufactured by a company other than JVC. It was also capable of recording four hours in LP (long play) mode. The United Kingdom later received its first VHS-based VCR – the Victor HR-3300EK in 1978.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/industry_sectors/media/article785934.ece|archiveurl=https://web.archive.org/web/20070225011304/http://business.timesonline.co.uk/tol/business/industry_sectors/media/article785934.ece |title=Fast-forward to oblivion as VCRs take only 5% of market|archivedate=February 25, 2007|work=timesonline.co.uk}}</ref> |

|||

[[Quasar (brand)|Quasar]] and [[General Electric]] would follow-up with VHS-based VCRs – all designed by Matsushita.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://vintageelectronics.betamaxcollectors.com/panasonicvhsgallery.html |title=Panasonic VHS VCR Gallery |publisher=Vintageelectronics.betamaxcollectors.com |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> By 1999, Matsushita alone produced just over half of all Japanese VCRs.<ref name="Cusumano">Cusumano, MA, Mylonadis, Y. and Rosenbloom, RS (1992) "Strategic Manoeuvring and Mass Market Dynamics: VHS over Beta", Business History Review, pg 88</ref> |

|||

== Technical details == |

|||

=== Cassette and tape design === |

|||

[[File:VHS cassette tape 12.JPG|thumb|Top view of VHS with front casing removed]] |

|||

The VHS cassette is a 187 mm wide, 103 mm deep, 25 mm thick (7{{frac|3|8}} × 4{{frac|1|16}} × 1 inch) plastic shell held together with five [[Phillips head]] screws. The flip-up cover that protects the tape has a built-in latch with a push-in toggle on the right side (bottom view image). The VHS cassette also includes an anti-despooling mechanism consisting of several plastic parts between the plastic spools, near the front of the tape (white and black in the top view). The spool latches are released by a push-in lever within a 6.35 mm (¼ inch) hole accessed from the bottom of the cassette, 19 mm (¾ inch) inwards from the edge label. |

|||

There is a clear tape leader at both ends of the tape to provide an optical auto-stop for the VCR transport mechanism. A light source is inserted into the cassette through the circular hole in the center of the underside when loaded in the VCR, and two [[photodiode]]s are located to the left and right sides of where the tape exits the cassette. When the clear tape reaches one of these, enough light will pass through the tape to the photodiode to trigger the stop function; in more sophisticated machines it will start rewinding the cassette when the trailing end is detected. Early VCRs used an [[incandescent bulb]] as the light source, which regularly failed and caused the VCR to erroneously think that a cassette is loaded when empty, or would detect the blown bulb and stop functioning completely. Later designs use an infrared [[light emitting diode|LED]] which had a much longer lifetime. |

|||

The recording media is a 12.7 mm (½ inch) wide, approximately 800 foot long Oxide-coated Mylar<ref>Noble, Jem. "VHS: A Posthumanist Aesthetics of Recording and Distribution." OxfordHandbooks. Oxford Handbooks, Dec. |

|||

2013. Web. 30 Sept. 2015.</ref> [[magnetic tape]] that is wound between two spools, allowing it to be slowly passed over the various playback and recording heads of the [[video cassette recorder]]. The tape speed for "Standard Play" mode (see below) is 3.335 cm/s (1.313 ips) for [[NTSC]], 2.339 cm/s (0.921 ips) for [[PAL]]—or just over 2.0 and 1.4 metres (6 ft 6.7 in and 4 ft 7.2 in) per minute respectively. |

|||

=== Tape loading technique === |

|||

[[File:VHS diagram.svg|left|thumb|200px|VHS M-loading system.]] |

|||

As with almost all cassette-based videotape systems, VHS machines pull the tape out from the cassette shell and wrap it around the inclined head drum which rotates at 1798.2 rpm in NTSC machines<ref>{{cite web |

|||

|url=http://electronics.howstuffworks.com/vcr2.htm |

|||

|title=How VCRs Work |

|||

|date=2011-02-10 |

|||

|accessdate=2011-02-10 |

|||

|first=Marshall |

|||

|last=Brain |

|||

|publisher=HowStuffWorks |

|||

|page=7 |

|||

}}</ref> and at 1500 rpm for PAL, one complete rotation of the head corresponding to one video frame. VHS uses an "M-loading" system, also known as M-lacing, where the tape is drawn out by two threading posts and wrapped around more than 180 degrees of the head drum (and also other [[tape transport]] components) in a shape roughly approximating the letter [[M]]. |

|||

=== Recording capacity === |

|||

[[File:VCR load.jpg|thumb|The interior of a modern VHS [[VCR]] showing the drum and tape.]] |

|||

A VHS cassette holds a maximum of about 430 m (1,410 ft.) of tape at the lowest acceptable tape thickness, giving a maximum playing time of about four hours in a T-240/DF480 for [[NTSC]] and five hours in an E-300 for [[PAL]] at "standard play" (SP) quality. More frequently however, VHS tapes are thicker than the required minimum to avoid complications such as jams or tears in the tape.<ref name="Parekh" /> Other speeds include "long play" (LP), and "extended play" (EP) or "super long play" (SLP) (standard on NTSC; rarely found on PAL machines). For NTSC, LP and EP/SLP doubles and triples the recording time accordingly, but these speed reductions cause a reduction in video quality – from the normal 250 lines in SP, to 230 analog lines horizontal in LP and even less in EP/SLP. The slower speeds cause a very noticeable reduction in linear (non-hifi) audio track quality as well, as the linear tape speed becomes much lower than what is commonly considered a satisfactory minimum for audio recording. |

|||

=== Tape lengths === |

|||

Both [[Multi-standard television|NTSC and PAL/SECAM]] VHS cassettes are physically identical (although the signals recorded on the tape are incompatible). However, as tape speeds differ between NTSC and PAL/SECAM, the playing time for any given cassette will vary accordingly between the systems. In order to avoid confusion, manufacturers indicate the playing time in minutes that can be expected for the market the tape is sold in. It is perfectly possible to record and play back a blank T-XXX tape in a PAL machine or a blank E-XXX tape in an NTSC machine, but the resulting playing time will be different from that indicated. |

|||

To calculate the playing time for a T-XXX tape in a PAL machine, use this formula: |

|||

PAL/SECAM Recording Time = T-XXX in minutes * (1.426) |

|||

To calculate the playing time for an E-XXX tape in an NTSC machine, use this formula: |

|||

NTSC Recording Time = E-XXX in minutes * (0.701) |

|||

Some new Panasonic NTSC/ATSC recorders also include a XP mode which is not part of the official specification. It enables recordings at double the SP speed, such that a T-180 holds 1.5 hours.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www2.panasonic.com/consumer-electronics/shop/Blu-ray-38-DVD/DVD-Players-Recorders/model.DMR-EZ48VK.S_11002_7000000000000005702#tabsection |title=Panasonic DMR-EZ48VK - DMR-EZ48VK DVD Recorder with Upconversion |publisher=.panasonic.com |date=2010-10-10 |accessdate=2011-12-09}}</ref> |

