S'gaw people: Difference between revisions

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 31: | Line 31: | ||

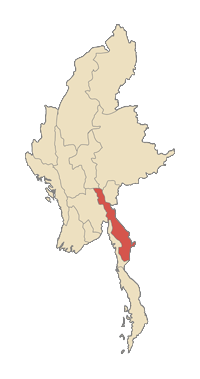

The S'gaw live primarily in eastern Burma ([[Kayin State|Karen State]], [[Mon state]], [[Kayah State|Karenni state]]). Many of them migrate to Thai-Burmese border and live there as a refugees for many decades due to conflict in Karen state. S'gaw people are the founder of the [[Karen National Union]] (KNU). The KNU have [[The Karen Conflict|waged a war]] against the central Burmese government since early 1949. The aim of the KNU at first was gaining an independence from the Burmese however that gaol has changed. Since 1976 the armed group has called for a federal system rather than an independent Karen state. |

The S'gaw live primarily in eastern Burma ([[Kayin State|Karen State]], [[Mon state]], [[Kayah State|Karenni state]]). Many of them migrate to Thai-Burmese border and live there as a refugees for many decades due to conflict in Karen state. S'gaw people are the founder of the [[Karen National Union]] (KNU). The KNU have [[The Karen Conflict|waged a war]] against the central Burmese government since early 1949. The aim of the KNU at first was gaining an independence from the Burmese however that gaol has changed. Since 1976 the armed group has called for a federal system rather than an independent Karen state. |

||

==Origins== |

|||

Karen ([[S'gaw]] and [[Pwo Karen|Pwo]]) legend refer to a 'river of running sand' ({{Lang-ksw|ထံဆဲမဲးယွါ}}) which they believe '''Pu Taw Meh Pa''' led the Karen people across the river of the running sand. Many Karen think this refers to the [[Gobi Desert]], although they have lived in Burma for centuries. The legend made the Karen people believe that they're from [[Mongolia]]. |

|||

The first Karen migration to Southeast Asia was around 1128 B.C. from Mongolia. They have traveled south and settle in [[Tibet Autonomous Region|Tibet region]] for a few centuries and moved again to around [[Yunan province]] and then finally enter mainland [[Southeast Asia]] in 739 B.C. and have lived in Eastern Burma and western Thailand since then. |

|||

==Political history== |

==Political history== |

||

| Line 43: | Line 49: | ||

*We shall decide our own political destiny. |

*We shall decide our own political destiny. |

||

===British period=== |

|||

==Origins== |

|||

Following British victories in the three [[Anglo-Burmese wars]], Myanmar was annexed as a province of British India in 1886. Baptist missionaries introduced Christianity to Myanmar beginning in 1830, and they were successful in converting many Karen.<ref>{{cite book |first=Mikael |last=Gravers |year=2007 |chapter=Conversion and Identity: Religion and the Formation of Karen Ethnic Identity in Burma |editor-first=Mikael |editor-last=Gravers |title=Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Burma |location=Copenhagen |publisher=Nordic Institute of Asian Studies |page=228 |isbn=978-87-91114-96-0 |quote=An estimated 15-20 per cent of Pwo and Sgaw Karen are Christian ... historical confrontation of Buddhism and Christianity which was a crucial part of the colonial conquest of Burma. This confrontation, which began with Christian conversion in 1830, created an internal opposition among the Karen.}}</ref> Christian Karens were favoured by the British colonial authorities and were given opportunities not available to the Burmese ethnic majority, including military recruitment and seats in the legislature.<ref>Josef Silverstein, Burma: Military Rule and the Politics of Stagnation (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1977), 16.</ref> Some Christian Karens began asserting an identity apart from their non-Christian counterparts, and many became leaders of Karen ethno-nationalist organisations, including the [[Karen National Union]].<ref name="keyes"/> |

|||

Karen ([[S'gaw]] and [[Pwo Karen|Pwo]]) legend refer to a 'river of running sand' ({{Lang-ksw|ထံဆဲမဲးယွါ}}) which they believe '''Pu Taw Meh Pa''' led the Karen people across the river of the running sand. Many Karen think this refers to the [[Gobi Desert]], although they have lived in Burma for centuries. The legend made the Karen people believe that they're from [[Mongolia]]. |

|||

In 1881 the Karen National Associations (KNA) was founded by western-educated [[Christian]] Karens to represent Karen interests with the British. Despite its Christian leadership, the KNA sought to unite all Karens of different regional and religious backgrounds into one organisation.<ref>Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung, The "Other" Karen in Myanmar: Ethnic Minorities and the Struggle without Arms (UK: Lexington Books, 2012), 29.</ref> They argued at the 1917 [[Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms|Montagu–Chelmsford hearings]] in [[India]] that Myanmar was not "yet in a fit state for [[self-government]]". Three years later, after submitting a criticism of the 1920 [[Reginald Craddock|Craddock Reforms]], they won 5 (and later 12) seats in the [[Legislative Council]] of 130 (expanded to 132) members. The majority [[Buddhist]] Karens were not organised until 1939 with the formation of a Buddhist KNA.<ref name="ms"/> |

|||

The first Karen migration to Southeast Asia was around 1128 B.C. from Mongolia. They have traveled south and settle in [[Tibet Autonomous Region|Tibet region]] for a few centuries and moved again to around [[Yunan province]] and then finally enter mainland [[Southeast Asia]] in 739 B.C. and have lived in Eastern Burma and western Thailand since then. |

|||

In 1938 the [[British Burma|British colonial administration]] recognised Karen New Year as a [[Public holidays in Myanmar|public holiday]].<ref name="ms">{{cite book|first=Martin|last=Smith|year=1991|title=Burma - Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity|publisher=Zed Books|location=London and New Jersey|pages=50–51,62–63,72–73,78–79,82–84,114–118,86,119}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://burmalibrary.org/docskaren/Karen%20Heritage%20Web/pdf/Karen%20Culture%202005.pdf|title=The First Karen New Year Message, 1938|publisher=''Karen Heritage'': Volume 1 - Issue 1|accessdate=2009-01-11}}</ref> |

|||

== |

===World War II=== |

||

During [[World War II]], when the [[Japan]]ese occupied the region, long-term tensions between the Karen and Burma turned into open fighting. As a consequence, many villages were destroyed and massacres committed by both the Japanese and the [[Burma Independence Army]] (BIA) troops who helped the Japanese invade the country. Among the victims were a pre-war Cabinet minister, Saw Pe Tha, and his family. A government report later claimed the 'excesses of the BIA' and 'the loyalty of the Karens towards the British' as the reasons for these attacks. The intervention by [[Colonel]] [[Suzuki Keiji]], the Japanese commander of the BIA, after meeting a Karen delegation led by Saw Tha Din, appears to have prevented further atrocities.<ref name="ms"/> |

|||

===Post-war=== |

|||

The Karen people aspired to have the regions where they formed the majority turned into a subdivision or "state" within Myanmar similar to what the [[Shan people|Shan]], [[Kachin people|Kachin]] and [[Chin people|Chin]] peoples had been given. A goodwill mission led by Saw Tha Din and Saw Ba U Gyi to [[London]] in August 1946 failed to receive any encouragement from the [[British government]] for any separatist demands. |

|||

In January 1947 a delegation of representatives of the Governor's Executive Council headed by [[Aung San]] was invited to [[London]] to negotiate for the [[Aung San]]–[[Clement Attlee|Attlee]] Treaty, none of the ethnic minority groups was included by the British government. The following month at the [[Panglong Conference]], when an agreement was signed between Aung San as head of the interim Burmese government and the Shan, Kachin and Chin leaders, the Karen were present only as observers; the [[Mon people|Mon]] and [[Rakhine people|Arakanese]] were also absent.<ref>Clive, Christie J., Anatomy of a Betrayal: The Karens of Burma. ''In: A Modern History of Southeast Asia. Decolonization, Nationalism and Separatism.'' (I.B. Tauris, 2000): 72.</ref> |

