Arizona SB 1070: Difference between revisions

→Background and passage: a little more on governor actions |

GrantCon15 (talk | contribs) →Concerns over potential civil rights violations: Cited authority on the exception to the prohibition on using race. |

||

| Line 93: | Line 93: | ||

===Concerns over potential civil rights violations=== |

===Concerns over potential civil rights violations=== |

||

In its final form, HB 2162 specifically prohibits a law enforcement officer from using race as a basis for having reasonable suspicion to check a person's status |

In its final form, HB 2162 specifically prohibits a law enforcement officer from using race as a basis for having reasonable suspicion to check a person's status, except as authorized by the U.S. or Arizona constitution. It states, "A law enforcement official or agency of this state or a county, city, town or other political subdivision of this state may not consider race, color or national origin in implementing the requirements of this subsection except to the extent permitted by the United States or Arizona Constitution."<ref name="hb2162sect3"/> While the U.S. and Arizona constitutions ordinarily prohibit use of race as a basis for a stop or arrest, the U.S. and Arizona supreme courts have held that race may be considered in enforcing immigration law. In ''[[United States v. Brignoni-Ponce]]'', the Supreme Court found: “The likelihood that any given person of Mexican ancestry is an alien is high enough to make Mexican appearance a relevant factor.”<ref>[http://supreme.justia.com/us/422/873/case.html ''United States v. Brignoni-Ponce,''], 422 U.S. 873, 886-87 (1975).</ref> The Arizona Supreme Court agrees that “enforcement of immigration laws often involves a relevant consideration of ethnic factors.”<ref>[http://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=4830883310689136313&hl=en&as_sdt=2&as_vis=1&oi=scholarr ''State v. Graciano,''], 653 P.2d 683, 687 n.7 (Ariz. 1982).</ref> Both decisions say that race alone, however, is an insufficient basis to stop or arrest. Accordingly, the Arizona law seems to allow the use of race, but only as one factor. |

||

Critics of the measure have accused it of encouraging racial profiling, and as such it has been called the "Driving While Brown", "Living While Brown", or "Walking While Brown" law.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/opinions/articles/2010/04/22/20100422johnson23.html | title=How can state's immigration bill not be un-American | author=Johnson, Brad | newspaper=[[The Arizona Republic]] | date=April 23, 2010}}</ref><ref name="huffpo-jackson">{{cite news | url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rev-jesse-jackson/common-ground-african-ame_b_554072.html | title=Common Ground, African-Americans & Latinos | author=[[Jesse Jackson|Rev. Jackson, Jesse]] | publisher=[[The Huffington Post]] | date=April 27, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.denverpost.com/commented/ci_14994488?source=commented- | title=Taking a stand against Arizona law | author=Montoya, Butch | newspaper=[[Denver Post]] | date=May 1, 2010}}</ref> The Reverend [[Jesse Jackson]] said that opposition to the law would lead to common ground being formed between Latinos and African Americans<ref name="huffpo-jackson"/> (the latter's vernacular phrase "[[Driving While Black]]" was the origin of the new phrases against the Arizona law). |

Critics of the measure have accused it of encouraging racial profiling, and as such it has been called the "Driving While Brown", "Living While Brown", or "Walking While Brown" law.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.azcentral.com/arizonarepublic/opinions/articles/2010/04/22/20100422johnson23.html | title=How can state's immigration bill not be un-American | author=Johnson, Brad | newspaper=[[The Arizona Republic]] | date=April 23, 2010}}</ref><ref name="huffpo-jackson">{{cite news | url=http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rev-jesse-jackson/common-ground-african-ame_b_554072.html | title=Common Ground, African-Americans & Latinos | author=[[Jesse Jackson|Rev. Jackson, Jesse]] | publisher=[[The Huffington Post]] | date=April 27, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news | url=http://www.denverpost.com/commented/ci_14994488?source=commented- | title=Taking a stand against Arizona law | author=Montoya, Butch | newspaper=[[Denver Post]] | date=May 1, 2010}}</ref> The Reverend [[Jesse Jackson]] said that opposition to the law would lead to common ground being formed between Latinos and African Americans<ref name="huffpo-jackson"/> (the latter's vernacular phrase "[[Driving While Black]]" was the origin of the new phrases against the Arizona law). |

||

Revision as of 03:23, 22 June 2010

The Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act (introduced as Arizona Senate Bill 1070 and thus often referred to simply as Arizona SB 1070)[2] is a legislative act in the U.S. state of Arizona that is the broadest and strictest anti-illegal immigration measure in decades.[3] It has received national and international attention and has spurred considerable controversy.[4]

The act makes it a state misdemeanor crime for an alien to be in Arizona without carrying registration documents required by federal law, authorizes state and local law enforcement of federal immigration laws, and cracks down on those sheltering, hiring and transporting illegal aliens. The paragraph on intent in the legislation says it embodies an "attrition through enforcement" doctrine.[2][5]

Critics of the legislation say it encourages racial profiling, while supporters say the law simply enforces existing federal law.[6] The law was modified by Arizona House Bill 2162 within a week of its signing with the goal of addressing some of these concerns. There have been protests in opposition to the law in over 70 U.S. cities,[7] including boycotts and calls for boycotts of Arizona.[8] Polling has found the law to have majority support in Arizona and nationwide.[9][10][11][12] Passage of the measure has prompted other states to consider adopting similar legislation.[13]

The act was signed into law by Governor Jan Brewer on April 23, 2010.[3] It is scheduled to go into effect on July 28, 2010, ninety days after the end of the legislative session.[14][15] Legal challenges over its constitutionality and compliance with civil rights law have been filed.

Provisions

The act makes it a state misdemeanor crime for an alien to be in Arizona without carrying registration documents required by federal law,[16] and obligates police to make an attempt, when practicable during a "lawful stop, detention or arrest made by a law enforcement official",[17] to determine a person's immigration status if there is reasonable suspicion that the person is an illegal alien.[18] Police may arrest a person if there is probable cause that the person is an alien not in possession of required registration documents,[16] and an arrested person cannot be released without confirmation of legal immigration status by the federal government pursuant to § 1373(c) of Title 8 of the United States Code. A first offense carries a fine of up to $100, plus court costs, and up to 20 days in jail; subsequent offenses can result in up to 30 days in jail[19] (SB 1070 required a minimum fine of $500 for a first violation, and for a second violation a minimum $1,000 fine and a maximum jail sentence of 6 months).[20] A person is "presumed to not be an alien who is unlawfully present in the United States" if he or she presents any of the following four forms of identification: (a) a valid Arizona driver license; (b) a valid Arizona nonoperating identification license; (c) a valid tribal enrollment card or other tribal identification; or (d) any valid federal, state, or local government-issued identification, if the issuer requires proof of legal presence in the United States as a condition of issuance.[18]

The law also prohibits state, county, or local officials from limiting or restricting "the enforcement of federal immigration laws to less than the full extent permitted by federal law" and provides that Arizona citizens can sue such agencies or officials to compel such full enforcement.[18][21] A private citizen who prevails in such a lawsuit may be entitled to reimbursement of reasonable attorney fees and court costs.[18]

In addition, the law makes it a crime for anyone, regardless of citizenship or immigration status, to hire or to be hired from a vehicle which "blocks or impedes the normal movement of traffic." Vehicles used in such manner are subject to mandatory impounding. Moreover, "encourag[ing] or induc[ing]" illegal immigration, giving shelter to illegal immigrants, and transporting or attempting to transport an illegal alien, either knowingly or while "recklessly" disregarding the individual's immigration-status,[20] will be considered a class 1 criminal misdemeanor if fewer than ten illegal immigrants are involved, and a class 6 felony if ten or more are involved. The offender will be subject to a fine of at least $1,000 for each illegal alien so transported or sheltered.[20]

Arizona HB 2162

On April 30, the Arizona legislature passed, and Governor Brewer signed, House Bill 2162, which modified the law that had been signed a week earlier, with the amended text stating that "prosecutors would not investigate complaints based on race, color or national origin."[22] The new text also states that police may only investigate immigration status incident to a "lawful stop, detention, or arrest", lowers the original fine from a minimum of $500 to a maximum of $100, and changes incarceration limits from 6 months to 20 days for first-time offenders.[17]

