Nagasaki: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [accepted revision] |

m m copyedit + Ver-2 of Whitespace elimination. Best Compromise to font sizes~~~~ |

DragonFury (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Core city in Kyushu, Japan}} |

|||

{{Japanese city| |

|||

{{About|the city in Japan|the prefecture with the same name where this city is located|Nagasaki Prefecture|other uses}} |

|||

Name = Nagasaki| |

|||

{{pp-pc1}} |

|||

JapaneseName = 長崎市| |

|||

{{pp-move-indef}} |

|||

Region = [[Kyushu]]| |

|||

{{pp-pc|small=yes}} |

|||

Prefecture = [[Nagasaki prefecture]]| |

|||

{{Use mdy dates|date=February 2021}} |

|||

Area = 338.72 | |

|||

{{Infobox settlement |

|||

Population = 447,419 | |

|||

<!-- See Template:Infobox settlement for additional fields and descriptions -->| name = Nagasaki |

|||

PopDate = 2004 | |

|||

| native_name = {{nobold|{{lang|ja|長崎市}}}} |

|||

Density = 1321 | |

|||

| official_name = Nagasaki City |

|||

Mayor = Itchō Itō | |

|||

| settlement_type = [[List of capitals in Japan|Prefecture capital]] and [[Core cities of Japan|core city]] |

|||

Latitude = 32°44' N | |

|||

| image_skyline = Nagasaki_Montage2.jpg |

|||

Longitude = 129°52' E | |

|||

| image_caption = From top to bottom, left to right: [[Basilica of the Twenty-Six Holy Martyrs of Japan (Nagasaki)|Ōura Cathedral]], Nakashima River, [[Glover Garden]], [[Nagasaki Kunchi]], [[Nagasaki Shinchi Chinatown]], [[Nagasaki Peace Park]] |

|||

Tree = Chinese Tallow Tree| |

|||

| image_flag = Flag of Nagasaki, Nagasaki.svg |

|||

Flower = [[Hydrangea]]| |

|||

| image_seal = Nagasaki Nagasaki chapter.svg |

|||

Bird = | |

|||

| nickname = <br/>City of Peace<br/>[[Naples]] of the [[Orient]] |

|||

SymbolImage= Nagasaki CitySymbol.png| |

|||

| image_map1 = Nagasaki in Nagasaki Prefecture Ja.svg |

|||

CityHallPostalCode = 850-8685| |

|||

| map_caption1 = Map of [[Nagasaki Prefecture]] with Nagasaki highlighted in dark pink |

|||

CityHallAddress=Nagasaki-shi, Sakura-machi 2-22| |

|||

| pushpin_map = #Kyushu#Japan#Asia#Earth |

|||

CityHallPhone=095-825-5151| |

|||

| pushpin_map_caption = |

|||

CityHallLink = [http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/ Nagasaki City] | |

|||

| coordinates = {{coord|32|44|41|N|129|52|25|E|region:JP-42|display=it}} |

|||

CityMap=Nagasaki Nagasaki inPrefecture.png| |

|||

| subdivision_type = Country |

|||

ExtraNotes=White Terratory is Nagasaki Prefecture,<br> Yellow is Nagasaki City proper| |

|||

| subdivision_name = {{JAP}} |

|||

| subdivision_type1 = [[List of regions of Japan|Region]] |

|||

| subdivision_name1 = [[Kyushu]] |

|||

| subdivision_type2 = [[Prefectures of Japan|Prefecture]] |

|||

| subdivision_name2 = [[Nagasaki Prefecture]] |

|||

<!-- established --------------->| leader_title = Mayor |

|||

| leader_name = [[Shiro Suzuki (politician)|Shirō Suzuki]] <small>(from April 26, 2023)</small> |

|||

| area_magnitude = <!-- use only to set a special wikilink --> |

|||

| area_total_km2 = 405.86 |

|||

| area_land_km2 = 240.71 |

|||

| area_water_km2 = 165.15 |

|||

| population_total = 392,281<ref name="population-202006">{{cite web | url=https://www.city.nagasaki.lg.jp/syokai/750000/751000/p007001.html | date=June 1, 2020 | access-date=June 20, 2020 | publisher=Nagasaki city office | title=今月のうごき(推計人口など最新の主要統計) | archive-date=August 13, 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200813045857/https://www.city.nagasaki.lg.jp/syokai/750000/751000/p007001.html | url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

| population_as_of = February 1, 2024 |

|||

| population_density_km2 = auto |

|||

| timezone1 = [[Japan Standard Time]] |

|||

| utc_offset1 = +9 |

|||

<!-- postal codes, area code --->| blank_name_sec1 = City Symbols |

|||

| blank1_name_sec1 = – Tree |

|||

| blank1_info_sec1 = [[Chinese tallow tree]] |

|||

| blank2_name_sec1 = – Flower |

|||

| blank2_info_sec1 = [[Hydrangea]] |

|||

| blank_name_sec2 = Phone number |

|||

| blank_info_sec2 = 095-825-5151 |

|||

| blank1_name_sec2 = Address |

|||

| blank1_info_sec2 = 2–22 Sakura-machi, Nagasaki-shi, Nagasaki-ken<br />850-8685 |

|||

<!-- website, footnotes -------->| website = {{URL|www.city.nagasaki.lg.jp}} |

|||

}} |

}} |

||

{{Infobox Chinese |

|||

| headercolor = #1e90ff |

|||

| pic = Nagasaki (Chinese characters).svg |

|||

| piccap = ''Nagasaki'' in ''[[kanji]]'' |

|||

| picupright = 0.45 |

|||

| kanji = 長崎 |

|||

| hiragana = ながさき |

|||

| romaji = Nagasaki |

|||

}} |

|||

{{nihongo|'''Nagasaki'''|長崎|Nagasaki||({{IPA|ja|naɡaꜜsaki|IPA|Ja-Nagasaki.ogg}}; {{lit}} "Long Cape")|lead=yes}}, officially known as '''Nagasaki City''' ({{lang-ja|長崎市|label=none}}, {{Transliteration|ja|Nagasaki-shi}}), is the capital and the largest [[Cities of Japan|city]] of the [[Nagasaki Prefecture]] on the island of [[Kyushu]] in [[Japan]]. |

|||

Founded by the Portuguese,<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Pacheco |first=Diego |date=1970 |title=The Founding of the Port of Nagasaki and its Cession to the Society of Jesus |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2383539 |journal=Monumenta Nipponica |volume=25 |issue=3/4 |pages=303–323 |doi=10.2307/2383539 |jstor=2383539 |issn=0027-0741}}</ref> the port of [[Portuguese_Nagasaki|Nagasaki]] became the sole [[Nanban trade|port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch]] during the 16th through 19th centuries. The [[Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region]] have been recognized and included in the [[World Heritage Sites in Japan|UNESCO World Heritage List]]. Part of Nagasaki was home to a major [[Imperial Japanese Navy]] base during the [[First Sino-Japanese War]] and [[Russo-Japanese War]]. Near the end of [[World War II]], the American [[atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]] made Nagasaki the second city in the world to experience a nuclear attack. The city was rebuilt.<ref>{{cite book|last=Hakim|first=Joy|author-link1=Joy Hakim|title=A History of US: Book 9: War, Peace, and All that Jazz|publisher=[[Oxford University Press]]|date=January 5, 1995|location=New York City|isbn=978-0195095142|title-link=A History of US}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Nagasaki-night_s.jpg|thumb|360px|left|Nagasaki at night, 2003]]<br><div> |

|||

<br><br><br><br><br> |

|||

<br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><div><div> |

|||

<!------- The size and placement of this picture taken together with that of the unwieldy city template AND 'breaks' properly FORMATS AND WRAPS all sizes of text so the text DISPLAYS NICE w/o awkward wrapping no matter what browser text size is selected AND ELIMINATES A LOT OF EXCESS (UGLY) WHITESPACE (My goal) [[User:Fabartus|<font color="blue">Fra]][[User talk:Fabartus|<font color="green">nkB]] 15:06, 10 August 2005 (UTC) --------> |

|||

{{As of|2024|02|01|df=US}}, Nagasaki has an estimated population of 392,281<ref name="population-202006" /> and a population density of 966 people per km<sup>2</sup>. The total area is {{convert|405.86|km2|abbr=on}}.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.gsi.go.jp/KOKUJYOHO/MENCHO/202001/42_nagasaki.pdf|title=令和2年全国都道府県市区町村別面積調 - 長崎県|publisher=Geospatial Information Authority of Japan|date=January 1, 2020|access-date=June 20, 2020|archive-date=June 13, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200613085949/https://www.gsi.go.jp/KOKUJYOHO/MENCHO/202001/42_nagasaki.pdf|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