|||

The British promised to consider the case of the Karen after the [[Burma Campaign|war]]. While the situation of the Karen was discussed, nothing practical was done before the British left Myanmar. The 1947 Constitution, drawn without Karen participation due to their boycott of the [[Burmese general election, 1947|elections to the Constituent Assembly]], also failed to address the Karen question specifically and clearly, leaving it to be discussed only after independence. The [[Shan State|Shan]] and [[Kayah State|Karenni]] states were given the right to secession after 10 years, the Kachin their own state, and the Chin a special division. The Mon and Arakanese of Ministerial Myanmar were not given any consideration.<ref name="ms"/> |

|||

===Karen National Union=== |

|||

In early February 1947, the [[Karen National Union]] (KNU) was formed at a Karen Congress attended by 700 delegates from the Karen National Associations, both Baptist and Buddhist (KNA - founded 1881), the Karen [[Central Organisation]] (KCO) and its youth wing, the [[Karen Youth Organisation]] (KYO), at Vinton Memorial Hall in [[Yangon]]. The meeting called for a Karen state with a seaboard, an increased number of seats (25%) in the Constituent Assembly, a new ethnic census, and a continuance of Karen units in the armed forces. The deadline of March 3 passed without a reply from the British government, and [[Saw Ba U Gyi]], the president of the KNU, resigned from the Governor's Executive Council the next day.<ref name="ms"/> |

|||

[[File:IMG JudsonChurch.JPG|thumb|[[Adoniram Judson|Judson]] Memorial Baptist Church is the main place of worship for the Karen community in Mandalay, Myanmar]] |

|||

After the war ended, Myanmar was granted independence in January 1948, and the Karen, led by the KNU, attempted to co-exist peacefully with the Burman ethnic majority. Karen people held leading positions in both the government and the army. In the fall of 1948, the Burmese government, led by [[U Nu]], began raising and arming irregular political militias known as ''Sitwundan''. These [[militias]] were under the command of Major Gen. [[Ne Win]] and outside the control of the regular army. In January 1949, some of these militias went on a rampage through Karen communities. |

|||

The Karen National Union has maintained its structure and purpose from the 1950s onward. The KNU acts a governmental presence for the Karen people, offering basic social services for those affected by the insurgency, such as Karen refugees or internally displaced Karen. These services include building school systems, providing medical services, regulating trade and commerce, and providing security through the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), the KNU's army.<ref>Phan, Zoya and Damien Lewis. ''Undaunted: My Struggle for Freedom and Survival in Burma.'' New York: Free Press, 2010.</ref> |

|||

===Insurgency=== |

|||

In late January 1949, the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Smith Dun, a Karen, was removed from office and imprisoned. He was replaced by the Burmese nationalist Ne Win.<ref name="ms"/> Simultaneously a commission was looking into the Karen problem and this commission was about to report their findings to the Burmese government. The findings of the report were overshadowed by this political shift at the top of the Burmese government. The Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO), formed in July 1947, then rose up in an insurgency against the government.<ref name="ms"/> They were helped by the defections of the Karen Rifles and the Union Military Police (UMP) units which had been successfully deployed in suppressing the earlier [[Communist Party of Burma|Burmese Communist]] rebellions, and came close to capturing Yangon itself. The most notable was the Battle of Insein, nine miles from Yangon, where they held out in a 112-day siege till late May 1949.<ref name="ms"/> |

|||

Years later, the Karen had become the largest of 20 minority groups participating in an insurgency against the [[military dictatorship]] in Yangon. During the 1980s, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) fighting force numbered approximately 20,000. After an uprising of the people of Myanmar in 1988, known as the [[8888 Uprising]], the KNLA had accepted those demonstrators in their bases along the border. The dictatorship expanded the army and launched a series of major offensives against the KNLA. By 2006, the KNLA's strength had shrunk to less than 4,000, opposing what is now a 400,000-man Burmese army. However, the political arm of the KNLA - the KNU - continued efforts to resolve the conflict through political means. |

|||

The conflict continues {{As of|2006|lc=on}}, with a new KNU headquarters in [[Mu Aye Pu]], on the [[Burma|Burmese]]–[[Thailand|Thai]] border. In 2004, the [[BBC]], citing [[aid agencies]], estimates that up to 200,000 Karen have been driven from their homes during decades of war, with 160,000 more refugees from Myanmar, mostly Karen, living in [[refugee camp]]s on the Thai side of the border. The largest camp is the one in Mae La, Tak province, Thailand, where about 50,000 Karen refugees are hosted.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.arcmthailand.com/documents/documentcenter/Karen%20refugees%20in%20Thailand.pdf|author=Fratticcioli, Alessio|year=2011|title= Karen Refugees in Thailand (abridged)|publisher=Asian Research Center for Migration - Institute of Asian studies (IAS), Chulalongkorn University}}</ref> |

|||

Reports as recently as February, 2010, state that the Burmese army continues to burn Karen villages, displacing thousands of people.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.christiantelegraph.com/issue8685.html|title=Burma army burns more than 70 houses of Karen people|publisher=}}</ref> |

|||

Many Karen, including people such as former KNU secretary [[Padoh Mahn Sha Lah Phan]] and his daughter, [[Zoya Phan]], have accused the military government of Myanmar of [[ethnic cleansing]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/4987224.stm|title=BBC NEWS - Asia-Pacific - Burma Karen families 'on the run'|publisher=}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url= http://dynamic.csw.org.uk/country.asp?s=gi&urn=Burma|title= Countries of Focus: Burma |author= |work= |publisher= Christian Solidarity Network |accessdate=28 February 2011}}</ref><ref>[http://www.refugeesinternational.org/content/article/detail/1142/?PHPSESSID=3fc64258eda9d44c2 Refugeesinternational.org] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070311043821/http://www.refugeesinternational.org/content/article/detail/1142/?PHPSESSID=3fc64258eda9d44c2 |date=March 11, 2007 }}</ref><ref>[http://wwwa.house.gov/international_relations/108/mus100103.htm U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs]</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/credo-zoya-phan-1680127.html | location=London | work=The Independent | first=Adam | last=Jacques | title=Credo: Zoya Phan | date=2009-05-10}}</ref> The [[U.S. State Department]] has also cited the Burmese government for suppression of [[religious freedom]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2005/51506.htm|title=Burma|work=U.S. Department of State}}</ref> |

|||

A 2005 ''New York Times'' article on a report by Guy Horton into depredations by the Myanmar Army against the Karen and other groups in eastern Myanmar stated: |

|||

<blockquote>Using victims' statements, photographs, maps and film, and advised by legal counsel to the UN tribunal on the former Yugoslavia, he purports to have documented slave labour, systematic rape, the conscription of child soldiers, massacres and the deliberate destruction of villages, food sources and medical services.<ref>''[https://www.nytimes.com/2005/05/18/world/asia/18iht-burma.html A witness's plea to end Myanmar abuse]', by John Macgregor, New York Times, May 19, 2005.</ref></blockquote> |

|||

====Refugee crisis==== |

|||

Throughout the insurgency, hundreds of thousands of Karen fled to [[refugee]] camps while many others (numbers unknown) were [[internally displaced persons]] within the Karen state. The refugees were concentrated in camps along the [[Thailand]]-[[Myanmar]] border. According to refugee accounts, the camps suffered from overcrowding, disease, and periodic attacks by the [[Myanmar]] army.<ref>Phan, Zoya and Damien Lewis. Undaunted: My Struggle for Freedom and Survival in Burma. New York: Free Press, 2010.</ref> |