Background and passage

Arizona is the first state with such a law as the Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act.[23] Prior law in Arizona, and the law in most other states, does not mandate that law enforcement personnel ask about the immigration status of those they encounter.[6] Many police departments discourage such inquiries to avoid deterring immigrants from reporting crimes and cooperating in other investigations.[6]

Arizona has an estimated 460,000 illegal immigrants,[6] a figure that has increased fivefold since 1990.[24] As the state with the most illegal crossings of the Mexico – United States border, its remote and punishing deserts are the entry point for thousands of Mexicans and Central Americans.[6] By the late 1990s, Tucson had become the location for the most number of arrests by the United States Border Patrol.[24]

Rates for violent crimes at the border and across Arizona decreased during the 2000s, although rates for property crimes increased.[25] Whether illegal immigrants committed a disproportionate number of crimes was uncertain, with different authorities and academics claiming that the rate for illegals was the same, greater, or less than that of the overall population.[25] Regardless, many in the public, some fueled by perception bias, held that it was greater.[25] There was also anxiety that the Mexican Drug War, which had caused thousands of deaths, would spill over into the U.S.[25] Moreover, by the late 2000s, Phoenix was seeing an average of one kidnapping per day, earning it the reputation as America's worst city in that regard.[24]

Arizona has a history of passing restrictions on illegal immigration, including legislation in 2007 that imposed heavy sanctions on employers hiring illegal immigrants.[26] Measures similar to SB 1070 had been passed by the legislature in 2006 and 2008, only to be vetoed by Democratic Governor Janet Napolitano.[3][27][28] She was subsequently elevated to Secretary of Homeland Security in the Obama administration and was replaced by Republican Secretary of State of Arizona Jan Brewer.[3][29] There is a similar history of referenda, such as the Arizona Proposition 200 (2004) that have sought to restrict illegal immigrants' use of social services. The 'attrition through enforcement' doctrine is one that think tanks such as the Center for Immigration Studies have been supporting for several years.[5]

Impetus for SB 1070 is attributed to shifting demographics leading to a larger Hispanic population, increased drugs- and human smuggling-related violence in Mexico and Arizona, and a struggling state economy.[30] State residents were also frustrated by the lack of federal progress on immigration, which they viewed as even more disappointing given that Napolitano was in the administration.[30]

The major sponsor of, and legislative force behind, the bill was State Senator Russell Pearce, who had long been one of Arizona's most vocal opponents of illegal immigration[31] and who had successfully pushed through several prior pieces of tough legislation against those he termed "invaders on the American sovereignty".[32][33] Much of the drafting of the bill was done by Kris Kobach,[33] a professor at the University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law[34] and a figure long associated with the Federation for American Immigration Reform who had written immigration-related bills in many other parts of the country.[35] Pearce and Kobach had worked together on past legislative efforts regarding immigration, and Pearce contacted Kobach when he was ready to pursue the idea of the state enforcing federal immigration laws.[33] The Arizona State Senate approved an early version of the bill in February 2010.[31] Saying, "Enough is enough," Pearce stated figuratively that this new bill would remove handcuffs from law enforcement and place them on violent offenders.[29][36]

The killing of 58-year-old Robert Krentz and his dog, shot on March 27, 2010, while doing fence work on his large ranch roughly 19 miles (31 km) from the Mexican border, gave a tangible public face to fears about immigration-related crime.[37][25] Arizona police were not able to name a murder suspect, but traced a set of footprints from the crime scene south towards the border, and the resulting speculation that the killer was an illegal alien increased support among the public for the measure.[3][37][25][28] For a while, there was talk of naming the law after Krentz.[28]

The bill, with a number of changes made to it, passed the Arizona House of Representatives on April 13 by a 35–21 party-line vote.[31] The revised measure then passed the State Senate on April 19 by a 17–11 vote that also closely followed party lines,[29] with all but one Republican voting for the bill, ten Democrats voting against the bill, and two Democrats not voting.[38]

Once a bill passes, the governor has five days to make a decision to sign, veto, or let it pass unsigned.[39][40] The question then became whether or not Governor Brewer would sign the bill into law, as she had remained silent on the measure while weighing the consequences.[3][39] Immigration had not been a prime focus of her political career up to this point, although as secretary of state she had supported Arizona Proposition 200 (2004).[41] Also as governor she made a push for Arizona Proposition 100 (2010), a one percent increase in the state sales tax to prevent cuts in education, health and human services, and public safety, despite opposition from within her own party.[39][41] These implications along with an upcoming tough Republican Party primary in the 2010 Arizona gubernatorial election from other conservative opponents supporting the bill were all considered major factors in her decision.[3][39][41] During the bill's development, her staff had gone over its language line by line with State Senator Pearce,[39][41] but she had also said she had concerns about several of its provisions.[42] The Mexican Senate urged the governor to veto the measure[36] and the Mexican Embassy to the U.S. raised concerns about potential racial profiling that may result.[29] Citizen messages to Brewer, however, were 3–1 in favor of the law.[29] A Rasmussen Reports poll taken between the House and Senate votes showed wide support for the bill among likely voters in the state, with 70 percent in favor and 23 percent opposed.[43] Of those same voters, 53 percent were at least somewhat concerned that actions taken due to the measures in the bill would violate the civil rights of some American citizens.[43] Brewer's staff said that she was considering the legal issues, the impact on the state's business, and the feelings of the citizens in coming to her decision.[39] They added that "she agonizes over these things,"[39] and the governor also prayed over the matter.[28] Brewer's political allies said her decision would cause her political trouble no matter which way she decided.[41] Most observers expected in the end that she would sign the bill, and on April 23 she did.[3]

During the time of the signing, there were over a thousand people at the Arizona State Capitol both in support of and opposition to the bill, and some minor civil unrest occurred.[21] Against concerns that the measure would promote racial profiling, Brewer stated that no such behavior would be tolerated: "We must enforce the law evenly, and without regard to skin color, accent or social status."[44] She vowed to ensure that police forces had proper training relative to the law and civil rights,[3][44] and soon said she would issue an executive order requiring additional training for all officers on how to implement SB 1070 without engaging in racial profiling;[45] the order was issued on April 23, 2010.[46] Ultimately, she said, "We have to trust our law enforcement."[3] Sponsor Pearce called the bill's signing "a good day for America."[21]

News of the law and the debate around immigration gained national attention, especially on cable news television channels, where topics that attract strong opinions are often given extra airtime.[47] The immigration issue also was center stage in the re-election campaign of Republican U.S. Senator from Arizona John McCain, who had been a past champion of federal immigration reform measures such as the Comprehensive Immigration Reform Act of 2007.[37] Also faced with a primary battle, against the more conservative J. D. Hayworth (who had made measures against illegal immigration a central point of his candidacy), McCain supported SB1070 only hours before its passage in the State Senate.[3][37] McCain said on The O'Reilly Factor: "It's the drivers of cars with illegals in it that are intentionally causing accidents on the freeway. Look, our border is not secured. Our citizens are not safe."[37] McCain subsequently became a vocal defender of the law, saying that the state had been forced to take action given the federal government's inability to control the border.[48][49]

Reaction

Opinion polls

A Rasmussen Reports poll done nationally around the time of the signing indicated that 60 percent of Americans were in favor, and 31 percent opposed, to legislation that allows local police to "stop and verify the immigration status of anyone they suspect of being an illegal immigrant."[10] The same poll also indicated that 58 percent are at least somewhat concerned that "efforts to identify and deport illegal immigrants will also end up violating the civil rights of some U.S. citizens."[10] A national Gallup Poll found that more than three-quarters of Americans had heard about the law, and of those who had, 51 percent were in favor of it against 39 percent opposed.[11] An Angus Reid Public Opinion poll indicated that 71 percent of Americans said they supported the notion of requiring their own police to determine people's status if there was "reasonable suspicion" the people were illegal immigrants, and arresting those people if they could not prove they were legally in the United States.[12] A nationwide New York Times/CBS News poll found similar results to the others, with 51 percent of respondents saying the Arizona law was "about right" in its approach to the problem of illegal immigration, 36 percent saying it went too far, and 9 percent saying it did not go far enough.[50] Another CBS News poll, conducted a month after the signing, showed 52 percent seeing the law as about right, 28 percent thinking it goes too far, and 17 percent thinking it does not go far enough.[51] A 57 percent majority thought that the federal government should be responsible for determining immigration law.[50] A national Fox News poll found that 61 percent of respondents thought Arizona was right to take action itself rather than wait for federal action, and 64 percent thought the Obama administration should wait and see how the law works in practice rather than trying to stop it right away.[52] Experts caution that in general, polling has difficulty reflecting complex immigration issues and law.[11] Pollsters argue the numbers likely represent an overall frustration with Washington and support for Arizona's willingness to act, rather than an anti-immigrant reaction.[53]