<big>'''Nagasaki'''</big> {{Audio|ja-Nagasaki.ogg|listen}} (長崎市; -shi, literally "long [[peninsula]]") is the [[capital]] and the largest [[cities of Japan|city]] <big>'''of [[Nagasaki Prefecture]]'''</big> located on the south-western coast of [[Kyushu]], the southernmost of the four mainland islands of [[Japan]]. It was a center of European influence in medieval Japan from first contact through the era of isolationists efforts to block outside contact until the opening of Japan and the resultant modernization efforts of Japan during the Meiji Restoration. It became a major Japanese Navy Fleet Base during the [[First Sino-Japanese war]] and [[Russo-Japanese war]] and eventually was the second city on which an [[atomic bomb]] [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|was dropped]] by the [[United States|US]] during [[World War II]]. |

|||

==History== |

|||

Nagasaki lies at the head of a long bay which forms the best natural harbor on the southern Japanese home island of Kyushu. The main commercial and residential area of the city lies on a small plain near the end of the bay. Two rivers divided by a mountain spur form the two main valleys in which the city lies. The heavily built-up area of the city is confined by the terrain to less than 4 square miles. |

|||

{{For timeline}} |

|||

As of 2004 the population of the city is 447,419 and its size in square kilometres is 338.72 or about 130 sq.mi making it a fairly large city by Japanese standards in relation to its population level. |

|||

===Nagasaki as a Jesuit port of call=== |

|||

== History == |

|||

{{Main|Portuguese Nagasaki|Dejima}} |

|||

<!----- redundant w/table: Geographical location {{coor dm|32|44|N|129|52|E|}} [[User:Fabartus|<font color="blue">Fra]][[User talk:Fabartus|<font color="green">nkB]] 15:06, 10 August 2005 (UTC) ---> |

|||

The first contact with [[Portuguese explorers]] occurred in 1543. An early visitor was [[Fernão Mendes Pinto]], who came from [[Sagres (Vila do Bispo)|Sagres]] on a Portuguese ship which landed nearby in [[Tanegashima]]. |

|||

Soon after, [[Nanban trade|Portuguese ships started sailing to Japan as regular trade freighters]], thus increasing the contact and trade relations between Japan and the rest of the world, and particularly with [[Ming China|mainland China]], with whom Japan had previously severed its commercial and political ties, mainly due to a number of incidents involving [[wokou]] piracy in the [[South China Sea]], with the Portuguese now serving as intermediaries between the two [[East Asia]]n neighbors. |

|||

[[Image:NagasakiMeganebashi.jpg|thumb|400px|left|''Megane-bashi'' (''Spectacles Bridge'')]] |

|||

Despite the mutual advantages derived from these trading contacts, which would soon be acknowledged by all parties involved, the lack of a proper seaport in [[Kyūshū]] for the purpose of harboring foreign ships posed a major problem for both merchants and the Kyushu ''[[daimyō]]s'' (feudal lords) who expected to collect great advantages from the trade with the Portuguese. |

|||

===Medieval era=== |

|||

Founded before [[1500]], Nagasaki was originally a secluded harbor village. It enjoyed little historical significance until contact with European explorers in [[1542]], when a [[Portugal|Portuguese]] ship accidentally landed nearby, somewhere in [[Kagoshima prefecture]]. The zealous [[Jesuit]] [[missionary]] [[Francis Xavier]] arrived in another part of the territory in [[1549]], but left for [[China]] in [[1551]] and died soon afterwards. His followers who remained behind converted a number of ''[[daimyo]]'' (feudal lords). The most notable among them was [[Omura Sumitada]], who derived great profit from his conversion through an accompanying deal to receive a portion of the trade from Portuguese ships at a port they established in Nagasaki in [[1571]] with his assistance. |

|||

In the meantime, [[Kingdom of Navarre|Spanish]] [[Society of Jesus|Jesuit missionary]] [[Francis Xavier|St. Francis Xavier]] arrived in [[Kagoshima]], South Kyūshū, in 1549. After a somewhat fruitful two-year sojourn in Japan, he left for China in 1552 but died soon afterwards.<ref name="Diego Pacheco 1974 pp. 477-480">Diego Pacheco. "Xavier and Tanegashima." ''Monumenta Nipponica'', Vol. 29, No. 4 (Winter, 1974), pp. 477–480</ref> His followers who remained behind converted a number of ''daimyōs''. The most notable among them was [[Ōmura Sumitada]]. In 1569, Ōmura granted a permit for the establishment of a port with the purpose of harboring Portuguese ships in Nagasaki, which was set up in 1571, under the supervision of the [[Jesuit missionaries|Jesuit missionary Gaspar Vilela]] and [[Portuguese people|Portuguese]] Captain-Major [[Governor of Macau|Tristão Vaz de Veiga]], with Ōmura's personal assistance.<ref>Boxer, ''The Christian Century in Japan 1549–1650'', p. 100–101</ref> |

|||

The little harbor village quickly grew into a diverse port city, and Portuguese products imported through Nagasaki (such as [[tobacco]], [[bread]], [[tempura]], textiles, and a Portuguese sponge-cake called ''[[Kasutera|castellas]]'') were assimilated into popular Japanese culture. The Portuguese also brought with them many goods from [[China]]. |

|||

The little harbor village quickly grew into a diverse port city,<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/art-japan/edo-period/a/arrival-of-a-portuguese-ship | title=Arrival of a Portuguese ship | access-date=February 18, 2020 | archive-date=August 4, 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804195413/https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/art-asia/art-japan/edo-period/a/arrival-of-a-portuguese-ship | url-status=live }}</ref> and Portuguese products imported through Nagasaki (such as tobacco, bread, textiles and a Portuguese sponge-cake called ''[[Kasutera|castellas]]'') were assimilated into popular Japanese culture. [[Tempura]] derived from a popular Portuguese recipe originally known as ''[[peixinhos da horta]]'', and takes its name from the Portuguese word, 'tempero,' seasoning, and refers to the tempora quadragesima, forty days of Lent during which eating meat was forbidden, another example of the enduring effects of this cultural exchange. The Portuguese also brought with them many goods from other Asian countries such as China. The value of Portuguese exports from Nagasaki during the 16th century were estimated to ascend to over 1,000,000 ''cruzados'', reaching as many as 3,000,000 in 1637.<ref>C. R. Boxer, ''[https://books.google.com/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon The Great Ship from Amacon – Annals of Macau and the old Japan trade 1555–1640] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230414043924/https://books.google.com/books?id=pOoYAAAAIAAJ&q=The+Great+Ship+from+Amacon |date=April 14, 2023 }}'' p. 169.</ref> |

|||

In [[1587]], Nagasaki's prosperity was threatened when [[Toyotomi Hideyoshi]] came to power. Concerned with the large [[Christianity|Christian]] influence in southern Japan, he ordered the expulsion of all missionaries. Omura had given the Jesuits partial administrative control of Nagasaki, and the city now returned to Imperial control. Japanese and foreign Christians were persecuted, with Hideyoshi crucifying 26 Christians in Nagasaki in [[1596]] to deter any attempt to usurp his power. Portuguese traders were not ostracized, however, and so the city continued to thrive. |

|||

Due to the instability during the [[Sengoku period]], Sumitada and Jesuit leader [[Alexandro Valignano]] conceived a plan to pass administrative control over to the [[Society of Jesus]] rather than see the Catholic city taken over by a non-Catholic ''daimyō''. Thus, for a brief period after 1580, the city of Nagasaki was a Jesuit colony, under their administrative and military control. It became a refuge for Christians escaping maltreatment in other regions of Japan.<ref name=Diego>Diego Paccheco, Monumenta Nipponica, 1970</ref> In 1587, however, [[Toyotomi Hideyoshi]]'s campaign to unify the country arrived in Kyūshū. Concerned with the large Christian influence in Kyūshū, Hideyoshi ordered the expulsion of all [[missionaries]], and placed the city under his direct control. However, the expulsion order went largely unenforced, and the fact remained that most of Nagasaki's population remained openly practicing [[Catholicism|Catholic]].{{Citation needed|date=April 2022}} |

|||

When [[Tokugawa Ieyasu]] took power almost twenty years later, conditions did not improve much. Christianity was banned outright in [[1614]] and all missionaries were deported, as well as ''daimyo'' who would not renounce the religion. A brutal campaign of persecution followed, with thousands across [[Kyushu]] and other parts of Japan killed or tortured. The Christians did put up some initial resistance, with the Nagasaki [[Shimabara Rebellion|Shimabara]] enclave of destitute Christians and local peasants rising in rebellion in [[1637]]. Ultimately numbering 40,000, they captured [[Shimabara Castle]] and humiliated the local daimyo. The shogun dispatched 120,000 soldiers to quash the uprising, thus ending Japan's brief 'Christian Century.' Christians still remained, of course, but all went into hiding, still the victims of occasional inquisitions. |

|||

In 1596, the Spanish ship ''[[San Felipe incident (1596)|San Felipe]]'' was wrecked off the coast of [[Shikoku]], and Hideyoshi learned from its pilot<ref>so says the Jesuit account</ref> that the Spanish [[Franciscans]] were the vanguard of an [[Iberian Union|Iberian]] invasion of Japan. In response, Hideyoshi ordered the [[crucifixion]]s of twenty-six Catholics in Nagasaki on February 5 of the next year (i.e. the "[[Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan]]"). Portuguese traders were not ostracized, however, and so the city continued to thrive. |

|||

The [[Netherlands|Dutch]] had been quietly making inroads into Japan during this time, despite the shogunate's official policy of ending foreign influence within the country. The Dutch demonstrated that they were interested in trading alone, and demonstrated their commitment during the [[Shimabara Rebellion]] by firing on those Christians who defied the shogun. In [[1641]] they were granted [[Dejima]], an [[artificial island]] in Nagasaki Bay, as a base of operations. From this date until [[1855]], Japan's contact with the outside world was limited to Nagasaki. In [[1720]] the ban on Dutch books was lifted, causing hundreds of scholars to flood into Nagasaki to study European science and art. |