|||

* E-XXX indicates playing time in minutes for PAL or SECAM in SP and LP speeds. |

|||

* T-XXX indicates playing time in minutes for NTSC or PAL-M in SP, LP, and EP/SLP speeds. |

|||

* SP is Standard Play, LP is Long Play (½ speed, equal to recording time in DVHS "HS" mode), EP/SLP is extended/super long play (⅓ speed) which was primarily released into the NTSC market. |

|||

{| class="wikitable" |

|||

|+ Common tape lengths |

|||

|- |

|||

! rowspan="2" | Tape label |

|||

(nominal length in minutes) |

|||

! colspan="2" | Tape length |

|||

! colspan="3" | Rec. time (NTSC) |

|||

! colspan="3" | Rec. time (PAL) |

|||

|- |

|||

! m !! ft |

|||

! SP !! LP !! EP/SLP !! SP !! LP |

|||

|- |

|||

! ''NTSC market'' |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#FFE8F0" |

|||

! T-20 |

|||

| 44 || 145 || 22 min || 44 min || 66 min (1h 06) || 31.5 min || 63 min |

|||

|- |

|||

! T-30 (typical VHS-C) |

|||

| 63 || 207 || 31.5 min || 63 min (1h 03) || 95 min (1h 35) || 45 min || 90 min (1h 30) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#FFE8F0" |

|||

! T-45 |

|||

| 94 || 310 || 47 min || 94 min (1h 34) || 142 min (2h 22) || 67 min (1h 07) || 135 min (2h 15) |

|||

|- |

|||

! T-60 |

|||

| 126 || 412 || 63 min (1h 03) || 126 min (2h 06)|| 188 min (3h 08) || 89 min (1h 29) || 179 min (2h 59) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#FFE8F0" |

|||

! T-90 |

|||

| 186 || 610 || 93 min (1h 33) || 186 min (3h 06)|| 279 min (4h 39) || 132 min (2h 12) || 265 min (4h 25) |

|||

|- |

|||

! T-120 / DF240 |

|||

| 247 || 811 || 124 min (2h 04) || 247 min (4h 07) || 371 min (6h 11) || 176 min (2h 56) || 352 min (5h 52) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#FFE8F0" |

|||

! T-140 |

|||

| 287.5 || 943 || 144 min (2h 24) || 287 min (4h 47) || 431 min (7h 11) || 204.5 min (3h 24.5) || 404.5 min (6h 44.5) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#FFE8F0" |

|||

! T-150 / DF300 |

|||

| 316.5 || 1040 || 158 min (2h 38) || 316 min (5h 16) || 475 min (7h 55) || 226 min (3h 46) || 452 min (7h 32) |

|||

|- |

|||

! T-160 |

|||

| 328 || 1075 || 164 min (2h 44) || 327 min (5h 27) || 491 min (8h 11) || 233 min (3h 53) || 467 min (7h 47) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#FFE8F0" |

|||

! T-180 / DF-360 |

|||

| 369 || 1210 || 184 min (3h 04) || 369 min (6h 09)|| 553 min (9h 13) || 263 min (4h 23) || 526 min (8h 46) |

|||

|- |

|||

! T-200 |

|||

| 410 || 1345 || 205 min (3h 25) || 410 min (6h 50)|| 615 min (10h 15) || 292 min (4h 52) || 584 min (9h 44) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#FFE8F0" |

|||

! T-210 / DF420 |

|||

| 433 || 1420 || 216 min (3h 36) || 433 min (7h 13) || 649 min (10h 49) || 308 min (5h 08) || 617 min (10h 17) |

|||

|- |

|||

! T-240 / DF480 |

|||

| 500 || 1640 || 250 min (4h 10) || 500 min (8h 20) || 749 min (12h 29) || 356 min (5h 56) || 712 min (11h 52) |

|||

|- |

|||

! ''PAL market'' |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#E8F0FF" |

|||

! E-30 (typical VHS-C) |

|||

| 45 || 148 || 22.5 min || 45 min || 68 min (1h 08) || 32 min || 64 min (1h 04) |

|||

|- |

|||

! E-60 |

|||

| 88 || 290 || 44 min || 88 min (1h 28) || 133 min (2h 13) || 63 min (1h 03) || 126 min (2h 06) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#E8F0FF" |

|||

! E-90 |

|||

| 131 || 429 || 65 min (1h 05) || 131 min (2h 11) || 196 min (3h 16) || 93 min (1h 33) || 186 min (3h 06) |

|||

|- |

|||

! E-120 |

|||

| 174 || 570 || 87 min (1h 27) || 174 min (2h 54) || 260 min (4h 20) || 124 min (2h 04) || 248 min (4h 08) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#E8F0FF" |

|||

! E-150 |

|||

| 216 || 609 || 108 min (1h 49) || 227 min (3h 37) || 324 min (5h 24) || 154 min (2h 34) || 308 min (5h 08) |

|||

|- |

|||

! E-180 |

|||

| 259 || 849 || 129 min (2h 09) || 259 min (4h 18) || 388 min (6h 28) || 184 min (3h 04) || 369 min (6h 09) |

|||

|- |

|||

! E-195 |

|||

| 279 || 915 || 139 min (2h 19) || 279 min (4h 39) || 418 min (6h 58) || 199 min (3h 19) || 397 min (6h 37) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#E8F0FF" |

|||

! E-200 |

|||

| 289 || 935 || 144 min (2h 24) || 284 min (4h 44) || 428 min (7h 08) || 204 min (3h 24) || 405 min (6h 45) |

|||

|- |

|||

! E-210 |

|||

| 304 || 998 || 152 min (2h 32) || 304 min (5h 04) || 456 min (7h 36) || 217 min (3h 37) || 433 min (7h 13) |

|||

|- |

|||

! E-240 |

|||

| 348 || 1142 || 174 min (2h 54) || 348 min (5h 48) || 522 min (8h 42) || 248 min (4h 08) || 496 min (8h 16) |

|||

|- bgcolor = "#E8F0FF" |

|||

! E-270 |

|||

| 392 || 1295 || 196 min (3h 16) || 392 min (6h 32) || 589 min (9h 49) || 279 min (4h 39) || 559 min (9h 19) |

|||

|- |

|||

! E-300 |

|||

| 435 || 1427 || 217 min (3h 37) || 435 min (7h 15) || 652 min (10h 52) || 310 min (5h 10) || 620 min (10h 20) |

|||

|} |

|||

As manufacturers tend to err on the side of generosity when cutting tapes to length (for example, a 412 ft "T-60" is in fact nearly 63 minutes long) in order to account for manufacturing errors and slight differences in deck spindle speed and spool-out, it is quite likely that some of these cassettes—for example, DF420 and E300, or E30 and T20—are actually manufactured to the same true length internally and are merely stamped with the same nominal length for sales purposes. |

|||

Several other defined lengths of cassette entered mass production for both markets, but were either used only for professional duplication purposes (often pushing the limit of how much tape of a particular grade/thickness could fit into a standard cassette, in order to hold films that could not quite fit onto a shorter standard size without risking poorer quality or reliability by switching to a thinner grade), or failed to find popularity amongst home consumers because of a glut of tape length choices or poor value for money—e.g. T130/135/140, T168, E150, E270, and more besides. |