Another Rasmussen poll, done statewide after several days of heavy news coverage about the controversial law and its signing, found a large majority of Arizonans still supported it, by a 64 percent to 30 percent margin.[9] Rasmussen also found that Brewer's approval ratings as governor have shot up, going from 40 percent of likely voters before the signing to 56 percent after, and that her margin over prospective Democratic gubernatorial opponent, State Attorney General Terry Goddard (who opposes the law) widened.[54] A poll done by Arizona State University researchers found that 81 percent of registered Latino voters in the state opposed SB 1070.[55]

Public officials

United States

In the United States, supporters and opposers of the bill have roughly followed party lines, with Democrats generally opposing the bill and many, but not all, Republicans supporting it.

The bill was criticized by President Barack Obama, who called it "misguided" and said it would "undermine basic notions of fairness that we cherish as Americans, as well as the trust between police and our communities that is so crucial to keeping us safe."[3][37] Obama did later note that the HB 2162 modification had stipulated that the law not be applied in a discriminatory fashion, but the president said there was still the possibility of suspected illegal immigrants "being harassed and arrested".[56] He repeatedly called for federal immigration reform legislation to forestall such actions among the states and as the only long-term solution to the problem of illegal immigration.[3][37][56][57] Governor Brewer and President Obama met at the White House in early June 2010 to discuss immigration and border security issues in the wake of SB 1070; the meeting was termed pleasant, but brought about little change in the participants' stances.[1]

Two senior and one mid-level federal public officials criticized the Act before reading it. Secretary of Homeland Security and former Arizona governor Janet Napolitano testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that she had "deep concerns" about the law and that it would divert necessary law enforcement resources from combating violent criminals.[58] (As governor, Napolitano had consistently vetoed similar legislation throughout her term.[3][27]) In testimony before the Senate Homeland Security Committee, McCain drew out that Napolitano had made her remarks before having actually read the law.[59] U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder said the federal government was considering several options, including a court challenge based on the law leading to possible civil rights violations.[35][60] Holder drew fire from proponents of the law after he acknowledged that he had not read the statute.[59][61][62] Michael Posner, the Assistant Secretary of State for Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, brought up the law in discussions with a Chinese delegation to illustrate human rights areas the U.S. needed to improve on.[63] This led McCain and fellow senator from Arizona Jon Kyl to strongly object to any possibly implied comparison of the law to human rights abuses in China.[63] After defending Posner's statement to the Chinese, Assistant Secretary of State for Public Affairs P.J. Crowley admitted he had not read the Act.[64] The admissions by Napolitano and Holder that they had not yet read the law became an enduring criticism of the reaction against the law.[64][65] Former Alaska governor and vice-presidential candidate Sarah Palin accused the party in power of being willing to "criticize bills (and divide the country with ensuing rhetoric) without actually reading them."[64] Governor Brewer's election campaign issued a video featuring a frog hand puppet that sang "reading helps you know what you're talkin' 'bout" and urged viewers to fully read the law.[65] In reaction to the question, President Obama told a group of Republican senators that he had in fact read the law.[66]

Senior Democratic U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer of New York and Mayor of New York City Michael Bloomberg have criticized the law, with Bloomberg stating that it sends exactly the wrong message to international companies and travelers.[44]

Democrat Linda Sánchez, U.S. Representative from California's 39th congressional district, has claimed that white supremacy groups are in part to blame for the law's passage, saying, "There's a concerted effort behind promoting these kinds of laws on a state-by-state basis by people who have ties to white supremacy groups. It's been documented. It's not mainstream politics."[67] Republican Representative Gary Miller, from California's 42nd congressional district, called her remarks "an outrageous accusation [and a] red herring. [She's] trying to change the debate from what the law says."[67] Sánchez' district is in Los Angeles County and Miller's district is in both Los Angeles County and neighboring Orange County.

The law has been popular among the Republican Party base electorate; however, several Republicans have opposed aspects of the measure, mostly from those who have represented heavily Hispanic states.[53] These include former Governor of Florida Jeb Bush,[68] former Speaker of the Florida House of Representatives and current U.S. senatorial candidate Marco Rubio,[68] and former George W. Bush chief political strategist Karl Rove.[69] Some analysts have stated that Republican support for the law gives short-term political benefits by energizing their base and independents, but longer term carries the potential of alienating the growing Hispanic population from the party.[53][70] The issue played a role in several Republican primary contests during the 2010 congressional election season.[71]

One Arizona Democrat who defended the bill was Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords, who said her constituents were "sick and tired" of the federal government failing to protect the border and that the current situation was "completely unacceptable."[45]

Mexico

Mexican President Felipe Calderón's office said that "the Mexican government condemns the approval of the law [and] the criminalization of migration."[6] President Calderón also characterized the new law as a "violation of human rights".[72] Calderón repeated his criticism during a subsequent state visit to the White House.[56]

The measure was also strongly criticized by Mexican health minister José Ángel Córdova, former education minister Josefina Vázquez Mota, and Governor of Baja California José Guadalupe Osuna Millán, with Osuna saying it "could disrupt the indispensable economic, political and cultural exchanges of the entire border region."[72] The Mexican Foreign Ministry issued a travel advisory for its citizens visiting Arizona, saying "It must be assumed that every Mexican citizen may be harassed and questioned without further cause at any time."[73][74]

In response to these comments, some in the U.S. noted that Mexico has its own law, similar to SB 1070, that gives the power to local police forces to check documents of people suspected of being in the country illegally.[75] Immigration and human rights activists have also said Mexican authorities frequently engage in racial profiling, harassment, and shakedowns against migrants from Central America.[75]

Arizona law enforcement

Arizona's law enforcement groups have been split on the bill,[29][76] with statewide rank-and-file police officer groups generally supporting it and police chief associations opposing it.[21][77]

The Arizona Association of Chiefs of Police criticized the legislation, calling the provisions of the bill "problematic" and expressing that it will negatively affect the ability of law enforcement agencies across the state to fulfill their many responsibilities in a timely manner.[78] Additionally, some officers have repeated the past concern that illegal immigrants may come to fear the police, and not contact them in situations of emergency or in instances where they have valuable knowledge of a crime.[77][79] However, the Phoenix Law Enforcement Association, which represents the city's police officers, has supported the legislation and lobbied aggressively for its passage.[76][77] Officers supporting the measure say they have many indicators other than race they can use to determine whether someone may be an illegal immigrant, such as absent identification or conflicting statements made.[77]

The measure was hailed by Joe Arpaio, Sheriff of Maricopa County, Arizona – known for his tough crackdowns on illegal immigration within his own jurisdiction – who hoped the measure would cause the federal action to seal the border.[6] Arpaio said, "I think they'll be afraid that other states will follow this new law that's now been passed."[6]

Religious organizations and perspectives

Activists within the church were present on both sides of the immigration debate,[80] and both proponents and opponents of the law appealed to religious arguments for support.[81]

State Senator Pearce, a devout member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (which has a substantial population in Arizona), frequently said that his efforts to push forward this legislation was based on that church's 13 Articles of Faith, one of which instructs in obeying the law.[80][82] This association caused a backlash against the LDS Church and threatened its proselytizing efforts among the area's Hispanic population.[82] The church emphasized that it took no position on the law or immigration in general and that Pearce did not speak for it.[80][82]