|||

In 1602, [[Augustinians|Augustinian]] missionaries also arrived in Japan, and when [[Tokugawa Ieyasu]] took power in 1603, Catholicism was still tolerated. Many Catholic ''[[daimyō]]s'' had been critical allies at the [[Battle of Sekigahara]], and the Tokugawa position was not strong enough to move against them. Once [[Osaka Castle]] had been taken and [[Toyotomi Hideyoshi]]'s offspring killed, though, the Tokugawa dominance was assured. In addition, the Dutch and English presence allowed trade without religious strings attached. Thus, in 1614, [[Catholicism]] was officially banned and all missionaries ordered to leave. Most Catholic daimyo [[apostacy|apostatized]], and forced their subjects to do so, although a few would not renounce the religion and left the country for [[Macau]], [[Luzon]] and [[Japantown]]s in Southeast Asia. A brutal campaign of persecution followed, with thousands of converts across Kyūshū and other parts of Japan killed, tortured, or forced to renounce their religion. Many Japanese and foreign Christians were executed by public [[crucifixion]] and [[Death by burning|burning at the stake]] in Nagasaki.<ref name="NSA">{{Cite book |url = http://newsaints.faithweb.com/martyrs/Japan02.htm |title =MARTYRS OF JAPAN († 1597-1637) (poz. 10) | access-date = March 22, 2011| author= | publisher = | language =en |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211123203927/http://newsaints.faithweb.com/martyrs/Japan02.htm |archive-date=November 23, 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | title=Martyrs List | url=http://www1.bbiq.jp/martyrs/ListEngl.html | publisher=Twenty-Six Martyrs Museum | access-date=2010-01-11 | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100214135648/http://www1.bbiq.jp/martyrs/ListEngl.html | archive-date=2010-02-14 }}</ref> They became known as the [[Martyrs of Japan]] and were later venerated by several [[Pope|Popes]].<ref name=JA3>{{cite web |url=http://newsaints.faithweb.com/martyrs/Japan03.htm |title=Martyrs of Japan (1603–39) |website= Hagiography Circle |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210609051808/http://newsaints.faithweb.com/martyrs/Japan03.htm |archive-date=June 9, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

During the [[Edo period]], the [[Tokugawa shogunate]] governed the city, appointing a [[hatamoto]], the Nagasaki ''bugyō'', as its chief administrator. |

|||

Catholicism's last gasp as an open religion and the last major military action in Japan until the [[Meiji Restoration]] was the [[Shimabara Rebellion]] of 1637. While there is no evidence that Europeans directly incited the rebellion, [[Shimabara Domain]] had been a Christian ''[[Han (administrative division)|han]]'' for several decades, and the rebels adopted many Portuguese motifs and Christian [[icon]]s. Consequently, in Tokugawa society the word "Shimabara" solidified the connection between Christianity and disloyalty, constantly used again and again in Tokugawa propaganda.{{Citation needed|date=May 2014}} The Shimabara Rebellion also convinced many policy-makers that foreign influences were more trouble than they were worth, leading to the [[sakoku|national isolation policy]]. The Portuguese were expelled from the archipelago altogether. They had previously been living on a specially constructed [[artificial island]] in Nagasaki harbour that served as a [[trading post]], called [[Dejima]]. The Dutch were then moved from their base at [[Hirado]] onto the artificial island. |

|||

===Modern era=== |

|||

{{Gallery |

|||

| mode = packed |

|||

| align = center |

|||

| height = 140 |

|||

| File:Macau Trade Routes.png|[[Portuguese Empire|Portuguese]] (green) and [[Spanish Empire|Spanish]] (yellow) trade routes to [[Portuguese Macao|Macao]] and Nagasaki |

|||

| File:Nanban-Screens-by-Kano-Naizen-c1600.png|[[Nanban trade|''Nanban'' trade]] by [[Kanō Naizen]], {{circa|1600}}. The screen shows foreigners arriving at a shore of Japan. |

|||

| File:Tojin-yashiki.jpg|The Chinese traders at Nagasaki were confined to a walled compound (Tōjin yashiki), {{circa|1688}} |

|||

}} |

|||

{{clear}} |

|||

=== Seclusion era === |

|||

[[image:nagasakibomb.jpg|thumbnail|250px|left|Mushroom cloud from the nuclear explosion over Nagasaki rising 60,000 feet into the air on the morning of August 9th, 1945]] |

|||

[[File:Deshima - KONB11-388A6-NA-P-052-GRAV.jpg|thumb|[[Dejima]] was an artificial island in Nagasaki Bay; its fan shape was easily recognizable. The trading post consisted mainly of warehouses and dwelling houses (1669 engraving).]] |

|||

[[File:Nagasakie. Dutch man with his slave.jpg|thumb|upright=0.65|A Dutchman with his slave at Dejima (18th-century painting by unknown artist, [[British Museum]] collection)]] |

|||

The [[Great Fire of Nagasaki]] destroyed much of the city in 1663, including the [[Lin Moniang|Mazu]] shrine at the [[Kofukuji (Nagasaki)|Kofuku Temple]] patronized by the Chinese sailors and merchants visiting the port.<ref name=properties>{{citation |contribution=Cultural Properties |contribution-url=http://kofukuji.com/english/properties.php |url=http://kofukuji.com/ |title=Official site |access-date=December 23, 2016 |location=Nagasaki |publisher=Thomeizan Kofukuji |archive-date=February 28, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210228051540/http://kofukuji.com/ |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

<br> |

|||

[[United States|US]] Commodore [[Matthew Perry (naval officer)|Matthew Perry]] landed in [[1853]]. The [[Tokugawa shogunate|Shogunate]] crumbled shortly afterward, and Japan opened its doors once again to foreign trade and diplomatic relations. Nagasaki became a [[free port]] in [[1859]] and modernization began in earnest in [[1868]]. With the [[Meiji Restoration]], Nagasaki quickly began to assume some economic dominance. Its main industry was ship-building. This very industry would eventually make it a target in [[World War II]], since many warships used by the Japanese Navy during the war were built in its factories and docks. |

|||

In 1720 the ban on Dutch books was lifted, causing hundreds of scholars to flood into Nagasaki to study European science and art. Consequently, Nagasaki became a major center of what was called ''[[rangaku]]'', or "Dutch learning". During the [[Edo period]], the [[Tokugawa shogunate]] governed the city, appointing a {{lang|ja-latn|[[hatamoto]]}}, the ''[[Nagasaki bugyō]]'', as its chief administrator. During this period, Nagasaki was designated a "shogunal city". The number of such cities rose from three to eleven under Tokugawa administration.<ref>[[Louis Cullen|Cullen, Louis M.]] (2003). [https://books.google.com/books?id=ycY_85OInSoC&q=bugyo&pg=PA59 ''A History of Japan, 1582–1941: Internal and External Worlds'', p. 159.] {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230406145220/https://books.google.com/books?id=ycY_85OInSoC&q=bugyo&pg=PA59 |date=April 6, 2023 }}</ref> |

|||

On [[9 August]] [[1945]], the primary target for the second [[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|atomic bomb attack]] was the nearby city of [[Kokura]], but the bomber pilot found it to be covered in cloud. The industrial areas outside Nagasaki were the secondary target and so, despite a far more powerful bomb, the devastation visited upon Nagasaki was less severe than that experienced by [[Hiroshima]]. The bomb exploded directly above the suburb of [[Urakami]], the site of [[Urakami Cathedral]], then the largest cathedral in East Asia. |

|||

Consensus among historians was once that Nagasaki was Japan's only window on the world during its time as a closed country in the Tokugawa era. However, nowadays it is generally accepted that this was not the case, since Japan interacted and traded with the [[Ryūkyū Kingdom]], [[Korea]] and Russia through [[Satsuma Domain|Satsuma]], [[Tsushima-Fuchū Domain|Tsushima]] and Matsumae respectively. Nevertheless, Nagasaki was depicted in contemporary art and literature as a cosmopolitan port brimming with exotic curiosities from the Western world.<ref name=CEJ>Cambridge Encyclopedia of Japan, [[Richard Bowring]] and Haruko Laurie</ref> |

|||

[[Image:NagasakiCatholicChurch.jpg|thumb|300px|right|Catholic Church in Nagasaki]] |

|||

In 1808, during the [[Napoleonic Wars]], the [[Royal Navy]] frigate [[HMS Phaeton (1782)|HMS ''Phaeton'']] [[Phaeton Incident|entered Nagasaki Harbor]] in search of Dutch trading ships. The local magistrate was unable to resist the crew’s demand for food, fuel, and water, later committing ''[[seppuku]]'' as a result. [[Edict to Repel Foreign Vessels|Laws were passed]] in the wake of this incident strengthening coastal defenses, threatening death to intruding foreigners, and prompting the training of English and Russian translators. |

|||

The city was rebuilt after the war, albeit dramatically changed. New temples were built, and new churches as well, since the Christian presence never died out and even increased dramatically after the war. Some of the rubble was left as a memorial, such as a one-legged [[torii]] gate and a stone arch near ground zero. New structures were also raised as memorials, such as the Atomic Bomb Museum. Nagasaki remains first and foremost a port city, supporting a rich shipping industry and setting a strong example of perseverance and peace. |

|||

The ''Tōjinyashiki'' (唐人屋敷) or Chinese Factory in Nagasaki was also an important conduit for Chinese goods and information for the Japanese market. Various Chinese merchants and artists sailed between the Chinese mainland and Nagasaki. Some actually combined the roles of merchant and artist such as 18th century [[Yi Hai]]. It is believed that as much as one-third of the population of Nagasaki at this time may have been Chinese.<ref>Screech, Timon. ''The Western Scientific Gaze and Popular Imagery in Later Edo Japan: The Lens Within the Heart''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996. p15.</ref> The Chinese traders at Nagasaki were confined to a walled compound ([[:ja:唐人屋敷|Tōjin yashiki]]) which was located in the same vicinity as Dejima island; and the activities of the Chinese, though less strictly controlled than the Dutch, were closely monitored by the [[Nagasaki bugyō]]. |

|||

== Nagasaki in Western music and song == |

|||

Nagasaki is the title and subject of a [[1928]] song with music by [[Harry Warren]] and lyrics by [[Mort Dixon]]. A popular success in its day, the music remains a popular base for jazz improvisations. The lyrics today are enjoyed for their ludicrous incongruity and their lack of political correctness. The song asserts: "Hot ginger and dynamite/There's nothing but that at night/Back in Nagasaki/Where the fellers chew tobaccy/And the women wicky wacky woo." |