|||

==Life in the Refugee Camps== |

|||

Around 400,000 Karen people are without housing, and 128,000 are living in camps on the Thailand-Burma border. According to BMC, "79% of refugees living in these camps are Karen ethnicity."<ref name="Cook, Tonya L. 2015">Cook, Tonya L., et al. "War trauma and torture experiences reported during public health screening of newly resettled Karen refugees: a qualitative study." BMC international health and human rights 15.1 (2015): 8. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.</ref> Their lives are restricted in the camps because they usually cannot go out, and the Thai police might arrest them if they do.<ref name="Cook, Tonya L. 2015"/> Employment for the Karen refugees is scarce and risky. Former refugee, Hla Wah, said, "No jobs..So if adults wanted to work, they had to leave quietly without getting caught by Thai police."<ref>"On her own." multco.us/global/news. Multnomah County. 21 Aug. 2015.Web. 30 Nov. 2015.</ref> Wah is one of the Karen refugees who lived in a camp where she went to school and helped her family because her parents sought to go out to work, but they earned little money. Wah suffered from malnutrition because her parents did not have money to buy food for her 9 siblings. |

|||

==Karen Diaspora== |

|||

Beginning in 2000, the Karen started resettling in Canada, but because they did not know English, and because they were refugees, many were bullied, especially in school. Many Karen have problems fitting in and adjusting to the new country. "90% of the Karen refugees reported no knowledge of English or French on arrival."<ref name="Marchbank, Jennifer 2014">Marchbank, Jennifer, et al. Karen Refugees After Five Years in Canada-Readying Communities for Refugee Resettlement. 2014. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.</ref> Moreover, the Karen have also resettled in the U.S. In 2011-2012, the population was growing fast in Nebraska. The Karen have also resettled in Southern California and Central New York. |

|||

Mu Aye is a young Karen woman who has resettled in San Diego, CA. Aye said, "After growing up in a place like I did, I wanted to become a nurse. I wanted to help sick people..travel to refugee camps in Thailand and care for people who cannot afford medication." Additionally, Eh De Gray, who graduated from San Diego's Crawford High School, wants to go back to the camps and share his knowledge with the school children. Gray said, "I want to share my knowledge and experiences with them."<ref>Naing, Saw Y. "In Struggle and Success, California's Karen refugees Remember Their Roots." The Irrawaddy. Irrawaddy Publishing Group., 11 Jun. 2015. Web. 5 Dec. 2015.</ref> |

|||

In 2014, Ler Htoo was sworn in after graduating from the St. Paul Police Academy in Minnesota, a state in which an estimated 8,500 Karen live, as the first Karen police officer in the United States.<ref>''[http://www.startribune.com/st-paul-swears-in-nation-s-first-karen-police-officer/286310851/ St. Paul swears in nation's first Karen police officer]', by James Walsh, Star Tribune, December 19, 2014.</ref> |

|||

===Democratic Karen Buddhist Army=== |

|||

During 1994 and 1995, dissenters from the Buddhist minority in the KNLA formed a splinter group of the KNU called the [[Democratic Karen Buddhist Army]] (DKBA), and went over to the side of the [[State Peace and Development Council|military junta]]. As a note, the DKBA split themselves from the KNU due to the KNLA's weak central power. Additionally, the mostly Pwo-speaking Buddhist Karen of the DKBA felt a tension with the KNU, whose leadership consisted for the most part of Sgaw-speaking Christians.<ref>Ashley South, "Karen Nationalist Communities: the 'Problem' of Diversity," Contemporary Southeast Asia 29.1 (2007): 61.</ref><ref>Ashley South, "Burma's longest War. Anatomy of the Karen conflict." Transnational Institute and Burma Center Netherlands (PrimaveraQuint, Amsterdam 2009):2-4.</ref> The split is believed to have led to the fall of the KNU headquarters at [[Manerplaw]] in January 1995.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kwekalu.net/photojournal1/soldier/story6.htm|author=Ba Saw Khin|year=2005|orig-year=Originally published 1998|title= Fifty Years of Struggle: A Review of the Fight for the Karen People's Autonomy (abridged)|publisher=kwekalu.net|accessdate=2009-01-11}}</ref> |

|||

===Indian Karen population=== |

|||

There is a population of 2500 people in India, mostly restricted to Mayabunder Tehsil of North Andaman in [[Andaman and Nicobar Islands|Andaman and Nicobar union Territory of India]]. They are all baptist Christians. They retain their language to intercommunicate within community, but use Hindi to communicate with non-Karen neighbours.<ref>http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.517.7093&rep=rep1&type=pdf</ref> |

|||

== Language == |

|||

The [[Karen languages]], members of the [[Tibeto-Burman languages|Tibeto-Burman]] group of the [[Sino-Tibetan languages|Sino-Tibetan]] language family, consist of three mutually unintelligible branches: Sgaw, Pwo, and Pa'o.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://stedt.berkeley.edu/html/STfamily.html|title=The Sino-Tibetan Language Family|publisher=}}</ref><ref>Lewis(1984)</ref> [[Karenni]] (Red Karen) and [[Kayan (Burma)|Kayan]] belong to the Sgaw branch. |

|||

The Karen languages are almost unique among the Tibeto-Burman languages in having a [[subject–verb–object]] word order; other than Karen and [[Bai language|Bai]], Tibeto-Burman languages feature a [[subject–object–verb]] order. This anomaly is likely due to the influence of neighboring [[Mon–Khmer languages|Mon]] and [[Tai languages]].<ref>Matisoff 1991</ref> |

|||

== Religion == |

|||

[[File:Buddhist Karen in Yangon.JPG|thumb|Buddhist Karen pilgrims at Ngahtatgyi Pagoda in Yangon]] |

|||

The majority of Karens are [[Theravada Buddhism|Theravada Buddhists]] who also practice [[animism]], while approximately 35% are [[Christian]].<ref name="kbddf">{{cite journal|title=The Karen people: culture, faith and history |publisher=Karen Buddhist Dhamma Dutta Foundation|pages=6, 24–28}}</ref><ref name="PK">{{cite web|url=http://burmalibrary.org/docskaren/Karen%20Heritage%20Web/pdf/Faith.pdf|title=Faith at a Crossroads|last=Keenan|first=Paul|publisher=''Karen Heritage'': Volume 1 - Issue 1, Beliefs}}</ref> Lowland Pwo-speaking Karens tend to be more orthodox Buddhists, whereas highland Sgaw-speaking Karens tend to be heterodox Buddhists who profess strong animist beliefs. |

|||

===Animism=== |

|||

Karen [[animism]] is defined by a belief in ''klar'' (soul), thirty-seven spirits that embody every individual.<ref name="kbddf"/> Misfortune and sickness are believed to be caused by ''klar'' that wander away, and death occurs when all thirty-seven ''klar'' leave the body.<ref name="kbddf"/> |

|||

===Buddhism=== |

|||

Karen Buddhists are the most numerous of the Karens and account for around 65% of the total Karen population.<ref name="hayami">{{cite journal |last=Hayami |first=Yoko |year=2011 |title=Pagodas and Prophets: Contesting Sacred Space and Power among Buddhist Karen in Karen State |journal=The Journal of Asian Studies |publisher=Association for Asian Studies |volume=70 |issue=4 |pages=1083–1105 |doi=10.1017/S0021911811001574 |jstor=41349984}}</ref> The Buddhist influence came from the [[Mon people|Mon]] who were dominant in [[Lower Burma]] until the middle of the 18th century. Buddhist Karen are found mainly in Kayin and Mon States and in Yangon, [[Bago Region|Bago]] and [[Tanintharyi Region]]s. There are Buddhist monasteries in most Karen villages, and the monastery is the centre of community life. [[Punna|Merit-making]] activities, such as almsgiving, are central to Karen Buddhist life.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ibiblio.org/obl/docs/KirstenEA-Karen%20Buddhism.htm|title=Elements of Pwo Karen Buddhism|last=Andersen|first=Kirsten Ewers|year=1978|publisher=The Scandinavian Institute of Asian Studies|location=Copenhagen|accessdate=14 April 2012}}</ref> |