|||

=== Copy Protection === |

|||

As VHS was designed to facilitate recording from various sources, including television broadcasts or other VCR units, content producers quickly found that home users were able to use the devices to copy videos from one tape to another. Despite the generation loss, this was regarded as a widespread problem, which the members of the [[Motion Picture Association of America]] (MPAA) claimed caused them great financial losses. In response, several companies developed technologies to protect copyrighted VHS tapes from casual duplication by home users. |

|||

The most popular method was [[Macrovision]], produced by a company of the same name. According to Macrovision, "The technology is applied to over 550 million videocassettes annually and is used by every [[MPAA]] movie studio on some or all of their videocassette releases. Over 220 commercial duplication facilities around the world are equipped to supply Macrovision videocassette copy protection to rights owners." Also, "The study found that over 30% of VCR households admit to having unauthorized copies, and that the total annual revenue loss due to copying is estimated at $370,000,000 annually."<ref name="howstuffworks-313">{{cite web |url=http://electronics.howstuffworks.com/question313.htm |title=How does copy protection on a video tape work? |work=HowStuffWorks.com |date=2000-04-01 }}</ref> The system was first used in copyrighted movies beginning with the 1984 film ''[[The Cotton Club (film)|The Cotton Club]]''.<ref name="deatley19850907">{{cite news | url=http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=lc8vAAAAIBAJ&sjid=1Y0DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5630%2C870934 | title=VCRs put entertainment industry into fast-forward frenzy | work=The Free Lance-Star | date=1985-09-07 | agency=Associated Press | accessdate=25 January 2015 | author=De Atley, Richard | pages=12-TV}}</ref> |

|||

Macrovision copy protection saw refinement throughout its years, but has always worked by essentially introducing deliberate errors into a protected VHS tape's output video stream. These errors in the output video stream are ignored by most televisions, but will interfere with re-recording of programming by a second VCR. The first version of Macrovision introduces voltage spikes during the [[vertical blanking interval]], which occurs between the video fields. These high levels confuse the [[automatic gain control]] circuit in most VHS VCRs, leading to varying brightness levels in an output video, but are ignored by the TV as they are out of the frame-display period. "Level II" Macrovision uses a process called "colorstriping," which inverts the analog signal's colorburst period and causes off-color bands to appear in the picture. Level III protection added additional colorstriping techniques to further degrade the image.<ref name="anarchivism-rip-vhs">{{cite web |url=http://anarchivism.org/w/How_to_Rip_VHS |title=How to Rip VHS |work=Anarchivism |date=2012-12-14 }}</ref> |

|||

These protection methods worked well to defeat analog-to-analog copying by VCRs of the time. Products capable of digital video recording are mandated by law to include features which detect Macrovision encoding of input analog streams, and reject copying of the video. Both intentional and false-positive detection of Macrovision protection has frustrated archivists who wish to copy now-fragile VHS tapes to a digital format for preservation. |

|||

== Recording process == |

|||

[[File:VCR in action-01.ogg|thumb|left|A close-up process of how the magnetic tape in a VHS cassette is being pulled from the cassette shell to the head drum of the VCR.]] |

|||

[[File:VHS-diagonal-helical-recording.jpg|right|thumb|300px|This illustration demonstrates the helical wrap of the tape around the head drum, and shows the points where the video, audio and control tracks are recorded.]] |

|||

The recording process in VHS consists of the following steps, in this order: |

|||

* The tape is pulled from the supply reel by a capstan and pinch roller, similar to those used in audio tape recorders. |

|||

* The tape passes across the erase head, which wipes any existing recording from the tape. |

|||

* The tape is wrapped around the head drum, using a little more than 180 degrees of the drum. |

|||

* One of the heads on the spinning drum records one field of video onto the tape, in one diagonally oriented track. |

|||

* The tape passes across the audio and control head, which records the control track and the linear audio track or tracks. |

|||

* The tape is wound onto the take-up reel due to torque applied to the reel by the machine. |

|||

=== Erase head === |

|||

The erase head is fed by a high level, high frequency AC signal that overwrites any previous recording on the tape.<ref>[http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/audio/tape.html Tape Recording], Georgia State University</ref> Without this step, the new recording cannot be guaranteed to completely replace any old recording that might have been on the tape. |

|||

=== Video recording === |

|||

[[File:Kopftrommel 2.jpg|right|thumb|300px|A typical VHS head drum containing two tape heads. (1) is the upper head, (2) is the tape heads, and (3) is the head amplifier.]] [[File:VHS Video Head Assembly.jpg|thumb|The underside of a typical 4-head VHS head assembly showing the head chips.]] |

|||

[[File:RCA AutoShot VHS Camcorder.jpg|290px|thumb|right|A typical RCA (Model CC-4371) Full-Size VHS Camcorder with a built-in three-inch color LCD screen. The tiltable LCD screen is rare on full-size VHS camcorders; only the smaller [[VHS-C]] camcorders are more common to have a tiltable LCD screen on some units.]] |

|||

The tape path then carries the tape around the spinning head drum, wrapping it around a little more than 180 degrees (called the ''omega'' transport system) in a [[helix|helical]] fashion, assisted by the slanted tape guides. The head rotates constantly at approximately<ref>The 1800 rpm tape head speed, and corresponding field period time, etc., quoted in this article for NTSC machines are based on the old black and white RS-170 standard. When this was adapted for color under the NTSC standard the actual field time was altered to 1/59.94 of a second, so the actual VHS head rotation speed is accordingly 1798.2 rpm. The pre-color timings are quoted here for simplicity. The corresponding numbers here for PAL are, on the other hand, exact, as PAL's field rate is exactly 1/50th of a second.</ref> 1800 rpm in NTSC machines, exactly 1500 in PAL, each complete rotation corresponding to one frame of video. |

|||

Two [[tape head]]s are mounted on the cylindrical surface of the drum, 180 degrees apart from each other, so that the two heads "take turns" in recording. The rotation of the head drum, combined with the relatively slow movement of the tape, results in each head recording a track oriented at a diagonal with respect to the length of the tape. This is referred to as [[helical scan]] recording. |

|||

To maximize the use of the tape, the video tracks are recorded very close together to each other. To reduce [[crosstalk]] between adjacent tracks on playback, an [[azimuth recording]] method is used: The gaps of the two heads are not aligned exactly with the track path. Instead, one head is angled at plus seven degrees from the track, and the other at minus seven degrees. This results, during playback, in destructive interference of the signal from the tracks on either side of the one being played. |

|||

Each of the diagonal-angled tracks is a complete TV picture field, lasting 1/60th of a second (1/50th on PAL) on the display. One [[tape head]] records an entire picture field. The adjacent track, recorded by the second tape head, is another 1/60th or 1/50th of a second TV picture field, and so on. Thus one complete head rotation records an entire NTSC or PAL frame of two fields. |