|||

===Meiji Japan=== |

|||

Nagasaki is also the setting for [[Puccini]]'s opera [[Madama Butterfly]]. |

|||

With the [[Meiji Restoration]], Japan opened its doors once again to foreign trade and diplomatic relations. Nagasaki became a [[treaty port]] in 1859 and modernization began in earnest in 1868. Nagasaki was officially proclaimed a city on April 1, 1889. With Christianity legalized and the [[Kakure Kirishitan]] coming out of hiding, Nagasaki regained its earlier role as a center for Roman Catholicism in Japan.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Doak|first1=Kevin M.|editor1-last=Doak|editor1-first=Kevin M.|title=Xavier's Legacies: Catholicism in Modern Japanese Culture|date=2011|publisher=UBC Press|isbn=9780774820240|pages=12–13|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_Rr6CRwj9aAC&pg=PA13|access-date=February 27, 2018|chapter=Introduction: Catholicism, Modernity, and Japanese Culture|quote=In 1904, Catholics in Nagasaki, with their deep ties to the past, were three times more numerous than Catholics in the rest of Japan...}}</ref> |

|||

During the [[Meiji period]], Nagasaki became a center of [[heavy industry]]. Its main industry was [[ship-building]], with the dockyards under control of [[Mitsubishi Heavy Industries]] becoming one of the prime contractors for the [[Imperial Japanese Navy]], and with Nagasaki harbor used as an anchorage under the control of nearby [[Sasebo Naval District]]. During [[World War II]], at the time of the nuclear attack, Nagasaki was an important industrial city, containing both plants of the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, the Akunoura Engine Works, Mitsubishi Arms Plant, Mitsubishi Electric Shipyards, Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works, several other small factories, and most of the ports storage and trans-shipment facilities, which employed about 90% of the city's labor force, and accounted for 90% of the city's industry. These connections with the Japanese [[war effort]] made Nagasaki a major target for [[strategic bombing]] by the [[Allies of World War II|Allies]] during the war.<ref name="HYP">{{cite web |publisher=United States Strategic Bombing Survey |title=Chapter II The Effects of the Atomic Bombings |url=http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/USSBS/AtomicEffects/AtomicEffects-2.html |access-date=December 27, 2014 |archive-date=September 20, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180920201751/http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/USSBS/AtomicEffects/AtomicEffects-2.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=How Effective is Strategic Bombing?: Lessons Learned From World War II to Kosovo (World of War) |pages=86–87 |date=December 1, 2000 |publisher=NYU Press}}</ref> |

|||

==Sights== |

|||

{{Gallery |

|||

| mode = packed |

|||

| align = center |

|||

| height = 140 |

|||

| File:Nagasaki illustration2.jpeg|Plan of Nagasaki, Hizen province, 1778 |

|||

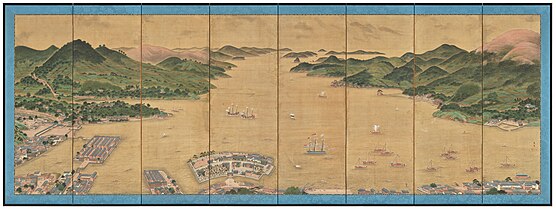

| File:View of Dejima in Nagasaki Bay Folding Screen by Kawahara Keiga c1836.jpg|View of [[Dejima]] in Nagasaki Bay by Kawahara Keigo c. 1836 |

|||

| File:View of Nagasaki Bay by Antoon Bauduin c1865.png|View of Nagasaki Bay, c. 1865 |

|||

| File:UCHIDA_KUICHI_Nagasaki.png|View of Nagasaki in 1870s |

|||

}} |

|||

===Atomic bombing of Nagasaki during World War II=== |

|||

*[[Oura Cathedral]] (大浦天主堂) |

|||

{{main|Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki#Nagasaki}} |

|||

*[[Urakami Cathedral]] (浦上天主堂) |

|||

[[File:Nagasakibomb.jpg|thumb|upright=0.85|The mushroom cloud from the atomic explosion over Nagasaki at 11:02 am, August 9, 1945]] |

|||

*[[Glover Garden]] (グラバー園) - [[Thomas Blake Glover]] |

|||

[[File:Sanno_torii_boxed_in_red.jpg|thumb|upright=0.9|An intact ''[[torii]]'' in foreground and a one-legged torii in background, Nagasaki, October 1945]] |

|||

*Nagasaki Shinchi Chinatown [http://www.nagasaki-chinatown.com/ in Japanese] |

|||

In the 12 months prior to the nuclear attack, Nagasaki had experienced five small-scale air attacks by an aggregate of 136 U.S. planes which dropped a total of 270 tons of [[high explosive]]s, 53 tons of [[incendiary device|incendiaries]], and 20 tons of [[fragmentation bombs]]. Of these, a raid of August 1, 1945, was the most effective, with a few of the bombs hitting the shipyards and dock areas in the southwest portion of the city, several hitting the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works, and six bombs landing at the Nagasaki Medical School and Hospital, with three direct hits on buildings there. While the damage from these few bombs was relatively small, it created considerable concern in Nagasaki and a number of people, principally school children, were evacuated to rural areas for safety, consequently reducing the population in the city at the time of the atomic attack.<ref name="HYP"/><ref>{{cite web|url=http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/mp07.asp|title=Avalon Project – The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki|access-date=December 27, 2014|archive-date=December 20, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141220192659/http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/mp07.asp|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last= Bradley |first= F.J. |title=No Strategic Targets Left |year=1999 |page=103 |publisher=Turner Publishing Company |isbn=978-1-5631-1483-0}}</ref> |

|||

==Foods== |

|||

On the day of the nuclear strike (August 9, 1945) the population in Nagasaki was estimated to be 263,000, which consisted of 240,000 Japanese residents, 10,000 Korean residents, 2,500 conscripted Korean workers, 9,000 Japanese soldiers, 600 conscripted Chinese workers, and 400 Allied [[Prisoner of war|POWs]].<ref name="HY">{{Cite web |title=Nagasaki atomic bombing, 1945 |url=http://www.johnstonsarchive.net/nuclear/radevents/1945JAP2.html |access-date=2024-02-04 |website=www.johnstonsarchive.net}}</ref> That day, the [[Boeing B-29 Superfortress]] ''[[Bockscar]]'', commanded by [[Major (United States)|Major]] [[Charles Sweeney]], departed from [[Tinian]]'s [[North Field (Tinian)|North Field]] just before dawn, this time carrying a [[plutonium bomb]], code named "[[Fat Man]]". The primary target for the bomb was [[Kokura#World War II|Kokura]], with the secondary target being Nagasaki, if the primary target was too cloudy to make a visual sighting. When the plane reached Kokura at 9:44 a.m. (10:44 am. Tinian Time), the city was obscured by clouds and smoke, as the [[Yahata, Fukuoka|nearby city of Yahata]] had been [[Firebombing|firebombed]] on the previous day – the steel plant in Yahata had also instructed their workforce to intentionally set fire to containers of [[coal tar]], to produce target-obscuring black smoke.<ref>{{cite web| url=http://mainichi.jp/english/english/features/news/20140726p2a00m0na014000c.html| title=Steel mill worker reveals blocking view of U.S. aircraft on day of Nagasaki atomic bombing| work=Mainichi Weekly| access-date=January 23, 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151122171430/http://mainichi.jp/english/english/features/news/20140726p2a00m0na014000c.html|archive-date=November 22, 2015}}</ref> Unable to make a bombing attack 'on visual' because of the clouds and smoke, and with limited fuel, the plane left the city at 10:30 a.m. for the secondary target. After 20 minutes, the plane arrived at 10:50 a.m. over Nagasaki, but the city was also concealed by clouds. Desperately short of fuel and after making a couple of bombing runs without obtaining any visual target, the crew was forced to use radar to drop the bomb. At the last minute, the opening of the clouds allowed them to make visual contact with a racetrack in Nagasaki, and they dropped the bomb on the city's [[Urakami|Urakami Valley]] midway between the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works in the south, and the Mitsubishi-Urakami Ordnance Works in the north.<ref>{{cite book |title=The History and Science of the Manhattan Project |author= Bruce Cameron Reed |date= October 16, 2013 |page=400 |publisher=[[Springer Nature]] |isbn=978-3-6424-0296-8}}</ref> The bomb exploded 53 seconds after its release, at 11:02 a.m. at an approximate altitude of 1,800 feet.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/timeline/factfiles/nonflash/a6652262.shtml|title=BBC - WW2 People's War – Timeline|access-date=February 18, 2020|archive-date=August 31, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200831135828/https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ww2peopleswar/timeline/factfiles/nonflash/a6652262.shtml|url-status=live}}</ref> |