The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops denounced the law, characterizing it as draconian and saying it "could lead to the wrongful questioning and arrest of U.S. citizens."[83] The National Council of Churches also criticized the law, saying that it ran counter to centuries of biblical teachings regarding justice and neighborliness.[84]

Other members of the Christian clergy differed on the law.[85] United Methodist Church Bishop Minerva G. Carcaño of Arizona's Desert Southwest Conference opposed it as "unwise, short sighted and mean spirited"[86] and led a mission of prominent religious figures to Washington to lobby for comprehensive immigration reform.[87][88] But others stressed the Biblical command to follow laws.[85] While there was a perception that most Christian groups opposed the law, Mark Tooley of the Institute on Religion and Democracy said that immigration was a political issue that "Christians across the spectrum can disagree about" and that liberal churches were simply more outspoken on this matter.[85]

Concerns over potential civil rights violations

In its final form, HB 2162 specifically prohibits a law enforcement officer from using race as a basis for having reasonable suspicion to check a person's status, except as authorized by the U.S. or Arizona constitution. It states, "A law enforcement official or agency of this state or a county, city, town or other political subdivision of this state may not consider race, color or national origin in implementing the requirements of this subsection except to the extent permitted by the United States or Arizona Constitution."[17] While the U.S. and Arizona constitutions ordinarily prohibit use of race as a basis for a stop or arrest, the U.S. and Arizona supreme courts have held that race may be considered in enforcing immigration law. In United States v. Brignoni-Ponce, the Supreme Court found: “The likelihood that any given person of Mexican ancestry is an alien is high enough to make Mexican appearance a relevant factor.”[89] The Arizona Supreme Court agrees that “enforcement of immigration laws often involves a relevant consideration of ethnic factors.”[90] Both decisions say that race alone, however, is an insufficient basis to stop or arrest. Accordingly, the Arizona law seems to allow the use of race, but only as one factor.

Critics of the measure have accused it of encouraging racial profiling, and as such it has been called the "Driving While Brown", "Living While Brown", or "Walking While Brown" law.[91][92][93] The Reverend Jesse Jackson said that opposition to the law would lead to common ground being formed between Latinos and African Americans[92] (the latter's vernacular phrase "Driving While Black" was the origin of the new phrases against the Arizona law).

The National Association of Latino Elected and Appointed Officials said the legislation was "an unconstitutional and costly measure that will violate the civil rights of all Arizonans."[94] Mayor Chris Coleman of Saint Paul, Minnesota, labeled it as "draconian" as did Democratic Texas House of Representatives member Garnet Coleman.[95][96]

Some Latino leaders have compared the law to Apartheid in South Africa or the Japanese American internment during World War II.[21][97]

Los Angeles Councilwoman Janice Hahn and Congressman Jared Polis of Colorado also said the law's requirement to carry papers all the time was reminiscent of the anti-Jewish legislation in prewar Nazi Germany and feared that Arizona was headed towards becoming a police state.[58][98] Cardinal Roger Mahony of Los Angeles said, "I can't imagine Arizonans now reverting to German Nazi and Russian Communist techniques whereby people are required to turn one another in to the authorities on any suspicion of documentation."[99]

The Anti-Defamation League called for an end to the comparisons with Nazi Germany, saying that no matter how odious or unconstitutional the Arizona law might be, it did not compare to the role that Nazi identity cards played in what eventually became the extermination of European Jews.[100]

Proponents of the law have rejected such criticism, and argued that the law was reasonable, limited, and carefully crafted.[101] Stewart Baker, a former Homeland Security official in the George W. Bush administration, said, "The coverage of this law and the text of the law are a little hard to square. There's nothing in the law that requires cities to stop people without cause, or encourages racial or ethnic profiling by itself."[35]

Republican member of the Arizona House of Representatives Steve Montenegro supported the law, saying that "This bill has nothing to do with race or profiling."[102] Montenegro, who legally immigrated to the U.S. from El Salvador with his family when he was four, stated, "I am saying if you here illegally, get in line, come in the right way."[102]

Protests

Thousands of people staged protests in state capital Phoenix over the law around the time of its signing, and a pro-immigrant activist called the measure "racist".[36][103] Passage of the HB 2162 modifications to the law, although intended to address some of the criticisms of it, did little to change the minds of the law's opponents.[50][104]

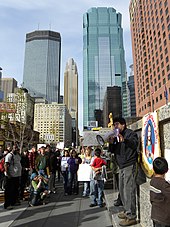

Tens of thousands of people demonstrated against the law in over 70 U.S. cities on May 1, 2010, a day traditionally used around the world to assert workers' rights.[7][105][106] A rally in Los Angeles, attended by Cardinal Mahoney, attracted between 50,000 and 60,000 people, with protesters waving Mexican flags and chanting "Sí se puede".[7][105][107] The city had become the national epicenter of protests against the Arizona law.[107] Around 25,000 people were at a protest in Dallas and more than 5,000 were in Chicago and Milwaukee, while rallies in other cities generally attracted around a thousand people or so.[105][106] Democratic U.S. Congressman from Illinois Luis Gutiérrez was part of a 35-person group arrested in front of the White House in a planned act of civil disobedience that was also urging President Obama to push for comprehensive immigration reform.[108] There and in some other locations, demonstrators expressed frustration with what they saw as the administration's lack of action on immigration reform, with signs holding messages such as "Hey Obama! Don't deport my mama."[106]

Protests both for and against the act took place over Memorial Day Weekend in Phoenix and commanded thousands of people.[109] Those opposing it, mostly consisting of Latinos, marched five miles to the State Capitol in high heat, while those supporting it met in a stadium in an event arranged by elements of the Tea Party movement.[109]

Protests against the law extended to the arts and sports world as well. Colombian pop singer Shakira came to Phoenix and gave a joint press conference against the bill with Mayor of Phoenix Phil Gordon.[110] Linda Ronstadt, of part Mexican descent and raised in Arizona, also appeared in Phoenix and said, "Mexican-Americans are not going to take this lying down."[111] A May 16 concert in Mexico City's Zócalo, called Prepa Si Youth For Dignity: We Are All Arizona, drew some 85,000 people to hear Molotov, Jaguares, and Maldita Vecindad headline a seven-hour show in protest against the law.[112]

The Major League Baseball Players Association, of whose members one quarter are born outside the U.S., said that the law "could have a negative impact on hundreds of major league players," especially since many teams come to Arizona for spring training, and called for it to be "repealed or modified promptly."[113] A Major League Baseball game at Wrigley Field where the Arizona Diamondbacks were visiting the Chicago Cubs saw demonstrators protesting the law.[114] Protesters focused on the Diamondbacks because owner Ken Kendrick had been a prominent fundraiser in Republican causes, but he in fact opposed the law.[115] The Phoenix Suns of the National Basketball Association wore their "Los Suns" uniforms normally used for the league's "Noche Latina" program for their May 5, 2010 (Cinco de Mayo) playoff game against the San Antonio Spurs to show their support for Arizona's Latino community and to voice disapproval of the immigration law.[116] The Suns' political action, rare in American team sports, created a firestorm and drew opposition from many of the teams' fans;[117] President Obama highlighted it, while conservative radio commentator Rush Limbaugh called the move "cowardice, pure and simple."[118]

Boycotts

Boycotts of Arizona were quickly organized in response to SB 1070, with resolutions by city governments being among the first to materialize.[58][119][120][121] The government of San Francisco, the Los Angeles City Council, and city officials in Oakland, Minneapolis, Saint Paul, Denver, and Seattle all took specific action, usually by banning some of their employees from work-related travel to Arizona or by limiting city business done with companies headquartered in Arizona.[4][95][121][122]

In an attempt to push back against the Los Angeles City Council's action, which was valued at $56 million,[4] Arizona Corporation Commissioner Gary Pierce sent a letter to Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa, suggesting that he'd "be happy to encourage Arizona utilities to renegotiate your power agreements so that Los Angeles no longer receives any power from Arizona-based generation."[123] Such a move was infeasible for reasons of ownership and governance, and Pierce later stated that he was not making a literal threat to cut power to the city.[123]