|||

The original VHS specification had only two video heads. Later models implemented at least one more pair of heads, which were used at (and optimized for) the EP tape speed. In machines supporting VHS HiFi (described later), yet another pair of heads was added to handle the VHS HiFi signal. |

|||

The high tape-to-head speed created by the rotating head results in a far higher bandwidth than could be practically achieved with a stationary head. |

|||

VHS tapes have approximately 3 [[Megahertz|MHz]] of video [[Bandwidth (signal processing)|bandwidth]] and 400 kHz of chroma bandwidth. The [[Luminance (video)|luminance]] (black and white) portion of the video is recorded as a [[frequency modulation|frequency modulated]], with a down-converted |

|||

"[[Heterodyne#Heterodyning in analog videotape recording|color under]]" [[Chrominance|chroma]] (color) signal recorded directly at the baseband. Each helical track contains a single field ('even' or 'odd' field, equivalent to half a frame) encoded as an analog [[raster scan]], similar to analog TV broadcasts. The horizontal resolution is 240 lines per picture height, or about 320 lines across a scan line, and the vertical resolution (the number of scan lines) is the same as the respective analog TV standard (576 for [[PAL]] or 486 for [[NTSC]]; usually, somewhat fewer scan lines are actually visible due to [[overscan]]). In modern-day digital terminology, NTSC VHS is roughly equivalent to 333×480 pixels luma and 40×480 chroma resolutions (333×480 pixels=159,840 pixels or 0.16MP (1/6 of a MegaPixel)).,<ref>{{cite book |last=Taylor|first=Jim|title=DVD demystified|publisher=McGraw-Hill Professional|year=2005|isbn=0-07-142396-6|pages=9–36|url= http://books.google.com/books?id=ikxuL2aX9cAC}}</ref> while PAL VHS offers the equivalent of about 335×576 pixels luma and 40×240 chroma (the vertical chroma resolution of PAL is limited by the PAL color delay line mechanism). |

|||

JVC would counter 1985's SuperBeta with VHS HQ, or High Quality. The frequency modulation of the VHS luminance signal is limited to 3 megahertz, which makes higher resolutions technically impossible even with the highest-quality recording heads and tape materials, but an HQ branded deck includes luminance noise reduction, chroma noise reduction, white clip extension, and improved sharpness circuitry. The effect was to increase the apparent horizontal resolution of a VHS recording from 240 to 250 analog (equivalent to 333 pixels from left-to-right, in digital terminology). The major VHS [[Original Equipment Manufacturer|OEM]]s resisted HQ due to cost concerns, eventually resulting in JVC reducing the requirements for the HQ brand to "white clip extension plus one other improvement." |

|||

In 1987, JVC introduced a new format called [[S-VHS|Super VHS]] (often known as S-VHS) which extended the bandwidth to over 5 megahertz, yielding 420 analog horizontal (560 pixels left-to-right). Most Super VHS recorders can play back standard VHS tapes, but not vice versa. S-VHS was designed for higher resolution, but failed to gain popularity outside Japan because of the high costs of the machines and tapes.<ref name="Parekh" /> Because of the limited user base, Super VHS was never picked up to any significant degree by manufacturers of pre-recorded tapes, although it was used extensively in the low-end professional market for filming and editing. |

|||

=== Audio recording === |

|||

After leaving the head drum, the tape passes over the stationary audio and control head. This records a control track at the bottom edge of the tape, and one or two linear audio tracks along the top edge. |

|||

==== Original linear audio system ==== |

|||

In the original VHS specification, audio was recorded as [[baseband]] in a single linear track, at the upper edge of the tape, similar to how an audio [[compact cassette]] operates. The recorded frequency range was dependent on the linear tape speed. For the VHS SP mode, which already uses a lower tape speed than the compact cassette, this resulted in a mediocre frequency response of roughly 100 Hz to 10 kHz for NTSC;{{citation needed|date=March 2014}} frequency response for PAL VHS with its lower standard tape speed was somewhat worse. The [[signal-to-noise ratio]] (SNR) was an acceptable 42 dB. Both parameters degraded significantly with VHS's longer play modes, with EP/NTSC frequency response peaking at 4 kHz. |

|||

Audio cannot be recorded on a VHS tape without recording a video signal, even in the audio dubbing mode. If there is no video signal to the VCR input, most VCRs will record black video as well as generate a control track while the audio is being recorded. Some early VCRs would record audio without a control track signal, but this was of little practical use since the absence of a control track signal meant that the linear tape speed was irregular during playback. |

|||

More expensive decks offered stereo audio recording and playback. Linear stereo, as it was called, fit two independent channels in the same space as the original mono audiotrack. While this approach preserved acceptable backward compatibility with monoaural audio heads, the splitting of the audio track degraded the signal's SNR to the point that audible tape hiss was objectionable at normal listening volume. To counteract tape hiss, decks applied [[Dolby noise-reduction system|Dolby B noise reduction]] for recording and playback. Dolby B dynamically boosts the mid-frequency band of the audio program on the recorded medium, improving its signal strength relative to the tape's background noise floor, then attenuates the mid-band during playback. Dolby B is not a transparent process, and Dolby-encoded program material will exhibit an unnatural mid-range emphasis when played on non-Dolby capable VCRs. |

|||

High-end consumer recorders took advantage of the linear nature of the audio track, as the audio track could be erased and recorded without disturbing the video portion of the recorded signal. Hence, "audio dubbing" and "video dubbing", where either the audio or video are re-recorded on tape (without disturbing the other), were supported features on [[prosumer]] [[linear video editing]]-decks. Without dubbing capability, an audio or video edit could not be done in-place on master cassette, and requires the editing output be captured to another tape, incurring generational loss. |

|||

Studio film releases began to emerge with linear stereo audiotracks in 1982. From that point onward nearly every home video release by Hollywood featured a Dolby-encoded linear stereo audiotrack. However, linear stereo was never popular with equipment makers or consumers. |

|||

==== Tracking adjustment and index marking ==== |

|||

Another linear [[control track|''control'' track]], at the tape's lower edge, holds pulses that mark the beginning of every frame of video; these are used to fine-tune the tape speed during playback, so that the high speed rotating heads remained exactly on their helical tracks rather than somewhere between two adjacent tracks (known as "[[video tape tracking|tracking]]"). Since good tracking depends on precise distances between the rotating drum and the fixed control/audio head reading the linear tracks, which usually varies by a couple of micrometers between machines due to manufacturing tolerances, most VCRs offer tracking adjustment, either manual or automatic, to correct such mismatches. |

|||

The control track is also used to hold ''index marks'', which were normally written at the beginning of each recording session, and can be found using the VCR's ''index search'' function: this will fast-wind forward or backward to the ''n''th specified index mark, and resume playback from there. At times, higher-end VCRs provided functions for the user to manually add and remove these marks<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.crutchfield.com/S-PFiOFC1Dt8s/learn/learningcenter/home/vcr_glossary.html|title=VCRs Glossary|author=Loren Barstow|work=Crutchfield}}</ref><ref>[http://www.retrevo.com/support/JVC-HR-S7300U-VCRs-manual/id/318ag718/t/2/ JVC HR-S7300 manual]: features list: ''"..., Index Search, Manual Index Mark/Erase ..."''</ref> — so that, for example, they coincide with the actual start of the [[television program]] — but this feature later became hard to find.{{citation needed|date=July 2014}} |