|||

*Nagasaki is the home of a noodle dish called "[[champon]]." |

|||

*Sara Udon |

|||

Less than a second after the detonation, the north of the city was destroyed and more than 10% of the city's population were killed.<ref>{{cite book |title=Welcome To Planet Earth – 2050 – Population Zero |author= Robert Hull |date=October 11, 2011 |page=215 |publisher=[[AuthorHouse]] |isbn=978-1-4634-2604-0}}</ref>{{Better source needed|date=August 2024|reason=self-published non-[[WP:N|notable]] author}}{{Unreliable fringe source|date=August 2024}} Among the 35,000 deaths were 150 Japanese soldiers, 6,200 out of the 7,500 employees of the Mitsubishi Munitions plant, and 24,000 others (including 2,000 [[Korea_under_Japanese_rule#Deportation_of_forced_labor|Koreans]]). The industrial damage in Nagasaki was high, leaving 68{{nbnd}}80% of the non-dock industrial production destroyed. It was the second and, to date, the last use of a [[nuclear weapon]] in [[combat]], and also the second detonation of a plutonium bomb. The first combat use of a nuclear weapon was the "[[Little Boy]]" bomb, which was dropped on the Japanese city of [[Hiroshima]] on August 6, 1945. The [[Trinity (nuclear test)|first plutonium bomb was tested]] in [[central New Mexico]], United States, on July 16, 1945. The Fat Man bomb was more powerful than the one dropped over Hiroshima, but because of Nagasaki's more uneven terrain, there was less damage.<ref>{{cite book |title=Nuke-Rebuke: Writers & Artists Against Nuclear Energy & Weapons (The Contemporary anthology series) |pages=22–29 |date=May 1, 1984 |publisher=The Spirit That Moves Us Press}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Groves|1962|pp=343–346}}.</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Hoddeson|Henriksen|Meade|Westfall|1993|pp=396–397}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Kasutera]] |

|||

*[[Karasumi]] |

|||

===Contemporary era=== |

|||

The city was rebuilt after the war, albeit dramatically changed. The pace of reconstruction was slow. The first simple emergency dwellings were not provided until 1946. The focus of redevelopment was the replacement of war industries with foreign trade, shipbuilding and fishing. This was formally declared when the Nagasaki International Culture City Reconstruction Law was passed in May 1949.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://atomicbombmuseum.org/4_ruins.shtml|title=AtomicBombMuseum.org – After the Bomb|access-date=December 3, 2013|archive-date=February 19, 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170219200252/http://www.atomicbombmuseum.org/4_ruins.shtml|url-status=live}}</ref> New temples were built, as well as new churches, owing to an increase in the presence of Christianity.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.world-guides.com/asia/japan/kyushu/nagasaki/nagasaki_history.html|title=Nagasaki History Facts and Timeline|access-date=December 3, 2013|archive-date=September 28, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230928165803/http://www.world-guides.com/asia/japan/kyushu/nagasaki/nagasaki_history.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Some of the rubble was left as a memorial, such as a one-legged ''[[torii]]'' at [[Sannō Shrine]] and an arch near [[ground zero]]. New structures were also raised as memorials, such as the [[Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum|Atomic Bomb Museum]]. Nagasaki remains primarily a port city, supporting a rich [[shipbuilding]] industry. |

|||

On January 4, 2005, the towns of [[Iōjima, Nagasaki|Iōjima]], [[Koyagi, Nagasaki|Kōyagi]], [[Nomozaki, Nagasaki|Nomozaki]], [[Sanwa, Nagasaki|Sanwa]], [[Sotome, Nagasaki|Sotome]] and [[Takashima, Nagasaki (Nishisonogi)|Takashima]] (all from [[Nishisonogi District, Nagasaki|Nishisonogi District]]) were officially merged into Nagasaki along with the town of [[Kinkai, Nagasaki|Kinkai]] the following year. |

|||

{{Gallery |

|||

| mode = packed |

|||

| align = center |

|||

| height = 140 |

|||

| File:ModernDayNagasaki.jpg|Modern Nagasaki, [[Oura Cathedral]] on a slope, 2005 |

|||

| File:Nagasaki_City_view_from_Hamahira01s3.jpg|Night view of Nagasaki seen from Mount Konpira, 2012 |

|||

| File:Nagasaki City View from Glover Garden, Nagasaki 2014.jpg|View of Nagasaki seen from [[Glover Garden]], 2014 |

|||

}} |

|||

==Geography == |

|||

[[File:NagasakiBay-morning-722am-2016-1-4.ogv|thumb|Overview of Nagasaki in the early morning as the sun rises, 2016]] |

|||

Nagasaki and [[Nishisonogi Peninsula]]s are located within the city limits. The city is surrounded by the cities of [[Isahaya, Nagasaki|Isahaya]] and [[Saikai, Nagasaki|Saikai]], and the towns of [[Togitsu, Nagasaki|Togitsu]] and [[Nagayo, Nagasaki|Nagayo]] in [[Nishisonogi District, Nagasaki|Nishisonogi District]]. |

|||

Nagasaki lies at the head of a long bay that forms the best natural harbor on the island of Kyūshū. The main commercial and residential area of the city lies on a small plain near the end of the bay. Two rivers divided by a mountain spur form the two main valleys in which the city lies. The heavily built-up area of the city is confined by the terrain to less than {{convert|4|sqmi|km2}}. |

|||

=== Climate === |

|||

Nagasaki has the typical [[humid subtropical climate]] of Kyūshū and Honshū, characterized by mild winters and long, hot, and humid summers. Apart from [[Kanazawa, Ishikawa|Kanazawa]] and [[Shizuoka, Shizuoka|Shizuoka]] it is the wettest sizeable city in Japan. In the summer, the combination of persistent heat and high humidity results in unpleasant conditions, with [[wet-bulb temperature]]s sometimes reaching {{convert|26|C|F}}. In the winter, however, Nagasaki is drier and sunnier than [[Gotō, Nagasaki|Gotō]] to the west, and temperatures are slightly milder than further inland in Kyūshū. Since records began in 1878, the wettest month has been July 1982, with {{convert|1178|mm|in|0}} including {{convert|555|mm|in|1}} in a single day, whilst the driest month has been September 1967, with {{convert|1.8|mm|in|2}}. Precipitation occurs year-round, though winter is the driest season; rainfall peaks sharply in June and July. August is the warmest month of the year. On January 24, 2016, a snowfall of {{convert|17|cm|in|1}} was recorded.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20160125/k10010385121000.html |title=あすにかけ全国的に厳しい冷え込み続く |trans-title=Severe cold weather continues across the country into tomorrow |date=January 25, 2016 |website=nhk.or.jp |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160127195327/http://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20160125/k10010385121000.html |archive-date=January 27, 2016 |url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

{{Weather box |

|||

|location = Nagasaki (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1878−present) |

|||

|single line = Y |

|||

|metric first = Y |

|||

|Jan record high C = 21.3 |

|||

|Feb record high C = 22.6 |

|||

|Mar record high C = 24.4 |

|||

|Apr record high C = 29.0 |

|||

|May record high C = 31.4 |

|||

|Jun record high C = 36.4 |

|||

|Jul record high C = 37.7 |

|||

|Aug record high C = 37.7 |

|||

|Sep record high C = 36.1 |

|||

|Oct record high C = 33.7 |

|||

|Nov record high C = 27.4 |

|||

|Dec record high C = 23.8 |

|||

|Jan record low C = -5.6 |

|||

|Feb record low C = -4.8 |

|||

|Mar record low C = -3.6 |

|||

|Apr record low C = 0.2 |

|||

|May record low C = 5.3 |

|||

|Jun record low C = 8.9 |

|||

|Jul record low C = 15.0 |

|||

|Aug record low C = 16.4 |

|||

|Sep record low C = 11.1 |

|||

|Oct record low C = 4.9 |

|||

|Nov record low C = -0.2 |

|||

|Dec record low C = -3.9 |

|||

|precipitation colour = green |

|||

|Jan precipitation mm = 63.1 |

|||

|Feb precipitation mm = 84.0 |

|||

|Mar precipitation mm = 123.2 |

|||

|Apr precipitation mm = 153.0 |

|||

|May precipitation mm = 160.7 |

|||

|Jun precipitation mm = 335.9 |

|||

|Jul precipitation mm = 292.7 |

|||

|Aug precipitation mm = 217.9 |

|||

|Sep precipitation mm = 186.6 |

|||

|Oct precipitation mm = 102.1 |

|||

|Nov precipitation mm = 100.7 |

|||

|Dec precipitation mm = 74.8 |

|||

|year precipitation mm = 1894.7 |

|||

|Jan mean C = 7.2 |

|||

|Feb mean C = 8.1 |

|||

|Mar mean C = 11.2 |

|||

|Apr mean C = 15.6 |

|||

|May mean C = 19.7 |

|||

|Jun mean C = 23.0 |

|||

|Jul mean C = 26.9 |

|||

|Aug mean C = 28.1 |

|||

|Sep mean C = 24.9 |

|||

|Oct mean C = 20.0 |

|||

|Nov mean C = 14.5 |

|||

|Dec mean C = 9.4 |

|||

|year mean C = 17.4 |

|||

|Jan high C = 10.7 |

|||

|Feb high C = 12.0 |

|||

|Mar high C = 15.3 |

|||

|Apr high C = 19.9 |

|||

|May high C = 23.9 |

|||

|Jun high C = 26.5 |

|||

|Jul high C = 30.3 |

|||

|Aug high C = 31.9 |

|||

|Sep high C = 28.9 |

|||

|Oct high C = 24.1 |

|||

|Nov high C = 18.5 |

|||

|Dec high C = 13.1 |

|||

|year high C = 21.2 |

|||

|Jan low C = 4.0 |

|||

|Feb low C = 4.5 |

|||

|Mar low C = 7.5 |

|||

|Apr low C = 11.7 |

|||

|May low C = 16.1 |

|||

|Jun low C = 20.2 |

|||

|Jul low C = 24.5 |

|||

|Aug low C = 25.3 |

|||

|Sep low C = 21.9 |

|||

|Oct low C = 16.5 |

|||

|Nov low C = 11.0 |

|||

|Dec low C = 6.0 |

|||

|year low C = 14.1 |

|||

|Jan humidity = 66 |

|||

|Feb humidity = 65 |

|||

|Mar humidity = 65 |

|||

|Apr humidity = 67 |

|||

|May humidity = 72 |

|||

|Jun humidity = 80 |

|||

|Jul humidity = 80 |

|||

|Aug humidity = 76 |

|||

|Sep humidity = 73 |

|||

|Oct humidity = 67 |

|||

|Nov humidity = 68 |

|||

|Dec humidity = 67 |

|||

|year humidity = 71 |

|||

|Jan sun = 103.7 |

|||

|Feb sun = 122.3 |

|||

|Mar sun = 159.5 |

|||

|Apr sun = 178.1 |

|||

|May sun = 189.6 |

|||

|Jun sun = 125.0 |

|||

|Jul sun = 175.3 |

|||

|Aug sun = 207.0 |

|||

|Sep sun = 172.2 |

|||

|Oct sun = 178.9 |

|||

|Nov sun = 137.2 |

|||

|Dec sun = 114.3 |

|||

|year sun = 1863.1 |

|||

|Jan snow cm = 3 |

|||

|Feb snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Mar snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Apr snow cm = 0 |