|||

Buddhism was brought to Pwo-speaking Karens in the late 1700s, and the Yedagon Monastery atop Mount Zwegabin became the foremost center of Karen language Buddhist literature.<ref name="hayami"/> Many millennial sects were founded throughout the 1800s, led by Karen Buddhist ''minlaung'' rebels.<ref>{{cite book|last=Thawnghmung|first=Ardeth Maung|title=The "Other" Karen in Myanmar|publisher=Lexington Books|year=2011|isbn=978-0-7391-6852-3}}</ref> Two sects, Telakhon (or Telaku) and Leke, were founded in the 1860s.<ref name="hayami"/> The Tekalu sect, founded in [[Kyaing]] and considered a [[Buddhist sect]], is a mixture of spirit worship, Karen customs and worship of the future Buddha [[Maitreya|Metteyya]].<ref name="hayami"/> The Leke sect was founded on the western banks of the [[Thanlwin River]], and is no longer associated with Buddhism (as followers do not venerate Buddhist monks).<ref name="hayami"/> Followers believe that the future Buddha will return to Earth if they maintain their moral practices (following the [[Dhamma]] and precepts), and they practice [[vegetarianism]], hold Saturday services and construct distinct pagodas.<ref name="hayami"/> Several Buddhist socioreligious movements, both orthodox and heterodox, have arisen in the past century.<ref name="hayami"/> ''Duwae'', a type of pagoda worship, with animistic origins, is also practiced.<ref name="hayami"/> |

|||

There are several prominent Karen Buddhist monks, including Thuzana (S'gaw) and Zagara, who was conferred the "Agga Maha Saddammajotika" title by the Burmese government in 2004.<ref name="hayami"/> The Karen of Thailand<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chiangmai1.com/chiang_mai/karen.shtml|title=The Karen Hilltribe in Chiang Mai|publisher=}}</ref> have their own religion. |

|||

===Christianity=== |

|||

[[Tha Byu]], the first convert to [[Christianity]] in 1828, was [[baptism|baptised]] by Rev. [[George Boardman (missionary)|George Boardman]], an associate of [[Adoniram Judson]], founder of the [[American Baptist Foreign Mission Society]]. Today there are Christians belonging to the Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations. Some of the largest Protestant denominations are [[Baptists]] and [[Seventh-day Adventists]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://karenadventistchurch.org//|title=Karen Seventh-day Adventist Church Website}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://asapministries.org/the-plight-of-the-karen/|title= Adventist Southeast Asia Project}}</ref> |

|||

Alongside 'orthodox' Christianity, some of those who identify themselves as Christian also have syncretised elements of animism with Christianity. The Karen of the Irrawaddy delta are mostly Christians, whereas Buddhists tend to be found mainly in Kayin state and surrounding regions. Over |

|||

35% of Karen identify themselves as Christian today and about 90% of Karen people in USA are Christians.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.karen.org.au/karen_people.htm|title= Karen people}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Karen Baptist Convention]] (KBC) was established in 1913 and the headquarters is located in [[Yangon]] with 20 member associations throughout Myanmar. The KBC operates the K.B.C. Charity Hospital in [[Insein Township|Insein]], Yangon. The KBC also operates the [[Karen Baptist Theological Seminary]] in Insein. The seminary runs a theology program as well as a secular degree program (Liberal Arts Programme) to fulfill young Karens' intellectual and vocational needs. The Pwo Karen Baptist Convention is located in [[Ahlone Township|Ahlone]], Yangon and also operates the Pwo Karen Theological Seminary.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.pkts.org|title=Pwo karen Theological Seminary|publisher=}}</ref> There are other schools for Karen people in Myanmar, such as [[Paku Divinity School]] in Taungoo, Kothabyu Bible School in Pathein, and Yangon Home Mission School. The Thailand Karen Baptist Convention is located in [[Chiang Mai]], [[Thailand]]. |

|||

The Seventh-day Adventists have built several schools in the Karen refugee camps in Thailand to Christianise the Karen people. Eden Valley Academy in [[Tak Province|Tak]] and Karen Adventist Academy in [[Mae Hong Son]] are the two largest Seventh-day Adventist Karen schools. |

|||

==Culture== |

|||

[[crop rotation|Rotational farming]] has been a part of their culture for at least several hundred years.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/opinion/832596/karen-fight-to-keep-farms-in-parks-conflict|title=Bangkok Post|author=Post Publishing PCL.|publisher=}}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

|||

[[File:Omens in the Sun.jpg|thumb|Manuscript of the mid-nineteenth century, possibly of Sgaw Karen origin.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/world/heavens.html|title=The Heavens - World Treasures: Beginnings - Exhibitions - Library of Congress|publisher=loc.gov}}</ref>]] |

|||

* [[Karen State]] |

|||

* [[Karen people]] |

* [[Karen people]] |

||

* [[Karen Baptist Convention]] |

|||

* [[Karen Baptist Theological Seminary]] |

|||

* [[Karen of the Andamans]] |

|||

* [[Paku Divinity School]] |

|||

* [[Rambo (2008 film)|''Rambo'']], 2008 film |

|||

== Footnotes == |

|||

{{reflist|2}} |

|||

== References == |

|||

=== Print === |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Marshall |

|||

| first = Harry Ignatius |

|||

| year = 1997 |

|||

| origyear= 1922 |

|||

| title = The Karen People of Burma. A Study in Anthropology and Ethnology. |

|||

| publisher = [[White Lotus Press]] |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Anderson |

|||

| first = Jon Lee |

|||

| year = 2004 |

|||

| origyear= 1992 |

|||

| title = Guerrillas: Journeys in the Insurgent World |

|||

| publisher = [[Penguin Books]] |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Delang |

|||

| first = Claudio O. (Ed.) |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| year = 2003 |

|||

| title = Living at the Edge of Thai Society: The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand |

|||

| publisher = [[Routledge]] |

|||

| location = London |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-415-32331-4 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Evans |

|||

| first = W.H. |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

| year = 1932 |

|||

| title = The Identification of Indian Butterflies (2nd ed) |

|||

| publisher = [[Bombay Natural History Society]] |

|||

| location = Mumbai, India |

|||

| id = |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Falla |

|||

| first = Jonathan |

|||

| year = 1991 |

|||

| title = True Love and Bartholomew: Rebels of the Burmese Border |

|||

| publisher = [[Cambridge University Press]] |

|||

| location = Cambridge |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-521-39019-4 |

|||

}} |

|||

* Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, 'Chiang Mai's Hill Peoples' in: ''Ancient Chiang Mai'' Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Lewis |

|||

| first = Paul |

|||

| authorlink = |

|||

|author2=Elaine Lewis |

|||

| year = 1984 |

|||

| title = Peoples of the Golden Triangle |

|||

| publisher = Thames and Hudson Ltd |

|||

| location = London |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-500-97472-8 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

|last=Gravers |

|||

|first=Mikael |

|||

|title=Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Burma |

|||

|year=2007 |

|||

|publisher=Nordic Institute of Asian Studies |

|||

|location=Copenhagen |

|||

|isbn=978-87-91114-96-0 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite journal |

|||

| last = Matisoff |

|||

| first = James A. |

|||

| title = Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Present State and Future Prospects |

|||

| journal = Annual Review of Anthropology |

|||

| volume = 20 |

|||

| issue = 1 |

|||

| pages = 469–504 |

|||

| publisher = [[Annual Reviews]] Inc. |

|||

| year = 1991 |

|||

| doi = 10.1146/annurev.an.20.100191.002345 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Phan |

|||

| first = Zoya |

|||

| year = 2009 |

|||

| title = Little Daughter: a Memoir of Survival in Burma and the West |

|||

| publisher = [[Simon & Schuster]] |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Scott |