|||

By the late 1990s, some high-end VCRs offered more sophisticated indexing. For example, Panasonic's Tape Library system assigned an ID number to each cassette, and logged recording information (channel, date, time and optional program title entered by the user) both on the cassette and in the VCR's memory for up to 900 recordings (600 with titles).<ref>[http://www.elektroda.pl/rtvforum/instrukcjeobslugi?id=2176 Panasonic Video Cassette Recorder NV-HS960 Series Operating Instructions], VQT8880, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd.</ref> |

|||

==== Hi-Fi audio system ==== |

|||

Around 1984, JVC added ''Hi-Fi'' audio to VHS (model HR-D725U, in response to Betamax's introduction of Beta Hi-Fi.) Both VHS Hi-Fi and Betamax Hi-Fi delivered flat full-range frequency response (20 Hz to 20 kHz), excellent 70 dB [[signal-to-noise ratio]] (in consumer space, second only to the [[compact disc]]), [[dynamic range]] of 90 dB, and [[professional audio]]-grade channel separation (more than 70 dB). VHS Hi-Fi audio is achieved by using audio frequency modulation (AFM), modulating the two stereo channels (L, R) on two different frequency-modulated carriers and embedding the combined modulated audio signal pair into the video signal. To avoid crosstalk and interference from the primary video carrier, VHS's implementation of AFM relied on a form of magnetic recording called ''depth [[multiplexing]]''. The modulated [[Sound recording|audio]] carrier pair was placed in the hitherto-unused frequency range between the luminance and the color carrier (below 1.6 MHz), and recorded first. Subsequently, the video head erases and re-records the video signal (combined luminance and color signal) over the same tape surface, but the video signal's higher center frequency results in a shallower magnetization of the tape, allowing both the video and residual AFM audio signal to coexist on tape. (PAL versions of Beta Hi-Fi use this same technique). During playback, VHS Hi-Fi recovers the depth-recorded AFM signal by subtracting the audio head's signal (which contains the AFM signal contaminated by a weak image of the video signal) from the video head's signal (which contains only the video signal), then demodulates the left and right audio channels from their respective frequency carriers. The end result of the complex process was audio of outstanding fidelity, which was uniformly solid across all tape-speeds (EP, LP or SP.) Since JVC had gone through the complexity of ensuring Hi-Fi's backward compatibility with non-Hi-Fi VCRs, virtually all studio home video releases produced after this time contained Hi-Fi audio tracks, in addition to the linear audio track. Under normal circumstances, all Hi-Fi VHS VCRs will record Hi-Fi and linear audio simultaneously to ensure compatibility with VCRs without Hi-Fi playback, though only early high-end Hi-Fi machines provided linear stereo compatibility. |

|||

Due to the path followed by the video and Hi-Fi audio heads being striped and discontinuous—unlike that of the linear audio track—head-switching is required to provide a continuous audio signal. While the video signal can easily hide the head-switching point in the invisible vertical retrace section of the signal, so that the exact switching point is not very important, the same is obviously not possible with a continuous audio signal that has no inaudible sections. Hi-Fi audio is thus dependent on a much more exact alignment of the head switching point than is required for non-HiFi VHS machines. Misalignments may lead to imperfect joining of the signal, resulting in low-pitched buzzing.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://stason.org/TULARC/entertainment/audio/general/14-18-Is-VHS-Hi-Fi-sound-perfect-Is-Beta-Hi-Fi-sound-perfec.html14.18|title=14.18 Is VHS Hi-Fi sound perfect? Is Beta Hi-Fi sound perfect?|work=stason.org}}</ref> The problem is known as "head chatter", and tends to increase as the audio heads wear down. |

|||

The sound quality of Hi-Fi VHS stereo is comparable to the quality of CD audio, particularly when recordings were made on high-end or professional VHS machines that have a manual audio recording level control. This high quality compared to other consumer audio recording formats such as [[compact cassette]] attracted the attention of amateur and hobbyist recording artists. [[Home recording]] enthusiasts occasionally recorded high quality stereo [[Audio mixing (recorded music)|mixdown]]s and [[master recording]]s from [[multitrack recording|multitrack]] audio tape onto consumer-level Hi-Fi VCRs. However, because the VHS Hi-Fi recording process is intertwined with the VCR's video-recording function, advanced editing functions such as audio-only or video-only dubbing are impossible. A short-lived alternative to the hifi feature for recording mixdowns of hobbyist audio-only projects was a [[PCM adaptor]] so that high-bandwidth digital video could use a grid of black-and-white dots on an analog video carrier to give pro-grade digital sounds though [[Digital Audio Tape|DAT]] tapes made this obsolete. |

|||

Some VHS decks also had a "simulcast" switch, allowing users to record an external audio input along with off-air pictures. Some televised concerts offered a stereo simulcast soundtrack on FM radio and as such, events like ''[[Live Aid]]'' were recorded by thousands of people with a full stereo soundtrack despite the fact that stereo TV broadcasts were some years off (especially in regions that adopted [[NICAM]]). Other examples of this included network television shows such as ''[[Friday Night Videos]]'' and [[MTV]] for its first few years in existence. Likewise, some countries, most notably [[South Africa]], provided alternate language audio tracks for TV programming through an FM radio simulcast. |

|||

The considerable complexity and additional hardware limited VHS Hi-Fi to high-end decks for many years. While linear stereo all but disappeared from home VHS decks, it was not until the 1990s that Hi-Fi became a more common feature on VHS decks. Even then, most customers were unaware of its significance and merely enjoyed the better audio performance of the newer decks. |

|||

== Variations == |

|||

[[File:JVC-VHS Cassette001.JPG|thumb|[[JVC|Victor]] S-VHS (left) and S-VHS-C (right).]] |

|||

=== Super-VHS / ADAT / SVHS-ET === |

|||

{{main|S-VHS|D-VHS}} |

|||

Several improved versions of VHS exist, most notably [[S-VHS|Super-VHS (S-VHS)]], an analog video standard with improved video bandwidth. S-VHS improved the horizontal luminance resolution to 400 lines (versus 250 for VHS/Beta and 500 for DVD). The audio-system (both linear and AFM) is the same. S-VHS made little impact on the home market, but gained dominance in the camcorder market due to its superior picture quality. |

|||

The [[ADAT]] format provides the ability to record multitrack digital audio using S-VHS media. JVC also developed SVHS-ET technology for its Super-VHS camcorders and VCRs, which simply allows them to record Super VHS signals onto lower-priced VHS tapes, albeit with a slight blurring of the image. Nearly all later Super-VHS camcorders and VCRs have SVHS-ET ability. |