|||

|May snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Jun snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Jul snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Aug snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Sep snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Oct snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Nov snow cm = 0 |

|||

|Dec snow cm = 0 |

|||

|year snow cm = 4 |

|||

|unit precipitation days = 0.5 mm |

|||

|Jan precipitation days = 10.4 |

|||

|Feb precipitation days = 10.2 |

|||

|Mar precipitation days = 11.4 |

|||

|Apr precipitation days = 10.3 |

|||

|May precipitation days = 10.1 |

|||

|Jun precipitation days = 14.3 |

|||

|Jul precipitation days = 11.9 |

|||

|Aug precipitation days = 10.7 |

|||

|Sep precipitation days = 9.8 |

|||

|Oct precipitation days = 6.7 |

|||

|Nov precipitation days = 9.5 |

|||

|Dec precipitation days = 10.2 |

|||

|year precipitation days = 125.6 |

|||

|source 1 = Japan Meteorological Agency<ref>{{cite web |

|||

| url = https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/index.php?prec_no=84&block_no=47817&year=&month=&day=&view= |

|||

| script-title = ja:気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値) |

|||

| publisher = [[Japan Meteorological Agency]] |

|||

| access-date = May 19, 2021 |

|||

| archive-date = May 21, 2021 |

|||

| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210521160814/https://www.data.jma.go.jp/obd/stats/etrn/index.php?prec_no=84&block_no=47817&year=&month=&day=&view= |

|||

| url-status = live |

|||

}}</ref> |

|||

}} |

|||

==Education== |

|||

===Universities=== |

|||

* [[Kwassui Women's University]] |

|||

* [[Nagasaki Institute of Applied Science]] |

|||

* [[Nagasaki Junshin Catholic University]] |

|||

* [[Nagasaki University]] |

|||

* [[Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nagasaki-gaigo.ac.jp/english/index.html |script-title=ja:長崎外国語大学 |trans-title=Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies |publisher=Nagasaki-gaigo.ac.jp |access-date=March 12, 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130330033437/http://www.nagasaki-gaigo.ac.jp/english/index.html |archive-date=March 30, 2013 }}</ref> |

|||

* [[Nagasaki Wesleyan University]] |

|||

===Junior colleges=== |

|||

* [[Nagasaki Junior College]] |

|||

* [[Nagasaki Junshin Junior College]] |

|||

*[[Nagasaki Gyokusei Junior College]], formerly {{Nihongo|Tamaki Women's Junior College|玉木女子短期大学}} (closed 2012) |

|||

*[[Nagasaki Women's Junior College]] |

|||

==Economy== |

|||

{{expand section|date=June 2023}} |

|||

* Shipbuilding |

|||

* [[Mitsubishi Heavy Industries|Mitsubishi]] |

|||

* Machinery and heavy industry |

|||

==Transportation== |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=June 2023}}[[File:Nagasaki Trolley M5199.jpg|thumb|A busy street in Nagasaki]] |

|||

The nearest airport is [[Nagasaki Airport]] in the nearby city of [[Ōmura, Nagasaki|Ōmura]]. The [[Kyushu Railway Company]] (JR Kyushu) provides rail transportation on the [[Nishi Kyushu Shinkansen]] and [[Nagasaki Main Line]], whose terminal is at [[Nagasaki Station (Nagasaki)|Nagasaki Station]]. In addition, the [[Nagasaki Electric Tramway]] operates five routes in the city. The [[Nagasaki Expressway]] serves vehicular traffic with interchanges at Nagasaki and Susukizuka. In addition, six [[National highways of Japan|national highways]] crisscross the city: [[Japan National Route 34|Route 34]], [[Japan National Route 202|202]], [[Japan National Route 206|206]], [[Japan National Route 251|251]], [[Japan National Route 324|324]], and [[Japan National Route 499|499]]. |

|||

==Demographics== |

|||

{{expand section|date=July 2017}} |

|||

[[File:Nagasaki population pyramid in 2020.svg|thumb|300x300px|Nagasaki prefecture population pyramid in 2020]] |

|||

On August 9, 1945, the population was estimated to be 263,000. As of March 1, 2017, the city had population of 505,723 and a population density of 1,000 persons per km<sup>2</sup>. |

|||

==Sports== |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=June 2023}} |

|||

Nagasaki is represented in the [[J. League]] of football with its local club, [[V-Varen Nagasaki]]. |

|||

==Main sites== |

|||

[[File:NagasakiHypocenter.jpg|thumb|Monument at the atomic bomb [[hypocenter]] in Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[File:Nagasaki peace memorial hall.jpg|thumb|Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims]] |

|||

[[File:Sofukuji Nagasaki Japan30n.jpg|thumb|[[Sōfuku-ji (Nagasaki)|Sōfuku-ji]] (National treasure of Japan)]] |

|||

*[[Basilica of the Twenty-Six Holy Martyrs of Japan (Nagasaki)|Basilica of the Twenty-Six Holy Martyrs of Japan]] |

|||

*[[Confucius Shrine, Nagasaki]] |

|||

*Dejima Museum of History |

|||

*Former residence of [[Shuhan Takashima]] |

|||

*Former site of Latin Seminario |

|||

*Former site of the British Consulate in Nagasaki |

|||

*Former site of [[Hong Kong and Shanghai Banking Corporation]] Nagasaki Branch |

|||

*[[Glover Garden]] |

|||

**Former Glover Residence |

|||

**Former Alt Residence |

|||

**Former Ringer Residence |

|||

**Former Walker Residence |

|||

*[[Fukusai-ji]] |

|||

*[[Hashima Island|Gunkanjima]] |

|||

*Higashi-Yamate Juniban Mansion |

|||

*Kazagashira Park |

|||

*[[Kōfuku-ji (Nagasaki)|Kofukuji]] |

|||

*[[Megane Bridge]] |

|||

*[[Mount Inasa]] |

|||

*[[Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum]]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/na-bomb/museum/index.html |script-title=ja:お知らせ 長崎市平和・原爆のホームページが変わりました。|publisher=.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp|access-date=June 1, 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020601132925/http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/na-bomb/museum/index.html|archive-date=June 1, 2002}}</ref> (located next to the Peace Park) |

|||

*[[Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture]]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nmhc.jp/index.html |script-title=ja:長崎歴史文化博物館 |publisher=Nmhc.jp |access-date=June 1, 2011 |archive-date=February 25, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210225190545/http://www.nmhc.jp/index.html |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

*[[Nagasaki National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims]] |

|||

*[[Nagasaki Peace Park]] |

|||

**Atomic Bomb Hypocenter (located near the Peace Park) |

|||

*Nagasaki [[Peace Pagoda]] |

|||

*Nagasaki Penguin Aquarium<ref name="nagasaki1">{{cite web|url=http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/penguin/ |script-title=ja:移転のお知らせ|publisher=.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp|access-date=June 1, 2011|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110607172756/http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/penguin/|archive-date=June 7, 2011}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Nagasaki Chinatown]] |

|||

*Nagasaki Science Museum<ref name="nagasaki1"/> |

|||

*[[Nagasaki Subtropical Botanical Garden]] |

|||

*[[Nyoko-do Hermitage]] |

|||

*[[Oranda-zaka]] |

|||

*[[Sannō Shrine]] – One-legged stone ''[[torii]]'', sometimes called an arch or gateway. |

|||

*[[Sakamoto International Cemetery]] |

|||

*[[Shōfuku-ji (Nagasaki)|Shōfuku-ji]] |

|||

*[[Siebold Memorial Museum]] |

|||

*[[Sōfuku-ji (Nagasaki)|Sōfuku-ji]] – Daiyūhōden and Daiippomon are national treasures of Japan. |

|||

*[[Suwa Shrine (Nagasaki)|Suwa Shrine]] |

|||

*[[Syusaku Endo Literature Museum]] |

|||

*Tateyama Park |

|||

*[[Twenty-Six Martyrs Museum and Monument]] |

|||

*Nagasaki Prefectural Art Museum |

|||

*[[Urakami Cathedral]] |

|||

*Miyo-Ken, a temple where the white snake is worshipped<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SY6DUnOOZSAC&q=nagasaki+serpent&pg=PA270 |title=The Encircled Serpent: A Study of Serpent Symbolism in All Countries and Ages – M. Oldfield Howey – Google Books |date=March 31, 2005 |access-date=March 12, 2013 |isbn=9780766192614 |last1=Oldfield Howey |first1=M. |publisher=Kessinger |archive-date=September 28, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230928165757/https://books.google.com/books?id=SY6DUnOOZSAC&q=nagasaki+serpent&pg=PA270 |url-status=live }}</ref> |

|||

===Cityscape=== |

|||

{{Wide image|Nagasaki vue du Mont Inasa.jpg|1000px|Nagasaki City seen from the Inasayama Observatory, facing southeast.}} |