U.S. Congressman Raúl Grijalva, from Arizona's 7th congressional district, had been the first prominent officeholder to call for an economic boycott of his state, by industries from manufacturing to tourism, in response to SB 1070.[124] His call was echoed by La Opinión, the nation's largest Spanish-language newspaper.[119] But calls for various kinds of boycotts were also spread through social media sites, and there were reports of individuals or groups changing their plans or activities in protest of the law.[103][119][125][126] The prospect of an adverse economic impact made Arizonan business leaders and groups nervous,[58][103][125] and Phoenix officials estimated that the city could lose up to $90 million in hotel and convention business over the next five years due to the controversy over the law.[127] Phoenix Mayor Gordon urged people not to punish the entire state as a consequence.[119]

Major organizations opposing the law, such as the National Council of La Raza, refrained from initially supporting a boycott, knowing that such actions are difficult to execute successfully and even if done cause broad economic suffering, including among the people they are supporting.[8] Arizona did have a past case of a large-scale boycott during the late 1980s and early 1990s, when it lost many conventions and several hundred million dollars in revenues after Governor Evan Mecham's cancellation of a Martin Luther King, Jr. Day state holiday and a subsequent failed initial referendum to restore it.[8] La Raza subsequently switched its position regarding SB 1070 and became one of the leaders of the boycott effort.[128]

The Arizona Hispanic Chamber of Commerce opposed both the law and the idea of boycotting, saying the latter would only hurt small businesses and the state’s economy, which was already badly damaged by the collapse of real estate prices and the late-2000s recession.[129] Other state business groups opposed a boycott for the same reasons.[130] Religious groups opposed to the law split on whether a boycott was advisable, with Bishop Carcaño saying one "would only extend our recession by three to five years and hit those who are poorest among us."[88] Representative Grijalva said he wanted to keep a boycott restricted to conferences and conventions and only for a limited time: "The idea is to send a message, not grind down the state economy."[8] By early May, the state had lost a projected $6–10 million in business revenue, according to the Arizona Hotel & Lodging Association.[130] Governor Brewer said that she was disappointed and surprised at the proposed boycotts – "How could further punishing families and businesses, large and small, be a solution viewed as constructive?" – but that the state would not back away from the law.[131] President Obama took no position on the matter, saying, "I'm the president of the United States, I don't endorse boycotts or not endorse boycotts. That's something that private citizens can make a decision about."[57]

Sports-related boycotts were proposed as well. U.S. Congressman from New York José Serrano asked baseball commissioner Bud Selig to move the 2011 Major League Baseball All-Star Game from Chase Field in Phoenix.[114] The manager of the Chicago White Sox, Ozzie Guillen, stated that he would boycott that game, "as a Latin American".[132] The World Boxing Council, based in Mexico City, said it would not schedule Mexican boxers to fight in the state.[114]

A boycott by musicians saying they would not stage performances in Arizona was started by Zack de la Rocha, the lead singer of Rage Against the Machine and the son of a Mexican American, who said, "Some of us grew up dealing with racial profiling, but this law (SB 1070) takes it to a whole new low."[133][134] Called the Sound Strike, artists signing on with the effort included Kanye West, Cypress Hill, Massive Attack, Conor Oberst, Sonic Youth, Joe Satriani, Rise Against, Tenacious D, and Los Tigres del Norte.[133][134] Some other Spanish-language artists did not join this effort, but avoided playing in Arizona on their tours anyway; these included Pitbull, Wisin & Yandel, Jenni Rivera, Espinoza Paz, and Conjunto Primavera.[133] The Sound Strike boycott has failed to gain support from many area- or stadium-level acts, and no country music acts have signed on.[135]

In reaction to the boycott talk, proponents of the law advocated making a special effort to buy products and services from Arizona in order to indicate support for the law.[136][137] These efforts, sometimes termed a "buycott", were spread by social media and talk radio as well as by elements of the Tea Party movement.[136][137]

Impact

Many illegal migrant workers left Arizona to seek employment in Texas, California and New Mexico in order to avoid confrontations with Arizona law enforcement.[138] Some Christian churches in Arizona with large immigrant congregations reported a 30 percent drop in their attendance figures.[88] Businesses that cater to the Hispanic population in parts of Arizona have reported a downturn in business following passage of the law.[139] The drop in business is attributed to large numbers of Hispanics leaving Arizona for other states, primarily California and Texas.[140]

The weeks after the bill's signing saw a sharp increase in the number of Hispanics registering their party affiliations as Democrats.[55]

The Arizona legislation was one of several reasons pushing Democratic congressional leaders to introduce a proposal addressing immigration.[141] Senator Schumer sent a letter to Governor Brewer asking her to delay the law while Congress works on comprehensive immigration reform, but Brewer quickly rejected the proposal.[142]

Republican politicians in nearly a dozen states including Utah, Georgia, Colorado, Maryland, Ohio, North Carolina, Texas, Missouri, Oklahoma, and Nebraska have endorsed their own state legislation on illegal immigration in the wake of Arizona SB 1070; many of these politicians hope to pass legislation that mirrors Arizona's.[13][143] In some cases, such as with Oklahoma House of Representatives member Randy Terrill's position, other states would go further in regard to penalties.[121] Such proposals drew strong reaction both for and against,[144] and some states may wait to see how the Arizona law fares in the courts before moving forward.[13] However, the other states along the Mexican border – Texas, New Mexico, and California – generally showed little interest in following Arizona's path.[24] This was due to their having established, powerful Hispanic communities, deep cultural ties to Mexico, past experience with bruising political battles over the issue (such as with California Proposition 187 in the 1990s), and the perception among their populations that illegal immigration was less severe a problem.[24]

Some immigration experts said the law might make workers with H-1B visas vulnerable to being caught in public without their hard-to-replace paperwork, which they are ordinarily reluctant to carry with them on a daily basis, and that as a consequence universities and technology companies in the state might find it harder to recruit students and employees.[145] Some college and university administrators shared this fear, and President Robert N. Shelton of the University of Arizona expressed concern regarding the withdrawal of a number of honor roll students from the university in reaction to this bill.[146]

Challenges to legality and constitutionality

A number of national and state organizations have announced their intentions to take or support legal action against the statute on constitutional grounds, including the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the NALEO Educational Fund, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), and Mayor of Phoenix Gordon.[23][94][29][21][147] In addition, President Obama instructed his administration to closely monitor the civil rights implications of the law.[23]

The Supremacy Clause vs. concurrent enforcement

The ACLU criticized the statute as a violation of the Supremacy Clause of the United States Constitution, which gives the federal government authority over the states in immigration matters and provides that only the federal government can enact and enforce immigration laws.[23][147] Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional scholar and dean of the University of California, Irvine School of Law says that "The law is clearly pre-empted by federal law under Supreme Court precedents."[35]

According to one of the bill's authors (Kobach), the law embodies the doctrine of "concurrent enforcement" – i.e., that the state law parallels applicable federal law without any conflict[35] – and that believes it would thus survive any challenge: "There are some things that states can do and some that states can't do, but this law threads the needle perfectly.... Arizona only penalizes what is already a crime under federal law."[34] State Senator Pearce noted that some past state laws on immigration enforcement had been upheld in federal courts.[23] In Gonzales v. City of Peoria (9th Cir. 1983),[148] the Court held that the Immigration and Naturalization Act precludes local enforcement of the Act's civil provisions but does not preclude local enforcement of the Act's criminal provisions. The U.S. Attorney General may enter into a written agreement with a state or local government agency, under which that agency's employees perform the function of an immigration officer in relation to the investigation, apprehension, or detention of aliens in the United States;[149] however, such an agreement is not required for the agency's employees to perform those functions.[150]

However, various legal experts were divided on whether the law would survive a court challenge, with one law professor saying it "sits right on that thin line of pure state criminal law and federally controlled immigration law."[35] Past lower court decisions in this area were not always consistent and a decision on the bill's legality from the U.S. Supreme Court is one possible outcome.[35]