|||

| first = James C. |

|||

| year = 2009 |

|||

| title = The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia |

|||

| publisher = [[Yale University Press]] |

|||

| location = New Haven |

|||

| isbn = 978-0-300-15228-9 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

|last=Silverstein |

|||

|first=Josef |

|||

|title=Burma: Military Rule and the Politics of Stagnation |

|||

|year=1977 |

|||

|publisher=Cornell University press |

|||

|location=Ithaca, N.Y. |

|||

|isbn=0-8014-0911-X |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

| last = Smith |

|||

| first=Martin |

|||

| year = 1991 |

|||

| title = Burma - Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity |

|||

| publisher = Zed Books |

|||

| location = London and New Jersey |

|||

| isbn= 0-86232-868-3 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite book |

|||

|last=Thawngmung |

|||

|first=Ardeth Maung |

|||

|title=The 'Other' Karen in Myanmar: Ethnic Minorities and the Struggle Without Arms |

|||

|year=2012 |

|||

|publisher=Lexington Books|location=Lanham, UK |

|||

|isbn=978-0-7391-6852-3 |

|||

}} |

|||

=== Online === |

|||

* [http://www.karenproducts.com/index.php?mo=12&catid=66139, ''Karen Baptist Convention in Thailand''] |

|||

* [http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks08/0800051.txt San C. Po, ''Burma and the Karens''] (London 1928) |

|||

* [http://as-se.awr.org/mm/kxf/114?page=1 Adventist World Radio Karen] |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Burma:International Religious Freedom Report 2005 |

|||

| publisher = [[United States Department of State|U.S. State Department]] |

|||

| date = 2005-11-08 |

|||

| url = http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/2005/51506.htm |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-07-18 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Karen Weblinks |

|||

| url = http://www.stolaf.edu/people/leming/karenlinks.htm |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-07-18 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| last = Kendal |

|||

| first = Elizabeth |

|||

| title = Day of Prayer for Burma |

|||

| publisher = Christian Monitor |

|||

| date = 2006-03-09 |

|||

| url = http://www.christianmonitor.org/documents.php?type=Prayers&item_ID=233&action=display&lang=English&&PHPSESSID=db74c41 |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-07-18 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Description of the Sino-Tibetan Language Family |

|||

| url = http://stedt.berkeley.edu/html/STfamily.html |

|||

| accessdate = 2006-07-18 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

| title = Recent humanitarian efforts serving the Karen people |

|||

| url = http://burmamission.org |

|||

| accessdate = 2010-12-10 |

|||

}} |

|||

* {{cite web |

|||

|last=Karen Buddhist Dhamma Dhutta Foundation |

|||

|title=The Karen People: culture, faith and history |

|||

|url=http://www.karen.org.au/docs/Karen_people_booklet.pdf|accessdate= 2013-02-12}} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons category}} |

|||

* [http://www.dictatorwatch.org/articles/karenintro.html the Karen people of Burma] |

|||

* [http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks09/0900201p.pdf S'gaw Karen Grammar] |

|||

* [http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks08/0801341p.pdf S'gaw Karen Dictionary] |

|||

* [http://www.myanmarbible.com/bible/SgawKaren/html/index.html S'gaw Karen Bible] |

|||

* [http://www.karenvoice.net/ Karenvoice.net], shares the information of Karen interacting in the world from the past, struggling in Burma in the present and transiting in the world again in the future |

|||

* [http://www.karen.org/ Karens Around the World Unite]. |

|||

* [http://www.khrg.org/ Karen Human Rights Group], a new website documenting the human rights situation of Karen villagers in rural Burma |

|||

* [http://www.kawthoolei.org/ Kawthoolei] meaning "a land without evil", is the Karen name of the land of Karen people. An independent and impartial media outlet aimed to provide contemporary information of all kinds — social, cultural, educational and political |

|||

* [http://www.freeburmarangers.org/ Free Burma Rangers], website of [[Non-governmental organization|NGO]] that provides humanitarian assistance to [[Internally displaced person|Internally Displaced People]] |

|||

* [http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/irf/ Index of IRF reports on Burma 2001-5] |

|||

* [http://www.kwekalu.net ''Kwekalu''] literally "Karen Traditional Horn", the only online Karen language news outlet based in Mergui/Tavoy District of Kawthoolei |

|||

* [http://www.karenwomen.org/index.html Karen Women's Organization] |

|||

* [http://karenadventistchurch.org//Media/Audio%20Bible.html Karen Audio Bible] |

|||

==References== |

|||

{{reflist}} |

|||

{{Ethnic groups in Burma}} |

{{Ethnic groups in Burma}} |

||

{{Ethnic groups in Thailand}} |

{{Ethnic groups in Thailand}} |

||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Thailand]] |

|||

{{DEFAULTSORT:Karen People (Burma)}} |

|||

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Myanmar]] |

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Myanmar]] |

||

[[Category:Ethnic groups in |

[[Category:Ethnic groups in Thailand]] |

||

[[Category:Karen people]] |

[[Category:Karen people| ]] |

||

Revision as of 00:10, 11 May 2017

This article needs additional citations for verification. (June 2016) |

Karen flag | |

A S'gaw Karen woman in a traditional dress | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| 2-3 million | |

| around 1 million | |

| 64,759 | |

| 9,000 | |

| 5,000 | |

| All other countries | 2,000-6,000 |

| Languages | |

| Karen | |

| Religion | |

| Theravada Buddhism, Christianity, Animism | |

Template:Contains Burmese text

The S'gaw,(S'gaw Karen: စှီၤ or ပှၤကညီဖိ) also known as Skaw, S'gaw, S'gau, White Karen,[1] Paganyaw, Pgaz Cgauz and Pakayo,[2][better source needed] are an ethnic group of Burma and Thailand.[3] They speak the S'gaw Karen language.[4]

The S'gaw are a subgroup of the Karen (Kayin) people. They are also referred to by the exonym "White Karen", a term dating from colonial times and used in contrast to the Karenni (or "Red Karen") and the Pa'O (or "Black Karen"), even though the latter often rejected the term "Karen" to refer to themselves.[1] The S'gaw are the main subgroup of the Karen people therefore they are also called the Karen. Usually the term Karen referred to the S'gaw Karen. The S'gaw and Pwo Karen shared the same culture and ancestor but they speak totally two different languages. The Pwo are usually referred as Poe Karen by the foreigners. Other subgroup of the Karen languages have their own name and their own culture as long with their own religion and history. For example the Pa-O Karen will not be called the Karen instead they will be called the Pa-O however for the "S'gaw Karen", they will be called the Karen.

The S'gaw live primarily in eastern Burma (Karen State, Mon state, Karenni state). Many of them migrate to Thai-Burmese border and live there as a refugees for many decades due to conflict in Karen state. S'gaw people are the founder of the Karen National Union (KNU). The KNU have waged a war against the central Burmese government since early 1949. The aim of the KNU at first was gaining an independence from the Burmese however that gaol has changed. Since 1976 the armed group has called for a federal system rather than an independent Karen state.

Origins

Karen (S'gaw and Pwo) legend refer to a 'river of running sand' (S'gaw Karen: ထံဆဲမဲးယွါ) which they believe Pu Taw Meh Pa led the Karen people across the river of the running sand. Many Karen think this refers to the Gobi Desert, although they have lived in Burma for centuries. The legend made the Karen people believe that they're from Mongolia.

The first Karen migration to Southeast Asia was around 1128 B.C. from Mongolia. They have traveled south and settle in Tibet region for a few centuries and moved again to around Yunan province and then finally enter mainland Southeast Asia in 739 B.C. and have lived in Eastern Burma and western Thailand since then.

Political history

The first Karen president (KNU president) was Saw Ba U Gyi (S'gaw Karen: စီၤဘၣ်အူကၠံ; 1905 - 12 August 1950). Saw Ba U Gyi graduated with a bachelor's degrees from Rangoon University in 1925 and studied law in England, Passang the English bar in 1927. From 1937 to 1939, he served as the Minister of Revenue of British Burma, and from February to April 1947, as the Minister ft Transport and Communications of Burma. He was killed in an ambush by the Burmese Army on 12 August 1950.