|||

==Events== |

|||

[[File:Nagasaki Lantern Festival - 01.jpg|thumb|Nagasaki [[Lantern Festival]]]] |

|||

The Nagasaki [[Lantern Festival]]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.at-nagasaki.jp/lantern-festival |script-title=ja:長崎ランタンフェスティバル |publisher=Nagasaki City |access-date=17 May 2024}}</ref> is celebrated annually over the first 15 days of [[Chinese New Year]]<ref>{{cite web |url=https://en.japantravel.com/nagasaki/nagasaki-lantern-festival/33245 |title=Nagasaki Lantern Festival |publisher=Japan Travel |access-date=17 May 2024}}</ref> and is the largest of its kind in all of Japan.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.discover-nagasaki.com/en/sightseeing/51795 |title=Nagasaki Lantern Festival |publisher=Nagasaki Prefecture Tourism Association |access-date=17 May 2024}}</ref> |

|||

[[Nagasaki Kunchi|Kunchi]], the most famous festival in Nagasaki, is held from October 7–9.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Hesselink |first=Reinier H. |date=2004 |title=The Two Faces of Nagasaki: The World of the Suwa Festival Screen |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25066290 |journal=Monumenta Nipponica |volume=59 |issue=2 |pages=179–222 |jstor=25066290 |issn=0027-0741}}</ref> |

|||

The [[Prince Takamatsu Cup Nishinippon Round-Kyūshū Ekiden]], the world's longest [[relay race]], begins in Nagasaki each November. |

|||

==Cuisine== |

|||

[[File:Shikairo_Nagasaki_Japan05s.jpg|thumb|Original Shikairō [[Champon]]]] |

|||

*[[Tempura]] |

|||

*[[Castella]] |

|||

*[[Champon]] |

|||

*[[Sara udon]] |

|||

*Mogi Biwa |

|||

*[[Chinese desserts#candies|Chinese confections]] |

|||

*Urakami Soboro |

|||

*Shippoku Cuisine |

|||

*Toruko rice (''Turkish rice'') |

*Toruko rice (''Turkish rice'') |

||

*[[Karasumi]] |

|||

*Nagasaki [[Kakuni]] |

|||

==Notable people== |

|||

==Universities in Nagasaki city== |

|||

*[[Mr. Gannosuke]] |

|||

*Nagasaki University (national) |

|||

*[[Kazuo Ishiguro]] |

|||

*Nagasaki Institute of applied science |

|||

*[[Mitsurou Kubo]] |

|||

*Nagasaki University of Foreign Studies |

|||

*[[Ariana Miyamoto]] |

|||

*Kwassui Women's College |

|||

*[[Takashi Nagai]] |

|||

*Nagasaki Junshin University |

|||

*[[Atsushi Onita]] |

|||

*[[Neru Nagahama]] |

|||

*[[Maya Yoshida]] |

|||

*[[Tsutomu Yamaguchi]] |

|||

*[[Noboru Kaneko]] |

|||

*[[Kaori Sakagami]] |

|||

*{{ill|Keita Ogawa|ja|小川慶太}} |

|||

==Sister |

==Sister cities== |

||

{{See also|List of twin towns and sister cities in Japan}} |

|||

[http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/kokusai/simai/index_e.html 'Nagasaki's Sister Cities] |

|||

*[[Saint Paul, Minnesota]], [[United States]] - (1955) Oldest sister city in Japan |

|||

The city of Nagasaki maintains [[sister cities]] or friendship relations with other cities worldwide.<ref name="Nagasaki City Hall">{{cite web|url=http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/kokusai/english/exchange_e.html |title=Sister Cities of Nagasaki City |publisher=Nagasaki City Hall International Affairs Section|access-date=July 10, 2009 |url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090729002642/http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/kokusai/english/index-e.html|archive-date=July 29, 2009}}</ref> |

|||

*[[Santos]], [[Brazil]] (1972) |

|||

*[[Porto]], [[Portugal]] (1978) |

|||

<!-- Before adding to the list, please be sure to check the Nagasaki website. --> |

|||

*[[Middelburg]], [[Netherlands]] (1978) |

|||

*{{flagicon|Japan}} [[Hiroshima]], Japan |

|||

*[[Fuzhou]], [[People's Republic of China]] (1980) |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States}} [[St. Louis]], United States (1972) |

|||

*[[Vaux-sur-Aure]], [[France]] (2005) |

|||

*{{flagicon|United States}} [[Saint Paul, Minnesota|Saint Paul]], United States (1955)<ref name="Nagasaki City Hall"/> |

|||

*{{flagicon|Bulgaria}} [[Dupnitsa]], Bulgaria |

|||

*{{flagicon|Brazil}} [[Santos, São Paulo|Santos]], Brazil (1972)<ref name="Nagasaki City Hall"/> |

|||

*{{flagicon|China}} [[Fuzhou]], China, (1980)<ref name="Nagasaki City Hall"/> |

|||

*{{flagicon|The Netherlands}} [[Middelburg, Zeeland|Middelburg]], Netherlands (1978)<ref name="Nagasaki City Hall"/> |

|||

*{{flagicon|Portugal}} [[Porto]], Portugal (1978)<ref name="Nagasaki City Hall"/><ref name="Porto International">{{cite web|url=http://www.cm-porto.pt/document/449218/481584.pdf|title=International Relations of the City of Porto|publisher=Municipal Directorate of the Presidency Services International Relations Office|access-date=July 10, 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120113054303/http://www.cm-porto.pt/document/449218/481584.pdf|archive-date=January 13, 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

*{{flagicon|France}} [[Vaux-sur-Aure]], France (2005)<ref name="Nagasaki City Hall"/> |

|||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

{{Portal|Japan}} |

|||

*[[Gunkanjima]] |

|||

* [[Cultural treatments of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]] |

|||

*[[Foreign cemeteries in Japan]] |

|||

* [[Foreign cemeteries in Japan]] |

|||

*[[Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]] |

|||

* [[Hashima Island]] (Gunkanjima) |

|||

* [[Junior College of Commerce Nagasaki University]] (1951-2000) |

|||

==References== |

|||

== External links == |

|||

{{Reflist}} |

|||

* [http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/index_e.html Official website] in English |

|||

*[http://www1.city.nagasaki.nagasaki.jp/na-bomb/museum/museume01.html The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum] |

|||

==Bibliography== |

|||

{{See also|Timeline of Nagasaki#Bibliography|l1=Bibliography of the history of Nagasaki}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last=Groves |first=Leslie |author-link=Leslie Groves |title=Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project |location=New York |publisher=Da Capo Press |year=1983 | orig-year = 1962 |isbn=978-0-306-80189-1 |oclc=932666584 |ref=CITEREFGroves1962}} |

|||

* {{cite book |last1=Hoddeson |first1=Lillian|author-link=Lillian Hoddeson|first2=Paul W. |last2=Henriksen |first3=Roger A. |last3=Meade |first4=Catherine L. |last4=Westfall|author4-link= Catherine Westfall | title=Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos During the Oppenheimer Years, 1943–1945 | location=New York | publisher=Cambridge University Press | year=1993 | isbn=978-0-521-44132-2 | oclc=26764320 | url-access=registration | url=https://archive.org/details/criticalassembly0000unse }} |

|||

==External links== |

|||

{{Commons category|Nagasaki}} |

|||

{{Wikivoyage|Nagasaki}} |

|||

* {{Official website|http://www.city.nagasaki.lg.jp/}} {{in lang|ja}} |

|||

* {{Official website|http://www.city.nagasaki.lg.jp.e.jc.hp.transer.com/}} {{in lang|en}} |

|||

* [http://zidbits.com/2013/11/is-nagasaki-and-hiroshima-still-radioactive/ Is Nagasaki still radioactive?] – No. Includes explanation. |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20140811194213/http://oldnewmaps.com/2014/08/05/nagasaki-atomic-bomb-9-august-1945/ Nagasaki after atomic bombing] – interactive aerial map |

|||

* [http://www.nuclearfiles.org/menu/key-issues/nuclear-weapons/history/pre-cold-war/hiroshima-nagasaki/index.htm Nuclear Files.org] Comprehensive information on the history, and political and social implications of the US atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070117193919/http://www.ngs-kenkanren.com/mlang/english/ Nagasaki Prefectural Tourism Federation] |

|||

* [http://www.e-nagasaki.com/ Nagasaki Product Promotion Association] |

|||

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20080716034930/http://www.nia.or.jp/english/gaikoku/index.html Useful information for foreign residents], produced by Nagasaki International Association |

|||

* {{Osmrelation-inline|4011885}} |

|||

{{Nagasaki}} |

{{Nagasaki}} |

||

{{Metropolitan cities of Japan}} |

|||

[[Category:Cities in Nagasaki Prefecture]] |

|||

{{Most populous cities in Japan}} |

|||

[[Category:Cities in Kyushu]] |

|||

{{Authority control}} |

|||

[[Category:Cities in Japan]] |

|||

[[Category:Nagasaki| ]] |

|||

[[ar:ناغاساكي]] |

|||

[[ |

[[Category:Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki]] |

||

[[ |

[[Category:Cities in Nagasaki Prefecture]] |

||

[[Category:Destroyed populated places]] |

|||

[[es:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[Category:Populated coastal places in Japan]] |

|||

[[eo:Nagasako]] |

|||

[[Category:Populated places established in the 16th century]] |

|||

[[fr:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[Category:Port settlements in Japan]] |

|||

[[hi:नागासाकी]] |

|||

[[Category:World War II sites in Japan]] |

|||

[[id:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[it:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[he:נגסאקי]] |

|||

[[la:Nagasacium (civitas)]] |

|||

[[nl:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[ja:長崎市]] |

|||

[[no:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[nn:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[pl:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[pt:Nagasaki (cidade)]] |