|||

=== VHS-C / Super VHS-C === |

|||

{{main|VHS-C}} |

|||

Another variant is [[VHS-C|VHS-Compact (VHS-C)]], originally developed for portable VCRs in 1982, but ultimately finding success in palm-sized [[camcorder]]s. The longest tape available for NTSC holds 60 minutes in SP mode and 180 minutes in EP mode. Since VHS-C tapes are based on the same magnetic tape as full-size tapes, they can be played back in standard VHS players using a mechanical adapter, without the need of any kind of signal conversion. The magnetic tape on VHS-C cassettes is wound on one main spool and uses a gear wheel to advance the tape.<ref name="Parekh" /> |

|||

The adapter is mechanical, although early examples were motorized, with a battery. It has an internal hub to engage with the VCR mechanism in the location of a normal full-size tape hub, driving the gearing on the VHS-C cassette. Also, when a VHS-C cassette is inserted into the adapter, a small swing-arm pulls the tape out of the miniature cassette to span the standard tape path distance between the guide rollers of a full-size tape. This allows the tape from the miniature cassette to use the same loading mechanism as that from the standard cassette. |

|||

Super VHS-C or [[S-VHS]] Compact was developed by [[JVC]] in 1987. S-VHS provided an improved luminance and chrominance quality, yet S-VHS recorders were compatible with VHS tapes.<ref>{{cite book | last = Damjanovski | first = Vlado |

|||

| title = CCTV |

|||

| publisher=Butterworth-Heinemann |

|||

| year = 2005 | isbn = 0-7506-7800-3 | page= 238 |

|||

| url= http://books.google.com/books?id=MQZQIFaOhgoC}}</ref> |

|||

Sony was unable to shrink its Betamax form any further, so instead developed Video8/Hi8 which was in direct competition with the VHS-C/S-VHS-C format throughout the 80s, 90s, and 2000s. Ultimately neither format "won" and both have been superseded by digital high definition equipment. |

|||

=== VHS single === |

|||

''VHS single'', also known as ''videotape single'' or ''Video 45s'' (a play on the term "45" when used to describe [[Gramophone record|vinyl records]]) is a [[single (music)|music single]], using a standard-sized VHS cartridge. The format has existed since the early 1980s. In 1983, British [[synthpop]] band [[The Human League]] released the UK's first commercial video single on both VHS and Betamax as "[[The Human League Video Single (1983)|The Human League Video Single]]".<ref>Virgin Records 1983</ref> It was not a huge commercial success due to the high retail price of £10.99, compared to £1.99 for a vinyl single. |

|||

The VHS single format gained higher levels of mainstream popularity when [[Madonna (entertainer)|Madonna]] released "[[Justify My Love]]" as a video single in 1990 following the blacklisting of the video by [[MTV]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,285759,00.html|title=''Justify My Love'' was too raunchy in 1990|work=Entertainment Weekly's EW.com}}</ref> [[U2]] also released "[[Numb (U2 song)|Numb]]", the [[lead single]] from their 1993 album ''[[Zooropa]]'' as a video single.<ref name="numbsingle">{{cite AV media notes| title = Numb CD single |url= http://www.discogs.com/release/275973 | others = U2| year = 1993 | type = liner| publisher = [[Island Records|Island]]| location = [[New York City]], [[United States|USA]]}}</ref><ref name="numbvinyl">{{cite AV media notes| title = Numb vinyl single |url= http://www.discogs.com/release/643316 | others = U2| year = 1993 | type = liner| publisher = [[Island Records|Island]]| location = [[New York City]], [[United States|USA]]}}</ref> |

|||

Despite the success of these releases, the video single struggled as its releases were relatively rare, the technology slowly being superseded first by [[CD Video]] (which proved unsuccessful due to the cost of capable [[LaserDisc]] players to play the video portion), music CDs with computer-accessible video files, then, by the early 2000s, by both [[DVD single]]s and CD+DVD releases. VHS tapes were however marketed to distribute music video compilations. |

|||

=== W-VHS / Digital-VHS (high-definition) === |

|||

{{main|W-VHS|D-VHS}} |

|||

[[W-VHS]] allowed recording of [[Multiple sub-nyquist sampling Encoding system|MUSE]] Hi-Vision ''analog'' high definition television, which was broadcast in Japan from 1989 until 2007. The other improved standard, called [[D-VHS|Digital-VHS (D-VHS)]], records digital high definition video onto a VHS form factor tape. D-VHS can record up to 4 hours of ATSC digital television in 720p or 1080i formats using the fastest record mode (equivalent to VHS-SP), and up to 49 hours of lower-definition video at slower speeds.<ref>{{cite book |

|||

|title=Newnes Guide to Television and Video Technology |

|||

|author=Eugene Trundle |

|||

|page=377}}</ref> |

|||

=== D9 === |

|||

{{main|Digital-S}} |

|||

There is also a JVC-designed component digital professional production format known as [[Digital-S]], or officially under the name D9, that uses a VHS form factor tape and essentially the same mechanical tape handling techniques as an S-VHS recorder. This format is the least expensive format to support a [[Sel-Sync]] pre-read for [[video editing]]. This format competed with Sony's [[Digital Betacam]] in the professional and broadcast market, although in that area Sony's Betacam family ruled supreme, in contrast to the outcome of the VHS/Betamax domestic format war. It has now been superseded by high definition formats. |

|||

=== Accessories === |

|||

Shortly after the introduction of the VHS format, [[VHS tape rewinder]]s were developed. These devices served the sole purpose of rewinding VHS tapes. Proponents of the rewinders argued that the use of the rewind function on the standard VHS player would lead to wear and tear of the transport mechanism. The rewinder would rewind the tapes smoothly and also normally do so at a faster rate than the standard rewind function on VHS players. However some rewinder brands did have some frequent abrupt stops, which occasionally led to tape damage. |

|||

Some devices were marketed which allowed a [[personal computer]] to use a VHS recorder as a [[data backup]] device. The most notable of these was [[ArVid]], widely used in Russia and [[Commonwealth of Independent States|CIS]] states. Similar systems were manufactured in the United States by [[Corvus (company)|Corvus]] and [[Alpha Microsystems]],<ref>''[http://books.google.com/books?id=RS8EAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA56&ots=2DE04Dma4F&pg=PA56#v=onepage&q=&f=false Videotrax: New System To Back Up Hard Disks].'' InfoWorld, May 26, 1986.</ref> and in the UK by ''Backer'' from Danmere Ltd. |

|||

== Signal standards == |

|||

VHS can record and play back all varieties of [[Broadcast television system|analog television signals]] in existence at the time VHS was devised. However, a machine must be designed to record a given standard. Typically, a VHS machine can only handle signals using the same standard as the country it was sold in. This is because some parameters of analog broadcast TV are not applicable to VHS recordings, the number of VHS tape recording format variations is smaller than the number of broadcast TV signal variations—for example, analog TVs and VHS ''machines'' (except multistandard devices) are not interchangeable between the UK and Germany, but VHS ''tapes'' are. The following tape recording formats exist in conventional VHS (listed in the form of standard/lines/frames): |

|||

* [[SECAM]]/625/25 (SECAM, French variety) |

|||

* [[SECAM|MESECAM]]/625/25 (most other SECAM countries, notably the former Soviet Union and Middle East) |