Saw Ba U Gyi's four principles are still held as the guiding Principles of the Revolution of the Karen National Union:

- Surrender is out of the question.

- The recognition of the Karen State must be completed.

- We shall retain our arms.

- We shall decide our own political destiny.

British period

Following British victories in the three Anglo-Burmese wars, Myanmar was annexed as a province of British India in 1886. Baptist missionaries introduced Christianity to Myanmar beginning in 1830, and they were successful in converting many Karen.[5] Christian Karens were favoured by the British colonial authorities and were given opportunities not available to the Burmese ethnic majority, including military recruitment and seats in the legislature.[6] Some Christian Karens began asserting an identity apart from their non-Christian counterparts, and many became leaders of Karen ethno-nationalist organisations, including the Karen National Union.[7]

In 1881 the Karen National Associations (KNA) was founded by western-educated Christian Karens to represent Karen interests with the British. Despite its Christian leadership, the KNA sought to unite all Karens of different regional and religious backgrounds into one organisation.[8] They argued at the 1917 Montagu–Chelmsford hearings in India that Myanmar was not "yet in a fit state for self-government". Three years later, after submitting a criticism of the 1920 Craddock Reforms, they won 5 (and later 12) seats in the Legislative Council of 130 (expanded to 132) members. The majority Buddhist Karens were not organised until 1939 with the formation of a Buddhist KNA.[9] In 1938 the British colonial administration recognised Karen New Year as a public holiday.[9][10]

World War II

During World War II, when the Japanese occupied the region, long-term tensions between the Karen and Burma turned into open fighting. As a consequence, many villages were destroyed and massacres committed by both the Japanese and the Burma Independence Army (BIA) troops who helped the Japanese invade the country. Among the victims were a pre-war Cabinet minister, Saw Pe Tha, and his family. A government report later claimed the 'excesses of the BIA' and 'the loyalty of the Karens towards the British' as the reasons for these attacks. The intervention by Colonel Suzuki Keiji, the Japanese commander of the BIA, after meeting a Karen delegation led by Saw Tha Din, appears to have prevented further atrocities.[9]

Post-war

The Karen people aspired to have the regions where they formed the majority turned into a subdivision or "state" within Myanmar similar to what the Shan, Kachin and Chin peoples had been given. A goodwill mission led by Saw Tha Din and Saw Ba U Gyi to London in August 1946 failed to receive any encouragement from the British government for any separatist demands.

In January 1947 a delegation of representatives of the Governor's Executive Council headed by Aung San was invited to London to negotiate for the Aung San–Attlee Treaty, none of the ethnic minority groups was included by the British government. The following month at the Panglong Conference, when an agreement was signed between Aung San as head of the interim Burmese government and the Shan, Kachin and Chin leaders, the Karen were present only as observers; the Mon and Arakanese were also absent.[11]

The British promised to consider the case of the Karen after the war. While the situation of the Karen was discussed, nothing practical was done before the British left Myanmar. The 1947 Constitution, drawn without Karen participation due to their boycott of the elections to the Constituent Assembly, also failed to address the Karen question specifically and clearly, leaving it to be discussed only after independence. The Shan and Karenni states were given the right to secession after 10 years, the Kachin their own state, and the Chin a special division. The Mon and Arakanese of Ministerial Myanmar were not given any consideration.[9]

Karen National Union

In early February 1947, the Karen National Union (KNU) was formed at a Karen Congress attended by 700 delegates from the Karen National Associations, both Baptist and Buddhist (KNA - founded 1881), the Karen Central Organisation (KCO) and its youth wing, the Karen Youth Organisation (KYO), at Vinton Memorial Hall in Yangon. The meeting called for a Karen state with a seaboard, an increased number of seats (25%) in the Constituent Assembly, a new ethnic census, and a continuance of Karen units in the armed forces. The deadline of March 3 passed without a reply from the British government, and Saw Ba U Gyi, the president of the KNU, resigned from the Governor's Executive Council the next day.[9]

After the war ended, Myanmar was granted independence in January 1948, and the Karen, led by the KNU, attempted to co-exist peacefully with the Burman ethnic majority. Karen people held leading positions in both the government and the army. In the fall of 1948, the Burmese government, led by U Nu, began raising and arming irregular political militias known as Sitwundan. These militias were under the command of Major Gen. Ne Win and outside the control of the regular army. In January 1949, some of these militias went on a rampage through Karen communities.

The Karen National Union has maintained its structure and purpose from the 1950s onward. The KNU acts a governmental presence for the Karen people, offering basic social services for those affected by the insurgency, such as Karen refugees or internally displaced Karen. These services include building school systems, providing medical services, regulating trade and commerce, and providing security through the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA), the KNU's army.[12]

Insurgency

In late January 1949, the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Smith Dun, a Karen, was removed from office and imprisoned. He was replaced by the Burmese nationalist Ne Win.[9] Simultaneously a commission was looking into the Karen problem and this commission was about to report their findings to the Burmese government. The findings of the report were overshadowed by this political shift at the top of the Burmese government. The Karen National Defence Organisation (KNDO), formed in July 1947, then rose up in an insurgency against the government.[9] They were helped by the defections of the Karen Rifles and the Union Military Police (UMP) units which had been successfully deployed in suppressing the earlier Burmese Communist rebellions, and came close to capturing Yangon itself. The most notable was the Battle of Insein, nine miles from Yangon, where they held out in a 112-day siege till late May 1949.[9]

Years later, the Karen had become the largest of 20 minority groups participating in an insurgency against the military dictatorship in Yangon. During the 1980s, the Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) fighting force numbered approximately 20,000. After an uprising of the people of Myanmar in 1988, known as the 8888 Uprising, the KNLA had accepted those demonstrators in their bases along the border. The dictatorship expanded the army and launched a series of major offensives against the KNLA. By 2006, the KNLA's strength had shrunk to less than 4,000, opposing what is now a 400,000-man Burmese army. However, the political arm of the KNLA - the KNU - continued efforts to resolve the conflict through political means.

The conflict continues as of 2006[update], with a new KNU headquarters in Mu Aye Pu, on the Burmese–Thai border. In 2004, the BBC, citing aid agencies, estimates that up to 200,000 Karen have been driven from their homes during decades of war, with 160,000 more refugees from Myanmar, mostly Karen, living in refugee camps on the Thai side of the border. The largest camp is the one in Mae La, Tak province, Thailand, where about 50,000 Karen refugees are hosted.[13]

Reports as recently as February, 2010, state that the Burmese army continues to burn Karen villages, displacing thousands of people.[14] Many Karen, including people such as former KNU secretary Padoh Mahn Sha Lah Phan and his daughter, Zoya Phan, have accused the military government of Myanmar of ethnic cleansing.[15][16][17][18][19] The U.S. State Department has also cited the Burmese government for suppression of religious freedom.[20]

A 2005 New York Times article on a report by Guy Horton into depredations by the Myanmar Army against the Karen and other groups in eastern Myanmar stated:

Using victims' statements, photographs, maps and film, and advised by legal counsel to the UN tribunal on the former Yugoslavia, he purports to have documented slave labour, systematic rape, the conscription of child soldiers, massacres and the deliberate destruction of villages, food sources and medical services.[21]

Refugee crisis

Throughout the insurgency, hundreds of thousands of Karen fled to refugee camps while many others (numbers unknown) were internally displaced persons within the Karen state. The refugees were concentrated in camps along the Thailand-Myanmar border. According to refugee accounts, the camps suffered from overcrowding, disease, and periodic attacks by the Myanmar army.[22]

Life in the Refugee Camps

Around 400,000 Karen people are without housing, and 128,000 are living in camps on the Thailand-Burma border. According to BMC, "79% of refugees living in these camps are Karen ethnicity."[23] Their lives are restricted in the camps because they usually cannot go out, and the Thai police might arrest them if they do.[23] Employment for the Karen refugees is scarce and risky. Former refugee, Hla Wah, said, "No jobs..So if adults wanted to work, they had to leave quietly without getting caught by Thai police."[24] Wah is one of the Karen refugees who lived in a camp where she went to school and helped her family because her parents sought to go out to work, but they earned little money. Wah suffered from malnutrition because her parents did not have money to buy food for her 9 siblings.