Court actions filed against the Act

On April 29, 2010, the National Coalition of Latino Clergy and Christian Leaders and a Tucson police officer, Martin Escobar, were the first to file suit against SB 1070, with each doing so separately in federal court.[151][152] The National Coalition's filing claimed that the law usurped federal responsibilities under the Supremacy Clause, and also that it lends itself to racial profiling by imposing a "reasonable suspicion" requirement upon police officers to check the immigration status of those they come in official conduct with, which will in turn be subject to too much personal interpretation by each officer.[152][153] Escobar's suit argued that there was no race-neutral criteria available to him to suspect that a person was an illegal immigrant, and that implementation of the law would hinder police investigations in areas that were predominantly Hispanic.[77][154] The suit also claimed the Act violated federal law because the police and the city have no authority to perform immigration-related duties.[154] The Tucson police department made clear that Escobar was not acting on its behalf, and they received many calls from citizens complaining about his suit.[154]

A Phoenix police officer, David Salgado, quickly followed with his own federal suit, claiming that to enforce the law he would be required to violate the rights of Hispanics.[155] He also said that he would be forced to spend his own time and resources studying the law's requirements, and that he was liable to being sued whether he enforced the law or not.[155][156] Another individual suit was filed by Roberto Javier Frisancho, a naturalized citizen and Washington, D.C., resident who said he planned to visit the state to conduct research.[157]

On May 5, Tucson and Flagstaff became the first two cities to authorize legal action against the state over the Act;[104] San Luis later joined them.[158] However, as of mid-late May, none of them had actually filed a suit.[157] In late May, though, the city of Tucson filed a cross-claim and joined Officer Escobar in his suit.[159]

On May 17, a joint class action lawsuit was filed in U.S. District Court on behalf of ten individuals and fourteen labor, religious, and civil rights organizations.[137][157][158][160] The legal counsel filing the action, which is the largest of those filed, is a collaboration of the ACLU, the Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, the National Immigration Law Center, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the National Day Laborer Organizing Network, and the Asian Pacific American Legal Center.[157] The suit seeks to prevent SB 1070 from going into effect by charging that it: violates the federal Supremacy Clause by attempting to bypass federal immigration law; violates the Fourteenth Amendment and Equal Protection Clause rights of racial and national origin minorities by subjecting them to stops, detentions, and arrests based on their race or origin; violates the First Amendment rights of freedom of speech by exposing speakers to scrutiny based on their language or accent; violates the Fourth Amendment's prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures because it allows for warrantless searches in absence of probable cause; violates the Fourteenth Amendment's Due Process Clause by being impermissibly vague; and infringes on constitutional provisions that protect the right to travel without being stopped, questioned, or detained.[157] This suit named County's Attorney and Sheriffs as defendants, rather than the State of Arizona or Governor Brewer as the earlier suits had.[157][158] On June 4, the ACLU and others filed a request for an injunction, arguing that the act's scheduled start date of July 29 should be postponed until the underlying legal challenges against it are resolved.[161]

It is possible that all the suits would be combined into one case for the courts to hear.[157][158] Kobach remained optimistic that the suits would fail, saying "I think it will be difficult for the plaintiffs challenging this. They are heavy on political rhetoric but light on legal arguments."[33] In late May 2010, Governor Brewer issued an executive order to create a legal defense fund to handle suits over the law.[162] Brewer got into a dispute with Arizona Attorney General Terry Goddard over whether he would defend the law against legal challenges, as a state attorney general normally would.[109] Brewer accused Goddard, who opposed the law personally and was one of Brewer's possible rivals in the gubernatorial election, of colluding with the U.S. Justice Department as it deliberated whether to challenge the law in court.[109]

See also

References

- ^ a b Rough, Ginger (June 4, 2010). "Brewer calls Obama meeting a 'success'". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b Arizona SB 1070, §1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Archibold, Randal C. (April 24, 2010). "U.S.'s Toughest Immigration Law Is Signed in Arizona". The New York Times. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Los Angeles approves Arizona business boycott". CNN. May 13, 2010.

- ^ a b Vaughan, Jessica M. (April 2006). "Attrition Through Enforcement: A Cost-Effective Strategy to Shrink the Illegal Population". Center for Immigration Studies.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cooper, Jonathan J. (April 24, 2010). "Arizona law raises fear of racial profiling". Associated Press.

- ^ a b c "Arizona immigration law sparks huge rallies". CBC News. May 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Thompson, Krissah (April 30, 2010). "Protesters of Arizona's new immigration law try to focus boycotts". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b "Arizona Voters Favor Welcoming Immigration Policy, 64% Support New Immigration Law". Rasmussen Reports. April 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Nationally, 60% Favor Letting Local Police Stop and Verify Immigration Status". Rasmussen Reports. April 26, 2010.

- ^ a b c Wood, Daniel B. (April 30, 2010). "Opinion polls show broad support for tough Arizona immigration law". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ a b "Poll: Most support Arizona immigration law". United Press International. April 29, 2010.

- ^ a b c Patten, David A. (May 5, 2010). "Arizona-Style Rebellions Over Immigration Spread". NewsMax.com.

- ^ "General Effective Dates". Arizona State Legislature. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ Arizona State Legislature. "Ariz. Rev. Stat. § 1-103". Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- ^ a b Arizona SB 1070, §3.

- ^ a b c Arizona HB 2162, §3.

- ^ a b c d Arizona SB 1070, §2.

- ^ Arizona HB 2162, §4.

- ^ a b c Arizona SB 1070, §5.

- ^ a b c d e f Harris, Craig; Rau, Alia Beard; Creno, Glen (April 24, 2010). "Arizona governor signs immigration law; foes promise fight". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ Silverleib, Alan (April 30, 2010). "Arizona governor signs changes into immigration law". CNN.

- ^ a b c d e Nowicki, Dan (April 25, 2010). "Court fight looms on new immigration law". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b c d e "Other border states shun Arizona's immigration law". Asbury Park Press. Associated Press. May 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f Archibold, Randal C. (June 20, 2010). "In Border Violence, Perception Is Greater Than Crime Statistics". The New York Times. p. 18.

- ^ Broder, David S. (July 8, 2007). "Arizona's Border Burden". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b Rodriguez, Tito (April 27, 2010). "Governor Jan Brewer Signs (S.B. 1070) Toughest Illegal Immigration Law in U.S." Mexican-American.org.

- ^ a b c d Thornburgh, Nathan; Douglas (June 14, 2010). "The Battle for Arizona". Time. pp. 38–43.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Ariz. Lawmakers Pass Controversial Illegal Immigration Bill". KPHO-TV. April 20, 2010.

- ^ a b Archibold, Randal C.; Steinhauer, Jennifer (April 29, 2010). "Welcome to Arizona, Outpost of Contradictions". The New York Times. p. A14.

- ^ a b c Rossi, Donna (April 14, 2010). "Immigration Bill Takes Huge Step Forward". KPHO-TV.

- ^ Robbins, Ted (March 12, 2008). "The Man Behind Arizona's Toughest Immigrant Laws". Morning Edition. NPR.

- ^ a b c d Rau, Alia Beard (May 31, 2010). "Arizona immigration law was crafted by activist". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b O'Leary, Kevin (April 16, 2010). "Arizona's Tough New Law Against Illegal Immigrants". Time.

- ^ a b c d e f g Schwartz, John; Archibold, Randal C. (April 28, 2010). "A Law Facing a Tough Road Through the Courts". The New York Times. p. A17.

- ^ a b c "Thousands Protest Ariz. Immigration Law". CBS News. Associated Press. April 23, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Sheldon, Albert S. (April 24, 2010). "Obama criticizes controversial immigration law". The Vancouver Sun. CanWest News Service.

- ^ "Bill Status Votes For SB1070 – Final Reading". Arizona State Legislature. Retrieved April 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rau, Alia Beard Rau; Pitzl, Mary Jo; Rough, Ginger (April 21, 2010). "Angst rises as Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer mulls immigration bill". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ "Governor Signing Deadlines". StateScape. Retrieved May 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Archibold, Randal C. (April 24, 2010). "Woman in the News: Unexpected Governor Takes an Unwavering Course". The New York Times.

- ^ Rough, Ginger (April 19, 2010). "Brewer has 'concerns' about immigration bill; won't say if she'll sign or veto". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b "70% of Arizona Voters Favor New State Measure Cracking Down On Illegal Immigration". Rasmussen Reports. April 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c Samuels, Tanyanika (April 24, 2010). "New York politicians rip into Arizona immigration law, call it 'un-American'". New York Daily News.