|||

[[sk:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[fi:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[sv:Nagasaki]] |

|||

[[zh:长崎市]] |

|||

Latest revision as of 08:30, 21 August 2024

Nagasaki

長崎市 | |

|---|---|

| Nagasaki City | |

From top to bottom, left to right: Ōura Cathedral, Nakashima River, Glover Garden, Nagasaki Kunchi, Nagasaki Shinchi Chinatown, Nagasaki Peace Park | |

| Nickname(s): | |

Map of Nagasaki Prefecture with Nagasaki highlighted in dark pink | |

| Coordinates: 32°44′41″N 129°52′25″E / 32.74472°N 129.87361°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Kyushu |

| Prefecture | Nagasaki Prefecture |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Shirō Suzuki (from April 26, 2023) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 405.86 km2 (156.70 sq mi) |

| • Land | 240.71 km2 (92.94 sq mi) |

| • Water | 165.15 km2 (63.76 sq mi) |

| Population (February 1, 2024) | |

| • Total | 392,281[1] |

| Time zone | UTC+9 (Japan Standard Time) |

| – Tree | Chinese tallow tree |

| – Flower | Hydrangea |

| Phone number | 095-825-5151 |

| Address | 2–22 Sakura-machi, Nagasaki-shi, Nagasaki-ken 850-8685 |

| Website | www |

| Nagasaki | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Nagasaki in kanji | |||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 長崎 | ||||

| Hiragana | ながさき | ||||

| |||||

Nagasaki (Japanese: 長崎, Hepburn: Nagasaki) (IPA: [naɡaꜜsaki] ; lit. "Long Cape"), officially known as Nagasaki City (長崎市, Nagasaki-shi), is the capital and the largest city of the Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

Founded by the Portuguese,[2] the port of Nagasaki became the sole port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hidden Christian Sites in the Nagasaki Region have been recognized and included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Part of Nagasaki was home to a major Imperial Japanese Navy base during the First Sino-Japanese War and Russo-Japanese War. Near the end of World War II, the American atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki made Nagasaki the second city in the world to experience a nuclear attack. The city was rebuilt.[3]

As of February 1, 2024[update], Nagasaki has an estimated population of 392,281[1] and a population density of 966 people per km2. The total area is 405.86 km2 (156.70 sq mi).[4]

History

[edit]Nagasaki as a Jesuit port of call

[edit]The first contact with Portuguese explorers occurred in 1543. An early visitor was Fernão Mendes Pinto, who came from Sagres on a Portuguese ship which landed nearby in Tanegashima.

Soon after, Portuguese ships started sailing to Japan as regular trade freighters, thus increasing the contact and trade relations between Japan and the rest of the world, and particularly with mainland China, with whom Japan had previously severed its commercial and political ties, mainly due to a number of incidents involving wokou piracy in the South China Sea, with the Portuguese now serving as intermediaries between the two East Asian neighbors.

Despite the mutual advantages derived from these trading contacts, which would soon be acknowledged by all parties involved, the lack of a proper seaport in Kyūshū for the purpose of harboring foreign ships posed a major problem for both merchants and the Kyushu daimyōs (feudal lords) who expected to collect great advantages from the trade with the Portuguese.

In the meantime, Spanish Jesuit missionary St. Francis Xavier arrived in Kagoshima, South Kyūshū, in 1549. After a somewhat fruitful two-year sojourn in Japan, he left for China in 1552 but died soon afterwards.[5] His followers who remained behind converted a number of daimyōs. The most notable among them was Ōmura Sumitada. In 1569, Ōmura granted a permit for the establishment of a port with the purpose of harboring Portuguese ships in Nagasaki, which was set up in 1571, under the supervision of the Jesuit missionary Gaspar Vilela and Portuguese Captain-Major Tristão Vaz de Veiga, with Ōmura's personal assistance.[6]

The little harbor village quickly grew into a diverse port city,[7] and Portuguese products imported through Nagasaki (such as tobacco, bread, textiles and a Portuguese sponge-cake called castellas) were assimilated into popular Japanese culture. Tempura derived from a popular Portuguese recipe originally known as peixinhos da horta, and takes its name from the Portuguese word, 'tempero,' seasoning, and refers to the tempora quadragesima, forty days of Lent during which eating meat was forbidden, another example of the enduring effects of this cultural exchange. The Portuguese also brought with them many goods from other Asian countries such as China. The value of Portuguese exports from Nagasaki during the 16th century were estimated to ascend to over 1,000,000 cruzados, reaching as many as 3,000,000 in 1637.[8]

Due to the instability during the Sengoku period, Sumitada and Jesuit leader Alexandro Valignano conceived a plan to pass administrative control over to the Society of Jesus rather than see the Catholic city taken over by a non-Catholic daimyō. Thus, for a brief period after 1580, the city of Nagasaki was a Jesuit colony, under their administrative and military control. It became a refuge for Christians escaping maltreatment in other regions of Japan.[9] In 1587, however, Toyotomi Hideyoshi's campaign to unify the country arrived in Kyūshū. Concerned with the large Christian influence in Kyūshū, Hideyoshi ordered the expulsion of all missionaries, and placed the city under his direct control. However, the expulsion order went largely unenforced, and the fact remained that most of Nagasaki's population remained openly practicing Catholic.[citation needed]

In 1596, the Spanish ship San Felipe was wrecked off the coast of Shikoku, and Hideyoshi learned from its pilot[10] that the Spanish Franciscans were the vanguard of an Iberian invasion of Japan. In response, Hideyoshi ordered the crucifixions of twenty-six Catholics in Nagasaki on February 5 of the next year (i.e. the "Twenty-six Martyrs of Japan"). Portuguese traders were not ostracized, however, and so the city continued to thrive.

In 1602, Augustinian missionaries also arrived in Japan, and when Tokugawa Ieyasu took power in 1603, Catholicism was still tolerated. Many Catholic daimyōs had been critical allies at the Battle of Sekigahara, and the Tokugawa position was not strong enough to move against them. Once Osaka Castle had been taken and Toyotomi Hideyoshi's offspring killed, though, the Tokugawa dominance was assured. In addition, the Dutch and English presence allowed trade without religious strings attached. Thus, in 1614, Catholicism was officially banned and all missionaries ordered to leave. Most Catholic daimyo apostatized, and forced their subjects to do so, although a few would not renounce the religion and left the country for Macau, Luzon and Japantowns in Southeast Asia. A brutal campaign of persecution followed, with thousands of converts across Kyūshū and other parts of Japan killed, tortured, or forced to renounce their religion. Many Japanese and foreign Christians were executed by public crucifixion and burning at the stake in Nagasaki.[11][12] They became known as the Martyrs of Japan and were later venerated by several Popes.[13]

Catholicism's last gasp as an open religion and the last major military action in Japan until the Meiji Restoration was the Shimabara Rebellion of 1637. While there is no evidence that Europeans directly incited the rebellion, Shimabara Domain had been a Christian han for several decades, and the rebels adopted many Portuguese motifs and Christian icons. Consequently, in Tokugawa society the word "Shimabara" solidified the connection between Christianity and disloyalty, constantly used again and again in Tokugawa propaganda.[citation needed] The Shimabara Rebellion also convinced many policy-makers that foreign influences were more trouble than they were worth, leading to the national isolation policy. The Portuguese were expelled from the archipelago altogether. They had previously been living on a specially constructed artificial island in Nagasaki harbour that served as a trading post, called Dejima. The Dutch were then moved from their base at Hirado onto the artificial island.

-

The Chinese traders at Nagasaki were confined to a walled compound (Tōjin yashiki), c. 1688

Seclusion era

[edit]

The Great Fire of Nagasaki destroyed much of the city in 1663, including the Mazu shrine at the Kofuku Temple patronized by the Chinese sailors and merchants visiting the port.[14]

In 1720 the ban on Dutch books was lifted, causing hundreds of scholars to flood into Nagasaki to study European science and art. Consequently, Nagasaki became a major center of what was called rangaku, or "Dutch learning". During the Edo period, the Tokugawa shogunate governed the city, appointing a hatamoto, the Nagasaki bugyō, as its chief administrator. During this period, Nagasaki was designated a "shogunal city". The number of such cities rose from three to eleven under Tokugawa administration.[15]

Consensus among historians was once that Nagasaki was Japan's only window on the world during its time as a closed country in the Tokugawa era. However, nowadays it is generally accepted that this was not the case, since Japan interacted and traded with the Ryūkyū Kingdom, Korea and Russia through Satsuma, Tsushima and Matsumae respectively. Nevertheless, Nagasaki was depicted in contemporary art and literature as a cosmopolitan port brimming with exotic curiosities from the Western world.[16]

In 1808, during the Napoleonic Wars, the Royal Navy frigate HMS Phaeton entered Nagasaki Harbor in search of Dutch trading ships. The local magistrate was unable to resist the crew’s demand for food, fuel, and water, later committing seppuku as a result. Laws were passed in the wake of this incident strengthening coastal defenses, threatening death to intruding foreigners, and prompting the training of English and Russian translators.

The Tōjinyashiki (唐人屋敷) or Chinese Factory in Nagasaki was also an important conduit for Chinese goods and information for the Japanese market. Various Chinese merchants and artists sailed between the Chinese mainland and Nagasaki. Some actually combined the roles of merchant and artist such as 18th century Yi Hai. It is believed that as much as one-third of the population of Nagasaki at this time may have been Chinese.[17] The Chinese traders at Nagasaki were confined to a walled compound (Tōjin yashiki) which was located in the same vicinity as Dejima island; and the activities of the Chinese, though less strictly controlled than the Dutch, were closely monitored by the Nagasaki bugyō.

Meiji Japan