Karen Diaspora

Beginning in 2000, the Karen started resettling in Canada, but because they did not know English, and because they were refugees, many were bullied, especially in school. Many Karen have problems fitting in and adjusting to the new country. "90% of the Karen refugees reported no knowledge of English or French on arrival."[25] Moreover, the Karen have also resettled in the U.S. In 2011-2012, the population was growing fast in Nebraska. The Karen have also resettled in Southern California and Central New York.

Mu Aye is a young Karen woman who has resettled in San Diego, CA. Aye said, "After growing up in a place like I did, I wanted to become a nurse. I wanted to help sick people..travel to refugee camps in Thailand and care for people who cannot afford medication." Additionally, Eh De Gray, who graduated from San Diego's Crawford High School, wants to go back to the camps and share his knowledge with the school children. Gray said, "I want to share my knowledge and experiences with them."[26]

In 2014, Ler Htoo was sworn in after graduating from the St. Paul Police Academy in Minnesota, a state in which an estimated 8,500 Karen live, as the first Karen police officer in the United States.[27]

Democratic Karen Buddhist Army

During 1994 and 1995, dissenters from the Buddhist minority in the KNLA formed a splinter group of the KNU called the Democratic Karen Buddhist Army (DKBA), and went over to the side of the military junta. As a note, the DKBA split themselves from the KNU due to the KNLA's weak central power. Additionally, the mostly Pwo-speaking Buddhist Karen of the DKBA felt a tension with the KNU, whose leadership consisted for the most part of Sgaw-speaking Christians.[28][29] The split is believed to have led to the fall of the KNU headquarters at Manerplaw in January 1995.[30]

Indian Karen population

There is a population of 2500 people in India, mostly restricted to Mayabunder Tehsil of North Andaman in Andaman and Nicobar union Territory of India. They are all baptist Christians. They retain their language to intercommunicate within community, but use Hindi to communicate with non-Karen neighbours.[31]

Language

The Karen languages, members of the Tibeto-Burman group of the Sino-Tibetan language family, consist of three mutually unintelligible branches: Sgaw, Pwo, and Pa'o.[32][33] Karenni (Red Karen) and Kayan belong to the Sgaw branch. The Karen languages are almost unique among the Tibeto-Burman languages in having a subject–verb–object word order; other than Karen and Bai, Tibeto-Burman languages feature a subject–object–verb order. This anomaly is likely due to the influence of neighboring Mon and Tai languages.[34]

Religion

The majority of Karens are Theravada Buddhists who also practice animism, while approximately 35% are Christian.[35][36] Lowland Pwo-speaking Karens tend to be more orthodox Buddhists, whereas highland Sgaw-speaking Karens tend to be heterodox Buddhists who profess strong animist beliefs.

Animism

Karen animism is defined by a belief in klar (soul), thirty-seven spirits that embody every individual.[35] Misfortune and sickness are believed to be caused by klar that wander away, and death occurs when all thirty-seven klar leave the body.[35]

Buddhism

Karen Buddhists are the most numerous of the Karens and account for around 65% of the total Karen population.[37] The Buddhist influence came from the Mon who were dominant in Lower Burma until the middle of the 18th century. Buddhist Karen are found mainly in Kayin and Mon States and in Yangon, Bago and Tanintharyi Regions. There are Buddhist monasteries in most Karen villages, and the monastery is the centre of community life. Merit-making activities, such as almsgiving, are central to Karen Buddhist life.[38]

Buddhism was brought to Pwo-speaking Karens in the late 1700s, and the Yedagon Monastery atop Mount Zwegabin became the foremost center of Karen language Buddhist literature.[37] Many millennial sects were founded throughout the 1800s, led by Karen Buddhist minlaung rebels.[39] Two sects, Telakhon (or Telaku) and Leke, were founded in the 1860s.[37] The Tekalu sect, founded in Kyaing and considered a Buddhist sect, is a mixture of spirit worship, Karen customs and worship of the future Buddha Metteyya.[37] The Leke sect was founded on the western banks of the Thanlwin River, and is no longer associated with Buddhism (as followers do not venerate Buddhist monks).[37] Followers believe that the future Buddha will return to Earth if they maintain their moral practices (following the Dhamma and precepts), and they practice vegetarianism, hold Saturday services and construct distinct pagodas.[37] Several Buddhist socioreligious movements, both orthodox and heterodox, have arisen in the past century.[37] Duwae, a type of pagoda worship, with animistic origins, is also practiced.[37]

There are several prominent Karen Buddhist monks, including Thuzana (S'gaw) and Zagara, who was conferred the "Agga Maha Saddammajotika" title by the Burmese government in 2004.[37] The Karen of Thailand[40] have their own religion.

Christianity

Tha Byu, the first convert to Christianity in 1828, was baptised by Rev. George Boardman, an associate of Adoniram Judson, founder of the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society. Today there are Christians belonging to the Catholic Church and various Protestant denominations. Some of the largest Protestant denominations are Baptists and Seventh-day Adventists.[41][42] Alongside 'orthodox' Christianity, some of those who identify themselves as Christian also have syncretised elements of animism with Christianity. The Karen of the Irrawaddy delta are mostly Christians, whereas Buddhists tend to be found mainly in Kayin state and surrounding regions. Over 35% of Karen identify themselves as Christian today and about 90% of Karen people in USA are Christians.[43]

The Karen Baptist Convention (KBC) was established in 1913 and the headquarters is located in Yangon with 20 member associations throughout Myanmar. The KBC operates the K.B.C. Charity Hospital in Insein, Yangon. The KBC also operates the Karen Baptist Theological Seminary in Insein. The seminary runs a theology program as well as a secular degree program (Liberal Arts Programme) to fulfill young Karens' intellectual and vocational needs. The Pwo Karen Baptist Convention is located in Ahlone, Yangon and also operates the Pwo Karen Theological Seminary.[44] There are other schools for Karen people in Myanmar, such as Paku Divinity School in Taungoo, Kothabyu Bible School in Pathein, and Yangon Home Mission School. The Thailand Karen Baptist Convention is located in Chiang Mai, Thailand.

The Seventh-day Adventists have built several schools in the Karen refugee camps in Thailand to Christianise the Karen people. Eden Valley Academy in Tak and Karen Adventist Academy in Mae Hong Son are the two largest Seventh-day Adventist Karen schools.

Culture

Rotational farming has been a part of their culture for at least several hundred years.[45]

See also

- Karen State

- Karen people

- Karen Baptist Convention

- Karen Baptist Theological Seminary

- Karen of the Andamans

- Paku Divinity School

- Rambo, 2008 film

Footnotes

- ^ a b Sir George Scott. Among the Hill Tribes of Burma – An Ethnological Thicket. National Geographic Magazine, 1922, p. 293

- ^ Land Use and Sustainability in the Highlands of Northern Thailand

- ^ Hilltribes in Thailand

- ^ Ethnologue - Karen, S’gaw

- ^ Gravers, Mikael (2007). "Conversion and Identity: Religion and the Formation of Karen Ethnic Identity in Burma". In Gravers, Mikael (ed.). Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Burma. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. p. 228. ISBN 978-87-91114-96-0.

An estimated 15-20 per cent of Pwo and Sgaw Karen are Christian ... historical confrontation of Buddhism and Christianity which was a crucial part of the colonial conquest of Burma. This confrontation, which began with Christian conversion in 1830, created an internal opposition among the Karen.