- ^ a b "Democrats call for elimination of Arizona's new immigration law". CNN. April 28, 2010.

- ^ "Governor Jan Brewer Statement on Signing SB 1070" (PDF). Retrieved May 5, 2010.

- ^ Morgan, Jon. "PEJ News Coverage Index: April 19–25, 2010". Pew Research Center. Retrieved June 13, 2010.

- ^ Good, Chris (April 26, 2010). "McCain Defends Arizona's Immigration Law". The Atlantic.

- ^ Slevin, Peter (May 22, 2010). "Hard line on immigration marks GOP race in Arizona". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c Archibold, Randal C.; Thee-Brenan, Megan (May 3, 2010). "Poll Shows Most in U.S. Want Overhaul of Immigration Laws". The New York Times. p. A15.

- ^ Condon, Stephanie (May 25, 2010). "Poll: Most Still Support Arizona Immigration Law". CBS News.

- ^ Blanton, Dana (May 7, 2010). "Fox News Poll: Arizona Was Right to Take Action on Immigration". Fox News.

- ^ a b c Hunt, Kasie (April 30, 2010). "Worries in Republican Arizona law could hurt party". Politico.

- ^ "Election 2010: Arizona Governor: Poll Bounce for Arizona Governor After Signing Immigration Law". Rasmussen Reports. April 28, 2010.

- ^ a b González, Daniel (June 8, 2010). "SB 1070 backlash spurs Hispanics to join Democrats". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b c LaFranchi, Howard (May 19, 2010). "Obama and Calderón agree: Arizona immigration law is wrong". The Christian Science Monitor.

- ^ a b Montopoli, Brian (May 27, 2010). "Obama: I Don't Endorse – or Not Endorse – Arizona Boycott". CBS News.

- ^ a b c d Gorman, Anna; Riccardi, Nicholas (April 28, 2010). "Calls to boycott Arizona grow over new immigration law". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b "Napolitano Admits She Hasn't Read Arizona Immigration Law in 'Detail'". Fox News. May 18, 2010.

- ^ "Holder: Feds may sue over Arizona immigration law". CNN. May 9, 2010.

- ^ Dinan, Stephen (May 13, 2010). "Holder hasn't read Arizona law he criticized". The Washington Times.

- ^ Markon, Jerry (May 14, 2010). "Holder is criticized for comments on Ariz. immigration law, which he hasn't read". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b "McCain, Kyl Call on Diplomat to Apologize for Arizona Law Comment to Chinese". Fox News. May 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c Condon, Stephanie (May 18, 2010). "Sarah Palin: Read Arizona Immigration Law before Condemning It". CBS News.

- ^ a b Alfano, Sean (May 27, 2010). "Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer employs singing frog hand puppet to promote immigration law". New York Daily News.

- ^ "Obama Tells GOP Senators He Has Read Arizona Immigration Law". Fox News. May 25, 2010.

- ^ a b "Congresswoman: White Supremacist Groups Behind Arizona Immigration Law". Fox News. June 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Martin, Jonathan (April 27, 2010). "Jeb Bush speaks out against Ariz. law". Politico.

- ^ Condon, Stephanie (April 28, 2010). "Karl Rove Speaks Out Against Arizona Immigration Law". CBS News.

- ^ Montopoli, Brian (April 27, 2010). "Arizona Immigration Bill Exposes GOP Rift". CBS News.

- ^ Steinhauer, Jennifer (May 22, 2010). "Immigration Law in Arizona Reveals G.O.P. Divisions". The New York Times. p. A1.

- ^ a b Booth, William (April 27, 2010). "Mexican officials condemn Arizona's tough new immigration law". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Travel alert". Mexico: Secretariat of External Relations. April 27, 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Kevin (April 27, 2010). "Mexico issues travel alert over new Ariz. immigration law". USA Today.

- ^ a b Hawley, Chris (May 25, 2010). "Activists blast Mexico's immigration law". USA Today.

- ^ a b Johnson, Elias (April 15, 2010). "Police Agencies Split Over Immigration Bill". KPHO-TV.

- ^ a b c d e "Ariz. immigration law divides police across US". Asbury Park Press. Associated Press. May 17, 2010.

- ^ "AACOP Statement on Senate Bill 1070" (PDF) (Press release). Arizona Association of Chiefs of Police. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ^ Slevin, Peter (April 30, 2010). "Arizona Law on Immigration Puts Police in Tight Spot". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c Stack, Peggy Fletcher (April 30, 2010). "Mormons on both sides in immigration controversy". The Salt Lake Tribune.

- ^ Adams, Andrew (April 30, 2010). "Religion becomes a topic of discussion in immigration debate". KSL-TV.

- ^ a b c González, Daniel (May 18, 2010). "Arizona immigration law fallout harms LDS Church outreach". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ "US bishops oppose 'draconian' Arizona immigration law". Catholic News Agency/EWTN News. April 28, 2010.

- ^ "Religious leaders say new Arizona immigration law is unjust, dangerous and contrary to biblical teaching". National Council of Churches. April 26, 2010.

- ^ a b c Severson, Lucky (May 21, 2010). "Churches and Arizona Immigration Law". Religion & Ethics Newsweekly. PBS.

- ^ "Bishop Minerva G. Caraño statement at SB 1070 press conference" (Press release). Desert Southwest Conference of the United Methodist Church. April 30, 2010.

- ^ Cummings, Jeanne (May 11, 2010). "Immigration advocates woo McCain". Politico.

- ^ a b c Goldberg, Eleanor (May 28, 2010). "Faith leaders tread carefully on Arizona boycott". Kansas City Star. Religion News Service.

- ^ United States v. Brignoni-Ponce,, 422 U.S. 873, 886-87 (1975).

- ^ State v. Graciano,, 653 P.2d 683, 687 n.7 (Ariz. 1982).

- ^ Johnson, Brad (April 23, 2010). "How can state's immigration bill not be un-American". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b Rev. Jackson, Jesse (April 27, 2010). "Common Ground, African-Americans & Latinos". The Huffington Post.

- ^ Montoya, Butch (May 1, 2010). "Taking a stand against Arizona law". Denver Post.

- ^ a b Lakshman, Narayan (April 26, 2010). "Furore over Arizona immigration bill". The Hindu.

- ^ a b "Chris Coleman protests the AZ immigration law". KARE-TV. April 29, 2010.

- ^ Shieh, Pattie (April 28, 2010). "Arizona Immigration Law Controversy Spills into Texas". KRIV-TV.

- ^ Sisk, Richard; Einhorn, Erin (April 26, 2010). "Sharpton, other activists compare Arizona immigration law to apartheid, Nazi Germany and Jim Crow". New York Daily News.

- ^ Hunt, Kasie (April 26, 2010). "Democrat: Arizona law like 'Nazi Germany'". Politico.

- ^ "Cardinal Mahony compares Arizona immigration bill to Nazism, Communism". Catholic World News. April 20, 2010.

- ^ Harkov, Lahav (April 29, 2010). "ADL: Stop Arizona-Holocaust analogies". The Jerusalem Post.

- ^ York, Byron (April 26, 2010). "A carefully crafted immigration law in Arizona". The Washington Examiner.

- ^ a b "Hispanic Rep. Montenegro Supports Immigration Law". KSAZ-TV. April 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c Condon, Stephanie (April 26, 2010). "Arizona Immigration Law Fight Far From Over". CBS News.

- ^ a b Condon, Stephanie (May 5, 2010). "Tucson, Flagstaff Sue Arizona over Immigration Law". CBS News.

- ^ a b c Tareen, Sophia (May 1, 2010). "Anger over Ariz. immigration law drives US rallies". Associated Press.

- ^ a b c Preston, Julia (May 2, 2010). "Fueled by Anger Over Arizona Law, Immigration Advocates Rally for Change". The New York Times. p. A22.

- ^ a b Watanabe, Teresa; McDonnell, Patrick (May 1, 2010). "L.A.'s May Day immigration rally is nation's largest". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Smith, Ben (May 1, 2010). "Gutierrez arrested in protest". Politico.