|||

* [[NTSC]]/525/30 (Most parts of Americas, Japan, South Korea) |

|||

* [[PAL]]/525/30 (i.e., [[PAL-M]], Brazil) |

|||

* [[PAL]]/625/25 (most of Western Europe, Australia, New Zealand, many parts of Asia such as China and India, some parts of South America such as Argentina, Uruguay and the Falklands, and Africa) |

|||

Note that PAL/625/25 VCRs allow playback of SECAM (and MESECAM) tapes with a [[monochrome]] picture, and vice versa, as the line standard is the same. |

|||

Since the 1990s dual and multi-standard VHS machines, able to handle a variety of VHS-supported video standards, became more common. For example, VHS machines sold in Australia and Europe could typically handle PAL, MESECAM for record and playback, and NTSC for playback only on suitable TVs. Dedicated multi-standard machines can usually handle all standards listed, and some high-end models could convert the content of a tape from one standard to another [[on the fly]] during playback by using a built-in standards converter. |

|||

S-VHS is only implemented as such in PAL/625/25 and NTSC/525/30; S-VHS machines sold in SECAM markets record internally in PAL, and convert between PAL and SECAM during recording and playback. S-VHS machines for the Brazilian market record in NTSC and convert between it and PAL-M. |

|||

A small number of VHS decks are able to decode [[closed captioning|closed captions]] on prerecorded video cassettes. A smaller number still are able, additionally, to record [[Subtitle (captioning)|subtitles]] transmitted with world standard [[teletext]] signals (on pre-digital services), simultaneously with the associated program. S-VHS has a sufficient resolution to record teletext signals with relatively few errors.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.transdiffusion.org/2016/01/07/teletext-time-travel |title=Teletext time travel |publisher=transdiffusion.org |date=2016-01-07 |accessdate=2016-01-19}}</ref> |

|||

==Logo== |

|||

[[File:VHS logo.svg|thumb|The first VHS Logo]] |

|||

The VHS logo was commissioned by JVC and introduced with the JVC HR-3300 in 1976. It uses the Lee font, designed by Leo Weisz.<ref>{{cite web|last1=Simonson|first1=Mark|title=Industrial Art Methods, December 1972|url=http://www.marksimonson.com/notebook/P12|accessdate=10 August 2014}}</ref> |

|||

== Uses in marketing == |

|||

VHS was popular for long-form content, such as feature films or documentaries, as well as short-play content, such as music videos, in-store videos, teaching videos, distribution of lectures and talks, and demonstrations. VHS instruction tapes were sometimes included with various products and services, including exercise equipment, kitchen appliances, and computer software.{{Citation needed|date = November 2015}} |

|||

== VHS vs. Betamax == |

|||

{{Main|Videotape format war}} |

|||

[[File:Betavhs2.jpg|thumb|Size comparison between Betamax (top) and VHS (bottom) videocassettes.]] |

|||

VHS was the winner of a protracted and somewhat bitter format war during the late 1970s and early 1980s against Sony's Betamax format as well as other formats of the time.<ref name="jchyung" /> |

|||

Betamax was widely perceived at the time as the better format, as the cassette was smaller in size, and Betamax offered slightly better video quality than VHS – it had lower video noise, less luma-chroma [[Crosstalk (electronics)|crosstalk]], and was marketed as providing pictures superior to those of VHS. However, the sticking point for both consumers and potential licensing partners of Betamax was the total recording time.<ref name="howells" /> To overcome the recording limitation, Beta II speed (two-hour mode, NTSC regions only) was released in order to compete with VHS's two-hour SP mode, thereby reducing Betamax's horizontal resolution to 240 lines (vs 250 lines).<ref>{{cite web |author=Video Interchange |title=Video History |url=http://www.videointerchange.com/video-history.htm#BetaMax |accessdate=2007-08-20 }}</ref> In turn, the extension of VHS to VHS HQ produced 250 lines (vs 240 lines), so that overall a typical Betamax/VHS user could expect virtually identical resolution. (Very high-end Betamax machines still supported recording in the Beta I mode and some in an even higher resolution Beta Is (Beta I Super HiBand) mode, but at a maximum single-cassette run time of 1:40 [with an L-830 cassette].) |

|||

Because Betamax was released more than a year before VHS, it held an early lead in the format war. However, by 1981, United States' Betamax sales had dipped to only 25-percent of all sales.<ref>{{cite web |first=Helge |last=Moulding |title=The Decline and Fall of Betamax |url=http://tafkac.org/products/beta_vs_vhs.html |accessdate=2007-08-20 }}</ref> There was debate between experts over the cause of Betamax's loss. Some, including Sony's founder Akio Morita, say that it was due to Sony's licensing strategy with other manufacturers, which consistently kept the overall cost for a unit higher than a VHS unit, and that JVC allowed other manufacturers to produce VHS units license-free, thereby keeping costs lower.<ref name="mediacollege">{{cite web|url=http://www.mediacollege.com/video/format/compare/betamax-vhs.html |title=The Betamax vs VHS Format War |publisher=Mediacollege.com |date=2008-01-08 |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> Others say that VHS had better marketing, since the much larger electronics companies at the time (Matsushita, for example) supported VHS.<ref name="howells" /> |

|||

== Decline == |

|||

{{Multiple issues|section=yes| |

|||

{{Update|section|date=April 2014}} |

|||

{{globalize/US|section|date=July 2015}} |

|||

}} |

|||

The VHS VCR was a mainstay in television-equipped American and European living rooms for more than 20 years from its introduction in 1977. The home television recording market, as well as the camcorder market, has since transitioned to digital recording on solid-state memory cards. The introduction of the DVD format to American consumers in March 1997 triggered the market share decline of VHS.<ref name="wp-gonewiththerewind"/> |

|||

Though 94.5 million Americans still owned VHS format VCRs in 2005,<ref name="wp-gonewiththerewind" /> market share continued to drop. Several retail chains in the United States and Europe announced they would stop selling VHS equipment throughout the mid-2000s.<ref>{{cite news|url= http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/4031223.stm|title=Death of video recorder in sight |work=BBC News | date=2004-11-22 | accessdate=2010-01-06}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url= http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/06/14/AR2005061401794.html|title=As DVD Sales Fast-Forward, Retailers Reduce VHS Stock | work=The Washington Post | first=Mark | last=Chediak | date=2005-06-15 | accessdate=2010-05-27}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://money.cnn.com/2005/06/13/news/fortune500/walmart_vhs/index.htm?cnn=yes |title=Wal-Mart said to stop selling VHS |publisher=CNN | date=2005-06-13 | accessdate=2010-05-27}}</ref> The last film to be released on the VHS format in the United States was ''[[Eragon (film)|Eragon]]'' in 2007. In 2008, Distribution Video Audio Inc., the last major American supplier of pre-recorded VHS tapes, shipped its final truckload of tapes to stores in America.<ref name="VHS era is winding down"/> |