- ^ Josef Silverstein, Burma: Military Rule and the Politics of Stagnation (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1977), 16.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

keyeswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Ardeth Maung Thawnghmung, The "Other" Karen in Myanmar: Ethnic Minorities and the Struggle without Arms (UK: Lexington Books, 2012), 29.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Smith, Martin (1991). Burma - Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. pp. 50–51, 62–63, 72–73, 78–79, 82–84, 114–118, 86, 119.

- ^ "The First Karen New Year Message, 1938" (PDF). Karen Heritage: Volume 1 - Issue 1. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ Clive, Christie J., Anatomy of a Betrayal: The Karens of Burma. In: A Modern History of Southeast Asia. Decolonization, Nationalism and Separatism. (I.B. Tauris, 2000): 72.

- ^ Phan, Zoya and Damien Lewis. Undaunted: My Struggle for Freedom and Survival in Burma. New York: Free Press, 2010.

- ^ Fratticcioli, Alessio (2011). "Karen Refugees in Thailand (abridged)" (PDF). Asian Research Center for Migration - Institute of Asian studies (IAS), Chulalongkorn University.

- ^ "Burma army burns more than 70 houses of Karen people".

- ^ "BBC NEWS - Asia-Pacific - Burma Karen families 'on the run'".

- ^ "Countries of Focus: Burma". Christian Solidarity Network. Retrieved 28 February 2011.

- ^ Refugeesinternational.org Archived March 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ U.S. House Committee on Foreign Affairs

- ^ Jacques, Adam (2009-05-10). "Credo: Zoya Phan". The Independent. London.

- ^ "Burma". U.S. Department of State.

- ^ A witness's plea to end Myanmar abuse', by John Macgregor, New York Times, May 19, 2005.

- ^ Phan, Zoya and Damien Lewis. Undaunted: My Struggle for Freedom and Survival in Burma. New York: Free Press, 2010.

- ^ a b Cook, Tonya L., et al. "War trauma and torture experiences reported during public health screening of newly resettled Karen refugees: a qualitative study." BMC international health and human rights 15.1 (2015): 8. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

- ^ "On her own." multco.us/global/news. Multnomah County. 21 Aug. 2015.Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

- ^ Marchbank, Jennifer, et al. Karen Refugees After Five Years in Canada-Readying Communities for Refugee Resettlement. 2014. Web. 30 Nov. 2015.

- ^ Naing, Saw Y. "In Struggle and Success, California's Karen refugees Remember Their Roots." The Irrawaddy. Irrawaddy Publishing Group., 11 Jun. 2015. Web. 5 Dec. 2015.

- ^ St. Paul swears in nation's first Karen police officer', by James Walsh, Star Tribune, December 19, 2014.

- ^ Ashley South, "Karen Nationalist Communities: the 'Problem' of Diversity," Contemporary Southeast Asia 29.1 (2007): 61.

- ^ Ashley South, "Burma's longest War. Anatomy of the Karen conflict." Transnational Institute and Burma Center Netherlands (PrimaveraQuint, Amsterdam 2009):2-4.

- ^ Ba Saw Khin (2005) [Originally published 1998]. "Fifty Years of Struggle: A Review of the Fight for the Karen People's Autonomy (abridged)". kwekalu.net. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.517.7093&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- ^ "The Sino-Tibetan Language Family".

- ^ Lewis(1984)

- ^ Matisoff 1991

- ^ a b c "The Karen people: culture, faith and history". Karen Buddhist Dhamma Dutta Foundation: 6, 24–28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Keenan, Paul. "Faith at a Crossroads" (PDF). Karen Heritage: Volume 1 - Issue 1, Beliefs.

{{cite web}}: Italic or bold markup not allowed in:|publisher=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h i Hayami, Yoko (2011). "Pagodas and Prophets: Contesting Sacred Space and Power among Buddhist Karen in Karen State". The Journal of Asian Studies. 70 (4). Association for Asian Studies: 1083–1105. doi:10.1017/S0021911811001574. JSTOR 41349984.

- ^ Andersen, Kirsten Ewers (1978). "Elements of Pwo Karen Buddhism". Copenhagen: The Scandinavian Institute of Asian Studies. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Thawnghmung, Ardeth Maung (2011). The "Other" Karen in Myanmar. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-6852-3.

- ^ "The Karen Hilltribe in Chiang Mai".

- ^ "Karen Seventh-day Adventist Church Website".

- ^ "Adventist Southeast Asia Project".

- ^ "Karen people".

- ^ "Pwo karen Theological Seminary".

- ^ Post Publishing PCL. "Bangkok Post".

- ^ "The Heavens - World Treasures: Beginnings - Exhibitions - Library of Congress". loc.gov.

References

- Marshall, Harry Ignatius (1997) [1922]. The Karen People of Burma. A Study in Anthropology and Ethnology. White Lotus Press.

- Anderson, Jon Lee (2004) [1992]. Guerrillas: Journeys in the Insurgent World. Penguin Books.

- Delang, Claudio O. (Ed.) (2003). Living at the Edge of Thai Society: The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-32331-4.

- Evans, W.H. (1932). The Identification of Indian Butterflies (2nd ed). Mumbai, India: Bombay Natural History Society.

- Falla, Jonathan (1991). True Love and Bartholomew: Rebels of the Burmese Border. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-39019-4.

- Forbes, Andrew, and Henley, David, 'Chiang Mai's Hill Peoples' in: Ancient Chiang Mai Volume 3. Chiang Mai, Cognoscenti Books, 2012. ASIN: B006IN1RNW

- Lewis, Paul; Elaine Lewis (1984). Peoples of the Golden Triangle. London: Thames and Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-97472-8.

- Gravers, Mikael (2007). Exploring Ethnic Diversity in Burma. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies. ISBN 978-87-91114-96-0.

- Matisoff, James A. (1991). "Sino-Tibetan Linguistics: Present State and Future Prospects". Annual Review of Anthropology. 20 (1). Annual Reviews Inc.: 469–504. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.20.100191.002345.

- Phan, Zoya (2009). Little Daughter: a Memoir of Survival in Burma and the West. Simon & Schuster.

- Scott, James C. (2009). The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-15228-9.

- Silverstein, Josef (1977). Burma: Military Rule and the Politics of Stagnation. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University press. ISBN 0-8014-0911-X.

- Smith, Martin (1991). Burma - Insurgency and the Politics of Ethnicity. London and New Jersey: Zed Books. ISBN 0-86232-868-3.

- Thawngmung, Ardeth Maung (2012). The 'Other' Karen in Myanmar: Ethnic Minorities and the Struggle Without Arms. Lanham, UK: Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0-7391-6852-3.

Online

- Karen Baptist Convention in Thailand

- San C. Po, Burma and the Karens (London 1928)

- Adventist World Radio Karen

- "Burma:International Religious Freedom Report 2005". U.S. State Department. 2005-11-08. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- "Karen Weblinks". Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- Kendal, Elizabeth (2006-03-09). "Day of Prayer for Burma". Christian Monitor. Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- "Description of the Sino-Tibetan Language Family". Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- "Recent humanitarian efforts serving the Karen people". Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- Karen Buddhist Dhamma Dhutta Foundation. "The Karen People: culture, faith and history" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-02-12.

External links

- the Karen people of Burma

- S'gaw Karen Grammar

- S'gaw Karen Dictionary

- S'gaw Karen Bible

- Karenvoice.net, shares the information of Karen interacting in the world from the past, struggling in Burma in the present and transiting in the world again in the future

- Karens Around the World Unite.

- Karen Human Rights Group, a new website documenting the human rights situation of Karen villagers in rural Burma

- Kawthoolei meaning "a land without evil", is the Karen name of the land of Karen people. An independent and impartial media outlet aimed to provide contemporary information of all kinds — social, cultural, educational and political

- Free Burma Rangers, website of NGO that provides humanitarian assistance to Internally Displaced People

- Index of IRF reports on Burma 2001-5

- Kwekalu literally "Karen Traditional Horn", the only online Karen language news outlet based in Mergui/Tavoy District of Kawthoolei

- Karen Women's Organization

- Karen Audio Bible