- ^ a b c d Archibold, Randal C. (May 30, 2010). "The Two Sides Intersect in Immigration Debate". The New York Times. p. 14.

- ^ "Shakira visits Phoenix over tough immigration law". China Daily. April 30, 2010.

- ^ Heldman, Breanne L. (April 30, 2010). "Ricky Martin: Arizona Law 'Makes No Sense'". E! Online.

- ^ Ben-Yehuda, Ayala (May 17, 2010). "Mexican Rock Acts Headline Concert To Protest Arizona Law". Billboard.

- ^ Baxter, Kevin; DiGiovanna, Mike (May 1, 2010). "Baseball union calls for Arizona immigration law to be 'repealed or modified'". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ a b c "Congressman asks Selig to move game". ESPN. April 30, 2010.

- ^ Rowe, Ashlee (April 29, 2010). "D-backs play on field being shadowed by protests". KTAR 620 ESPN Radio.

- ^ Adande, J.A. (May 5, 2010). "Suns using jerseys to send message". ESPN.

- ^ Harris, Craig (May 6, 2010). "Political gesture by Phoenix Suns, a rarity in sports, angers many fans". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ Gloster, Rob (May 6, 2010). "Obama, Limbaugh Focus on 'Los Suns' Jerseys in NBA Playoffs". BusinessWeek. Bloomberg News.

- ^ a b c d Archibold, Randal C. (April 27, 2010). "In Wake of Immigration Law, Calls for an Economic Boycott of Arizona". The New York Times. p. A13.

- ^ Craig, Tim (April 28, 2010). "D.C. Council to consider boycotting Arizona to protest immigration law". The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c Sacks, Ethan (April 30, 2010). "Battle over Arizona's SB 1070: Oklahoma eyes similar immigration law; City Councils eye boycotts". New York Daily News.

- ^ Associated Press (May 17, 2010). "Seattle City Council approves Arizona boycott". The Seattle Times.

- ^ a b Randazzo, Ryan (May 19, 2010). "Arizona electricity regulator threatens power supply to Los Angeles". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ Blackstone, John (April 24, 2010). "Congressman Touts Boycott Of Immigration Law". CBS News.

- ^ a b Beard, Betty; Gilbertson, Dawn (April 27, 2010). "Calls to boycott Arizona multiply on social media". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ "Alpha Phi Alpha Removes Convention From Ariz. Due To Immigration Law". News One. Radio One. May 1, 2010.

- ^ Berry, Jahna (May 11, 2010). "$90 million at risk in boycott of Arizona". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ Thompson, Krissah (May 12, 2010). "Arizona tourism loses more business in wake of immigration law vote". The Washington Post.

- ^ Casacchia, Chris (April 30, 2010). "Political parties still see Phoenix as potential convention site". Phoenix Business Journal.

- ^ a b Good, Chris (May 7, 2010). "Arizona's Immigration Law Comes With a Price". The Atlantic.

- ^ Fischer, Howard (May 6, 2010). "Governor: Boycotts disappointing but won't change new law". Arizona Daily Star.

- ^ Zirin, Dave (May 1, 2010). "'This is Racist Stuff': Baseball Players/Union Speak Out Against Arizona Law". The Huffington Post.

- ^ a b c Rohter, Larry (May 27, 2010). "Performers to Stay Away From Arizona in Protest of Law". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Condon, Stephanie (May 28, 2010). "Musicians Boycott Arizona to Protest Immigration Law". CBS News.

- ^ Rohter, Larry (May 28, 2010). "Musicians Differ in Responses to Arizona's New Immigration Law". The New York Times.

- ^ a b "Some don't buy Arizona boycotts". Marketplace. American Public Media. May 18, 2010.

- ^ a b c Shahbazi, Rudabeh (May 15, 2010). "SB 1070: Boycott v. 'Buycott'". KNXV-TV.

- ^ Shanks, Jon (April 29, 2010). "Immigrants Leaving Arizona - New Law Sends Workers to Texas, California & New Mexico". The National Ledger.

- ^ "Economy and Pressure - Hispanics Leaving Arizona, SB 1070 Blamed". National Ledger. June 14, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Hispanics Leaving Arizona - Illegal Workers to Texas and California". National Ledger. June 14, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Bacon Jr., Perry (April 29, 2010). "Democrats unveil immigration-reform proposal". The Washington Post.

- ^ Condon, Stephanie (May 7, 2010). "Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer Rejects Schumer's Plea to Delay Immigration Law". CBS News.

- ^ Nill, Andrea (April 28, 2010). "Report: Following Passage Of Arizona Law, At Least Seven States Contemplate Anti-Immigrant Legislation". ThinkProgress.org.

- ^ "Immigration Plan Draws Fire, Praise". KOCO-TV. April 29, 2010.

- ^ Thibodeau, Patrick (April 27, 2010). "Arizona's new 'papers, please' law may hurt H-1B workers". Computerworld.

- ^ "Students Withdraw From Arizona Universities In Reaction To Law". The Huffington Post. April 27, 2010.

- ^ a b "ACLU of Arizona Section By Section Analysis of SB 1070 'Immigration; Law Enforcement; Safe Neighborhoods'" (PDF) (Press release). American Civil Liberties Union. April 16, 2010.

- ^ Gonzales v. City of Peoria, 722 F.2d 468 (9th Cir. 1983).

- ^ 8 U.S.C. § 1357(g)(1).

- ^ 8 U.S.C. § 1357(g)(10).

- ^ Mirchandani, Rajesh (April 30, 2010). "Tough Arizona immigration law faces legal challenges". BBC News.

- ^ a b Serrano, Richard A.; Nicholas, Peter (April 29, 2010). "Obama administration considers challenges to Arizona immigration law". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Fischer, Howard (April 29, 2010). "2 lawsuits challenge Arizona's immigration law". Arizona Daily Star. Capitol Media Services.

- ^ a b c Pedersen, Brian J. (April 29, 2010). "Tucson cop first to sue to block AZ immigration law". Arizona Daily Star.

- ^ a b Rau, Alia Beard; Rough, Ginger (April 30, 2010). "3 lawsuits challenge legality of new law". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ Madrid, Ofelia (May 15, 2010). "Phoenix, Tucson officers sue over Arizona's new immigration law". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rau, Alia Beard (May 18, 2010). "14 organizations, 10 individuals file suit over Arizona's immigration law". The Arizona Republic.

- ^ a b c d "ACLU, Civil Rights Groups File Suit Against Arizona Immigration Law". Fox News. Associated Press. May 17, 2010.

- ^ Nunez, Steve; Pryor, Bryan (June 2, 2010). "City of Tucson joins officer's lawsuit against SB 1070". KGUN-TV.

- ^ "ACLU And Civil Rights Groups File Legal Challenge To Arizona Racial Profiling Law" (Press release). American Civil Liberties Union. May 17, 2010.

- ^ Ross, Lee (June 5, 2010). "New Challenge to Arizona Immigration Law". Fox News.

- ^ "Arizona Governor Jan Brewer creates legal defense fund for suits over immigration law SB1070". New York Daily News. Associated Press. May 27, 2010.

- Arizona SB 1070: "State of Arizona: 2010 Arizona Session Laws, Chapter 113, Forty-ninth Legislature, Second Regular Session: Senate Bill 1070: House Engrossed Senate Bill: immigration; law enforcement; safe neighborhoods (NOW: safe neighborhoods; immigration; law enforcement)". Arizona State Legislature. Retrieved April 30, 2010.

- Arizona HB 2162: "State of Arizona: Forty-ninth Legislature, Second Regular Session 2010: Session Laws, Chapter 211, House Bill 2162: Conference Version". Arizona State Legislature. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

External links

- Documents for SB 1070 at the Arizona State Legislature

- Documents for HB 2162 at the Arizona State Legislature

- House Engrossed Senate Bill SB 1070, as enacted, Arizona Governor website.

- Conference engrossed Bill HB 2162 Amending SB 1070, as enacted, Arizona Governor website.

- Gabriel J. Chin, Carissa Byrne Hessick, Toni Massaro & Marc Miller, Arizona Senate Bill 1070: A Preliminary Report