|||

In the U.S., no major retailers stock VHS home-video releases any longer, focusing only on DVD and Blu-ray Disc technology. Additionally, all of the major Hollywood studios no longer issue releases on VHS. However, there have been a few exceptions. ''[[The House of the Devil]]'' was released on VHS in 2010 as an Amazon-exclusive deal, in keeping with the film's intent to mimic 1980s horror films.<ref>[http://www.slashfilm.com/cool-stuff-the-house-of-the-devil-vhsdvd-combo-pack/ Cool Stuff: The House of the Devil VHS Tape / DVD Combo Pack]</ref> Also, the horror film ''[[V/H/S/2]]'' was released as a combo in North America that included a VHS tape in addition to a Blu-ray and a DVD copy on September 24, 2013.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://dailydead.com/vhs2-coming-to-blu-ray-dvd-and-vhs/ | title= *Updated* V/H/S/2 Coming to Blu-ray, DVD, and VHS}}</ref> |

|||

==Modern usage== |

|||

Despite the discontinuation of VHS in the United States, VHS recorders and blank tapes were still sold at stores in other developed countries prior to [[digital television transition]]s.<ref>{{cite news|title=Statue to mark digital switchover|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/cumbria/6996402.stm|accessdate=8 April 2016|work=BBC|date=15 September 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|title=Millions still buying analogue TVs and video recorders despite digital switchover plans|url=http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-519769/Millions-buying-analogue-TVs-video-recorders-despite-digital-switchover-plans.html|accessdate=5 April 2016|work=Daily Mail|date=27 February 2008}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Using Video Recorders after the Digital TV Switchover|url=http://www.switchhelp.co.uk/faq_video.html|website=switchhelp.co.uk|accessdate=5 April 2016}}</ref> As an acknowledgement of the continued usage of VHS, Panasonic announced the world's first dual deck VHS-Blu-ray player in 2009.<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www2.panasonic.com/webapp/wcs/stores/servlet/prModelDetail?storeId=11301&catalogId=13251&itemId=322744&modelNo=Content01072009023243932&surfModel=Content01072009023243932|title=Panasonic expanded 2009 Blu-ray lineup with the world's first VHS-Blu-ray player}}</ref> The last standalone JVC VHS-only unit was produced on October 28, 2008.<ref>{{cite web|last=Elliott|first=Amy-Mae|title=JVC last to stop production of standalone VHS players|date=2008-10-28|url=http://www.pocket-lint.com/news/18759/jvc-stops-production-vhs-players|accessdate=2008-10-31}}</ref> JVC, and other manufacturers, continued to make combination DVD+VHS units even after the decline of VHS. |

|||

Despite the decline in both VHS players and programming on VHS machines, they are still owned in some U.S. and Europe households. Those who still use or hold on to VHS do so for a number of reasons, including its alleged nostalgic value, its ease of use in recording, the fact that certain media still only exist in VHS format, their videos of personal events in their life are on VHS, or they are collectors of VHS releases. Expatriate communities in the United States also obtain video content from their native countries in VHS format.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2012/05/29/nyregion/for-some-new-york-immigrants-vhs-is-king-for-movie-rentals.html?_r=1 |title= For Movies, Some Immigrants Still Choose to Hit Rewind | work=The New York Times | first=Kirk |last=Semple |date=May 28, 2012}}</ref> |

|||

== Successors == |

|||

=== VCD === |

|||

{{see also|Video CD}} |

|||

The [[Video CD]] (VCD) was created in 1993, becoming an alternative medium for video, in a CD-sized disc. Though occasionally showing [[compression artifact]]s and [[color banding]] that are common discrepancies in digital media, the durability and longevity of a VCD depends on the production quality of the disc, and its handling. The data stored digitally on a VCD theoretically does not degrade (in the analog sense like tape). In the disc player, there is no physical contact made with either the data or label sides. And, when handled properly, a VCD will last a long time. |

|||

Since a VCD can only hold 74 minutes of video, a movie exceeding that mark has to be divided into two or more discs. |

|||

=== DVD === |

|||

{{see also|DVD-Video}} |

|||

The [[DVD-Video]] format was introduced first, in 1996, in Japan, to the United States in March 1997 (''test marketed'') and mid-late 1998 in Europe and Australia. |

|||

Despite DVD's better quality (typical horizontal resolution of 480 versus 250 lines per picture height), and the availability of standalone DVD recorders, |

|||

VHS is still used in home recording of video content. <!--This sentence should probably be updated, but when did VHS fall out of use as a home recording method? This sentence is very very outdated now, it should be changes as soon as possible.--> The commercial success of DVD recording and re-writing has been hindered by a number of factors including: |

|||

*A reputation for being temperamental and unreliable, as well as the risk of scratches and hairline cracks.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://desktopvideo.about.com/od/creatingdvds/f/dvdnoburn.htm |title=Why Won't My DVDs Burn |publisher=Desktopvideo.about.com |date=2011-03-21 |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> |

|||

*Incompatibilities in playing discs recorded on a different manufacturer's machines to that of the original recording machine.<ref>{{cite web|first=Jim |last=Taylor |url=http://dvddemystified.com/dvdfaq.html#1.41 |title=Why doesn't disc X work in player Y? |publisher=Dvddemystified.com |accessdate=2011-07-11}}</ref> |

|||

*Shorter recording time: VHS tape can record approximately twelve hours on a T-240/DF480 tape in EP, versus DVD which can record up to six hours on a single-layer disc. |

|||

*Compression artifacts: [[MPEG-2]] video compression can result in visible artifacts such as [[macroblocking]], [[mosquito noise]] and [[ringing artifacts|ringing]] which become accentuated in extended recording modes (more than three hours on a [[DVD-5]] disc). Standard VHS will not suffer from any of these problems, all of which are characteristic of certain digital video compression systems (see [[Discrete cosine transform]]) but VHS will result in reduced luminance and chroma resolution, which makes the picture look horizontally blurred (resolution decreases further with LP and EP recording modes).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dilife.wikispaces.com/The+Slow+Decline+of+the+VHS+Tapes|title=DILIFE - The Slow Decline of the VHS Tapes|work=wikispaces.com}}</ref> VHS also adds considerable noise to both the luminance and chroma channels. |

|||

=== High-capacity digital recording technologies === |

|||

{{see also|Digital video recorder}} |

|||

High-capacity digital recording systems are also gaining in popularity with home users. These types of systems come in several form factors: |

|||

* [[Hard disk]]–based [[set-top box]]es |

|||

* Hard disk/[[optical disc]] combination set-top boxes |

|||

* [[Personal computer]]–based [[Home theater PC|media center]] |

|||

* [[Portable media player]]s with TV-out capability |

|||

Hard disk-based systems include [[TiVo]] as well as other [[Digital video recorder|digital video recorder (DVR)]] offerings. These types of systems provide users with a no-maintenance solution for capturing video content. Customers of subscriber-based TV generally receive electronic program guides, enabling one-touch setup of a recording schedule. Hard disk–based systems allow for many hours of recording without user-maintenance. For example, a 120 [[gigabyte|GB]] system recording at an extended recording rate (XP) of 10 [[megabit per second|Mbit/s]] [[MPEG-2]] can record over 25 hours of video content. |

|||

== Legacy == |

|||